Personal Health Change Autobiography Essay

Introduction, chosen healthy behavior, reasons for making this health change, challenges likely to be faced, ways of overcoming the challenges, benefits of healthy behavior.

Improving the quality of one’s life is imperative in the present century. Education, establishment of more employment opportunities and private health in life are among the objectives which self-gratify an individual. The lifestyles individuals are accustomed to and their environment impact healthy behavior.

However, there are several ways of improving personal health, which may at times present challenges in their implementation. The benefits of most of these healthy behaviors nevertheless obscure the impediments which are faced.

I would like to exercise more routinely (5-7 times a week), while trying to develop a nutritional plan. This calls for having a meaningful vision and acquiring skills necessary to achieve the desired wellness. Physical activity, aerobics and muscle training are some of the divisions of exercise which include a painless 20 minute walk to an intensified work out in the gym.

Dancing and engaging in a physical sport like basketball or tennis is also forms of indirect exercise. The beauty of some exercises is that they do not necessarily involve a routine. Walking, for example, may be administered whenever an opportunity carves itself out.

These forms of physical activity stimulate hormones which are necessary for proper growth. Its other benefits like feeling and looking better lift composure and improves character, traits which are critical in the normal human socialization process. Using the stairs instead of the elevator and cycling to work are other valuable processes which are not that hard to achieve.

My main focus will be engaging in exercise, but I will also try maintaining a good diet. My nutritional project involves taking more fruits and vegetables and avoiding junk food which usually has a lot of fat. I have thought out turning into vegetarianism, but it has proven to yield more challenges than benefits, so I will prefer adding more vitamins in my diet.

Health is not just about whether a person is challenged by a disease. I chose to make this condition change in order to further my physical, social and emotional well being. Physical activities help reduce weight and promote better sleep regardless of age or masculinity. I would like to reduce 30 pounds that I am overweight, and while keeping a diet may be forceful and not so feasible, employing straightforward exercise strategies will be my first choice of a health change.

Being proud of my physique would significantly assist in developing the social interactions I want. The observations I have made on the behavior of overweight students in school is not so attractive. They tend to cluster together and receive taunting comments, which lower their faith in life. I want to make a health change in order to maintain satisfactory relationships with my present friends and be able to communicate confidently with others.

Emotional support and the behavior other people rally will unquestionably present a challenge. Close friends and associations will play a central role in influencing my training schedule and the diet I intend to maintain. Group activities would thus cease, because my schedule will need individual effort without distractions. However, the greatest challenge will be choosing the most appropriate exercise to practice regularly. It would be essential to have a regular plan if I am to achieve my objectives.

Scheduling, discipline and determination will be the factors considered in choosing an applicable practice. It would be useless reasonably to engage in a strenuous muscle application and put in lots of hours in the gym only to give up after a week. Making the decision would be exceedingly difficult, considering I have not engaged in any practical exercise for a while.

Time will also be an obstacle as I am significantly engaged with either homework or domestic duties. Whenever one gets busy, the time delegated for work-outs is usually sacrificed.

I have reviewed specific medical articles, and the negative impacts of exercise others have experienced significantly scare me off. There are those who experience colds or running noses in the middle of training sessions. Other trainers complain about breathing problems and splitting headaches after sessions. Experiencing no changes as soon as they expect them will prove frustrating. In case the practice I employ does not yield visible results within the first month, then I may change the form of exercise or plainly relinquish.

My present physical condition demands for regular exercise notwithstanding the challenges I would face. I have high cholesterol for a young 25 year old, so in order to live longer and healthier, I have to take part in some form of physical activity. The bigger one gets, the harder it would be to practice some routines. I would be thus required to complete a substantial health change before I start suffering unnecessary mortifications.

Exercise is usually strenuous and may involve a lot of wearisome activity. This will prove boring and I predict avoiding some responsibilities. However, devising methods to make it enjoyable would be meaningful. Exercising while having fun would unquestionably inspire me in the initiative to improve health.

I consider doing my exercises at home through the use of exercise videos. This will reduce the uncomfortable situations experienced in gyms which may make one uncomfortable. The use of some complex machines may also reduce the esteem of an individual.

Setting realistic fitness goals would be required depending on the pattern of physical activity. Studies indicate that most forms of practice would require consistency for around four months before producing physical benefits. It would be required to understand how different techniques work, how long they take to present visible or mental results, and how best to preserve the process.

The cholesterol issue will go away; I will look healthier and sexier and will have a strong body just like in high school, and will live longer. Having a fit body, proper posture, agility and muscles will transparently create the impact I desire with the opposite sex. Engaging in physical activity will help me burn the extra calories hence assist in the supervision of my weight, which is a considerable problem at present.

Physical activity improves concentration; any activity, which involves attentiveness, boosts the psychiatric process hence increasing sharpness and academic focus both in class and later years. Strength is also increased substantially when one specializes in meticulous work-outs of the muscles and stiff joints.

Proper combination of healthful food and appropriate muscles training has traditionally proven to increase the endurance of people. A chance of catching a cold is substantially reduced as the immune system is generally jump-started by regular exercises.

Exercising and eating healthy have been proven to progress physical health. Nevertheless, there are several other minor details which affect people’s healthiness. Personal hygiene and social participation have traditionally fostered health in diverse ways. Keeping one’s body clean to thwart illnesses and avoid infections is imperative. Cleaning hands, brushing teeth, cleaning cutlery helps in preventing infections.

One should strive to avoid the appearance of microbes in the body. Establishing social relationships prolongs life and increases productivity and positivism in life. Socialization may also increase knowledge, develop character and make an individual significantly healthy.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, July 5). Personal Health Change. https://ivypanda.com/essays/personal-health-change/

"Personal Health Change." IvyPanda , 5 July 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/personal-health-change/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'Personal Health Change'. 5 July.

