Framing Childhood Resilience Through Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory: A Discussion Paper

Repository uri, repository doi.

Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory (1979) conceptualises children’s development as a process of bi-directional and reciprocal relationships between a developing individual and those in surrounding environments, including teachers, parents, mass media and neighbouring communities. Using Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory, this paper will argue that resilience can be taught during childhood, from the complex social interactions that children have with parents to the interactions they have in school. First, there will be a focus on how resilience emerges from children’s individual personality traits and emotional intelligence. Bi-directional and reciprocal relationships will be addressed by focusing on the effects of parental abandonment on children’s attachment styles, as well as parent-focused interventions. Following this, the role of teachers and school-based interventions (SBIs) will be explored as sources for bolstering resilience among children. Alternative perspectives on resilience pathways, including meaning-oriented approaches and those that recognise the impact of broader influences beyond the microsystem (e.g., culture and media), will also be addressed in this paper. Finally, implications of resilience research for play-based approaches and educational psychologists will be discussed.

Description

Journal title, conference name, journal issn, volume title, publisher doi, publisher url, collections.

Ecological Systems Theory

Ecological Systems Theory (EST), also known as human ecology, is an ecological/ system framework developed in 1979 by Urie Bronfenbrenner (Harkonen, 2007). Harkonen notes that this theory was influenced by Vygotsky’s socio-cultural theory and Lewin’s behaviorism theory. Bronfenbrenner’s research focused on the impact of social interaction on child development. Bronfenbrenner believed that a person’s development was influenced by everything in the surrounding environment and social interactions within it. EST emphasizes that children are shaped by their interaction with others and the context. The theory has four complex layers called systems, commonly used in research. At first, ecological theory was most used in psychological research; however, several studies have used it in other fields such as law, business, management, teaching and learning, and education.

Previous Studies

EST has been used in many different fields, however, commonly, it is used in health and psychology, especially in child development (e.g., Heather, 2016; Esolage, 2014; Matinello, 2020). For instance, Walker et al. (2019) used an EST framework to examine risk factors for overweight and obese children with disabilities. The study focused on how layers of an ecological system or environment can negatively affect children with special needs in terms of weight and obesity. They found that microsystem such as school, family home, and extracurricular activities can impact overall health through physical activities and food selectivity. Furthermore, the second layer, mesosystem (e.g., family dynamic and parental employment), also can lead to an increase in children’s weight because of a lack of money to buy nutritious food. In addition, children may be socially isolated and excluded in ways that cause stress, and their parents might use food to reinforce or comfort them. The third layer the study adopted was the macrosystem. For example, some cultures discriminate against children with disabilities so that they face more difficulty gaining access to health services.

In the field of language teaching, Mohammadabadi et al. (2019) researched factors influencing language teaching cognition. They used an ecological framework to explore the factors influencing language teachers at different levels. They adopted the four systems from Bronfenbrenner’s theory for studying the issue. This study found that the ecological systems affect language teaching. For example, the microsystem included a direct influence on teachers’ immediate surroundings, such as facilities, emotional mood, teachers’ job satisfaction, and linguistic proficiency. The mesosystem defined interconnections between teachers’ collaboration and their prior learning experience. The exosystem included the teaching program and curriculum and teachers’ evaluation criteria, while the macrosystem addressed the government’s rules, culture, and religious beliefs. In other words, researchers use EST to guide the design of their studies and to interpret the results.

Model of EST

Concepts, Constructs, and Propositions

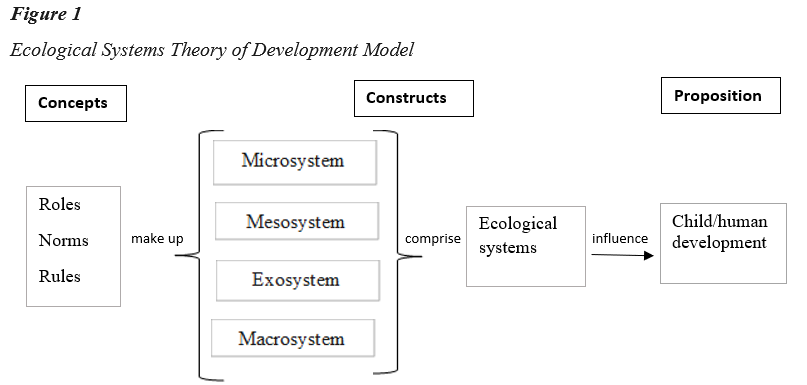

The four systems that Brofenbrenner proposed are constructed by roles, norm and rules (see Figure 1). The first system is the microsystem. The microsystem as the innermost system is defined as the most proximal setting in which a person is situated or where children directly interact face to face with others. This system includes the home and child-care (e.g., parents, teacher, and peers). The second is the mesosystem. The mesosystem is an interaction among two or more microsystems where children actively participate in a new setting; for instance, the relationship between the family and school teachers. The third is the exosystem. This system does not directly influence children, but it can affect the microsystem. The effect is indirect. However, it still may positively or negatively affect children’s development through the parent’s workplace, the neighborhood, and financial difficulties. The outermost system is the macrosystem. Like the exosystem, the macrosystem does not influence children directly; however, it can impact all the systems such as economic, social, and political systems. The influence of the macrosystem is reflected in how other systems, such as family, schools, and the neighborhood, function (Kitchen et al., 2019). These four systems construct the EST which considers their influences on child or human development.

Bronfenbrenner (cited in Harkonen, 2007) noted that those environments (contexts) could influence children’s development constructively or destructively. As the proposition, the system influences children or human development in many aspects, such as how they act and interact, their physical maturity, personal characteristics, health and growth, behavior, leadership skills, and others. At the end of the ecological system improvement phase, Bronfenbrenner also added time (the chronosystem) that focuses on socio-history or events associated with time (Schunk, 2016). In summary, the views of this ecological paradigm is that environment, social interaction, and time play essential roles in human development.

Using the Model

There are many possible ways to use the model as teachers and parents. For teaching purposes, teachers can use the model to create personalized learning experiences for students. The systems support teachers and school administrators to develop school environments that are suitable to students’ needs, characteristics, culture, and family background (Taylor & Gebre, 2016). Because the model focuses on the context (Schunk, 2016), teachers and school administration can use the model to increase students’ academic achievement and education attainment by involving parents and observing other contextual factors (e.g., students’ peers, extra-curricular activities, and neighbor) that may help or inhibit their learning.

Furthermore, the EST model can support parents to educate and guide their children. It can prompt parents to assist their children in choosing their friends and finding good neighborhoods and schools. Additionally, they can build close connections to teachers, so they know their children’ skills and abilities. By involving themselves in schools, parents can positively influence their children’s educational context (Hoover & Sandler, 1997).

For research purposes, researchers can test and modify or refine the EST proposition, or they can find additional ways to measure it. Researchers also can develop questionnaires from the components or concepts and construct of EST. Additionally, the four levels of EST can be used by researchers to frame qualitative, quantitative, and mixed research (Onwuegbuzie, et.al., 2013).

At first, EST was used in children’s development studies to describe their development in their early stages influenced by the person, social, and political systems. Currently, EST is broadly applied in many fields. Schools or educational institutions can use EST to improve students’ achievement and well-being. Interaction between the family, parents, teachers, community, and political system will determine students’ development outcomes.

Esolage, D. L. (2014). Ecological theory: Preventing youth bullying, aggression, and victimization. Theory into Practice. 53 , 257–264.

Harkonen, U. (2007, October 17). The Bronfenbenner ecological system theory of human development. Scientific Articles of V International Conference PERSON.COLOR.NATURE.MUSIC , Daugavpils University, Latvia, 1 – 17.

Heather, M.F. (2016). An ecological approach to understanding delinquency of youth in foster care . Deviant Behavior, 37 (2), 139 – 150.

Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., & Sandler, H. M. (1997). Why do parents become involved in their children’s education? Review of Educational Research , 67(1), 3–42. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543067001003

Kitchen, J. A, (list all authors in reference list) (2019). Advancing the use of ecological system theory in college students research: The ecological system interview tool. Journal of College Students Development, 60 (4), 381-400.

Martinello, E. (2020). Applying the ecological system theory to better understanding and prevent child sexual abuse. Sexuality and Culture, 24 , 326-344

Mohammadabadi, A., Ketabi, S., & Nejadansari, D. (2019). Factor influencing language teaching cognition. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching. 9 (4), 657 – 680.

Onwuegbuzie, A.J., Collins, K.M.T., & Frels, R.K. (2013). Foreword. International Journal of Multiple Research Approaches, 7 (1), 2-8.

Schunk, D. H. (2016). Learning theory: An educational perspective . Pearson.

Taylor, R. D., & Gebre, A. (2016). Teacher–student relationships and personalized learning: Implications of person and contextual variables. In M. Murphy, S. Redding, & J. Twyman (Eds.), Handbook on personalized learning for states, districts, and schools (pp. 205–220). Temple University, Center on Innovations in Learning.

Walker, M., Nixon, S., Haines. J., & McPherson, A.C. (2019). Examining risk factors for overweight and obesity in children with disabilities: A commentary on Bronfenbrenner’s ecological system framework. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 22 (5), 359 – 364.

Share This Book

- Increase Font Size

Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory posits that an individual’s development is influenced by a series of interconnected environmental systems, ranging from the immediate surroundings (e.g., family) to broad societal structures (e.g., culture).

These systems include the microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem, and chronosystem, each representing different levels of environmental influences on an individual’s growth and behavior.

Key Takeaways

- Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory views child development as a complex system of relationships affected by multiple levels of the surrounding environment, from immediate family and school settings to broad cultural values, laws, and customs.

- To study a child’s development, we must look at the child and their immediate environment and the interaction of the larger environment.

- Bronfenbrenner divided the person’s environment into five different systems: the microsystem, the mesosystem, the exosystem, the macrosystem, and the chronosystem.

- The microsystem is the most influential level of the ecological systems theory. This is the most immediate environmental setting containing the developing child, such as family and school.

- Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory has implications for educational practice.

The Five Ecological Systems

Bronfenbrenner (1977) suggested that the child’s environment is a nested arrangement of structures, each contained within the next. He organized them in order of how much of an impact they have on a child.

He named these structures the microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem and the chronosystem.

Because the five systems are interrelated, the influence of one system on a child’s development depends on its relationship with the others.

1. The Microsystem

The microsystem is the first level of Bronfenbrenner’s theory and is the things that have direct contact with the child in their immediate environment.

It includes the child’s most immediate relationships and environments. For example, a child’s parents, siblings, classmates, teachers, and neighbors would be part of their microsystem.

Relationships in a microsystem are bi-directional, meaning other people can influence the child in their environment and change other people’s beliefs and actions. The interactions the child has with these people and environments directly impact development.

For instance, supportive parents who read to their child and provide educational activities may positively influence cognitive and language skills. Or children with friends who bully them at school might develop self-esteem issues. The child is not just a passive recipient but an active contributor in these bidirectional interactions.

2. The Mesosystem

The mesosystem is where a person’s individual microsystems do not function independently but are interconnected and assert influence upon one another.

The mesosystem involves interactions between different microsystems in the child’s life. For example, open communication between a child’s parents and teachers provides consistency across both environments.

However, conflict between these microsystems, like parents and teachers blaming each other for a child’s poor grades, creates tension that negatively impacts the child.

The mesosystem can also involve interactions between peers and family. If a child’s friends use drugs, this may introduce substance use into the family microsystem. Or if siblings do not get along, this can spill over to peer relationships.

3. The Exosystem

The exosystem is a component of the ecological systems theory developed by Urie Bronfenbrenner in the 1970s.

It incorporates other formal and informal social structures. While not directly interacting with the child, the exosystem still influences the microsystems.

For instance, a parent’s stressful job and work schedule affects their availability, resources, and mood at home with their child. Local school board decisions about funding and programs impact the quality of education the child receives.

Even broader influences like government policies, mass media, and community resources shape the child’s microsystems.

For example, cuts to arts funding at school could limit a child’s exposure to music and art enrichment. Or a library bond could improve educational resources in the child’s community. The child does not directly interact with these structures, but they shape their microsystems.

4. The Macrosystem

The macrosystem focuses on how cultural elements affect a child’s development, consisting of cultural ideologies, attitudes, and social conditions that children are immersed in.

The macrosystem differs from the previous ecosystems as it does not refer to the specific environments of one developing child but the already established society and culture in which the child is developing.

Beliefs about gender roles, individualism, family structures, and social issues establish norms and values that permeate a child’s microsystems. For example, boys raised in patriarchal cultures might be socialized to assume domineering masculine roles.

Socioeconomic status also exerts macro-level influence – children from affluent families will likely have more educational advantages versus children raised in poverty.

Even within a common macrosystem, interpretations of norms differ – not all families from the same culture hold the same values or norms.

5. The Chronosystem

The fifth and final level of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory is known as the chronosystem.

The chronosystem relates to shifts and transitions over the child’s lifetime. These environmental changes can be predicted, like starting school, or unpredicted, like parental divorce or changing schools when parents relocate for work, which may cause stress.

Historical events also fall within the chronosystem, like how growing up during a recession may limit family resources or growing up during war versus peacetime also fall in this system.

As children get older and enter new environments, both physical and cognitive changes interact with shifting social expectations. For example, the challenges of puberty combined with transition to middle school impact self-esteem and academic performance.

Aging itself interacts with shifting social expectations over the lifespan within the chronosystem.

How children respond to expected and unexpected life transitions depends on the support of their ecological systems.

The Bioecological Model

It is important to note that Bronfenbrenner (1994) later revised his theory and instead named it the ‘Bioecological model’.

Bronfenbrenner became more concerned with the proximal development processes, meaning the enduring and persistent forms of interaction in the immediate environment.

His focus shifted from environmental influences to developmental processes individuals experience over time.

‘…development takes place through the process of progressively more complex reciprocal interactions between an active, evolving biopsychological human organism and the persons, objects, and symbols in its immediate external environment.’ (Bronfenbrenner, 1995).

Bronfenbrenner also suggested that to understand the effect of these proximal processes on development, we have to focus on the person, context, and developmental outcome, as these processes vary and affect people differently (Bronfenbrenner & Evans, 2000).

While his original ecological systems theory emphasized the role of environmental systems, his later bioecological model focused more closely on micro-level interactions.

The bioecological shift highlighted reciprocal processes between the actively evolving individual and their immediate settings. This represented an evolution in Bronfenbrenner’s thinking toward a more dynamic developmental process view.

However, the bioecological model still acknowledged the broader environmental systems from his original theory as an important contextual influence on proximal processes.

The bioecological focus on evolving person-environment interactions built upon the foundation of his ecological systems theory while bringing developmental processes to the forefront.

Classroom Application

The Ecological Systems Theory has been used to link psychological and educational theory to early educational curriculums and practice. The developing child is at the center of the theory, and all that occurs within and between the five ecological systems are done to benefit the child in the classroom.

- According to the theory, teachers and parents should maintain good communication with each other and work together to benefit the child and strengthen the development of the ecological systems in educational practice.

- Teachers should also be understanding of the situations their student’s families may be experiencing, including social and economic factors that are part of the various systems.

- According to the theory, if parents and teachers have a good relationship, this should positively shape the child’s development.

- Likewise, the child must be active in their learning, both academically and socially. They must collaborate with their peers and participate in meaningful learning experiences to enable positive development (Evans, 2012).

