- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

A Comprehensive Guide to Verbal Linguistic Intelligence

Do you love reading, writing, and languages?

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

andreswd / E+ / Getty

- Characteristics

- Developing Verbal Linguistic Skills

- Real-World Applications

- Enhancing These Skills in Kids

Verbal-linguistic intelligence involves the capacity to understand and reason with words and language. People with strong verbal-linguistic intelligence are skilled in reading, writing, listening , and communicating. They are adept at getting their messages across in words and often enjoy doing things like reading books, writing stories, or solving word problems.

"Verbal-linguistic intelligence is the ability to understand and effectively explain concepts through language or words," explains Courtney Morgan, LPCC, a licensed therapist and founder of Counseling Unconditionally . "A person with high levels of verbal-linguistic intelligence is able to comprehend and verbally explain things effectively."

This concept is part of Howard Gardner's theory of multiple intelligences , which suggests that there are several different forms of intelligence based on specific strengths and abilities. Verbal-linguistic intelligence refers to the capacity to understand the nuances of written and spoken language. People with this capacity are great communicators and often excel in writing, editing, teaching, journalism, or law careers.

At a Glance

If you love reading and writing, are great at word games, and tend to pick up foreign languages easily, then you probably have a high level of verbal linguistic intelligence. People with this type of intelligence tend to do well in school and careers that rely on communication abilities. Keep reading to learn more about the key characteristics of this type of intelligence and how you can strengthen these skills in yourself and in your kids.

Characteristics of Verbal Linguistic Intelligence

Some of the traits and characteristics of people who are high in verbal-linguistic intelligence include the following:

Appreciate the Power of Words

The verbal linguistic type of intelligence is all about having a love for words. People who excel in this area love using, hearing, and expressing themselves through language. They live for their Libby app to download books from their public library, have a stack of journals on their desk, and love to have a good debate over the correct use of a specific word.

When it comes to psychotherapy, people with this type of intelligence may find bibliotherapy particularly helpful. This type of therapy utilizes literature to help people connect what they read in stories with what they are experiencing in their own lives.

Strong Vocabularies

They also have an extensive and diverse lexicon that allows them to effortlessly inject daily conversations with sometimes esoteric terms that might send others running to the nearest dictionary. Their vocabulary is rich and varied, and they are great at picking up the meaning of new terms based on context.

Love for Reading and Writing

People with high verbal linguistic intelligence are skilled at understanding and communicating with the written word. They are often described as bookworms and often prefer to express themselves through writing (which is why you might find them texting rather than returning phone calls).

Strong Memory for Words, Phrases, and Quotes

People with this type of intelligence are often good at pulling up a specific word, quote, or phrase. For some, this might mean recalling important details of what someone has said or something they read. In other cases, it might mean being able to recite their favorite Shakespearean soliloquy years after reading it.

Passion for Word Games

Their favorite type of games are often word games, puns, or other linguistic puzzles. Wordle, Scrabble, and Words with Friends are just a few that they probably play on a regular basis.

Strong Powers of Persuasion

Because they are so skilled with words, people with this type of intelligence are also skilled at crafting arguments. They are able to utilize their mastery of the written and spoken word to persuade others to see things from their point of view or even change their own perspective.

Examples of Verbal Linguistic Intelligence

Verbal linguistic intelligence isn't just something that people utilize in academic settings—it's an ability that suffuses every aspect of a person's life. For example:

In relationships...

Someone with this type of intelligence is able to communicate effectively. This helps strengthen their connection with other people by conveying information clearly, avoiding miscommunications, and minimizing conflicts.

In the workplace...

Verbal linguistic intelligence often gets a chance to shine. From writing reports to crafting emails to presenting during meetings, language skills often give these individuals an edge that helps them stand out.

In everyday life...

Strong verbal and linguistic abilities often translate to hobbies and activities that center on the written or spoken word. People with this type of intelligence might spend their leisure time reading the latest bestsellers and sharing their thoughts with BookTok (the TikTok community dedicated to reading), or even writing their own original articles, fiction books, non-fiction works, blog posts, or poetry.

Verbal linguistic skills are also important when it comes to picking up new languages. Having a high level of linguistic intelligence can be helpful when it comes to grasping the rules of grammar, acquiring new vocabulary, and picking up on pronunciation patterns.

Developing Verbal Linguistic Intelligence

According to Gardner, people often naturally have high levels of one or more of the nine types of intelligence he described. However, there are also plenty of things you can do to nurture and strengthen your verbal linguistic abilities.

"People can develop and strengthen verbal-linguistic intelligence by reading, writing, participating in speaking engagements, listening to podcasts, and playing word games," Morgan suggests.

She also recommends a few specific strategies that can help people sharpen their verbal linguistic proficiency.

Some specific examples of strategies to build verbal-linguistic intelligence include writing letters to loved ones, listening to interesting podcasts during your commutes or downtime, reading blogs, books, or magazines, and offering to give a presentation at work.

Set Some Reading Goals

One of the best ways to develop your verbal linguistic intelligence is to go back to the basics–read, read, read. Focus on reading widely and consume a diverse range of materials, whether it's books, online articles, poetry, non-fiction books, and essays.

Widening your horizon and exploring different formats, writing styles, and genres can increase your vocabulary and help you gain a greater appreciation for the written word.

Start Writing More

You don't need to become a novelist to be a great writer! Get more writing practice in each day by taking small steps. Start keeping a daily journal where you write down a few thoughts or respond to specific prompts. Consider starting a blog on a subject you enjoy talking about or are interested in learning more about.

Experiment with different types of writing, including using various perspectives to enhance your ability to communicate in different ways and to different audiences.

Build Your Vocabulary

Work on strengthening your knowledge and use of different words and their meanings. Sign up for a word-of-the-day course that delivers a new term to your inbox daily. You can also try vocabulary apps, flashcards, or desktop calendars that feature a new word each day.

Strike Up Conversations

You can also put your budding verbal-linguistic skills to good use in your daily conversations. Participate in conversations with your friends, family, co-workers, and others. It's a great way to practice putting your thoughts and ideas into words in a way that is clear, coherent, and meaningful.

Discussions also allow you to learn more about diverse perspectives and opinions, which can further broaden your skills and knowledge.

Join a Club, Workshop, or Class

There are various informal and formal opportunities to broaden your verbal and linguistic skills. Some ideas to consider include:

- Book clubs , which encourage both reading and discussions

- Writing workshops , where you can work on specific writing skills and get feedback from your peers

- Language and writing classes , where you can receive formal instruction on aspects of writing and language, including grammar, style, and structure

Using Verbal Linguistic Intelligence in the Real World

Whether you have a natural born inclination toward verbal linguistic intelligence or it’s a skill you’re still working to develop, it’s a talent you’re likely to utilize in many different real-world situations. Some professionals who rely heavily on these abilities include:

- Teachers : In academic settings, educators use verbal linguistic skills to communicate information and help students learn effectively. Teachers use these abilities to convey information and explain concepts to students.

- Journalists : Writers use verbal linguistic intelligence to create material for newspapers, websites, magazines, and other media outlets. These abilities allow them to craft compelling stories, essays, reports, and articles that help inform and entertain their readers.

- Customer service : Those who work in customer service roles rely on their verbal linguistic intelligence to help them listen and interact with customers, communicate the right message, and provide useful assistance.

- Attorneys : Legal professionals rely on their verbal linguistic skills during courtroom proceedings, while creating legal documents, and during client negotiations.

- Advertisers and marketers : Professionals who work in areas like copywriting, digital marketing, and advertising rely on their verbal linguistic abilities to create messaging that grabs consumers' attention and interest.

- Politics : Politicians and public officials need strong verbal linguistic talents to help articulate their stances, craft public policy, and engage in political dialogues.

- Mental health professionals : Verbal linguistic abilities are vital for therapists and counselors as they work with clients during sessions and assist their clients in learning to express their own thoughts and feelings effectively.

Enhancing Verbal Linguistic Intelligence in Children

Parents can also take steps to foster strong verbal linguistic skills in their children. Reading to them is one important way to help build this type of intelligence.

Regularly reading aloud to your kids, and letting them read to you, helps expose them to a diverse vocabulary and learn more about important aspects of language and grammar.