IvyPanda . 2018. "Personal Health Change." July 5, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/personal-health-change/.

1. IvyPanda . "Personal Health Change." July 5, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/personal-health-change/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Personal Health Change." July 5, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/personal-health-change/.

- Safety of Silver’s Gym

- Going to the Gym: What Health Effects to Expect

- David Barton Gym’s Marketing and Communication

- HIV/AIDS Issues in African Women

- Smoking and Its Negative Effects on Human Beings

- Ethnic Disparities in Women's Health Care

- Langley Park: Public Health Services

- Importance of Nutrition and Exercise in the Society

Using these brief interventions, you can help your patients make healthy behavior changes.

STEPHANIE A. HOOKER, PHD, MPH, ANJOLI PUNJABI, PHARMD, MPH, KACEY JUSTESEN, MD, LUCAS BOYLE, MD, AND MICHELLE D. SHERMAN, PHD, ABPP

Fam Pract Manag. 2018;25(2):31-36

Author disclosures: no relevant financial affiliations disclosed.

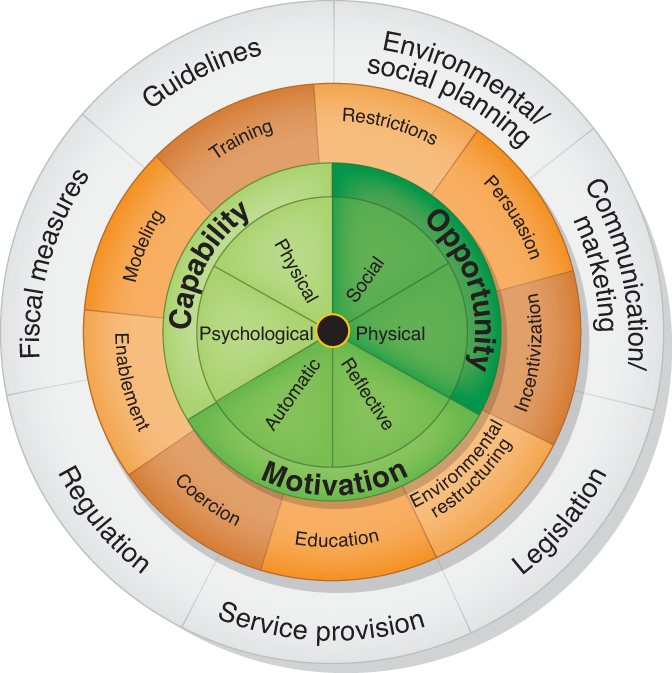

Effectively encouraging patients to change their health behavior is a critical skill for primary care physicians. Modifiable health behaviors contribute to an estimated 40 percent of deaths in the United States. 1 Tobacco use, poor diet, physical inactivity, poor sleep, poor adherence to medication, and similar behaviors are prevalent and can diminish the quality and length of patients' lives. Research has found an inverse relationship between the risk of all-cause mortality and the number of healthy lifestyle behaviors a patient follows. 2

Family physicians regularly encounter patients who engage in unhealthy behaviors; evidence-based interventions may help patients succeed in making lasting changes. This article will describe brief, evidence-based techniques that family physicians can use to help patients make selected health behavior changes. (See “ Brief evidence-based interventions for health behavior change .”)

Modifiable health behaviors, such as poor diet or smoking, are significant contributors to poor outcomes.

Family physicians can use brief, evidence-based techniques to encourage patients to change their unhealthy behaviors.

Working with patients to develop health goals, eliminate barriers, and track their own behavior can be beneficial.

Interventions that target specific behaviors, such as prescribing physical activity for patients who don't get enough exercise or providing patient education for better medication adherence, can help patients to improve their health.

CROSS-BEHAVIOR TECHNIQUES

Although many interventions target specific behaviors, three techniques can be useful across a variety of behavioral change endeavors.

“SMART” goal setting . Goal setting is a key intervention for patients looking to make behavioral changes. 3 Helping patients visualize what they need to do to reach their goals may make it more likely that they will succeed. The acronym SMART can be used to guide patients through the goal-setting process:

Specific. Encourage patients to get as specific as possible about their goals. If patients want to be more active or lose weight, how active do they want to be and how much weight do they want to lose?

Measurable. Ensure that the goal is measurable. For how many minutes will they exercise and how many times a week?

Attainable. Make sure patients can reasonably reach their goals. If patients commit to going to the gym daily, how realistic is this goal given their schedule? What would be a more attainable goal?

Relevant. Ensure that the goal is relevant to the patient. Why does the person want to make this change? How will this change improve his or her life?

Timely. Help patients define a specific timeline for the goal. When do they want to reach their goal? When will you follow-up with them? Proximal, rather than distal, goals are preferred. Helping patients set a goal to lose five pounds in the next month may feel less overwhelming than a goal of losing 50 pounds in the next year.

Problem-solving barriers . Physicians may eagerly talk with patients about making changes — only to become disillusioned when patients do not follow through. Both physicians and patients may grow frustrated and less motivated to work on the problem. One way to prevent this common phenomenon and set patients up for success is to brainstorm possible obstacles to behavior change during visits.

