- United Kingdom

Coming To Terms With Being Asian American

Why it took me 25 years to come to terms with being asian american.

It was the first time that someone had encapsulated my entire personhood into one word: “Asian.”

Culture has a way of connecting us from the things we have in common to our differences. For #AsianPacificAmericanHeritageMonth we created a space for our voices to be heard and to defy (or embrace) the stereotypes that are placed on Asian Americans. We asked a few Asian Pacific American R29 staffers what their favorite thing about their culture is and discovered that the strings that attach us so closely with our culture are also associated with the memories we make with our families. The act of gathering and creating food brings us together (and something we still defer back to when we're feeling a bit homesick). Comment below with what about your culture brings you ✨joy✨. #APAHM #AcknowledgeIsPower #AsianPacificAmericanHeritageMonth A post shared by Refinery29 (@refinery29) on May 19, 2017 at 10:03am PDT

More from Mind

R29 original series.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/69240126/Copy_of_I_AWP_Folder_8_001_OK.0.jpg)

Filed under:

What does it mean to be Asian American?

The label encompasses an entire continent of different cultural roots. Does it speak to a shared experience?

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: What does it mean to be Asian American?

The label “Asian American” is almost comically flattening.

It consists of people from more than 50 ethnic groups, all with different cultures, languages, religions, and their own sets of historic and contemporary international conflicts. It includes newly arrived migrants and Asians who have been on American soil for multiple generations. Depending on visa types, immigration status, and class, there are vast differences even among those from the same country. In fact, the income gaps between some Asian American groups are among the largest of any ethnic category in the nation. Yet these differences are rarely explored and discussed.

With the recent rise in anti-Asian attacks, however, Asian Americans have found themselves in a rare moment in the national spotlight. For many, it has led to a renewed sense of solidarity as well as confusion about what the Asian American label means or if there really is a unifying experience attached to it.

It also inspired Vox to post a survey asking Asian Americans to write in and tell us how they’re feeling right now. The rise in violence — especially the shootings at three spas in Atlanta that left eight people dead, including six women of Asian descent — haunted the responses. One major theme emerged: Why did it take such an extreme act of violence to get America to care about its Asian communities?

“It frustrates me that the anti-Asian sentiments popularized by Trump had to be escalated to media-worthy violence and mass shootings in order to be elevated to mainstream discourse,” one person wrote from California.

“We’re trending today, but I bet we’ll be forgotten by next week or month,” wrote another from Michigan.

Other persistent issues emerged from our survey, too. Many responded that they didn’t quite know how to talk about cultural identity or racism with their parents or their children. The experience of growing up in non-diverse areas versus immigrant- or minority-dense enclaves — and how different it felt when moving from one area to another — also kept coming up. People with roots in South and Southeast Asian cultures wondered how they fit into an ethnic category so commonly associated with East Asians. Many questioned what the label Asian American really means and what purpose it serves in the larger American conversation around race.

In a series of stories publishing throughout this month, we will explore some of these questions and shared experiences, in a time when many Asian Americans are experiencing a sense of alienation not only from the nation at large, but also from the label “Asian American” itself.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22489117/HANIFAFINAL.jpeg)

The pitfalls — and promise — of the term “Asian American”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22508965/Vox_Asian_American_identity.jpeg)

The many Asian Americas

by Karen Turner

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22527840/lizziechen_crop.jpg)

In many Asian American families, racism is rarely discussed

by Rachel Ramirez

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22538174/Vox___Lane_Kim___Sanjena_Sathian___AK___Final.png)

Seeing myself — and Asian American defiance — in Gilmore Girls’ Lane Kim

by Sanjena Sathian

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22657577/Screen_Shot_2021_06_14_at_10.17.21_AM.png)

The Asian American wealth gap, explained in a comic

by Lok Siu and Jamie Noguchi

Will you support Vox today?

We believe that everyone deserves to understand the world that they live in. That kind of knowledge helps create better citizens, neighbors, friends, parents, and stewards of this planet. Producing deeply researched, explanatory journalism takes resources. You can support this mission by making a financial gift to Vox today. Will you join us?

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

Drake vs. everyone, explained

How the met gala became the fashion oscars, how lip gloss became the answer to gen z’s problems, sign up for the newsletter today, explained, thanks for signing up.

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

All products are independently selected by our editors. If you buy something, we may earn an affiliate commission.

The Difficulty of Being a Perfect Asian American

College admissions makes people do strange things. This was one of the takeaways of the Varsity Blues scandal , in 2019, which uncovered an admissions consultant and a network of coaches and administrators who helped wealthy and famous families essentially bribe their way into selective colleges. The scandal seemed to be the twisted, if logical, end point of all the credential-stacking and résumé-padding that has become part of the process. Yet there was something reassuring about the scandal, too: the conclusion that the admissions system is rigid enough that people with means, even Hollywood A-listers, would feel the desperation to game it. They may have believed that their children were entitled to a place at a prestigious school. But they couldn’t breeze right in. By some measures, it is twice as hard to get into élite colleges and universities than it was twenty years ago. Their desperation was warranted.

These anxieties about status are acutely felt among a cohort for whom going to college can seem a foregone conclusion. Asian Americans are often held up as a “model minority,” a group whose presence on campuses like Harvard or M.I.T., where forty per cent of incoming first-years self-identify as Asian American, far outpaces their percentage of the U.S. population. The figure of the model minority emerged in the fifties, a reflection of Cold War-era policies that were designed to attract highly educated immigrants from Asia. Over time, this stereotype ossified. American meritocracy held up the immigrant as proof that its rules were fair, and many high achievers were flattered to play along. Even though many of the gains for Asian Americans could be explained through policy—and even as studies showed how entire swaths of the community were left behind in poverty—the experience of being Asian in America has been rigidly defined by a framework of success and failure. As the scholar erin Khuê Ninh argues in “ Passing for Perfect: College Impostors and Other Model Minorities ,” it’s a framework that has been internalized, even by those who resist it.

Ninh’s fascinating book tells the stories of scammers, grifters, and impostors—Asian Americans following the high-pressure, expectation-heavy paths that can lead down darker alleys of faux accomplishment. There is Azia Kim, who masqueraded as a Stanford undergrad for months, even persuading two students to allow her to share a dorm room. Elizabeth Okazaki did something similar there, posing as a graduate student, attending class, and sleeping at a campus lab. Unlike the students caught up in the Varsity Blues scandal, these young people gave exhausting performances that weren’t going to result in a diploma or job. And, in the case of Jennifer Pan, who spent years tricking her parents into believing that she was attending the University of Toronto, the subterfuge resulted in tragedy. In 2010, she hired hitmen to murder them.

What compelled these impostors? To what extent were their actions driven by a need to keep up an illusion of excellence? Ninh, who teaches at the University of California, Santa Barbara, explores these stories not to rationalize them but to point out how they suggest a mood, a limited set of emotional possibilities for Asian Americans. “What if what seem to be outlandish and outlier behaviors are instead depressingly Asian American?” Ninh writes. Being a model minority, she argues, doesn’t require one to believe in the myth. Ninh asserts that a relationship to high achievement is “coded into one’s programming” as an Asian American, and that “its litmus test is whether an Asian American feels pride or shame by those standards.” Whether you are Amy Chua, extolling the virtues of being a “ tiger parent ,” or someone making fun of Chua, you are perpetuating the success-or-bust framework. A joking dismissal doesn’t debunk the stereotype so much as it signals the impossibility of living outside of it.

Ninh offers compelling evidence that adherents to the model-minority myth come “from an implausible multiplicity of life chances and immigration histories.” She cites the scholars Jennifer Lee and Min Zhou, who found that Southeast Asian refugees and wealthy, cosmopolitan transplants from China alike were “keenly aware” of stereotypes around Asian achievement. Lee and Zhou write that “for no other [racial] group is the success frame defined as getting straight A’s, gaining admission into an elite university, getting a graduate degree, and entering” into a coveted profession; in contrast, other groups balance grades with an investment in classroom behavior or how well they fit in with others. Ninh cites a 1998 study of perceptions of Asian Americans, based on interviews conducted with seven hundred college students of all races. A sense of Asian Americans as somehow exemplary permeated this student body; notably, the Asian Americans who took part in the interviews perceived themselves to be “more prepared, motivated, and more likely to have higher career success than whites,” even though their actual grades didn’t reflect any superiority.

Of all deceits, Ninh wonders if there is “something quaintly bookish, faintly charming about the academic grifter.” What drew Kim, Okazaki, Pan, and others to lie wasn’t a predictably ascendant path. Pretending to be students was a holding pattern, perhaps until a better answer presented itself. As Ninh points out, “The shortest route to mad bling does not run through four years of coursework. Money, then, would not appear to be the primary driver for our scammers— status is, arguably, and self-identity.”