"Parents and teachers can promote verbal-linguistic intelligence in children by reading to them, encouraging them to participate in social clubs and activities, and engaging in conversations with them regularly," Morgan suggests.

Some specific strategies that can help kids strengthen these abilities include:

- Let kids explain how to do things : Morgan suggests asking kids to explain or teach something to you. It’s a great way to practice their verbal skills, express themselves, encourage critical thinking skills, and build effective communication skills .

- Have kids introduce themselves to peers : Morgan recommends encouraging kids to introduce themselves to other children. This is great practice and allows kids to practice skills like taking turns, listening actively , and responding appropriately.

- Writing thank you cards : After a birthday or other event, Morgan suggests helping your child write and send thank you cards. This gives kids a chance to express themselves in a thoughtful way and encourages them to work on things like vocabulary and sentence structure.

- Talk to them : Engage your kids in meaningful conversations. Listen to what they have to say and encourage them to listen to what you have to say.

- Try word games : Games like Scrabble and other word association games are a fun way to encourage your child's budding verbal-linguistic abilities.

It's important to remember that verbal linguistic intelligence is just one type of strength that you might have. If you are high in this ability, you probably excel in tasks that require verbal abilities, such as reading, writing, spelling, grammar, and language.

Even if this isn't one of your main strengths, there are things you can do to exercise your verbal skills. Remember, however, that everyone has their own talents. There's no single way to be smart, so it's important to recognize your own abilities and strengths. Examples of other types of intelligence you might possess include naturalistic intelligence , intrapersonal intelligence , and visual spatial intelligence .

Shearer B. Multiple intelligences in teaching and education: Lessons learned from neuroscience . J Intell . 2018;6(3):38. doi:10.3390/jintelligence6030038

Al-Qatawneh SS, Alsalhi NR, Eltahir ME, Siddig OA. The representation of multiple intelligences in an intermediate Arabic-language textbook, and teachers' awareness of them in Jordanian schools . Heliyon . 2021;7(5):e07004. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07004

Şener S, Çokçalışkan A. An investigation between multiple intelligences and learning styles . JETS . 2018;6(2):125. doi:10.11114/jets.v6i2.2643

Scholastic. The different ways your child learns .

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

- Trying to Conceive

- Signs & Symptoms

- Pregnancy Tests

- Fertility Testing

- Fertility Treatment

- Weeks & Trimesters

- Staying Healthy

- Preparing for Baby

- Complications & Concerns

- Pregnancy Loss

- Breastfeeding

- School-Aged Kids

- Raising Kids

- Personal Stories

- Everyday Wellness

- Safety & First Aid

- Immunizations

- Food & Nutrition

- Active Play

- Pregnancy Products

- Nursery & Sleep Products

- Nursing & Feeding Products

- Clothing & Accessories

- Toys & Gifts

- Ovulation Calculator

- Pregnancy Due Date Calculator

- How to Talk About Postpartum Depression

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

Understanding the Verbal Linguistic Learning Style

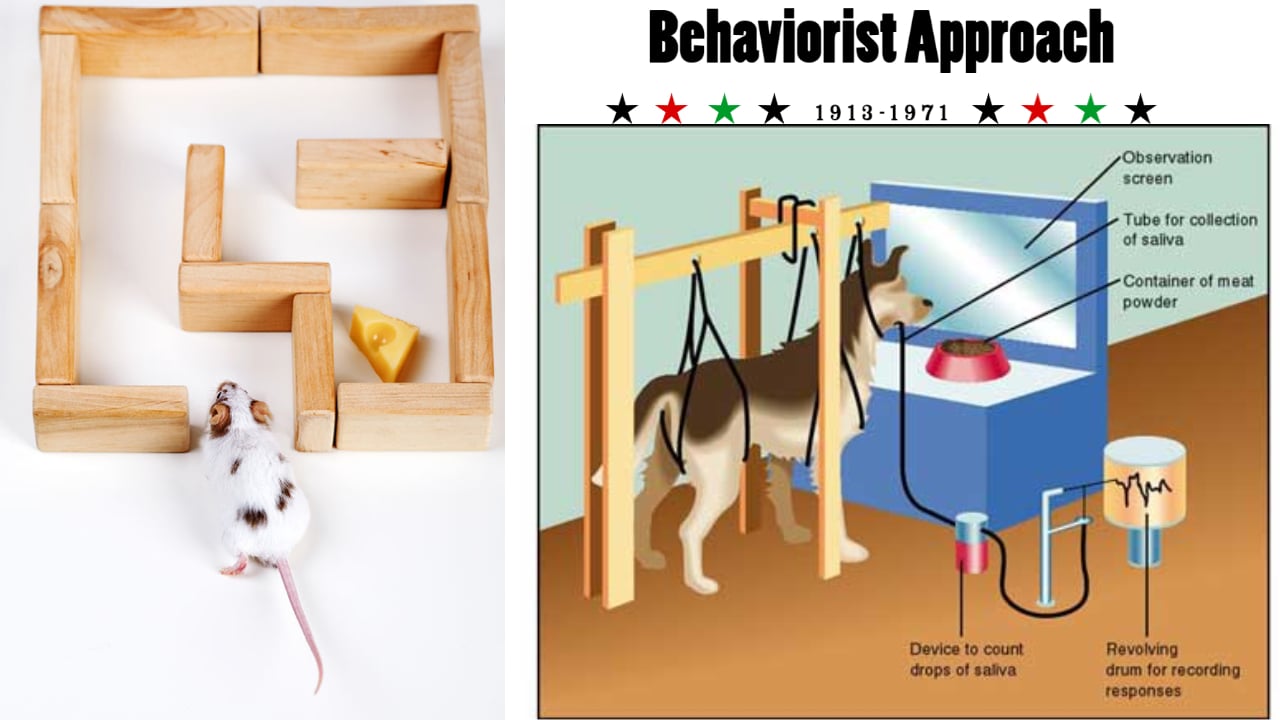

Verbal-linguistic learning style, or intelligence, is one of eight types of learning styles defined in Howard Gardner's theory of multiple intelligences. Gardner's theory, developed during the 1960s, helps teachers, trainers, and employers adjust their teaching styles to fit the needs of different learners.

Verbal-linguistic learning style refers to a person's ability to reason, solve problems, and learn using language. Because so much of the school curriculum is taught verbally, verbal-linguistic learners tend to do well in school. They may also excel in typical university settings. It is important to bear in mind, however, that verbal-linguistic ability is not a synonym for intelligence.

Characteristics

Verbal-linguistically talented people flourish in school activities such as reading and writing. They express themselves well and are usually good listeners with a well-developed memory for the material they've read and strong recall of spoken information.

Language fascinates people with verbal-linguistic learning styles, and they enjoy learning new words and exploring ways to creatively use language, as in poetry. They may enjoy learning new languages, memorizing tongue twisters, playing word games, and reading.

Verbal-linguistic learners are often good at tests that build on the ability to quickly and accurately respond to spoken or written instructions. This makes it easier for such learners to excel on standardized exams, IQ tests, and quizzes. It's important to remember, however, that language-based tests measure only one form of intelligence.

How These Learners Learn Best

People with verbal-linguistic learning styles learn best when taught using spoken or written materials. They prefer activities that are based on language reasoning rather than abstract visual information. Math word problems are more appealing to verbal-linguistic learners than solving equations. They usually enjoy written projects, speech and drama classes, debate, language classes, and journalism.

Verbal-linguistic learners may have a harder time with hand-eye coordination or visual-spatial tasks. They may also find it difficult to interpret a visual presentation of information. For example, it may be harder for verbal-linguistic learners to read a chart, interpret a graph, or understand a mind-map.

Verbal lessons

Reading materials

Math story problems

Written projects

Presentation projects

Abstract visuals such as charts or graphs

Pure math problems

Hands-on projects with minimal verbal or written instructions

Projects relying on hand-eye coordination

Recognize Verbal-Linguistic Learners

Verbal-linguistic learners enjoy language and are thus likely to enjoy games that involve wordplay. They are often attracted to puns, language-based jokes, and games like Boggle or Scrabble. They tend to be voracious readers and, in many cases, prolific writers.

Some verbal-linguistic learners can become so intrigued by proper language use that they may correct others' grammatical mistakes or point out the misuse of words or language. Some verbal-linguistic learners find it easy to learn other languages, though they may not be able to fully explain grammatical rules.