There are lots of studies that have investigated the effects of the school environment on students. Below are some examples:

Lippard, LA Paro, Rouse, and Crosby (2017) conducted a study to test Bronfenbrenner’s theory. They investigated the teacher-child relationships through teacher reports and classroom observations.

They found that these relationships were significantly related to children’s academic achievement and classroom behavior, suggesting that these relationships are important for children’s development and supports the Ecological Systems Theory.

Wilson et al. (2002) found that creating a positive school environment through a school ethos valuing diversity has a positive effect on students’ relationships within the school. Incorporating this kind of school ethos influences those within the developing child’s ecological systems.

Langford et al. (2014) found that whole-school approaches to the health curriculum can positively improve educational achievement and student well-being. Thus, the development of the students is being affected by the microsystems.

Critical Evaluation

Bronfenbrenner’s model quickly became very appealing and accepted as a useful framework for psychologists, sociologists, and teachers studying child development.

The Ecological Systems Theory provides a holistic approach that is inclusive of all the systems children and their families are involved in, accurately reflecting the dynamic nature of actual family relationships (Hayes & O’Toole, 2017).

Paat (2013) considers how Bronfenbrenner’s theory is useful when it comes to the development of immigrant children. They suggest that immigrant children’s experiences in the various ecological systems are likely to be shaped by their cultural differences. Understanding these children’s ecology can aid in strengthening social work service delivery for these children.

Limitations

A limitation of the Ecological Systems Theory is that there is limited research examining the mesosystems, mainly the interactions between neighborhoods and the family of the child (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000). Therefore, the extent to which these systems can shape child development is unclear.

Another limitation of Bronfenbrenner’s theory is that it is difficult to empirically test the theory. The studies investigating the ecological systems may establish an effect, but they cannot establish whether the systems directly cause such effects.

Furthermore, this theory can lead to assumptions that those who do not have strong and positive ecological systems lack in development. Whilst this may be true in some cases, many people can still develop into well-rounded individuals without positive influences from their ecological systems.

For instance, it is not true to say that all people who grow up in poverty-stricken areas of the world will develop negatively. Similarly, if a child’s teachers and parents do not get along, some children may not experience any negative effects if it does not concern them.

As a result, people need to avoid making broad assumptions about individuals using this theory.

How Relevant is Bronfenbrenner’s Theory in the 21st Century?

The world has greatly changed since this theory was introduced, so it’s important to consider whether Bronfenbrenner’s theory is still relevant today.

Kelly and Coughlan (2019) used constructivist grounded theory analysis to develop a theoretical framework for youth mental health recovery and found that there were many links to Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory in their own more recent theory.

Their theory suggested that the components of mental health recovery are embedded in the ‘ecological context of influential relationships,’ which fits in with Bronfenbrenner’s theory that the ecological systems of the young person, such as peers, family, and school, all help mental health development.

We should also consider whether Bronfenbrenner’s theory fits in with advanced technological advancements in the 21st century. It could be that the ecological systems are still valid but may expand over time to include new modern developments.

The exosystem of a child, for instance, could be expanded to consider influences from social media, video gaming, and other modern-day interactions within the ecological system.

Neo-ecological theory

Navarro & Tudge (2022) proposed the neo-ecological theory, an adaptation of the bioecological theory. Below are their main ideas for updating Bronfenbrenner’s theory to the technological age:

- Virtual microsystems should be added as a new type of microsystem to account for online interactions and activities. Virtual microsystems have unique features compared to physical microsystems, like availability, publicness, and asychnronicity.

- The macrosystem (cultural beliefs, values) is an important influence, as digital technology has enabled youth to participate more in creating youth culture and norms.

- Proximal processes, the engines of development, can now happen through complex interactions with both people and objects/symbols online. So, proximal processes in virtual microsystems need to be considered.

Urie Bronfenbrenner was born in Moscow, Russia, in 1917 and experienced turmoil in his home country as a child before immigrating to the United States at age 6.

Witnessing the difficulties faced by children during the unrest and rapid social change in Russia shaped his ideas about how environmental factors can influence child development.

Bronfenbrenner went on to earn a Ph.D. in developmental psychology from the University of Michigan in 1942.

At the time, most child psychology research involved lab experiments with children briefly interacting with strangers.

Bronfenbrenner criticized this approach as lacking ecological validity compared to real-world settings where children live and grow. For example, he cited Mary Ainsworth’s 1970 “Strange Situation” study , which observed infants with caregivers in a laboratory.

Bronfenbrenner argued that these unilateral lab studies failed to account for reciprocal influence between variables or the impact of broader environmental forces.

His work challenged the prevailing views by proposing that multiple aspects of a child’s life interact to influence development.

In the 1970s, drawing on foundations from theories by Vygotsky, Bandura, and others acknowledging environmental impact, Bronfenbrenner articulated his groundbreaking Ecological Systems Theory.

This framework mapped children’s development across layered environmental systems ranging from immediate settings like family to broad cultural values and historical context.

Bronfenbrenner’s ecological perspective represented a major shift in developmental psychology by emphasizing the role of environmental systems and broader social structures in human development.

The theory sparked enduring influence across many fields, including psychology, education, and social policy.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the main contribution of bronfenbrenner’s theory.

The Ecological Systems Theory has contributed to our understanding that multiple levels influence an individual’s development rather than just individual traits or characteristics.

Bronfenbrenner contributed to the understanding that parent-child relationships do not occur in a vacuum but are embedded in larger structures.

Ultimately, this theory has contributed to a more holistic understanding of human development, and has influenced fields such as psychology, sociology, and education.

What could happen if a child’s microsystem breaks down?

If a child experiences conflict or neglect within their family, or bullying or rejection by their peers, their microsystem may break down. This can lead to a range of negative outcomes, such as decreased academic achievement, social isolation, and mental health issues.

Additionally, if the microsystem is not providing the necessary support and resources for the child’s development, it can hinder their ability to thrive and reach their full potential.

How can the Ecological System’s Theory explain peer pressure?

The ecological systems theory explains peer pressure as a result of the microsystem (immediate environment) and mesosystem (connections between environments) levels.

Peers provide a sense of belonging and validation in the microsystem, and when they engage in certain behaviors or hold certain beliefs, they may exert pressure on the child to conform. The mesosystem can also influence peer pressure, as conflicting messages and expectations from different environments can create pressure to conform.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1974). Developmental research, public policy, and the ecology of childhood . Child development, 45 (1), 1-5.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development . American psychologist, 32 (7), 513.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1995). Developmental ecology through space and time: A future perspective .

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Evans, G. W. (2000). Developmental science in the 21st century: Emerging questions, theoretical models, research designs and empirical findings . Social development, 9 (1), 115-125.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Ceci, S. J. (1994). Nature-nurture reconceptualised: A bio-ecological model . Psychological Review, 10 (4), 568–586.

Hayes, N., O’Toole, L., & Halpenny, A. M. (2017). Introducing Bronfenbrenner: A guide for practitioners and students in early years education . Taylor & Francis.

Kelly, M., & Coughlan, B. (2019). A theory of youth mental health recovery from a parental perspective . Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 24 (2), 161-169.

Langford, R., Bonell, C. P., Jones, H. E., Pouliou, T., Murphy, S. M., Waters, E., Komro, A. A., Gibbs, L. F., Magnus, D. & Campbell, R. (2014). The WHO Health Promoting School framework for improving the health and well‐being of students and their academic achievement . Cochrane database of systematic reviews, (4) .

Leventhal, T., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2000). The neighborhoods they live in: the effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes . Psychological Bulletin, 126 (2), 309.

Lippard, C. N., La Paro, K. M., Rouse, H. L., & Crosby, D. A. (2018, February). A closer look at teacher–child relationships and classroom emotional context in preschool . In Child & Youth Care Forum 47 (1), 1-21.

Navarro, J. L., & Tudge, J. R. (2022). Technologizing Bronfenbrenner: neo-ecological theory. Current Psychology , 1-17.

