- How it works

Research Problem – Definition, Steps & Tips

Published by Jamie Walker at August 12th, 2021 , Revised On October 3, 2023

Once you have chosen a research topic, the next stage is to explain the research problem: the detailed issue, ambiguity of the research, gap analysis, or gaps in knowledge and findings that you will discuss.

Here, in this article, we explore a research problem in a dissertation or an essay with some research problem examples to help you better understand how and when you should write a research problem.

“A research problem is a specific statement relating to an area of concern and is contingent on the type of research. Some research studies focus on theoretical and practical problems, while some focus on only one.”

The problem statement in the dissertation, essay, research paper, and other academic papers should be clearly stated and intended to expand information, knowledge, and contribution to change.

This article will assist in identifying and elaborating a research problem if you are unsure how to define your research problem. The most notable challenge in the research process is to formulate and identify a research problem. Formulating a problem statement and research questions while finalizing the research proposal or introduction for your dissertation or thesis is necessary.

Why is Research Problem Critical?

An interesting research topic is only the first step. The real challenge of the research process is to develop a well-rounded research problem.

A well-formulated research problem helps understand the research procedure; without it, your research will appear unforeseeable and awkward.

Research is a procedure based on a sequence and a research problem aids in following and completing the research in a sequence. Repetition of existing literature is something that should be avoided in research.

Therefore research problem in a dissertation or an essay needs to be well thought out and presented with a clear purpose. Hence, your research work contributes more value to existing knowledge. You need to be well aware of the problem so you can present logical solutions.

Formulating a research problem is the first step of conducting research, whether you are writing an essay, research paper, dissertation , or research proposal .

Looking for dissertation help?

Researchprospect to the rescue then.

We have expert writers on our team who are skilled at helping students with dissertations across a variety of STEM disciplines. Guaranteeing 100% satisfaction!

Step 1: Identifying Problem Area – What is Research Problem

The most significant step in any research is to look for unexplored areas, topics, and controversies . You aim to find gaps that your work will fill. Here are some research problem examples for you to better understand the concept.

Practical Research Problems

To conduct practical research, you will need practical research problems that are typically identified by analysing reports, previous research studies, and interactions with the experienced personals of pertinent disciplines. You might search for:

- Problems with performance or competence in an organization

- Institutional practices that could be enhanced

- Practitioners of relevant fields and their areas of concern

- Problems confronted by specific groups of people within your area of study

If your research work relates to an internship or a job, then it will be critical for you to identify a research problem that addresses certain issues faced by the firm the job or internship pertains to.

Examples of Practical Research Problems

Decreased voter participation in county A, as compared to the rest of the country.

The high employee turnover rate of department X of company Y influenced efficiency and team performance.

A charity institution, Y, suffers a lack of funding resulting in budget cuts for its programmes.

Theoretical Research Problems

Theoretical research relates to predicting, explaining, and understanding various phenomena. It also expands and challenges existing information and knowledge.

Identification of a research problem in theoretical research is achieved by analysing theories and fresh research literature relating to a broad area of research. This practice helps to find gaps in the research done by others and endorse the argument of your topic.

Here are some questions that you should bear in mind.

- A case or framework that has not been deeply analysed

- An ambiguity between more than one viewpoints

- An unstudied condition or relationships

- A problematic issue that needs to be addressed

Theoretical issues often contain practical implications, but immediate issues are often not resolved by these results. If that is the case, you might want to adopt a different research approach to achieve the desired outcomes.

Examples of Theoretical Research Problems

Long-term Vitamin D deficiency affects cardiac patients are not well researched.

The relationship between races, sex, and income imbalances needs to be studied with reference to the economy of a specific country or region.

The disagreement among historians of Scottish nationalism regarding the contributions of Imperial Britain in the creation of the national identity for Scotland.

Hire an Expert Writer

Proposal and dissertation orders completed by our expert writers are

- Formally drafted in academic style

- Plagiarism free

- 100% Confidential

- Never Resold

- Include unlimited free revisions

- Completed to match exact client requirements

Step 2: Understanding the Research Problem

The researcher further investigates the selected area of research to find knowledge and information relating to the research problem to address the findings in the research.

Background and Rationale

- Population influenced by the problem?

- Is it a persistent problem, or is it recently revealed?

- Research that has already been conducted on this problem?

- Any proposed solution to the problem?

- Recent arguments concerning the problem, what are the gaps in the problem?

How to Write a First Class Dissertation Proposal or Research Proposal

Particularity and Suitability

- What specific place, time, and/or people will be focused on?

- Any aspects of research that you may not be able to deal with?

- What will be the concerns if the problem remains unresolved?

- What are the benefices of the problem resolution (e.g. future researcher or organisation’s management)?

Example of a Specific Research Problem

A non-profit institution X has been examined on their existing support base retention, but the existing research does not incorporate an understanding of how to effectively target new donors. To continue their work, the institution needs more research and find strategies for effective fundraising.

Once the problem is narrowed down, the next stage is to propose a problem statement and hypothesis or research questions.

If you are unsure about what a research problem is and how to define the research problem, then you might want to take advantage of our dissertation proposal writing service. You may also want to take a look at our essay writing service if you need help with identifying a research problem for your essay.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is research problem with example.

A research problem is a specific challenge that requires investigation. Example: “What is the impact of social media on mental health among adolescents?” This problem drives research to analyse the relationship between social media use and mental well-being in young people.

How many types of research problems do we have?

- Descriptive: Describing phenomena as they exist.

- Explanatory: Understanding causes and effects.

- Exploratory: Investigating little-understood phenomena.

- Predictive: Forecasting future outcomes.

- Prescriptive: Recommending actions.

- Normative: Describing what ought to be.

What are the principles of the research problem?

- Relevance: Addresses a significant issue.

- Re searchability: Amenable to empirical investigation.

- Clarity: Clearly defined without ambiguity.

- Specificity: Narrowly framed, avoiding vagueness.

- Feasibility: Realistic to conduct with available resources.

- Novelty: Offers new insights or challenges existing knowledge.

- Ethical considerations: Respect rights, dignity, and safety.

Why is research problem important?

A research problem is crucial because it identifies knowledge gaps, directs the inquiry’s focus, and forms the foundation for generating hypotheses or questions. It drives the methodology and determination of study relevance, ensuring that research contributes meaningfully to academic discourse and potentially addresses real-world challenges.

How do you write a research problem?

To write a research problem, identify a knowledge gap or an unresolved issue in your field. Start with a broad topic, then narrow it down. Clearly articulate the problem in a concise statement, ensuring it’s researchable, significant, and relevant. Ground it in the existing literature to highlight its importance and context.

How can we solve research problem?

To solve a research problem, start by conducting a thorough literature review. Formulate hypotheses or research questions. Choose an appropriate research methodology. Collect and analyse data systematically. Interpret findings in the context of existing knowledge. Ensure validity and reliability, and discuss implications, limitations, and potential future research directions.

