- May 20, 2024 | When Cells Turn Against Us: The Ferroptosis Link in COVID-19 Lung Destruction

- May 20, 2024 | Ancient Egypt’s Engineering Marvel: Archaeologists Uncover Hidden River Beneath the Desert

- May 20, 2024 | From Ancient Egyptian Myths to Astrophysics: A Jewel in the Queen’s Hair

- May 19, 2024 | Trustnet Unveils a New Era in Decentralizing Online Fact-Checking

- May 19, 2024 | Quantum Coherence: Harvard Scientists Uncover Hidden Order in Chemical Chaos

Redefining Dementia Treatment: Berkeley Scientists Unveil Promising New Breakthrough

By University of California - Berkeley February 28, 2024

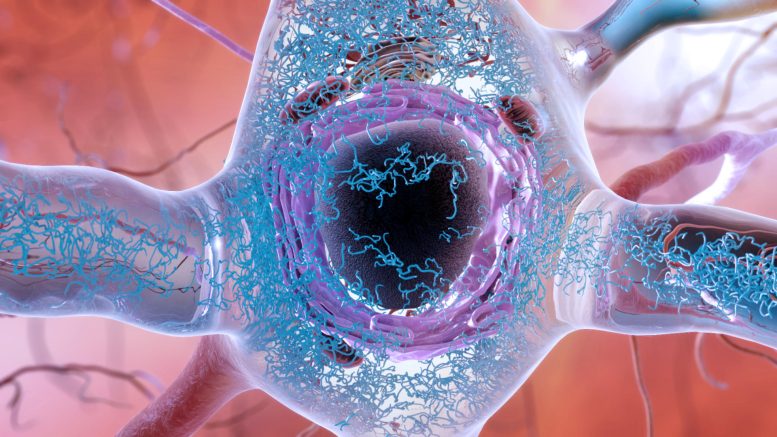

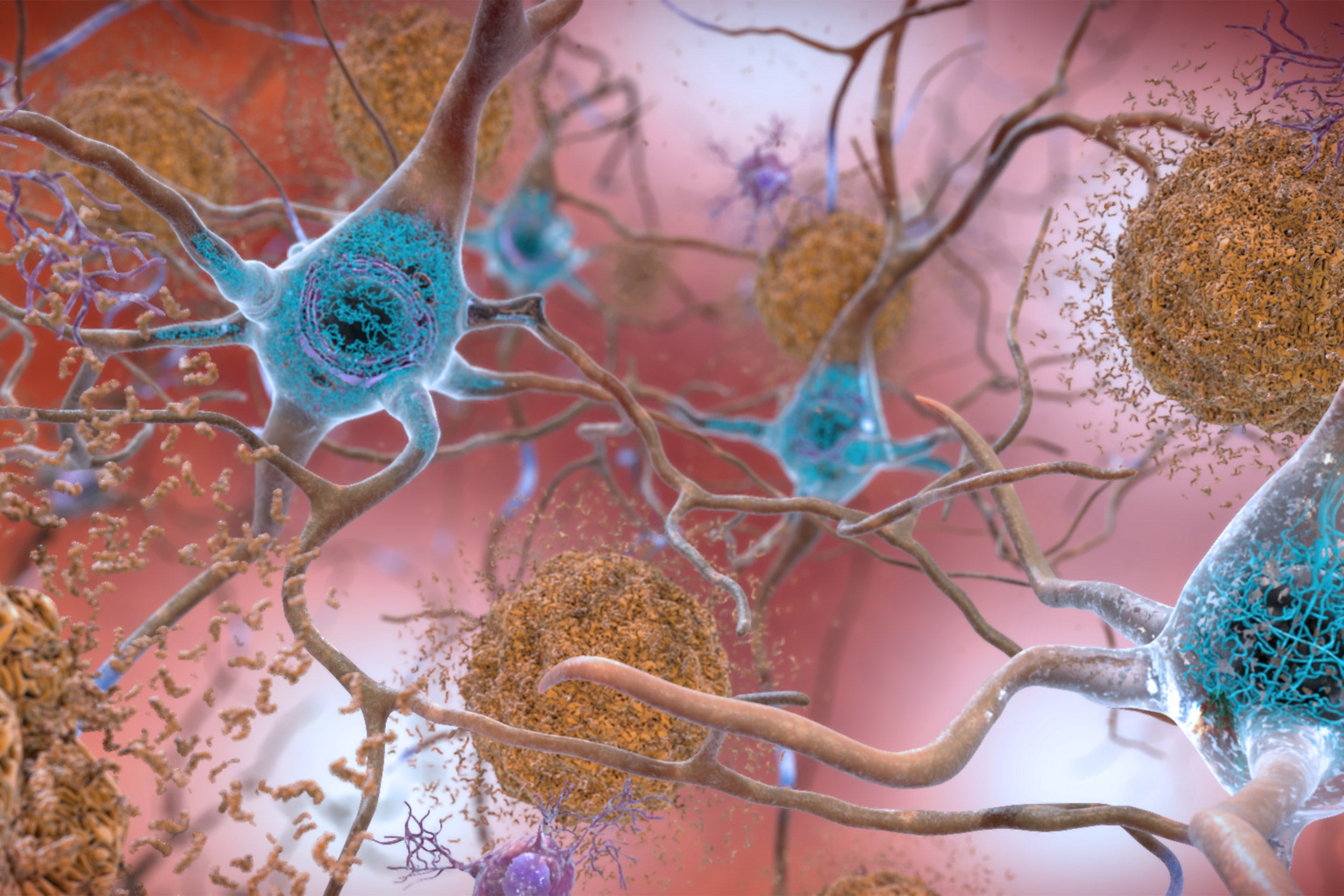

An illustration of a brain cell in a person with Alzheimer’s disease, showing the accumulation and clumping of tau proteins (blue squiggles) in the cytoplasm of a brain cell. Protein clumps, also known as aggregates, are thought to lead to cell death and dementia. New research suggests that such clumps may not cause brain cell death directly, but rather throw the cell’s response to stress off balance so that it never gets switched off. Credit: National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health

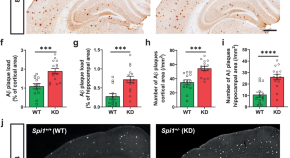

Research from UC Berkeley indicates that ongoing stress caused by protein aggregation is leading to the death of brain cells.

Numerous neurodegenerative conditions, including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, involve the buildup of protein clusters, known as aggregates, within the brain. This phenomenon has prompted researchers to hypothesize that these protein masses are responsible for the death of brain cells. Despite this, efforts to develop treatments that break up and remove these tangled proteins have had little success.

But a new discovery by University of California, Berkeley , researchers suggests that the accumulation of aggregated proteins isn’t what kills brain cells. Rather, it’s the body’s failure to turn off these cells’ stress response.

In a study recently published in the journal Nature , the researchers reported that delivering a drug that forces the stress response to shut down saves cells that mimic a type of neurodegenerative disease known as early-onset dementia.

The Role of the SIFI Complex in Neurodegeneration

According to lead researcher Michael Rapé, the finding could offer clinicians another option for treatment for some neurodegenerative diseases, at least for those caused by mutations in the protein that switches off the cellular stress response. These include inherited diseases that lead to ataxia, or loss of muscle control, and early-onset dementia.

In addition, Rapé noted that other neurodegenerative diseases, including Mohr–Tranebjærg syndrome, childhood ataxia, and Leigh syndrome, are also characterized by stress responses in overdrive and have symptoms similar to those of the early onset dementia mimicked in the new study.

“We always thought that protein clumps directly kill neurons, for example by puncturing membrane structures within these cells. Yet, we now found that aggregates prevent the silencing of a stress response that cells originally mount to cope with bad proteins. The stress response is always on, and that’s what kills the cells,” said Rapé, head of the new division of molecular therapeutics in UC Berkeley’s Department of Molecular and Cell Biology and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator. “We think that the same mechanisms may underlie more common pathologies that also show widespread aggregation, such as Alzheimer’s disease or frontotemporal dementia, but more work is needed to investigate the role of stress signaling in these diseases.”

Key to the discoveries by Rapé’s lab was the researchers’ finding that stress responses need to be turned off once a brain cell has successfully addressed a difficult situation. Rapé explained this finding to his son in simple terms: You not only need to clean up your room, but also turn out the light before going to bed. If you don’t turn off the light, you can’t fall asleep, but if you turn it off before you cleaned up your room, you would stumble if you had to get up in the dark.

Similarly, a cell has to clean up protein aggregates before turning off the stress response. If it doesn’t turn off the stress response, the cell will ultimately die.

