The Future of Man

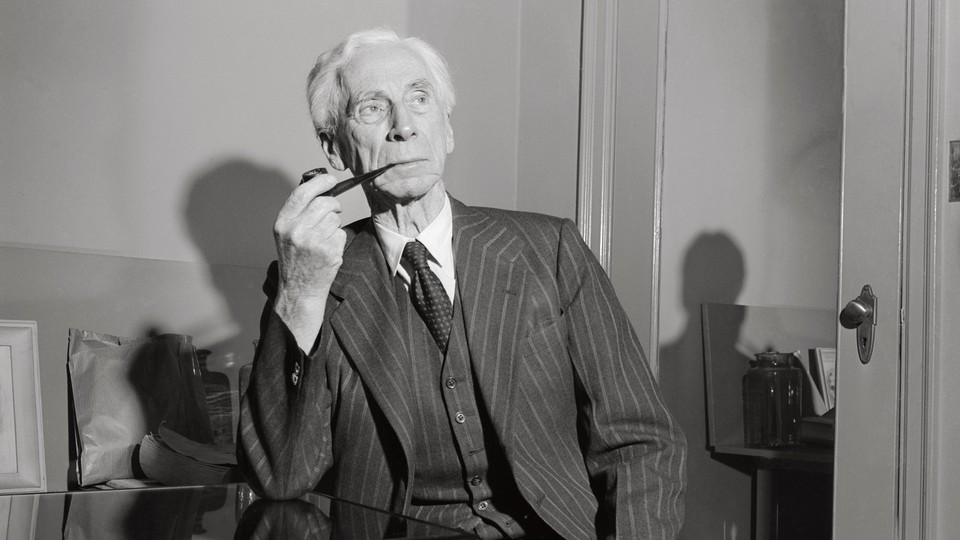

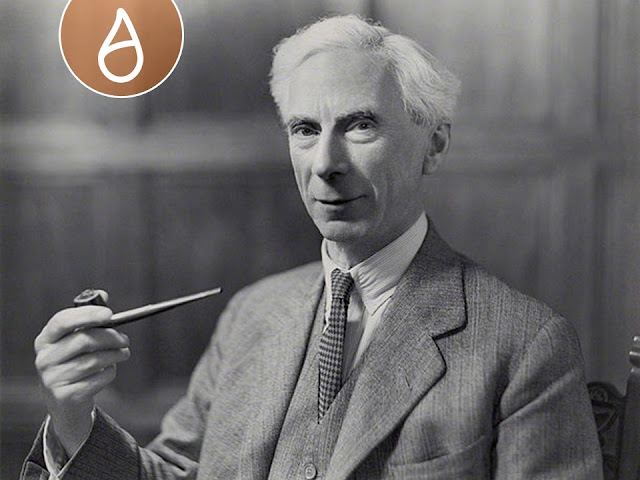

Bertrand Russell calmly examines three foreseeable possibilities for the human race.

B efore the end of the present century, unless something quite unforeseeable occurs, one of three possibilities will have been realized. These three are: —

1. The end of human life, perhaps of all life on our planet.

2. A reversion to barbarism after a catastrophic diminution of the population of the globe.

3. A unification of the world under a single government, possessing a monopoly of all the major weapons of war.

I do not pretend to know which of these will happen, or even which is the most likely. What I do contend is that the kind of system to which we have been accustomed cannot possibly continue.

The first possibility, the extinction of the human race, is not to be expected in the next world war, unless that war is postponed for a longer time than now seems probable. But if the next world war is indecisive, or if the victors are unwise, and if organized states survive it, a period of feverish technical development may be expected to follow its conclusion. With vastly more powerful means of utilizing atomic energy than those now available, it is thought by many sober men of science that radioactive clouds, drifting round the world, may disintegrate living tissue everywhere. Although the last survivor may proclaim himself universal Emperor, his reign will be brief and his subjects will all be corpses. With his death the uneasy episode of life will end, and the peaceful rocks will revolve unchanged until the sun explodes.

Perhaps a disinterested spectator would consider this the most desirable consummation, in view of man’s long record of folly and cruelty. But we who are actors in the drama, who are entangled in the net of private affections and public hopes, can hardly take this attitude with any sincerity. True, I have heard men say that they would prefer the end of man to submission to the Soviet government, and doubtless in Russia there are those who would say the same about submission to Western capitalism. But this is rhetoric with a bogus air of heroism. Although it must be regarded as unimaginative humbug, it is dangerous, because it makes men less energetic in seeking ways of avoiding the catastrophe that they pretend not to dread.

The second possibility, that of a reversion to barbarism, would leave open the likelihood of a gradual return to civilization, as after the fall of Rome. The sudden transition will, if it occurs, be infinitely painful to those who experience it, and for some centuries afterwards life will be hard and drab. But at any rate there will still be a future for mankind, and the possibility of rational hope.

I think such an outcome of a really scientific world war is by no means improbable. Imagine each side in a position to destroy the chief cities and centers of industry of the enemy; imagine an almost complete obliteration of laboratories and libraries, accompanied by a heavy casualty rate among men of science; imagine famine due to radioactive spray, and pestilence caused by bacteriological warfare: Would social cohesion survive such strains? Would not prophets tell the maddened populations that their ills were wholly due to science, and that the extermination of all educated men would bring the millennium? Extreme hopes are born of extreme misery, and in such a world hopes could only be irrational. I think the great states to which we are accustomed would break up, and the sparse survivors would revert to a primitive village economy.

The third possibility, that of the establishment of a single government for the whole world, might be realized in various ways: by the victory of the United States in the next world war, or by the victory of the U.S.S.R., or, theoretically, by agreement. Or—and I think this is the most hopeful of the issues that are in any degree probable—by an alliance of the nations that desire an international government, becoming, in the end, so strong that Russia would no longer dare to stand out. This might conceivably be achieved without another world war, but it would require courageous and imaginative statesmanship in a number of countries.

There are various arguments that are used against the project of a single government of the whole world. The commonest is that the project is utopian and impossible. Those who use this argument, like most of those who advocate a world government, are thinking of a world government brought about by agreement. I think it is plain that the mutual suspicions between Russia and the West make it futile to hope, in any near future, for any genuine agreement. Any pretended universal authority to which both sides can agree, as things stand, is bound to be a sham, like UN. Consider the difficulties that have been encountered in the much more modest project of an international control over atomic energy, to which Russia will consent only if inspection is subject to the veto, and therefore a farce. I think we should admit that a world government will have to be imposed by force.

But—many people will say—why all this talk about a world government? Wars have occurred ever since men were organized into units larger than the family, but the human race has survived. Why should it not continue to survive even if wars go on occurring from time to time? Moreover, people like war, and will feel frustrated without it. And without war there will be no adequate opportunity for heroism or self-sacrifice.

This point of view—which is that of innumerable elderly gentlemen, including the rulers of Soviet Russia—fails to take account of modern technical possibilities. I think civilization could probably survive one more world war, provided it occurs fairly soon and does not last long. But if there is no slowing up in the rate of discovery and invention, and if great wars continue to recur, the destruction to be expected, even if it fails to exterminate the human race, is pretty certain to produce the kind of reversion to a primitive social system that I spoke of a moment ago. And this will entail such an enormous diminution of population, not only by war, but by subsequent starvation and disease, that the survivors are bound to be fierce and, at least for a considerable time, destitute of the qualities required for rebuilding civilization.

Nor is it reasonable to hope that, if nothing drastic is done, wars will nevertheless not occur. They always have occurred from time to time, and obviously will break out again sooner or later unless mankind adopts some system that makes them impossible. But the only such system is a single government with a monopoly of armed force.