Paat, Y. F. (2013). Working with immigrant children and their families: An application of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory . Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 23 (8), 954-966.

Rhodes, S. (2013). Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Theory [PDF]. Retrieved from http://uoit.blackboard.com

Wilson, P., Atkinson, M., Hornby, G., Thompson, M., Cooper, M., Hooper, C. M., & Southall, A. (2002). Young minds in our schools-a guide for teachers and others working in schools . Year: YoungMinds (Jan 2004).

Further Information

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1974). Developmental research, public policy, and the ecology of childhood. Child Development, 45.

Related Articles

Child Psychology

Vygotsky vs. Piaget: A Paradigm Shift

Interactional Synchrony

Internal Working Models of Attachment

Soft Determinism In Psychology

Branches of Psychology

Learning Theory of Attachment

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

The Social Ecology of Childhood and Early Life Adversity

Marcela lopez.

1 Pain/Stress Neurobiology Lab, Maternal & Child Health Research Institute, Stanford University School of Medicine

Monica O. Ruiz

2 Department of Pediatrics, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA

Cynthia R. Rovnaghi

Grace k-y. tam, jitka hiscox.

3 Department of Civil Engineering, Stanford School of Engineering, Stanford, CA

Ian H. Gotlib

4 Department of Psychology, Stanford University School of Humanities & Sciences, Stanford, CA

Donald A. Barr

5 Stanford University Graduate School of Education, Stanford, CA

Victor G. Carrion

6 Department of Psychiatry (Child and Adolescent Psychiatry), Clinical & Translational Neurosciences Incubator, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA

Kanwaljeet J. S. Anand

Author Contributions:

An increasing prevalence of early childhood adversity has reached epidemic proportions, creating a public health crisis. Rather than focusing only on adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) as the main lens for understanding early childhood experiences, detailed assessments of a child’s social ecology are required to assess ‘early life adversity’. These should also include the role of positive experiences, social relationships, and resilience-promoting factors. Comprehensive assessments of a child’s physical and social ecology not only require parent/caregiver surveys and clinical observations, but also include measurements of the child’s physiology using biomarkers. We identify cortisol as a stress biomarker and posit that hair cortisol concentrations represent a summative and chronological record of children’s exposure to adverse experiences and other contextual stressors. Future research should use a social ecological approach to investigate the robust interactions among adverse conditions, protective factors, genetic and epigenetic influences, environmental exposures, and social policy, within the context of a child’s developmental stages. These contribute to their physical health, psychiatric conditions, cognitive/executive, social, and psychological functions, lifestyle choices, and socioeconomic outcomes. Such studies must inform preventive measures, therapeutic interventions, advocacy efforts, social policy changes, and public awareness campaigns to address early life adversities and their enduring effects on human potential.

The social ecology of childhood includes positive and negative experiences, providing children with a socio-biological framework to meet age-specific developmental goals. Disruptions in this ecology, including frequent low-grade stressors (insecurity, inattention), marked variability (life changes), and trauma (abuse/neglect), can have deleterious effects on children’s health and wellbeing that may continue into adulthood ( 1 , 2 ). Researchers studying the lifelong effects of a child’s social ecology have focused primarily on major adverse events. Metrics like the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) questionnaire are administered in public health efforts to evaluate, understand, and prevent the health outcomes associated with childhood trauma( 3 , 4 ). Beyond the ACEs, however, preventable sources of early life stress may include food and housing insecurity, bullying, discrimination, inattentive parenting, or family separations. Clinicians do not routinely screen for trauma or the child’s social ecology, partly due to the lack of validated, objective metrics that can be assessed longitudinally.

We review the current discourse on the social ecology of early childhood in relation to child, adolescent, and adult health outcomes, summarize previous social ecology theories, and compare quantitative metrics. We argue that the practice of using ACEs as a method for understanding early life experiences paints a two-dimensional picture of the many interacting factors that comprise a growing child’s multi-dimensional environment. We review the underlying physiology of neuroendocrine stress responses and further contend that biomarkers, such as hair cortisol concentrations (HCC), may provide critical insights into the relations among early adversity, stress, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA)-axis regulation, and subsequent health outcomes.

Social Ecology of Childhood: A Historical Perspective

French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) first proposed that early childhood experiences establish adult behaviors. Lev Vygotsky (1896-1934) from Moscow proposed the role of social and cultural factors in his theory of speech development, described in his book Thought and Language (1934). This work influenced many, including Jean Piaget (1896-1980), to propose theories of cognitive development in early childhood. Thomas and Znaniecki established a life-course perspective through their longitudinal studies (1918-1920) of Polish peasants in Europe and America( 5 ). Across the 20 th century( 6 – 10 ), early childhood experiences were associated with cognitive, behavioral, social, and psychological outcomes, including the influences of family size and socioeconomic status( 9 ), kindergarten enrollment( 11 , 12 ), and social class( 8 ).

These factors were integrated into the Ecological Systems Theory by Urie Bronfenbrenner (1979), a Russian-American psychologist. Bronfenbrenner conceptualized that human development is shaped by complex relationships between individuals and their environments( 13 ). He argued that contemporary understanding of human development had failed to consider interactive, layered systems within a child’s environment( 14 ). These limitations led him to develop his Ecological Systems model.

Bronfenbrenner’s model depicts four systems – the microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, and macrosystem – embedded in a chronosystem representing the era in which an individual grows up ( Figure 1 ). The microsystem comprises of interactions, roles and relationships within the home, child-care centers, or playgrounds( 13 ). The interplay among different microsystems is the mesosystem ( 13 ). The exosystem consists of extrinsic environments that affect the child indirectly (where the child is not an active participant), like the parents’ work environments, sibling’s school, or local government( 13 ). Lastly, the macrosystem encompasses greater societal characteristics, such as norms, customs, beliefs, and political structures. Bronfenbrenner’s model serves as a useful tool for exploring, categorizing, and interpreting different facets of children’s environments and experiences. It identifies a plethora of micro- and macro-level characteristics and encourages us to consider factors that impact a child’s life outside their insular family unit. This model presented a major breakthrough in theorizing the complicated structures of multicultural/multiethnic societies, and allowed us to organize complex, hierarchical systems within a Person, Process, Context, and Time (PPCT) framework( 15 ) to address issues at the core of programs and policies targeting children at the family and community level.

Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory presented a breakthrough model for theorizing how the complex, hierarchically organized systems in societies can interact with a child’s life, with a rich interplay between systems leading to the variable or opposing effects on early life adversity (ELA).

Other conceptual models have since been developed to assess the relationship between children’s broader social contexts and their health. In his 1992 book, The Strategies of Preventive Medicine , Geoffrey Rose stated that “the primary determinants of disease are mainly economic and social, and therefore its remedies must also be economic and social”( 16 ). His colleagues, Michael Marmot and Richard Wilkinson, as part of a World Health Organization initiative, expanded on his work to identify the social and economic characteristics which significantly influenced individuals’ well-being and life expectancy, and referred to these as the Social Determinants of Health( 17 ). They focused on poverty, drug addiction, working conditions, unemployment status, access to food, social support, and transportation infrastructure. Other determinants identified since then include social organization, race/ethnicity, gender, immigrant status, neighborhood and housing characteristics( 17 ).

The Life Course Theory emphasizes the timing and temporal context of lived experiences and how they can impact an individuals’ development and wellbeing( 18 ). In response to the “ notion that changing lives alter developmental trajectories ”( 18 ), Glen H. Elder proposed the four principles of Life Course Theory in 1998 as: ( 1 ) “ the life course of individuals is embedded in and shaped by historical times and places they experience over their lifetime ”; ( 2 ) “ the developmental impact of a succession of life transitions or events ”; ( 3 ) “ lives are lived independently, and social and historical influences are expressed through this network of shared relationships ”; and ( 4 ) “ individuals construct their own life course through the choices and actions they take within the opportunities and constraints of history and social circumstances ”( 18 ).