“Aggregates don’t kill cells directly. They kill cells because they keep the light on,” he said. “But that means that you can treat these diseases, or at least the dozen or so neurodegenerative diseases that we found have kept their stress responses on. You treat them with an inhibitor that turns off the light. You don’t have to worry about completely getting rid of large aggregates, which changes how we think about treating neurodegenerative diseases. And most importantly, it makes this really doable.”

In their paper, Rapé and his colleagues describe a very large protein complex they discovered called SIFI (SIlencing Factor of the Integrated stress response). This machine serves two purposes: It cleans up aggregates and, afterward, turns off the stress response triggered by the aggregated proteins. The stress response controlled by SIFI is switched on to deal with specific intracellular problems — the abnormal accumulation of proteins that end up at the wrong location in the cell. If components of SIFI are mutated, the cell will accumulate protein clumps and experience an active stress response. But it is the stress response signaling that kills the cells.

“The SIFI complex would normally clear out the aggregating proteins. When there are aggregates around, SIFI is diverted from the stress response, and the signaling continues. When aggregates have been cleared — the room has been cleaned up before bedtime — then the SIFI is not diverted away anymore, and it can turn off the stress response,” he said. “Aggregates kind of hijack that natural stress response-silencing mechanism, interfere with it, stall it. And so that’s why silencing never happens when you have aggregates, and that’s why cells die.”

A future treatment, Rapé said, would likely involve the administration of a drug to turn off the stress response and a drug to keep SIFI turned on to clean up the aggregate mess.

Rapé, who is also the Dr. K. Peter Hirth Chair of Cancer Biology, studies the role of ubiquitin — a ubiquitous protein in the body that targets proteins for degradation — in regulating normal and disease processes in humans. In 2017, he discovered that a protein called UBR4 assembles a specific ubiquitin signal that was required for the elimination of proteins that tend to aggregate inside cells.

Only later did other researchers find that mutations in UBR4 are found in some inherited types of neurodegeneration. This discovery led Rapé to team up with colleagues at Stanford University to find out how UBR4 causes these diseases.

“This was a unique opportunity: We had an enzyme that makes an anti-aggregation signal, and when it’s mutated, it causes aggregation disease,” he said. “You put these two things together and you can say, ‘If you figure out how this UBR4 allows sustained cell survival, that probably tells you how aggregates kill cells.'”

They found that UBR4 is actually part of a much larger protein complex, which Rapé dubbed SIFI, and they found that this SIFI machinery was needed when a cell couldn’t sort proteins into its mitochondria. Such proteins that end up at the wrong location in cells tend to clump and, in turn, cause neurodegeneration.

“Surprisingly, though, we found that the core substrates of the SIFI complex were two proteins, one of which senses when proteins don’t make it into mitochondria. That protein detects that something is wrong, and it then activates a kinase that shuts down most of new protein synthesis as part of a stress response, giving the cell time to correct its problem with bringing proteins to the right location,” he said.

This kinase is also degraded through SIFI. A kinase is an enzyme that adds a phosphate group to another molecule, in this case, a protein, to regulate important activities in the cell. By helping degrade these two proteins, the SIFI complex turns off the stress response that is caused by clumpy proteins accumulating at the wrong location.

“That’s the very first time that we’ve seen a stress response turned off in an active manner by an enzyme — SIFI — that happens to be mutated in neurodegeneration,” Rapé said.

While investigating how SIFI can turn off the stress response at the right time — only after the room had been cleaned up — the researchers found that SIFI recognizes a short protein segment that acts as a kind of ZIP code that allows proteins or protein precursors to get into the mitochondria, where they are processed. When they are prevented from getting in, they accumulate in the cytoplasm, but SIFI homes in on that ZIP code to eliminate them. The ZIP code looks just like the light switch.

“When you have aggregates accumulating in the cytoplasm, now the ZIP code is still in the cytoplasm, and there’s a lot of it there,” he said. “And it’s the same signal as you would have in the proteins that you want to turn off. So it basically diverts the SIFI complex from the light switch back to the mess. SIFI tries to clean up the mess first, and it cannot turn off the light. And so when you have an aggregate in the cell, the light is always on. And if the light is always on, if stress signaling is always on, the cell will die. And that’s a problem.”

Implications for Treatment and Future Research

Rapé suspects that many intracellular protein aggregates characteristic of neurodegenerative diseases have similar consequences and may prevent the cell from switching off the stress response. If so, the fact that a drug can turn off the response and rescue brain cells bodes well for the development of treatments for potentially many neurodegenerative diseases.

Already, another stress response inhibitor, a drug called ISRIB discovered at UCSF in 2013, has been shown to improve memory in mice and reduce age-related cognitive decline.

“That means there is the prospect that by manipulating stress silencing, by turning off the light with chemicals, you might target other neurodegenerative diseases, as well,” he said. “At the very least, it’s another way we could help patients with these diseases. In the best possible way, I think it will change how we treat neurodegenerative diseases. That’s why this is a really important story, why I think it’s very exciting.”

Rapé, already a co-founder of two startups, Nurix Therapeutics Inc., and Lyterian Therapeutics, is now looking to develop therapies to silence the stress response while maintaining the cell’s cleanup of protein aggregates.

Reference: “Stress response silencing by an E3 ligase mutated in neurodegeneration” by Diane L. Haakonsen, Michael Heider, Andrew J. Ingersoll, Kayla Vodehnal, Samuel R. Witus, Takeshi Uenaka, Marius Wernig and Michael Rapé, 31 January 2024, Nature . DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-06985-7

Co-authors with Rapé are postdoctoral fellows Diane Haakonsen, Michael Heider, and Samuel Witus and graduate student Andrew Ingersoll, all of UC Berkeley, and Kayla Vodehnal, Takeshi Uenaka, and Marius Wernig of Stanford. The work was supported primarily by the Stinehart–Reed Foundation and the National Institutes of Health (RF1 AG048131, T32MH020016-25).

More on SciTechDaily

Precision and Peril: Stunning New Image of Intuitive Machines Odysseus Landing on Moon

Challenging “Rule Breakers” – Children Will Confront Their Peers, but How They Do So Varies Across Cultures

Climate change and extreme weather will have complex effects on infectious disease transmission.

“Unusual” Findings Overturn Current Battery Wisdom

600 Million-Year-Old Time Capsule – New Discoveries From the Himalayas Shed Light on Earth’s Past

Billion Year Old Surface Water Found in Oceanic Plates

Beware the Splice of Life: This Killer Protein Causes Pancreatic Cancer

Reviving Ancient Skills to Solve Prehistoric Puzzles

Be the first to comment on "redefining dementia treatment: berkeley scientists unveil promising new breakthrough", leave a comment cancel reply.

Email address is optional. If provided, your email will not be published or shared.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

MIT Technology Review

- Newsletters

New breakthroughs on Alzheimer’s

MIT scientists have pinpointed the first brain cells to show signs of neurodegeneration in the disorder and identified a peptide that holds potential as a treatment.

- Anne Trafton archive page

Neuronal hyperactivity and the gradual loss of neuron function are key features of Alzheimer’s disease. Now researchers led by Li-Huei Tsai, director of MIT’s Picower Institute for Learning and Memory, have identified the cells most susceptible to this damage, suggesting a good target for treatment. Even more exciting, Tsai and her colleagues have found a way to reverse neurodegeneration and other symptoms by interfering with an enzyme that is typically overactive in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients.

In one study , the researchers used single-cell RNA sequencing to distinguish two populations of neurons in the mammillary bodies, a pair of structures in the hypothalamus that play a role in memory and are affected early in the disease. Previous work by Tsai’s lab found that they had the highest density of amyloid beta plaques, abnormal clumps of protein that are thought to cause many Alzheimer’s symptoms.

The researchers found that neurons in the lateral mammillary body showed much more hyperactivity and degeneration than those in the larger medial mamillary body. They also found that this damage led to memory impairments in mice and that they could reverse those impairments with a drug used to treat epilepsy.

In the other study , the researchers treated mice with a peptide that blocks a hyperactive version of an enzyme called CDK5, which plays an important role in development of the central nervous system. They found dramatic reductions in neurodegeneration and DNA damage in the brain, and the mice got better at tasks such as learning to navigate a water maze.

CDK5 is activated by a smaller protein known as P35, allowing it to add a phosphate molecule to its targets. However, in Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases, P35 breaks down into a smaller protein called P25, which allows CDK5 to phosphorylate other molecules—including the Tau protein, leading to the Tau tangles that are another characteristic of Alzheimer’s.

Pharmaceutical companies have tried to target P25 with small-molecule drugs, but these drugs also interfere with other essential enzymes. The MIT team instead used a peptide—a string of amino acids, in this case a sequence matching that of a CDK5 segment that is critical to binding P25.

