Religion and Politics: the Role of Religion in Politics Essay Example

Introduction, relationship between religion and politics, religious fundamentalism, works cited.

Religion is closely related to politics in a number of ways. In the traditional society, religious leaders were both temporal and civil leaders. In 1648, a treaty of Westphalia was signed, which separated politics from the Church. However, religion has always influenced policy making process and decision-making in government. In many parts of the world, religious leaders influence political leaders to come up with policies that are in line with the provisions of religious beliefs.

However, the main question is how religion influences politics. In the United States, there is a clause in the Bill of Rights referred to as the disestablishment clause, which provides that politics must be kept separate from politics. In established democracies, somebody with questionable religious record stands no chance of being elected. The populace believes that a religious leader would always be willing to listen to the wishes of the majority (Settimba 9).

A non-religious leader is believed to be indifferent to the sufferings of the majority in society. In other words, a non-religious leader would fulfill his or her own interests instead of serving those who elected him or her. During campaigns at state level in the United States, local leaders quote the Bible whenever they want to bring out a certain fact.

In human life, each group has a belief system that is established with the help of religious values. These beliefs influence the political standpoint of an individual in a political system. The media will always evaluate the life of a politician using certain religious principles.

These principles are derived from religious morals and beliefs. In this case, a candidate in an election is identified as a Christian or a Muslim. The religion of a political leader determines the number of votes he or she would gunner in an election. In the United States, politicians associate themselves with Christianity because a majority of voters are Christians.

In the Arab world, a political leader must associate himself with Islam because it is a dominant religion in the region. Furthermore, the religious sects must be stated clearly before a political leader is elected. In other countries, religion is the major variable in every electioneering year. It is believed that certain religious affiliations are related to cultural beliefs that affect the performance of leaders in any political system. Recently, the issue of religion emerged in the United States when Obama was said to be a Muslim.

Many people were much worried that Obama was a Muslim. Islam has always been associated with extremism meaning that Muslims are accused of using warped means to attain justice. It was feared that Obama could support Muslims once he became president. However, the president dispelled fears by declaring that he was indeed a Christian. This nearly cost him the presidency (Johnstone 64).

There is a popular belief among Christians that good leaders are usually sent by God. This is based on the Bible whereby many kings and prophets were sent by God to lead Israelites in the times of war and calamities. Political leaders have always presented themselves as leaders sent by God to accomplish certain missions.

Through this, they have been able to ascend to leadership positions. Whenever political leaders make speeches, they quote the Bible to show the electorate that they understand the Christian principles. The idea that political leaders must come up with policies favoring the poor is based on the teachings of the Bible. The Bible and the Koran teaches that people must always be assisted to achieve their potentials in society.

It is not the interest of the ruling class to help the poor. The main aim of the ruling class is to amass wealth and use the proletariat to ascend to power. Political parties that tend to favor the poor in their manifestos have always clinched political power. Social justice ideology is based on the teachings of the Bible because the poor must have equal access to resources including healthcare, education, and employment.

Religious fundamentalism was first used in the United States to refer to those individuals who opposed the principles of the mainstream church. Those who subscribed to the ideas of the Protestant Churches were perceived as religious fundamentalists. In other words, fundamentalism was interpreted to mean diverting from the mainstream faith.

However, what should be clear is that fundamentalists had pertinent issues with the mainstream church since the mainstream church never allowed competition. Religious fundamentalists observed that it was critical to follow the teachings of the Bible instead of subscribing to the interpretations provided by the religious leaders. Religious leaders interpreted the teachings in the Bible to suit their interests.

Many people were not happy with this behavior. The mainstream church interpreted the Bible in accordance to the new dynamics of the modern world. However, fundamentalists were never happy about this. They believed that it would be better to stick to the teachings of the Bible. In the modern society, fundamentalism is used loosely to mean diverting from the normal beliefs and principles of major religions (McGuire 76).

Fundamentalism is a relatively new term in the sociology of religion because it was first used in the 19 th century. The modern society is complex to understand because of the changes brought about globalization and technology. Therefore, fundamentalism in the modern society has a different meaning. Religion in the modern society serves a different purpose as compared to its role in the traditional society. Religion is an instrument that brings people together.

In this regard, it must be used to bring about understanding and unity. This implies that religious teachings are usually interpreted to simplify the complexities in life. Religious fundamentalists do not believe that anything has changed as far as religion is concerned. In this case, modern interpretations must not be accepted because they go against the traditional teachings of religion (Weber 22).

When other people embrace change in society, religious fundamentalists encourage conservatism. To them, religion is absolute meaning that it dictates everything in society. There is a controversy among scholars regarding the use of the term because fundamentalists are perceived as people who are not intelligent.

Others view them as uneducated individuals who believe religion is everything in society. Religious fundamentalists believe that some things should not be allowed to go on in society. For instance, they oppose science, abortion, feminism, the use of family planning drugs, and homosexuality.

Recently, the term has been associated with Islamic extremists who believe that justice should be sought through terrorism and violence. For Islamic fundamentalists, the main problem in the world is exploitation. The west has always exploited people in other parts of the world, including the Middle East. To them, the main issue is that the west has always neglected the presence of Arabs.

Johnstone, Ronald. Religion in Society: Sociology of Religion . Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2007. Print.

McGuire, Meredith. Religion: the Social Context . New York: Sage, 2002. Print.

Settimba, Henry (2009). Testing times: globalization and investing theology in East Africa . Milton Keynes: Author House, 2009. Print.

Weber, Max. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism . Los Angeles: Roxbury Company, 2002. Print.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, December 11). Religion and Politics: the Role of Religion in Politics Essay Example. https://ivypanda.com/essays/religion-and-politics/

"Religion and Politics: the Role of Religion in Politics Essay Example." IvyPanda , 11 Dec. 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/religion-and-politics/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'Religion and Politics: the Role of Religion in Politics Essay Example'. 11 December.

IvyPanda . 2018. "Religion and Politics: the Role of Religion in Politics Essay Example." December 11, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/religion-and-politics/.

1. IvyPanda . "Religion and Politics: the Role of Religion in Politics Essay Example." December 11, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/religion-and-politics/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Religion and Politics: the Role of Religion in Politics Essay Example." December 11, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/religion-and-politics/.

- Impact of the Religious Fundamentalism on Society

- Influence of Religion on Politics

- Impact of Religion on Politics

- Introduction to Canadian Public Administration: Solving the Current Issues and Improving the System Clockwork

- Violence is a Persuasive Force

- Monarchy in Canada

- What Makes Democracy Succeed or Fail?

- Success or Failure of Democracy

America Without God

As religious faith has declined, ideological intensity has risen. Will the quest for secular redemption through politics doom the American idea?

This article was published online on March 10, 2021.

T he United States had long been a holdout among Western democracies, uniquely and perhaps even suspiciously devout. From 1937 to 1998, church membership remained relatively constant, hovering at about 70 percent. Then something happened. Over the past two decades, that number has dropped to less than 50 percent, the sharpest recorded decline in American history. Meanwhile, the “nones”—atheists, agnostics, and those claiming no religion— have grown rapidly and today represent a quarter of the population.

But if secularists hoped that declining religiosity would make for more rational politics, drained of faith’s inflaming passions, they are likely disappointed. As Christianity’s hold, in particular, has weakened, ideological intensity and fragmentation have risen. American faith, it turns out, is as fervent as ever; it’s just that what was once religious belief has now been channeled into political belief. Political debates over what America is supposed to mean have taken on the character of theological disputations. This is what religion without religion looks like.

