45 Research Problem Examples & Inspiration

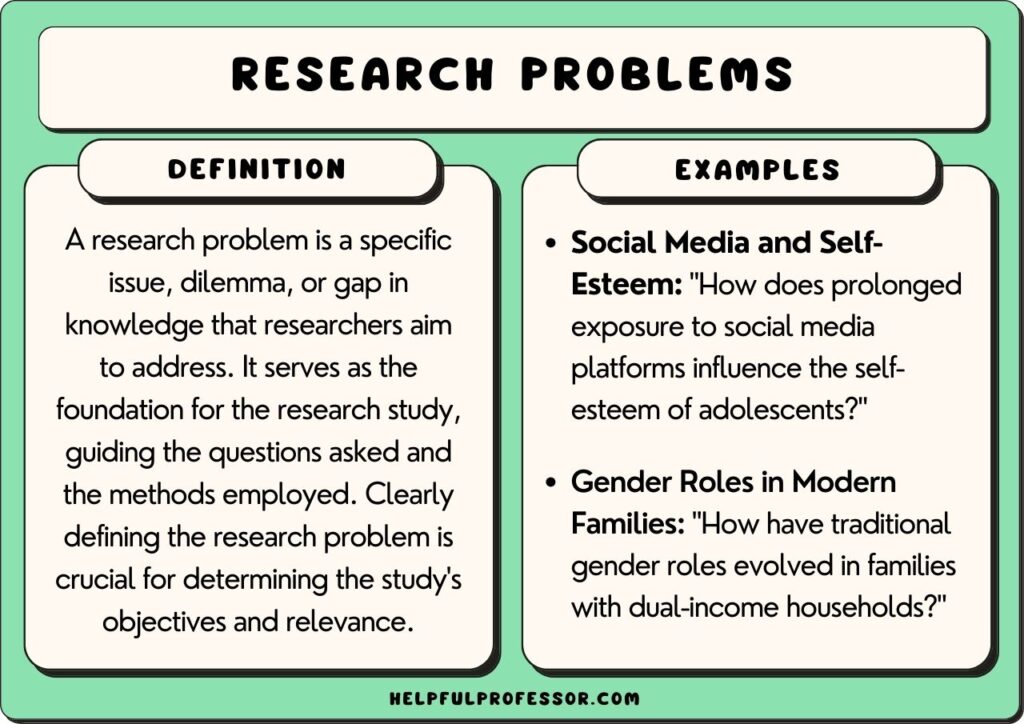

A research problem is an issue of concern that is the catalyst for your research. It demonstrates why the research problem needs to take place in the first place.

Generally, you will write your research problem as a clear, concise, and focused statement that identifies an issue or gap in current knowledge that requires investigation.

The problem will likely also guide the direction and purpose of a study. Depending on the problem, you will identify a suitable methodology that will help address the problem and bring solutions to light.

Research Problem Examples

In the following examples, I’ll present some problems worth addressing, and some suggested theoretical frameworks and research methodologies that might fit with the study. Note, however, that these aren’t the only ways to approach the problems. Keep an open mind and consult with your dissertation supervisor!

Psychology Problems

1. Social Media and Self-Esteem: “How does prolonged exposure to social media platforms influence the self-esteem of adolescents?”

- Theoretical Framework : Social Comparison Theory

- Methodology : Longitudinal study tracking adolescents’ social media usage and self-esteem measures over time, combined with qualitative interviews.

2. Sleep and Cognitive Performance: “How does sleep quality and duration impact cognitive performance in adults?”

- Theoretical Framework : Cognitive Psychology

- Methodology : Experimental design with controlled sleep conditions, followed by cognitive tests. Participant sleep patterns can also be monitored using actigraphy.

3. Childhood Trauma and Adult Relationships: “How does unresolved childhood trauma influence attachment styles and relationship dynamics in adulthood?

- Theoretical Framework : Attachment Theory

- Methodology : Mixed methods, combining quantitative measures of attachment styles with qualitative in-depth interviews exploring past trauma and current relationship dynamics.

4. Mindfulness and Stress Reduction: “How effective is mindfulness meditation in reducing perceived stress and physiological markers of stress in working professionals?”

- Theoretical Framework : Humanist Psychology

- Methodology : Randomized controlled trial comparing a group practicing mindfulness meditation to a control group, measuring both self-reported stress and physiological markers (e.g., cortisol levels).

5. Implicit Bias and Decision Making: “To what extent do implicit biases influence decision-making processes in hiring practices?

- Theoretical Framework : Cognitive Dissonance Theory

- Methodology : Experimental design using Implicit Association Tests (IAT) to measure implicit biases, followed by simulated hiring tasks to observe decision-making behaviors.

6. Emotional Regulation and Academic Performance: “How does the ability to regulate emotions impact academic performance in college students?”

- Theoretical Framework : Cognitive Theory of Emotion

- Methodology : Quantitative surveys measuring emotional regulation strategies, combined with academic performance metrics (e.g., GPA).

7. Nature Exposure and Mental Well-being: “Does regular exposure to natural environments improve mental well-being and reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression?”

- Theoretical Framework : Biophilia Hypothesis

- Methodology : Longitudinal study comparing mental health measures of individuals with regular nature exposure to those without, possibly using ecological momentary assessment for real-time data collection.

8. Video Games and Cognitive Skills: “How do action video games influence cognitive skills such as attention, spatial reasoning, and problem-solving?”

- Theoretical Framework : Cognitive Load Theory

- Methodology : Experimental design with pre- and post-tests, comparing cognitive skills of participants before and after a period of action video game play.

9. Parenting Styles and Child Resilience: “How do different parenting styles influence the development of resilience in children facing adversities?”

- Theoretical Framework : Baumrind’s Parenting Styles Inventory

- Methodology : Mixed methods, combining quantitative measures of resilience and parenting styles with qualitative interviews exploring children’s experiences and perceptions.

10. Memory and Aging: “How does the aging process impact episodic memory , and what strategies can mitigate age-related memory decline?

- Theoretical Framework : Information Processing Theory

- Methodology : Cross-sectional study comparing episodic memory performance across different age groups, combined with interventions like memory training or mnemonic strategies to assess potential improvements.

Education Problems

11. Equity and Access : “How do socioeconomic factors influence students’ access to quality education, and what interventions can bridge the gap?

- Theoretical Framework : Critical Pedagogy

- Methodology : Mixed methods, combining quantitative data on student outcomes with qualitative interviews and focus groups with students, parents, and educators.

12. Digital Divide : How does the lack of access to technology and the internet affect remote learning outcomes, and how can this divide be addressed?

- Theoretical Framework : Social Construction of Technology Theory

- Methodology : Survey research to gather data on access to technology, followed by case studies in selected areas.

13. Teacher Efficacy : “What factors contribute to teacher self-efficacy, and how does it impact student achievement?”

- Theoretical Framework : Bandura’s Self-Efficacy Theory

- Methodology : Quantitative surveys to measure teacher self-efficacy, combined with qualitative interviews to explore factors affecting it.

14. Curriculum Relevance : “How can curricula be made more relevant to diverse student populations, incorporating cultural and local contexts?”

- Theoretical Framework : Sociocultural Theory

- Methodology : Content analysis of curricula, combined with focus groups with students and teachers.

15. Special Education : “What are the most effective instructional strategies for students with specific learning disabilities?

- Theoretical Framework : Social Learning Theory

- Methodology : Experimental design comparing different instructional strategies, with pre- and post-tests to measure student achievement.

16. Dropout Rates : “What factors contribute to high school dropout rates, and what interventions can help retain students?”

- Methodology : Longitudinal study tracking students over time, combined with interviews with dropouts.

17. Bilingual Education : “How does bilingual education impact cognitive development and academic achievement?

- Methodology : Comparative study of students in bilingual vs. monolingual programs, using standardized tests and qualitative interviews.

18. Classroom Management: “What reward strategies are most effective in managing diverse classrooms and promoting a positive learning environment?

- Theoretical Framework : Behaviorism (e.g., Skinner’s Operant Conditioning)

- Methodology : Observational research in classrooms , combined with teacher interviews.

19. Standardized Testing : “How do standardized tests affect student motivation, learning, and curriculum design?”

- Theoretical Framework : Critical Theory

- Methodology : Quantitative analysis of test scores and student outcomes, combined with qualitative interviews with educators and students.

20. STEM Education : “What methods can be employed to increase interest and proficiency in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) fields among underrepresented student groups?”

- Theoretical Framework : Constructivist Learning Theory

- Methodology : Experimental design comparing different instructional methods, with pre- and post-tests.

21. Social-Emotional Learning : “How can social-emotional learning be effectively integrated into the curriculum, and what are its impacts on student well-being and academic outcomes?”

- Theoretical Framework : Goleman’s Emotional Intelligence Theory

- Methodology : Mixed methods, combining quantitative measures of student well-being with qualitative interviews.

22. Parental Involvement : “How does parental involvement influence student achievement, and what strategies can schools use to increase it?”

- Theoretical Framework : Reggio Emilia’s Model (Community Engagement Focus)

- Methodology : Survey research with parents and teachers, combined with case studies in selected schools.

23. Early Childhood Education : “What are the long-term impacts of quality early childhood education on academic and life outcomes?”

- Theoretical Framework : Erikson’s Stages of Psychosocial Development

- Methodology : Longitudinal study comparing students with and without early childhood education, combined with observational research.

24. Teacher Training and Professional Development : “How can teacher training programs be improved to address the evolving needs of the 21st-century classroom?”

- Theoretical Framework : Adult Learning Theory (Andragogy)

- Methodology : Pre- and post-assessments of teacher competencies, combined with focus groups.

25. Educational Technology : “How can technology be effectively integrated into the classroom to enhance learning, and what are the potential drawbacks or challenges?”

- Theoretical Framework : Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK)

- Methodology : Experimental design comparing classrooms with and without specific technologies, combined with teacher and student interviews.

Sociology Problems

26. Urbanization and Social Ties: “How does rapid urbanization impact the strength and nature of social ties in communities?”

- Theoretical Framework : Structural Functionalism

- Methodology : Mixed methods, combining quantitative surveys on social ties with qualitative interviews in urbanizing areas.

27. Gender Roles in Modern Families: “How have traditional gender roles evolved in families with dual-income households?”

- Theoretical Framework : Gender Schema Theory

- Methodology : Qualitative interviews with dual-income families, combined with historical data analysis.

28. Social Media and Collective Behavior: “How does social media influence collective behaviors and the formation of social movements?”

- Theoretical Framework : Emergent Norm Theory

- Methodology : Content analysis of social media platforms, combined with quantitative surveys on participation in social movements.

29. Education and Social Mobility: “To what extent does access to quality education influence social mobility in socioeconomically diverse settings?”

- Methodology : Longitudinal study tracking educational access and subsequent socioeconomic status, combined with qualitative interviews.

30. Religion and Social Cohesion: “How do religious beliefs and practices contribute to social cohesion in multicultural societies?”

- Methodology : Quantitative surveys on religious beliefs and perceptions of social cohesion, combined with ethnographic studies.

31. Consumer Culture and Identity Formation: “How does consumer culture influence individual identity formation and personal values?”

- Theoretical Framework : Social Identity Theory

- Methodology : Mixed methods, combining content analysis of advertising with qualitative interviews on identity and values.

32. Migration and Cultural Assimilation: “How do migrants negotiate cultural assimilation and preservation of their original cultural identities in their host countries?”

- Theoretical Framework : Post-Structuralism

- Methodology : Qualitative interviews with migrants, combined with observational studies in multicultural communities.

33. Social Networks and Mental Health: “How do social networks, both online and offline, impact mental health and well-being?”

- Theoretical Framework : Social Network Theory

- Methodology : Quantitative surveys assessing social network characteristics and mental health metrics, combined with qualitative interviews.

34. Crime, Deviance, and Social Control: “How do societal norms and values shape definitions of crime and deviance, and how are these definitions enforced?”

- Theoretical Framework : Labeling Theory

- Methodology : Content analysis of legal documents and media, combined with ethnographic studies in diverse communities.

35. Technology and Social Interaction: “How has the proliferation of digital technology influenced face-to-face social interactions and community building?”

- Theoretical Framework : Technological Determinism

- Methodology : Mixed methods, combining quantitative surveys on technology use with qualitative observations of social interactions in various settings.

Nursing Problems

36. Patient Communication and Recovery: “How does effective nurse-patient communication influence patient recovery rates and overall satisfaction with care?”

- Methodology : Quantitative surveys assessing patient satisfaction and recovery metrics, combined with observational studies on nurse-patient interactions.

37. Stress Management in Nursing: “What are the primary sources of occupational stress for nurses, and how can they be effectively managed to prevent burnout?”

- Methodology : Mixed methods, combining quantitative measures of stress and burnout with qualitative interviews exploring personal experiences and coping mechanisms.

38. Hand Hygiene Compliance: “How effective are different interventions in improving hand hygiene compliance among nursing staff, and what are the barriers to consistent hand hygiene?”

- Methodology : Experimental design comparing hand hygiene rates before and after specific interventions, combined with focus groups to understand barriers.

39. Nurse-Patient Ratios and Patient Outcomes: “How do nurse-patient ratios impact patient outcomes, including recovery rates, complications, and hospital readmissions?”

- Methodology : Quantitative study analyzing patient outcomes in relation to staffing levels, possibly using retrospective chart reviews.

40. Continuing Education and Clinical Competence: “How does regular continuing education influence clinical competence and confidence among nurses?”

- Methodology : Longitudinal study tracking nurses’ clinical skills and confidence over time as they engage in continuing education, combined with patient outcome measures to assess potential impacts on care quality.

Communication Studies Problems

41. Media Representation and Public Perception: “How does media representation of minority groups influence public perceptions and biases?”

- Theoretical Framework : Cultivation Theory

- Methodology : Content analysis of media representations combined with quantitative surveys assessing public perceptions and attitudes.

42. Digital Communication and Relationship Building: “How has the rise of digital communication platforms impacted the way individuals build and maintain personal relationships?”

- Theoretical Framework : Social Penetration Theory

- Methodology : Mixed methods, combining quantitative surveys on digital communication habits with qualitative interviews exploring personal relationship dynamics.

43. Crisis Communication Effectiveness: “What strategies are most effective in managing public relations during organizational crises, and how do they influence public trust?”

- Theoretical Framework : Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT)

- Methodology : Case study analysis of past organizational crises, assessing communication strategies used and subsequent public trust metrics.

44. Nonverbal Cues in Virtual Communication: “How do nonverbal cues, such as facial expressions and gestures, influence message interpretation in virtual communication platforms?”

- Theoretical Framework : Social Semiotics

- Methodology : Experimental design using video conferencing tools, analyzing participants’ interpretations of messages with varying nonverbal cues.

45. Influence of Social Media on Political Engagement: “How does exposure to political content on social media platforms influence individuals’ political engagement and activism?”

- Theoretical Framework : Uses and Gratifications Theory

- Methodology : Quantitative surveys assessing social media habits and political engagement levels, combined with content analysis of political posts on popular platforms.

Before you Go: Tips and Tricks for Writing a Research Problem

This is an incredibly stressful time for research students. The research problem is going to lock you into a specific line of inquiry for the rest of your studies.

So, here’s what I tend to suggest to my students:

- Start with something you find intellectually stimulating – Too many students choose projects because they think it hasn’t been studies or they’ve found a research gap. Don’t over-estimate the importance of finding a research gap. There are gaps in every line of inquiry. For now, just find a topic you think you can really sink your teeth into and will enjoy learning about.

- Take 5 ideas to your supervisor – Approach your research supervisor, professor, lecturer, TA, our course leader with 5 research problem ideas and run each by them. The supervisor will have valuable insights that you didn’t consider that will help you narrow-down and refine your problem even more.

- Trust your supervisor – The supervisor-student relationship is often very strained and stressful. While of course this is your project, your supervisor knows the internal politics and conventions of academic research. The depth of knowledge about how to navigate academia and get you out the other end with your degree is invaluable. Don’t underestimate their advice.

I’ve got a full article on all my tips and tricks for doing research projects right here – I recommend reading it:

- 9 Tips on How to Choose a Dissertation Topic

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Animism Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 10 Magical Thinking Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Social-Emotional Learning (Definition, Examples, Pros & Cons)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ What is Educational Psychology?

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you’re on board with our cookie policy

- A Research Guide

- Research Paper Topics

- 35 Research Paper Problem Topics & Examples

35 Research Paper Problem Topics & Examples

Read also: How to do a research paper and get an A

- Social media, blackmailing and cyberbullying

- The Incels and the threat they pose

- Can you help if your friend seems to have depression?

- Codependent relationships: how to get out?

- Dealing with narcissists you can’t just forget about

- When interrupting the personal life of other person can be justified?

- Living through the loss

- The phenomenon of “friend zone”, what can be done with it?

- Overcoming the culture clash

- Helping homeless people and resocializing them

- Fighting drug selling in schools and campuses

- The problem of drunk driving

- How to rise from the bottom of the social hierarchy?

- Dehumanizing people in prisons

- Preventing human trafficking

- Making healthy lifestyle a desired choice for the people

- Improving the ecology of your hometown

- Online data mining: how can we prevent it?

- Gender discrimination and sexism

- The problem of global hunger

- Underemployment and unemployment

- Balancing safety and the right to have private information

- Manipulative advertising

- Teaching children to spend more time offline

- Cheating at schools and colleges

- The problem of corruption

- The choice of religion for the children from religious families

- Modern beauty standards and positive body image

- Self-esteem issues

- Traffic problems: how to avoid traffic jams in your hometown?

- What can be done right now to reduce pollution?

- Money management on personal scale

- Strict dress code at schools and in the companies

- Overloading with information in the modern society

- Enhancing the quality of family life

By clicking "Log In", you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We'll occasionally send you account related and promo emails.

Sign Up for your FREE account

Academic Experience

How to identify and resolve research problems

Updated July 12, 2023

In this article, we’re going to take you through one of the most pertinent parts of conducting research: a research problem (also known as a research problem statement).

When trying to formulate a good research statement, and understand how to solve it for complex projects, it can be difficult to know where to start.

Not only are there multiple perspectives (from stakeholders to project marketers who want answers), you have to consider the particular context of the research topic: is it timely, is it relevant and most importantly of all, is it valuable?

In other words: are you looking at a research worthy problem?

The fact is, a well-defined, precise, and goal-centric research problem will keep your researchers, stakeholders, and business-focused and your results actionable.

And when it works well, it's a powerful tool to identify practical solutions that can drive change and secure buy-in from your workforce.

Free eBook: The ultimate guide to market research

What is a research problem?

In social research methodology and behavioral sciences , a research problem establishes the direction of research, often relating to a specific topic or opportunity for discussion.

For example: climate change and sustainability, analyzing moral dilemmas or wage disparity amongst classes could all be areas that the research problem focuses on.

As well as outlining the topic and/or opportunity, a research problem will explain:

- why the area/issue needs to be addressed,

- why the area/issue is of importance,

- the parameters of the research study

- the research objective

- the reporting framework for the results and

- what the overall benefit of doing so will provide (whether to society as a whole or other researchers and projects).

Having identified the main topic or opportunity for discussion, you can then narrow it down into one or several specific questions that can be scrutinized and answered through the research process.

What are research questions?

Generating research questions underpinning your study usually starts with problems that require further research and understanding while fulfilling the objectives of the study.

A good problem statement begins by asking deeper questions to gain insights about a specific topic.

For example, using the problems above, our questions could be:

"How will climate change policies influence sustainability standards across specific geographies?"

"What measures can be taken to address wage disparity without increasing inflation?"

Developing a research worthy problem is the first step - and one of the most important - in any kind of research.

It’s also a task that will come up again and again because any business research process is cyclical. New questions arise as you iterate and progress through discovering, refining, and improving your products and processes. A research question can also be referred to as a "problem statement".

Note: good research supports multiple perspectives through empirical data. It’s focused on key concepts rather than a broad area, providing readily actionable insight and areas for further research.

Research question or research problem?

As we've highlighted, the terms “research question” and “research problem” are often used interchangeably, becoming a vague or broad proposition for many.

The term "problem statement" is far more representative, but finds little use among academics.

Instead, some researchers think in terms of a single research problem and several research questions that arise from it.

As mentioned above, the questions are lines of inquiry to explore in trying to solve the overarching research problem.

Ultimately, this provides a more meaningful understanding of a topic area.

It may be useful to think of questions and problems as coming out of your business data – that’s the O-data (otherwise known as operational data) like sales figures and website metrics.

What's an example of a research problem?

Your overall research problem could be: "How do we improve sales across EMEA and reduce lost deals?"

This research problem then has a subset of questions, such as:

"Why do sales peak at certain times of the day?"

"Why are customers abandoning their online carts at the point of sale?"

As well as helping you to solve business problems, research problems (and associated questions) help you to think critically about topics and/or issues (business or otherwise). You can also use your old research to aid future research -- a good example is laying the foundation for comparative trend reports or a complex research project.

(Also, if you want to see the bigger picture when it comes to research problems, why not check out our ultimate guide to market research? In it you'll find out: what effective market research looks like, the use cases for market research, carrying out a research study, and how to examine and action research findings).

The research process: why are research problems important?

A research problem has two essential roles in setting your research project on a course for success.

1. They set the scope

The research problem defines what problem or opportunity you’re looking at and what your research goals are. It stops you from getting side-tracked or allowing the scope of research to creep off-course .

Without a strong research problem or problem statement, your team could end up spending resources unnecessarily, or coming up with results that aren’t actionable - or worse, harmful to your business - because the field of study is too broad.

2. They tie your work to business goals and actions

To formulate a research problem in terms of business decisions means you always have clarity on what’s needed to make those decisions. You can show the effects of what you’ve studied using real outcomes.

Then, by focusing your research problem statement on a series of questions tied to business objectives, you can reduce the risk of the research being unactionable or inaccurate.

It's also worth examining research or other scholarly literature (you’ll find plenty of similar, pertinent research online) to see how others have explored specific topics and noting implications that could have for your research.

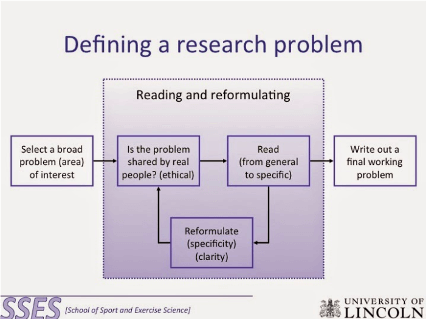

Four steps to defining your research problem

Image credit: http://myfreeschooltanzania.blogspot.com/2014/11/defining-research-problem.html

1. Observe and identify

Businesses today have so much data that it can be difficult to know which problems to address first. Researchers also have business stakeholders who come to them with problems they would like to have explored. A researcher’s job is to sift through these inputs and discover exactly what higher-level trends and key concepts are worth investing in.

This often means asking questions and doing some initial investigation to decide which avenues to pursue. This could mean gathering interdisciplinary perspectives identifying additional expertise and contextual information.

Sometimes, a small-scale preliminary study might be worth doing to help get a more comprehensive understanding of the business context and needs, and to make sure your research problem addresses the most critical questions.

This could take the form of qualitative research using a few in-depth interviews , an environmental scan, or reviewing relevant literature.

The sales manager of a sportswear company has a problem: sales of trail running shoes are down year-on-year and she isn’t sure why. She approaches the company’s research team for input and they begin asking questions within the company and reviewing their knowledge of the wider market.

2. Review the key factors involved

As a marketing researcher, you must work closely with your team of researchers to define and test the influencing factors and the wider context involved in your study. These might include demographic and economic trends or the business environment affecting the question at hand. This is referred to as a relational research problem.

To do this, you have to identify the factors that will affect the research and begin formulating different methods to control them.

You also need to consider the relationships between factors and the degree of control you have over them. For example, you may be able to control the loading speed of your website but you can’t control the fluctuations of the stock market.

Doing this will help you determine whether the findings of your project will produce enough information to be worth the cost.

You need to determine:

- which factors affect the solution to the research proposal.

- which ones can be controlled and used for the purposes of the company, and to what extent.

- the functional relationships between the factors.

- which ones are critical to the solution of the research study.

The research team at the running shoe company is hard at work. They explore the factors involved and the context of why YoY sales are down for trail shoes, including things like what the company’s competitors are doing, what the weather has been like – affecting outdoor exercise – and the relative spend on marketing for the brand from year to year.

The final factor is within the company’s control, although the first two are not. They check the figures and determine marketing spend has a significant impact on the company.

3. Prioritize

Once you and your research team have a few observations, prioritize them based on their business impact and importance. It may be that you can answer more than one question with a single study, but don’t do it at the risk of losing focus on your overarching research problem.

Questions to ask:

- Who? Who are the people with the problem? Are they end-users, stakeholders, teams within your business? Have you validated the information to see what the scale of the problem is?

- What? What is its nature and what is the supporting evidence?

- Why? What is the business case for solving the problem? How will it help?

- Where? How does the problem manifest and where is it observed?

To help you understand all dimensions, you might want to consider focus groups or preliminary interviews with external (including consumers and existing customers) and internal (salespeople, managers, and other stakeholders) parties to provide what is sometimes much-needed insight into a particular set of questions or problems.

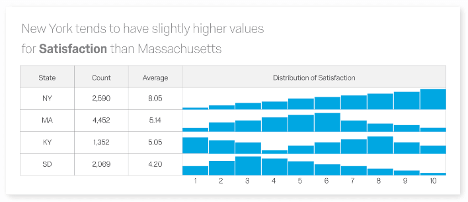

After observing and investigating, the running shoe researchers come up with a few candidate questions, including:

- What is the relationship between US average temperatures and sales of our products year on year?

- At present, how does our customer base rank Competitor X and Competitor Y’s trail running shoe compared to our brand?

- What is the relationship between marketing spend and trail shoe product sales over the last 12 months?

They opt for the final question, because the variables involved are fully within the company’s control, and based on their initial research and stakeholder input, seem the most likely cause of the dive in sales. The research question is specific enough to keep the work on course towards an actionable result, but it allows for a few different avenues to be explored, such as the different budget allocations of offline and online marketing and the kinds of messaging used.

Get feedback from the key teams within your business to make sure everyone is aligned and has the same understanding of the research problem and questions, and the actions you hope to take based on the results. Now is also a good time to demonstrate the ROI of your research and lay out its potential benefits to your stakeholders.

Different groups may have different goals and perspectives on the issue. This step is vital for getting the necessary buy-in and pushing the project forward.

The running shoe company researchers now have everything they need to begin. They call a meeting with the sales manager and consult with the product team, marketing team, and C-suite to make sure everyone is aligned and has bought into the direction of the research topic. They identify and agree that the likely course of action will be a rethink of how marketing resources are allocated, and potentially testing out some new channels and messaging strategies .

Can you explore a broad area and is it practical to do so?

A broader research problem or report can be a great way to bring attention to prevalent issues, societal or otherwise, but are often undertaken by those with the resources to do so.

Take a typical government cybersecurity breach survey, for example. Most of these reports raise awareness of cybercrime, from the day-to-day threats businesses face to what security measures some organizations are taking. What these reports don't do, however, is provide actionable advice - mostly because every organization is different.

The point here is that while some researchers will explore a very complex issue in detail, others will provide only a snapshot to maintain interest and encourage further investigation. The "value" of the data is wholly determined by the recipients of it - and what information you choose to include.

To summarize, it can be practical to undertake a broader research problem, certainly, but it may not be possible to cover everything or provide the detail your audience needs. Likewise, a more systematic investigation of an issue or topic will be more valuable, but you may also find that you cover far less ground.

It's important to think about your research objectives and expected findings before going ahead.

Ensuring your research project is a success

A complex research project can be made significantly easier with clear research objectives, a descriptive research problem, and a central focus. All of which we've outlined in this article.

If you have previous research, even better. Use it as a benchmark

Remember: what separates a good research paper from an average one is actually very simple: valuable, empirical data that explores a prevalent societal or business issue and provides actionable insights.

And we can help.

Sophisticated research made simple with Qualtrics

Trusted by the world's best brands, our platform enables researchers from academic to corporate to tackle the hardest challenges and deliver the results that matter.

Our CoreXM platform supports the methods that define superior research and delivers insights in real-time. It's easy to use (thanks to drag-and-drop functionality) and requires no coding, meaning you'll be capturing data and gleaning insights in no time.

It also excels in flexibility; you can track consumer behavior across segments , benchmark your company versus competitors , carry out complex academic research, and do much more, all from one system.

It's one platform with endless applications, so no matter your research problem, we've got the tools to help you solve it. And if you don't have a team of research experts in-house, our market research team has the practical knowledge and tools to help design the surveys and find the respondents you need.

Of course, you may want to know where to begin with your own market research . If you're struggling, make sure to download our ultimate guide using the link below.

It's got everything you need and there’s always information in our research methods knowledge base.

Scott Smith

Scott Smith, Ph.D. is a contributor to the Qualtrics blog.

Related Articles

April 1, 2023

Great survey questions: How to write them & avoid common mistakes

February 8, 2023

Smoothing the transition from school to work with work-based learning

December 6, 2022

How customer experience helps bring Open Universities Australia’s brand promise to life

August 18, 2022

School safety, learning gaps top of mind for parents this back-to-school season

August 9, 2022

3 things that will improve your teachers’ school experience

August 2, 2022

Why a sense of belonging at school matters for K-12 students

July 14, 2022

Improve the student experience with simplified course evaluations

March 17, 2022

Understanding what’s important to college students

Stay up to date with the latest xm thought leadership, tips and news., request demo.

Ready to learn more about Qualtrics?

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- The Research Problem/Question

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

A research problem is a definite or clear expression [statement] about an area of concern, a condition to be improved upon, a difficulty to be eliminated, or a troubling question that exists in scholarly literature, in theory, or within existing practice that points to a need for meaningful understanding and deliberate investigation. A research problem does not state how to do something, offer a vague or broad proposition, or present a value question. In the social and behavioral sciences, studies are most often framed around examining a problem that needs to be understood and resolved in order to improve society and the human condition.

Bryman, Alan. “The Research Question in Social Research: What is its Role?” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 10 (2007): 5-20; Guba, Egon G., and Yvonna S. Lincoln. “Competing Paradigms in Qualitative Research.” In Handbook of Qualitative Research . Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln, editors. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1994), pp. 105-117; Pardede, Parlindungan. “Identifying and Formulating the Research Problem." Research in ELT: Module 4 (October 2018): 1-13; Li, Yanmei, and Sumei Zhang. "Identifying the Research Problem." In Applied Research Methods in Urban and Regional Planning . (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2022), pp. 13-21.

Importance of...

The purpose of a problem statement is to:

- Introduce the reader to the importance of the topic being studied . The reader is oriented to the significance of the study.

- Anchors the research questions, hypotheses, or assumptions to follow . It offers a concise statement about the purpose of your paper.

- Place the topic into a particular context that defines the parameters of what is to be investigated.

- Provide the framework for reporting the results and indicates what is probably necessary to conduct the study and explain how the findings will present this information.

In the social sciences, the research problem establishes the means by which you must answer the "So What?" question. This declarative question refers to a research problem surviving the relevancy test [the quality of a measurement procedure that provides repeatability and accuracy]. Note that answering the "So What?" question requires a commitment on your part to not only show that you have reviewed the literature, but that you have thoroughly considered the significance of the research problem and its implications applied to creating new knowledge and understanding or informing practice.

To survive the "So What" question, problem statements should possess the following attributes:

- Clarity and precision [a well-written statement does not make sweeping generalizations and irresponsible pronouncements; it also does include unspecific determinates like "very" or "giant"],

- Demonstrate a researchable topic or issue [i.e., feasibility of conducting the study is based upon access to information that can be effectively acquired, gathered, interpreted, synthesized, and understood],

- Identification of what would be studied, while avoiding the use of value-laden words and terms,

- Identification of an overarching question or small set of questions accompanied by key factors or variables,

- Identification of key concepts and terms,

- Articulation of the study's conceptual boundaries or parameters or limitations,

- Some generalizability in regards to applicability and bringing results into general use,

- Conveyance of the study's importance, benefits, and justification [i.e., regardless of the type of research, it is important to demonstrate that the research is not trivial],

- Does not have unnecessary jargon or overly complex sentence constructions; and,

- Conveyance of more than the mere gathering of descriptive data providing only a snapshot of the issue or phenomenon under investigation.

Bryman, Alan. “The Research Question in Social Research: What is its Role?” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 10 (2007): 5-20; Brown, Perry J., Allen Dyer, and Ross S. Whaley. "Recreation Research—So What?" Journal of Leisure Research 5 (1973): 16-24; Castellanos, Susie. Critical Writing and Thinking. The Writing Center. Dean of the College. Brown University; Ellis, Timothy J. and Yair Levy Nova. "Framework of Problem-Based Research: A Guide for Novice Researchers on the Development of a Research-Worthy Problem." Informing Science: the International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline 11 (2008); Thesis and Purpose Statements. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Thesis Statements. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Tips and Examples for Writing Thesis Statements. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Selwyn, Neil. "‘So What?’…A Question that Every Journal Article Needs to Answer." Learning, Media, and Technology 39 (2014): 1-5; Shoket, Mohd. "Research Problem: Identification and Formulation." International Journal of Research 1 (May 2014): 512-518.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Types and Content

There are four general conceptualizations of a research problem in the social sciences:

- Casuist Research Problem -- this type of problem relates to the determination of right and wrong in questions of conduct or conscience by analyzing moral dilemmas through the application of general rules and the careful distinction of special cases.

- Difference Research Problem -- typically asks the question, “Is there a difference between two or more groups or treatments?” This type of problem statement is used when the researcher compares or contrasts two or more phenomena. This a common approach to defining a problem in the clinical social sciences or behavioral sciences.

- Descriptive Research Problem -- typically asks the question, "what is...?" with the underlying purpose to describe the significance of a situation, state, or existence of a specific phenomenon. This problem is often associated with revealing hidden or understudied issues.

- Relational Research Problem -- suggests a relationship of some sort between two or more variables to be investigated. The underlying purpose is to investigate specific qualities or characteristics that may be connected in some way.

A problem statement in the social sciences should contain :

- A lead-in that helps ensure the reader will maintain interest over the study,

- A declaration of originality [e.g., mentioning a knowledge void or a lack of clarity about a topic that will be revealed in the literature review of prior research],

- An indication of the central focus of the study [establishing the boundaries of analysis], and

- An explanation of the study's significance or the benefits to be derived from investigating the research problem.

NOTE : A statement describing the research problem of your paper should not be viewed as a thesis statement that you may be familiar with from high school. Given the content listed above, a description of the research problem is usually a short paragraph in length.

II. Sources of Problems for Investigation

The identification of a problem to study can be challenging, not because there's a lack of issues that could be investigated, but due to the challenge of formulating an academically relevant and researchable problem which is unique and does not simply duplicate the work of others. To facilitate how you might select a problem from which to build a research study, consider these sources of inspiration:

Deductions from Theory This relates to deductions made from social philosophy or generalizations embodied in life and in society that the researcher is familiar with. These deductions from human behavior are then placed within an empirical frame of reference through research. From a theory, the researcher can formulate a research problem or hypothesis stating the expected findings in certain empirical situations. The research asks the question: “What relationship between variables will be observed if theory aptly summarizes the state of affairs?” One can then design and carry out a systematic investigation to assess whether empirical data confirm or reject the hypothesis, and hence, the theory.

Interdisciplinary Perspectives Identifying a problem that forms the basis for a research study can come from academic movements and scholarship originating in disciplines outside of your primary area of study. This can be an intellectually stimulating exercise. A review of pertinent literature should include examining research from related disciplines that can reveal new avenues of exploration and analysis. An interdisciplinary approach to selecting a research problem offers an opportunity to construct a more comprehensive understanding of a very complex issue that any single discipline may be able to provide.

Interviewing Practitioners The identification of research problems about particular topics can arise from formal interviews or informal discussions with practitioners who provide insight into new directions for future research and how to make research findings more relevant to practice. Discussions with experts in the field, such as, teachers, social workers, health care providers, lawyers, business leaders, etc., offers the chance to identify practical, “real world” problems that may be understudied or ignored within academic circles. This approach also provides some practical knowledge which may help in the process of designing and conducting your study.

Personal Experience Don't undervalue your everyday experiences or encounters as worthwhile problems for investigation. Think critically about your own experiences and/or frustrations with an issue facing society or related to your community, your neighborhood, your family, or your personal life. This can be derived, for example, from deliberate observations of certain relationships for which there is no clear explanation or witnessing an event that appears harmful to a person or group or that is out of the ordinary.

Relevant Literature The selection of a research problem can be derived from a thorough review of pertinent research associated with your overall area of interest. This may reveal where gaps exist in understanding a topic or where an issue has been understudied. Research may be conducted to: 1) fill such gaps in knowledge; 2) evaluate if the methodologies employed in prior studies can be adapted to solve other problems; or, 3) determine if a similar study could be conducted in a different subject area or applied in a different context or to different study sample [i.e., different setting or different group of people]. Also, authors frequently conclude their studies by noting implications for further research; read the conclusion of pertinent studies because statements about further research can be a valuable source for identifying new problems to investigate. The fact that a researcher has identified a topic worthy of further exploration validates the fact it is worth pursuing.

III. What Makes a Good Research Statement?

A good problem statement begins by introducing the broad area in which your research is centered, gradually leading the reader to the more specific issues you are investigating. The statement need not be lengthy, but a good research problem should incorporate the following features:

1. Compelling Topic The problem chosen should be one that motivates you to address it but simple curiosity is not a good enough reason to pursue a research study because this does not indicate significance. The problem that you choose to explore must be important to you, but it must also be viewed as important by your readers and to a the larger academic and/or social community that could be impacted by the results of your study. 2. Supports Multiple Perspectives The problem must be phrased in a way that avoids dichotomies and instead supports the generation and exploration of multiple perspectives. A general rule of thumb in the social sciences is that a good research problem is one that would generate a variety of viewpoints from a composite audience made up of reasonable people. 3. Researchability This isn't a real word but it represents an important aspect of creating a good research statement. It seems a bit obvious, but you don't want to find yourself in the midst of investigating a complex research project and realize that you don't have enough prior research to draw from for your analysis. There's nothing inherently wrong with original research, but you must choose research problems that can be supported, in some way, by the resources available to you. If you are not sure if something is researchable, don't assume that it isn't if you don't find information right away--seek help from a librarian !

NOTE: Do not confuse a research problem with a research topic. A topic is something to read and obtain information about, whereas a problem is something to be solved or framed as a question raised for inquiry, consideration, or solution, or explained as a source of perplexity, distress, or vexation. In short, a research topic is something to be understood; a research problem is something that needs to be investigated.

IV. Asking Analytical Questions about the Research Problem

Research problems in the social and behavioral sciences are often analyzed around critical questions that must be investigated. These questions can be explicitly listed in the introduction [i.e., "This study addresses three research questions about women's psychological recovery from domestic abuse in multi-generational home settings..."], or, the questions are implied in the text as specific areas of study related to the research problem. Explicitly listing your research questions at the end of your introduction can help in designing a clear roadmap of what you plan to address in your study, whereas, implicitly integrating them into the text of the introduction allows you to create a more compelling narrative around the key issues under investigation. Either approach is appropriate.

The number of questions you attempt to address should be based on the complexity of the problem you are investigating and what areas of inquiry you find most critical to study. Practical considerations, such as, the length of the paper you are writing or the availability of resources to analyze the issue can also factor in how many questions to ask. In general, however, there should be no more than four research questions underpinning a single research problem.

Given this, well-developed analytical questions can focus on any of the following:

- Highlights a genuine dilemma, area of ambiguity, or point of confusion about a topic open to interpretation by your readers;

- Yields an answer that is unexpected and not obvious rather than inevitable and self-evident;

- Provokes meaningful thought or discussion;

- Raises the visibility of the key ideas or concepts that may be understudied or hidden;

- Suggests the need for complex analysis or argument rather than a basic description or summary; and,

- Offers a specific path of inquiry that avoids eliciting generalizations about the problem.

NOTE: Questions of how and why concerning a research problem often require more analysis than questions about who, what, where, and when. You should still ask yourself these latter questions, however. Thinking introspectively about the who, what, where, and when of a research problem can help ensure that you have thoroughly considered all aspects of the problem under investigation and helps define the scope of the study in relation to the problem.

V. Mistakes to Avoid

Beware of circular reasoning! Do not state the research problem as simply the absence of the thing you are suggesting. For example, if you propose the following, "The problem in this community is that there is no hospital," this only leads to a research problem where:

- The need is for a hospital

- The objective is to create a hospital

- The method is to plan for building a hospital, and

- The evaluation is to measure if there is a hospital or not.

This is an example of a research problem that fails the "So What?" test . In this example, the problem does not reveal the relevance of why you are investigating the fact there is no hospital in the community [e.g., perhaps there's a hospital in the community ten miles away]; it does not elucidate the significance of why one should study the fact there is no hospital in the community [e.g., that hospital in the community ten miles away has no emergency room]; the research problem does not offer an intellectual pathway towards adding new knowledge or clarifying prior knowledge [e.g., the county in which there is no hospital already conducted a study about the need for a hospital, but it was conducted ten years ago]; and, the problem does not offer meaningful outcomes that lead to recommendations that can be generalized for other situations or that could suggest areas for further research [e.g., the challenges of building a new hospital serves as a case study for other communities].

Alvesson, Mats and Jörgen Sandberg. “Generating Research Questions Through Problematization.” Academy of Management Review 36 (April 2011): 247-271 ; Choosing and Refining Topics. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; D'Souza, Victor S. "Use of Induction and Deduction in Research in Social Sciences: An Illustration." Journal of the Indian Law Institute 24 (1982): 655-661; Ellis, Timothy J. and Yair Levy Nova. "Framework of Problem-Based Research: A Guide for Novice Researchers on the Development of a Research-Worthy Problem." Informing Science: the International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline 11 (2008); How to Write a Research Question. The Writing Center. George Mason University; Invention: Developing a Thesis Statement. The Reading/Writing Center. Hunter College; Problem Statements PowerPoint Presentation. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Procter, Margaret. Using Thesis Statements. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Shoket, Mohd. "Research Problem: Identification and Formulation." International Journal of Research 1 (May 2014): 512-518; Trochim, William M.K. Problem Formulation. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006; Thesis and Purpose Statements. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Thesis Statements. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Tips and Examples for Writing Thesis Statements. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Pardede, Parlindungan. “Identifying and Formulating the Research Problem." Research in ELT: Module 4 (October 2018): 1-13; Walk, Kerry. Asking an Analytical Question. [Class handout or worksheet]. Princeton University; White, Patrick. Developing Research Questions: A Guide for Social Scientists . New York: Palgrave McMillan, 2009; Li, Yanmei, and Sumei Zhang. "Identifying the Research Problem." In Applied Research Methods in Urban and Regional Planning . (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2022), pp. 13-21.

- << Previous: Background Information

- Next: Theoretical Framework >>

- Last Updated: May 18, 2024 11:38 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

The Research Problem & Statement

What they are & how to write them (with examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewed By: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) | March 2023

If you’re new to academic research, you’re bound to encounter the concept of a “ research problem ” or “ problem statement ” fairly early in your learning journey. Having a good research problem is essential, as it provides a foundation for developing high-quality research, from relatively small research papers to a full-length PhD dissertations and theses.

In this post, we’ll unpack what a research problem is and how it’s related to a problem statement . We’ll also share some examples and provide a step-by-step process you can follow to identify and evaluate study-worthy research problems for your own project.

Overview: Research Problem 101

What is a research problem.

- What is a problem statement?

Where do research problems come from?

- How to find a suitable research problem

- Key takeaways

A research problem is, at the simplest level, the core issue that a study will try to solve or (at least) examine. In other words, it’s an explicit declaration about the problem that your dissertation, thesis or research paper will address. More technically, it identifies the research gap that the study will attempt to fill (more on that later).

Let’s look at an example to make the research problem a little more tangible.

To justify a hypothetical study, you might argue that there’s currently a lack of research regarding the challenges experienced by first-generation college students when writing their dissertations [ PROBLEM ] . As a result, these students struggle to successfully complete their dissertations, leading to higher-than-average dropout rates [ CONSEQUENCE ]. Therefore, your study will aim to address this lack of research – i.e., this research problem [ SOLUTION ].

A research problem can be theoretical in nature, focusing on an area of academic research that is lacking in some way. Alternatively, a research problem can be more applied in nature, focused on finding a practical solution to an established problem within an industry or an organisation. In other words, theoretical research problems are motivated by the desire to grow the overall body of knowledge , while applied research problems are motivated by the need to find practical solutions to current real-world problems (such as the one in the example above).

As you can probably see, the research problem acts as the driving force behind any study , as it directly shapes the research aims, objectives and research questions , as well as the research approach. Therefore, it’s really important to develop a very clearly articulated research problem before you even start your research proposal . A vague research problem will lead to unfocused, potentially conflicting research aims, objectives and research questions .

What is a research problem statement?

As the name suggests, a problem statement (within a research context, at least) is an explicit statement that clearly and concisely articulates the specific research problem your study will address. While your research problem can span over multiple paragraphs, your problem statement should be brief , ideally no longer than one paragraph . Importantly, it must clearly state what the problem is (whether theoretical or practical in nature) and how the study will address it.

Here’s an example of a statement of the problem in a research context:

Rural communities across Ghana lack access to clean water, leading to high rates of waterborne illnesses and infant mortality. Despite this, there is little research investigating the effectiveness of community-led water supply projects within the Ghanaian context. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the effectiveness of such projects in improving access to clean water and reducing rates of waterborne illnesses in these communities.

As you can see, this problem statement clearly and concisely identifies the issue that needs to be addressed (i.e., a lack of research regarding the effectiveness of community-led water supply projects) and the research question that the study aims to answer (i.e., are community-led water supply projects effective in reducing waterborne illnesses?), all within one short paragraph.

Need a helping hand?

Wherever there is a lack of well-established and agreed-upon academic literature , there is an opportunity for research problems to arise, since there is a paucity of (credible) knowledge. In other words, research problems are derived from research gaps . These gaps can arise from various sources, including the emergence of new frontiers or new contexts, as well as disagreements within the existing research.

Let’s look at each of these scenarios:

New frontiers – new technologies, discoveries or breakthroughs can open up entirely new frontiers where there is very little existing research, thereby creating fresh research gaps. For example, as generative AI technology became accessible to the general public in 2023, the full implications and knock-on effects of this were (or perhaps, still are) largely unknown and therefore present multiple avenues for researchers to explore.

New contexts – very often, existing research tends to be concentrated on specific contexts and geographies. Therefore, even within well-studied fields, there is often a lack of research within niche contexts. For example, just because a study finds certain results within a western context doesn’t mean that it would necessarily find the same within an eastern context. If there’s reason to believe that results may vary across these geographies, a potential research gap emerges.

Disagreements – within many areas of existing research, there are (quite naturally) conflicting views between researchers, where each side presents strong points that pull in opposing directions. In such cases, it’s still somewhat uncertain as to which viewpoint (if any) is more accurate. As a result, there is room for further research in an attempt to “settle” the debate.

Of course, many other potential scenarios can give rise to research gaps, and consequently, research problems, but these common ones are a useful starting point. If you’re interested in research gaps, you can learn more here .

How to find a research problem

Given that research problems flow from research gaps , finding a strong research problem for your research project means that you’ll need to first identify a clear research gap. Below, we’ll present a four-step process to help you find and evaluate potential research problems.

If you’ve read our other articles about finding a research topic , you’ll find the process below very familiar as the research problem is the foundation of any study . In other words, finding a research problem is much the same as finding a research topic.

Step 1 – Identify your area of interest

Naturally, the starting point is to first identify a general area of interest . Chances are you already have something in mind, but if not, have a look at past dissertations and theses within your institution to get some inspiration. These present a goldmine of information as they’ll not only give you ideas for your own research, but they’ll also help you see exactly what the norms and expectations are for these types of projects.

At this stage, you don’t need to get super specific. The objective is simply to identify a couple of potential research areas that interest you. For example, if you’re undertaking research as part of a business degree, you may be interested in social media marketing strategies for small businesses, leadership strategies for multinational companies, etc.

Depending on the type of project you’re undertaking, there may also be restrictions or requirements regarding what topic areas you’re allowed to investigate, what type of methodology you can utilise, etc. So, be sure to first familiarise yourself with your institution’s specific requirements and keep these front of mind as you explore potential research ideas.

Step 2 – Review the literature and develop a shortlist

Once you’ve decided on an area that interests you, it’s time to sink your teeth into the literature . In other words, you’ll need to familiarise yourself with the existing research regarding your interest area. Google Scholar is a good starting point for this, as you can simply enter a few keywords and quickly get a feel for what’s out there. Keep an eye out for recent literature reviews and systematic review-type journal articles, as these will provide a good overview of the current state of research.

At this stage, you don’t need to read every journal article from start to finish . A good strategy is to pay attention to the abstract, intro and conclusion , as together these provide a snapshot of the key takeaways. As you work your way through the literature, keep an eye out for what’s missing – in other words, what questions does the current research not answer adequately (or at all)? Importantly, pay attention to the section titled “ further research is needed ”, typically found towards the very end of each journal article. This section will specifically outline potential research gaps that you can explore, based on the current state of knowledge (provided the article you’re looking at is recent).

Take the time to engage with the literature and develop a big-picture understanding of the current state of knowledge. Reviewing the literature takes time and is an iterative process , but it’s an essential part of the research process, so don’t cut corners at this stage.

As you work through the review process, take note of any potential research gaps that are of interest to you. From there, develop a shortlist of potential research gaps (and resultant research problems) – ideally 3 – 5 options that interest you.

Step 3 – Evaluate your potential options

Once you’ve developed your shortlist, you’ll need to evaluate your options to identify a winner. There are many potential evaluation criteria that you can use, but we’ll outline three common ones here: value, practicality and personal appeal.

Value – a good research problem needs to create value when successfully addressed. Ask yourself:

- Who will this study benefit (e.g., practitioners, researchers, academia)?

- How will it benefit them specifically?

- How much will it benefit them?

Practicality – a good research problem needs to be manageable in light of your resources. Ask yourself:

- What data will I need access to?

- What knowledge and skills will I need to undertake the analysis?

- What equipment or software will I need to process and/or analyse the data?

- How much time will I need?

- What costs might I incur?

Personal appeal – a research project is a commitment, so the research problem that you choose needs to be genuinely attractive and interesting to you. Ask yourself:

- How appealing is the prospect of solving this research problem (on a scale of 1 – 10)?

- Why, specifically, is it attractive (or unattractive) to me?

- Does the research align with my longer-term goals (e.g., career goals, educational path, etc)?

Depending on how many potential options you have, you may want to consider creating a spreadsheet where you numerically rate each of the options in terms of these criteria. Remember to also include any criteria specified by your institution . From there, tally up the numbers and pick a winner.

Step 4 – Craft your problem statement

Once you’ve selected your research problem, the final step is to craft a problem statement. Remember, your problem statement needs to be a concise outline of what the core issue is and how your study will address it. Aim to fit this within one paragraph – don’t waffle on. Have a look at the problem statement example we mentioned earlier if you need some inspiration.

Key Takeaways

We’ve covered a lot of ground. Let’s do a quick recap of the key takeaways:

- A research problem is an explanation of the issue that your study will try to solve. This explanation needs to highlight the problem , the consequence and the solution or response.

- A problem statement is a clear and concise summary of the research problem , typically contained within one paragraph.

- Research problems emerge from research gaps , which themselves can emerge from multiple potential sources, including new frontiers, new contexts or disagreements within the existing literature.

- To find a research problem, you need to first identify your area of interest , then review the literature and develop a shortlist, after which you’ll evaluate your options, select a winner and craft a problem statement .

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

I APPRECIATE YOUR CONCISE AND MIND-CAPTIVATING INSIGHTS ON THE STATEMENT OF PROBLEMS. PLEASE I STILL NEED SOME SAMPLES RELATED TO SUICIDES.

Very pleased and appreciate clear information.

Your videos and information have been a life saver for me throughout my dissertation journey. I wish I’d discovered them sooner. Thank you!

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Research Writing and Analysis

- NVivo Group and Study Sessions

- SPSS This link opens in a new window

- Statistical Analysis Group sessions

- Using Qualtrics

- Dissertation and Data Analysis Group Sessions

- Defense Schedule - Commons Calendar This link opens in a new window

- Research Process Flow Chart

- Research Alignment Chapter 1 This link opens in a new window

- Step 1: Seek Out Evidence

- Step 2: Explain

- Step 3: The Big Picture

- Step 4: Own It

- Step 5: Illustrate

- Annotated Bibliography

- Literature Review This link opens in a new window

- Systematic Reviews & Meta-Analyses

- How to Synthesize and Analyze

- Synthesis and Analysis Practice

- Synthesis and Analysis Group Sessions

- Problem Statement

- Purpose Statement

- Conceptual Framework

- Theoretical Framework

- Quantitative Research Questions

- Qualitative Research Questions

- Trustworthiness of Qualitative Data

- Analysis and Coding Example- Qualitative Data

- Thematic Data Analysis in Qualitative Design

- Dissertation to Journal Article This link opens in a new window

- International Journal of Online Graduate Education (IJOGE) This link opens in a new window

- Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning (JRIT&L) This link opens in a new window

Jump to DSE Guide

Problem statement overview.

The dissertation problem needs to be very focused because everything else from the dissertation research logically flows from the problem. You may say that the problem statement is the very core of a dissertation research study. If the problem is too big or too vague, it will be difficult to scope out a purpose that is manageable for one person, given the time available to execute and finish the dissertation research study.

Through your research, your aim is to obtain information that helps address a problem so it can be resolved. Note that the researcher does not actually solve the problem themselves by conducting research but provides new knowledge that can be used toward a resolution. Typically, the problem is solved (or partially solved) by practitioners in the field, using input from researchers.

Given the above, the problem statement should do three things :

- Specify and describe the problem (with appropriate citations)

- Explain the consequences of NOT solving the problem

- Explain the knowledge needed to solve the problem (i.e., what is currently unknown about the problem and its resolution – also referred to as a gap )

What is a problem?

The world is full of problems! Not all problems make good dissertation research problems, however, because they are either too big, complex, or risky for doctorate candidates to solve. A proper research problem can be defined as a specific, evidence-based, real-life issue faced by certain people or organizations that have significant negative implications to the involved parties.

Example of a proper, specific, evidence-based, real-life dissertation research problem:

“Only 6% of CEOs in Fortune 500 companies are women” (Center for Leadership Studies, 2019).

Specific refers to the scope of the problem, which should be sufficiently manageable and focused to address with dissertation research. For example, the problem “terrorism kills thousands of people each year” is probably not specific enough in terms of who gets killed by which terrorists, to work for a doctorate candidate; or “Social media use among call-center employees may be problematic because it could reduce productivity,” which contains speculations about the magnitude of the problem and the possible negative effects.

Evidence-based here means that the problem is well-documented by recent research findings and/or statistics from credible sources. Anecdotal evidence does not qualify in this regard. Quantitative evidence is generally preferred over qualitative ditto when establishing a problem because quantitative evidence (from a credible source) usually reflects generalizable facts, whereas qualitative evidence in the form of research conclusions tend to only apply to the study sample and may not be generalizable to a larger population. Example of a problem that isn’t evidence-based: “Based on the researcher’s experience, the problem is that people don’t accept female leaders;” which is an opinion-based statement based on personal (anecdotal) experience.

Real-life means that a problem exists regardless of whether research is conducted or not. This means that “lack of knowledge” or “lack of research” cannot be used as the problem for a dissertation study because it’s an academic issue or a gap; and not a real-life problem experienced by people or organizations. Example of a problem that doesn’t exist in real life: “There is not enough research on the reasons why people distrust minority healthcare workers.” This type of statement also reveals the assumption that people actually do mistrust minority healthcare workers; something that needs to be supported by actual, credible evidence to potentially work as an underlying research problem.

What are consequences?

Consequences are negative implications experienced by a group of people or organizations, as a result of the problem. The negative effects should be of a certain magnitude to warrant research. For example, if fewer than 1% of the stakeholders experience a negative consequence of a problem and that consequence only constitutes a minor inconvenience, research is probably not warranted. Negative consequences that can be measured weigh stronger than those that cannot be put on some kind of scale.

In the example above, a significant negative consequence is that women face much larger barriers than men when attempting to get promoted to executive jobs; or are 94% less likely than men to get to that level in Corporate America.

What is a gap?