How to Write a Creative Essay: Useful Tips and Examples

%20(1).webp)

Samuel Gorbold

Essay creative writing is not always seen as fun by most students, but the realm of creative essays can offer an enjoyable twist. The inherent freedom in choosing a topic and expressing your thoughts makes this type of paper a creative playground. Engaging in composing a creative essay provides an opportunity to flex your creative muscles. Yet, if you're new to crafting compositions, it can pose a challenge. This article guides you through the steps to write an impressive creative essay, helping you navigate the process seamlessly. In a hurry? Our writing service is there for you 24/7, with guidance and practical help.

What Is a Creative Essay

A creative essay is a form of writing that goes beyond traditional academic structures, allowing the author to express themselves more imaginatively and artistically. Unlike formal essays, creative ones emphasize storytelling, personal reflection, and the exploration of emotions. They often incorporate literary elements such as vivid descriptions, dialogue, and poetic language to engage readers on a more emotional and sensory level. Follow our creative essay tips to experiment with style and structure, offering a unique platform to convey ideas, experiences, or perspectives in a captivating and inventive way.

To answer the question what does creative writing mean, it’s necessary to point out that it departs from traditional academic writing, offering a canvas for artistic expression and storytelling. It diverges from the rigid structure of formal writings, providing a platform for writers to infuse their work with imagination and emotion. In this genre, literary elements such as vivid descriptions and poetic language take center stage, fostering a more engaging and personal connection with the reader.

Unlike a poem analysis essay , this form of writing prioritizes narrative and self-expression, allowing authors to delve into their experiences and perspectives uniquely. It's a departure from the conventional rules, encouraging experimentation with style and structure. Creative essays offer a distinct avenue for individuals to convey ideas and emotions, weaving a tapestry that captivates and resonates with readers on a deeper, more sensory level.

Creative Writing Essay Outline Explained From A to Z

Moving on, let's delve into how to write a creative writing essay from s structural perspective. Despite the focus on creativity and imagination, a robust structure remains essential. Consider your favorite novel – does it not follow a well-defined beginning, middle, and end? So does your article. Before diving in, invest some time crafting a solid plan for your creative writing essay.

.webp)

Creative Essay Introduction

In creative essay writing, the introduction demands setting the scene effectively. Begin with a concise portrayal of the surroundings, the time of day, and the historical context of the present scenario. This initial backdrop holds significant weight, shaping the atmosphere and trajectory of the entire storyline. Ensure a vivid depiction, employing explicit descriptions, poetic devices, analogies, and symbols to alter the text's tone promptly.

Creative Essay Body

The body sections serve as the engine to propel the storyline and convey the intended message. Yet, they can also be leveraged to introduce shifts in motion and emotion. For example, as creative writers, injecting conflict right away can be a powerful move if the plot unfolds slowly. This unexpected twist startles the reader, fundamentally altering the narrative's tone and pace. Additionally, orchestrating a fabricated conflict can keep the audience on edge, adding an extra layer of intrigue.

Creative Essay Conclusion

Typically, creative writers conclude the narrative towards the end. Introduce a conflict and then provide its resolution to tie up the discourse neatly. While the conclusion often doesn't lead to the story's climax, skilled writers frequently deploy cliffhangers. By employing these writing techniques suggested by our write my college essay experts, the reader is left in suspense, eagerly anticipating the fate of the characters without a premature revelation.

Creative Writing Tips

Every student possesses a distinct mindset, individual way of thinking, and unique ideas. However, considering the academic nature of creative writing essays, it is essential to incorporate characteristics commonly expected in such works, such as:

.webp)

- Select a topic that sparks your interest or explores unique perspectives. A captivating subject sets the stage for an engaging paper.

- Begin with a vivid and attention-grabbing introduction. Use descriptive language, anecdotes, or thought-provoking questions to draw in your readers from the start.

- Clearly articulate the main idea or theme of your essay in a concise thesis statement. This provides a roadmap for your readers and keeps your writing focused.

- Use descriptive language to create a sensory experience for your readers. Appeal to sight, sound, touch, taste, and smell to enhance the imagery.

- Play with the structure of your content. Consider nonlinear narratives, flashbacks, or unconventional timelines to add an element of surprise and creativity.

- If applicable, develop well-rounded and relatable characters. Provide details that breathe life into your characters and make them memorable to the reader.

- Establish a vivid and immersive setting for your narrative. The environment should contribute to the overall mood and tone.

- Blend dialogue and narration effectively. Dialogue adds authenticity and allows characters to express themselves, while narration provides context and insight.

- Revisit your essay for revisions. Pay attention to the flow, coherence, and pacing. Edit for clarity and refine your language to ensure every word serves a purpose.

- Share your creative writing article with others and welcome constructive feedback. Fresh perspectives can help you identify areas for improvement and refine your storytelling.

- Maintain an authentic voice throughout your essay. Let your unique style and perspective shine through, creating a genuine connection with your audience.

- Craft a memorable conclusion that leaves a lasting impression. Summarize key points, evoke emotions, or pose thought-provoking questions to resonate with your readers.

Types of Creative Writing Essays

A creative writing essay may come in various forms, each offering a unique approach to storytelling and self-expression. Some common types include:

- Reflects the author's personal experiences, emotions, and insights, often weaving in anecdotes and reflections.

Descriptive

- Focuses on creating a vivid and sensory-rich portrayal of a scene, person, or event through detailed descriptions.

- Tells a compelling story with a clear plot, characters, and often a central theme or message.

Reflective

- Encourages introspection and thoughtful examination of personal experiences, revealing personal growth and lessons learned.

Expository

- Explores and explains a particular topic, idea, or concept creatively and engagingly.

Persuasive

- Utilizes creative elements to persuade the reader to adopt a particular viewpoint or take a specific action.

Imaginative

- These creative writing papers allow for the free expression of imagination, often incorporating elements of fantasy, surrealism, or speculative fiction.

Literary Analysis

- Learning how to write a creative writing essay, analyze and interpret a piece of literature, and incorporate creativity to explore deeper meanings and connections.

- Blends personal experiences with travel narratives, offering insights into different cultures, places, and adventures.

- Focuses on creating a detailed and engaging portrait of a person, exploring their character, experiences, and impact on others.

Experimental

- Pushes the boundaries of traditional essay structures, experimenting with form, style, and narrative techniques.

- Combines elements from different essay types, allowing for a flexible and creative approach to storytelling.

As you can see, there are many types of creative compositions, so we recommend that you study how to write an academic essay with the help of our extensive guide.

How to Start a Creative Writing Essay

Starting a creative writing essay involves capturing the reader's attention and setting the tone for the narrative. Here are some effective ways to begin:

- Pose a thought-provoking question that intrigues the reader and encourages them to contemplate the topic.

- Begin with a short anecdote or a brief storytelling snippet that introduces the central theme or idea of your essay.

- Paint a vivid picture of the setting using descriptive language, setting the stage for the events or emotions to unfold.

- Open with a compelling dialogue that sparks interest or introduces key characters, immediately engaging the reader in the conversation.

- Incorporate a relevant quotation or epigraph that sets the mood or provides insight into the essay's theme.

- Begin with a bold or intriguing statement that captivates the reader's attention, encouraging them to delve further into your essay.

- Present a contradiction or unexpected scenario that creates a sense of curiosity and compels the reader to explore the resolution.

- Employ a striking metaphor or simile that immediately draws connections and conveys the essence of your creative essay.

- Start by directly addressing the reader, creating a sense of intimacy and involvement right from the beginning.

- Establish the mood or atmosphere of your essay by describing the emotions, sounds, or surroundings relevant to the narrative.

- Present a dilemma or conflict that hints at the central tension of your essay, enticing the reader to discover the resolution.

- Start in the middle of the action, dropping the reader into a pivotal moment that sparks curiosity about what happened before and what will unfold.

Choose an approach to how to write a creative essay that aligns with your tone and theme, ensuring a captivating and memorable introduction.