After offering a suggestion or co-creating a plan, physicians can ask simple, respectful questions such as, “What might get in the way of your [insert behavior change]?” or “What might make it hard to [insert specific step]?” Physicians may anticipate some common barriers raised by patients but be surprised by others. Once the barriers are defined, the physician and patient can develop potential solutions, or if a particular barrier cannot be overcome, reevaluate or change the goal. This approach can improve clinical outcomes for numerous medical conditions and for patients of various income levels. 4

For example, a patient wanting to lose weight may commit to regular short walks around the block. Upon further discussion, the patient shares that the cold Minnesota winters and the violence in her neighborhood make walking in her area difficult. The physician and patient may consider other options such as walking around a local mall or walking with a family member instead. Anticipating every barrier may be impossible, and the problem-solving process may unfold over several sessions; however, exploring potential challenges during the initial goal setting can be helpful.

Self-monitoring . Another effective strategy for facilitating a variety of behavioral changes involves self-monitoring, defined as regularly tracking some specific element of behavior (e.g., minutes of exercise, number of cigarettes smoked) or a more distal outcome (e.g., weight). Having patients keep diaries of their behavior over a short period rather than asking them to remember it at a visit can provide more accurate and valuable data, as well as provide a baseline from which to track change.

When patients agree to self-monitor their behavior, physicians can increase the chance of success by discussing the specifics of the plan. For example, at what time of day will the patient log his or her behavior? How will the patient remember to observe and record the behavior? What will the patient write on the log? Logging the behavior soon after it occurs will provide the most accurate data. Although patients may be tempted to omit unhealthy behaviors or exaggerate healthy ones, physicians should encourage patients to be completely honest to maximize their records' usefulness. For self-monitoring to be most effective, physicians should ask patients to bring their tracking forms to follow-up visits, review them together, celebrate successes, discuss challenges, and co-create plans for next steps. (Several diary forms are available in the Patient Handouts section of the FPM Toolbox .)

A variety of digital tracking tools exist, including online programs, smart-phone apps, and smart-watch functions. Physicians can help patients select which method is most convenient for daily use. Most online programs can present data in charts or graphs, allowing patients and physicians to easily track change over time. SuperTracker , a free online program created by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, helps patients track nutrition and physical activity plans, set goals, and work with a group leader or coach. Apps like Lose It! or MyFitnessPal can also help.

The process of consistently tracking one's behavior is sometimes an intervention itself, with patients often sharing that it created self-reflection and resulted in some changes. Research shows self-monitoring is effective across several health behaviors, especially using food intake monitoring to produce weight loss. 5

BEHAVIOR-SPECIFIC TECHNIQUES

The following evidence-based approaches can be useful in encouraging patients to adopt specific health behaviors.

Physical activity prescriptions . Many Americans do not engage in the recommended amounts of physical activity, which can affect their physical and psychological health. Physicians, however, rarely discuss physical activity with their patients. 6 Clinicians ought to act as guides and work with patients to develop personalized physical activity prescriptions, which have the potential to increase patients' activity levels. 7 These prescriptions should list creative options for exercise based on the patient's experiences, strengths, values, and goals and be adapted to a patient's condition and treatment goals over time. For example, a physician working with a patient who has asthma could prescribe tai chi to help the patient with breathing control as well as balance and anxiety.

In creating these prescriptions, physicians should help the patient recognize the personal benefits of physical activity; identify barriers to physical activity and how to overcome them; set small, achievable goals; and give patients the confidence to attempt their chosen activity. Physicians should also put the prescriptions in writing, give patients logs to track their activity, and ask them to bring those logs to follow-up appointments for further discussion and coaching. 8 More information about exercise prescriptions and sample forms are available online.

Healthy eating goals . Persuading patients to change their diets is daunting enough without unrealistic expectations and the constant bombardment of fad diets, cleanses, fasts, and other food trends that often leave both patients and physicians uncertain about which food options are actually healthy. Moreover, physicians in training receive little instruction on what constitutes sound eating advice and ideal nutrition. 9 This confusion can prevent physicians from broaching the topic with patients. Even if they identify healthy options, common setbacks can leave both patients and physicians less motivated to readdress the issue. However, physicians can help patients set realistic healthy eating goals using two simple methods:

Small steps. Studies have shown that one way to combat the inertia of unhealthy eating is to help patients commit to small, actionable, and measurable steps. 10 First, ask the patient what small change he or she would like to make — for example, decrease the number of desserts per week by one, eat one more fruit or vegetable serving per day, or swap one fast food meal per week with a homemade sandwich or salad. 11 Agree on these small changes to empower patients to take control of their diets.

The Plate Method. This model of meal design encourages patients to visualize their plates split into the following components: 50 percent fruits and non-starchy vegetables, 25 percent protein, and 25 percent grains or starchy foods. 12 Discuss healthy options that would fit in each of the categories, or combine this method with the small steps described above. By providing a standard approach that patients can adapt to many forms of cuisine, the model helps physicians empower their patients to assess their food options and adopt healthy eating behaviors.

Brief behavioral therapy for insomnia . Many adults struggle with insufficient or unrestful sleep, and approximately 18.8 percent of adults in the United States meet the criteria for an insomnia disorder. 13 The first-line treatment for insomnia is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I), which involves changing patients' behaviors and thoughts related to their sleep and is delivered by a trained mental health professional. A physician in a clinic visit can easily administer shorter versions of CBT-I, such as Brief Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (BBT-I). 14 BBT-I is a structured therapy that includes restricting the amount of time spent in bed but not asleep and maintaining a regular sleep schedule from night to night. Here's how it works:

Sleep diary. Have patients maintain a sleep diary for two weeks before starting the treatment. Patients should track when they got in bed, how long it took to fall asleep, how frequently they woke up and for how long, what time they woke up for the day, and what time they got out of bed. Many different sleep diaries exist, but the American Academy of Sleep Medicine's version is especially user-friendly.