Ninh feels enough sympathy for her subjects to probe their ambitions, their potential, the unnoticed mental-health struggles that led these people to take such immense risks. “Even when we have come to know our social formation as harmful to us,” she writes, “a life worth wanting may still be trapped in its terms.” The scammers and grifters might be viewed as people who allowed the expectations of Asian American identity to metastasize into something perilous. Ninh’s book is at its best when she seems to level with her subjects, to read them against their contexts: high-pressure parents, suburban milieus where value is doled out in how many colleges you get into, a national myth where you are both an undifferentiated mass and living proof of the American Dream. It’s a lot of work to pretend you are perfect—even more so when you know it is an illusion. Studies show that Asian Americans are the racial group who are least likely to seek help for mental illness, with much of it remaining undiagnosed. In 2018, Christine Yano and Neal Adolph Akatsuka published “ Straight A’s: Asian American College Students in Their Own Words ,” a collection of reflections from Harvard undergraduates. The achievements of these students aside—these were young people who, by traditional metrics, had done well—it was striking how each one navigated expectations of success and feelings of invisibility. Many lamented how the quest for excellence came to feel like a trap, ultimately leaving them unfulfilled. Even a drive to pursue unconventional paths, like art or writing, was cast as a rebellion against STEM stereotyping, not an expression of authentic desire.

“Passing for Perfect” is a tricky, unpredictable book, toggling between broad social analyses and sensational outliers, with close readings of reportage and court documents alongside Ninh’s bemused, occasionally exasperated commentary. Her shifting tones convey what it feels like to live inside a stereotype—to realize that even reasoned disavowals will never make it go away. She wonders whether it is possible to tunnel your way free from an imposed identity you know to be unhealthy and false. Stereotypes winnow down our imaginations or make us feel inadequate in the present; they also stifle a vision for the future, frustrating us, as our attempts to deny them only make them grow stronger.

The challenge, Ninh acknowledges, is to talk about success in terms that don’t merely reify the myth of the model minority. The starting point is to imagine other models of teaching, assessing, or assigning value. For the individual, resisting the myth requires more than merely becoming a “bad Asian”—for example, by rejecting the stereotype that Asians are good at math and violin by opting for art and football. Her book ends with a consideration of “Better Luck Tomorrow,” a film, from 2002, that drew on elements of the 1992 killing of Stuart Tay, a teen-ager from Orange County. Tay was killed by five students from a competitive, affluent high school. Tay and his eventual killers—four of whom were Asian American—were plotting a robbery, and his conspirators became convinced that he was going to betray them. Three of Tay’s killers were honor-roll students, leading the press to refer to the event as the “honor roll murder.”

In the movie version, the culprits’ murderous success burnishes the model-minority image; they excel at their studies as well as their criminal dalliances. As the movie ends, it is possible to believe they got away with it. But, in one of the most harrowing parts of “Passing for Perfect,” Ninh discusses the movie with two of Tay’s killers, Kirn Young Kim, who was paroled in 2012 and is now a prison-reform activist, and Robert Chan, who remains incarcerated. They lament that the characters in the film essentially win, rather than, in Ninh’s words, pull up short and offer “a cold, hard look at what all the work is for.” She notes that Chan has spent his time in prison unlearning the anger and “hypermasculinity” that defined his high-pressure teen years. And yet, in his mother’s home, a framed letter hangs on her bedroom wall. It is an invitation from the Harvard-Radcliffe Club of Southern California to interview for admission.

From the distance of middle age, the pressure to achieve looks like a race toward a false horizon. Of course, this isn’t how it’s experienced. Debbie Lum’s recent documentary, “Try Harder!,” offers an absorbing exploration of the pressures internalized by today’s high-school students. It chronicles a year at Lowell High School , a public magnet school in San Francisco that was, at the time Lum was filming, roughly fifty per cent Asian American. (Up until recently, students had to test into Lowell. As a result of a 2021 change to the school’s admissions, the demographic is expected to shift.)

Lowell is one of the top public schools in California, and therefore the nation—the type of place where even those with astronomical G.P.A.s and perfect SATs feel intense worry about their futures. The type of place where a kid who rallies his wallflower friends at the school dance compares himself to an enzyme.

Students talk about a “war on two fronts,” the competitive environment of the school itself and the pressure they feel from their families. For many, the only way to cope is to joke about how impossible it is to truly measure up. As “Try Harder!” begins, there’s a whimsical quirk to Lum’s storytelling. A charismatic Chinese American student named Ian cracks that he is “not even close to the best of the best.” He is self-effacing and funny. Everyone starts at Lowell dreaming of Stanford, he explains. By sophomore year, the Stanford hoodies are relegated to the closet, and expectations grow more realistic: the U.C.s. By junior year, he says, kids settle for Occidental, a “West Coast private college that’s not that hard to get into.”

Lum follows a few students through their days, which are dizzying. Lowell seems a challenging place to distinguish oneself. A physics teacher implores the students to give up their fetish for prestige, pointing out that “you are not too good for Santa Cruz, or Riverside, or even Merced,” which are often perceived to be among the U.C. system’s lesser schools. There’s no way to win. On one hand, they must excel in their local rat race. On the other, Lowell doesn’t send as many students to schools like Stanford or Harvard as you might think. The students—and at least one teacher—suspect that, for top colleges, Lowell seems too “stereotypically Asian,” a monolith of “A.P.-guzzling grade grubbers,” bereft of the well-rounded superstars who make admissions officers happy.

At times, “Try Harder!” hints at these larger stories, from the alleged prejudices that top-tier colleges harbor against the perceived machinelike excellence of Asian applicants to the racial politics of San Francisco to the uneven distribution of resources that produce élite public schools like Lowell. In February, local voters recalled three members of the city’s Board of Education, in part to protest their role in a 2021 decision to diversify Lowell by replacing its merit-based admissions system with a lottery. The recall campaign was driven by Asian American voters—many of whom presumably have little interest in following Ninh’s call to rethink paradigms of success. As one parent told the Times , education has “been ingrained in Chinese culture for thousands and thousands of years.”

Lum focusses on these pressures as they trickle down to the students, which makes for a compelling set of dramas. One of the film’s stars is an African American student named Rachael, whose sweet, aggressive modesty leads her to underestimate her own capabilities. There’s a Taiwanese American kid named Alvan who seems happiest in his dance class—only his parents would never understand. His highest and lowest moments alike are commemorated with a dab . These are all students who, in Ninh’s words, “pass for perfect.” The occasional shots of students staring off into the distance convey more than they are capable of articulating as teen-agers.

As the year wears on, they begin to feel the effects of the grind. There’s less energy for all-night study sessions; the tense, feigned smile of the after-school job is harder to maintain. Students begin wondering why they worked so hard in the first place. I want to say that I felt a familiar sense of fear as the admissions letters began rolling in, but, even though I attended a competitive Bay Area high school full of Asian kids, it was nothing like this. There was less to do, yet more possible futures to imagine. “Try Harder!” slowly shifts genres from comedy to horror. You almost stop caring whether anyone will get into their dream school, because you already recognize that we should be encouraging students to dream of something other than school. Yet you desperately want them to get in, for it is the only horizon they have ever known.

New Yorker Favorites

The day the dinosaurs died .

What if you started itching— and couldn’t stop ?

How a notorious gangster was exposed by his own sister .

Woodstock was overrated .

Diana Nyad’s hundred-and-eleven-mile swim .

Photo Booth: Deana Lawson’s hyper-staged portraits of Black love .

Fiction by Roald Dahl: “The Landlady”

Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Inkoo Kang

By Erik Baker

By Louis Menand

By Justin Chang

- Essay & Memoir

- Conversations

- Craft and Career

- Field Notes (Science and Environment)

- Generations

- In Sickness and In Health

- The Sounding Board

- Translation

- Editors & Staff

- Board of Advisors

- Index Of Stories

- Opportunities

- Get an Author Discovered

- Pushcart Prize Nominations 2023

On Being (Asian)

- On Being (Asian) - April 5, 2022

LEAVE A REPLY

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

mailing address: Pangyrus Inc 2592 Massachusetts Ave Cambridge, MA 02140

- Submissions Period: January 15 – April 15, 2024

- Subscriptions

- Support Pangyrus

Social Networks

Get the latest news and stories from Tufts delivered right to your inbox.

Most popular.

