How To Write a Critical Appraisal

A critical appraisal is an academic approach that refers to the systematic identification of strengths and weakness of a research article with the intent of evaluating the usefulness and validity of the work’s research findings. As with all essays, you need to be clear, concise, and logical in your presentation of arguments, analysis, and evaluation. However, in a critical appraisal there are some specific sections which need to be considered which will form the main basis of your work.

Structure of a Critical Appraisal

Introduction.

Your introduction should introduce the work to be appraised, and how you intend to proceed. In other words, you set out how you will be assessing the article and the criteria you will use. Focusing your introduction on these areas will ensure that your readers understand your purpose and are interested to read on. It needs to be clear that you are undertaking a scientific and literary dissection and examination of the indicated work to assess its validity and credibility, expressed in an interesting and motivational way.

Body of the Work

The body of the work should be separated into clear paragraphs that cover each section of the work and sub-sections for each point that is being covered. In all paragraphs your perspectives should be backed up with hard evidence from credible sources (fully cited and referenced at the end), and not be expressed as an opinion or your own personal point of view. Remember this is a critical appraisal and not a presentation of negative parts of the work.

When appraising the introduction of the article, you should ask yourself whether the article answers the main question it poses. Alongside this look at the date of publication, generally you want works to be within the past 5 years, unless they are seminal works which have strongly influenced subsequent developments in the field. Identify whether the journal in which the article was published is peer reviewed and importantly whether a hypothesis has been presented. Be objective, concise, and coherent in your presentation of this information.

Once you have appraised the introduction you can move onto the methods (or the body of the text if the work is not of a scientific or experimental nature). To effectively appraise the methods, you need to examine whether the approaches used to draw conclusions (i.e., the methodology) is appropriate for the research question, or overall topic. If not, indicate why not, in your appraisal, with evidence to back up your reasoning. Examine the sample population (if there is one), or the data gathered and evaluate whether it is appropriate, sufficient, and viable, before considering the data collection methods and survey instruments used. Are they fit for purpose? Do they meet the needs of the paper? Again, your arguments should be backed up by strong, viable sources that have credible foundations and origins.

One of the most significant areas of appraisal is the results and conclusions presented by the authors of the work. In the case of the results, you need to identify whether there are facts and figures presented to confirm findings, assess whether any statistical tests used are viable, reliable, and appropriate to the work conducted. In addition, whether they have been clearly explained and introduced during the work. In regard to the results presented by the authors you need to present evidence that they have been unbiased and objective, and if not, present evidence of how they have been biased. In this section you should also dissect the results and identify whether any statistical significance reported is accurate and whether the results presented and discussed align with any tables or figures presented.

The final element of the body text is the appraisal of the discussion and conclusion sections. In this case there is a need to identify whether the authors have drawn realistic conclusions from their available data, whether they have identified any clear limitations to their work and whether the conclusions they have drawn are the same as those you would have done had you been presented with the findings.

The conclusion of the appraisal should not introduce any new information but should be a concise summing up of the key points identified in the body text. The conclusion should be a condensation (or precis) of all that you have already written. The aim is bringing together the whole paper and state an opinion (based on evaluated evidence) of how valid and reliable the paper being appraised can be considered to be in the subject area. In all cases, you should reference and cite all sources used. To help you achieve a first class critical appraisal we have put together some key phrases that can help lift you work above that of others.

Key Phrases for a Critical Appraisal

- Whilst the title might suggest

- The focus of the work appears to be…

- The author challenges the notion that…

- The author makes the claim that…

- The article makes a strong contribution through…

- The approach provides the opportunity to…

- The authors consider…

- The argument is not entirely convincing because…

- However, whilst it can be agreed that… it should also be noted that…

- Several crucial questions are left unanswered…

- It would have been more appropriate to have stated that…

- This framework extends and increases…

- The authors correctly conclude that…

- The authors efforts can be considered as…

- Less convincing is the generalisation that…

- This appears to mislead readers indicating that…

- This research proves to be timely and particularly significant in the light of…

You may also like

- En español – ExME

- Em português – EME

Critical Appraisal: A Checklist

Posted on 6th September 2016 by Robert Will

Critical appraisal of scientific literature is a necessary skill for healthcare students. Students can be overwhelmed by the vastness of search results. Database searching is a skill in itself, but will not be covered in this blog. This blog assumes that you have found a relevant journal article to answer a clinical question. After selecting an article, you must be able to sit with the article and critically appraise it. Critical appraisal of a journal article is a literary and scientific systematic dissection in an attempt to assign merit to the conclusions of an article. Ideally, an article will be able to undergo scrutiny and retain its findings as valid.

The specific questions used to assess validity change slightly with different study designs and article types. However, in an attempt to provide a generalized checklist, no specific subtype of article has been chosen. Rather, the 20 questions below should be used as a quick reference to appraise any journal article. The first four checklist questions should be answered “Yes.” If any of the four questions are answered “no,” then you should return to your search and attempt to find an article that will meet these criteria.

Critical appraisal of…the Introduction

- Does the article attempt to answer the same question as your clinical question?

- Is the article recently published (within 5 years) or is it seminal (i.e. an earlier article but which has strongly influenced later developments)?

- Is the journal peer-reviewed?

- Do the authors present a hypothesis?

Critical appraisal of…the Methods

- Is the study design valid for your question?

- Are both inclusion and exclusion criteria described?

- Is there an attempt to limit bias in the selection of participant groups?

- Are there methodological protocols (i.e. blinding) used to limit other possible bias?

- Do the research methods limit the influence of confounding variables?

- Are the outcome measures valid for the health condition you are researching?

Critical appraisal of…the Results

- Is there a table that describes the subjects’ demographics?

- Are the baseline demographics between groups similar?

- Are the subjects generalizable to your patient?

- Are the statistical tests appropriate for the study design and clinical question?

- Are the results presented within the paper?

- Are the results statistically significant and how large is the difference between groups?

- Is there evidence of significance fishing (i.e. changing statistical tests to ensure significance)?

Critical appraisal of…the Discussion/Conclusion

- Do the authors attempt to contextualise non-significant data in an attempt to portray significance? (e.g. talking about findings which had a trend towards significance as if they were significant).

- Do the authors acknowledge limitations in the article?

- Are there any conflicts of interests noted?

This is by no means a comprehensive checklist of how to critically appraise a scientific journal article. However, by answering the previous 20 questions based on a detailed reading of an article, you can appraise most articles for their merit, and thus determine whether the results are valid. I have attempted to list the questions based on the sections most commonly present in a journal article, starting at the introduction and progressing to the conclusion. I believe some of these items are weighted heavier than others (i.e. methodological questions vs journal reputation). However, without taking this list through rigorous testing, I cannot assign a weight to them. Maybe one day, you will be able to critically appraise my future paper: How Online Checklists Influence Healthcare Students’ Ability to Critically Appraise Journal Articles.