Epidemiologist Nancy Krieger proposed the concept of “embodiment” in 2005, which she defined as “ referring to how we literally incorporate biologically, the material and social world in which we live, from conception to death ,” arguing that human biology could not be understood without “ knowledge of history and individual and societal ways of living ”( 19 ). Through this lens, human interactions “become” human biology. Anthropologist Clarence Gravlee applied this concept to explain how and why racialized experiences and social constructs can negatively impact the health of racial and ethnic minorities in the U.S.( 20 ).

Despite widespread acceptance of these theoretical constructs, most studies focus solely on adversities within the home, testing their associations with physical( 21 – 24 ) and mental health outcomes( 25 ). Many authors use the term early life stress (ELS) to link adverse experiences in a child’s life with negative health outcomes( 1 , 2 , 26 – 28 ); other scholars refer to this phenomenon as “toxic stress”( 29 , 30 ), with no consensus on the nomenclature used to describe relationships between childhood adversity and potential health outcomes. While the ‘stress’ caused by adversity may explain many long-term consequences, ‘stress’ is not the operative factor for all observed outcomes( 1 , 26 ). Instead, we prefer early life adversity (ELA) as a holistic term, including family functions, socioeconomic factors, social supports, neighborhood characteristics, and other factors, more suited for linking early adversities with long-term outcomes. Several measures have been developed to study ELA, with most relying on adult retrospective recall.

Measures of Early Life Adversity

Several inventories, systematically reviewed by Vanaelst et al.( 31 ), assess the frequency of adverse childhood events( 31 ) ( Table 1 ). These were adapted from existing stress questionnaires and modified to inquire about major life events, chronic environmental strains (family, school, relationships, health), and other childhood-related stressors( 31 – 33 ). A cumulative risk approach was first proposed by Holmes and Rahe in their Social Readjustment Rating Scale ( 34 ), then applied to child adversities by Rutter( 35 ), and subsequently followed in other studies( 36 , 37 ). This approach rests on the scientific premise that challenges in one domain are easier to negotiate than challenges in multiple domains. It was simple to use, easy to understand, generated strong statistical associations to engage non-academic stakeholders( 38 ), accounted for the co-occurrence of childhood adversities( 39 ), and helped to identify people at highest risk for poor outcomes( 24 ).

Early Life Adversity Screening Tools

Against this backdrop, Vincent Felitti decided to focus on a specific set of ACEs. Felitti observed that dropouts from an adult obesity program had experienced adverse events as children or youth( 40 ). Detailed patient interviews revealed that childhood abuse was common and predated their obesity; thus, obesity was a self-protective solution to prior adverse experiences and not their primary problem. With Robert Anda and others, Felitti designed the ACEs Study, which surveyed 9,508 adults about ten adverse experiences( 32 , 41 – 43 ). Compared to individuals with no ACEs, persons exposed to four or more ACEs had 4- to 12-fold higher risks for drug abuse, alcoholism, depression, and suicide, 2- to 4-fold increased risks for smoking, poor health, multiple sexual partners, and sexually transmitted diseases, and 1.4- to 1.6-fold increased risks for physical inactivity and obesity( 38 , 40 ). ACEs also showed linear relations with heart disease, cancer, lung disease, fractures, liver disease, and multiple health outcomes.

By summing a fixed number of ACEs, Felitti and others created a quantitative method for estimating childhood adversities( 38 , 40 ). Their work stimulated research, social policy, and public health measures to combat the increasing prevalence of ACEs, and extended the movement for trauma-informed care into the pediatric age groups( 33 ).

Prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences

The increasing prevalence of ACEs is a major public health concern( 31 , 32 , 44 , 45 ). In the ACEs study, 63.5% of adults recalled at least one ACE and 12% recalled 4 or more ACEs( 46 ). Subsequent studies, not limited to adult respondents, reported higher prevalence rates of 67%-98%( 47 – 49 ). Preschool children are at greatest risk for child abuse and neglect( 50 ), or domestic violence( 40 , 51 ), but cannot report these experiences due to limited behavioral or verbal expressions( 40 ). ACEs in early childhood remain underreported and underestimated( 30 , 39 , 50 , 52 ).

The U.S. Children’s Bureau reported that 678,000 children suffered abuse and neglect in 2018, with a crude prevalence rate of 9.2 per 1000 children. Of these, 60.8% were neglected, 10.7% physically abused, 7.0% sexually abused, and 15.5% suffered two or more types of abuse( 53 ). Although caregivers often minimize or fail to report the maltreatment of preverbal children( 54 ), children under 1 year of age had the highest rates of abuse (26.7 per 1000 children). In 2018, 1,770 children died of abuse/neglect (case fatality rate 2.39 per 100,000 children), with the highest case fatality rates in infants below 1-year (case fatality rate 22.8/100,000 children)( 53 ). Cumulative exposures have multi-layered effects on child development, with a “mediated net of adversity” that simultaneously augments their risk across cognitive, quality of life, social, economic, psychiatric, and physical health outcomes( 55 ).

Health Implications of Adverse Childhood Experiences

A systematic review of pediatric health outcomes associated with ACEs found prospective evidence for impaired physical growth and cognitive development, higher risks for childhood obesity, asthma, infections, non-febrile illnesses, disordered sleep, delayed menarche, and non-specific somatic complaints( 56 ). These outcomes depended on the ACE characteristics, age of occurrence, and specific types of exposures. For example, prospective studies showed that parental discord or violence were associated with obesity in childhood( 57 , 58 ), whereas prospective studies showed that physical or sexual abuse were associated with youth obesity( 59 – 61 ). From prospective data, Brown et al. clustered the specific ACEs that led to specific risks, to form an ACEs-directed tree for identifying health outcomes( 41 ). For each additional ACE, children were 29-44% more likely to have complex health problems, with multiple needs across developmental, physical, and mental health( 41 ).

Children aged 2-5 years exposed to caregiver mental illness were most likely (56-57%) to have complex health concerns, with the additive effects of other risk factors( 41 ). A significantly higher prevalence of four or more ACEs was found in children with multiple unexplained chronic symptoms in six functional domains (executive dysfunction, sleep disturbances, autonomic dysregulation, somatic complaints, digestive symptoms, emotional dysregulation) compared to matched controls (88% vs. 33%)( 62 ); suggesting a syndrome of nervous system dysregulation in these children, much like that seen in Gulf War veterans( 63 ).

Retrospective studies based on adult recall linked ACEs with an increased vulnerability to chronic non-communicable diseases, substance abuse, sexual risk-taking behaviors( 52 , 64 – 69 ), suicide, domestic violence( 66 , 70 – 73 ), and worse physical and mental health( 44 , 74 – 77 ). From 24,000 adults in the World Mental Health Surveys, retrospective data on childhood adversities doubled the risk of adult psychotic episodes, accounting for 31% of psychotic episodes globally( 78 ). Sexual abuse, physical abuse, and parent criminality had the strongest associations with later psychotic episodes( 78 ).

A meta-analysis of adult health outcomes following four or more ACEs found increased risks for all 23 health and social outcomes, with weak associations for physical inactivity, weight gain, and diabetes; moderate associations for smoking, heavy alcohol use, poor self-rated health, cancer, heart, lung, and digestive diseases; stronger associations for sexual risk-taking, mental ill health, problematic alcohol use, and decreased life satisfaction; and the strongest associations for drug abuse, interpersonal violence, and suicide( 79 ) ( Table 2 ). Thus, ACEs not only contribute to global burdens of adult disease, but their strongest associations with drug abuse, domestic violence, and suicide may directly inflict ACEs onto the next generation( 80 – 82 ).

Outcomes following exposure ≧4 to Adverse Childhood Experiences

Pooled Odds Ratios (ORs) from random effects meta-analyses.