You May Also Like

How to write a hypothesis for dissertation,? A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested with the help of experimental or theoretical research.

This article is a step-by-step guide to how to write statement of a problem in research. The research problem will be half-solved by defining it correctly.

Make sure that your selected topic is intriguing, manageable, and relevant. Here are some guidelines to help understand how to find a good dissertation topic.

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 1. Choosing a Research Problem

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

In the social and behavioral sciences, the subject of analysis is most often framed as a problem that must be researched in order to obtain a greater understanding, formulate a set of solutions or recommended courses of action, and/or develop a better approach to practice. The research problem, therefore, is the main organizing principle guiding the analysis of your research. The problem under investigation establishes an occasion for writing and a focus that governs what you want to say. It represents the core subject matter of scholarly communication and the means by which scholars arrive at other topics of conversation and the discovery of new knowledge and understanding.

Alvesson, Mats and Jörgen Sandberg. Constructing Research Questions: Doing Interesting Research . London: Sage, 2013; Jacobs, Ronald L. “Developing a Dissertation Research Problem: A Guide for Doctoral Students in Human Resource Development and Adult Education.” New Horizons in Adult Education and Human Resource Development 25 (Summer 2013): 103-117; Chapter 1: Research and the Research Problem. Nicholas Walliman . Your Research Project: Designing and Planning Your Work . 3rd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2011.

Choosing a Research Problem / How to Begin

Do not assume that identifying a research problem to investigate will be a quick and easy task! You should be thinking about it during the beginning of the course. There are generally three ways you are asked to write about a research problem : 1) your professor provides you with a general topic from which you study a particular aspect; 2) your professor provides you with a list of possible topics to study and you choose a topic from that list; or, 3) your professor leaves it up to you to choose a topic and you only have to obtain permission to write about it before beginning your investigation. Here are some strategies for getting started for each scenario.

I. How To Begin: You are given the topic to write about

Step 1 : Identify concepts and terms that make up the topic statement . For example, your professor wants the class to focus on the following research problem: “Is the European Union a credible security actor with the capacity to contribute to confronting global terrorism?" The main concepts in this problem are: European Union, security, global terrorism, credibility [ hint : focus on identifying proper nouns, nouns or noun phrases, and action verbs in the assignment description]. Step 2 : Review related literature to help refine how you will approach examining the topic and finding a way to analyze it . You can begin by doing any or all of the following: reading through background information from materials listed in your course syllabus; searching the USC Libraries Catalog to find a recent book on the topic and, if appropriate, more specialized works about the topic; conducting a preliminary review of the research literature using multidisciplinary databases such as ProQuest or subject-specific databases from the " By Subject Area " drop down menu located above the list of databases.

Choose the advanced search option in the database and enter into each search box the main concept terms you developed in Step 1. Also consider using their synonyms to retrieve additional relevant records. This will help you refine and frame the scope of the research problem. You will likely need to do this several times before you can finalize how to approach writing about the topic. NOTE: Always review the references from your most relevant research results cited by the authors in footnotes, endnotes, or a bibliography to locate related research on your topic. This is a good strategy for identifying important prior research about the topic because titles that are repeatedly cited indicate their significance in laying a foundation for understanding the problem. However, if you’re having trouble at this point locating relevant research literature, ask a librarian for help!

ANOTHER NOTE: If you find an article from a database that's particularly helpful, paste it into Google Scholar , placing the title of the article in quotes. If the article record appears, look for a "cited by" reference followed by a number [e.g., C ited by 37] just below the record. This link indicates how many times other scholars have subsequently cited that article in their own research since it was first published. This is an effective strategy for identifying more current, related research on your topic. Finding additional cited by references from your original list of cited by references helps you navigate through the literature and, by so doing, understand the evolution of thought around a particular research problem. Step 3 : Since social science research papers are generally designed to encourage you to develop your own ideas and arguments, look for sources that can help broaden, modify, or strengthen your initial thoughts and arguments. For example, if you decide to argue that the European Union is inadequately prepared to take on responsibilities for broader global security because of the debt crisis in many EU countries, then focus on identifying sources that support as well as refute this position. From the advanced search option in ProQuest , a sample search would use "European Union" in one search box, "global security" in the second search box, and adding a third search box to include "debt crisis."

There are least four appropriate roles your related literature plays in helping you formulate how to begin your analysis :

- Sources of criticism -- frequently, you'll find yourself reading materials that are relevant to your chosen topic, but you disagree with the author's position. Therefore, one way that you can use a source is to describe the counter-argument, provide evidence from your own review of the literature as to why the prevailing argument is unsatisfactory, and to discuss how your approach is more appropriate based upon your interpretation of the evidence.

- Sources of new ideas -- while a general goal in writing college research papers in the social sciences is to examine a research problem with some basic idea of what position you'd like to take and on what basis you'd like to defend your position, it is certainly acceptable [and often encouraged] to read the literature and extend, modify, and refine your own position in light of the ideas proposed by others. Just make sure that you cite the sources !

- Sources for historical context -- another role your related literature plays in formulating how to begin your analysis is to place issues and events in proper historical context. This can help to demonstrate familiarity with developments in relevant scholarship about your topic, provide a means of comparing historical versus contemporary issues and events, and identifying key people, places, and events that had an important role related to the research problem. Given its archival journal coverage, a good multidisciplnary database to use in this case is JSTOR .

- Sources of interdisciplinary insight -- an advantage of using databases like ProQuest to begin exploring your topic is that it covers publications from a variety of different disciplines. Another way to formulate how to study the topic is to look at it from different disciplinary perspectives. If the topic concerns immigration reform, for example, ask yourself, how do studies from sociological journals found by searching ProQuest vary in their analysis from those in political science journals. A goal in reviewing related literature is to provide a means of approaching a topic from multiple perspectives rather than the perspective offered from just one discipline.

NOTE: Remember to keep careful notes at every stage or utilize a citation management system like EndNotes or RefWorks . You may think you'll remember what you have searched and where you found things, but it’s easy to forget or get confused. Most databases have a search history feature that allows you to go back and see what searches you conducted previously as long as you haven't closed your session. If you start over, that history could be deleted.

Step 4 : Assuming you have done an effective job of synthesizing and thinking about the results of your initial search for related literature, you're ready to prepare a detailed outline for your paper that lays the foundation for a more in-depth and focused review of relevant research literature [after consulting with a librarian, if needed!]. How will you know you haven't done an effective job of synthesizing and thinking about the results of our initial search for related literature? A good indication is that you start composing the outline and gaps appear in how you want to approach the study. This indicates the need to gather further background information and analysis about the research problem.