In tests on neurons in a lab dish, the researchers found that treatment with the peptide moderately reduced CDK5 activity. But in a mouse model that has hyperactive CDK5, they saw myriad beneficial effects, including reductions in DNA damage, neural inflammation, and neuron loss.

The treatment also produced dramatic improvements in a different mouse model of Alzheimer’s, which has a mutant form of the Tau protein. Tsai hypothesizes that the peptide might confer resilience to cognitive impairment in the brains of people with Tau tangles.

“We found that the effect of this peptide is just remarkable,” she says. “We saw wonderful effects in terms of reducing neurodegeneration and neuroinflammatory responses, and even rescuing behavior deficits.”

The researchers hope the peptide could eventually be used as a treatment not only for Alzheimer’s but for frontotemporal dementia, HIV-induced dementia, diabetes-linked cognitive impairment, and other conditions.

Keep Reading

Most popular, how scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets.

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

- Cassandra Willyard archive page

It’s time to retire the term “user”

The proliferation of AI means we need a new word.

- Taylor Majewski archive page

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

- Casey Crownhart archive page

Sam Altman says helpful agents are poised to become AI’s killer function

Open AI’s CEO says we won’t need new hardware or lots more training data to get there.

- James O'Donnell archive page

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from mit technology review.

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.

Thank you for submitting your email!

It looks like something went wrong.

We’re having trouble saving your preferences. Try refreshing this page and updating them one more time. If you continue to get this message, reach out to us at [email protected] with a list of newsletters you’d like to receive.

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

How do you read organization’s silence over rise of Nazism?

Got milk? Does it give you problems?

Cancer risk, wine preference, and your genes

Start of new era for alzheimer’s treatment.

Alvin Powell

Harvard Staff Writer

Expert discusses recent lecanemab trial, why it appears to offer hope for those with deadly disease

Researchers say we appear to be at the start of a new era for Alzheimer’s treatment. Trial results published in January showed that for the first time a drug has been able to slow the cognitive decline characteristic of the disease. The drug, lecanemab, is a monoclonal antibody that works by binding to a key protein linked to the malady, called amyloid-beta, and removing it from the body. Experts say the results offer hope that the slow, inexorable loss of memory and eventual death brought by Alzheimer’s may one day be a thing of the past.

The Gazette spoke with Scott McGinnis , an assistant professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School and Alzheimer’s disease expert at Brigham and Women’s Hospital , about the results and a new clinical trial testing whether the same drug given even earlier can prevent its progression.

Scott McGinnis

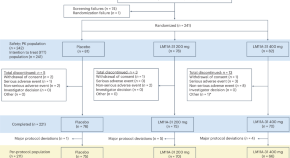

GAZETTE: The results of the Clarity AD trial have some saying we’ve entered a new era in Alzheimer’s treatment. Do you agree?

McGINNIS: It’s appropriate to consider it a new era in Alzheimer’s treatment. Until we obtained the results of this study, trials suggested that the only mode of treatment was what we would call a “symptomatic therapeutic.” That might give a modest boost to cognitive performance — to memory and thinking and performance in usual daily activities. But a symptomatic drug does not act on the fundamental pathophysiology, the mechanisms, of the disease. The Clarity AD study was the first that unambiguously suggested a disease-modifying effect with clear clinical benefit. A couple of weeks ago, we also learned a study with a second drug, donanemab, yielded similar results.

GAZETTE: Hasn’t amyloid beta, which forms Alzheimer’s characteristic plaques in the brain and which was the target in this study, been a target in previous trials that have not been effective?

McGINNIS: That’s true. Amyloid beta removal has been the most widely studied mechanism in the field. Over the last 15 to 20 years, we’ve been trying to lower beta amyloid, and we’ve been uncertain about the benefits until this point. Unfavorable results in study after study contributed to a debate in the field about how important beta amyloid is in the disease process. To be fair, this debate is not completely settled, and the results of Clarity AD do not suggest that lecanemab is a cure for the disease. The results do, however, provide enough evidence to support the hypothesis that there is a disease-modifying effect via amyloid removal.

GAZETTE: Do we know how much of the decline in Alzheimer’s is due to beta amyloid?

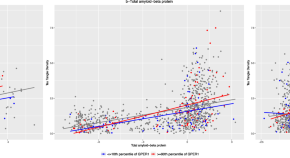

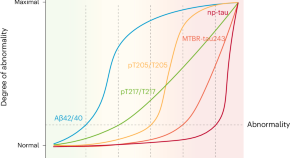

McGINNIS: There are two proteins that define Alzheimer’s disease. The gold standard for diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease is identifying amyloid beta plaques and tau neurofibrillary tangles. We know that amyloid beta plaques form in the brain early, prior to accumulation of tau and prior to changes in memory and thinking. In fact, the levels and locations of tau accumulation correlate much better with symptoms than the levels and locations of amyloid. But amyloid might directly “fuel the fire” to accelerated changes in tau and other downstream mechanisms, a hypothesis supported by basic science research and the findings in Clarity AD that treatment with lecanemab lowered levels of not just amyloid beta but also levels of tau and neurodegeneration in the blood and cerebrospinal fluid.

GAZETTE: In the Clarity AD trial, what’s the magnitude of the effect they saw?

McGINNIS: The relevant standards in the trial — set by the FDA and others — were to see two clinical benefits for the drug to be considered effective. One was a benefit on tests of memory and thinking, a cognitive benefit. The other was a benefit in terms of the performance in usual daily activities, a functional benefit. Lecanemab met both of these standards by slowing the rate of decline by approximately 25 to 35 percent compared to placebo on measures of cognitive and functional decline over the 18-month studies.

“In a perfect world, we’d have treatments that completely stop decline and even restore function. We’re not there yet, but this represents an important step toward that goal.”

Steven M. Smith

GAZETTE: What are the key questions that remain?

McGINNIS: An important question relates to the stages at which the interventions were done. The study was done in subjects with mild cognitive impairment and mild Alzheimer dementia. People who have mild cognitive impairment have retained their independence in instrumental activities of daily living — for example, driving, taking medications, managing finances, errands, chores — but have cognitive and memory changes beyond what we would attribute to normal aging. When people transition to mild dementia, they’re a bit further along. The study was for people within that spectrum but there’s some reason to believe that intervening even earlier might be more effective, as is the case with many other medical conditions.

We’re doing a study here called the AHEAD study that is investigating the effects of lecanemab when administered earlier, in cognitively normal individuals who have elevated brain amyloid, to see whether we see a preventative benefit. The hope is that we would at least see a delay to onset of cognitive impairment and a favorable effect not only on amyloid biomarkers, but other biomarkers that might capture progression of the disease.

GAZETTE: Is anybody in that study treatment yet or are you still enrolling?

McGINNIS: There’s a rolling enrollment, so there are people who are in the double-blind phase of treatment, receiving either the drug or the placebo. But the enrollment target hasn’t been reached yet so we’re still accepting new participants.

GAZETTE: Is it likely that we may see drug cocktails that go after tau and amyloid? Is that a future approach?

More like this

Newly identified genetic variant protects against Alzheimer’s

Using AI to target Alzheimer’s

Excessive napping and Alzheimer’s linked in study

McGINNIS: It has not yet been tried, but those of us in the field are very excited at the prospect of these studies. There’s been a lot of work in recent years on developing therapeutics that target tau, and I think we’re on the cusp of some important breakthroughs. This is key, considering evidence that spreading of tau from cell to cell might contribute to progression of the disease. Additionally, for some time, we’ve had a suspicion that we will likely have to target multiple different aspects of the disease process, as is the case with most types of cancer treatment. Many in our field believe that we will obtain the most success when we identify the most pertinent mechanisms for subgroups of people with Alzheimer’s disease and then specifically target those mechanisms. Examples might include metabolic dysfunction, inflammation, and problems with elements of cellular processing, including mitochondrial functioning and processing old or damaged proteins. Multi-drug trials represent a natural next step.

GAZETTE: What about side effects from this drug?

McGINNIS: We’ve known for a long time that drugs in this class, antibodies that harness the power of the immune system to remove amyloid, carry a risk of causing swelling in the brain. In most cases, it’s asymptomatic and just detected by MRI scan. In Clarity AD, while 12 to 13 percent of participants receiving lecanemab had some level of swelling detected by MRI, it was symptomatic in only about 3 percent of participants and mild in most of those cases.

