An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Endocrinol

- v.2015; 2015

An Overview of Diabetes Management in Schizophrenia Patients: Office Based Strategies for Primary Care Practitioners and Endocrinologists

Aniyizhai annamalai.

1 Departments of Psychiatry and Internal Medicine, Yale School of Medicine, 34 Park Street, New Haven, CT 06519, USA

2 Department of Psychiatry, Yale School of Medicine, 34 Park Street, New Haven, CT 06519, USA

Diabetes is common and seen in one in five patients with schizophrenia. It is more prevalent than in the general population and contributes to the increased morbidity and shortened lifespan seen in this population. However, screening and treatment for diabetes and other metabolic conditions remain poor for these patients. Multiple factors including genetic risk, neurobiologic mechanisms, psychotropic medications, and environmental factors contribute to the increased prevalence of diabetes. Primary care physicians should be aware of adverse effects of psychotropic medications that can cause or exacerbate diabetes and its complications. Management of diabetes requires physicians to tailor treatment recommendations to address special needs of this population. In addition to behavioral interventions, medications such as metformin have shown promise in attenuating weight loss and preventing hyperglycemia in those patients being treated with antipsychotic medications. Targeted diabetes prevention and treatment is critical in patients with schizophrenia and evidence-based interventions should be considered early in the course of treatment. This paper reviews the prevalence, etiology, and treatment of diabetes in schizophrenia and outlines office based interventions for physicians treating this vulnerable population.

1. Introduction

People with schizophrenia have an increased risk of diabetes and other metabolic abnormalities. A renewed interest in this phenomenon has been sparked by the adverse metabolic effects of antipsychotic medications used in the treatment of schizophrenia. It is now well established that people with serious mental illness (SMI), including schizophrenia, have excess morbidity and mortality leading to a reduced lifespan of 20–25 years compared with the rest of the population [ 1 , 2 ]. The increased mortality is largely attributable to physical illness, including metabolic abnormalities and cardiovascular disease, rather than factors that are directly associated with psychiatric illness such as suicide or homicide. Metabolic syndrome occurs in one in three patients and diabetes in one in five patients [ 3 ]. These abnormalities not only confer an elevated cardiovascular risk and increased mortality in those with schizophrenia and other mental illness [ 4 ], but also are associated with poor psychiatric and functional outcomes [ 5 ].

For many people with schizophrenia and other serious mental illness, the mental health center is the primary point of contact with the health care system [ 6 ]. But there are multiple barriers to adequate screening and treatment at the mental health centers [ 7 ]. Referrals to community medical providers are challenging, in part due to administrative barriers, lack of communication between mental health and primary care practitioners and clinics, and also poor patient experience in medical settings. For patients with schizophrenia, psychiatric symptoms and cognitive deficits limit their social functioning and a fast paced medical health care environment is difficult to navigate. In one survey, these patients cited continuity of care and listening skills as qualities important in medical practitioners [ 8 , 9 ].

Patients with SMI are usually on treatments that include psychopharmacologic agents, psychotherapy, and other social interventions. Antipsychotics are a cornerstone of treatment in those with schizophrenia. A category of agents, known as second-generation antipsychotics, have been used since the early 1990s and in the last two decades there has been a tremendous increase in use of these medications [ 9 ]. These agents are now known to contribute significantly to obesity and metabolic syndrome, though there are variations in magnitude of risk between individual agents [ 10 ]. This, along with the increased smoking rates seen in people with schizophrenia, results in an increased cardiovascular risk and ultimately leads to worsened mortality rates [ 4 , 11 ].

In spite of increased awareness among mental health providers of the increased prevalence of metabolic syndrome in SMI, rates of screening and treatment remain poor [ 12 ]. The mortality gap between this patient group and the rest of the population, largely due to medical illnesses, has not narrowed [ 13 ]. Primary care providers already have the specialized medical knowledge necessary to treat medical conditions in those with schizophrenia. Increased awareness among medical providers of the high medical morbidity and mortality in schizophrenia is critical. Skills of primary care such as empathic listening, targeted education, continuity of care, and care coordination with mental health providers all have the potential to significantly improve the health of patients with schizophrenia.

2. Prevalence of Diabetes Diagnosis and Treatment in Schizophrenia

The rate of metabolic syndrome and diabetes in patients with schizophrenia is higher than the general population. A meta-analysis of several studies comprising over 25,000 patients with schizophrenia and related disorders showed an overall rate of metabolic syndrome at 32.5% and hyperglycemia at 19% [ 3 ].

A large multisite study, the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE), examined the effectiveness of different antipsychotic medications in over 1400 patients with schizophrenia. In addition to psychiatric outcomes, the study also examined physical health indicators. Metabolic syndrome was seen in more than 40% of patients. Diabetes was seen in 11% of patients and fasting glucose levels >100 mg/dl were seen in more than 25% of patients in this study. Rates of treatment for metabolic syndrome were low with more than 30% of patients with diabetes not receiving treatment [ 12 ].

The prevalence of diabetes in schizophrenia has been estimated to be 2-3-fold higher than in the general population and estimates of prevalence range from 10 to 15% [ 14 ]. In a study of over 400 patients with schizophrenia, the prevalence of diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance was 6.3% and 23.4%, respectively, in the total sample [ 15 ]. Diabetes prevalence was 4-5 times higher within each age group. The difference in diabetes prevalence between those with schizophrenia and the general population rose linearly with age from 1.6% in the 15–25 age group to 19.2% in the 55–65 age group. Interestingly, while the prevalence of metabolic syndrome is higher in those with schizophrenia, the increase in prevalence with age is the same as the general population. This suggests that the development of diabetes in schizophrenia is not solely secondary to metabolic syndrome but there may also be an inherent vulnerability to diabetes, possibly aggravated by pharmacological effects of some antipsychotics [ 16 ].

A large number of patients with schizophrenia and other SMI receive their psychiatric care at specialized mental health settings. A national screening program of 10,084 patients over several of these centers showed 37% of patients with schizophrenia had an elevated fasting glucose (>100 mg/dl) [ 17 ]. The rates of treatment were low, even among those with known diabetes. Approximately 40% of patients with schizophrenia and diagnosed diabetes reported not receiving any antihyperglycemics. This corroborates with the low rates of treatment seen in the CATIE study.

3. Etiology of Development of Diabetes in Schizophrenia

A link between schizophrenia and diabetes has been known for over a century, long before the use of antipsychotic medications. There is debate about the degree of contribution of genetics and environmental factors to development of diabetes.

Epidemiological studies show an increased risk of developing diabetes in people with schizophrenia with and without antipsychotics [ 18 ]. Some studies of people with antipsychotic naïve, first episode schizophrenia show impaired glucose tolerance and higher insulin resistance compared to healthy cohorts [ 19 ].

There is also evidence that antipsychotics increase metabolic risks, with second-generation agents showing differentially higher risk over time compared to first generation agents [ 20 ]. A recent comparative meta-analysis of metabolic abnormalities among unmedicated and first episode patients with schizophrenia showed a comparable rate with the general population [ 21 ]. These rates were much lower when compared with people with chronic schizophrenia established on medications. This would imply that most, if not all, the metabolic risk in schizophrenia patients is conferred by antipsychotic agents.

As can be seen, the data on the extent to which antipsychotics confer metabolic risk are conflicting. The relative contributions of genetic susceptibility and antipsychotic treatment to increased prevalence of diabetes are uncertain. The following sections review briefly some mechanisms postulated to explain the association of diabetes with schizophrenia.

3.1. Genetic Susceptibility to Diabetes

A common inherited susceptibility to both diabetes and schizophrenia has been postulated based on the observation that diabetes is more common in family members of those with schizophrenia [ 22 ]. A common genetic linkage between the two diseases has been suggested. Some authors report abnormal glucose metabolism and insulin signaling in the brain of those with schizophrenia [ 19 , 23 ]. Genes involved in both glucose metabolism and cognitive function may increase the risk of diabetes in schizophrenia patients. There is also a suggestion of a common molecular mechanism underlying both cognitive deficits such as working memory and glucose metabolism [ 23 ].