Career Choices

Verbal-linguistic learning style students with high levels of verbal intelligence often seek careers such as teaching English, language arts, drama, and debate at k-12 or postsecondary institutions. They frequently choose careers such as professional writer, news correspondent, poet, creative writer, attorney, publicist, advertising agent, psychologist, speech pathologist, and editorial positions.

Sener S, Cokcaliskan A. An investigation between multiple intelligences and learning styles . J Educ Train Stud . 2018;6(2). doi:10.11114/jets.v6i2.2643

Scholastic. Adapting instruction to multiple intelligences .

Scholastic. Checklist: Learning activities that connect with multiple intelligences .

By Ann Logsdon Ann Logsdon is a school psychologist specializing in helping parents and teachers support students with a range of educational and developmental disabilities.

Howard Gardner’s Theory of Multiple Intelligences

Michele Marenus

Research Scientist

B.A., Psychology, Ed.M., Harvard Graduate School of Education

Michele Marenus is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Michigan with over seven years of experience in psychology research.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Howard Gardner first proposed the theory of multiple intelligences in his 1983 book “Frames of Mind”, where he broadens the definition of intelligence and outlines several distinct types of intellectual competencies.

Gardner developed a series of eight inclusion criteria while evaluating each “candidate” intelligence that was based on a variety of scientific disciplines.

He writes that we may all have these intelligences, but our profile of these intelligences may differ individually based on genetics or experience.

Gardner defines intelligence as a “biopsychological potential to process information that can be activated in a cultural setting to solve problems or create products that are of value in a culture” (Gardner, 2000, p.28).

What is Multiple Intelligences Theory?

- Howard Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences proposes that people are not born with all of the intelligence they will ever have.

- This theory challenged the traditional notion that there is one single type of intelligence, sometimes known as “g” for general intelligence, that only focuses on cognitive abilities.

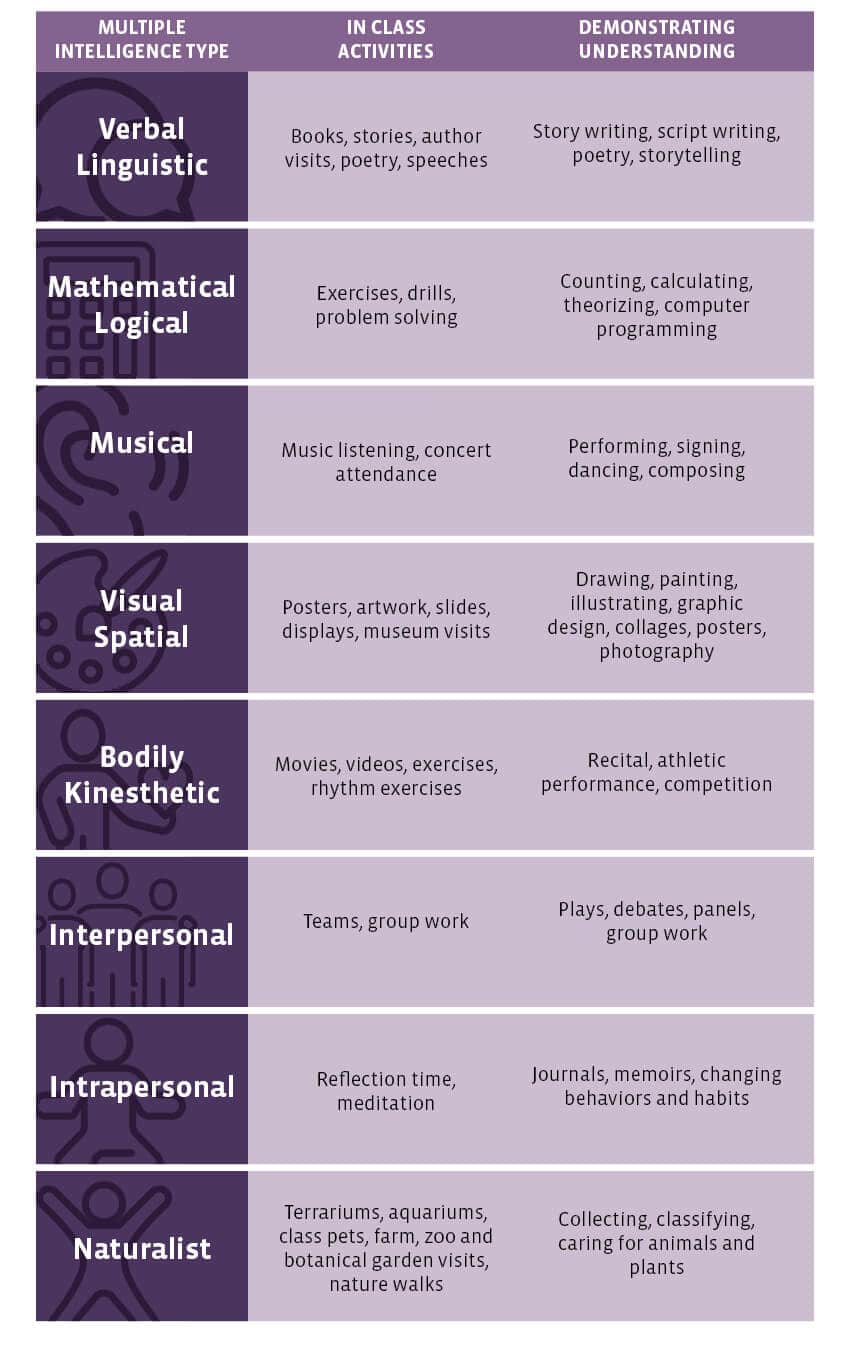

- To broaden this notion of intelligence, Gardner introduced eight different types of intelligences consisting of: Linguistic, Logical/Mathematical, Spatial, Bodily-Kinesthetic, Musical, Interpersonal, Intrapersonal, and Naturalist.

- Gardner notes that the linguistic and logical-mathematical modalities are most typed valued in school and society.

- Gardner also suggests that there may other “candidate” intelligences—such as spiritual intelligence, existential intelligence, and moral intelligence—but does not believe these meet his original inclusion criteria. (Gardner, 2011).

Linguistic Intelligence (word smart)

Linguistic Intelligence is a part of Howard Gardner’s multiple intelligence theory that deals with sensitivity to the spoken and written language, ability to learn languages, and capacity to use language to accomplish certain goals.

Linguistic intelligence involves the ability to use language masterfully to express oneself rhetorically or poetically. It includes the ability to manipulate syntax, structure, semantics, and phonology of language.

People with linguistic intelligence, such as William Shakespeare and Oprah Winfrey, have the ability to analyze information and create products involving oral and written language, such as speeches, books, and memos.

Potential Career Choices

Careers you could dominate with your linguistic intelligence:

Lawyer Speaker / Host Author Journalist Curator

Logical-Mathematical Intelligence (number/reasoning smart)

Logical-mathematical intelligence refers to the capacity to analyze problems logically, carry out mathematical operations, and investigate issues scientifically.

Logical-mathematical intelligence involves the ability to use logic, abstractions, reasoning, and critical thinking to solve problems. It includes the capacity to understand the underlying principles of some kind of causal system.

People with logical-mathematical intelligence, such as Albert Einstein and Bill Gates, have an ability to develop equations and proofs, make calculations, and solve abstract problems.

Careers you could dominate with your logical-mathematical intelligence:

Mathematician Accountant Statistician Scientist Computer Analyst

Spatial Intelligence (picture smart)

Spatial intelligence involves the ability to perceive the visual-spatial world accurately. It includes the ability to transform, modify, or manipulate visual information. People with high spatial intelligence are good at visualization, drawing, sense of direction, puzzle building, and reading maps.

Spatial intelligence features the potential to recognize and manipulate the patterns of wide space (those used, for instance, by navigators and pilots) as well as the patterns of more confined areas, such as those of importance to sculptors, surgeons, chess players, graphic artists, or architects.

People with spatial intelligence, such as Frank Lloyd Wright and Amelia Earhart, have the ability to recognize and manipulate large-scale and fine-grained spatial images.

Careers you could dominate with your spatial intelligence:

Pilot Surgeon Architect Graphic Artist Interior Decorator

Bodily-Kinesthetic Intelligence (body smart)

Bodily-kinesthetic intelligence is the potential of using one’s whole body or parts of the body (like the hand or the mouth) to solve problems or to fashion products.