Another potential side effect is bleeding in the brain or on the surface of the brain. When we see bleeding, it’s usually very small, pinpoint areas of bleeding in the brain that are also asymptomatic. A subset of people with Alzheimer’s disease who don’t receive any treatment are going to have these because they have amyloid in their blood vessels, and it’s important that we screen for this with an MRI scan before a person receives treatment. In Clarity AD, we saw a rate of 9 percent in the placebo group and about 17 percent in the treatment group, many of those cases in conjunction with swelling and mostly asymptomatic.

The scenario that everybody worries about is a hemorrhagic stroke, a larger area of bleeding. That was much less common in this study, less than 1 percent of people. Unlike similar studies, this study allowed subjects to be on anticoagulation medications, which thin the blood to prevent or treat clots. The rate of macro hemorrhage — larger bleeds — was between 2 and 3 percent in the anticoagulated participants. There were some highly publicized cases including a patient who had a stroke, presented for treatment, received a medication to dissolve clots, then had a pretty bad hemorrhage. If the drug gets full FDA approval, is covered by insurance, and becomes clinically available, most physicians are probably not going to give it to people who are on anticoagulation. These are questions that we’ll have to work out as we learn more about the drug from ongoing research.

GAZETTE: Has this study, and these recent developments in the field, had an effect on patients?

McGINNIS: It has had a considerable impact. There’s a lot of interest in the possibility of receiving this drug or a similar drug, but our patients and their family members understand that this is not a cure. They understand that we’re talking about slowing down a rate of decline. In a perfect world, we’d have treatments that completely stop decline and even restore function. We’re not there yet, but this represents an important step toward that goal. So there’s hope. There’s optimism. Our patients, particularly patients who are at earlier stages of the disease, have their lives to live and are really interested in living life fully. Anything that can help them do that for a longer period of time is welcome.

Share this article

You might like.

Medical historians look to cultural context, work of peer publications in wrestling with case of New England Journal of Medicine

Biomolecular archaeologist looks at why most of world’s population has trouble digesting beverage that helped shape civilization

Biologist separates reality of science from the claims of profiling firms

Epic science inside a cubic millimeter of brain

Researchers publish largest-ever dataset of neural connections

Finding right mix on campus speech policies

Legal, political scholars discuss balancing personal safety, constitutional rights, academic freedom amid roiling protests, cultural shifts

Good genes are nice, but joy is better

Harvard study, almost 80 years old, has proved that embracing community helps us live longer, and be happier

Appointments at Mayo Clinic

Alzheimer's treatments: what's on the horizon.

Despite many promising leads, new treatments for Alzheimer's are slow to emerge.

Current Alzheimer's treatments temporarily improve symptoms of memory loss and problems with thinking and reasoning.

These Alzheimer's treatments boost the performance of chemicals in the brain that carry information from one brain cell to another. They include cholinesterase inhibitors and the medicine memantine (Namenda). However, these treatments don't stop the underlying decline and death of brain cells. As more cells die, Alzheimer's disease continues to progress.

Experts are cautious but hopeful about developing treatments that can stop or delay the progression of Alzheimer's. Experts continue to better understand how the disease changes the brain. This has led to the research of potential Alzheimer's treatments that may affect the disease process.

Future Alzheimer's treatments may include a combination of medicines. This is similar to treatments for many cancers or HIV / AIDS that include more than one medicine.

These are some of the strategies currently being studied.

Taking aim at plaques

Some of the new Alzheimer's treatments target clumps of the protein beta-amyloid, known as plaques, in the brain. Plaques are a characteristic sign of Alzheimer's disease.

Strategies aimed at beta-amyloid include:

Recruiting the immune system. Medicines known as monoclonal antibodies may prevent beta-amyloid from clumping into plaques. They also may remove beta-amyloid plaques that have formed. They do this by helping the body clear them from the brain. These medicines mimic the antibodies your body naturally produces as part of your immune system's response to foreign invaders or vaccines.

In 2023, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved lecanemab (Leqembi) for people with mild Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease.

A phase 3 clinical trial found that the medicine slowed cognitive decline in people with early Alzheimer's disease. The medicine prevents amyloid plaques in the brain from clumping. The phase 3 trial was the largest so far to study whether clearing clumps of amyloid plaques from the brain can slow the disease.

Lecanemab is given as an IV infusion every two weeks. Your care team likely will watch for side effects and ask you or your caregiver how your body reacts to the drug. Side effects of lecanemab include infusion-related reactions such as fever, flu-like symptoms, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, changes in heart rate and shortness of breath.

Also, people taking lecanemab may have swelling in the brain or may get small bleeds in the brain. Rarely, brain swelling can be serious enough to cause seizures and other symptoms. Also in rare instances, bleeding in the brain can cause death. The FDA recommends getting a brain MRI before starting treatment. It also recommends being monitored with brain MRI s during treatment for symptoms of brain swelling or bleeding.

People who carry a certain form of a gene known as APOE e4 appear to have a higher risk of these serious complications. The FDA recommends being tested for this gene before starting treatment with lecanemab.

If you take a blood thinner or have other risk factors for brain bleeding, talk to your health care professional before taking lecanemab. Blood-thinning medicines may increase the risk of bleeds in the brain.

More research is being done on the potential risks of taking lecanemab. Other research is looking at how effective lecanemab may be for people at risk of Alzheimer's disease, including people who have a first-degree relative, such as a parent or sibling, with the disease.

Another medicine being studied is donanemab. It targets and reduces amyloid plaques and tau proteins. It was found to slow declines in thinking and functioning in people with early Alzheimer's disease.

The monoclonal antibody solanezumab did not show benefits for individuals with preclinical, mild or moderate Alzheimer's disease. Solanezumab did not lower beta-amyloid in the brain, which may be why it wasn't effective.

Preventing destruction. A medicine initially developed as a possible cancer treatment — saracatinib — is now being tested in Alzheimer's disease.

In mice, saracatinib turned off a protein that allowed synapses to start working again. Synapses are the tiny spaces between brain cells through which the cells communicate. The animals in the study experienced a reversal of some memory loss. Human trials for saracatinib as a possible Alzheimer's treatment are now underway.

Production blockers. These therapies may reduce the amount of beta-amyloid formed in the brain. Research has shown that beta-amyloid is produced from a "parent protein" in two steps performed by different enzymes.

Several experimental medicines aim to block the activity of these enzymes. They're known as beta- and gamma-secretase inhibitors. Recent studies showed that the beta-secretase inhibitors did not slow cognitive decline. They also were associated with significant side effects in those with mild or moderate Alzheimer's. This has decreased enthusiasm for the medicines.

Keeping tau from tangling

A vital brain cell transport system collapses when a protein called tau twists into tiny fibers. These fibers are called tangles. They are another common change in the brains of people with Alzheimer's. Researchers are looking at a way to prevent tau from forming tangles.

Tau aggregation inhibitors and tau vaccines are currently being studied in clinical trials.

Reducing inflammation

Alzheimer's causes chronic, low-level brain cell inflammation. Researchers are studying ways to treat the processes that lead to inflammation in Alzheimer's disease. The medicine sargramostim (Leukine) is currently in research. The medicine may stimulate the immune system to protect the brain from harmful proteins.

Researching insulin resistance

Studies are looking into how insulin may affect the brain and brain cell function. Researchers are studying how insulin changes in the brain may be related to Alzheimer's. However, a trial testing of an insulin nasal spray determined that the medicine wasn't effective in slowing the progression of Alzheimer's.

Studying the heart-head connection

Growing evidence suggests that brain health is closely linked to heart and blood vessel health. The risk of developing dementia appears to increase as a result of many conditions that damage the heart or arteries. These include high blood pressure, heart disease, stroke, diabetes and high cholesterol.

A number of studies are exploring how best to build on this connection. Strategies being researched include:

- Current medicines for heart disease risk factors. Researchers are looking into whether blood pressure medicines may benefit people with Alzheimer's. They're also studying whether the medicines may reduce the risk of dementia.

- Medicines aimed at new targets. Other studies are looking more closely at how the connection between heart disease and Alzheimer's works at the molecular level. The goal is to find new potential medicines for Alzheimer's.

- Lifestyle choices. Research suggests that lifestyle choices with known heart benefits may help prevent Alzheimer's disease or delay its onset. Those lifestyle choices include exercising on most days and eating a heart-healthy diet.

Studies during the 1990s suggested that taking hormone replacement therapy during perimenopause and menopause lowered the risk of Alzheimer's disease. But further research has been mixed. Some studies found no cognitive benefit of taking hormone replacement therapy. More research and a better understanding of the relationship between estrogen and cognitive function are needed.

Speeding treatment development

Developing new medicines is a slow process. The pace can be frustrating for people with Alzheimer's and their families who are waiting for new treatment options.

