Feature Writing

Ai generator.

“ Feature Writing is a creative form of journalism that focuses on engaging storytelling, providing relevant information, and offering a unique perspective to captivate readers. It involves crafting compelling narratives with clarity, coherence, and a strong narrative structure, while tailoring content to the target audience’s interests and preferences.”

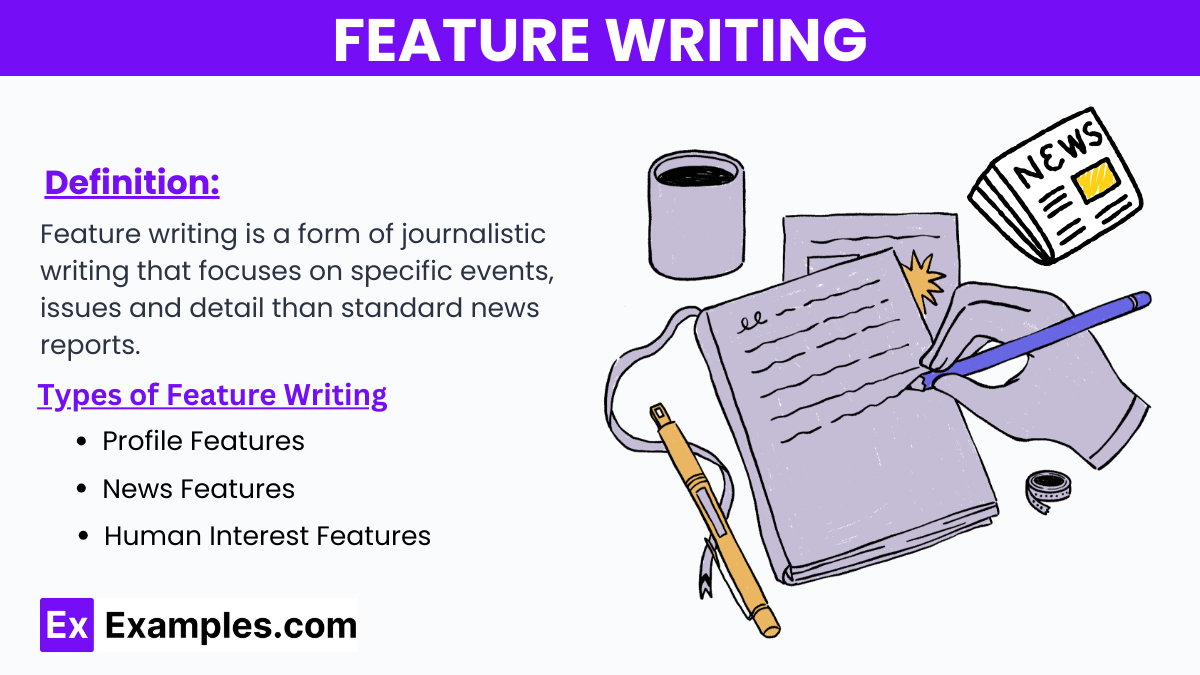

What is Feature Writing?

Feature writing is a form of journalistic writing that focuses on specific events, issues, or people, providing more depth and detail than standard news reports. Unlike hard news stories, which primarily deal with the facts of who, what, when, and where, feature articles explore the how and why. They offer readers insight into the context and background of a subject, often emphasizing a narrative style. Feature articles are commonly found in magazines, newspapers, and online platforms, where there’s more space for exploration and stylistic flair.

Characteristics of Feature Writing

Feature articles are distinguished by several key characteristics:

- In-depth Exploration : Feature articles provide a deeper understanding of the topic, whether it’s a person, place, event, or issue. They go beyond mere facts to include the background, context, and in-depth details that paint a fuller picture.

- Narrative Style : Features often employ storytelling techniques, such as narratives and scenes, making them more engaging and relatable. They might follow a structured plot with a clear beginning, middle, and end, drawing the reader into the story.

- Emotional Engagement : These pieces frequently aim to evoke emotions, connecting the audience with the subject matter on a personal level. Whether it’s excitement, sympathy, or curiosity, the emotional pull is a crucial element.

- Subject Variety : The topics can range widely, from profiles of influential people, in-depth analysis of a social trend, descriptive accounts of events, or explorative pieces on cultural phenomena.

- Attention to Detail : Feature writers pay close attention to details, often using descriptive language that helps the reader visualize the setting and understand the characters involved in the story.

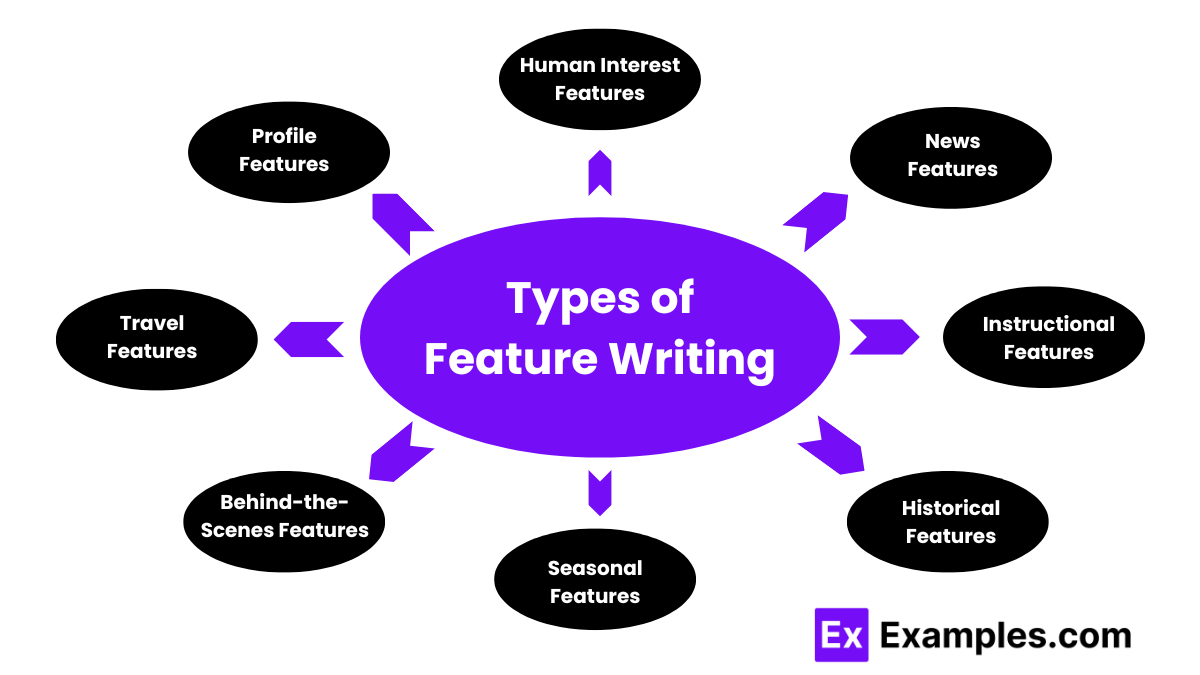

Different Types of Feature Writing

Feature writing encompasses various styles and forms, each tailored to deliver content in a unique and engaging manner. Here’s an overview of some common types of feature writing that cater to diverse reader interests and preferences:

1.Profile Features

- Profile features are intimate portraits of individuals, providing insight into their lives, careers, and personalities. These features often include interviews and observations and aim to reveal the character’s impact, motivations, and personal stories.

- Examples : A day in the life of a renowned chef. Profile of an up-and-coming athlete.

2.Human Interest Features

- Human interest stories focus on the emotional or sentimental side of events or individuals, aiming to connect with the reader on a personal level. These stories often highlight personal achievements, struggles, or unusual experiences.

- Examples : The journey of someone who has overcome a significant challenge, such as a major illness or adversity. The impact of a community project on the lives of local residents.