Bodily-kinesthetic intelligence involves using the body with finesse, grace, and skill. It includes physical coordination, balance, dexterity, strength, and flexibility. People with high bodily-kinesthetic intelligence are good at sports, dance, acting, and physical crafts.

People with bodily-kinesthetic intelligence, such as Michael Jordan and Simone Biles, can use one’s own body to create products, perform skills, or solve problems through mind–body union.

Careers you could dominate with your bodily-kinesthetic intelligence:

Dancer Athlete Surgeon Mechanic Carpenter Physical Therapist

Musical Intelligence (music smart)

Musical intelligence refers to the skill in the performance, composition, and appreciation of musical patterns.

Musical intelligence involves the ability to perceive, discriminate, create, and express musical forms. It includes sensitivity to rhythm, pitch, melody, and tone color. People with high musical intelligence are good at singing, playing instruments, and composing music.

People with musical intelligence, such as Beethoven and Ed Sheeran, have the ability to recognize and create musical pitch, rhythm, timbre, and tone.

Careers you could dominate with your musical intelligence:

Singer Composer DJ Musician

Interpersonal Intelligence (people smart)

Interpersonal intelligence is the capacity to understand the intentions, motivations, and desires of other people and, consequently, to work effectively with others.

Interpersonal intelligence involves the ability to understand and interact effectively with others. It includes sensitivity to other people’s moods, temperaments, motivations, and desires. People with high interpersonal intelligence communicate well and can build rapport.

People with interpersonal intelligence, such as Mahatma Gandhi and Mother Teresa, have the ability to recognize and understand other people’s moods, desires, motivations, and intentions.

Careers you could dominate with your interpersonal intelligence:

Teacher Psychologist Manager Salespeople Public Relations

Intrapersonal Intelligence (self-smart)

Intrapersonal intelligence is the capacity to understand oneself, to have an effective working model of oneself, including one’s desires, fears, and capacities—and to use such information effectively in regulating one’s own life.

It includes self-awareness, personal cognizance, and the ability to refine, analyze, and articulate one’s emotional life.

People with intrapersonal intelligence, such as Aristotle and Maya Angelou, have the ability to recognize and understand his or her own moods, desires, motivations, and intentions.

This type of intelligence can help a person understand which life goals are important and how to achieve them.

Careers you could dominate with your intrapersonal intelligence:

Therapist Psychologist Counselor Entrepreneur Clergy

Naturalist intelligence (nature smart)

Naturalist intelligence involves the ability to recognize, categorize, and draw upon patterns in the natural environment. It includes sensitivity to the flora, fauna, and phenomena in nature. People with high naturalist intelligence are good at classifying natural forms.

Naturalistic intelligence involves expertise in recognizing and classifying the numerous species—the flora and fauna—of his or her environment.

People with naturalistic intelligence, such as Charles Darwin and Jane Goddall, have the ability to identify and distinguish among different types of plants, animals, and weather formations that are found in the natural world.

Careers you could dominate with your naturalist intelligence:

Botanist Biologist Astronomer Meteorologist Geologist

Critical Evaluation

Most resistance to multiple intelligences theory has come from cognitive psychologists and psychometricians. Cognitive psychologists such as Waterhouse (2006) claimed that there is no empirical evidence to the validity of the theory of multiple intelligences.

Psychometricians, or psychologists involved in testing, argue that intelligence tests support the concept for a single general intelligence, “g”, rather than the eight distinct competencies (Gottfredson, 2004). Other researchers argue that Gardner’s intelligences comes second or third to the “g” factor (Visser, Ashton, & Vernon, 2006).

Some responses to this criticism include that the multiple intelligences theory doesn’t dispute the existence of the “g” factor; it proposes that it is equal along with the other intelligences. Many critics overlook the inclusion criteria Gardner set forth.

These criteria are strongly supported by empirical evidence in psychology, biology, neuroscience, among others. Gardner admits that traditional psychologists were valid in criticizing the lack of operational definitions for the intelligences, that is, to figure out how to measure and test the various competencies (Davis et al., 2011).

Gardner was surprised to find that Multiple Intelligences theory has been used most widely in educational contexts. He developed this theory to challenge academic psychologists, and therefore, he did not present many educational suggestions. For this reason, teachers and educators were able to take the theory and apply it as they saw fit.

As it gained popularity in this field, Gardner has maintained that practitioners should determine the theory’s best use in classrooms. He has often declined opportunities to aid in curriculum development that uses multiple intelligences theory, opting to only provide feedback at most (Gardner, 2011).

Most of the criticism has come from those removed from the classroom, such as journalists and academics. Educators are not typically tied to the same standard of evidence and are less concerned with abstract inconsistencies, which has given them the freedom to apply it with their students and let the results speak for itself (Armstrong, 2019).

Shearer (2020) provides extensive empirical evidence from neuroscience research supporting MI theory.

Shearer reviewed evidence from over 500 functional neuroimaging studies that associate patterns of brain activation with the cognitive components of each intelligence.

The visual network was associated with the visual-spatial intelligence, somatomotor networks with kinesthetic intelligence, fronto-parietal networks with logical and general intelligence, auditory networks with musical intelligence, and default mode networks with intra- and interpersonal intelligences. The coherence and distinctiveness of these networks provides robust support for the neural validity of MI theory

He concludes that human intelligence is best characterized as being multiple rather than singular, with each person possessing unique neural potentials aligned with specific intelligences.

Implications for Learning

The most important educational implications of the theory of multiple intelligences can be summed up through individuation and pluralization. Individuation posits that because each person differs from other another there is no logical reason to teach and assess students identically.

Individualized education has typically been reserved for the wealthy and others who could afford to hire tutors to address individual student’s needs.

Technology has now made it possible for more people to access a variety of teachings and assessments depending on their needs. Pluralization, the idea that topics and skills should be taught in more than one way, activates an individual’s multiple intelligences.

Presenting a variety of activities and approaches to learning helps reach all students and encourages them to be able to think about the subjects from various perspectives, deepening their knowledge of that topic (Gardner, 2011b).

A common misconception about the theory of multiple intelligences is that it is synonymous with learning styles. Gardner states that learning styles refer to the way an individual is most comfortable approaching a range of tasks and materials.

Multiple intelligences theory states that everyone has all eight intelligences at varying degrees of proficiency and an individual’s learning style is unrelated to the areas in which they are the most intelligent.

For example, someone with linguistic intelligence may not necessarily learn best through writing and reading. Classifying students by their learning styles or intelligences alone may limit their potential for learning.

Research shows that students are more engaged and learn best when they are given various ways to demonstrate their knowledge and skills, which also helps teachers more accurately assess student learning (Darling-Hammond, 2010).

Therapeutic Benefits of Incorporating Multiple Intelligences Within Therapy

Pearson et al. (2015) investigated the experiences of 8 counselors who introduced multiple intelligences (MI) theory and activities into therapy sessions with adult clients. The counselors participated in a 1-day MI training intervention and were interviewed 3 months later about their experiences using MI in practice.

The major themes that emerged from qualitative analysis of the interviews were:

- MI helped enhance therapeutic alliances. Counselors felt incorporating MI strengthened their connections with clients, increased counselor and client comfort, and reduced client suspicion/resistance.

- MI led to more effective professional work. Counselors felt MI provided more tools and flexibility in responding to clients. This matches findings from education research on the benefits of MI.

- Clients responded positively to identifying strengths through MI. The MI survey helped clients recognize talents/abilities, which counselors saw as identity-building. This aligns with the literature on strength-based approaches.

- Clients appreciated the MI preference survey. It provided conversation starters, increased self-reflection, and was sometimes a catalyst for using music therapeutically.

- Counselors felt comfortable with MI. They experienced increased confidence and professional comfort. Counselor confidence contributes to alliance building (Ackerman & Hilsenroth, 2003).

- Music use stood out as impactful. In-session and extratherapeutic music use improved client well-being after identifying musicality through the MI survey. This matches the established benefits of music therapy (Koelsch, 2009).

- MI training opened up therapeutic possibilities. Counselors valued the experiential MI training. MI appeared to expand their skills and activities.