3.2. Neuroendocrine Pathways Increasing Diabetes Risk

Some studies have reported dysregulation of the hypothalamic pituitary axis and high serum cortisol levels in people with schizophrenia. Elevated serum cortisol increases gluconeogenesis, insulin resistance, and symptoms of metabolic syndrome. It is hypothesized that the elevated cortisol also increases serum leptin levels with a resultant increase in appetite [ 24 ]. Some authors have also implicated nutritional factors in a common pathway for development of both diabetes and schizophrenia [ 25 ]. For example, a low level of vitamin D during childhood may be associated with schizophrenia and vitamin D may affect insulin response to glucose stimulation [ 26 ]. Gestational zinc deficiency has also been proposed as a possible mediator of a common etiologic pathway [ 27 ].

3.3. Antipsychotics and Risk of Diabetes

Antipsychotics lead to weight gain and a higher risk of obesity related complications including diabetes [ 20 ]. The metabolic effects on glucose and insulin metabolism between agents within each class of antipsychotics are different [ 28 ]. Second-generation or atypical antipsychotics had three times the rate of new onset metabolic syndrome compared to first generation or typical or conventional antipsychotics after three years on medications [ 20 ]. At the three-year follow-up, impaired fasting glucose was more frequent in those treated with the second-generation agents. But the difference between the two groups of agents was not significant when clozapine and olanzapine were excluded from the analysis. Both clozapine and olanzapine are second-generation antipsychotics.

In a large meta-analysis comprising 25,992 patients, one in five patients with schizophrenia had hyperglycemia; the rate of metabolic syndrome was 51.9% for clozapine, 28.2% for olanzapine, and 27.9% for risperidone [ 3 ]. Risperidone is also a second-generation agent.

These medications cause weight gain by multiple mechanisms mediated by their effect on hypothalamic regulation and action on dopaminergic, serotoninergic, and histaminergic receptors [ 29 ]. The resulting obesity is a risk for hyperglycemia but antipsychotics can also directly cause diabetes. One postulated mechanism is the ability of antipsychotics to block the pancreatic muscarinic (M3) receptor. Leptin resistance is another proposed mechanism.

3.4. Nonmedication Environmental Factors

It is well known that patients with schizophrenia and other serious mental illnesses have unhealthy lifestyles with poor diets and inadequate physical activity [ 30 – 33 ]. This places them at higher risk of obesity and other metabolic complications. Factors that contribute to poor access to healthy lifestyle choices in individuals with schizophrenia are lower socioeconomic status, lower educational level, living situation (residential settings and living in areas with abundance of fast food facilities), and social isolation. Symptoms of schizophrenia such as low motivation, apathy, and cognitive deficits also could play a role in preventing access to healthy lifestyles. Patients with schizophrenia are also much more likely to be dependent on tobacco [ 34 ] and this further increases risk for cardiovascular disease. The following is a summary of the proposed common pathways between the two disease conditions.

Relationship between Diabetes and Schizophrenia

- higher occurrence of diabetes in family members of schizophrenia patients [ 22 ],

- abnormal glucose metabolism in schizophrenia patients [ 19 , 23 ],

- common mechanism proposed for cognitive deficit and glucose metabolism [ 23 ].

- hypothalamic axis dysregulation and elevated cortisol in schizophrenia [ 24 ],

- nutritional deficiencies proposed as common pathway for both diseases [ 25 – 27 ].

- effect on hypothalamic regulation, dopaminergic, serotonergic, and histaminergic receptors [ 29 ],

- other proposed mechanisms: action on pancreatic muscarinic receptor and leptin resistance [ 29 ].

- poor diet and lack of access to quality foods [ 30 – 32 ],

- inadequate physical activity due to symptoms and social isolation [ 30 , 31 , 33 ].

4. Treatment of Diabetes in Schizophrenia

Developing effective treatment programs for diabetes care is imperative for people with schizophrenia. See Table 1 for a summary of recommendations for diabetes management in these patients. As seen above, they are at risk not simply for diabetes but also for other metabolic conditions that lead to increased cardiovascular risk and mortality. The first step in diabetes management is prevention.

Special considerations for diabetes treatment in schizophrenia patients.

Prevention of obesity is an important part of preventing diabetes in schizophrenia patients as in the general population. Comprehensive programs to improve diet and physical activity of people with schizophrenia and other mental illnesses have been shown to be effective for clinically significant weight loss [ 35 ] as well as metabolic parameters. One program showed a greater decline in fasting blood sugars compared to controls [ 36 ]. Evidence has shown that for these programs to be effective they have to be of longer duration, include both education and activity within group settings, and include both nutrition and physical activity components. Manualized programs may be more successful than unstructured interventions. Individual clinicians can also provide office based counseling with specific targets for behavior change and periodic monitoring of weights and metabolic parameters [ 37 ]. This should happen at both the primary care site and the psychiatrist's office.

Another key strategy in preventing diabetes is periodic monitoring of patients. Most expert recommendations argue for frequent monitoring of metabolic parameters in those with schizophrenia [ 38 ]. These patients should be considered high risk regardless of age and presence of other risk factors. A targeted approach to screening should be employed in all patients, but frequency of screening will need to be higher in those on antipsychotics. In this particular patient population, adherence and follow-up may be an issue and so glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) may be preferable to a fasting glucose level as a screening test. For those on antipsychotics, screening should be done at baseline and then at 3-month intervals. If the HbA1c levels remain stable, screening can be reduced to 6-month or 1-year intervals.

Primary care physicians should also confer with the treating psychiatrist when a patient with schizophrenia gains excessive weight or develops glucose intolerance. The treating psychiatrist may not be aware of the development of glucose intolerance and other metabolic abnormalities. Also, the psychiatrist may be able to change the antipsychotic medication if the patient is on an agent that has a high risk of causing obesity and diabetes. Among antipsychotic agents, ziprasidone has shown to be the least likely to cause significant weight gain and should be considered in all patients [ 39 ]. Aripiprazole and other antipsychotics such as perphenazine, fluphenazine, and haloperidol can be considered as second line agents to switch to for attenuation of weight gain. As described above, clozapine and olanzapine are the antipsychotics most likely to cause weight gain as well as hyperglycemia and other metabolic complications. Risperidone and quetiapine are next in line in terms of likelihood of causing obesity and diabetes. While every attempt should be made to switch to an antipsychotic agent with lower metabolic risks, it should be remembered that the metabolic abnormalities are not always reversible with cessation of the offending agent. Also clozapine represents a special case since its use is limited to patients who failed other antipsychotics; thus a switch out of clozapine may not be possible.

Many pharmacologic agents have been studied in patients with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders to prevent or reverse the weight gain and metabolic abnormalities found in patients treated with antipsychotic medications [ 40 ]. Metformin is a promising agent as it has the potential for modest weight loss and improves insulin sensitivity and glucose regulation. The Diabetes Prevention Study showed that, in the general population, metformin is effective in preventing conversion to diabetes in those with impaired glucose tolerance but less effective than lifestyle interventions aimed at improving eating and physical activity behavior [ 41 ].

In people on antipsychotics, metformin has been studied for both prevention and treatment of antipsychotic-induced weight gain. It has been shown to be effective in attenuating weight gain on antipsychotics and improving glucose regulation [ 42 , 43 ]. Olanzapine is the most commonly studied antipsychotic in the metformin trials. In a sample of patients with chronic schizophrenia on olanzapine, metformin was effective in reducing both weight and HbA1c levels [ 44 ]. The weight loss compared to placebo was modest at 2 kg, which is similar to weight loss observed with metformin in the general population. In another cohort of patients who were early in the course of schizophrenia, metformin was superior to lifestyle interventions but combined intervention was superior to either intervention alone [ 45 ]. Mean reduction in body mass index (BMI) was about 1.8 in the group that received both metformin and lifestyle interventions compared to an increase in BMI of 1.2 in the placebo group. The fasting glucose decreased by a mean of 7.2 mg/dl in the metformin and lifestyle interventions group while it increased by 1.2 mg/dl in the placebo group. Metformin has also shown efficacy in improving weight and metabolic profile in patients on clozapine [ 46 ].

