Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- NEWS FEATURE

- 05 April 2024

After the genocide: what scientists are learning from Rwanda

- Nisha Gaind

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

A 1994 photograph shows the altar in Ntarama Church, where more than 5,000 people were murdered during the genocide against the Tutsi. Credit: Lane Montgomery/Getty

Lire en français

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Nature 628 , 250-254 (2024)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-00997-7

Additional reporting and logistical support by Aimable Twahirwa, a freelance science journalist in Kigali.

Neugebauer, R. et al. Int. J. Epidemiol. 38 , 1033–1045 (2009).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Yehuda, R. & Bierer, L. M. Progr . Brain Res. 167 , 121–135 (2007).

Article Google Scholar

Perroud, N. et al. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 15 , 334–345 (2014).

Musanabaganwa, C. et al. Epigenomics 14 , 11–25 (2022).

Musanabaganwa, C. et al. Epigenomics 14 , 887–895 (2022).

King, E. & Samii, C. Diversity, Violence, and Recognition: How Recognizing Ethnic Identity Promotes Peace (Oxford Univ. Press, 2020).

Google Scholar

Benda, R. M. Youth Connekt Dialogue: Unwanted Legacies, Responsibility and Nation-building in Rwanda . Working Paper (Genocide Research Hub & Aegis Trust, 2017).

Benda, R. M. in Rwanda Since 1994: Stories of Change (eds Grayson, H. & Hitchcott, N.) 189–210 (Liverpool Univ. Press, 2019).

Chemouni, B. & Mugiraneza, A. Afr. Aff. 119 , 115–140 (2020).

Straus, S. Making and Unmaking Nations: War, Leadership, and Genocide in Modern Africa (Cornell Univ. Press, 2015).

Ndahinda, F. M. & Mugabe, A. S. J. Genocide Res. 26 , 48–72 (2024).

Duclert, V. France, Rwanda and the Tutsi — Genocide (1990–1994) — Report Submitted to the President of the Republic on 26 March, 2021 (Armand Colin, 2021).

Mukagasana, Y. La mort ne veut pas de moi (Fixot, 1997).

Download references

Reprints and permissions

Related Articles

The kill switch

- Human behaviour

Save the forest to save the tiger — why vegetation conservation matters

News & Views 21 MAY 24

Found at last: long-lost branch of the Nile that ran by the pyramids

News 16 MAY 24

Balls of lightning and flames from the sky: can science explain?

News & Views 14 MAY 24

Daniel Kahneman obituary: psychologist who revolutionized the way we think about thinking

Obituary 03 MAY 24

Pandemic lockdowns were less of a shock for people with fewer ties

Research Highlight 01 MAY 24

Rwanda 30 years on: understanding the horror of genocide

Editorial 09 APR 24

Brazil’s plummeting graduate enrolments hint at declining interest in academic science careers

Career News 21 MAY 24

Reading between the lines: application essays predict university success

Research Highlight 17 MAY 24

How to stop students cramming for exams? Send them to sea

News & Views 30 APR 24

Postdoctoral Fellow

New Orleans, Louisiana

Tulane University School of Medicine

Postdoctoral Associate - Immunology

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Postdoctoral Associate

Vice president, nature communications portfolio.

This is an exciting opportunity to play a key leadership role in the market-leading journal Nature Portfolio and help drive its overall contribution.

New York City, New York (US), Berlin, or Heidelberg

Springer Nature Ltd

Senior Postdoctoral Research Fellow

Senior Postdoctoral Research Fellow required to lead exciting projects in Cancer Cell Cycle Biology and Cancer Epigenetics.

Melbourne University, Melbourne (AU)

University of Melbourne & Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Open access

- Published: 11 April 2019

The long-term health consequences of genocide: developing GESQUQ - a genocide studies checklist

- Jutta Lindert 1 , 2 ,

- Ichiro Kawachi 3 ,

- Haim Y. Knobler 4 ,

- Moshe Z. Abramowitz 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ,

- Sandro Galea 5 ,

- Bayard Roberts 6 ,

- Richard Mollica 7 &

- Martin McKee 6

Conflict and Health volume 13 , Article number: 14 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

36k Accesses

1 Citations

15 Altmetric

Metrics details

Genocide is an atrocity that seeks to destroy whole populations, leaving empty countries, empty spaces and empty memories, but also a large health burden among survivors is enormous. We propose a genocide reporting checklist to encourage consistent high quality in studies designed to provide robust and reliable data on the long term impact of genocide.

An interdisciplinary (Public Health, epidemiology, psychiatry, medicine, sociology, genocide studies) and international working committee of experts from Germany, Israel, the United States, and the United Kingdom used an iterative consensus process to develop a genocide studies checklist for studies of the long term health consequences.

We created a list of eight domains (A Ethical approval, B External validity, C Misclassification, D Study design, E Confounder, F Data collection, G Withdrawal) with 1–3 specific items (total 17).

The genocide studies checklist is easy to use for authors, journal editors, peer reviewers, and others involved in documenting the health consequences of genocide.

Genocides have brought immeasurable suffering to millions of people in the 20th and the early years of the twenty-first century. [ 1 , 2 ] They have attracted the attention of researchers from a range of disciplines, including epidemiologists, historians, political scientists, psychologists, anthropologists, demographers, and others, with genocide studies emerging as a distinct body of scholarship. Each discipline offers important perspectives on a phenomenon whose horror is beyond the imagination of most people. The impact of genocide continues long after the killing has ended, leaving lifelong scars on survivors and, potentially, their offspring. [ 2 ] Yet, as revealed in a recent systematic review, this research has taken a wide variety of approaches and produced heterogeneous, and, in some cases, conflicting findings, suggesting a range of consequences between severe long term impact and no impact. [ 2 ] This conflicting evidence leads to several conclusions.

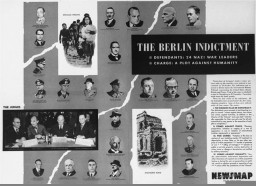

First, genocide - as defined in the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPPCG) adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 9th of December 1948 as General Assembly Resolution 260 (III, article 2) - can take many forms, from the semi-organized chaos of Rwanda systematic murder of Jews by Nazis and/or their allies in the Genocide termed the Holocaust, with differences in exposures to mass atrocities (e.g. duration, types of genocidal acts). The Convention defines genocide as an attempt “to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group.” Genocidal acts include “killing members of the group; [and] causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group”, and deliberately inflicting “conditions of life, calculated to bring about [a group’s] physical destruction in whole or in part; imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; [and] forcibly transferring children of the group to another group”. [ 3 ] These definitions suggest a breadth of exposures that can be associated with genocide. Table 1 lists those events that have been designated officially by the United Nations as genocides, as well as the range of estimates of those killed and the percentages of the target populations affected.

A second concern relates to methodological differences among studies. For example, studies reviewing the mental health impact of genocides have investigated a variety of outcomes, including depression, anxiety, schizophrenia [ 4 , 5 ], suicide [ 6 , 7 ], post-traumatic stress as well post-traumatic growth. Some studies documented a negative impact, while others found resilience or no association notwithstanding immense cruelties to which survivors had been exposed. [ 8 ] Some of this variability may be due to the methodological challenges inherent in conducting studies on populations affected by genocide. Some are common to any epidemiological research and include recruitment bias, measurement error, and the need to adjustment for potential confounding. Attempts to attribute symptoms to the experience of genocide may be complicated by confounding factors unrelated to the genocide, such as discrimination in another country due to migration or poverty. [ 9 ] Other factors, however, are specific to genocide research. One is memoralization, whereby groups valorize, marginalize, or disable acts of remembrance, or forgetting. [ 10 , 11 ] Anthropological research has reported how some genocide survivors or children of survivors challenge the pathologizing construct of long term impact of genocides. It can be politically expedient to pathologize the long term consequences of genocide, or, conversely, to deny the long term impacts of genocides as part of an attempt to relieve the perpetrator from responsibility for having committed genocide. Disorders associated with genocide are therefore subject to the influence of various interests, institutions, and political interests.