Creative Essay Formats

Working on a creative writing essay offers a canvas for writers to express themselves in various formats, each contributing a unique flavor to the storytelling. One prevalent format is personal writing, where writers delve into their own experiences, emotions, and reflections, creating a deeply personal narrative that resonates with readers. Through anecdotes, insights, and introspection, personal essays provide a window into the author's inner world, fostering a connection through shared vulnerabilities and authentic storytelling.

Another captivating format is the narrative, which unfolds like a traditional story with characters, a plot, and a clear arc. Writers craft a compelling narrative, often with a central theme or message, engaging readers in a journey of discovery. Through vivid descriptions and well-developed characters, narrative articles allow for the exploration of universal truths within the context of a captivating storyline, leaving a lasting impression on the audience.

For those who seek to blend fact and fiction, the imaginative format opens the door to vivid exploration. This format allows writers to unleash their imagination, incorporating elements of fantasy, surrealism, or speculative fiction. By bending reality and weaving imaginative threads into the narrative, writers can transport readers to otherworldly realms or offer fresh perspectives on familiar themes. The imaginative essay format invites readers to embrace the unexpected, challenging conventional boundaries and stimulating creativity in both the writer and the audience. Check out our poetry analysis essay guide to learn more about the freedom of creativity learners can adopt while working on assignments.

Creative Essay Topics and Ideas

As you become familiar with creative writing tips, we’d like to share several amazing topic examples that might help you get out of writer’s block:

- The enchanted garden tells a tale of blooms and whispers.

- Lost in time, a journey through historical echoes unfolds.

- Whispering winds unravel the secrets of nature.

- The silent symphony explores the soul of music.

- Portraits of the invisible capture the essence of emotions.

- Beyond the horizon is a cosmic adventure in stardust.

- Can dreams shape reality? An exploration of the power of imagination.

- The forgotten key unlocks doors to the past.

- Ripples in the void, an exploration of cosmic mysteries.

- Echoes of eternity are stories written in the stars.

- In the shadow of giants, unveils the unsung heroes.

- Can words paint pictures? An exploration of the artistry of literary expression.

- Whispers of the deep explore the ocean's hidden stories.

- Threads of time weave lives through generations.

- Do colors hold emotions? A journey of painting the canvas of feelings.

- The quantum quandary navigates the world of subatomic particles.

- Reflections in a mirror unmask the layers of identity.

- The art of silence crafts narratives without words.

- The ethereal dance explores movement beyond the visible.

- Can shadows speak? Unveiling stories cast in darkness.

Examples of Creative Writing Essays

We've added a couple of brief creative writing essays examples for your reference and inspiration.

Creative Writing Example 1: Admission Essay

Creative writing example 2: narrative essay.

What Are the Types of Creative Writing Essays?

What is a creative writing essay, how to start a creative writing essay, what are some creative writing tips.

Samuel Gorbold , a seasoned professor with over 30 years of experience, guides students across disciplines such as English, psychology, political science, and many more. Together with EssayHub, he is dedicated to enhancing student understanding and success through comprehensive academic support.

- Plagiarism Report

- Unlimited Revisions

- 24/7 Support

Ekphrasis is a literary device in which a work of art, usually visual, inspires a piece of poetry or prose. Ekphrastic poetry, then, describes a poem that finds inspiration in the creative elements of a piece of art. If you’ve recently been moved by artwork, or if you’re looking to find inspiration, you may be interested in learning how to write an ekphrastic poem.

The art of ekphrasis populates both classic and contemporary poetry. You may be familiar with William Carlos Williams’ “ Landscape with the Fall of Icarus ” (inspired by Bruegel’s painting), or the poem “ Ode on a Grecian Urn” by John Keats , one of the more popular works of ekphrastic poetry. While classical poems find inspiration solely in visual art, this article includes a contemporary twist, as we’ll examine poetry inspired by film, dreams, and the many other ways that humans express themselves.

Before we look at different ekphrastic poem examples, let’s dive a little deeper into the form. What is ekphrastic poetry, and what is ekphrasis?

Ekphrastic Poetry: Contents

Ekphrasis Definition

What is ekphrastic poetry, ekphrastic poetry about art, ekphrastic poetry about movies and tv, ekphrastic poetry about photography, ekphrastic poetry about music, ekphrastic poetry about dance, ekphrastic poetry about sculpture, ekphrastic poetry about dreams, how to write an ekphrastic poem.

The word ekphrasis comes from the Ancient Greek—its literal translation is to “speak out.” Ekphrasis was originally a rhetorical exercise in which students wrote descriptions of visual art. Over time, the word has come to describe any form of literature that finds inspiration in other forms of artwork.

Fun fact: as you might expect, some of the earliest examples of ekphrastic poetry come from Ancient Greece. The Iliad , for example, includes about 150 lines describing the shield of Achilles.

If ekphrasis is the art of writing about art, then ekphrastic poetry is poetry inspired by other creative works. Art, sculpture, architecture, film, television, and even dreams are all fertile material for the ekphrastic poem.

What is ekphrastic poetry?: Poetry inspired by other creative works, such as art, sculpture, architecture, film, television, and even dreams.

Note: a poem inspired by other writing does not count as ekphrastic poetry. Ekphrasis only refers to work inspired by other forms of media—art outside of the written word.

Why should a writer employ ekphrasis, or try to write ekphrastic poetry? While it might seem counterintuitive to make art about existing art—it already exists, after all—don’t discount the importance of interpretation and description. Ekphrasis provides a challenging exercise for the writer trying to hone imagery, and it also lets writers explore the power and complexity of the artwork that moves them. We’ll see this in action through the ekphrastic poem examples we’ve included.

Ekphrastic Poem Examples

Ekphrasis is a prominent feature of classical works of literature. It shows up frequently in epic poems like The Iliad , The Odyssey , The Aeneid, and The Metamorphoses , and the Romantic poets also frequently wrote ekphrastic poetry, in part because they were so inspired by classical art.

Nonetheless, the ekphrastic poem examples we’re including all come from contemporary poetry, to showcase the modern possibilities of this device. Additionally, we’ve sectioned these examples based on the form of art each poem was inspired by.

Note that ekphrasis is a device, not a form, so an ekphrastic poem can take a wide variety of poetry forms , and contemporary examples are often free verse .

“Her Vanity” by Marc Alan Di Martino

Retrieved from Rattle .

My mother used to sit like this before her vanity, her shoulders bathed in blue and pink light, her powdered skin dredged in a cloud of talc, breathing it in. Oblivious at seventeen, she wanted more than anything to look her best when Eddie Fisher offered her a Coke in his posh Manhattan hotel suite. I sat with her in a room off Times Square years later, our last outing together before the nursing homes enchained her. She told me the story—as she said, for the umpteenth time—of how she’d met the singer whose career nosedived the day Elvis broke the charts with “Heartbreak Hotel.” They shared a Coke, the story went: his lips kissing the weightless ‘O’ of the glass bottle which was furtively snatched up from where he’d set it down, forgotten it, by her swift hand. Later, she told us about the talcosis, how it affected her breathing. For the rest of her life she saw a pulmonologist. I sat there letting her regale me with the tale of Eddie Fisher for the umpteenth time in a cheap hotel room off Times Square, a crooked mirror fixed above the sink a painting of a woman on the wall which might have been her, poised at her vanity, poisoning herself for love.

You can find the painting this was written about here .

This poem’s effortless beauty hinges, ironically, off the word “vanity”. Not only is the speaker’s mother sitting in front of a mirror, she is also sitting in front of the concept of vanity—“poisoning herself for love” with talc. The poem’s topic and language reflects the airy, ethereal quality of the painting, forcing the reader to consider the value of beauty.

Other ekphrastic poem examples about art include:

- “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus” by William Carlos Williams ( Academy of American Poets )

- “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus: Oil on Canvas: Pieter Bruegel the Elder: 1560” by Paul Tran ( New England Review )

- “Star Map With Action Figures” by Carl Philips ( VQR )

“Laura Palmer Graduates” by Amy Woolard

Retrieved from Poetry Foundation .