The authors conclude that MI may enhance alliances, effectiveness, and counselor confidence. They recommend further research on long-term impacts and optimal training approaches. Counselor education could teach MI theory, assessment, and tailored interventions.

Frequently Asked Questions

How can understanding the theory of multiple intelligences contribute to self-awareness and personal growth.

Understanding the theory of multiple intelligences can contribute to self-awareness and personal growth by providing a framework for recognizing and valuing different strengths and abilities.

By identifying their own unique mix of intelligences, individuals can gain a greater understanding of their own strengths and limitations and develop a more well-rounded sense of self.

Additionally, recognizing and valuing the diverse strengths and abilities of others can promote empathy , respect, and cooperation in personal and professional relationships.

Why is multiple intelligence theory important?

Understanding multiple intelligences is important because it helps individuals recognize that intelligence is not just about academic achievement or IQ scores, but also includes a range of different abilities and strengths.

By identifying their own unique mix of intelligences, individuals can develop a greater sense of self-awareness and self-esteem, as well as pursue career paths that align with their strengths and interests.

Additionally, understanding multiple intelligences can promote more inclusive and personalized approaches to education and learning that recognize and value the diverse strengths and abilities of all students.

Are certain types of intelligence more valued or prioritized in society than others?

Yes, certain types of intelligence, such as linguistic and logical-mathematical intelligence, are often prioritized in traditional education and assessment methods.

However, the theory of multiple intelligences challenges this narrow definition of intelligence and recognizes the value of a diverse range of strengths and abilities.

By promoting a more inclusive and personalized approach to education and learning, the theory of multiple intelligences can help individuals recognize and develop their unique mix of intelligences, regardless of whether they align with traditional societal expectations.

What is the difference between multiple intelligences and learning styles?

The theory of multiple intelligences proposes that individuals possess a range of different types of intelligence. In contrast, learning styles refer to an individual’s preferred way of processing information, such as visual, auditory, or kinesthetic.

While both theories emphasize the importance of recognizing and valuing individual differences in learning and development, multiple intelligence theory proposes a broader and more diverse range of intelligences beyond traditional academic abilities, while learning styles are focused on preferences for processing information.

Armstrong, T. (2009). Multiple intelligences in the classroom . Ascd.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2010). Performance Counts: Assessment Systems That Support High-Quality Learning . Council of Chief State School Officers .

Davis, K., Christodoulou, J., Seider, S., & Gardner, H. E. (2011). The theory of multiple intelligences. Davis, K., Christodoulou, J., Seider, S., & Gardner, H.(2011). The theory of multiple intelligences . In RJ Sternberg & SB Kaufman (Eds.), Cambridge Handbook of Intelligence , 485-503.

Edutopia. (2013, March 8). Multiple Intelligences: What Does the Research Say? https://www.edutopia.org/multiple-intelligences-research

Gardner, H. E. (2000). Intelligence reframed: Multiple intelligences for the 21st century . Hachette UK.

Gardner, H. (2011a). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences . Hachette Uk.

Gardner, H. (2011b). The theory of multiple intelligences: As psychology, as education, as social science. Address delivered at José Cela University on October, 29, 2011.

Gottfredson, L. S. (2004). Schools and the g factor . The Wilson Quarterly (1976-), 28 (3), 35-45.

Pearson, M., O’Brien, P., & Bulsara, C. (2015). A multiple intelligences approach to counseling: Enhancing alliances with a focus on strengths. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 25 (2), 128–142

Shearer, C. B. (2020). A resting state functional connectivity analysis of human intelligence: Broad theoretical and practical implications for multiple intelligences theory. Psychology & Neuroscience, 13 (2), 127–148.

Visser, B. A., Ashton, M. C., & Vernon, P. A. (2006). Beyond g: Putting multiple intelligences theory to the test . Intelligence, 34 (5), 487-502.

Waterhouse, L. (2006). Inadequate evidence for multiple intelligences, Mozart effect, and emotional intelligence theories . Educational Psychologist, 41 (4), 247-255.

Further Information

- Multiple Intelligences Criticisms

- The Theory of Multiple Intelligences

- Multiple Intelligences FAQ

- “In a Nutshell,” the first chapter of Multiple Intelligences: New Horizons

- Multiple Intelligences After Twenty Years”

- Intelligence: Definition, Theories and Testing

- Fluid vs Crystallized Intelligence

Related Articles

Soft Determinism In Psychology

Branches of Psychology

Social Action Theory (Weber): Definition & Examples

Adult Attachment , Personality , Psychology , Relationships

Attachment Styles and How They Affect Adult Relationships

Learning Theories , Psychology

Behaviorism In Psychology

Personality , Psychology

Big Five Personality Traits: The 5-Factor Model of Personality

Multiple Intelligences Theory—Howard Gardner

- First Online: 09 September 2020

Cite this chapter

- Bulent Cavas 3 &

- Pinar Cavas 4

Part of the book series: Springer Texts in Education ((SPTE))

20k Accesses

8 Citations

Multiple intelligences theory (MI) developed by Howard Gardner, an American psychologist, in late 1970s and early 1980s, asserts that each individual has different learning areas. In his book, Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences published in 1983, Gardner argued that individuals have eight different intelligence areas and added one more intelligence area in the later years. Howard Gardner named these nine intelligence areas as “musical–rhythmic”, “visual–spatial”, “verbal–linguistic”, “logical–mathematical”, “bodily–kinesthetic”, “interpersonal”, “intrapersonal”, “naturalistic”, and “existential intelligence. Gardner indicates that these intelligences are constructed through the participation of individuals in culturally valued activities, and these activities help individuals to develop unique patterns in their mind. Multiple intelligences theory states that there are many ways to be intelligent not only just two ways measured by IQ tests. Appearance of multiple intelligences theory has provided significant practices and studies particularly in the field of education to be carried out and has changed educators’ views toward the concepts of learning and intelligence. This chapter discusses the historical and theoretical dimensions of multiple intelligences as well as the research conducted on the theory. We have also provided the advantages and disadvantages of MI implementation in science education.

An intelligence is the ability to solve problems, or to create products, that are valued within one or more cultural settings. Howard Gardner — Frames of Mind ( 1983 ).

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Abdi, A., Laei, S., & Ahmadyan, H. (2013). The effect of teaching strategy based on multiple intelligences on students’ academic achievement in science course. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 1 (4), 281–284.

Google Scholar

Blumenfield-Jones, D. (2009). Bodily-kinesthetic intelligence and dance education: Critique, revision, and potentials for the democratic idea. Journal of Aesthetic Education, 43 (1), 59–76.

Article Google Scholar

Campbell, L., & Campbell, B. (1999). Multiple intelligences and student achievement: Success stories from six schools . Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. Retrieved from https://goo.gl/Y7Cz3w .

Crowther, G. J., Williamson, J. L., Buckland, H. T., & Cunningham, S. L. (2013). Making material more memorable with music. American Biology Teacher, 75, 713–714. https://doi.org/10.1525/abt.2013.75.9.16 .

Davis, K., Christodoulou, J. A., Seider, S., & Gardner, H. (2011). The theory of multiple intelligences. In R. J. Sternberg & S. B. Kaufman (Eds.), Cambridge handbook of intelligence (pp. 485–503). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences . New York: Basic Books.

Gardner, H. (1991). The unschooled mind: How children think and how schools should teach. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Gardner, H. (1993). Multiple intelligences: The theory in practice . New York, NY: Basic Books.

Gardner, H. (1999a). Intelligence reframed: Multiple intelligences for the 21st century . New York, NY: Basic Books.

Gardner, H. (1999b). The disciplined mind: What all students should understand . New York: Simon & Schuster.

Gardner, H. (2006). Multiple intelligences: New horizon . New York, NY: Basic Books.

Gardner, H. (2011). The unschooled mind: How children think and how schools should teach . United Kingdom: Hachette.

Gardner, H., & Walters, J. (1993). Questions and answers about multiple intelligences theory. Multiple intelligences: The theory in practice (pp. 35–48). New York: Basic Books.

Goodnough, K. (2001). Multiple intelligences theory: A framework for personalizing science curricula. School Science and Mathematics., 101 (4), 180–193.

Hoerr, R. T. (2000). Becoming a multiple intelligences school. Retrieved from http://www.ascd.org/publications/books/100006.aspx .

Hom, E. (2014). What is STEM education? Retrieved from https://www.livescience.com/43296-what-is-stem-education.html .