Education. In the next clinic appointment, briefly explain how the body regulates sleep. This includes the sleep drive (how the pressure to sleep is based on how long the person has been awake) and circadian rhythms (the 24-hour biological clock that regulates the sleep-wake cycle).

Set a wake-up time. Have patients pick a wake-up time that will work for them every day. Encourage them to set an alarm for that time and get up at that time every day, no matter how the previous night went.

Limit “total time in bed.” Review the patient's sleep diary and calculate the average number of hours per night the patient slept in the past two weeks. Add 30 minutes to that average and explain that the patient should be in bed only for that amount of time per night until your next appointment.

Set a target bedtime. Subtract the total time in bed from the chosen wake-up time, and encourage patients to go to bed at that “target” time only if they are sleepy and definitely not any earlier.

For example, if a patient brings in a sleep diary with an average of six hours of sleep per night for the past two weeks, her recommended total time in bed will be 6.5 hours. If she picks a wake-up time of 7 a.m., her target bedtime would be 12:30 a.m. It usually takes up to three weeks of regular sleep scheduling and sleep restriction for patients to start seeing improvements in their sleep. As patients' sleep routines become more solid (i.e., they are falling asleep quickly and sleeping more than 90 percent of the time they are in bed), slowly increase the total time in bed to possibly increase time asleep. Physicians should encourage patients to increase time in bed in increments of 15 to 30 minutes per week until the ideal amount of sleep is reached. This amount is different for each patient, but patients generally have reached their ideal amount of sleep when they are sleeping more than 85 percent of the time in bed and feel rested during the day.

Patient education to prevent medication nonadherence . Medication adherence can be challenging for many patients. In fact, approximately 20 percent to 30 percent of prescriptions are never picked up from the pharmacy, and 50 percent of medications for chronic diseases are not taken as prescribed. 15 Nonadherence is associated with poor therapeutic outcomes, further progression of disease, and decreased quality of life. To help patients improve medication adherence, physicians must determine the reason for nonadherence. The most common reasons are forgetfulness, fear of side effects, high drug costs, and a perceived lack of efficacy. To help patients change these beliefs, physicians can take several steps:

Educate patients on four key aspects of drug therapy — the reason for taking it (indication), what they should expect (efficacy), side effects and interactions (safety), and how it structurally and financially fits into their lifestyle (convenience). 16

Help patients make taking their medication a routine of their daily life. For example, if a patient needs to use a controller inhaler twice daily, recommend using the inhaler before brushing his or her teeth each morning and night. Ask patients to describe their day, including morning routines, work hours, and other responsibilities to find optimal opportunities to integrate this new behavior.

Ask patients, “Who can help you manage your medications?” Social networks, including family members or close friends, can help patients set up pillboxes or provide medication reminders.

The five Rs to quitting smoking . Despite the well-known consequences of smoking and nationwide efforts to reduce smoking rates, approximately 15 percent of U.S. adults still smoke cigarettes. 17 As with all kinds of behavioral change, patients present in different stages of readiness to quit smoking. Motivational interviewing techniques can be useful to explore a patient's ambivalence in a way that respects his or her autonomy and bolsters self-efficacy. Discussing the five Rs is a helpful approach for exploring ambivalence with patients: 18

Relevance. Explore why quitting smoking is personally relevant to the patient.

Risks. Advise the patient on negative consequences of continuing to smoke.

Rewards. Ask the patient to identify the benefits of quitting smoking.

Roadblocks. Help the patient determine obstacles he or she may face when quitting. Common barriers include weight gain, stress, fear of withdrawal, fear of failure, and having other smokers such as coworkers or family in close proximity.

Repeat. Incorporate these aspects into each clinical contact with the patient.

Many patients opt to cut back on the amount of tobacco they use before their quit date. However, research shows that cutting back on the number of cigarettes is no more effective than quitting abruptly, and setting a quit date is associated with greater long-term success. 19

Once the patient sets a quit date, repeated physician contact to reinforce smoking cessation messages is key. Physicians, care coordinators, or clinical staff should consider calling or seeing the patient within one to three days of the quit date to encourage continued efforts to quit, as this time period has the highest risk for relapse. Evidence shows that contacting the patient four or more times increases the success rate in staying abstinent. 18 Quitting for good may take multiple a empts, but continued encouragement and efforts such as setting new quit dates or offering other pharmacologic and behavioral therapies can be helpful.

GETTING STARTED

Family physicians are uniquely positioned to provide encouragement and evidence-based advice to patients to change unhealthy behaviors. The proven techniques described in this article are brief enough to attempt during clinic visits. They can be used to encourage physical activity, healthy eating, better sleep, medication adherence, and smoking cessation, and they can help patients adjust their lifestyle, improve their quality of life, and, ultimately, lower their risk of early mortality.

Loef M, Walach H. The combined effects of healthy lifestyle behaviors on all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med . 2012;55(3):163-170.

Bodenheimer T, Handley MA. Goal-setting for behavior change in primary care: an exploration and status report. Patient Educ Couns . 2009;76(2):174-180.

Lilly CL, Bryant LL, Leary JM, et al.; Evaluation of the effectiveness of a problem-solving intervention addressing barriers to cardiovascular disease prevention behaviors in three underserved populations: Colorado, North Carolina, West Virginia, 2009. Prev Chronic Dis . 2014;11:E32.

U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans (7th Ed). Washington, D.C: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2010.

Sreedhara M, Silfee VJ, Rosal MC, Waring ME, Lemon SC. Does provider advice to increase physical activity differ by activity level among U.S. adults with cardiovascular disease risk factors? Fam Pract . 2018;35(4):420-425.