II. How To Begin: You are provided a list of possible topics to choose from Step 1 : I know what you’re thinking--which topic on this list will be the easiest to find the most information on? An effective instructor would never include a topic that is so obscure or complex that no research is available to examine and from which to design an effective study. Therefore, don't approach a list of possible topics to study from the perspective of trying to identify the path of least resistance; choose a topic that you find interesting in some way, that is controversial and that you have a strong opinion about, that has some personal meaning for you, or relates to your major or a minor. You're going to be working on the topic for quite some time, so choose one that you find interesting and engaging or that motivates you to take a position. Embrace the opportunity to learn something new! Once you’ve settled on a topic of interest from the list provided by your professor, follow Steps 1 - 4 listed above to further develop it into a research paper.

NOTE: It’s ok to review related literature to help refine how you will approach analyzing a topic, and then discover that the topic isn’t all that interesting to you. In that case, choose a different topic from the list. Just don’t wait too long to make a switch and, of course, be sure to inform your professor that you are changing your topic.

III. How To Begin: Your professor leaves it up to you to choose a topic

Step 1 : Under this scenario, the key process is turning an idea or general thought into a topic that can be configured into a research problem. When given an assignment where you choose the topic, don't begin by thinking about what to write about, but rather, ask yourself the question, "What do I want to understand or learn about?" Treat an open-ended research assignment as an opportunity to gain new knowledge about something that's important or exciting to you in the context of the overall subject of the course.

Step 2 : If you lack ideas, or wish to gain focus, try any or all of the following strategies:

- Review your course readings, particularly the suggested readings, for topic ideas. Don't just review what you've already read, but jump ahead in the syllabus to readings that have not been covered yet.

- Search the USC Libraries Catalog for a recently published book and, if appropriate, more specialized works related to the discipline area of the course [e.g., for the course SOCI 335: Society and Population, search for books on "population and society" or "population and social impact"]. Reviewing the contents of a book about your area of interest can give you insight into what conversations scholars are having about the topic and, thus, how you might want to contribute your own ideas to these conversations through the research paper you write for the class.

- Browse through some current scholarly [a.k.a., academic, peer reviewed] journals in your subject discipline. Even if most of the articles are not relevant, you can skim through the contents quickly. You only need one to be the spark that begins the process of wanting to learn more about a topic. Consult with a librarian and/or your professor about what constitutes the core journals within the subject area of the writing assignment.

- Think about essays you have written for other courses you have taken or academic lectures and programs you have attended outside of class. Thinking back, ask yourself why did you want to take this class or attend this event? What interested you the most? What would you like to know more about? Place this question in the context of the current course assignment. Note that this strategy also applies to anything you've watched on TV or has been shared on social media.

- Search online news media sources, such as CNN , the Los Angeles Times , Huffington Post , MSNBC , Fox News , or Newsweek , to see if your idea has been covered by the media. Use this coverage to refine your idea into something that you'd like to investigate further, but in a more deliberate, scholarly way in relation to a particular problem that needs to be researched.

Step 3 : To build upon your initial idea, use the suggestions under this tab to help narrow , broaden , or increase the timeliness of your idea so you can write it out as a research problem.

Once you are comfortable with having turned your idea into a research problem, follow Steps 1 - 4 listed in Part I above to further develop it into an outline for a research paper.

Alderman, Jim. "Choosing a Research Topic." Beginning Library and Information Systems Strategies. Paper 17. Jacksonville, FL: University of North Florida Digital Commons, 2014; Alvesson, Mats and Jörgen Sandberg. Constructing Research Questions: Doing Interesting Research . London: Sage, 2013; Chapter 2: Choosing a Research Topic. Adrian R. Eley. Becoming a Successful Early Career Researcher . New York: Routledge, 2012; Answering the Question. Academic Skills Centre. University of Canberra; Brainstorming. Department of English Writing Guide. George Mason University; Brainstorming. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Chapter 1: Research and the Research Problem. Nicholas Walliman . Your Research Project: Designing and Planning Your Work . 3rd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2011; Choosing a Topic. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Mullaney, Thomas S. and Christopher Rea. Where Research Begins: Choosing a Research Project That Matters to You (and the World) . Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2022; Coming Up With Your Topic. Institute for Writing Rhetoric. Dartmouth College; How To Write a Thesis Statement. Writing Tutorial Services, Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. Indiana University; Identify Your Question. Start Your Research. University Library, University of California, Santa Cruz; The Process of Writing a Research Paper. Department of History. Trent University; Trochim, William M.K. Problem Formulation. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006.

Resources for Identifying a Topic

Resources for Identifying a Research Problem

If you are having difficulty identifying a topic to study or need basic background information, the following web resources and databases can be useful:

- CQ Researcher -- a collection of single-themed public policy reports that provide an overview of an issue. Each report includes background information, an assessment of the current policy situation, statistical tables and maps, pro/con statements from representatives of opposing positions, and a bibliography of key sources.

- New York Times Topics -- each topic page collects news articles, reference and archival information, photos, graphics, audio and video files. Content is available without charge on articles going back to 1981.

- Opposing Viewpoints In Context -- an online resource covering a wide range of social issues from a variety of perspectives. The database contains a media-rich collection of materials, including pro/con viewpoint essays, topic overviews, primary source materials, biographies of social activists and reformers, journal articles, statistical tables, charts and graphs, images, videos, and podcasts.

- Policy Commons -- platform for objective, fact-based research from the world’s leading policy experts, nonpartisan think tanks, and intergovernmental and non-governmental organizations. The database provides advanced searching across millions of pages of books, articles, working papers, reports, policy briefs, data sets, tables, charts, media, case studies, and statistical publications, including archived reports from more than 200 defunct think tanks. Coverage is international in scope.

Descriptions of resources are adapted or quoted from vendor websites.

Writing Tip

Not Finding Anything on Your Topic? Ask a Librarian!

Don't assume or jump to the conclusion that your topic is too narrowly defined or obscure just because your initial search has failed to identify relevant research. Librarians are experts in locating and critically assessing information and how it is organized. This knowledge will help you develop strategies for analyzing existing knowledge in new ways. Therefore, always consult with a librarian before you consider giving up on finding information about the topic you want to investigate. If there isn't a lot of information about your topic, a librarian can help you identify a closely related topic that you can study. Use the Ask-A-Librarian link above to identify a librarian in your subject area.

Another Writing Tip

Don't be a Martyr!

In thinking about what to study, don't adopt the mindset of pursuing an esoteric or overly complicated topic just to impress your professor but that, in reality, does not have any real interest to you. Choose a topic that is challenging but that has at least some interest to you or that you care about. Obviously, this is easier for courses within your major, but even for those nasty prerequisite classes that you must take in order to graduate [and that provide an additional tuition revenue for the university], try to apply issues associated with your major to the general topic given to you. For example, if you are an international relations major taking a GE philosophy class where the assignment asks you to apply the question of "what is truth" to some aspect of life, you could choose to study how government leaders attempt to shape truth through the use of nationalistic propaganda.