3.News Features

- News features provide background and context to current news stories, offering deeper insights than standard news reports. They delve into the “how” and “why,” giving readers a broader understanding of the significance and implications of the news.

- Examples : The effects of a new government policy on small businesses. Behind-the-scenes look at a major international summit.

4.Instructional Features

- Instructional features aim to educate and inform by providing step-by-step guidance on various processes or activities. These articles are practical and direct, helping readers understand complex tasks or learn new skills.

- Examples : How to start a vegetable garden in your backyard. Tips and tricks for mastering digital photography.

5.Historical Features

- These features explore significant events from the past, offering insights into their impact on the present. They draw connections between past and current events, providing a historical perspective that enriches understanding.

- Examples : The evolution of civil rights in America. A retrospective on the technology boom of the late 20th century.

6.Seasonal Features

- Seasonal features are timely pieces that relate to events, holidays, or phenomena specific to a particular time of year. They are relevant and engaging due to their immediate connection to the season or occasion.

- Best summer festivals in the United States. Winter holiday traditions around the world.

7.Behind-the-Scenes Features

- These articles provide a glimpse into places, processes, or events that the average person might not have access to, offering a backstage view of different worlds.

- Examples : Inside a top Michelin-starred restaurant’s kitchen. The preparation and execution of a major fashion show.

What is the Difference Between a News Story and a Feature Story?

Feature writing in journalism.

Feature writing in journalism occupies a unique space that combines in-depth reporting with creative storytelling. It serves to illuminate the broader contexts, delve into personal stories, and examine the implications of events and trends. Unlike hard news, which delivers the immediate facts of an event or issue, feature writing explores themes and ideas at a deeper level, engaging the reader with a mix of factual reporting and narrative techniques.

The Role of Feature Writing

Feature writing enhances journalistic endeavors by providing:

- Depth and Context : Features dig deeper than the basic facts, offering readers a comprehensive view of the topic.

- Human Element : By focusing on personal stories and experiences, features highlight the human impact of broader events and issues.

- Engagement and Retention : The narrative style of features draws readers in and keeps them engaged, increasing reader retention and involvement.

Challenges in Feature Writing

While feature writing is rewarding, it presents challenges such as:

- Time Consumption : Due to the depth of research and writing required, features take longer to produce than standard news stories.

- Balancing Facts and Style : Writers must ensure that their creative storytelling does not overshadow the factual accuracy of the reporting.

- Emotional Involvement : Maintaining objectivity can be challenging when dealing with stories that evoke strong emotions.

Feature Writing Examples

- Profile of a Local Hero : Exploring the life and impact of a firefighter who saved lives during a recent catastrophic event.

- Behind-the-Scenes at a Bakery : A day in the life of a master baker who crafts artisan breads at a popular local bakery.

- Reviving the Art of Handwritten Letters : A feature on communities and individuals who are bringing back the tradition of handwritten correspondence.

- The Rise of Urban Gardening : How city dwellers are transforming their rooftops and balconies into lush green spaces.

- Journey Through Traditional Music : A deep dive into the resurgence of folk music in rural Appalachia.

- The Challenge of Remote Education : Chronicling the experiences of teachers and students adapting to online learning during a global pandemic.

- The Craft of Artisanal Coffee : Following a bean from its origins in Ethiopia to a cup of coffee in a trendy urban café.

- Wildlife Conservation Efforts : Spotlighting a wildlife conservationist working to protect endangered species in Madagascar.

- Vintage Fashion Comeback : A feature on how vintage clothing is becoming mainstream and influencing contemporary fashion designers.

- Innovations in Renewable Energy : Profiling new technologies that are making solar and wind power more accessible and efficient.

Feature Writing Examples for Students

- A Day in the Life of a College President : Explore the responsibilities and daily activities of a college president, including their role in shaping educational policies and student life.

- The Science Behind Study Habits : Investigate how different study techniques affect learning outcomes, featuring insights from educational psychologists and students’ personal experiences.

- Eco-Friendly Schools : Profile a school that has implemented green initiatives, from recycling programs to solar-powered classrooms, and the impact on the school community.

- Student Entrepreneurs : Highlight students who have started their own businesses while managing school responsibilities, focusing on their challenges and successes.

- The Evolution of School Lunches : A look at how school cafeterias are transforming meals to be healthier and more appealing to students across various regions.

- Technology in the Classroom : Feature the integration of technology in education, showcasing specific tools and apps that enhance learning and student engagement.

- Arts in Education : Delve into the importance of arts programs in schools by profiling a successful school band, theater group, or art class and exploring the benefits of artistic expression.

- Sports and Teamwork : Follow a school sports team through a season, emphasizing how sports foster skills like teamwork, discipline, and resilience.

- Study Abroad Experiences : Share stories from students who have studied abroad, focusing on the cultural and educational impacts of their experiences.

- Impact of Mentorship Programs : Examine a mentorship program within a school or community, highlighting the relationships between mentors and mentees and the program’s influence on personal and academic growth.

Tips for Features

- Choose an Interesting Topic Select a subject that not only interests you but will also captivate your readers. It could be a person, an event, or a trend that offers rich details and a compelling story.

- Do Thorough Research Gather as much information as possible. This includes background research, interviews with experts or key personalities, and firsthand observations. The more detailed and accurate your information, the more credible your article will be.

- Create a Strong Hook Start with a compelling introduction that grabs attention. Use an intriguing fact, a powerful quote, or a vivid scene to draw readers into the story.

- Develop a Clear Structure Organize your content logically. While news stories often use the inverted pyramid structure, feature articles can follow a more narrative style. Plan out your beginning, middle, and end to ensure a smooth flow of information and story.

- Use Descriptive Language Employ vivid descriptions to bring your scenes to life. Let your readers visualize the settings and understand the emotions of the characters involved. Use sensory details to enhance the storytelling.

- Include Direct Quotes Incorporate quotes from your interviews to add authenticity and depth. Quotes can provide personal insights and highlight the human aspect of your story.

- Show, Don’t Tell Instead of merely telling readers about the situation, show it through details, actions, and words. This technique helps in creating a more immersive reading experience.

- Keep the Tone Appropriate Match the tone of your writing to the subject of your feature. A light-hearted topic can have a playful tone, while more serious subjects might require a formal approach.

- Edit and Revise Once your first draft is complete, revise it for clarity, accuracy, and engagement. Editing is crucial to ensure that the narrative flows well and is free of grammatical errors.

- Seek Feedback Before finalizing your article, get feedback from peers or mentors. Fresh eyes can offer valuable insights and suggest improvements that might have been overlooked.

Style and Objective of Feature Writing

Objective of feature writing.

The primary objectives of feature writing include:

- Educating and Informing : While a feature article provides in-depth coverage of a topic, it also educates the reader by offering thorough background information, explaining the complexities, and presenting multiple perspectives.

- Engaging and Entertaining : Through narrative techniques, features aim to hold the reader’s interest with a well-told story, potentially including elements of drama, humor, and emotional appeal.

- Providing Insight : Features often go beyond the surface of news facts to explore the underlying issues or personal stories, offering readers a deeper understanding of the subject matter.

- Evoking Empathy : By focusing on human interest elements, features can evoke empathy and a personal connection, helping readers to see issues from the perspectives of others.

- Inspiring Change : Many features aim to inspire action or change by highlighting stories of personal achievement, innovation, or community development.

Style of Feature Writing

Feature writing allows for a range of stylistic expressions that can vary greatly depending on the topic and the intended audience. Some key stylistic elements include:

- Narrative Flow : Unlike the inverted pyramid structure of hard news, features often follow a narrative arc that introduces characters, builds up a storyline, and concludes with a resolution or reflection, much like a short story.

- Descriptive Detail : Features frequently use descriptive language to create vivid imagery and bring stories to life. This involves detailed descriptions of people, places, and events that engage the senses of the reader.