- Activism & Social Justice

- Animal Health & Medicine

- Arts & Humanities

- Business & Economics

- Campus Life

- Climate & Sustainability

- Food & Nutrition

- Global Affairs

- Points of View

- Politics & Voting

- Science & Technology

- Alzheimer’s Disease

- Artificial Intelligence

- Biomedical Science

- Cellular Agriculture

- Cognitive Science

- Computer Science

- Cybersecurity

- Entrepreneurship

- Farming & Agriculture

- Film & Media

- Health Care

- Heart Disease

- Humanitarian Aid

- Immigration

- Infectious Disease

- Life Science

- Lyme Disease

- Mental Health

- Neuroscience

- Oral Health

- Performing Arts

- Public Health

- University News

- Urban Planning

- Visual Arts

- Youth Voting

- Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine

- Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy

- The Fletcher School

- Graduate School of Arts and Sciences

- Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences

- Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging

- Jonathan M. Tisch College of Civic Life

- School of Arts and Sciences

- School of Dental Medicine

- School of Engineering

- School of Medicine

- School of the Museum of Fine Arts

- University College

- Australia & Oceania

- Canada, Mexico, & Caribbean

- Central & South America

- Middle East

A Spanish galleon ship much like the ones that brought the first Asians to the Americas in the 1500s. Cornelis Verbeeck, detail of “A Naval Encounter between Dutch and Spanish Warships,” circa 1618-1620. Photo: National Gallery of Art

A History of the First Asians in the Americas Became Personal

Historian Diego Javier Luis plumbed the far corners of archives to unearth the stories of Filipinos and others who came to colonial Mexico starting in the 1500s

When most people in the U.S. think about Asian immigrants coming to the Americas, they often picture immigrants from China coming in the 1800s. The story, though, is much more complicated—and interesting.

As Diego Javier Luis, assistant professor of history, describes in his new book The First Asians in the Americas , the full story starts with Spanish galleon ships traveling back and forth from Acapulco in Mexico to Manila in the Philippines in the mid-1500s, trading silver from the Americas for silks and other trade goods from Asia.

But it wasn’t only goods. People from Asia, from as far afield as Gujarat in India to the Philippines, including some from China and Japan, came to colonial Mexico, many of them enslaved, some free. They were the first Asians in the Americas, and slowly fanned out across the continents.

He delved deep into archives held in Spain, Mexico, the Philippines, and the U.S. to find the stories of those individuals and groups. He had learned Mandarin while working in Xian, China, for a few years after college, and learned Spanish as an adult—languages that came in handy for his research.

For Luis, who grew up in Nashville, the story was in some ways personal, too. His paternal grandfather was Chinese, and he has Afro-Cuban as well as Ashkenazi Jewish roots.

Tufts Now recently talked to Luis to learn more about his personal connection to his research, and how as a historian he found sources on people who are usually hidden in the archives.

How did your family history play into your interest in the experience of the first Asians in the Americas?

On my dad’s side of the family, we come originally from China and from West Africa, and from the Canary Islands and Spain. There was a meeting of these three family strands in Cuba.

“It’s a Latin American story—we can’t understand what diasporic Asian American or Latino experiences in the U.S. are without thinking about Latin America,” says Diego Javier Luis. “It’s all interconnected.” Photo: Jodi Hilton

My Chinese grandfather came to Cuba directly during the early 20th century. We don’t know exactly when, perhaps in the 1920s or 1930s. We also know that his grandfather had already been coming and going to and from Cuba. There’s a long history of the Chinese in Cuba during the period of indenture, starting when the transatlantic slave trade was ending in the 1800s.

There was a massive convergence of people coming to the Caribbean and South America to work. In Cuba, they’d work alongside enslaved and recently liberated Afro-Caribbean people. From 1847 to 1874, 120,000 Chinese were brought to Cuba as indentured laborers, and we think the grandfather of my grandfather was likely one of them.

Where did your paternal grandmother come from?

She is the daughter of a man who fought during the wars of independence against Spain—a socially mobile Black man named Ventura Santos Santos, who moved to Havana from a small town called Caibarién. My grandparents met in Havana, and then my Chinese grandfather convinced my grandmother to come with him to New York City, to the Lower East Side near Canal Street in Chinatown. He had a laundromat there, and that’s where they had my dad and his brother.

It is very much a global story, and it is complicated because growing up in Nashville, I didn’t know what any of that meant. I only knew that I looked different from my other classmates, and they didn’t know how to categorize me, either. I was mostly just “Mexican” to the people in that environment.

I later lived in China for a while, traveled to Cuba, and it took a while to really understand what it meant to be someone who has connections to those places, even if that connection is more ancestral than something that’s lived in my own life.

And then there’s my mom’s side of the family, which is from Vermont and has roots in the Ashkenazi Jewish diaspora by way of Lithuania. That’s a whole other thing to come to terms with.

How did you decide to focus your doctoral research, and this new book, on the first Asians in the Americas?

Part of it was coming from this personal journey of not really knowing what it meant to have a family history that connected these places—to make some coherence out of something that’s very fragmented. I think a lot of mixed people discover that there is no way really to put everything into perfect harmony. You have to accept the fragmentation of it.

“There was a sense of not aloneness. You see that you’re not the first one to be dealing with some of those issues of identity.” Diego Javier Luis Share on Twitter

Another reason was to broaden how we think about Asians coming to North and South America, not just the U.S. I think for a very long time, the canon of Asian American history and studies was geographically focused mostly on the West Coast of the U.S. It’s very much an East Asian dominated story.

What’s remarkable about this early period is that the people who are showing up in colonial Mexico, free and enslaved, are from all over Asia, mostly people from the Philippines and the Bay of Bengal area and elsewhere in South Asia. There are also smaller concentrations from Japan, Korea, China, and other places in Southeast Asia.

It is an extraordinarily diverse movement, and it gets us thinking about the geography of diaspora in different ways—they’re going to Mexico and dispersing outwards. Many end up in South America, some end up going up and down what’s now the U.S. West Coast, but it’s really not a U.S. story at all.

It’s a Latin American story—we can’t understand what diasporic Asian American or Latino experiences in the U.S. are without thinking about Latin America. It’s all interconnected. I hope the book promotes this kind of hemispheric thinking and makes people think more broadly about the diversity of diaspora.

Did the research and writing of the book change or inform how you feel about your identity?

One of the major takeaways for me was that I’m not the only one who has felt out of place, out of time. I grew up in Nashville but was connected to these other sites and was being misread from an ethnic perspective and had to go through some kind of self-fashioning to be legible to other people.

I was really interested to see how these folks, who were the first Asians in the 16th and 17th centuries to be living in a very different kind of society in the Americas, were dealing with similar kinds of questions. There was a sense of not aloneness. You see that you’re not the first one to be dealing with some of those issues of identity.

“What’s remarkable about this early period is that the people who are showing up in colonial Mexico, free and enslaved, are from all over Asia, mostly people from the Philippines and the Bay of Bengal area and elsewhere in South Asia.” Diego Javier Luis Share on Twitter

It is complicated, because I don’t share any family history with the people that I study, but at the same time, I did feel a kind of personal connection to their stories. That helped me form this kind of connection that can also inform how I approach those histories in my scholarly work.

History is what’s written down, and there is very little in the records about marginalized people—certainly in the 1500s and 1600s. How did you find sources for Asians coming in these very early days to Mexico for your book?

It takes rigorous archival work. If you read any of the canonical texts about the colonial period in Latin America, there’s going to be very, very little that speaks to this history. But we see people showing up in the legal record—they were getting married, baptized, applying for licenses. They show up in accounting records, criminal cases, inquisition cases.

Let’s say for Acapulco, an important port town in this history, where many Asian people are entering the Americas, it meant flipping through every single page of the accounting records for this port for a 40- or 50-year span. And at least 95% of those records have nothing to do with the history of these people.

I did a manual word scan of the documents to pick up where these people show up. Some of it is learning the words that were used to refer to the people that I’m studying—that’s a whole process, too, because those categories are so variable and contingent.

It’s really searching for a needle in the haystack. But when you find these little nuggets of gold, it’s a celebration.

In the book, you include a 15-page appendix that lists all the crew members of a Spanish galleon that made the journey from Manila to Acapulco in 1751—and hundreds were Filipinos and other people from Asia. It’s an amazing amount of down-in-the-details work to make your point about Asians coming to Mexico so early.

What makes those records difficult is that they were part of an 800- to 1,000-page document, and this is a small sliver of that. Other scholars have looked at some of these documents, but I haven’t seen that exact roster appear anywhere else.

A lot of the work that’s been done on the Spanish galleon trade between Mexico and Manila is of an economic nature, using shipping records to show how globally connected the world’s economies were during the early modern period—China to Mexico, to Spain, to the Philippines. It is a remarkable story, but one of the repercussions has been losing sight of the people who were on those boats. My study is framed as trying to find the Asian people who were on those ships.