I can’t love them if their hands aren’t all tore up From something, guitar strings, kitchen knives & grease

Burns, heaving the window ACs onto their crooked old Sills come June. Fighting back. That porchlight’s browned

Inside with moth husks again & I can’t climb a ladder To save my life, i.e., the world spins. Even when it’s lit,

It’s half ash. Full-drunk under a half-moon & I’m dazed We’re all still here. Most of us, least. For the one & every

Girl gone, I sticker gold stars behind my front teeth so I can taste just how good we were. I swear I can’t

Love them if they can’t fathom why an unlit ambulance On a late highway means good luck. I hold my cigarette-

Smoking arm upright like I’m trying to keep blood From rushing to a cut. What’s true is my shift’s over &

I’m here with you now & I’m wrapped up tight On the steps like a top sheet like the morning paper

Before it’s morning. Look up & smile. What does it matter That the stars we see are already dead. If that’s the case well

Then the people are too. Alive is a little present I Give myself once a day. Baby, don’t think I won’t doll

Up & look myself fresh in the eyes, in the vermilion Pincurl of my still heart & say: It’s happening again.

If you’ve watched Twin Peaks, you’ll understand some of the references in this poem, namely the last line “It’s happening again.” This poem pulls a lot from the Twin Peaks aesthetic: torn up hands and cigarettes and ambulances and porchlights and blood. But, even if you haven’t seen the TV show, you can still feel the loneliness and determination coursing through the poem, captured succinctly in the line “Alive is a little present I / Give myself once a day.”

Other ekphrastic poem examples about movies and TV include:

- “Rude Girl is Lonely Girl!: Five Poems Inspired by Jessica Jones” by Melissa Lozada-Oliva ( FreezeRay )

- “Asami Writes to Korra for Three Years” by Natalie Wee ( Wildness )

- “The Blue Angel” by Allen Ginsberg, retrieved here .

Also, this isn’t a poem, but it is a work of ekphrastic literature about TV and movies, and also is one of my favorite short stories of all time. If you’re interested in ekphrastic prose, read “ Especially Heinous ” by Carmen Maria Machado in The American Reader.

“This Room” by Devon Balwit

Retrieved here, from Rattle .

He asks to make love, and because he asks, I do, though my aging desire has turned instead to

the bedside table, to the London Review of Books, to the now sexier pursuit

of end rhymes and long walks through leaf-blaze. I’d never thought it true

that the fathomless lust of thirty-two could silt and still. Now, I must brew

it up if I want it. It’s not you, I hasten to tell him, unclewing

his anxiety and letting the breeze undo How much earnest whispering this room

has witnessed—plans to make new life, plans to help failing parents move

to their last dependency, rue at lost chances, the shy wooing

of new ones—this, too, what lovers do between the sheets. The view

from the window doesn’t get old, the moon, and morning peeking in, the bed imbued

with both solemnity and mirth, the glue that binds us, like two ancient, tangled yews.

You can find the photo that this poem was written about here .

This poem captures the complexity of love at a certain stage, when the relationship has settled into a familiar cadence and passion has tempered to wisdom. The photo itself captures a seemingly ordinary moment—wind blowing through a window curtain. This is a great piece of ekphrasis, as the poet has turned this image into a symbol of domestic love, examining the ways that relationships evolve with age.

Other ekphrastic poem examples about photography include:

- “Panic at John Baldessari’s Kiss” by Elena Karina Byrne ( Poetry Foundation )

- “An Ekphrastic Sonnet based off the To Pimp A Butterfly album cover where Kendrick speaks to the baby he is holding” by Myles Yates ( FreezeRay )

- “Postcard I almost send to an almost lover” by Emily Wilson ( The Bohemyth )

Technically, ekphrasis only describes writing inspired by visual art. But, this article is all about finding inspiration in other forms of media, so let’s look at how music has inspired contemporary poetry.

“J. S. Bach: F# Minor Toccata” by Bill Holm

Retrieved here, from Academy of American Poets .

This music weeps, not for sin but rather for the black fact that we must all die, but not one of us knows what comes after. This music leaps from key to key as if it had no clear place to arrive, making up its life, one bar at a time. But when you come at last to the real theme, strict, inexorable, and bleak, you must play it slow and sad, with melancholy dignity, or you miss all its grim wisdom. In three pages, it says, the universe collapses, and you—still only halfway home.

You can listen to Bach’s Toccata in F# Minor here .

This is, certainly, a morbid interpretation of Bach’s toccata, but close attention to the music’s minor key and melancholy reveals the sense of anguish and panic resonating through the poem. The speaker hones in on the frenetic dance of keys seeking salvation all over the piano, finding our own shared mortality reflected in F sharp.

Other ekphrastic poem examples about music include:

- “Hammond B3 Organ Cistern” by Gabrielle Calvocoressi ( The New Yorker )

- “Cardi B Tells Me about Myself” by Eboni Hogan ( Poetry Foundation )

- “When I Die Bury Me In The 2am Music From Animal Crossing: New Horizons for Nintendo Switch” by Erich Haygun ( FreezeRay )

To learn more about poetry inspired by music, start with this article on the history of jazz poetry.

How can a dance be transcribed to verse? This persona poem about the ballet dancer Vaslav Nijinsky demonstrates the potential for poetry to dance across the page, moving as limbs do on the stage.

“The War of Vaslav Nijinsky” by Frank Bidart

Excerpted from The Paris Review .

—The second part of my ballet Le Sacre du Printemps

is called “THE SACRIFICE.”

A young girl, a virgin, is chosen to die so that the Spring will return,—

so that her Tribe (free from “pity,” “introspection,” “remorse”)

out of her blood can renew itself.

The fact that the earth’s renewal requires human blood

is unquestioned; a mystery.

She is chosen, from the whirling, stamping circle ofher peers, purely by chance—;

then, driven from the circle, surrounded by the elders, by her peers, by animal skulls impaled on pikes,

she dances,—

at first, in paroxysms of Grief, and Fear:—

again and again, she leaps (— NOT

as a ballerina leaps, as if she loved the air, as if the air were her element—)

BECAUSE SHE HATES THE GROUND.

But then, slowly, as others join in, she finds that there is a self

WITHIN herself

that is NOT HERSELF

impelling her to accept,—and at last to LEAD ,—

that is her own sacrifice . . .

—In the end, exhausted, she falls to the ground . . .

She dies; and her last breath is the reawakened Earth’s

orgasm,— a little upward run on the flutes mimicking

(—or perhaps MOCKING—)

the god’s spilling seed . . .

The Chosen Virgin accepts her fate: without considering it,

she knows that her Tribe,— the Earth itself,— are UNREMORSEFUL

that the price of continuance is her BLOOD:—

she accepts their guilt,—

. . . THEIR GUILT

THAT THEY DO NOT KNOW EXISTS.

She has become, to use our term, a Saint.

This excerpt comes from a much longer piece inspired by the life of Vaslav Nijinsky. Notice how this poem moves like a dance, lilting and crescendoing, speeding and slowing down, whirling around the page. There is almost a sense of phanopoeia—of the poem feeling like the dance it tries to describe.

Sculpture is one of the oldest art forms in human history. It’s no wonder, then, that there is so much ekphrastic poetry on the topic!

“Reflection on the Vietnam War Memorial” by Jeffrey Harrison

Retrieved here.

Here is, the back porch of the dead. You can see them milling around in there, screened in by their own names, looking at us in the same vague and serious way we look at them.

An underground house, a roof of grass — one version of the underworld. It’s all we know of death, a world like our own (but darker, blurred). inhabited by beings like ourselves.

The location of the name you’re looking for can be looked up in a book whose resemblance to a phone book seems to claim some contact can be made through the simple act of finding a name.

As we touch the name the stone absorbs our grief. It takes us in — we see ourselves inside it. And yet we feel it as a wall and realize the dead are all just names now, the separation final.

This poem was written in 1987, 5 years after the completion of the Vietnam Veterans War Memorial. Pay attention to how Harrison’s description of the memorial tells us something about what it commemorates. What does it mean that the names of the veterans are “screened in,” that their names are clustered together like those in a phone book? The last stanza is particularly gutting, asking us to consider what it means that our grief is set in stone, yet living on, whereas the dead are now just names.