Thus, metformin has shown efficacy in improving glucose regulation in those with schizophrenia, though the effect sizes are small as in the general population. It should be considered early in the course of illness in all patients with schizophrenia who are obese and have evidence of glucose dysregulation, even if they are not on antipsychotics. However, given that the reductions in weight and glucose are small, metformin is only one step in the treatment of those with glucose intolerance.

The bulk of the data on metabolic abnormalities and antipsychotics is on weight gain related to these agents. Besides metformin, topiramate, an anticonvulsant, has shown some success in treating antipsychotic related weight gain [ 47 ]. Some prominent side effects such as cognitive impairment may be a deterrent for its use in schizophrenia. Other available weight loss agents such as orlistat, lorcaserin, and naltrexone/bupropion combination have not been adequately studied in the schizophrenia population. None of these agents affect glucose metabolism. Thus it is not clear if they can prevent conversion to diabetes. Other novel agents used for treatment of diabetes are being studied for diabetes prevention in prediabetic patients. However, the potential benefits both in the general population and in those with schizophrenia are unknown at this time.

Diabetes care in those with schizophrenia should be intensive and started early. As in all patients, the primary goal is to prevent long-term complications. Patients with schizophrenia have multiple other cardiovascular risk factors. Other conditions such as tobacco dependence and hypertension should be aggressively treated. Obstructive sleep apnea is another cardiovascular risk factor that is highly prevalent in this population [ 48 ]. As outlined above, diet and exercise measures can be effective and patients should be referred to a structured treatment program, if available. At a minimum, they should be referred to a nutritionist for specific recommendations on dietary modifications for managing diabetes.

At all stages of prevention and treatment, providers should communicate with family members or other caregivers. In patients with schizophrenia, issues of adherence and follow-up may be even more problematic than in the general population. Due to psychiatric symptoms and cognitive deficits, longer visits and simplified explanation of recommendations may be necessary. The long-term risks of poorly treated diabetes, including increased mortality, should be clearly delineated. Providers should also recognize that symptoms such as paranoia or delusions might interfere with adherence to recommendations. For this reason, providers should arrange for frequent follow-up visits, especially in initial stages of treatment. Providers will also need to coordinate care with specialists for routine diabetes care such as visits for a fundoscopic eye exam.

Adequate hygiene may be a problem in some patients and so special attention should be paid to foot care. They may not report neuropathic symptoms readily and a foot exam should be done at every visit. In the event of vascular complications with development of a diabetic ulcer, wound care should be aggressive with close follow-up. Poor dentition is frequently seen in these patients and efforts should be made to obtain dental evaluation and treatment to prevent gingivitis and other infectious complications. Sexual dysfunction, which can result from diabetes, can also be due to antipsychotic treatment. These medications affect sexual function through multiple mechanisms including elevated prolactin levels. Similarly, gastroparesis, a complication of diabetes, can also result from anticholinergic medications that are often used to combat adverse effects of antipsychotics.

Attention should also be paid to psychotropic medications that can cause chronic kidney disease. Lithium is a mood stabilizer used in patients with schizophrenia and coexisting mood disorder. Long-term treatment with lithium is associated with a range of glomerular and tubular disorders resulting in chronic kidney disease and rarely renal failure [ 49 ]. Potential interactions between psychotropics and agents used to treat diabetes and comorbid hypertension and hyperlipidemia should also be taken into consideration [ 50 ].

It is worthwhile to note that some antipsychotic medications, especially quetiapine and olanzapine, have been associated with acute onset of hyperglycemia and ketoacidosis [ 51 ]. Cognitive dysfunction associated with elevated glucose levels may be mistaken for the patient's baseline cognitive deficit resulting in delay in detection of hyperglycemia.

Other measures to prevent and treat comorbidities, such as use of aspirin and preventive immunizations, should be based on current evidence-based guidelines, as with any diabetic patient.

Antidiabetic agents with lesser likelihood of weight gain should be used whenever possible, since these patients are already on psychotropic medications that cause weight gain. If they are on medications that can cause hypoglycemia, very specific recommendations on immediate management should be provided to both patients and caregivers. Similarly, if self-monitoring with finger stick glucose measurements is necessary, caregivers may have to be involved for those patients with significant impairments. The frequency of glucose self-monitoring should also be tailored to the patient's capabilities. Target HbA1c goals should be individualized. The cardiovascular benefits of intensive glucose control should be balanced against the risks of hypoglycemia and the capacity of the patient to self-manage this complication of treatment. Providers should be flexible in tailoring treatment goals to each individual patient.

If aggressive lifestyle interventions and pharmacotherapy are inadequate to achieve target glucose levels and insulin administration becomes necessary, the insulin regimen should be kept as simple as possible. A basal insulin regimen offers the benefit of lesser risk of hypoglycemia. But in those whose level of hyperglycemia warrants additional prandial insulin, a premixed insulin regimen may be simpler to administer. Tight glucose control may not be possible in all patients. For any insulin regimen, patients should receive specialized nursing education and this may have to be delivered over multiple sessions. Home nursing services can be arranged in areas where such resources are available. Family members and caretakers can be trained in supervising or administering finger-stick glucose measurements and insulin injections. Depending on the practice setting, the treating psychiatrist may be able to assist with arranging for specialized services in the community, such as additional case management or nursing services. Coordination of care with the psychiatrist is of paramount importance.

Finally, bariatric surgery should be considered in patients with severe obesity with or without diabetes. It has been shown to improve diabetes measures beyond what is expected with weight loss in the general population [ 52 ]. Studies of bariatric surgery in patients with schizophrenia are lacking. However, bariatric surgery is effective in patients with bipolar disorder and psychiatric outcomes are not worse [ 53 , 54 ]. Therefore, patients with serious mental illness, if selected and managed appropriately, can be good candidates for bariatric surgery. Patients with schizophrenia should not be denied the procedure solely on account of their mental illness. In those who have failed other measures, it may be the only treatment option, especially in severely obese patients with coexisting diabetes.

5. Conclusion

Patients with schizophrenia represent a high-risk population for developing diabetes. The etiology is multifactorial and is a combination of genetic susceptibility, common biologic pathways, environmental factors, and treatment with antipsychotic medications. In spite of increased awareness of the high cardiovascular morbidity and early mortality in this population, rates of screening and treatment remain low. These patients often do not engage adequately in treatment with their primary care providers. An appropriate treatment milieu should be provided to better engage patients in treatment. A key strategy in preventing and treating diabetes and other components of metabolic syndrome should be prevention. Patients with schizophrenia should be seen and evaluated periodically to screen for diabetes and other cardiovascular risk factors. Aggressive lifestyle interventions should be employed for those with obesity and prediabetes or diabetes. Metformin has potential for attenuating weight gain and preventing diabetes and should be considered early in at-risk patients. Pharmacologic measures and bariatric surgery can be as effective in the schizophrenia population as in the general population. However, psychiatric symptoms or cognitive deficits often interfere with optimal diabetes care in these patients and primary care providers should pay special attention to their individualized needs. Providers should collaborate with treating psychiatrists to optimize both medical and psychiatric treatment to prevent the early mortality seen in this vulnerable population.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests to declare in the publication of this paper.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 23 March 2012

Effective lifestyle interventions to improve type II diabetes self-management for those with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder: a systematic review

- Adriana Cimo 1 ,

- Erene Stergiopoulos 1 ,

- Chiachen Cheng 1 , 2 ,

- Sarah Bonato 3 &

- Carolyn S Dewa 1 , 4

BMC Psychiatry volume 12 , Article number: 24 ( 2012 ) Cite this article

16k Accesses

53 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

The prevalence of type II diabetes among individuals suffering from schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorders is more than double that of the general population. By 2005, North American professional medical associations of Psychiatry, Diabetes, and Endocrinology responded by recommending continuous metabolic monitoring for this population to control complications from obesity and diabetes. However, these recommendations do not identify the types of effective treatment for people with schizophrenia who have type II diabetes. To fill this gap, this systematic evidence review identifies effective lifestyle interventions that enhance quality care in individuals who are suffering from type II diabetes and schizophrenia or other schizoaffective disorders.

