- Contractors

- Junior Professional

How to develop critical thinking skills in finance & accounting

Stephen Moir

Share this:.

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

When it comes to finance and accounting roles, employers are increasingly looking for problem solvers, not a number-crunchers. Over recent years, we have seen an increasing demand for people who can analyse and interpret data and think critically.

What is critical thinking.

A critical thinker is a problem solver. They are able to evaluate complex situations, weigh-up different options and reach logical (and often quite creative) conclusions.

Critical thinkers are highly-valued by employers as they innovate and make improvements, without taking unnecessary risks. Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand recently identified that it was in the top 10 attributes that will help you get noticed in the job market.

Why are critical thinking skills important?

Once you have learnt how to develop critical thinking skills you will be better able to add value to data, interpret trends within the business, understand how people and performance intersect and take-on broader commercial outlook that benefits the business.

How to develop critical thinking skills

Critical thinking comes naturally to some people, but it is also a skill than can be practiced. Here are some tips for how to develop your own critical thinking skills :

- Examine: Self-awareness is the foundation of critical thinking. It allows you to play to your strengths and address your weaknesses. Question how and why you do things the way you do.

- Analyse: Look for opportunities to grow and improve. Consider alternative solutions to the problems you encounter in your work.

- Explain: Clear communication is key. Get into the habit of talking through your reasoning and conclusions with colleagues.

- Innovate: Develop an independent mind-set. Find ways to think outside the box and challenge the status quo. Make sure your decisions are well-thought out. A critical thinker is logical as well as creative.

- Learn: Keep an open and well-oiled mind. Brush-up on your problem-solving skills by doing brain-teasers or trying to solve problems backwards. Keep up-to-date with professional learning opportunities . You may also need to unlearn past mindsets in order to grow and move forward.

How to apply critical thinking skills in your current role

Could you implement a new process or procedure that enhances performance or profitability? You might also consider volunteering for a new project or responsibility that gives you the opportunity to innovate and take on a new challenge. It’s a great way to broaden your skillset and gain exposure to other parts of the business.

Surround yourself with other critical thinkers in the organisation and work together towards achieving a problem-solving culture. Ask questions, and always look for opportunities for continual learning.

Changing roles to develop critical thinking skills

At Moir Group, we are passionate about finding the right cultural fit between people and the organisations they work with. If you are a critical thinker, it’s worth looking for a stimulating work environment that encourages innovation and non-conformist thinking when considering your next role.

How to demonstrate critical thinking skills at an interview

During an interview, use examples from your past experiences to demonstrate your problem-solving abilities. Show that you can be analytical, weigh-up pros and cons, consider other view points and be creative in your solutions. Clearly articulating your thought process is key.

Sometimes an interviewer will ask you to simplify the complex as a way of determining your clarity of thought. For example: “How would you explain the state of the economy to a kindergarten child?” In instances like these, the focus will be on how you explain your reasoning, rather than achieving a ‘right’ answer. Learn more here.

If you’re looking to take that next step in your career, we can help. Get in touch with us here .

2 Responses to “How to develop critical thinking skills in finance & accounting”

Hi Stephen,

The above is very useful and very valuable for employers. However my understanding of critical thinking is slightly different from above. I recently listened to a course in critical thinking by Professor Steven Novella of Yale School of Medicine. To keep it simple it is to do with assessing the veracity of views and statements made by oneself, others and media being constantly aware of the many biases, the flaws and fabrications of memory, half truths, unspoken truths, and even lies. So it becomes key to adopt an inquisitive mindset, to look for external evidence that supports argument and not just wishful or hopeful thinking.

Just wanting to add to the debate as this is a really important area.

Hi Richard,

We are pleased that found this article useful. Thanks for your sharing your thoughts about critical thinking.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Moir Group acknowledges Traditional Owners of Country throughout Australia and recognises the continuing connection to lands, waters and communities. We pay our respect to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures; and to Elders past and present and encourage applications from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and people of all cultures, abilities, sex, and genders.

This site uses cookies to store information on your computer. Some are essential to make our site work; others help us improve the user experience. By using the site, you consent to the placement of these cookies. Read our privacy policy to learn more.

- EXTRA CREDIT

Guide students toward better critical thinking

Learn about the stages of critical thinking to help accounting students develop skills needed for professional success..

- Accounting Education

When I first began focusing on the development of student critical thinking skills in the early 1990s, I discussed ideas for a research project with the partner of a CPA firm. I recall being quite surprised when the partner stated, “We can’t afford to have our people sitting around, thinking all day.” I don’t believe that a partner would say the same thing today. While productivity no doubt continues to be important, today’s accountants are increasingly called on to address new types of problems in complex environments.

Unfortunately, as critical thinking research indicates, most college students graduate with only some critical thinking skills . This means that they also lack the critical thinking skills required by the accounting profession — which is expected to require even more critical thinking ability in the future.

The bottom line is that we need to help our accounting students close the gap between their current critical thinking skills and the skills they will need for professional success. How can we do this?

In this article series, I will provide specific recommendations for helping students improve their critical thinking within accounting courses. In this introductory article, I will provide a working definition of critical thinking and describe the “stages” of critical thinking that most college students will pass through. In subsequent articles, I will explain two of the stages in greater detail, discuss why students at each stage address critical thinking tasks in a specific way, and offer suggestions for creating more effective learning activities. These activities are designed to help students progress from one stage of critical thinking to the next.

How should we define ‘critical thinking’?

There is no universally accepted definition of critical thinking. Because different accounting educators are likely to have different ideas about this topic, I will begin with a definition. The Foundation for Critical Thinking provides several definitions of critical thinking , including the following description that is highly consistent with what is required of a professional accountant:

A well-cultivated critical thinker:

- raises vital questions and problems, formulating them clearly and precisely;

- gathers and assesses relevant information, using abstract ideas to interpret it effectively;

- comes to well-reasoned conclusions and solutions, testing them against relevant criteria and standards;

- thinks openmindedly within alternative systems of thought, recognizing and assessing, as need be, their assumptions, implications, and practical consequences; and

- communicates effectively with others in figuring out solutions to complex problems.

Critical thinking is, in short, self-directed, self-disciplined, self-monitored, and self-corrective thinking. It presupposes assent to rigorous standards of excellence and mindful command of their use. It entails effective communication and problem-solving abilities and a commitment to overcome our native egocentrism and sociocentrism.

Notice that this description holds the critical thinker to very high standards. It not only includes the process of analyzing information to form a logical conclusion, but it also requires the thinker to be self-aware, to test ideas against standards, to communicate and work effectively with others, and to seek improvement in light of inherent personal weaknesses.

The big takeaway for accounting educators is that critical thinking requires students to not only apply accounting knowledge correctly, but also to learn how to deal with ambiguous and complex problems and to adopt a mindset that enhances the quality of their work.

The stages of cognitive development

Not all accounting students start or finish college with the same level of critical thinking ability. In fact, most undergraduates have reached one of three stages of cognitive development. At each of these stages, students hold different underlying beliefs about knowledge. In turn, these beliefs influence how students respond to tasks that require critical thinking and can hinder the development of their critical thinking skills. By directly addressing students’ underlying beliefs, accounting educators can increase both students’ motivation to learn critical thinking skills and the effectiveness of the learning methods they use.

The three stages can be described as follows:

- Little/no critical thinking (“The Confused Fact-Finder”)

- Some critical thinking (“The Biased Jumper”)

- Emergent critical thinking: (“The Perpetual Analyzer”)

These are the most common stages students exhibit throughout the undergraduate experience. About half of first-year students will be in the first stage, and most graduating students will have reached the second stage. Only a minority of students will have reached the third stage at the time of graduation, but educators should still be aware of it because it represents the next step they can help students achieve.

In the table below, I briefly summarize these three thinking patterns, the beliefs about knowledge that undergird them, and key recommendations for the focus of teaching and learning. In upcoming articles in this series, I will address each of the three patterns of thinking in greater detail and present specific teaching and learning ideas to help your students develop stronger critical thinking skills.

(Note: These patterns are based on Stages 3, 4, and 5 in the reflective judgment model developed by Karen Kitchener and P.M. King. For details, see my freely available Faculty Handbook: Steps for Better Thinking . For a copy, send an email to [email protected] .)