The need for clear, transparent, and reliable reporting of research has led to important initiatives such as the Strengthening Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology Statement (STROBE). [ 12 ] The STROBE statement, published in 2007, is an evidence-based 22 item set of recommendations for reporting observational studies (cohort studies, case-control studies, and cross-sectional studies) and has been credited with improvements in quality of reporting. [ 13 ] However, the STROBE statement is designed to apply to all observational studies, [ 8 ] and it does not adequately capture some of the key challenges inherent in post-genocide research.

Seeking to address this shortcoming, an international group of experts (JL, MZA, HJK, SG, RM, BR, MMcK, IK) with a specific interest in genocide and health worked together on a systematic review. [ 2 ] Important gaps in STROBE that were specific to studies of genocide and health were identified and agreement was reached that an extension of STROBE was warranted. Thus, the QUALITY ASSESSMENT TOOL FOR QUANTITATIVE GENOCIDE STUDIES (GESUQ) initiative was established as an international collaborative project to address these issues. Herein, we propose recommendations for reporting genocide and related research.

First, we searched for any existing reporting guideline covering long term impacts of genocide. Second, we sought relevant evidence regarding the quality of reporting. Neither search yielded any results. Third, we identified experts (i.e., methodologists, psychiatrists, epidemiologists, and genocide experts) who could advise on potential sources of bias, from relevant genocide projects and reference documents. They were then asked for recommendations. Fourth, the group met in person and via Skype meetings to agree the wording of the statements. Stakeholders reviewed the statements and provided feedback. The final checklist and this explanatory document were drafted by the three members of the working committee. During two face-to-face and three skype meetings, members of the group discussed the input received and prepared new versions that were circulated until consensus on all items was reached.

Items in the GESUQ checklist

The complete GESUQ checklist is provided in the Additional file 1 . In the following sections we explain the rationale for choosing items A-H in GESUQ.

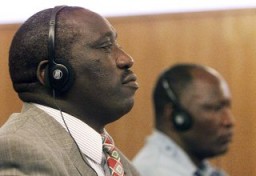

A. Ethical approval

Research on the impact of genocide must adhere to same ethical standards that guide all other research. [ 14 ] This includes that all research participants have the capacity to provide informed consent. As in other research, investigators should maintain the principles of approval of research by institutional review boards (IRBs) respecting not only confidentiality and privacy but the importance of expertise in genocide research within the research team, including the specific genocide-related challenges that exist. Among these challenges are extra provisions to minimize harm to human subjects (e.g. the potential for retaliation from those who perpetrated the genocide), and extra steps to provide medical resources / referral to people still suffering from lingering mental health effects. Given the particular risk of causing distress by asking questions about past events in this vulnerable population there is a need to ensure mechanisms for referral information for mental health support. These ethical questions are especially difficult in situations in which genocide perpetrators, genocide victims, and genocide bystanders are forced to live together even after the genocide (e.g. in the case of Rwanda [ 15 ]).

B. External validity and selection bias

In genocide studies as in other epidemiological studies, attention to sampling methods is crucial. Often in the early aftermath of genocide, health studies either comprise only convenience samples or clinical samples (populations that manifest some kind of pathology, i.e. post-traumatic symptoms) and have sought and obtained care. This is understandable given the challenges of recruitment but is likely to introduce bias as such participants go through several stages of selection and thus, both in practice and theory, may differ from participants drawn from random samples of those exposed. Random sampling should therefore be used. Where this is not possible, analyses should include appropriate weighting. This can avoid the challenge of biased estimates of the incidence and prevalence of certain disorders (e.g., Posttraumatic Stress Disorder). Given the difficulty of random sampling in many settings, alternative methods such as respondent driven sampling may be useful adjuncts. [ 16 ]

It is important to recognize the inevitable scope for survivor bias, both in terms of surviving the events in question and their sequelae. Consequently, and to a greater degree with genocide than many other exposures, any sample will not be representative of all those exposed.

C. Avoiding misclassification

Any flaw in measuring exposure, outcome, or covariates can overestimate or underestimate the true value of the association. [ 17 , 18 , 19 ] This is a challenge in many areas of epidemiology, but is especially so with genocide. Does exposure include direct and indirect exposure (such as the death of family members or friends, and if so, in the presence or absence of the subject)? How is the duration of exposure measured? Reporting of genocide exposure should include the nature, intensity, and length of exposure. This assessment of exposure could draw on approaches adopted in other areas of epidemiology, such as the job-exposure matrix used in occupational epidemiology. [ 20 , 21 ] Accordingly, assessment of exposure should be quantified systematically. For example, one could inquire about direct personal experiences of genocide (e.g. whether one’s relatives were killed). But in genocide research it is also relevant to assess exposure to genocide even if someone was not directly affected - i.e. there may be spillover effects of genocide in a community. [ 22 ] In genocide research both direct and indirect exposures are of interest. Research on the impact of genocide on subsequent generations creates additional challenges, in measuring both the nature and timing of exposure. [ 2 , 5 ] Our guidelines seek to guide researchers to be explicit about why the exposure measurement was carried out in a certain way.

Genocide studies seek accuracy in reporting the incidence, prevalence, and burden of disease so avoiding diagnostic errors is crucial. It is essential to understand the psychometric properties of health measures used among those affected by genocide. Expressions of suffering due to genocide may differ by populations. In the area of mental health, the DSM-5 [ 23 ] emphasizes the need for measures that capture culturally grounded concepts of distress, [ 24 ] something that is largely missing from genocide studies so far.

D. Study design

Most genocide studies will, inevitably, be retrospective and observational, e.g. case-control or cohort studies. The selection of controls is a major challenge as they should resemble, as closely as possible, those who experienced the genocide without themselves being exposed. The objective of genocide studies therefore is to find an unexposed control group that resembles the exposed group as closely as possible. For example, in studies of the health effects of the Holocaust, investigators have compared Jews who emigrated to Israel before and after the Holocaust. However, even this design poses challenges, since there will be many unobserved factors that could confound the comparison being made, e.g. those who escaped before the Holocaust may have had more extensive social networks to help them escape, and stronger social networks would make such individuals more resilient to adverse mental health effects.

Research undertaken in Israel has used the National Population Register. This is a unique resource for genocide studies. [ 4 ] However, should such a situation arise in the future, the ability to use a similar resource will depend upon the nature of consent given at enrolment, the degree of anonymisation, and the data protection laws in place in the country concerned.

F. Confounders

If the question of interest involves identifying the causal effects of genocide experience on mental health outcomes, the investigator must identify (and control for) factors that influence the probability of both the exposure and the outcome being studied. For example, in a study of exposure to genocide and the outcome of poor mental health, socioeconomic disadvantage could be a confounder. Someone disadvantaged in this way may be less able to escape the that would make a person less able to escape the direct and indirect effects of genocide, for example because of fewer material resources. However, there is also a well-recognized association between disadvantage and adverse mental health outcomes. It is good epidemiological practice to control for confounders but it is also important not to over control. Thus, genocide is often the final end-result of many decades (perhaps even centuries) of unjust treatment of a particular group in society. Hence, a confounder such as “low socioeconomic status” may itself represent an effect of the underlying injustice which preceded genocide. For example, immediately before and during the Holocaust, many Jewish children and adolescents were excluded from studies in public schools. One would not control for “confounding” by educational attainment in this instance, because interruption of schooling is part of the exposure (the Holocaust) that we are trying to understand. Likewise, the experience of escaping from the genocide constitutes a part of the exposure.

There are several approaches to addressing these issues, including the thorough review of the literature and use of methods such as directed acyclic graphs (DAGs), [ 25 ] multivariable regression to help adjust for potential confounders and structural equation modelling (path analysis). [ 26 ]

F. Data collection methods

Data can be collected in ad hoc surveys or, in rare cases, as with the Israeli National Population Register, from routine sources, as noted above. Valid and reliable assessment of exposures and outcomes requires carefully developed instruments, which have ideally been evaluated in different cultural settings. The attributes (e.g. recall period, question/response format) and mode of administration (e.g. interviewer-, self-administered) of existing instruments are extremely varied and many have not been evaluated for use in different cultural contexts or age groups.

In summary, there are substantial challenges in epidemiological studies of survivors of mass atrocities, crimes against humanity, and genocide. However, data are needed to better serve this population. The GESUQ guidelines are a first step to better understand the mental health impact of mass atrocities, crimes against humanity, and genocide. These proposed guidelines are specific to observational genocide research and serve as starting point for improving epidemiological research on the impact of violence on health. GESUQ was created as a guide for authors, journal editors, peer reviewers, and other stakeholders to encourage researchers to improve the quality and completeness of reporting in genocide and war epidemiology. To our knowledge, our guidelines are the first to have been proposed for use specifically in genocide studies. As with other reporting guidelines, these complement the instructions in editorial and review processes to ensure a clear and transparent account of the research conducted. Experts we contacted generally welcomed the initiative and provided constructive feedback. The checklist will subsequently be translated into other languages, and disseminated widely. Ongoing feedback is encouraged to improve it.

While GESUQ represents our best attempt to reflect the interest and priorities of stakeholders and the interested public in genocide research, we recognize that the methods used in observational health research are changing rapidly, and the availability of different types of data for such research is expanding. For example, mobile health applications (mHealth apps) are becoming widely available for smartphones and wearable technologies. While there is limited experience so far with these data sources in genocide research, we anticipate rapid growth in the near future. Additionally, health care providers in for instance Israel offer good registry data on more outcomes than government data that can be linked to Holocaust exposure without sample selection.

The nature of genocide poses some obvious limitations on the conduct of associated research. First, while we have described this instrument as one for use in genocide studies, the international community has shown a great reluctance to use the term “genocide” because of the implications, in particular the “responsibility to protect”. However, the issues we have discussed in developing this instrument will be equally applicable in many situations involving large scale killings that are not subsequently labelled as genocide. Second, it will continue to be extremely difficult to collect data in real time and any attempt to do so would face a myriad of methodological and ethical challenges, as was apparent in studies seeking to quantify the death toll in post-invasion Iraq. Consideration of these issues goes beyond the scope of this paper.

Conclusions

We have created GESUQ in the form of a checklist, trying to take account of and learn from existing guidelines. While we anticipate that GESUQ will change as research methods evolve, these guidelines should encourage better reporting of research over the coming years. With implementation by authors, journal editors, and peer reviewers, we anticipate that GESUQ will improve transparency, reproducibility, and completeness of reporting of research on genocide and health and, especially, much-needed research on evidence-based interventions for genocide affected populations.

Abbreviations

Prof. Bayard Roberts

Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide

Directed acyclic graphs

Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Genocide Studies

Prof. Haim Y. Knobler

Prof. Ichiro Kawachi

Institutional review boards

Prof. Jutta Lindert

Mobile health applications

Prof. Martin McKee

Dr. Moshe Z. Abramowitz

Prof. Richard Mollica

Socioeconomic status

Prof. Sandro Galea

Strengthening Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology Statement

Bloxham D, Moses AD. The Oxford handbook of genocide studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2010.

Google Scholar

Lindert J, Knobler HY, Kawachi I, Bain PA, Abramowitz MZ, McKee C, Reinharz S, McKee M. Psychopathology of children of genocide survivors: a systematic review on the impact of genocide on their children’s psychopathology from five countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(1):246–57.

PubMed Google Scholar

General assembly of the United Nations: convention on the prevention and punishment of the crime of genocide. New York: United Nations, 1948.

Levine SZ, Levav I, Pugachova I, Yoffe R, Becher Y. Transgenerational effects of genocide exposure on the risk and course of schizophrenia: a population-based study. Schizophr Res. 2016;176(2–3):540–5.

Article Google Scholar

Levine SZ, Levav I, Goldberg Y, Pugachova I, Becher Y, Yoffe R. Exposure to genocide and the risk of schizophrenia: a population-based study. Psychol Med. 2016;46(4):855–63.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Levine SZ, Levav I, Yoffe R, Becher Y, Pugachova I. Genocide exposure and subsequent suicide risk: a population-based study. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0149524.

Bursztein Lipsicas C, Levav I, Levine SZ. Holocaust exposure and subsequent suicide risk: a population-based study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52(3):311–7.

Lindert J, McKee M, Knobler H, Abramovitz M, Bain P. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of genocide on symptom levels of mental health of survivors, perpetrators and on-lookers: PROSPERO international prospective register of systematic reviews; 2016.

Panter-Brick C, Eggerman M, Mojadidi A, McDade TW. Social stressors, mental health, and physiological stress in an urban elite of young afghans in Kabul. Am J Hum Biol. 2008;20(6):627–41.

Stone D. Genocide and memory. In: Stone D, editor. The holocaust, fascism and memory: essays in the history of ideas. Edn. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK; 2013. p. 143–56.

Chapter Google Scholar

Hinton AL. Annihilating difference. The antropology of genocide. Los Angeles: University of California Press; 2002.

Book Google Scholar

Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):573–7.

Bezo B, Maggi S. Living in "survival mode": intergenerational transmission of trauma from the Holodomor genocide of 1932-1933 in Ukraine. Soc Sci Med. 2015;134:87–94.

Wassenaar D, Mamotte N. Ethical issues and ethics reviews in social science research. In: Leach M, Stevens M, Lindsay G, Ferrero A, Korkut Y, editors. The Oxford handbook of international psychological ethics. Edn. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012. p. 268–82.

Rutayisire T, Richters A. Everyday suffering outside prison walls: a legacy of community justice in post-genocide Rwanda. Soc Sci Med. 2014;120:413–20.

Rothman KJ, Gallacher JE, Hatch EE. Why representativeness should be avoided. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(4):1012–4.

Jurek AM, Greenland S, Maldonado G, Church TR. Proper interpretation of non-differential misclassification effects: expectations vs observations. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34(3):680–7.

Copeland KT, Checkoway H, McMichael AJ, Holbrook RH. Bias due to misclassification in the estimation of relative risk. Am J Epidemiol. 1977;105(5):488–95.

Greenland S. Variance estimation for epidemiologic effect estimates under misclassification. Stat Med. 1988;7(7):745–57.

Milner A, Niedhammer I, Chastang JF, Spittal MJ, LaMontagne AD. Validity of a job-exposure matrix for psychosocial job stressors: results from the household income and labour dynamics in Australia survey. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0152980.

Fischer HJ, Vergara XP, Yost M, Silva M, Lombardi DA, Kheifets L. Developing a job-exposure matrix with exposure uncertainty from expert elicitation and data modeling. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2015;27:7–15.

Rubanzana W, Hedt-Gauthier BL, Ntaganira J, Freeman MD. Exposure to genocide as a risk factor for homicide perpetration in Rwanda: a population-based case-control study. J Interpers Violence. 2018;33(12):1855–70.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 5. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Kaiser BN, Haroz EE, Kohrt BA, Bolton PA, Bass JK, Hinton DE. “Thinking too much”: a systematic review of a common idiom of distress. Soc Sci Med. 2015;147:170–83.

Shrier I, Platt RW. Reducing bias through directed acyclic graphs. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:70–85.

Ullman JB, Bentler PM. Structural equation modeling. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 2003.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Linda Wulkau for helping to edit the manuscript.

The study was done without any additional funding.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Health and Social Work, University of Applied Sciences Emden/Leer, Constantiaplatz 4, 26723, Emden, Germany

Jutta Lindert & Moshe Z. Abramowitz

Women’s Research Center, Brandeis University, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA

Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts, USA

Ichiro Kawachi & Moshe Z. Abramowitz

Hadassah Medical School, Jerusalem, Israel

Haim Y. Knobler & Moshe Z. Abramowitz

Dean’s Office, Boston University School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts, USA

Moshe Z. Abramowitz & Sandro Galea

Department of Health Services Research and Policy, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK

Moshe Z. Abramowitz, Bayard Roberts & Martin McKee

Harvard Program in Refugee Trauma, Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Cambridge, USA

Moshe Z. Abramowitz & Richard Mollica

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

JL drafted the manuscript together with MM. All authors contributed with methodological expertise to the project. All authors contributed in writing. All authors added content and specific examples. All authors discussed the guidelines and decided upon standards. Furthermore, Jl, HYL, MA and TV provided expertise in the field of mass trauma and epidemiology. All authors revised and edited the manuscript critically for important intellectual content of the material. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jutta Lindert .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

Bayard Roberts is co-Editor-in-Chief of Conflict and Health . He was not involved in handling this manuscript.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:.

Quality assessment tool for quantitative genocide studies. (DOCX 32 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Lindert, J., Kawachi, I., Knobler, H.Y. et al. The long-term health consequences of genocide: developing GESQUQ - a genocide studies checklist. Confl Health 13 , 14 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-019-0198-9

Download citation

Received : 04 July 2018

Accepted : 27 March 2019

Published : 11 April 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-019-0198-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Long term impact

- Quality criteria

- Mental health

Conflict and Health

ISSN: 1752-1505

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

Holocaust and Genocide Studies Scholarly Journal

The major forum for scholarship on the Holocaust and other genocides, Holocaust and Genocide Studies is an international journal featuring research articles, interpretive essays, book reviews, a comprehensive bibliography of recently published relevant works in the social sciences and humanties, and an annual list of major research centers specializing in Holocaust studies.

Articles compel readers to:

Confront many aspects of human behavior

Contemplate major moral issues

Consider the role of sciences and technology in human affairs

Reconsider important features of political and social organization

With content from the disciplines of history, literature, economics, religious studies, anthropology, political science, sociology, and others, Holocaust and Genocide Studies also prints work on other genocides and near-genocidal episodes. The journal is published three times a year in cooperation with Oxford University Press.

About the Journal

Current issue.

For information about the journal, including instructions for contributors as well as tables of contents and abstracts of articles going back to volume 1, number 1 (Spring 1986), please visit the Oxford Journals website . Subscribers have access to the entire journal online at Oxford Journals at no additional cost.

Additionally, journal content from 1996 (Volume 10) onward is available at a variety of EBSCO databases covering the fields of history, sociology, and Jewish studies; these are available via institutional subscription. For more information about how your institution can subscribe to these databases, please visit EBSCO Online Research Databases , which posts journal content a year after publication on the Oxford University Press website. Beginning with volume 17 (2003), articles are also available online from Project Muse .

To receive advance electronic notification of future journal contents, sign up for Oxford University Press' contents-alerting service —a free service available to subscribers and non-subscribers alike.

Read Online

Faculty and students can read Holocaust and Genocide Studies through their university’s digital library subscriptions services. Oxford University Press has provided access to five virtual issues and three special issues of the journal. If you are unable to access journal content, please contact Oxford University Press’s customer service team at [email protected] , and they will be able to assist you.

Request Subscriptions and Issues

All requests for Holocaust and Genocide Studies subscriptions, recent single issues, and two back volumes may be placed by telephone or fax using a major credit card. You can also find information about subscriptions and access for non-subscribers on a pay-per-view basis at Oxford Journals . Please contact:

In the Americas

Tel: 800-852-7323 (USA and Canada only) or Tel: 919-677-0977 Fax: 919.677.1714 Email: [email protected] Mail: Journals Customer Service Oxford University Press 2001 Evans Road Cary, NC 27513, USA

In the UK and Europe

Tel: +44 (0)1865 353907 Fax: +44 (0)1865 353485 Email: [email protected] Mail: Journals Customer Service Oxford University Press Great Clarendon Street Oxford OX2 6DP, UK

Tel: +86(0)10-8515-1678 Fax: +86(0)10-8515-1678-105 Email: [email protected] Mail: Oxford University Press, Beijing Office, Unit 1504A, Tower E2, Oriental Plaza Towers No. 1 East Chang An Avenue Dong Cheng District, Beijing, 100738, China

Tel: +81-3-5444-5858 Fax: +81-3-3454-2929 Email: [email protected] Mail: Journals Customer Service Department Oxford University Press 4-5-10-8F Shiba Minato-ku, Tokyo, 108-8386, Japan

Back Issues

Back issues previous to the two back volumes can be obtained from: Periodicals Service Company 351 Fairview Avenue, Suite 300, Hudson, NY 12534 E-mail: [email protected] Tel: 518.822.9300 Fax: 518.822.9302

The US Holocaust Memorial Museum’s Jack, Joseph, and Morton Mandel Center’s mission is to ensure the long-term growth and vitality of Holocaust Studies. To do that, it is essential to provide opportunities for new generations of scholars. The vitality and the integrity of Holocaust Studies requires openness, independence, and free inquiry so that new ideas are generated and tested through peer review and public debate. The opinions of scholars expressed before, during the course of, or after their activities with the Mandel Center are their own and do not represent and are not endorsed by the Museum or its Mandel Center.

This Section

The Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies is a leading generator of new knowledge and understanding of the Holocaust.

- Collections Search

- Scholar Commons

Scholar Commons > Open Access Journals > GSP

Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal (GSP) is the official journal of The International Association of Genocide Scholars (IAGS) . IAGS is a global, interdisciplinary, non-partisan organization that seeks to further research and teaching about the nature, causes, and consequences of genocide, and advance policy studies on prevention of genocide. IAGS, founded in 1994, meets to consider comparative research, important new work, case studies, the links between genocide and other human rights violations, and prevention and punishment of genocide.

GSP is a peer-reviewed journal that fosters comparative research, important new work, case studies, the links between genocide, mass violence and other human rights violations, and prevention and punishment of genocide and mass violence. The E-Journal contains articles on the latest developments in policy, research, and theory from various disciplines, including history, political science, sociology, psychology, international law, criminal justice, women's studies, religion, philosophy, literature, anthropology, and museology, visual and performance arts and history.

Current Issue: Volume 17, Issue 3 (2024)

Too Little, Too Late: The ICC and the Politics of Prosecutorial Procrastination in Georgia Marco Bocchese

A Personal Autobiographical Essay on the Origins and Beginning Years of Genocide Studies, and Some Reflections on the Field Today Israel W. Charny

- Journal Home

- About This Journal

- Ethics Guidelines

- Editorial Board

- Advisory Board

- Former Editors

- Active Calls

- Submission Guidelines

- Citation Quick Guide

- Submit Article

- Most Popular Papers

- Receive Email Notices or RSS

Special Issues:

- Environmental Degradation and Genocide

- Mass Atrocity and Collective Healing

- Critical Genocide and Atrocity Prevention Studies

Advanced Search

ISSN: 1911-0359 (Print) ISSN: 1911-9933 (Online)

- Follow GSP on: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn RSS

Supported by:

Scholar Commons | About this IR | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

Problems and Challenges in Genocidal Research

Cite this chapter.

- Elisabeth Hope Murray 2

Part of the book series: Rethinking Political Violence series ((RPV))

308 Accesses

All social scientists face challenges to discovering the answers to the questions they ask. As a genocide scholar, some of my challenges are unique to my field, but many are problems faced and overcome by scholars in various disciplines, showing once again that, though we deal with evil and hatred, we too are mere scholars. Thus, this first chapter simply reviews the challenges of my work - aside from the emotional and moral challenges - and looks at the theoretical and practical methods I have used to overcome them as best I can. Specifically, questions of ideological radicalisation in states moving towards genocide present two overarching problems. The first challenge is simply how to appropriately study ideology; the second challenge is how to appropriately compare cases across space and time.

God forbid that we should give out a dream of our own imagination for a pattern of the world.’ — Francis Bacon (1628: 15)

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Embry-Riddle University, Florida, USA

Elisabeth Hope Murray ( Assistant Professor of Security Studies and International Affairs )

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Copyright information

© 2015 Elisabeth Hope Murray

About this chapter

Murray, E.H. (2015). Problems and Challenges in Genocidal Research. In: Disrupting Pathways to Genocide. Rethinking Political Violence series. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137404718_2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137404718_2

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, London

Print ISBN : 978-1-349-48742-4

Online ISBN : 978-1-137-40471-8

eBook Packages : Palgrave Intern. Relations & Development Collection Political Science and International Studies (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

About Genocide

Narrow the topic.

- Articles & Videos

- MLA Citation This link opens in a new window

- APA Citation This link opens in a new window

- How is genocide different from mass murder? Or terrorism?

- How are genocide and other acts of mass violence humanly possible?

- What choices do people make that allow collective violence to happen?

- What makes it possible for neighbor to turn against neighbor?

- What are the different reasons sited for leading to genocide? (ie. poverty, religious or ethnic differences)

- Who decides if it is genocide or civil unrest?

- Is there any remedy for genocide?

- Can the United States take an active role in preventing genocide?

- Why do leaders scapegoat particular groups?

- Next: Library Resources >>

- Last Updated: Feb 6, 2024 3:59 PM

- URL: https://libguides.broward.edu/Genocide

Holocaust and Genocide Research Guide

- Find Articles

- Armenian Genocide

- Cambodian Genocide

- Central African Republic Conflict

- European Holocaust

- Guatemalan Genocide

- Nanjing Massacre

- Native American

- Rwandan Genocide

- South Sudan Civil War

- << Previous: Find Books

- Next: Armenian Genocide >>

- Last Updated: Jan 2, 2024 9:02 AM

- URL: https://libguides.unomaha.edu/holocaust

Search the Holocaust Encyclopedia

- Animated Map

- Discussion Question

- Media Essay

- Oral History

- Timeline Event

- Clear Selections

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Português do Brasil

Featured Content

Find topics of interest and explore encyclopedia content related to those topics

Find articles, photos, maps, films, and more listed alphabetically

For Teachers

Recommended resources and topics if you have limited time to teach about the Holocaust

Explore the ID Cards to learn more about personal experiences during the Holocaust

Timeline of Events

Explore a timeline of events that occurred before, during, and after the Holocaust.

- Introduction to the Holocaust

- Antisemitism

- How Many People did the Nazis Murder?

- Book Burning

- German Invasion of Western Europe, May 1940

- Voyage of the St. Louis

- Genocide of European Roma (Gypsies), 1939–1945

- The Holocaust and World War II: Key Dates

- Liberation of Nazi Camps

What have we learned about the risk factors and warning signs of genocide?

The study of the Holocaust raises questions about how the world can recognize and respond to indications that a country is at risk for genocide or mass atrocity. While each genocide is unique, in most places where genocide occurs, there are common risk factors and warning signs.

Explore this question to learn how to identify these signs in today's world, as well as how they were present during the Holocaust and other genocides.

See related articles for background information related to this discussion.

- warning signs

Risk Factors and Warning Signs

Genocides have continued to happen since the Holocaust. For example, genocide occurred in Rwanda in 1994, and at Srebrenica in Bosnia in 1995.

Every genocide is unique, but most genocides share some things in common. Just as there were key conditions that made the Holocaust possible, there are identifiable risk factors for genocide today. Some of the most common are:

- Instability : One of the strongest signs of the potential for genocide is large-scale instability. Instability can result from armed conflict or developments that threaten a regime’s power, such as a coup, revolution, or uprising. Instability may increase the risk of genocide for several reasons. Leaders may feel threatened, citizens may feel insecure, and the law may be suspended or neglected. In such environments, leaders and citizens may be more willing to consider violence to protect themselves and what they value.

- Ideology : Genocide often happens when leaders believe that some people in the country are inferior or dangerous because of their race, religion, or national or ethnic origin. In Rwanda, leaders of the Hutu majority believed that the Tutsi minority wanted to dominate the Hutus. In Bosnia, Serb leaders believed that the Muslim Bosniaks were a threat to the freedom and culture of the Orthodox Christian Serbs.

- Discrimination and violence against groups : Where genocide occurs, there usually have been earlier acts of discrimination, persecution, and violence against people who belong to a certain group. In Rwanda, Tutsis faced various forms of discrimination. There were several incidents of mass violence against Tutsis in previous decades. In addition, Bosnian Serb forces committed numerous war crimes and crimes against humanity against Bosniak and Croatian communities before committing genocide at Srebrenica.

The factors that can put a country at risk for genocide may exist for a long time without leading to genocide. Some of the warning signs that the risk for genocide may be increasing include:

- Dangerous speech : Before and during genocide, there is often widespread hate speech. Such hate speech promotes the idea that members of a certain group are evil and dangerous. When this speech comes from influential leaders and is spread through government propaganda or popular media, it can condition listeners to believe that violence against the group is justified. It may also incite some people to commit violence against members of the group. The leaders of genocide in Rwanda and Bosnia all promoted hate speech against the victims.

- Armed groups : Before committing genocide, leaders often create special groups that share their ideology and goals. For example, Hitler established the SS ( Schutzstaffel ; Protection Squadrons) in Germany in 1925. Leaders provide these groups with weapons and military training. They use them to commit violence against members of a particular group. During the Rwandan genocide, the Interahamwe militia led the killing in certain areas.

- Armed conflict : Genocide most often happens during armed conflict. The genocides in Rwanda and Bosnia happened during times of civil wars. The Holocaust and the genocide in Armenia occurred during international wars. Genocide can result if one or both sides of the armed conflict expands its targets from enemy soldiers to civilian groups seen as supporting the enemy. Mass atrocities against civilians who belong to a certain group can escalate violence and increase the risk for genocide by deepening hostility between groups. This can provoke acts of revenge, attract recruits to the warring sides, and provide leaders with an excuse to conduct an all-out attack on members of a group.

The specific factors that led to genocide in Europe, Rwanda, and Bosnia were very different. In each case, however, recognizable risk factors and warning signs were present. All those who organize and carry out genocide rely on the active help of countless officials and ordinary people as well as those who stand by, witness, and sometimes benefit from the persecution and murder of their neighbors.

Early Warning

Today, the international community makes efforts to watch for the risk factors and warning signs of genocide. Recognition of these signs can help the world act to prevent before killing begins. Because genocide usually occurs within the context of other mass atrocities, prevention efforts focus not only on genocide but also on the other acts defined as “atrocity crimes.” Genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity are today together commonly referred to as "atrocity crimes" or "mass atrocities."

As we learn more about the risk factors, warning signs, and triggering events that have led to genocide in the past, we are also learning ways to prevent it in the future. Designed by the Museum and Dartmouth College, the Early Warning Project gives us a first-of-its-kind tool to alert policy makers and the public to places where the risk for mass atrocities is greatest. Together, people around the world can call for action before it’s too late.

Related Articles: What is Genocide?

How Were the Crimes Defined?

What is Genocide?

Coining a Word and Championing a Cause: The Story of Raphael Lemkin

Introduction to the Definition of Genocide

Related articles: risk factors and warning signs.

Nazi Propaganda

Defining the Enemy

Incitement to Genocide in International Law

Related articles: cases, genocide timeline.

The Rwanda Genocide

Rwanda: The First Conviction for Genocide

Switch Topic

Critical thinking questions.

- How might citizens and officials within a nation identify and respond to warning signs? What obstacles might be faced?

- How might other countries and international organizations respond to warning signs within a nation? What obstacles may exist?

- How can knowledge of the events in Germany and Europe before the Nazis came to power help citizens today respond to threats of genocide and mass atrocity?

Thank you for supporting our work

We would like to thank Crown Family Philanthropies and the Abe and Ida Cooper Foundation for supporting the ongoing work to create content and resources for the Holocaust Encyclopedia. View the list of all donors .

Genocide Studies Program

Crimes against humanity.

A Crime Against Humanity has been defined as “a widespread or systematic attack directed against a civilian population.” Such crimes include the murder of political or social groups that are unprotected by the 1948 United Nations Genocide Convention. More …

Genocide, Comparative

Comparative genocide is a branch of genocide studies that seeks to identify differences and similarities across genocidal (and similarly situated non-genocidal) episodes, and thus to isolate some of the more essential features of genocide that recur in all or most cases. More …

Genocide, General

Considers themes that address the meaning, history, and occurrence of genocide. More …

GIS & Remote Sensing

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) make it possible to interrelate spatially multiple types of information assembled from a range of sources. Remote sensing is the measurement of object properties on Earth’s surface using data acquired from aircraft and satellites. More …

Justice & Prosecutions

The jurisprudence of genocide, at both the national and international levels. More …

Mass Atrocities in the Digital Era (MADE)

The MADE Initiative is at once a turn to the reality that much of the subject and methodology of genocide studies has undergone a dramatic change in the 21st Century and a return to the core princieples of the GSP and its roots within the Cambodian Gencoide Documentation Project. More …

Genocide scholarship is often motivated by the hope that future genocides can and will be prevented. Some of that work specifically analyzes the efforts and strategies to do so. More …

The GSP’s Rescue page is dedicated to documenting and publicizing acts of resistance, protest and rescue that combat genocidal injustice and violation of human rights. More …

Discussions and resources addressing domestic resistance to genocide specific locations. More …

The GSP and the Department of Psychiatry at Yale University co-sponsor the Holocaust Trauma Project, directed by Dr. Dori Laub. Dr. Laub, M.D. is a Clinical Professor of Psychiatry at the Yale University School of Medicine and a psychoanalyst in private practice in New Haven, Connecticut. His work on trauma includes studies of the multifaceted impact of the Holocaust on the lives of survivors and that of their children, as well as on survivors of the “ethnic cleansing” in Bosnia and of other genocides. More …

Truth Commissions

Truth Commissions hold an increasingly prominent place among the institutions of transitional justice that are employed in the wake of mass violence. Where implemented, they stand as an important – though inevitably imperfect – source of information about periods of mass violence (including genocide), as well as a barometer of post-conflict social reconstruction. More …

Examinations of violations of the laws of war in civil and international conflict, which may or may not overlap with genocide and/or crimes against humanity. More …

130 Genocide Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

🏆 best genocide topic ideas & essay examples, 💡 interesting topics to write about genocide, 📌 simple & easy genocide essay titles, 👍 good essay topics on genocide, ❓ genocide research questions.

- Holocaust and Bosnian Genocide Comparison The current paper aims to compare some of the most notable genocides in history, the Holocaust, and the Bosnian mass murder in terms of their aims, death tolls, tactics, and methods.

- Genocide Factors in Rwanda and Cambodia By the start of the last decade of the 20th Century, animosity between the Hutus and the Tutsis had escalated with the former accusing the latter of propagating socioeconomic and political inequalities within the country.

- Ethnic Cleansing and Genocide Another difference between the two terms is that genocide is the systematic and widespread destruction of particular segment of the population or specific group of people, ethnic cleansing on the other hand is understood as […]

- The Problem of East Timor Genocide To understand the peculiarities of genocide against the native people at the territories of East Timor, it is necessary to focus on examining such aspects as the causes for the genocide, the techniques used by […]

- Argumentative Essay: Uighur Genocide A total of 149 nations, including the United States, France, the United Kingdom, Russia, and China, ratified the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.

- The Global Impact of Genocide: The Socio-Economic and Political Spheres According to the 1948 United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide Article III, the following acts are punishable: “genocide, conspiracy to commit genocide; direct and public incitement to commit […]

- “Night” by Elie Wiesel: Holocaust and Genocide Given that the events are seen through the eyes of the young person, the major emphasis is placed upon the main character’s perception of the violence and death taking place around him and gradual loss […]

- The History of the Genocide in the Rwandan The Rwandan civil war led to the signing of the Arusha Accord that compelled the Rwandan government, which Hutu dominated, to form a government of national unity by incorporating marginalized Tutsi and the Hutu who […]

- Legal Standard of Genocide: The Enduring Problem From the perspective of the legal standard of genocide accepted in the world law, the events in Turkey correspond to the definition of the mass killing of one people by the other one.

- Genocide: Himmler and the Final Solution Genocide targets an individual’s identity to eliminate a group of people, in contrast to war, where the attack is generic, and the goal is frequently the control of a specific geographic or political region.

- Genocide Intervention and Prevention The question of what needs to be done in order to prevent and address genocide appears to be a challenging one. The notions of genocide intervention and prevention refer to efforts to protect individuals and […]

- Physical and Cultural Genocide Policy Toward Native Americans Thus, the US government pursued a two-pronged policy of physical and cultural genocide toward Native Americans to acquire their lands and, later, to suppress their resistance. The US government planned to civilize the Native Americans […]

- Nazism and Genocide as Social Evils The article by Jacob Tanner, “Eugenics Before 1945,” explores the interaction of science and social theory, mainly hereditary, used as the foundation for social improvement.

- Difficulties in Preventing the Occurrence of Genocide The 1994 Rwanda genocide that took place within the course of a hundred days was ethnic in nature as it involved a premeditated annihilation of the Tutsi minority by the Hutu government.

- Crimes Against Humanity – Genocide However, the most captivating event as the movie progresses is the reluctance of the international community to intervene to quell the raging storms.

- Armenian Genocide Overview According to Article II of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide of the United Nations, genocide is a process of killing members of a religious, racial, ethnic, and national […]

- Darfur: The New Face of Genocide The situation in Darfur raises new questions about events that constitute genocide as these crimes fit “uncomfortably within the definition of genocide”.

- Genocide: Darfur and Rwanda Cases When examining the case of Darfur, it can be noted that three specific factors prevented “true justice” from being administered, these encompass: the abstained votes from the U.S.and China in voting for a resolution for […]

- The Darfur Genocide 2003: What Really Happened in Sudan This creates a substantial factor in the realms of Darfur Genocide. Precisely, this research will involve problem development, research design, data collection, data compilation, data analysis, conclusion, and presentation of results to the concerned audience.

- Hotel Rwanda’: The 1994 Rwandan Genocide’s History Besides, the assassination of the 1994 president, who belonged to ethnic Tutsi, was one of the main causes; the Hutus accused the Tutsis of having been responsible for the president’s assassination.

- Investigating the Religious Motif in Genocide The research is focused on genocide of the Jews in Nazi Germany before and during the World War II and genocide of the Armenians in Ottoman Empire in 1915.

- Rwanda Genocide: “Shake Hands with the Devil” by Dallaire Romeo This paper will examine the issue in highlighting the theme that the main purpose of the book was to let the world know of its callousness and lack of precaution while the horrible and immoral […]

- Genocide in Darfur Region: The Actual Cause of Sudanese Genocide The true cause of Sudanese recent genocide in Darfur region is the same as were the causes for other genocides, which have taken place in Africa, after this continent has been liberated of “white oppression” […]

- Yanomami: The Gold Rush and Genocide The Yanomami of Brazil and Venezuela can be considered the arena of aggression and conflict in Amazon; this interaction resulted in the global tragedy taking the lives of the whole communities.

- Crime of Genocide: Justice and Ethical Issues The conflict was declared as genocide for the first time by the USA government, which gave a permit to ‘the UN Security Council to refer a case to the International Criminal Court.’ 2 Therefore, the […]

- Armenian Genocide and Spiegelman’s “Maus” Novel Tracing the similarities between the Holocaust and the Armenian Genocide is important to the discussion of Maus as a literary piece.

- Is Western Intervention in Genocides Justified? These include specific evidence of a crisis that is accepted by the global community, there is a lack of practical alternatives, and the use of force during the intervention must be limited to providing relief […]

- Genocide in Eastern Turkey An example of such events is the genocide and deportation of Armenians from the Ottoman Empire, since it ended in the numerous deaths; however, it was a victory for some people and a disaster for […]

- Civil Liberties vs. American Cultural Genocide Thus, when one group’s idea of the good life requires others to sacrifice their freedom, negative outcomes, such as protests or violent response, are inevitable.

- Genocide and the Right to Be Free The focus on the order is the main duty of a policeman even if the order is based on organizing the raid to find the red-haired men as the representatives of the minority.

- Virginia Holocaust Museum’s Genocide Presentation In terms of the educational objective, I aimed to learn the aspects and details of the Holocaust through the artifacts, objects, and things that belonged to people experiencing these events’ atrocities.

- Analysis of the Documentary ”Genocide” According to the documentary, genocide is the outcome of mass hysteria. After that, the international community will be able to have an impact on the decisions of political leaders.

- Genocide in the “Ghost of Rwanda” Documentary In the colonial process, the Hutus were discriminated by the colonial power, which was Belgium with the help of the Tutsi.

- Comparison of Genocide in Rwanda and Nazi Germany The proponents of the emancipation movement called the Rwandan Patriotic Front returned to the country in the fall 1990 to live within the population of Tutsi.

- Social Darwinism and Nazi Genocide Ideology It is possible to trace the way the Jews settled and assimilated in western countries and the way the ideas of Social Darwinism affected the society to see the link between Nazi genocidal ideology and […]

- Rwanda Genocide: Process and Outcomes It will describe the Tutsi-favored political system and land distribution system that contributed to the occurrence of the Genocide. The Europeans were of the opinion that the Tutsi did not originate from the region.

- Genocide’ Causes and Elimination Therefore, in this paper, we dwell on the theories and significant instances of genocide so that to prove that the global eradication of ethnicity is the payoff of psychological disparities both on a personal and […]

- Stories of Rwanda’s Recovery From Genocide Today, the killers and the victims of the genocide live side by side, and the government focuses on finding the effective measures and legacies to overcome the consequences of the genocide and to state the […]

- The Rwandan Genocide: Hutus and Tutsi Ethnic Hatred People have always believed that the ethnic hatred between the Hutus and the Tutsi was the core cause of the genocide.

- What Could Be Worse Than Death? Genocide Genocide is worse than death because of its horrific consequences, such as destruction of human life and the emotional and psychological trauma experienced by victims. Unlike the killing of the Jews and the Armenians, the […]

- The Genocide of East Timor As far as genocide was proclaimed an international crime, the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide was established. In our days, the execution of women is recognized to be one […]

- Australian Aborigines Genocide The rules and policies produced by the international laws state that as long as there is intent to systematically get rid of a group of people and there is the act itself, it is genocide.

- Human Sanctity: Darfur Crisis The writer recommends paying attention to the development of strategies for paying the compensation for the Darfur victims, dismantling systems of violence, supporting the United Nations African Union Mission in Darfur peace initiative and regulating […]

- In-class Reaction Paper: Rwandan Genocide The book offers a detailed description of the events that took place in the 1994 Rwandan genocide as told by the survivors of the massacre.

- Darfur Genocide Indicatively, this was before the period of the start of the Darfur genocide. Particularly, this relates to the development of the war within the area.

- Genocide in Rwanda: Insiders and Outsiders The paper will look into the Rwandese pre genocide history, factors that led to the genocide, the execution of the genocide and impacts of the genocide.

- The Concept of Genocide In recent past, daily media broadcasts were covered with terrible news of genocide going on in Bosnia-Herzegovina, genocide in Rwanda where more than one million people were killed by government forces as well as parliamentary […]

- Doris Bergen: Nazi’s Holocaust Program in “War and Genocide” The discussion of the Holocaust cannot be separated from the context of the World War II because the Nazi ideology of advancing the Aryans and murdering the undesirable people became one of the top reasons […]

- Sexual violence as a tool of genocide It is disgusting to observe the expert say that this act is a ‘cultural behavior’ and that it is amorally correct.’ The author does a good analysis by relating the origin of sexual violence and […]

- The Holocaust: A German Historian Examines the Genocide The Holocaust: A German Historian Examines the Genocide deals with one of the most debatable issues of the history of the twentieth century, i.e.

- The Consequences Of The Vietnam War And The Pol Plot Genocide

- The Bosnian Genocide in Behind Enemy Lines, a Movie by John Moore

- The Eight Stages of Genocide in Steven Spielberg’s Film Schindler’s List

- The Inhumanity of the Genocide During the Holocaust in Night, a Memoir by Elie Wiesel

- The Genocide And Its Impact On The World ‘s Existence

- The Ethnic Conflict Of The Rwandan Genocide

- The Role of the Catholic Churches in the Genocide of Rwanda

- The Six Stages of the Rwandan Genocide in Africa

- What Happened During The Armenian Genocide

- Truth About Christopher Columbus: The Man Behind a Genocide

- The Justification for Genocide, Terrorism, and Other Evil Actions

- The History of the Acts of Genocide in Cambodia by the Khmer Rouge

- The Stanford Prison Experiment Was Not A Physical Genocide

- The Rwandan Genocide and the Role of the United States in the Failure of the UN to Keep Peace in Rwanda

- Why the Holocaust in Considered Genocide

- The UN & US Mishandling Of The Rwandan Genocide

- The Path of Genocide: The Rwanda Crisis from Uganda to Zaire

- The Demographic and Socio-Economic Distribution of Excess Mortality during the 1994 Genocide in Rwanda

- Supporting the Investigation of Genocide, War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity

- The Representation of War and Genocide in The Farming of the Bones, a Book by Edwidge Danticat

- The Role of Colonial Influences in the 1994 Rwandan Genocide

- The Economic Effects of Genocide: Evidence from Rwanda

- Uncovering the Truth Behind the Armenian Genocide

- The Lack of Involvement by the Government and International Community in the Genocide in Darfur

- The Misconceptions and the Outside Influences of the Genocide in Cambodia

- The Ukrainian Genocide: The Worst Tragedies In Ukranian History

- Two Similar But Different Genocides: The Holocaust And Cambodian Genocide

- The Bosnian Genocide And How It Changed Society

- The Cruelty of Humans in the Rwandan Genocide, the Human Rights Broken, and Its Impact on Rwanda and the World

- The History of the Armenian Genocide after the Fall of the Ottoman Empire

- The Influence of Cultural Differences on the Development of Genocide

- The Main Factors That Influenced The Rwandan Genocide

- United Nations Role in Preventing Genocide in Africa

- Rwandan Genocide: Atheism and the Problem of Good

- The Mass Genocide Of The Republic Of Oceania Propaganda

- The Events in the Cambodian Genocide in Its Effects in Society

- The International Community and Its Lack of Actions in the Holocaust and the Armenian Genocide

- The Rwandan Genocide and Its Effects on Rwanda’s Society

- The Cambodian Genocide: A Tragedy Hidden from the World

- The Statistics of the Genocide in East Timor as of 1975

- The Tragedy Of The Armenian Genocide And The Holocaust

- The Holocaust and the Cambodian Genocide: Similar or Different?

- Similarities and Differences Between the Rwandan Genocide and the Holocaust

- Theme of Witch Hunts in The Crucible and the Rwandan Genocide

- The Hiroshima and Nagasaki Bombings. Genocide or Not

- The International Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide

- To What Extent Were Women’s Roles Affected By The Rwandan Genocide

- What Is The True Meaning Of Genocide

- The Ottomans And The Armenians: Casualties Of War Or Genocide

- Why Did the Government of Rwanda Perpetrate a Genocide in 1994?

- What Caused the Darfur Genocide?

- Was the Assimilation Policy for Native Austrians Cultural Genocide?

- Why Do Liberal Not Care About Genocide?

- What Caused the Rwanda Genocide?

- Why Was the Armenian Genocide Forgotten?

- How Does Racism Influence Genocide?

- Was the Main Reason for the Genocide in Cambodia?

- What Happened During the Armenian Genocide?

- Did the United Nations and the International Community Fail to Prevent the Rwandan Genocide?

- What Inspired Hitler and the Nazis to Start WWII and Attempt Genocide Against the Jews and Other Inferior Races?

- Were the English Colonists Guilty of Genocide?

- Was the Ukrainian Famine Genocide?

- How Does Kocide Affect the North Korean Genocide?

- Why Didn’t the United States Intervene to Prevent the Genocide in Rwanda?

- Did the British Commit Genocide in the Second Boer War?

- How Could Rwandan Genocide Be Justified?

- Why Was Nothing Done to Stop the Genocide in Rwanda?

- How Did Immaculee Ilibagiza Survive the Genocide?

- Why Did the Armenian Genocide Happen?

- How Has the Genocide Impacted Rwandan Society?

- What Does Genocide Mean?

- How Can the Holocaust Be Compared to One Other Form of Modern Genocide?

- Was Ethnic Hatred Responsible for the Rwandan Genocide of 1994?

- Were American Indians the Victims of Genocide?

- What Barriers Are There to the Effective Prevention of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity?

- When Did the Nazis Decide on Genocide?

- What Are the Political, Historical, and Social Contexts in Which Genocides Occur?

- In Which Genres and Through Which Channels Is Genocide Represented? And How So?

- What – If Any – Is the Connection Between Modernity and Genocide?

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, February 26). 130 Genocide Essay Topic Ideas & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/genocide-essay-topics/

"130 Genocide Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." IvyPanda , 26 Feb. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/genocide-essay-topics/.

IvyPanda . (2024) '130 Genocide Essay Topic Ideas & Examples'. 26 February.

IvyPanda . 2024. "130 Genocide Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." February 26, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/genocide-essay-topics/.

1. IvyPanda . "130 Genocide Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." February 26, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/genocide-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "130 Genocide Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." February 26, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/genocide-essay-topics/.

- Rwandan Genocide Research Ideas

- Auschwitz Research Topics

- Christopher Columbus Essay Topics

- Hiroshima Topics

- Holocaust Titles

- Mao Zedong Research Topics

- Nuclear Weapon Essay Topics

- Trail Of Tears Essay Ideas

HIST W335 History of Genocide

- Finding Books

- Armenian Genocide

- Rwandan Genocide

- Primary Sources for Other Genocides

- Develop a Research Question

- Primary Sources

- Cite Sources

- Scholarly vs Popular

- Thesis Statements

- Help! This link opens in a new window

What Is a Thesis?

A thesis is the main point or argument of an information source. (Many, but not all, writing assignments, require a thesis.)

A strong thesis is:

- Arguable: Can be supported by evidence and analysis, and can be disagreed with.

- Unique: Says something new and interesting.

- Concise and clear: Explained as simply as possible, but not at the expense of clarity.

- Unified: All parts are clearly connected.

- Focused and specific: Can be adequately and convincingly argued within the the paper, scope is not overly broad.

- Significant: Has importance to readers, answers the question "so what?"

Crafting a Thesis

Research is usually vital to developing a strong thesis. Exploring sources can help you develop and refine your central point.

1. Conduct Background Research.

A strong thesis is specific and unique, so you first need knowledge of the general research topic. Background research will help you narrow your research focus and contextualize your argument in relation to other research.

2. Narrow the Research Topic.

Ask questions as you review sources:

- What aspect(s) of the topic interest you most?

- What questions or concerns does the topic raise for you? Example of a general research topic: Climate change and carbon emissions Example of more narrow topic: U.S. government policies on carbon emissions

3. Formulate and explore a relevant research question.

Before committing yourself to a single viewpoint, formulate a specific question to explore. Consider different perspectives on the issue, and find sources that represent these varying views. Reflect on strengths and weaknesses in the sources' arguments. Consider sources that challenge these viewpoints.

Example: What role does and should the U.S. government play in regulating carbon emissions?

4. Develop a working thesis.

- A working thesis has a clear focus but is not yet be fully formed. It is a good foundation for further developing a more refined argument. Example: The U.S. government has the responsibility to help reduce carbon emissions through public policy and regulation. This thesis has a clear focus but leaves some major questions unanswered. For example, why is regulation of carbon emissions important? Why should the government be held accountable for such regulation?

5. Continue research on the more focused topic.

Is the topic:

- broad enough to yield sufficient sources and supporting evidence?

- narrow enough for in-depth and focused research?

- original enough to offer a new and meaningful perspective that will interest readers?

6. Fine-tune the thesis.

Your thesis will probably evolve as you gather sources and ideas. If your research focus changes, you may need to re-evaluate your search strategy and to conduct additional research. This is usually a good sign of the careful thought you are putting into your work!

Example: Because climate change, which is exacerbated by high carbon emissions, adversely affects almost all citizens, the U.S. government has the responsibility to help reduce carbon emissions through public policy and regulation.

More Resources

- How to Write a Thesis Statement IU Writing Tutorial Services

- Tips and Examples for Writing Thesis Statements Purdue OWL

- << Previous: Scholarly vs Popular

- Next: Help! >>

- Last Updated: Jan 31, 2024 9:19 AM

- URL: https://guides.libraries.indiana.edu/w335

Social media

- Instagram for Herman B Wells Library