If things are allowed to drift, it is obvious that the bickering between Russia and the Western democracies will continue until Russia has a considerable store of atomic bombs, and that when that time comes there will be an atomic war. In such a war, even if the worst consequences are avoided, Western Europe, including Great Britain, will be virtually exterminated. If America and the U.S.S.R. survive as organized states, they will presently fight again. If one side is victorious, it will rule the world, and a unitary government of mankind will have come into existence; if not, either mankind or, at least, civilization will perish. This is what must happen if nations and their rulers are lacking in constructive vision.

When I speak of “constructive vision,” I do not mean merely the theoretical realization that a world government is desirable. More than half the American nation, according to the Gallup poll, holds this opinion. But most of its advocates think of it as something to be established by friendly negotiation, and shrink from any suggestion of the use of force. In this I think they are mistaken. I am sure that force, or the threat of force, will be necessary. I hope the threat of force may suffice, but, if not, actual force should be employed.

Assuming a monopoly of armed force established by the victory of one side in a war between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R., what sort of world will result?

In either case, it will be a world in which successful rebellion will be impossible. Although, of course, sporadic assassination will still be liable to occur, the concentration of all important weapons in the hands of the victors will make them irresistible, and there will therefore be secure peace. Even if the dominant nation is completely devoid of altruism, its leading inhabitants, at least, will achieve a very high level of material comfort, and will be freed from the tyranny of fear. They are likely, therefore, to become gradually more good-natured and less inclined to persecute. Like the Romans, they will, in the course of time, extend citizenship to the vanquished. There will then be a true world state, and it will be possible to forget that it will have owed its origin to conquest. Which of us, during the reign of Lloyd George, felt humiliated by the contrast with the days of Edward I?

A world empire of either the U.S. or the U.S.S.R. is therefore preferable to the results of a continuation of the present international anarchy.

T here are, however, important reasons for preferring a victory of America. I am not contending that capitalism is better than communism; I think it not impossible that, if America were communist and Russia were capitalist, I should still be on the side of America. My reason for siding with America is that there is in that country more respect than in Russia for the things that I value in a civilized way of life. The things I have in mind are such as: freedom of thought, freedom of inquiry, freedom of discussion, and humane feeling. What a victory of Russia would mean is easily to be seen in Poland. There were flourishing universities in Poland, containing men of great intellectual eminence. Some of these men, fortunately, escaped; the rest disappeared. Education is now reduced to learning the formulae of Stalinist orthodoxy; it is only open (beyond the elementary stage) to young people whose parents are politically irreproachable, and it does not aim at producing any mental faculty except that of glib repetition of correct shibboleths and quick apprehension of the side that is winning official favor. From such an educational system nothing of intellectual value can result.

Meanwhile the middle class was annihilated by mass deportations, first in 1940, and again after the expulsion of the Germans. Politicians of majority parties were liquidated, imprisoned, or compelled to fly. Betraying friends to the police, or perjury when they are brought to trial, is often the only means of survival for those who have incurred governmental suspicions.

I do not doubt that, if this regime continues for a generation, it will succeed in its objects. Polish hostility to Russia will die out and be replaced by communist orthodoxy. Science and philosophy, art and literature, will become sycophantic adjuncts of government, jejune, narrow, and stupid. No individual will think, or even feel, for himself, but each will be contentedly a mere unit in the mass. A victory of Russia would, in time, make such a mentality world-wide. No doubt the complacency induced by success would ultimately lead to a relaxation of control, but the process would be slow and the revival of respect for the individual would be doubtful. For such reasons I should view a Russian victory as an appalling disaster.

A victory by the United States would have far less drastic consequences. In the first place, it would not be a victory of the United States in isolation, but of an alliance in which the other members would be able to insist upon retaining a large part of their traditional independence. One can hardly imagine the American army seizing the dons at Oxford and Cambridge and sending them to hard labor in Alaska. Nor do I think that they would accuse Mr. Attlee of plotting and compel him to fly to Moscow. Yet these are strict analogues of the things the Russians have done in Poland. After a victory of an alliance led by the United States there would still be British culture, French culture, Italian culture, and (I hope) German culture; there would not, therefore, be the same dead uniformity as would result from Soviet domination.

There is another important difference, and that is that Moscow’s orthodoxy is much more pervasive than that of Washington. In America, if you are a geneticist, you may hold whatever view of Mendelism the evidence makes you regard as the most probable; in Russia, if you are a geneticist who disagrees with Lysenko, you are liable to disappear mysteriously. In America, you may write a book debunking Lincoln if you feel so disposed; in Russia, if you should write a book debunking Lenin, it would not be published and you would be liquidated. If you are an American economist, you may hold, or not hold, that America is heading for a slump; in Russia, no economist dare question that an American slump is imminent. In America, if you are a professor of philosophy, you may be an idealist, a materialist, a pragmatist, a logical positivist, or whatever else may take your fancy; at congresses you can argue with men whose opinions differ from yours, and listeners can form a judgment as to who has the best of it. In Russia, you must be a dialectical materialist, but at one time the element of materialism outweighs the element of dialectic, and at other times it is the other way round. If you fail to follow the developments of official metaphysics with sufficient nimbleness, it will be the worse for you. Stalin at all times knows the truth about metaphysics, but you must not suppose that the truth this year is the same as it was last year. In such a world, intellect must stagnate, and even technological progress must soon come to an end.

Liberty, of the sort that communists despise, is important not only to intellectuals or to the more fortunate sections of society. Owing to its absence in Russia, the Soviet government has been able to establish a greater degree of economic inequality than exists in Great Britain or even in America. An oligarchy which controls all the means of publicity can perpetrate injustices and cruelties which would be scarcely possible if they were widely known. Only democracy and free publicity can prevent the holders of power from establishing a servile state, with luxury for the few and overworked poverty for the many. This is what is being done by the Soviet government wherever it is in secure control. There are, of course, economic inequalities everywhere, but in a democratic regime they tend to diminish, whereas under an oligarchy they tend to increase. And wherever an oligarchy has power, economic inequalities threaten to become permanent owing to the modern impossibility of successful rebellion.

I come now to the question, What should be our policy, in view of the various dangers to which mankind is exposed? To summarize the above arguments: we have to guard against three dangers—the extinction of the human race, a reversion to barbarism, and the establishment of a universal slave state involving misery for the vast majority and the disappearance of all progress in knowledge and thought. Either the first or second of these disasters is almost certain unless great wars can soon be brought to an end. Great wars can be brought to an end only by the concentration of armed force under a single authority. Such a concentration cannot be brought about by agreement, because of the opposition of Soviet Russia, but it must be brought about somehow.

The first step—and it is one which is now not very difficult—is to persuade the United States and the British Commonwealth of the absolute necessity for a military unification of the world. The governments of the English-speaking nations should then offer to all other nations the option of entering into a firm alliance, involving a pooling of military resources and mutual defense against aggression. In the case of hesitant nations, such as Italy, great inducements, economic and military, should be held out to produce their cooperation.

At a certain stage, when the alliance had acquired sufficient strength, any great power still refusing to join should be threatened with outlawry and, if recalcitrant, should be regarded as a public enemy. The resulting war, if it occurred fairly soon, would probably leave the economic and political structure of the United States intact, and would enable the victorious alliance to establish a monopoly of armed force, and therefore to make peace secure. But perhaps, if the alliance were sufficiently powerful, war would not be necessary, and the reluctant powers would prefer to enter it as equals rather than, after a terrible war, submit to it as vanquished enemies. If this were to happen, the world might emerge from its present dangers without another great war. I do not see any hope of such a happy issue by any other method. But whether Russia would yield when threatened with war is a question as to which I do not venture an opinion.

I have been dealing mainly with the gloomy aspects of the present situation of mankind. It is necessary to do so, in order to persuade the world to adopt measures running counter to traditional habits of thought and ingrained prejudices. But beyond the difficulties and probable tragedies of the near future there is the possibility of immeasurable good, and of greater well-being than has ever before fallen to the lot of man. This is not merely a possibility, but, if the Western democracies are firm and prompt, a probability. From the breakup of the Roman Empire to the present day, states have almost continuously increased in size. There are now only two fully independent states, America and Russia. The next step in this long historical process should reduce the two to one, and thus put an end to the period of organized wars, which began in Egypt some six thousand years ago. If war can be prevented without the establishment of a grinding tyranny, a weight will be lifted from the human spirit, deep collective fears will be exorcised, and as fear diminishes we may hope that cruelty also will grow less.

The uses to which men have put their increased control over natural forces are curious. In the nineteenth century they devoted themselves chiefly to increasing the numbers of Homo sapiens, particularly of the white variety. In the twentieth century they have, so far, pursued the exactly opposite aim. Owing to the increased productivity of labor, it has become possible to devote a larger percentage of the population to war. If atomic energy were to make production easier, the only effect, as things are, would be to make wars worse, since fewer people would be needed for producing necessaries. Unless we can cope with the problem of abolishing war, there is no reason whatever to rejoice in laborsaving technique, but quite the reverse. On the other hand, if the danger of war were removed, scientific technique could at last be used to promote human happiness. There is no longer any technical reason for the persistence of poverty, even in such densely populated countries as India and China. If war no longer occupied men’s thoughts and energies, we could, within a generation, put an end to all serious poverty throughout the world.

I have spoken of liberty as a good, but it is not an absolute good. We all recognize the need to restrain murderers, and it is even more important to restrain murderous states. Liberty must be limited by law, and its most valuable forms can only exist within a framework of law. What the world most needs is effective laws to control international relations. The first and most difficult step in the creation of such law is the establishment of adequate sanctions, and this is possible only through the creation of a single armed force in control of the whole world. But such an armed force, like a municipal police force, is not an end in itself; it is a means to the growth of a social system governed by law, where force is not the prerogative of private individuals or nations, but is exercised only by a neutral authority in accordance with rules laid down in advance. There is hope that law, rather than private force, may come to govern the relations of nations within the present century. If this hope is not realized we face utter disaster; if it is realized, the world will be far better than at any previous period in the history of man.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Bertrand Russell His Philosophy, Main Themes and Main Patterns

Bertrand Russell and his unpopular essays

Related Papers

José Reséndiz

Chad Trainer

Almost five decades after his death, there is still ample reason to pay attention to the life and legacy of Bertrand Russell. This is true not only because of his role as one of the founders of analytic philosophy, but also because of his important place in twentieth-century history as an educator, public intellectual, critic of organized religion, humanist, and peace activist. The papers in this anthology explore Russell’s life and legacy from a wide variety of perspectives. This is altogether fitting, given the many-sided nature of Russell, his life, and his work. The first section of the book considers Russell the man, and draws lessons from Russell’s complicated personal life. The second examines Russell the philosopher, and the philosophical world within which his work was embedded. The third scrutinizes Russell the atheist and critic of organized religion, inquiring which parts of his critical stance are worth emulating today. The final section revisits Russell the political a...

Journal of the History of Philosophy

Andrew Irvine

William Bruneau

Ayesha Tariq

isara solutions

International Res Jour Managt Socio Human

(1872-1970) turned out to be the torch bearer in the twentieth century. Russell did not think there should be separate methods for philosophy. He thought philosophers should strive to answer the most general of propositions about the world and this would help eliminate confusions. In particular, he wanted to end what he saw as the excesses of metaphysics. His influence remains strong in the distinction between two ways in which we can be familiar with objects: knowledge by acquaintance and knowledge by description. Russell was a believer in the scientific method, that science reaches only tentative answers, that scientific progress is piecemeal, and attempts to find organic unities were largely futile. He believed the same was true of philosophy. Russell held that the ultimate objective of both science and philosophy was to understand reality, not simply to make predictions. Moral Issues is one of the coinages of Bertrand Russell which gained great currency in our time. It is a fact that Moral Issues is much older than the label given to it by Bertrand Russell. As a philosophy comprising thoughts and reflections of the creative writer on his own art, it may be traced all the way through the Renaissance and even before to our times. Alfred North Whitehead, his teacher, colleague and in due course collaborator had recommended his scholarship. His many friends, such as the Trevelyan brothers and G. E. Moore, whose philosophy eventually influenced him profoundly. Here, it was that he heard Moore read a paper which began, 'In the beginning was matter, and matter begat the devil and the devil begat God'. 'The paper ended with the death first of God and then of the devil, leaving matter alone as in the beginning' (Autobiography) that influenced Russell the most. Bertrand Russell's dissent and doubt were to extend much further. He inherited a fearless individualism, and the texts which his grandmother inscribed in the fly-leaf of his Bible affected him profoundly: 'Thou shalt not follow a multitude to do evil' was precisely observed and 'Be strong, and of good courage; be not afraid, neither be thou dismayed, for the Lord Thy God is with Thee where so ever thou goest' was followed in what Russell saw as the cause of humanity rather than the Lord. Along with Moore, Russell then believed that moral facts were objective, but known only through intuition; that they were simple properties of objects, not equivalent (e.g., pleasure is good) to the natural objects to which they are often ascribed and that these simple, undefinable moral properties cannot be analysed using the non-moral properties with which they are associated. In time, however, he came to agree with his philosophical hero, David Hume, who

Merrill Ring

Essays in Philosophy

Steven Schroeder

Michael Foot's introduction to this new edition of Bertrand Russell's autobiography locates it in a controversy with Ray Monk's biographical study (the first volume of which appeared in 1996, the second in 2001). Foot takes note of Monk's claim to deal with "philosophical questions overlooked or bowdlerized by previous biographers or by Russell himself" (ix) but sees his study as an attack on Russell's reputation. He introduces the autobiography as evidence that Russell took "the precaution of speaking for himself" (x). Foot goes on to discuss some of the risks involved in autobiography, particularly the dual risk of falling victim to hubris or appearing to do so. It is a tribute to Russell that Foot believes the best response to Monk's attack is not to defend him but rather to let him speak for himself–not to publish another new biography but to republish Russell's account of his own life. Essays in Philosophy, Vol. 4 No. 2, June 2003

Umapati Nath

RELATED PAPERS

The Oncologist

Catherine Kasongo Mwaba

Journal of Nursing Ufpe on Line Jnuol Doi 10 5205 01012007

Celia Regina Maganha e Melo

The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism

Ingolf Cascorbi

Greener Management International

Achara Chandrachai

Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting

Maryam Allahyar

George Mpedi

Jurnal Global & Strategis

Marquette毕业证书 马凯特大学学位证

Science Advances

Olivia Thomas

Journal of Molecular Structure: THEOCHEM

Mário Valente

Children's Readings: Studies in Children's Literature

Alexey Vdovin

International Journal of Cardiology

joseph Balogun

Aprilia Kusbandari

International Journal of Bioscience, Biochemistry and Bioinformatics

Ajit Kelkar

Habaršy - A̋l-Farabi atyndag̣y K̦azak̦ memlekettik ụlttyk̦ universiteti. Halyk̦aralyk̦ k̦atynastar žène Halyk̦aralyk̦ k̦ụk̦yk̦ seriâsy

Adilbek Yermekbayev

Sustainability

Sawsan Darwish

QUT毕业证书 QUT毕业证成绩单

Proceedings of MOL2NET 2019, International Conference on Multidisciplinary Sciences, 5th edition

Enrique Onieva

Nordic Studies in Science Education

Christina Ottander

Nibedita Dey

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Russell’s View on World Government in his Essay The Future of Mankind

Russell’s View on World Government

Bertrand Russell surely disproves the common established notion about philosophers, that, they are absent-minded and always engage their heads in making speculations, when he meditates on the possibilities regarding “ The Future of Mankind “. He has done so, because of his high sensitivity and deep concern towards human beings. He was called as a traitor to his country because of his anti-war stand during the First World War. But his only concern was towards ‘humanity’. Later he was awarded a Noble Prize for contribution towards peace. In the words of Erich From:

“Bertrand Russell fights against threatening slaughter. because he is a who loves life.”

