An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

The Effect of Supportive Implementation of Healthier Canteen Guidelines on Changes in Dutch School Canteens and Student Purchase Behaviour

Irma j. evenhuis.

1 Department of Health Sciences, Faculty of Science, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam Public Health Research Institute, De Boelelaan 1085, 1081 HV Amsterdam, The Netherlands; ln.htyvsille@ofni (E.L.V.); [email protected] (M.R.d.B.); [email protected] (J.C.S.); [email protected] (C.M.R.)

Suzanne M. Jacobs

2 Netherlands Nutrition Centre, PO Box 85700, 2508 CK The Hague, The Netherlands; ln.murtnecsgnideov@sbocaj (S.M.J.); ln.murtnecsgnideov@siuhdlev (L.V.)

Ellis L. Vyth

Lydian veldhuis, michiel r. de boer, jacob c. seidell, carry m. renders.

We developed an implementation plan including several components to support implementation of the “Guidelines for Healthier Canteens” in Dutch secondary schools. This study evaluated the effect of this plan on changes in the school canteen and on food and drink purchases of students. In a 6 month quasi-experimental study, ten intervention schools (IS) received support implementing the guidelines, and ten control schools (CS) received only the guidelines. Changes in the health level of the cafeteria and vending machines were assessed and described. Effects on self-reported purchase behaviour of students were analysed using mixed logistic regression analyses. IS scored higher on healthier availability in the cafeteria (77.2%) and accessibility (59.0%) compared to CS (60.1%, resp. 50.0%) after the intervention. IS also showed more changes in healthier offers in the cafeteria (range −3 to 57%, mean change 31.4%) and accessibility (range 0 to 50%, mean change 15%) compared to CS (range −9 to 46%, mean change 9.7%; range −30 to 20% mean change 7% resp.). Multi-level logistic regression analyses on the intervention/control and health level of the canteen in relation to purchase behaviour showed no relevant relations. In conclusion, the offered support resulted in healthier canteens. However, there was no direct effect on students’ purchase behaviour during the intervention.

1. Introduction

To support adolescents to make healthier food choices, many national governments have formulated food policies to encourage a healthy offering of foods and drinks in schools and their canteens [ 1 ]. To create healthier canteens, nudging strategies are used, by which the healthier option is made easier without restricting the freedom of choice [ 2 ]. Such strategies focus on availability and accessibility by offering mainly healthier products, discouraging the consumption of unhealthy foods by making them less readily available, making the healthier option the default, and promoting healthier products [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ]. Evaluations of such strategies show improvements in food and drinks offered in schools, which is likely to influence students’ consumption of healthier foods and drinks [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ]. However, these results are only seen when the policy is implemented adequately [ 8 , 9 ], which can be increased with supportive implementation tools [ 10 , 11 , 12 ]. The provision and type of such tools differ within and across countries, though training, modelling, continuous support such as helpdesks and incentives are commonly provided [ 12 ].

In the Netherlands, most schools have no tradition of offering school meals, but do offer complementary foods and drinks in a cafeteria and/or vending machines. Most students bring their lunch from home, and buy additional food and drinks at school, or at shops around the school [ 13 ]. The national Healthy School Canteen Programme of the Netherlands Nutrition Centre, financed by the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sports, provides schools with free support to create healthier canteens (cafeteria and/or vending machine) [ 14 , 15 , 16 ]. This includes, for example, a visit and advice from school canteen advisors (i.e., nutritionists), regular newsletters, and a website with information about and examples of healthier school canteens. The programme has been shown to lead to greater attention to nutrition in schools and a small increase in the offering of healthier food and drinks in the cafeterias, but not in vending machines [ 15 , 17 , 18 ]. However, until then, the programme only included availability criteria.

Based on literature and in collaboration with future users and experts in the field of nutrition, the Netherlands Nutrition Centre developed the “Guidelines for Healthier Canteens” in 2014, and updated them in 2017 [ 19 ]. These guidelines include criteria on both the availability and accessibility of healthier foods and drinks (including tap water) and an anchoring policy. The guidelines distinguish three incremental health levels: bronze, silver and gold [ 19 ]. Only silver (≥60%) and gold (≥80%) are qualified for the label “healthier school canteen”. These guidelines define healthier products as food and drinks recommended in the Dutch Wheel of Five Guidelines, and products that are not included but contain a limited amount of calories, saturated fat and sodium [ 20 ]. To increase dissemination of the guidelines, an implementation plan was developed, based on experience within the Healthy School Canteen Programme and in collaboration with involved stakeholders from policy, practice and science [ 21 ]. This study investigated the effect of this implementation plan to support implementation of the Guidelines for Healthier Canteens in schools on both changes in the health level of the canteen and in purchase behaviour of students. Moreover, the relation between the health level of the canteen and purchase behaviour is determined.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. study design.

The effect of the implementation plan was evaluated in a 6 month quasi-experimental controlled trial with 10 intervention and 10 control schools, between October 2015 and June 2016. The control schools were matched to intervention schools on the pre-defined characteristics: school size (fewer or more than 1000 students); level of secondary education (vocational or senior general/pre-university); and how the catering was provided (by a catering company or the school itself). Additionally, we aimed to match the control schools to intervention schools on contextual factors: the availability of shops near the school and the presence of school policy to oblige students to stay in the schoolyard during breaks. Intervention schools received support to implement the Guidelines for Healthier Canteens according to the plan (the intervention), while control schools received only general information about the guidelines, although they also received the support after the intervention period. Further details about the study design are provided in the study protocol [ 22 ]. This study was registered in the Dutch Trial Register (NTR5922) and approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the VU University Amsterdam (Nr. 2015.331).

2.2. Study Population

The schools, in western and central Netherlands, were recruited via the Netherlands Nutrition Centre and caterers. Inclusion criteria were (a) presence of a cafeteria, (b) willingness to create a healthier school canteen, and (c) willingness to provide time, space and consent for the researchers to collect data from students, employees and canteen workers. The exclusion criteria were (a) the school had already started to implement the Guidelines for Healthier Canteens, and (b) the school had already received personalized support on implementing a healthier canteen from a school canteen advisor from the Netherlands Nutrition Centre in 2015. In all participating schools, we recruited students per class. In each school, we recruited 100 second or third-year Dutch-speaking students (aged 13–15 years), equally distributed over the school’s offered education levels. Parents and students received information about the study and the option to decline participation. Figure 1 shows the flow diagram of the inclusion of the schools and students.

The CONSORT flow diagram of the present study [ 23 ].

2.3. Intervention

The intervention consisted of the implementation plan to support schools in creating a healthier school canteen, as defined by the Guidelines for Healthier Canteens. This plan was developed in a 3-step approach based on the “Grol and Wensing Implementation of Change model” [ 24 ] in collaboration with stakeholders, as described elsewhere [ 21 ], and delivered by school canteen advisors of the Netherlands Nutrition Centre, in collaboration with researchers of the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

The intervention started with gaining insight into the context and current situation of the school and the canteen. For this purpose, involved stakeholders (e.g., teacher, school management, caterer, canteen employee) filled out a questionnaire on the schools’ characteristics (educational level, number of students) and their individual (e.g., knowledge, motivation) and environmental (e.g., need for support, the innovation) determinants. School canteen advisors also measured the extent to which canteens met the Guidelines for Healthier Canteens, using the online tool “the Canteen Scan” [ 25 ]. Based on these findings, school canteen advisors provided tailored advice in an advisory meeting where all involved stakeholders discussed aims and actions to achieve a healthier canteen. Stakeholders also received communication materials about the Guidelines for Healthier Canteens, including a brochure with examples of, and advice on, how to promote healthier products. All stakeholders of all intervention schools were invited to a closed Facebook community to share experiences, ask questions and to support each other. In addition, to remind and motivate stakeholders, a newsletter with information and examples was sent by email once every 6 weeks. Finally, to gain insight into their students’ opinion, students were asked to fill in a questionnaire (the same as used for the effect evaluation), and the results were fed back to schools in an attractive fact sheet.

2.4. Measurements

Measurements in the school canteens and among students were performed before and directly after the intervention period. The “health level” of the school canteen was measured in all participating schools using the online Canteen Scan [ 25 ], filled out by a school canteen advisor. The tool has been evaluated satisfactorily on inter-rater reliability and criterium validity if measured by a school canteen advisor, scoring > 0.60 on Weighted Cohen’s Kappa [ 22 ]. Only intervention schools received the results of the Canteen Scan as part of the intervention.

Students reported their purchases via an online questionnaire filled out in a classroom under supervision of a teacher and/or researcher. Data on demographics and behavioural and environmental determinants were also collected [ 26 ]. The questions were derived from validated Dutch questionnaires [ 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 ], and the questionnaire was pretested for comprehensibility and length in a comparable population using the cognitive interview method think-aloud [ 32 ].