(Modified with permission from: Hughes, et al., Lancet Public Health 2017, 2: e356-e366 (ref. 64 ))

Genetic and Epigenetic Changes:

These intergenerational effects are accentuated via altered gene expression through conserved transcriptional responses to adversity( 83 ), coupled with epigenetic changes such as telomere shortening, reduced stem cell populations, elevated methylation and nitration states among genes in the stress-responsive, inflammation, or other pathways( 84 – 87 ). Stress-associated epigenetic changes contribute to aberrant neuronal plasticity ( 88 ), affect disorders ( 88 ), post-traumatic stress disorder, alcohol use disorder ( 89 ) and depression ( 90 – 93 ), transmitting their physical and mental health risks to future generations( 79 , 94 , 95 ). Mechanisms of stress-associated epigenetic changes may involve DNA methylation or histone acetylation( 90 , 92 , 96 2015, 97 ), changes in mitochondrial DNA copy number and mitochondrial dynamics( 97 ), and microRNAs which are transported via exosomes or binding proteins( 98 ) to regulate the signaling pathways for gene silencing, cellular differentiation, autophagy, and apoptosis( 99 ).

From a systematic review of epigenetic changes in HPA-axis genes, Argentieri et al. found prospective evidence for methylation of HSD11beta2 with hypertension, NR3C1 with small cell lung cancer and breast cancer, FKBP5 and NR3C1 with PTSD, as well as plausible associations of FKBP5 methylation with Alzheimer’s Disease( 84 ). In particular, the glucocorticoid nuclear receptor gene NR3C1 undergoes methylation in varying gene regions from different social and environmental exposures, associated with different mental health outcomes( 84 ).

Focusing solely on PTSD-associated genetic changes, Blacker et al. found 3989 genes upregulated and 3 genes downregulated from 4 GWAS studies in PTSD patients( 85 ). Among the differentially methylated genes, DOCK2 (dedicator of cytokinesis 2) and MAN2C1 (α-mannosidase) were associated with immune system dysregulation in PTSD subjects( 85 ). Urban African-American males with PTSD showed increased global DNA methylation and differential DNA methylation in several genes: decreased in TPR (nuclear membrane trafficking) and ANXA2 genes (calcium-regulated membrane-binding protein), increased in CLEC9A (activation receptor on myeloid cells), ACP5 (leukemia-associated glycoprotein), and TLR8 genes (innate immunity activation)( 100 ). In African-American women with PTSD, this study found a higher methylation of the histone deacetylase 4 gene (HDAC4)( 100 ). A systematic review of stress-associated epigenetic changes and depression found differential methylation of NRC31, SLCA4, BDNF, FKBP5, SKA2, OXTR, LINGO3, POU3F1 and ITGB1, associated with altered glucocorticoid signaling (NR3C1, FKBP5), serotonergic signaling (SLC6A4), and neurotrophin genes (BDNF)( 87 ). Another systematic review confirmed that ELS-triggered epigenomic modulation of NR3C1 was correlated with major depressive disorder( 101 ).

Childhood socioeconomic deprivation and ACEs can lead to adult diseases by increasing their inflammatory burden via multiple genetic factors, including single nucleotide polymorphisms, and epigenetic factors, including nuclear factor-kappaB (NFκB)-mediated gene methylation and histone acetylation. These changes increase expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, reactive oxygen species, reactive nitrogen species and induce several microRNAs (miR-155, miR-181b-1, miR-146a), with widespread effects on the immune system( 86 ). ELA also alters HPA-axis reactivity in adulthood by (i) genetic factors, such as glucocorticoid receptor polymorphisms; (ii) epigenetic factors altering glucocorticoid receptor function, including methylation of NR3C1, FKBP5, and HSD11beta2; (iii) chronic inflammation due to chronic nitrosative and oxidative stress; and (iv) brain mitochondrial DNA copy number and transcription, with altered mitochondrial dynamics, structure, and function in adulthood( 86 ).

Limitations of the ACEs Score

Despite the known effects of ACEs on genetic/epigenetic changes and long-term health outcomes, it is short-sighted to focus only on ACEs for clinical decisions related to ELA. Newer frameworks must include factors ignored by ACEs scores, including (a) the age of onset and offset; (b) severity of trauma ; (c) frequency of traumatic events; (d) periodicity of trauma within specific developmental periods; (e) concurrence of traumatic events; and (f) multiplicity of events across childhood( 102 ). Thus, popular use of the ACEs score as a proxy for toxic stress appears grossly inadequate.

The American Academy of Pediatrics defines toxic stress “as the excessive or prolonged activation of physiologic stress response systems in the absence of the buffering protection afforded by stable, responsive relationships”( 29 , 30 ). However, toxic stress depends on the child’s complete social ecology, including multiple variabilities in their adverse experiences, environmental conditions, and protective factors( 1 , 33 , 103 , 104 ). Lacey et al. argued that because all ACEs do not carry the same emotional weight or elicit similar distress levels , binary “yes/no” responses cannot represent their impact on the child( 46 ). Lack of consistency in defining ACEs also makes it difficult to compare childhood adversities across different studies( 46 ); further limited by the lack of self-report, absence of protective factors, and dependence on caregiver report( 31 , 46 ). Caregivers may be more inclined to report their child’s behaviors as “problematic” than to divulge personal difficulties, family dynamics, or household dysfunctions( 31 ).

The ACEs score originated as an epidemiological research tool based on adult interpretations of their childhood experiences, but has since been extrapolated to clinical settings( 105 , 106 ). California launched a public health initiative in 2020 to screen children for ACEs in all outpatient visits( 45 ). However, there is limited practical experience of ACEs screening in the clinic, limited resources to address the identified ACEs, and nominal evidence-based algorithms for managing children with multiple ACEs( 31 , 46 ). If clinic-screened ACEs do not relate to recent trauma and the patient appreas asymptomatic, the next steps remain unclear( 42 , 45 ). Potential outcomes of this policy may include unnecessary referrals to Child Protective Services or pediatric subspecialists( 32 , 45 ). The inconsistent description of ACEs in different inventories highlights the broader point that there is no consensus on how to define childhood adversity or grade its intensity( 46 ). This has serious implications for how the ACEs questionnaire is used outside of epidemiology, especially to inform clinical, social, or policy interventions.

Other Factors in the Social Ecology of Childhood

ELA incorporates broader features beyond the individual experiences identified as ACEs( 107 ). For instance, the association between ACEs and child health was strengthened when researchers also accounted for interpersonal victimization (community violence, property crime, bullying), highlighting the cumulative harm from different forms of trauma( 70 ). ELA can be attributed to factors within all ecological systems affecting individuals, families, communities, or broader societies( 52 , 108 ). The rich interplay between these systems must be emphasized, since significant ecological factors are not “stand-alone” but can alter multiple systems at once.

Individual factors:

Effects of childhood adversity typically emphasize the unidirectional effect of negative experiences on child development, disregarding individual demographics or personality factors. Substantial theoretical work on child development highlights the transactional and dynamic interplay between individuals and their environment( 109 ). Sameroff and Chandler consider developmental outcomes to be a function of such transactions, which exert continual effects on one another( 110 ). Similarly, individuals function as active and self-regulating entitities, changing dynamically with the environment and also changing their environment( 111 ). Thus, explanations for emerging health outcomes must account for mutual interactions between individual children and their environmental inputs( 109 ).

Household Factors:

Family environments, characterized by overt conflict, neglect, passive aggression, or unaffectionate interaction styles( 112 ) are associated with a broad range of mental and physical health disorders( 40 , 113 ). Parental traumatic experiences and environments can affect the quality of parenting and child development( 113 ). Maternal depression and trauma are associated with increased rates of insecure attachment in children( 114 – 117 ), related to decreased maternal responsiveness and affective availability( 114 , 118 , 119 ).