Pinto BM, Lynn H, Marcus BH, DePue J, Goldstein MG. Physician-based activity counseling: intervention effects on mediators of motivational readiness for physical activity. Ann Behav Med . 2001;23(1):2-10.

Hechanova RL, Wegler JL, Forest CP. Exercise: a vitally important prescription. JAAPA . 2017;30(4):17-22.

Guo H, Pavek M, Loth K. Management of childhood obesity and overweight in primary care visits: gaps between recommended care and typical practice. Curr Nutr Rep . 2017;6(4):307-314.

Perkins-Porras L, Cappuccio FP, Rink E, Hilton S, McKay C, Steptoe A. Does the effect of behavioral counseling on fruit and vegetable intake vary with stage of readiness to change?. Prev Med . 2005;40(3):314-320.

Kahan S, Manson JE. Nutrition counseling in clinical practice: how clinicians can do better. JAMA . 2017;318(12):1101-1102.

Choose My Plate. U.S. Department of Agriculture website. https://www.choosemyplate.gov/ . Updated January 31, 2018. Accessed February 1, 2018.

Ford ES, Cunningham TJ, Giles WH, Croff JB. Trends in insomnia and excessive daytime sleepiness among U.S. adults from 2002 to 2012. Sleep Med . 2015;16(3):372-378.

Edinger JD, Sampson WS. A primary care “friendly” cognitive behavioral insomnia therapy. Sleep . 2003;26(2):177-182.

Viswanathan M, Golin CE, Jones CD, et al.; Interventions to improve adherence to self-administered medications for chronic diseases in the United States: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med . 2012;157(11):785-795.

Cipolle RJ, Strand LM, Morley PC. Pharmaceutical care practice: the patient-centered approach to medication management services . 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

Jamal A, King BA, Neff LJ, Whitmill J, Babb SD, Graffunder CM. Current cigarette smoking among adults — United States, 2005–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep . 2016;65(44):1205-1211.

Patients not ready to make a quit attempt now (the “5 Rs”). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality website. http://bit.ly/2jVvpoY . Updated December 2012. Accessed February 2, 2018.

Larzelere MM, Williams DE. Promoting smoking cessation. Am Fam Physician . 2012;85(6):591-598.

Continue Reading

More in FPM

More in pubmed.

Copyright © 2018 by the American Academy of Family Physicians.

This content is owned by the AAFP. A person viewing it online may make one printout of the material and may use that printout only for his or her personal, non-commercial reference. This material may not otherwise be downloaded, copied, printed, stored, transmitted or reproduced in any medium, whether now known or later invented, except as authorized in writing by the AAFP. See permissions for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

Copyright © 2024 American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

24 Health Behavior Change

Ralf Schwarzer is a professor in the Department of Psychology at Freie Universitat Berlin in Berlin, Germany.

- Published: 18 September 2012

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

An overview of theoretical constructs and mechanisms of health behavior change is provided, based on a self-regulation framework that makes a distinction between goal setting and goal pursuit. Risk perception, outcome expectancies, and task self-efficacy are seen as predisposing factors in the goal setting phase (motivational phase), whereas planning, action control, and maintenance/recovery self-efficacy are regarded as influential in the goal pursuit phase (volitional phase). The first phase leads to forming an intention, and the second phase leads to actual behavior change. Such a mediator model serves to explain social-cognitive processes in health behavior change. Adding a second layer on top of it, a moderator model is provided in which three stages are distinguished to segment the audience for tailored interventions. Identifying persons as preintenders, intenders, or actors offers an opportunity to match theory-based treatments to specific target groups. Research examples serve to illustrate the application of the model to health promotion.

Many health conditions are caused by risk behaviors, such as problem drinking, substance use, smoking, reckless driving, overeating, or unprotected sexual intercourse. The key question in health behavior research is how to predict and modify the adoption and maintenance of health behaviors. Fortunately, human beings have, in principle, control over their conduct. Health-compromising behaviors can be eliminated by self-regulatory efforts, and health-enhancing behaviors can be adopted instead, such as physical exercise, weight control, preventive nutrition, dental hygiene, condom use, or accident prevention. Health self-regulation refers to the motivational, volitional, and actional processes of abandoning such health-compromising behaviors in favor of adopting and maintaining health-enhancing behaviors (Leventhal, Weinman, Leventhal, & Phillips, 2008 ).

This chapter highlights some current issues in health behavior research. In the first section, various psychological constructs are described that have been found useful. These are intention, risk perception, outcome expectancies, perceived self-efficacy, and planning. In the second section, theoretical perspectives on the health behavior change process are discussed. From a metatheoretical viewpoint, stage models are contrasted to continuum models. Following is one example of a continuum model (theory of planned behavior) and one example of a stage model (transtheoretical model). Then a two-layer hybrid framework is introduced (health action process approach). In the third section, some unresolved issues in health behavior research are discussed. All sections are illustrated by research findings and suggestions for further research.

Constructs and Principles

Intention, motivation, volition.