Not so long ago, I could comfort American audiences with a contrast: Whereas in the Middle East, politics is war by other means—and sometimes is literal war—politics in America was less existentially fraught. During the Arab Spring, in countries like Egypt and Tunisia, debates weren’t about health care or taxes—they were, with sometimes frightening intensity, about foundational questions: What does it mean to be a nation? What is the purpose of the state? What is the role of religion in public life? American politics in the Obama years had its moments of ferment—the Tea Party and tan suits—but was still relatively boring.

We didn’t realize how lucky we were. Since the end of the Obama era, debates over what it means to be American have become suffused with a fervor that would be unimaginable in debates over, say, Belgian-ness or the “meaning” of Sweden. It’s rare to hear someone accused of being un-Swedish or un-British—but un-American is a common slur, slung by both left and right against the other. Being called un-American is like being called “un-Christian” or “un-Islamic,” a charge akin to heresy.

From the October 2018 issue: The Constitution is threatened by tribalism

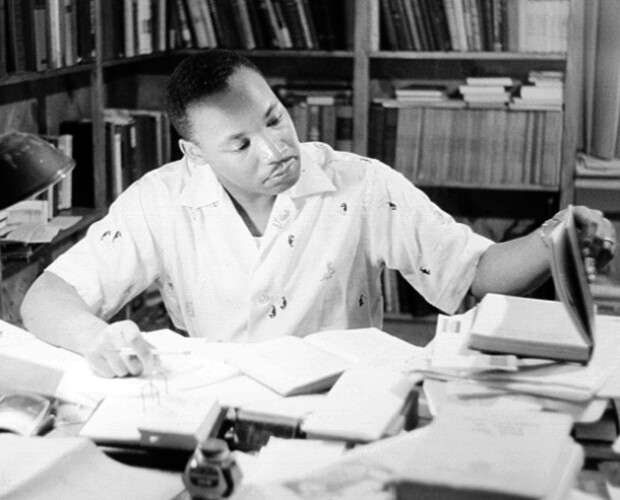

This is because America itself is “almost a religion,” as the Catholic philosopher Michael Novak once put it, particularly for immigrants who come to their new identity with the zeal of the converted. The American civic religion has its own founding myth, its prophets and processions, as well as its scripture—the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and The Federalist Papers . In his famous “I Have a Dream” speech, Martin Luther King Jr. wished that “one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed.” The very idea that a nation might have a creed—a word associated primarily with religion—illustrates the uniqueness of American identity as well as its predicament.

The notion that all deeply felt conviction is sublimated religion is not new. Abraham Kuyper, a theologian who served as the prime minister of the Netherlands at the dawn of the 20th century, when the nation was in the early throes of secularization, argued that all strongly held ideologies were effectively faith-based, and that no human being could survive long without some ultimate loyalty. If that loyalty didn’t derive from traditional religion, it would find expression through secular commitments, such as nationalism, socialism, or liberalism. The political theorist Samuel Goldman calls this “the law of the conservation of religion”: In any given society, there is a relatively constant and finite supply of religious conviction. What varies is how and where it is expressed.

Recommended Reading

How American Politics Went Insane

Americans Aren’t Practicing Democracy Anymore

The Most Important Divide in American Politics Isn’t Race

No longer explicitly rooted in white, Protestant dominance, understandings of the American creed have become richer and more diverse—but also more fractious. As the creed fragments, each side seeks to exert exclusivist claims over the other. Conservatives believe that they are faithful to the American idea and that liberals are betraying it—but liberals believe, with equal certitude, that they are faithful to the American idea and that conservatives are betraying it. Without the common ground produced by a shared external enemy, as America had during the Cold War and briefly after the September 11 attacks, mutual antipathy grows, and each side becomes less intelligible to the other. Too often, the most bitter divides are those within families.

No wonder the newly ascendant American ideologies, having to fill the vacuum where religion once was, are so divisive. They are meant to be divisive. On the left, the “woke” take religious notions such as original sin, atonement, ritual, and excommunication and repurpose them for secular ends. Adherents of wokeism see themselves as challenging the long-dominant narrative that emphasized the exceptionalism of the nation’s founding. Whereas religion sees the promised land as being above, in God’s kingdom, the utopian left sees it as being ahead , in the realization of a just society here on Earth. After Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg died in September, droves of mourners gathered outside the Supreme Court—some kneeling, some holding candles—as though they were at the Western Wall.

On the right, adherents of a Trump-centric ethno-nationalism still drape themselves in some of the trappings of organized religion, but the result is a movement that often looks like a tent revival stripped of Christian witness. Donald Trump’s boisterous rallies were more focused on blood and soil than on the son of God. Trump himself played both savior and martyr, and it is easy to marvel at the hold that a man so imperfect can have on his soldiers. Many on the right find solace in conspiracy cults, such as QAnon, that tell a religious story of earthly corruption redeemed by a godlike force.

From the June 2020 issue: Adrienne LaFrance on the prophecies of Q

Though the United States wasn’t founded as a Christian nation, Christianity was always intertwined with America’s self-definition. Without it, Americans—conservatives and liberals alike—no longer have a common culture upon which to fall back.

Unfortunately , the various strains of wokeism on the left and Trumpism on the right cannot truly fill the spiritual void—what the journalist Murtaza Hussain calls America’s “God-shaped hole.” Religion, in part, is about distancing yourself from the temporal world, with all its imperfection. At its best, religion confers relief by withholding final judgments until another time—perhaps until eternity. The new secular religions unleash dissatisfaction not toward the possibilities of divine grace or justice but toward one’s fellow citizens, who become embodiments of sin—“deplorables” or “enemies of the state.”

This is the danger in transforming mundane political debates into metaphysical questions. Political questions are not metaphysical; they are of this world and this world alone. “Some days are for dealing with your insurance documents or fighting in the mud with your political opponents,” the political philosopher Samuel Kimbriel recently told me, “but there are also days for solemnity, or fasting, or worship, or feasting—things that remind us that the world is bigger than itself.”

Absent some new religious awakening, what are we left with? One alternative to American intensity would be a world-weary European resignation. Violence has a way of taming passions, at least as long as it remains in active memory. In Europe, the terrors of the Second World War are not far away. But Americans must go back to the Civil War for violence of comparable scale—and for most Americans, the violence of the Civil War bolsters, rather than undermines, the national myth of perpetual progress. The war was redemptive—it led to a place of promise, a place where slavery could be abolished and the nation made whole again. This, at least, is the narrative that makes the myth possible to sustain.

For better and worse, the United States really is nearly one of a kind. France may be the only country other than the United States that believes itself to be based on a unifying ideology that is both unique and universal—and avowedly secular. The French concept of laïcité requires religious conservatives to privilege being French over their religious commitments when the two are at odds. With the rise of the far right and persistent tensions regarding Islam’s presence in public life, the meaning of laïcité has become more controversial. But most French people still hold firm to their country’s founding ideology: More than 80 percent favor banning religious displays in public, according to one recent poll.

In democracies without a pronounced ideological bent, which is most of them, nationhood must instead rely on a shared sense of being a distinct people, forged over centuries. It can be hard for outsiders and immigrants to embrace a national identity steeped in ethnicity and history when it was never theirs.