2.4.1. Health Level of the School Canteen

The Canteen Scan assessed the extent to which a canteen complies with the four subtopics of the Guidelines for Healthier Canteens: (1) a set of four basic conditions for all canteens, (2) the percentage of healthier foods and drinks available in the cafeteria (at the counter, display, racks) and (3) in vending machines and (4) the percentage of accessibility for healthier food and drink products [ 19 , 25 ]. According to these guidelines, a canteen is healthy if all basic conditions are fulfilled, if the percentage of healthier foods and drinks available is at least 60% in the cafeteria and in vending machines, if fruit or vegetables are offered, and if the percentage of fulfilled accessibility criteria is also at least 60%. As the basic conditions overlap with the availability and accessibility scores, this subtopic was not used in the analyses. For the other three subtopics, the change between pre- and post-measurement was calculated for each school.

In the Canteen Scan, all visible foods and drinks available in the cafeteria (counter, display, racks) and in vending machines were entered. The scan automatically identifies whether, according to the Dutch Wheel of Five Guidelines [ 30 ], an entered product is healthier or less healthy, and calculates the percentage of healthier products. In addition, to assess the accessibility for healthier foods and drinks, nine criteria (8 multiple choice, 1 multiple answer options) were answered, creating a score ranging from 0 to 90%. These questions relate to the attractive placement of healthier products in the cafeteria and vending machines; the offer at the cash desk; the offer at the route through the cafeteria; fruit and vegetables presented attractively; promotions for healthier products only; mostly healthier items at the menu/pricelist; and advertisements/visual materials only for healthier products. Questions include, for example, “Are only healthier foods and drinks offered at the cash desk?” and “Are fruit and vegetables presented in an attractive manner?”

2.4.2. Self-Reported Purchase Behaviour of Students

Purchase behaviour was measured by assessing the frequency of purchases per food group (sugary drinks, sugar free drinks, fruit, sweet snacks, etc.) over the previous week, for the cafeteria and the vending machines separately. If students stated that they had bought less than once per week, they answered the frequency of purchases in the last month. Students who did not buy anything at both time points were excluded ( n = 192), as they do not provide information about the relation between the intervention and their purchases. Groups of foods and drinks were considered as healthier or less healthy, as defined by the Dutch Wheel of Five Guidelines [ 20 ]. All reported healthier purchases in the cafeteria and vending machines, respectively, were summed, as were the less healthy purchases. As the data were not normally distributed, we dichotomised the variable. Frequencies of the pre- and post-intervention survey were subtracted and categorized into the dichotomous variable indicating a healthy or unhealthy change in purchase behaviour. A healthy score was defined as (1) a higher increase in healthier products compared with less healthy products; (2) a higher decrease in less healthy products compared with healthier products; or (3) purchases remained stable over time and consisted mainly of healthier products. An unhealthy score was defined as (1) a higher increase in less healthy products compared with healthier products; (2) a higher decrease in healthier products compared with less healthy products; (3) purchases remained stable over time and consisted mainly of less healthy products or an equal number of healthier and less healthy products.

2.4.3. Other Student Variables

Demographic student variables included age (in years), gender and current school level (vocational (i.e., VMBO), senior general education (i.e., HAVO) or pre-university education (i.e., VWO)). Determinants of purchase behaviour included attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioural control and intention, all towards buying healthier products at school. For each variable, multiple questions (range 2–5) were asked on a 5-point Likert scale (answers ranging from, e.g., 1 = very unlikely to 5 = very likely) derived from existing validated Dutch questionnaires [ 27 , 28 ]. The mean score of each variable was calculated and the reliability of the measurements was assessed with Cronbach’s alpha [ 33 ]. The measured environmental determinants were having breakfast (Yes, No); amount of money spent on food/drink purchases at school per week (<€1, €1–2, ≥€2); external food/drink purchase behaviour (<1 times p/w, 1–3 times p/w, ≥4 times p/w); and foods/drinks brought from home (<4 times p/w, ≥4 times p/w).

2.5. Sample Size

The sample size was calculated based on the outcome purchase behaviour, an expected 10% drop out, 80% power and 5% significance level [ 34 ]. The calculation showed that 20 schools and 100 students per school were necessary to be able to detect a 10% difference in purchase behaviour of students (continuous variable), with the expected multi-level structure (students within schools, intra-class correlation of 0.05).

2.6. Statistical Analyses

Student baseline characteristics and pre- and post-intervention canteen outcomes and student purchase behaviour were described by means and standard deviations. Canteen outcomes included three subtopics of the health level of the canteen: healthier food and drinks available in the cafeteria, in the vending machines and accessibility of healthier food and drinks. Mean (SD) pre- and post-intervention values and mean changes were described and changes in the subtopics per school were presented in a chart.

A mixed logistic regression analysis [ 35 ] was performed to investigate the effect of the intervention (independent variable) on purchase behaviour (dependent variable). Correlated errors of student scores (level 1) nested within schools (level 2) were taken into account by including a random intercept for schools in all analyses (model 1). The analyses were stratified by gender, as boys seems to react more to environmental changes than girls [ 36 ]. Models were first extended with demographic variables (model 2), secondly with students’ behavioural determinants (model 3) and thirdly with students’ environmental determinants (model 4).

The effect of a healthier canteen (independent variable) on student purchase behaviour (dependent variable) was also assessed using mixed logistic regression analyses with a random intercept for schools for boys and girls separately. We used the health level of the canteen at follow-up for each of the three subtopics of a healthier canteen. Due to non-linearity with student purchase behaviour, again a dichotomous variable was created, based on the guidelines, which state that 60% or higher is a healthier availability and accessibility, respectively. Again, the model was extended with demographic variables (model 2) and students’ behavioural (model 3) and environmental determinants (model 4). Statistical analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics version 24.0 (IBM corporation (IBM Nederland), Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI’s) are presented.

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

We included data from 645 students of the intervention schools and 731 students of the control schools in the analyses ( Table 1 ). Both groups consisted of more girls than boys (56% and 53%, respectively). The included schools offered education at the vocational ( n = 6) level, the senior general/pre-university level ( n = 5), or a combination of both levels ( n = 9). The level of education was broadly similar for intervention and control schools. However, in intervention schools, slightly more girls followed the vocational education level (46.6%) compared to boys (41.4%), while the opposite was the case in control schools (girls, 39.5%; boys 46.2%). Most students indicated that they did bring food and drinks from home to school four or more times a week (for food, intervention schools (IS) 91.8 and control schools (CS) 89.2%; for drinks, IS 90.4% and CS 88.5%). The majority of students reported that they bought foods or drinks in the school cafeteria (IS 55.5%; CS 64.4%) or vending machine (IS 63.6%; CS 61.1%) less than once per week. During school time, 62.2% and 67.6% of the students in the IS reported buying food or drinks outside school less than once a week, compared to 65.6% and 73.6% in the CS.

Baseline characteristics of students divided by intervention or control school and gender.

a Per variable, multiple questions (range 2–5) were asked on a 5-point Likert scale (answers ranging from 1 = very unlikely to 5 = very likely). b This variable was not used as confounder in the multi-level analyses due to the similarity with the outcome variable purchase behaviour per week. c On this variable, the control group has 40 students less (19 boys, 21 girls) as one school did not have a vending machine.

3.2. Intervention Effect on Health Level of the Canteen

Table 2 shows that intervention schools (IS) scored higher in terms of the healthier offering in the cafeteria (77.2%), compared to control schools (CS) (60.1%) after the intervention. Figure 2 confirms this and shows that nine of the ten IS increased the healthier offering (range of all IS: −3 to 57%, mean change 31.4%). In comparison, eight of the ten CS showed positive changes but the change (range of all CS: −9 to 46%, mean change 9.7%) was smaller compared to the IS. The healthier offering in vending machines increased in five of the ten IS (range of all IS: −15 to 33%, mean change 5.1%) and in three of the nine CS (range al all CS: −14 to 48%, mean change 5.3%) ( Figure 3 ), although, on average, both groups made broadly similar changes in their offer ( Table 2 ). With regard to the accessibility criteria, both groups showed overall increases, although two CS also showed decreases ( Figure 4 ). The change in IS was higher compared to CS (range of all IS: 0 to 50%, mean change 15%; range of all CS −30 to 20%, mean change 7%), resulting in mean scores of 59% (IS) and 50% (CS) fulfilled accessibility criteria after the intervention.

Histogram of the changes in healthier products available in the cafeteria.

Histogram of the changes in healthier products available at vending machines.

Histogram of the changes in fulfilled accessibility criteria.

Subscores of a healthier canteen pre- and post-intervention, stratified by intervention and control schools.

a Mean score (SD). b Scores in percentage (0–100%). c One control school did not have a vending machine ( N = 9, in control schools). d Nine criteria could be fulfilled, scoring 10% per criteria (0–90%).

3.3. Purchases in the Cafeteria

Data on self-reported purchase behaviour at the cafeteria were included in the analysis from 1213 students (548 boys, 665 girls) ( Table 3 ). Mean purchases of all foods and drinks per week varied between 0.46 and 1.72 per person. Both boys and girls bought more “less healthy” than healthier products. With regard to changes in weekly purchases in the cafeteria after 6 months, 50% of the boys of the IS maintained or changed to healthier purchase behaviour ( Table 3 ). In boys of the CS, this percentage was 51.5%. Among girls, 53.6% maintained or changed to a healthier purchase behaviour in the IS, compared to 46.5% in the CS.