Changes in health behaviors can be influenced by opportunities and barriers, by explicit decisions, or by random events. In this chapter, we are dealing solely with intentional changes that happen when people become motivated to alter their previous way of life and set goals for a different course of action. For example, they may consider to quit smoking, or they make an effort to do so. Thus, intention represents a key factor in health behavior change. This construct had been suggested by Fishbein and Ajzen ( 1975 ) to operate as a mediator to overcome the attitude–behavior gap. Since behaviors could not be well predicted by attitudes, intention appeared to be a useful mediator and a better proximal predictor of many behaviors. Since then, there is consensus that intention is an indispensable variable when it comes to explaining and predicting behaviors. In the process of motivation, intention has been regarded as a kind of “watershed” between an initial goal setting phase and a subsequent goal pursuit phase. Lewin, Dembo, Festinger, and Sears ( 1944 ) described a motivation phase of goal setting that is followed by a volition phase of goal pursuit. This distinction has been elaborated and called the Rubicon model by Heckhausen ( 1980 , 1991 ), Heckhausen and Gollwitzer ( 1987 ), and Kuhl ( 1983 ). Motivation is a preintentional process, whereas volition refers to a postintentional process. When describing health behavior change, it is most helpful to follow this distinction. For example, to gauge the progress of an individual who is supposed to quit smoking and to design therapeutic interventions, the first question to ask should be whether this person is either preintentional or postintentional. To which degree is the person motivated (goal setting), or to which degree is the person making explicit efforts to quit (goal pursuing)? The terms motivation and goal setting pertain to the preintentional phase, whereas the terms volition and goal pursuit pertain to the postintentional phase. These distinctions will be discussed in more detail in the section on stage models.

Although the construct of intention is indispensable in explaining health behavior change, its predictive value is limited (Schwarzer, 1992 ; Sheeran, 2002 ). When trying to translate intentions into behavior, individuals are faced with various obstacles, such as distractions, forgetting, or conflicting bad habits. Godin and Kok ( 1996 ), who reviewed 19 studies, found a mean correlation of .46 between intention and health behavior, such as exercise, screening attendance, and addictions. Abraham and Sheeran ( 2000 ) reported behavioral intention measures to account for 20%–25% of the variance in health behavior measures. If not equipped with means to meet these obstacles, motivation alone does not suffice to change behavior (Baumeister, Heatherton & Tice, 1994 ). To overcome this limitation, further constructs are required that operate in concert with the intention. Volitional factors can help to bridge the intention–behavior gap (Sheeran, 2002 ) since people do not fully act upon their intentions (e.g., Abraham, Sheeran, & Johnston, 1998 ). Implementation intentions are one such volitional factor (Gollwitzer, 1999 ) that can be interpreted as postintentional mental simulation or planning strategies. A detailed discussion follows below in the section on planning.

A concept related to intention is behavioral willingness (Gibbons & Gerrard, 1997 ; Gibbons, Gerrard, & Lane, 2003 ). The authors believe that health-compromising behavior is often not intentional, but is rather a spontaneous reaction to social circumstances. Gibbons and Gerrard define behavioral willingness as an openness to risk opportunity (i.e., what an individual would be willing to do under certain circumstances).

Risk Perception

At first glance, perceiving a health threat seems to be the most obvious prerequisite for the motivation to overcome a risk behavior (e.g., smoking). Consequently, a central task for health communication is not only to provide information about the existence and magnitude of a certain risk, but also to increase the subjective relevance of a health issue to focus the individuals’ attention on information pertaining directly to their own risk. However, general perceptions of risk (e.g., “Smoking is dangerous”) and personal perceptions of risk (e.g., “I am at risk because I am a smoker”) often differ to a great extent. Individuals could be well informed about general aspects of certain risks and precautions (e.g., most smokers acknowledge that smoking can cause diseases), but, nevertheless, many might not feel personally at risk (Klein & Cerully, 2007 ).

Especially when it comes to a comparison with similar others, one’s view of the risk is somewhat distorted (see Suls, 2011 , Chapter 12 , this volume). On average, individuals tend to see themselves as being less likely than others to experience health problems in the future. For example, when asked how they judge their risk of becoming infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) compared to an average peer of the same sex and age (the average risk ), participants typically give a below-average estimate (e.g., Hahn & Renner, 1998 ). This has been coined “unrealistic optimism” or “optimistic bias” (Weinstein, 1980 , 1988 ). It reflects the difference between the perceived risk for oneself and that for others, belonging to the broader construct of defensive optimism (Taylor & Brown, 1994 ).

Defensive optimism represents an underestimation of risk that hinders the adoption of precautionary behaviors, whereas functional optimism promotes their adoption (Radcliffe & Klein, 2002 ; Schwarzer, 1994 ). People who are optimistic may be so in two ways: They underestimate risks, but are optimistic about their capability to overcome their bad habits. Since both kinds of optimism are confounded, risk perceptions are often poor predictors of behavior.

People with a high-risk status (e.g., high blood pressure, obesity, and high cholesterol) should perceive a higher pressure to act, and they are more inclined to form an intention to change their habits than are people who are not at risk (cf. Croyle, Sun, & Louie, 1993 ; Renner, 2004 ). The actual risk status should be related to perceived risk for future health problems and diseases. However, the relationship between current objective risk status and risk perception varies considerably, suggesting that they might contribute differently to intention forming.

Renner and Schwarzer ( 2005 ) found that objective risk predicted risk perception, but the latter did not translate into an intention to eat a healthy diet. Thus, risk communication might be a dead end, resulting in higher risk perception, but not leading to intention formation. The relation between objective risk status, risk perception, and risk behavior is still not well understood and represents a challenge for further research (Brewer, Weinstein, Cuite, & Herrington, 2004 ; Panzer & Renner, 2008 ). Both the objective and subjective risk may not be functional for health behavior change if not accompanied by other motivational and volitional factors.

