- Complete My Donation

- Why Save the Children?

- Charity Ratings

- Leadership and Trustees

- Strategic Partners

- Media, Reports & Resources

- Financial Information

- Where We Work

- Hunger and Famine

- Ukraine Conflict

- Climate Crisis

- Poverty in America

- Policy and Advocacy

- Emergency Response

- Ways to Give

- Fundraise for Kids

- Donor-Advised Funds

- Plan Your Legacy

- Advocate for Children

- Popular Gifts

- By Category

- Join Team Tomorrow

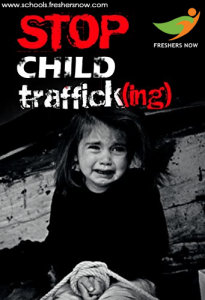

The Fight Against Child Trafficking

Child trafficking is a crime – and represents the tragic end of childhood.

Child trafficking refers to the exploitation of girls and boys, primarily for forced labor and sexual exploitation. Children account for 27% of all the human trafficking victims worldwide, and two out of every three child victims are girls[i].

Sometimes sold by a family member or an acquaintance, sometimes lured by false promises of education and a "better" life — the reality is that these trafficked and exploited children are held in slave-like conditions without enough food, shelter or clothing, and are often severely abused and cut off from all contact with their families.

Children are often trafficked for commercial sexual exploitation or for labor, such as domestic servitude, agricultural work, factory work and mining, or they’re forced to fight in conflicts. The most vulnerable children, particularly refugees and migrants, are often preyed upon and their hopes for an education, a better job or a better life in a new country.[ii]

Every country in the world is affected by human trafficking, and as a result, children are forced to drop out of school, risk their lives and are deprived of what every child deserves – a future.

Help Children Now

Child Trafficking: Myth vs. Fact

Child trafficking affects every country in the world , including the United States. Children make up 27% of all human trafficking victims worldwide, and two out of every three identified child victims are girls[i].

Trafficking, according to the United Nations, involves three main elements[ii]:

- The act: Recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring, or receipt of persons.

- The means: Threat or use of force, coercion, abduction, fraud, deception, abuse of power or vulnerability, or giving payments or benefits to a person in control of the victim.

- The purpose: For the purpose of exploitation, which includes exploiting the prostitution of others, sexual exploitation, forced labor, slavery or similar practices and the removal of organs.

There is much misinformation about what trafficking is, who is affected and what it means for a child to be trafficked. Read on to learn more about the myths vs. facts of child trafficking.

MYTH: Traffickers target victims they don’t know

FACT: A majority of the time, victims are trafficked by someone they know, such as a friend, family member or romantic partner.

MYTH: Only girls and women are victims of human trafficking

FACT: Boys and men are just as likely to be victims of human trafficking as girls and women. However, they are less likely to be identified and reported. Girls and boys are often subject to different types of trafficking, for instance, girls may be trafficked for forced marriage and sexual exploitation, while boys may be trafficked for forced labor or recruitment into armed groups.

MYTH: All human trafficking involves sex or prostitution

FACT: Human trafficking can include forced labor, domestic servitude, organ trafficking, debt bondage, recruitment of children as child soldiers , and/or sex trafficking and forced prostitution.

MYTH: Trafficking involves traveling, transporting or moving a person across borders

FACT: Human trafficking is not the same thing as smuggling, which are two terms that are commonly confused. Trafficking does not require movement across borders. In fact, in some cases, a child could be trafficked and exploited from their own home. In the U.S., trafficking most frequently occurs at hotels, motels, truck stops and online.

MYTH: People being trafficked are physically unable to leave or held against their will

FACT: Trafficking can involve force, but people can also be trafficked through threats, coercion, or deception. People in trafficking situations can be controlled through drug addiction, violent relationships, manipulation, lack of financial independence, or isolation from family or friends, in addition to physical restraint or harm.

MYTH: Trafficking primarily occurs in developing countries

FACT: Trafficking occurs all over the world, though the most common forms of trafficking can differ by country. The United States is one of the most active sex trafficking countries in the world, where exploitation of trafficking victims occurs in cities, suburban and rural areas. Labor trafficking occurs in the U.S., but at lower rates than most developing countries.

Does child trafficking happen in the United States?

Yes, children are targeted for trafficking in the U.S. and are trafficked into the country from around the world. Often, children are trafficked from developing to developed countries. Victims are trafficked under various circumstances, including prostitution, online sexual exploitation, the illegal drug trade and forced labor.

In the U.S., 60% of child sex trafficking victims have a history in the child welfare system[iv]. Foster children in particular are vulnerable to being victimized by child trafficking[iiv]. Children in the foster care system often live in of the poorest communities in America, where Save the Children works to break the cycle of poverty and ensure that every child gets a healthy start, a quality education, and is protected.

How many children are victim to child trafficking?

An estimated 1.2 million children are affected by trafficking at any given time [iiv] . Around the world, most children who are victims of trafficking involved in forced labor. Worldwide:

- 168 million children are victims of forced labor [iv]

- 215 million children are engaged in child labor [iii]

- 115 million of those children are involved in hazardous work [iii]

How does trafficking differ from smuggling?

Trafficking and smuggling are terms that are commonly mixed up or considered synonymous. They both involved transporting another individual, but there are some critical differences.

Smuggling involves the illegal entry of a person into a state where he or she is not a resident.

There are three key differences between trafficking and smuggling [iv] :

- Consent – Individuals involved have consented to the smuggling. Trafficking victims either have not consented or have been coerced into consent.

- Exploitation – When the smuggled individual arrives at their destination, the smuggling ends. Trafficking is the continuous exploitation of a victim to generate profit for the traffickers.

- Transnationality – A person who is smuggled is always brought from one state to another. Trafficking can occur either within or between states.

How is Save the Children helping victims of child trafficking?

Save the Children works to combat child trafficking through prevention, protection, and prosecution. In order to maximize our efforts, we work with communities, local organizations and civil society, and national governments to protect children from being exploited – and to help restore the dignity of children who have survived.

Save the Children takes a holistic approach to tackle the root causes of child trafficking and involves children in the design and implementation of solutions.

Working alongside communities and local and national governments Save the Children supports:

- Preventing trafficking at the community level by creating awareness of the risks of migration

- Providing support to children who have been trafficked and help them return home and reintegrate into their communities

- Improving law enforcement and instigate legal reform to protect survivors of trafficking.

By supporting livelihoods, we help families avoid the need for their children to work. By raising awareness of trafficking, we reduce the number of children being trafficked. By helping rehabilitate survivors, we empower them to rebuild their lives. By protecting unaccompanied refugee children, we keep them from the clutches of traffickers.

We Launch Anti-Trafficking Advocacy Campaigns With all the excitement that led up to the South Africa World Cup 2010, it is easy to forget that such a major sporting event can lead to child trafficking and unsafe child migration. To help protect children during this time, and raise community awareness of the dangers, Save the Children in Mozambique launched an advocacy campaign called "Open Your Eyes" with radio and television programs, interviews, posters and postcards that reached 250,000 people

The former national team captain, Tico-Tico, even volunteered his own time to appear in several advertisements highlighting the problem of child trafficking. Even after the World Cup was over, this advocacy worked to help protect vulnerable children from exploitation

We Support Public Policy and Training One reason trafficking and exploitation of children flourish is because of inadequate laws and policies against it. In El Salvador, Save the Children focused on Mejicanos, one of the most frequent areas for trafficking of children, and supported the municipal council in drafting the first-ever ordinance to prevent child trafficking, and monitor its implementation.