Weekly food and drink purchases in the cafeteria.

a From each student, the difference between T0 and T1 has been calculated. Equal or bigger change in healthier products compared to less healthy products has been defined as a healthy score.

3.4. Purchases at the Vending Machines

Data on self-reported purchase behaviour at vending machines were available for 1217 students (542 boys, 675 girls) ( Table 4 ). In the IS, the boys and girls, respectively, bought on average 0.79 and 1.48 healthier, and 0.88 and 1.40 less healthy products per week in vending machines after the intervention. Boys and girls in the CS bought on average 1.13 and 0.87 healthier, and 1.40 and 0.83 less healthy products per week in vending machines after the intervention, respectively. After 6 months, in both the IS and CS, half of the boys maintained or changed to a healthier purchase behaviour (both 49.3%). Among girls, approximately half of the girls in the IS (47.3%) and CS (52.0%) maintained or changed to a healthier purchase behaviour after 6 months.

Weekly food and drink purchases at the vending machine.

3.5. Purchase Behaviour Analysed by Mixed Logistic Regression Analyses

The results of the performed mixed logistic regression analyses showed that the odds for a healthier purchase behaviour compared to less healthy purchase behaviour is approximately equal for students in the intervention and control schools ( Table 5 ). In boys, we found odds ratios of 0.92 (95%CI 0.62; 1.36) for cafeteria purchases and 1.02 (95%CI 0.62; 1.67) for vending machine purchases. Girls showed an odds ratio of 1.29 (95%CI 0.85; 1.96) for the cafeteria and 0.84 (95%CI 0.62; 1.14) in vending machines purchases. Adjustment for demographic (model 2), behavioural (model 3) and environmental variables (model 4) did not materially change the results.

Mixed logistic regression analyses on the effect of the intervention (ref. group is control group) on changes in purchase behaviour.

a Dichotomous outcome: healthier vs. less healthy changes in purchases over time. b Model 1 = mixed logistic regression analysis, corrected for school. c Model 2 = Model 1, plus corrected for demographic variables (age, education). d Model 3 = Model 2, plus corrected for behavioural determinants (attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioural control, intention); e Model 4 = Model 3, plus corrected for environmental determinants (amount of money spent in school p/w, breakfast, food purchases outside school, drink purchases outside school, food brought from home, drinks brought from home).

The analyses to the effect of a healthier canteen (healthier versus less healthy (ref. group) availability in the cafeteria, vending machine or accessibility) on purchase behaviour showed OR‘s ranging from 0.87 (95%CI 0.61–1.26) for combined purchases in girls, to 1.27 (95%CI 0.75–2.17) for purchases in vending machines in boys ( Table 6 ). Adjustment for demographic (model 2), behavioural (model 3) and environmental variables (model 4) again did not materially change the results.

Mixed logistic regression analyses on the effect of a healthier canteen (ref. group not healthy) on changes in purchase behaviour.

a Dichotomous outcome: healthier vs. less healthy changes in purchases over time. b Healthier canteen, measured with the subtopic healthier products available in cafeteria (≥60%, <60% (ref. group)). c Healthier canteen, measured with the subtopic healthier products available at vending machines (≥60%, <60% (ref. group)). d Healthier canteen, measured with the subtopic fulfilled healthier accessibility criteria (≥60%, <60% (ref. group)). e Model 1 = mixed logistic regression analysis, corrected for school. f Model 2 = Model 1, plus corrected for demographic variables (age, education). g Model 3 = Model 2, plus corrected for behavioural determinants (attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioural control, intention); h Model 4 = Model 3, plus corrected for environmental determinants (amount of money spent in school p/w, breakfast, food purchases outside school, drink purchases outside school, food brought from home, drinks brought from home).

4. Discussion

We investigated the effect of support in implementing the “Guidelines for Healthier Canteens” on changes in the school canteen (cafeteria and vending machine) and on food and drink purchases of students. Our results show that the support has led to actual changes in the availability and accessibility of healthier products in the canteen. We did not observe changes in students’ purchase behaviour. The large majority of the students (90%) reported that they usually bring food or drinks from home. Most (approximately 80%) students reported buying food or drinks in school only once a week or less.

Schools that received support showed a larger increase in the availability of healthier products in the cafeteria compared to control schools. The intervention schools also complied with more criteria for the accessibility of healthier products than the control schools. These results are in line with previous studies which also showed that implementation support is likely to increase the use of guidelines, especially if it consists of multiple components and is both practice and theory-based [ 24 , 37 ]. The support we offered was targeted at different stakeholder-identified impeding factors related to implementation of the guidelines, such as knowledge and motivation. The process evaluation already showed that our implementation plan favourably influenced these factors [ 38 ].

With regard to vending machines, changes were smaller and present in fewer schools compared to changes in the cafeteria. This result may be explained by the fact that schools do not always own nor regulate the content of the vending machines themselves, but outsource them to external parties such as caterers or vending machine companies. Some schools were therefore unable to change the offering and position of products in the machine within the study period. Previous research showed that vending machines were healthier if appointments about the healthy offer were included in agreements with caterers or vending machine companies [ 39 ]. Making agreements about the availability and accessibility of healthy products in the machines is therefore recommended.

In contrast to the changes in the canteen, we did not observe relevant differences in change of healthier purchases between students in intervention and control schools, nor between students from schools with a healthier canteen compared to students from schools with a less healthy canteen. An explanation for these results might be that the duration of the intervention was between four to six months, which proved to be short for the schools to make changes, as we noticed that in most canteens changes were made just before the post-measurements. As a result, students did not have enough time to get used to the new situation and to adapt their purchases. The effects of a healthier canteen on students’ purchases remain therefore unknown. Our results are in contrast with many other studies that show that increasing the offering of healthier products and changes in placement and promotion in favour of healthier products are likely to lead to healthier food choices among customers [ 4 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 ]. However, reviews identified that investigations yielded contradictory results [ 44 ], and they emphasize the low quality of the studies [ 43 ], making more research needed.

Changing dietary behaviour is complex and affected by multiple individual, social and environmental factors [ 45 , 46 , 47 ]—for example, the palatability, price and convenience of foods offered in environments that youth visit regularly, including the school canteen and shops around schools [ 13 , 45 , 48 ]. During adolescence, many factors that influence youth’s dietary choices are changing: they become more independent, parental influence decreases and influence of peers increases, living environments expand, and they have more money to spend [ 49 , 50 ]. These changes provide opportunities to develop healthy dietary habits which are likely to sustain over time [ 51 ]. Even though our study did not show a relation between a healthier canteen and healthier purchase behaviour, we would recommend that healthier food choices should be facilitated in school canteens, including vending machines, a place that students visit regularly and where students can autonomously choose what they buy. This might influence student purchase behaviour directly at the school canteen or in shops around schools, and foresees in educating adolescents on healthy norms [ 52 ]. This enables all youth to experience that healthy eating is important, tasty and very common, which they can use throughout their life.

A strength of our study is that the support consisted of multiple implementation tools which stakeholders could decide to use, as well as when and how. Moreover, our study included tailored advice. Previous research has shown that both a combination of components and tailored advice could increase the likelihood of an effective implementation plan [ 37 , 53 ]. Other strengths of our study are the measurement of outcomes both on the canteen and student level and the separate analyses for boys and girls. In general, boys are more likely to make impulsive, intuitive changes [ 41 ]. In contrast, girls are more likely to overthink their choices, limiting the effect of an attractive food offering. In our study, subtle differences across gender were observed, with boys indicating buying food and drinks outside the school more often. However, this finding should be further explored in future studies.

There are also some study limitations that should be mentioned. First, the use of self-reported questionnaires to investigate purchase behaviour. These measurements are potentially subject to reporting bias and socially desirable answers, likely leading to smaller number of reported purchases overall and larger number of reported healthier products. Possibilities to measure the dietary behaviour of student more objectively and regularly include, for example, the use of meal observations, sales data or Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) [ 54 , 55 ]. We could not use these options due to feasibility constraints, e.g., making use of sales data was not possible as due to different registration systems. Another limitation is the study duration, which was four to six months. A study duration of at least one school year will align to the schools’ daily practice and will give schools the opportunity to create a team of involved people, to embed actions and to make changes.

The fact that the intervention was individualized to the contextual factors and needs of each school is both a strength and limitation. Alignment of the advices to a school’s situation might lead to a more useful support but can also make it more difficult to compare results between different intervention schools. Therefore, it is important to (1) describe the core intervention functions of each tool of the implementation plan to be able to support schools with the same support and (2) to measure if the tools has been delivered and used as planned [ 12 , 56 , 57 ]. In our case, the core elements of the intervention have been described in the study design [ 34 ]. In addition to the effect evaluation, we also evaluated the quality of implementation to assess whether schools received each implementation tool [ 38 ].

A final limitation includes the fact that, due to the skewness of our purchase data and the non-linearity of some of the relations under study, we decided to dichotomize our data. This negatively influenced the power, and led to some loss of information.

Based on our results, we recommend that future studies investigate the sustainability of supportive implementation of food environment policy. In addition, we recommend longer-term studies that assess changes in students’ purchases inside, and in shops around, school, that appear after an adaptation period.

Our results confirm that adolescents in the Netherlands bring most food and drinks from home and additionally buy their food inside as well as outside school. Attention to the home environment and the environment around school is therefore needed. The complexity of the food environment at schools within this broader food environment makes the use of whole system-based approaches important [ 13 , 46 ]. Different relevant stakeholders such as parents, shopkeepers, and local policy makers should be actively involved in this approach. Moreover, a healthy school environment not only consists of a healthy canteen, including vending machines, but also includes food education, integration with other health promotion school policies [ 58 ]. This is important, as schools contribute to the personal development of youth, wherein learning about making choices with regard to a healthy lifestyle in an obesogenic environment is an essential part.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the changes in Dutch school canteens and self-reported student purchase behaviour after support to implement the Guidelines for Healthier Canteens compared to no support. We conclude that such support appears to contribute to healthier canteens. Our results did not show an effect of the implementation on healthier students’ purchase behaviour, perhaps due to the short time between the changes made in the canteen and our follow-up measurements. Due to the fact that this study was performed in collaboration with the Netherlands Nutrition Centre and involved stakeholders, our research results are likely to lead to implementation in daily practice. More system-based approaches are warranted to be able to influence students’ dietary behaviour. Additionally, long-term research to investigate the effects of healthier school canteens are needed.

Acknowledgments

We thank all schools, coordinators, school canteen advisors, students and other involved stakeholders who participated in this study. We also thank Renate van Zoonen and our Health Sciences students (Tamara Coppenhagen, Samantha Holt, Katelyn Sadee and Andrea Thoonsen) who supported us in the gathering of data.

Author Contributions

C.M.R., E.L.V. and J.C.S. designed the research. I.J.E. conducted the research, supported by S.M.J. and L.V. I.J.E. performed the data analysis, supported by M.R.d.B. I.J.E. drafted the manuscript, and all other authors helped refine the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

This research was funded by the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development [ZonMw, Grant Number 50-53100-98-043].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

SCHOOL CANTEEN AND STUDENT'S SATISFACTION

Related Papers

Mel's channel

Psychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary Journal

Psychology and Education , Rosa Madonna L. Licudan , Dennis Caballes

This study aimed to determine the students' satisfaction on the school canteen operation of Pililla National High School during School Year 2022-2023. The researcher used stratified technique-a probability sampling procedure in which each member of the population has an equal chance of being selected, providing a representative sample that accurately reflects the characteristics of the population being studied. The respondents of the study were 279 Junior High School students and were chosen using stratified sampling technique. This study utilized the mix method of research in which the researcher combines the elements of qualitative and quantitative approaches. The study used the researchers made questionnaire, which includes the data about profile such gender and socioeconomic status as Part I, the level of satisfaction of junior high school students on school canteen operation in Part II and the typical experiences that influence the level of satisfaction of students in the school canteen operations in Part III. The researcher utilized different data gathering techniques such as questionnaire checklist (hard copy and online) and survey form in order to the conduct of this capstone project and will employ different analytical tools to help and justify the conduct of the study. It was discovered that female respondents' outnumbered male and majority of the students belong to socioeconomic status of less than 10, 000, while on the level of satisfaction on school canteen operations, it was found out that cleanliness of the school canteen obtained the highest computed mean and has been identified with the most consistent response among the respondents as revealed by the standard deviation., however, it was also revealed that there is no significant difference in the students' satisfaction on school canteen operations when assessed by the respondents categorized in terms of gender except for the area on nutritional value (p<0.05), and there is no significant difference in the students' satisfaction on school canteen operations based on socioeconomic status reflective of the sig. values all greater than α = 0.05. On the qualitative data, the researchers found out that the experiences that influence student satisfaction in school canteen operations can be complex and multifaceted, and may vary depending on factors such as student demographics, cultural backgrounds, and personal preferences. It is important for canteen operators to take these factors into account when designing and implementing strategies to improve student satisfaction and promote healthy eating habits.

Abstract Proceedings International Scholars Conference

Ruchel G Oasan

Millions of people in the world are suffering from scarcity of food, yet tons of food are wasted every day. This study was conducted to determine the food wastage of high school students and the service quality of a cafeteria located in Silang, Cavite. Convenience sampling was utilized to select high school students enrolled in the school where the cafeteria is situated to participate in the study. A descriptive-evaluative research design was used and data gathered were analyzed using descriptive statistics such as frequency, mean, and standard deviation. Quarter waste method was used to measure plate wastage while adopted questionnaire was used to determine the service quality of the cafeteria. Findings revealed that the highest percentage of food wastage was gluten followed by ground vegescallop, vegemeat, tofu, and beans. In terms of service quality, the lowest percentage was the dining area (Mean= 2.95 and SD= 0.80), followed by Food Quality (Mean=3.44 and SD= 0.80), Food Varie...

Zenodo (CERN European Organization for Nuclear Research)

Guy Nouatin

berry stark

erlinda hapsari

Healthy canteens must provide food and drinks that are guaranteed safety, nutrition and have safe, clean and healthy facilities for all school residents. The purpose of this study was to analyze the factors that influence the condition of the canteen in Elementary Schools of Semarang City. Type of analytic observational research. This study used a cross sectional design. Retrieval of data was using questionnaire instruments and observation sheets. Data analysis used chi square and logistic regression. The results of data analysis there was an influence between the level of knowledge of the canteen condition (pv = 0.006), there was an influence between the level of education on the canteen condition (pv = 0.005), there was no effect between training on the canteen condition (pv = 0.972), there was an influence between the availability of media the mass of the canteen condition (pv = 0.018), there was no influence between the accreditation status of the canteen condition (pv = 0.72). ...

Indonesian Journal of Multidisciplinary Science

146_Cindy Silvia Agustin

Children's health must be supported and maintained in the family environment and school environment. Making a healthy canteen there must be planning in advance, with careful planning will facilitate activity. Organizing is planned to determine whose duties and authorities will carry out a particular task to achieve a common goal. The implementation of this healthy canteen must go well, this healthy canteen will provide good benefits not only to its students but to the people who are in the canteen environment. This healthy canteen must also be supervised by relevant parties such as local health centers. With a healthy canteen, student food can be echoed and then the student's health is maintained and will result in increased student learning achievement.

Riset Informasi Kesehatan

Rani Rizqi Dwi Larasati

Background: In 2014 the POM Agency reported cases of food poisoning in various parts of Indonesia. One of these cases was caused by 15 cases of street food with 468 victims, and 1 case of poisoning due to catering services totaling 748 people. So, therefore destination study is for knowing the perception of handler food to the establishment of a healthy canteen at the University Jambi. Method: The research was conducted qualitatively using approach observation and Interview deep. The research subjects were 15 people consisting of 8 informants Main is a food handler and 7 person informant supporters, namely 3 Business Management Agency and 4 students. Result: The perception of food handlers on the establishment of a healthy canteen at Jambi University is quite good. The perception of vulnerability to the establishment of canteens at Jambi University is still not good. Likewise, the perception of barriers to the establishment of a healthy canteen at the University of Jambi is also sti...

NOORAZLIN RAMLI

Abstract: Students are sandwiched between the intensity of time to be devoted to their studies and to pursue their nutritional requirements. Hence, they are pressured to patronize the university’s food service as an alternative source to for food and beverages. This study empirically examines students ’ acceptance level and satisfaction on the service delivery attributes at Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM) hostel cafeterias. Through self-reported experiences on three dimensions of service delivery attributes, students who reside in UiTM Shah Alam hostels, namely Kolej Seroja, Kolej Anggerik and Kolej Perindu went through a questionnaire survey. Results revealed that food and beverages and service attributes are the major determinants looked at by students when dining at UiTM hostel cafeterias and they had the same expectations as other restaurant customers. They expect decent food and beverages with an acceptable degree of service. Nevertheless, their expectations were not met. In c...

International Journal of Advanced Research in Management and Social Sciences

Grace Delelis

The study was conducted to determine the Status of the University Cafeteria Services at Cagayan State University, Andrews Campus, Tuguegarao City. The respondents are the one hundred fifty students from Andrews Campus. The descriptive method of research was used in the study. To substantiate the responses of the respondents, personal interview was also done. Results of the study revealed that the mean age of the respondents is 19. Majority of the respondents are female and single. The average weekly allowance of the respondents amounted to P575. As to the services availed by the respondents, forty one percent availed of meals and twenty seven percent availed both snacks and meals. Forty of the respondents prefer burger and juice in the morning as snacks while thirty eight of the respondents prefer siomai and juice as snacks in the afternoon. For breakfast offered at the Cafeteria, many of the respondents chose rice, tocino and hotdog and few of the respondents take bread and coffee ...

RELATED PAPERS

Joan Uribe , Joan Vilarrodona

Mariana Gonçalves da Costa

Neurogastroenterology & Motility

Frances Connor

Brazilian Journal of Production Engineering

Moisés de Andrade Abreu

Bandung Conference Series: Mining Engineering

Iswandaru Iswandaru

서귀포출장샵주소<ymsm999.com>서귀포콜걸샵/서귀포출장마사지/서귀포출장안마/서귀포모텔추천/서귀포일본인출장샵/서귀포여대생출장샵/서귀포외국인출장샵/서귀포후불출장샵/서귀포출장서비스/서귀포출장샵후기/서귀포출장안마후기/서귀포키스방/서귀포키스방후기

Health Services Research

Gregory Wozniak

Journal of Polymer Science Part B: Polymer Physics

Marta Mary de Jesus

Nano letters

Marielena Castro

Isabelle Lachance

一模一样加拿大范莎学院毕业证 uofs文凭证书英文录取通知原版一模一样

The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism

Sheldon Shi

European urology open science

Laetitia de Kort

International Review of Management and Marketing

Rabiah Adawiah Ali

Turkish Journal of Anesthesia and Reanimation

Syaiful Anwar

Metallurgical and Materials Transactions B-process Metallurgy and Materials Processing Science

Kamal T. Kilby

sylvie craipeau

Guillermo Arosemena

In: JORNADA DE INICIAÇÃO CIENTÍFICA, 6.; SEMINÁRIO INTEGRADO DE PESQUISA E EXTENSÃO DA UnC, 2., 2012, Concórdia. Anais... Concórdia: Embrapa Suínos e Aves, 2012. p. 165. JINC. SIPEX.

Everton Luis Krabbe

International Journal of Laboratory Hematology

Marcos Roberto Viana

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Factors that influence food choices in secondary school canteens: a qualitative study of pupil and staff perspectives.

- 1 Nutrition Innovation Centre for Food and Health, School of Biomedical Sciences, Ulster University, Coleraine, United Kingdom

- 2 Education Authority, Armagh, United Kingdom

Background: Adolescence is recognised as a period of nutritional vulnerability, with evidence indicating that United Kingdom adolescents have suboptimal dietary intakes with many failing to meet dietary recommendations. Additionally, adolescence is a time of transition when they become more independent in their dietary choices and begin to develop their own sense of autonomy and are less reliant on their parent’s guidance, which is reported to lead to less favourable dietary behaviours. Reducing the prevalence of poor dietary intakes and the associated negative health consequences among this population is a public health priority and schools represent an important setting to promote positive dietary behaviours. The aim of this school-based study was to explore the factors and barriers which influence food choices within the school canteen and to identify feasible strategies to promote positive dietary behaviours within this setting.

Methods: Thirteen focus groups with 86 pupils in Year 8 ( n = 37; aged 11–12 years) and Year 9 ( n = 49; aged 12–13 years) in six secondary schools across Northern Ireland, United Kingdom were conducted. Additionally, one-to-one virtual interviews were conducted with 29 school staff [principals/vice-principals ( n = 4); teachers ( n = 17); and caterers ( n = 7)] across 17 secondary schools and an Education Authority (EA) senior staff member ( n = 1). Focus groups and interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and analysed following an inductive thematic approach.

Results: Using the ecological framework, multiple factors were identified which influenced pupils’ selection of food in the school canteen at the individual (e.g., time/convenience), social (e.g., peer influence), physical (e.g., food/beverage placement), and macro environment (e.g., food provision) level. Suggestions for improvement of food choices were also identified at each ecological level: individual (e.g., rewards), social (e.g., pupil-led initiatives), physical (e.g., labelling), and macro environment (e.g., whole-school approaches).

Conclusion: Low-cost and non-labour intensive practical strategies could be employed, including menu and labelling strategies, placement of foods, reviewing pricing policies and whole-school initiatives in developing future dietary interventions to positively enhance adolescents’ food choices in secondary schools.

Introduction

Globally, adolescent overweight and obesity has increased significantly ( 1 ) and is now recognised as one of the most urgent public health challenges ( 2 ). This issue is particularly prevalent within the United Kingdom, with >30% of adolescents (aged 11–15 years) impacted by overweight or obesity ( 3 ). The negative physical ( 4 , 5 ) and psychological ( 4 – 6 ) health implications associated with adolescent obesity are well-documented. Additionally, challenges also exist with reversing adolescent obesity, with 80% of obese adolescents likely to remain obese in adulthood ( 7 ), increasing the risk of further poor health outcomes in later life ( 8 ). Thus, determining effective preventative measures to mitigate the risk of obesity among this population is crucial to improve current and future health and minimise long-term obesity-related medical costs ( 9 ).

Less healthful dietary behaviours during adolescence, such as the overconsumption of energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods, can increase short ( 10 ) and long-term ( 11 ) obesity risk. United Kingdom adolescents’ dietary habits are of concern, with The National Diet and Nutrition Survey indicating suboptimal dietary behaviours among this population, including inadequate consumption of fruit and vegetables ( 12 ), low fibre intakes ( 13 ), excessive fat and sugar intakes ( 13 ) and higher energy intake also among those with overweight or obesity ( 14 ). As children transition to adolescents, they can become more susceptible to consuming an unbalanced diet ( 15 ) and dietary behaviours acquired during this period can persist into adult life ( 16 ). Therefore, dietary intervention during adolescence is essential to offset trends of declining dietary quality and establish healthy eating behaviours that can be sustained across the lifespan.

Adolescents are required to spend 190 days each year in school ( 17 ). Given the continuous contact time schools provide to this population, this setting represents a promising environment to deliver dietary interventions ( 18 ). School-based interventions are cost-effective ( 19 ) and offer the opportunity to reach the majority of adolescents, irrespective of socio-economic status or ethnical background ( 20 ). Moreover, adolescents’ consume a substantial proportion of their daily energy intakes in school (up to 1–2 meals per day) ( 21 , 22 ). However, despite consistent efforts to determine the most effective school-based interventions to improve adolescents’ dietary intakes, outcomes remain short-term ( 23 ).

In Northern Ireland (NI), records suggest that more than half of adolescents (54–63%) typically consume school meals (provided by schools) at lunchtime ( 24 ) as opposed to a packed lunch (brought from home) or sourcing items from nearby food outlets. Mandatory food-based standards ( 25 ) are in place in NI schools to ensure pupils have access to a healthy and balanced school meal ( 26 ), which is of particular benefit to those who may have limited access to nutritious food outside school. However, although secondary schools provide healthier options compliant with the school-food standards, many adolescents continue to purchase the less nutritious items from the menu on offer ( 27 ), highlighting the need to explore alternate influential factors on adolescents’ lunchtime food choices. In addition to improved food provision, nutritional education is also compulsory in NI secondary schools (post-primary) for adolescents in Key Stage 3 (aged 11–14 years) ( 28 ), albeit, adolescents’ nutritional knowledge often has minimal impact on their food choices ( 29 ). Thus, identifying additional opportunities within the school-setting to promote positive dietary change is of importance. As pupils progress from primary to secondary education, parental control over their eating behaviours lessens and their propensity towards their dietary decisions become more independent-based ( 15 ). It is therefore pertinent to gain insight into the principal factors influencing adolescents’ school-based food choices as they develop increasing nutritional autonomy during this transitional period to optimise engagement and success of future school-based dietary interventions.

Research suggests that adolescents’ food choices within the school canteen can be influenced by various food-related factors, including available items, quality, appearance, taste, cost, value for money and peer pressure to opt for specific foods and canteen-related factors such as food hygiene, school menu and price displays, queue length and seating availability ( 30 ). More recent work has revealed adolescents’ favour take away items in the school canteen and associate ‘main meals’ as food to be consumed within the home environment ( 31 ).

In order to better understand the multiple levels of influence on adolescents’ food choices, Story et al. ( 32 ) proposed an ecological framework to consider their eating behaviours under four broad levels of influence to include individual (intrapersonal), social environmental (interpersonal), physical environmental, and macro level to aid in the design of appropriate nutrition interventions targeted at this population.

The difficulties associated with changing health behaviours are well recognised ( 33 ). When designing interventions, early involvement of stakeholders and the target user is recommended ( 34 ). In addition, although often under-utilised, qualitative research methodologies may assist in informing and optimising the design of interventions ( 35 ). Gaining further understanding of NI adolescents’ perspectives on the factors influencing their food choices within school and their suggestions on how best to address these factors through school-based strategies is needed if effective interventions to enhance positive dietary behaviours in this population are to be achieved. Additionally, a paucity of information exists on United Kingdom school staff’s perspectives on adolescents’ school-based food choices and their recommendations for improvement, limiting the ability for comparisons between key stakeholder groups to be examined. Furthermore, to aid in successful intervention design, consulting with school staff may provide researchers with a better understanding of any existing implementation practicalities to consider, such as schools’ academic priorities, available resources and the need to avoid over-burdening staff ( 36 ).

The aim of this study was to explore the primary factors influencing adolescents’ food choices within the school canteen environment from the pupil and school staff perspective. Additionally, a secondary aim was to identify feasible strategies to encourage healthful food choices amongst adolescents within the school-setting.

Study design

Qualitative research methods were selected to provide insight into the complexity of individuals’ food-related behaviours ( 37 ), in addition to their interactive nature to facilitate in-depth exploration of topics raised that is less possible with quantitative surveys ( 38 , 39 ). Focus groups with pupils and one-to-one interviews with school staff were conducted to capture participants’ perspectives, attitudes, and experiences ( 40 , 41 ). The reporting of this study is aligned with the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ; Supplementary Table S1 ) ( 42 ). This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by Ulster University’s Research Ethics Committee (FCBMS-20-016-A; REC/20/0031). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and their parents/ guardians.

Sample selection and recruitment

School pupils.

Year 8 (aged 11–12 years) and Year 9 (aged 12–13 years) pupils in seven purposively sampled ( 43 ) mixed-gender secondary schools in NI were invited to take part in this study. Year 8 (aged 11–12 years) and year 9 (aged 12–13 years) pupils were the focus as they had recently transitioned to secondary school and had become exposed to making independent food choices in the school canteen. Pupils who purchased food in the school canteen regularly (at least once each week) were eligible to participate. Schools were contacted via email or telephone and following agreement from the school principal, information sheets, assent and consent forms were distributed by a senior teacher to eligible pupils and asked to discuss with their parents/guardians. Participants who returned completed assent and consent forms were selected by a senior teacher to participate in the focus group.

School staff

A purposive sample ( 43 ) of school staff from a range of socio-economic (assessed using number of free school meals) and geographically diverse mixed-gender secondary schools ( n = 17) across NI were invited to participate in this study. All grades of staff were eligible to participate including principals/vice principals and teaching staff from a range of subject disciplines. School catering staff included supervisors and caterers. Additionally, as the EA has responsibility for school meal provision in a large proportion of NI secondary schools, one senior EA staff member was invited to participate. School staff were contacted via email or telephone, and following agreement, information sheets and consent forms were distributed.

Data collection

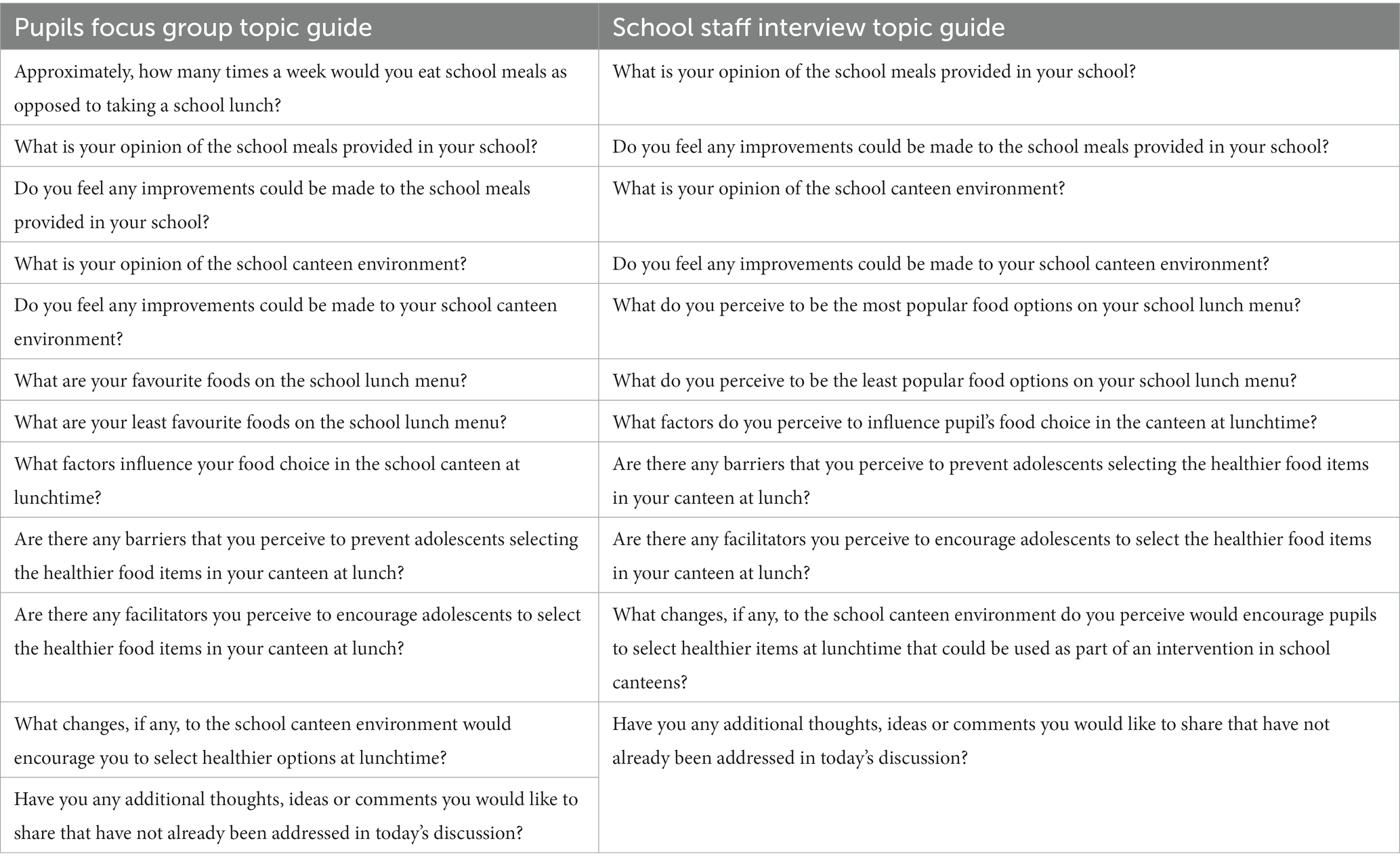

Pupils participated in mixed-gender focus groups and staff in one-to-one interviews, which were conducted independently by a researcher trained in qualitative research (L.D.D, PhD researcher, not affiliated with schools). Similar semi-structured discussion guides were used for the focus groups and interviews ( Table 1 ) to ensure consistency and facilitate comparability between the pupils’ and staff’s perspectives. All focus groups and interview discussions were facilitated by the researcher using the topic guide to explore key issues. To enhance interaction and active listening during the discussions, notes were made directly after each session to enrich the data collected ( 40 ). Focus groups and interviews were undertaken until data saturation had been reached ( 44 ).

Table 1 . Semi-structured discussion guide for pupils focus groups and school staff interviews.

Mixed-gender focus groups of 5–8 pupils were conducted between May and June 2021 within the school (classroom or hall) and during school hours under observation from a senior teacher. All pupils were reminded prior to commencing the focus groups that the information they provided would remain anonymous and would not be shared with their parents or school staff. The topic guide ( Table 1 ) was designed and developed based on a review of the area and pilot tested on a small group of Year 8 pupils in different schools to test the questions for level of comprehension to optimise clarity of questions ( 45 ). Focus group sessions were on average 30 min duration (range 12–43 min).

One-to-one interviews were conducted remotely with school staff via Microsoft Teams or by telephone call at a suitable time for each participant between October and December 2020. Interview questions were pilot tested with one teacher in a different school to test suitability of questions. Interviews took on average 30 min (range 9–57 min).

Data analysis

Focus groups and interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were uploaded to NVivo 12 Pro Software (QSR International) for data management and analysed following the six phases of reflexive thematic analysis using an inductive approach ( 46 ). Codes were independently applied to quotes throughout each transcript by a member of the research team (L.D.D). To minimise the risk of bias and ensure correct interpretation of quotes, transcripts and codes were critically reviewed, discussed and confirmed by the research team (A.J.H and A.M.G). Quotes representing similar views were then clustered together and assigned initial sub-themes (L.D.D), which were reviewed by the research team (A.J.H and A.M.G) and refined before reaching consensus on the potential sub-themes. Each sub-theme was then mapped to each level of the ecological model, namely: individual (intrapersonal), social environment (interpersonal), physical environment, and macro environment ( 32 ). Quotes that were most reflective of the sub-themes were selected for inclusion.

Participant and school characteristics

Of the seven purposively sampled schools, six schools expressed an interest in participating and one did not respond to the study invitation. 86 pupils participated in 13 focus groups across the six schools ( n = 4 urban; n = 2 rural) throughout three different district council areas in NI, with six focus groups undertaken with Year 8 pupils ( n = 24 female; n = 13 males) and seven with Year 9 pupils ( n = 28 female; n = 21 males). All six schools were co-educational and mixed-gender. Free school meal entitlement across the schools ranged from 21 to 53%.

Of the 35 participants who received initial invitations, 29 participated in this study (four did not respond to the study invitation; one did not return the consent form; one was excluded as they did not have recent experience in a secondary school). The final sample of 29 (24 females, 5 males) comprised principals ( n = 2), vice-principals ( n = 2), teachers ( n = 17), catering staff ( n = 7) sampled across 17 secondary schools, and a senior staff member ( n = 1) in the EA. The schools were in urban ( n = 14) and rural ( n = 3) environments located within eight of 11 district council areas in NI. 16 schools were co-educational (mixed-gender) with one school being female only. Free school meal entitlement in these schools ranged from 7 to 54%.

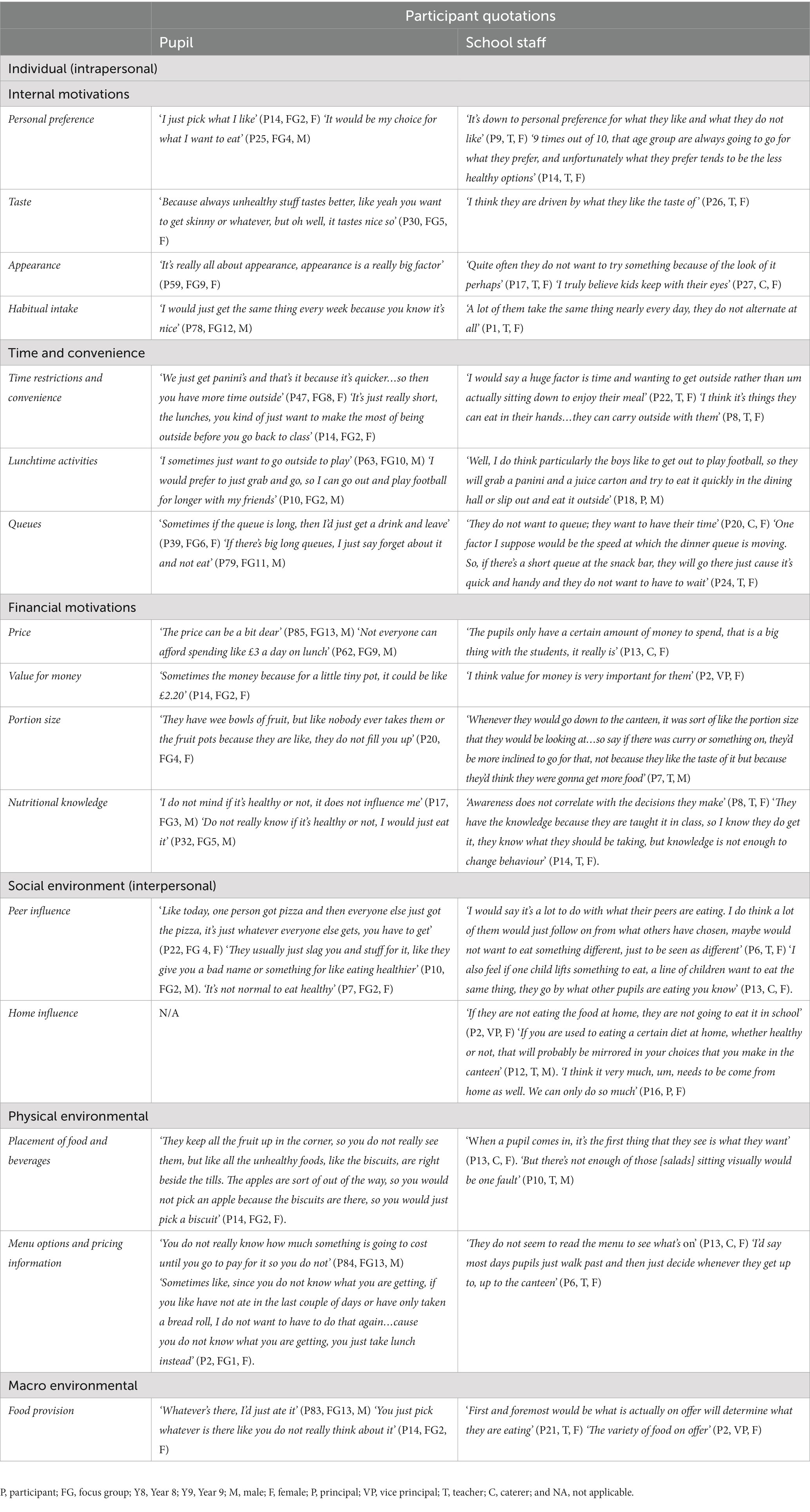

The key sub-themes identified from the pupils’ and staff’s responses and exemplar quotes are reported in Tables 2 , 3 using under the four levels of the ecological framework: individual (intrapersonal), social environment (interpersonal), physical environment, and macro environment ( 32 ).

Table 2 . Pupils’ and school staff’s perceptions on the influences of adolescents’ dietary choices in the school canteen.

Table 3 . Pupils’ and school staff’s views on strategies to encourage selecting healthier options in the school canteen.

Influences on pupils’ food choices in the school canteen

Individual (intrapersonal).

Exemplar quotes to illustrate the following sub-themes are shown in Table 2 .

Internal motivations

Pupils’ personal preferences, in addition to taste, appearance and habitual intakes, were important factors that influence their food choices in the school canteen. These factors often took precedence over the healthiness of the food items on offer, with many pupils commenting that options which were perceived to be less healthy were more tasteful. Pupils’ also commented that if they did not like the choices available, they may have not have lunch in the canteen that day.

‘I just pick what I like’ (P14, FG2, F)

School staff had similar perceptions regarding personal preferences and reinforced that pupils were more likely to select items which were less healthy. School staff also reported that the appearance, familiarity and taste of the food were important when selecting items in the canteen and that these factors may act as barriers to pupils choosing alternate food options.

Time and convenience

Many pupils identified time restrictions as being a major barrier when making food choices as they have limited time for lunch break and many preferred convenient, ‘grab-and-go’ options as they preferred to maximise their free time with peers and participate in lunchtime activities. Additionally, the length of queue in the canteen was also commonly cited, with pupils’ opting for meals which had shorter queues, which may influence choice and possibly discourage pupils from eating in the canteen or skipping their lunchtime meal.

‘If there’s big long queues, I just say forget it and not eat’ (P79, FG11, M)

This was similar to school staff’s views, who suggested that the queues were a factor which influenced food choices in the canteen and this issue was identified to be of greater importance for male pupils who prioritised socialising outside at lunchtime and were less likely to be waiting in queues. School staff also described how in more recent years, pupils’ choices have gradually changed over the years from selecting more traditional sit-down meals in the canteen to more convenient, portable and on-the-go options.

Financial motivations

Both pupils and staff commonly reported that price, value for money and portion size influenced food choice. For example, fruit options were reported to be of a small portion size and lower satiety value, thus, not good value for money, and therefore limited the selection of these items. Additionally, pupils reported that food items were expensive, with one pupil noting that on occasions, money allocated from ‘free school meal entitlement’ was insufficient to cover the cost of lunch. Financial motivations were identified as a key theme reported by five out of six schools regardless of whether the school was located in an area deemed to be rural or urban.

‘Not everyone can afford spending like £3 a day on lunch’ (P62, FG9, M)

School staff also commented that they believed that pupils had a budget to purchase lunch and that the cost of food items and value for money was an important factor in their choice of food. It was noted by staff that dissatisfaction with food choice for value for money was perceived to increase the number of pupils opting for a packed lunch. School staff also commented that male pupils prioritise purchasing food which seemed to have larger portion sizes.

Nutritional knowledge

Pupils’ reported different views on the importance of understanding the nutritional value and composition of foods and whether the food was a healthy choice. Some pupils stated that they were unaware of which foods and meals were healthier, whereas, others were very aware of the healthier options. Both groups stated that this would not be a primary factor to influence their food choices.

‘I do not mind if its healthy or not, it does not influence me’ (P17, FG3, M)

School staff agreed that they did not believe that nutritional knowledge was a key factor in influencing food choices of most pupils and reported that other factors, such as taste preferences, familiarity and convenience were more of a priority whilst in school. Nutrition education forms part of the curriculum for all secondary (post-primary) school pupils in NI for Year 8–10 (aged 11–14 years), however, staff reported that this knowledge was not considered to be sufficient to change their behaviour and translate into more positive health behaviours in the canteen.

Social environmental (interpersonal)

Peer influence.

Peers were consistently identified as a major influence on pupils’ food choices. Pupils reported feeling pressurised to select similar items in the canteen to those of their peer group to avoid negative comments. Both male and female pupils expressed concerns about how their peers viewed them when making their individual food choices and that selecting certain food items in the canteen may not be considered socially acceptable.

‘Like today, one person got pizza and then everyone else just got the pizza, it’s just what everyone else gets, you have to get’ (P22, FG4, F)

Peer influence was also the most dominant, reoccurring sub-theme within this level (social environmental) among school staff. School staff shared the view that pupils’ want to emulate their peers and aim to conform to what is perceived to be acceptable eating behaviours in an attempt to avoid standing out and to preserve a positive social status. In addition, catering staff reported viewing peer-induced choices in the canteen, with pupils selecting similar items to their friends.

Home influence

No pupils made reference to the influence of eating habits at home impacting on food choice in the school canteen. However, school staff expressed that eating habits established at home are reflective of pupils’ food behaviours in school and that both schools and parents need to promote positive eating behaviours to pupils simultaneously for the message to be impactful, as schools alone were considered to be insufficient to achieve sustainable positive dietary change.

Physical environmental

Placement of food and beverages.

The location and ease of access to food and beverage items in the canteen was noted as being influential on food choice. Pupils’ acknowledged that healthier options were usually in a less prominent position in the canteen and often placed out of sight, having a direct influence on their purchasing decisions.

‘The apples are sort of out of the way, so you would not pick an apple because the biscuits are there, so you would just pick a biscuit’ (P14, FG2, F)

School staff also recognised the impact of product placement on pupils’ food choice and cited that they are likely to opt for the food items which they observe first in the canteen.

Menu options and pricing information

Pupils indicated that they were often unaware of what foods were available on the menu in the canteen daily. This uncertainty of the menu was reported to impact on purchasing decisions, for example, pupils opting for a packed lunch or skipping their school meal. Pupils also noted dissatisfaction with clarity of pricing information and thus difficulties arose when choosing meals.

‘You do not really know how much something is going to cost until you go to pay for it so you do not [buy it]’ (P84, FG13, M)

The majority of school staff members did not comment on school menus and pricing information in influencing adolescents’ food choice. A few school staff reported that lunchtime menus were displayed in their schools, however, considered them to be ineffective or overlooked by pupils.

Macro environment

Exemplar quotes to illustrate the following sub-theme are provided in Table 2 .

Food provision

Pupils and school staff both cited food availability in the canteen as having a direct influence on the item’s pupils were consuming daily. Pupils also perceived there to be a lack of variety served in the canteen and that the options provided can often be repetitive. According to school staff, the canteen offered a good range of food options.

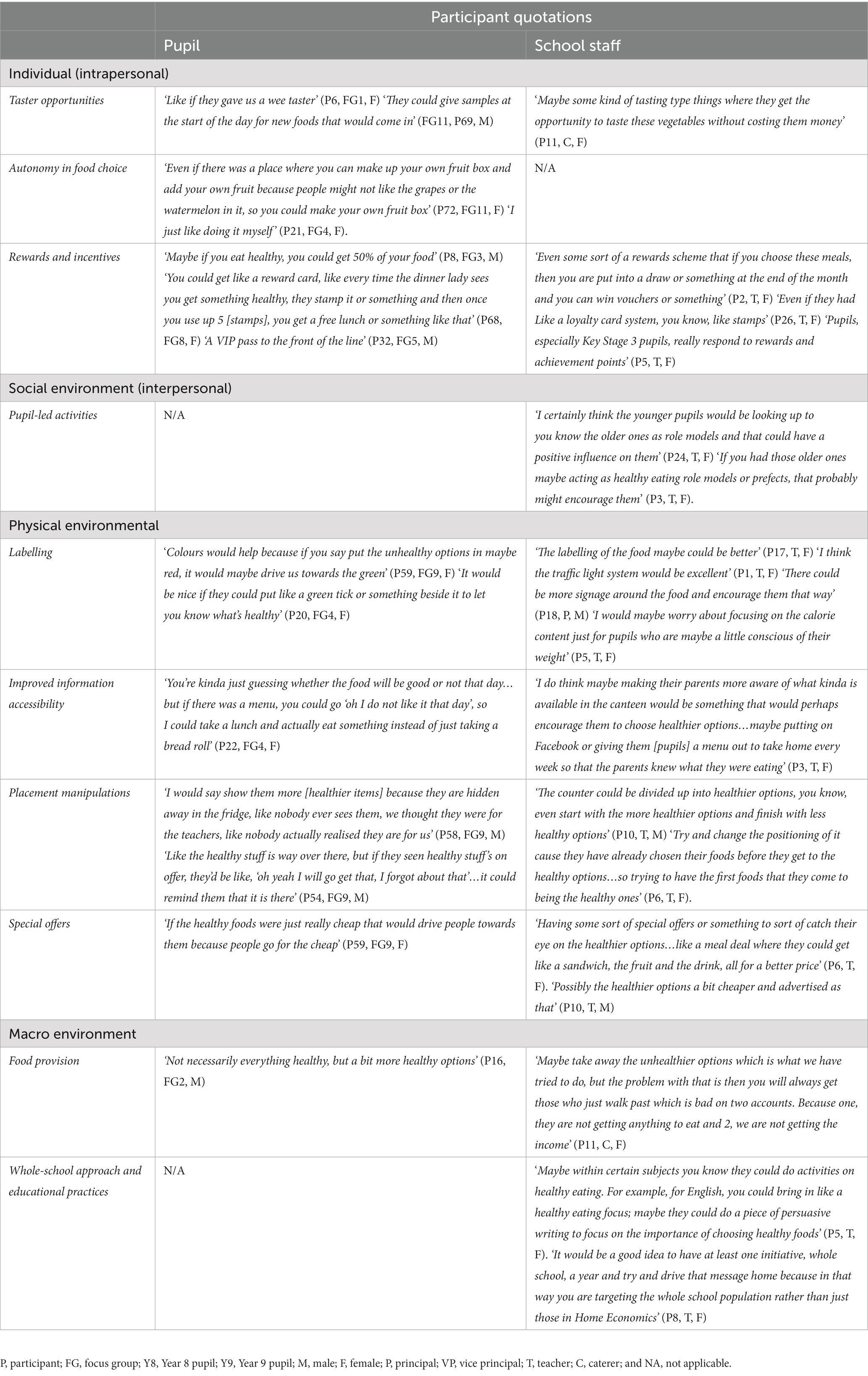

Strategies to encourage selecting healthier options in the school canteen setting

Exemplar quotes to illustrate the following sub-themes are provided in Table 3 .

Taster opportunities

To encourage the selection of healthier items in the school canteen, pupils’ and school staff recommended providing pupils with the option to sample certain food items prior to purchasing them to minimise financial risk.

Autonomy in food choice

Some pupils reported that combined food items in the canteen were off-putting, for example, mixed vegetable dishes and pre-made fruit salads. To counteract this barrier of improved food choices and to facilitate a higher uptake of these items in the canteen, pupils suggested that options be served separately to allow independent, self-selection of these items.

School staff did not directly comment on pupil’s autonomy to promote positive food decisions in the school canteen.

Rewards and incentives

The opportunity to receive rewards as a strategy to engage pupils in healthy eating practises in the canteen was a common, reoccurring sub-theme. Social rewards (e.g., trips, queue skips, extended lunchbreaks, sports activities, non-uniform day, and homework exemption pass), financial rewards (e.g., vouchers, discounted/free canteen items), and recognition rewards (e.g., certificates, awards/credit points) were reported as suitable incentives by pupils to encourage healthier choices in the school canteen. It was clear from the discussions that the concept of tracking their progress could stimulate further interaction with a reward scheme and incorporating in a competitive element at both individual and class group level.

‘A VIP pass to the front of the line’ (P32, FG5, M)

School staff’s views reflected pupils’ in that they also recommended the use of social, financial, and recognition rewards to incentivise pupils to select healthier choices and considered that this would encourage pupils, in particular younger pupils, to be more proactive in their food-based decision making.

Exemplar quotes to illustrate the following sub-theme are provided in Table 3 .

Pupil-led initiatives

Pupils did not make suggestions on how their friends (e.g., pupil-led initiatives) could be a strategy for encouraging the selection of healthier items in the school canteen.

School staff recommended utilising peer networks as an effective means of facilitating positive food choices among adolescents and felt pupils were more likely to resonate with information provided by their peers than those delivered by staff. More specifically, school staff advocated for schools to implement specific roles for senior pupils to act as healthy eating ambassadors within the school to promote healthy eating.

When pupils were asked how best to promote selecting healthier options in the canteen, displaying nutritional labels was highlighted as a means of facilitating their ability to make informed decisions about food choices. Both male and female pupils recommended visual labelling schemes, for example, symbols or icons. Pupils also suggested that schools applying the traffic-light colour-coding system to food items in the canteen and to the school menus would be useful. In addition to nutritional labelling, pupils stated the importance of general food labelling, such as the food item name and ingredients.

‘Colours would help because if you say put the unhealthy options maybe in red, it would maybe drive us towards the green’ (P59, FG9, F)

School staff also proposed labelling of foods and menus as an efficient strategy to facilitate positive food behaviours in the canteen. They suggested colour-coding and visual labelling, but urged the need for caution on calorie/energy labelling, stating concerns of the impact this may have on pupils who may already be weight conscious. School staff suggested that traffic-light labelling in particular would be applicable in the canteen setting and commented that pupils would be familiar with this scheme as it is covered early in the compulsory Home Economics Key Stage 3 (pupils aged 11–14 years) school curriculum. However, it was also noted that labelling schemes may be onerous on the canteen staff and adversely impact on their daily duties and should be considered.

Improved information accessibility