Other ekphrastic poem examples about sculptures include:

- “ Ozymandias ” by Percy Bysshe Shelley

- “ Le Masque ” by Charles Baudelaire

- “ Sculptor ” by Sylvia Plath

Wait a minute, dreams aren’t art. Are they?

While a dream is not a published work of visual media, a poem written about a dream can be considered a work of “notional ekphrasis.” Notional ekphrasis refers to writing about art that doesn’t yet exist. Some scholars extend the idea of notional ekphrasis to include dreams, since they are intangible, creative efforts of the brain, and our interpretation of our own dreams is itself a form of art.

As such, here are a few examples of writing inspired by dreams. While we don’t have access to the dreams themselves, pay attention to how these poems lean into the mystery of our dream worlds.

“Birds Appearing in a Dream” by Michael Collier

Retrieved from Academy of American Poets .

One had feathers like a blood-streaked koi, another a tail of color-coded wires. One was a blackbird stretching orchid wings, another a flicker with a wounded head.

All flew like leaves fluttering to escape, bright, circulating in burning air, and all returned when the air cleared. One was a kingfisher trapped in its bower,

deep in the ground, miles from water. Everything is real and everything isn’t. Some had names and some didn’t. Named and nameless shapes of birds,

at night my hand can touch your feathers and then I wipe the vernix from your wings, you who have made bright things from shadows, you who have crossed the distances to roost in me.

This poem accepts the mystery of dreams with ease. It doesn’t attempt to explain the birds, just follows their flights in crystalline language. The words both clarify and obfuscate, much like dreams do, and turns of phrase like “orchid wings” and “bright things from shadows” both delight and mystify the reader. When the poem turns toward “you,” we see how the speaker is interpreting the dream, yet the poem continues to describe the dream without explanation.

Other ekphrastic poem examples about dreams include:

- “The Song in the Dream” by Saskia Hamilton ( Academy of American Poets )

- “I Had a Dream About You” by Richard Siken ( retrieved here )

- “The Dream” by David Solway ( The Atlantic )

Additionally, at the beginning of the pandemic, many people reported having strange dreams. For more inspiration, a small archive of those dreams are recorded at the website I Dream of Covid .

The following steps will help you generate delightful, immersive ekphrastic poetry.

1. How to Write an Ekphrastic Poem: Find Inspiration

If you already have a work of art you know you want to write about, skip this step.

If you want to write about a piece of media, but don’t know what to write about or where to begin, finding inspiration is the first step. But where can you find inspiration? We’ll skip the normal advice—going to museums or listing your favorite works of art—and head straight to sites where you can jumpstart your ekphrasis.

First, you might be inspired by certain literary journals. FreezeRay publishes poetry on pop culture, with an emphasis on what’s nerdy and niche. Additionally, Rattle runs a monthly ekphrastic poetry competition that’s free to enter, using art and photography made by contemporary artists. Two winners are selected each month, and each wins $100!

Here are some sites you can navigate to find visual media that will inspire your ekphrastic poetry:

- The Met Museum hosts an online archive of their collection.

- So does The Frick , The Whitney , The MoMA , Getty , and The Guggenheim . Chances are, your local museum also has an online archive. Better yet, search for museums in random cities and see what they have online!

- The National Archives keeps this photography collection .

- Do you think space is cool? NASA’s photography collection thinks so too!

- Issuu is a publishing platform for independent journals and magazines. Much of the work on the site is free, and you might find inspiration from indie pubs and zines. Note the sections on art, architecture, music, and movies.

Lastly, you never know what archives your local library has access to. Check to see what you might be able to find: some libraries offer free JSTOR access or have digital archives of their own.

2. How to Write an Ekphrastic Poem: Start With Imagery

Once you feel inspired by a work of art, start immersing yourself in the artwork. The key is to feel the artwork so strongly that you can relay it to the reader, and they, too, can experience the art (or movie, song, picture, etc.) the way you do.

Then, spend some time writing about your experience sitting with this artwork. It doesn’t have to be poetic: it can be a journal entry, a list, even just words jotted on the back of a napkin. Take your time with this, as it will help you stay immersed.

As you write, hone in on imagery . Be specific about what aspects of the artwork are contributing to your experience with the art.

For example, let’s say you feel moved by the swirling patterns in Van Gogh’s “Starry Night.” Move away from simple descriptions like “swirling patterns.” Instead, choose specificity: “moonlight roils the dark night, stars like bright fish eddying the sky.” Show, don’t tell , and when in doubt, try similes and metaphors .

And remember: imagery is not just visual—there is also olfactory, tactile, auditory, gustatory, kinesthetic, and organic imagery. If you’re at a loss for details, try being synesthetic. How does your painting smell? What does your song taste like?

3. How to Write an Ekphrastic Poem: Find Threads, Themes, Core Ideas

Take a look back at what you wrote. What images stand out the most intensely? What patterns do you notice? Are there ideas, themes , threads you can draw through the notes you jotted down?

Examine what you wrote and what details seem best at immersing the reader in the artwork. These notes, of course, are not the final poem, or even the final set of images and ideas you’re working with; they’re simply a place to begin.

After you’ve taken note of what seems like the central ideas and images of the work, you can begin constructing an ekphrastic poem around those notes.

4. How to Write an Ekphrastic Poem: Stitch Imagery Together, Find Insight

Start juxtaposing your notes, list items, and images. Arrange ideas together so that, in their gestalt, you recreate both the artwork you’re describing and your experience of the art itself.

Spend time on this process, and write different drafts where you rearrange, recombine, and rewrite your ideas and images. The goal is to convey to the reader what it was really like for you to experience the art.

Throughout this process, you may come to deeper insights about your relationship to the art. Lean into those insights, and write them into the poem. Try to braid your insights with the imagery: too much of one or the other might overwhelm the reader, but walking them through your experience, moment by moment, of the artwork will help relay your experiences.

5. How to Write an Ekphrastic Poem: Compare Your Draft With the Artwork

No ekphrastic poem can fully capture the details of the art it’s inspired by. After all, ekphrastic poetry is itself an exercise in interpretation, which inevitably means certain details get excised in the writing.

Nonetheless, you want your poem to convey your experiences and reflect the beauty of the artwork itself. Compare your poem with the art. Have you captured those experiences?

This is not an easy skill to hone, which is why any of the above ekphrastic poem examples are great places to begin. How does the poem compare with the artwork it’s describing? If the artwork is elegant, the poem should be, too. If the artwork is searing, transformative, painful, lyrical, brilliant, etc., do you see that reflected in the poem? How so? Read like a poet , then apply this skill to your own writing.

6. How to Write an Ekphrastic Poem: Edit

Keep tinkering with language until your poem feels true to the artwork. Again, the goal is not for the reader to imagine the precise details of the art; poetry has nothing to do with hyperrealism here. The goal is to transmit experiences and insights, relating to the reader how you, the poet, have been moved and inspired by the art.

Get Inspired at Writers.com

Want to get feedback on your ekphrastic poetry? Writers.com can help. Take a look at our upcoming online poetry courses , where you will receive expert feedback on all the work you submit. In the meantime, the world is filled with art and inspiration, you just have to look and listen.

Sean Glatch

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

13.4: Sample essay on a poem

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 225950

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Example: Sample essay written on a Langston Hughes' poem

The following essay is a student’s analysis of Langston Hughes’ poem “I, Too” (poem published in 1926) I, too, sing America. I am the darker brother. They send me to eat in the kitchen When company comes, But I laugh, And eat well, And grow strong. Tomorrow, I’ll be at the table When company comes. Nobody’ll dare Say to me, “Eat in the kitchen,” Then. Besides, They’ll see how beautiful I am

And be ashamed — I, too, am America.

Last name 1

Student Name

Professor Name

English 110

Creating Change by Changing Minds

When I log onto Facebook nowadays and scroll through my feed, if it's not advertisements, it's posts talking about the injustices of the world, primarily from racism. These posts are filled with anger and strong hostility. I'm not saying anger is the wrong emotion to feel when faced with injustice, but when that hostility is channeled into violence, this does not bring about justice or change. Long lasting and effective change can only be made through non-violent methods, which is demonstrated by Langston Huges in his poem, "I, Too." In this short poem, Hughes gives many examples of how to effectively and on-violently address and combat racism.

Huges first uses people's religious morality to enlist his readers to resist racism. He starts the poem with his black narrator asserting, "I am the darker brother" (2). Brother to whom? In the Christian religion, a predominate religion during the times of slavery in the U.S and beyond, the terms brother and sister are used to show equality and kinship, and this human connection transcends race. Everyone is equal as children of God, and are all heirs to the promises of divine love and salvation. Simply by the black narrator calling himself a brother, Hughes is attempting to appeal to white Christian Americans, and to deny this connection is to go against the teachings in the Bible about brotherhood. This is very powerful in multiple ways. Firstly, establishing a sense of brotherhood and camaraderie should make anyone who tarnishes that unity feel ashamed. Secondly if anyone truly wishes to receive God's mercy, they would have to treat everyone as equals, or be punished by God, or even be denied eternal life in heaven all together. This technique is effective and long-lasting because the fear or violence inflicted on a person is temporary, but damnation is eternal.

Hughes further combats racism, not through threats of uprisings or reprisals, but rather by transforming hatred into humor and positivity. In response to his segregation, the narrator says, "They send me to eat in the kitchen/When company comes,/But I laugh,/And eat well/And grow strong" (3-7). With this, Hughes rises about racial exclusion and asks his reader to see it for what it is, ridiculous. He also shows how to effectively combat this injustice which is to learn from it and to feel empowered by not letting racists treatment from others hurt, define or hold you back. Additionally, this approach is an invitation to Hughes' white readers to be "in on the joke" and laugh at the mindless and unwarranted exclusion of this appealing and relatable person who is full of confidence and self-worth. Through his narrator, Hughes diffuses racial tensions in an inclusive and non-threatening way, but the underlying message is clear: equality is coming soon. We know he believes this when the poem's speaker states, "Tomorrow,/I'll be at the table/When company comes" (8-10). There is a strong assertion here that racism will not be permitted to continue, but the assertion is not a threat. Hughes carefully navigates the charged issue of racial unity here, particularly at the time he wrote this poem when segregation was in many places in the U.S. the law. The different forms of segregation-emotional, physical, financial, social-that blacks have suffered has and continues to result in violence, but Hughes here shows another path. Highes shows that despite it all, we can still make amends and site down at a table together. As a human family, we can overcome our shameful past by simply choosing to peacefully come together.

Finally Hughes uses American patriotism as a powerful non-violent method to unite his readers to combat racism. The poem concludes, "Besides,/They'll see how beautiful I am/And be ashamed-/I, too, am American" (15-18). Notice how he uses the word American and not American. He is not simply just an inhabitant of America he IS American in that he represents the promise, the overcoming of struggle, and the complicated beauty that makes up this country. He is integral to America's past, present and future. He is, as equally as anyone else, a critical piece in America's very existence and pivotal to its future. As Hughes united his readers through religion and the use of "brother," here he widens the net beyond religion and appeals to all Americans. As we say in our pledge of allegiance, we stand "indivisible with liberty and justice for all." To hate or exclude someone based on race, therefore, is to violate the foundational and inspirational tenants of this country. Hughes does not force or attack in his poem, and he does not promise retribution for all the harms done to blacks. He simple shows that racism in incompatible and contradictory to being truly American, and this realization, this change of heart, is what can bring about enduring change.

It has been shown over and over that violence leads to more violence. Violence might bring about change temporarily, but when people are stripped of choice, violence will reassert itself. Some of the most dramatic social movements that have brought about real change have used non-violent means as seen in Martin Luther King Jr's non-violent protests helping to change U.S. laws and ensure Civil Rights for all, as seen in Gandhi's use of non-violent methods to rid India of centuries of oppressive British rule, and as seen in Nelson Mandela's persistent and non-violent approaches of finally removing Apartheid from South Africa. However, we are not these men. Mos tof us are not leaders of movements, but we are each important and influential. We as individuals can be immensely powerful if we choose to be. We can choose to apply the examples and advice from enlightened minds like Hughes, King, Gandhi, and Mandela. When we see on Facebook or in the news on in-person people targeting or excluding others, or inciting violence againist a person or group based on race, or sexual orientation, or religion, or any other arbitrary difference selected to divide and pit us against one another, we can choose instead to respond with kindness, with humor, with positivity, and with empathy because this leads to the only kind of change that matters.

Works Cited

Hughes, Langston. "I, Too." African-American Poetry: An Anthology 1773-1927 , edited by Joan R.

Sherman, Dover Publications, Inc. Mineola, New York. 1997, p. 74.

A Full Guide to Writing a Perfect Poem Analysis Essay

01 October, 2020

14 minutes read

Author: Elizabeth Brown

Poem analysis is one of the most complicated essay types. It requires the utmost creativity and dedication. Even those who regularly attend a literary class and have enough experience in poem analysis essay elaboration may face considerable difficulties while dealing with the particular poem. The given article aims to provide the detailed guidelines on how to write a poem analysis, elucidate the main principles of writing the essay of the given type, and share with you the handy tips that will help you get the highest score for your poetry analysis. In addition to developing analysis skills, you would be able to take advantage of the poetry analysis essay example to base your poetry analysis essay on, as well as learn how to find a way out in case you have no motivation and your creative assignment must be presented on time.

What Is a Poetry Analysis Essay?

A poetry analysis essay is a type of creative write-up that implies reviewing a poem from different perspectives by dealing with its structural, artistic, and functional pieces. Since the poetry expresses very complicated feelings that may have different meanings depending on the backgrounds of both author and reader, it would not be enough just to focus on the text of the poem you are going to analyze. Poetry has a lot more complex structure and cannot be considered without its special rhythm, images, as well as implied and obvious sense.

While analyzing the poem, the students need to do in-depth research as to its content, taking into account the effect the poetry has or may have on the readers.

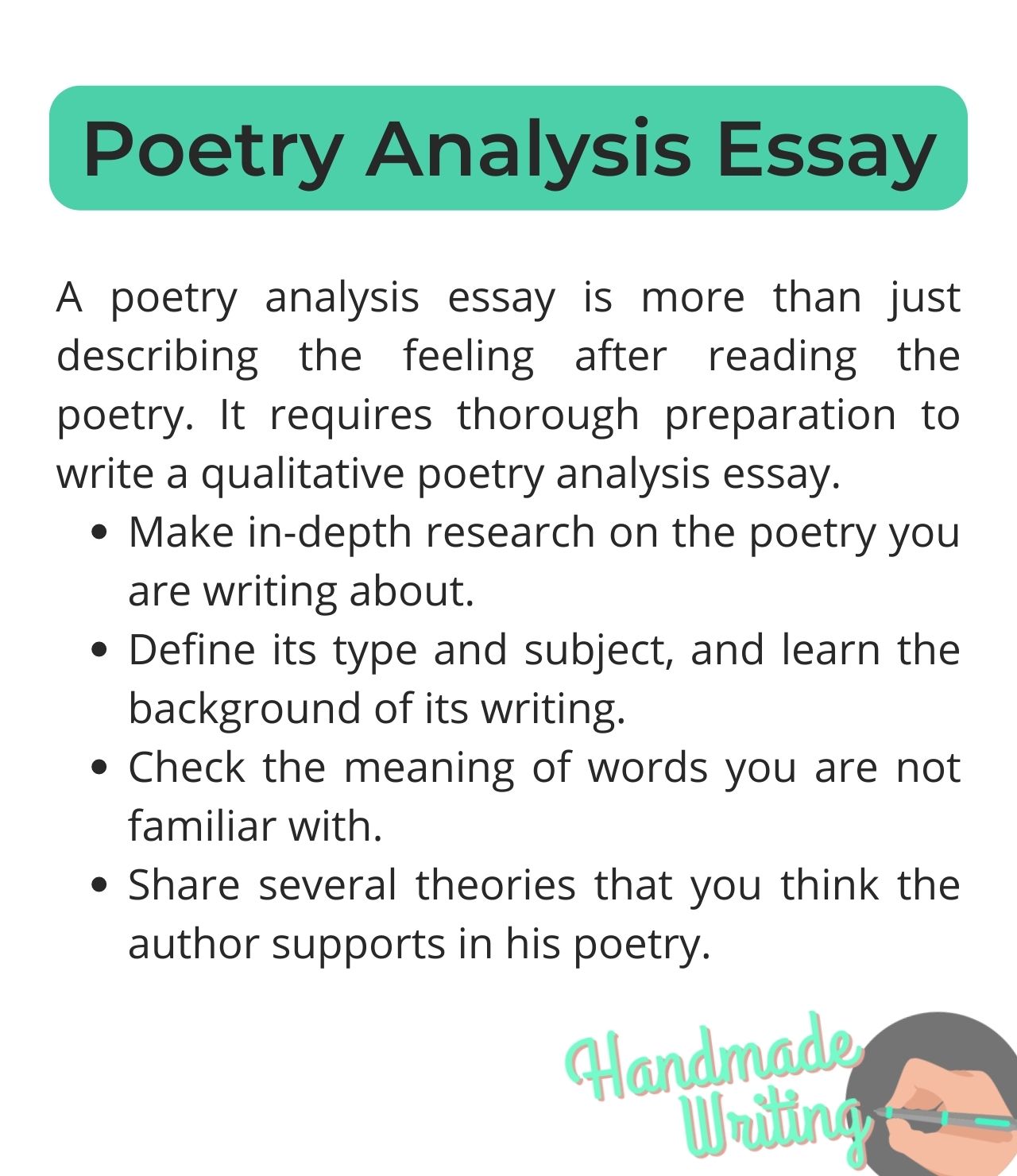

Preparing for the Poetry Analysis Writing

The process of preparation for the poem analysis essay writing is almost as important as writing itself. Without completing these stages, you may be at risk of failing your creative assignment. Learn them carefully to remember once and for good.

Thoroughly read the poem several times

The rereading of the poem assigned for analysis will help to catch its concepts and ideas. You will have a possibility to define the rhythm of the poem, its type, and list the techniques applied by the author.

While identifying the type of the poem, you need to define whether you are dealing with:

- Lyric poem – the one that elucidates feelings, experiences, and the emotional state of the author. It is usually short and doesn’t contain any narration;

- Limerick – consists of 5 lines, the first, second, and fifth of which rhyme with one another;

- Sonnet – a poem consisting of 14 lines characterized by an iambic pentameter. William Shakespeare wrote sonnets which have made him famous;

- Ode – 10-line poem aimed at praising someone or something;

- Haiku – a short 3-line poem originated from Japan. It reflects the deep sense hidden behind the ordinary phenomena and events of the physical world;

- Free-verse – poetry with no rhyme.

The type of the poem usually affects its structure and content, so it is important to be aware of all the recognized kinds to set a proper beginning to your poetry analysis.

Find out more about the poem background

Find as much information as possible about the author of the poem, the cultural background of the period it was written in, preludes to its creation, etc. All these data will help you get a better understanding of the poem’s sense and explain much to you in terms of the concepts the poem contains.

Define a subject matter of the poem

This is one of the most challenging tasks since as a rule, the subject matter of the poem isn’t clearly stated by the poets. They don’t want the readers to know immediately what their piece of writing is about and suggest everyone find something different between the lines.

What is the subject matter? In a nutshell, it is the main idea of the poem. Usually, a poem may have a couple of subjects, that is why it is important to list each of them.

In order to correctly identify the goals of a definite poem, you would need to dive into the in-depth research.

Check the historical background of the poetry. The author might have been inspired to write a poem based on some events that occurred in those times or people he met. The lines you analyze may be generated by his reaction to some epoch events. All this information can be easily found online.

Choose poem theories you will support

In the variety of ideas the poem may convey, it is important to stick to only several most important messages you think the author wanted to share with the readers. Each of the listed ideas must be supported by the corresponding evidence as proof of your opinion.

The poetry analysis essay format allows elaborating on several theses that have the most value and weight. Try to build your writing not only on the pure facts that are obvious from the context but also your emotions and feelings the analyzed lines provoke in you.

How to Choose a Poem to Analyze?

If you are free to choose the piece of writing you will base your poem analysis essay on, it is better to select the one you are already familiar with. This may be your favorite poem or one that you have read and analyzed before. In case you face difficulties choosing the subject area of a particular poem, then the best way will be to focus on the idea you feel most confident about. In such a way, you would be able to elaborate on the topic and describe it more precisely.

Now, when you are familiar with the notion of the poetry analysis essay, it’s high time to proceed to poem analysis essay outline. Follow the steps mentioned below to ensure a brilliant structure to your creative assignment.

Best Poem Analysis Essay Topics

- Mother To Son Poem Analysis

- We Real Cool Poem Analysis

- Invictus Poem Analysis

- Richard Cory Poem Analysis

- Ozymandias Poem Analysis

- Barbie Doll Poem Analysis

- Caged Bird Poem Analysis

- Ulysses Poem Analysis

- Dover Beach Poem Analysis

- Annabelle Lee Poem Analysis

- Daddy Poem Analysis

- The Raven Poem Analysis

- The Second Coming Poem Analysis

- Still I Rise Poem Analysis

- If Poem Analysis

- Fire And Ice Poem Analysis

- My Papa’S Waltz Poem Analysis

- Harlem Poem Analysis

- Kubla Khan Poem Analysis

- I Too Poem Analysis

- The Juggler Poem Analysis

- The Fish Poem Analysis

- Jabberwocky Poem Analysis

- Charge Of The Light Brigade Poem Analysis

- The Road Not Taken Poem Analysis

- Landscape With The Fall Of Icarus Poem Analysis

- The History Teacher Poem Analysis

- One Art Poem Analysis

- The Wanderer Poem Analysis

- We Wear The Mask Poem Analysis

- There Will Come Soft Rains Poem Analysis

- Digging Poem Analysis

- The Highwayman Poem Analysis

- The Tyger Poem Analysis

- London Poem Analysis

- Sympathy Poem Analysis

- I Am Joaquin Poem Analysis

- This Is Just To Say Poem Analysis

- Sex Without Love Poem Analysis

- Strange Fruit Poem Analysis

- Dulce Et Decorum Est Poem Analysis

- Emily Dickinson Poem Analysis

- The Flea Poem Analysis

- The Lamb Poem Analysis

- Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night Poem Analysis

- My Last Duchess Poetry Analysis

Poem Analysis Essay Outline

As has already been stated, a poetry analysis essay is considered one of the most challenging tasks for the students. Despite the difficulties you may face while dealing with it, the structure of the given type of essay is quite simple. It consists of the introduction, body paragraphs, and the conclusion. In order to get a better understanding of the poem analysis essay structure, check the brief guidelines below.

Introduction

This will be the first section of your essay. The main purpose of the introductory paragraph is to give a reader an idea of what the essay is about and what theses it conveys. The introduction should start with the title of the essay and end with the thesis statement.

The main goal of the introduction is to make readers feel intrigued about the whole concept of the essay and serve as a hook to grab their attention. Include some interesting information about the author, the historical background of the poem, some poem trivia, etc. There is no need to make the introduction too extensive. On the contrary, it should be brief and logical.

Body Paragraphs

The body section should form the main part of poetry analysis. Make sure you have determined a clear focus for your analysis and are ready to elaborate on the main message and meaning of the poem. Mention the tone of the poetry, its speaker, try to describe the recipient of the poem’s idea. Don’t forget to identify the poetic devices and language the author uses to reach the main goals. Describe the imagery and symbolism of the poem, its sound and rhythm.

Try not to stick to too many ideas in your body section, since it may make your essay difficult to understand and too chaotic to perceive. Generalization, however, is also not welcomed. Try to be specific in the description of your perspective.

Make sure the transitions between your paragraphs are smooth and logical to make your essay flow coherent and easy to catch.

In a nutshell, the essay conclusion is a paraphrased thesis statement. Mention it again but in different words to remind the readers of the main purpose of your essay. Sum up the key claims and stress the most important information. The conclusion cannot contain any new ideas and should be used to create a strong impact on the reader. This is your last chance to share your opinion with the audience and convince them your essay is worth readers’ attention.

Problems with writing Your Poem Analysis Essay? Try our Essay Writer Service!

Poem Analysis Essay Examples

A good poem analysis essay example may serve as a real magic wand to your creative assignment. You may take a look at the structure the other essay authors have used, follow their tone, and get a great share of inspiration and motivation.

Check several poetry analysis essay examples that may be of great assistance:

- https://study.com/academy/lesson/poetry-analysis-essay-example-for-english-literature.html

- https://www.slideshare.net/mariefincher/poetry-analysis-essay

Writing Tips for a Poetry Analysis Essay

If you read carefully all the instructions on how to write a poetry analysis essay provided above, you have probably realized that this is not the easiest assignment on Earth. However, you cannot fail and should try your best to present a brilliant essay to get the highest score. To make your life even easier, check these handy tips on how to analysis poetry with a few little steps.

- In case you have a chance to choose a poem for analysis by yourself, try to focus on one you are familiar with, you are interested in, or your favorite one. The writing process will be smooth and easy in case you are working on the task you truly enjoy.

- Before you proceed to the analysis itself, read the poem out loud to your colleague or just to yourself. It will help you find out some hidden details and senses that may result in new ideas.

- Always check the meaning of words you don’t know. Poetry is quite a tricky phenomenon where a single word or phrase can completely change the meaning of the whole piece.

- Bother to double check if the conclusion of your essay is based on a single idea and is logically linked to the main body. Such an approach will demonstrate your certain focus and clearly elucidate your views.

- Read between the lines. Poetry is about senses and emotions – it rarely contains one clearly stated subject matter. Describe the hidden meanings and mention the feelings this has provoked in you. Try to elaborate a full picture that would be based on what is said and what is meant.

Write a Poetry Analysis Essay with HandmadeWriting

You may have hundreds of reasons why you can’t write a brilliant poem analysis essay. In addition to the fact that it is one of the most complicated creative assignments, you can have some personal issues. It can be anything from lots of homework, a part-time job, personal problems, lack of time, or just the absence of motivation. In any case, your main task is not to let all these factors influence your reputation and grades. A perfect way out may be asking the real pros of essay writing for professional help.

There are a lot of benefits why you should refer to the professional writing agencies in case you are not in the mood for elaborating your poetry analysis essay. We will only state the most important ones:

- You can be 100% sure your poem analysis essay will be completed brilliantly. All the research processes, outlines, structuring, editing, and proofreading will be performed instead of you.

- You will get an absolutely unique plagiarism-free piece of writing that deserves the highest score.

- All the authors are extremely creative, talented, and simply in love with poetry. Just tell them what poetry you would like to build your analysis on and enjoy a smooth essay with the logical structure and amazing content.

- Formatting will be done professionally and without any effort from your side. No need to waste your time on such a boring activity.

As you see, there are a lot of advantages to ordering your poetry analysis essay from HandmadeWriting . Having such a perfect essay example now will contribute to your inspiration and professional growth in future.

A life lesson in Romeo and Juliet taught by death

Due to human nature, we draw conclusions only when life gives us a lesson since the experience of others is not so effective and powerful. Therefore, when analyzing and sorting out common problems we face, we may trace a parallel with well-known book characters or real historical figures. Moreover, we often compare our situations with […]

Ethical Research Paper Topics

Writing a research paper on ethics is not an easy task, especially if you do not possess excellent writing skills and do not like to contemplate controversial questions. But an ethics course is obligatory in all higher education institutions, and students have to look for a way out and be creative. When you find an […]

Art Research Paper Topics

Students obtaining degrees in fine art and art & design programs most commonly need to write a paper on art topics. However, this subject is becoming more popular in educational institutions for expanding students’ horizons. Thus, both groups of receivers of education: those who are into arts and those who only get acquainted with art […]

Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Literature › Analysis of Allen Ginsberg’s Poems

Analysis of Allen Ginsberg’s Poems

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on July 14, 2020 • ( 1 )

“Howl,” the poem that carried Allen Ginsberg ( June 3, 1926 – April 5, 1997) into public consciousness as a symbol of the avant-garde artist and as the designer of a verse style for a postwar generation seeking its own voice, was initially regarded as primarily a social document. As Ginsberg’s notes make clear, however, it was also the latest specimen in a continuing experiment in form and structure. Several factors in Ginsberg’s life were particularly important in this breakthrough poem, written as the poet was approaching thirty and still drifting through a series of jobs, countries, and social occasions. Ginsberg’s father had exerted more influence than was immediately apparent. Louis Ginsberg’s very traditional, metrical verse was of little use to his son, but his father’s interest in literary history was part of Ginsberg’s solid grounding in prosody. Then, a succession of other mentors—including Williams, whose use of the American vernacular and local material had inspired him, and great scholars such as art historian Meyer Shapiro at Columbia, who had introduced him to the tenets of modernism from an analytic perspective—had enabled the young poet to form a substantial intellectual foundation.

In addition, Ginsberg was dramatically affected by his friendships with Kerouac, Cassady, Burroughs, Herbert Hunke, and other noteworthy denizens of a vibrant underground community of dropouts, revolutionaries, drug addicts, jazz musicians, and serious but unconventional artists of all sorts. Ginsberg felt an immediate kinship with these “angelheaded hipsters,” who accepted and celebrated eccentricity and regarded Ginsberg’s homosexuality as an attribute, not a blemish. Although Ginsberg enthusiastically entered into the drug culture that was a flourishing part of this community, he was not nearly as routed toward self-destruction as Burroughs or Hunke; he was more interested in the possibilities of visionary experience. His oft-noted “illuminative audition of William Blake’s voice simultaneous with Eternity-vision” in 1948 was his first ecstatic experience of transcendence, and he continued to pursue spiritual insight through serious studies of various religions—including Judaism and Buddhism—as well as through chemical experimentation.

His experiments with mind-altering agents (including marijuana, peyote, amphetamines, mescaline, and lysergic acid diethylamide, or LSD) and his casual friendship with some quasi-criminals led to his eight-month stay in a psychiatric institute.He had already experienced an unsettling series of encounters with mental instability in his mother, who had been hospitalized for the first time when he was three. Her struggles with the torments of psychic uncertainty were seriously disruptive events in Ginsberg’s otherwise unremarkable boyhood, but Ginsberg felt deep sympathy for his mother’s agony and also was touched by her warmth, love, and social conscience. Although not exactly a “red diaper baby,”Ginsberg had adopted a radical political conscience early enough to decide to pursue labor law as a college student, and he never wavered from his initial convictions concerning the excesses of capitalism. His passionate call for tolerance and fairness had roots as much in his mother’s ideas as in his contacts with the “lamblike youths” who were “slaughtered” by the demon Moloch: his symbol for the greed and materialism of the United States in the 1950’s. In conjunction with his displeasure with what he saw as the failure of the government to correct these abuses, he carried an idealized conception of “the lost America of love” based on his readings in nineteenth century American literature, Walt Whitman and Henry David Thoreau in particular, and reinforced by the political and social idealism of contemporaries such as Kerouac, Snyder, and McClure.

Ginsberg brought all these concerns together when he began to compose “Howl.” However, while the social and political elements of the poem were immediately apparent, the careful structural arrangements were not. Ginsberg found it necessary to explain his intentions in a series of notes and letters, emphasizing his desire to use Whitman’s long line “to build up large organic structures” and his realization that he did not have to satisfy anyone’s concept of what a poem should be, but could follow his “romantic inspiration” and simply write as he wished, “without fear.” Using what he called his “Hebraic- Melvillian bardic breath”—a rhythmic pattern similar to the cadences of the Old Testament as employed by Herman Melville—Ginsberg wrote a three-part prophetic elegy, which he described as a “huge sad comedy of wild phrasing.”

The first part of “Howl” is a long catalog of the activities of the “angelheaded hipsters” who were his contemporaries. Calling the bohemian underground of outcasts, outlaws, rebels, mystics, sexual deviants, junkies, and other misfits “the best minds of my generation”—a judgment that still rankles many social critics—Ginsberg produced image after image of the antics of “remarkable lamblike youths” in pursuit of cosmic enlightenment, “the ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night.” Because the larger American society had offered them little support, Ginsberg summarized their efforts by declaring that these people had been “destroyed by madness.” The long lines, most beginning with the word “who” (which was used “as a base to keep measure, return to and take off from again”), create a composite portrait that pulses with energy and excitement. Ginsberg is not only lamenting the destruction—or self-destruction—of his friends and acquaintances, but also celebrating their wild flights of imagination, their ecstatic illuminations, and their rapturous adventures. His typical line, or breath unit, communicates the awesome power of the experiences he describes along with their potential for danger. Ginsberg believed that by the end of the first section he had expressed what he believed “true to eternity” and had reconstituted “the data of celestial experience.”

Part 2 of the poem “names the monster of mental consciousness that preys” on the people he admires. The fear and tension of the Cold War, stirred by materialistic greed and what Ginsberg later called “lacklove,” are symbolized by a demon he calls Moloch, after the Canaanite god that required human sacrifice. With the name Moloch as a kind of “base repetition” and destructive attributes described in a string of lines beginning with “whose,” the second part of the poem reaches a kind of crescendo of chaos in which an anarchic vision of frenzy and disruption engulfs the world.

In part 3, “a litany of affirmation,” Ginsberg addresses himself to Solomon, a poet he knew from the Psychiatric Institute; he holds up Solomon as a kind of emblem of the victim-heroes he has been describing. The pattern here is based on the statement- counterstatement form of Christopher Smart’s Jubilate Agno (1939; as Rejoice in the Lamb , 1954), and Ginsberg envisioned it as pyramidal, “with a graduated longer response to the fixed base.” Affirming his allegiance to Solomon (and everyone like him), Ginsberg begins each breath unit with the phrase “I’m with you in Rockland” followed by “where . . .” and an exposition of strange or unorthodox behavior that has been labeled “madness” but that to the poet is actually a form of creative sanity. The poem concludes with a vision of Ginsberg and Solomon together on a journey to an America that transcends Moloch and madness and offers utopian possibilities of love and “true mental regularity.”

During the year that “Howl” was written, Ginsberg wondered whether he might use the same long line in a “short quiet lyrical poem.” The result was a poignant tribute to his “old courage teacher,” Whitman, which he called “A Supermarket in California,” and a meditation on the bounty of nature, “A Strange New Cottage in Berkeley.” He continued to work with his long-breath line in larger compositions as well, most notably the poem “America,” which has been accurately described by Charles Molesworth as “a gem of poly vocal satire and miscreant complaint.” This poem gave Ginsberg the opportunity to exercise his exuberant sense of humor and good-natured view of himself in a mock-ironic address to his country. The claim “It occurs to me that I am America” is meant to be taken as a whimsical wish made in self-deprecating modesty, but Ginsberg’s growing popularity through the last decades of the century cast it as prophetic as well.

Naomi Ginsberg died in 1956 after several harrowing episodes at home and in mental institutions, and she was not accorded a traditional orthodox funeral because a minyan (a complement of ten men to serve as witnesses) could not be found. Ginsberg was troubled by thoughts of his mother’s suffering and tormented by uncertainty concerning his own role as sometime caregiver for her. Brooding over his tangled feelings, he spent a night listening to jazz, ingesting marijuana and methamphetamine, and reading passages from an old bar mitzvah book. Then, at dawn, he walked the streets of the lower East Side in Manhattan, where many Jewish immigrant families had settled. A tangle of images and emotions rushed through his mind, organized now by the rhythms of ancient Hebrew prayers and chants. The poem that took shape in his mind was his own version of the Kaddish, the traditional Jewish service for the dead that had been denied to his mother. As it was formed in an initial burst of energy, he saw its goal as a celebration of her memory and a prayer for her soul’s serenity, an attempt to confront his own fears about death, and ultimately, an attempt to come to terms with his relationship to his mother. “Kaddish” begins in an elegiac mood, “Strange now to think of you gone,” and proceeds as both an elegy and a kind of dual biography. Details from Ginsberg’s childhood begin to take on a sinister aspect when viewed from the perspective of an adult with a tragic sense of existence. The course of his life’s journey from early youth and full parental love to the threshold of middle age is paralleled by Naomi’s life as it advances from late youth toward a decline into paranoia and madness. Ginsberg recalls his mother “teaching school, laughing with idiots, the backward classes—her Russian speciality,” then sees her in agony “one night, sudden attack . . . left retching on the tile floor.” The juxtaposition of images ranging over many years reminds him of his own mortality, compelling him to probe his subconscious mind to face some of the fears that he has suppressed about his mother’s madness. The first part of the poem concludes as the poet realizes that he will never find any peace until he is able to “cut through—to talk to you—” and finally to write her true history.

The central incident of the second section is a bus trip the twelve-year-old Ginsberg took with his mother to a clinic. The confusion and unpredictability of his mother’s behavior forced him to assume an adult’s role, for which he was not prepared. For the first time, he realizes that this moment marked the real end of childhood and introduced him to a universe of chaos and absurdity. As the narrative develops, the emergence of a nascent artistic consciousness, poetic perception, and political idealism is presented against a panorama of life in the United States in the late 1930’s. Realizing that his growth into the poet who is revealing this psychic history is closely intertwined with his mother’s decline, Ginsberg faces his fear that he was drawing his newfound strength from her as she failed. As the section concludes, he squarely confronts his mother’s illness, rendering her madness in disjointed scraps of conversation while using blunt physical detail as a means of showing the body’s collapse: an effective analogue for her simultaneous mental disorder. There is a daunting authenticity to these details, as Ginsberg speaks with utter candor about the most intimate and unpleasant subjects (a method he also employs in later poems about sexual contacts), confirming his determination to bury nothing in memory.

This frankness fuses Ginsberg’s recollections into a mood of great sympathy; he is moved to prayer, asking divine intervention to ease his mother’s suffering. Here he introduces the actual Hebrew words of the Kaddish, the formal service that had been denied his mother because of a technicality. The poet’s contribution is not only to create an appropriate setting for the ancient ritual but also to offer a testament to his mother’s most admirable qualities. As the second section ends, Ginsberg sets the power of poetic language to celebrate beauty against the pain of his mother’s last days. Returning to the elegiac mode (after Percy Bysshe Shelley’s “Adonais”), Ginsberg has a last vision of his mother days before her final stroke, associated with sunlight and giving her son advice that concludes, “Love,/ your mother,” which he acknowledges with his own tribute, “which is Naomi.”

The last part of the poem, “Hymmnn,” is divided into four sections. The first is a prayer for God’s blessing for his mother (and for all people); the second is a recitation of some of the circumstances of her life; the third is a catalog of characteristics that seem surreal and random but coalesce toward the portrait he is producing by composite images; and the last part is “another variation of the litany form,” ending the poem in a flow of “pure emotive sound” in which the words “Lord lord lord,” as if beseeching, alternate with the words “caw caw caw,” as if exclaiming in ecstasy.

By resisting almost all the conventional approaches to the loaded subject of motherhood, Ginsberg has avoided sentimentality and reached a depth of feeling that is overwhelming, even if the reader’s experience is nothing like the poet’s. The universality of the relationship is established by its particulars, the sublimity of the relationship by the revelation of the poet’s enduring love and empathy.

The publication of “Kaddish” ended the initial phase of Ginsberg’s writing life. “Howl” is a declaration of poetic intention, while “Kaddish” is a confession of personal necessity. With these two long, powerful works, Ginsberg completed the educational process of his youth and was ready to use his craft as a confident, mature artist. His range in the early 1960’s included the hilarious “I Am a Victim of Telephone,” which debunked his increasing celebrity, the gleeful jeremiad “Television Was a Baby Crawling Toward That Deathchamber,” the generously compassionate “Who Be Kind To,” and the effusive lyric “Why Is God Love, Jack?”Atribute to his mentor, “Death News,” describes his thoughts on learning of Williams’s demise.

Kral Majales