Take postwar Germany. Germanness is considered a mere fact—an accident of birth rather than an aspiration. And because shame over the Holocaust is considered a national virtue, the country has at once a strong national identity and a weak one. There is pride in not being proud. So what would it mean for, say, Muslim immigrants to love a German language and culture tied to a history that is not theirs—and indeed a history that many Germans themselves hope to leave behind?

An American who moves to Germany, lives there for years, and learns the language remains an American—an “expat.” If America is a civil religion, it would make sense that it stays with you, unless you renounce it. As Jeff Gedmin, the former head of the Aspen Institute in Berlin, described it to me: “You can eat strudel, speak fluent German, adapt to local culture, but many will still say of you Er hat einen deutschen Pass —‘He has a German passport.’ No one starts calling you German.” Many native-born Americans may live abroad for stretches, but few emigrate permanently. Immigrants to America tend to become American; emigrants to other countries from America tend to stay American.

The last time I came back to the United States after being abroad, the customs officer at Dulles airport, in Virginia, glanced at my passport, looked at me, and said, “Welcome home.” For my customs officer, it went without saying that the United States was my home.

In In the Light of What We Know , a novel by the British Bangladeshi author Zia Haider Rahman, the protagonist, an enigmatic and troubled British citizen named Zafar, is envious of the narrator, who is American. “If an immigration officer at Heathrow had ever said ‘Welcome home’ to me,” Zafar says, “I would have given my life for England, for my country, there and then. I could kill for an England like that.” The narrator reflects later that this was “a bitter plea”:

Embedded in his remark, there was a longing for being a part of something. The force of the statement came from the juxtaposition of two apparent extremes: what Zafar was prepared to sacrifice, on the one hand, and, on the other, what he would have sacrificed it for—the casual remark of an immigration official.

When Americans have expressed disgust with their country, they have tended to frame it as fulfillment of a patriotic duty rather than its negation. As James Baldwin, the rare American who did leave for good, put it: “I love America more than any other country in the world, and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.” Americans who dislike America seem to dislike leaving it even more (witness all those liberals not leaving the country every time a Republican wins the presidency, despite their promises to do so). And Americans who do leave still find a way, like Baldwin, to love it. This is the good news of America’s creedal nature, and may provide at least some hope for the future. But is love enough?

Conflicting narratives are more likely to coexist uneasily than to resolve themselves; the threat of disintegration will always lurk nearby.

On January 6, the threat became all too real when insurrectionary violence came to the Capitol. What was once in the realm of “dreampolitik ” now had physical force. What can “unity” possibly mean after that?

Can religiosity be effectively channeled into political belief without the structures of actual religion to temper and postpone judgment? There is little sign, so far, that it can. If matters of good and evil are not to be resolved by an omniscient God in the future, then Americans will judge and render punishment now. We are a nation of believers. If only Americans could begin believing in politics less fervently, realizing instead that life is elsewhere. But this would come at a cost—because to believe in politics also means believing we can, and probably should, be better.

In History Has Begun , the author, Bruno Maçães—Portugal’s former Europe minister—marvels that “perhaps alone among all contemporary civilizations, America regards reality as an enemy to be defeated.” This can obviously be a bad thing (consider our ineffectual fight against the coronavirus), but it can also be an engine of rejuvenation and creativity; it may not always be a good idea to accept the world as it is. Fantasy, like belief, is something that humans desire and need. A distinctive American innovation is to insist on believing even as our fantasies and dreams drift further out of reach.

This may mean that the United States will remain unique, torn between this world and the alternative worlds that secular and religious Americans alike seem to long for. If America is a creed, then as long as enough citizens say they believe, the civic faith can survive. Like all other faiths, America’s will continue to fragment and divide. Still, the American creed remains worth believing in, and that may be enough. If it isn’t, then the only hope might be to get down on our knees and pray.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Religion and Political Theory

When the well-known political theorist Leo Strauss introduced the topic of politics and religion in his reflections, he presented it as a problem —the “theologico-political problem” he called it (Strauss 1997). [ 1 ] The problem, says Strauss, is primarily one about authority: Is political authority to be grounded in the claims of revelation or reason, Jerusalem or Athens? In so characterizing the problem, Strauss was tapping into currents of thought deep in the history of political reflection in the west, ones about the nature, extent, and justification of political authority. Do monarchies owe their authority to divine right? Has God delegated to secular rulers such as kings and emperors the authority to wage war in order to achieve religious aims: the conversion of the infidel or the repulsion of unjust attacks on the true faith? Do secular rulers have the authority to suppress heretics? What authority does the state retain when its principles conflict with God's? Is the authority of the natural law ultimately grounded in divine law? These and other questions animated much of the discussion among medieval and modern philosophers alike.

With the emergence of liberal democracy in the modern west, however, the types of questions that philosophers asked about the interrelation between religion and political authority began to shift, in large measure because the following three-fold dynamic was at work. In the first place, divine-authorization accounts of political authority had lost the day to consent-based approaches. Political authority in a liberal democracy, most prominent defenders of liberal democracy claimed, is grounded in the consent of the people to be ruled rather than in God's act of authorization. Second, the effects of the Protestant Reformation had made themselves felt acutely, as the broadly homogeneous religious character of Western Europe disintegrated into competing religious communities. The population of Western Europe and the United States were now not only considerably more religiously diverse, but also deeply wary of the sort of bloodshed occasioned by the so-called religious wars. And, finally, secularization had begun to take hold. Both the effects of religious diversity and prominent attacks on the legitimacy of religious belief ensured that one could no longer assume in political discussion that one's fellow citizens were religious, let alone members of one's own religious tradition.

For citizens of contemporary liberal democracies, this three-fold dynamic has yielded a curious situation. On the one hand, most take it for granted that the authority of the state is located in the people, that the people are religiously diverse, and that important segments of people doubt the rationality of religious belief and practice of any sort. On the other hand, contrary to the predictions of many advocates of secularization theory, such as Karl Marx, Max Weber, and (at one time) Peter Berger, this mix of democracy, religious diversity, and religious criticism has not resulted in the disappearance or privatization of religion. Religion, especially in liberal democracies such as the United States, is alive and well, shaping political culture in numerous ways. Consequently, there very much remains a theologico-political problem. The problem, moreover, still concerns political authority, though now reframed by the transition to liberal democracy. If recent reflection on the issue is any guide, the most pressing problem to address is this: Given that state-authorized coercion needs to be justified, and that the justification of state coercion requires the consent of the people, what role may religious reasons play in justifying state coercion? More specifically, in a religiously pluralistic context such as one finds in contemporary liberal democracies, are religious reasons sufficient to justify a coercive law for which reasonable agents cannot find an adequate secular rationale?

This entry considers the most important answers to these questions offered by recent philosophers, political theorists, and theologians. We present these answers as part of a lively three-way discussion between advocates of what we call the standard view, their liberal critics, and proponents of the so-called New Traditionalism. Briefly stated, advocates of the standard view argue that in contemporary liberal democracies, significant restraints must be put on the political role of religious reasons. Their liberal critics deny this, or at least deny that good reasons have been given to believe this. New Traditionalists, by contrast, turn their back on both the standard view and its liberal critics, arguing that religious orthodoxy and liberal democracy are fundamentally incompatible. To have a grip on this three-way debate, we suggest, is to understand that dimension of the theologico-political problem that most animates philosophical reflection in liberal democracies on the relation between religion and politics.

1. The Standard View

2.1 core components of the doctrine of religious restraint, 3.1 the argument from religious warfare, 3.2 the argument from divisiveness, 3.3 the argument from respect, 4. liberal critics of the doctrine of religious restraint, 5. the primary concern regarding the doctrine of religious restraint.

- 7. A Convergence Alternative

8.1 The Declinist Narrative of the New Traditionalism

8.2 two concerns about the narrative, other internet resources, related entries.

The standard view among political theorists, such as Robert Audi, Jürgen Habermas, Charles Larmore, Steven Macedo, Martha Nussbaum, and John Rawls is that religious reasons can play only a limited role in justifying coercive laws, as coercive laws that require a religious rationale lack moral legitimacy. [ 2 ] If the standard view is correct, there is an important asymmetry between religious and secular reasons in the following respect: some secular reasons can themselves justify state coercion but no religious reason can. This asymmetry between the justificatory potential of religious and secular reasons, it is further claimed, should shape the political practice of religious believers. According to advocates of the standard view, citizens should not support coercive laws for which they believe there is no plausible secular rationale, although they may support coercive laws for which they believe there is only a secular rationale. (Note that not just any secular rationale counts.) We can refer to this injunction to exercise restraint as The Doctrine of Religious Restraint (or the DRR, for short). [ 3 ] This abstract characterization of the DRR will require some refinements, which we'll provide in sections 2 and 3. For the time being, however, we can get a better feel for the character of the DRR by considering the following case.

2. The Doctrine of Religious Restraint

Rick is a politically engaged citizen who intends to vote in a referendum on a measure that would criminalize homosexual relations. As he evaluates the relevant considerations, he concludes that the only persuasive rationale for that measure includes as a crucial premise the claim that homosexual relations are contrary to a God-established natural order. Although he finds that rationale compelling, he realizes that many others do not. But because he takes himself to have a general moral obligation to make those political decisions that, as best he can tell, are both just and good, he decides to vote in favor of criminalization. Moreover, he tries to persuade his compatriots to vote with him. In so doing, he offers relevantly different arguments to different audiences. He tries to convince like-minded citizens by appealing to the theistic natural law argument that he finds persuasive. But he realizes that many of his fellow citizens are unpersuaded by the natural law argument that convinces him. So he articulates a variety of other arguments—some secular, some religious—that he hopes will leverage those who don't share his natural law theism into supporting his position. He does so even though he doubts that any of those leveraging arguments are cogent, realizes that many of those to whom he addresses them will have comparable doubts about their cogency, and so believes that many coerced by the law he supports have no good reason, from their perspective, to affirm that law.

Advocates of the standard view will be troubled by Rick's behavior. The relevantly troubling feature of Rick's behavior is not primarily his decision to support this particular policy. Rather, it is his decision to support a policy that he believes others have no good reason, from their perspective, to endorse. After all, Rick votes to enact a law that authorizes state coercion even though he believes that the only plausible rationale for that decision includes religious claims that many of his compatriots find utterly unpersuasive. In so doing, Rick violates a normative constraint at the heart of the standard view, viz., that citizens in a pluralistic liberal democracy ought to refrain from using their political influence to authorize coercive laws that, to the best of their knowledge, can be justified only on religious grounds and so lack a plausible secular rationale. [ 4 ] Or, otherwise put, Rick violates the DRR. For the DRR tells us that, if a citizen is trying to determine whether or not she should support some coercive law, and if she believes that there is no plausible secular rationale for that law, then she may not support it.

The DRR is a negative constraint; it identifies a kind of reason that cannot itself justify a coercive law and so a kind of reason on which citizens may not exclusively rely when supporting a coercive law. But this negative constraint is typically conjoined with a permission: although citizens may not support coercive laws for which they believe themselves to have only a religious rationale, they may support coercive laws for which they believe there is only a plausible secular rationale. As we'll see in a moment, advocates of the DRR furnish reasons to believe that religious and secular reasons have this asymmetrical justificatory role.

The standard view has often been misunderstood, typically by associating the DRR with claims its advocates are free to deny. It will therefore be helpful to dissociate the DRR from various common misunderstandings.

First, the DRR is a moral constraint, one that applies to people in virtue of the fact that they are citizens of a liberal democracy. As such, it need not be encoded into law, enforced by state coercion or social stigma, promoted in state educational institutions, or in any other way policed by the powers that be. Of course, advocates of restraint are free to argue that the state should police violations of the DRR (see Habermas 2006, 10). [ 5 ] Perhaps some liberal democracies do police something like the DRR. But advocates of the standard view needn't endorse restrictions of this sort. [ 6 ]

Second, the DRR does not require a thorough-going privatization of religious commitment. Indeed, the DRR permits religious considerations to play a rather prominent role in a citizen's political practice: citizens are permitted to vote for their favored coercive policies on exclusively religious grounds as well as to advocate publicly for those policies on religious grounds. What the DRR does require of citizens is that they reasonably believe that they have some plausible secular rationale for each of the coercive laws that they support, which they are prepared to offer in political discussion. In this respect, the present construal of the DRR is weaker than comparable proposals, such as that developed by Robert Audi, which requires that each citizen have and be motivated by some evidentially adequate secular rationale for each of the coercive laws he or she supports (see Audi 1997, 138 and Rawls 1997, 784ff).

Third, the DRR places few restrictions on the content of the secular reasons to which citizens can appeal when supporting coercive laws. Although the required secular reasons must be “plausible” (more on this in a moment), they may make essential reference to what Rawls calls “comprehensive conceptions of the good,” such as Platonism, Kantianism, or utilitarianism. [ 7 ] Accordingly, the standard view does not commit itself to a position according to which secular reasons must be included or otherwise grounded in a neutral source—a set of principles regarding justice and the common good such that everybody has good reason, apart from his own or any other religious or philosophical perspective, to find acceptable. Somewhat more specifically, advocates of the standard view needn't claim that secular reasons must be found in what Rawls calls “public reason,” which (roughly speaking) is a fund of shared principles about justice and the common good constructed from the shared political culture of a liberal democracy. That having been said, it is worth stressing that some prominent advocates of the standard view adopt a broadly Rawlsian account of the DRR, according to which coercive laws must be justified by appeal to public reason (see Gutmann and Thompson 1996, Larmore 1987, Macedo 1990, and Nussbaum 2008). We shall have more to say about this view in section 6.

Fourth, the DRR itself has no determinate policy implications; it is a constraint not on legislation itself, but on the configuration of reasons to which agents may appeal when supporting coercive legislation. So, for example, it forbids Rick to support the criminalization of homosexuality when he believes that there are no plausible secular reasons to criminalize it. As such, the moral propriety of the DRR has nothing directly to do with its usefulness in furthering, or discouraging, particular policy aims.

The DRR, then, is a norm that is supposed to provide guidance for how citizens of a liberal democracy should conduct themselves when deliberating about or deciding on the implementation of coercive laws. For our purposes, it will be helpful to work with a canonical formulation of it. Let us, then, formulate the DRR as follows:

The DRR : a citizen of a liberal democracy may support the implementation of a coercive law L just in case he reasonably believes himself to have a plausible secular justification for L, which he is prepared to offer in political discussion.

About this formulation of the DRR, let us make two points. First, in what follows, we will remain largely noncommittal about what the qualifier “plausible” means, as advocates of the standard view understand it in different ways. For present purposes, we will simply assume that a plausible rationale is one that epistemically and morally competent peers will take seriously as a basis for supporting a coercive law. Second, according to this formulation of the DRR, a citizen can comply with the DRR even if he himself is not persuaded to support a coercive law for any secular reason. What matters is that he believes that he has and can offer a secular rationale that his secular cohorts can take seriously.

Suppose, then, we have an adequate working conception of the DRR. The question naturally arises: Why do advocates of the standard view maintain that we should conform to the DRR? For several reasons, most prominent of which are the following three arguments. Of course, there are many more arguments for the DRR than we can address here. See, for example, Andrew Lister's appeal to the value of political community (2013).

3. Three Arguments for the Doctrine of Religious Restraint

Advocates of the standard view sometimes commend the DRR on the grounds that conforming to it will help prevent religious warfare and civil strife. According to Robert Audi, for example, “if religious considerations are not appropriately balanced with secular ones in matters of coercion, there is a special problem: a clash of Gods vying for social control. Such uncompromising absolutes easily lead to destruction and death” (Audi 2000, 103). The concern expressed here, presumably, is this: for all we reasonably believe, citizens who are willing to coerce their compatriots for religious reasons will use their political power to advance their sectarian agenda—using the power of the state to persecute heretics, impose orthodoxy, and enact stringent morals laws. In so doing, these citizens will thereby provoke determined resistance and civil conflict. Such a state of affairs, however, threatens the very viability of a liberal democracy and, so, should be avoided at nearly all costs. Accordingly, religious believers should exercise restraint when deliberating about the implementation of coercive laws. Exercising restraint, however, is best accomplished by adhering to the DRR.

According to the liberal critics of the standard view, there are several problems with this argument. First, the liberal critics contend, while there may have been a genuine threat of confessional warfare in 17 th century Western Europe, there is little reason to believe that there is any such threat in stable liberal democracies such as the United States. Why not? Because confessional conflict, the liberal critics continue, is typically rooted in egregious violations of the right to religious freedom, when, for example, people are jailed, tortured, or otherwise abused because of their religious commitments. John Locke puts the point thus:

it is not the diversity of Opinions (which cannot be avoided) but the refusal of Toleration to those that are of different Opinions (which might have been granted) that has produced all the Bustles and Wars, that have been in the Christian World, upon account of Religion. (Locke 1983, 155)

If Locke is correct, then what we need to prevent confessional conflict is not compliance with a norm such as the DRR, but firm commitment to the right to religious freedom. A stable liberal democracy such as the United States is, however, fully committed to protecting the right to religious freedom—and will be for the foreseeable future. True enough, there are passionately felt disagreements about how to interpret the right to religious freedom: witness recent conflicts as to whether or not the right to religious freedom should be understood to include the right of religious objectors to be exempted from generally justified state policies (See Koppelman 2013; Leiter 2012). But it is difficult to see, the liberal critics claim, that there is a realistic prospect of these disagreements devolving into violent civil conflict.

Second, even if there were a realistic prospect of religious conflict, liberal critics claim that it is unclear that adhering to the DRR would lower the probability that such a conflict would occur. After all, the trigger for religious war—typically, the violation of the right to religious freedom—is not always, or even typically, justified by exclusively religious considerations. As historian Michael Burleigh has argued, secularists have a long history of hostility to the right to religious freedom and, presumably, that hostility isn't at all grounded in religious considerations (Burleigh 2007, 135 and, more generally, Burleigh 2005).

Third, the liberal critics maintain, when religious believers have employed coercive power to violate the right to religious freedom, they themselves rarely have done so in a way that violates the DRR. Typically, when such rights have been violated, the justifications offered, even by religious believers, appeal to alleged requirements for social order, such as the need for uniformity of belief on basic normative issues. One theological apologist for religious repression, for example, writes this: “The king punishes heretics as enemies, as extremely wicked rebels, who endanger the peace of the kingdom, which cannot be maintained without the unity of the faith. That is why they are burnt in Spain” (quoted in Rivera, 1992, 50). Ordinarily, the kind of religious persecution that engenders religious conflict is legitimated by appeal to secular reasons of the sort mandated by the DRR. (This is the case even when religious actors are the ones who appeal to those secular reasons.)

Finally, liberal critics point out that some religious believers affirm the right to religious freedom on religious grounds; they take themselves to have powerful religious reason to affirm the right of each person to worship as she freely chooses, absent state coercion. So, for example, the 4 th century Nestorian Mar Aba: “I am a Christian. I preach my faith and want every man to join it. But I want him to join it of his own free will. I use force on no man” (quoted in Moffett 1986, 216). [ 8 ] A believer such as Mar Aba might be willing to violate the DRR; however, his violation would, according to the liberal critics, help not to cause religious war but to impede it. For Mar Aba's 'sectarian rationale' supports not the violation of religious freedom but its protection.

If the liberal critics are correct, one of the problems with the argument from warfare is that there is no realistic prospect of religious warfare breaking out in a stable liberal democracy such as the United States. Still, there may be other evils that are more likely to occur under current conditions, which compliance with the DRR might help to prevent. For example, it is plausible to suppose that the enactment of a coercive law that cannot be justified except on religious grounds would engender much anger and frustration on the part of those coerced: “when legislation is expressly based on religious arguments, the legislation takes on a religious character, to the frustration of those who don't share the relevant faith and who therefore lack access to the normative predicate behind the law” (Greene 1993, 1060). This in turn breeds division between citizens—anger and distrust between citizens who have to find some amicable way to make collective decisions about common matters. This counts in favor of the DRR precisely because compliance with the DRR diminishes the likelihood of our suffering from such bad consequences.

To this argument, liberal critics offer a three-part reply. First, suppose it is true that the implementation of coercive laws that can be justified only on religious grounds often causes frustration and anger among both secular and religious citizens. The liberal critics maintain that there is reason to believe that compliance with the DRR would also engender frustration and anger among other religious and secular citizens. To this end, they point to the fact that many religious believers believe that conforming to the DRR would compromise their loyalty to God: if they were prohibited from supporting coercive laws for which they take there to be strong but exclusively religious reasons to support, they would naturally take themselves to be prohibited from obeying God. But for many religious believers this is distressing; they take themselves to have overriding moral and religious obligations to obey God. Similarly, some secular citizens will likely be frustrated by the requirement that the DRR places on religious citizens. According to these secular citizens, all citizens have the right to make political decisions as their conscience dictates. And, on some occasions, these secular citizens hold that exercising that right will lead religious citizens to violate the DRR. [ 9 ]

If this is correct, for the argument from divisiveness to succeed, it would have to provide reason to believe that the level of frustration and anger that would be produced by violating the DRR would be greater than that of conforming to the DRR. But, the liberal critics claim, it is doubtful that we have any such reason: in a very religious society such as the United States, it might be the case that restrictions on the political practice of religious believers engenders at least as much frustration as the alternative.

Second, the liberal critics argue, there is reason to believe that conformance to the DRR would only marginally alleviate the frustration that some citizens feel when confronted with religious reasons in public political debate. The DRR, after all, does not forbid citizens from supporting coercive laws on religious grounds, nor does it forbid citizens to articulate religious arguments in public. Furthermore, complying with the DRR does not prevent religious citizens from advocating their favored laws in bigoted, inflammatory, or obnoxious manners; it has nothing to say about political decorum. So, for example, because the DRR doesn't forbid citizens from helping themselves to inflammatory or demeaning rhetoric in political argument, the anger and resentment engendered by such rhetoric does not constitute evidence for (or against) the DRR.