Sustained economic problems affect children directly by limiting material resources and indirectly through parental distress, which undermines the parents’ capacity for supportive and consistent parenting( 120 ) , ( 121 ). For example, fathers facing financial losses became more irritable, tense, and explosive, with punitive, rejecting, and inconsistent disciplining behaviors, associated with emotional difficulties in their children( 121 – 123 ).

Community Factors:

Neighborhood deprivation negatively impacts mental and physical health lasting into adulthood( 124 ), likely related to telomere shortening( 125 , 126 ), altered cortisol regulation( 126 ), increased inflammation( 127 ), and differential DNA methylation( 128 ). Children who grow up in communities with higher rates of violence, crime, and noise may suffer from increased stress and lasting trauma( 129 – 131 ). Poor local infrastructure can also affect access to resources such as food and healthcare which can exacerbate health issues( 131 ).

Broader Societal Factors:

Negative societal attitudes and biases, like racial discrimination or segregation, pervade all aspects of a child’s ecology and persist over time; therefore evaluating these factors is particularly important for long-term health outcomes in children of color( 132 – 134 ). Perceived racial discrimination and stereotype threat can trigger stress responses and can affect cognitive processes and academic performance( 135 ). For example, greater perceived discrimination was associated with greater cortisol output in Mexican–American youth( 136 ). Childhood exposures to interpersonal racial discrimination and structural racism stemming from media, schools, law enforcement, government policies, and other cultural stressors also lead to psychological distress and changes in allostatic load for racial minorities in the U.S.( 133 , 134 ). While negative inputs clearly affect the developing brain, positive inputs and protective factors, such as social buffering or individual resilience play equally important roles( 109 , 137 )( Figure 2 ).

Adverse and protective factors in a child’s life are organized by Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems model. Governmental, socioeconomic and cultural factors in the macrosystem may steer the child’s exosystem either towards adversity or adaptation. ELA (red box/arrows) and adaptation (green box/arrows) may work in tandem to build a child’s resilience, support education, income adequacy, health equity, and access to basic social services. The mesosystem forms an interface between the exosytem and the family unit with variable effects on the child’s milieu. In the microsystem, children are exposed to ELA or pro-social affiliations that affect their developmental, cognitive, behavioral, and health outcomes.

Protective Factors in the Child’s Social Ecology

ELA research must account for the factors that temper adversity, including support, temperament, resilience, and adaptation. For example, the Risky Families questionnaire includes supportive factors (e.g., parental love and support, household dynamics) and ACEs( 138 ). Although stress biology is highly susceptible to early experiences, it is just as malleable to supportive and protective factors( 139 , 140 ). We discuss the role of positive experiences, social relationships, and resilience factors that help children cope with adversity.

Positive Experiences:

Greater emphasis on positive and supportive experiences, fundamental to developing healthy brain architectures and buffering children against the effects of contextual stressors( 141 , 142 ), would complement existing data on the health consequences of ELA. A validated method to assess positive/protective experiences in ELA is the Benevolent Childhood Experiences scale( 143 ).

The Healthy Outcomes from Positive Experiences (HOPE) framework led by Sege and colleagues focuses on promoting positive childhood experiences to prevent or mitigate the effects of ELA. HOPE creates a strong foundation for learning, productive behavior, physical, and mental health( 144 ). Given that young children experience their world through their relationships with parents and other caregivers, positive childhood experiences that engage the child, the parent, and the parent-child relationship are essential( 141 , 142 ). In Wisconsin, positive childhood experiences were associated with dose-dependent reductions in the adult mental health and relational health impairments resulting from ACE exposures( 145 ).

HOPE identifies 4 broad categories of positive experiences and their effects on child development. ( 1 ) Sustained supportive relationships are associated with better physical and mental health, fewer behavior problems, higher educational achievement, more productive employment, and less involvement with social services and criminal justice systems( 141 ). ( 2 ) Growing and learning in safe, stable environments are important for children’s physical, emotional, social, cognitive development, and behavioral health, conferring lifelong benefits( 141 , 146 ). ( 3 ) Opportunities for constructive social engagement and connectedness can promote secure attachment, belonging, personal value, and positive regard( 141 , 147 , 148 ). ( 4 ) Social and emotional competencies cultivate self-awareness and confidence, laying the foundation for learning and problem-solving, identity development, communication skills, and secure personal relationships( 141 ).

Social Relationships:

John Bowlby observed that children separated from their mothers showed intense distress and later maladjustments. In the Attachment Theory , he posited that uninterrupted, secure maternal-infant bonding was evolutionarily adaptive( 149 ). Beginning with maternal-infant bonding, the layering of nurturing, supportive relationships throughout child development enriches self-perception, self-image, and coping skills. Positive social relationships also reduce pain ratings, HPA-axis reactivity, and aberrant brain activation( 150 – 154 ). Perceived social support from friends (not family members) was associated with fewer trauma symptoms in adult survivors of childhood maltreatment( 155 ). Culture-related protective factors can also be leveraged to overcome ELA and promote normal development( 156 ). Thus, social connections with family and non-family members may protect against stress responses to adversity across the lifespan.

Resilience:

Resilience science grew out of concerted efforts to understand, prevent, and treat mental health problems( 157 ). Scientists observed that some children adapted remarkably well despite high levels of adversity. Resilience generally refers to the capacity of any system to recover from exposure to stressors or adversity; it is a mirror image of vulnerability, with processes and capacities common to both( 158 – 160 ). Feldman argues that the construct of resilience involves systems and processes that tune the brain to its social ecology and adapt to its hardships( 161 ). In traumatized children, Happer et al. found stronger evidence for resilience as a process, partial support for resilience as an outcome, but none for resilience as a trait( 162 ).

While resilience research is summarized elsewhere( 160 , 161 , 163 , 164 ), an emerging list of resilience factors in children is featured in Table 3 ( 160 ). Resilience science distinguishes between protective and promotive factors; protective factors have greater effects in the context of adversity, but promotive factors improve outcomes more broadly( 160 , 165 , 166 ).

Resilience-Associated Factors in the Child’s Social Ecology

Adapted from Table 2 in Masten and Barnes 2018 .

Early life adversities, particularly in the absence of protective factors, can trigger a set of emotional responses, metabolic adjustments, physical/behavioral responses, and immune changes contributing to allostasis through the “fight or flight or freeze response” . Many stress responses are regulated through the neuroendocrine system, studied most extensively for the HPA axis.

Neuroendocrine Regulation of Stress Responses

Stress activates the neuroendocrine system, resulting in cortisol and catecholamine release( 31 , 44 ). The stress response evolves through two phases: the first is dominated by catecholamine release, and the second by cortisol. Simultaneous activation of the salience neuronal network and deactivation of the executive control network mediate the first phase( 44 ). The salience network includes the anterior insula, amygdala, hippocampus, striatum, medial prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortices; it integrates cognitive processes for responding to threats, with swift actions to promote survival( 44 , 167 ). The executive control network includes prefrontal and parietal cortices to mediate working memory, impulse control, and emotional regulation( 44 , 167 ). The second phase mediates recovery from stress responses by deactivating the salience network and re-engaging executive control. Such restoration of homeostasis after stress is termed the “adaptive stress response”( 44 ).

Emotional stimuli can activate salience network activity at lower thresholds in the “maladaptive stress response,” resulting in conditioned hyperarousal( 44 ). Allostasis, the HPA-axis adaptation to stress, is maintained in maladaptive stress responses, although resulting in somewhat delayed homeostasis( 31 , 44 , 167 ). Allostatic load results from the repetitive activation of HPA mechanisms attempting to restore homeostasis without returning to baseline( 44 ). Excessive HPA activation causes allostatic components to be unbalanced, leading to architectural and functional changes in the salience and executive control networks( 31 , 43 , 167 , 168 ). Indeed, higher bedtime cortisol levels predicted the reduced prefrontal cortex volumes in traumatized adolescents( 169 ). Chronic adversities overload the neuroendocrine system’s capacity to maintain homeostasis and, especially during periods of heightened neuroplasticity (from prenancy to early childhood), affect crucial aspects of brain development implicated in cognition, self-regulation, physical and mental health( 41 , 43 , 44 , 167 ).