Junchun, W. (2015). To explore the relationship of temporal spatial reasoning between music and mathematics by an inventory based on the multiple intelligence theory. Education and Psychological Research, 38 (3). https://doi.org/10.3966/102498852015093803002 .

Klein, P. (1997). Multiplying the problems of intelligence by eight: A critique of Gardner’s theory. Canadian Journal of Education, 22, 377–394.

Lai, H. Y., & Yap, S. L. (2016). Application of multiple intelligence theory in the assessment for learning. In S. Tang & L. Logonnathan (Eds.), Assessment for learning within and beyond the classroom (pp. 427–436). Singapore: Springer.

Martin, M. R., Bishop, J., Ciotto, C., & Gagnon, A. (2014). Teaching the whole child: Using the multiple intelligence theory and interdisciplinary teaching in physical education. In The chronicle of kinesiology in higher education ( Special Edition , pp. 25–29).

Martín, J. S., Gragera, G. J. A., Dávila-Acedo, M., & Mellado, V. (2017). What do K-12 students feel when dealing with technology and engineering issues? Gardner’s multiple intelligence theory implications in technology lessons for motivating engineering vocations at Spanish secondary school. European Journal of Engineering Education, 42 (6), 1330–1343.

Martin, M., & McKenzie, M. (2013). Sport education and multiple intelligences: A path to student success. Strategies, 26 (4), 31–34.

Morgan, H. (1996). An analysis of Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligence. Roeper Review, 18, 263–269.

Ozdermir, P., Güneysu, S., & Tekkaya, C. (2006). Enhancing learning through multiple intelligences. Journal of Biological Education, 40 (2), 74–78.

Richards, D. (2016). The integration of the multiple intelligence theory into the early childhood curriculum. American Journal of Educational Research, 4 (15), 1096–1099. Retrieved from http://pubs.sciepub.com/education/4/15/7 .

Schulkind, M. D. (2009). Is memory for music special? Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1169, 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04546.x .

Schwert, A. (2004). Using the theory of multiple intelligences to enhance science education . Unpublished Master’s Thesis. The University of Toledo, USA. Retrieved from http://utdr.utoledo.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1487&context=graduate-projects .

Suprapto, N., Liu, W. Y., & Ku, C. K. (2017). The implementation of multiple intelligence in (science) classroom: From empirical into critical. Pedagogika, 126 (2), 214–227.

Viadero, D. (2003). Staying power. Education Week, 22 (39), 24.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Buca Faculty of Education, Dokuz Eylül University, Izmir, Turkey

Bulent Cavas

Faculty of Education, Ege University, Izmir, Turkey

Pinar Cavas

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Bulent Cavas .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Science Teachers Association of Nigeria, Abuja, Nigeria

University of Texas at Tyler, Tyler, TX, USA

Teresa J. Kennedy

Recommended Resources

Gardner, H. (1999a). Intelligence reframed: Multiple intelligences for the 21st century . New York: Basic Books.

Gardner, H. (2004). Frequently asked questions—Multiple intelligences and related educational topics. Retrieved March 9, 2018, from http://multipleintelligencesoasis.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/faq.pdf .

Gardner, H. (2006). Multiple intelligences: New Horizon . New York: Basic Books.

Gardner, H. (2011). The unschooled mind: How children think and how schools should teach . UK: Hachette.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cavas, B., Cavas, P. (2020). Multiple Intelligences Theory—Howard Gardner. In: Akpan, B., Kennedy, T.J. (eds) Science Education in Theory and Practice. Springer Texts in Education. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-43620-9_27

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-43620-9_27

Published : 09 September 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-43619-3

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-43620-9

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Linguistic Intelligence

The Ability to Understand and Use Spoken and Written Language

Riou/Digital Vision/Getty Images

- Learning Styles & Skills

- Homework Tips

- Study Methods

- Time Management

- Private School

- College Admissions

- College Life

- Graduate School

- Business School

- Distance Learning

- M.Ed., Curriculum and Instruction, University of Florida

- B.A., History, University of Florida

Linguistic intelligence, one of Howard Gardner's eight multiple intelligences , involves the ability to understand and use spoken and written language. This can include expressing yourself effectively through speech or the written word as well as showing a facility for learning foreign tongues. Writers, poets, lawyers, and speakers are among those that Gardner sees as having high linguistic intelligence.

Gardner, a professor in the Harvard University Education Department, uses T.S. Eliot as an example of someone with high linguistic intelligence. "At the age of ten, T.S. Eliot created a magazine called 'Fireside,' of which he was the sole contributor," Gardner writes in his 2006 book, "Multiple Intelligences: New Horizons in Theory and Practice." "In a three-day period during his winter vacation, he created eight complete issues. Each one included poems, adventure stories, a gossip column, and humor."

Much More Than What Can Be Measured on a Test

It's interesting that Gardner listed linguistic intelligence as the very first intelligence in his original book on the subject, "Frames of Mind: The Theory of MultipleIntelligences," published in 1983. This is one of the two intelligences -- the other being logical-mathematical intelligence -- that most closely resemble the skills measured by standard IQ tests. But Gardner argues that linguistic intelligence is much more than what can be measured on a test.

Famous People With High Linguistic Intelligence

- William Shakespeare : Arguably history's greatest playwright, Shakespeare wrote plays that have enthralled audiences for more than four centuries. He coined or popularized many of the words and phrases we still use today.

- Robert Frost : A poet laureate of Vermont, Frost read his well-known poem "The Gift Outright" at the inauguration of President John F. Kennedy on Jan. 20, 1961, according to Wikipedia. Frost wrote classic poems, such as " The Road Not Taken ," which are still widely read and admired today.

- J.K. Rowling : This contemporary English author used the power of language and imagination to create a mythical, magical world of Harry Potter, which has captivated millions of readers and moviegoers over the years.

Ways to Enhance and Encourage It

Teachers can help their students enhance and strengthen their linguistic intelligence by:

- writing in a journal

- writing a group story

- learning a few new words each week

- creating a magazine or website devoted to something that interests them

- writing letters to family, friends or penpals

- playing word games like crosswords or parts-of-speech bingo

- reading books, magazines, newspapers and even jokes

Gardner gives some advice in this area. He talks, in "Frames of Mind," about Jean-Paul Sartre, a famous French philosopher, and novelist who was "extremely precocious" as a young child but "so skilled at mimicking adults, including their style and register of talk, that by age five he could enchant audiences with his linguistic fluency." By age 9, Sartre was writing and expressing himself -- developing his linguistic intelligence. In the same way, as a teacher, you can enhance your students' linguistic intelligence by giving them opportunities to express themselves creatively both verbally and through the written word.

- Questions for Each Level of Bloom's Taxonomy

- Spatial Intelligence

- Teaching Students With Existential Intelligence

- How to Use Multiple Intelligences to Study for a Test

- Teaching Students Who Have a Naturalist Intelligence

- Teaching Students Who Have Musical Intelligence

- Understanding the Meaning of Bodily-Kinesthetic Intelligence

- The Best Examples of Intrapersonal Intelligence

- How to Analyze Problems Using Logical Mathematical Intelligence

- Teaching Students Identified with Interpersonal Intelligence

- Understanding Howard Gardner's Theory of Multiple Intelligence

- Multiple Intelligence Activities

- What's Your Learning Language?

- Smart Study Strategies for Different Intelligence Types

- Multiple Intelligences in the ESL Classroom

- Why Is Writing More Difficult Than Speaking?

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Logical-Mathematical Intelligence and Verbal-Linguistic Intelligence: A study on Multiple Intelligences

Related Papers

Ebrahim Khodadady

This study explored the relationship between logical-mathematical intelligence and English language proficiency. To this end, out of the eight sections comprising the Multiple Intelligences Developmental Assessment Scales designed by Shearer (1994), its Persian logical-mathematical scale (LMS) was administered to two hundred and five participants who took the Test of English as a Foreign Language held and called MSRT by the Ministry of Science, Research and Technology in Iran. When the data on the LMS were subjected to Principal Axis Factoring and the extracted factors were rotated via Varimax with Kaiser Normalization, sixteen out of seventeen indicators comprising the scale loaded on six latent variables (LVs) having the initial eigenvalues of one and higher, i.e., Math Skill, Problem Solving, Natural Curiosity, Number Memory, Math Application, and System Invention. When the LMS and its LVs were correlated with the listening, structure, and reading subtests of the MSRT, the scale and its Math Application LV correlated significantly but negatively with the reading subtest. The results are discussed and suggestions are made for future research.