An example for the ambiguous role of fear appeals in health promotion is the current debate on the introduction of graphic warning labels on cigarette packs. Although good research on fear appeals has been published for half a century (e.g., Leventhal, Singer, & Jones, 1965 ), public health agents seem to be unaware of the psychological mechanisms that are involved in risk communication. Some epidemiological studies provide evidence for the effectiveness of graphic warning labels. However, this kind of evidence is methodologically weak because studies are nonexperimental and do not allow for causal inferences. Typically, in such studies telephone interviews are conducted based on random-digit dialing, and a subsample of volunteers report about reading warning labels and what they believe is the impact on their intentions not to smoke, and eventually, on their attempts at quitting. It can be assumed that respondents constitute a positive selection of intenders or contemplators who are interested in the topic, and who consider quitting anyway. Such studies are typically not guided by health behavior theories but are rather data driven. It is indeed very hard to collect valid data on this issue because there might be no good way to design a randomized controlled trial. Experimental work on risk communication mainly takes place in the laboratory, where internal validity is high, but external (ecological) validity is low. One such experiment was recently conducted to investigate the impact of cigarette warning labels on cognitive dissonance in smokers. Smokers’ and nonsmokers’ risk perceptions with regard to smoking-related diseases were measured with response latencies before and after presentation of warning labels. Responses showed an impact of confrontation with smoking-related health risks rather than an impact of warning labels themselves.

The adoption of health behaviors should not be viewed simplistically as a response to a health threat. Risk information alone does not help people to change risky behaviors because it does not provide meaningful information about how to manage behavioral changes. Initial risk perception seems to be advantageous in helping people become motivated to change, but later, other factors are more influential in the self-regulation process. This state of affairs has encouraged health psychologists to design more complex models that combine risk perception with other determinants and processes of change.

Outcome Expectancies

In addition to being aware of a health threat, people also need to know how to regulate their behavior. They need to understand the links between actions and subsequent outcomes. These outcome expectancies can be the most influential beliefs in the motivation to change. The term outcome expectancies is most common in social-cognitive theory (Bandura, 1997 ). The equivalent terms pros and cons are used in the transtheoretical model (Prochaska & Velicer, 1997 ), in which they represent the decisional balance in people who are contemplating whether to adopt a novel behavior or not. In the theory of reasoned action (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975 ), the corresponding term is behavioral beliefs that act as precursors of attitudes.

The pros and cons represent positive and negative outcome expectancies. A smoker may find more good reasons to quit (“If I quit smoking, then my friend will like me much more”) than reasons to continue smoking (“If I quit, I will become more tense and irritated”). This imbalance in favor of positive outcome expectancies will not lead directly to action, but it can help to generate the intention to quit. Outcome expectancies can also be understood as means–ends relationships, indicating that people know proper strategies to produce the desired effects. Many of those cognitions represent social outcome expectancies (normative beliefs) by pertaining to the social consequences of a particular behavior (Trafimow & Fishbein, 1995 ).

The perceived contingencies between actions and outcomes need not be explicitly worded; they can also be rather diffuse mental representations, loaded with emotions (Trafimow & Sheeran, 1998 ). Social cognition models are often misunderstood as being rational models that deal with “cold cognitions.” In line with the “bounded rationality” view, emotions would only be an error term. In contrast, health behavior change, to a large degree, is an emotional process that turns into a cognitive one after people have been asked about their thoughts and feelings, thus making them aware of what is going on emotionally. Recent studies have, therefore, focused on emotional outcome expectancies (Dunton & Vaughan, 2008 ; Lawton, Conner, & McEachan, 2009 ; Trafimow et al., 2004 ). An example of an emotional outcome expectancy is anticipated regret (“If I do not use a condom tonight, then I will regret it tomorrow”). Behavior is followed by an expected emotion (Abraham & Sheeran, 2003 ; Conner, Sandberg, McMillan, & Higgins, 2006 ). Emotional content of outcome expectancies seems to be most influential in intention formation.

Another important aspect of outcome expectancies is the focus on either gains or losses. A gain-framed message refers to a positive outcome expectancy, such as “Protect yourself from the sun and you will help yourself stay healthy,” whereas a loss-framed message can be a negative outcome expectancy, such as “Expose yourself to the sun and you will risk becoming sick” (item examples from Detweiler, Bedell, Salovey, Pronin, & Rothman, 1999 ). A similar distinction is the promotion versus prevention focus of outcome expectancies or health messages.

Outcome expectancies change over time. The distance between cognitions and actions plays a role for the decisional balance. When thinking of the consequences of lifestyle changes such as more physical activity and dietary improvements, the positive side is more valued. However, when it comes to micro-level intentions, when imminent health behaviors are at stake, the negative side comes into play. When people contemplate long-term outcomes (e.g., “I will stay slim and become healthier”), the pros might dominate the cons. When they anticipate immediate outcomes (e.g., “I will be exhausted; desserts are tempting”), the cons move into the foreground. This instability of the decisional balance changes the intention levels and reduces the subsequent likelihood of taking action. Thus, failure to act upon one’s intentions can be due to intention instability, which, in turn, emerges as a result of the reevaluation of the pros and cons, as the situation for the intended action approaches. This is in line with construal level theory (Eyal, Liberman, Trope, & Walther, 2004 ). According to this theory, mental representations of an event depend on psychological distance, which may be more or less the temporal distance to the event. More distal events are construed at a high level, whereas more proximal events are construed at a low level. Low-level construals are contextualized, concrete, and often short-term outcomes, whereas high-level construals are more decontextualized, abstract, and often long-term outcomes. Pros about an event tend to represent higher-level construals, whereas cons represent lower-level construals (Eyal et al., 2004 ). As a consequence for the design of interventions, one would make short-term and emotional outcome expectancies more salient (e.g., “You will feel more energetic after exercise; you will enjoy the taste of fresh fruits; you will regret not having used a condom”). A favorable decisional balance can be achieved even by parsimonious interventions (Göhner, Seelig, & Fuchs, 2009 ).