The HPA axis and executive functions mature by age 4-6 years( 170 – 172 ), and a normally functioning HPA axis limits cortisol exposures through negative feedback loops to the anterior pituitary and hypothalamus. These negative feedback loops become ineffective in children with HPA-axis dysregulation( 173 ). Thus, toxic stress may lead to hyper- or hypo-responsivity of the HPA axis, with failed adaptation and eventual exhaustion( 174 ) ( Figure 3 ). HPA-axis dysregulation manifests as emotional problems in preschool children such as internalizing and externalizing behaviors( 175 – 179 ). Considering the harmful manifestations of HPA-axis dysregulation in children and vulnerability of their immature HPA-axis, it is critical that we establish biomarkers for screening preschool children.

Representative patterns of adaptive (green) and dysregulated (red) HPA-axis responses. In the perinatal phase, the fetal brain may be exposed to maternal cortisol levels resulting from prenatal stress, usually associated with dampening of the infant’s HPA-axis postnatally, often lasting into infancy and early childhood. Exposures to ELA/stress then manifest as hyperactive responses to acute stress, which, if prolonged or repetitive, can lead to chronically dysregulated diurnal rhythms and HPA-axis exhaustion.

Cortisol as a Biomarker of Early Life Adversity

Long-term consequences of ELA are mediated through the neuroendocrine system, with downstream effects on neuroimmune, neuroenteric, and cardiometabolic regulation( 43 , 50 ). Measuring stress biomarkers could overcome the inherent limitations of subjective questionnaires and difficulties of implementing the ACEs checklist in children( 44 ). Cortisol, the end-product of HPA-axis activation, regulates the HPA axis through negative feedback loops, activates the autonomic nervous system, alters intermediary metabolism, modulates physiological and immune responses, and contributes to the memory and learning from traumatic experiences( 180 , 181 ). Therefore, cortisol is an important biomarker for ELA( 182 ).

Plasma, salivary, or urinary cortisol levels reflect acute stress reactivity but cannot assess chronic stress because of its diurnal cycles, high state reactivity, pulsatile secretion patterns, and robust changes across age, sex, reproductive cycles, and food intake( 183 – 185 ). A systematic review concluded that HCC represents a measure recent stress, but it included studies from 16 species, which only collected cross-sectional data( 186 ). Measuring acute cortisol responses has significant limitations; repeated sampling over prolonged periods is time-consuming, expensive, and subject to non-compliance. Blood sampling is painful, difficult in children, requires trained staff and stringent laboratory conditions. Salivary sampling is inexpensive and less invasive( 31 , 167 ), but limited by inconsistent collection methods and food-related variability( 31 , 167 , 183 ). Urine sampling from children is challenging, with low participant compliance, sample refrigeration, and urinary metabolites interfere with cortisol measurements( 31 ). In contrast, hair sampling is non-invasive, independent of diurnal cycles, stored at room temperature, and provides chronologically distinct data for cortisol activity up to 6 months( 187 – 189 ).

Emerging research suggests that human hair follicles are neuroendocrine organs that index physiological stress responses( 190 , 191 ). Hair grows about 1 centimeter per month( 192 ) and incorporates the circulating free cortisol( 193 , 194 ), although the underlying mechanisms remain unknown( 195 , 196 ). Russell et al. proposed that free cortisol from the follicular vasculature passively diffuses into the hair shaft, or the hair follicle, sweat, and sebaceous glands may secrete and deposit cortisol into the hair shaft( 196 , 197 ). Like hemoglobin A 1c for blood glucose, hair cortisol concentrations (HCC) summate the cortisol release over time( 198 – 200 ). Earlier concerns about hair washing( 201 , 202 ) and HCC contamination from cortisol secreted by sebaceous or sweat glands have been refuted( 203 , 204 ). HCC show high test-retest reliability, were validated against serum, salivary, and urine cortisol, and are widely accepted as measures of chronic stress in adults( 200 , 205 ) and children( 193 , 199 , 206 ).

Effects of sex, age, and race:

Previous studies reported higher HCC in boys than in girls( 201 , 207 ). However, current data show no sex differences among preschool children( 28 , 193 ), higher HCC in pre-pubertal boys than girls, and no differences after puberty( 208 ). Variations of HCC with age are unclear, with most studies showing age-related decreases in preschool years( 28 , 209 , 210 ). Racialized experiences and structural racial discrimination may contribute to the higher HCC in African-American children compared to children from other races( 28 , 211 ).

Effects of prenatal and postnatal environments:

Higher HCC in 1-year-old infants were associated with maternal parenting stress, depression, and psychological distress( 211 ). Prenatal traumatic events were significantly associated with their child’s HCC at age 3 and 4 years, even after adjustments for known mediators like postpartum depression, parenting stress, psychological distress, child abuse potential; as well as preterm birth or body mass index (BMI)( 212 ).

Other studies found higher HCC in newborns following neonatal intensive care( 213 ), children with early trauma( 214 , 215 ), and children with high fearfulness ratings upon school entry( 206 ). In 6-7 year-olds, low HCC values suggestive of HPA-axis dysregulation were associated with exposures to frequent neonatal pain( 216 ), or harsh parenting( 217 ). Although perinatal adversities may alter long-term HPA-axis regulation into the school-age period, the most prominent postnatal influences on HPA activity result from poverty and early deprivation( 210 , 218 , 219 ).

Effects of socioeconomic adversity:

Children raised in poverty are often exposed to chronic stress, either directly (from food, housing, energy insecurity( 220 ), bullying( 221 , 222 ), or neighborhood violence( 126 )) or indirectly via parental stress( 223 ). Higher HCC were associated with lower parental education( 224 ), lower family income, more household members, single-parent households( 201 ), and deprived neighborhoods( 219 ). Similar associations between ELA and chronic stress( 225 – 228 ) may result from insensitive or rigid parenting( 217 ), parenting stress( 211 , 212 ), neighborhood effects( 126 , 219 ), and other poverty-related factors( 229 – 231 ). To understand the importance of these differences, we explore the implications of HCC as a chronic stress marker and subsequent health outcomes.

Hair Cortisol Concentrations: Implications for Health

Epidemiologic studies have established links between chronic stress, HPA-axis dysregulation, and subsequent physical and mental health outcomes( 27 , 232 ), but only a few of these studies have included HCC as a biomarker for chronic stress ( 189 , 193 ).

Higher HCC in preschool children were associated with impaired social-emotional development and increased risks for developmental delay( 28 , 211 ). In 6-8 year-old children, increased HCC were associated with higher BMI in girls and somatic complaints in boys( 207 ). In older children, increased HCC were associated with higher BMI( 208 ), other measures of obesity( 233 – 236 ), and vulnerability to common childhood illnesses( 237 ), even after controlling for factors such as race, age, gestational age, and birth weight. HCC were reduced in children with asthma( 238 ), possibly from HPA axis suppression due to inhaled corticosteroids( 239 – 241 ). Higher HCC also occurred in children with epilepsy( 242 ) and girls with anorexia nervosa( 243 ), but no differences were found in children with anxiety( 244 ) or depression( 215 , 244 ) as compared to controls.

In adults, HCC was increased in major depression, decreased in general anxiety disorder, whereas HCC changes in PTSD depended on the type of traumatic experience and elapsed time since trauma( 245 , 246 ). Increased HCC was used as a biomarker for stratifying cardiovascular risk and linked to obesity, hypertension, diabetes, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease( 245 , 247 ). In the survivors of physical and sexual abuse, higher HCC during pregnancy were associated with preterm labor( 248 – 250 ).