Aan Subhan Pamungkas

The process of solving problems carried out by students in stages, namely understanding problems, planning solutions, carrying out solutions and checking again. Solving student problems varies according to the basic characteristics of students' interests, talents and potential. Learning will be more optimal if it is adjusted to the intelligence possessed by students. The goal is that teachers can facilitate learning according to the intelligence possessed by students, so the teacher must know the intelligence possessed by students. This research is a qualitative study using two subjects, namely the subject of linguistics and the subject of mathematical logic. The results showed that at the problem-understanding stage, SLM completed using formulas, completed according to plan and checked by recalculating. SL uses more trial-and-error reasoning, understanding information by reading sentences quickly as well as checking again.

Mohsen Shahrokhi

Wajiha kanwal

The present study was correctional in nature and based on quantitative research approach. It was designed to determine Interrelation of Multiple Intelligences and their correlation with linguistic intelligence as perceived by college students. The population of the study was comprised of all the students of intermediate level studying in Islamabad Model Colleges. The simple random sampling technique was employed to select a representative sample for the study. The sample consisted of 1000 students, Questionnaire was developed on the basis of Howard Gardner's Multiple intelligences Model. The validity of the questionnaire was ensured through expert opinions, whereas, its‘ reliability was measured through pilot testing on 100 students. Researcher used SPSS advanced version to analyze the quantitative data. Mean, Standard Deviation, and Pearson Coefficient Correlation were used to analyze the data. The results of the study showed that moderate inter-correlation exists between verba...

Journal of Educational and Social Research

rommel alali

This study discussed the level of logical mathematical intelligence of pre-service female mathematics teachers. The problem arises in adopting traditional curricula for teaching mathematics, which leads to low student achievement. The study objectives to measure the students' level of logical mathematical intelligence, and find out the level of students’ achievement, and measuring the level of intelligence impact on the academic achievement. The study adopted the descriptive-analytical approach. The study population consisted of (45) pre-service female math teachers. A comprehensive sample was chosen. A questionnaire was used according to the (Likert) five-point scale, taking advantage of the MIDAS scale of multiple intelligences, which consisted of (17) statements, then the researchers developed the questionnaire up to (25) statements. The validity and reliability of the questionnaire were confirmed. The findings revealed that: The general average of the logical-mathematical in...

ENGLISH FRANCA : Academic Journal of English Language and Education

kurnia saputri

The Identification of Multiple Intelligence in relation to English Achievement of the sixth graders of SD N 32 Palembang. Based on the data analysis, there were five major findings: First, linguistic, logical, spatial, musical, and interpersonal intelligences were types of intelligence of the sixth graders. Second, most of the students dominantly have interpersonal intelligence. Third, based on the calculation of z scores (standard scores), Logical-Ma thematical intelligence was the type of intelligence that had better English achievement because this type had the positive scores higher than the negative scores. Fourth, the variance of population was homogeneous. Fifth, the mean value of population was homogeneous and correlated each other.

SMART M O V E S J O U R N A L IJELLH

Abstract The theory of Multiple Intelligence (MI) suggests that learners have different strengths, learning styles and even learning potential contrary to the belief that only students with strong linguistic, mathematical and spacial abilities are accepted and recognized in the society. Once the teachers recognize the different intelligences possessed by their students, they can design different exercises to enhance the language skills of the students. This article focuses on ways of enhancing the English Language skills among the students, using Gardner’s Multiple Intelligence Theory. For the purpose of the study, Gardner’s MI questionnaire was administered to 150 school students. A pre-test, intervention programme, and a post - test were conducted to make the study more authentic. Key words: Multiple intelligence, questionnaire, pre-test, intervention programme, post-test

Proceedings of the 3rd Borobudur International Symposium on Humanities and Social Science 2021 (BIS-HSS 2021)

galih istiningsih

International Journal of Asian Social Science

Fatemeh Hemmati

RELATED PAPERS

Századok 157 (2023) 115–154.

Gulyás László Szabolcs

PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases

Biochemical Education

Juan C Benech

Journal of Quantitative Spectroscopy and Radiative Transfer

Cristina Yubero

Journal of Clinical Neuroscience

Robert White

哪里卖俄亥俄大学毕业证 ohio毕业证学历证书学费单原版一模一样

Κλίβανος, θεωρητικό φιλολογικό όργανο της Υπερρεαλιστικής Ομάδας Θεσσαλονίκης, τόμος ΙΙ

Ιοanna Lioutsia

买西悉尼大学毕业证书成绩单 办理澳洲UWS文凭学位证书

Journal of the Optical Society of America

Jakob Stamnes

Saule Chalbasova

Journal of Equine Veterinary Science

Emmanuelly Santos

Lynn Jackson

Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter

Jorge O. Tocho

Loreta Gustainienė

ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces

David Pepyne

AJHSSR Journal

Genomics, Proteomics & Bioinformatics

Zhang Zhang

Molecular Ecology Resources

ann stocker

Physical Review B

Nagendran Ramasamy

Patrícia L M Pederiva

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Tips for Online Students , Tips for Students

What is the Multiple Intelligences Theory?

Updated: November 24, 2022

Published: February 24, 2020

Did you know that each person has unique intelligence and that we thrive in certain learning environments while struggling in others? There are eight different types of intelligence, as put forth by Howard Gardner. People can have varying levels of intelligence, and they can change over time. Teachers can use multiple intelligences in the classroom for the benefit of their students by customizing lessons, classroom layouts, and assignments for these multiple intelligences.

Keep reading to find out about all eight bits of intelligence, how to implement multiple intelligences in the classroom, and how to benefit from them.

The Multiple Intelligences Theory throws away the idea that intelligence is one sort of general ability and argues that there are actually eight types of intelligence. One is not more important than the other, but some may help people succeed at different things.

For example, a person with high musical intelligence and low visual-spatial intelligence may succeed in music class but may struggle in art class.

Howard Gardner’s Theory of Multiple Intelligence

Howard Gardner of Harvard University first came up with the theory of multiple intelligences in 1983. Gardner argues that there are eight types of intelligence, far more than the standard I.Q. test can account for.

He goes on to say that these multiple intelligences “challenge an educational system that assumes that everyone can learn the same materials in the same way and that a uniform, universal measure suffices to test student learning.”

Gardner argues that schools and teachers should teach in a way that supports all types of intelligence, not just the traditional ones such as linguistic and logical intelligence.

The Eight bits of Intelligence

1. Linguistic Intelligence (“word smart”)

2. Logical-Mathematical Intelligence (“number/reasoning smart”)

3. Visual-Spatial Intelligence (“picture smart”)

4. Bodily-Kinesthetic Intelligence (“body smart”)

5. Musical Intelligence (“music smart”)

6. Interpersonal Intelligence (“people smart”)

7. Intrapersonal Intelligence (“self smart”)

8. Naturalist Intelligence (“nature smart”)

Linguistic Intelligence

Photo by patrick tomasso on unsplash.

Linguistic intelligence, also called verbal-linguistic intelligence, is about knowledge of language use, production, and possibilities.

Those with this type of intelligence have the ability to use language to express themselves and assign meaning by way of poetry, humor, stories, and metaphors. It is common for comedians, public speakers, and writers to be high in linguistic intelligence.

Teaching for Linguistic Intelligence:

Use the following activities and techniques for students and groups with high linguistic intelligence:

- Use creative writing activities such as poetry or scriptwriting

- Set up class debates

- Allow for formal speaking opportunities

- Use humor, such as joke writing or telling

- Make sure there are plenty of reading opportunities

Learning with Linguistic Intelligence:

Learn your best by writing, practicing speeches, creating jokes, journaling, and reading.

Logical-Mathematical Intelligence

Photo by yancy min on unsplash.

Logical-mathematical intelligence is commonly thought of as “scientific thinking,” or the ability to reason, work with abstract symbols, recognize patterns, and see connections between separate pieces of information. It makes it possible to go through the scientific process of calculating, quantifying, hypothesizing, and concluding.

This type of intelligence is high in scientists, mathematicians, computer programmers, lawyers, and accountants.