A systematic search from Medline, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and ISI Web of Science was conducted. Of the 1810 unique papers that were retrieved, four met the inclusion/exclusion criteria and were analyzed.

The results indicate that diabetes education is effective when it incorporates diet and exercise components, while using a design that addresses challenges such as cognition, motivation, and weight gain that may result from antipsychotics.

Conclusions

This paper begins to point to effective interventions that will improve type II diabetes management for people with schizophrenia or other schizoaffective disorders.

Peer Review reports

In 2005, the World Health Organization (WHO) predicted that the prevalence of type II diabetes will double by 2030, to affect 366 million people globally [ 1 ]. Consequently WHO developed an action plan to increase access to type II diabetes healthcare by 2013 [ 2 ]. The increasing rate of this chronic illness is a concern because when glucose (sugar) cannot be absorbed by vital organs, glucose remains in the bloodstream. This leads to persistently high blood glucose levels, which is used as an indicator in diabetes management. Consistently high blood glucose is linked to complications such as cardiovascular disease, blindness, neuropathy, kidney failure, and poor wound healing resulting in infection that may lead to amputation [ 3 ].

Not everyone is at equal risk for the development of this chronic illness. Individuals suffering from schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders are at a greater risk of type II diabetes, with prevalence rates reaching more than two times those of the general population [ 4 – 6 ]. While it has been reported that people with schizophrenia may be genetically predisposed to type II diabetes, several other risk factors could contribute to the development of type II diabetes among people with schizophrenia [ 7 ]. Some antipsychotic medications such as olanzapine and clozapine, can cause side effects that promote the onset of type II diabetes [ 8 – 10 ]. These side effects include weight gain, dyslipidemia, hypertension, cardiovascular disease and decreased glucose tolerance [ 4 , 6 , 11 ]. Furthermore, El-Mallakh [ 6 ] observed that poorer health is exacerbated due to high rates of unemployment and reliance on social support, often leaving patients without financial resources to follow dietary guidelines.

Between 2004 and 2005, the debilitating health challenges associated with schizophrenia were recognized by the American Psychiatric Association (APA), American Diabetes Association (ADA), Canadian Diabetes Association (CDA), American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE), and the North American Association for the Study of Obesity (NAASO) [ 4 , 12 ]. These professional associations recommended continuous metabolic monitoring as a strategy to both prevent and diagnose type II diabetes [ 4 ]. Additionally, the need for interdisciplinary care incorporating psychiatrists, psychiatric nurses, family physicians, and diabetes specialists was recognized in response to the complexity of these combined illnesses [ 12 ]. However, effective treatment was not included for people with schizophrenia who have type II diabetes.

Given the risk of diabetes-related complications, the ADA and the CDA recommend that all individuals with type II diabetes be provided with Diabetes Self-Management Education (DSME) to successfully control their blood sugar [ 13 , 14 ]. Although DSME that incorporates lifestyle interventions are employed for the general population with type II diabetes, such programs are rarely offered to people who experience schizophrenia and who have type II diabetes. This is reflective of the fact that this population receives poorer diabetes care compared to those without severe mental illness [ 15 , 16 ]. Goldberg et al. [ 15 ] found that the frequency of screening and monitoring exams, such as tests for glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), eye examinations, and identifying serum fat levels, were not meeting the ADA's and CDA's recommendations. Individuals with schizophrenia were also less likely to receive diabetes education. Dickerson et al. [ 17 ] found that 48% of participants with severe mental illness had not received diabetes education within the last 6 months. As a result, this population experiences higher rates of hospitalization for hyper or hypoglycaemic episodes, and for infections [ 18 ].

Taken together, suboptimal diabetes care quality and the absence of effective treatment recommendations for people who have type II diabetes and schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorders is contributing to a life expectancy that is 20% lower than the general population [ 18 , 19 ]. In response to the need for evidence on this topic, this systematic evidence review (SER) will identify effective lifestyle interventions that enhance quality care in individuals who have type II diabetes and schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorders. Thus, the results from this review can be used to improve type II diabetes management, thereby reducing the burden on the healthcare system from the complications associated with chronically high blood glucose.

Literature search

Electronic searches using Medline, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and ISI Web of Science databases were conducted on June 15, 2011. The search strategies, which are presented in Table 1 , were developed in consultation with SB, a librarian scientist. The literature search yielded the identification of 1810 possibly eligible studies. From these, 920 abstracts were retrieved from Medline, 411 from PsycINFO, 88 from CINAHL and 391 from ISI Web of Science.

Eligibility assessment

Each title and abstract was independently screened by AC and ES in accordance with the following inclusion criteria that was developed a priori: i) study participants must have a medical diagnosis of both type II diabetes and schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, ii) the intervention must target a lifestyle factor associated with diabetes self-care, such as problem-solving skills, education classes, diet or exercise, iii) the outcome measures that determine the success of the intervention must either consider HbA1c, fasting blood glucose (FBG), body mass index (BMI) or weight lost (measured in pounds or kilograms). Interventions that did not exclusively recruit individuals with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder were considered. Studies were excluded if they were in a language other than English, French, Italian or Greek; focused on metabolic syndrome, genetics or screening; or considered risk factors for developing type II diabetes without testing an intervention. Abstracts were also read if a title did not provide sufficient information for exclusion. After considering abstracts for eligibility, full text articles were rated for eligibility. In accordance with an inter-rater reliability of 0.40, disagreements between AC and ES were discussed with a third rater, CSD, and a collective consensus was reached. The eligible articles were subsequently rated for quality, and relevant references were considered.

Quality assessment

A 13-item quality assessment checklist was adapted from Lagerveld et al. [ 20 , 21 ]. Items assessed study design, intervention measurements, outcome measurements, and the presentation of data and analysis. Additional file 1 contains a complete list of items. Each study that met the inclusion/exclusion criteria was independently screened by AC and ES for quality assessment criteria adapted and developed a priori. The inter-rater reliability was 0.62. All disagreements in scoring were discussed and quality rating was reached through consensus between the two independent raters.

Articles that met all quality items were considered excellent. Papers were rated fair and excluded if they had any of the following exclusion criteria: i) does not state the main features of the population which was defined as stating the recruitment location, geographic location, age, gender and eligibility criteria; ii) no account for lifestyle factors during data collection and analysis; iii) follow-up measurements do not include HbA1c, BMI, weight loss, and/or FBG. Therefore, a study was considered good if it did not meet the criteria to be considered fair, but lost other quality points, such as not discussing initial participation rates, and not using appropriate statistical methods or calculating statistical significance.

Determining relevant literature

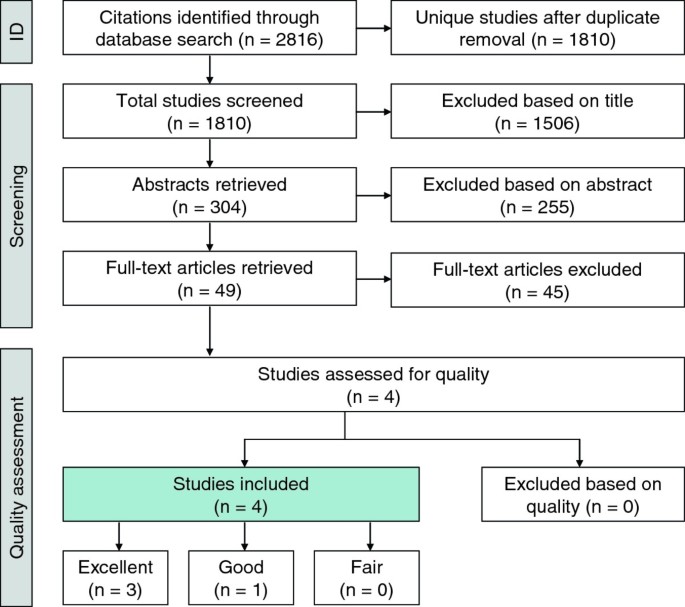

The systematic search of four databases (Medline, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and Web of Science) yielded a total of 1810 unique studies. Raters AC and ES independently screened titles and eliminated those that met the exclusion criteria. A total of 304 abstracts were reviewed in accordance with the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Of these, 49 full-text articles were retrieved. Four articles met the final inclusion criteria. This process of inclusions and exclusions is depicted in Figure 1 .

Flowchart of literature search results and inclusions/exclusions .

The following is a list of reasons for excluding the 45 full text articles: i) A total of 2.2% (n = 1) was a textbook chapter that elaborated on a study already included; ii) Another 2.2% (n = 1) proposed an intervention that would hypothetically be effective without testing its effectiveness; iii) 4.4% of articles (n = 2) were interventions where outcome measurements did not include blood glucose or weight assessment; iv) A total of 15.6% (n = 7) did not include both type II diabetes and schizophrenia in the study population; v) Another 22.2% of the articles (n = 10) focused on increasing glycaemic control through changing medication, without addressing lifestyle factors; vi) The remaining 53.3% of papers (n = 24) did not assess the effectiveness of an intervention.

Methodological quality

The four articles that met all inclusion criteria were assessed using the methodological quality assessment checklist that categorized articles as being excellent, good or fair. Of these, three were assessed to be excellent, and the remaining study was rated good. Thus, no articles were excluded at this step, because all met quality criteria good or better.

Characteristics of included studies

The significant characteristics of each paper are presented in Table 2 . Major findings of each intervention analyzed are presented in Table 3 . The included articles also shared common elements: each study recruited participants from different US states; they all considered the older-adult population, as indicated by the mean participant age ranging between 44-53 years; interventions each included exercise promotion and nutrition education; they also incorporated components that addressed the challenges associated with this particular population, such as decreased cognitive ability and reduced motivation [ 22 , 23 ]. For example, inpatient modules in Lindenmayer's et al. [ 24 ] study were taught for four months before initiating a new level. Some of McKibbin et al.'s [ 23 ] strategies involved gradually introducing new topics, utilizing memory aids, and providing minimal text so as to simplify messages. One important difference to note is the variation in study locations: two programs recruited from a psychiatric hospital inpatient setting [ 24 , 25 ]. The remaining two articles addressed health needs of individuals in out-patient mental health settings, such as board-and-care accommodations and community clubhouses [ 23 , 26 ].

Results of in-patient interventions

Both in-patient programs provided information regarding the importance of exercise, and provided strategies for making this lifestyle change [ 24 , 25 ]. After enhancing patient motivation through classes, achieving physical activity recommendations in both studies were promoted by providing exercise facilities. Lindenmayer et al.'s [ 24 ] knowledge assessment of the four month fitness and exercise module demonstrated an improvement in scores, as they increased from 56.6% to 67.6% ( P < 0.001). Participants in Teachout et al.'s [ 25 ] intervention were given additional resources: pedometers, encouragement to walk, and yoga classes. Fitness knowledge was not assessed following the intervention.

In both studies, nutrition lessons were aimed at improving dietary habits. In Lindenmayer et al.'s [ 24 ] program, workshops provided dietary tips and a weekly 25 dollars was given to enable the purchase of healthy foods. This strategy was successful as the knowledge assessment scale for the four month section on nutrition and healthy lifestyle increased from 57% to 69.4% ( P < 0.001). Teachout et al.'s [ 25 ] method involved modules on healthy meal planning, shopping and food preparation over a period of six months. However, participant knowledge gained from this approach was not measured.

Overall, the psychiatric in-patient interventions had a positive impact on weight, BMI and blood glucose measurements, thus indicating the effectiveness of combining diet and exercise. After 12 months, participants with type II diabetes and severe mental illness in Lindenmayer et al.'s [ 24 ] trial lost a mean total of 5.98 lb. BMI was also reduced from 33.94 kg/m2 to 30.55 kg/m2 (statistical significance was not calculated for BMI or weight loss). Furthermore, blood glucose also decreased significantly, from an average of 115.85 mg/DL to 98.05 mg/DL ( P < 0.001). This reduction was significantly related to the nutrition module that was completed during the beginning of the intervention. Similarly, all of Teachout et al.'s [ 25 ] participants reduced their weight, with an average loss of 20.35 lb, and 40% of fasting glucose levels met the recommended value as outlined by the ADA (statistical significance was not calculated).

Results of out-patient interventions

In McKibbin et al.'s [ 23 ] six month Diabetes Awareness and Rehabilitation Training (DART), participants received 90-min weekly sessions providing diet, exercise and other diabetes self-care strategies such as monitoring blood glucose levels. Physical activity modules involved learning about the different types of exercise, how being active can impact blood glucose, and how to keep track of daily exercise. Participants were also given pedometers, encouraged to walk, and tracked weekly weight changes to increase motivation.

Participants additionally received simplified nutrition education that provided knowledge of the different food groups, adequate portion sizes, healthy meal planning and label reading, as well as substituting sugar consumption with fat and fibre.

Comparing the outcome measurements of the DART program with a Usual Care (UC) group that received pamphlets from the ADA and continued seeing their family physician indicated the effectiveness of the DART intervention. While the control group gained a total of 6.8 lbs during the study period, intervention participants lost an average of 5.1 lbs ( P < 0.001). Correspondingly, DART participants' BMI was reduced on average from 33.6 kg/m2 to 32.9 kg/m2, whereas the UC increased from 32.9 kg/m2 to 33.9 kg/m2 ( P < 0.001). Study participants also enhanced their diabetes knowledge from 0.5 to 0.7, while there was no change in the scores for the control group ( P < 0.001). Although there was a reduction in fasting blood glucose and HbA1c in both the experimental and control group, findings were not statistically significant.

The effectiveness of this intervention was measured six months after the end of the study [ 26 ]. The DART group maintained their average BMI of 32.9 kg/m2, while the control group continued to gain weight, totaling an average of 34 kg/m2. Although diabetes knowledge dropped at 12 months from 0.7 to 0.6, it was still higher than the baseline value of 0.5. Therefore, the follow-up study revealed that sustainable skills were gained from the DART intervention.

The current literature assessing the management of type II diabetes for individuals with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders has indicated that there are a number of tactics used to manage blood glucose levels. One that has drawn attention involves changing the antipsychotics prescribed. Antipsychotics have been the focus because of the weight gain and glucose intolerance that is associated with use of these medications [ 4 , 5 , 11 ]. A meta-analysis conducted by Barnett et al. [ 10 ] reported that patients treated with clozapine and olanzapine have higher rates of weight gain and therefore increased diagnosis of type II diabetes compared to other antipsychotics. Consistent with these findings are case studies that changed antipsychotic medications as an intervention to manage blood glucose in type II diabetes. Lerner et al. [ 27 ] lowered the dose of olanzapine for two patients and noted a reduction in blood glucose levels. Furthermore, a total of four case studies observed a remission of type II diabetes upon the replacement of olanzapine with risperidone, as HbA1c levels normalized [ 28 – 31 ]. Given the impact of antipsychotic medications in the development of this disease, recommendations are often made to change prescriptions if persistent weight gain and onset of type II diabetes occurs [ 10 , 12 , 32 ]. However, this treatment approach poses challenges because individuals with schizophrenia may experience a relapse of psychotic or depressive symptoms during the transition period between medications [ 33 , 34 ]. Moreover, not every individual has a therapeutic response to all antipsychotics [ 35 ].