Russell discuses three possibilities about “The Future of Mankind.” According to him, one is the com extinction of human life on earth, the second is that human life will be reduced to barbarism and the final is that there will be a world government that will control all nations and countries. Among these the first possibility, describes, is the complete extinction of all human beings. This might happen after the Second World War in atomic weapons will be used. Russell deals it logically, for he says, if still there will be some life after the end of that war, there would soon be another war, for there would such “die-hard” in the super powers, who would prefer the extermination of life, than surrendering to the victory of the other power.

And if any man would miraculously be able to escape from death, he may consider himself to be the emperor of the whole world, but his reign would not be long and his subjects would be only dead bodies and Russell says:

“With his death the uneasy episode of life will end, and the peaceful rocks will revolve unchanged, until the sun explodes.”

The second possibility, which Russell discusses, is the reversal of civilization to its primitive conditions. Russell suggests if the Second World War fails to eliminate all signs of life, still that destruction would take world to the age of “barbarism”. For in the war, the major cities and industrial areas would be destroyed and the bacteriological warfare would destroy crops and cause famine. Russell says there may be a few libraries and laboratories and scientists. But the people, might kill the remaining few scientists, in hope of some “Golden Age”, for:

“Extreme hopes are born of extreme misery and in such a world hopes could only be irrational.”

The third possibility, according to Russell, is the establishment of a universal government all over the world. He discusses this idea in more than one ways in which it could occur. The one is the victory of America, in the Second World War. Other is the victory of Russia, or the world government, would emerge as a result of mutual agreement. The best among these ways is the idea of mutual agreement.

Russell’s view of the world government has been criticized greatly. People have raised arguments considering it as a “Utopian ideal”. Most of the people think that such an alliance cannot be brought peacefully, for no nation would surrender her liberty. Russell also admits that the chances of government in a formal ways are extremely remote. He thinks that a world government , would not be for voluntarily, but it would have to be brought about by force.

Russell prefers America to control the government and he has given many reasons for his preference to America but his preference has no political and ideological basis, but it totally depends on the probable condition of people under these states. The major reason to prefer America is that, she respects the values of civilized life like freedom of thought, freedom of inquiry and humanness. But on the other hand, in communistic countries like Russia there is not liberty for individuals and the government has a strict hold on the common masses.

Moreover, there is considerably less orthodoxy in America than in Russia. There, scientist, authors and philosophers can choose any subject regardless of state interest. While in Russia such things are also influenced by official views.

Russell suggests yet another way to prevent a horrible war. In his opinion, America would make an alliance with the British common wealth nations and with other European nations who want to join them. All the military power, of these countries, and weapons should be united and then they should declare war on the nation. In this way Russia might also be agreed to join the alliance just by the threat of war. But still he does not leave the possibility of Russian refusal.

In such an alliance, there should also be a legal check on the power of the leader, by other nations, so there would not be a “chance of corruption”.

Among the many advantages, of a single world government, is that the defense expenditures of every nation a diminish and by this way human beings would be more happy than before.

But a little earlier than this, Russell’s suggestions did not seem to be implemented to the world. For, China has emerged as a world power with nuclear weapons and it would certainly not like America as the only dominant on to control both, East and West.

- Summary of Russell’s Essay, Knowledge and Wisdom

However, Russell’s chief concern in all this discussion was his good will and sincere concern towards peace and survival of mankind. We can surely conclude that he was a true optimist, pacifist and humanist.

Related posts:

- Shooting an Elephant Analysis | Orwell’s View on Imperialism in Shooting an Elephant

- What according to Arnold are the Essential Features of a Modern Age? How far did ancient Greece exhibit them?

- On the Modern Element in Literature by Mathew Arnold | Full Text

- Character Analysis of Sir Roger de Coverley in Addison’s Essay

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- _Basic Guide

- __Classical Drama

- __Classical Poetry

- __Classical Novel

- __American Literature

- __Literary Essays

- __Modern Drama

- __Modern Novel

- __Modern Poetry

- __Literary Criticism

- English for BA

- Acknowledgements

Critical Analysis - The Future of Mankind by Bertrand Russell

Who is bertrand russell.

Mr. Russell is the most quoted name in the world of politics. He opened his eyes on 18 May 1872 in Trellech. Russell was proficient in mathematics, philosophy, logic, history and in social criticism. His collection of essays, known as "Unpopular Essays" is a mark of his accurate foresight. The essay Future of Mankind pretty much represents what its title says. The essay foretells how the mankind of the earth may perceive its future? [This is what we will discuss in the later lines]

Russell gives three major possibilities when he starts this essay. The first possibility is if a third world war gets ignited, it will wipe out all the human population from the surface of the planet earth. The second possibility is after the third world war, only a small number of people will be left who will recolour the human life once again after the cruel barbarism. And the third possibility is about the formation of a world government which might be established after peaceful negotiations and war if necessary. Russell suggests mankind to avoid the first two possibilities and to focus on the third one for the globalization of peace.

Russell openly hints that the establishment of a single world government through force as Soviet Russia may retaliate against the concept of a world government. All the military force in the leadership of the USA has to fight against the [communist] Soviet Russia and to defeat it to retain the worldly peace.

Russell says that the U.S.A. respects and grants its masses the freedom of inquiry, thought, discussion and human feelings. On the other hand, Russia idolizes a specific agenda through narrowing the science, art and literature. The freedom which a person enjoys is absent in Russia. But Russell also advocates that the freedom must be limited by the law so that the freedom should have its value.

Is Russell a Prophet?

In this essay, Russell shows his political insight at its best. His words truly imply with today's situation (but rather differently) and most of his prophecies went true by the time when he was writing this essay. He signalled at a possible war between Russia and the USA which did happen indirectly. So Russell is partially a prophet.

Russell Advocates Democratic System

Russell's admiration of the democratic freedom found in the U.S.A. and in the Great Britain significantly holds water against the totalitarian influence which persisted Russia and China. According to Russell, the USA and the UK are champions of democracy but Russia is a looser and China does not also leg behind the race of communism in this regard. So, Russell is a true advocator of democracy.

The War Between Russia and the USA could Destroy the Whole World

Russell directly asserts that if democracy has to survive against the communism, then the democratic powers (the UK and the USA) have to wage a war against Russia and China. This is a severe miscalculation of Bertrand Russell who forgets that Russia is the owner of the largest reserves of nuclear bombs. If a war is inflamed between the two, it will prove the final knell (a bell of death) to the existence of mankind on the planet earth. But both are aware of this fact of great danger so they have decided not to create an infernal planet. A balance of powers between the two has terminated the anxiety of any possible war in future.

The Idea of a World Government will Remain a Dream

The concept of a world government sounds utopian and impractical but valid at its point. Russell is himself aware of the fact that the giant Russia and even the small countries will not accept the idea of a world government. Nationalism and ego of the small countries like Pakistan, Iran and Afghanistan etc. have risen to a sky-like height and they launch challenges against other nations as if they were the owner of the world. Such independent behaviour will minimize the sense of a single government.

Even if we may not agree with Russell's prophecies about the future, we still have to admit that the main motive behind his essay is the protection of mankind from a possible extinction through a nuclear war. This essay of Russell is marked with vivid clarity and transparent lucidity while retaining his superb command in the English Prose.