To help speed discovery, the Critical Path for Alzheimer's Disease (CPAD) consortium created a first-of-its-kind partnership to share data from Alzheimer's clinical trials. CPAD 's partners include pharmaceutical companies, nonprofit foundations and government advisers. CPAD was formerly called the Coalition Against Major Diseases.

CPAD also has collaborated with the Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium to create data standards. Researchers think that data standards and sharing data from thousands of study participants will speed development of more-effective therapies.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

- Treatments and research. Alzheimer's Association. https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/research_progress/treatment-horizon. Accessed March 23, 2023.

- Cummings J, et al. Alzheimer's disease drug development pipeline: 2022. Alzheimer's and Dementia. 2022; doi:10.1002/trc2.12295.

- Burns S, et al. Therapeutics of Alzheimer's disease: Recent developments. Antioxidants. 2022; doi:10.3390/antiox11122402.

- Plascencia-Villa G, et al. Lessons from antiamyloid-beta immunotherapies in Alzheimer's disease. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 2023; doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-85555-6.00019-9.

- Brockmann R, et al. Impacts of FDA approval and Medicare restriction on antiamyloid therapies for Alzheimer's disease: Patient outcomes, healthcare costs and drug development. The Lancet Regional Health. 2023; doi:10.1016/j.lana. 2023.100467 .

- Wojtunik-Kulesza K, et al. Aducanumab — Hope or disappointment for Alzheimer's disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023; doi:10.3390/ijms24054367.

- Can Alzheimer's disease be prevented? Alzheimer's Association. http://www.alz.org/research/science/alzheimers_prevention_and_risk.asp. Accessed March 23, 2023.

- Piscopo P, et al. A systematic review on drugs for synaptic plasticity in the treatment of dementia. Ageing Research Reviews. 2022; doi:10.1016/j.arr. 2022.101726 .

- Facile R, et al. Use of Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium (CDISC) standards for real-world data: Expert perspectives from a qualitative Delphi survey. JMIR Medical Informatics. 2022; doi:10.2196/30363.

- Imbimbo BP, et al. Role of monomeric amyloid-beta in cognitive performance in Alzheimer's disease: Insights from clinical trials with secretase inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies. Pharmacological Research. 2023; doi:10.1016/j.phrs. 2022.106631 .

- Conti Filho CE, et al. Advances in Alzheimer's disease's pharmacological treatment. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2023; doi:10.3389/fphar. 2023.1101452 .

- Potter H, et al. Safety and efficacy of sargramostim (GM-CSF) in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's and Dementia. 2021; doi:10.1002/trc2.12158.

- Zhong H, et al. Effect of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonists on cognitive function: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomedicines. 2023; doi:10.3390/biomedicines11020246.

- Grodstein F. Estrogen and cognitive function. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed March 23, 2023.

- Mills ZB, et al. Is hormone replacement therapy a risk factor or a therapeutic option for Alzheimer's disease? International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023; doi:10.3390/ijms24043205.

- Custodia A, et al. Biomarkers assessing endothelial dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease. Cells. 2023; doi:10.3390/cells12060962.

- Overview. Critical Path for Alzheimer's Disease. https://c-path.org/programs/cpad/. Accessed March 29, 2023.

- Shi M, et al. Impact of anti-amyloid-β monoclonal antibodies on the pathology and clinical profile of Alzheimer's disease: A focus on aducanumab and lecanemab. Frontiers in Aging and Neuroscience. 2022; doi:10.3389/fnagi. 2022.870517 .

- Leqembi (approval letter). Biologic License Application 761269. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&ApplNo=761269. Accessed July 7, 2023.

- Van Dyck CH, et al. Lecanemab in early Alzheimer's disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2023; doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2212948.

- Leqembi (prescribing information). Eisai; 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&varApplNo=761269. Accessed July 10, 2023.

Products and Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic on Alzheimer's Disease

- Assortment of Products for Independent Living from Mayo Clinic Store

- A Book: Day to Day: Living With Dementia

- A Book: Mayo Clinic on Healthy Aging

- Give today to find Alzheimer's cures for tomorrow

- Alzheimer's sleep problems

- Alzheimer's 101

- Understanding the difference between dementia types

- Alzheimer's disease

- Alzheimer's genes

- Alzheimer's drugs

- Alzheimer's prevention: Does it exist?

- Alzheimer's stages

- Antidepressant withdrawal: Is there such a thing?

- Antidepressants and alcohol: What's the concern?

- Antidepressants and weight gain: What causes it?

- Antidepressants: Can they stop working?

- Antidepressants: Side effects

- Antidepressants: Selecting one that's right for you

- Antidepressants: Which cause the fewest sexual side effects?

- Anxiety disorders

- Atypical antidepressants

- Caregiver stress

- Clinical depression: What does that mean?

- Corticobasal degeneration (corticobasal syndrome)

- Depression and anxiety: Can I have both?

- Depression, anxiety and exercise

- What is depression? A Mayo Clinic expert explains.

- Depression in women: Understanding the gender gap

- Depression (major depressive disorder)

- Depression: Supporting a family member or friend

- Diagnosing Alzheimer's

- Did the definition of Alzheimer's disease change?

- How your brain works

- Intermittent fasting

- Lecanemab for Alzheimer's disease

- Male depression: Understanding the issues

- MAOIs and diet: Is it necessary to restrict tyramine?

- Marijuana and depression

- Mayo Clinic Minute: 3 tips to reduce your risk of Alzheimer's disease

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Alzheimer's disease risk and lifestyle

- Mayo Clinic Minute: New definition of Alzheimer's changes

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Women and Alzheimer's Disease

- Memory loss: When to seek help

- Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs)

- Natural remedies for depression: Are they effective?

- Nervous breakdown: What does it mean?

- New Alzheimers Research

- Pain and depression: Is there a link?

- Phantosmia: What causes olfactory hallucinations?

- Positron emission tomography scan

- Posterior cortical atrophy

- Seeing inside the heart with MRI

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

- Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)

- Sundowning: Late-day confusion

- Treatment-resistant depression

- Tricyclic antidepressants and tetracyclic antidepressants

- Video: Alzheimer's drug shows early promise

- Vitamin B-12 and depression

- Young-onset Alzheimer's

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

- Alzheimer s treatments What s on the horizon

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

- Latest Latest

- The West The West

- Sports Sports

- Opinion Opinion

- Magazine Magazine

Utahn may be on verge of a significant breakthrough in treating Alzheimer’s

University of utah research professor donna j. cross has helped mice overcome brain disorders. are humans next.

By Lee Benson

Is a research professor at the University of Utah on the verge of a significant breakthrough in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and other brain disorders?

Not only would a bunch of lab mice vote yes, they’d remember to do so.

Donna J. Cross, who has a doctoral degree in neuroscience, has spent the past 25 years shepherding research that favorably suggests a small, specialized dose of a chemotherapy drug called Paclitaxel might be capable of repairing injuries, whether caused by pathology or by trauma, to the human brain.

The quest began at the University of Michigan, where Cross earned her doctorate, then to the University of Washington when she joined that faculty, and finally to the University of Utah, when Cross’ mentor and the man who began the research, Dr. Satoshi Minoshima, came to the U. as chair of the department of radiology and imaging sciences.

In a nutshell, when the scientists have administered their version of the cancer drug to mice that have been bred to develop Alzheimer’s, the mice have experienced “a complete reversal of their cognitive deficit.” Same thing happened when mice that had suffered concussions were given the medication.

Suddenly, mice that couldn’t remember things and/or had traumatic brain injury were acting cognitively normal again.

“Whether that would happen in humans, we have a lot of work still to do,” says Cross. But if it did? She doesn’t equivocate. “It would be huge.”

This is personal for Donna Cross. Like so many of us, she knows what it’s like to watch loved ones suffer from brain diseases. Her grandmother’s Alzheimer’s diagnosis was her chief motivation for joining Minoshima’s team when she started graduate school. Recently, a father-in-law with severe dementia has only heightened her sense of urgency.

“Even though it’s too late for my grandmother and likely too late for my father-in-law, it’s not too late for vast, vast numbers of people in the world,” she says, “that’s why we have to keep moving forward.”

Still, scientific research takes time and money. With dwindling amounts of both when she came to the University of Utah (Alzheimer’s research isn’t her only iron in the fire), Cross confesses she was “almost ready to give up.”

She desperately needed help in repurposing Paclitaxel into a form that could be applied to the human brain and didn’t know where to turn.

Once she’d settled into her lab at the U. she did a Google search to see if any pharmaceutical scientists might be in the area.