Considering the challenges with changing antipsychotic medication, our SER aimed at determining effective delivery of diet and lifestyle interventions to enable management of type II diabetes in individuals with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorders. The success of diet and lifestyle interventions to prevent or manage type II diabetes in individuals with and without schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorders has been documented in the literature. Menza et al. [ 36 ] conducted a 12-month lifestyle intervention that combined diet and physical activity in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders. Findings included reduced weight and BMI, increased nutritional knowledge, and improved HbA1c levels, thus minimizing risk of type II diabetes development. Torgerson et al. [ 37 ] was successful in preventing the onset of type II diabetes in obese individuals by combining weight loss with the inhibition of an enzyme that breaks down fats. Additionally, Lim et al.'s [ 38 ] paper suggests that weight loss enabled by restricting calories to 600 kcal/day is an effective method to decrease BMI within the general type II diabetes population ( P < 0.05). Calorie restriction also corresponded to greater blood glucose control, as glycated hemoglobin decreased to normal levels in 8 weeks ( P < 0.05).

While the relationship between lifestyle interventions with weight loss and improved glycated hemoglobin is well documented, the most effective way of delivering DSME is not always clear for individuals with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorders. Therefore, our paper makes an important contribution to the literature by highlighting effective DSME strategies to support the integration of healthy habits into lifestyle. Each DSME lifestyle intervention reviewed in our paper observed reduced weight and BMI in the presence of intervention strategies that addressed the challenges associated with schizophrenia, such as decreased cognitive ability, reduced motivation and limited access to resources [ 6 , 22 , 23 ]. Additionally, Lindenmayer et al. [ 24 ] and Teachout et al. [ 25 ] observed that diet can reduce fasting blood glucose.

One drawback consistent in all interventions was the absence of finding statistical significance when HbA1c levels were reduced. One likely explanation is the fact that interventions were not long enough to observe changes in HbA1c levels [ 23 , 39 ]. This is because retrieving an accurate measure may require blood glucose to be controlled for more than three months. If lifestyle changes were not fully adopted, it would be more difficult to see a reduction in HbA1c, even if some changes occurred. In contrast, blood glucose measures depict blood glucose at one point in time and this value can fluctuate hourly. Thus, HbA1c is considered a more reliable measure of overall blood glucose control. Additionally, HbA1c has been correlated with diabetes complications, while blood glucose has not [ 39 ].

Because all quality ratings of the analyzed studies resulted in excellent and good assessments, there is a strong level of evidence to support our conclusion made in this SER [ 40 ]. However, while the findings of this paper indicate that lifestyle interventions positively impact type II diabetes management, there were limitations associated with the heterogeneity of the study settings included in the analysis. In the psychiatric inpatient setting, participation in the interventions was structured in the individual's daily routine. Conversely, in McKibbin et al.'s [ 23 ] study, recruitment from community clubhouses and board-and-care facilities indicates that participant involvement required a greater level of self-motivation. Therefore, care needs to be taken if inpatient interventions are adapted in outpatient settings, because individuals within the community may have limited access to fitness resources, such as gym equipment and safe areas to exercise.

As a result of limiting searches to four databases containing primarily peer-reviewed material, a potential publication bias is an additional limitation of this SER. However, the databases searched covered an extensive scope of clinical disciplines that were relevant for the nature of the research question: PsycINFO captures psychological literature, CINAHL retrieves the nursing and allied health, Medline contains medical literature, while ISI Web of Science is multidisciplinary. Additionally, while grey literature was not searched for directly, PsycINFO includes doctoral theses available in Dissertations Abstracts International. Additionally, due to a lack of fluency in languages other than English, French, Italian and Greek, papers in other languages were not considered.

While the analyzed studies indicate the short-term effectiveness of lifestyle interventions in individuals with type II diabetes and schizophrenia, the long-term sustainability of treatment outcomes has not been explored. Additionally, it has been observed that such lifestyle interventions are effective for older adults with type II diabetes and schizophrenia. However, the success of such approaches within the first episode population is unknown. Although adults over 40 years of age are an important population to consider due to the increased risk factors of diabetes from long-term use of antipsychotics and being over the age of 45, the onset of type II diabetes in individuals aged 20 to 49 years is increasing [ 12 , 41 , 42 ]. Therefore, an additional recommendation for future research involves determining the effectiveness of such programs for youth and young adults experiencing early-onset psychosis who also have type II diabetes.

Overall, the current state of the literature suggests promise within this line of inquiry. However, our review also indicates that there are gaps in the current literature. Of additional significance is the need for interdisciplinary teams when addressing the complex health concerns associated with both schizophrenia and type II diabetes [ 12 ].

Findings of this SER suggest that lifestyle interventions can be effective in managing type II diabetes in patients that concurrently have schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorders. However, they should be sensitive to the unique challenges associated with type II diabetes and schizophrenia. These challenges include decreased cognition and motivation, limited resources, as well as negative side effects (i.e. loss of energy and weight gain) that may result from antipsychotics. Successful strategies involved positive encouragement to make changes, gradual introduction of new concepts and skills relating to diet and exercise, conveying simple messages for complex topics such as food skills relating to cooking and planning meals, and incorporating memory aids [ 23 , 24 ].

The findings of this review indicate a strong level of evidence; there are effective interventions for people with schizophrenia and type II diabetes. However, there is a need for continued research to fill gaps. These include exploration of the long-term sustainability of DSME lifestyle interventions, and addressing the young adult population suffering from schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorders with type II diabetes. Furthermore, the need for interdisciplinary interventions should be kept in mind, as the collective expertise of psychiatrists, psychiatric nurses, family physicians and diabetes educators such as dietitians are all needed. Taking these factors into account will enable policies and interventions to be developed that improve the healthcare and quality of life of individuals with type II diabetes and schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorders.

World Health Organization: Diabetes Fact sheet N°312. [ http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs312/en/ ]

World Health Organization: 2008-2013 Action Plan for the Global Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases. [ http://www.who.int/nmh/Actionplan-PC-NCD-2008.pdf ]

Nelms M, Sucher KP, Lacey K, Long Roth S: Nutrition Therapy and Pathophysiology. 2010, Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning, 2

Google Scholar

American Diabetes Association, American Psychiatric Association, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, North American Association for the Study of Obesity: Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004, 27: 596-601.

Article Google Scholar

Heald A: Physical health in schizophrenia: a challenge for antipsychotic therapy. Eur Psychiatry. 2010, 25: S6-S11.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

El-Mallakh P: Doing my best: Poverty and self-care among individuals with schizophrenia and diabetes mellitus. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2007, 21: 49-60. 10.1016/j.apnu.2006.10.004.

Gough SCL, O'Donovan MC: Clustering of metabolic comorbidity in schizophrenia: a genetic contribution?. J Psychopharmacol. 2005, 19: 47-55. 10.1177/0269881105058380.

Krosnick A, Wilson MG: A retrospective chart review of the clinical effects of atypical antipsychotic drugs on glycemic control in institutionalized patients with schizophrenia and comorbid diabetes mellitus. Clin Ther. 2005, 27: 320-326. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.02.017.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Melkersson K, Dahl ML: Adverse metabolic effects associated with atypical antipsychotics - Literature review and clinical implications. Drugs. 2004, 64: 701-723. 10.2165/00003495-200464070-00003.

Barnett AH, Mackin P, Chaudhry I, Farooqi A, Gadsby R, Heald A, Hill J, Millar H, Peveler R, Rees A, et al: Minimising metabolic and cardiovascular risk in schizophrenia: diabetes, obesity and dyslipidaemia. J Psychopharmacol. 2007, 21: 357-373.

Cohn TA, Sernyak MJ: Metabolic monitoring for patients treated with antipsychotic medications. Can J Psychiatry-Revue Canadienne De Psychiatrie. 2006, 51: 492-501.

Woo V, Harris SB, Houlden RL: Canadian Diabetes Association Position Paper: Antipsychotic Medications and Associated Risks of Weight Gain and Diabetes. Can J Diabetes. 2005, 29: 111-112.

Canadian Diabetes Association: Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of diabetes in Canada. Canadian Journal of Diabetes. 2008, 32 (Supplement 1): S1-S201.

American Diabetes Association: Standards of medical care in diabetes - 2012. Diabetes Care. 2012, 35 (Sup): S11-S63.