Recovering Family History for Millions of African Americans

The Long History of Xenophobia in America

Charting a Course from Asia to Latin America

Advertisement

The Anxiety of Being Asian American: Hate Crimes and Negative Biases During the COVID-19 Pandemic

- Published: 10 June 2020

- Volume 45 , pages 636–646, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Hannah Tessler 1 ,

- Meera Choi 1 &

- Grace Kao 1

79k Accesses

243 Citations

105 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

In this essay, we review how the COVID-19 (coronavirus) pandemic that began in the United States in early 2020 has elevated the risks of Asian Americans to hate crimes and Asian American businesses to vandalism. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the incidents of negative bias and microaggressions against Asian Americans have also increased. COVID-19 is directly linked to China, not just in terms of the origins of the disease, but also in the coverage of it. Because Asian Americans have historically been viewed as perpetually foreign no matter how long they have lived in the United States, we posit that it has been relatively easy for people to treat Chinese or Asian Americans as the physical embodiment of foreignness and disease. We examine the historical antecedents that link Asian Americans to infectious diseases. Finally, we contemplate the possibility that these experiences will lead to a reinvigoration of a panethnic Asian American identity and social movement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Anti-Asian Hate Crime During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Exploring the Reproduction of Inequality

LGBTQ Stigma

Intergenerational communication about historical trauma in asian american families.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

COVID-19 (or the coronavirus) is a global pandemic that has affected the everyday lives of hundreds of millions of people. At the time we write this, there have been over four million cases across over 200 countries worldwide (Pettersson, Manley, & Hern, 2020 ) . Moreover, pervasive stay-at-home orders and calls for social distancing, as well as the disruptions to every facet of our lives make it difficult to overstate the importance of COVID-19. As the beginning of the outbreak has been traced to China (and Wuhan in particular), both in the United States and elsewhere, people who are Chinese or seen as East Asian have become associated with this contagious disease. Early reports in the United States were often accompanied by stock photos of Asians in masks (Burton, 2020 ; Walker, 2020 ). Many of the first reports labeled the disease as the “Wuhan Virus,” or “Chinese Virus,” and the Trump administration has also used these terms (Levenson, 2020 ; Maitra, 2020 ; Marquardt & Hansler, 2020 ; Rogers, Jakes, & Swanson, 2020 ; Schwartz, 2020 ). News media coverage in the United States focused on the hygiene of the seafood market in Wuhan and wild animal consumption as a possible cause of coronavirus (Gomera, 2020 ; Mackenzie & Smith, 2020 ). Memes and jokes about bats and China flooded social media, including posts by our peers online. These reports provide the American public a straightforward narrative that focuses on China as the origin of COVID-19.

In this paper, we review current patterns of hate crimes, microaggressions, and other negative responses against Asian individuals and businesses during the COVID-19 pandemic. These hate crimes and bias incidents occur in the landscape of American racism in which Asian Americans are seen as the embodiment of China and potential carriers of COVID-19, regardless of their ethnicity or generational status. We believe that Asian Americans not only are not “honorary whites,” but their very status as Americans is, at best, precarious, and at worst, in doubt during the COVID-19 crisis. We suggest that what we witness today is an extension of the history of Asians in the United States and that this experience may lead to the reemergence of a vibrant panethnic Asian American identity.

Hate Crimes Against Asian Americans During COVID-19

As of early May 2020, there have been over 1.8 million individuals who have tested positive for and over 105,000 deaths from COVID-19 in the United States alone and the numbers are growing rapidly every day (“Cases in the U.S.,” 2020 ). Although researchers have traced cases of the virus in the United States to travelers from Europe (Gonzalez-Reiche et al., 2020 ) and to travelers within the United States (Fauver et al., 2020 ), some members of the general public regard Asian Americans with suspicion and as carriers of the disease. On April 28th, 2020, NBC News reported that 30% of Americans have personally witnessed someone blaming Asians for the coronavirus (Ellerbeck, 2020 ).

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed the negative perceptions of Asian Americans that have long been prevalent in American society. Many individuals in the United States see the virus as foreign and condemn phenotypically Asian bodies as the spreaders of the virus (Ellerbeck, 2020 ). Consistent with Claire Jean Kim’s theory on racial triangulation (Kim, 1999 ) and the concept of Asians as perpetual foreigners (Ancheta, 2006 ; Saito, 1997 ; Tuan, 1998 ; E. D. Wu, 2015 ) , we posit that during COVID-19, the racial positionality of Asian Americans as foreign and Other persists, and that this pernicious designation may be a threat to the safety and mental health of Asian Americans. They are not only at risk of exposure to COVID-19, but they must contend with the additional risk of victimization, which may increase their anxiety. Historically, from the late 19th through the mid twentieth century, popular culture and news media portrayed Asians in America as the “Yellow Peril,” which symbolized the Western fear of uncivilized, nonwhite Asian invasion and domination (Okihiro, 2014 ; Saito, 1997 ) . It is possible that the perceived threat of the Yellow Peril has reemerged in the time of COVID-19.

The spread of the coronavirus and the increased severity of the pandemic has caused fear and panic for most Americans, as COVID-19 has brought about physical restrictions and financial hardships. So far, forty-two states have issued stay-at-home orders, which has resulted in 95% of the American population facing restrictions that impact their daily lives (Woodward, 2020 ). Novel efforts to end the pandemic across the states have led businesses to shut down. As a result, more than 30 million people in the United States have filed for unemployment since the onset of the coronavirus crisis (Gura, 2020 ). Because this virus has been identified as foreign, for some individuals, their feelings have been expressed as xenophobia, prejudice, and violence against Asian Americans. These negative perceptions and actions have gained traction due to the unprecedented impact COVID-19 has on people’s lives, and institutions such as UC Berkeley have even normalized these reactions (Chiu, 2020 ). However, racism and xenophobia are not a “natural” reaction to the threat of the virus; rather, we speculate that the historical legacies of whiteness and citizenship have produced these reactions, where many individuals may interpret Asian Americans as foreign and presenting a higher risk of transmission of the disease.

Already, the FBI has issued a warning that due to COVID-19, there may be increased hate crimes against Asian Americans, because “a portion of the US public will associate COVID-19 with China and Asian American populations” (Margolin, 2020 ). News reports, police departments, and community organizations have been documenting these incidents. Evidence suggests that the FBI’s warning was warranted. Based on reporting from Stop AAPI Hate , in the one-month period from March 19th to April 23rd, there were nearly 1500 alleged instances of anti-Asian bias (Jeung & Nham, 2020 ). The reported incidents have been concentrated in New York and California, with 42% of the reports hailing from California and 17% of reports from New York, but Asian Americans in 45 states across the nation have reported incidents (Jeung & Nham, 2020 ).

Reports of Hate Crimes and Bias Incidents

There have been a large number of physical assaults against Asian Americans and ethnically Asian individuals in the United States directly related to COVID-19. While the majority of Americans are sheltering-in-place and staying at home, 80% of the self-reported anti-Asian incidents have taken place outside people’s private residences, in grocery stores, local businesses, and public places (Jeung & Nham, 2020 ). We suggest that these hate crimes and other incidents of bias have historical roots that have placed Asians outside the boundaries of whiteness and American citizenship. In addition, we believe that the current COVID-19 crisis draws attention to ongoing racial issues and provides a lens through which to challenge the notion of America as a post-racial society (Bonilla-Silva, 2006 ).

One of the incidents under investigation as a hate crime includes the attempted murder of a Burmese-American family at a Sam’s Club in Midland, Texas (Yam, 2020a ). The suspect said that he stabbed the father, a four-year-old child, and a two-year-old child because he “thought the family was Chinese, and infecting people with coronavirus” (Yam, 2020a ). Police are investigating numerous other physical incidents including attacks with acid (Moore & Cassady, 2020 ), an umbrella (Madani, 2020 ), and a log (Kang, 2020 ). There have been a number of physical altercations at bus stops (Bensimon, 2020 ; Madani, 2020 ), subway stations (Parnell, 2020 ), convenience stores (Oliveira, 2020 ), and on the street (Jeung & Nham, 2020 ; Sheldon, 2020 ). Asian Americans are also reporting physical threats being made against them (Driscoll, 2020 ; Parascandola, 2020 ). Based on Stop AAPI Hate statistics, 127 Asian Americans filed reports of physical assaults in four weeks (Jeung & Nham, 2020 ), and it is likely that other Asians have not reported their experiences out of fear or concern about the legal process.