Teaching for Logical-Mathematical Intelligence:

Use the following activities and techniques for students and groups with high logical-mathematical intelligence:

- Provide opportunities for problem-solving

- Involve calculations

- Create activities that involve deciphering a code

- Use pattern or logic games

- Organize new information in an outline format

Learning with Logical-Mathematical Intelligence:

Learn your best by creating information outlines with points, and making patterns of the information.

Visual-Spatial Intelligence

Photo by matthieu comoy on unsplash.

Visual-spatial intelligence is all about the visual arts, graphics, and architecture. This type of intelligence allows people to visualize objects from different perspectives and in different ways, use objects within space, form mental images, and think in three-dimensions.

People high in visual-spatial intelligence include painters, architects, graphic designers, pilots, and sailors.

Teaching for Visual-Spatial Intelligence:

Use the following activities and techniques for students and groups with high visual-spatial intelligence:

- Use mind mapping techniques

- Use guided visualizations or verbal imagery

- Provide opportunities for artistic expression using a variety of mediums (paint, clay, etc.)

- Allow for make-believe or fantasy

- Create collages for visual representations

Learning with Visual-Spatial Intelligence:

Learn your best by creating something visual using space such as a collage, art piece, or written map of the information.

Bodily-Kinesthetic Intelligence

Photo by drew graham on unsplash.

Bodily-kinesthetic intelligence is the ability to use the body to express emotion, play games, or create new products. It is commonly referred to as “learning by doing.” This type of intelligence enables people to manipulate objects and the body.

High bodily-kinesthetic intelligence is common in dancers, athletes, surgeons and artisans.

Teaching for Bodily-Kinesthetic Intelligence:

Use the following activities and techniques for students and groups with high bodily-kinesthetic intelligence:

- Use body sculpture

- Use of role-playing, miming, or charade games

- Allow for physical exercise, dance, or martial arts

- Create opportunities for dramatic arts such as skits

- Use human graphs

Learning with Bodily-Kinesthetic Intelligence:

To learn at your best, try creating a movement routine or role-play to learn a concept or remember information.

Musical Intelligence

Photo by michael maasen on unsplash.

Musical intelligence is all about music. Individuals with high musical intelligence have a greater knowledge of and sensitivity to tone, rhythm, pitch, and melody. But this type of intelligence isn’t just about music — it’s also about sensitivity to the human voice, audio patterns, and sounds in the environment.

Composers, musicians, conductors, and sound directors all have high musical intelligence.

Teaching for Musical Intelligence:

Use the following activities and techniques for students and groups with high musical intelligence:

- Use instruments and instrument sounds

- Use environmental sounds to illustrate a concept

- Allow for musical composition and performance

- Allow students to create songs about a topic

Learning with Musical Intelligence:

To learn best with your musical intelligence, try making a song with content you need to know.

Interpersonal Intelligence

Photo by perry grone on unsplash.

Interpersonal intelligence is all about working with others and communicating effectively with others both verbally and nonverbally. It involves the ability to notice distinctions in others’ moods, temperaments, intentions, and motivations.

High interpersonal intelligence is often found in teachers, counselors, politicians, and religious leaders.

Teaching for Interpersonal Intelligence:

Use the following activities and techniques for students and groups with high interpersonal intelligence:

- Teach collaborative skills

- Provide plenty of group work opportunities

- Use person-person communication

- Use empathy

Learning with Interpersonal Intelligence:

To learn best with high interpersonal intelligence, try doing most of your work in a group or with another person. Try to put yourself in the shoes of people or situations you are learning about.

Intrapersonal Intelligence

Photo by doug robichaud on unsplash.

Intrapersonal intelligence involves knowledge of the self in ways such as feelings, a range of emotional responses, and intuition about spirituality. This type of intelligence allows people to be conscious of the unconscious and to discern higher patterns of connection between things in our world.

Psychologists, philosophers , and theologists have high intrapersonal intelligence.

Teaching for Intrapersonal Intelligence:

Use the following activities and techniques for students and groups with high intrapersonal intelligence:

- Practice meditation

- Allow for plenty of self-reflection

- Use mindfulness

- Practice reaching altered states of consciousness

Learning with Intrapersonal Intelligence:

To learn best with intrapersonal intelligence, try using mindful walks, meditation, and metacognition.

Naturalist Intelligence

Photo by sarah brown on unsplash.

Naturalist intelligence is about discerning, comprehending, and appreciating plants, animals, the atmosphere, and the earth. It involves knowing how to care for animals, live off the land, classify species, and understand systems in nature.

High naturalist intelligence is seen in farmers, zookeepers, botanists, nature guides, veterinarians, cooks, and landscapers/gardeners.

Teaching for Naturalist Intelligence:

Use the following activities and techniques for students and groups with high naturalist intelligence:

- Practice conservation

- Have a classroom plant or animals to care of

- Observe nature, go on nature walks

- Use species classification

- Provide hands-on labs of natural materials

Learning with Naturalist Intelligence:

To learn at your best, do your learning outdoors. Work with natural materials or animals as much as possible to work through concepts.

Educational Benefits of Applying Multiple Intelligences Theory

The benefits of this theory are many, and they can be applied across all ages and in all subjects. Students who are given ways to learn and perform at their best are more likely to enjoy school and are more likely to succeed academically.

Planning With Intelligence:

Variation Approach : When students are first made aware of the types of intelligence, they must complete activities of all types to better select their intelligence types.

Choice Approach : Students can be given the option to complete some activities of a long list of activities suited for different types of intelligence.

Bridge Approach : If most or all of the students in a classroom or group are high in the same type of intelligence, activity or classroom layout can be focused on that one type.

What Multiple Intelligences Theory Can Teach Us:

Additional research may be needed in order to understand the best possible methods to assess and support a range of intelligence in the classroom. For now, the theory has already taught students, teachers, parents, and administrators to broaden their definition of intelligence and to include all types in the equation.

Multiple Intelligences in the Classroom:

There are many ways to use the theory of multiple intelligences in the classroom.

How can Multiple Intelligences be Implemented in the Classroom?

Classroom Layout

The best way to layout a classroom to support multiple intelligences is to have places in the room that works for each type of intelligence.

For linguistic intelligence, there should be a quiet area for reading, writing, and practicing speeches.

For logical-mathematical intelligence, there should be an area where students can conduct scientific experiments.

For visual-spatial intelligence, include an open area for object manipulation or art creation.

For bodily-kinesthetic intelligences, an open area for body movement could be provided.

For musical intelligence, including a separate area for music listening and creating, perhaps with soundproofing or headphones.

For naturalistic intelligence, outdoor space or indoor aquarium or terrarium could be provided.

For interpersonal intelligence, there should be an area with large tables for group work, while for intrapersonal intelligence there should be areas for individual activities.

How to Identify the Intelligence in Your Classroom

It can be hard to identify which intelligences are in the classroom. Observation and working together with the students to understand what is working for them is key. University of the People offers a Master’s in Education , where you are taught to identify the types of intelligence and how to implement them.

Expand Upon Traditional Activities:

Traditional activities in the classroom tend to focus on linguistic and logical-mathematical types of intelligence. These should be expanded to include other types of intelligence as well. For example, teachers can use debate to teach logic or use clay manipulatives for math learning.

Results of This Program:

When multiple intelligences theory is implemented properly in the classroom, it can have very positive results . Students develop an increased sense of responsibility, self-direction, and independence, discipline problems are reduced, students develop and apply new skills, cooperative learning skills increase, and overall academic achievement increases.

The Teacher’s Role:

Photo by rio lecatompessy on unsplash.

The teacher’s role is extremely important in making sure students get the most out of multiple intelligences theory in the classroom. Teachers should work with the students, rather than for the students, to develop the best activities, projects, and layouts. Teachers should continuously observe students’ interests and successes in different areas and continually change the classroom layout and plan accordingly.

Teaching in the Way the Child Learns:

Teaching using the multiple intelligence theory is essentially teaching in the way the child learns. It involves giving up long-held traditional beliefs about how to teach and instead puts the child first at the center of the planning.

Factors In Educational Reform

According to Gardner, there are four factors in educational reform: assessment, curriculum, teacher education, and community participation.

Gardner argues that in addition to using multiple intelligences, educational reform should occur within the following: