Teaching Individuals with Autism Problem-Solving Skills for Resolving Social Conflicts

- Research Article

- Published: 30 August 2021

- Volume 15 , pages 768–781, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Victoria D. Suarez 1 ,

- Adel C. Najdowski ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2512-0397 2 ,

- Jonathan Tarbox 3 ,

- Emma Moon 2 , 4 ,

- Megan St. Clair 4 &

- Peter Farag 4

15k Accesses

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Resolving social conflicts is a complex skill that involves consideration of the group when selecting conflict solutions. Individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) often have difficulty resolving social conflicts, yet this skill is important for successful social interaction, maintenance of relationships, and functional integration into society. This study used a nonconcurrent multiple baseline across participants design to assess the efficacy of a problem-solving training and generalization of problem solving to naturally occurring untrained social conflicts. Three male participants with ASD were taught to use a worksheet as a problem-solving tool using multiple exemplar training, error correction, rules, and reinforcement. The results showed that using the worksheet was successful in bringing about a solution to social conflicts occurring in the natural environment. In addition, the results showed that participants resolved untrained social conflicts in the absence of the worksheet during natural environment probe sessions.

Similar content being viewed by others

An Exploration of the Performance and Generalization Outcomes of a Social Skills Intervention for Adults with Autism and Intellectual Disabilities

Social Skills Training for Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder

Building Social Skills: An Investigation of a LEGO-Centered Social Skills Intervention

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Problem solving is traditionally defined as the ability to identify the problem and then create solutions for the problem (Agran et al., 2002 ). From a behavioral perspective, a person is faced with a problem when they experience a state of deprivation or aversive stimulation (Skinner, 1953, p. 246), and reinforcement is contingent upon a response that is in the person’s repertoire, but cannot be evoked under current conditions (Palmer, 1991 , 2009 ). According to Skinner ( 1953 ), “problem-solving may be defined as any behavior which, through the manipulation of variables, makes the appearance of a solution more probable” (p. 247). Therefore, problem solving involves mediating or precurrent behaviors that function to manipulate or generate discriminative stimuli needed to evoke a resolution response (Palmer, 1991 ; Skinner, 1984 ). See Szabo ( 2020 ) for a conceptual analysis of problem solving.

Behavioral researchers have taught specific problem-solving strategies to individuals for learning specific skills (see Axe et al., 2019 for a review), such as categorizing items (Kisamore et al., 2011 ; Sautter et al., 2011 ), explaining how to complete tasks (Frampton & Shillingsburg, 2018 ), and completing vocational tasks (Lora et al., 2019 ). Such problem-solving strategies functioned to teach participants to engage in mediating or precurrent behaviors that brought about a resolution. For example, Sautter et al. ( 2011 ) taught participants to use rules as a precurrent behavior to evoke the resolution of sorting stimuli. Kisamore et al. ( 2011 ) taught participants a visual imagining strategy as a precurrent behavior to evoke the resolution of categorizing. Frampton and Shillingsburg ( 2018 ) taught participants to sort and sequence visual stimuli of each step of a multistep task as a precurrent behavior to evoke explaining how to complete the multistep task.

Another type of scenario that requires one to engage in problem solving is when dealing with social conflict. Resolving social conflicts likely involves similar precurrent behaviors addressed in previous behavioral literature, such as behavior chains, rules, self-questioning, sequencing, and potentially visual imagining (See Axe et al., 2019 , for a review). However, because social conflicts by definition involve interacting with other people, successfully resolving social conflicts also likely involves engaging in perspective taking, including tacting others’ perspectives, engaging in deictic relating behavior by switching perspectives (Luciano et al., 2020 ), and likely arranging for others involved in the conflict to also obtain reinforcement.

According to traditional psychology, problem solving begins to develop as early as the preschool years (e.g., Best et al., 2009 ; Garon et al., 2008 ). Yet, individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) often display deficits in social skills (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013 ) and have been found to demonstrate difficulties resolving social conflicts (Bernard-Optiz et al., 2001 ).

Given that a defining feature of ASD is to present with deficits in social communication and interaction (APA, 2013 ) and that resolving social conflicts across a wide range of situations is essential for functional integration into society and the maintenance of relationships (Bonete et al., 2015 ), it appears necessary to identify effective methods for teaching individuals with ASD to engage in problem-solving skills that will aid social conflict resolution. However, behavioral research has not evaluated methods to teach problem-solving skills in this context specifically to individuals diagnosed with ASD.

Although the population of ASD has not been studied in previous behavioral research on using problem-solving strategies to deal with social conflicts, a study conducted by Park and Gaylord-Ross ( 1989 ) used behavioral procedures to teach individuals with intellectual disabilities precurrent behaviors including rules, self-questioning, and self-prompting to solve problems they encountered at work, including social initiations, mumbling, and conversation expansions and terminations. During training, the researchers provided participants with a picture of themselves in a social situation (e.g., passing by a familiar customer at their workplace) and asked them how they would behave in the presented situation. Participants were provided with seven rules or questions to ask themselves: (1) What is happening? (2) What are three behaviors I could emit? (3) What will be the outcome of each behavior? (4) Which is better? (5) Pick one (6) Emit the behavior and (7) How did I feel? Prompting, modeling, and praise were used to teach participants to use the seven rules/questions. Pictures of novel social situations (other than the target situation) were presented at the end of training sessions to assess generalization to untrained stimuli and only one of three participants demonstrated stimulus generalization. During follow-up, an audiocassette recorder was placed in the participants' shirt pockets to record their interactions during their work and evaluate generalization of responding to trained stimuli in the natural environment. The results of the study indicated that participants’ target behaviors improved during training, and follow-up performance in the natural environment improved compared to baseline.

In addition to the paucity of research on this topic within behavior analysis, there is limited research outside of the behavioral literature that has evaluated methods for teaching individuals with ASD to use problem-solving strategies for dealing with social conflicts. One notable exception is a study conducted by Bernard-Optiz et al. ( 2001 ), who used a web-based problem-solving program to teach typically developing children and children with ASD to select and develop appropriate solutions. In particular, social conflicts were presented to participants on a computer screen with choices of possible solutions and an option to insert an individualized solution. For example, participants were shown a scenario in which two children wanted a turn to go down a slide. An audio cue asking, “What would you do?” was presented, and icons offering problem-solving solutions, such as requesting to go first, were provided. A second audio cue asking, “Do you have any good ideas?” was subsequently presented, and the option to insert a unique solution was presented. Novel solutions identified by participants resulted in social praise, and the option to continue inputting novel solutions continued to appear until participants no longer produced additional responses. All participants demonstrated an increase in the number of appropriate novel solutions generated. The results of Bernard-Optiz et al. ( 2001 ) demonstrated that social praise and a web-based problem-solving program functioned to increase generativity of problem solutions. Moreover, the results demonstrated that participants with ASD were taught to generate novel solutions to social conflicts using prompts and reinforcement. However, as the authors point out, a limited selection of social conflict scenarios were presented during intervention. Perhaps the most substantial limitation to the study is the use of an analogue computer task, without assessing whether problem-solving skills improved during real-life social interactions. In addition, maintenance was not measured.

Although behavioral research has found that teaching precurrent behaviors led participants to solve problems (e.g., Frampton & Shillingsburg, 2018 ; Kisamore et al., 2011 ; Lora et al., 2019 ; Park & Gaylord-Ross, 1989; Sautter et al., 2011 ), no research of which we are aware has evaluated the effects of teaching precurrent behaviors for resolving social conflicts to individuals with ASD. Further, although nonbehavioral research demonstrates prompts and social praise may function to increase resolving social conflicts in children with ASD (Bernard-Optiz et al., 2001 ), it is unknown if prompts and reinforcement would be successful in teaching individuals with ASD to use precurrent behaviors to resolve social conflicts. In addition, although research by Park and Gaylord-Ross (1989) measured generalization to trained problems in the natural environment, there is a dearth of research measuring generalization to untrained social conflicts occurring in the natural environment. Furthermore, research that has evaluated generalization to untrained problems found positive results with only one of three participants (Park & Gaylord-Ross, 1989).

The purpose of the current study was to investigate the effects of a problem-solving training package conducted in the natural environment on the use of problem-solving skills (i.e., precurrent behaviors) to resolve untrained social conflicts by individuals with ASD. The problem-solving training package consisted of a problem-solving worksheet, multiple exemplar training, error correction, rules, and reinforcement. Generalization of problem solving to untrained conflicts was programmed for by using multiple exemplar training and was assessed throughout the course of the study.

Participants and Setting

Three male individuals, with primary language being English, participated. Patrick was an 11-year-old Indigenous, Latinx, and white male with diagnoses of ASD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and bipolar disorder. Oliver was a 22-year-old Israeli male with a diagnosis of ASD. Russell was a 10-year-old Indigenous, Latinx, and white male with diagnoses of ASD and ADHD.

All participants received applied behavior analytic (ABA) services from a community-based agency for 10–12 hr per week. They demonstrated a listener behavior repertoire by engaging in auditory–visual conditional discriminations and following multistep instructions, used vocal–verbal communication in full sentences, and read and wrote basic paragraphs (i.e., three to five sentences). In addition, they demonstrated well-developed language skills by engaging in echoics, mands, tacts, and intraverbals. All participants labeled emotions in others (e.g., answered “How does she feel?”), identified cause-and-effect (e.g., answered “Why?” and “What will happen if . . . ?” For example, “Why did the egg break?” [“Because you dropped it.”], or “What will happen if I drop this egg?” [“It will break.”]), identified emotional cause-and-effect (e.g., answered “Why is she sad?” or “What will happen if someone takes her toy?”), and followed rules (e.g., “If you’re wearing pink, then raise your hand.”). In addition, participants used pronouns in speech and demonstrated listener behavior according to pronouns. All participants had a history of learning via role play and engaged in up to four intraverbal exchanges with others. At the time of recruitment, Patrick’s overall score on the Basic Living Skills Assessment Protocol from the Assessment of Functional Living Skills (AFLS) was 469 and Russell’s overall score was 475. No standardized assessment scores are available for Oliver, because his most recent assessment conducted prior to participation in this study was conducted using a commercially available web-based platform that does not provide raw scores. Participants were included because they did not independently and appropriately resolve social conflicts, and deficiency in resolving social conflicts was affecting their maintenance of positive relationships with siblings or parents. Individuals who demonstrated significant challenging behavior severe enough to interfere with instruction (e.g., self-injurious behavior [SIB], moderate to severe aggression) were ineligible to participate.

Participants were recruited because they were determined to benefit from learning to resolve social conflicts by their supervising clinician. Moreover, participants were recruited by asking them (for Oliver) or their parents (for Patrick and Russell) if they would like to participate in a research study evaluating a lesson for teaching problem-solving skills to resolve social conflicts. Consent was obtained by providing a consent form outlining the study’s purpose, methods, and potential benefits/risks to Oliver and the parents of Patrick and Russell. In addition, assent forms were provided to Patrick and Russell.

Research sessions were conducted during regularly scheduled ABA-based teaching sessions in home-based and clinic-based settings for the duration of the study with the exception of Oliver who made a transition from home- and clinic-based sessions to solely telehealth sessions (due to the COVID-19 pandemic) beginning with session 21. Research sessions were conducted in various rooms throughout the session environment (e.g., bedroom, living room, lobby, conference room). Research sessions were 5–30 min in length and consisted of the presentation of one problem. One to two research sessions (conducted at least 30 min apart) were conducted 1–3 days per week.

Response Measurement and Data Collection

A problem-solving task analysis (TA; Table 1 ) was used to calculate the percentage of correct, independent problem-solving steps completed by each participant. Each step of the TA was scored as correct or incorrect based on the specified criteria (Table 1 ). A correct response included independently and accurately completing a step within the task analysis by either writing a response or vocally stating a response within 10 s of: (1) the problem occurring (step 1) and (2) the previous step being completed (steps 2–13). An incorrect response included responses irrelevant to the current step, prompted responses, and nonresponses (i.e., failure to respond within 10 s of the problem [step 1] or previous step occurring [steps 2–14]). During baseline and posttraining, if the participant was not progressing through the conflict (e.g., not doing anything to resolve the conflict) after 1 min of the problem occurring, the conflict was ended by the interventionist resolving the conflict (e.g., if the conflict was that brother left Legos on the table where the participant was going to eat, the interventionist resolved the conflict by removing the Legos) and all remaining steps of the TA were scored as incorrect.

Natural environment probes (explained below) were scored as all or nothing. If the participant successfully resolved the social conflict by engaging in a viable solution (i.e., any solution that would function to resolve the conflict and could be readily carried out) within 10 s of the conflict occurring, the natural environment probe was scored as 100% correct. On the other hand, if the participant failed to resolve the social conflict (i.e., proposed and/or engaged in an impracticable solution or was nonresponsive as defined earlier), the natural environment probe was scored as 0% correct.

Interobserver agreement (IOA) was collected by two independent observers who recorded data during 33% of baseline sessions for all participants. IOA data were collected during 50%, 62%, and 57% of training sessions for Patrick, Oliver, and Russell, respectively. Moreover, IOA data were collected during 67% of posttraining sessions for Patrick and Oliver and 50% for Russell. IOA data were collected during 75% of follow-up sessions for Patrick and 100% for Oliver and Russell. Finally, IOA data were collected during 50%, 40%, and 50% of natural environment probes for Patrick, Oliver, and Russell, respectively. Point-by-point agreement was used to identify observers’ agreement on whether each step was performed correctly versus incorrectly by dividing the number of steps for which there was agreement by the total number of steps and multiplying the resulting quotient by 100%.. Mean IOA was 100%, 98.8% (range; 90%–100%), and 98.7% (range: 90%–100%) for Patrick, Oliver, and Russell, respectively.

Experimental Design and Procedure

A nonconcurrent multiple baseline across participants design was used to assess the effects of the problem-solving training package.

General Procedures

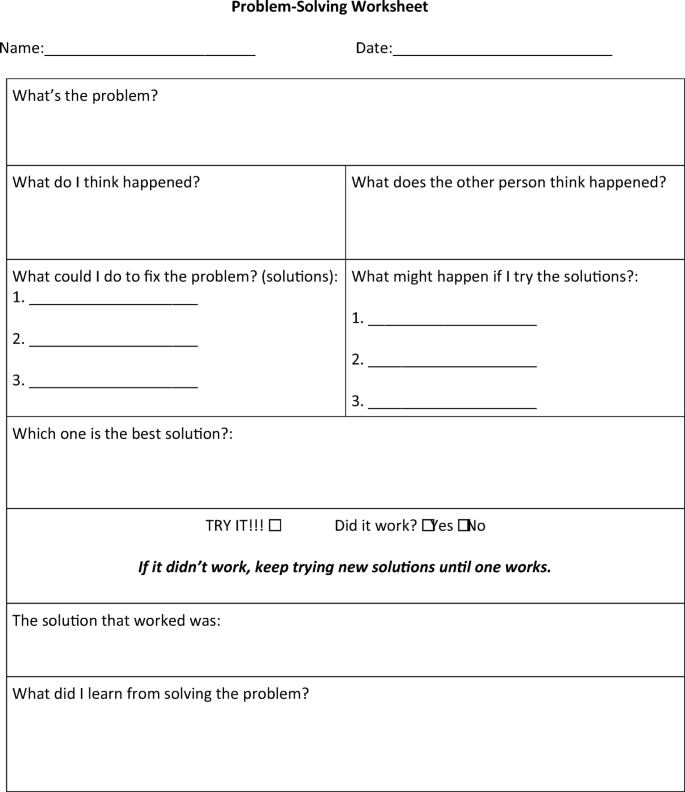

At the beginning of each ABA-based teaching session, participants were provided with a variation of the following instruction: “Today during your session, a social problem with someone will happen at some point. Here is a worksheet [see Fig. 1 ] you can use to help solve the problem when it happens.” The worksheet was written using language that was previously observed to be used by the participants and that they were familiar with.

Problem-solving worksheet

Then, ABA-based teaching activities began, and at some point between teaching activities, up to 15 min after delivering the instruction, a social conflict was contrived or captured with people in the natural environment. For example, when the participant and his brother both wanted to go first at a game, data were collected on how the participant responded to the problem-solving steps outlined on the TA. If the participant engaged in any negative emotional responding, such as whining or crying during the presentation of the social conflict, a second conflict was not presented again that day.

Social conflicts to be used were determined by interviewing the participants and their parents and asking them what situations usually led to arguments with others. In addition, we observed naturally occurring social interactions between the participants and others and identified situations in which a social conflict arose and the participant failed to resolve the conflict. We then set up these scenarios to occur during the research session. For example, Russell stated he argued with his brother when his brother wanted to play a video game that he was already playing. So, we arranged for Russell’s brother to request playing a video game that Russell was actively playing during the research session. Other times, the scenarios were genuinely captured, so we ran the research session upon capturing the naturally occurring conflict. For example, we observed that Patrick walked into his room to find that his brother had left dirty dishes on his desk and was notably upset as evidenced by his tone of voice, prosody, heavy breathing, and crying. The social conflicts contrived or captured are provided in Table 2 .

During baseline, in addition to the general procedures, problems occurred with at least two different people (e.g., parent, sibling; see Table 3 ). We did not provide any prompting or feedback in order to assess the extent to which participants resolved social conflicts independently. If the participant was not progressing through the conflict after 1 min of the conflict occurring, the conflict was ended by the interventionist resolving the problem. It was planned that if any distressed behavior (e.g., crying, screaming, negative statements, SIB, aggression) was observed for a duration of at least 10 s, the conflict was to be ended by the interventionist resolving the problem; however, distressed behavior never occurred during baseline. Participants qualified to continue to the training phase if they scored 60% or less on the problem-solving TA. Two participants were excluded for not meeting this criterion.

Pretraining Phase

In this phase, the participant was taught how to use the problem-solving worksheet. In particular, the purpose of this phase was to evaluate whether simply providing the worksheet would result in improved problem-solving performance, that is, to ensure that the repertoires were not already present but just not under the stimulus control of the worksheet. The interventionist began by providing the participant with the following instruction: “This is a worksheet you can use to help you solve problems you have with other people. To use it, you will read each of the questions on it and answer them while the problem is happening to help you solve it.” Then, the interventionist walked the participant through each question on the worksheet by pointing to each step and instructing the participant on what they should do for each worksheet question. For example, the interventionist pointed to the first question on the worksheet and said, “In this box you will ask yourself, ‘What is the problem?’ and you will write down or say out loud the problem that is happening between you and another person. After this, the interventionist pointed to the second question on the worksheet and said, “In this box you will ask yourself, ‘What do I think happened?’ and you will write down what happened from your perspective.” After going through each question on the worksheet with the participant in a similar fashion, the interventionist presented the following instruction: “At some point today I am going to have a social problem with you; when it happens, you can use the worksheet to help you solve it.” The participant was handed the blank worksheet alongside a pen/pencil. Participants were also told that they could call out their responses aloud if they did not want to write on the worksheet. At some point later in the session (between 5–15 min after reviewing how to use the worksheet), a social conflict was contrived between the interventionist and the participant. If the participant asked for help, they were told to do their best. Similar to baseline, no prompting, feedback, praise, or reinforcement was delivered. In addition, if any distressed behavior was observed for a duration of at least 10 s, the problem was ended by the interventionist resolving the social conflict. If the participant was not progressing through solving the problem after 1 min of the conflict occurring, the conflict was likewise ended by the interventionist resolving it. Participants qualified to continue to the training phase if they scored 60% or less on the problem-solving TA in pretraining. No participants were excluded from continued participation during this phase.

Training Phase

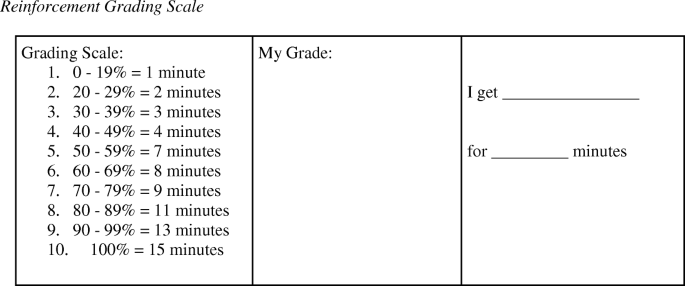

In addition to the general procedures, during training, the participant was taught to engage in precurrent behavior (i.e., use the worksheet) to resolve social conflicts using multiple exemplar training, error correction, and reinforcement. At the beginning of each session, an informal preference assessment was conducted by asking participants what they would like to earn after resolving a conflict. Then, the participant was told that they would be able to access the predetermined reinforcer for more or less time depending on how many questions of the worksheet they completed correctly. The amount of time that was granted with the reinforcer was determined using a grading scale in which higher percentages of independent correct responding on the worksheet resulted in more time with the reinforcer (see Fig. 2 ). For example, if the participant scored 20% correct on the problem-solving worksheet, they received 2 min of access to their reinforcer (e.g., video game, free time), and if they scored 90% correct they received 13 min of access. A social conflict was then contrived and each independently performed step of the TA was praised. Access to the predetermined reinforcer was granted for a prespecified amount of time depending on the participant’s percentage of correct responding.

Reinforcement grading scale

Incorrect responses resulted in re-presentation of the step followed by an immediate prompt using a least-to-most prompting hierarchy. The first prompt used was a gestural prompt, which consisted of the interventionist pointing to (in-person sessions) or highlighting with a cursor (telehealth sessions) the current step of the worksheet. If the gestural prompt did not result in a correct response, the step was re-presented with an immediate directive prompt. The directive prompt consisted of the interventionist saying, “Ask yourself [ step-related question ]” (e.g. “Ask yourself, ‘What is the problem?’”; “Ask yourself, ‘What do I think happened?’”) while pointing to the current step on the worksheet. If the directive prompt did not result in a correct response, the step was re-presented with an immediate leading-question prompt. Leading-question prompts were individualized for each conflict and each step of the TA. For example, “What is going on right now?” was used as a leading question for the first step of the worksheet (i.e., identifying the problem). If the leading question prompt did not result in a correct response, a choice prompt was presented. Choice prompts were also individualized for each conflict and each step of the TA using the following script: “Is the problem [ correct/irrelevant possibility ], or is the problem [ correct/irrelevant possibility ]?” (e.g., “Is the problem that we both want to go first [the problem], or is the problem that you need a place to sit?” [irrelevant to the problem]). A coin flip was used to randomize the order of correct/irrelevant choices provided. Finally, the most intrusive prompt provided was a full vocal model of the correct answer (e.g., “The problem is that we both want to go first.”). It was planned that if the participants came up with three nonviable solutions, the aforementioned prompting hierarchy would be used to prompt them to think of at least one solution that would work to solve the problem; however, all participants proposed at least one viable solution during training, so this was not needed. The criterion for ending the training phase was for the participant to respond with at least 80% accuracy for three consecutive sessions with the interventionist. After this, the posttraining phase was introduced.

Posttraining Phase

At the beginning of each posttraining session, a variation of the following instruction was presented, “Even if you can solve the problem by yourself without the worksheet, I need you to use the worksheet so that I know what you are thinking.” If participants began to resolve the conflict without using the worksheet, the instruction was re-presented. Other than the presence of that instruction, this phase was identical to baseline conditions, in that no feedback or reinforcement was provided at any point. Exemplars from baseline were re-presented during this phase (Table 3 ) to evaluate whether participants resolved social conflicts that they were unsuccessful in resolving prior to receiving the problem-solving training package.

Natural Environment Probes

Natural environment probes were used to evaluate problem solving in the absence of the worksheet. The first natural environment probe was conducted during baseline to evaluate participants’ problem-solving skills in the absence of the worksheet. During training, natural environment probes were contrived after participants scored at or above 80% correct on the problem-solving worksheet, with the exception of Oliver, who had a natural environment probe captured after the sixth training session. During posttraining, natural environment probes were graphed whenever captured. For example, if a naturally occurring social conflict arose at any time, it was captured as a natural environment probe. In addition, three consecutive natural environments probes were presented after completing posttraining sessions for all participants.

Follow-up natural environment probes were conducted at 2 (Patrick, Russell, and Oliver), 4 (Patrick and Russell), 6 (Patrick and Russell), and 10 (Patrick only) weeks posttraining to evaluate maintenance.

Social Validity

A social validity questionnaire (Table 4 ) was administered to each participant upon the completion of training. Participants were instructed to complete the questionnaire to the best of their ability and no additional feedback on their responses was provided. The questionnaire consisted of six questions (two each for goals, procedures, and outcomes; see Table 4 ) scored on a 5-point Likert scale: (1) strongly disagree, (2) disagree, (3) neutral, (4) agree, and (5) strongly agree. There were also two open-ended questions that asked participants to identify what they liked the most and least about the problem-solving training package.

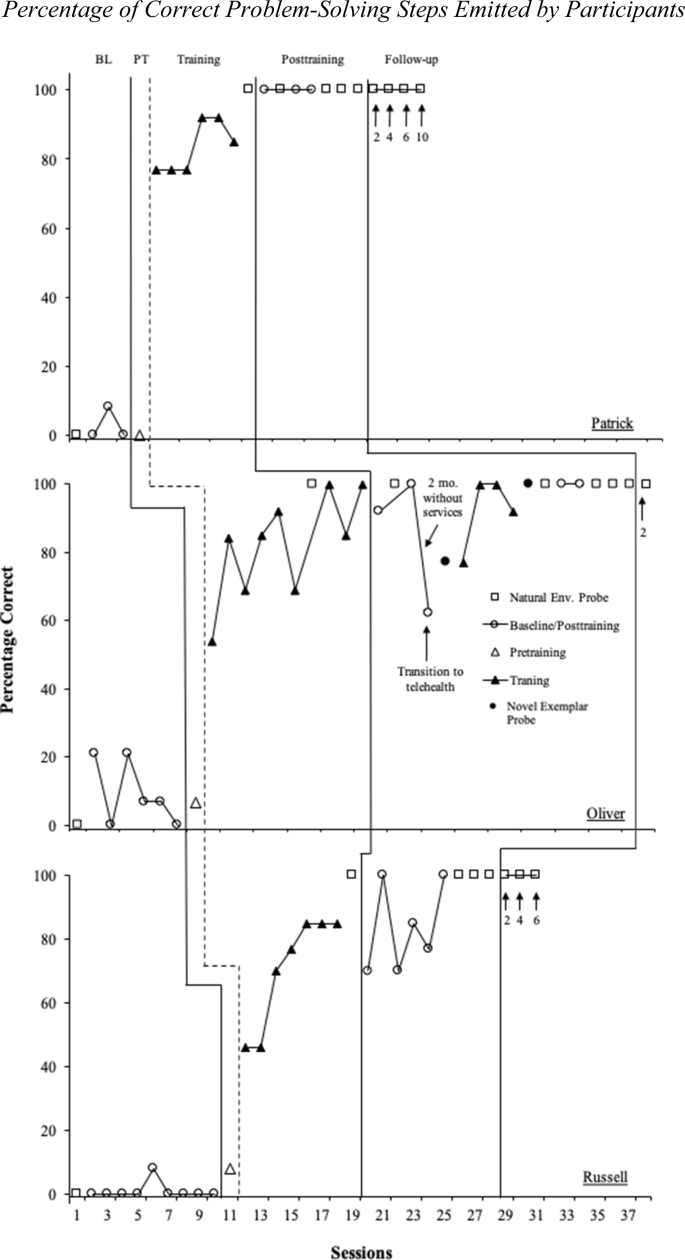

Figure 3 contains the results for Patrick (top panel), Oliver (middle panel), and Russell (bottom panel); these are described below, respectively. Patrick responded during baseline with 0%–8% accuracy in the presence of the worksheet and did not resolve the social conflict presented during the natural environment probe. During pretraining, Patrick performed with 0% accuracy in the presence of the worksheet. During training in the presence of novel problems, there was an immediate increase in correct responding, and he met the mastery criterion on the sixth training session. After training, during a natural environment probe (no worksheet), Patrick successfully resolved a contrived social conflict. During posttraining when untrained social conflict exemplars from baseline were repeated, Patrick consistently scored 100% using the problem-solving worksheet and also successfully resolved social conflicts during the natural environment probes (no worksheet). Maintenance was measured 2, 4, 6, and 10 weeks following training, and Patrick successfully resolved novel, naturally occurring social conflicts in the absence of a worksheet.

Percentage of correct problem-solving steps emitted by participants

Oliver responded with 0%–21% accuracy during baseline in the presence of the worksheet and did not resolve the social conflict presented during the natural environment probe. During pretraining, Oliver scored 7% correct in the presence of the worksheet. During training in the presence of novel problems, there was an immediate increase in correct responding, and he met the mastery criterion on the ninth training sessions. During session 15, we captured a naturally occurring social conflict, and Oliver successfully resolved it in the absence of the worksheet. During posttraining when untrained social conflict exemplars from baseline were repeated, Oliver scored 92%–100% correct and successfully resolved a social conflict during session 20 during a captured natural environment probe. After session 21, a 2-month period elapsed wherein Oliver did not receive services as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Upon returning to sessions using telehealth technology, Oliver scored 62% correct on the problem-solving worksheet under posttraining conditions. Because Oliver’s performance notably decreased, a novel exemplar probe under baseline conditions was conducted to determine if Oliver should receive a booster training session, and he scored 77% correct. The novel exemplar probe consisted of the presentation of a social conflict that had not been contrived at any other time in the study. Given that Oliver scored below 80% on the novel exemplar probe, Oliver was provided with booster training until he re-met the mastery criterion of 80%–100% correct across three consecutive sessions. The booster training conditions were identical to the training conditions. Then, another novel exemplar probe under baseline conditions was presented, and Oliver scored 100% correct. After this, a natural environment probe was captured in which Oliver successfully resolved a conflict in the absence of the problem-solving worksheet. Oliver scored 100% correct in the following session when he was presented with an untrained exemplar from baseline under posttraining conditions. Then, three natural environment probes were conducted and Oliver successfully resolved social conflicts in the absence of the worksheet. Maintenance was measured 2 weeks following posttraining in which Oliver successfully resolved a novel, naturally occurring social conflict in the absence of a worksheet.

Russell responded with 0%–8% accuracy during baseline in the presence of the worksheet and did not resolve the social conflict presented during the natural environment probe. During pretraining, Russell scored 8% correct in the presence of the worksheet. During training in the presence of novel problems, there was an immediate increase in correct responding, and he met the mastery criterion on the seventh training session. Moreover, Russell successfully resolved a contrived social conflict in the absence of the worksheet. During posttraining when untrained social conflict exemplars from baseline were repeated, Russell scored 70%–100% correct using the problem-solving worksheet and successfully resolved social conflicts in the absence of the worksheet. Maintenance was measured 2, 4, and 6 weeks following posttraining, and Russell successfully resolved novel, naturally occurring social conflicts in the absence of the worksheet.

Patrick and Russell scored the problem-solving training package as being highly acceptable with mean scores of 5 and 4.82, respectively. Oliver’s mean social validity score was 3.83. He scored “strongly agree” for one question and “agree” for three questions. The questions he scored as neutral included: (1) “I believe that I am better at solving social problems after participating in the social problem-solving lesson”; and (2) “I think that completing the social problem-solving lesson helped me solve social problems I have with my family/friends.” Patrick identified what he liked most about the training package was that it was helpful to him, and Oliver identified what he liked most was feeling like he was right. The only reported dislike about the training package was that it was tedious (Oliver).

The data from the current study suggest that multiple exemplar training, combined with a worksheet, was effective in teaching three individuals with ASD to resolve novel social conflicts occurring in the natural environment. In addition, generalization across untrained conflicts and people was observed from baseline to posttraining for all participants. These results are consistent with behavioral research conducted by Frampton and Shillingsburg ( 2018 ), Kisamore et al. ( 2011 ), Lora et al. ( 2019 ), Park and Gaylord-Ross (1989), and Sautter et al. ( 2011 ) in demonstrating that problem-solving strategies can be taught using behavioral strategies.

A noteworthy finding was that pretraining was insufficient to occasion the use of the worksheet during social conflicts. This finding is consistent with the behavioral skills training (BST) literature, which has shown instructions alone are generally ineffective compared to behavioral packages, such as BST (e.g., Feldman et al., 1989 ; Hudson, 1982 ; Ward-Horner & Sturmey, 2012 ). This finding is also consistent with previous problem-solving research that found modeling and prompting resulted in superior responding as compared to other strategies, such as teaching rules (Kisamore et al., 2011 ).

The results of this study are also consistent with previous research conducted by Bernard-Optiz et al. ( 2001 ) in demonstrating an increase in the use of novel solutions by individuals with ASD. In particular, the results showed that precurrent behaviors were successful in bringing a variety of solutions (not just one type of solution) under the control of the conflict context. For example, types of solutions used by participants included many different repertoires, some of which have not been addressed in previous research such as apologizing, providing information, advocating for individual needs/wants, compromising, and removing oneself from the situation, along with others that have been targeted in previous research, such as requesting information (e.g., Shillingsburg et al., 2011 ), requesting tangibles (e.g., Bourret et al., 2004 ), and requesting help/removal (e.g., Rodriguez et al., 2017 ; see Table 5 ). A potential limitation of this study is that we did not preplan the types of solutions we would teach, so exposure to types of solutions was not controlled for or counterbalanced. Therefore, it is possible that variation in the types of solutions used affected the results. However, consistent results were obtained across the three participants, so there is no direct evidence that inconsistency affected the results. In addition, training a variety of strategies, all of which have the same function, to solve the problem, may be considered a form of multiple exemplar training in itself, and therefore may have contributed to the favorable generalization that was observed. Still, uncontrolled variables are often frowned upon in research, so future researchers may want to consider controlling the number of each type of solution taught to participants.

This study expanded upon past research by capturing and contriving social conflicts within each participants’ natural environment. By conducting training with naturally occurring stimuli and “training loosely” (Stokes & Baer, 1977 ), generalization was promoted to ensure that participants acquired a repertoire for resolving social conflicts, rather than generating solutions only for specifically targeted conflicts. A compelling finding was that participants successfully resolved social conflicts in the absence of the worksheet during natural environment probes. Thus, the current study contributes to the literature by demonstrating that problem-solving strategies (i.e., worksheet use) can result in participants with ASD demonstrating successful generalization to untrained social conflicts occurring in the natural environment in the absence of a worksheet. The worksheet may be conceptualized as a prompt, that may have facilitated acquisition at first and was then no longer necessary to occasion the problem-solving chain of behaviors. Future research could consider teaching social conflict resolution in the absence of a worksheet, possibly by teaching each step of the problem-solving worksheet. Future research could also evaluate whether teaching a shorter problem-solving chain would be efficacious. For example, the last two steps of the worksheet could be omitted.

Continued successful problem-solving during natural environment probes also has implications for the possibility that some of the mediating behaviors previously cued by the worksheet were completed by participants on a covert level when the worksheet was no longer present. However, it is not possible to identify with any certainty whether participants were engaging in covert behavior. Given that participants were unsuccessful with resolving social conflicts during baseline, but were successful with resolving naturally occurring social conflicts after being trained to follow the problem-solving steps, and continued to resolve social conflicts effectively during posttraining, it seems possible that participants completed some of the steps on a covert level. In addition, after completing training, anecdotal observations found that participants engaged in overt behavior that suggested the possibility that they were engaging in covert completion of the steps, such as overtly saying, “You might think I am just not wanting to share the computer, but really I have been doing schoolwork all morning and just started my turn” (Step 3: What does the other person think happened?). It is also possible that participants engaged in visual imagining of the worksheet during natural environment probes. Skinner ( 1969 ) described precurrent behaviors of visual imagining in mathematical problem-solving and Kisamore et al. ( 2011 ) attempted to directly train visual imagining problem-solving behavior, so it is possible that the participants in this study engaged in covert imagining behavior. As with any covert behavior, it is not possible for researchers to directly measure it, but future research could attempt to train participants to observe and record their own covert verbal behavior, in order to provide an approximate measurement of the generalization of problem-solving repertoires to the covert level. For example, researchers might ask the participant, “How did you figure out how to solve that problem?,” to which a participant might respond with something like, “I imagined the worksheet in my head until I thought of the solution.” To the extent that participants are not directly trained to give specific verbal reports of this kind, such verbal reports might provide interesting supplementary data on the possibility of covert problem solving behavior.

It is interesting that all participants were observed to attempt to solve problems without using the worksheet in posttraining, although they were presented with the worksheet. In these instances, participants were reminded to use the worksheet. This indicated that participants had acquired problem-solving skills and no longer needed the worksheet; however, it was necessary to have participants use the worksheet in order to compare their posttraining performance to their baseline performance (because we could not measure their covert behavior to identify if they were implementing the problem-solving steps). Future research should evaluate methods to measure problem-solving skills in ways that allow participants to demonstrate their newly acquired skills without being limited by the apparatus/materials of the experiment. A possible solution could be to consider problem resolution as the primary dependent variable and evaluate pre- and posttraining data for conflict resolution following training in a problem-solving strategy.

We also found that emotional responding occasionally occurred upon presentation of social conflicts and possibly interfered with participants’ performance with resolving social conflicts. For example, Patrick was occasionally observed crying in response to a social conflict, which was followed by engaging in additional emotional self-regulation behaviors (e.g., take deep breaths, drink some water) and then successfully resolving the conflict. However, given that participants were successful in resolving social conflicts albeit experiencing emotional responding, the likelihood that emotional responses hindered learning problem-solving skills is low. Data were not collected on emotional responding; however, the team anecdotally observed that emotional responding decreased as participants learned to use the problem-solving worksheet. Future research should consider measuring emotional responding when teaching individuals to resolve social conflicts and may also investigate the role of emotion-regulation repertoires on problem-solving skills of individuals with ASD.

One potential limitation of the study is that we did not assess whether the trained problem-solving repertoires specifically came under the stimulus control of problems. Put another way, although the training procedure trained participants to identify problems and to discriminate which social situations were problems, we did not formally collect data on whether such discrimination was occurring. Although formal data were not collected on unnecessary or inappropriate application of problem-solving skills, the research team anecdotally reported that they never observed this to occur.

Another limitation of the study is that procedural fidelity data were not collected, so the degree to which procedures were implemented with fidelity is unknown. In addition, social validity information was not collected from family members. Given that social conflicts often occurred between the participants and their family members, future research could assess the family members’ impressions of the intervention by collecting social validity information from family members with whom conflicts typically occurred

Probably the most notable limitation of the study was that all solutions effectively resolved the current social conflict, because we primed the people who had social conflicts with the participants to make sure the participants’ solutions were successful. This was done by vocally instructing individuals present within the session that if a social conflict arose between them and the participant, they should allow whatever solution is presented by the participant to resolve the social conflict. In other words, whatever solution the participant proposed received functional reinforcement by the conflict being resolved. This was done to ensure the problem-solving sequence resulted in reinforcement; however, the schedule of reinforcement for problem solving in the natural environment is certainly not fixed. Future research should make a transition to a variable schedule of reinforcement when teaching problem-solving skills. In addition, when a strategy to resolve a conflict fails, one must engage in a subsequent behavior chain of problem solving. Therefore, future research should investigate the additional problem-solving steps required when an initial solution is unsuccessful.

Overall, the current study was successful in teaching three individuals with ASD to resolve social conflicts occurring in their every-day lives using a problem-solving worksheet, multiple exemplar training, error correction, rules, and reinforcement. In addition, the results of this study indicate that acquired skills for problem resolution successfully generalized to untrained social conflicts and maintained after training. The most notable aspect of the study was that the findings of this study indicate that overt precurrent behaviors, such as completing a worksheet, were not needed by participants to successfully resolve social conflicts after receiving training in engaging in such precurrent behaviors. As noted by Frampton and Shillingsburg ( 2018 ), it is important to identify efficacious methods for teaching complex skills, such as resolving social conflicts, that often occur at the covert level. Finally, it should be noted that according to traditional psychology, problem solving is associated with executive function (EF; Zelazo et al., 1997 ). In our clinical practice, skills associated with EF have become a requested repertoire to be targeted during behavioral intervention. For example, individualized educational planning (IEP) team members and parents have requested goals related to EF skills. The findings of this study demonstrate that behavioral procedures can be used to address a skill that is traditionally categorized as being an EF skill.

Agran, M., Blanchard, C., Wehmeyer, M., & Hughes, C. (2002). Increasing the problem-solving skills of students with developmental disabilities participating in general education. Remedial & Special Education, 23 (5), 279–288. https://doi.org/10.1177/07419325020230050301

Article Google Scholar

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed). Washington, DC.

Axe, J. B., Phelan, S. H., & Irwin, C. L. (2019). Empirical evaluations of Skinner’s analysis of problem solving. Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 35 (1), 39–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40616-018-0103-4

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bernard-Optiz, V., Sriram, N., & Nakhoda-Sapuan, S. (2001). Enhancing social problem solving in children with autism and normal children through computer-assisted instruction. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 31 (4), 377–384. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010660502130

Best, J. R., Miller, P. H., & Jones, L. L. (2009). Executive functions after age 5: Changes and correlates. Developmental Review, 29 (3), 180–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2009.05.002

Bonete, S., Calero, M. D., & Fernández-Parra, A. (2015). Group training in interpersonal problem-solving skills for workplace adaptation of adolescents and adults with Asperger syndrome: A preliminary study. Autism, 19 (4), 409–420.

Bourret, J., Vollmer, T. R., & Rapp, J. T. (2004). Evaluation of a vocal mand assessment and vocal mand training procedures. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 37 (2), 129–144. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.2010.93-455

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Feldman, M. A., Case, L., Rincover, A., Towns, F., & Betel, J. (1989). Parent education project III: Increasing affection and responsivity in developmentally handicapped mothers: Component analysis, generalization, and effects on child language. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 22 (2), 211–222. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1989.22-211

Frampton, S. E., & Shillingsburg, M. A. (2018). Teaching children with autism to explain how: A case for problem solving? Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 51 (2), 236–254. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.445

Garon, N., Bryson, S. E., & Smith, I. M. (2008). Executive function in preschoolers: A review using an integrative framework. Psychological Bulletin, 134 (1), 31–60. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.134.1.31

Hudson, A. M. (1982). Training parents of developmentally handicapped children: A component analysis. Behavior Therapy, 13 (3), 325–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(82)80041-5

Kisamore, A. N., Carr, J. E., & LeBlanc, L. A. (2011). Teaching preschool children to use visual imagining as a problem-solving strategy for complex categorization tasks. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 44 (2), 255–278. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2011.44-255

Lora, C. C., Kisamore, A. N., Reeve, K. F., & Townsend, D. B. (2019). Effects of a problem-solving strategy on the independent completion of vocational tasks by adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 53 (1), 175–187. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.558

Luciano, C., Gil-Luciano, B., Barbero, A., & Molina-Cobos, F. (2020). Perspective-taking, empathy, and compassion. In M. Fryling, R. Rehfeldt, J. Tarbox, & L. Hayes (Eds.), Applied behavior analysis of language and cognition: Core concepts and principles for practitioners . Context Press.

Google Scholar

Palmer, D. C. (1991). A behavioral interpretation of memory. In L. J. Hayes & P. N. Chase (Eds.), Dialogues on verbal behavior (pp. 261–279). Context Press.

Palmer, D. C. (2009). Response strength and the concept of the repertoire. European Journal of Behavior Analysis, 10 (1), 49–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/15021149.2009.11434308

Park, H. S., & Gaylord-Ross, R. (1989). A problem-solving approach to social skills training in employment settings with mentally retarded youth. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 22 (4), 373–380.

Rodriguez, N. M., Levesque, M. A., Cohrs, V. L., & Niemeier, J. J. (2017). Teaching children with autism to request help with difficult tasks. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 50 (4), 717–732. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.420

Sautter, R. A., LeBlanc, L. A., Jay, A. A., Goldsmith, T. R., & Carr, J. E. (2011). The role of problem solving in complex intraverbal repertoires. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 44 (2), 227–244. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2011.44-227

Shillingsburg, M. A., Valentino, A. L., Bowen, C. N., Bradley, D., & Zavatkay, D. (2011). Teaching children with autism to request information. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5 (1), 670–679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2010.08.004

Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior . Free Press.

Skinner, B. F. (1969). Contingencies of reinforcement: A theoretical analysis . Prentice-Hall.

Skinner, B. F. (1984). An operant analysis of problem solving. Behavioral & Brain Sciences, 7 , 583–613. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X0002741

Stokes, T. F., & Baer, D. M. (1977). An implicit technology of generalization 1. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 10 (2), 349–367. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1977.10-349

Szabo, T. (2020). Problem solving. In M. Fryling, R. Rehfeldt, J. Tarbox, & L. Hayes (Eds.), Applied behavior analysis of language and cognition: Core concepts and principles for practitioners . Context Press.

Ward-Horner, J., & Sturmey, P. (2012). Component analysis of behavior skills training in functional analysis. Behavioral Interventions, 27 (2), 75–92. https://doi.org/10.1002/bin.1339

Zelazo, P. D., Carter, A., Reznick, J. S., & Frye, D. (1997). Early development of executive function: A problem-solving framework. Review of General Psychology, 1 (2), 198–226. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.1.2.198

Download references

Acknowledgments

Victoria D. Suarez is Latina, Adel C. Najdowski is bi-racial: Latina and White, Jonathan Tarbox is White, Emma I. Moon is White, Megan St. Clair is White, and Peter Farag is Egyptian. We thank Jasmyn Pacheco, Lauri Simchoni, and Bryan Acuña for their assistance with this project.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Endicott College, Beverly, MA, USA

Victoria D. Suarez

Pepperdine University, Malibu, CA, USA

Adel C. Najdowski & Emma Moon

University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Jonathan Tarbox

Halo Behavioral Health, Valley Village, California, USA

Emma Moon, Megan St. Clair & Peter Farag

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Adel C. Najdowski .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained by all human participants using a consent form approved by Endicott College’s IRB.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Suarez, V.D., Najdowski, A.C., Tarbox, J. et al. Teaching Individuals with Autism Problem-Solving Skills for Resolving Social Conflicts. Behav Analysis Practice 15 , 768–781 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-021-00643-y

Download citation

Accepted : 05 August 2021

Published : 30 August 2021

Issue Date : September 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-021-00643-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Executive function

- Perspective taking

- Problem solving

- Social conflict

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Teaching Individuals with Autism Problem-Solving Skills for Resolving Social Conflicts

Behavior Analysis in Practice

Related Papers

Adrián Garrido Zurita

This study aims to examine the usefulness of an ad hoc worksheet for an Interpersonal Problem-Solving Skills Program (SCI-Labour) the effectiveness of which was tested by Bonete, Calero, and Fernández-Parra (2015). Data were taken from 44 adolescents and young adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) (age M = 19.73; SD = 3.53; 39 men and 5 women; IQ M = 96.27, SD = 15.98), compared to a matched group (in age, sex, and nonverbal IQ) of 48 neurotypical participants. The task was conceived to promote the generalization of interpersonal problem-solving skills by thinking on different possible scenarios in the workplace after the training sessions. The results show lower scores in the worksheet delivered for homework (ESCI-Generalization Task) in the ASD Group compared to neurotypicals in total scores and all domains (Problem Definition, Quality of Causes, and Solution Suitability) prior to program participation. In addition, after treatment, improvement of the ASD Group was observed i...

Proceedings of the 4th International ICST Conference on Pervasive Computing Technologies for Healthcare

Rosa I Arriaga , Jackie Isbell

... B. Related Wark Social skills training interventions are an important part of the education of children with Asperger's syndrome and HF ASD. ... Following the Social Story's, format this passage was presented on a sheet of paper with brightly colored icons. ... The m_ing sta rts soon.' ...

Journal of Autism and …

ΕΙΡΗΝΗ ΛΥΚΟΥ-ΧΑΪΔΗ

Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America

Patricia Prelock

Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders

Patrice Weiss

Angela Livingston

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is characterized by detrimental deficits in social communication and interaction, restrictive and repetitive patterns of behaviors, interest or activities. It is estimated that 70% of children with ASD suffer from uncontrollable behavioral outbursts that increase their peer isolation along with the stress of their caregivers. These uncontrollable and involuntary behaviors are stressful to the individual in many ways. This research study is being conducted to review the benefits of encouraging an increase in organized social activities between people with and without ASD in hopes that some of the uncontrollable behavioral outbursts that previously increased peer isolation will decrease or disappear over experience with organized social activities. Previous research on this study has been thoroughly reviewed and examined in order to gain a crucial understanding of this topic. The research potential from the interview style experiment will assist in future programs with the complete integration of children, adolescents, and young adults into the mainframe of society.

Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders

Revista de Investigación en Logopedia

Numerous studies reveal the benefits of early intervention for the adequate development of children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Most of the interventions designed for people with ASD focus exclusively on a sole methodology. This study proposes a Combined Early Intervention Program (hereafter CEIP) using different methodologies with scientific evidence: Early Intensive Behavioral Interventions (EIBI), Early Start Denver Model (DENVER), spatial-temporal organization (TEACCH), augmentative communication systems (the Picture Exchange Communication System—PECS—, Total Communication Program, Picture Communication Symbols—PCS), behavioral strategies, and training of the parents. This CEIP contemplates intervention in areas that are typically affected in ASD: socialization, communication, symbolization, and behavioral flexibility, producing considerable improvement in the children's behavior, decreasing problem behaviors and improving social communication.

Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools

Linda R Watson

Purpose This study aimed to examine the initial efficacy of a parent-assisted blended intervention combining components of Structured TEACCHing and Social Thinking, designed to increase social communication and self-regulation concept knowledge in 1st and 2nd graders ( n = 17) diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and their parents. Method A randomized delayed treatment control group design with pre- and postintervention assessments of both parents and children was implemented within a community practice setting. Two follow-up assessments at 3 and 6 months postintervention were also completed. Results Overall, results indicate that the intervention is efficacious in teaching social communication and self-regulation concept knowledge to children with ASD and their parents. Both parents and children demonstrated an increase in social communication and self-regulation knowledge after participating in the Growing, Learning, and Living With Autism Group as compared to a delayed t...

Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis

Lynn Koegel

RELATED PAPERS

Transplantation Proceedings

Maria Dudziak

Materials Sciences and Applications

Djeribaa Abdeldjalil

Nisa Dwinanda

Didaktik : Jurnal Ilmiah PGSD STKIP Subang

Alif Syafitri

怎么购买美国亚利桑那大学毕业证 ua学位证书硕士文凭证书GRE成绩单原版一模一样

Pramod Parajuli

Journal of Electrochemical Science and Technology

Florian Hilpert

Cadernos UniFOA

Omar Franklin Molina

Transplantation

Adolfo Garcia Gutierrez

Buck Quarles

International Journal of Nuclear Security

Amr R. Kamel

Giuseppe Turrisi

Alan Chadwick

JOINTS Vol. 9 No. 1 (2020): April 2020

Journal Orthopaedi and Traumatology Surabaya

Dheepa Balasubramanian

ghkgf gfhrg

Journal of Vascular Access

Nyla Ismail

Spanish Journal of Agricultural Research

Angela Contreras

JOURNAL OF SUSTAINABILITY SCIENCE AND MANAGEMENT

Izwandy Idris

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Back issues

Home » Autism Parenting Advice » Teaching Autistic Children Critical Thinking Skills

Teaching Autistic Children Critical Thinking Skills

By Donnesa McPherson, AAS

October 21, 2022

What is so important about teaching autistic children critical thinking skills? These skills are important to everyday decisions and obstacles an individual may face, there are many neurotypical and neurodivergent individuals that have a hard time with these skills.

This article is going to outline abstract and conceptual thinking skills development, practice, and use in the school setting and at home. I plan on including ways that both parents and teachers will best be able to encourage and build these skills in children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

It may take some creativity and thinking outside the box when interacting and teaching these skills. It is important to remember and take note of the differences and potential difficulties that your child may have when taking these ideas into consideration.

As always, these are merely the tip of the iceberg and may not work for everybody. That is why the ability of parents and educators to think outside the box and use their own critical thinking skills when figuring out what will work best for the child.

Neurodivergence, autism, and critical thinking skills

It has been thought that neurodivergent children, particularly autistic children, have a harder time with an abstract idea. In the article, Associations Between Conceptual Reasoning, Problem Solving, and Adaptive Ability in High-functioning Autism, they state that this thought is not entirely correct and cannot cover the spectrum that autism covers.

For instance, the article states that there are children that have learned some conceptual reasoning skills, along with abstract thinking in a therapy or school setting and do well. Then when they go about their everyday lives they tend to forget or have a hard time applying these skills to everyday occurrences.

There are also autistic children who have no need to further their problem solving and conceptual skills. As I stated, with the spectrum that autism falls under, it can be challenging to address all the differing areas of development in these areas.

Ways to promote and enhance abstract and conceptual thinking skills

In this section I will mainly focus on ways of developing these skills in the classroom environment. Also, what alterations and support can be put in place to help the individuals develop these skills.

Problem solving and critical thinking development in the classroom

The presentation, Understanding Autism Professional Development Curriculum: Strategies for Classroom Success and Effective Use of Teacher Supports, starts with explaining what autism is and moves into what affects the autistic students and ways to help and support these students.

What can affect the student with autism?

- Unpredictability this can be daunting and even a little scary for a student that may rely on knowing what they should expect next when school events, like an unexpected pep rally in the loud gym, can be met with extreme difficulty and be more of a stressful event than something fun

- Transitions knowing what is coming up next and have the time to prepare for these transitions can be key with some students keeping transitions and how they are handled in mind can help decrease difficult behaviors before they begin by making it easier for the student to transition smoothly

- Environmental changes these changes can be anything from seating changes to adding a new plant to the classroom and can stimulate certain sensory sensitive individuals or be an unwelcome surprise they were not ready for

- Sensory overload if a student is exhibiting unusual or difficult behaviors, it can occur from all the sounds in the hallway to the buzzing from the lights and can affect the individual that may have a sensitive sensory response

- Sensory seeking these students need some type of sensory stimulating activity, or could be the individuals that need to move around during discussion because that is how their brain best functions

- Navigation it can be confusing, especially if the student has any of the various communication difficulties and may lack the social skills needed to ask when navigating from classroom to classroom or learning center to learning center and can be further irritated by loud and unexpected sounds of voices and chairs scraping the floor

- Expectations not knowing what is expected of them, if the student is still developing social skills they may not do what is asked because they are unsure of what the expectations were before the activity and/or task and are unaware of how to ask appropriately

- Decision making if given too many possibilities for decisions, the student may become confused and irritated because they don’t know what to do and there are too many choices that have been presented to them

Ways to help and support these students

- Provide structure and consistency organizational skills are so important when it comes to this step because it can require a posted classroom schedule and one that the students also have in their notebooks that they can refer to, if needed try to stay clear of visual clutter, as that can cause more confusion

- Make information and supplies readily accessible label where items, homework, lessons, etc. go for the day don’t forget to verbally explain and show the students where they can find these areas and labels, if they haven’t been introduced

- Predictability this is where having a schedule and following it helps and is a nice starting point also having different tools and visual supports that are easily accessible to the student makes it easier for them to use and understand

- Consider potential distractions try to remember that open windows, fluorescent lighting, strong smells, and loud noises can be extremely distracting and are a few of the things that can affect a sensory sensitive student keeping these distractions down or altering them in a friendlier way can help the individual with paying attention to the task at hand

- Provide plenty of visual supports visual supports are your friend and ones that are interactive, more so for younger students but can benefit older students who like the sensory stimulation when the student physically removes a piece to the complete side or has a visual schedule in front of them and knows to expect gym class after recess

What are five ways that teachers can support critical thinking in the classroom?

Whether the student is in a general education classroom or special education program, there are five ways that teachers and teaching aids can help support students:

- Expose and prepare this a way that the teacher or aid could show and talk about the assignment before the assignment is taught and helps expose the student to the material and prepare them for what is going to be expected of them and what the assignment will entail

- Provide and plan for necessary adaptations for the student if the student already has an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) there could be modifications and adaptations already outlined

- Visual supports these could be token charts that allow the student to interact and add tokens when they have accomplished something all the way to an interactive visual board that the student carries around, to a visual schedule that changes as the tasks change throughout the say letting the students know what to expect next

- Reinforcement the reinforcement discussed here is a way of rewarding the child for following school rules, finishing assignments, interacting with other students, or whatever they are working on for the moment

- Offer a safe space this is an area where the student can decompress and can either be a place where they go by themselves when they become overwhelmed

Free your mind

As a parent, it can be difficult changing around your thought patterns and expectations when it comes to different aspects of your child and what is being expected of them. It is an important thing to remember, though, that as your child is learning all kinds of things like new ways to interact in a more socially acceptable way to keep all your interactions as light and fun as possible.

As a parent you can look at things in a creative way. This can be fun and add a sense of adventure to how you and your child continue to learn and respond, especially when it comes to critical thinking, abstract skills, conceptual skills, and problem solving skills.

For instance, if you know your child doesn’t like doing their school work at the table, you can ask them where they would like to do their school work, be careful and avoid verbal overload by talking too long. It is best to keep to shorter sentences and questions and offer two to three potential answers.

If they say they would prefer to practice spelling on the couch, just make sure to minimize distractions and voila they have a new place to do work and where able to practice some abstract concepts to where homework can be done.

In her article, 3 Simple Habits to Improve Your Critical Thinking, Helen Lee Bouygues states three ways of improving critical thinking, and they are things parents can do at home to practice with their children!

What are the three things that parents can do at home to help these skills?

- Ask questions this can seem super simple, but the act of asking and answering repetitive verbal questions can help build problem solving skills because the child has to use their thinking skills and reason with the question to come up with potential answers

- Be logical if your child is very logical, this exercise could help them expand beyond their logic, although they would start with logic, and expand as you both come up with more questions and concepts to talk about

- See things differently you and your child have had a discussion about homework and they have figured out that they can do spelling practice on the couch, maybe come up with what other subjects may be done on the couch? Or where else could be a good place to practice spelling words and find out that they love spelling while swinging on their sensory swing.

Key takeaways

There are many ways that teachers and parents can both support and help develop critical thinking and other skills that will help the student in their future. Some of these ideas include ways that the classroom can help or hinder development and education.

Also, challenging parents to think outside the box when helping develop thinking skills and those needed for problem and organizational solving on a daily basis. Although there are children that may be able to express these skills during some times and forget about them during daily tasks, practice can help further the skill set.

As with anything else in life, practice can make perfect. Or, it can at least help by making steps toward the ultimate goals of using these skills as a student and beyond.

Bouygues, H. (2019). 3 Simple Habits to Improve Your Critical Thinking. https://hbr.org/2019/05/3-simple-habits-to-improve-your-critical-thinking

Goldstein, G., Mazefsky, C., Minshew, N., Walker, J., Williams, D. (2018). Associations Between Conceptual Reasoning, Problem Solving, and Adaptive Ability in High-functioning Autism. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6067678/

The Center on Secondary Education for Students with Autism Spectrum Disorders & Organization for Autism Research. Understanding Autism Professional Development Curriculum: Strategies for Classroom Success and Effective Use of Teacher Supports. https://csesa.fpg.unc.edu/sites/csesa.fpg.unc.edu/files/imce/other/Presentation%202%20(Strategies%20for%20Classroom%20Success%20and%20Effective%20Use%20of%20Teacher%20Supports)(2).pdf

Support Autism Parenting Magazine

We hope you enjoyed this article. In order to support us to create more helpful information like this, please consider purchasing a subscription to Autism Parenting Magazine.

Download our FREE guide on the best Autism Resources for Parents

Where shall we send the PDF?

Enter you email address below to download your FREE guide & receive top autism parenting tips direct to your inbox

Privacy Policy

Related Articles

How to Help Your Autistic Child Relax After School

Which pets are best for children with autism, 5 tips for moving with a child on the autism spectrum, how to explain autism to a child who’s diagnosed, 7 things to do when you lose patience with an autistic child, 11 things not to do with an autistic child, fear: from a single parent’s perspective, the link between autism and temperature regulation, how to choose the best autism stim toys, long-term planning for your child with autism, what is an autism coach, and why you might need one, choosing an autism babysitter: 10 things to consider, privacy overview.

Get a FR E E issue

of the magazine & top autism parenting tips to your inbox

We respect the privacy of your email address and will never sell or rent your details.

Autism Parenting Magazine

Where shall we send it?

Enter your email address below to get a free issue of the magazine & top autism tips direct your inbox

News and Knowledge

Read the latest issue of the Oaracle

Teaching Autistic Students to Solve Math Word Problems

August 29, 2022

By: Jenny Root, Ph.D., BCBA

Categories: How To , Education

In the past three months, how many times have you had no choice but to use cash to make a purchase? Or tell time using an analog clock?

Although you have undoubtedly made purchases, it is likely you used a card or smart device, especially if the purchases were made online. To check the time, you probably glanced at a digital clock on a screen or even just asked Alexa, Google Home, or another artificial intelligence device.

While the functions of many activities of daily living, such as making purchases and telling time, have remained the same over time, how we accomplish these tasks has changed dramatically as technology has evolved.

Math instruction for autistic students has historically had a limited focus on “functional” skills in order to prepare them for independence in their adult lives. Yet in addition to mastering a series of discrete skills, autistic young adults need to be able to problem solve . This includes:

- Being aware of when there is a problem.

- Identifying a reasonable strategy.

- Monitoring their progress accurately.

- Adapting as necessary.

Word problem solving is one way to teach students how, when, and why to apply math skills in real-world situations they will encounter in a future we may not be able to envision yet.

These research-supported strategies can help teachers and parents teach autistic students to solve word problems using modified schema-based instruction (MSBI). MSBI is an evidence-based practice for teaching word problem solving.

Create a meaningful task.

Word problems need to depict a realistic and meaningful problem. This will help students better understand the “why” behind word problem solving and support generalization to everyday situations. You can begin planning by identifying high-interest, real-world contexts when the targeted math skills could be used, such as familiar community locations, family routines, or preferred activities. The quantities represented in the problem should be realistic for the situation. Use technology to build background knowledge for generalization by showing short videos or pictures, such as videos of people making purchases using a credit card or comparing rideshare costs between two apps.

Consider accessibility.

Both the materials and word problems themselves need to be accessible to students. The reading level, quantities represented, structure, and visual supports can all be adjusted to address barriers students may face. If independently reading the problem is a barrier, students can use technology to access text-to-speech or ask a skilled reader—a parent, peer, or teacher—to read it aloud to them. Quantities in the problem can be reduced to match a student’s numeracy skills (e.g., quantities under 10) or they can be provided with a calculator for efficiency.

Research has shown that autistic students can successfully fade this equation template once they become fluent in problem solving.

Focus on problem types, not keywords or operations.