In addition to the physical attacks and threats against Asian Americans, individuals have also filed reports of vandalism and property damage targeted at Asian businesses. One Korean restaurant in New York City had the graffiti “stop eating dogs” written on its window (Adams, 2020 ). Perpetrators have also made explicit references to COVID-19 in their vandalism, where phrases such as “take the corona back you ch*nk” (Goodell & Mann, 2020 ), and “watch out for corona” (Wang, 2020 ) have been documented on Asian-owned restaurants. Some of these incidents were not reported to the police and therefore will not be investigated as hate crimes, as business owners reasoned that it would be difficult to track the vandals (Adams, 2020 ; Buscher, 2020 ). These incidents of vandalism demonstrate the association some people make between Asian American businesses and COVID-19.

Beyond the narrow definition of the incidents that can be classified as punishable hate crimes, Asian Americans have also documented a large number of alleged bias and hate incidents. Stop AAPI Hate reports indicate that 70% of coronavirus discrimination against Asian Americans has involved verbal harassment, with over 1000 incidents of verbal harassment reported in just four weeks (Jeung & Nham, 2020 ). In addition, there have been over 90 reports of Asian Americans being coughed or spat on. One prevalent theme in the verbal incidents is the linking of Asian bodies to COVID-19, where the aggressors are purportedly calling Asians “coronavirus,” “Chinese virus,” or “diseased,” and telling them that they should “be quarantined,” or “go back to China” (ADL 2020 ). In all of these incidents, the perpetrators consistently use anti-Asian racial slurs (Buscher, 2020 ; Goodell & Mann, 2020 ; Sheldon, 2020 ). This hateful language that targets all Asians (and not just Chinese Americans) demonstrates the racialization of Asian Americans.

The threat of a global pandemic to people’s everyday lives is something that most Americans have not experienced before. However, the act of interpreting the current national crisis as an external threat and ascribing this danger to Chinese bodies and more broadly Asian bodies should not surprise scholars of Asian Americans. In fact, this deeply-rooted cognitive association of Asian Americans to Asia and to disease has a long history. Hence, we examine the phenomenon of xenophobia against Asian Americans in the context of historical racial dynamics in the United States.

The Color Line and the Positionality of Asian Americans

Race has been posited as a socio-historical concept, and while many race scholars in the United States have focused on the black/white binary, others have documented how Asian Americans have also been racialized over time (Omi & Winant, 2014 ). These scholars have examined how the racialization of Asian Americans has developed in relation to African Americans and white Americans (Bonilla-Silva, 2004 ; Kim, 1999 ). One of the dominant stereotypes of Asian Americans is that they are perpetual foreigners , where individuals directly link phenotypical Asian ethnic appearance with foreignness, regardless of Asian immigrant or generational status (Ancheta, 2006 ; Tuan, 1998 ; F. H. Wu, 2002 ). This stereotype is longstanding in American history and has forcefully re-emerged during the COVID-19 crisis. The perception of an Asian-looking person as simultaneously Chinese, Asian, and foreign underscores how this racial categorization affects all Asian Americans. Thus, we suggest that the concept of Asian American panethnicity (Okamoto & Mora, 2014 ) may be particularly applicable during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The legacy of white supremacy equates white bodies with purity and innocence, while nonwhite bodies are designated as unclean, uncivilized, and dangerous. White supremacy and its tactic of othering Asian bodies has been a consistent recurrence over earlier pandemics. Dating back to the nineteenth century, the bubonic plague was framed as a “racial disease” which only Asian bodies could be infected by whereas white bodies were seen as immune (Randall, 2019 ). In 1899, Honolulu officials quarantined and burned Chinatown as a precaution against the bubonic plague (Mohr, 2004 ). In 1900, San Francisco authorities quarantined Chinatown residents, and regulated food and people in and out of Chinatown, believing that the unclean food and Asian people were the cause of the epidemic (Shah, 2001 ; Trauner, 1978 ). The history of the Yellow Peril has continued throughout the 20th and 21st centuries in the embodied perceptions of Asian immigrants as the spreaders of disease (Molina, 2006 ).

More recently, during the 2003 SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) epidemic, the discourse in the United States focused on Chinatown as the epicenter of the disease (Eichelberger, 2007 ). Studies suggest that 14 % of Americans reported avoiding Asian businesses and Asian Americans experienced increased threat and anxiety during SARS (Blendon, Benson, DesRoches, Raleigh, & Taylor-Clark, 2004 ). We suspect the negative impact of COVID-19 on Asian Americans has been far greater than the impact of SARS. In New York City’s Chinatown, restaurants suffered immediately after the first reports of COVID-19, as some restaurants and businesses experienced up to an 85% drop in profits for the two months prior to March 16th, 2020 – far before any stay-at-home orders were given (Roberts, 2020 ). When moral panic arises, foreign bodies, typically the undesirable and “un-American” yellow bodies, may be seen as a threat that can harm pure white bodies.

The cycle of elevated risk, followed by fearing and blaming what is foreign is not just limited to disease outbreaks, but also occurs during economic downturns. In 1982, Vincent Chin was beaten to death by two men who blamed him for the influx of Japanese cars into the United States auto market. Vincent Chin was attacked with racial slurs and specifically targeted because of his race. Although Chin was Chinese American, in the minds of these two men, he represented the downturn of the auto industry in Detroit and the increased imports of Japanese automobiles (Choy & Tajima-Pena, 1987 ).

Similarly, after the 9/11 attacks in the United States, retaliatory aggressions were not limited to attacks against Arabs or Muslims (Perry, 2003 ). Violence and hatred against the perceived enemy resulted in incidents targeting Sikhs, second and third generation Indian Americans, and even Lebanese and Greeks (Perry, 2003 ). More recently, the hate crime murder of Srinivas Kuchibhotla, an Indian immigrant falsely assumed to be an Iranian terrorist and told “get out of my country” before being shot to death, illustrates the association between racialized perceptions of threat and incidents of violence (Fuchs 2018 ). With the COVID-19 pandemic, violent attacks and racial discrimination against Asian Americans have emerged as non-Asian Americans look for someone or something Asian to blame for their anger and fear about illness, economic insecurity, and stay-at-home orders.

Fear and the Mental Health of Asian Americans

The current perceptions of China and more broadly East Asia as both economic and public health threats have made Chinese and East Asians in America fearful for their own safety. Some Asian Americans have made efforts to hide their Asian identity or assert their status as American in an attempt to prevent hate crime attacks (Buscher, 2020 ; Tang, 2020 ). While this tactic may be effective on the individual level, it does not modify the positionality of Asian bodies during COVID-19. The attempt to distinguish Asian Americans from Asians who are foreign nationals misses the fact that in the United States, being Asians and being foreign are inextricably bound together.

After World War II, news media and local organizations encouraged Chinese Americans to distinguish themselves from the Japanese, and similarly encouraged Japanese Americans to show their Americanness and patriotism to gain acceptance by the white majority (E. D. Wu, 2015 ). Muslim and Sikh Americans displayed American flags after 9/11 to show that they were not a threat to the United States, and more recently there has been a movement to celebrate Sikh Captain America (Ishisaka, 2018 ). Former presidential candidate Andrew Yang suggested that Asian Americans fight against racism by wearing red white and blue and prominently displaying their Americanness (Yang, 2020 ). In many of these situations, these strategies did not directly address the problems of racism and xenophobia – they simply shifted the blame towards another group.

Disease does not differentiate among people based on skin color or national origin, yet many Asian Americans have suffered from discrimination and hatred during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although the threat of the virus is real for all Americans, Asian Americans bear the additional burden of feeling unsafe and vulnerable to attack by others. The link between COVID-19 and hate crimes and bias incidents against Asian Americans is indicative of the widespread racial sentiments which continue to be prominent in American society. While some scholars have gone as far as to regard Asian Americans as “honorary whites” (Tuan, 1998 ), the current COVID-19 crisis has made markedly clear this is an illusion, at best. There are a number of reasons why the racial dynamics of anti-Asian crimes during COVID-19 should be examined more closely.

First, the majority of incidents and attacks have occurred in diverse metropolitan areas such as New York City, Boston, and Los Angeles. These are spaces that most Americans have traditionally regarded as more liberal and tolerant of difference than other parts of the United States. In New York City alone, from the start of the COVID-19 outbreak through April 2020, the NYPD’s hate crime task force has investigated fourteen cases where all the victims were Asian and targeted due to coronavirus discrimination (NYPD, 2020 ). The remarks of a Kansas governor that said his town was safe “because it had only a few Chinese residents” (Lefler & Heying 2020 ) offers one explanation for the high concentration of racial incidents in large cities with sizable Asian populations, but we think that this is not sufficient in explaining the data so far. Future research should track racial bias and hate crimes more systematically in order to further our understanding of how demography and urbanicity influence these incidents.