Sources, References and Suggested Readings

- Notes provided by Sir Saffi

- https://englishhelplineforall.blogspot.com/2016/02/the-future-ofmankind-by-bertrand.html

- https://neoenglishsystem.blogspot.com/2010/09/analyze-and-comment-on-ideas-expressed.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bertrand_Russell?oldformat=true

It's time to pen down your opinions!

love it, being a writer from the mesmerising places of mianwali/ the land of i-khan, just love your words.

thanks, respected sir.

Contact Form

January 1, 2009

12 min read

The Future of Man—How Will Evolution Change Humans?

Contrary to popular belief, humans continue to evolve. Our bodies and brains are not the same as our ancestors' were—or as our descendants' will be

By Peter Ward

When you ask for opinions about what future humans might look like, you typically get one of two answers. Some people trot out the old science-fiction vision of a big-brained human with a high forehead and higher intellect. Others say humans are no longer evolving physically—that technology has put an end to the brutal logic of natural selection and that evolution is now purely cultural.

The big-brain vision has no real scientific basis. The fossil record of skull sizes over the past several thousand generations shows that our days of rapid increase in brain size are long over. Accordingly, most scientists a few years ago would have taken the view that human physical evolution has ceased. But DNA techniques, which probe genomes both present and past, have unleashed a revolution in studying evolution; they tell a different story. Not only has Homo sapiens been doing some major genetic reshuffling since our species formed, but the rate of human evolution may, if anything, have increased. In common with other organisms, we underwent the most dramatic changes to our body shape when our species first appeared, but we continue to show genetically induced changes to our physiology and perhaps to our behavior as well. Until fairly recently in our history, human races in various parts of the world were becoming more rather than less distinct. Even today the conditions of modern life could be driving changes to genes for certain behavioral traits.

If giant brains are not in store for us, then what is? Will we become larger or smaller, smarter or dumber? How will the emergence of new diseases and the rise in global temperature shape us? Will a new human species arise one day? Or does the future evolution of humanity lie not within our genes but within our technology, as we augment our brains and bodies with silicon and steel? Are we but the builders of the next dominant intelligence on the earth—the machines?

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The Far and Recent Past Tracking human evolution used to be the province solely of paleontologists, those of us who study fossil bones from the ancient past. The human family, called the Hominidae, goes back at least seven million years to the appearance of a small proto-human called Sahelanthropus tchadensis .

Since then, our family has had a still disputed, but rather diverse, number of new species in it—as many as nine that we know of and others surely still hidden in the notoriously poor hominid fossil record. Because early human skeletons rarely made it into sedimentary rocks before they were scavenged, this estimate changes from year to year as new discoveries and new interpretations of past bones make their way into print [see “Once We Were Not Alone,” by Ian Tattersall; Scientific American , January 2000, and “ An Ancestor to Call Our Own ,” by Kate Wong; Scientific American , January 2003].

Each new species evolved when a small group of hominids somehow became separated from the larger population for many generations and then found itself in novel environmental conditions favoring a different set of adaptations. Cut off from kin, the small population went its own genetic route and eventually its members could no longer successfully reproduce with the parent population.

The fossil record tells us that the oldest member of our own species lived 195,000 years ago in what is now Ethiopia. From there it spread out across the globe. By 10,000 years ago modern humans had successfully colonized each of the continents save Antarctica, and adaptations to these many locales (among other evolutionary forces) led to what we loosely call races. Groups living in different places evidently retained just enough connections with one another to avoid evolving into separate species. With the globe fairly well covered, one might expect that the time for evolving was pretty much finished.

But that turns out not to be the case. In a study published a year ago Henry C. Harpending of the University of Utah, John Hawks of the University of Wisconsin–Madison and their colleagues analyzed data from the international haplotype map of the human genome [see “ Traces of a Distant Past ,” by Gary Stix; Scientific American, July 2008]. They focused on genetic markers in 270 people from four groups: Han Chinese, Japanese, Yoruba and northern Europeans. They found that at least 7 percent of human genes underwent evolution as recently as 5,000 years ago. Much of the change involved adaptations to particular environments, both natural and human-shaped. For example, few people in China and Africa can digest fresh milk into adulthood, whereas almost everyone in Sweden and Denmark can. This ability presumably arose as an adaptation to dairy farming.

Another study by Pardis C. Sabeti of Harvard University and her colleagues used huge data sets of genetic variation to look for signs of natural selection across the human genome. More than 300 regions on the genome showed evidence of recent changes that improved people’s chance of surviving and reproducing. Examples included resistance to one of Africa’s great scourges, the virus causing Lassa fever; partial resistance to other diseases, such as malaria, among some African populations; changes in skin pigmentation and development of hair follicles among Asians; and the evolution of lighter skin and blue eyes in northern Europe.

Harpending and Hawks’s team estimated that over the past 10,000 years humans have evolved as much as 100 times faster than at any other time since the split of the earliest hominid from the ancestors of modern chimpanzees. The team attributed the quickening pace to the variety of environments humans moved into and the changes in living conditions brought about by agriculture and cities. It was not farming per se or the changes in the landscape that conversion of wild habitat to tamed fields brought about but the often lethal combination of poor sanitation, novel diet and emerging diseases (from other humans as well as domesticated animals). Although some researchers have expressed reservations about these estimates, the basic point seems clear: humans are first-class evolvers.

Unnatural Selection During the past century, our species’ circumstances have again changed. The geographic isolation of different groups has been broached by the ease of transportation and the dismantling of social barriers that once kept racial groups apart. Never before has the human gene pool had such widespread mixing of what were heretofore entirely separated local populations of our species. In fact, the mobility of humanity might be bringing about the homogenization of our species. At the same time, natural selection in our species is being thwarted by our technology and our medicines. In most parts of the globe, babies no longer die in large numbers. People with genetic damage that was once fatal now live and have children. Natural predators no longer affect the rules of survival.

Steve Jones of University College London has argued that human evolution has essentially ceased. At a Royal Society of Edinburgh debate in 2002 entitled “Is Evolution Over?” he said: “Things have simply stopped getting better, or worse, for our species. If you want to know what Utopia is like, just look around—this is it.” Jones suggested that, at least in the developed world, almost everyone has the opportunity to reach reproductive age, and the poor and rich have an equal chance of having children. Inherited disease resistance—say, to HIV—may still confer a survival advantage, but culture, rather than genetic inheritance, is now the deciding factor in whether people live or die. In short, evolution may now be memetic—involving ideas—rather than genetic [see “The Power of Memes,” by Susan Blackmore; Scientific American, October 2000].

Another point of view is that genetic evolution continues to occur even today, but in reverse. Certain characteristics of modern life may drive evolutionary change that does not make us fitter for survival—or that even makes us less fit. Innumerable college students have noticed one potential way that such “inadaptive” evolution could happen: they put off reproduction while many of their high school classmates who did not make the grade started having babies right away. If less intelligent parents have more kids, then intelligence is a Darwinian liability in today’s world, and average intelligence might evolve downward.

Such arguments have a long and contentious history. One of the many counterarguments is that human intelligence is made up of many different abilities encoded by a large number of genes. It thus has a low degree of heritability, the rate at which one generation passes the trait to the next. Natural selection acts only on heritable traits. Researchers actively debate just how heritable intelligence is [see “ The Search for Intelligence ,” by Carl Zimmer; Scientific American, October 2008], but they have found no sign that average intelligence is in fact decreasing.

Even if intelligence is not at risk, some scientists speculate that other, more heritable traits could be accumulating in the human species and that these traits are anything but good for us. For instance, behavior disorders such as Tourette’s syndrome and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) may, unlike intelligence, be encoded by but a few genes, in which case their heritability could be very high. If these disorders increase one’s chance of having children, they could become ever more prevalent with each generation. David Comings, a specialist in these two diseases, has argued in scientific papers and a 1996 book that these conditions are more common than they used to be and that evolution might be one reason: women with these syndromes are less likely to attend college and thus tend to have more children than those who do not. But other researchers have brought forward serious concerns about Comings’s methodology. It is not clear whether the incidence of Tourette’s and ADHD is, in fact, increasing at all. Research into these areas is also made more difficult because of the perceived social stigma that many of these afflictions attach to their carriers.