Still Another Writing Tip

A Research Problem is Not a Thesis Statement

A thesis statement and a research problem are two different parts of the introduction section of your paper. The thesis statement succinctly describes in one or two sentences, usually in the last paragraph of the introduction, what position you have reached about a topic. It includes an assertion that requires evidence and support along with your opinion or argument about what you are researching. There are three general types of thesis statements: analytical statements that break down and evaluate the topic; argumentative statements that make a claim about the topic and defend that claim; and, expository statements that present facts and research about the topic. Each are intended to set forth a claim that you will seek to validate through the research you describe in your paper.

Before the thesis statement, your introduction must include a description of a problem that describes either a key area of concern, a condition to be improved upon, a difficulty to be eliminated, or a troubling issue that exists . The research problem describes something that can be empirically verified and measured; it is often followed by a set of questions that underpin how you plan to approach investigating that problem. In short, the thesis statement states your opinion or argument about the research problem and summarizes how you plan to address it.

Tips and Examples for Writing Thesis Statements. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Write a Strong Thesis Statement! The Writing Center, University of Evansville; Thesis Statements. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Tutorial #26: Thesis Statements and Topic Sentences. Writing Center, College of San Mateo; Creswell, John W. and J. David Creswell. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches . 5th edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2017.

- << Previous: Glossary of Research Terms

- Next: Reading Research Effectively >>

- Last Updated: May 25, 2024 4:09 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Root out friction in every digital experience, super-charge conversion rates, and optimize digital self-service

Uncover insights from any interaction, deliver AI-powered agent coaching, and reduce cost to serve

Increase revenue and loyalty with real-time insights and recommendations delivered to teams on the ground

Know how your people feel and empower managers to improve employee engagement, productivity, and retention

Take action in the moments that matter most along the employee journey and drive bottom line growth

Whatever they’re are saying, wherever they’re saying it, know exactly what’s going on with your people

Get faster, richer insights with qual and quant tools that make powerful market research available to everyone

Run concept tests, pricing studies, prototyping + more with fast, powerful studies designed by UX research experts

Track your brand performance 24/7 and act quickly to respond to opportunities and challenges in your market

Explore the platform powering Experience Management

- Free Account

- For Digital

- For Customer Care

- For Human Resources

- For Researchers

- Financial Services

- All Industries

Popular Use Cases

- Customer Experience

- Employee Experience

- Net Promoter Score

- Voice of Customer

- Customer Success Hub

- Product Documentation

- Training & Certification

- XM Institute

- Popular Resources

- Customer Stories

- Artificial Intelligence

- Market Research

- Partnerships

- Marketplace

The annual gathering of the experience leaders at the world’s iconic brands building breakthrough business results, live in Salt Lake City.

- English/AU & NZ

- Español/Europa

- Español/América Latina

- Português Brasileiro

- REQUEST DEMO

Academic Experience

How to identify and resolve research problems

Updated July 12, 2023

In this article, we’re going to take you through one of the most pertinent parts of conducting research: a research problem (also known as a research problem statement).

When trying to formulate a good research statement, and understand how to solve it for complex projects, it can be difficult to know where to start.

Not only are there multiple perspectives (from stakeholders to project marketers who want answers), you have to consider the particular context of the research topic: is it timely, is it relevant and most importantly of all, is it valuable?

In other words: are you looking at a research worthy problem?

The fact is, a well-defined, precise, and goal-centric research problem will keep your researchers, stakeholders, and business-focused and your results actionable.

And when it works well, it's a powerful tool to identify practical solutions that can drive change and secure buy-in from your workforce.

Free eBook: The ultimate guide to market research

What is a research problem?

In social research methodology and behavioral sciences , a research problem establishes the direction of research, often relating to a specific topic or opportunity for discussion.

For example: climate change and sustainability, analyzing moral dilemmas or wage disparity amongst classes could all be areas that the research problem focuses on.

As well as outlining the topic and/or opportunity, a research problem will explain:

- why the area/issue needs to be addressed,

- why the area/issue is of importance,

- the parameters of the research study

- the research objective

- the reporting framework for the results and

- what the overall benefit of doing so will provide (whether to society as a whole or other researchers and projects).

Having identified the main topic or opportunity for discussion, you can then narrow it down into one or several specific questions that can be scrutinized and answered through the research process.

What are research questions?

Generating research questions underpinning your study usually starts with problems that require further research and understanding while fulfilling the objectives of the study.

A good problem statement begins by asking deeper questions to gain insights about a specific topic.

For example, using the problems above, our questions could be:

"How will climate change policies influence sustainability standards across specific geographies?"

"What measures can be taken to address wage disparity without increasing inflation?"

Developing a research worthy problem is the first step - and one of the most important - in any kind of research.

It’s also a task that will come up again and again because any business research process is cyclical. New questions arise as you iterate and progress through discovering, refining, and improving your products and processes. A research question can also be referred to as a "problem statement".

Note: good research supports multiple perspectives through empirical data. It’s focused on key concepts rather than a broad area, providing readily actionable insight and areas for further research.

Research question or research problem?

As we've highlighted, the terms “research question” and “research problem” are often used interchangeably, becoming a vague or broad proposition for many.

The term "problem statement" is far more representative, but finds little use among academics.

Instead, some researchers think in terms of a single research problem and several research questions that arise from it.

As mentioned above, the questions are lines of inquiry to explore in trying to solve the overarching research problem.

Ultimately, this provides a more meaningful understanding of a topic area.

It may be useful to think of questions and problems as coming out of your business data – that’s the O-data (otherwise known as operational data) like sales figures and website metrics.

What's an example of a research problem?

Your overall research problem could be: "How do we improve sales across EMEA and reduce lost deals?"

This research problem then has a subset of questions, such as:

"Why do sales peak at certain times of the day?"

"Why are customers abandoning their online carts at the point of sale?"

As well as helping you to solve business problems, research problems (and associated questions) help you to think critically about topics and/or issues (business or otherwise). You can also use your old research to aid future research -- a good example is laying the foundation for comparative trend reports or a complex research project.

(Also, if you want to see the bigger picture when it comes to research problems, why not check out our ultimate guide to market research? In it you'll find out: what effective market research looks like, the use cases for market research, carrying out a research study, and how to examine and action research findings).

The research process: why are research problems important?

A research problem has two essential roles in setting your research project on a course for success.

1. They set the scope

The research problem defines what problem or opportunity you’re looking at and what your research goals are. It stops you from getting side-tracked or allowing the scope of research to creep off-course .

Without a strong research problem or problem statement, your team could end up spending resources unnecessarily, or coming up with results that aren’t actionable - or worse, harmful to your business - because the field of study is too broad.

2. They tie your work to business goals and actions

To formulate a research problem in terms of business decisions means you always have clarity on what’s needed to make those decisions. You can show the effects of what you’ve studied using real outcomes.