Second, these hate crimes have increased the anxiety of Asian Americans during already uncertain times, with many fearful for their physical safety when running everyday errands (Tavernise & Oppel Jr., 2020 ). Asian Americans are now self-conscious about “coughing while Asian” (Aratani, 2020 ), and concerned about being targeted for hate crimes (Liu, 2020 ; Wong, 2020 ). There is evidence to suggest that Asian Americans under-report crimes (Allport, 1993 ), and some recent immigrants may lack an understanding of the legal system and process of reporting crimes, particularly in the case of hate crimes. Therefore, scholars should take additional care to document and analyze these incidents and their effects on Asian American communities across the United States.

The possible upward trend of anti-Asian bias incidents and hate crimes is indicative of the growth of white nationalism and xenophobia. The image of a disease carrier with respect to COVID-19 is bound in Asian bodies and includes assumptions about race, ethnicity, and citizenship. As Vincent Chin, Srinivas Kuchibhotla, the Burmese-American family, and many others have shown us, the level of fungibility in terms of how Asian ethnicities are perceived can be deadly. It does not matter if the person is from China, of Chinese origin, or simply looks Asian – the perpetrators of this violence see all of these bodies as foreign and threatening. While there have been numerous instances of anti-Asian bias and crime, there have not been similarly patterned anti-European tourist incidents or an avoidance of Italian restaurants, suggesting that COVID-19 illuminates the particular racialization of disease that extends beyond this virus, and further back in American history.

Already there has been substantial news coverage of these anti-Asian crimes, which suggests that people are paying attention to this issue, and police departments are actively investigating many of these incidents. Activists and community organizations have started online campaigns such as #washthehate and #hateisavirus to combat anti-Asian racism during this time. The BBC has documented 120 distinct news articles covering alleged incidents of discrimination since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (Cheung, Feng, & Deng, 2020 ). In addition, the Chinese for Affirmative Action and Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council have created a platform where individuals can record incidents of racism and coronavirus discrimination. The reporting of hate crimes during COVID-19 is superior to the reports of these types of incidents during the SARS outbreak (Leung Coleman, 2020 ; Washer, 2004 ). Although the federal government response has been limited compared to the hate crime prevention initiatives after 9/11 and SARS, in May 2020, the Commission on Civil Rights agreed to take on the demands proposed by a group of Democratic Senators in a letter requesting a stronger response to the anti-Asian hate crimes and discrimination during COVID-19 (Campbell & Ellerbeck, 2020 ; Yam, 2020b ).

Similar to the murder of Vincent Chin, which served to ignite an Asian American activist movement, we hypothesize that the racial incidents against Asian Americans during the COVID-19 pandemic may encourage the political mobilization of a panethnic Asian American movement. At the same time, we believe that the incidents that are classified as “hate crimes” and “bias incidents” based on legal definitions do not fully capture the extent or pervasiveness of racist and xenophobic thoughts against Asian Americans. We encourage future scholars to more closely examine the culturally embedded racial logics that lead to these incidents, rather than focusing solely on the incidents themselves as the object of analysis. The hate crimes against Asians in the time of COVID-19 highlight the ways that Asian Americans continue to be viewed as foreign and suspect. This may be an additional burden on Asian Americans beyond the anxiety, economic instability, and the risk of illness all Americans have experienced during COVID-19.

Adams, E. (2020). Racist graffiti scrawled on Michelin-starred West Village Korean restaurant JeJu. Eater NY. https://ny.eater.com/2020/4/13/21218921/jeju-noodle-bar-racist-graffiti-harrasment-coronavirus-nyc . Accessed 26 Apr 2020.

ADL. (2020). Reports of anti-Asian assaults, harassment and hate crimes rise as coronavirus spreads. Anti-Defamation League . https://www.adl.org/blog/reports-of-anti-asian-assaults-harassment-and-hate-crimes-rise-as-coronavirus-spreads . Accessed 26 Apr 2020.

Allport, G. (1993). Racial violence against Asian Americans. Harvard Law Review, 106 (8), 1926–1943. https://doi.org/10.2307/1341790 .

Article Google Scholar

Ancheta, A. N. (2006). Race, rights, and the Asian American experience . New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Google Scholar

Aratani, L. (2020). “Coughing while Asian”: Living in fear as racism feeds off coronavirus panic. The Guardian . https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/24/coronavirus-us-asian-americans-racism . Accessed 27 Apr 2020.

Bensimon, O. (2020). Cops bust suspect accused of coronavirus-related hate crime on Asian Man. New York Post . https://nypost.com/2020/03/14/cops-bust-suspect-in-coronavirus-related-hate-crime-on-asian-man/ . Accessed 26 Apr 2020.

Blendon, R. J., Benson, J. M., DesRoches, C. M., Raleigh, E., & Taylor-Clark, K. (2004). Public’s response to severe acute respiratory syndrome in Toronto and the United States. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 38 (7), 925–931. https://doi.org/10.1086/382355 .

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2004). From bi-racial to tri-racial: Towards a new system of racial stratification in the USA. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 27 (6), 931–950. https://doi.org/10.1080/0141987042000268530 .

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2006). Racism without racists: Color-blind racism and the persistence of racial inequality in the United States . Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Burton, N. (2020). Why Asians in masks should not be the “face” of the coronavirus. Vox . https://www.vox.com/identities/2020/3/6/21166625/coronavirus-photos-racism . Accessed 6 May 2020.

Buscher, R. (2020). Reality is hitting me in the face: Asian Americans grapple with racism due to COVID-19. WHYY . https://whyy.org/articles/reality-is-hitting-me-in-the-face-asian-americans-grapple-with-racism-due-to-covid-19/ . Accessed 26 Apr 2020.

Campbell, A. F., & Ellerbeck, A. (2020). Federal agencies are doing little about the rise in anti-Asian hate. NBC News . https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/federal-agencies-are-doing-little-about-rise-anti-asian-hate-n1184766 . Accessed 29 May 2020.

Cases in the U.S. (2020). https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/cases-in-us.html . Accessed 2 Jun 2020.

Cheung, H., Feng, Z., & Deng, B. (2020). Coronavirus: What attacks on Asians reveal about American identity. BBC News . https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-52714804 . Accessed 29 May 2020.

Chiu, A. (2020). UC Berkeley apologizes for coronavirus post listing xenophobia under ‘normal reactions’ to the outbreak. The Washington Post . https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/01/31/berkeley-coronavirus-xenophobia/ . Accessed 2 Jun 2020.

Choy, C., & Tajima-Pena, R. (1987). Who killed Vincent Chin? http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0096440/ . Accessed 2 Jun 2020.

Driscoll, E. (2020). Update: Racist death threats lodged against Seymour restaurant. Valley Independent Sentinel . https://valley.newhavenindependent.org/archives/entry/update_racist_death_threats_lodged_against_seymour_restaurant/ . Accessed 26 Apr 2020.

Eichelberger, L. (2007). SARS and New York’s Chinatown: The politics of risk and blame during an epidemic of fear. Social Science & Medicine, 65 (6), 1284–1295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.04.022 .

Ellerbeck, A. (2020). Over 30 percent of Americans have witnessed COVID-19 bias against Asians, poll says. NBC News . https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/over-30-americans-have-witnessed-covid-19-bias-against-asians-n1193901 . Accessed 6 May 2020.

Fauver, J. R., Petrone, M. E., Hodcroft, E. B., Shioda, K., Ehrlich, H. Y., Watts, A. G., Vogels, C. B. F., Brito, A. F., Alpert, T., Muyombwe, A., Razeq, J., Downing, R., Cheemarla, N. R., Wyllie, A. L., Kalinich, C. C., Ott, I., Quick, J., Loman, N. J., Neugebauer, K. M., et al. (2020). Coast-to-coast spread of SARS-CoV-2 in the United States revealed by genomic epidemiology [Preprint]. Public and Global Health . https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.25.20043828 .

Fuchs, C. (2018). Kansas man sentenced to life for killing Indian engineer in a bar. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/kansas-man-sentenced-life-prison-hate-crime-shooting-n898361 . Accessed 2 Jun 2020.

Gomera, M. (2020). How to prevent outbreaks of zoonotic diseases like COVID-19. Aljazeera . https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/prevent-outbreaks-zoonotic-diseases-covid-19-200404130822685.html . Accessed 26 Apr 2020.