- Personal Voice : Feature writers may inject their own voice and style into the article, offering personal insights or drawn conclusions, which is less common in traditional news writing.

- Direct Quotes and Dialogue : Incorporating direct quotes and dialogues enriches the authenticity of the piece, providing personal viewpoints and adding a dynamic layer to the storytelling.

- Emotional Depth : The use of emotional elements, whether through the exploration of joy, struggle, or triumph, helps to connect deeply with the reader, making the story memorable and impactful.

FAQ’s

What is the rule for feature writing.

The rule for feature writing is to engage readers with compelling storytelling, relevant information, and a unique angle, all while maintaining clarity, coherence, and a strong narrative structure.

What skills are essential for feature writing?

Essential skills for feature writing include strong research and interviewing techniques, excellent storytelling abilities, the capability to evoke imagery and emotions through words, and the skill to craft well-structured narratives that keep readers engaged from start to finish.

How important are sources in feature writing?

Sources are incredibly important in feature writing as they lend credibility and depth to the narrative. Interviews with direct stakeholders, experts, and eyewitnesses provide the foundational facts and diverse perspectives that enrich the storytelling and factual basis of the feature.

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

10 Examples of Public speaking

20 Examples of Gas lighting

The Enlightened Mindset

Exploring the World of Knowledge and Understanding

Welcome to the world's first fully AI generated website!

Feature Writing: What It Is and How to Do It Right

By Happy Sharer

Introduction

Feature writing is a form of journalism that focuses on telling stories in depth. It is used to inform readers about interesting topics and give them a deeper understanding of events and people. Feature writing combines elements of storytelling, research, and interviews to create compelling articles that engage readers and allow them to explore a topic in greater detail. This article will discuss what feature writing is, why it is important, and how to craft successful feature pieces.

Exploring the Definition and Benefits of Feature Writing

Before jumping into how to write a feature article, let’s first take a look at what feature writing actually is. A feature article is a longer piece of writing than a news article, typically between 800 and 1,500 words. Unlike a news article, which is intended to report facts quickly, a feature article dives deep into a topic and provides more detailed information. Feature articles often have a narrative arc, with a beginning, middle, and end. They can be about anything from a person or event to a trend or issue.

Feature articles are different from opinion pieces, as they are not intended to push a particular point of view or agenda. Instead, they are meant to provide an unbiased exploration of a topic. Feature writing also differs from creative writing, as it is based on facts and research rather than imagination. However, feature writers still utilize their creativity when crafting stories, as they must choose which facts to highlight and how to structure the narrative.

So why should you write feature articles? Feature writing can be an effective way to engage readers and build relationships with them. Through feature writing, you can give readers an in-depth look at a topic and help them understand it better. Feature writing also allows you to showcase your writing skills and connect with readers on an emotional level. By creating stories that are both informative and entertaining, you can make a lasting impression on your audience.

A Guide to Crafting Feature Articles

Now that you know what feature writing is and why it is important, let’s take a look at how to write a successful feature article. The first step is to find an interesting topic to write about. Think about issues or stories that you find intriguing, and brainstorm ideas for potential feature pieces. You can also look at current events and trends, as these can be great sources of inspiration.

Once you have chosen a topic, it is time to do some research. Read up on the subject and gather relevant information from reliable sources. Take notes as you go, and look for quotes or other material that you can use in your article. If possible, try to conduct interviews with experts or people involved in the story, as this can add valuable insight to your article.

Once you have gathered all the necessary information, you can begin outlining your feature article. Start by deciding on a structure for your story, such as chronological order or a comparison between two sides of an issue. Then, create a list of points that you want to include in your article. This will help you stay focused and organized while writing.

Finally, it is time to start writing your feature article. Make sure to craft an engaging introduction that will draw readers in and set the tone for your story. As you write, keep in mind the structure you outlined and make sure to include all the important points. Use vivid language to make your article come alive, and don’t forget to proofread your work carefully before submitting it.

Feature Writing: What is it and How to Do It Right

Once you have a basic understanding of what feature writing is and how to craft feature articles, it is time to learn more about the art of feature writing. When writing feature stories, it is important to remember that each one is unique. No two stories will be the same, and there is no “right” way to write a feature article.

When structuring a feature story, think about how you can present the information in an interesting and engaging way. Consider using different formats, such as a Q&A or a timeline, to break up the text and make it easier to read. Also, try to avoid clichés and overused phrases, as these can make your article seem dull and uninteresting.

Interviews are an important part of feature writing, so it is important to ask the right questions. Make sure to prepare ahead of time and come up with thoughtful questions that will elicit meaningful responses. And don’t forget to ask follow-up questions, as this can help you get even more insightful answers.

In addition to structure and interviews, your writing style is also important. Feature writing should be written in an accessible and engaging style. Avoid jargon and technical terms, and focus on creating an inviting and conversational tone. Also, make sure to include vivid details and descriptions to bring your story to life.

Understanding the Art of Feature Writing

Feature writing is an art, and it takes practice to master. To become a successful feature writer, it is important to understand the different types of feature writing and how to use them effectively. There are three main types of feature writing: human interest stories, investigative pieces, and profiles. Human interest stories focus on people and their lives, while investigative pieces delve into specific issues and uncover new information. Profiles are biographical stories that explore a person’s life and accomplishments.

Visuals can also be an important part of feature writing. Photos, videos, and illustrations can help bring your story to life and help readers connect with it. However, it is important to make sure that any visuals you use are relevant and high quality. Low-quality images can take away from the impact of your article.

Finally, it is important to create an engaging voice for your feature pieces. Think about how you can make your writing stand out and draw readers in. Consider using humor, wordplay, and other techniques to make your article more memorable. Also, make sure to keep your readers in mind and tailor your writing to their interests and needs.

The Power of Feature Writing for Journalists and Writers

Feature writing has the power to engage readers and spark social change. Stories about real people and issues can inspire readers to take action and make a difference. Feature writing can also be used as a platform for reporting on injustices and raising awareness about important issues.

There are many examples of feature writing that have had a powerful impact. One example is the Pulitzer Prize-winning series “Angels in America” by Washington Post reporter Gene Weingarten. The series explored the struggles of a family living with AIDS in the 1980s, and it helped change public perception and attitudes towards the disease.

Another example of impactful feature writing is the New York Times’ “Modern Love” column. The column publishes personal essays about love and relationships, and it has become a popular destination for readers looking for advice and comfort. By sharing intimate stories, the column has created an online community and sparked conversations about love and relationships.

Feature writing is a powerful tool for journalists and writers who want to engage readers and tell compelling stories. Feature writing combines elements of storytelling, research, and interviews to create in-depth articles that explore a topic in detail. It is important to keep in mind the different types of feature writing and how to structure a feature story when crafting a feature article. Additionally, visuals and an engaging voice can help make your article even more impactful. Feature writing has the power to inform readers and spark social change, and it is an important skill for any journalist or writer.

(Note: Is this article not meeting your expectations? Do you have knowledge or insights to share? Unlock new opportunities and expand your reach by joining our authors team. Click Registration to join us and share your expertise with our readers.)

Hi, I'm Happy Sharer and I love sharing interesting and useful knowledge with others. I have a passion for learning and enjoy explaining complex concepts in a simple way.

Related Post

Unlocking creativity: a guide to making creative content for instagram, embracing the future: the revolutionary impact of digital health innovation, the comprehensive guide to leadership consulting: enhancing organizational performance and growth, leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Expert Guide: Removing Gel Nail Polish at Home Safely

Trading crypto in bull and bear markets: a comprehensive examination of the differences, making croatia travel arrangements, make their day extra special: celebrate with a customized cake.

- APPLY ONLINE

- APPOINTMENT

- PRESS & MEDIA

- STUDENT LOGIN

- 09811014536

}}/assets/Images/paytm.jpg)

How to Write a Feature Article: A Step-by-Step Guide

Feature stories are one of the most crucial forms of writing these days, we can find feature articles and examples in many news websites, blog websites, etc. While writing a feature article a lot of things should be kept in mind as well. Feature stories are a powerful form of journalism, allowing writers to delve deeper into subjects and explore the human element behind the headlines. Whether you’re a budding journalist or an aspiring storyteller, mastering the art of feature story writing is essential for engaging your readers and conveying meaningful narratives. In this blog, you’ll find the process of writing a feature article, feature article writing tips, feature article elements, etc. The process of writing a compelling feature story, offering valuable tips, real-world examples, and a solid structure to help you craft stories that captivate and resonate with your audience.

Read Also: Top 5 Strategies for Long-Term Success in Journalism Careers

Table of Contents

Understanding the Essence of a Feature Story

Before we dive into the practical aspects, let’s clarify what a feature story is and what sets it apart from news reporting. While news articles focus on delivering facts and information concisely, feature stories are all about storytelling. They go beyond the “who, what, when, where, and why” to explore the “how” and “why” in depth. Feature stories aim to engage readers emotionally, making them care about the subject, and often, they offer a unique perspective or angle on a topic.

Tips and tricks for writing a Feature article

In the beginning, many people can find difficulty in writing a feature, but here we have especially discussed some special tips and tricks for writing a feature article. So here are some Feature article writing tips and tricks: –

Do you want free career counseling?

Ignite Your Ambitions- Seize the Opportunity for a Free Career Counseling Session.

- 30+ Years in Education

- 250+ Faculties

- 30K+ Alumni Network

- 10th in World Ranking

- 1000+ Celebrity

- 120+ Countries Students Enrolled

Read Also: How Fact Checking Is Strengthening Trust In News Reporting

1. Choose an Interesting Angle:

The first step in feature story writing is selecting a unique and compelling angle or theme for your story. Look for an aspect of the topic that hasn’t been explored widely, or find a fresh perspective that can pique readers’ curiosity.

2. Conduct Thorough Research:

Solid research is the foundation of any feature story. Dive deep into your subject matter, interview relevant sources, and gather as much information as possible. Understand your subject inside out to present a comprehensive and accurate portrayal.

3. Humanize Your Story:

Feature stories often revolve around people, their experiences, and their emotions. Humanize your narrative by introducing relatable characters and sharing their stories, struggles, and triumphs.

4. Create a Strong Lead:

Your opening paragraph, or lead, should be attention-grabbing and set the tone for the entire story. Engage your readers from the start with an anecdote, a thought-provoking question, or a vivid description.

5. Structure Your Story:

Feature stories typically follow a narrative structure with a beginning, middle, and end. The beginning introduces the topic and engages the reader, the middle explores the depth of the subject, and the end provides closure or leaves readers with something to ponder.

6. Use Descriptive Language:

Paint a vivid picture with your words. Utilize descriptive language and sensory details to transport your readers into the world you’re depicting.

7. Incorporate Quotes and Anecdotes:

Quotes from interviews and anecdotes from your research can breathe life into your story. They add authenticity and provide insights from real people.

8. Engage Emotionally:

Feature stories should evoke emotions. Whether it’s empathy, curiosity, joy, or sadness, aim to connect with your readers on a personal level.

Read Also: The Ever-Evolving World Of Journalism: Unveiling Truths and Shaping Perspectives

Examples of Feature Stories

Here we are describing some of the feature articles examples which are as follows:-

“Finding Beauty Amidst Chaos: The Life of a Street Artist”

This feature story delves into the world of a street artist who uses urban decay as his canvas, turning neglected spaces into works of art. It explores his journey, motivations, and the impact of his art on the community.

“The Healing Power of Music: A Veteran’s Journey to Recovery”

This story follows a military veteran battling post-traumatic stress disorder and how his passion for music became a lifeline for healing. It intertwines personal anecdotes, interviews, and the therapeutic role of music.

“Wildlife Conservation Heroes: Rescuing Endangered Species, One Baby Animal at a Time”

In this feature story, readers are introduced to a group of dedicated individuals working tirelessly to rescue and rehabilitate endangered baby animals. It showcases their passion, challenges, and heartwarming success stories.

What should be the feature a Feature article structure?

Read Also: What is The Difference Between A Journalist and A Reporter?

Structure of a Feature Story

A well-structured feature story typically follows this format:

Headline: A catchy and concise title that captures the essence of the story. This is always written at the top of the story.

Lead: A captivating opening paragraph that hooks the reader. The first 3 sentences of any story that explains 5sW & 1H are known as lead.

Introduction : Provides context and introduces the subject. Lead is also a part of the introduction itself.

Body : The main narrative section that explores the topic in depth, including interviews, anecdotes, and background information.

Conclusion: Wraps up the story, offers insights, or leaves the reader with something to ponder.

Additional Information: This may include additional resources, author information, or references.

Read Also: Benefits and Jobs After a MAJMC Degree

Writing a feature article is a blend of journalistic skills and storytelling artistry. By choosing a compelling angle, conducting thorough research, and structuring your story effectively, you can create feature stories that captivate and resonate with your readers. AAFT also provides many courses related to journalism and mass communication which grooms a person to write new articles, and news and learn new skills as well. Remember that practice is key to honing your feature story writing skills, so don’t be discouraged if it takes time to perfect your craft. With dedication and creativity, you’ll be able to craft feature stories that leave a lasting impact on your audience.

What are the characteristics of a good feature article?

A good feature article is well-written, engaging, and informative. It should tell a story that is interesting to the reader and that sheds light on an important issue.

Why is it important to write feature articles?

Feature articles can inform and entertain readers. They can also help to shed light on important issues and to promote understanding and empathy.

What are the challenges of writing a feature article?

The challenges of writing a feature article can vary depending on the topic and the audience. However, some common challenges include finding a good angle for the story, gathering accurate information, and writing in a clear and concise style.

Aaditya Kanchan is a skilled Content Writer and Digital Marketer with experience of 5+ years and a focus on diverse subjects and content like Journalism, Digital Marketing, Law and sports etc. He also has a special interest in photography, videography, and retention marketing. Aaditya writes in simple language where complex information can be delivered to the audience in a creative way.

- Feature Article Writing Tips

- How to Write a Feature Article

- Step-by-Step Guide

- Write a Feature Article

Related Articles

Is Citizen Journalism the Future of News?

Adapting to a Changing Media Landscape 2024

The Impact of Commercial Radio & Scope of Radio Industry in India

The Different Types of News in Journalism: What You Need to Know

Enquire now.

- Advertising, PR & Events

- Animation & Multimedia

- Data Science

- Digital Marketing

- Fashion & Design

- Health and Wellness

- Hospitality and Tourism

- Industry Visit

- Infrastructure

- Mass Communication

- Performing Arts

- Photography

- Student Speak

- 5 Reasons Why Our Fashion Design Course Will Set You Apart May 10, 2024

- Nutrition & Dietetics Course After 12th: Courses Details, Eligibility, and Fee 2024 May 9, 2024

- Fashion Design Courses After 12th: Course Details, Fee, and Eligibility 2024 May 4, 2024

- Film Making Courses After 12th: Course Details, Fees, and Eligibility 2024 May 3, 2024

- The Wellness Wave: Trends in Nutrition and Dietetics Training 2024 April 27, 2024

- Sustainable and Stylish: Incorporating Eco-Friendly Practices in Interior Design Courses April 25, 2024

- Why a Fine Arts Degree is More Than Just Painting Pictures April 24, 2024

- Beyond the Lines: Exploring Creativity and Expression in Fine Arts April 24, 2024

- How Music Classes Can Help You Achieve Your Musical Goals April 23, 2024

- How Artificial Intelligence is Reshaping Animation Production? April 22, 2024

}}/assets/Images/about-us/whatsaap-img-1.jpg)

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Article Writing

How to Write a Feature Article

Last Updated: March 11, 2024 Approved

This article was co-authored by Mary Erickson, PhD . Mary Erickson is a Visiting Assistant Professor at Western Washington University. Mary received her PhD in Communication and Society from the University of Oregon in 2011. She is a member of the Modern Language Association, the National Communication Association, and the Society for Cinema and Media Studies. There are 7 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. wikiHow marks an article as reader-approved once it receives enough positive feedback. This article has 41 testimonials from our readers, earning it our reader-approved status. This article has been viewed 1,461,226 times.