Although these particular examples do not pass scientific muster, the basic line of reasoning is plausible. We tend to think of evolution as something involving structural modification, yet it can and does affect things invisible from the outside—behavior. Many people carry the genes making them susceptible to alcoholism, drug addiction and other problems. Most do not succumb, because genes are not destiny; their effect depends on our environment. But others do succumb, and their problems may affect whether they survive and how many children they have. These changes in fertility are enough for natural selection to act on. Much of humanity’s future evolution may involve new sets of behaviors that spread in response to changing social and environmental conditions. Of course, humans differ from other species in that we do not have to accept this Darwinian logic passively.

Directed Evolution We have directed the evolution of so many animal and plant species. Why not direct our own? Why wait for natural selection to do the job when we can do it faster and in ways beneficial to ourselves? In the area of human behavior, for example, geneticists are tracking down the genetic components not just of problems and disorders but also of overall disposition and various aspects of sexuality and competitiveness, many of which may be at least partially heritable. Over time, elaborate screening for genetic makeup may become commonplace, and people will be offered drugs based on the results.

The next step will be to actually change people’s genes. That could conceivably be done in two ways: by changing genes in the relevant organ only (gene therapy) or by altering the entire genome of an individual (what is known as germ-line therapy). Researchers are still struggling with the limited goal of gene therapy to cure disease. But if they can ever pull off germ-line therapy, it will help not only the individual in question but also his or her children. The major obstacle to genetic engineering in humans will be the sheer complexity of the genome. Genes usually perform more than one function; conversely, functions are usually encoded by more than one gene. Because of this property, known as pleiotropy, tinkering with one gene can have unintended consequences.

Why try at all, then? The pressure to change genes will probably come from parents wanting to guarantee their child is a boy or a girl; to endow their children with beauty, intelligence, musical talent or a sweet nature; or to try to ensure that they are not helplessly disposed to become mean-spirited, depressed, hyperactive or even criminal. The motives are there, and they are very strong. Just as the push by parents to genetically enhance their children could be socially irresistible, so, too, would be an assault on human aging. Many recent studies suggest that aging is not so much a simple wearing down of body parts as it is a programmed decay, much of it genetically controlled. If so, the next century of genetic research could unlock numerous genes controlling many aspects of aging. Those genes could be manipulated.

Assuming that it does become practical to change our genes, how will that affect the future evolution of humanity? Probably a great deal. Suppose parents alter their unborn children to enhance their intelligence, looks and longevity. If the kids are as smart as they are long-lived—an IQ of 150 and a lifespan of 150 years—they could have more children and accumulate more wealth than the rest of us. Socially they will probably be drawn to others of their kind. With some kind of self-imposed geographic or social segregation, their genes might drift and eventually differentiate as a new species. One day, then, we will have it in our power to bring a new human species into this world. Whether we choose to follow such a path is for our descendants to decide.

The Borg Route Even less predictable than our use of genetic manipulation is our manipulation of machines—or they of us. Is the ultimate evolution of our species one of symbiosis with machines, a human-machine synthesis? Many writers have predicted that we might link our bodies with robots or upload our minds into computers. In fact, we are already dependent on machines. As much as we build them to meet human needs, we have structured our own lives and behavior to meet theirs. As machines become ever more complex and interconnected, we will be forced to try to accommodate them. This view was starkly enunciated by George Dyson in his 1998 book Darwin among the Machines : “Everything that human beings are doing to make it easier to operate computer networks is at the same time, but for different reasons, making it easier for computer networks to operate human beings.... Darwinian evolution, in one of those paradoxes with which life abounds, may be a victim of its own success, unable to keep up with non-Darwinian processes that it has spawned.”

Our technological prowess threatens to swamp the old ways that evolution works. Consider two different views of the future taken from an essay in 2004 by evolutionary philosopher Nick Bostrom of the University of Oxford. On the optimistic side, he wrote: “The big picture shows an overarching trend towards increasing levels of complexity, knowledge, consciousness, and coordinated goal-directed organization, a trend which, not to put too fine a point on it, we may label ‘progress.’ What we shall call the Panglossian view maintains that this past record of success gives us good grounds for thinking that evolution (whether biological, memetic or technological) will continue to lead in desirable directions.”

Although the reference to “progress” surely causes the late evolutionary biologist Steven Jay Gould to spin in his grave, the point can be made. As Gould argued, fossils, including those from our own ancestors, tell us that evolutionary change is not a continuous thing; rather it occurs in fits and starts, and it is certainly not “progressive” or directional. Organisms get smaller as well as larger. But evolution has indeed shown at least one vector: toward increasing complexity. Perhaps that is the fate of future human evolution: greater complexity through some combination of anatomy, physiology or behavior. If we continue to adapt (and undertake some deft planetary engineering), there is no genetic or evolutionary reason that we could not still be around to watch the sun die. Unlike aging, extinction does not appear to be genetically programmed into any species.

The darker side is all too familiar. Bostrom (who must be a very unsettled man) offered a vision of how uploading our brains into computers could spell our doom. Advanced artificial intelligence could encapsulate the various components of human cognition and reassemble those components into something that is no longer human—and that would render us obsolete. Bostrom predicted the following course of events: “Some human individuals upload and make many copies of themselves. Meanwhile, there is gradual progress in neuroscience and artificial intelligence, and eventually it becomes possible to isolate individual cognitive modules and connect them up to modules from other uploaded minds.... Modules that conform to a common standard would be better able to communicate and cooperate with other modules and would therefore be economically more productive, creating a pressure for standardization.... There might be no niche for mental architectures of a human kind.”

As if technological obsolescence were not disturbing enough, Bostrom concluded with an even more dreary possibility: if machine efficiency became the new measure of evolutionary fitness, much of what we regard as quintessentially human would be weeded out of our lineage. He wrote: “The extravagancies and fun that arguably give human life much of its meaning—humor, love, game-playing, art, sex, dancing, social conversation, philosophy, literature, scientific discovery, food and drink, friendship, parenting, sport—we have preferences and capabilities that make us engage in such activities, and these predispositions were adaptive in our species’ evolutionary past; but what ground do we have for being confident that these or similar activities will continue to be adaptive in the future? Perhaps what will maximize fitness in the future will be nothing but nonstop high-intensity drudgery, work of a drab and repetitive nature, aimed at improving the eighth decimal of some economic output measure.”

In short, humanity’s future could take one of several routes, assuming we do not go extinct:

Stasis. We largely stay as we are now, with minor tweaks, mainly as races merge.

Speciation. A new human species evolves on either this planet or another.

Symbiosis with machines. Integration of machines and human brains produces a collective intelligence that may or may not retain the qualities we now recognize as human.

Quo vadis Homo futuris?

Note: This article was originally printed with the title, "What Will Become of Homo Sapiens ?"

- Blackholes, Wormholes and the Tenth Dimension

- Follow the Methane! New NASA Strategy for Mars?

- Hyperspace – A Scientific Odyssey

- Hyperspace and a Theory of Everything

- M-Theory: The Mother of all SuperStrings

- So You Want to Become a Physicist?

- The Physics of Extraterrestrial Civilizations

- The Physics of Interstellar Travel

- The Physics of Time Travel

- What to Do If You Have a Proposal for the Unified Field Theory?

- Excerpt from ‘THE FUTURE OF THE MIND’

- QUANTUM SUPREMACY: How The Quantum Computer Revolution Will Change Everything

- THE FUTURE OF HUMANITY: Our Destiny In The Universe

- THE FUTURE OF THE MIND: The Scientific Quest to Understand, Enhance, and Empower the Mind

- THE GOD EQUATION: The Quest for a Theory of Everything

- Radio Programs

Physicist, Futurist, Bestselling Author, Popularizer of Science

- Book Updates

- Dr. Kaku's Universe

- Kaku on Movies

- News Appearances

- Public Appearances

- Science Frontiers

- Television & Media

The #1 bestselling author of THE FUTURE OF THE MIND traverses the frontiers of astrophysics, artificial intelligence, and technology to offer a stunning vision of man’s future in space, from settling Mars to traveling to distant galaxies in MICHIO KAKU’S THE FUTURE OF HUMANITY: Our Destiny In The Universe .

ORDER NOW AT THESE FINE BOOKSELLERS…

Formerly the domain of fiction, moving human civilization to the stars is increasingly becoming a scientific possibility–and a necessity. Whether in the near future due to climate change and the depletion of finite resources, or in the distant future due to catastrophic cosmological events, we must face the reality that humans will one day need to leave planet Earth to survive as a species.

World-renowned physicist and futurist Michio Kaku explores in rich, intimate detail the process by which humanity may gradually move away from the planet and develop a sustainable civilization in outer space. Kaku reveals how cutting-edge developments in robotics, nanotechnology, and biotechnology may allow us to terraform and build habitable cities on Mars. He then takes us beyond the solar system to nearby stars, which may soon be reached by nanoships traveling on laser beams at near the speed of light.

Finally, he brings us beyond our galaxy, and even beyond our universe, to the possibility of immortality, showing us how humans may someday be able to leave our bodies entirely and laser port to new havens in space. With irrepressible enthusiasm and wonder, Dr. Kaku takes readers on a fascinating journey to a future in which humanity may finally fulfill its long-awaited destiny among the stars.

READY FOR MORE?

For the complete library of books by Dr. Michio Kaku, click here .

- Publications

- TAG CLOUD ai alien intelligence book BookTour2021 Book Tour 2023 cataclysm CBSN CBS News CBS This Morning Charlie Rose cnn cosmology earthquake earth science Elon Musk FOX Business fox news Gayle King human civilization Kennedy lhc life beyond earth manned space mission mars Mission to Mars moon moon base MSNBC NASA natural disaster new space race Norah O'Donnell physics of the impossible plate tectonics private sector reusable rocket seismic surge solar system space space exploration space explore SpaceX String Theory theory of everything wsj

- FIND BY HISTORY

- FIND BY TAG

This feature has not been activated yet.

FOR ALL PUBLIC EVENTS, CLICK HERE .

- February 2024

- December 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- February 2021

- January 2021

- November 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- August 2018

- February 2018

- December 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- October 2015

- September 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- February 2014

- February 2013

- February 2012

- August 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- August 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- November 2009

- October 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

© COPYRIGHT 2024 MICHIO KAKU. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Future evolution: from looks to brains and personality, how will humans change in the next 10,000 years?

Senior Lecturer in Paleontology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Bath

Disclosure statement

Nicholas R. Longrich does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Bath provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

READER QUESTION: If humans don’t die out in a climate apocalypse or asteroid impact in the next 10,000 years, are we likely to evolve further into a more advanced species than what we are at the moment? Harry Bonas, 57, Nigeria

Humanity is the unlikely result of 4 billion years of evolution.

From self-replicating molecules in Archean seas, to eyeless fish in the Cambrian deep, to mammals scurrying from dinosaurs in the dark, and then, finally, improbably, ourselves – evolution shaped us.

Organisms reproduced imperfectly. Mistakes made when copying genes sometimes made them better fit to their environments, so those genes tended to get passed on. More reproduction followed, and more mistakes, the process repeating over billions of generations. Finally, Homo sapiens appeared. But we aren’t the end of that story. Evolution won’t stop with us, and we might even be evolving faster than ever .

This article is part of Life’s Big Questions The Conversation’s new series, co-published with BBC Future, seeks to answer our readers’ nagging questions about life, love, death and the universe. We work with professional researchers who have dedicated their lives to uncovering new perspectives on the questions that shape our lives.

It’s hard to predict the future. The world will probably change in ways we can’t imagine. But we can make educated guesses. Paradoxically, the best way to predict the future is probably looking back at the past, and assuming past trends will continue going forward. This suggests some surprising things about our future.

We will likely live longer and become taller, as well as more lightly built. We’ll probably be less aggressive and more agreeable, but have smaller brains. A bit like a golden retriever, we’ll be friendly and jolly, but maybe not that interesting. At least, that’s one possible future. But to understand why I think that’s likely, we need to look at biology.

The end of natural selection?

Some scientists have argued that civilisation’s rise ended natural selection . It’s true that selective pressures that dominated in the past – predators , famine, plague , warfare – have mostly disappeared.

Starvation and famine were largely ended by high-yield crops, fertilisers and family planning. Violence and war are less common than ever, despite modern militaries with nuclear weapons, or maybe because of them . The lions, wolves and sabertoothed cats that hunted us in the dark are endangered or extinct. Plagues that killed millions – smallpox, Black Death, cholera – were tamed by vaccines, antibiotics, clean water.

But evolution didn’t stop; other things just drive it now. Evolution isn’t so much about survival of the fittest as reproduction of the fittest. Even if nature is less likely to murder us, we still need to find partners and raise children, so sexual selection now plays a bigger role in our evolution.

And if nature doesn’t control our evolution anymore, the unnatural environment we’ve created – culture, technology, cities – produces new selective pressures very unlike those we faced in the ice age. We’re poorly adapted to this modern world; it follows that we’ll have to adapt.

And that process has already started. As our diets changed to include grains and dairy, we evolved genes to help us digest starch and milk . When dense cities created conditions for disease to spread, mutations for disease resistance spread too. And for some reason, our brains have got smaller . Unnatural environments create unnatural selection.

To predict where this goes, we’ll look at our prehistory, studying trends over the past 6 million years of evolution. Some trends will continue, especially those that emerged in the past 10,000 years, after agriculture and civilisation were invented.

We’re also facing new selective pressures, such as reduced mortality. Studying the past doesn’t help here, but we can see how other species responded to similar pressures. Evolution in domestic animals may be especially relevant – arguably we’re becoming a kind of domesticated ape, but curiously, one domesticated by ourselves .

I’ll use this approach to make some predictions, if not always with high confidence. That is, I’ll speculate.

Humans will almost certainly evolve to live longer – much longer. Life cycles evolve in response to mortality rates, how likely predators and other threats are to kill you. When mortality rates are high, animals must reproduce young, or might not reproduce at all. There’s also no advantage to evolving mutations that prevent ageing or cancer - you won’t live long enough to use them.

When mortality rates are low, the opposite is true. It’s better to take your time reaching sexual maturity. It’s also useful to have adaptations that extend lifespan, and fertility, giving you more time to reproduce. That’s why animals with few predators - animals that live on islands or in the deep ocean, or are simply big - evolve longer lifespans. Greenland sharks , Galapagos tortoises and bowhead whales mature late, and can live for centuries.

Even before civilisation, people were unique among apes in having low mortality and long lives . Hunter-gatherers armed with spears and bows could defend against predators; food sharing prevented starvation. So we evolved delayed sexual maturity, and long lifespans - up to 70 years .

Still, child mortality was high - approaching 50% or more by age 15. Average life expectancy was just 35 years . Even after the rise of civilisation, child mortality stayed high until the 19th century, while life expectancy went down - to 30 years - due to plagues and famines.

Then, in the past two centuries, better nutrition, medicine and hygiene reduced youth mortality to under 1% in most developed nations. Life expectancy soared to 70 years worldwide , and 80 in developed countries. These increases are due to improved health, not evolution – but they set the stage for evolution to extend our lifespan.