That’s when she discovered she’d been given an office, quite randomly, in the Biomedical Polymers Research Building, where the world-renowned Czech-born pharmaceutical chemist Jindrich (Henry) Kopecek has set up his headquarters.

The drug makers she needed were literally right next door.

Kopecek and Dr. Jiyuan (Jane) Yang have been integrally involved ever since, lending their expertise in figuring out how to develop and safely deliver to the brain a potential game-changing drug.

“I’m just very, very lucky to be placed in their building for no other reason than they had space,” says Cross. “These guys are rock stars. I came to them as a brain person who was interested in treating neurological conditions and they are the drug developer/drug delivery people. It’s a collaboration that is very strong because of our different areas of expertise.”

The goal now is to get the drug developed and ready for clinical trials. It will be costly — Cross estimates they need to raise at least $2 million — but the potential upside could be priceless.

“We would treat not just Alzheimer’s,” she says, “but also any kind of dementia: ALS, Parkinson’s, multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury, any kind of condition where nerve cells are dying.”

In a best case scenario, not only would the neurological damage be halted, but the brain would conceivably be healed.

How long will it take to find out? As long as it takes, says Cross. “This is my passion. It started out personal to me; it still is, extremely so.”

This week Cross will be giving a presentation about her work at the free Alzheimer’s & Caregiving Education Conference scheduled to be held Wednesday, May 15, from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. at the Embassy Suites Hotel in West Valley City. The conference, hosted by the Alzheimer’s Foundation of America, is open to the public.

“My motivation for doing these public lectures is twofold: one, to draw attention to the work we’re doing, and two, to give hope,” says Cross. “I think it’s extremely important that people have hope.”

To register in advance for the conference, go to www.alzfdn.org/tour . You can stay connected with Cross’ research by following @UofURadiology.

Research Offers New Ideas for Treating Alzheimer’s

“out-of-the-clump,” mitochondrial, and other theories offer hope on alzheimer’s..

Posted May 17, 2024 | Reviewed by Tyler Woods

- What Is Dementia?

- Find counselling to help with dementia

- The need for a new "out-of-the-clump" way of thinking about AD is emerging as a top priority in brain science.

- In Alzheimer’s, the brain’s immune system fails to differentiate between bacteria and brain cells.

- Probiotics may not only support a healthier gut, but a healthier brain as well.

- For the elderly, in particular those with cognitive impairment, good oral hygiene is essential.

Dementia refers to an array of symptoms characterized by failing short-term memory , confused thinking, and a decline in language skills. Of all the dementias, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) constitutes approximately 60 to 80 percent of cases.

Two drugs, Lecanemab and Donanemab, have been hailed as part of a new class of monoclonal antibody (MOA) drugs that could mark a turning point for Alzheimer’s (AZ) drug research. These drugs are incredibly expensive and carry risks of brain microbleeds and swelling. More importantly, they do not cure or even halt the disease, they delay it by about six months on average. At least 98 unique compounds tested in Phase 2 or 3 trials that pursued the various MOA classes have failed over the years. Howard Chertow, of McGill University, commented, “They’re not a home run.”

Personally, I think they’re more like a strike-out, in view of the fact that most neuroscientists and the drug companies employed by them may be looking in the wrong places in the wrong way.

In 2006, a research paper published in the highly regarded journal Nature asserted that the development of Alzheimer’s is caused by the formation in the brain of abnormally high levels of the naturally occurring protein beta-amyloid that clumps together to form plaques and the intracellular accumulations of neurofibrillary tangles of tau protein that disrupt cell function.

In 2023, a critical review in the journal Brain , collaboratively written by scientists from Denmark, the U.S., Italy, and Australia, stated that “Despite the importance of amyloid in the definition of Alzheimer's disease, we argue that the data point to Aβ playing a minor aetiological role.” They further asserted that the search for more effective ways to treat Alzheimer’s should involve more than amyloid as the single causative agent.

I propose to discuss the currently leading "out-of-the-clump" research, a term coined by Donald Weaver of the University of Toronto, that may eventually usher in new and better ways of dealing with Alzheimer’s.

One of the most auspicious of these novel directions comes from the above-mentioned Weaver, who found that significant resemblances between bacterial membranes and brain cell membranes exist. Beta-amyloid erroneously mistakes the brain cells for invading bacteria and attacks them. These brain cells gradually decay, ultimately leading to dementia. According to Weaver, Alzheimer’s is an autoimmune disease.

If this theory gains traction in the scientific world, treatments that are effective in autoimmune diseases such as celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, diabetes type 1, eczema, etc. may prove successful in the treatment of Alzheimer’s.

In addition to this autoimmune theory of Alzheimer’s, many other new and varied theories are appearing. John Mamo of Curtin University in Australia, demonstrated already in 2021 that the liver also makes amyloid protein.

It follows that finding ways to either prevent the liver from manufacturing the amyloid protein or destroying it before it enters the circulation ought to be explored.

A recent study from Portugal suggests that Alzheimer’s is a disease of the mitochondria . Mitochondria are tiny organelles (similar to organs like the heart or liver but much smaller inside cells) that generate most of the chemical energy required to power the cell's functions. The authors of this study reported positive outcomes in Alzheimer’s with animals fed a diet rich in antioxidants.

This is good news because we are in familiar territory here. We have known for a long time that antioxidants scavenge free radicals from the body cells and prevent or reduce the damage caused by oxidation. Of course, further research is necessary before it is proven that antioxidants in humans can lessen the risk of developing Alzheimer’s or benefit people in the early stages of Alzheimer’s. However, the consumption of antioxidants like vitamins A, C, and E, the minerals copper, zinc, and selenium, as well as nuts, fruits and vegetables, pecans, blueberries, and dark chocolate, seems well-proven to benefit the health of everyone, at any stage of life.

Scientists from the University of Bern, Switzerland, contend that Alzheimer’s is the end result of a brain infection, particularly with bacteria from the mouth. Since our hands and fingers swarm with viruses and bacteria, a recent paper that advanced the hypothesis that nose picking could play a role in increasing the risk of developing Alzheimer’s makes much sense. Digging around our noses is encouraging all those little critters to hop on the olfactory nerve train and take a vacation in our brains.

Recent research has focussed on probiotics as potentially beneficial in preventing the development or slowing the progression of Alzheimer’s. Probiotics are foods or supplements that contain live microorganisms that help to maintain or improve a diverse microflora in the gut. A systematic review of the literature on the effect of probiotics on Alzheimer’s by scientists from Malaysia in conjunction with researchers from Baghdad in 2022 write, “Probiotics are known to be one of the best preventative measures against cognitive decline in AD. Numerous in vivo trials and recent clinical trials have proven the effectiveness of selected bacterial strains in slowing down the progression of AD. It is proven that probiotics modulate the inflammatory process, counteract [with] oxidative stress , and modify gut microbiota.”

This and many other academic papers present robust evidence on the role of probiotics in alleviating the progression of Alzheimer’s.

As opposed to drugs, probiotics are readily available in foods such as yogurt, buttermilk, sauerkraut, pickles, and many others.

If we are going to make significant advances in the prevention and treatment of Alzheimer’s, we urgently require new approaches outside the old amyloid plaque box. Here I reviewed a number of such studies that promise to make a difference in the near future.

Understanding the condition, its origins, and effective strategies for prevention should be a top priority of our healthcare system.

Lee, Y. R., Ong, L., Gold, M., Kalali, A., & Sarkar, J. (2022). Alzheimer’s disease: key insights from two decades of clinical trial failures. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 87(1), 83-100.

Van Dyck, C. H., Swanson, C. J., Aisen, P., Bateman, R. J., Chen, C., Gee, M., ... & Iwatsubo, T. (2023). Lecanemab in early Alzheimer’s disease. New England Journal of Medicine, 388(1), 9-21.

Romanenko, M., Kholin, V., Koliada, A., & Vaiserman, A. (2021). Nutrition, gut microbiota, and Alzheimer's disease. Frontiers in psychiatry, 12, 712673

Prater, K. E., Green, K. J., Smith, C. L., ... & Jayadev, S. (2023). Human microglia show unique transcriptional changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature Aging, 3(7), 894-907.

Thomas R. Verny, M.D. , the author of eight books, including The Embodied Mind , has taught at Harvard University, University of Toronto, York University, and St. Mary’s University of Minnesota. His podcast, Pushing Boundaries , may be viewed on Youtube or listened to on Spotify and many other platforms.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- International

- New Zealand

- South Africa

- Switzerland

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

As populations age, Alzheimer’s and dementia are becoming more prevalent. A new drug could offer hope

As populations age, the number of cases of dementia rises. Image: Unsplash/centelm

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Charlotte Edmond

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Global Health is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, global health.