Writing a feature article involves using creativity and research to give a detailed and interesting take on a subject. These types of articles are different from typical news stories in that they often are written in a different style and give much more details and description rather than only stating objective facts. This gives the reader a chance to more fully understand some interesting part of the article's subject. While writing a feature article takes lots of planning, research, and work, doing it well is a great way to creatively write about a topic you are passionate about and is a perfect chance to explore different ways to write.

Choosing a Topic

- Human Interest : Many feature stories focus on an issue as it impacts people. They often focus on one person or a group of people.

- Profile : This feature type focuses on a specific individual’s character or lifestyle. This type is intended to help the reader feel like they’ve gotten a window into someone’s life. Often, these features are written about celebrities or other public figures.

- Instructional : How-to feature articles teach readers how to do something. Oftentimes, the writer will write about their own journey to learn a task, such as how to make a wedding cake.

- Historical : Features that honor historical events or developments are quite common. They are also useful in juxtaposing the past and the present, helping to root the reader in a shared history.

- Seasonal : Some features are perfect for writing about in certain times of year, such as the beginning of summer vacation or at the winter holidays.

- Behind the Scenes : These features give readers insight into an unusual process, issue or event. It can introduce them to something that is typically not open to the public or publicized.

Interviewing Subjects

- Schedule about 30-45 minutes with this person. Be respectful of their time and don’t take up their whole day. Be sure to confirm the date and time a couple of days ahead of the scheduled interview to make sure the time still works for the interviewee.

- If your interviewee needs to reschedule, be flexible. Remember, they are being generous with their time and allowing you to talk with them, so be generous with your responses as well. Never make an interviewee feel guilty about needing to reschedule.

- If you want to observe them doing a job, ask if they can bring you to their workplace. Asking if your interviewee will teach you a short lesson about what they do can also be excellent, as it will give you some knowledge of the experience to use when you write.

- Be sure to ask your interviewee if it’s okay to audio-record the interview. If you plan to use the audio for any purpose other than for your own purposes writing up the article (such as a podcast that might accompany the feature article), you must tell them and get their consent.

- Don't pressure the interviewee if they decline audio recording.

- Another good option is a question that begins Tell me about a time when.... This allows the interviewee to tell you the story that's important to them, and can often produce rich information for your article.

Preparing to Write the Article

- Start by describing a dramatic moment and then uncover the history that led up to that moment.

- Use a story-within-a-story format, which relies on a narrator to tell the story of someone else.

- Start the story with an ordinary moment and trace how the story became unusual.

- Check with your editor to see how long they would like your article to be.

- Consider what you absolutely must have in the story and what can be cut. If you are writing a 500-word article, for example, you will likely need to be very selective about what you include, whereas you have a lot more space to write in a 2,500 word article.

Writing the Article

- Start with an interesting fact, a quote, or an anecdote for a good hook.

- Your opening paragraph should only be about 2-3 sentences.

- Be flexible, however. Sometimes when you write, the flow makes sense in a way that is different from your outline. Be ready to change the direction of your piece if it seems to read better that way.

Finalizing the Article

- You can choose to incorporate or not incorporate their suggestions.

- Consult "The Associated Press Stylebook" for style guidelines, such as how to format numbers, dates, street names, and so on. [7] X Research source

- If you want to convey slightly more information, write a sub-headline, which is a secondary sentence that builds on the headline.

How Do You Come Up With an Interesting Angle For an Article?

Sample Feature Article

Community Q&A

- Ask to see a proof of your article before it gets published. This is a chance for you to give one final review of the article and double-check details for accuracy. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Be sure to represent your subjects fairly and accurately. Feature articles can be problematic if they are telling only one side of a story. If your interviewee makes claims against a person or company, make sure you talk with that person or company. If you print claims against someone, even if it’s your interviewee, you might risk being sued for defamation. [9] X Research source Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

You Might Also Like

- ↑ http://morrisjournalismacademy.com/how-to-write-a-feature-article/

- ↑ https://www.nytimes.com/learning/students/writing/voices.html

- ↑ http://careers.bmj.com/careers/advice/view-article.html?id=20007483

- ↑ http://faculty.washington.edu/heagerty/Courses/b572/public/StrunkWhite.pdf

- ↑ https://www.apstylebook.com/

- ↑ http://www.entrepreneur.com/article/166662

- ↑ http://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/libel-vs-slander-different-types-defamation.html

About This Article

To write a feature article, start with a 2-3 sentence paragraph that draws your reader into the story. The second paragraph needs to explain why the story is important so the reader keeps reading, and the rest of the piece needs to follow your outline so you can make sure everything flows together how you intended. Try to avoid excessive quotes, complex language, and opinion, and instead focus on appealing to the reader’s senses so they can immerse themselves in the story. Read on for advice from our Communications reviewer on how to conduct an interview! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Kiovani Shepard

Nov 8, 2016

Did this article help you?

Sky Lannister

Apr 28, 2017

Emily Lockset

Jun 26, 2017

Christian Villanueva

May 30, 2018

Richelle Mendoza

Aug 26, 2019

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Develop the tech skills you need for work and life

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

4 Types of Features

From profiles to travel stories, there is feature style for everyone

“If my doctor told me I had only six minutes to live, I wouldn’t brood. I’d type a little faster.” Isaac Asimov

Truth be told, no one writes a plain, old feature article, since “feature” is an umbrella term that encompasses a broad range of article types, from profiles to how-tos and beyond.

The goal here is not just to know these types exist but rather to use them to shape your material into a format that best serves your reader and the publication for which you are writing. Pitching a story that takes a particular format or angle also helps editors see the focus and appeal of your idea more clearly, which can help you get hired.

Let’s take a look at some of the most common feature article types.

A profile is a mini-biography on a single entity — person, place, event, thing — but it revolves around a nut graph that includes something newsworthy happening now. That “hook,” as we call the news focus, must be evident throughout the story.

A profile on Jennifer Lawrence might be interesting, but it is most likely to be published about the time she has a new movie coming out or she wins an award.

This fulfills the readers’ desire to know why they are reading about someone at a given time or in a given magazine.

The best profiles examine characters and document struggles and dreams. It’s important that you show a complete picture of who or what is being profiled — warts and all — especially since the controversy is often what keeps people reading. Controversy, however, is not the only compelling aspect of profiles. They are, most importantly, personal and insightful, beyond the pedantic list of accomplishments you can get from a bio sheet or a PR campaign.

Profiles aim to:

- Reveal feelings

- Expose attitudes

- Capture habits and mannerisms.

- Entertain and inform.

Accomplishing those goals is what makes profiles challenging to write, but also makes them among the most compelling and fulfilling stories to create.

Delving deeply into your subject’s interests, career, education and family can bring out amazing anecdotes, as can reporting in an immersive style.

The goal is to watch your subject closely and document his or her habits, mannerisms, vocal tones, dress, interactions and word choice. Describing these elements for readers can contribute to a fuller and more accurate presentation of the interview subject.

Consider this opening paragraph from one of my favorite profiles, Jeff Perlman’s look at one-time baseball bad boy John Rocker of the Atlanta Braves:

A MINIVAN is rolling slowly down Atlanta’s Route 400, and John Rocker, driving directly behind it in his blue Chevy Tahoe, is pissed. “Stupid bitch! Learn to f—ing drive!” he yells. Rocker honks his horn. Once. Twice. He swerves a lane to the left. There is a toll booth with a tariff of 50 cents. Rocker tosses in two quarters. The gate doesn’t rise. He tosses in another quarter. The gate still doesn’t rise. From behind, a horn blasts. “F— you!” Rocker yells, flashing his left middle finger out the window. Finally, after Rocker has thrown in two dimes and a nickel, the gate rises. Rocker brings up a thick wad of phlegm. Puuuh! He spits at the machine. “Hate this damn toll.”

Perlman does not have to tell us anything about Rocker; he has shown us and lets us make our own determinations as to the person we are getting to know through this article.

Research is key to any piece, but profiles provide the ultimate test of your interviewing skills. How well can you coax complete strangers into sharing details of their private lives? Your job is to get subjects to open up and share their true personalities, memories, experiences, opinions, feelings and reflections.

This comes from a true conversational style and a willingness to probe as deep as you need to get the material you need.

Interview your subject and as many people as you need to get clear perspectives of your profile subject.

Not everyone will make your article, but you can get background information and anecdotes that could be crucial to understanding your subject or asking key questions. (Now might be a good time to download “Always Get the Name of the Dog.”)

Take the time to watch your subject at work or play so you can really get to know them in a three-dimensional way.

The fewer sources and the less time you spend with your subject the less accurate or complex your profile will be.

The framework of a profile follows these guidelines:

Anecdotal lede

An engaging, revealing a little story to lure us into your article.

Nut graph/Theme

A paragraph that shows the reader what exactly this story is about and why does this entity matter now?

Observe our subject in action now using dialogue details and descriptions.

A recap of our subject’s past activities using facts, quotes and anecdotes as they relate to the theme.

Where Are We Now?

What is our subject doing now, as it relates to the theme?

What Lies Ahead?

Plans, dreams, goals and barriers to overcome.

Closing Quote

Bring the article home in a way that makes the reader feel the story is complete like they can sigh at the end of a good tale.

A Q&A article is just what it sounds like — an article structured in questions and answers.

Freelancers and editors both like them for several reasons:

- They’re easy to write.

- They’re easy to read.

- They can be used on a variety of subjects.

The catch is writers/interviewers must take even greater care with the questions asked and ensuring the quality of the answers received because they will provide both the skeleton and the meat of your piece.

This may seem obvious, but quality questions are vital, meaning we avoid closed-ended (yes or no, single-word answer) questions and instead ask questions that will inspire some thought, creativity and explanation or description.

Q&A articles start with an introduction into the subject — often as anecdotal as any other piece, but then transition into the fly-on-the-wall feeling of watching an interview take place. You are the interviewer.

The subject is the interviewee, and the reader is sitting alongside you both soaking in the experience and your relationship.

That means a Q&A has to stay conversational so it does not feel like a written interrogation.

The interview itself is much like we would use for an article, but you have to be more conscious of the order in which you ask questions, how they transition from one another and the quality of the answer so you are not tempted to move answers around.

You will be amazed at how many words get generated in an actual conversation or interview, so the Q&A is far from over when the interview concludes. Editing and cutting the interview transcript can take far longer than the interview itself.

You cannot change your subject’s words, but you take out redundancies and those verbal lubricants that keep conversations moving — “like,” “you know,” etc., Sentences and phrases can be edited out by using ellipses (…) to show you have removed something.

Grammar is a challenge with a lot of transcripts, and I will leave in that which represents the subject, but I will not let them come across badly by misusing words or phrases.

Instead, let’s take it out or ask them to clarify.

If you do an internet search on “round-up story,” you very often get a collection of information from various places on a central them.

Feature round-ups are written the same way.

These articles are like list blog posts, where you have a variety of suggestions from different sources that advance a common idea:

- 7 secrets to a happy baby

- 10 best vacation spots with a teenager

- 5 tips on how to pick the perfect roommate

You may notice that there is a numeric value on each of these ideas, and that is a key part of the roundup. You are offering a collection of suggestions, provided and supported by sources, on a specific topic.

The article begins, as most features do, with an anecdote that takes us to a theme, but instead of a uniform or chronological body style, we break it up into these sections outlined by each numbered suggestion.

Each section can be constructed like its own mini feature — complete with sources, facts, anecdote and quotes, or just the advice provided by a qualified source (not the author!).

There does not need to be a specific order to how each piece of the article is presented, rather their order is interchangeable.

It is important to have sources with some level of expertise and not merely opinions on the topic. Just because someone went to Club Med with their 5-year-old and had fun does not mean it’s the best vacation spot for kids.

We first need an idea of what makes a good vacation spot and then support with facts how this one fits the criteria.

Readers love to learn how to do new things, and there are few better ways to teach them than through how-to articles.

How-to articles provide a description of how something can be accomplished using information and advice, giving step-by-step directions, supplies and suggestions for success.

Unlike round-ups, these articles must be written sequentially and have to end with some sort of success.

Aim for something that most people don’t know how to do, or something that offers a new way of approaching a familiar task. Most importantly, make sure it is neither too simplistic, nor too complex for their attempt, and include provide definitions and anecdotes that show how things can go well or poorly in attempting this task.

Personal Experience

Most of us have had some experience that we think, “I would love to write about this so other people can learn or enjoy this with me.”

If you have a truly original and teachable moment and can find the right feature to which to pitch it, you may very well have a personal experience story on your hands.

Some guidelines for finding such a story include whether this is an experience readers would:

- Wish to share?

- Learn or benefit from?

- Wish to avoid?

- Help cope with a challenge?

Unlike a first-person lede, which might use your personal anecdote to get us into a broader story, in a personal experience article you are the story, and how we learn from your experience will help us navigate the same waters.

They can be emotional, like the New Yorker piece on women who share their abortion stories , but they can also be about amazing vacations that others might consider — “Bar Mitzvah trip to Israel” anyone? — or how about a man who quits a high-powered job to stay home with his kids?

No matter what your experience, you must be willing to tell your story with passion and objectivity, sharing the good, the bad and the uncomfortable, and making readers part of the experience.

It’s important that the experience is over before you pitch, so the reader can get a clear perspective of what happened and the resolution. Did it work or not?

As the author, you also need time to gain perspective on your issue so you can “report” it as objectively as possible.

Finally, make sure you are chronicling something attainable or achievable. We need to go through it and come out the other side with evidence that will make us smarter and better equipped to handle a similar situation that might come our way.

The Art of Covering Horse Racing

Melissa Hoppert is the racing writer from the New York Times, and despite covering the same events over and over she manages to find a unique story each time.

Belmont Park is called “Big Sandy,” because the track has so much sand on it. I rode the tractor and asked the trackman, “What makes it like that? What it’s like to race on it?”

It was my most-read story that year. You have to think outside the box.

When the horse Justify came along, it was like ”here we go again — another Triple Crown with the same trainer. What can I possibly write about Bob Baffert that has not written before?

We observed and thought outside the box. We didn’t do a Bob Baffert feature. We went to the barn and still talked to him every day, but we looked at things differently.

We focused more on the owners . They were in a partnership and that is a trend of the sport. Rich owners team up to share the risk. That made it more of a trend story. Is this where we are going.

Sometimes I like writing about the horse. American Pharoah was a really fun, quirky horse. My most favorite story was when I went to visit American Pharoah’s sire, Pioneer of the Nile , at the breeding shed. He has a weird breeding style. He needed the mood to be set. It was kind of random, but it helped tell a story of American Pharoah that had not yet been told.

True-Life Drama

Examples of these include:

- The couple on a sight-seeing plane ride that had to land the plane when their pilot died

- Aron Ralston frees himself by sawing off his own arm after getting trapped in the desert.

- Tornado survival stories

It is fitting that the first example I found to show you of true-life dramas came from Readers Digest because these types of stories are the bread and butter of that magazine.

They are the stories that are almost impossible to believe but are true, and they are driven by the characters who make them come to life.

Some “true-life dramas” become even more famous when they are adapted for the screen, like the Slate story of being rescued from Iran , you might know better as the film, “Argo.”

How about Capt. Richard Phillips’ dramatic struggle with Somali pirates, now a film starring Tom Hanks?

Steve Lopes of the Los Angeles Times found a violin-playing homeless man who became the subject of numerous columns and later the movie “The Soloist.”

These stories are, quite simply, dramatic experiences from real people, where they live through moments few of us can imagine.

Many of the feature versions of these stories start as newspaper coverage of the breaking event, and then a desire to go behind-the-scenes and chronicle exactly what happened over a much longer course of time — the lead-up, the culmination and the aftermath.

Being a consumer of news will help you come across these stories, and a desire to conduct really penetrating interviews to get the “real story” will make them come to life.

You might not be thinking about Christmas in May or back-to-school in February, but chances are editors will be scheduling those topics and looking for article ideas.

Seasonal stories are the ones that happen every year and need a fresh angle on an annual basis.

It goes beyond standbys like “Best side dishes for Thanksgiving,” and how to make a good Easter basket, to “ How to do the holidays in a newly divorced family ,” and “Back to school shopping for a home-schooled child.”

The key is that a timely observance is interwoven in the theme, and these stories are planned and often executed months in advance since we all know they are coming.

Seasonal can also relate to anniversaries — Sept. 11, Martin Luther King Jr. Day, Titanic sinking — and their marketability can escalate dramatically around an anniversary.

The angle is all about the audience, so think how you can spin one day or a milestone event to toddlers, teens, seniors, your local community, pets, business, food, travel and you may suddenly have 10 stories from one topic.

Remember, though, that your pitch has to come long before the event is even in the mind of most readers — at least six months and sometimes a year.

The perceived glamour division of freelance writing is the travel piece, which most people think comes with an all-expense-paid trip to swanky, exotic locations.

That can be true, but more likely writers make their own plans and accommodations and their pay reflects that a portion of their compensation comes from the good time they had traveling.

The good news is that with the rise of travel blogs and smaller travel publications there are more outlets than ever to pitch your ideas, provided they are original and unique to the audience.

That means, “Traveling to Paris,” probably won’t work, but “ Traveling to Paris on $50 a day ” just might.

That also does not mean that publications are looking for your personal essay on what you did for your summer vacation, or just because you visited Peru and loved it that it’s worthy of a feature article. You have to show the editor and the reader why you have a unique perspective and angle on a traveling experience.

Travel writing means looking for stories on about:

- How to travel

- When to travel

- Advice on traveling

The more specifically you can focus on a population of travelers — seniors, parents, honeymooners, first-time family vacation — the more likely you can come up with an idea that has not been overdone and pitch it to a niche magazine.

In a column on the Writer’s Digest website, Brian Klems writes the need to travel “deeply” as opposed to just widely, and I thought that was such an insightful term. He spelled out the need to really dig deep into whatever area you might cover and take copious, detailed notes, but I would add that you also have to really dig deep into what people want to know about travel and enough to go past the cliché or stereotypes.

The more descriptively you can present experiences, the more compelled readers may be to join you.

To separate yourself from the cacophony of travel voices out there, consider building up expertise in one subject or area. If you are from an interesting area, see how you can pitch stories to bring make outsiders insiders. Are you a big hockey fan? What about traveling to different hockey venues and making a weekend travel story out of what to see and do before and after the game?

The key to success is to become a curious and perceptive traveler from the minute you book a trip. Think about how your experience can be a travel story, as opposed to only looking to pitch stories that could become an experience.

Some other types to consider:

Essay or Opinion

First-person pieces, which usually revolve around an important or timely subject (if they’re to be published in a newspaper or “serious” magazine).

Historical Article

Focus on a single historical aspect of the subject but make a current connection.

Trend Story

Takes the pulse of a population right now, often in technology, fashion, arts and health.

No, we are not talking about trees.

Evergreen stories are ones that do not have an expiration date and can be pitched for creation at any time.

A profile on a new trend or profile-worthy person has to be pitched in relatively short order, or it will not really marketable anymore. But a story on how to build an exercise program around your pet does not really have to be published at a specific time.

Incorporating evergreen ideas into your repertoire of story ideas will open up even more publishing doors.

Writing Fabulous Features Copyright © 2020 by Nicole Kraft is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Follow us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

- Criminal Justice

- Environment

- Politics & Government

- Race & Gender

Expert Commentary

Feature writing: Crafting research-based stories with characters, development and a structural arc

Semester-long syllabus that teaches students how to write stories with characters, show development and follow a structural arc.

Republish this article

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License .

by The Journalist's Resource, The Journalist's Resource January 22, 2010

This <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org/home/syllabus-feature-writing/">article</a> first appeared on <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org">The Journalist's Resource</a> and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.<img src="https://journalistsresource.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cropped-jr-favicon-150x150.png" style="width:1em;height:1em;margin-left:10px;">

The best journalism engages as it informs. When articles or scripts succeed at this, they often are cast as what is known as features or contain elements of a story. This course will teach students how to write compelling feature articles, substantive non-fiction stories that look to a corner of the news and illuminate it, often in human terms.

Like news, features are built from facts. Nothing in them is made up or embellished. But in features, these facts are imbedded in or interwoven with scenes and small stories that show rather than simply tell the information that is conveyed. Features are grounded in time, in place and in characters who inhabit both. Often features are framed by the specific experiences of those who drive the news or those who are affected by it. They are no less precise than news. But they are less formal and dispassionate in their structure and delivery. This class will foster a workshop environment in which students can build appreciation and skill sets for this particular journalistic craft.

Course objective

To teach students how to interest readers in significant, research-based subjects by writing about them in the context of non-fiction stories that have characters, show development and follow a structural arc from beginning to end.

Learning objectives

- Explore the qualities of storytelling and how they differ from news.

- Build a vocabulary of storytelling.

- Apply that vocabulary to critiquing the work of top-flight journalists.

- Introduce a writing process that carries a story from concept to publication.

- Introduce tools for finding and framing interesting features.

- Sharpen skills at focusing stories along a single, clearly articulated theme.

- Evaluate the importance of backgrounding in establishing the context, focus and sources of soundly reported stories.

- Analyze the connection between strong information and strong writing.

- Evaluate the varied types of such information in feature writing.

- Introduce and practice skills of interviewing for story as well as fact.

- Explore different models and devices for structuring stories.

- Conceive, report, write and revise several types of feature stories.

- Teach the value of “listening” to the written word.

- Learn to constructively critique and be critiqued.

- Examine markets for journalism and learn how stories are sold.

Suggested reading

- The Art and Craft of Feature Writing , William Blundell, Plume, 1988 (Note: While somewhat dated, this book explicitly frames a strategy for approaching the kinds of research-based, public affairs features this course encourages.)

- Writing as Craft and Magic (second edition), Carl Sessions Stepp, 2007, Oxford University Press.

- On Writing Well (30th anniversary edition), William Zinsser, Harper Paperbacks, 2006.

- The Associated Press Stylebook 2009 , Associated Press, Basic Books, 2009.

Recommended reading

- America’s Best Newspaper Writing , edited by Roy Peter Clark and Christopher Scanlan, Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2006.

- Writing for Story , Jon Franklin, Penguin, 1986.

- Telling True Stories: A Nonfiction Writers’ Guide from the Nieman Foundation at Harvard University , edited by Mark Kramer and Wendy Call, Plume, 2007.

- The Journalist and the Murderer , Janet Malcolm, Vintage, 1990.

- Writing for Your Readers , Donald Murray, Globe Pequot, 1992.

Assignments

Students will be asked to write and report only four specific stories this semester, two shorter ones, one at the beginning of the semester and one at the end, and two longer ones, a feature looking behind or beyond a news development, and an institutional or personal profile.

They will, however, be engaged in substantial writing, much of it focused on applying aspects of the writing-process method suggested herein. Throughout the class, assignments and exercises will attempt to show how approaching writing as a process that starts with a story’s inception can lead to sharper story themes, stronger story reporting and more clearly defined story organization. As they report and then revise and redraft the semester’s two longer assignments, students will craft theme or focus statements, write memos that help the class troubleshoot reporting weaknesses, outline, build interior scenes, workshop drafts and workshop revisions. Finally, in an attempt to place at least one of their pieces in a professional publication, an important lesson in audience and outlet, the students will draft query letters.

Methodology

This course proceeds under the assumption that students learn to report and write not only through practice (which is essential), but also by deconstructing and critiquing award-winning professional work and by reading and critiquing the work of classmates.

These workshops work best when certain rules are established:

- Every student will read his or her work aloud to the class at some point during the semester. It is best that these works be distributed in advance of class.

- Every student should respond to the work honestly but constructively. It is best for students to first identify what they like best about a story and then to raise questions and suggestions.

- All work will be revised after it is workshopped.

Weekly schedule and exercises (13-week course)

We encourage faculty to assign students to read on their own at least the first 92 pages of William Zinsser’s On Writing Well before the first class. The book is something of a contemporary gold standard for clear, consistent writing and what Zinsser calls the contract between writer and reader.

The assumption for this syllabus is that the class meets twice weekly.

Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Week 5 | Week 6 | Week 7 Week 8 | Week 9 | Week 10 | Week 11 | Week 12 | Week 13

Week 1: What makes feature stories different?

Previous week | Next week | Back to top

Class 1: News reports versus stories

The words “dispassionate,” “factual” and “front-loaded” might best describe the traditional news story. It is written to convey information quickly to the hurried reader. Features, on the other hand, are structured and told so that readers engage in and experience a story — with a beginning, middle and end — even as they absorb new information. It is features that often are the stories emailed to friends or linked on their Facebook pages. Nothing provides more pleasure than a “good read” a story that goes beyond basic information to transport audiences to another place, to engage an audience in others’ lives, to coax a smile or a tear.

This class will begin with a discussion of the differences in how journalists approach both the reporting and writing of features. In news, for example, reporters quote sources. In features, they describe characters, sometimes capturing their interaction through dialogue instead of through disembodied quotes. Other differences between news and story are summarized eloquently in the essays “Writing to Inform, Writing to Engage” and “Writing with ‘Gold Coins'” on pages 302 to 304 of Clark and Scanlan’s America’s Best Newspaper Writing . These two essays will be incorporated in class discussion.

The second part of the introductory class will focus on writing as a continuum that begins with the inception of an idea. In its cover blurb, William Blundell’s book is described as “a step-by-step guide to reporting and writing as a continuous, interrelated process.”

Notes Blundell: “Before flying out the door, a reporter should consider the range of his story, its central message, the approach that appears to best fit the tale, and even the tone he should take as a storyteller.” Such forethought defines not only how a story will be reported and written but the scope of both. This discussion will emphasize that framing and focusing early allows a reporter to report less broadly and more deeply, assuring a livelier and more authoritative story.

READING (assignments always are for the next class unless otherwise noted):

- Blundell, Chapter 1

- Clark/Scanlan, “The Process of Writing and Reporting,” pages 290-294.

ASSIGNMENT:

Before journalists can capture telling details and create scenes in their feature stories, they need to get these details and scenes in their notebooks. They need, as Blundell says, to be keen observers “of the innocuous.” In reporting news, journalists generally gather specific facts and elucidating quotes from sources. Rarely, however, do they paint a picture of place, or take the time to explore the emotions, the motives and the events that led up to the news. Later this semester, students will discuss and practice interviewing for story. This first assignment is designed to make them more aware of the importance of the senses in feature reporting and, ultimately, writing.

Students should read the lead five paragraphs of Hal Lancaster’s piece on page 56 of Blundell and the lead of Blundell’s own story on page 114. They should come prepared to discuss what each reporter needed to do to cast them, paying close attention to those parts based on pure observation and those based on interviewing.

Finally, they should differentiate between those parts of the lead that likely were based on pure observation and those that required interviewing and research. This can be done in a brief memo.

Class 2: Building observational and listening skills

Writing coach Don Fry, formerly of the Poynter Institute, used the term “gold coins” to describe those shiny nuggets of information or passages within stories that keep readers reading, even through sections based on weighty material. A gold coin can be something as simple as a carefully selected detail that surprises or charms. Or it can be an interior vignette, a small story within a larger story that gives the reader a sense of place or re-engages the reader in the story’s characters.

Given the feature’s propensity to apply the craft of “showing” rather than merely “telling,” reporters need to expand their reporting skill set. They need to become keen observers and listeners, to boil down what they observe to what really matters, and to describe not for description’s sake but to move a story forward. To use all the senses to build a tight, compelling scene takes both practice and restraint. It is neither license to write a prose-poem nor to record everything that’s seen, smelled or heard. Such overwriting serves as a neon exit sign to almost any reader. Yet features that don’t take readers to what Blundell calls “street level” lack vibrancy. They recount events and measure impact in the words of experts instead of in the actions of those either affected by policy, events or discovery of those who propel it.

In this session, students will analyze and then apply the skill sets of the observer, the reporter who takes his place as a fly on the wall to record and recount the scene. First students will discuss the passive observation at the heart of the stories assigned above. Why did the writers select the details they did? Are they the right ones? Why or why not?

Then students will be asked to report for about 30 to 45 minutes, to take a perch someplace — a cafeteria, a pool hall, a skateboard park, a playground, a bus stop — where they can observe and record a small scene that they will be asked to recapture in no more than 150 to 170 words. This vignette should be written in an hour or less and either handed in by the end of class or the following day.

Four fundamental rules apply:

- The student reporters can only write what they observe or hear. They can’t ask questions. They certainly can’t make anything up.

- The students should avoid all opinion. “I” should not be part of this story, either explicitly or implicitly.

- The scene, which may record something as slight as a one-minute exchange, should waste no words. Students should choose words and details that show but to avoid words and details that show off or merely clutter.

- Reporters should bring their lens in tight. They should write, for example, not about a playground but about the jockeying between two boys on its jungle gym.

Reading: Blundell, Chapter 1, Stepp, pages 64 to 67. Students will be assigned to read one or more feature articles built on the context of recently released research or data. The story might be told from the perspective of someone who carried out the research, someone representative of its findings or someone affected by those findings. One Pulitzer Prize-winning example is Matt Richtel’s “Dismissing the Risks of a Deadly Habit,” which began a series for which The New York Times won a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting in 2010. Richtel told of the dangers of cell phones and driving through the experiences of Christopher Hill, a young Oklahoma driver with a clean record who ran a light and killed someone while talking on the phone. Dan Barry’s piece in The Times , “From an Oyster in the Gulf, a Domino Effect,” tells the story of the BP oil spill and its impact from the perspective of one oysterman, placing his livelihood into the context of those who both service and are served by his boat.

- Finish passive observational exercise (see above).

- Applying Blundell’s criteria in Chapter 1 (extrapolation, synthesis, localization and projection), students should write a short memo that establishes what relationship, if any, exists between the features they were assigned to read and the news or research developments that preceded them. They should consider whether the reporter approached the feature from a particular point of view or perspective. If so, whose? If not, how is the story structured? And what is its main theme? Finally, students should try to identify three other ways feature writers might have framed a story based on the same research.

Week 2: The crucial early stages: Conceiving and backgrounding the story

Class 1: Finding fresh ideas

In the first half of class, several students should be asked to read their observed scenes. Writing is meant to be heard, not merely read. After each student reads a piece, the student should be asked what he or she would do to make it better. Then classmates should be encouraged to make constructive suggestions. All students should be given the opportunity to revise.