Third, the liberal critics contend that because most of the laws that have a chance of enactment in a society as pluralistic as the United States will have both religious and secular grounds, it will almost never be the case that any of the actual frustration caused by the public presence of religion supports the DRR. Given that the DRR requires not a complete but only a limited privatization of religious belief, very little of the frustration and anger apparently engendered by the public presence of religion counts in favor of the DRR. To which it is worth adding the following point: advocates of the standard view could, with Rorty (1995), adopt a more demanding conception of the DRR that requires the complete privatization of religious belief. But, as many advocates of the standard view itself maintain, it is doubtful that this move improves the argument's prospects. The complete privatization of religion is much more objectionable to religious citizens and, thus, more likely to create social foment. (Rorty, it should be noted, softened his approach on this issue. See Rorty 2003).

There are no doubt other factors that need to be taken into consideration in the calculation required to formulate the argument from divisiveness. But, the liberal critics maintain, it is unclear how those disparate factors would add up. In particular, if the liberal critics are correct, it is not clear whether requiring citizens to obey the DRR would result in less overall frustration, anger, and division than would not requiring them to do so. The issues at stake are empirical in character and the relevant empirical facts are not known.

The third and most prominent argument for the DRR is the argument from respect. Here we focus on only one formulation of the argument, which has affinities with a version of the argument offered by Charles Larmore (see Larmore 1987). [ 10 ]

The argument from respect runs as such:

- Each citizen deserves to be respected as a person.

- If each citizen deserves to be respected as a person, then there is a powerful prima facie presumption against the permissibility of state coercion. (On this basic claim, See Gaus, 2010, Gaus and Vallier, 2009.)

- So, there is a powerful prima facie presumption against the permissibility of state coercion.

- If the presumption against state coercion is to be overcome (as it sometimes must be), then state coercion must be justified to those who are coerced.

- If state coercion must be justified to those who are coerced, then any coercive law that lacks a plausible secular rationale is morally illegitimate (as there will be many to whom such coercion cannot be justified).

- If any coercive law that lacks a plausible secular rationale is morally illegitimate, then a citizen ought not to support any law that he believes to have only a religious rationale.

However, on the assumption that the antecedent to premise (4) is true—that there are cases in which the state must coerce—it follows (given a few other assumptions) that:

- The DRR is true.

That is, the DRR follows from a constraint on what makes for the moral legitimacy of state coercion—viz., that a morally legitimate law cannot be such that there are those to whom it cannot be justified—and from the claim that citizens should not support any law that they realize lacks moral legitimacy.

The argument from respect has received its fair share of criticism from liberal critics. Perhaps the most troubling of these criticisms is that the argument undermines the legitimacy of basic liberal commitments. To appreciate the thrust of this objection, focus for a moment on the notion being a coercive law that is justified to an agent , to which the argument appeals. How should we understand this concept? One natural suggestion is this:

A coercive law is justified to an agent only if he is reasonable and has sufficient reasons from his own perspective to support it.

Now consider a coercive law that protects fundamental liberal commitments, such as the right to exercise religious freedom. Is this law justified to each citizen of a liberal democracy? Liberal critics answer: no. For there appear to be reasonable citizens who have no good reason from their own perspective to affirm it. Consider, for example, a figure such as the Islamic intellectual Sayyid Qutb. While in prison, Qutb wrote an intelligent, informed, and morally serious commentary on the Koran in which he laid the ills of modern society at the feet of Christianity and liberal democracy. [ 11 ] The only way to extricate ourselves from the problems spawned by liberal democracy, Qutb argued, is to implement shariah or Islamic legal code, which implies that the state should not protect a robust right to religious freedom. In short, Qutb articulates what is, from his point of view, a compelling theological rationale against any law that authorizes the state to protect a robust right to religious freedom. If respect for persons requires that each coercive law be justified to those reasonable persons subject to that law, and if a person such as Qutb were a citizen of a liberal democracy, then the argument from respect implies that laws that protect the right to religious freedom are morally illegitimate, as they lack moral justification—at least for agents such as Qutb. [ 12 ] And for a defender of the standard view, this is certainly an unwelcome result.

This kind of case leads liberal critics of the standard view to deny the fourth premise of the argument from respect. If they are correct, it is not the case that coercive laws must be justified to those who must obey them (in the sense of justified to introduced earlier). Although having a persuasive justification would certainly be desirable and a significant moral achievement, the liberal critics maintain that the moral legitimacy of a law is not a function of whether it can be justified to all citizens—not even to all reasonable citizens. Some citizens are simply not in a strong epistemic position to recognize that certain coercive laws are morally legitimate. In such cases, liberal critics claim that we should do what we can to try to convince these citizens that they have been misled. And we should certainly do what we can to accommodate their concerns in ways that are consistent with basic liberal commitments (see Swaine 2006). At the end of the day, though, we may have no moral option but to coerce reasonable and epistemically competent peers whom we recognize have no reason from their perspective to recognize the legitimacy of the laws to which they are subject. However, if a coercive law can be morally legitimate even though some citizens are not in a strong position to recognize that it is, then (in principle) a coercive law can be justified even if it requires a religious rationale. After all, if religious reasons can be adequate (a possibility that advocates of the standard view do not typically deny), then they are just the sort of reason that can be adequate without being recognized as such even by our morally serious and epistemically competent peers.

It should be conceded, however, that this objection to the argument from respect relies on a particular understanding of what it is for a coercive law to be justified to an agent. Is there another account of this concept that would aid the advocates of the standard view? Perhaps. Nearly all theorists have argued that a coercive law's being justified to an agent does not require that that agent actually have what he regards as an adequate reason to support it (see Gaus 1996, Audi 1997, and Vallier 2014). “The question is not what people do endorse but what people have reason to endorse” (Gaus 2010, 23). Better to understand the concept being a coercive law that is justified to an agent along the following lines:

A coercive law is justified to an agent only if, were he reasonable and adequately informed, then he would have a sufficient reason from his own perspective to support it.

Given this weaker, counterfactual construal of what makes for morally permissible coercion, the argument from respect needn't undermine the legitimacy of the state's using coercion to protect basic liberal commitments. For we can always construe those counterfactual conditions in such a way that those who in fact reject basic liberal commitments would affirm them if they were more reasonable and better informed. In that case, using coercion to ensure that they comply with basic liberal commitments would not be to disrespect them. If this is correct, the prospect of there being figures such as Qutb, who reject the right to religious freedom, need not undermine the legitimacy of the state's coercive enforcement of that basic liberal commitment.

Liberal critics find this response unsatisfactory. After all, if this alternative construal of the argument is to succeed, it must be the case not only that:

Were an agent such as Qutb reasonable and adequately informed, he would have sufficient reason from his own perspective to support coercive laws that protect the right to religious liberty;

Every coercive law that protects basic liberal commitments is such that adequately informed and reasonable secular citizens would have a sufficient secular reason to support it.

These two claims, however, are highly controversial. Let us consider the first. Were we to ask Qutb whether he would have reasons to support laws that protect a robust right to religious freedom if he were adequately informed and reasonable, surely he would say: no. Moreover, he would claim that his compatriots would reject the liberal protection of such a right if they were adequately informed about the divine authorship of the Quran and the proper rules of its interpretation. While Qutb's say-so doesn't settle the issue of who would believe what in improved conditions, liberal critics maintain that his response indicates just how complicated the issue under consideration is. Among other things, to establish that Qutb is wrong it seems that one would have to deny the truth of various theological claims on which Qutb relies when he determines that he would reject the right to religious freedom were he adequately informed and reasonable. That would require advocates of the standard view to take a stand on contested religious issues. However, liberal critics point out that defenders of the standard view have been wary of explicitly denying the truth of religious claims, especially those found within the major theistic religions.

Turn now to the second claim. Some liberal critics of the standard view, such as Nicholas Wolterstorff, maintain that at the heart of liberal democracy is the claim that some coercive laws function to protect inherent human rights. Wolterstorff further argues that attempts to ground these rights in merely secular considerations fail. Only by appeal to explicitly theistic assumptions, Wolterstorff argues, can we locate an adequate justification for the ascription of these rights (see Wolterstorff 2008, Pt. III as well as Perry 2003). What would a reasonable and adequately informed secular citizen make of Wolterstorff's arguments? Would he endorse them?

It's difficult to say. Liberal critics maintain that we are simply not in good epistemic position to judge the reasons an agent would have to support laws that protect basic liberal commitments were he better informed and more reasonable. More exactly, liberal critics maintain that we are not in a good epistemic position to determine whether a secular agent who is reasonable and better informed would endorse or reject the type of theistic commitments that philosophers such as Wolterstorff claim justify the ascription of natural human rights. The problem is that we don't really have any idea how radically a person would change his views were he to occupy these conditions. The main, and still unresolved, question for this version of the standard view, then, is whether there is some coherent and non-arbitrary construal of the relevant counterfactual conditions that is strong enough to prohibit exclusive reliance on religious reasons but weak enough to allow for the justification of basic liberal commitments. (See Vallier 2014 for the most recent and sophisticated attempt to specify those counterfactual conditions.)

In the last section, we considered three arguments for the DRR and responses to them offered by the liberal critics. In the course of our discussion, we began to see elements of the view that liberal critics of the standard view—critics such as Christopher Eberle, Philip Quinn, Jeffrey Stout, and Nicholas Wolterstorff—endorse. To get a better feel for why these theorists reject the DRR, it will be helpful to step back for a moment to consider some important features of their view.

Earlier we indicated that liberal critics of the standard view offer detailed replies to both the Argument from Religious Warfare and the Argument from Divisiveness. Still, friends of the standard view may worry that there is something deeply problematic about these replies. For by allowing citizens to support coercive laws on purely religious grounds, they permit majorities to impose their religious views on others and restrict the liberties of their fellow citizens. But it is important to see that no liberal critic of the standard position adopts an “anything goes” policy toward the justification of state coercion. Citizens, according to these thinkers, should adhere to several constraints on the manner in which they support coercive laws, including the following.

First, liberal critics of the standard view assume that citizens should support basic liberal commitments such as the rights to religious freedom, equality before the law, and private property. Michael Perry argues, for example, “that the foundational moral commitment of liberal democracy is to the true and full humanity of ever y person—and therefore, to the inviolability of every person—without regard to race, sex, religion… .” This commitment, Perry continues, is “the principal ground of liberal democracy's further commitment to certain basic human freedoms” that are protected by law (Perry 2003, 36). [ 13 ] More generally, liberal critics maintain that citizens should support only those coercive laws that they reasonably believe further the common good and are consistent with the demands of justice. These commitments, they add, are not in tension with the claim that citizens may support coercive laws that they believe to lack a plausible secular rationale. So long as a citizen is firmly committed to basic liberal rights, she may coherently and without impropriety do so even though she regards these laws as having no plausible secular justification. More generally, liberal critics of the DRR maintain that a citizen may rely on her religious convictions to determine which policies further the cause of justice and the common good and may support coercive laws even if she regards them as having no plausible secular rationale.

Second, liberal critics of the standard view lay down constraints on the manner in which citizens arrive at their political commitments (see Eberle 2002, Weithman 2002, and Wolterstorff 1997, 2012a). So, for example, each citizen should abide by certain epistemic requirements: precisely because they ought not to support coercive laws that violate the requirements of justice and the common good, citizens should take feasible measures to determine whether the laws they support are actually just and good. In order to achieve that aim, citizens should search for considerations relevant to the normative propriety of their favored laws, weigh those considerations judiciously, listen carefully to the criticisms of those who reject their normative commitments, and be willing to change their political commitments should the balance of relevant considerations require them to do so. Again, liberal critics deny that even the most conscientious and assiduous adherence to such constraints precludes citizens from supporting coercive laws that require a religious rationale. No doubt, those who support coercive laws that require a religious rationale might do so in an insular, intransigent, irrational, or otherwise defective manner. But they need not do so and, thus, their religiously-grounded support for coercive laws need not be defective.

Third, critics of the standard view need have no aversion to secular justification and so need not object to a state of affairs in which each person, secular or religious, has what he or she regards as a compelling reason to endorse coercive laws of various sorts. (Indeed, they claim that such a state of affairs would arguably be a significant moral achievement—a good for all concerned.) According to the liberal critics, however, what is most important is that parity reigns: any normative constraint that applies to the reasons on the basis of which citizens make political decisions must apply impartially to both religious and secular reasons. Many secular reasons employed to justify coercion—ones that appeal to comprehensive perspectives such as utilitarianism and Kantianism, for example—are highly controversial; in this sense, they are very similar to religious reasons. For this reason, some advocate for a cousin —more or less distant, depending on the formulation—of the DRR, namely, one that lays down restrictions on all religious reasons and on some particularly controversial secular reasons. (See section 6 below.) Moreover, the normative issues implicated by certain coercive laws are so complex and contentious that any rationale for or against these laws will include claims that can be reasonably rejected—secular or religious as the case might be.

If this is right, according to the liberal critics, equal treatment of religious and secular reasons is the order of the day: religious believers have no more, and no less, a responsibility to aspire to persuade their secular compatriots by appeal to secular reasons than secularists have an obligation to aspire to persuade their religious compatriots by appeal to religious reasons. Otherwise put, according to the liberal critics, if we accept the claim that:

If a religious citizen finds herself in a position in which she has excellent reason to believe that she cannot convince a fellow secular citizen to support a coercive law that she deems just by appeal to religious reasons, then she should do her best to appeal to secular reasons—reasons that her cohort may find persuasive;

we should also accept:

If a secular citizen finds herself in a position in which she has excellent reason to believe that she cannot convince a fellow religious citizen to support a coercive law that she deems just by appeal to secular reasons, then she should do her best to appeal to religious reasons—reasons that her cohort may find persuasive.

Recognizing parity of this sort, according to the liberal critics, lies at the heart of what it is to be a good citizen of a liberal democracy. For being a good citizen involves respecting one's fellow citizens, even when one disagrees with them. In a wide range of cases, however, an agent exercises respect not by treating her interlocutor as a generic human being or a generic citizen of a liberal democracy, but by treating her as a person who has a particular narrative identity and life history, say, as an African American, a Russian immigrant, or a Muslim citizen. But doing this often requires pursuing and appealing to considerations that it is likely that one's interlocutors with their own particular narrative identity will find persuasive. And depending on the case, these reasons may be exclusively religious.

To this we should add a clarification: strictly speaking, the liberal critics' insistence on parity between the pursuit of secular and religious reasons is consistent with the DRR. For, as we have construed it, the DRR allows that religious citizens may support coercive laws for religious reasons (so long as they have and are prepared to provide a plausible secular justification for these laws). And while its advocates do not typically emphasize the point, the DRR permits secular citizens to articulate religious reasons that will persuade religious believers to accept the secular citizens' favored coercive laws (for reservations about this practice, see Audi 1997, 135-37 on “leveraging reasons”. See also Schwartzman 2014). Still, the DRR implies that there is an important asymmetry between the justificatory role played by religious and secular reasons. To this issue we now turn.

Assume that, in religiously pluralistic conditions, religious citizens have good moral reason—perhaps even a moral obligation—to pursue secular reasons for their favored coercive laws. Assume as well that secular citizens have good reason to pursue religious reasons for their favored coercive policies (if only because, with respect to some coercive laws, some of their fellow citizens find only religious reasons to support them). What should citizens do, religious or secular, when they cannot identify these reasons?

According to advocates of the standard view, if a religious citizen fails in his pursuit of secular reasons that support a given coercive law, then he is morally required to exercise restraint. After all, if his pursuit of these reasons fails, then he does not have any secular reason to offer in favor of that law. Liberal critics of the standard view, by contrast, deny that citizens so circumstanced are morally required to exercise restraint. They claim that from the fact that religious citizens are morally required to pursue secular reasons for their favored coercive laws (when that is necessary for persuasion), it does not follow that they should refrain from supporting coercive laws if their pursuit of secular reasons fails. Because our having an obligation to try to bring about some state of affairs tells us nothing about what we ought to do if we cannot bring it about, nothing like the DRR follows from the claim that citizens should pursue secular reasons for their favored coercive laws. According to the liberal critics, a parallel position applies to non-religious citizens: from the fact that non-religious citizens are morally required to pursue religious reasons for their favored laws (when that is necessary for persuasion), it doesn't follow that they should refrain from supporting coercive laws if their pursuit of religious reasons fails. For the liberal critics, parity between the religious and the secular obtains both with respect to the obligation to pursue justifying reasons and with respect to the permission not to exercise restraint when that pursuit fails.

Have we identified a genuine point of disagreement between the liberal critics and advocates of the standard view? It seems so. If the liberal critics are correct, all that can be reasonably asked of religious citizens is that, in a pluralistic liberal democracy, they competently pursue secular reasons for the coercive laws they support. If the pursuit fails, then they may support these laws for exclusively religious reasons. Proponents of the standard view disagree, maintaining that if the pursuit fails, these citizens must exercise restraint. This disagreement is rooted in differing convictions about the justificatory role that religious reasons can play. Once again, advocates of the standard view maintain that religious reasons can play only a limited justificatory role: citizens must have and be prepared to offer (at least certain kinds of) secular reasons for any coercive law that they support, as religious reasons are not enough. The liberal critics deny this, maintaining that no persuasive arguments have been offered to believe this. The DRR highlights this disagreement, as it incorporates an assumption that religious and secular reasons play asymmetrical roles in justifying coercive laws. [ 14 ]

As we have explicated the view of the liberal critics, religious citizens are (in a wide range of cases) morally required to pursue secular reasons for their favored coercive laws, but they needn't exercise restraint if they fail in their pursuit. But this position raises a question: What's so bad about requiring citizens to exercise restraint? Why should liberal critics object to this?

According to the liberal critics, one of the core commitments of a liberal democracy is a commitment to religious freedom and its natural extension, the right to freedom of conscience. When citizens use the modicum of political influence at their disposal, liberal critics claim that we should want them to do so in a way that furthers the cause of justice and the common good. So, for example, when a citizen deliberates about whether he should, say, support the invasion of Afghanistan by the United States and its NATO allies, we want him to determine, as best he can, whether the invasion of Afghanistan is actually morally appropriate. In order to determine that, he should be as conscientious as he can in his collection and evaluation of the relevant evidence, reach whatever conclusions seem reasonable to him on the available evidence, and act accordingly. If he concludes that invading Afghanistan would be unjust, then he should oppose it. That he does so is not only his right but also morally excellent, as acting in accord with responsibly held normative commitments is an important moral and civic good.

This, the liberal critics maintain, suggests a general claim. Whatever the policy and whatever the reasons—whether religious or secular—we have powerful reason to want citizens to support the coercive policies that they believe, in good conscience, to be morally appropriate. But that general claim has direct application to the issue at hand. It is possible, the liberal critics claim, for a morally sensitive and epistemically competent citizen to regard only certain religious considerations as providing decisive support for a given coercive law. Nicholas Wolterstorff, to return to an earlier example, maintains that only theistic considerations can ground the ascription of inherent human rights, some of which are protected by coercive law. Arguably, were a citizen to find a position such as Wolterstorff's persuasive, then he should appeal to those considerations that he actually believes to further the cause of justice and the common good. And this should lead us to want him to support that law, even though he does so solely on religious grounds, even if he regards that law as having no plausible secular justification. Good citizenship in a pluralistic liberal democracy unavoidably requires citizens to make political commitments that they know their moral and epistemic peers reject but that they nevertheless believe, with due humility, to be morally required. This ideal of good citizenship, so the liberal critics claim, applies to religious and secular citizens alike.

The portrait that we have offered of the standard view (and that of its liberal critics) is a composite, one which blends together various claims that its advocates make about the relation between coercive law and religious reasons. Because of this approach we have made relatively little explicit mention of particular advocates of the standard view, such as that towering figure of contemporary political philosophy, John Rawls. Of all the contemporary figures who have shaped the debate we are considering, however, none has exercised more influence than Rawls. It is natural to wonder, then, whether we've presented the standard view in its most powerful form and, thus, whether we've omitted a crucial dimension of the debate between the standard view and its liberal critics. We believe not. The version of the standard view that we have considered is one that borrows liberally from Rawls' thought, albeit softened and modified in certain ways. Still, before moving forward, it will be helpful to say something more about Rawls' view. We limit ourselves to the following three observations.

First, Rawls' own position about the relation between coercive law and religious reasons has shifted. In Political Liberalism , Rawls admits that at one point he inclined toward accepting an ambitious version of the DRR according to which each citizen of a liberal democracy ought not to appeal to religious reasons when deliberating about matters of basic justice and constitutional essentials (see Rawls 1993, 247 n.36). In the face of criticism, Rawls modified his position, arriving at a close relative of the DRR, viz., that while an agent may appeal to religious reasons to justify coercive law, he may not appeal solely to these reasons. Secular reasons must be forthcoming (see Rawls 1997). [ 15 ]

Second, Rawls places significant restrictions on the content of the secular reasons to which an agent may appeal. To advert to a point made earlier, Rawls argues that when deliberating about matters of basic justice and constitutional essentials, citizens should appeal to “public reason,” which (roughly speaking) is a fund of shared principles about justice and the common good that is constructed from the shared political culture of a liberal democracy—principles that concern, for example, the equality of citizens before the law and their right to a fair system of cooperation. In Rawls' view, when deliberating about these matters, appealing solely to secular comprehensive accounts of the good such as Aristotelianism or utilitarianism is no more legitimate than appealing solely to religious reasons. For all of these comprehensive doctrines will be alien to some of one's reasonable compatriots.