Now, there’s little need to reproduce early. If anything, the years of training needed to be a doctor, CEO, or carpenter incentivise putting it off. And since our life expectancy has doubled, adaptations to prolong lifespan and child-bearing years are now advantageous. Given that more and more people live to 100 or even 110 years - the record being 122 years - there’s reason to think our genes could evolve until the average person routinely lives 100 years or even more.

Size, and strength

Animals often evolve larger size over time; it’s a trend seen in tyrannosaurs , whales, horses and primates - including hominins.

Early hominins like Australopithecus afarensis and Homo habilis were small, four to five feet (120cm-150cm) tall. Later hominins - Homo erectus , Neanderthals, Homo sapiens - grew taller. We’ve continued to gain height in historic times, partly driven by improved nutrition, but genes seem to be evolving too .

Why we got big is unclear. In part, mortality may drive size evolution ; growth takes time, so longer lives mean more time to grow. But human females also prefer tall males . So both lower mortality and sexual preferences will likely cause humans to get taller. Today, the tallest people in the world are in Europe, led by the Netherlands. Here, men average 183cm (6ft); women 170cm (5ft 6in). Someday, most people might be that tall, or taller.

As we’ve grown taller, we’ve become more gracile. Over the past 2 million years, our skeletons became more lightly built as we relied less on brute force, and more on tools and weapons. As farming forced us to settle down, our lives became more sedentary, so our bone density decreased . As we spend more time behind desks, keyboards and steering wheels, these trends will likely continue.

Humans have also reduced our muscles compared to other apes , especially in our upper bodies. That will probably continue. Our ancestors had to slaughter antelopes and dig roots; later they tilled and reaped in the fields. Modern jobs increasingly require working with people, words and code - they take brains, not muscle. Even for manual laborers - farmers, fisherman, lumberjacks - machinery such as tractors, hydraulics and chainsaws now shoulder a lot of the work. As physical strength becomes less necessary, our muscles will keep shrinking.

Our jaws and teeth also got smaller. Early, plant-eating hominins had huge molars and mandibles for grinding fibrous vegetables. As we shifted to meat, then started cooking food, jaws and teeth shrank . Modern processed food – chicken nuggets, Big Macs, cookie dough ice cream – needs even less chewing, so jaws will keep shrinking, and we’ll likely lose our wisdom teeth.

After people left Africa 100,000 years ago, humanity’s far-flung tribes became isolated by deserts, oceans, mountains, glaciers and sheer distance. In various parts of the world, different selective pressures – different climates, lifestyles and beauty standards – caused our appearance to evolve in different ways. Tribes evolved distinctive skin colour, eyes, hair and facial features.

With civilisation’s rise and new technologies, these populations were linked again. Wars of conquest, empire building, colonisation and trade – including trade of other humans – all shifted populations, which interbred. Today, road, rail and aircraft link us too. Bushmen would walk 40 miles to find a partner; we’ll go 4,000 miles. We’re increasingly one, worldwide population – freely mixing. That will create a world of hybrids – light brown skinned, dark-haired, Afro-Euro-Australo-Americo-Asians, their skin colour and facial features tending toward a global average.

Sexual selection will further accelerate the evolution of our appearance. With most forms of natural selection no longer operating, mate choice will play a larger role. Humans might become more attractive, but more uniform in appearance. Globalised media may also create more uniform standards of beauty, pushing all humans towards a single ideal. Sex differences, however, could be exaggerated if the ideal is masculine-looking men and feminine-looking women.

Intelligence and personality

Last, our brains and minds, our most distinctively human feature, will evolve, perhaps dramatically. Over the past 6 million years, hominin brain size roughly tripled , suggesting selection for big brains driven by tool use, complex societies and language. It might seem inevitable that this trend will continue, but it probably won’t.

Instead, our brains are getting smaller . In Europe, brain size peaked 10,000—20,000 years ago, just before we invented farming . Then, brains got smaller. Modern humans have brains smaller than our ancient predecessors, or even medieval people. It’s unclear why.

It could be that fat and protein were scarce once we shifted to farming, making it more costly to grow and maintain large brains. Brains are also energetically expensive – they burn around 20% of our daily calories. In agricultural societies with frequent famine, a big brain might be a liability.

Maybe hunter-gatherer life was demanding in ways farming isn’t. In civilisation, you don’t need to outwit lions and antelopes, or memorise every fruit tree and watering hole within 1,000 square miles. Making and using bows and spears also requires fine motor control, coordination, the ability to track animals and trajectories — maybe the parts of our brains used for those things got smaller when we stopped hunting.

Or maybe living in a large society of specialists demands less brainpower than living in a tribe of generalists. Stone-age people mastered many skills – hunting, tracking, foraging for plants, making herbal medicines and poisons, crafting tools, waging war, making music and magic. Modern humans perform fewer, more specialised roles as part of vast social networks, exploiting division of labour. In a civilisation, we specialise on a trade, then rely on others for everything else .

That being said, brain size isn’t everything: elephants and orcas have bigger brains than us, and Einstein’s brain was smaller than average . Neanderthals had brains comparable to ours, but more of the brain was devoted to sight and control of the body , suggesting less capacity for things like language and tool use. So how much the loss of brain mass affects overall intelligence is unclear. Maybe we lost certain abilities, while enhancing others that are more relevant to modern life. It’s possible that we’ve maintained processing power by having fewer, smaller neurons. Still, I worry about what that missing 10% of my grey matter did.

Curiously, domestic animals also evolved smaller brains . Sheep lost 24% of their brain mass after domestication; for cows, it’s 26%; dogs, 30%. This raises an unsettling possibility. Maybe being more willing to passively go with the flow (perhaps even thinking less), like a domesticated animal, has been bred into us, like it was for them.

Our personalities must be evolving too. Hunter-gatherers’ lives required aggression. They hunted large mammals, killed over partners and warred with neighbouring tribes . We get meat from a store, and turn to police and courts to settle disputes. If war hasn’t disappeared, it now accounts for fewer deaths , relative to population, than at any time in history. Aggression, now a maladaptive trait, could be bred out.

Changing social patterns will also change personalities. Humans live in much larger groups than other apes, forming tribes of around 1,000 in hunter-gatherers. But in today’s world people living in vast cities of millions. In the past, our relationships were necessarily few, and often lifelong. Now we inhabit seas of people, moving often for work, and in the process forming thousands of relationships, many fleeting and, increasingly, virtual. This world will push us to become more outgoing, open and tolerant. Yet navigating such vast social networks may also require we become more willing to adapt ourselves to them – to be more conformist.

Not everyone is psychologically well-adapted to this existence. Our instincts, desires and fears are largely those of stone-age ancestors, who found meaning in hunting and foraging for their families, warring with their neighbours and praying to ancestor-spirits in the dark. Modern society meets our material needs well, but is less able to meet the psychological needs of our primitive caveman brains.

Perhaps because of this, increasing numbers of people suffer from psychological issues such as loneliness , anxiety and depression. Many turn to alcohol and other substances to cope. Selection against vulnerability to these conditions might improve our mental health, and make us happier as a species. But that could come at a price. Many great geniuses had their demons; leaders like Abraham Lincoln and Winston Churchill fought with depression, as did scientists such as Isaac Newton and Charles Darwin, and artists like Herman Melville and Emily Dickinson. Some, like Virginia Woolf, Vincent Van Gogh and Kurt Cobain, took their own lives. Others - Billy Holliday, Jimi Hendrix and Jack Kerouac – were destroyed by substance abuse.

A disturbing thought is that troubled minds will be removed from the gene pool – but potentially at the cost of eliminating the sort of spark that created visionary leaders, great writers, artists and musicians. Future humans might be better adjusted – but less fun to party with and less likely to launch a scientific revolution — stable, happy and boring.

New species?