Listen to the article

- A new drug, lecanemab, has been shown to reduce the decline in memory and thinking associated with Alzheimer's.

- As populations age, dementia cases are on the rise, with 10 million new people diagnosed each year.

- Dementia is a collective term for a group of diseases or brain injuries that can lead to a change in cognitive functioning as well as other symptoms like lack of emotional control.

It is one of the biggest diseases of our time: 10 million new cases of dementia are diagnosed every year, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). More than 55 million people worldwide live with a form of dementia and it is the seventh leading cause of death among all diseases.

Now a new drug is offering a glimmer of hope after years of searching for a treatment. In clinical trials, lecanemab has been shown to slow the cognitive decline associated with the disease. The drug attacks the protein clumps in the brain that many think are the cause of the disease.

Although dementia patients are currently offered drugs, none of them affect the progression of the disease which is why scientists in the field are so excited about this latest development. Alzheimer's Research UK called the findings "a major step forwards" .

But while this is undoubtedly positive news, the body also points out that the benefits of the drug were small and came with significant side effects. In addition, lecanemab has been proven to work in the early stages of the disease, so would rely on doctors spotting it before it had progressed too far.

With the number of dementia cases expected to rise to 78 million by 2030 and 139 million in 2050, according to the WHO, the race is on for scientific developments and research that will help us understand, treat and possibly prevent the disease.

A global impact

As populations age, the number of cases of dementia rises. While the deterioration of cognitive functioning is not caused by age itself, it does primarily affect the older generation. For many elderly people it also results in disability and loss of independence - which can have psychological, social and economic implications for them and their families, carers and society more broadly.

The estimated global cost of dementia to society was placed at $1.3 trillion in 2019, and is expected to rise to $2.8 trillion by 2030, WHO says.

Alzheimer’s Diesease, a result of rapid ageing that causes dementia, is a growing concern. Dementia, the seventh leading cause of death worldwide, cost the world $1.25 trillion in 2018, and affected about 50 million people in 2019. Without major breakthroughs, the number of people affected will triple by 2050, to 152 million.

To catalyse the fight against Alzheimer's, the World Economic Forum is partnering with the Global CEO Initiative (CEOi) to form a coalition of public and private stakeholders – including pharmaceutical manufacturers, biotech companies, governments, international organizations, foundations and research agencies.

The initiative aims to advance pre-clinical research to advance the understanding of the disease, attract more capital by lowering the risks to investment in biomarkers, develop standing clinical trial platforms, and advance healthcare system readiness in the fields of detection, diagnosis, infrastructure and access.

What is dementia?

Dementia is a collective term for a group of diseases or injuries which primarily or secondarily affect the brain. Alzheimer’s is the most common of these and accounts for around 60-70% of cases. Other types include vascular dementia , dementia with Lewy bodies (abnormal protein clumps) and a group of diseases that contribute to frontotemporal dementia. It can also be triggered by strokes, excessive use of alcohol, repetitive head injuries, nutritional deficiencies, or follow some infections like HIV, the Alzheimer’s Society explains.

The different forms of dementia can often be indistinct and can co-exist.

Different people are affected in different ways, depending on the underlying cause. But the syndrome is usually progressive and can affect a range of functions, including memory, thinking, orientation, comprehension, calculation, learning capacity, language and judgement.

Changes in mood and ability to control emotions often accompany these cognitive variations.

Can it be treated?

There is no cure for dementia, although there are numerous treatments being worked on and at clinical trial phase. Dementia care currently focuses on early diagnosis, optimizing health and wellbeing and providing long-term support to carers.

Besides age, there are a number of other risk factors, which if avoided, can decrease the chances of dementia and slow its progression. Preventative steps include being physically active, not smoking, avoiding the harmful use of alcohol, as well as maintaining a healthy diet, weight, blood pressure, cholesterol and blood sugar levels.

Other risk factors associated with dementia include depression, social isolation, low educational attainment, cognitive inactivity and even air pollution .

What is the impact?

People with dementia rely heavily on informal care - i.e., friends and family. These carers spent on average five hours a day looking after people living with dementia in 2019, according to WHO figures. Informal care is thought to cover half of the overall financial burden of dementia.

There is also a disproportionate impact on women. They account for 65% of all dementia-related deaths, and also have a greater number of years affected by the disease. Women also typically provide the majority of informal care - covering over two-thirds of the carer hours for people living with dementia.

What are the latest developments?

The fact that dementia is only diagnosed once symptoms appear means that by the time people take part in clinical trials the disease is often quite well advanced. This can hamper the development of drugs. However, research analyzing data from the UK Biobank has indicated there are a collection of signals that could indicate a problem years before dementia is currently being diagnosed .

Other scientists postulate that, rather than being a disease of the brain, Alzheimer’s is in fact a disorder of the immune system within the brain . They believe research should instead focus on drugs targeting auto-immune pathways .

On a less positive note, researchers found that people who have recently received a dementia diagnosis, or diagnosed with the condition at a younger age, are at an increased risk of suicide . This underlines the importance of a strong support network, particularly among those newly diagnosed.

Have you read?

Here’s how exercise alters our brain chemistry – and could prevent dementia, dementia cases are expected to double in many countries over the next 30 years, these 7 simple habits could halve your risk of dementia, don't miss any update on this topic.

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Wellbeing and Mental Health .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

The fascinating link between biodiversity and mental wellbeing

Andrea Mechelli

May 15, 2024

How philanthropy is empowering India's mental health sector

Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw

May 2, 2024

From 'Quit-Tok' to proximity bias, here are 11 buzzwords from the world of hybrid work

Kate Whiting

April 17, 2024

Young people are becoming unhappier, a new report finds

Promoting healthy habit formation is key to improving public health. Here's why

Adrian Gore

April 15, 2024

What's 'biophilic design' and how can it benefit neurodivergent people?

Fatemeh Aminpour, Ilan Katz and Jennifer Skattebol

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

New Alzheimer’s drug slows cognitive decline by 35%, trial results show

Donanemab is second drug in a year to succeed in trials in what could be ‘beginning of the end’ of disease

A new Alzheimer’s drug slowed cognitive decline by 35%, according to late-stage trial results, raising the prospect of a second effective treatment for the disease.

Donanemab met all goals of the trial and slowed progression of the condition by 35% to 36% compared with a placebo in 1,182 people with early-stage Alzheimer’s, the drugmaker Lilly said.

It comes after trial results published last year showed that lecanemab , made by Eisai and Biogen, reduced the rate of cognitive decline by 27% in patients with early Alzheimer’s.

“This could be the beginning of the end of Alzheimer’s disease,” said Dr Richard Oakley, the associate director of research at the Alzheimer’s Society in the UK. “After 20 years with no new Alzheimer’s drugs, we now have two potential new drugs in just 12 months – and for the first time, drugs that seem to slow the progression of disease.”

Maria Carrillo, the chief science officer of the Alzheimer’s Association in the US, also hailed donanemab’s trial results. “These are the strongest phase 3 data for an Alzheimer’s treatment to date,” she said.

Alzheimer’s is the most common cause of dementia, one of the world’s biggest health threats. The number of people living with dementia globally is forecast to nearly triple to 153 million by 2050, and experts have said it presents a rapidly growing threat to future health and social care systems in every community, country and continent.

In patients on donanemab, 47% showed no signs of the disease progressing after a year, according to a statement issued by Lilly . That compared to 29% on a placebo.

The drug resulted in 40% less decline in the ability to perform activities of daily living, the company said. Patients on donanemab also experienced a 39% lower risk of progressing to the next stage of disease compared to those on a placebo.

However, the company also reported side-effects.

Brain swelling occurred in 24% of those on donanemab, with 6.1% experiencing symptoms, Lilly said. Brain bleeding occurred in 31.4% of the donanemab group and 13.6% of the placebo group.

Lilly also said the incidence of serious brain swelling in the donanemab study was 1.6%, including two deaths attributed to the condition and a third death after an incident of serious brain swelling.

“The treatment effect is modest, as is the case for many first-generation drugs, and there are risks of serious side-effects that need to be fully scrutinised before donenemab can be marketed and used,” said Dr Susan Kohlhaas, the executive director of research and partnerships at Alzheimer’s Research UK.

But she said the results were still “incredibly encouraging” and represented “another hugely significant moment for dementia research”.

“We’re now on the cusp of a first generation of treatments for Alzheimer’s disease, something that many thought impossible only a decade ago,” she added. “People should be really encouraged by this news, which is yet more proof that research can take us ever closer towards a cure.”

Lilly said it planned to apply for approval from the US Food and Drug Administration next month, and with regulators in other countries shortly thereafter.

“At face value, these data look positive, but we need to see the full dataset,” said Dr Liz Coulthard, an associate professor in dementia neurology at the University of Bristol.

“Donanemab seems to help people with early Alzheimer’s retain cognitive function for longer – and this effect looks to be clinically meaningful. Donanemab might help people live well with Alzheimer’s for longer. If approved alongside lecanemab, this potentially brings a choice of treatments for patients.”

- Alzheimer's

- Pharmaceuticals industry

Most viewed

- Alzheimer's disease & dementia

- Arthritis & Rheumatism

- Attention deficit disorders

- Autism spectrum disorders

- Biomedical technology

- Diseases, Conditions, Syndromes

- Endocrinology & Metabolism

- Gastroenterology

- Gerontology & Geriatrics

- Health informatics

- Inflammatory disorders

- Medical economics

- Medical research

- Medications

- Neuroscience

- Obstetrics & gynaecology

- Oncology & Cancer

- Ophthalmology

- Overweight & Obesity

- Parkinson's & Movement disorders

- Psychology & Psychiatry

- Radiology & Imaging

- Sleep disorders

- Sports medicine & Kinesiology

- Vaccination

- Breast cancer

- Cardiovascular disease

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Colon cancer

- Coronary artery disease

- Heart attack

- Heart disease

- High blood pressure

- Kidney disease

- Lung cancer

- Multiple sclerosis

- Myocardial infarction

- Ovarian cancer

- Post traumatic stress disorder

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Schizophrenia

- Skin cancer

- Type 2 diabetes

- Full List »

share this!

September 5, 2023

This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies . Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

Scientists discover new cause of Alzheimer's, vascular dementia

by Erik Robinson, Oregon Health & Science University

Researchers have discovered a new avenue of cell death in Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia.

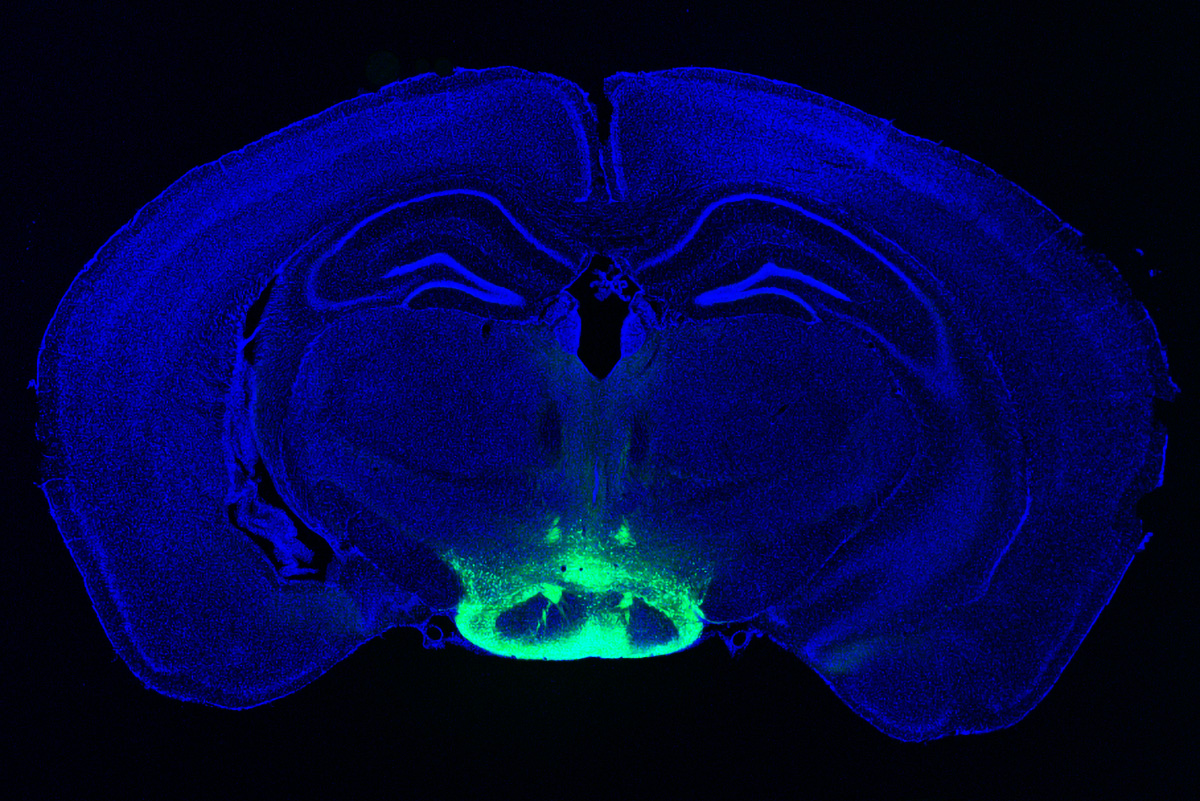

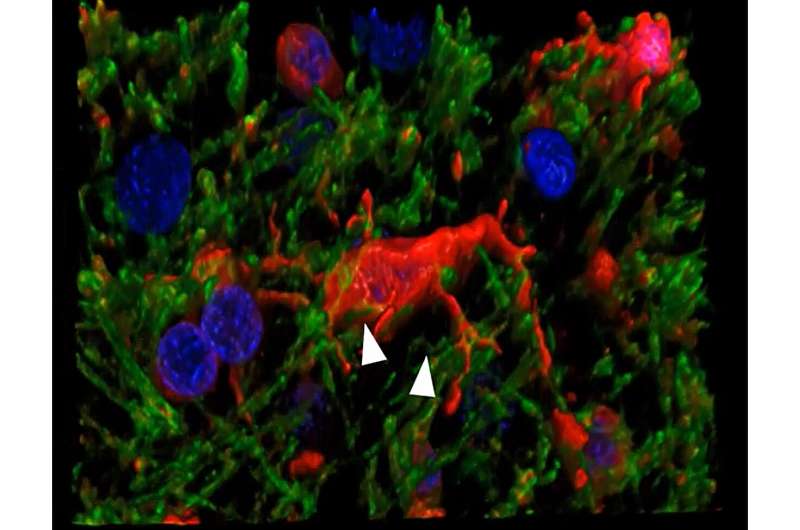

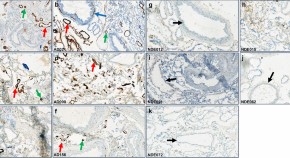

A new study, led by scientists at Oregon Health & Science University and published in the journal Annals of Neurology , reveals for the first time that a form of cell death known as ferroptosis—caused by a buildup of iron in cells—destroys microglia cells, a type of cell involved in the brain 's immune response, in cases of Alzheimer's and vascular dementia .

The researchers conducted the study examining post-mortem human brain tissue of patients with dementia.

"This is a major finding," said senior author Stephen Back, M.D., Ph.D., a neuroscientist and professor of pediatrics in the OHSU School of Medicine.

Back has long studied myelin, the insulation-like protective sheath covering nerve fibers in the brain, including delays in forming myelin in premature infants. The new research extends that line of work by uncovering a cascading form of neurodegeneration triggered by deterioration of myelin. They made the discovery using a novel technique developed by the study's lead author Philip Adeniyi, Ph.D., a postdoctoral researcher in Back's laboratory.

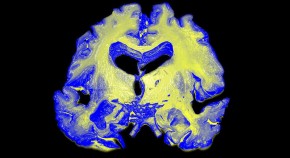

The researchers discovered that microglia degenerates in the white matter of the brain of patients with Alzheimer's and vascular dementia.

Microglia are resident cells in the brain normally involved in clearing cellular debris as part of the body's immune system. When myelin is damaged, microglia swarm in to clear the debris. In the new study, researchers found that microglia themselves are destroyed by the act of clearing iron-rich myelin—a form of cell death known as ferroptosis.

Given the intense scientific focus on the underlying cause of dementia in older adults , Back called it amazing that researchers hadn't made the connection to ferroptosis until now.

"We've missed a major form of cell death in Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia," Back said. "We hadn't been giving much attention to microglia as vulnerable cells, and white matter injury in the brain has received relatively little attention."

Co-author Kiera Degener-O'Brien, M.D., initially discovered the degeneration of microglia in tissue samples, Back said. Adeniyi subsequently developed a novel immunofluorescence technique to determine that iron toxicity was causing microglial degeneration in the brain. This was likely a result of the fact that the fragments of myelin are themselves rich in iron, Back said.

In effect, the immune cells were dying in the line of duty.

"Everyone knows that microglia are activated to mediate inflammation," Back said. "But no one knew that they were dying in such large numbers. It's just amazing that we missed this until now."