Save the Children also conducts awareness training in schools, so children can learn how to keep safe, as well as how and where to report any suspicious activity. Now the majority of Mejicanos are working with Save the Children to share this experience and replicate its success throughout El Salvador.

We Use Research in Creative Ways to Protect Children from Child Trafficking “Positive deviance” – an innovative approach pioneered by Save the Children and well-documented in improving children’s health and nutrition, is also being used to fight child trafficking. Save the Children used this approach in two child protection programs — one to prevent trafficking in girls for commercial sex work in Indonesia, and the other to reintegrate girls who were abducted by the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA) and girl mothers into their communities in Uganda.

When is World Trafficking Day?

In 2013, the United Nations passed a resolution designating July 30 as World Day Against Trafficking in Persons to raise awareness about the growing issue of human trafficking and the protection of victims and their rights.

Who can I contact if I witness or suspect child trafficking?

The Childhelp® National Child Abuse Hotline – Professional crisis counselors will connect you with a local number to report abuse. Call: 1-800-4-A-CHILD (1-800-422-4453)

The National Center for Missing & Exploited Children® (NCMEC) – Aimed at preventing child abduction and exploitation, locating missing children, and assisting victims of child abduction and sexual exploitation. Call: 1-800-THE-LOST (1-800-843-5678)

National Human Trafficking Resource Center – A 24-hour hotline open all day, every day, which helps identify, protect, and serve victims of trafficking. Call: 1-888-373-7888.

How Girls Are Affected By Trafficking

Tragically, both girls and boys are vulnerable to child trafficking. However, girls are disproportionally targeted and must deal with the life-long effects of gender inequality and gender-based violence .

Often, girls around the world are forced to drop out of school or denied access to income-generating opportunities. This resulting social exclusion can trap girls in a cycle of extreme poverty, as well as increased vulnerability to trafficking and exploitation.

Child Trafficking in Conflict Zones

Because child trafficking is often linked with lucrative criminal activity and corruption, it is hard to estimate how many children suffer, but trafficking and exploitation is an increasing risk as more children around the world live in conflict.

Globally, 426 million children live in conflict zones today . That’s nearly one-fifth of the world’s children. Living amidst conflict increases children’s exposure to grave human rights violations, which include child trafficking and gender-based violence.

Frequently Asked Questions About Child Trafficking

What is child trafficking.

Child trafficking is a type of human trafficking. According to the United Nations, trafficking involves three main elements [iv] :

- The act - Recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring, or receipt of persons.

- The means - Threat or use of force, coercion, abduction, fraud, deception, abuse of power or vulnerability, or giving payments or benefits to a person in control of the victim.

- The purpose - For the purpose of exploitation, which includes exploiting the prostitution of others, sexual exploitation, forced labor, slavery or similar practices and the removal of organs.

National Human Trafficking Resource Center – A 24-hour hotline open all day, every day, which helps identify, protect, and serve victims of trafficking. Call: 1-800-373-7888.

[i] Give Her a Choice: Building A Better Future For Girls (Save the Children) [ii] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Child Victims of Human Trafficking: Fact Sheet [iii] The Many Faces of Exclusion: 2018 End of Childhood Report [iv] United Nations Office on Drug and Crime [v] United Nations: World Day Against Human Trafficking [iv] National Foster Youth Institute [vii] Child Trafficking Essentials

Sign Up & Stay Connected

Thank you for signing up! Now, you’ll be among the first to know how Save the Children is responding to the most urgent needs of children, every day and in times of crisis—and how your support can make a difference. You may opt-out at any time by clicking "unsubscribe" at the bottom of any email.

By providing my mobile phone number, I agree to receive recurring text messages from Save the Children (48188) and phone calls with opportunities to donate and ways to engage in our mission to support children around the world. Text STOP to opt-out, HELP for info. Message & data rates may apply. View our Privacy Policy at savethechildren.org/privacy.

Child trafficking

Combating child trafficking.

Each year, more than 10,000 people are identified as victims of trafficking around the world. Of these victims, 13% are girls and 9% boys (UNODC, 2009). These figures only represent a small proportion of the victims identified. Closely linked to child labour , child trafficking is present in all regions of the world . In particular, it responds to demands for cheap or free labour and leads to various forms of child exploitation, such as forced marriage, prostitution, and begging, thus depriving children of their fundamental rights .

Definition of child trafficking

Child trafficking is the process of exploiting a child through the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receiving of a child (International Labour Office, 2011). Under international law, child trafficking is a crime and a violation of children’s rights . In particular, the 1989 International Convention on the Rights of the Child stipulates that “the illicit transfer and non-return of children” are prohibited.

Child trafficking is also characterised by the practice of illicit acts, namely, the use of force or coercion:(by abduction, deception, fraud or abuse of authority) or the offer of payments or benefits: to the victim or to a person having authority over them. Child victims of trafficking suffer abuse and are also, for the most part, deprived of their fundamental rights such as the right to education , the right to health or the right to protection , which are necessary for fulfilled growth (UN Info, 2015).

According to UNICEF, “some 8.4 million young people are involved in the worst forms of child labour, including prostitution. Many are enslaved: forced to work to pay off a debt, they live in a situation similar to that of slavery” (UNICEF, 2005). According to the ILO, a child trafficker is defined as “any person who contributes to any element of the trafficking process with the intention of exploiting the child. This includes those who are not active in any phase of the process, such as recruiters, intermediaries, document providers, transporters, corrupt officials, service providers, and unethical employers” (International Labour Office, 2011).

Forms of exploitation

Trafficked children are used in various ways depending on their age and sex (Terre des Hommes, 2004), as described below.

Sexual exploitation

It is mainly adolescent girls who are used for prostitution or the production of child pornography. These practices are particularly widespread in sex tourism destinations. Teenage girls are generally sold in other countries and travel under false identity papers. According to UNODC, sexual exploitation accounts for 79% of human trafficking (UNODC, 2009).

Although sex tourism has largely declined since the Covid crisis, a new form of sexual exploitation of children is booming: child pornography. In the Philippines, around one child in five, or almost 2 million children, are at risk of being sexually exploited.

Extreme poverty and broadband access in regions of extreme poverty are factors in this phenomenon. In order to improve their living conditions, parents exploit their children as merchandise by sending child pornography to people abroad in return for payment (Bicker, 2022).

Forced marriage

Forced marriage of teenage girls, although on the decline, still exists in various forms, such as arranged marriages and kidnappings. This practice is particularly widespread in China due to the shortage of women resulting from the “one-child family” policy. It is often carried out by “marriage brokers” and is spreading internationally. According to UNICEF, more than 80 million girls worldwide are married before the age of 18 (UN Info, 2015).

As with most forms of child exploitation, adoption has been turned into a profitable business by traffickers. This concerns babies and young children, particularly from Latin America to North America and from Eastern Europe to Western Europe.

While some parents are paid to sell their baby or young child, there are also cases of corruption in hospitals, where mothers are told that their baby is stillborn. These recruitments are supported by falsified documents and bribery. Barbara Hintermann, Executive Director of Terre des Hommes, reported in June 2022 that 350,000 Ukrainian children had been deported and put up for adoption by Russian families since the start of the conflict in Ukraine in February 2022 (Hintermann, 2022).

Slavery is one of the worst forms of child labour . It means that children cannot leave their employer, are under the minimum working age or work for low wages (Terre des Hommes, 2004). Also, parents sometimes accept payment in advance for their child’s work, for a fixed or indefinite period. In addition, child domestic labour is a form of exploitation that has increased over the last two decades. Children are sent to live and work as domestic servants with families abroad. Traffickers take advantage of parents’ ignorance and exploit the vulnerability of working children.

In addition, although some children beg for themselves or their families , there are many cases of children being recruited and exploited to “take advantage of the public’s inclination to give charity, particularly when it is seen as a religious duty” (Terre des Hommes, 2004). Apart from this, some children are exploited to carry out illicit activities, such as burglaries, on behalf of adults who control them.

In addition, some employers take advantage of the illegal status of trafficked children to make them do dangerous work . For example, for many years, trafficked boys have been employed as camel jockeys in the Gulf States.

Finally, it is estimated that organ trafficking accounts for between 5 and 10% of kidney transplants carried out each year worldwide (Busuttil, 2012). Although there are many accounts and testimonies of this trafficking of children’s organs, there are no official sources recording such acts.

Socio-economic factors leading to child trafficking

The children most vulnerable to trafficking often come from poor backgrounds or regions at war, in political conflict and/or experiencing economic uncertainty. Indeed, these environments are much more sensitive to the economic gains linked to child trafficking. Children with little education are also vulnerable targets. Child labour is particularly associated with school drop-out.

According to the International Labour Organisation, “More than a quarter of children aged 5 to 11 and more than a third of children aged 12 to 14 in child labour are out of school” (International Labour Organisation, 2022). Finally, children who are victims of discrimination, persecution or former victims of trafficking are more likely to (again) become victims of trafficking, as they are unaware of their fundamental rights .

On the other hand, recourse to child trafficking can be explained by various socio-economic factors such as the demand for cheap or free labour in certain sectors to reduce production costs and thus selling prices.

Inequalities between countries in terms of education and employment, as well as a lack of equal opportunities, discrimination and abuse, also encourage child trafficking, since many people from poor countries find it difficult to find a job that will allow them to live properly, particularly if they emigrate to richer countries.

Ways of combating child trafficking

In order to combat child trafficking, 3 major areas need to be addressed (Northern Ireland Department of Justice, 2021):

- Prosecute the perpetrators of these practices through detection, investigation and conviction in order to dismantle child trafficking organisations (Northern Ireland Department of Justice, 2021);

- Protect children from trafficking and slavery by improving the identification of and support for child victims and by supporting them to reduce the harm caused by trafficking and slavery (Northern Ireland Department of Justice, 2021);

- Prevent child trafficking in the long term by tackling socio-economic inequalities around the world, reducing the demand for trafficked and enslaved children, and making trafficking and slavery practices unprofitable. It is also important to improve public and professional understanding of the issue through awareness-raising (NSPCC, 2021).

Here are a few factors that can help everyone identify trafficked children (NSPCC, 2021):

- If a child spends a large part of his or her time doing household chores and has no time to leave the house or even to play;

- If a child is orphaned or separated from his or her family, while living in poor-quality housing;

- If a child is not enrolled in school or a GP’s surgery;

- If a child is present in inappropriate places such as brothels or factories;

- If a child is reluctant to share personal information, where they live and tells a story that seems prepared in advance.

If you are concerned about a child, contact Humanium’s legal helpline , the police and/or the relevant local child protection authorities.

Written by Marie Cuvelier

Translated by Emily Kitchen

Proofread by Sharon Rees

Last updated on 21 March 2023

Bibliography:

Bicker, L. (2022, Décembre 10). Pourquoi les cas de pédophilie sont-ils en hausse aux Philippines ? Consulté le 15 Mars 2023, sur BBC News Afrique: https://www.bbc.com/afrique/articles/c84p1lvzqy0o .

Bureau International du Travail. (2011, Avril 01). Traire des enfants – Points essentiels. Consulté le 15 Mars 2023, sur ilo.org: https://www.ilo.org/ipecinfo/product/viewProduct.do?productId=16596 .

Busuttil, F. (2012, Décembre 16). Trafic d’enfants. Consulté le 01 Mars 2023, sur Humanium: https://www.humanium.org/fr/trafic-enfants/ .

Département de la Justice de l’Irelande du Nord. (2021). Modern Slavery and human trafficking strategy 2021-22. Consulté le 25 Avril 2023, sur www.justice-ni-gov.uk: https://www.justice-ni.gov.uk/sites/default/files/publications/justice/modern-slavery-strategy-27-05-v2_0.pdf .

Hintermann, B. (2022, Juin 22). letemps.ch. Consulté le 25 Avril 2023, sur letemps.ch: https://www.letemps.ch/opinions/forces-captures-deportes-scandale-enfants-dukraine .

NSPCC. (2021, Juin 14). Protecting children from trafficking and modern slavery . Consulté le 25 Avril 2023, sur learning.nspcc.org.uk: https://learning.nspcc.org.uk/child-abuse-and-neglect/child-trafficking-and-modern-slavery#article-top .

OIT. (2009, Juillet 01). Manuel de formation sur la lutte contre la traite des enfants à des fins d’exploitation de leur travail, sexuelle ou autres formes – Action politique de sensibilisation contre la traite des enfants. Consulté le 15 Mars 2023, sur ilo.org: https://www.ilo.org/ipec/Informationresources/WCMS_IPEC_PUB_10772/lang–en/index.htm .

ONU Info. (2015, Décembre 14). Des centaines de millions d’enfants exclus et “invisibles”, dénonce l’UNICEF dans son rapport annuel. Consulté le 15 Mars 2023, sur News.un.org: https://news.un.org/fr/story/2005/12/84342 .

Organisation Internationale du Travail. (2022, Avril 15). Travail des enfants – estimations mondiales 2020, tendances et chemin à suivre, résumé. Consulté le 25 Avril 2023, sur ilo.org: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_norm/—ipec/documents/publication/wcms_800300.pdf .

Terre des Hommes. (2004, Mai). Les enfants, une marchandise ? Agir contre la traite des enfants. Consulté le 15 Mars 2023, sur Terre des Hommes: https://www.tdh.ch/sites/default/files/tdh_enfants_marchandise-fr.pdf .

UNICEF. (2005). La situation des enfants dans le monde 2006 – exclus et invisibles. Consulté le 15 Mars 2023, sur UN-iLibrary: https://www.un-ilibrary.org/content/books/9789210597869/read .

UNODC. (2009, Février). Global Report on Trafficking in Persons – Human Trafficking a crime that shames us all. Consulté le 15 Mars 2023, sur UNODC: https://www.unodc.org/documents/Global_Report_on_TIP.pdf .

Petition to Stop the Destruction of the Amazon Rainforest

BE HEARD! Advocate for the protection of child rights by calling for an end to fires and deforestation in the Amazon Rainforest!

Disclaimer » Advertising

- HealthyChildren.org

- Previous Article

- Next Article

Participants

Data collection, data analysis, health and social impacts, barriers to services as stigma drivers and facilitators, stigma manifestations, and stigma outcomes, stigma drivers: victim blaming, intersecting stigmas: stigma associated with cst, intersecting stigmas: gender, intersecting stigmas: lgbtq+ status, intersecting stigmas: international or refugee status, race and ethnicity, and socioeconomic status, intersecting stigmas: physical illness, intersecting stigmas: mental illness, stigma manifestations: stigma experiences: self-stigmatization and shame, stigma manifestations: stigma experiences: family and community discrimination and shaming, stigma manifestations: stigma practices: service providers discriminate, limitations, conclusions, global perspectives on the health and social impacts of child trafficking.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- CME Quiz Close Quiz

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Get Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Carmelle Wallace , Jordan Greenbaum , Karen Albright; Global Perspectives on the Health and Social Impacts of Child Trafficking. Pediatrics October 2022; 150 (4): e2021055840. 10.1542/peds.2021-055840

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Survivors of child sex trafficking (CST) experience many health and social sequelae as a result of stigma, discrimination, and barriers to health care. Our objective was to obtain a cross-cultural understanding of these barriers and to explore the relationship between stigmatization and health outcomes through application of the Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework (HSDF).

In-depth, semistructured interviews were conducted with 45 recognized CST expert service providers. Interview data were analyzed using established content analysis procedures and applied to the HSDF.

Barriers to medical and mental health services span each socioecological level of the HSDF, indicating the various contexts in which stigmatization leads to adverse health and social outcomes. Stigmatization of CST survivors is a complex process whereby various factors drive and facilitate the marking of CST survivors as stigmatized. Intersecting stigmas multiply the burden, and manifest in stigma experiences of self-stigmatization, shame, family and community discrimination, and stigma practices of provider discrimination. These lead to reduced access to care, lack of funding, resources, and trained providers, and ultimately result in health and social disparities such as social isolation, difficulty reintegrating, and a myriad of physical health and mental health problems.

The HSDF is a highly applicable framework within which to evaluate stigmatization of CST survivors. This study suggests the utility of stigma-based public health interventions for CST and provides a global understanding of the influence and dynamics of stigmatization unique to CST survivors.

Survivors of child trafficking experience health and social impacts, including barriers to health care and social stigma and discrimination. Less is known about the complex socioecological interplay of these factors and how they may be addressed to improve survivor care.

We explore in-depth the multiplicity of stigma and discrimination experienced by survivors and provide a concrete framework for understanding the health and social impacts. This framework provides a basis for physicians, service providers, policymakers, and others who work with survivors.

Child sex trafficking (CST) is a global health crisis. The United Nations defines CST as “the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring, or receipt of a child (<18 years) for the purposes of a commercial sex act.” 1 There are ∼1 million CST survivors annually. 2 , 3

Marginalized children are particularly vulnerable. Risk factors include poverty; housing insecurity; previous abuse; substance misuse; and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer (LGBTQ+) identity. 4 Societal issues such as gender bias, systemic violence, and corruption further exacerbate vulnerability. 4 Survivors experience health consequences, including injury, infections, substance misuse, anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). 5 – 9 They also experience significant barriers to health care, 10 , 11 including fear of arrest, deportation, and trafficker retaliation; discrimination; confidentiality concerns; difficulty navigating the system; social instability; and resource constraints. 12 These health care barriers exist across the socioecological spectrum from individual, interpersonal, organization, community to policy levels and are the context within which CST survivors experience stigma.

Stigma was first described as an “attribute that is deeply discrediting,” resulting in “disqualification from full social acceptance.” 13 Research has further elaborated stigmatization as a social process enabled by cultural, economic, and structural influences that label, stereotype, and exclude the affected person or group. The result is discrimination or unfair and unjust treatment on the basis of an attribute or status.

Global research demonstrates a significant connection between stigma and poor health outcomes. 14 Understanding stigma, therefore, is pivotal in mitigating the health outcomes of marginalized populations. Previous stigma research exists on HIV, obesity, and mental illness. 15 – 20 However, stigma research on trafficking is limited. Research has described stigmatization in adult trafficking survivors in a single geographical location, but none evaluate stigma in CST survivors globally. 10 , 11 , 21 – 23

We designed a qualitative study to obtain an in-depth, cross-cultural, and global understanding of the barriers to health care experienced by CST survivors, and to explore the process of stigmatization and its effect on health. We did so through the application of the Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework (HSDF). The HSDF is well suited to this purpose for several reasons. It was derived by a globally recognized consortium of diverse stigma research experts including United Nations, international, and nongovernmental organization (NGO) affiliates. 24 It was then rigorously tested through a multicenter study that demonstrated reduction in HIV-associated stigma. 25 Although not validated in CST survivors, patients with HIV have similar vulnerabilities, and these populations often overlap. Finally, in contrast to previous stigma frameworks that focus on individual and interpersonal interactions, the HSDF evaluates stigma as a socioecological process that is influenced by organizational, community, and public policy factors. This makes the framework constructive for planning public health interventions the recommended approach to addressing trafficking. 26 A public health approach removes the focus on the individual who is the victim, shifting the weight onto the socioecological forces at play.

A detailed explanation of the HSDF has been published elsewhere. 27 Briefly, the HSDF categorizes the causes of stigma into stigma drivers, which are inherently negative perceptions that drive stigmatization, and stigma facilitators, which are positive or negative external influences such as policies and social norms ( Fig 1 ). Drivers and facilitators determine whether stigma marking occurs, wherein negative attributes are applied to the individual or group. Intersecting stigmas refer to additional coinciding stigmas that may be applied. Marking manifests in stigma experiences, defined as the stigma and discrimination experienced by the person, and stigma practices, which describe societal stereotypes, prejudices, stigmatizing behavior, and discriminatory attitudes. The HSDF surmises that these manifestations influence outcomes within the population and institutions interacting with them, ultimately leading to health and social impacts.

The Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework. 1 Used with permission. 1 Stangl AL, Earnshaw VA, Logie CH, et al. The Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework: A global, crosscutting framework to inform research, intervention development, and policy on health-related stigmas. BMC Medicine . 2019;17(1):18-23.

In-depth interviews were conducted with global CST experts and service providers working directly with survivors. Interviewees were initially recruited through professional networks, then referred and enrolled purposively to seek variance in the populations served and representation from all World Health Organization (WHO) regions and World Bank country income classifications. All participants were English-speaking.

A semistructured interview guide was used covering several domains, including health care needs, services, and barriers to care. Interviews were conducted through a secure Skype call, lasted 45 to 60 minutes, and were audio recorded then transcribed. Children’s Health Care of Atlanta institutional review board approved the protocol.

Analysis occurred in an iterative process using established content analysis procedures and reflexive team analysis. 28 , 29 Transcripts were independently read multiple times by 2 analysts to achieve immersion. Codes were then inductively derived and independently applied by each analyst to 10% of the transcripts. Intercoder reliability was assessed and disagreements resolved through consensus. The remaining transcripts were coded using the final coding schema. 30 Axial coding was also employed to group codes and elucidate trends. Throughout the analysis, team members met regularly to discuss emergent themes. 31 ATLAS.ti v8.3.1 software was used.

Forty-five experts were interviewed, representing all WHO regions and World Bank classifications. 32 , 33 Interviewees included direct service providers such as physicians, psychologists, and social workers as well as researchers and NGO leaders ( Table 1 ). Themes were synthesized by using the HSDF and are presented in Fig 2 . 27 Each aspect of the stigma schema was explored in-depth and is presented below (subject number denoted S#, World Bank classifications denoted L= low, LM = lower middle, UM = upper middle, H = high).

Interview themes organized within the Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework. Overlapping themes are italicized for emphasis on the intersectionality.

Participant Demographics

https://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/definition_regions/en/ .

https://databank.worldbank.org/home.aspx .

Several participants had 2 roles.

Participants did not specifically denote if their primary clients or patients identified as LGBTQ+ but several alluded to working with the LGBTQ+ population, and thus are implicitly included.

Several participants have worked with organizations with multiple programs or have worked with multiple organizations.

Participants reported that CST survivors experience a litany of health and social impacts. They reported social isolation, difficulty reintegrating into the community, sexually transmitted infections, reproductive health issues, seizures, malnutrition, untreated injuries, depression, anxiety, PTSD, eating disorders, and substance misuse ( Fig 2 ).

Themes describing barriers to services spanned each socioecological level of the HSDF, providing rich descriptions of the individual, interpersonal, organizational, community, and policy contexts in which stigmatization occurs ( Table 2 ). Most barriers were described in countries from all income levels. They were reflected in the model as stigma drivers, facilitators and manifestations, as well as outcomes leading to health and social impacts. Overlapping themes spanning multiple components of the model are italicized to emphasize pervasiveness ( Fig 2 ).

Barriers to Medical and Mental Health Care Presented Within Socio-Ecological Levels per HSDF With Notable Country Income Level Trends

Subject number denoted S#, World Bank classifications denoted L = low, LM = lower middle, UM = upper middle, H = high

“It is the girl's fault…She was the one who got pregnant. She shouldn't have been wearing that slutty outfit, or flirting with those boys. She basically got pregnant because she was acting like she wanted it.” (S9, LM)

Similarly, subject 26 (UM) described how the societal opinion was that survivors “just got into this stuff because they are trouble anyway.”

Many reported that trafficking itself was stigmatizing. They described a loss of position in society, calling CST “highly stigmatizing, highly disempowering” (S28, UM). Subject 26 (UM) described it as “it’s like you are dirty,” whereas subject 2 (LM) shared that it was “like these girls [were] branded.” Another described CST as “the worst thing” (S8, LM).

“Girls are like a piece of cloth. Once it is soiled, it is spoiled forever. A boy is like a piece of gold. If you just wash it clean it's fine again.” (S25, LM)

Participants also felt patriarchal attitudes contributed to stigma against males. Subject 25 (LM) explained that boys were not allowed to reveal weaknesses, “because they need to just brush themselves down and pick themselves up and get on with life.”

“They will be seen as less of a man. Many of those cases go unreported. But it is because of the culture. The mind sets, their attitude is more, ‘it is the weak ones that should go and get medicine.’” (S6, L)

“The boys we work with need care and love and compassion. And they don't get that at the hospital because they are seen as rough around the edges and homeless youth. As delinquents.” (S31, UM)

“There is a strong stigma against being perceived as gay…or ‘obla.’ Literally there is no word for ‘straight’ in Tagalog. The word for straight translates ‘real man.’” (S3, LM)

LGBTQ+ survivors were described as ostracized, and even survivors who did not identify as LGBTQ+ had “fear about does this mean I’m gay,” because they did not want to be additionally stigmatized (S21, L).

“They would be treated differently just because they are not welcomed as a citizen…There is the perception of, like migrants come in and they steal all of this from us.” (S5, LM)

“There is discrimination…if the child is Serbian, or from Albania, Croatia or Hungary…They will say something like they deserve to live like that. Or they want to live like that. Or…they are like gypsy. They are not even like the Roma population.” (S17, UM)

“There are ethnic Vietnamese girls that have been trafficked and gone through the system. And yes, they are treated very differently. They are very much looked down on.” (S1, LM)

Several also shared that socioeconomic status contributed to the multiplicity of stigma: “Trafficking is a crime that preys on the weak and the most poor and impoverished communities.” (S2, LM)

Stigma because of the physical sequalae of exploitation was also highlighted. Subjects described trafficking-related disabilities, sexual and reproductive issues, and gastrointestinal issues as sources of shame. Subject 24 (L) stated, “imagine the child has these issues [STIs], people laugh at her or him.” Another participant described the stigmatization due to the fecal incontinence a survivor was experiencing as “another whole layer of shame” (S25, LM).

“[Mental health] is not something that we appreciate in our culture…actually, if you went into the mental hospital, they will think you are mad. Because people who are just mad or crazy, they are there.” (S6, L)

“In Hinduism there is a belief that whatever condition you have is the result of whatever you did wrong in a past life…If you have any infirmity of any kind, it is because you richly deserved it and earned it in a past life.” (S14, L)

“A lot of times [mental illness] is seen as [demon] possession.” (S44, LM)

Data also revealed that many survivors internalized these sociocultural beliefs, leading to self-stigmatization. Subject 38 (UM) described, “most of them have a self-stigma. They tell themselves I am bad, bad. I cannot be like this.” Participants described how survivors felt worthless and experienced difficulty accepting that they were exploited. They struggled to access services and remained in exploitation.

“The family. Most of their parents speak to them like you are bad. You are not proper to birth in this world. Or you are worthless.” (S38, LM)

Many participants described community rejection and difficulty reintegrating, either from the shame of trafficking itself or from time spent in aftercare facilities: “The community stigmatized them and said ‘you are the kids who went to live with the foreigners.’” (S30, LM). The degree of discrimination varied from shunning to violence, and many described how the community “will blame you and treat you badly” (S38, UM).

“There were many boys in prostitution…The police basically said there was not an issue about the boys. Even though they knew.” (S24, L)

“This boy has been raped. He is bleeding…And all the doctor basically didn't do an exam…then wrote on the report, this boy has not been sexually abused.” (S30, LM)

Interviewees felt that provider discrimination prevented survivors from accessing services: “There are people who don't want to go because of the discrimination that they will face. (S4, UM)

This unique data set provides an in-depth yet global view of CST survivor health inequities through the lens of stigmatization. Current work has explored stigmatization of survivors generally, but few studies address how the stigmatization process weaves its way from individual-level interactions to system-level outcomes, directly affecting health and social well-being. 21 , 22 , 34 – 36

Our themes reveal how stigma drivers like victim blaming and survivor mistrust of providers propel external stigmatization and self-stigmatization. Although self-stigmatization has been described, our study articulates its interaction with external factors and victim blaming in CST survivors with more depth. 37 We also identified several key barriers to care that are stigma facilitators, including providers who lack training in trauma-sensitive techniques and specialized care of survivors, fragmented care, lack of legal protections, and systemic corruption and inequities. Although these barriers have been previously reported, the HSDF sheds light on the influence of stigma on these barriers. 12 Importantly, these barriers are opportunities for destigmatizing interventions, which could include increasing trauma-sensitive and trafficking-specific training for providers, implementation of policies that support bolstering the workforce of providers qualified to work with CST populations, and educating professionals at large on the social and cultural factors that influence stigmatization.

Our participants described an alarming number of intersecting stigmas, including gender bias, LGBTQ+ status, race, refugee or international status, socioeconomic status, and physical and mental illness. Many of these stigmas have been described previously and individually, but separately from their interaction with CST. 37 , 38 This suggests interventions should also address these additional stigmas.

Our data support the HSDF’s assertion that stigma experiences and practices are linked to outcomes affecting survivor well-being. Participants broadly described reduced access to care and paucities of funding, resources, training, and qualified providers. Intuitively, these are directly linked to health and social outcomes, which our participants described as social isolation, difficulty with reintegrating into community, as well as a plethora of physical and mental health problems.

Understanding CST survivor stigmatization via the HSDF makes a very complex social phenomenon concrete. It also highlights how pediatricians, mental health professionals, policymakers, advocates, and other stakeholders may participate in a global public health response. Stigma drivers, facilitators, marking, and manifestations present opportunities for intervention, including avoiding the use of harmful rhetoric, increasing public awareness regarding the intersection of CST and stigma, expanding research on stigma, increasing trafficking-specific and trauma-sensitive training opportunities, supporting funding and polices that are inclusive, and employing culturally sensitive and innovative approaches to empowering CST survivors. The HSDF Outcomes also suggest ways to monitor targeted interventions such as measuring availability and accessibility of services, amount of specific funding, and presence of policies that foster an informed workforce that protects the rights of CST survivors. Ultimately, longitudinal studies that quantify the health and social impacts of stigma reduction interventions would provide strong evidence for addressing CST. Table 3 provides a summary.

Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework-Driven Interventions and Recommendations

Although this qualitative study is in-depth, it is impossible to ascertain generalizability. Though we gathered information from a broad and diverse environment, the sample size was limited and all participants were English-speaking. Representation from a given country varied from 1 to 5 subjects. However, the remarkable thematic consistency suggests that we were able to identify critical dynamics of stigma in CST survivors globally.

Several barriers to health and mental health care were identified by participants in low- and middle-income countries only, despite abundant anecdotal evidence of their prevalence in high-income countries. This may be because of insufficient sampling or differences in perceived priorities among experts.

Although this study reflects the perspectives of experts, we recognize that these are not the perspectives of survivors. Because of the global nature of the study, we had ethical concerns about the ability to uniformly verify and monitor the capacities of each locale to support a vulnerable child being interviewed about a traumatizing subject in a resource-limited setting. Nonetheless, the perspectives of experts uniquely include the collective experience of the myriads of children they have served, providing valuable guidance on trends, issues, and priorities.

Finally, the use of the HSDF as a basis for intervention should be accompanied by appropriate cultural contextualization, as exploration of the nuances of each regional-specific culture was beyond the scope of the study.

Survivors of CST experience many health and social consequences as a result of stigma, discrimination, and barriers to health care. Stigmatization of survivors is complex and interacts with barriers to care across all socioecological levels. Evaluating the stigmatization process within the HSDF framework helps to prioritize how barriers should be addressed within interventions along each step of the stigmatization process, and how to monitor for change. Next steps should include further exploration of intersecting stigmas and testing of stigma-based interventions by measuring stigma reduction and psychosocial, mental, and physical wellbeing.

Dr Wallace conducted analysis and interpretation of the data, drafted the initial manuscript, and revised and reviewed the manuscript; Dr Greenbaum conceptualized and designed the study, conducted data acquisition, and revised and reviewed the manuscript; Dr Albright conceptualized and designed the study, supervised and conducted analysis and interpretation of the data, and revised and reviewed the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FUNDING: This study was supported by the International Centre for Missing and Exploited Children.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES: Dr Greenbaum is employed by the International Centre for Missing and Exploited Children (ICMEC). The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

child sex trafficking

Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework

lesbian, gay, bisexual transgender, queer

nongovernmental organization

posttraumatic stress disorder

World Health Organization

Advertising Disclaimer »

Citing articles via

Email alerts.

Affiliations

- Editorial Board

- Editorial Policies

- Journal Blogs

- Pediatrics On Call

- Online ISSN 1098-4275

- Print ISSN 0031-4005

- Pediatrics Open Science

- Hospital Pediatrics

- Pediatrics in Review

- AAP Grand Rounds

- Latest News

- Pediatric Care Online

- Red Book Online

- Pediatric Patient Education

- AAP Toolkits

- AAP Pediatric Coding Newsletter

First 1,000 Days Knowledge Center

Institutions/librarians, group practices, licensing/permissions, integrations, advertising.

- Privacy Statement | Accessibility Statement | Terms of Use | Support Center | Contact Us

- © Copyright American Academy of Pediatrics

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

I Was Trafficked as a Teen. Here’s What I Want People to Understand

W hen I talk about being trafficked as a teenager, people ask two questions: How did it happen, and how did nobody know it happened? For most of my life, these conversations happened with the few friends, and then recently it happened more frequently after the release of my novel, The Lookback Window , which is about recovering from sex trafficking and pursuing justice in the wake of New York’s Child Victims Act. Sex trafficking isn’t dinner conversation, and the instances where it makes the news often revolve around paranoid fantasies of the alt-right. Recently, this manifested as Sound of Freedom , the terrible, white savior film starring Jim Caviezel, which doubles as a biopic of Tim Ballard and a false charity.

Tim Ballard is a conservative multi-hyphenate who created Operation Underground Railroad, an anti-child trafficking organization, after witnessing the horrific commercial sex trade from his work in the Department of Homeland Services’ Internet Crimes Against Children task force. This is the subject of the film, his heroic origin story. Nowhere in this biopic do you ever understand anything, really, but the notes of the film feel familiar enough, as if they have been recycled from another story, another fiction, another con. In October 2023, Ballard was accused of grooming and sexually harassing women, allegedly using his work with Operation Underground Railroad as a narrative cover, asking women how far they would go to help the cause. Would they pose as his wife, sleep with him, do what it takes to save the children?

At some point in the film, Caviezel says, “Nobody cares.” The dominant narrative has been that nobody cares because no one understands how the practice exists around them. It’s a lonely feeling and a sentiment that I have felt at times in my recovery. Media like this doesn’t do much but exacerbate this feeling. It preys on the right’s xenophobia, conspiracists, and religious fanaticism under the guise of saving the children.

But the problem is that the international commercial sex trade doesn’t just exist—it persists. In fact, it lives here, in America, all around us. And by sharing what happened to me, I hope that other victims will have an easier time speaking up and advocating for justice.

When I was 14, I got a message on MySpace from a 19-year-old who also lived in my same city in Westchester, telling me that he thought I was attractive. He lived across the street from my high school and asked if I wanted to go on a date. I didn’t respond at first, but I showed a friend of mine the message, and she told me she knew him. He was a family friend. I was lonely, had a difficult relationship with my parents, and was closeted. So, I responded to the message.

When we met, he kissed me on the lips, asked my age, and then asked if I had ever smoked a blunt. I got so high I thought I was having a stroke. He asked me to be his boyfriend and then raped me in his bedroom and told me he loved me. When I was bleeding after, he said the same thing happened to him the first time he had sex, and that it was normal to bleed. I trusted him.

He’s what’s known as a “Romeo,” a pimp who lures a vulnerable person using the structure of a romantic relationship. He would give me a ring to wear, promising to marry me when I turned 18, too. He picked out a wedding date and wrote it on his wall. I don’t have many pictures from that era because my stomach turns if I’m reminded of how young I really looked, knowing what happened to me. But my family took a trip to Colorado that year and that friend who knew my rapist came along. She took pictures of the two of us, and if you look at my hand you could see the ring. I thought my boyfriend loved me.

There are other types of pimps: gorilla pimps whose main method of control is violence, CEO pimps who promise money, and familial pimps who sell the people in their family. Nothing is ever so separate, and when you’re being groomed you don’t realize what’s happening to you. He started out by telling stories of what he had done when he had been my age. They started out as cool, funny stories of hooking up with older men. The drugs he had done. Fights he had been in. That he had burned down part of his house when he was younger. (Later, after years had passed, I found out that he had been in-and-out of jail for various assaults.) He came up with a story that he was 16, if anyone asked, and that I couldn’t tell anyone about us or he could go to jail, and if I were talking about him to use a fake name.

Read More: She Survived Sex Trafficking. Now She Wants to Show Other Women a Way Out

I would skip school and walk to his house. On the weekends, I would tell my parents I was sleeping over at a different friend’s place, where he would get me high or drunk, and then post the ads on Craigslist with naked pictures of me that he had taken. Old men would reply and come over, give him money or drugs or both, and rape me in his bedroom. Some had wedding rings, some would force other drugs into me, and all of them asked how old I was. Sometimes he would drive me to their house. He would give me pills to calm me down the next day, buy me food, tell me details about the wedding. He would give me hickeys and teach me how to cover up bruises, and then by the time the older men hurt me I knew how to cover up bruises on my own. He bought me jockstraps and short shorts, and he had once casually joked about taking child porn in conversation to my friend who came to Colorado. I only know this detail because when I eventually went to the police, that friend had written it down in her diary, which was dated, and given over to the detective.

I failed classes and missed so much school my parents were alerted. I was rail thin, depressed, and was put on benzos by a psychiatrist. I was caught hanging out with this other older guy with a fake name. I wore very short shorts, tight shirts, and fell asleep during the day since I could barely sleep at night. I didn’t have many friends. All of these are considered signs that point to a risk factor.

He “broke up” with me when I was 17. I stopped looking as young as I once looked. No longer did I have braces. I went through puberty. One of the last times I saw the man who pimped me out, I told him how much he had hurt me and that I thought about going to the police. He threw my phone against the wall, beat me, and warned me what would happen if I ever told anyone. I overdosed on pills later that year, wanting to end the panic attacks, depression, and fear, but I was too young to know what had happened to me—that I was dealing with complex PTSD, and the extent of the violence.

The day after I graduated high school, I moved to San Diego without knowing anyone because I could not stomach being near the scene of the crimes. It was the farthest place away I could find. I have been in recovery for almost two decades now, and finally got the proper help I needed once I started telling people what happened. I was referred to the Crime Victims Treatment Center, a place where I could actually learn how to deal with living as someone who had once been trafficked. I could have had an easier time had I spoken more about what happened, had I known there are real treatments, had I not only thought of trafficking as something that happens far away from New York. If I had the language for what happened to me earlier, I could have saved myself years of private shame and self-destruction.

What is the sound of freedom? It’s what wakes my husband in the middle of the night as I scream in my sleep, 17 years later, and the softness of his voice telling me I’m safe. Or a notification from Instagram as a stranger who read my book tells me: “I was also trafficked as a teenager and our stories are super similar.” And the crowd asking questions about vengeance and justice at Strand Books where I talk with a friend about how angry I am and the solace I’ve found in being open. The practice of liberation requires creating room for the speech of victims. When I finish my events, I have a moment of silence for others to raise their hands, to talk after the event, to send a message. You are free to say what you need.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- The New Face of Doctor Who

- Putin’s Enemies Are Struggling to Unite

- Women Say They Were Pressured Into Long-Term Birth Control

- Scientists Are Finding Out Just How Toxic Your Stuff Is

- Boredom Makes Us Human

- John Mulaney Has What Late Night Needs

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

United Nations

Office on drugs and crime, unodc shines spotlight on causes and impact of child trafficking.

Vienna (Austria) – 20 September 2023 - Children as young as six are forced to work extensive hours in dangerous settings in quarries, mines and factories.

Others toil in extreme weather and inhumane conditions on plantations and fishing boats or work, without pay, as domestic servants.

Some are sexually abused in brothels, bars, private homes and online or forced into marriage. All these children are victims of human trafficking.

“They’re not only exploited, but may also be raped, beaten, humiliated, deprived of liberty, and forced to live in squalor - their childhoods are stolen,” says Mukundi Mutasa, a UNODC crime prevention expert.

“Many are physically and psychologically scarred for life, while others do not survive their trafficking ordeal,” he adds.

Research, conducted by UNODC, shows that some traffickers use their child victims to commit crimes, such as theft, illegal drug production, and even acts of terrorism, for which they are sometimes arrested, deported or imprisoned.

Next month, delegates from around 120 countries will meet in Vienna, Austria, and online, to discuss how to better counter child trafficking.

The discussion forms part of the annual meetings of the intergovernmental Working Group on Trafficking in Persons and centres around an in-depth paper on this topic produced by UNODC’s Human Trafficking and Migrant Smuggling Section.

Children at risk

UNODC’s latest report on global human trafficking trends shows that around 35 percent, or one in three, of detected victims of trafficking are children.

While cases of child trafficking are detected in all regions and in most countries in the world, in Central America and the Caribbean, North Africa and the Middle East, and Sub-Saharan Africa, children account for the majority of identified victims.

Children are particularly vulnerable to human trafficking for several reasons, including poverty, lack of access to education, humanitarian crises, or the lack of support networks.

“Traffickers are known to prey on children in vulnerable situations, especially when their parents or guardians struggle to support their households. This places children under pressure to contribute to the family’s income,” explains Mutasa.

The UNODC anti-trafficking expert says, in many cases, the traffickers are known to the child’s family and guardians or they target children without parental care, including those in orphanages and foster homes.

Criminals take advantage of these situations to deceive children and the adults who care for them with “fake promises of better opportunities”.

“In some cases, family members even play a role in the trafficking process, especially in the initial stages. Our research suggests that the extent of family involvement in cases of child trafficking is up to four times higher than in cases of adult trafficking,” he says.

Essential training

UNODC’s anti-trafficking experts train relevant authorities how to identify cases of human trafficking, including those that involve children, and to take the necessary steps to support the child and prosecute the traffickers.

A recent case of forced ‘marriage’ in Malawi shows the impact of this work. A female child was trafficked by her uncle and forced to live with a man she had never met before. This man had paid her uncle money for a ‘wife’.

Over a period of eight months, he would repeatedly rape, beat and abuse her. Her ordeal came to an end when neighbours heard her crying and reported this to the authorities.

Police officers trained by UNODC rescued the girl and identified the signs of trafficking for the purpose of forced marriage.

With the cooperation of UNODC’s office in Malawi, the girl is being supported by two non-profit organisations. Her uncle and her abuser are both in prison.

Impact of crises on child trafficking

According to UNODC data, existing risks for child trafficking are worsened further during times of emergency.

Natural disasters, such as floods, droughts and typhoons, and armed conflicts force children to flee their homes often unaccompanied by or, at times, separated from parents or guardians.

Deprived of opportunities and protection, the displaced, migrant or asylum-seeking children are easy targets for traffickers.

Low levels of detection

Statistics collected by UNODC indicate that in 166 countries, over 18,000 child victims of trafficking were identified in 2020.

However, anti-human trafficking experts fear the rates do not reflect the full extent of the problem, due to the clandestine nature of this crime and the lack of data collection in many parts of the world.

The Working Group will also look at issues concerning the protection of child victims, their access to justice, and the long-term impact on their well-being and health, as well as their opportunities for rehabilitation and reintegration, and the risks of re-exploitation.

“It’s the first time this expert meeting has focussed on child trafficking,” says Mukundi Mutasa.

Further information:

The Working Group on Trafficking in Persons is the principal forum within the UN system for discussion about human trafficking. It was established to facilitate exchange between crime prevention and criminal justice experts from the countries that have committed themselves to implement the UN’s Trafficking in Persons Protocol . More than ninety percent of States globally are implementing this international instrument.

- Fraud Alert

- Legal Notice

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Psychological consequences of child trafficking: An historical cohort study of trafficked children in contact with secondary mental health services

Livia ottisova.

1 King’s College London, Department of Psychology, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, De Crespigny Park, London, United Kingdom

Patrick Smith

Hitesh shetty.

2 South London and the Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, Biomedical Research Centre Nucleus, London, United Kingdom

Daniel Stahl

3 King’s College London, Department of Biostatistics, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, De Crespigny Park, London, United Kingdom

Johnny Downs

4 King’s College London, Department of Psychological Medicine, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, De Crespigny Park, London, United Kingdom

5 King’s College London, Department of Health Services and Population Research, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, De Crespigny Park, London, United Kingdom

Associated Data

BRC Case Register (CRIS) provides a means of analysing anonymised data from the South London & Maudsley Foundation NHS Trust (SLAM) electronic case records. Access to clinical information is clearly a sensitive issue and a security model was developed which has been considered and approved by the SLAM Caldicott Guardian and the Trust Executive, as well as forming part of the ethics application. We are unable to report individual-level data in the public domain because these comprise patient information, but these have been aggregated and proportions reported in full in the present paper. Researchers may apply for approval to access these or other CRIS data. Individuals wishing to apply for access to CRIS data can contact the NIHR Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) Manager, Dr. Saliha Afzal, on ku.ca.lck@yelsduamu-crb or Tel: +44 (0)20 7848 5485. More information is available at http://brc.slam.nhs.uk/about/core-facilities/cris .

Child trafficking is the recruitment and movement of people aged younger than 18 for the purposes of exploitation. Research on the mental health of trafficked children is limited, and little is known about the use of mental health services by this group. This study aimed to investigate the mental health and service use characteristics of trafficked children in contact with mental health services in England.

Methods & findings

The study employed an historical cohort design. Electronic health records of over 250,000 patients were searched to identify trafficked children, and a matched cohort of non-trafficked children was randomly selected. Data were extracted on the socio-demographic and clinical characteristics, abuse history, and trafficking experiences of the trafficked children. Logistic and linear random effects regression models were fitted to compare trafficked and non-trafficked children on their clinical profiles and service use characteristics. Fifty-one trafficked children were identified, 78% were female. The most commonly recorded diagnoses for trafficked children were post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (22%) and affective disorders (22%). Records documented a high prevalence of physical violence (53%) and sexual violence (49%) among trafficked children. Trafficked children had significantly longer duration of contact with mental health services compared to non-trafficked controls (b = 1.66, 95% CI 1.09–2.55, p<0.02). No significant differences were found, however, with regards to pathways into care, prevalence of compulsory psychiatric admission, length of inpatient stays, or changes in global functioning.

Conclusions

Child trafficking is associated with high levels of physical and sexual abuse and longer duration of contact with mental health services. Research is needed on most effective interventions to promote recovery for this vulnerable group.

Introduction

Child trafficking is a significant public health problem and human rights violation affecting millions of children worldwide. Child trafficking is defined as the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of young people for the purpose of their exploitation [ 1 ]. Globally, it is estimated that 20.9 million people are in situations of forced labour as a result of human trafficking, and that 5.5 million of these are children [ 2 , 3 ]. Children make up an increasingly large share of the total number of victims of human trafficking and comprise one third of all identified trafficked people [ 4 ].

Human trafficking is believed to affect all countries throughout the world, and these can serve as places of origin, transit and destination of trafficked individuals. Key socioeconomic drivers of human trafficking include poverty and socioeconomic inequality [ 5 ]. Children can become further vulnerable to exploitation due to illness or death of a family member or separation from the family in the context of forced migration, natural disasters, and civil unrest [ 4 , 5 ].

Given the illegal and clandestine nature of human trafficking, the exact numbers of trafficked children are unknown. Whilst official statistics on detected victims provide some information about general trends in trafficking, estimating the number of undetected victims remains a challenge [ 4 ]. Emerging research from the United Kingdom as well as national statistics indicate that children are trafficked into a range of industries, including sex work, forced marriage, domestic servitude, agricultural labour, car washing, factory labour and criminal exploitation, such as cannabis cultivation [ 6 , 7 ].

Children can experience extreme forms of exploitation and abuse in the context of human trafficking. Emerging research suggests that 24–56% of trafficked children experience physical violence and 21–51% experience sexual abuse [ 8 – 10 ]. A large body of evidence from other child populations attests to the adverse effects of physical and sexual violence on children’s physical health and wellbeing. Child physical and sexual abuse are also causally associated with a range of mental disorders, substance abuse, and suicide attempts [ 11 , 12 ]. Previous research with adults has found trafficking to be associated with high rates of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and anxiety disorders [ 9 , 13 – 15 ]. However, research on the health needs and experiences of trafficked children is scarce. Three studies conducted with victims of child trafficking provided preliminary evidence of high rates of depression, PTSD, and anxiety disorders, as well as self-harm and suicide risk [ 8 – 10 ]. However, relatively little is known about the mental health needs of trafficked children, and even less is known about those with serious mental illnesses.

The only study to date conducted with a clinical population of trafficked people in contact with mental health services found that trafficked adults were significantly more likely to be compulsorily admitted as inpatients and had longer admissions than matched non-trafficked controls. However, whether or how the mental health needs of trafficked children in contact with services differ from those of non-trafficked children is currently not known.

This study aimed to investigate the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of trafficked children in contact with secondary mental health services, and compare their pathways into services and current care with those of matched non-trafficked children. It was hypothesised that trafficked children, as compared to non-trafficked controls, would be (1) significantly more likely to have adverse pathways into care, defined as having first contact with secondary mental health services via the emergency department or police; (2) significantly more likely to be compulsorily admitted for psychiatric treatment (i.e. admitted for care under the Mental Health Act (MHA)); (3) have longer total length of contact with secondary mental health services and (4) longer inpatient admissions; and (5) would have significantly worse clinical outcomes as evidenced by less improvement in measures of global functioning.

An historical matched cohort design of trafficked and non-trafficked children in contact with secondary mental health services in South East London (UK) between 1 January 2006 and 21 November 2014. Data were obtained from the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre Clinical Record Interactive Search (CRIS) system, which provides access to electronic mental health records from South London and Maudsley (SLaM) NHS Foundation Trust, the largest provider of secondary mental health care in Europe. The CRIS database converts electronic mental health records into research-accessible datasets, preserving anonymity through technical and procedural safeguards [ 16 , 17 ]. CRIS allows for the search of over 250,000 anonymised full patient records of individuals referred to SLaM services, including over 46,000 children and adolescents (hereafter collectively referred to as children ). CRIS electronic records include all clinical and socio-demographic information recorded during patients’ contacts with SLaM services. Relevant records can be retrieved using search terms for structured fields (e.g. diagnosis) or free text (e.g. clinical event notes).

Participants

The sample consisted of trafficked and matched non-trafficked children in contact with SLaM services. Children were included in the trafficked group if they were less than 18 years old at first contact with SLaM services and their mental health records indicated that they were victims of human trafficking. Trafficking was defined in accordance with the United Nations protocol [ 1 ] as the recruitment or movement of people aged younger than 18 for the purposes of exploitation, and included international and domestic trafficking. Trafficking terms such as “trafficked” “domestic servitude” and “sexual exploitation” were used to search clinical notes and correspondence of children who had accessed care within SLaM since 1 January 2006–21 November 2014 (search upper date limit; see full list of search terms in S1 File ). Records that included one or more trafficking terms were screened for eligibility. Inclusion criteria for the trafficking group were met if clinical records suggested a child’s care team believed they had been trafficked, either based on information consistent with the definition of human trafficking given directly by the child, or because of access to third party information (e.g. ongoing police or social services investigation of allegations the child had been trafficked). Cases where trafficking was suspected but not confirmed during the course of contact with services were included in order to arrive at as comprehensive a sample as possible. Cases where trafficking exposure was unclear were resolved by consensus with reference to a second reviewer. Due to the limitations of clinical data we were unable to reliably assess whether all children were free from their traffickers while in contact with SLaM services (i.e. having escaped or been rescued from or having been abandoned by their traffickers) or whether some children were in contact with or returned to their traffickers during or after accessing mental healthcare.

The control group consisted of SLaM service users matched to cases for primary diagnosis, gender, age (+/- 1 year), type of initial care (inpatient or outpatient), and year of most recent service contact. The matched cohort was selected using a computer-generated random sample from all potential controls that met the matching criteria for each case, aiming for a case—control ratio of 1:4.

All data were collected as part of routine assessment and treatment of individuals in contact with SLaM services. Data were extracted from structured fields (e.g. dates, outcome scores) and by targeted searches of free-text clinical notes and correspondence using keywords and wildcards, which allowed searching for terms anywhere within a phrase.

Socio-demographic characteristics