Perceived Self-efficacy

Perceived self-efficacy portrays individuals’ beliefs in their capabilities to exercise control over challenging demands and over their own functioning (Bandura, 1997 , 2000 ). It involves the regulation of thought processes, affective states, motivation, behavior, or changing environmental conditions. These beliefs are critical in approaching novel or difficult situations, or in adopting a strenuous self-regimen. People make an internal attribution in terms of personal competence when forecasting their behavior (e.g., “I am certain that I can quit smoking even if my friend continues to smoke”). Such optimistic self-beliefs influence the goals people set for themselves, what courses of action they choose to pursue, how much effort they invest in given endeavors, and how long they persevere in the face of barriers and setbacks. Self-efficacy influences the challenges that people take on, as well as how high they set their goals (e.g., “I intend to reduce my smoking,” or “I intend to quit smoking altogether”). Some people harbor self-doubts and cannot motivate themselves. They see little point in even setting a goal if they believe they do not have what it takes to succeed. Thus, the intention to change a habit that affects health depends to some degree on a firm belief in one’s capability to exercise control over that habit.

Perceived self-efficacy has been found to be important at all stages in the health behavior change process (Bandura, 1997 ), but it does not always constitute exactly the same construct. Its meaning depends on the particular situation of individuals who may be more or less advanced in the change process. The distinction between action self-efficacy, coping self-efficacy, and recovery self-efficacy has been brought up by Marlatt, Baer, and Quigley ( 1995 ) in the domain of addictive behaviors. The rationale for the distinction between several phase-specific self-efficacy beliefs is that, during the course of health behavior change, different tasks have to be mastered and different self-efficacy beliefs are required to master these tasks successfully. For example, a person might be confident in his or her capability to be physically active in general (i.e., high action self-efficacy), but might not be very confident to resume physical activity after a setback (low recovery self-efficacy).

Action self-efficacy (also called “preaction self-efficacy”) refers to the first phase of the process, in which an individual does not yet act, but develops a motivation to do so. It is an optimistic belief during the preactional phase. Individuals high in action self-efficacy imagine success, anticipate potential outcomes of diverse strategies, and are more likely to initiate a new behavior. Those with less self-efficacy imagine failure, harbor self-doubts, and tend to procrastinate. Although preaction self-efficacy is instrumental in the motivation phase, the two following constructs are instrumental in the subsequent volition phase and can, therefore, also by summarized under the heading of volitional self-efficacy.

Maintenance self-efficacy represents optimistic beliefs about one’s capability to cope with barriers that arise during the maintenance period. (The equivalent term “coping self-efficacy” has also been used in a different sense; therefore, we now prefer the term “maintenance self-efficacy.”) A new health behavior might turn out to be much more difficult to adhere to than expected, but a self-efficacious person responds confidently with better strategies, more effort, and prolonged persistence to overcome such hurdles. Once an action has been taken, individuals with high maintenance self-efficacy invest more effort and persist longer than those who are less self-efficacious.

Recovery self-efficacy addresses the experience of failure and recovery from setbacks. If a lapse occurs, individuals can fall prey to the “abstinence violation effect,” that is, they attribute their lapse to internal, stable, and global causes, dramatize the event, and interpret it as a full-blown relapse (Marlatt et al., 1995 ). Highly self-efficacious individuals, however, avoid this effect by attributing the lapse to an external high-risk situation and by finding ways to control the damage and to restore hope. Recovery self-efficacy pertains to one’s conviction to get back on track after being derailed. The person trusts his or her competence to regain control after a setback or failure and to reduce harm (Marlatt, 2002 ).

A functional difference exists between these self-efficacy constructs, whereas their temporal sequence is less important. Different phase-specific self-efficacy beliefs may be harbored at the same point in time. The assumption is that they operate in a different manner. For example, recovery self-efficacy is most functional when it comes to resuming an interrupted chain of action, whereas action self-efficacy is most functional when facing a novel challenging demand (Luszczynska, Mazurkiewicz, Ziegelmann, & Schwarzer, 2007 ).

This distinction between phase-specific self-efficacy beliefs has proven useful in various domains of behavior change. Action self-efficacy tends to predict intentions, whereas maintenance self-efficacy tends to predict behaviors. Individuals who had recovered from a setback needed different self-beliefs than did those who had maintained theirs levels of activity (Scholz, Sniehotta, & Schwarzer, 2005 ). Several authors (Rodgers, Hall, Blanchard, McAuley, & Munroe, 2002 ; Rodgers & Sullivan, 2001 ; Rodgers, Murray, Courneya, Bell, & Harber, 2009 ) have found evidence for phase-specific self-efficacy beliefs in the domain of exercise behavior (i.e., task self-efficacy, coping self-efficacy, and scheduling self-efficacy). Phase-specific self-efficacy differed in the effects on various preventive health behaviors, such as breast self-examination (Luszczynska & Schwarzer, 2003 ), dietary behaviors (Schwarzer & Renner, 2000 ), and physical exercise (Scholz et al., 2005 ).

Good intentions are more likely to be translated into action when people develop success scenarios and preparatory strategies of approaching a difficult task. Mental simulation helps to identify cues for action. The terms planning and implementation intentions have been used to address this phenomenon. Research on action plans for health behaviors has been suggested by Lewin ( 1947 ), for example, in the context of food choice. Lewin distinguished between an overall plan and a specific plan to take the first step toward a dietary goal. Leventhal, Singer, and Jones ( 1965 ) have argued that fear appeals can facilitate health behavior change only when combined with action plans; that is, specific instructions on when, where, and how to perform them.