Feature Image by Arek Socha from Pixabay

Robert Will

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

No Comments on Critical Appraisal: A Checklist

Hi Ella, I have found a checklist here for before and after study design: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools and you may also find a checklist from this blog, which has a huge number of tools listed: https://s4be.cochrane.org/blog/2018/01/12/appraising-the-appraisal/

What kind of critical appraisal tool can be used for before and after study design article? Thanks

Hello, I am currently writing a book chapter on critical appraisal skills. This chapter is limited to 1000 words so your simple 20 questions framework would be the perfect format to cite within this text. May I please have your permission to use your checklist with full acknowledgement given to you as author? Many thanks

Thank you Robert, I came across your checklist via the Royal College of Surgeons of England website; https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/library-and-publications/library/blog/dissecting-the-literature-the-importance-of-critical-appraisal/ . I really liked it and I have made reference to it for our students. I really appreciate your checklist and it is still current, thank you.

Hi Kirsten. Thank you so much for letting us know that Robert’s checklist has been used in that article – that’s so good to see. If any of your students have any comments about the blog, then do let us know. If you also note any topics that you would like to see on the website, then we can add this to the list of suggested blogs for students to write about. Thank you again. Emma.

i am really happy with it. thank you very much

A really useful guide for helping you ask questions about the studies you are reviewing BRAVO

Dr.Suryanujella,

Thank you for the comment. I’m glad you find it helpful.

Feel free to use the checklist. S4BE asks that you cite the page when you use it.

I have read your article and found it very useful , crisp with all relevant information.I would like to use it in my presentation with your permission

That’s great thank you very much. I will definitely give that a go.

I find the MEAL writing approach very versatile. You can use it to plan the entire paper and each paragraph within the paper. There are a lot of helpful MEAL resources online. But understanding the acronym can get you started.

M-Main Idea (What are you arguing?) E-Evidence (What does the literature say?) A-Analysis (Why does the literature matter to your argument?) L-Link (Transition to next paragraph or section)

I hope that is somewhat helpful. -Robert

Hi, I am a university student at Portsmouth University, UK. I understand the premise of a critical appraisal however I am unsure how to structure an essay critically appraising a paper. Do you have any pointers to help me get started?

Thank you. I’m glad that you find this helpful.

Very informative & to the point for all medical students

How can I know what is the name of this checklist or tool?

This is a checklist that the author, Robert Will, has designed himself.

Thank you for asking. I am glad you found it helpful. As Emma said, please cite the source when you use it.

Greetings Robert, I am a postgraduate student at QMUL in the UK and I have just read this comprehensive critical appraisal checklist of your. I really appreciate you. if I may ask, can I have it downloaded?

Please feel free to use the information from this blog – if you could please cite the source then that would be much appreciated.

Robert Thank you for your comptrehensive account of critical appraisal. I have just completed a teaching module on critical appraisal as part of a four module Evidence Based Medicine programme for undergraduate Meducal students at RCSI Perdana medical school in Malaysia. If you are agreeable I would like to cite it as a reference in our module.

Anthony, Please feel free to cite my checklist. Thank you for asking. I hope that your students find it helpful. They should also browse around S4BE. There are numerous other helpful articles on this site.

Subscribe to our newsletter

You will receive our monthly newsletter and free access to Trip Premium.

Related Articles

Risk Communication in Public Health

Learn why effective risk communication in public health matters and where you can get started in learning how to better communicate research evidence.

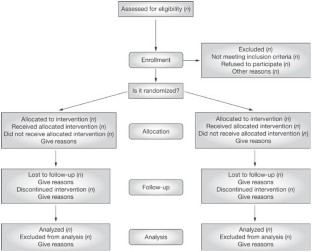

Why was the CONSORT Statement introduced?

The CONSORT statement aims at comprehensive and complete reporting of randomized controlled trials. This blog introduces you to the statement and why it is an important tool in the research world.

Measures of central tendency in clinical research papers: what we should know whilst analysing them

Learn more about the measures of central tendency (mean, mode, median) and how these need to be critically appraised when reading a paper.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Perspect Clin Res

- v.12(2); Apr-Jun 2021

Critical appraisal of published research papers – A reinforcing tool for research methodology: Questionnaire-based study

Snehalata gajbhiye.

Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Seth GS Medical College and KEM Hospital, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

Raakhi Tripathi

Urwashi parmar, nishtha khatri, anirudha potey.

1 Department of Clinical Trials, Serum Institute of India, Pune, Maharashtra, India

Background and Objectives:

Critical appraisal of published research papers is routinely conducted as a journal club (JC) activity in pharmacology departments of various medical colleges across Maharashtra, and it forms an important part of their postgraduate curriculum. The objective of this study was to evaluate the perception of pharmacology postgraduate students and teachers toward use of critical appraisal as a reinforcing tool for research methodology. Evaluation of performance of the in-house pharmacology postgraduate students in the critical appraisal activity constituted secondary objective of the study.

Materials and Methods:

The study was conducted in two parts. In Part I, a cross-sectional questionnaire-based evaluation on perception toward critical appraisal activity was carried out among pharmacology postgraduate students and teachers. In Part II of the study, JC score sheets of 2 nd - and 3 rd -year pharmacology students over the past 4 years were evaluated.

One hundred and twenty-seven postgraduate students and 32 teachers participated in Part I of the study. About 118 (92.9%) students and 28 (87.5%) faculties considered the critical appraisal activity to be beneficial for the students. JC score sheet assessments suggested that there was a statistically significant improvement in overall scores obtained by postgraduate students ( n = 25) in their last JC as compared to the first JC.

Conclusion:

Journal article criticism is a crucial tool to develop a research attitude among postgraduate students. Participation in the JC activity led to the improvement in the skill of critical appraisal of published research articles, but this improvement was not educationally relevant.

INTRODUCTION

Critical appraisal of a research paper is defined as “The process of carefully and systematically examining research to judge its trustworthiness, value and relevance in a particular context.”[ 1 ] Since scientific literature is rapidly expanding with more than 12,000 articles being added to the MEDLINE database per week,[ 2 ] critical appraisal is very important to distinguish scientifically useful and well-written articles from imprecise articles.

Educational authorities like the Medical Council of India (MCI) and Maharashtra University of Health Sciences (MUHS) have stated in pharmacology postgraduate curriculum that students must critically appraise research papers. To impart training toward these skills, MCI and MUHS have emphasized on the introduction of journal club (JC) activity for postgraduate (PG) students, wherein students review a published original research paper and state the merits and demerits of the paper. Abiding by this, pharmacology departments across various medical colleges in Maharashtra organize JC at frequent intervals[ 3 , 4 ] and students discuss varied aspects of the article with teaching faculty of the department.[ 5 ] Moreover, this activity carries a significant weightage of marks in the pharmacology university examination. As postgraduate students attend this activity throughout their 3-year tenure, it was perceived by the authors that this activity of critical appraisal of research papers could emerge as a tool for reinforcing the knowledge of research methodology. Hence, a questionnaire-based study was designed to find out the perceptions from PG students and teachers.

There have been studies that have laid emphasis on the procedure of conducting critical appraisal of research papers and its application into clinical practice.[ 6 , 7 ] However, there are no studies that have evaluated how well students are able to critically appraise a research paper. The Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics at Seth GS Medical College has developed an evaluation method to score the PG students on this skill and this tool has been implemented for the last 5 years. Since there are no research data available on the performance of PG Pharmacology students in JC, capturing the critical appraisal activity evaluation scores of in-house PG students was chosen as another objective of the study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Description of the journal club activity.