Gonzalez-Reiche, A. S., Hernandez, M. M., Sullivan, M., Ciferri, B., Alshammary, H., Obla, A., Fabre, S., Kleiner, G., Polanco, J., Khan, Z., Alburquerque, B., van de Guchte, A., Dutta, J., Francoeur, N., Melo, B. S., Oussenko, I., Deikus, G., Soto, J., Sridhar, S. H., … van Bakel, H. (2020). Introductions and early spread of SARS-CoV-2 in the New York City area. [Preprint]. MedRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.08.20056929

Goodell, E., & Mann, D. (2020). Take the corona back you ******: Yakima police investigate racist graffiti at Asian buffet. Yaktri News . https://www.yaktrinews.com/take-the-corona-back-you-yakima-police-investigate-racist-graffiti-at-asian-buffet/ . Accessed 26 Apr 2020.

Gura, D. (2020). U.S. jobless claims reach 26 million since coronavirus hit, wiping out all gains since 2008 recession. NBC News . https://www.nbcnews.com/business/business-news/u-s-jobless-claims-reach-26-million-coronavirus-hit-wiping-n1190296 . Accessed 27 Apr 2020.

Ishisaka, N. (2018). Sikh Captain America fights intolerance and bigotry. The Seattle Times . https://www.seattletimes.com/entertainment/sikh-captain-america-fights-intolerance-and-bigotry/ . Accessed 6 May 2020.

Jeung, R., & Nham, K. (2020). Incidents of coronavirus-related discrimination . Retrieved from http://www.asianpacificpolicyandplanningcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/STOP_AAPI_HATE_MONTHLY_REPORT_4_23_20.pdf . Accessed 6 May 2020.

Kang, E. Y.J. (2020). Asian Americans feel the bite of prejudice during the COVID-19 pandemic . NPR.Org. https://www.npr.org/local/309/2020/03/31/824397216/asian-americans-feel-the-bite-of-prejudice-during-the-c-o-v-i-d-19-pandemic . Accessed 27 Apr 2020.

Kim, C. J. (1999). The racial triangulation of Asian Americans. Politics and Society, 27 (1), 105–138. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329299027001005 .

Lefler, D., & Heying, T. (2020). Kansas official: Pandemic isn’t a problem here because there are few Chinese people. The Kansas City Star. https://www.kansascity.com/opinion/editorials/article241353836.html . Accessed 27 Apr 2020.

Leung Coleman, M. (2020). Coronavirus is inspiring anti-Asian racism: This is our political awakening. The Washington Post . https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2020/03/25/coronavirus-is-inspiring-anti-asian-racism-this-is-our-political-awakening/ . Accessed 2 Jun 2020.

Levenson, T. (2020). Stop trying to make “Wuhan virus” happen. The Atlantic . https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/03/stop-trying-make-wuhan-virus-happen/607786/ . Accessed 26 Apr 2020.

Liu, C. (2020). Being Asian American in the time of COVID-19. The Daily Nexus . http://dailynexus.com/2020-04-21/being-asian-american-in-the-time-of-covid-19/ . Accessed 27 Apr 2020.

Mackenzie, J. S., & Smith, D. W. (2020). COVID-19: A novel zoonotic disease caused by a coronavirus from China: What we know and what we don’t. Microbiology Australia, 41 (1), 45–50. https://doi.org/10.1071/MA20013 .

Madani, D. (2020). Woman needed stitches after anti-Asian hate crime attack on city bus, NYPD says. NBC News . https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/woman-needs-stitches-after-anti-asian-hate-crime-attack-city-n1177146?fbclid=IwAR2ZRdKsLW7ksNaIt3SVdP_T4zNEkl25CLWbNsLRJAlE9EwoRpD32wbO0GU . Accessed 26 April 2020.

Maitra, S. (2020). The Wuhan virus is finally awakening Europe to China’s imperialism. The Federalist . https://thefederalist.com/2020/04/21/the-wuhan-virus-is-finally-awakening-europe-to-chinas-imperialism/ . Accessed 27 Apr 2020.

Margolin, J. (2020). FBI warns of potential surge in hate crimes against Asian Americans amid coronavirus. ABC News . https://abcnews.go.com/US/fbi-warns-potential-surge-hate-crimes-asian-americans/story?id=69831920. . Accessed 26 April 2020

Marquardt, A., & Hansler, J. (2020). US push to include “Wuhan virus” language in G7 joint statement fractures alliance. CNN Politics . https://www.cnn.com/2020/03/25/politics/g7-coronavirus-statement/index.html . Accessed 2 Jun 2020.

Mohr, J. C. (2004). Plague and fire: Battling black death and the 1900 burning of Honolulu’s Chinatown . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Molina, N. (2006). Fit to be citizens? Public health and race in Los Angeles, 1879–1939 . Berkeley: University of California Press.

Moore, T., & Cassady, D. (2020). Brooklyn woman burned outside home in possible acid attack. New York Post . https://nypost.com/2020/04/06/brooklyn-woman-burned-outside-home-in-possible-acid-attack/ . Accessed 26 April 2020.

NYPD. (2020). NYPD Announces citywide crime statistics for April 2020 . New York City Police Department. http://www1.nyc.gov/site/nypd/news/p0504a/nypd-citywide-crime-statistics-april-2020 . Accessed 7 May 2020.

Okamoto, D., & Mora, G. C. (2014). Panethnicity. Annual Review of Sociology, 40 (1), 219–239. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-071913-043201 .

Okihiro, G. Y. (2014). Margins and mainstreams: Asians in American history and culture . Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Oliveira, N. (2020). Brute attacks, shouts at Asian man, 92, in Vancouver. New York Daily News . https://www.nydailynews.com/news/crime/ny-vancouver-hate-crime-brute-attacks-shouts-at-elderly-asian-man-20200424-wyr66kgierf55obk5cx6yeusci-story.html . Accessed 26 April 2020.

Omi, M., & Winant, H. (2014). Racial formation in the United States . New York: Routledge.

Parascandola, R. (2020). Asian man spit on, threatened in NYC coronavirus hate crime. New York Daily News . https://www.nydailynews.com/coronavirus/ny-coronavirus-hate-crime-brooklyn-subway-spit-20200325-h4w4nzb74fbadpx6li4f7xdoc4-story.html . Accessed 26 April 2020.

Parnell, W. (2020). Coronavirus-inspired crook robs woman of cellphone, spews hate. New York Daily News . https://www.nydailynews.com/coronavirus/ny-coronavirus-cellphone-robbery-hate-crime-brooklyn-subway-20200322-ufznc24nybcencdtja2ycbsx2i-story.html . Accessed 26 April 2020.

Perry, B. (2003). Hate and bias crime: A reader . New York: Routledge.

Pettersson, H., Manley, B., & Hern, S. (2020). Tracking coronavirus’ global spread . CNN. https://www.cnn.com/interactive/2020/health/coronavirus-maps-and-cases . Accessed 29 May 2020.

Randall, D. K. (2019). Black death at the Golden Gate: The race to save America from the bubonic plague . New York: W.W. Norton.

Roberts, N. (2020). As COVID-19 spreads, Manhattan’s Chinatown contemplates a bleak future . Marketplace. https://www.marketplace.org/2020/03/16/as-covid-19-spreads-manhattans-chinatown-contemplates-a-bleak-future/ . Accessed 6 May 2020

Rogers, K., Jakes, L., & Swanson, A. (2020). Trump defends using ‘Chinese virus’ label, ignoring growing criticism. The New York Times . https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/18/us/politics/china-virus.html . Accessed 27 April 2020.

Saito, N. T. (1997). Model minority, yellow peril: Functions of foreignness in the construction of Asian American legal identity. Asian Law Journal, 4 , 71.

Schwartz, I. (2020). Media called coronavirus “Wuhan” or “Chinese Coronavirus” dozens of times. Real Clear Politics . https://www.realclearpolitics.com/video/2020/03/12/media_called_coronavirus_wuhan_or_chinese_coronavirus_dozens_of_times.html . Accessed 27 April 2020.

Shah, N. (2001). Contagious divides . Berkeley: University of California Press.

Sheldon, C. (2020). Girl charged with racially assaulting Asian woman over coronavirus . NJ.Com. https://www.nj.com/coronavirus/2020/04/girl-charged-with-racially-assaulting-asian-woman-over-coronavirus.html?utm_content=nj_twitter_njdotcom&utm_source=twitter&utm_campaign=njdotcom_sf&utm_medium=social . Accessed 26 Apr 2020.

Tang, T. (2020). From guns to GoPros, Asian Americans seek to deter attacks . WGME. https://wgme.com/news/nation-world/from-guns-to-gopros-asian-americans-seek-to-deter-attacks-04-24-2020 . Accessed 7 May 2020.

Trauner, J. B. (1978). The Chinese as medical scapegoats in San Francisco, 1870-1905. California History, 57 (1), 70–87. https://doi.org/10.2307/25157817 .

Tuan, M. (1998). Forever foreigners or honorary whites? The Asian ethnic experience today . New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Walker, A. (2020). News outlets contribute to anti-Asian racism with careless stock photos on coronavirus coverage. Media Matters for America . https://www.mediamatters.org/coronavirus-covid-19/news-outlets-contribute-anti-asian-racism-careless-stock-photos-coronavirus . Accessed 6 May 2020.

Wang, J. (2020). Vandals tag downtown Asian restaurant with racist message. KOB4 . https://www.kob.com/coronavirus/vandals-tag-downtown-asian-restaurant-with-racist-message/5677160/ . Accessed 27 Ap 2020.

Washer, P. (2004). Representations of SARS in the British newspapers. Social Science & Medicine, 59 (12), 2561–2571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.03.038 .

Wong, B. (2020). For Asian Americans, there are two pandemics: COVID-19 and daily bigotry. Huffington Post . https://www.huffpost.com/entry/asian-american-racism-coronavirus_l_5e790a71c5b63c3b64954eb4 . Accessed 27 April 2020.

Secon, H., & Woodward, A. (2020, April 7). About 95% of Americans have been ordered to stay at home. This map shows which cities and states are under lockdown. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/us-map-stay-at-home-orders-lockdowns-2020-3 . Accessed 26 April 2020.

Wu, E. D. (2015). The color of success: Asian Americans and the origins of the model minority . Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Wu, F. H. (2002). Where are you really from? Asian Americans and the perpetual foreigner syndrome. Civil Rights Journal, 6 (1), 14+. Accessed 2 June 2020.

Yam, K. (2020a). UC Berkeley health account calls xenophobia a “common reaction” to coronavirus. NBC News . https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/uc-berkeley-health-account-calls-xenophobia-common-reaction-coronavirus-n1127271 . Accessed 26 April 2020.

Yam, K. (2020b). Civil rights commission agrees to senate Democrats’ call for action against anti-Asian racism. NBC News . https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/civil-rights-commission-agrees-senate-democrats-call-action-against-anti-n1207136?fbclid=IwAR3vsE3rCMg7hsjBCnBswa_95LRVyjfIIf27y3j_wKuxWafkhUtcVXGvOXM . Accessed 29 May 2020.

Yang, A. (2020). Andrew Yang: We Asian Americans are not the virus, but we can be part of the cure. Washington Post . https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2020/04/01/andrew-yang-coronavirus-discrimination/ . Accessed 26 Apr 2020.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge support from the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, the MacMillan Center, and the Council for East Asia at Yale University. We are also grateful for the support of the Laboratory Program for Korean Studies through the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the Korean Studies Promotion Service of the Academy of Korean Studies (AKS-2016-LAB-2250002).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Sociology, Yale University, 493 College Street, New Haven, CT, 06511, USA

Hannah Tessler, Meera Choi & Grace Kao

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Hannah Tessler .

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Tessler, H., Choi, M. & Kao, G. The Anxiety of Being Asian American: Hate Crimes and Negative Biases During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am J Crim Just 45 , 636–646 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-020-09541-5

Download citation

Received : 08 May 2020

Accepted : 03 June 2020

Published : 10 June 2020

Issue Date : August 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-020-09541-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Asian American

- Racial discrimination

- Bias incident

- Racialization

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Subscribe Now

Being & Becoming: Asian In America

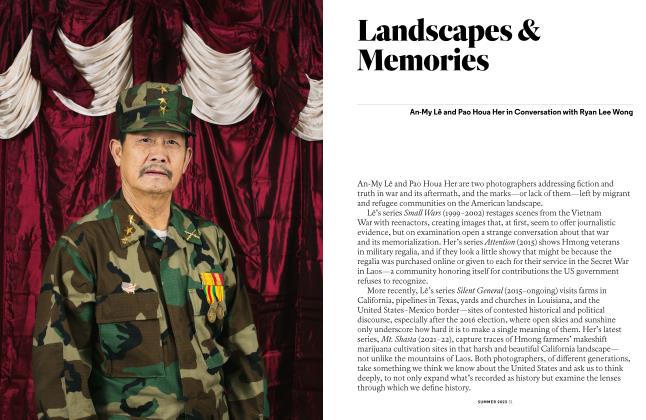

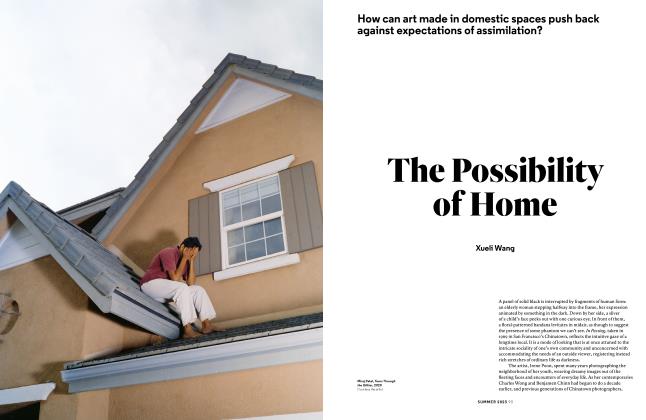

How have Asian American artists explored the unspoken tensions between the past and present—and made visible new possibilities for the future?

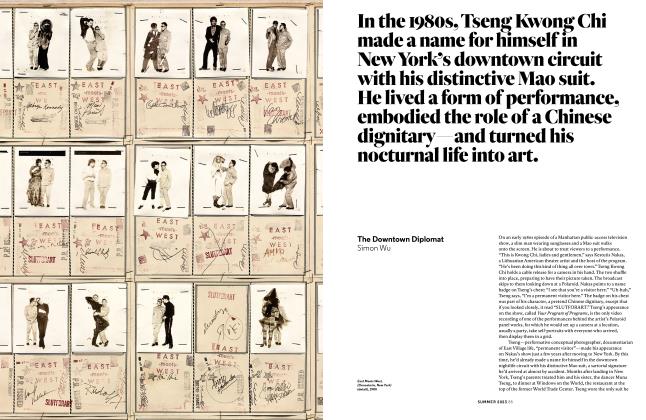

Being & Becoming: Asian In America Stephanie Hueon Tung SUMMER 2023

Being & Becoming: Asian in America

Stephanie Hueon Tung

In the summer of 1953, Charles Wong’s photo-essay “1952 / The Year of the Dragon” was published in the fifth issue of Aperture. The impetus for Wong’s piece—a carefully designed sequence of photography and poetry—was an extortion scheme that had plagued the immigrant community in San Francisco’s Chinatown. The perpetrators peppered vulnerable immigrants with fake notices about kidnapped family members in China. Cut off from communication by the Communist Revolution, many of the scheme’s victims opted to pay an expensive ransom, while others made the difficult decision to forsake their loved ones to imagined captors. The themes of Wong’s work—immigrant displacement, vulnerability, memory, and intergenerational trauma—reveal wounds of the Asian American immigrant experience that feel no less raw today. Wong’s piece might be read as a statement about the impossible choices and pain of forgetting that building a new life in this country continually demands.

As guest editor of this issue of Aperture, I have found solace and inspiration, throughout my research, in seeing how generations of artists have used the medium of photography to grapple with questions of visibility, belonging, and what it means to be Asian American, lust as there is no single point where Asian American experience converges, photography produced by Asian American image makers encompasses disparate ways of viewing the world—and demands to be approached as such. But to seek connection and coherence among these perspectives is to acknowledge a shared story of immigration to the United States that relates to a long legacy of exclusionary policies and struggles for recognition and citizenship. Being and becoming Asian in America is an unfixed, constantly evolving, and expansive process, and photography plays an essential role in envisioning it.

Since the first Asian immigrants arrived in America in the mid-nineteenth century, social visibility has conferred vulnerability. Our modern-day system of passport controls was based upon nineteenth-century forms of visual policing developed specifically to regulate the movement of Chinese and Japanese bodies, the first national methods of biometric identification to utilize photography. Falling under the gaze of the camera was an experience shared by most Asian immigrants, not primarily as a hobby of self-documentation or leisure but as a bureaucratic fact of racialized surveillance and policing.

Under the threat of deportation or detention, many early immigrants opted for self-effacement and erasure as strategies for survival. A daguerreotype from 1850s California that shows a young, working-class Chinese woman cradling a picture of an absent loved one in her hand is a rare exception. The dearth of historical photographs portraying Asian men and women at ease speaks to contested ideas of place, identity, and belonging that continue to shape our collective image of the United States.