Goldberg RW, Kreyenbuhl JA, Medoff DR, Dickerson FB, Wohlheiter K, Fang J, Brown CH, Dixon LB: Quality of diabetes care among adults with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2007, 58: 536-543. 10.1176/appi.ps.58.4.536.

Frayne SM, Halanych JH, Miller DR, Wang F, Lin H, Pogach L, Sharkansky EJ, Keane TM, Skinner KM, Rosen CS, Berlowitz DR: Disparities in Diabetes Care. Arch Intern Med. 2005, 165: 2631-2638. 10.1001/archinte.165.22.2631.

Dickerson FB, Goldberg RW, Brown CH, Kreyenbuhl JA, Wohlheiter K, Fang L, Medoff D, Dixon LB: Diabetes knowledge among persons with serious mental illness and type 2 diabetes. Psychosomatics. 2005, 46: 418-424. 10.1176/appi.psy.46.5.418.

Becker T, Hux J: Risk of acute complications of diabetes among people with schizophrenia in Ontario, Canada. Diabetes Care. 2011, 34: 398-402. 10.2337/dc10-1139.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Newman SC, Bland RC: Mortality in a cohort of patients with schizophrenia: a record linkage study. Can j psychiatry Revue canadienne de psychiatrie. 1991, 36: 239-245.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Lagerveld SE, Bultmann U, Franche RL, van Dijk FJ, Vlasveld MC, van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, Bruinvels DJ, Huijs JJ, Blonk RW, van der Klink JJ, Nieuwenhuijsen K: Factors associated with work participation and work functioning in depressed workers: a systematic review. J Occup Rehabil. 2010, 20: 275-292. 10.1007/s10926-009-9224-x.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Mallen C, Peat G, Croft P: Quality assessment of observational studies is not commonplace in systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006, 59: 765-769. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.12.010.

Dickinson D, Gold JM, Dickerson FB, Medoff D, Dixon LB: Evidence of exacerbated cognitive deficits in schizophrenia patients with comorbid diabetes. Psychosomatics. 2008, 49: 123-131. 10.1176/appi.psy.49.2.123.

McKibbin CL, Patterson TL, Norman G, Patrick K, Jin H, Roesch S, Mudaliar S, Barrio C, O'Hanlon K, Griver K, et al: A lifestyle intervention for older schizophrenia patients with diabetes mellitus: A randomized controlled trial. Schizophr Res. 2006, 86: 36-44. 10.1016/j.schres.2006.05.010.

Lindenmayer JP, Khan A, Wance D, Maccabee N, Kaushik S: Outcome Evaluation of a Structured Educational Wellness Program in Patients With Severe Mental Illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009, 70: 1385-1396. 10.4088/JCP.08m04740yel.

Teachout A, Kaiser SM, Wilkniss SM, Moore H: Paxton House: Integrating Mental Health and Diabetes Care for People with Serious Mental Illnesses in a Residential Setting. Psychiatric Rehabil J. 2011, 34: 324-327. 10.2975/34.4.2011.324.327.

McKibbin CL, Golshan S, Griver K, Kitchen K, Wykes TL: A healthy lifestyle intervention for middle-aged and older schizophrenia patients with diabetes mellitus: A 6-month follow-up analysis. Schizophr Res. 2010, 121: 203-206. 10.1016/j.schres.2009.09.039.

Lerner V, Libov I, Kanevsky M: High-dose olanzapine-induced improvement of preexisting type 2 diabetes mellitus in schizophrenic patients. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2003, 33: 403-410. 10.2190/8J17-J4PB-F2KX-05YY.

Wu P-L, Lane H-Y, Su K-P: Risperidone alternative for a schizophrenic patient with olanzapine-exacerbated diabetic mellitus. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006, 60: 115-116. 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2006.01469.x.

Melkersson K, Hulting A-L: Recovery from new-onset diabetes in a schizophrenic man after withdrawal of olanzapine. Psychosomatics: J Consult Liaison Psychiatry. 2002, 43: 67-70. 10.1176/appi.psy.43.1.67.

Waldman JC, Yaren S: Atypical antipsychotics and glycemia: a case report. The Can J Psychiatry/La Revue canadienne de psychiatrie. 2002, 47: 686-687.

Ashim S, Warrington S, Anderson IM: Management of diabetes mellitus occurring during treatment with olanzapine: report of six cases and clinical implications. J Psychopharmacol. 2004, 18: 128-132. 10.1177/0269881104040253.

Gothefors D, Adolfsson R, Attvall S, Erlinge D, Jarbin H, Lindstrom K, von Hausswolff-Juhlin YL, Morgell R, Toft E, Osby U: Swedish clinical guidelines-Prevention and management of metabolic risk in patients with severe psychiatric disorders. Nordic J Psychiatry. 2010, 64: 294-302. 10.3109/08039488.2010.500397.

Ganguli R, Brar JS, Mahmoud R, Berry SA, Pandina GJ: Assessment of strategies for switching patients from olanzapine to risperidone: a randomized, open-label, rater-blinded study. Bmc Med. 2008, 6: 17-10.1186/1741-7015-6-17.

Weiden PJ: Switching in the era of atypical antipsychotics. An updated review. Postgrad Med. 2006, Spec No: 27-44.

PubMed Google Scholar

Kane JM, Marder SR: Psychopharmacologic treatment of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1993, 19: 287-302.

Menza M, Vreeland B, Minsky S, Gara M, Radler DR, Sakowitz M: Managing Atypical antipsychotic-associated weight gain: 12-month data on a multimodal weight control program. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004, 65: 471-477.

Torgerson JS, Hauptman J, Boldrin MN, Sjostrom L: XENical in the prevention of diabetes in obese subjects (XENDOS) study: a randomized study of orlistat as an adjunct to lifestyle changes for the prevention of type 2 diabetes in obese patients. Diabetes Care. 2004, 27: 155-161. 10.2337/diacare.27.1.155.

Lim EL, Hollingsworth KG, Aribisala BS, Chen MJ, Mathers JC, Taylor R: Reversal of type 2 diabetes: normalisation of beta cell function in association with decreased pancreas and liver triacylglycerol. Diabetologia. 2011,

Landgraf R: HbA1c-the gold standard in the assessment of diabetes treatment?. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2006, 131 (Suppl 8): S243-246.

Ariens GA, van Mechelen W, Bongers PM, Bouter LM, van der Wal G: Physical risk factors for neck pain. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2000, 26: 7-19. 10.5271/sjweh.504.

American Diabetes Association: Diabetes Statistics. [ http://www.diabetes.org/diabetes-%20basics/diabetes-statistics/ ]

Lipscombe LL, Hux JE: Trends in diabetes prevalence, incidence, and mortality in Ontario, Canada 1995-2005: a population-based study. Lancet. 2007, 369: 750-756. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60361-4.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-244X/12/24/prepub

Download references

Acknowledgements

Dr. Dewa and the practicum students, AC and ES, gratefully acknowledge the support of Dr. Dewa's CIHR/PHAC Applied Public Health Chair. The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health receives funding from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care to support research infrastructure.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre for Research on Employment and Workplace Health, Centre for Addition and Mental Health, 455 Spadina, Suite 300, Toronto, Ontario, M5S 2G8, Canada

Adriana Cimo, Erene Stergiopoulos, Chiachen Cheng & Carolyn S Dewa

Canadian Mental Health Association, Clinic & Resource Centre, 272 Park Avenue, Thunder Bay, P7B 1C5, Canada

Chiachen Cheng

Library Services, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, 33 Russell Street, Toronto, M5S 2S1, Canada

Sarah Bonato

Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, 250 College Street, Toronto, M5T 1R8, Canada

Carolyn S Dewa

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Carolyn S Dewa .

Additional information

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

AC led the conception, design, data acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data. ES collaborated on the design, data acquisition and analysis. CC collaborated on the design and acquisition of data. SB collaborated on the design and data acquisition. CSD collaborated on the conception, design and acquisition of data, and supervised the data analysis and interpretation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12888_2011_966_moesm1_esm.doc.

Additional file 1: Quality assessment checklist; The additional file contains the quality checklist criterion that was used to determine the quality of the papers being analyzed for the systematic review . Scores of each article are displayed as well as the quality checklist items that were adapted from Lagerveld et al. [ 20 ]. (DOC 35 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Authors’ original file for figure 1

Rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Cimo, A., Stergiopoulos, E., Cheng, C. et al. Effective lifestyle interventions to improve type II diabetes self-management for those with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 12 , 24 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-12-24

Download citation

Received : 12 August 2011

Accepted : 23 March 2012

Published : 23 March 2012

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-12-24

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Schizophrenia

- Lifestyle Intervention

- Severe Mental Illness

BMC Psychiatry

ISSN: 1471-244X

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

The Strong Link Between Schizophrenia and Diabetes

That there is a strong link between schizophrenia and diabetes is not a new discovery. The relationship between diabetes and schizophrenia has been known for more than 100 years. While after a century much about the connection is still not well understood, medical and mental health professionals are building knowledge about the connection and using it to develop better prevention and treatment for people who live with both schizophrenia and diabetes.

The number of people with both illnesses is significant. People with schizophrenia are three times more likely than the general population to develop type 2 diabetes (Toich, 2017). Further, 20-30 percent of people with schizophrenia will develop diabetes type 2 (Cohn, 2012). These numbers are too high to dismiss as coincidence. What is it that influences the connection between these drastically different medical and psychiatric conditions? Here’s a look at what researchers are discovering.

Schizophrenia, Antipsychotic Medication, and Diabetes

One culprit for the development of diabetes in people with schizophrenia is antipsychotic medication . Antipsychotics are an essential component of schizophrenia treatment. They’re necessary to reduce the hallucinations, delusions, and many other symptoms of schizophrenia. Antipsychotics, however, have dangerous side effects, including weight gain (" Are There Any Safe Antipsychotics in Diabetes Treatment? ").

Weight gain from antipsychotic medications is often significant. Antipsychotic medications can cause obesity, high cholesterol, and an increase in triglycerides, or fats found in the blood. These conditions can cause type 2 diabetes.

Many different types of antipsychotics and atypical antipsychotics are available. Ideally, people with schizophrenia take medications that cause the least amount of weight gain, such as aripiprazole (Abilify) or ziprasidone (Geodon); however, this isn’t always the case. Multiple classic and atypical antipsychotics are available and widely used to treat schizophrenia. Chlorpromazine (Thorazine), clozapine (Clozaril), and olanzapine (Zyprexa) are among those that cause the biggest amount of weight gain.

Attributing diabetes to weight gain from medication has proven to be too simplistic. Sometimes, diabetes develops very rapidly after someone is newly diagnosed with schizophrenia. Researchers have found that some people who experience their first episode of psychosis already have indications of type 2 diabetes:

- Decreased glucose tolerance

- High fasting plasma glucose levels

- High fasting plasma insulin levels

- Increased insulin resistance

This happens either before or shortly after medication treatment begins, before weight gain and other side-effects have begun; therefore, the link between schizophrenia and diabetes isn’t merely from medication. There is something about schizophrenia itself that contributes to the development of diabetes.

Factors Contributing to the Schizophrenia and Diabetes Link

Without a doubt, medication-induced weight gain is part of the reason these two serious conditions co-occur. It’s just not the only factor. Knowing what else contributes to the development of diabetes in people with schizophrenia can lead to better treatment and management strategies.

These factors solidify the link between diabetes and schizophrenia:

- Genetics . There is a genetic component not yet fully understood that makes some people more prone than others to develop these illnesses.

- Developmental risk factors . Premature birth, low birth weight, and other pregnancy and delivery complications can contribute to both schizophrenia and diabetes.

- Lifestyle . Often, schizophrenia is associated with cigarette smoking, poor diet, and lack of exercise, all things that are detrimental to health.

- Social health problems . Low income, poor housing circumstances, and difficulty meeting basic needs are risk factors for serious health problems like the combination of diabetes and schizophrenia.

Living with both schizophrenia and diabetes presents numerous challenges (" Schizophrenia Makes Diabetes Management Challenging "). Understanding the unbreakable link can help lead to a treatment approach that incorporates the management of both illnesses together. This can improve the quality of life for people with combined type 2 diabetes and schizophrenia.

article references

APA Reference Peterson, T. (2022, January 4). The Strong Link Between Schizophrenia and Diabetes, HealthyPlace. Retrieved on 2024, May 30 from https://www.healthyplace.com/diabetes/mental-health/the-strong-link-between-schizophrenia-and-diabetes

Medically reviewed by Harry Croft, MD

Related Articles

Complete List of Diabetes Medications for Type 1 and Type 2

Starlix for treatment of diabetes - starlix full prescribing information, four ways to prevent diabetes when you live with a mental illness, glucagen for diabetics - glucagen full prescribing information, diabetes and the mental health connection sitemap, precose for treatment of diabetes - precose full prescribing information, challenges of treating diabetes when you have adhd.

2024 HealthyPlace Inc. All Rights Reserved. Site last updated May 30, 2024

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 24 February 2022

Systematic literature review of schizophrenia clinical practice guidelines on acute and maintenance management with antipsychotics

- Christoph U. Correll ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7254-5646 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Amber Martin 4 ,

- Charmi Patel 5 ,

- Carmela Benson 5 ,

- Rebecca Goulding 6 ,

- Jennifer Kern-Sliwa 5 ,

- Kruti Joshi 5 ,

- Emma Schiller 4 &

- Edward Kim ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8247-6675 7

Schizophrenia volume 8 , Article number: 5 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

15k Accesses

51 Citations

14 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Schizophrenia

Clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) translate evidence into recommendations to improve patient care and outcomes. To provide an overview of schizophrenia CPGs, we conducted a systematic literature review of English-language CPGs and synthesized current recommendations for the acute and maintenance management with antipsychotics. Searches for schizophrenia CPGs were conducted in MEDLINE/Embase from 1/1/2004–12/19/2019 and in guideline websites until 06/01/2020. Of 19 CPGs, 17 (89.5%) commented on first-episode schizophrenia (FES), with all recommending antipsychotic monotherapy, but without agreement on preferred antipsychotic. Of 18 CPGs commenting on maintenance therapy, 10 (55.6%) made no recommendations on the appropriate maximum duration of maintenance therapy, noting instead individualization of care. Eighteen (94.7%) CPGs commented on long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs), mainly in cases of nonadherence (77.8%), maintenance care (72.2%), or patient preference (66.7%), with 5 (27.8%) CPGs recommending LAIs for FES. For treatment-resistant schizophrenia, 15/15 CPGs recommended clozapine. Only 7/19 (38.8%) CPGs included a treatment algorithm.

Similar content being viewed by others

Adults who microdose psychedelics report health related motivations and lower levels of anxiety and depression compared to non-microdosers

Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations

Psilocybin microdosers demonstrate greater observed improvements in mood and mental health at one month relative to non-microdosing controls

Introduction.

Schizophrenia is an often debilitating, chronic, and relapsing mental disorder with complex symptomology that manifests as a combination of positive, negative, and/or cognitive features 1 , 2 , 3 . Standard management of schizophrenia includes the use of antipsychotic medications to help control acute psychotic episodes 4 and prevent relapses 5 , 6 , whereas maintenance therapy is used in the long term after patients have been stabilized 7 , 8 , 9 . Two main classes of drugs—first- and second-generation antipsychotics (FGA and SGA)—are used to treat schizophrenia 10 . SGAs are favored due to the lower rates of adverse effects, such as extrapyramidal effects, tardive dyskinesia, and relapse 11 . However, pharmacologic treatment for schizophrenia is complicated because nonadherence is prevalent, and is a major risk factor for relapse 9 and poor overall outcomes 12 . The use of long-acting injectable (LAI) versions of antipsychotics aims to limit nonadherence-related relapses and poor outcomes 13 .