JC is conducted in the Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics at Seth GS Medical College once in every 2 weeks. During the JC activity, postgraduate students critically appraise published original research articles on their completeness and aptness in terms of the following: study title, rationale, objectives, study design, methodology-study population, inclusion/exclusion criteria, duration, intervention and safety/efficacy variables, randomization, blinding, statistical analysis, results, discussion, conclusion, references, and abstract. All postgraduate students attend this activity, while one of them critically appraises the article (who has received the research paper given by one of the faculty members 5 days before the day of JC). Other faculties also attend these sessions and facilitate the discussions. As the student comments on various sections of the paper, the same predecided faculty who gave the article (single assessor) evaluates the student on a total score of 100 which is split per section as follows: Introduction –20 marks, Methodology –20 marks, Discussion – 20 marks, Results and Conclusion –20 marks, References –10 marks, and Title, Abstract, and Keywords – 10 marks. However, there are no standard operating procedures to assess the performance of students at JC.

Methodology

After seeking permission from the Institutional Ethics Committee, the study was conducted in two parts. Part I consisted of a cross-sectional questionnaire-based survey that was conducted from October 2016 to September 2017. A questionnaire to evaluate perception towards the activity of critical appraisal of published papers as research methodology reinforcing tool was developed by the study investigators. The questionnaire consisted of 20 questions: 14 questions [refer Figure 1 ] graded on a 3-point Likert scale (agree, neutral, and disagree), 1 multiple choice selection question, 2 dichotomous questions, 1 semi-open-ended questions, and 2 open-ended questions. Content validation for this questionnaire was carried out with the help of eight pharmacology teachers. The content validity ratio per item was calculated and each item in the questionnaire had a CVR ratio (CVR) of >0.75.[ 8 ] The perception questionnaire was either E-mailed or sent through WhatsApp to PG pharmacology students and teaching faculty in pharmacology departments at various medical colleges across Maharashtra. Informed consent was obtained on E-mail from all the participants.

Graphical representation of the percentage of students/teachers who agreed that critical appraisal of research helped them improve their knowledge on various aspects of research, perceived that faculty participation is important in this activity, and considered critical appraisal activity beneficial for students. The numbers adjacent to the bar diagrams indicate the raw number of students/faculty who agreed, while brackets indicate %

Part II of the study consisted of evaluating the performance of postgraduate students toward skills of critical appraisal of published papers. For this purpose, marks obtained by 2 nd - and 3 rd -year residents during JC sessions conducted over a period of 4 years from October 2013 to September 2017 were recorded and analyzed. No data on personal identifiers of the students were captured.

Statistical analysis

Marks obtained by postgraduate students in their first and last JC were compared using Wilcoxon signed-rank test, while marks obtained by 2 nd - and 3 rd -year postgraduate students were compared using Mann–Whitney test since the data were nonparametric. These statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism statistical software, San Diego, Calfornia, USA, Version 7.0d. Data obtained from the perception questionnaire were entered in Microsoft Excel sheet and were expressed as frequencies (percentages) using descriptive statistics.

Participants who answered all items of the questionnaire were considered as complete responders and only completed questionnaires were analyzed. The questionnaire was sent through an E-mail to 100 students and through WhatsApp to 68 students. Out of the 100 students who received the questionnaire through E-mail, 79 responded completely and 8 were incomplete responders, while 13 students did not revert back. Out of the 68 students who received the questionnaire through WhatsApp, 48 responded completely, 6 gave an incomplete response, and 14 students did not revert back. Hence, of the 168 postgraduate students who received the questionnaire, 127 responded completely (student response rate for analysis = 75.6%). The questionnaire was E-mailed to 33 faculties and was sent through WhatsApp to 25 faculties. Out of the 33 faculties who received the questionnaire through E-mail, 19 responded completely, 5 responded incompletely, and 9 did not respond at all. Out of the 25 faculties who received the questionnaire through WhatsApp, 13 responded completely, 3 were incomplete responders, and 9 did not respond at all. Hence, of a total of 58 faculties who were contacted, 32 responded completely (faculty response rate for analysis = 55%). For Part I of the study, responses on the perception questionnaire from 127 postgraduate students and 32 postgraduate teachers were recorded and analyzed. None of the faculty who participated in the validation of the questionnaire participated in the survey. Number of responses obtained region wise (Mumbai region and rest of Maharashtra region) have been depicted in Table 1 .

Region-wise distribution of responses

Number of responses obtained from students/faculty belonging to Mumbai colleges and rest of Maharashtra colleges. Brackets indicate percentages

As per the data obtained on the Likert scale questions, 102 (80.3%) students and 29 (90.6%) teachers agreed that critical appraisal trains the students in doing a review of literature before selecting a particular research topic. Majority of the participants, i.e., 104 (81.9%) students and 29 (90.6%) teachers also believed that the activity increases student's knowledge regarding various experimental evaluation techniques. Moreover, 112 (88.2%) students and 27 (84.4%) faculty considered that critical appraisal activity results in improved skills of writing and understanding methodology section of research articles in terms of inclusion/exclusion criteria, endpoints, and safety/efficacy variables. About 103 (81.1%) students and 24 (75%) teachers perceived that this activity results in refinement of the student's research work. About 118 (92.9%) students and 28 (87.5%) faculty considered the critical appraisal activity to be beneficial for the students. Responses to 14 individual Likert scale items of the questionnaire have been depicted in Figure 1 .

With respect to the multiple choice selection question, 66 (52%) students and 16 (50%) teachers opined that faculty should select the paper, 53 (41.7%) students and 9 (28.1%) teachers stated that the papers should be selected by the presenting student himself/herself, while 8 (6.3%) students and 7 (21.9%) teachers expressed that some other student should select the paper to be presented at the JC.

The responses to dichotomous questions were as follows: majority of the students, that is, 109 (85.8%) and 23 (71.9%) teachers perceived that a standard checklist for article review should be given to the students before critical appraisal of journal article. Open-ended questions of the questionnaire invited suggestions from the participants regarding ways of getting trained on critical appraisal skills and of improving JC activity. Some of the suggestions given by faculty were as follows: increasing the frequency of JC activity, discussion of cited articles and new guidelines related to it, selecting all types of articles for criticism rather than only randomized controlled trials, and regular yearly exams on article criticism. Students stated that regular and frequent article criticism activity, practice of writing letter to the editor after criticism, active participation by peers and faculty, increasing weightage of marks for critical appraisal of papers in university examinations (at present marks are 50 out of 400), and a formal training for research criticism from 1 st year of postgraduation could improve critical appraisal program.

In Part II of this study, performance of the students on the skill of critical appraisal of papers was evaluated. Complete data of the first and last JC scores of a total of 25 students of the department were available, and when these scores were compared, it was seen that there was a statistically significant improvement in the overall scores ( P = 0.04), as well as in the scores obtained in methodology ( P = 0.03) and results section ( P = 0.02). This is depicted in Table 2 . Although statistically significant, the differences in scores in the methodology section, results section, and overall scores were 1.28/20, 1.28/20, and 4.36/100, respectively, amounting to 5.4%, 5.4%, and 4.36% higher scores in the last JC, which may not be considered educationally relevant (practically significant). The quantum of difference that would be considered practically significant was not decided a priori .

Comparison of marks obtained by pharmacology residents in their first and last journal club

Marks have been represented as mean±SD. The maximum marks that can be obtained in each section have been stated as maximum. *Indicates statistically significant ( P <0.05). IQR=Interquartile range, SD=Standard deviation

Scores of two groups, one group consisting of 2 nd -year postgraduate students ( n = 44) and second group consisting of 3 rd -year postgraduate students ( n = 32) were compared and revealed no statistically significant difference in overall score ( P = 0.84). This is depicted in Table 3 . Since the quantum of difference in the overall scores was meager 0.84/100 (0.84%), it cannot be considered practically significant.

Comparison of marks obtained by 2 nd - and 3 rd -year pharmacology residents in the activity of critical appraisal of research articles

Marks have been represented as mean±SD. The maximum marks that can be obtained in each section have been stated as maximum. P <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. IQR=Interquartile range, SD=Standard deviation

The present study gauged the perception of the pharmacology postgraduate students and teachers toward the use of critical appraisal activity as a reinforcing tool for research methodology. Both students and faculties (>50%) believed that critical appraisal activity increases student's knowledge on principles of ethics, experimental evaluation techniques, CONSORT guidelines, statistical analysis, concept of conflict of interest, current trends and recent advances in Pharmacology and trains on doing a review of literature, and improves skills on protocol writing and referencing. In the study conducted by Crank-Patton et al ., a survey on 278 general surgery program directors was carried out and more than 50% indicated that JC was important to their training program.[ 9 ]

The grading template used in Part II of the study was based on the IMRaD structure. Hence, equal weightage was given to the Introduction, Methodology, Results, and Discussion sections and lesser weightage was given to the references and title, abstract, and keywords sections.[ 10 ] While evaluating the scores obtained by 25 students in their first and last JC, it was seen that there was a statistically significant improvement in the overall scores of the students in their last JC. However, the meager improvement in scores cannot be considered educationally relevant, as the authors expected the students to score >90% for the upgrade to be considered educationally impactful. The above findings suggest that even though participation in the JC activity led to a steady increase in student's performance (~4%), the increment was not as expected. In addition, the students did not portray an excellent performance (>90%), with average scores being around 72% even in the last JC. This can be probably explained by the fact that students perform this activity in a routine setting and not in an examination setting. Unlike the scenario in an examination, students were aware that even if they performed at a mediocre level, there would be no repercussions.

A separate comparison of scores obtained by 44 students in their 2 nd year and 32 students in their 3 rd year of postgraduation students was also done. The number of student evaluation sheets reviewed for this analysis was greater than the number of student evaluation sheets reviewed to compare first and last JC scores. This can be spelled out by the fact that many students were still in 2 nd year when this analysis was done and the score data for their last JC, which would take place in 3 rd year, was not available. In addition, few students were asked to present at JC multiple times during the 2 nd /3 rd year of their postgraduation.

While evaluating the critical appraisal scores obtained by 2 nd - and 3 rd -year postgraduate students, it was found that although the 3 rd -year students had a mean overall score greater than the 2 nd -year students, this difference was not statistically significant. During the 1 st year of MD Pharmacology course, students at the study center attend JC once in every 2 weeks. Even though the 1 st -year students do not themselves present in JC, they listen and observe the criticism points stated by senior peers presenting at the JC, and thereby, incur substantial amount of knowledge required to critically appraise papers. By the time, they become 2 nd -year students, they are already well versed with the program and this could have led to similar overall mean scores between the 2 nd -year students (71.50 ± 10.71) and 3 rd -year students (72.34 ± 10.85). This finding suggests that attentive listening is as important as active participation in the JC. Moreover, although students are well acquainted with the process of criticism when they are in their 3 rd year, there is certainly a scope for improvement in terms of the mean overall scores.

Similar results were obtained in a study conducted by Stern et al ., in which 62 students in the internal medicine program at the New England Medical Center were asked to respond to a questionnaire, evaluate a sample article, and complete a self-assessment of competence in evaluation of research. Twenty-eight residents returned the questionnaire and the composite score for the resident's objective assessment was not significantly correlated with the postgraduate year or self-assessed critical appraisal skill.[ 11 ]

Article criticism activity provides the students with practical experience of techniques taught in research methodology workshop. However, this should be supplemented with activities that assess the improvement of designing and presenting studies, such as protocol and paper writing. Thus, critical appraisal plays a significant role in reinforcing good research practices among the new generation of physicians. Moreover, critical appraisal is an integral part of PG assessment, and although the current format of conducting JCs did not portray a clinically meaningful improvement, the authors believe that it is important to continue this activity with certain modifications suggested by students who participated in this study. Students suggested that an increase in the frequency of critical appraisal activity accompanied by the display of active participation by peers and faculty could help in the betterment of this activity. This should be brought to attention of the faculty, as students seem to be interested to learn. Critical appraisal should be a two-way teaching–learning process between the students and faculty and not a dire need for satisfying the students' eligibility criteria for postgraduate university examinations. This activity is not only for the trainee doctors but also a part of the overall faculty development program.[ 12 ]

In the present era, JCs have been used as a tool to not only teach critical appraisal skills but also to teach other necessary aspects such as research design, medical statistics, clinical epidemiology, and clinical decision-making.[ 13 , 14 ] A study conducted by Khan in 2013 suggested that success of JC program can be ensured if institutes develop a defined JC objective for the development of learning capability of students and also if they cultivate more skilled faculties.[ 15 ] A good JC is believed to facilitate relevant, meaningful scientific discussion, and evaluation of the research updates that will eventually benefit the patient care.[ 12 ]

Although there is a lot of literature emphasizing the importance of JC, there is a lack of studies that have evaluated the outcome of such activity. One such study conducted by Ibrahim et al . assessed the importance of critical appraisal as an activity in surgical trainees in Nigeria. They reported that 92.42% trainees considered the activity to be important or very important and 48% trainees stated that the activity helped in improving literature search.[ 16 ]

This study is unique since it is the first of its kind to evaluate how well students are able to critically appraise a research paper. Moreover, the study has taken into consideration the due opinions of the students as well as faculties, unlike the previous literature which has laid emphasis on only student's perception. A limitation of this study is that sample size for faculties was smaller than the students, as it was not possible to convince the distant faculty in other cities to fill the survey. Besides, there may be a variation in the manner of conduct of the critical appraisal activity in pharmacology departments across the various medical colleges in the country. Another limitation of this study was that a single assessor graded a single student during one particular JC. Nevertheless, each student presented at multiple JC and thereby came across multiple assessors. Since the articles addressed at different JC were disparate, interobserver variability was not taken into account in this study. Furthermore, the authors did not make an a priori decision on the quantum of increase in scores that would be considered educationally meaningful.

Pharmacology students and teachers acknowledge the role of critical appraisal in improving the ability to understand the crucial concepts of research methodology and research conduct. In our institute, participation in the JC activity led to an improvement in the skill of critical appraisal of published research articles among the pharmacology postgraduate students. However, this improvement was not educationally relevant. The scores obtained by final-year postgraduate students in this activity were nearly 72% indicating that there is still scope of betterment in this skill.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the support rendered by the entire Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics at Seth GS Medical College.

Writing a Critical Analysis

What is in this guide, definitions, putting it together, tips and examples of critques.

- Background Information

- Cite Sources

Library Links

- Ask a Librarian

- Library Tutorials

- The Research Process

- Library Hours

- Online Databases (A-Z)

- Interlibrary Loan (ILL)

- Reserve a Study Room

- Report a Problem

This guide is meant to help you understand the basics of writing a critical analysis. A critical analysis is an argument about a particular piece of media. There are typically two parts: (1) identify and explain the argument the author is making, and (2), provide your own argument about that argument. Your instructor may have very specific requirements on how you are to write your critical analysis, so make sure you read your assignment carefully.

Critical Analysis

A deep approach to your understanding of a piece of media by relating new knowledge to what you already know.

Part 1: Introduction

- Identify the work being criticized.

- Present thesis - argument about the work.

- Preview your argument - what are the steps you will take to prove your argument.

Part 2: Summarize

- Provide a short summary of the work.

- Present only what is needed to know to understand your argument.

Part 3: Your Argument

- This is the bulk of your paper.

- Provide "sub-arguments" to prove your main argument.

- Use scholarly articles to back up your argument(s).

Part 4: Conclusion

- Reflect on how you have proven your argument.

- Point out the importance of your argument.

- Comment on the potential for further research or analysis.

- Cornell University Library Tips for writing a critical appraisal and analysis of a scholarly article.

- Queen's University Library How to Critique an Article (Psychology)

- University of Illinois, Springfield An example of a summary and an evaluation of a research article. This extended example shows the different ways a student can critique and write about an article

- Next: Background Information >>

- Last Updated: Feb 14, 2024 4:33 PM

- URL: https://libguides.pittcc.edu/critical_analysis

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 20 January 2009

How to critically appraise an article

- Jane M Young 1 &

- Michael J Solomon 2

Nature Clinical Practice Gastroenterology & Hepatology volume 6 , pages 82–91 ( 2009 ) Cite this article

52k Accesses

100 Citations

431 Altmetric

Metrics details

Critical appraisal is a systematic process used to identify the strengths and weaknesses of a research article in order to assess the usefulness and validity of research findings. The most important components of a critical appraisal are an evaluation of the appropriateness of the study design for the research question and a careful assessment of the key methodological features of this design. Other factors that also should be considered include the suitability of the statistical methods used and their subsequent interpretation, potential conflicts of interest and the relevance of the research to one's own practice. This Review presents a 10-step guide to critical appraisal that aims to assist clinicians to identify the most relevant high-quality studies available to guide their clinical practice.

Critical appraisal is a systematic process used to identify the strengths and weaknesses of a research article

Critical appraisal provides a basis for decisions on whether to use the results of a study in clinical practice

Different study designs are prone to various sources of systematic bias

Design-specific, critical-appraisal checklists are useful tools to help assess study quality

Assessments of other factors, including the importance of the research question, the appropriateness of statistical analysis, the legitimacy of conclusions and potential conflicts of interest are an important part of the critical appraisal process

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

195,33 € per year

only 16,28 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Making sense of the literature: an introduction to critical appraisal for the primary care practitioner

How to appraise the literature: basic principles for the busy clinician - part 2: systematic reviews and meta-analyses

How to appraise the literature: basic principles for the busy clinician - part 1: randomised controlled trials

Druss BG and Marcus SC (2005) Growth and decentralisation of the medical literature: implications for evidence-based medicine. J Med Libr Assoc 93 : 499–501

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Glasziou PP (2008) Information overload: what's behind it, what's beyond it? Med J Aust 189 : 84–85

PubMed Google Scholar

Last JE (Ed.; 2001) A Dictionary of Epidemiology (4th Edn). New York: Oxford University Press

Google Scholar

Sackett DL et al . (2000). Evidence-based Medicine. How to Practice and Teach EBM . London: Churchill Livingstone

Guyatt G and Rennie D (Eds; 2002). Users' Guides to the Medical Literature: a Manual for Evidence-based Clinical Practice . Chicago: American Medical Association

Greenhalgh T (2000) How to Read a Paper: the Basics of Evidence-based Medicine . London: Blackwell Medicine Books

MacAuley D (1994) READER: an acronym to aid critical reading by general practitioners. Br J Gen Pract 44 : 83–85

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hill A and Spittlehouse C (2001) What is critical appraisal. Evidence-based Medicine 3 : 1–8 [ http://www.evidence-based-medicine.co.uk ] (accessed 25 November 2008)

Public Health Resource Unit (2008) Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) . [ http://www.phru.nhs.uk/Pages/PHD/CASP.htm ] (accessed 8 August 2008)

National Health and Medical Research Council (2000) How to Review the Evidence: Systematic Identification and Review of the Scientific Literature . Canberra: NHMRC

Elwood JM (1998) Critical Appraisal of Epidemiological Studies and Clinical Trials (2nd Edn). Oxford: Oxford University Press

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2002) Systems to rate the strength of scientific evidence? Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No 47, Publication No 02-E019 Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

Crombie IK (1996) The Pocket Guide to Critical Appraisal: a Handbook for Health Care Professionals . London: Blackwell Medicine Publishing Group

Heller RF et al . (2008) Critical appraisal for public health: a new checklist. Public Health 122 : 92–98

Article Google Scholar

MacAuley D et al . (1998) Randomised controlled trial of the READER method of critical appraisal in general practice. BMJ 316 : 1134–37

Article CAS Google Scholar

Parkes J et al . Teaching critical appraisal skills in health care settings (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 3. Art. No.: cd001270. 10.1002/14651858.cd001270

Mays N and Pope C (2000) Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ 320 : 50–52

Hawking SW (2003) On the Shoulders of Giants: the Great Works of Physics and Astronomy . Philadelphia, PN: Penguin

National Health and Medical Research Council (1999) A Guide to the Development, Implementation and Evaluation of Clinical Practice Guidelines . Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council

US Preventive Services Taskforce (1996) Guide to clinical preventive services (2nd Edn). Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins

Solomon MJ and McLeod RS (1995) Should we be performing more randomized controlled trials evaluating surgical operations? Surgery 118 : 456–467

Rothman KJ (2002) Epidemiology: an Introduction . Oxford: Oxford University Press

Young JM and Solomon MJ (2003) Improving the evidence-base in surgery: sources of bias in surgical studies. ANZ J Surg 73 : 504–506

Margitic SE et al . (1995) Lessons learned from a prospective meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 43 : 435–439

Shea B et al . (2001) Assessing the quality of reports of systematic reviews: the QUORUM statement compared to other tools. In Systematic Reviews in Health Care: Meta-analysis in Context 2nd Edition, 122–139 (Eds Egger M. et al .) London: BMJ Books

Chapter Google Scholar

Easterbrook PH et al . (1991) Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet 337 : 867–872

Begg CB and Berlin JA (1989) Publication bias and dissemination of clinical research. J Natl Cancer Inst 81 : 107–115

Moher D et al . (2000) Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUORUM statement. Br J Surg 87 : 1448–1454

Shea BJ et al . (2007) Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology 7 : 10 [10.1186/1471-2288-7-10]

Stroup DF et al . (2000) Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 283 : 2008–2012

Young JM and Solomon MJ (2003) Improving the evidence-base in surgery: evaluating surgical effectiveness. ANZ J Surg 73 : 507–510

Schulz KF (1995) Subverting randomization in controlled trials. JAMA 274 : 1456–1458

Schulz KF et al . (1995) Empirical evidence of bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA 273 : 408–412

Moher D et al . (2001) The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel group randomized trials. BMC Medical Research Methodology 1 : 2 [ http://www.biomedcentral.com/ 1471-2288/1/2 ] (accessed 25 November 2008)

Rochon PA et al . (2005) Reader's guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 1. Role and design. BMJ 330 : 895–897

Mamdani M et al . (2005) Reader's guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 2. Assessing potential for confounding. BMJ 330 : 960–962

Normand S et al . (2005) Reader's guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 3. Analytical strategies to reduce confounding. BMJ 330 : 1021–1023

von Elm E et al . (2007) Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 335 : 806–808

Sutton-Tyrrell K (1991) Assessing bias in case-control studies: proper selection of cases and controls. Stroke 22 : 938–942

Knottnerus J (2003) Assessment of the accuracy of diagnostic tests: the cross-sectional study. J Clin Epidemiol 56 : 1118–1128

Furukawa TA and Guyatt GH (2006) Sources of bias in diagnostic accuracy studies and the diagnostic process. CMAJ 174 : 481–482

Bossyut PM et al . (2003)The STARD statement for reporting studies of diagnostic accuracy: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 138 : W1–W12

STARD statement (Standards for the Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies). [ http://www.stard-statement.org/ ] (accessed 10 September 2008)

Raftery J (1998) Economic evaluation: an introduction. BMJ 316 : 1013–1014

Palmer S et al . (1999) Economics notes: types of economic evaluation. BMJ 318 : 1349

Russ S et al . (1999) Barriers to participation in randomized controlled trials: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol 52 : 1143–1156

Tinmouth JM et al . (2004) Are claims of equivalency in digestive diseases trials supported by the evidence? Gastroentrology 126 : 1700–1710

Kaul S and Diamond GA (2006) Good enough: a primer on the analysis and interpretation of noninferiority trials. Ann Intern Med 145 : 62–69

Piaggio G et al . (2006) Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. JAMA 295 : 1152–1160

Heritier SR et al . (2007) Inclusion of patients in clinical trial analysis: the intention to treat principle. In Interpreting and Reporting Clinical Trials: a Guide to the CONSORT Statement and the Principles of Randomized Controlled Trials , 92–98 (Eds Keech A. et al .) Strawberry Hills, NSW: Australian Medical Publishing Company

National Health and Medical Research Council (2007) National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 89–90 Canberra: NHMRC

Lo B et al . (2000) Conflict-of-interest policies for investigators in clinical trials. N Engl J Med 343 : 1616–1620

Kim SYH et al . (2004) Potential research participants' views regarding researcher and institutional financial conflicts of interests. J Med Ethics 30 : 73–79

Komesaroff PA and Kerridge IH (2002) Ethical issues concerning the relationships between medical practitioners and the pharmaceutical industry. Med J Aust 176 : 118–121

Little M (1999) Research, ethics and conflicts of interest. J Med Ethics 25 : 259–262

Lemmens T and Singer PA (1998) Bioethics for clinicians: 17. Conflict of interest in research, education and patient care. CMAJ 159 : 960–965

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

JM Young is an Associate Professor of Public Health and the Executive Director of the Surgical Outcomes Research Centre at the University of Sydney and Sydney South-West Area Health Service, Sydney,

Jane M Young

MJ Solomon is Head of the Surgical Outcomes Research Centre and Director of Colorectal Research at the University of Sydney and Sydney South-West Area Health Service, Sydney, Australia.,

Michael J Solomon

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jane M Young .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Young, J., Solomon, M. How to critically appraise an article. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 6 , 82–91 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncpgasthep1331

Download citation

Received : 10 August 2008

Accepted : 03 November 2008

Published : 20 January 2009

Issue Date : February 2009

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/ncpgasthep1331

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Emergency physicians’ perceptions of critical appraisal skills: a qualitative study.

- Sumintra Wood

- Jacqueline Paulis

- Angela Chen

BMC Medical Education (2022)

An integrative review on individual determinants of enrolment in National Health Insurance Scheme among older adults in Ghana

- Anthony Kwame Morgan

- Anthony Acquah Mensah

BMC Primary Care (2022)

Autopsy findings of COVID-19 in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Anju Khairwa

- Kana Ram Jat

Forensic Science, Medicine and Pathology (2022)

The use of a modified Delphi technique to develop a critical appraisal tool for clinical pharmacokinetic studies

- Alaa Bahaa Eldeen Soliman

- Shane Ashley Pawluk

- Ousama Rachid

International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy (2022)

Critical Appraisal: Analysis of a Prospective Comparative Study Published in IJS

- Ramakrishna Ramakrishna HK

- Swarnalatha MC

Indian Journal of Surgery (2021)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

How to critically appraise an article

Affiliation.

- 1 Surgical Outcomes Research Centre, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Missenden Road, Sydney, NSW 2050, Australia. [email protected]

- PMID: 19153565

- DOI: 10.1038/ncpgasthep1331

Critical appraisal is a systematic process used to identify the strengths and weaknesses of a research article in order to assess the usefulness and validity of research findings. The most important components of a critical appraisal are an evaluation of the appropriateness of the study design for the research question and a careful assessment of the key methodological features of this design. Other factors that also should be considered include the suitability of the statistical methods used and their subsequent interpretation, potential conflicts of interest and the relevance of the research to one's own practice. This Review presents a 10-step guide to critical appraisal that aims to assist clinicians to identify the most relevant high-quality studies available to guide their clinical practice.

Publication types

- Decision Making*

- Evidence-Based Medicine*

Medicine: A Brief Guide to Critical Appraisal

- Quick Start

- First Year Library Essentials

- Literature Reviews and Data Management

- Systematic Search for Health This link opens in a new window

- Guide to Using EndNote This link opens in a new window

- A Brief Guide to Critical Appraisal

- Manage Research Data This link opens in a new window

- Articles & Databases

- Anatomy & Radiology

- Medicines Information

- Diagnostic Tests & Calculators

- Health Statistics

- Multimedia Sources

- News & Public Opinion

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Guide This link opens in a new window

- Medical Ethics Guide This link opens in a new window

Have you ever seen a news piece about a scientific breakthrough and wondered how accurate the reporting is? Or wondered about the research behind the headlines? This is the beginning of critical appraisal: thinking critically about what you see and hear, and asking questions to determine how much of a 'breakthrough' something really is.

The article " Is this study legit? 5 questions to ask when reading news stories of medical research " is a succinct introduction to the sorts of questions you should ask in these situations, but there's more than that when it comes to critical appraisal. Read on to learn more about this practical and crucial aspect of evidence-based practice.

What is Critical Appraisal?

Critical appraisal forms part of the process of evidence-based practice. “ Evidence-based practice across the health professions ” outlines the fives steps of this process. Critical appraisal is step three:

- Ask a question

- Access the information

- Appraise the articles found

- Apply the information

Critical appraisal is the examination of evidence to determine applicability to clinical practice. It considers (1) :

- Are the results of the study believable?

- Was the study methodologically sound?

- What is the clinical importance of the study’s results?

- Are the findings sufficiently important? That is, are they practice-changing?

- Are the results of the study applicable to your patient?

- Is your patient comparable to the population in the study?

Why Critically Appraise?

If practitioners hope to ‘stand on the shoulders of giants’, practicing in a manner that is responsive to the discoveries of the research community, then it makes sense for the responsible, critically thinking practitioner to consider the reliability, influence, and relevance of the evidence presented to them.

While critical thinking is valuable, it is also important to avoid treading too much into cynicism; in the words of Hoffman et al. (1):

… keep in mind that no research is perfect and that it is important not to be overly critical of research articles. An article just needs to be good enough to assist you to make a clinical decision.

How do I Critically Appraise?

Evidence-based practice is intended to be practical . To enable this, critical appraisal checklists have been developed to guide practitioners through the process in an efficient yet comprehensive manner.

Critical appraisal checklists guide the reader through the appraisal process by prompting the reader to ask certain questions of the paper they are appraising. There are many different critical appraisal checklists but the best apply certain questions based on what type of study the paper is describing. This allows for a more nuanced and appropriate appraisal. Wherever possible, choose the appraisal tool that best fits the study you are appraising.

Like many things in life, repetition builds confidence and the more you apply critical appraisal tools (like checklists) to the literature the more the process will become second nature for you and the more effective you will be.

How do I Identify Study Types?

Identifying the study type described in the paper is sometimes a harder job than it should be. Helpful papers spell out the study type in the title or abstract, but not all papers are helpful in this way. As such, the critical appraiser may need to do a little work to identify what type of study they are about to critique. Again, experience builds confidence but having an understanding of the typical features of common study types certainly helps.

To assist with this, the Library has produced a guide to study designs in health research .

The following selected references will help also with understanding study types but there are also other resources in the Library’s collection and freely available online:

- The “ How to read a paper ” article series from The BMJ is a well-known source for establishing an understanding of the features of different study types; this series was subsequently adapted into a book (“ How to read a paper: the basics of evidence-based medicine ”) which offers more depth and currency than that found in the articles. (2)

- Chapter two of “ Evidence-based practice across the health professions ” briefly outlines some study types and their application; subsequent chapters go into more detail about different study types depending on what type of question they are exploring (intervention, diagnosis, prognosis, qualitative) along with systematic reviews.

- “ Clinical evidence made easy ” contains several chapters on different study designs and also includes critical appraisal tools. (3)

- “ Translational research and clinical practice: basic tools for medical decision making and self-learning ” unpacks the components of a paper, explaining their purpose along with key features of different study designs. (4)

- The BMJ website contains the contents of the fourth edition of the book “ Epidemiology for the uninitiated ”. This eBook contains chapters exploring ecological studies, longitudinal studies, case-control and cross-sectional studies, and experimental studies.

Reporting Guidelines

In order to encourage consistency and quality, authors of reports on research should follow reporting guidelines when writing their papers. The EQUATOR Network is a good source of reporting guidelines for the main study types.

While these guidelines aren't critical appraisal tools as such, they can assist by prompting you to consider whether the reporting of the research is missing important elements.

Once you've identified the study type at hand, visit EQUATOR to find the associated reporting guidelines and ask yourself: does this paper meet the guideline for its study type?

Which Checklist Should I Use?

Determining which checklist to use ultimately comes down to finding an appraisal tool that:

- Fits best with the study you are appraising

- Is reliable, well-known or otherwise validated

- You understand and are comfortable using

Below are some sources of critical appraisal tools. These have been selected as they are known to be widely accepted, easily applicable, and relevant to appraisal of a typical journal article. You may find another tool that you prefer, which is acceptable as long as it is defensible:

- CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme)

- JBI (Joanna Briggs Institute)

- CEBM (Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine)

- SIGN (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network)

- STROBE (Strengthing the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology)

- BMJ Best Practice

The information on this page has been compiled by the Medical Librarian. Please contact the Library's Health Team ( [email protected] ) for further assistance.

Reference list

1. Hoffmann T, Bennett S, Del Mar C. Evidence-based practice across the health professions. 2nd ed. Chatswood, N.S.W., Australia: Elsevier Churchill Livingston; 2013.

2. Greenhalgh T. How to read a paper : the basics of evidence-based medicine. 5th ed. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley; 2014.

3. Harris M, Jackson D, Taylor G. Clinical evidence made easy. Oxfordshire, England: Scion Publishing; 2014.

4. Aronoff SC. Translational research and clinical practice: basic tools for medical decision making and self-learning. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011.

- << Previous: Guide to Using EndNote

- Next: Manage Research Data >>

- Last Updated: Mar 27, 2024 9:22 AM

- URL: https://deakin.libguides.com/medicine

Please enter both an email address and a password.

Account login

- Show/Hide Password Show password Hide password

- Reset Password

Need to reset your password? Enter the email address which you used to register on this site (or your membership/contact number) and we'll email you a link to reset it. You must complete the process within 2hrs of receiving the link.

We've sent you an email.

An email has been sent to Simply follow the link provided in the email to reset your password. If you can't find the email please check your junk or spam folder and add [email protected] to your address book.

- About RCS England

MRCS Part A

- Dissecting the literature: the importance of critical appraisal

08 Dec 2017

Kirsty Morrison

This post was updated in 2023.

Critical appraisal is the process of carefully and systematically examining research to judge its trustworthiness, and its value and relevance in a particular context.

Amanda Burls, What is Critical Appraisal?

Why is critical appraisal needed?

Literature searches using databases like Medline or EMBASE often result in an overwhelming volume of results which can vary in quality. Similarly, those who browse medical literature for the purposes of CPD or in response to a clinical query will know that there are vast amounts of content available. Critical appraisal helps to reduce the burden and allow you to focus on articles that are relevant to the research question, and that can reliably support or refute its claims with high-quality evidence, or identify high-level research relevant to your practice.

Critical appraisal allows us to:

- reduce information overload by eliminating irrelevant or weak studies

- identify the most relevant papers

- distinguish evidence from opinion, assumptions, misreporting, and belief

- assess the validity of the study

- assess the usefulness and clinical applicability of the study

- recognise any potential for bias.

Critical appraisal helps to separate what is significant from what is not. One way we use critical appraisal in the Library is to prioritise the most clinically relevant content for our Current Awareness Updates .

How to critically appraise a paper

There are some general rules to help you, including a range of checklists highlighted at the end of this blog. Some key questions to consider when critically appraising a paper:

- Is the study question relevant to my field?

- Does the study add anything new to the evidence in my field?

- What type of research question is being asked? A well-developed research question usually identifies three components: the group or population of patients, the studied parameter (e.g. a therapy or clinical intervention) and outcomes of interest.

- Was the study design appropriate for the research question? You can learn more about different study types and the hierarchy of evidence here .

- Did the methodology address important potential sources of bias? Bias can be attributed to chance (e.g. random error) or to the study methods (systematic bias).

- Was the study performed according to the original protocol? Deviations from the planned protocol can affect the validity or relevance of a study, e.g. a decrease in the studied population over the course of a randomised controlled trial .

- Does the study test a stated hypothesis? Is there a clear statement of what the investigators expect the study to find which can be tested, and confirmed or refuted.

- Were the statistical analyses performed correctly? The approach to dealing with missing data, and the statistical techniques that have been applied should be specified. Original data should be presented clearly so that readers can check the statistical accuracy of the paper.

- Do the data justify the conclusions? Watch out for definite conclusions based on statistically insignificant results, generalised findings from a small sample size, and statistically significant associations being misinterpreted to imply a cause and effect.

- Are there any conflicts of interest? Who has funded the study and can we trust their objectivity? Do the authors have any potential conflicts of interest, and have these been declared?

And an important consideration for surgeons:

- Will the results help me manage my patients?

At the end of the appraisal process you should have a better appreciation of how strong the evidence is, and ultimately whether or not you should apply it to your patients.

Further resources:

- How to Read a Paper by Trisha Greenhalgh

- The Doctor’s Guide to Critical Appraisal by Narinder Kaur Gosall

- CASP checklists

- CEBM Critical Appraisal Tools

- Critical Appraisal: a checklist

- Critical Appraisal of a Journal Article (PDF)

- Introduction to...Critical appraisal of literature

- Reporting guidelines for the main study types

Kirsty Morrison, Information Specialist

Share this page:

- Library Blog

Critically Analyzing Information Sources: Critical Appraisal and Analysis

- Critical Appraisal and Analysis

Initial Appraisal : Reviewing the source

- What are the author's credentials--institutional affiliation (where he or she works), educational background, past writings, or experience? Is the book or article written on a topic in the author's area of expertise? You can use the various Who's Who publications for the U.S. and other countries and for specific subjects and the biographical information located in the publication itself to help determine the author's affiliation and credentials.

- Has your instructor mentioned this author? Have you seen the author's name cited in other sources or bibliographies? Respected authors are cited frequently by other scholars. For this reason, always note those names that appear in many different sources.

- Is the author associated with a reputable institution or organization? What are the basic values or goals of the organization or institution?

B. Date of Publication

- When was the source published? This date is often located on the face of the title page below the name of the publisher. If it is not there, look for the copyright date on the reverse of the title page. On Web pages, the date of the last revision is usually at the bottom of the home page, sometimes every page.

- Is the source current or out-of-date for your topic? Topic areas of continuing and rapid development, such as the sciences, demand more current information. On the other hand, topics in the humanities often require material that was written many years ago. At the other extreme, some news sources on the Web now note the hour and minute that articles are posted on their site.

C. Edition or Revision

Is this a first edition of this publication or not? Further editions indicate a source has been revised and updated to reflect changes in knowledge, include omissions, and harmonize with its intended reader's needs. Also, many printings or editions may indicate that the work has become a standard source in the area and is reliable. If you are using a Web source, do the pages indicate revision dates?

D. Publisher

Note the publisher. If the source is published by a university press, it is likely to be scholarly. Although the fact that the publisher is reputable does not necessarily guarantee quality, it does show that the publisher may have high regard for the source being published.

E. Title of Journal

Is this a scholarly or a popular journal? This distinction is important because it indicates different levels of complexity in conveying ideas. If you need help in determining the type of journal, see Distinguishing Scholarly from Non-Scholarly Periodicals . Or you may wish to check your journal title in the latest edition of Katz's Magazines for Libraries (Olin Reference Z 6941 .K21, shelved at the reference desk) for a brief evaluative description.

Critical Analysis of the Content

Having made an initial appraisal, you should now examine the body of the source. Read the preface to determine the author's intentions for the book. Scan the table of contents and the index to get a broad overview of the material it covers. Note whether bibliographies are included. Read the chapters that specifically address your topic. Reading the article abstract and scanning the table of contents of a journal or magazine issue is also useful. As with books, the presence and quality of a bibliography at the end of the article may reflect the care with which the authors have prepared their work.

A. Intended Audience

What type of audience is the author addressing? Is the publication aimed at a specialized or a general audience? Is this source too elementary, too technical, too advanced, or just right for your needs?

B. Objective Reasoning

- Is the information covered fact, opinion, or propaganda? It is not always easy to separate fact from opinion. Facts can usually be verified; opinions, though they may be based on factual information, evolve from the interpretation of facts. Skilled writers can make you think their interpretations are facts.

- Does the information appear to be valid and well-researched, or is it questionable and unsupported by evidence? Assumptions should be reasonable. Note errors or omissions.

- Are the ideas and arguments advanced more or less in line with other works you have read on the same topic? The more radically an author departs from the views of others in the same field, the more carefully and critically you should scrutinize his or her ideas.

- Is the author's point of view objective and impartial? Is the language free of emotion-arousing words and bias?

C. Coverage

- Does the work update other sources, substantiate other materials you have read, or add new information? Does it extensively or marginally cover your topic? You should explore enough sources to obtain a variety of viewpoints.

- Is the material primary or secondary in nature? Primary sources are the raw material of the research process. Secondary sources are based on primary sources. For example, if you were researching Konrad Adenauer's role in rebuilding West Germany after World War II, Adenauer's own writings would be one of many primary sources available on this topic. Others might include relevant government documents and contemporary German newspaper articles. Scholars use this primary material to help generate historical interpretations--a secondary source. Books, encyclopedia articles, and scholarly journal articles about Adenauer's role are considered secondary sources. In the sciences, journal articles and conference proceedings written by experimenters reporting the results of their research are primary documents. Choose both primary and secondary sources when you have the opportunity.

D. Writing Style

Is the publication organized logically? Are the main points clearly presented? Do you find the text easy to read, or is it stilted or choppy? Is the author's argument repetitive?

E. Evaluative Reviews

- Locate critical reviews of books in a reviewing source , such as the Articles & Full Text , Book Review Index , Book Review Digest, and ProQuest Research Library . Is the review positive? Is the book under review considered a valuable contribution to the field? Does the reviewer mention other books that might be better? If so, locate these sources for more information on your topic.

- Do the various reviewers agree on the value or attributes of the book or has it aroused controversy among the critics?

- For Web sites, consider consulting this evaluation source from UC Berkeley .

Permissions Information

If you wish to use or adapt any or all of the content of this Guide go to Cornell Library's Research Guides Use Conditions to review our use permissions and our Creative Commons license.

- Next: Tips >>

- Last Updated: Apr 18, 2022 1:43 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.cornell.edu/critically_analyzing

Writing Academically

Proofreading, other editing & coaching for highly successful academic writing

- Editing & coaching pricing

- Academic coaching

- How to conduct a targeted literature search

How to write a successful critical analysis

- How to write a strong literature review

- Cautious in tone

- Formal English

- Precise and concise English

- Impartial and objective English

- Substantiate your claims

- The academic team

For further queries or assistance in writing a critical analysis email Bill Wrigley .

What do you critically analyse?

In a critical analysis you do not express your own opinion or views on the topic. You need to develop your thesis, position or stance on the topic from the views and research of others . In academic writing you critically analyse other researchers’:

- concepts, terms

- viewpoints, arguments, positions

- methodologies, approaches

- research results and conclusions

This means weighing up the strength of the arguments or research support on the topic, and deciding who or what has the more or stronger weight of evidence or support.

Therefore, your thesis argues, with evidence, why a particular theory, concept, viewpoint, methodology, or research result(s) is/are stronger, more sound, or more advantageous than others.

What does ‘analysis’ mean?

A critical analysis means analysing or breaking down the parts of the literature and grouping these into themes, patterns or trends.

In an analysis you need to: