- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory

- About the Public Management Research Association

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Advance articles

A new measure of us public agency policy discretion.

- View article

Adapting to Organizational Change in a Public Sector High-Reliability Context: The Role of Negative Affect and Normative Commitment to Change

- Supplementary data

Agency consultation networks in environmental impact assessment

All hands on deck: the role of collaborative platforms and lead organizations in achieving environmental goals, assessing drivers of sustained engagement in collaborative governance arrangements, preference for group-based social hierarchy and the reluctance to accept women as equals in law enforcement, does administrative burden create racialized policy feedback how losing access to public benefits impacts beliefs about government, shifts in local governments’ corporatization intensity: evidence from german cities, critical mass condition of majority bureaucratic behavioral change in representative bureaucracy: a theoretical clarification and a nonparametric exploration, role distance. an ethnographic study on how street-level managers cope, types of administrative burden reduction strategies: who, what, and how, email alerts.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1477-9803

- Print ISSN 1053-1858

- Copyright © 2024 Public Management Research Association

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Logics and Agency in Public Management Research

Tony kinder.

1 Administrative Science, Tampere University, Tampere, Finland

Jari Stenvall

Antti talonen.

2 Faculty of Law, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland

The article analyses the negative effects of the use of logics in public organisation research on active human agency. We build up a new conceptual model with which to approach logics in current research on organising public services; suggesting ways in which current models using logics in public organisation research can be strengthened. Our contribution is two-fold: we argue that Elder-Vass’ approach benefits from close synthesis with social learning theory (including recent thinking on trust, emotions, and distributed learning) and secondly, that grounding all usage of logics in logic-of-practice helps avoid a reification of logics and thirdly that situated learning better suits public organisation problem solving that the application of ‘new’ universal solutions.

Introduction

A set of POR papers analysing COVID-19 responses, take as part of their explanatory tool kit how logics influences people and events. Christensen ( 2021 ) contrasts the logics flowing from March and Olsen’s ( 1983 ) homogeneous leadership, with those based on Selznick’s ( 1957 ) notion of homogeneous groups resulting in a situated logic of negotiation and compromise. Mattei and Vigevano’s ( 2021 ) analysis of the Italian COVID response interrelating national and local bodies, identifies a logic of underlaying policy integration cooperation that enhanced effectiveness. Mozumder ( 2021 ) suggests that the logic of learning from practice was made difficult in the UK because of diminished trust in agents and institutions.

Our paper picks up this issue of logics in how public organisations react to events. This is important as public managers increasingly focus on organising processes rather than organisational imperative: an essential change when most major policy responses now call for partnership, networks and/or ecosystem cooperation and integration. Situated and customised responses to events, taking advantage of available strengths and opportunities are perhaps particularly important, where user/client/customer feedback points to ways, as Normann ( 2002 ) notes, in which services can be improved. Our focus is on the potential conflict between the logics inherent in organisational form or organising in relation to the preferences of users and managers based on situated and social learning. Bourdieu (1984) and Bernstein ( 2000 ) emphasised how conduct of conduct rules (governance) are influenced by ‘soft’ socio-cultural practice, which they in turn reproduce and reshape. Faced with volatile and rapidly altering service environments, street-level decisions (Lipsky, 1980 ) can become patterned into ‘pop-up” governance-as-legitimacy (Laclau 1990).

Research about public organisations increasingly references logics: isomorphic logic (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983 ); public service logic (Ngoye et al., 2019 ; Osborne, 2017 ); management decision logics (Thornton et al., 2015 ) [ framing of public institutions and rules of the game logics (Scott, 2008 ); network management logics (Kooiman, 2003 ); and service-dominant logic (Lusch & Vargo, 2014 , cf. Lopes & Alves, 2020 ). Bourdieu’s (1984) logic-of-practice is intended to ground logics in practice.

Logics is now a prominent idea in research on organisation from post-structural and socio-cultural process perspectives. March and Olsen ( 1989 ) for example, argued that logic of appropriateness has limited scope giving way to logic of consequences , apportioned by a hierarchy of logics. For social scientists seeking to generalise research results positing logics is an opportunity, provided as Kinder (2000) argues, they are recontextualised. Where logics are not re-grounded there is danger of assuming the future is dictated by yesterday, discounting human intervention. Determinism of this sort is a major issue in social research. Few social theorists now aim to ‘discover’ the ‘iron’ laws of society beloved by nineteenth century theorists. Logics properly applied are mediated by cognitive, emotional, (possibly) trusting people and especially so in services for people. As Jacobsen ( 2021 ) shows, in partnerships between the public and private sectors admixtures of potentially competing logics can be hybridised or combined to achieve public value.

Important thinkers criticise using logics from the perspective of diminishing agency include Wittgenstein ( 2001 ), Arendt ( 1951 ) and Chomsky ( 1969 ). Others highlight problems in agents choosing between multiple logics (Berman, 2012 ), or conflicting logics (Lounsbury, 2007 ), or over-reliance on logics to predict solutions (Dewey ( 1938 ), leading Archer ( 2000 ) and Toulmin ( 2003a , 2003b ) for example to call for more research on the use of logics and contingency in social research.

Elder-Vass ( 2010 ) suggests a synthesis between Bourdieu’s ( 1990 ) idea of habitus as structuring thinking with Archer’s ( 2000 ) idea of inner conversations reflecting on choices in context. We find this synthesis inadequate for PM research since it unsatisfactorily addresses the complexity people face in public services and the nature of the learning processes they undertake, implying a clear view of how situated learning occurs and is used. Our research question is: are there negative effects of the use of logics in public organisation research on active human agency?

Our contribution is two-fold: we argue that Elder-Vass’ approach benefits from close synthesis with social learning theory (including recent thinking on trust, emotions, and distributed learning) and secondly, that grounding all usage of logics in logic-of-practice helps avoid a reification of logics. In pursuing these arguments, we build up a new conceptual model with which to approach logics in current research on organising in the public sector; suggesting ways in which frameworks using logics in can be strengthened.

The paper proceeds by exploring and defining the meaning of logics. Illustrating how the use of logics has become important in public organisation theory, one example being Bright’s ( 2021 ) recent use of Klijn et al. , ( 2016 ) bureaucratic logic to analyse how organisational identity interrelates with motivation. We argue that logics are only valid when grounded in situated experience from logic-of-practice in a particular service setting. Since contexts and cultures differ, it cannot be assumed that logics applicable in one setting are appropriate to another. We give a short exposition of how active agents in a particular setting learn logics and apply them using Vygotsky’s social learning theory. We then consider how logics are currently deployed in public organisation research taking the example of Vargo and Lusch’s ( 2008 ) service-dominant logic and Klijn et al., ( 2016 ) and Kooiman’s ( 2003 ) network management. We show that in both cases logics are regarded as universals; there is an absence of active human agency in both cases. From this we argue for a review of how logics and active agency and currently used in public organisation research citing logics.

Logics: Genealogy and Use

Thornton and Ocasio ( 1999 :804) define institutional logics as the socially constructed, historical patterns of material practices, assumptions, values, beliefs, and rules by which individuals produce and reproduce their material subsistence, organize time and space, and provide meaning to their social reality . Linking individual cognition to social structures they Thornton and Ocasio ( 2017 ) trace the idea to Selznick ( 1948 ) and later Zucker ( 1983 ), noting that Olson’s ( 1970 ) collective action emphasised individual consciousness and Fleck ( 1979 ) the notion of thought style as micro-social conditioning.

Douglas ( 1987 :63) argued that organisations produce and reproduce sameness by embedding knowledge and when organisations interact, (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983 ) isomorphic logic diffused sameness, even according to Friedland and Alford ( 1991 ) across governances and between Governments. Wary of imitating symbolisms, Jackall ( 1988 ) argues imitating practice is more important; importantly suggesting the embedded agency is more important than imitative structures. Jackall’s framing of enablers and constraints continues to be cited though less is paid to the idea that only logics based on practice evidence have value.

Evidencing logics remains contentious for Toulmin ( 2003a :213) who says, Warm hearts allied with cool heads seek a middle way between the extremes of abstract theory and personal impulse , a wariness of deduced logics shared by Arendt ( 1958 ) who worries about thoughtlessness ( 1958 :62) displacing empirical inquiry. Her emphasis on active agency (discussed below), including socially generated trust, is echoed by Popper ( 2007 ) who distrusts any logic not empirically founded.

Processes creating logics are subject to close scrutiny. For example, Van Benthem and Pacuit’s ( 2010 ) idea of temporal logics captures the point that logic in one time-frame may be non-logical in another. Epstein ( 1995 ) points to people internalising multiple logics and researchers need to justify their choices arguing that splitting and splicing of logics by agents are often unconscious. Kahneman and Tversky ( 1982 ) would agree, noting that slower (rational) selection of logics is post-facto justification of emotional preferences. Janik and Toulmin ( 1996 ) fear that transferring logics between locations is problematic.

Learning and Logics

The idea of logics is widespread in public organisation research in justifying interpretations and actions as the recent POR articiles demonstrate. Dunn and Jones ( 2010 ) argue that following the introduction of new public management (NPM), Doctors adopt a new array of logics, including management heuristics and processes. Suggesting Finnish Doctors are more accepting than their Norwegian colleagues of NPM, Berg et al. ( 2017 ) suggest this due to identity change. Also investigating Doctors and NPM, Berg et al. ( 2017 ) argue that identity change is more profound amongst Norwegian than Finnish Doctors, since the former have less acceptance of NPM logics. It is now common-place for researchers to follow Scott ( 2008 ) and speak of logics in and between organisations or follow Freidson ( 2001 ) and comment on changing logics within professions without citing grounded empirical evidence. Bjerregaard ( 2011 :195) argues that organisational logics are derived from institutional logics, giving a hierarchical authority of logics: these hierarchies of logics he says are somehow learned and accepted as justifying actions.

This short review supports our argument that new research into the use of logics in public organisation research is needed. Bourdieu ( 1990 ) and Zacka ( 2017 ) would support this conclusion; they draw attention to logic-of-practice – active learning by agents of patterned behaviour in contrast to the Habermasian deduction of logics from theory and their generalised usage. Bourdieu uses logic-of-practice to explain stability and change: practice-based habituations and frameworks and metaphors for thinking. Bourdieu’s logic-of-practice grounds logics in situated practice, not to be confused with Gidden’s ( 1984 ) use of the term for whom logic-of-practice results in new social structures.

We conclude that conceptual development in public organisation theory often features the idea of logics: isomorphic logic, public service logic, logics in management decision taking, logics in framing the rules of the game , logic in the management of networks, service-dominant logic. How conceptually robust, grounded and evidentially-situated are these logics in public organisation research? How do different logics relate to one another? We turn now to look further inside logics from the perspective of human agency.

Agent-Centred Social Theory

Problematising logics in public organisation research and highlighting Bourdieu’s point that logics are learned, draws attention to active human agency as learners. Agency too is a contested idea: are cognition and intent essential characteristics, (b) what constitutes collective agency and (c) is agency contingent on context? Our perspective is that agency necessarily involves cognitive intent, and this precludes non-human ‘actants’ from agency, though in the special sense of distributed learning, collectives of people may be said metaphorically to possess agency.

Following Elder-Vass’s ( 2010 ) we agree that Archer’s ( 2003 ) internal conversation shaping agency and Bourdieu’s (1984) idea of habitus influencing agency are reconciled by the idea of emergence from complexity theory. This aligns with Morin’s ( 1959 , 1982 , 1986 ) contribution to active agency in French social theory, which can be underestimated; he spoke of recursive causality , in similar terms to Whitehead’s ( 1929 ) being and becoming : social order both creates and is created by active human agency.

Agentic acting with intent suggests intention-to-act (future) and intention-in-action (current activity). Intention therefore introduces psychological deliberation into agency, often as Elster ( 1979 ) notes from pre-commitment to particular goals citing ends-means coherence. Intention seeks control over future outcomes resulting from present behaviour; it is volition to act as Bratman (1987; 1991) says, based on cognitive reflection and/or beliefs, what Dewey calls reflective intelligence .

Since individuals are continually interpreting and responding to events and the activities of other agents, this catalyses new flows of conduct (Giddens, 1979 :55) that continually emerge making human cognitive agency the micro-foundation of social research. Individual cognition and learning is then central to active agency, this the opposite of structural theory (Parsons, Althusser) which accords agency to non-cognitive structures such as bureaucracy and organisation. Similarly, we reject actor-network approaches (Latour, 1992 ), that attribute agency to non-human actants.

We employ Vygotsky’s ( 1986 ) social learning approach in which learning is social; featuring cognitions, relationality and emotions (especially trust); these mediate learning through the individual’s context and culture. Language, frameworks, concepts, social morès and norms influence learning. As Wertsch et al. ( 1995 :25) says, we can never speak from nowhere . Learning cannot be reduced to bio-deterministic synaptic processing. Bernstein ( 2000 ) blends agent-centred and social learning approaches to explaining social change (see Hasan, 2001 , 2005 . He argues that restricted and elaborated codes of interpretation are the result of interaction between active agents’ identity and inherited cultural meanings. New social constructions, emergences that may constitute logics, can be weak or strong for Elder-Vass, yet always—as Arthur’s (2015) complexity theory suggests—arise from non-linear thinking and active processes with unforeseen results, the result of emotional attachments. Social learning aligns closely with Bourdieu’s logic-of-practice: concrete experiences and their interpretation by cognitive human agents, balance stability (morphostasis) and change (morphogenesis). Sense-making (which includes possible logics) are always provisional and transitory, since social life is always dynamically responding to the actions and ideas of other people and external events. Agentic intent then is ontologically founded on social learning, which is always relational and in arenas of complexity, continuous; context mediates without deterministically shaping learning and intent.

Context and Active Agency

Cognitive human agents have both the capability to act and the capacity for cognition. Capability allows intent to result in social effects; those intended or not (Hvinden et al. 2018 ). Distinctive human agency (Ci 2011) is power, since intentions always subjectively mobilises bias (Schattschneider, 1975a , 1975b ). All agents operate in domains in which this subjective power is recognised as plausible (or not); contexts therefore give content (intention) and modality to agency. As Kiser ( 1999 ) argues this makes agents and their context inseparable. “Logic” becomes an accumulation of behaviour at an individual level from which the individual learns; it is not a superstructural imposition.

Agency is relational, enlivened only in social processes (Burkitt, 2016 ). It is in Whitehead’s ( 1929 ) terms becoming , not being : an emergence that is coproduced (Weber, 2006 ). The interactivity of agents creates intent not something inherent in objects (Dépelteau 2010 ). This perspective closely aligns with relational sociology, which focuses on processual relationships (Emirbayer and Mishe 1998; Daniels, 2001 ). Unlike Vandenberghe (2010), who suggests human agents can operate without prior intent, we follow Gergen (2009 and Archer (2012; 2013) who insist that agency presumes reflexivity, which by iterational morphogenesis explains how agents both produce and reproduce social structures. Social structures are important Elder-Vass ( 2010 ) argues not because they dictate logics, but rather because they mediate learning, which may become logics: social structures cannot act independently of human intent.

Elder-Vass ( 2010 , 2007a , 2007b ) points out that although at first sight (a) Archer’s ( 2003 ) emphasis on reflexivity ( internal conversation ) shaping agency (and creating personal and social identity), and (b) Bourdieu’s (1984) accent on habitus as socially conditioning (generative capacity to produce, reproduce, change), appear irreconcilable, the idea of emergence (from complexity theory) reconciles the two approaches. Agency itself is always emergent, always becoming . Welcoming these ideas, our view is that further steps are needed to explore how the social learning processes occur the give rise to and interpret emergences, leading us towards Vygotskian social learning.

Collective Agency?

What then of collective agency, such as Marx’s ( 1852 ) class for itself or collective unlearning in public organisations (Stenvall et al., 2018 ), or corporate responsibility? Law often ascribes moral responsibility to corporate bodies. However, the agency of collective bodies (state, working-class, companies) is quite different from individual agency, which presumes cognitive ability and as Arendt ( 1969 ) argued, collective actions cannot abrogate the inalienable culpability for their actions. Nor can agency be confused or conflated with finance principal-agency theory, which often ignores context and presumes rational choice (Becker, Williamson). For Perrow ( 1990 :121) this approach is not only wrong but also dangerous . Since agency presumes learners and intent, collective agency such as learning organisations are illusory – organisations cannot learn, since only individual cognisant individuals can think.

Grounded logics are the human/social construction working on nature and in social relationships, the dialectical logics Marx developed in Capital ( 1993 ), applied historically ( 1852 ) and justified philosophically ( 1976 ), grounded in his theory of capitalism ( 1973 ) and which Engels (1859) related to dialectics of nature. Whereas some social theorists (Schatzki 2019 being an example) sayings and doings shape social change, Marx ( 1973 ) that it is not ideals (ideas ungrounded in material practice) that drive social change. Instead, humans being the only animal capable of advanced cognition, including intentionality (design) and purposive labour enhancing the productivity of nature, we use self-consciousness to create social consciousness. Shared with others and becoming collective intentionality and consciousness, social change results. Humans are capable of thought-through collective agency. It is from patterns of agency that new logics are created and in turn, individual cognitions and collective intent make use of previously formulated logics. Logics then are actively constructed, quite unlike abstracted ideas such as Kant’s imperative or Smith invisible hand.

Whereas individual consciousness is the result of cognition and affect (Vygotsky, 1986 ), collective consciousness is embedded from external sources. Blackmore’s ( 2003 ) memes and Durkheim’s ( 1893 ) analysis of religious show this occurring in wider society. In organisations and organising however, Wittgenstein’s follow the rules is replaced by follow the leader , since as Schattschneider ( 1975a , 1975b :71) says, organisations are the mobilisation of bias they necessarily privilege certain outcomes. Collectivities of people in organisations instead of following an ideology, and ideal in Ilyenkov’s ( 2008 ) terms, require a dynamic narrative connecting problem and solution, creating organic solidarity: collective consciousness in organisations is necessarily highly situated and, where leadership is effective, is guided towards understanding the germ-cell or essence of the problem, recognising contradictions in the current state-of-affairs, and takes collective active to achieve what the leader has explained as a preferred solution (Prilleltensky ( 1997 :525). Individuals still must make sense of the leader’s narrative; often this is helped by framing, frameworks, metaphors and language supplied by the leader. Part of the leader’s role in ecosystems is legitimising the other agents in the ecosystem, with whom the organisation’s members must work in order to deliver the preferred solution. For Blunden ( 2015 ) effective project work in organisations relies on leadership building this collective consciousness. Such leaders will combine vision with the leadership, management and administrative competences to which Hartley and Allison ( 2000 ) refer. Creating collective consciousness in a public or other organisation, requires a leader able to make sense of problem–solution in context and culture and to marshal the collective into activity.

One of the more contentious results of what Bernstein ( 2000 ) terms the cultural turn in social theory, is the attribution of agency to culture. As Harvey ( 1982 ) and others make clear, scaling between levels of analysis only makes sense if not employed as a deterministic hierarchy of simplified causalities from the general to the particular.

Socio-Cultural Theory

Learning and deploying new knowledge is then an essential aspect of active agency: learning patterns of activity from logic-of-practice creates new bottom-up governances and learning from user feedback helps personalise the design and delivery of local public services. How then does this occur? Figure 1 is a simplified exposition of how social learning occurs using Vygotsky’s ( 1986 ; 1997) perspective and drawing on the work of Engeström et al., ( 1999 ), Nardi ( 1996 ) and Illeris ( 2004 ). Individual thinking is shaped by logics and in distribution new logics are formulated, in turn influenced by context and culture. Arrows 1, 2 and 3 indicate these interactions constituting the activity centre in the middle of Fig. 1 illustrating how logics influences learning and in turn by learning and patterned practice, new logics are created. A key point is the sense-making by cognitive individuals references their emotional attachments both to old ways-of-working and to a vision of how new services and governances might operate drawing on heuristics (thinking frameworks) evolved from formal education and in practice. As Vygotsky ( 1986 :282) says, [Thought] is not born of other thoughts. Thought has its origins in the motivating sphere of consciousness, a sphere that includes our inclinations and needs, our interests and impulses, and our affect and emotions Figs. 2 3 .

Simplified Vygotskian social learning framework (derived from Illeris, 2004 ; Engeström ( 1996 , 1996 ) and Nardi ( 1996 )

Individual learning (top-left) is distributed during organising service delivery (top-right). All learning occurs in a specific context (bottom-left) meaning ‘hard’ rules and norms such as budgets, regulations, ethical standards and (bottom-right) ‘soft’ cultural norms such as general social culture, occupational culture. While taking account of ‘objective’ facts, the individual learning is non-rational.

Trust is an especially important emotion in individual learning and its distribution for PM since the services target vulnerable people reliant on trust and trust accompanies representatives between sets of professionals. As Weibel and Six ( 2013 ) argue, this willing acceptance of vulnerability between agents in turn presupposes relatedness between agents, competence and autonomy. Trust and control are in once sense opposites and in another complementary. More trust in a service system means less need for formal management structures and oversight accountability. When trouble occurs Six (2005) notes, trust is either dissipated or strengthened.

Social learning then is relational and offers a way of improving Elder-Vass’s position by explaining how agent learning reframes and reformulates logics in situated theorisations of public service dynamics.

Logics in Public Service Organisation Research

Taking two oft-cited uses of logics in public organisation research as examples, here we consider how far they are grounded in learning by active agents.

We have chosen (a) Vargo and Lusch’s ( 2004 , 2007 , 2008 and 2017 ) service-dominant logic and (b) Kooiman ( 2003 ); and Klijn and Koppenjan’s ( 2014 ) management of networks. We choose Vargo and Lusch and Kooiman and Klijn because they will be familiar to readers, and each apply logics at the level of organisations delivering services. The choices are for illustrative purposes; we are not in any way suggesting that these pieces of research are other than valuable. In each case, we present a table of how logics are referenced in these two bodies of research relative to social learning by active agent in logic-of-practice.

Service-Dominant Logic and Logic Evaluation

Vargo and Lusch ( 2004 , 2007 , 2008 , 2017 ) offer an integrated marketing perspective on services, arguing that value (in use) is co-created by service providers and users; focusing on private services little mention is made of public services. They argue that a goods-dominant logic (GDL, featuring tangible goods, a supply-side mindset and objective success criteria) is being superseded by a SDL, which concentrates on intangible services, a customer-focused mindset and subjective success criteria: goods are a distribution mechanism for services. Our focus here is on the use Vargo and Lusch make of logics and the extent to which the logics are grounded in practice and agent learning.

Using Lusch and Vargo ( 2014 ), a 224-page exposition of SDL, Table Table1 1 summarises the stance taken in relations to factors constituting grounded logics. In this welcome exhortation to adopt customer-focused activity, non-exchange (public and some 3S) people and public organisations are seldom mentioned. New service dominant logics arise in abstract exchange relationships. Few individual service providers or people are mentioned; the logics are derived from market exchange. SDL is presented as a new paradigm evolving from firms’ exchange activity, without any reference to the people constituting the firms. For example, new knowledge arises from exchange, without mention of learning, cognition, affectations. The SDL world is populated by firms exchanging services with other firms and customers, none of which reference in any detailed way the context and culture in which the exchanges occur. SDL is a switch from GDL the processes of which do not feature human agentic involvement.

Logics in service-dominant logic (page references from Lusch and Vargo 2014 )

Our point is this: while Lusch and Vargo refer often to being actor-centric, there are few people in their exposition of logics and almost no public sector. The logics arise from market exchange between economic units (firms) within ecosystems and institutions envisaged from a market exchange perspective. There is no human thinking, feeling, or (human) relations agency. Agency is ascribed to inanimate entities: abstracted customers and firms. Although the services ecosystems self-adjust, they appear to do so without human decisions, responses, creativities. The only practice referenced are those of resource integration and market exchange; not real people, using real services. No competitive or conflicting logics exist, apart from GDL. This new SDL paradigm exists without reference to particular and situated contexts and cultures. SDL is a metaphysic, a belief system not grounded in practice or reality, not subject to verification or disproof. The logic is without reference to human intervention and can only be categorised as deterministic.

Network of Management Governances and Logic Evaluation

Kooiman’s 249-page exposition ( 2003 ) and later work including Klijn ( 2008 ) and Klijn and Koppenjan ( 2014 ) presents a logic for governance analysis based on management of networks, used in a 427-page study of fisheries governance ( 2005 ). Kooiman and Bavink, ( 2013 ) sets out to explain how interdependency and relationships between agencies can best operate as society becomes more complex, dynamic and diverse. Table Table2 2 summarises the stance taken by network management theorists towards grounding logics in practice and learning.

Logics network management of governances

taken from Kooiman ( 2003 ); Klijn ( 2008 ) and Klijn and Koppenjan ( 2014 )

For Kooiman networks are the preferred structure to solve problems and a Central-Controller led governance manages the network. Central Controllers, usually Government, bring resources to problem-solving; networks are characterised by rational-cognitive agency and reference formal knowledge in decision taking. NPM efficiency is a desirable goal of the networks. Networks form governance hierarchies with first-order governance (day-to-day), institutional arrangements (second order) and (third order) meta-governance (similar to Habermas’ communicative rationality. Network governance is appropriate to policy networking, inter-organisational delivery of service and policy implementation: it is not confined to second-order policy making. The logic in network management then is compliance with the preferences of the Central Controller; often the targets and processes associated with new public management.

To assess the implications of Table Table2 2 in steps. Kooiman and his colleagues argue that governances are best analysed and constructed as networks, that networks are best centrally directed, network participants ought to act and think rationally, the possessing resources (power) gives legitimacy to network central directors and that these logics apply whatever the context and culture.

Network management as a logic is not grounded in active agency; it is not derived from lessons learned by cognitive-emotional humans. The approach appears to be a quirky ideal type justifying the adopting of new public management and legitimating the power of central Government in public service design and delivery.

Discussion and Conclusions

Tables Tables1 1 and and2 2 illustrate little evidence of learning by active agents and little evidence of grounding their prescribed logics in practice. Why is this absence of social learning in SDL and the Rotterdam group’s network management approach important? The answer is that social research bereft of cognisant people is questionable: the social constructions resulting from such research are from inside the mind of the researchers not logic-of-practice.

It is of course possible to argue that logics are an implicit or sub-conscious aspect of agent behaviour. None of the theorists mentioned take this position. Assuming an unverifiable set of beliefs would open new methodological cans of worms. Does this invalidate the approaches suggested by SDL and network management? Not necessarily, however, it makes it important to know the epistemic stance of the researchers.

Both Lusch and Vargo and Kooiman and his colleagues are suggesting that there are alternative mindsets to (for example) market transactionality (price) or hierarchy (power). Both sets of researchers are proposing new principles to guide thinking and action. Our central point is that each offer a play without actors, a world without people; principles decided deductively not grounded, ways of operating where the key units of analysis are not cognitive-emotional persons, but instead firms/exchanges (SDL) or organisations in networks.

Both SDL and network management are logics oft cited in public organisation research. Llewelyn ( 2003 ) argued that there are five types of theorising available to qualitative researchers: (a) metaphors; (b) differentiation; (c) conceptualisation; (d) context-bound theorising of settings and (e) context-free ‘grand’ theorizing. Both SDL and network management are context-free theorising: meta-narratives, in each case produced from deep conceptual reflection on enduring social relationships and causalities of how structures and agency interact. The fact that such theorisations are not derived from empirically substantiated agent learning that grounds logics in practice, does not in itself deprive them of usefulness.

Nonetheless, deduced theorisation should be acknowledged, and the assumptions laid bare; so that when applied to particular types of human agency or situated contexts and cultures, it is clear what evidence from structures and agency are appropriate for researchers using these approaches to seek. If there are contexts and cultures to which SDL and network management do not apply, then this too should be acknowledged to avoid using the approaches to inappropriately frame research problems and/or embed assumptions in empirical work unknowingly. This is especially important for public organisation research which is international in nature, transgressive of contexts and cultures and needs to know if conceptual tools are proposed as universally applicable or if of limited generalisability, the nature of the limitations. Our own view is that the logics in SDL is a metaphysic and network management epistemologically flawed, given its assumptions of rationality and privileging of power. Neither approach is universally applicable—contexts and cultures vary considerably.

General theories are stronger on explanation (attributed causality, i.e. why) and weaker on understanding (i.e. what—identifying the existence of outcomes predicted by the theory); since social research phenomena are constructions. This can lead to confusing the map with the terrain i.e. finding what one sets out looking for, making theory falsification impossible. This of course is the great advantage of grounding social research by investigating agent interpretations and actions: instead of beginning with a theory and seeking evidence of its usefulness. As Glaser and Strauss ( 1967 :2) propose grounded theory discovers theory from systematic data. Groundedness itself being a metaphor for linking to a feedback loop, such as ethnographic studies or qualitative interviews producing case studies. For Archer ( 2000 ) grasping both agency and structures is essential to explaining social activity: neither SDL nor network management do this.

We conclude that some researchers continue to find Lusch and Vargo’s SDL and Kooiman’s network management logics, or theories, useful. Their use however should be constrained by a clear understanding of how the key concepts relate to the particular context and culture being studied. Further, researchers should note that in focus on logics comes at the cost of not focusing on human agency – a controversial choice in public management research. As Fig. 1 illustrates use of logics is not passive, from using logics new logics emerge addressing contradictions and conflicts in the previous patterns of logics, as they apply to current problems.

For public organisation managers the clear implication of this research is to avoid off-the-shelf, transformative, paradigm-switching new tools. There is no alternative but deeply investigating problems in situation, digging to identify the germ-cell essence of any problem and to propose solutions accordingly. Public manager should always to wary of universal tools or solutions and instead be unafraid to conclude that their organisation, their problem requires tools of analysis and solutions uniquely suiting their organisation and its capabilities. Our contribution revolves around viewing logics not as passive ‘ideas’ isolated from practice, but instead as ‘actively’ helping to socially construct what current practice is and thereby create new logics. In short, logics occupy a dialectical place in learning and problem solving and are not static nor fixed.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Tony Kinder, Email: [email protected] .

Jari Stenvall, Email: [email protected] .

Antti Talonen, Email: [email protected] .

- Archer M. Structure, agency and the internal conversation. CUP; 2003. [ Google Scholar ]

- Archer MS. Being human – the problem of agency. CUP; 2000. [ Google Scholar ]

- Arendt H. The origins of totalitarianism. Harvest Books; 1951. [ Google Scholar ]

- Arendt H. The human condition. The University of Chicago Press; 1958. [ Google Scholar ]

- Arendt H. On violence. Harvest/HBJ; 1969. [ Google Scholar ]

- Berg LN, Puusa A, Pulkkinen K, Geschwind L. Managers’ identities: Solid or affected by changes in institutional logics and organisational amendments? Scandinavian Journal of Public Administration. 2017; 21 (1):81–101. [ Google Scholar ]

- Berman EP. Explaining the move toward the market in US academic science: How institutional logics can change without institutional entrepreneurs. Theory and Society. 2012; 41 (3):261–299. doi: 10.1007/s11186-012-9167-7. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bernstein, B. (2000). Pedagogy, symbolic control and identity: Theory, research critique, Rowman and Littlefield, Lanham.

- Bjerregaard T. Co-existing institutional logics and agency among top-level public servants: A praxeological approach. Journal of Management & Organisation. 2011; 17 (2):194–209. doi: 10.5172/jmo.2011.17.2.194. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Blackmore S. Consciousness: An Introduction. Hodder & Stoughton; 2003. [ Google Scholar ]

- Blunden A, editor. Collaborative Projects – An Interdisciplinary Study. Haymarket; 2015. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bourdieu P. The Logic of Practice. Polity Press; 1990. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bright, L. (2021). Why does PSM lead to higher work stress? Exploring the Role that Organizational Identity Theory has on the Relationship between Public Service Motivation and External-Related Stress among Federal Government Employees , Public Organization Review, 10.1007/s11115-021-00546-0

- Burkitt, I. (2016). Relational agency: Relational sociology, agency and interaction. European Journal of Social Theory, 19 (3), 322–339.

- Chomsky N. Objectivity and liberal scholarship , in American Power and the New Mandarins. Penguin; 1969. [ Google Scholar ]

- Christensen T. The social policy response to COVID-19 – the failure to help vulnerable children and elderly people. Public Organization Review. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s11115-021-00560-2. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Daniels, H. (2001). Vygotsky and pedagogy, Routledge-Falmer, Abingdon.

- Dépelteau, F. (2010). Relational thinking in sociology: Relevance, concurrence and dissonance , in Hyman, J., & Steward, H. (2010). Agency and Action, CUP, Cambridge.

- Dewey J. Logic: The theory of inquiry. Holt; 1938. [ Google Scholar ]

- DiMaggio PJ, Powell WW. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review. 1983; 48 :147–160. doi: 10.2307/2095101. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Douglas M. How Institutions Think. Routledge & Kegan Paul; 1987. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dunn MB, Jones C. Institutional logics and institutional pluralism: The contestation of care and science logics in medical education. Administrative Science Quarterly. 2010; 55 (1):114–149. doi: 10.2189/asqu.2010.55.1.114. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Durkheim E. 1984. The Division of Labour in Society; 1893. [ Google Scholar ]

- Elder-Vass D. Social structure and social relations. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour. 2007; 37 (4):466–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5914.2007.00346.x. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Elder-Vass D. Reconciling Archer and Bourdieu in an Emergentist Theory of Action. Sociological Theory. 2007; 25 (4):325–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9558.2007.00312.x. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Elder-Vass D. The Causal Power of Social Structures. CUP; 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Elster, Jon (ed) (1979). Ulysses and the Sirens: Studies in Rationality and Irrationality. Editions De La Maison des Sciences De L'Homme.

- Engeström, Y. (1996). Developmental studies of work as a test bench of activity theory: the case of primary care medical practice, Chaiklin, S. and Lave, J. (Eds.), (1996) Understanding practice: perspectives on activity and context, CUP, Cambridge, Ch. 3.

- Engeström Y, Miettinen R, Punamaki RL. Perspectives on activity theory. CUP; 1999. [ Google Scholar ]

- Epstein R. The semantic foundations of logic. Oxford University Press; 1995. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fleck L. The genesis and development of scientific fact. University of Chicago Press; 1979. [ Google Scholar ]

- Freidson E. Professionalism: The third logic. Polity Press; 2001. [ Google Scholar ]

- Friedland, R., & Alford, R. R. (1991). ‘Bringing society back in: symbols, practices, and institutionalcontradictions’. In Powell, W. W. & DiMaggio, P. J. (Eds), The New Institutionalism in OrganizationalAnalysis. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 232–66.

- Giddens, A. (1979). Central problems in social theory: Action, structure and contradiction in social analysis, University of California Press, CA.

- Giddens A. The constitution of society. CUP; 1984. [ Google Scholar ]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory. Aldine Publishing; 1967. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hartley J, Allison M. The role of leadership in modernisation and improvement of public service. Public Money and Management. 2000; 20 (2):35–40. doi: 10.1111/1467-9302.00209. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Harvey D. The limits to capital. Chicago University Press; 1982. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hasan R. Understanding Talk: Directions from Bernstein’s Sociology. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2001; 4 (1):5–9. doi: 10.1080/13645570010028549. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hasan, R. (2005). Semiotic mediation, language and society: three exotripic theories: Vygotsky, Halliday and Bernstein, in Webster JJ (Ed.), Language, society and consciousness, Equinox, London.

- Hvinden B, Halvorsen R. Mediating Agency and Structure in Sociology: What Role for Conversion Factors? Critical Sociology. 2018; 44 (6):865–881. doi: 10.1177/0896920516684541. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Illeris K. Learning in working life. Roskilde University Press; 2004. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ilyenkov EV. Dialectical logic – Essays on its history and theory. Aakar Books; 2008. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jackall R. Moral mazes: The world of corporate managers. Oxford University Press; 1988. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jacobsen, D. I. (2021). Motivational differences? Comparing private, public and hybrid organizations. Public Organization Review, 21 (3), 561–575.

- Janik A, Toulmin S. Wittgenstein’s Vienna. Elephant Paperback; 1996. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1982). Judgement under uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases, CUP, Cambridge. [ PubMed ]

- Kiser E. Comparing varieties of agency theory in economics, political science and sociology: An illustration from state policy implementation. Sociological Theory. 1999; 17 (2):146–170. doi: 10.1111/0735-2751.00073. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Klijn EH. Complexity theory and public administration: What's new? Public Management Review. 2008; 10 (3):299–317. doi: 10.1080/14719030802002675. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Klijn EH, Koppenjan JFM. Complexity in governance network theory. Complexity, Governance & Networks. 2014; 1 (1):61–70. doi: 10.7564/14-CGN8. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Klijn, E. H., Sierra, V., Ysa, T., Berman, E., Edelenbos, J., & Chen, D. Y. (2016). The influence of trust on network performance in Taiwan, Spain, and the Netherlands: A cross-country comparison. International Public Management Journal, 19 (1), 111–139.

- Kooiman J. Governing as governance. Sage; 2003. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kooiman, J., & Bavinck, M. (2013). Theorizing governability–The interactive governance perspective. In Governability of fisheries and aquaculture (pp. 9–30). Springer, Dordrecht.

- Kooiman J, Bavvinck M, Jentoft S, Pullin R. Fish for life: Interactive governance for fisheries. Amsterdam University Press; 2005. [ Google Scholar ]

- Latour, B. (1992). “Where are the missing masses? The sociology of a few mundane artefacts,” in Bijker WE & Law J (Eds.), (1992). Shaping Technology/Building Society, MIT, London, pg. 225 - 258.

- Lipsky M. Street-level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the individual in Public Services. Sage; 1980. [ Google Scholar ]

- Llewelyn S. What counts as theory in qualitative management and accounting research? Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal. 2003; 16 (4):662–708. doi: 10.1108/09513570310492344. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lopes, T. S. A., & Alves, H. (2020). Coproduction and cocreation in public care services: a systematic review. International Journal of Public Sector Management .

- Lounsbury M. A tale of two cities: Competing logics and practice variation in the profssionalising of mutual funds. Academy of Management Journal. 2007; 50 (2):289–307. doi: 10.5465/amj.2007.24634436. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lusch, R. F., & Vargo, S. L. (2014). Service-dominant logic: Premises, perspectives, possibilities. Cambridge University Press.

- March, J. G., & Olsen, J. P. (1983). Organizing political life. What administrative reorganization tells us about government? American Political Science Review, 77 (2), 281–297.

- March, J. G., & Olsen, J. P. (1989). Rediscovering Institutions. New York: Free Press.

- Marx, K. (1852) (1967). The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, Progress Publishing, Moscow.

- Marx K, 1993, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, (Vol. 1), Penguin Books, London.

- Marx K, 1976, The German Ideology. MECW, Vol. 5. Progress Publishers, Moscow (pages 19–539).

- Marx K. Grundrisse. Pelican; 1973. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mattei P, Vigevano L. Contingency Planning and Early Crisis Management: Italy and the COVID-19 Pandemic. Public Organization Review. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s11115-021-00545-1. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Morin, E. (1959) (2004 Edition). Autocritique, Seuil, Paris.

- Morin E. The Stars. University of Minnesota Press; 1982. [ Google Scholar ]

- Morin, E. (1986) (1992 Edition). Method – Towards a Study of nature, Peter Lang, NY.

- Mozumder NA. Can Ethical Political Leadership Restore Public Trust in Political Leaders? Public Organization Review. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s11115-021-00536-2. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nardi, B.A. (Ed.), (1996). Context and consciousness, MIT, Mass.

- Ngoye, B., Sierra, V., & Ysa, T. (2019). Assessing performance-use preferences through an institutional logics lens. International Journal of Public Sector Management .

- Normann, R. (2002). Services Management, Chichester: Wiley.

- Olson M. The logic of Collective Action. Schocken Books; 1970. [ Google Scholar ]

- Osborne SP. from public service dominant logic to public service logic: Are public service organisations capable of co-creation and coproduction? Public Management Review. 2017; 20 (2):225–231. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2017.1350461. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Perrow, C. (1990). Economic Theories of Organization. In: Sharon, Z. & Paul, D. (Eds) Structures of Capital, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 121–152.

- Popper K. Situational logic in social science inquiry: From economics to criminology The. Review of Austrian Economics. 2007; 20 (1):25–41. doi: 10.1007/s11138-006-0006-9. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Prilleltensky I. Values, assumptions, and practices: Assessing the moral implications of psychological discourse and action. American Psychologist. 1997; 52 :517–535. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.52.5.517. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schattschneider EE, 1975, The Semisovereign People: A realist's view of democracy in America, Dryden, Illinois.

- Schattschneider, E.E. (1975). The Semisovereign People: A realist's view of democracy in America, Dryden, Illinois.

- Scott RW. Institutions and organizations. Sage; 2008. [ Google Scholar ]

- Selznick, P. (1948). Foundations of the theory of organization. American Sociological Review, 13 (1), 25–35.

- Selznick P. Leadership in administration. Harper & Row; 1957. [ Google Scholar ]

- Stenvall J, Kinder T, Kuoppakangas P. Unlearning and public services – a case study with Vygotskian approach. Journal of Adult and Continuing Education. 2018; 24 (2):188–207. doi: 10.1177/1477971418818570. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Thornton P, Ocasio W. Institutional logics and the historical contingency of power in organizations: Executive succession in the higher education publishing industry, 1958–1990. American Journal of Sociology. 1999; 105 (3):801–843. doi: 10.1086/210361. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Thornton, P.H., & Ocasio, W. (2017). Institutional logics , in Greenwood R, Oliver C, Lawrence TB and Meyer RE, (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Organisational Institutionalism, Chapter-19.

- Thornton PH, Ocasio W, Lounsbury M. The institutional logics perspective. Wiley; 2015. [ Google Scholar ]

- Toulmin S. Return to reason. Harvard University Press; 2003. [ Google Scholar ]

- Toulmin SE. The uses of argument. Cambridge University Press; 2003. [ Google Scholar ]

- van Benthem J, Pacuit E. Temporal Logics of Agency. Journal of Logic, Language and Information. 2010; 19 (4):389–393. doi: 10.1007/s10849-009-9120-y. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Vargo, S.L., & Lusch, R.F. (2004). Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing , Journal of Marketing, 68, January 1–17.

- Vargo SL, Lusch RF. Service-dominant logic: Continuing the evolution. Journal of Academic Marketing. 2007; 36 :1–10. doi: 10.1007/s11747-007-0069-6. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Vargo SL, Lusch RF. Service-dominant logic 2025. International Journal of Research in Marketing. 2017; 34 (1):46–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ijresmar.2016.11.001. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Vargo SL, Maglio PP, Akaka MA. On value and value co-creation: A service systems and service logic perspective. European Management Journal. 2008; 26 :145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.emj.2008.04.003. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1986). Thought and language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. (Original work published 1934)

- Weber, M. (2006). Whitehead’s Pancreativism, Ontos/Verlad, Frankfurt.

- Weibel, A., & Six, F. (2013). Trust and control: The role of intrinsic motivation. In Handbook of advances in trust research. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Wertsch, J.V., del Rio, P., & Alvarez, A. (1995). Socio-cultural studies: history, action and mediation , in Wertsch JV, del Rio P and Alvarez A, Socio-cultural studies of the mind, CUP, Cambridge.

- Whitehead, A.N. (1929) (1978). Process and reality: An essay in Cosmology, Free Press, NY.

- Wittgenstein, L. (2001) (1923). Anscombe GEM translation, Philosophical Investigations, OUP, Oxford.

- Zacka B. When the state meets the street. Harvard University Press; 2017. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zucker LG. Organizations as Institutions. Research in the Sociology of Organizations. 1983; 2 :1–47. [ Google Scholar ]

This paper is in the following e-collection/theme issue:

Published on 16.4.2024 in Vol 8 (2024)

Experiences, Lessons, and Challenges With Adapting REDCap for COVID-19 Laboratory Data Management in a Resource-Limited Country: Descriptive Study

Authors of this article:

Original Paper

- Kagiso Ndlovu 1 , BSc, MSc, PhD ;

- Kabelo Leonard Mauco 2 , BSc, MSc, PhD ;

- Onalenna Makhura 1 , BSc, MSc, PhD ;

- Robin Hu 3 , BA ;

- Nkwebi Peace Motlogelwa 1 , BSc, MSc ;

- Audrey Masizana 1 , BSc, MSc, PhD ;

- Emily Lo 3 , BA ;

- Thongbotho Mphoyakgosi 4 , BSc ;

- Sikhulile Moyo 5 , BSc, MSc, MPH, PhD

1 Department of Computer Science, University of Botswana, Gaborone, Botswana

2 Department of Learning, Informatics, Management and Ethics, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

3 College of Arts and Sciences, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, United States

4 National Health Laboratory, Ministry of Health, Gaborone, Botswana

5 Botswana Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership, Gaborone, Botswana

Corresponding Author:

Kagiso Ndlovu, BSc, MSc, PhD

Department of Computer Science

University of Botswana

Private Bag UB 0022

Gaborone, 00267

Phone: 267 71786953

Email: [email protected]

Background: The COVID-19 pandemic brought challenges requiring timely health data sharing to inform accurate decision-making at national levels. In Botswana, we adapted and integrated the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) and the District Health Information System version 2 (DHIS2) platforms to support timely collection and reporting of COVID-19 cases. We focused on establishing an effective COVID-19 data flow at the national public health laboratory, being guided by the needs of health care professionals at the National Health Laboratory (NHL). This integration contributed to automated centralized reporting of COVID-19 results at the Ministry of Health (MOH).

Objective: This paper reports the experiences, challenges, and lessons learned while designing, adapting, and implementing the REDCap and DHIS2 platforms to support COVID-19 data management at the NHL in Botswana.

Methods: A participatory design approach was adopted to guide the design, customization, and implementation of the REDCap platform in support of COVID-19 data management at the NHL. Study participants included 29 NHL and 4 MOH personnel, and the study was conducted from March 2, 2020, to June 30, 2020. Participants’ requirements for an ideal COVID-19 data management system were established. NVivo 11 software supported thematic analysis of the challenges and resolutions identified during this study. These were categorized according to the 4 themes of infrastructure, capacity development, platform constraints, and interoperability.

Results: Overall, REDCap supported the majority of perceived technical and nontechnical requirements for an ideal COVID-19 data management system at the NHL. Although some implementation challenges were identified, each had mitigation strategies such as procurement of mobile Internet routers, engagement of senior management to resolve conflicting policies, continuous REDCap training, and the development of a third-party web application to enhance REDCap’s capabilities. Lessons learned informed next steps and further refinement of the REDCap platform.

Conclusions: Implementation of REDCap at the NHL to streamline COVID-19 data collection and integration with the DHIS2 platform was feasible despite the urgency of implementation during the pandemic. By implementing the REDCap platform at the NHL, we demonstrated the possibility of achieving a centralized reporting system of COVID-19 cases, hence enabling timely and informed decision-making at a national level. Challenges faced presented lessons learned to inform sustainable implementation of digital health innovations in Botswana and similar resource-limited countries.

Introduction

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in a global public health crisis [ 1 ]. The pandemic stretched almost all health care systems to their limits and exposed their weaknesses [ 2 ]. Previously documented COVID-19 challenges for the health sector include a lack of the health care services needed for the pandemic, inadequate resources, limited testing ability and capacity for a COVID-19 response, as well as overall poor data management within existing health care systems [ 1 ]. It was previously projected that countries in sub-Saharan Africa could see a sharp rise in COVID-19 infection rates and deaths, as such challenges are prominent in resource-limited countries [ 3 ]. This projected disproportionate impact of COVID-19 in resource-limited countries comes as no surprise. Currently, the health sector in high-income countries is deemed as underfunded, while in most resource-limited countries, it is reportedly heavily underfunded [ 4 ]. It is not a surprise that, in 2001, African leaders through the African Union’s Abuja Declaration agreed to “allocate 15% of the state’s annual budget to the improvement of the health sector” [ 5 ]. However, in 2013, only 5 African countries had achieved this target, while in 2018, only 2 countries achieved the target [ 6 ].

Access to accurate and current information has been recognized globally as a critical requirement for timely COVID-19 pandemic responses [ 7 ]. As such, the pandemic presented the need for robust data management systems in response to the evolving nature of COVID-19 [ 8 ]. Ideally, eHealth—“cost-effective and secure use of information and communications technologies (ICT) in support of health and health-related fields, including health-care services, health surveillance, health literature, and health education, knowledge and research” [ 9 ]—could ensure reliable information reporting and timely decision-making by governments and relevant stakeholders. However, requirements for such eHealth solutions present a greater challenge for resource-limited countries with documented weak ICT infrastructure, limited maintenance budgets, a lack of health human resource capacity to utilize eHealth systems, and nonuniform unique patient identifiers [ 10 ]. According to Archer et al [ 11 ], other factors affecting successful implementation of eHealth solutions in resource-limited countries include the absence of eHealth agendas, ethical and legal considerations, common system interoperability standards, and reliable power supplies.

Similar to other nations responding to the pandemic, the government of Botswana, through the Ministry of Health (MOH), identified eHealth as a means to improve COVID-19 data management and address complex data capture and transfer processes at various port of entries and the National Health Laboratory (NHL). Botswana’s eHealth infrastructure was previously reported as generally adequate, with functioning computers and some communication systems such as telephones, email, and Internet services [ 12 ]. According to Seitio-Kgokgwe et al [ 12 ], almost all public health facilities in Botswana are now connected to the government data network (GDN) with an average Internet connectivity of about 2 Mbps. The authors further highlighted that Botswana's eHealth initiatives have always operated within a very weak policy and regulatory framework characterized by inadequate health information legislation, national policy, and strategic plan. Fragmentation and inefficient eHealth initiatives were noted as other contributing factors to poor utilization of information in Botswana's health sector, as well as the lack of appreciation of the important role played by health information in managing health services. Currently, over 52 health laboratories operate in Botswana, 8 of which are accredited with national certifications like the South African National Accreditation System (SANAS), Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA), International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 15189, or the Southern African Development Community Accreditation Services (SADCAS) [ 13 , 14 ].

The Botswana NHL is one of the accredited laboratories tasked with the management of national COVID-19 testing. The NHL has decentralized its COVID-19 testing services from the capital city Gaborone, by operating satellite testing centers in selected districts with sizable populations and key ports of entry into the country. The NHL data flow is such that specimen data go through each of the 4 laboratory stages of (1) Reception Lab (all incoming lab specimens are captured using a barcode scanner), (2) Extraction Lab (specimen processing for nucleic acid isolation and purification), (3) Detection Lab (sample amplification and detection), and (4) Resulting and Verification Lab (lab results are captured and verified for release to clients). The need to scan laboratory specimen samples at each of the laboratory phases is an important quality assurance step. Accession numbers in laboratory processes are critical to link the specimen with a participant. Despite having an already existing eHealth system at the NHL, electronic data transfers within and across the 4 laboratories were considered tedious, time consuming, and a risk to both data quality and timely COVID-19 results reporting. These limitations required immediate attention.

The authors volunteered their technical support toward implementation of a customizable COVID-19 data management system—Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)—at the NHL. REDCap was suggested by the authors following its documented benefits including its utility within a resource-limited country context [ 15 , 16 ], as well as its availability locally through the University of Botswana (UB). REDCap is a secure, web-based platform designed to support electronic data capture. It was developed at Vanderbilt University in the United States in 2004 and can be set up to support a variety of health care environments and scenarios. REDCap is compliant with international standards such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

In order to support timely reporting of COVID-19 cases, the REDCap platform was linked to the District Health Information System version 2 (DHIS2) at the MOH. DHIS2 is another open-source platform for collecting, processing, and analyzing health data. It was developed and first implemented in 1998 by the Health Information System Programme (HISP) in South Africa and offers a secure web-based electronic data capture, analysis, and reporting tool [ 17 ]. Similar to REDCap, the DHIS2 platform has a mobile application (DHIS Tracker), enabling its use in case of weak and fluctuating Internet connectivity. The DHIS2 Tracker allows for auto-syncing of data with the central server once stable Internet connectivity returns. The data elements shared between DHIS2 and REDCap include COVID-19 test results and demographic information of those who were tested including their names, gender, ages, locations, and related underlying medical conditions.

Through a participatory design approach [ 18 , 19 ], the REDCap platform was customized to support the NHL data process needs, with the goal of increasing operational efficiency and reducing overreliance on paper-based manual approaches. The authors’ preference for a participatory design approach aligns with that of Berntsen [ 20 ] who acknowledged that initial involvement of end users is central to the development of a health information system. This study reports on the experiences, challenges, and lessons learned while designing, adapting, and implementing REDCap and the DHIS2 platform to support COVID-19 data management processes at the NHL in Botswana.

A participatory design approach was adopted to guide the design, customization, and implementation of REDCap for COVID-19 data management at the NHL.

Study Population, Setting, and Design

Participants.

All NHL and MOH personnel responsible for processing COVID-19 specimen samples and data were invited to participate. All potential participants were sent an introductory email describing the background and objectives of the study. A consent form was subsequently shared with all those who showed interest. All invited participants agreed to participate in the study, of which 29 were NHL personnel and 4 were based at the MOH. Of the 29 NHL personnel, 12 were based at the Reception Lab, and 17 were based at the Extraction, Detection, and Resulting and Verification Labs. The study spanned from March 2, 2020, to June 30, 2020.

Data collection was conducted in 3 phases.

Phase 1: Participant Engagement

The authors facilitated a 1-day consultative physical meeting or workshop with the study participants to solicit specific requirements for the COVID-19 data management system. Study participants were requested to define requirements for an ideal COVID-19 data management system. The authors recorded all participants' responses during the session which lasted for 1 hour. Based on the insights gathered from this exercise, iterative design and testing approaches were adopted for each key deliverable from design, customization, and implementation of the REDCap platform to support COVID-19 data management. A minimum of 2 iterations and a maximum of 4 iterations were incurred per deliverable, and this was influenced by the complexity or noncomplexity of the tasks.

Phase 2: Implementation and Assessment of the Platform to Meet User Requirements

Design and customization of the REDCap platform were followed by implementation of the solution as well as evaluating its feasibility to address the previously noted requirements and specifications. This involved participants testing the REDCap platform and providing feedback on any issues or challenges they encountered.

Phase 3: Human Resource Capacity Development

At each phase of the design, customization, and implementation of the REDCap platform, participants were trained on the various system components and had the opportunity to share their feedback to inform next steps.

Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Botswana (Reference: UBR/RES/IRB/BIO/GRAD/244). All data experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations such as the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants were informed of the objective of the exercise as well as their voluntary participation, and all gave informed consent for this study. Those who consented to participate were immediately sensitized and granted access to the REDCap instance at the UB. No compensation was provided for participating in the study.

Data Analysis

NVivo 11 software was used for thematic analysis [ 21 ] of data to determine participants’ requirements for an ideal COVID-19 data management system and their postimplementation experiences.

Study participants consisted of all personnel involved with handling COVID-19 specimens and managing all relevant laboratory data at both the NHL and MOH ( Table 1 ).

Consultative meetings with study participants led to the identification of user requirements for an ideal COVID-19 data management system at the NHL. These were categorized under the following 2 themes: functional and nonfunctional requirements ( Table 2 ).

a REDCap: Research Electronic Data Capture.

b DHIS2: District Health Information System version 2.

Although this paper reports on challenges and resolutions while implementing REDCap at the NHL ( Table 3 ), Figures 1 - 7 are intended to illustrate the design, customization, and implementation of the REDCap platform at the NHL.

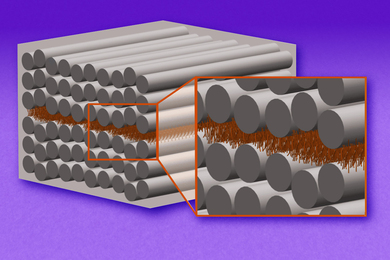

The authors used participants’ feedback to guide the design of an ideal COVID-19 data flow architecture for this study ( Figure 1 ).

The REDCap data security architecture at UB separates the web server from the database server ( Figure 2 ).

In order to facilitate timely decision-making and address a key technical requirement (“Automated COVID-19 results sync with the DHIS2 system” in Table 2 ), the REDCap system was linked with the DHIS2 system at the MOH for aggregate data reporting.

Interfacing between DHIS2 and REDCap was controlled by the DHIS2 link application programming interface (API; Figure 3 ). The DHIS2 API link supported 3 functionalities: (1) data format conversions between DHIS2 and REDCap, (2) avoiding duplicate synchronizing of data between REDCap and DHIS2, and (3) enabling data access for the DHIS2 front end, which relied on the API to make consistent data available for the 2 systems.

In order to access the DHIS2 API, a RestTemplate object short code was implemented with basic authentication secured by username and password ( Figure 4 ).

Study participants accessed REDCap using their personal account details (unique usernames and passwords) before proceeding to collect, manage, and report on COVID-19 at the MOH ( Figure 5 ).

Of important note, the REDCap platform triggered automated email alerts whenever a COVID-19 positive result was recorded. The email alerts were sent to study coordinators at the MOH.

A third-party web application simplified the process of pulling records from the DHIS2 system into REDCap ( Figure 6 ) and enabled the viewing of specimen barcodes through a web browser ( Figure 7 ).

Challenges and resolutions while implementing the REDCap platform to support COVID-19 data management at the NHL are summarized in Table 3 .

This paper describes the experiences, challenges, and lessons learned while designing, customizing, and implementing the REDCap platform for COVID-19 data management at the NHL in Botswana. REDCap implementation challenges and lessons identified during the study were categorized under the following 4 themes: (1) infrastructure, (2) capacity development, (3) platform constraints, and (4) interoperability.

Infrastructure

The literature emphasizes the critical need for robust ICT infrastructure to serve as the backbone for successful and sustainable digital health implementation [ 22 - 25 ]. The national eHealth strategy tool kit by the World Health Organization (WHO) and International Telecommunication Union (ITU) identifies essential eHealth infrastructure components as high-speed data connectivity, computing infrastructure, identification and authentication services, directory services, health care provider systems, electronic health record repositories, and health information data sets, all of which underpin a national eHealth environment [ 26 ]. The tool kit further urges countries to secure long-term funding for investment in national eHealth infrastructure and services. It is against this backdrop that the WHO recognizes a pressing need for countries to invest in infrastructure to support digital transformation; Internet connectivity; and issues related to legacy infrastructure, technology ownership, privacy, and security while adapting and implementing globally recognized standards and technologies [ 27 ].

In this study, infrastructural challenges experienced include weak Internet speed and misalignment of computer network firewalls between the GDN and the UB network. These issues resonate with the identified ICT infrastructural challenges within the Botswana National eHealth strategy [ 28 ]. During implementation of the REDCap platform at the NHL, initial Internet download and upload speeds were 12.59 Mbps and 16.84 Mbps, respectively ( Table 3 ). The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) considers minimum Internet speeds of 5 Mbps to 25 Mbps as ideal to support online tasks such as file download and telecommuting [ 29 ]. However, despite meeting the FCC requirement, study participants reported the need for the Internet speed to be upgraded to adequately support frequent data transactions and data sharing between REDCap and the DHIS2 platform. This could be due to multiple factors. The following are some example quotes from study participants pertaining to their dissatisfaction with the Internet bandwidth:

Internet connectivity is still slow. [participant, NHL Reception Lab]

Internet bandwidth needs to be upgraded. [participant, NHL Resulting and Verification Lab]

As a mitigation for the slow Internet connectivity, relevant government departments were engaged, and measures were put in place to increase the Internet speed. This includes procurement of mobile Internet routers from private internet service providers (ISPs) for use during the study. The engagement of private sector stakeholders to support implementation of eHealth initiatives is also highlighted as essential within the “Strategy and Investment” pillar of the Botswana National eHealth Strategy, which emphasizes “eHealth planning, with involvement of major stakeholders and sectors” [ 28 ].

Another challenge was the restriction introduced by computer network firewalls resulting in data flow constraints between the GDN and UB networks. A similar issue was encountered in another study, in which implementation of the REDCap platform incurred network firewall challenges hindering participants from using computers outside the Veterans Health Administration network to complete a survey on REDCap [ 30 ]. According to Nagpure et al [ 31 ], firewall policy conflicts can be complex to eliminate but could be addressed through practical resolution methods such as the “first-match resolution” involving “identifying which firewall policy rule involved in a conflict situation should take precedence when multiple conflicting rules (with different actions) filter a particular network packet simultaneously.” At the NHL, the authors resolved the network firewall challenges by engaging relevant ICT authorities at both governmental and UB IT departments to facilitate reconfiguration of the firewall settings to allow data flow between the 2 networks. This necessitated effective measures for data security, privacy, and confidentiality throughout the study. To achieve this, the authors ensured that the REDcap and DHIS2 servers communicate through an encrypted Internet connection using a 128-bit Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) certificate. The use of SSL has been previously considered a standard technology for securing electronic commerce and electronic banking transactions over the Internet [ 32 ]. However, recent advances in cybersecurity attacks call for using technologies to detect compromised SSL network traffic [ 33 ]. This consideration was brought to the attention of both governmental and UB IT departments. Compliance with the Botswana-specific Data Protection Act [ 34 ] could improve the necessary safeguards for the right to privacy of individuals and the collection and transfer of their personal data.

Capacity Development