Then, by focusing your research problem statement on a series of questions tied to business objectives, you can reduce the risk of the research being unactionable or inaccurate.

It's also worth examining research or other scholarly literature (you’ll find plenty of similar, pertinent research online) to see how others have explored specific topics and noting implications that could have for your research.

Four steps to defining your research problem

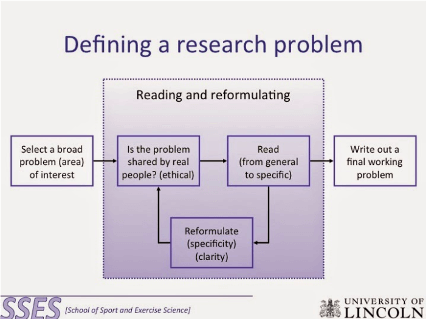

Image credit: http://myfreeschooltanzania.blogspot.com/2014/11/defining-research-problem.html

1. Observe and identify

Businesses today have so much data that it can be difficult to know which problems to address first. Researchers also have business stakeholders who come to them with problems they would like to have explored. A researcher’s job is to sift through these inputs and discover exactly what higher-level trends and key concepts are worth investing in.

This often means asking questions and doing some initial investigation to decide which avenues to pursue. This could mean gathering interdisciplinary perspectives identifying additional expertise and contextual information.

Sometimes, a small-scale preliminary study might be worth doing to help get a more comprehensive understanding of the business context and needs, and to make sure your research problem addresses the most critical questions.

This could take the form of qualitative research using a few in-depth interviews , an environmental scan, or reviewing relevant literature.

The sales manager of a sportswear company has a problem: sales of trail running shoes are down year-on-year and she isn’t sure why. She approaches the company’s research team for input and they begin asking questions within the company and reviewing their knowledge of the wider market.

2. Review the key factors involved

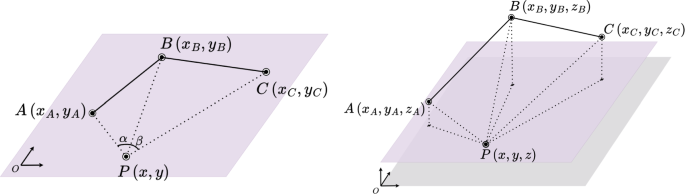

As a marketing researcher, you must work closely with your team of researchers to define and test the influencing factors and the wider context involved in your study. These might include demographic and economic trends or the business environment affecting the question at hand. This is referred to as a relational research problem.

To do this, you have to identify the factors that will affect the research and begin formulating different methods to control them.

You also need to consider the relationships between factors and the degree of control you have over them. For example, you may be able to control the loading speed of your website but you can’t control the fluctuations of the stock market.

Doing this will help you determine whether the findings of your project will produce enough information to be worth the cost.

You need to determine:

- which factors affect the solution to the research proposal.

- which ones can be controlled and used for the purposes of the company, and to what extent.

- the functional relationships between the factors.

- which ones are critical to the solution of the research study.

The research team at the running shoe company is hard at work. They explore the factors involved and the context of why YoY sales are down for trail shoes, including things like what the company’s competitors are doing, what the weather has been like – affecting outdoor exercise – and the relative spend on marketing for the brand from year to year.

The final factor is within the company’s control, although the first two are not. They check the figures and determine marketing spend has a significant impact on the company.

3. Prioritize

Once you and your research team have a few observations, prioritize them based on their business impact and importance. It may be that you can answer more than one question with a single study, but don’t do it at the risk of losing focus on your overarching research problem.

Questions to ask:

- Who? Who are the people with the problem? Are they end-users, stakeholders, teams within your business? Have you validated the information to see what the scale of the problem is?

- What? What is its nature and what is the supporting evidence?

- Why? What is the business case for solving the problem? How will it help?

- Where? How does the problem manifest and where is it observed?

To help you understand all dimensions, you might want to consider focus groups or preliminary interviews with external (including consumers and existing customers) and internal (salespeople, managers, and other stakeholders) parties to provide what is sometimes much-needed insight into a particular set of questions or problems.

After observing and investigating, the running shoe researchers come up with a few candidate questions, including:

- What is the relationship between US average temperatures and sales of our products year on year?

- At present, how does our customer base rank Competitor X and Competitor Y’s trail running shoe compared to our brand?

- What is the relationship between marketing spend and trail shoe product sales over the last 12 months?

They opt for the final question, because the variables involved are fully within the company’s control, and based on their initial research and stakeholder input, seem the most likely cause of the dive in sales. The research question is specific enough to keep the work on course towards an actionable result, but it allows for a few different avenues to be explored, such as the different budget allocations of offline and online marketing and the kinds of messaging used.

Get feedback from the key teams within your business to make sure everyone is aligned and has the same understanding of the research problem and questions, and the actions you hope to take based on the results. Now is also a good time to demonstrate the ROI of your research and lay out its potential benefits to your stakeholders.

Different groups may have different goals and perspectives on the issue. This step is vital for getting the necessary buy-in and pushing the project forward.

The running shoe company researchers now have everything they need to begin. They call a meeting with the sales manager and consult with the product team, marketing team, and C-suite to make sure everyone is aligned and has bought into the direction of the research topic. They identify and agree that the likely course of action will be a rethink of how marketing resources are allocated, and potentially testing out some new channels and messaging strategies .

Can you explore a broad area and is it practical to do so?

A broader research problem or report can be a great way to bring attention to prevalent issues, societal or otherwise, but are often undertaken by those with the resources to do so.

Take a typical government cybersecurity breach survey, for example. Most of these reports raise awareness of cybercrime, from the day-to-day threats businesses face to what security measures some organizations are taking. What these reports don't do, however, is provide actionable advice - mostly because every organization is different.

The point here is that while some researchers will explore a very complex issue in detail, others will provide only a snapshot to maintain interest and encourage further investigation. The "value" of the data is wholly determined by the recipients of it - and what information you choose to include.

To summarize, it can be practical to undertake a broader research problem, certainly, but it may not be possible to cover everything or provide the detail your audience needs. Likewise, a more systematic investigation of an issue or topic will be more valuable, but you may also find that you cover far less ground.

It's important to think about your research objectives and expected findings before going ahead.

Ensuring your research project is a success

A complex research project can be made significantly easier with clear research objectives, a descriptive research problem, and a central focus. All of which we've outlined in this article.

If you have previous research, even better. Use it as a benchmark

Remember: what separates a good research paper from an average one is actually very simple: valuable, empirical data that explores a prevalent societal or business issue and provides actionable insights.

And we can help.

Sophisticated research made simple with Qualtrics

Trusted by the world's best brands, our platform enables researchers from academic to corporate to tackle the hardest challenges and deliver the results that matter.

Our CoreXM platform supports the methods that define superior research and delivers insights in real-time. It's easy to use (thanks to drag-and-drop functionality) and requires no coding, meaning you'll be capturing data and gleaning insights in no time.

It also excels in flexibility; you can track consumer behavior across segments , benchmark your company versus competitors , carry out complex academic research, and do much more, all from one system.

It's one platform with endless applications, so no matter your research problem, we've got the tools to help you solve it. And if you don't have a team of research experts in-house, our market research team has the practical knowledge and tools to help design the surveys and find the respondents you need.

Of course, you may want to know where to begin with your own market research . If you're struggling, make sure to download our ultimate guide using the link below.

It's got everything you need and there’s always information in our research methods knowledge base.

Scott Smith

Scott Smith, Ph.D. is a contributor to the Qualtrics blog.

Related Articles

April 1, 2023

How to write great survey questions (with examples)

February 8, 2023

Smoothing the transition from school to work with work-based learning

December 6, 2022

How customer experience helps bring Open Universities Australia’s brand promise to life

August 18, 2022

School safety, learning gaps top of mind for parents this back-to-school season

August 9, 2022

3 things that will improve your teachers’ school experience

August 2, 2022

Why a sense of belonging at school matters for K-12 students

July 14, 2022

Improve the student experience with simplified course evaluations

March 17, 2022

Understanding what’s important to college students

Stay up to date with the latest xm thought leadership, tips and news., request demo.

Ready to learn more about Qualtrics?

The Research Problem & Statement

What they are & how to write them (with examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewed By: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) | March 2023

If you’re new to academic research, you’re bound to encounter the concept of a “ research problem ” or “ problem statement ” fairly early in your learning journey. Having a good research problem is essential, as it provides a foundation for developing high-quality research, from relatively small research papers to a full-length PhD dissertations and theses.

In this post, we’ll unpack what a research problem is and how it’s related to a problem statement . We’ll also share some examples and provide a step-by-step process you can follow to identify and evaluate study-worthy research problems for your own project.

Overview: Research Problem 101

What is a research problem.

- What is a problem statement?

Where do research problems come from?

- How to find a suitable research problem

- Key takeaways

A research problem is, at the simplest level, the core issue that a study will try to solve or (at least) examine. In other words, it’s an explicit declaration about the problem that your dissertation, thesis or research paper will address. More technically, it identifies the research gap that the study will attempt to fill (more on that later).

Let’s look at an example to make the research problem a little more tangible.

To justify a hypothetical study, you might argue that there’s currently a lack of research regarding the challenges experienced by first-generation college students when writing their dissertations [ PROBLEM ] . As a result, these students struggle to successfully complete their dissertations, leading to higher-than-average dropout rates [ CONSEQUENCE ]. Therefore, your study will aim to address this lack of research – i.e., this research problem [ SOLUTION ].

A research problem can be theoretical in nature, focusing on an area of academic research that is lacking in some way. Alternatively, a research problem can be more applied in nature, focused on finding a practical solution to an established problem within an industry or an organisation. In other words, theoretical research problems are motivated by the desire to grow the overall body of knowledge , while applied research problems are motivated by the need to find practical solutions to current real-world problems (such as the one in the example above).

As you can probably see, the research problem acts as the driving force behind any study , as it directly shapes the research aims, objectives and research questions , as well as the research approach. Therefore, it’s really important to develop a very clearly articulated research problem before you even start your research proposal . A vague research problem will lead to unfocused, potentially conflicting research aims, objectives and research questions .

What is a research problem statement?

As the name suggests, a problem statement (within a research context, at least) is an explicit statement that clearly and concisely articulates the specific research problem your study will address. While your research problem can span over multiple paragraphs, your problem statement should be brief , ideally no longer than one paragraph . Importantly, it must clearly state what the problem is (whether theoretical or practical in nature) and how the study will address it.

Here’s an example of a statement of the problem in a research context:

Rural communities across Ghana lack access to clean water, leading to high rates of waterborne illnesses and infant mortality. Despite this, there is little research investigating the effectiveness of community-led water supply projects within the Ghanaian context. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the effectiveness of such projects in improving access to clean water and reducing rates of waterborne illnesses in these communities.

As you can see, this problem statement clearly and concisely identifies the issue that needs to be addressed (i.e., a lack of research regarding the effectiveness of community-led water supply projects) and the research question that the study aims to answer (i.e., are community-led water supply projects effective in reducing waterborne illnesses?), all within one short paragraph.

Need a helping hand?

Wherever there is a lack of well-established and agreed-upon academic literature , there is an opportunity for research problems to arise, since there is a paucity of (credible) knowledge. In other words, research problems are derived from research gaps . These gaps can arise from various sources, including the emergence of new frontiers or new contexts, as well as disagreements within the existing research.

Let’s look at each of these scenarios:

New frontiers – new technologies, discoveries or breakthroughs can open up entirely new frontiers where there is very little existing research, thereby creating fresh research gaps. For example, as generative AI technology became accessible to the general public in 2023, the full implications and knock-on effects of this were (or perhaps, still are) largely unknown and therefore present multiple avenues for researchers to explore.

New contexts – very often, existing research tends to be concentrated on specific contexts and geographies. Therefore, even within well-studied fields, there is often a lack of research within niche contexts. For example, just because a study finds certain results within a western context doesn’t mean that it would necessarily find the same within an eastern context. If there’s reason to believe that results may vary across these geographies, a potential research gap emerges.

Disagreements – within many areas of existing research, there are (quite naturally) conflicting views between researchers, where each side presents strong points that pull in opposing directions. In such cases, it’s still somewhat uncertain as to which viewpoint (if any) is more accurate. As a result, there is room for further research in an attempt to “settle” the debate.

Of course, many other potential scenarios can give rise to research gaps, and consequently, research problems, but these common ones are a useful starting point. If you’re interested in research gaps, you can learn more here .

How to find a research problem

Given that research problems flow from research gaps , finding a strong research problem for your research project means that you’ll need to first identify a clear research gap. Below, we’ll present a four-step process to help you find and evaluate potential research problems.

If you’ve read our other articles about finding a research topic , you’ll find the process below very familiar as the research problem is the foundation of any study . In other words, finding a research problem is much the same as finding a research topic.

Step 1 – Identify your area of interest

Naturally, the starting point is to first identify a general area of interest . Chances are you already have something in mind, but if not, have a look at past dissertations and theses within your institution to get some inspiration. These present a goldmine of information as they’ll not only give you ideas for your own research, but they’ll also help you see exactly what the norms and expectations are for these types of projects.

At this stage, you don’t need to get super specific. The objective is simply to identify a couple of potential research areas that interest you. For example, if you’re undertaking research as part of a business degree, you may be interested in social media marketing strategies for small businesses, leadership strategies for multinational companies, etc.

Depending on the type of project you’re undertaking, there may also be restrictions or requirements regarding what topic areas you’re allowed to investigate, what type of methodology you can utilise, etc. So, be sure to first familiarise yourself with your institution’s specific requirements and keep these front of mind as you explore potential research ideas.

Step 2 – Review the literature and develop a shortlist

Once you’ve decided on an area that interests you, it’s time to sink your teeth into the literature . In other words, you’ll need to familiarise yourself with the existing research regarding your interest area. Google Scholar is a good starting point for this, as you can simply enter a few keywords and quickly get a feel for what’s out there. Keep an eye out for recent literature reviews and systematic review-type journal articles, as these will provide a good overview of the current state of research.

At this stage, you don’t need to read every journal article from start to finish . A good strategy is to pay attention to the abstract, intro and conclusion , as together these provide a snapshot of the key takeaways. As you work your way through the literature, keep an eye out for what’s missing – in other words, what questions does the current research not answer adequately (or at all)? Importantly, pay attention to the section titled “ further research is needed ”, typically found towards the very end of each journal article. This section will specifically outline potential research gaps that you can explore, based on the current state of knowledge (provided the article you’re looking at is recent).

Take the time to engage with the literature and develop a big-picture understanding of the current state of knowledge. Reviewing the literature takes time and is an iterative process , but it’s an essential part of the research process, so don’t cut corners at this stage.

As you work through the review process, take note of any potential research gaps that are of interest to you. From there, develop a shortlist of potential research gaps (and resultant research problems) – ideally 3 – 5 options that interest you.

Step 3 – Evaluate your potential options

Once you’ve developed your shortlist, you’ll need to evaluate your options to identify a winner. There are many potential evaluation criteria that you can use, but we’ll outline three common ones here: value, practicality and personal appeal.

Value – a good research problem needs to create value when successfully addressed. Ask yourself:

- Who will this study benefit (e.g., practitioners, researchers, academia)?

- How will it benefit them specifically?

- How much will it benefit them?

Practicality – a good research problem needs to be manageable in light of your resources. Ask yourself:

- What data will I need access to?

- What knowledge and skills will I need to undertake the analysis?

- What equipment or software will I need to process and/or analyse the data?

- How much time will I need?

- What costs might I incur?

Personal appeal – a research project is a commitment, so the research problem that you choose needs to be genuinely attractive and interesting to you. Ask yourself:

- How appealing is the prospect of solving this research problem (on a scale of 1 – 10)?

- Why, specifically, is it attractive (or unattractive) to me?

- Does the research align with my longer-term goals (e.g., career goals, educational path, etc)?

Depending on how many potential options you have, you may want to consider creating a spreadsheet where you numerically rate each of the options in terms of these criteria. Remember to also include any criteria specified by your institution . From there, tally up the numbers and pick a winner.

Step 4 – Craft your problem statement

Once you’ve selected your research problem, the final step is to craft a problem statement. Remember, your problem statement needs to be a concise outline of what the core issue is and how your study will address it. Aim to fit this within one paragraph – don’t waffle on. Have a look at the problem statement example we mentioned earlier if you need some inspiration.

Key Takeaways

We’ve covered a lot of ground. Let’s do a quick recap of the key takeaways:

- A research problem is an explanation of the issue that your study will try to solve. This explanation needs to highlight the problem , the consequence and the solution or response.

- A problem statement is a clear and concise summary of the research problem , typically contained within one paragraph.

- Research problems emerge from research gaps , which themselves can emerge from multiple potential sources, including new frontiers, new contexts or disagreements within the existing literature.

- To find a research problem, you need to first identify your area of interest , then review the literature and develop a shortlist, after which you’ll evaluate your options, select a winner and craft a problem statement .

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

I APPRECIATE YOUR CONCISE AND MIND-CAPTIVATING INSIGHTS ON THE STATEMENT OF PROBLEMS. PLEASE I STILL NEED SOME SAMPLES RELATED TO SUICIDES.

Very pleased and appreciate clear information.

Your videos and information have been a life saver for me throughout my dissertation journey. I wish I’d discovered them sooner. Thank you!

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

How to formulate research problems?

June 16, 2023 4 min read

One of the most important steps in the research process is formulating a research problem. It establishes the framework for the whole study and directs the researcher in determining the research’s emphasis, scope, and goals. An effective research technique may be created with the support of a clearly defined research topic, which also aids in the generation of pertinent research questions.

This article will provide a general overview of the procedure involved in defining research problems, highlighting important considerations and steps researchers should take to formulate precise and insightful research problems.

What is a research problem?

It refers to a specific topic, problem, or knowledge gap that a researcher aims to study and address through a systematic inquiry. It establishes the foundation for a research project and guides the entire investigation.

When creating a research problem, researchers often start with a topic of interest before focusing on a particular issue or question. A substantial, relevant, and original challenge adds to the corpus of knowledge and has real-world applications.

A clearly stated research topic aids in the concentration of research resources and efforts, permits the development of an effective research technique, and directs the evaluation and interpretation of data acquired. It also helps in developing research goals and hypotheses by giving the investigation a distinct direction.

For instance, a research problem could be “What are the causes leading to the decline of bee populations in urban areas?” — This study challenge addresses a particular set of urban regions and draws attention to the problem of dwindling bee numbers. By focusing on this issue, researchers may analyze the various reasons for the loss, analyze how it affects the environment, and suggest conservation tactics.

Characteristics of an effective research problem

An effective research problem possesses several essential qualities that enhance its quality and suitability for examination. The key characteristics of a strong research problem are:

Significance

Should address an important issue or knowledge gap in the field of study, contributing to the existing body of knowledge.

Should be precisely stated, avoiding vague or overly general statements and providing a clear and concise description. This clarity enables the definition of research objectives and hypotheses and guides the research process.

Feasibility

Should be feasible in terms of the available time, resources, and skills. It can be realistically pursued, given the researcher’s capabilities and study circumstances. Sufficient data, research tools, and potential exploration paths should be reasonably accessible.

Should explore new facets, angles, or dimensions of the subject, offering fresh perspectives or approaches. This characteristic promotes intellectual progress and distinguishes the research from previous investigations.

Measurability

Should be formulated in a way that allows for empirical examination and the generation of quantifiable results. Data can be systematically collected and analyzed to answer the research questions or achieve the research goals, enhancing the objectivity and rigor of the research process.

Relevance and applicability

Should address relevant issues or help develop useful guidelines, regulations, or actions. It is more effective when it impacts multiple stakeholders and has the potential to produce practical results.

Interest and motivation

Should be intellectually engaging and interesting to the researcher and the academic community. It sparks curiosity and encourages further research, leading to high-quality research output.

Ethical consideration

Should adhere to ethical principles and rules, considering the welfare and rights of participants or subjects involved in the study.

ALSO READ: What is research design?

Types of research problems.

Research problems can be categorized into different types based on their nature and scope. The three most common types are:

Theoretical

It involves using theoretical frameworks, concepts, and models to investigate a subject or event. Theoretical research aims to extend existing knowledge, address unsolved disputes or gaps, or critique and evaluate preexisting theories.

It focuses on specific problems or challenges within a particular industry or sector and aims to provide practical solutions through systematic research. Applied research aims to bridge the gap between theory and practical application, optimizing existing processes, technologies, products, or services.

Action research combines research and action to address real-world issues. It encompasses problem-solving in various contexts, such as organizations, education, community development, policy implementation, and personal or professional development. Action research is flexible and can be tailored to different situations and issues.

Importance of research problems

Research problems play a vital role in shaping the direction and course of an investigation. They serve as the foundation for the entire research process, guiding researchers in their pursuit of knowledge and advancement in a specific field. The importance of research problems lies in the following:

Identifying knowledge gaps

Research problems help identify areas where knowledge is lacking or incomplete, highlighting the need for further investigation and addressing unanswered questions.

Providing direction

A well-defined research problem gives the research project focus and direction. It aids in the development of an effective research design, technique and the establishment of research objectives and questions.

Justifying the study’s significance

A clear research problem helps researchers justify the value and importance of their study by emphasizing its relevance, potential benefits, and contributions to the field.

Facilitating problem-solving and decision-making

Research problems often stem from real-world challenges or problems. By examining these problems, researchers can develop innovative ideas, methods, or strategies to solve practical issues or guide decision-making.

Advancing theory and knowledge

Research problems serve as a basis for developing new concepts, hypotheses, or models. By addressing research challenges, researchers contribute to understanding a subject, debunk preexisting beliefs, or propose new hypotheses.

Promoting intellectual curiosity and innovation

Research problems encourage intellectual curiosity and innovation by pushing researchers to explore fresh perspectives and methodologies. By encouraging critical thinking, generating original ideas, and developing unique research approaches, research problems foster innovation and creativity.

ALSO READ: The basics of market research

5 steps to formulate research problems.

Formulating research problems is a crucial initial step in conducting purposeful and targeted research. Here are five steps to follow:

Identify the broad research area

Determine the broad subject or field that interests you, considering discipline-specific topics or specific phenomena.

Conduct a literature review

Review existing literature and research in your chosen field to understand the current knowledge level and identify gaps or unsolved issues and areas requiring further research. Read relevant scholarly publications, books, and articles to gain a comprehensive understanding.

Narrow down the focus

Based on the literature review, select a specific component or subject within your chosen research field. Look for inconsistencies, contradictions, or open-ended questions in the existing literature that can present challenges for future research. Refine your research topic and focus it on a single problem or phenomenon.

Define clear objectives

Establish clear and concise research objectives that outline your investigation’s specific aims or outcomes. SMART (specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and time-bound) objectives help maintain focus and guide the research process effectively.

Formulate research questions

Create distinct research questions or hypotheses that align with your research problem and objectives. Qualitative research often utilizes research questions, while quantitative research employs hypotheses. Ensure these inquiries or hypotheses are precise, concise, and aimed at addressing the stated research problem.

Remember that formulating research problems is an iterative process. As you learn more about the topic and develop new ideas, it can need several changes and improvements. You may establish a solid basis for your study and improve your chances of performing fruitful and influential research by adhering to these recommendations and continually improving your research problem.

Researchers can create precise and insightful research problems that add to the body of knowledge and progress in their particular fields of study by using the procedures described in this article. A research problem outlines the precise field of inquiry and knowledge gaps that the research attempts to address, defining the scope and objective of a study.

Photo by Scott Graham on Unsplash

- Market Research

- Survey Design

- #research design

- #research problem

- #research strategy

The latest trends in the US healthtech…

CX Case Study: Brands that cracked market…

Generative research: a complete guide to running….

Get the latest market research insights

Community Blog

Keep up-to-date on postgraduate related issues with our quick reads written by students, postdocs, professors and industry leaders.

Types of Research – Explained with Examples

- By DiscoverPhDs

- October 2, 2020

Types of Research

Research is about using established methods to investigate a problem or question in detail with the aim of generating new knowledge about it.

It is a vital tool for scientific advancement because it allows researchers to prove or refute hypotheses based on clearly defined parameters, environments and assumptions. Due to this, it enables us to confidently contribute to knowledge as it allows research to be verified and replicated.

Knowing the types of research and what each of them focuses on will allow you to better plan your project, utilises the most appropriate methodologies and techniques and better communicate your findings to other researchers and supervisors.

Classification of Types of Research

There are various types of research that are classified according to their objective, depth of study, analysed data, time required to study the phenomenon and other factors. It’s important to note that a research project will not be limited to one type of research, but will likely use several.

According to its Purpose

Theoretical research.

Theoretical research, also referred to as pure or basic research, focuses on generating knowledge , regardless of its practical application. Here, data collection is used to generate new general concepts for a better understanding of a particular field or to answer a theoretical research question.

Results of this kind are usually oriented towards the formulation of theories and are usually based on documentary analysis, the development of mathematical formulas and the reflection of high-level researchers.

Applied Research

Here, the goal is to find strategies that can be used to address a specific research problem. Applied research draws on theory to generate practical scientific knowledge, and its use is very common in STEM fields such as engineering, computer science and medicine.

This type of research is subdivided into two types:

- Technological applied research : looks towards improving efficiency in a particular productive sector through the improvement of processes or machinery related to said productive processes.

- Scientific applied research : has predictive purposes. Through this type of research design, we can measure certain variables to predict behaviours useful to the goods and services sector, such as consumption patterns and viability of commercial projects.

According to your Depth of Scope

Exploratory research.

Exploratory research is used for the preliminary investigation of a subject that is not yet well understood or sufficiently researched. It serves to establish a frame of reference and a hypothesis from which an in-depth study can be developed that will enable conclusive results to be generated.

Because exploratory research is based on the study of little-studied phenomena, it relies less on theory and more on the collection of data to identify patterns that explain these phenomena.

Descriptive Research

The primary objective of descriptive research is to define the characteristics of a particular phenomenon without necessarily investigating the causes that produce it.

In this type of research, the researcher must take particular care not to intervene in the observed object or phenomenon, as its behaviour may change if an external factor is involved.

Explanatory Research

Explanatory research is the most common type of research method and is responsible for establishing cause-and-effect relationships that allow generalisations to be extended to similar realities. It is closely related to descriptive research, although it provides additional information about the observed object and its interactions with the environment.

Correlational Research

The purpose of this type of scientific research is to identify the relationship between two or more variables. A correlational study aims to determine whether a variable changes, how much the other elements of the observed system change.

According to the Type of Data Used

Qualitative research.

Qualitative methods are often used in the social sciences to collect, compare and interpret information, has a linguistic-semiotic basis and is used in techniques such as discourse analysis, interviews, surveys, records and participant observations.