Remember — the accounting profession is evolving rapidly. In the past, it was satisfactory to focus accounting courses primarily on technical knowledge and theory. Over time, accounting education has evolved to be more practical, focusing on hands-on and project-based educational models. What is needed in the future is a greater emphasis on making business decisions in an ambiguous, nonlinear environment. The evolution of the CPA will depend on how readily accounting professionals can achieve the ambitious definition of critical thinking described earlier.

The purpose of this series is to help you explore student thinking, and how critical thinking is taught and learned, to enable you to help your students thrive in today’s complex professional and business environment.

Susan Wolcott, CPA, CMA, Ph.D. , is a founder of WolcottLynch, which conducts research and develops educational resources for critical thinking development. She has taught accounting courses at seven universities and is currently a visiting professor at the Indian School of Business. To comment on this article or to suggest an idea for another article, contact senior editor Courtney Vien at [email protected] .

Where to find June’s flipbook issue

The Journal of Accountancy is now completely digital.

SPONSORED REPORT

Manage the talent, hand off the HR headaches

Recruiting. Onboarding. Payroll administration. Compliance. Benefits management. These are just a few of the HR functions accounting firms must provide to stay competitive in the talent game.

FEATURED ARTICLE

2023 tax software survey

CPAs assess how their return preparation products performed.

This site uses cookies, including third-party cookies, to improve your experience and deliver personalized content.

By continuing to use this website, you agree to our use of all cookies. For more information visit IMA's Cookie Policy .

Change username?

Create a new account, forgot password, sign in to myima.

Multiple Categories

Improving Critical Thinking Skills

November 01, 2021

By: Sonja Pippin , Ph.D., CPA ; Brett Rixom , Ph.D., CPA ; Jeffrey Wong , Ph.D., CPA

Whether working with financial statements, analyzing operational and nonfinancial information, implementing machine learning and AI processes, or carrying out many of their other varied responsibilities, accounting and finance professionals need to apply critical thinking skills to interpret the story behind the numbers.

Critical thinking is needed to evaluate complex situations and arrive at logical, sometimes creative, answers to questions. Informed judgments incorporating the ever-increasing amount of data available are essential for decision making and strategic planning.

Thus, creatively thinking about problems is a core competency for accounting and finance professionals—and one that can be enhanced through effective training. One such approach is through metacognition. Training that employs a combination of both creative problem solving (divergent thinking) and convergence on a single solution (convergent thinking) can lead financial professionals to create and choose the best interpretations for phenomena observed and how to best utilize the information going forward. Employees at any level in the organization, from newly hired staff to those in the executive ranks, can use metacognition to improve their critical assessment of results when analyzing data.

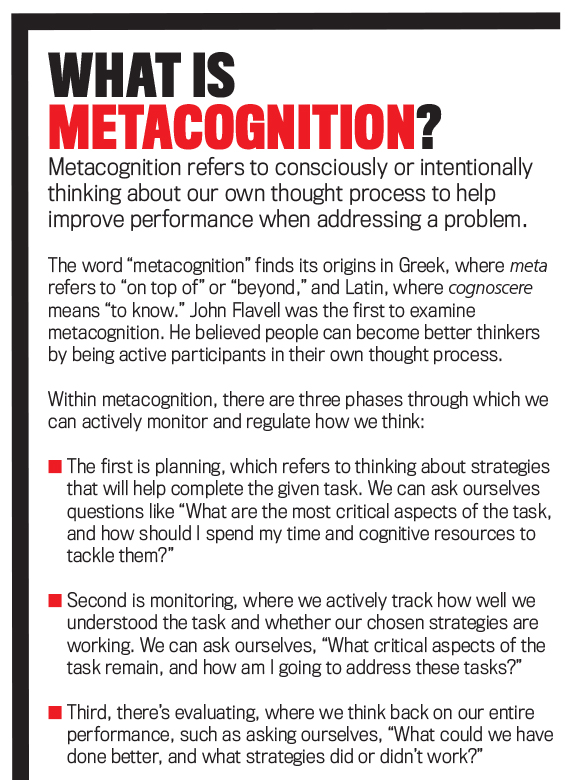

THINKING ABOUT THINKING

Metacognition refers to individuals’ ability to be aware, understand, and purposefully guide how to think about a problem (see “What Is Metacognition?”). It’s also been described as “thinking about thinking” or “knowing about knowing” and can lead to a more careful and focused analysis of information. Metacognition can be thought about broadly as a way to improve critical thinking and problem solving.

In their article “Training Auditors to Perform Analytical Procedures Using Metacognitive Skills,” R. David Plumlee, Brett Rixom, and Andrew Rosman evaluated how different types of thinking can be applied to a variety of problems, such as the results of analytical procedures, and how those types of thinking can help auditors arrive at the correct explanation for unexpected results that were found ( The Accounting Review , January 2015). The training methods they describe in their study, based on the psychological research examining metacognition, focus on applying divergent and convergent thinking.

While they employed settings most commonly encountered by staff in an audit firm, their approach didn’t focus on methods used solely by public accountants. Therefore, the results can be generalized to professionals who work with all types of financial and nonfinancial data. It’s particularly helpful for those conducting data analysis.

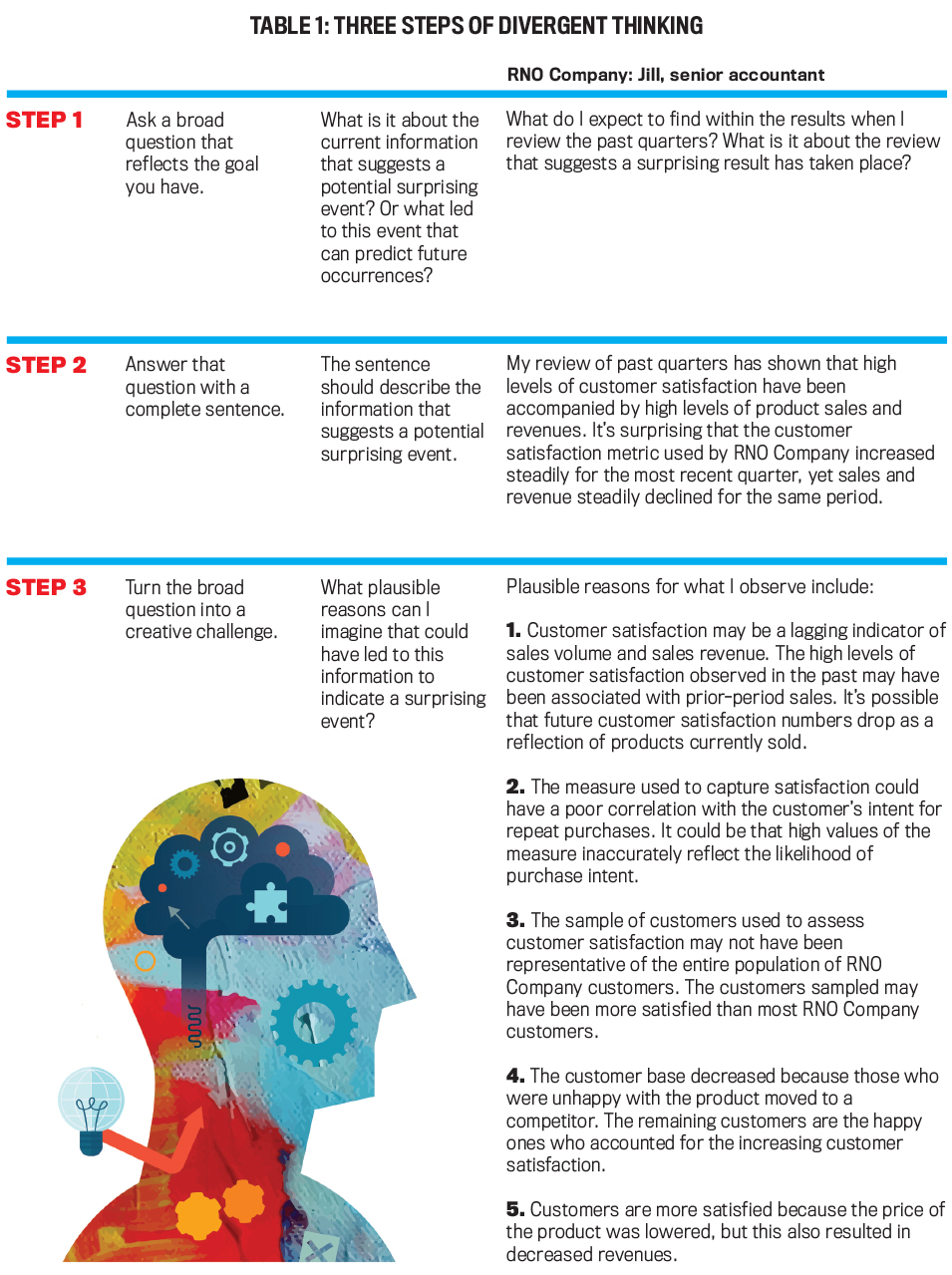

Their approach involved a sequential process of divergent thinking followed by convergent thinking. Divergent thinking refers to creating multiple reasons about what could be causing the surprising or unusual patterns encountered when analyzing data before a definitive rationale is used to inform what actions to take or strategy to use. Here’s an example of divergent thinking:

The customer satisfaction metric employed by RNO Company has increased steadily for the quarter, yet its sales numbers and revenue have declined steadily for the same period. Jill, a senior accountant, conducted ratio and trend analyses and found some of the results to be unusual. To apply divergent thinking, Jill would think of multiple potential reasons for this surprising result before removing any reason from consideration.

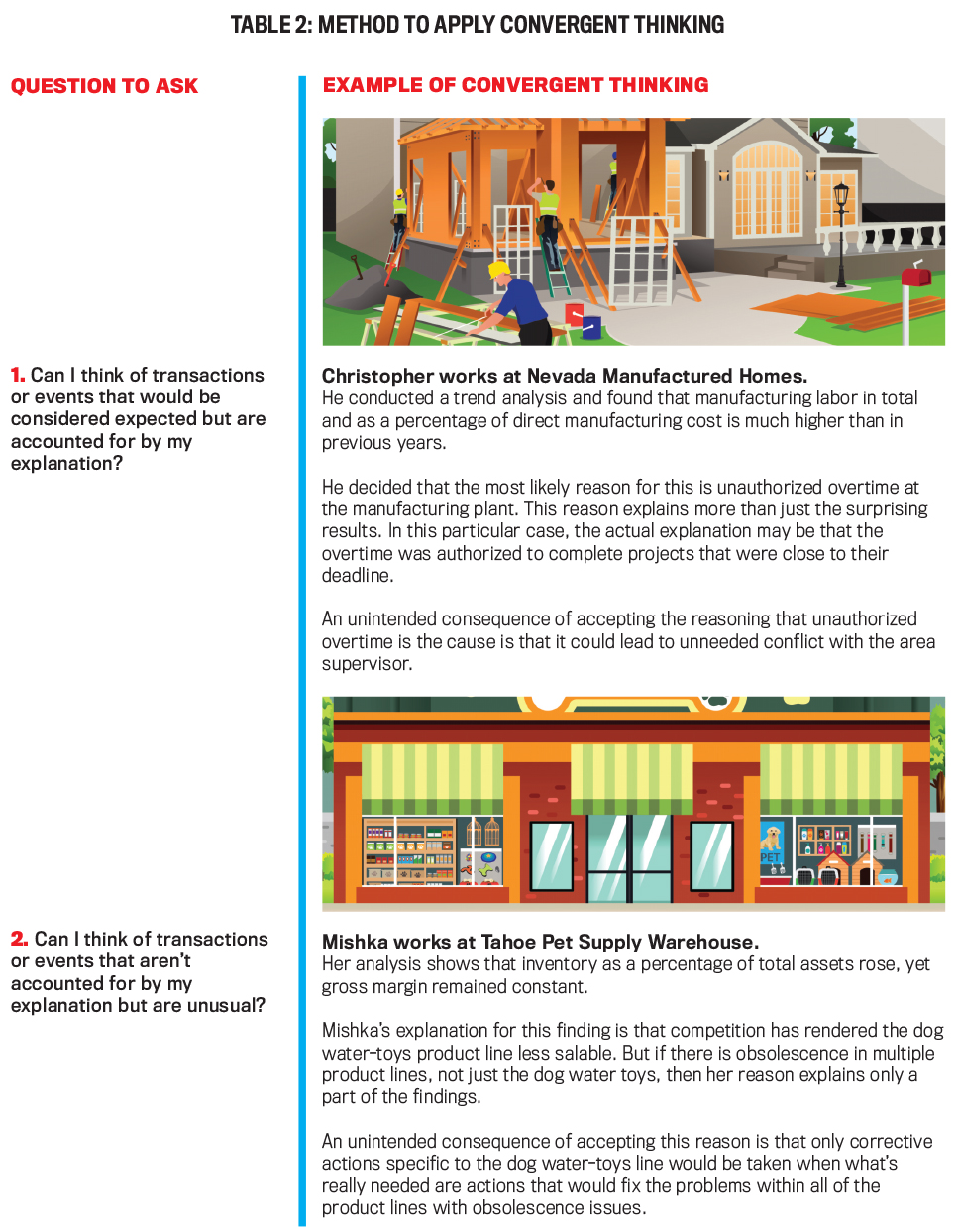

Convergent thinking is the process of finding the best explanation for the surprising results so that potential actions can be explored accordingly. The process consists of narrowing down the different reasons by ensuring the only reasons that are kept for consideration are ones that explain all of the surprising patterns seen in the results without explaining more than what is needed. In this way, actions can be taken to address the heart of any problems found instead of just the symptoms. On the other hand, if the surprising result is beneficial to an organization, it can make it easier to take the correct actions to replicate the benefit in other aspects of the business. Here’s an example of convergent thinking:

Washoe, Inc.’s customer satisfaction metric has increased steadily for the quarter, yet sales numbers and revenue have steadily declined for the same period. Roberto found this result to be surprising. After employing divergent thinking to identify 10 potential reasons for this result, such as “the reason that customers seem more satisfied is that the price of goods has been reduced, which also explains the reduction in sales revenue.” To apply convergent thinking, Roberto reviewed each reason that best fit. If the reason doesn’t explain the unusual results satisfactorily, then it will either be modified or discarded. For example, the reduced price of goods doesn’t explain all of the results—specifically, the decrease in units sold—so it needs to either be eliminated as a possible explanation or modified until it does explain all the results.

Exploring strategic or corrective actions based on reasons that completely explain the unusual results increases the chance of correctly addressing the actual issue behind the surprising result. Also, by making sure that the reason doesn’t contain extraneous details, unneeded actions can be avoided.

It’s important to note that a sequential process is required for these types of thinking to be most effective. When encountering a surprising or unexpected result during data analysis, accounting professionals must first focus strictly on divergent thinking—thinking about potential reasons—before using convergent thinking to choose a reason that best explains the surprising result. If convergent thinking is used before divergent thinking is completed, it can lead to reasons being picked simply because they came to mind right away.

LEARNING THE PROCESS

Improving divergent and convergent thinking can benefit employees at any level of an organization. Newer professionals who don’t have as much technical knowledge and experience to draw upon may be more likely to focus on the first explanation that comes to mind (“premature convergent thinking”) without fully considering all of the potential reasons for the surprising results. Experienced individuals such as CFOs and controllers have more technical knowledge and practical experience to rely on, but it’s possible these seasoned employees fall into habits and follow past patterns of thought without fully exploring potential causes for surprising results.

Instructing all accounting professionals on how to think about surprising results can help them have a more complete understanding of the issues at hand that will help guide actions taken in the future. It can lead to a more creative approach when analyzing information and ultimately to better problem solving.

When teaching employees to use divergent and convergent thinking, the goal is to get them to focus on what should be done once they identify information that suggests a surprising result has occurred. The first step is to learn how to properly use divergent thinking to create a set of plausible explanations more likely to contain the actual reason for the surprising results. There’s a three-step method that individuals can follow (see Table 1):

- Ask a broad question that reflects the goal you have: For instance, what is it about the current information that suggests a potential surprising event? Or what led to this event that can help predict future occurrences?

- Answer that question with a complete sentence: Be sure the answer includes a description of the information that suggests a potential surprising event.

- Turn the broad question into a creative challenge: Identify the plausible reasons that could have led to the indications of a surprising event.

Once employees have a good grasp of how to use divergent thinking, the next step is to instruct them in the proper use of convergent thinking, which involves choosing the best possible reason from the ones identified during the divergent thinking process. Potential reasons need to be narrowed down by removing or modifying those that either don’t fully explain the surprising results or that overexplain the results.

Two simple questions can help individuals screen each of the possible explanations generated in the divergent thinking process (see Table 2):

- Can I think of transactions or events that would be considered expected but are accounted for by my explanation?

- Can I think of transactions or events that aren’t accounted for by my explanation but are unusual?

The first question is designed for an individual to think about whether there are other events outside of the current issue that fit the explanation: “Does the explanation also address phenomena that aren’t related to or outside the scope of the surprising result that’s being studied?” If the answer is “yes,” then this is a case of overexplanation. Consider, for example, a scenario involving an increase in bad debts. Relaxing credit requirements may explain the increase, but they would also explain a growth in sales and falling employee morale due to working massive amounts of overtime to make products for sale.

The second question is designed to think about whether an explanation only accounts for part of the phenomenon being observed: “Does the explanation address only part of what’s being observed while leaving other important details unexplained?” If the answer is “yes,” then it’s an under-explanation. For example, consider a decline in sales. An economic downturn at the same time as the decline may be a possible explanation, but it might only be part of the problem. A drop in product quality or a drop in demand due to obsolescence could also be causing sales to decline.

If the answer to either screening question is “yes,” then the explanation needs to be discarded from consideration or modified to better address the concern. In the case of over-explanation, the reason is too general and may lead to action areas where none is needed while still not addressing the actual issue. For underexplanation, the reason is incomplete because it accounts for only a portion of the phenomenon observed, thus action may only address a symptom and not the actual root problem.

If the answer to both questions is “no,” then the explanation is viable. The chosen reason neither overexplains nor underexplains the issue at hand, making it more likely that the recommended solution or plan of action based on that reason will be more successful at addressing the actual cause of the issue.

Divergent and convergent thinking are two distinct processes that work in conjunction with each other to arrive at potential reasons for the results they observe. Yet, as previously noted, the two ways of thinking must be conducted separately and sequentially in order to obtain optimal results. Divergent thinking must be applied first in order to achieve a diverse set of potential reasons. This will maximize the probability of generating a feasible reason that explains the results correctly. After the set of potential reasons has been generated using the divergent thinking approach, convergent thinking should be used to methodically remove or modify the reasons that don’t fit with the surprising results.

If both divergent thinking and convergent thinking are done simultaneously, premature convergence can lead to a less-than-optimal reason being chosen, which may lead to taking the wrong course of action. Thus, it’s important with training to instruct employees in the use of both divergent thinking and convergent thinking and to use the types of thinking sequentially.

ORGANIZATIONAL TRAINING

Learning to apply divergent and convergent thinking can require a substantial time commitment. The process we’ve described here is designed to enhance critical thinking and problem-solving skills. It outlines a general approach that doesn’t provide specific guidance on the best methods to analyze data or complete a task but rather focuses on successful methods to think of a diverse set of reasons for any surprising results and then how to choose the best explanation for that result in order to be able to recommend the most appropriate actions or solutions.

Individuals can practice the approach we’ve described on their own, but each organization will likely have its own preferred way to approach the analyses. Plumlee, et al., used training modules in their study that could be employed in a concerted effort by a company, with supervisors training their employees. We estimate that a basic training session would take about two hours. Complete training with practice and feedback would require about four hours—which could grow longer with even more for intensive training.

One area where this training could be very effective in helping employees is data analytics. In the past decade, an increasing amount of accounting and financial work involves or relies on data analysis. Data availability has increased exponentially, and companies use or have developed software that generates sophisticated analytical results.

Typical data analysis procedures accounting professionals might be called on to perform include things such as ratio and trend analyses, which compare financial and nonfinancial data over time and against industry information to examine whether results achieved are in line with expectations for strategic actions. Additionally, analyses are forward-looking when performance measures examined are leading indicators.

In order to perform data analytics effectively, accounting professionals must exercise sufficient judgment to critically assess the implications of any surprising results that are found. The quality of judgments and understanding the best ways to conduct and interpret the information uncovered by data analytics have typically been a function of time spent on the job along with training. At the same time, however, it’s commonplace that many of these analyses are performed by newer professionals.

Training in metacognition will help these employees more effectively and creatively reach conclusions about what they’ve observed in their analysis. Since the method discussed provides general instruction, each organization can customize the approach to best fit its own operations, strategies, and goals. Implementing a training program can be worth the investment given the importance of critical thinking throughout the process of evaluating operating results. Avoiding potential failures with interpreting results that could be prevented would seem to warrant the consideration of metacognitive training.

About the Authors

November 2021

- Strategy, Planning & Performance

- Business Acumen & Operations

- Decision Analysis

- Operational Knowledge

Publication Highlights

Lessons from an Agile Product Owner

Explore more.

Copyright Footer Message

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet

Critical Thinking in Professional Accounting Practice: Conceptions of Employers and Practitioners

Cite this chapter.

- Samantha Sin ,

- Alan Jones &

- Zijian Wang

4922 Accesses

5 Citations

Over the past three decades or so it has become commonplace to lament the failure of universities to equip accounting graduates with the attributes and skills or abilities required for professional accounting practice, particularly as the latter has had to adapt to the demands of a rapidly changing business environment. With the aid of academics, professional accounting bodies have developed lists of competencies, skills, and attributes considered necessary for successful accounting practice. Employers have on the whole endorsed these lists. In this way “critical thinking” has entered the lexicon of both accountants and their employers, and when employers are asked to rank a range of named competencies in order of importance, critical thinking or some roughly synonymous term is frequently ranked highly, often at the top or near the top of their list of desirables (see, for example, Albrecht and Sack 2000). Although practical obstacles, such as content-focused curricula, have emerged to the inclusion of critical thinking as a learning objective in tertiary-level accounting courses, the presence of these obstacles has not altered “the collective conclusion from the accounting profession that critical thinking skills are a prerequisite for a successful accounting career and that accounting educators should assist students in the development of these skills” (Young and Warren 2011, 859). However, a problem that has not yet been widely recognized may lie in the language used to survey accountants and their employers, who may not be comfortable or familiar with the abstract and technicalized pedagogical discourse, for instance, the use of the phrase “developing self-regulating critical reflective capacities for sustainable feedback,” in which much skills talk is couched.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Similar content being viewed by others

Literacy Strategies and Instructional Modalities in Introductory Accounting

Developing Ethical Sensitivity in Future Accounting Practitioners: The Case of a Dialogic Learning for Final-Year Undergraduates

Educating for Professional Responsibility: From Critical Thinking to Deliberative Communication, or Why Critical Thinking Is Not Enough

Accounting Education Change Commission. 1990. “Objectives of Education for Accountants: Position Statement Number One.” Issues in Accounting Education 5 (2): 307–312.

Google Scholar

Albrecht, W., and Sack, R. 2000. “Accounting Education: Charting the Course through a Perilous Future.” Sarasota, FL: American Accounting Association.

American Accounting Association. 1986. “Future Accounting Education: Preparing for the Expanding Profession, Bedford Report.” Sarasota, FL: American Accounting Association.

American Institute of Certified Public Accountants. 1999. “ CPA Vision Project: 2011 and Beyond.” New York: American Institute of Certified Public Accountants.

Baril, C., Cunningham, B., Fordham, D., Gardner, R., and Wolcott, S. 1998. “Critical Thinking in the Public Accounting Profession: Aptitudes and Attitudes.” Journal of Accounting Education 16 (3–4): 381–406.

Article Google Scholar

Barnett, R. 1997. Higher Education: A Critical Business . Buckingham: Society for Research into Higher Education and the Open University Press.

Bereiter, C., and Scardamalia, M. 1987. The Psychology of Written Composition . Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Big Eight Accounting Firms. 1989. “Perspectives on Education: Capabilities for Success in the Accounting Profession (White Paper).” New York: American Accounting Association.

Birkett, W. 1993. “Competency Based Standards for Professional Accountants in Australia and New Zealand.” Melbourne: ASCPA and ICAA.

Bloom, B., Engelhart, M., Furst, E., Hill, W., and Krathwohl, D. 1956. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: Handbook I: Cognitive Domain . Vol. 19: New York: David McKay.

Bui, B., and Porter, B. 2010. “The Expectation-Performance Gap in Accounting Education: An Exploratory Study.” Accounting Education: An International Journal 19 (1–2): 23–50.

Camp, J., and Schnader, A. 2010. “Using Debate to Enhance Critical Thinking in the Accounting Classroom: The Sarbanes-Oxley Act and US Tax Policy.” Issues in Accounting Education 25 (4): 655–675.

CPA Australia and the Institute of Chartered Accountants in Australia. 2012. “Professional Accreditation Guidelines for Australian Accounting Degrees.” Melbourne and Sydney: CPA Australia and the Institute of Chartered Accountants in Australia.

Craig, R., and McKinney, C. 2010. “A Successful Competency-Based Writing Skills Development Programme: Results of an Experiment.” Accounting Education: An International Journal 19 (3): 257–278.

Deal, K. 2004. “The Relationship between Critical Thinking and Interpersonal Skills: Guidelines for Clinical Supervision.” The Clinical Supervisor 22 (2): 3–19.

Doney, L., Lephardt, N., and Trebby, J. 1993. “Developing Critical Thinking Skills in Accounting Students.” Journal of Education for Business 68 (5): 297–300.

Dunn, D., and Smith, R. 2008. “Writing as Critical Thinking.” In Teaching Critical Thinking in Psycholog y: A Handbook of Best Practices , edited by D. S. Dunn, J. S. Halonen, and R. A. Smith, 1st ed. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. 163–174.

Chapter Google Scholar

Entwistle, N. 1994. Teaching and Quality of Learning: What Can Research and Development Offer to Policy and Practice in Higher Education . London: Society for Research into Higher Education.

Facione, P. 1990. Critical Thinking: A Statement of Expert Consensus for Purposes of Educational Assessment and Instruction, “The Delphi Report.” Millbrae, CA: American Philosophical Association, The California Academic Press.

Facione, P., Facione, N., and Giancario, C. 1997. Professional Judgement and the Disposition towards Critical Thinking . Millbrae, CA: Californian Academic Press.

Facione, P., Sanchez, C. A., Facione, N. C., and Gainen, J. 1995. “The Disposition toward Critical Thinking.” The Journal of General Education 44 (1): 1–25.

Flower, L., and Hayes, J. 1984. “Images, Plans, and Prose: The Representation of Meaning in Writing.” Written Communication 1 (1): 120–160.

Freeman, M., Hancock, P., Simpson, L., Sykes, C., Petocz, P., Densten, I., and Gibson, K. 2008. “Business as Usual: A Collaborative and Inclusive Investigation of the Existing Resources, Strengths, Gaps and Challenges to Be Addressed for Sustainability in Teaching and Learning in Australian University Business Faculties.” Scoping Report, Australian Business Deans Council. http://www.olt.gov.au /project-business-usual-collaborative-sydney-2006.

Galbraith, M. 1998. Adult Learning Methods: A Guide for Effective Instruction . Washington, DC: ERIC Publications.

Giancarlo, C., and Facione, P. 2001. “A Look across Four Years at the Disposition toward Critical Thinking among Undergraduate Students.” The Journal of General Education 50 (1): 29–55.

Hancock, P., Howieson, B., Kavanagh, M., Kent, J., Tempone, I., and Segal, N. 2009. “Accounting for the Future: More Than Numbers, Final Report.” Strawberry Hills: Australian Learning and Teaching Council Ltd. http://www.altc.edu.au .

Hayes, J., and Flower, L. 1987. “On the Structure of the Writing Process.” Topics in Language Disorders 7 (4): 19–30.

Hyland, K. 2005. “Stance and Engagement: A Model of Interaction in Academic Discourse.” Discourse Studies 7 (2): 173–192.

Jackson, M., Watty, K., Yu, L., and Lowe, L. 2006. “Assessing Students Unfamiliar with Assessment Practices in Australian Universities, Final Report.” Strawberry Hills: Australian Learning and Teaching Council Ltd.

Jones, A. 2010. “Generic Attributes in Accounting: The Significance of the Disciplinary Context.” Accounting Education: An International Journal 19 (1–2): 5–21.

Jones, A., and Sin, S. 2003. Generic Skills in Accounting: Competencies for Students and Graduates . Sydney: Pearson/Prentice Hall.

Jones, A., and Sin, S. 2004. “Integrating Language with Content in First Year Accounting: Student Profiles, Perceptions and Performance.” In Integrating Content and Language: Meeting the Challenge of a Multilingual Higher Education , edited by R. Wilkinsoned. Maastricht: Maastricht University Press.

Jones, A., and Sin, S. 2013. “Achieving Professional Trustworthiness: Communicative Expertise and Identity Work in Professional Accounting Practice.” In Discourses of Ethics , edited by C. Candlin and J. Crichtoned. Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kavanagh, M., and Drennan, L. 2008. “What Skills and Attributes Does an Accounting Graduate Need? Evidence from Student Perceptions and Employer Expectations.” Accounting and Finance 48 (2): 279–300.

Kimmel, P. 1995. “A Framework for Incorporating Critical Thinking into Accounting Education.” Journal of Accounting Education 13 (3): 299–318.

King, P., and Kitchener, K. 2004. “Reflective Judgment: Theory and Research on the Development of Epistemic Assumptions through Adulthood.” Educational Psychologist 39 (1): 5–18.

Kurfiss, J. 1988. Critical Thinking: Theory, Research, Practice and Possibilities . Washington: ASHE-Eric Higher Education Report No. 2, Associate for the Study of Higher Education.

Kurfiss, J. 1989. “Helping Faculty Foster Students’ Critical Thinking in the Disciplines.” New Directions for Teaching and Learning 37 (1): 41–50.

Lucas, U. 2008. “Being “Pulled up Short”: Creating Moments of Surprise and Possibility in Accounting Education.” Critical Perspectives on Accounting 19 (3): 383–403

Menary, R. 2007. “Writing as Thinking.” Language Sciences 29 (5): 621–632.

Metlay, D., and Sarewitz, D. 2012. “Decision Strategies for Addressing Complex, “Messy” Problems.” The Bridge on Social Sciences and Engineering Practice 42 (3): 6–16.

Mezirow, J. 2000. Learning as Transformation: Critical Perspectivesona Theory in Progress . The Jossey-Bass Higher and Adult Education Series, Washington, DC: ERIC Publications.

Morgan, G. 1988. “Accounting as Reality Construction: Towards a New Epistemology for Accounting Practice.” Accounting, Organizations and Society 13 (5): 477–485.

Partnership for Public Service and Institute for Public Policy Implementation. 2007. The Best Places to Work in the Federal Government . Washington, DC: American University.

Paul, R. 1989. Critical Thinking Handbook: High School. A Guide for Redesigning Instruction . Washington, DC: ERIC Publications.

Sarangi, S., and Candlin, C. 2010. “Applied Linguistics and Professional Practice: Mapping a Future Agenda.” Journal of Applied Linguistics and Professional Practice 7 (1): 1–9.

Serrat, O. 2011. Critical Thinking . Washington, DC: Asian Development Bank.

Simon, H. 1974. “The Structure of Ill Structured Problems.” Artificial Intelligence 4 (3): 181–201.

Sin, S. 2010. “Considerations of Quality in Phenomenographic Research.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods no. 9 (4): 305–319.

Sin, S. 2011. An Investigation of Practitioners’ and Students’ Conceptions of Accounting Work . Linköping: Linköping University Press.

Sin, S., Jones, A., and Petocz, P. 2007. “Evaluating a Method of Integrating Generic Skills with Accounting Content Based on a Functional Theory of Meaning.” Accounting and Finance 47 (1): 143–163.

Sin, S., Reid, A., and Dahlgren, L. 2011. “The Conceptions of Work in the Accounting Profession in the Twenty-First Century from the Experiences of Practitioners.” Studies in Continuing Education 33 (2): 139–156.

Tempone, I., and Martin, E. 2003. “Iteration between Theory and Practice as a Pathway to Developing Generic Skills in Accounting.” Accounting Education: An International Journal 12 (3): 227–244.

Thompson, J., and Tuden, A. 1959. “Strategies, Structures, and Processes of Organizational Decision.” In Comparative Studies in Administration edited by J. Thompson, P. Hammond, R. Hawkes, B. Junker, and A. Tudened. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. 195–216.

van Peursem, K. 2005. “Conversations with Internal Auditors: The Power of Ambiguity.” Managerial Auditing Journal 20 (5): 489–512.

Wang, F. 2007. Conceptions of Critical Thinking Skills in Accounting from the Perspective of Accountants in Their First Year of Experience in the Profession , Macquarie University Honours Thesis.

Watson, T. 2004. “Managers, Managism, and the Tower of Babble: Making Sense of Managerial Pseudojargon.” International Journal of the Sociology of Language (166): 67–82.

White, L. 2003. Second Language Acquisition and Universal Grammar . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Young, M., and Warren, D. 2011. “Encouraging the Development of Critical Thinking Skills in the Introductory Accounting Courses Using the Challenge Problem Approach.” Issues in Accounting Education 26 (4): 859–881.

Download references

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Copyright information.

© 2015 Martin Davies and Ronald Barnett

About this chapter

Sin, S., Jones, A., Wang, Z. (2015). Critical Thinking in Professional Accounting Practice: Conceptions of Employers and Practitioners. In: Davies, M., Barnett, R. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Thinking in Higher Education. Palgrave Macmillan, New York. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137378057_26

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137378057_26

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, New York

Print ISBN : 978-1-349-47812-5

Online ISBN : 978-1-137-37805-7

eBook Packages : Palgrave Education Collection Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Do you have the right personality for College?

- Accounting & Payroll

- Business & Administration

- Community & Education

- Graphic & Web Design

- Healthcare Programs

- Technology & Development

- Construction & Inspection

- Hospitality & Tourism

- Legal & Immigration

- Calgary Central

- Calgary Genesis Centre

- Edmonton South

- Edmonton West

- Medicine Hat

- Winnipeg South

- Winnipeg North

- CALGARY GENESIS CENTRE (NEW)

- International Students

- Request Info

Why Critical Thinking Is Important for Careers in Accounting

Critical thinking skills are an asset in every industry, but some might be surprised to know that this type of thinking is especially important for success in accounting careers. Accounting is not all about crunching numbers, as one might think. Accounting professions have evolved, with advancements in technology and changes within various industries. Today, those in the accounting professions need to be able to implement strategies of critical thinking in order to analyze information, determine problems or areas of improvement, and develop logical solutions.

The moment when you apply critical thinking skills to a career in accounting, you’ll ensure a successful future for yourself in the industry. Here’s what critical thinking looks like, and why it’s important for accounting professionals.

What You Should Know That Defines Critical Thinking

Critical thinking is an innovative way of thinking in which someone assesses a problem by raising important questions, and wondering what can be improved upon. A critical thinker gathers new information that can be used to analyze and inform unique strategies to address an issue at hand. Critical thinkers are open-minded and accepting of unconventional approaches, rather than developing attachments to traditional schools of thought.

The work of those with careers in accounting increasingly takes place in more complex environments, and accounting professionals are tackling new kinds of issues. By using critical thinking, an accounting professional looks beyond the numbers and conventional processes in place to determine new strategies, and increase the effectiveness of workflows.

Why Critical Thinking is Important for Accounting Professions

Today, accounting professions look a lot different than they did twenty, or even ten years ago. Those in the accounting professions are often in charge of updating the financial frameworks of an organization to fit with the changes brought on by advancements in technology. Thanks to the integration of automated processes and calculations, the accounting industry has shifted from a focus on spreadsheets and specificities to the practical, hands-on implementation of innovative accounting strategies. Accounting professionals may be focused on making predictions or helping businesses to create more profitable policies, rather than mechanically crunching an organization’s numbers in line with traditional processes.

Critical thinking is an important skill for those with careers in accounting

Today, professionals with accounting training backgrounds must be able to apply creative solutions to problems that businesses are facing, helping them to keep up with competitors and improve the profitability of their business model. Employers increasingly value accounting professionals who can apply creative thinking skills and problem-solving capabilities in order to come up with solutions based on adept analysis of data and systems knowledge.

Improving Your Critical Thinking Skills

There are a few ways that professionals seeking accounting careers can improve their critical thinking skills. When looking at a situation or a problem, someone can first apply critical thinking by having a good understanding of the goal before attempting to develop solutions. This can be achieved simply by asking: “What is the desired outcome?” Next, critical thinking can be improved upon by becoming aware of inherent biases or attachment to traditional ways of accomplishing a task. By understanding that these biases and understandings have their limits, an individual will be more likely to be able to recognize when something could be improved upon.

Lastly, individuals should conduct research on possible solutions, discussing and collaborating with others who would be able to contribute a unique perspective. By brainstorming and exploring all possible avenues of thought, an individual will prepare themselves to think critically about the situation at hand. Are you ready to apply your critical thinking skills to an accounting course ?

Explore the Academy of Learning Career College’s program options today.

Explore Career Training Programs

- Accounting & Payroll

- Business & Administration

- Community & Education

- Graphic & Web Design

- Hospitality & Tourism

- Technology & Development

You May Also Like

Essential payroll clerk skills you’ll learn in career college, reducing your margin of error after payroll administration training, where can you work with a computerized accounting diploma.

Comments are closed.

- Integrated Learning System (ILS)

- Student Experience

- Schedule Appointment

- Financial Assistance

- Student Success Stories

- Individual Courses

Campus Locations

- Edmonton Downtown

- Partner Program

- National Website

- Career Advice

- Community Services

- Hospitality

© 2024 Academy of Learning Career College. National Website | Terms of Use | Privacy Policy

- Soft skills

- What is a credential?

- Why do a credential?

- How do credentials work?

- Selecting your level

- How will I be assessed?

- Benefits for professionals

- Benefits for organisations

- Benefits for postgraduates

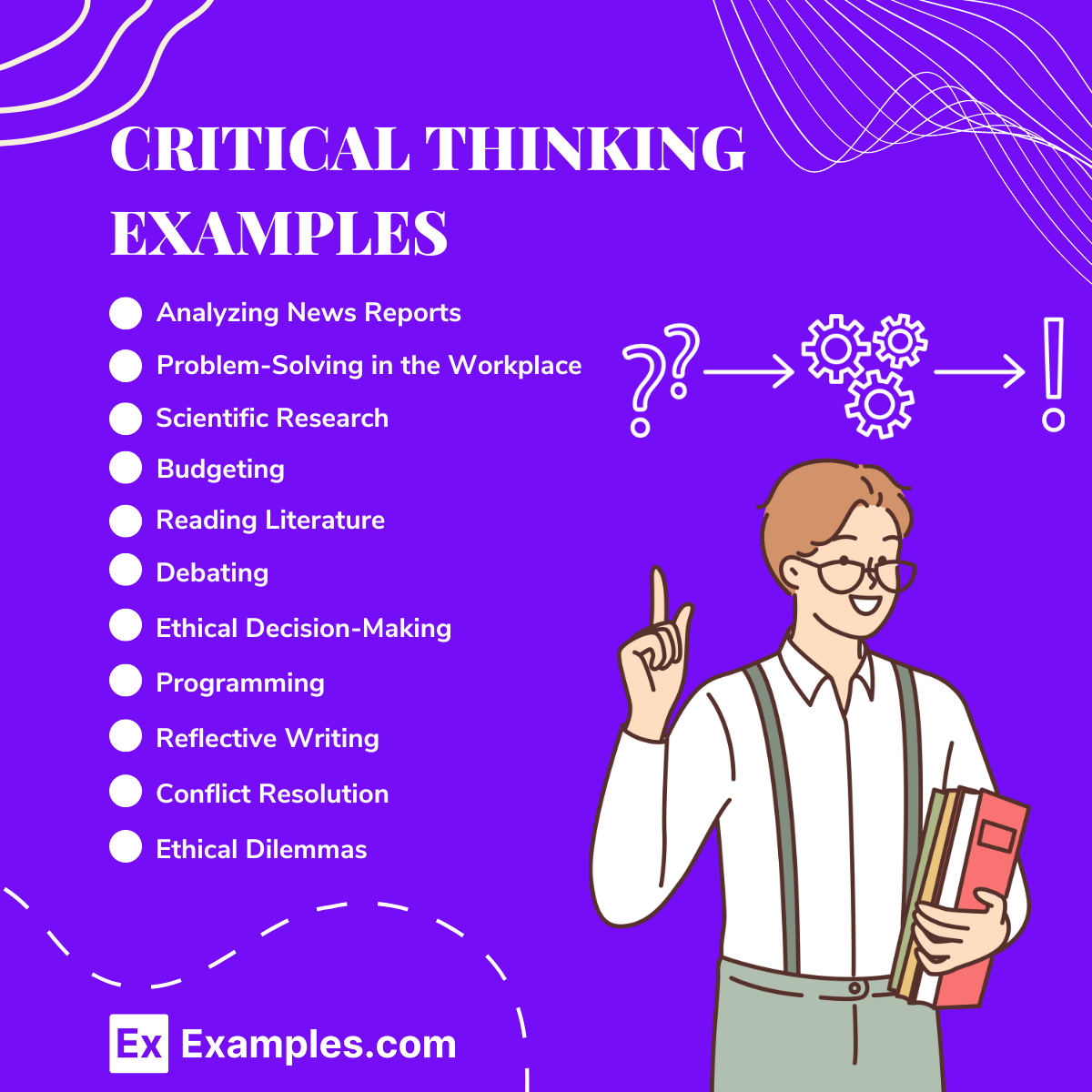

4 examples of critical thinking that show its importance

Posted on May 17, 2019

Critical thinking is the ability to make informed decisions by evaluating several different sources of information objectively. As such, critical thinkers possess many other essential skills, including analysis, creativity, problem-solving and empathy.

Employers have always found critical thinking extremely valuable – after all, no boss wants to constantly handhold their employees because they are unable to make their own judgements about how best to proceed.

However, all too often people talk about critical thinking in theory, while never really explaining what that knowledge looks like in practice. As a result, many have never really understood the importance of thinking critically in business. Which is why we’ve created this list of examples of how critical thinking skills are used in the workplace.

Critical thinking example 1: Problem-solving

Imagine you’re at work. Someone, potentially your manager, presents you with a problem. You immediately go off and start looking for solutions. But do you take a step back first to analyse the situation, gathering and reviewing as much information as possible? Do you ask each of the different people involved what their opinion is, or how the problem affects their and the broader business’ day-to-day? And do you decide to run with the first solution you find, or take the time to come up with a number of different options and test each before making your final judgement?

While a lot of people may think they have problem-solving skills, if you aren’t taking the time to follow the above steps, you’re not really being a critical thinker. As such, you may not find the best solution to your problem.

Employing critical thinking skills when solving a problem is absolutely essential – what you decide could impact hundreds of people and even have an effect on the financial health of the business. If you’re not looking at it from multiple perspectives, you’re never going to be able to understand the full impact of a decision.

Critical thinking example 2: Risk assessment

Economic uncertainty, climate change, political upheaval … risks abound in the modern workforce, and it’s an employee’s critical thinking skills that will enable a business to assess these hazards and act on them.

Risk assessment occurs in a number of different scenarios. For example, a construction company has to identify all potential hazards on a building site to ensure its employees are working as safely as possible. Without this analysis, there could be injuries or even deaths, causing severe distress to the workforce and negatively impacting the company’s reputation (not to mention any of the legal consequences).

In the finance industry, organisations have to assess the potential impacts of new legislation on the way they work, as well as how the new law will affect their clients. This requires critical thinking skills such as analysis, creativity (imagining different scenarios arising from the legislation) and problem-solving (finding a way to work with the new legislation). If the financial institution in this example doesn’t utilise these critical thinking skills, it could end up losing profit or even suffering legal consequences from non-compliance.

Critical thinking example 3: Data analysis

In the digital age critical thinking has become even more, well, critical. While machines have the ability to collate huge amounts of information and reproduce it in a readable format, the ability to analyse and act on this data is still a skill only humans possess.

Take an accountant. Many of their more mundane tasks have passed to technology. Accounting platforms have the ability to produce profit and loss statements, prepare accounts, issue invoices and create balance sheets. But that doesn’t mean accountants are out of a job. Instead, they can now focus their efforts on adding real value to their clients by interpreting the data this technology has collated and using it to give recommendations on how to improve. On a wider scale, they can look at historic financial trends and use this data to forecast potential risks or stumbling blocks moving forward.

The core skill in all of these activities is critical thinking – being able to analyse a large amount of information and draw conclusions in order to make better decisions for the future. Without these critical thinkers, an organisation may easily fall behind its competitors, who are able to respond to risks more easily and provide more value to clients.

Critical thinking example 4: Talent hiring

One of the most important aspects of the critical thinking process is being able to look at a situation objectively. This also happens to be crucial when making a new hire. Not only do you have to analyse a large number of CVs and cover letters in order to select the best candidates from a pool, you also need to be able to do this objectively. This means not giving preferential treatment to someone because of their age, gender, origin or any other factor. Given that bias is often unconscious, if you can demonstrate that you are able to make decisions like this with as little subjectivity as possible, you can show that you possess objectivity – a key critical thinking skill.

Hiring the right talent is essential for a company’s survival. You don’t want to lose out on top candidates because of someone’s unconscious bias, showing just how essential this type of knowledge is in business.

Prove your critical thinking skills with professional practice credentials

As you can see, critical thinking skills are incredibly important to organisations across all industries. In today’s constantly changing world, businesses need people who can adapt and apply their thinking to new situations. No matter where you’re at in your career, you need critical thinking skills to complete your everyday tasks effectively, and when it comes to getting your next promotion, they’re vital.

But the problem with critical thinking skills, just like all soft skills, is that they are hard to prove. While you can show your employer you have a certificate in computer programming, you can’t say the same of critical thinking.

Until now. Enter Deakin’s professional practice credentials. These are university-level micro-credentials that provide an authoritative assessment of your proficiencies in a range of areas. This includes critical thinking, as well as a number of other soft skills, such as communication, innovation, teamwork and self-management.

Find out more about our credentials here or contact a member of the team today to find out how you can prove your critical thinking skills and take your career to the next level.

This site uses cookies to store information on your computer. Some are essential to make our site work; others help us improve the user experience. By using the site, you consent to the placement of these cookies. Read our privacy policy to learn more.

- Educator Resources

- Meet the Requirements

- Maximize Your Education

- Pay for College

- AICPA Legacy Scholarships

- AICPA CPA Exam Scholarship

- AICPA Accounting Doctoral Fellowship

- AICPA Accounting Scholars Leadership Workshop (ASLW)

- Search Other Scholarships

- Exam Overview

- What is CPA Evolution?

- How to Apply

- Prepare for the Exam

- Prep Course Reviews

- Exam Diaries

- Find Your First Job

- Resumes & Interviewing

- Skill Development

- Plan Your Career

- CPA Profiles

- State Requirements

- International Applicants

- Exam & Licensure Center

- Career Options

- Salary Information

- Accounting is Tech

- CPA Pipeline Toolkit

- Bank On It Game

- Career Launchpad

Critical Thinking Resources

These resources aid accounting educators to strengthen teaching techniques to invoke and heighten critical thinking abilities in students..

Students should learn to recognize uncertainties/ambiguities/risks/opportunities in decision making that do not always provide an absolute or the one “correct” business/accounting solution. These resources focus on the foundational elements of teaching and learning critical thinking skills to aid in student cognitive abilities development through a scaffold approach. As students’ progress through their academic program, the rigor employed in course exercises, cases and projects should increase and acquisition of ability should thereby evolve as well. The emphasis on critical thinking in coursework should lend to altering and enhancing student expectations about accounting as a major and profession. Additionally, heightening this key competency will aid students in gaining comfort and confidence to pursue a career in the thrillingly complex and multi-faceted world of accounting.

NEW: FACULTY GUIDE - How to help students become better critical thinkers Get recommendations for designing your accounting course to accelerate critical thinking development.

How to help students who are ‘Perpetual Analyzers’ Identifying the students who logically and qualitatively evaluate the evidence and assumptions that underpin different perspectives.

How to identify your students’ stage of cognitive development Determine which stage of cognitive development your students have reached, and presents observations and suggestions for teaching critical thinking.

Guide students toward better critical thinking Learn about the stages of critical thinking to help accounting students develop skills needed for professional success.

How to help students who are 'Confused Fact-Finders' Because Confused Fact-Finders believe that all problems can be solved correctly, they are highly resistant to the idea that they must reach their own conclusions.

A problem-based learning project for accounting classes Students work in groups to refine a driving question.

Practical ways to develop students' critical thinking skills Try these tips and exercises to improve your students' analytical abilities

Critical Thinking Reference Flyer Reference flyer to illustrate the critical thinking model

- • Glossary

- • Terms & Conditions

- • Privacy Policy

- • Contact & Feedback

Existing Login

By selecting 'Keep me logged in.' you consent to saving your session in accordance with our privacy policy. For shared devices (such as a public computer) we recommend that you do not select this option.

I Forgot My Password

Join the AICPA as a FREE Student Affiliate Member

Gain access to exclusive content, AICPA benefits and scholarship opportunities. Available to full or part time high school or university students.

Register as an accounting faculty member or professional

Gain access to the Academic Resource Database, educator webinars and more to support you in building the CPA pipeline.

Already have an account? Sign In

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, critical thinking in accounting education: processes, skills and applications.

Managerial Auditing Journal

ISSN : 0268-6902

Article publication date: 1 October 1997

Explains that many prestigious bodies, including the American Assembly of Collegiate Schools of Business and the Accounting Change Commission, have asked accounting educators to improve their students’ critical thinking skills. Suggests that the literature contains few examples of how to apply such skills in an accounting environment and how to teach such skills as efficiently as possible. Explains and provides examples of such critical thinking skills. Shows how to incorporate such skills in the classroom.

- Thinking styles

Reinstein, A. and Bayou, M.E. (1997), "Critical thinking in accounting education: processes, skills and applications", Managerial Auditing Journal , Vol. 12 No. 7, pp. 336-342. https://doi.org/10.1108/02686909710180698

Copyright © 1997, MCB UP Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

10 Accounting Analytical Skills and How To Improve Them

Discover 10 Accounting Analytical skills along with some of the best tips to help you improve these abilities.

Analytical skills are important for anyone in the accounting field. Being able to analyze data and financial statements is essential for making sound decisions and providing accurate information. In this guide, we’ll discuss what accounting analytical skills are, why they’re important and how you can improve your own analytical skills.

Financial Modeling

Variance analysis, financial reporting, consolidation, forecasting, financial analysis, management accounting, tax accounting.

Financial modeling is a process that uses data to create a model that represents a company’s financial situation. This model can be used to make predictions about future events, such as how much cash a company will have at the end of the year. Financial modeling is an important skill for accountants because it allows them to make better decisions about how to allocate company resources.

Variance analysis is a process used to identify and explain differences between budgeted and actual results. It can be used to compare any two sets of data, such as sales revenue versus expenses, or inventory levels versus sales.

Variance analysis is an important analytical tool because it can help identify trends, make adjustments and improve future performance. By understanding the reasons for variances, you can make better decisions about how to allocate resources and improve your business.

Financial reporting is the process of collecting, analyzing and summarizing financial data for use by external parties such as investors, regulators and the general public. Financial reporting is important because it provides a basis for making decisions about whether to invest in a company, whether to provide credit, and whether to regulate a company.

Financial reporting also provides a basis for comparing companies and their performance. For example, investors can use financial reporting to compare the profitability, liquidity and leverage of different companies. Financial reporting is a complex process that requires financial analysts to have strong analytical skills and a good understanding of accounting principles.

Consolidation is an important accounting analytical skill because it allows you to combine data from multiple sources into a single report. This can be helpful when you’re trying to get a big-picture view of a company’s finances. Consolidation can also be used to compare different companies’ financial data, such as when you’re trying to determine which company is the most profitable.

Forecasting is an important skill for accountants because it allows them to provide valuable insight into future trends. This information can be used to make decisions about budgeting, planning and investing. Forecasting can be done using different methods, such as trend analysis, regression analysis and econometrics.

Explain why Critical Thinking is an important problem-solving skill. Critical thinking is an important problem-solving skill because it allows you to analyze a problem, think creatively about possible solutions, and make a decision based on evidence. Critical thinking requires you to be open-minded, objective and reflective. You need to be able to see both sides of an issue, consider different points of view, and think creatively about possible solutions.

Budgeting is an important skill for accountants because it allows them to plan and control spending for their clients. By creating a budget, accountants can help their clients stay on track with their spending and save money. Additionally, budgeting can help accountants identify areas where their clients can save money, such as by reducing their monthly spending on groceries or by switching to a cheaper cell phone plan.

Budgeting is a valuable skill for accountants because it allows them to better understand their clients’ finances and help them plan for the future. Additionally, budgeting can help accountants identify areas where their clients can save money, which can lead to a better understanding of their clients’ finances and help them plan for the future.

GAAP is an important accounting analytical skill because it is used to ensure that financial statements are accurate and can be relied upon by investors, creditors and other stakeholders. GAAP is a set of standards and procedures that must be followed when preparing and presenting financial information. GAAP is designed to provide consistency and comparability in financial reporting.

Financial analysis is the process of reviewing and analyzing financial data to make decisions about how to allocate resources. It involves reviewing financial statements, such as the balance sheet, income statement and cash flow statement, to identify trends, make projections and determine the financial health of a company.

Financial analysis is an important skill for accountants and other financial professionals. They use financial analysis to help their clients make decisions about how to invest their money, whether to take on debt or make other financial decisions. Financial analysis is also used by companies to make decisions about how to allocate resources, such as whether to invest in new equipment or expand their operations.

Management accounting is the process of gathering, analyzing and reporting financial information to assist in making business decisions. This information is used by managers to make decisions about how to allocate resources, such as money, time and personnel. Management accounting also helps managers track the performance of the business by providing key financial metrics, such as net profit, gross profit, return on investment and break-even analysis.

Management accounting is an important skill for anyone in a management role, as it can help them make better decisions and track the performance of the business.

Tax accounting is the process of preparing tax returns for individuals and businesses. It involves calculating the tax owed or refunded, based on the individual or business’s income, deductions and credits. Tax accounting is a critical skill for accountants, as they must be able to understand the tax code and apply it to individual and business tax returns.

Tax accounting is a complex process, and accountants must be able to work quickly and accurately to ensure that tax returns are filed on time. Additionally, tax accountants must be able to communicate effectively with clients to explain the tax code and answer any questions.

How to Improve Your Accounting Analytical Skills

1. Use accounting software There are many different types of accounting software available, and using them can be a great way to improve your analytical skills. Many accounting software programs have features that can help you track your finances, generate reports and even create financial models.

2. Take an accounting class If you want to improve your analytical skills, taking an accounting class can be a great way to learn more about the subject. Accounting classes can teach you the basics of financial accounting, as well as more advanced topics like financial modeling and variance analysis.

3. Use online resources There are many online resources that can help you improve your accounting analytical skills. Websites like AccountingCoach.com offer free accounting lessons, while sites like CFI.com offer more advanced resources like financial modeling templates and guides.

4. Read accounting books In addition to online resources, there are many accounting books that can help you improve your analytical skills. Some popular accounting books include Financial Accounting For Dummies and Managerial Accounting For Dummies.

5. Get a job in accounting One of the best ways to improve your accounting analytical skills is to get a job in accounting. Working in accounting will give you first-hand experience dealing with financial reports, budgets and other accounting tasks.

10 Ethical Skills and How To Improve Them

10 patient interaction skills and how to improve them, you may also be interested in..., what does a warehouse lead do, what does an engineering technologist do, what does an educational technologist do, what does a director of support services do.

41+ Critical Thinking Examples (Definition + Practices)

Critical thinking is an essential skill in our information-overloaded world, where figuring out what is fact and fiction has become increasingly challenging.

But why is critical thinking essential? Put, critical thinking empowers us to make better decisions, challenge and validate our beliefs and assumptions, and understand and interact with the world more effectively and meaningfully.

Critical thinking is like using your brain's "superpowers" to make smart choices. Whether it's picking the right insurance, deciding what to do in a job, or discussing topics in school, thinking deeply helps a lot. In the next parts, we'll share real-life examples of when this superpower comes in handy and give you some fun exercises to practice it.

Critical Thinking Process Outline

Critical thinking means thinking clearly and fairly without letting personal feelings get in the way. It's like being a detective, trying to solve a mystery by using clues and thinking hard about them.

It isn't always easy to think critically, as it can take a pretty smart person to see some of the questions that aren't being answered in a certain situation. But, we can train our brains to think more like puzzle solvers, which can help develop our critical thinking skills.

Here's what it looks like step by step:

Spotting the Problem: It's like discovering a puzzle to solve. You see that there's something you need to figure out or decide.

Collecting Clues: Now, you need to gather information. Maybe you read about it, watch a video, talk to people, or do some research. It's like getting all the pieces to solve your puzzle.

Breaking It Down: This is where you look at all your clues and try to see how they fit together. You're asking questions like: Why did this happen? What could happen next?

Checking Your Clues: You want to make sure your information is good. This means seeing if what you found out is true and if you can trust where it came from.

Making a Guess: After looking at all your clues, you think about what they mean and come up with an answer. This answer is like your best guess based on what you know.

Explaining Your Thoughts: Now, you tell others how you solved the puzzle. You explain how you thought about it and how you answered.

Checking Your Work: This is like looking back and seeing if you missed anything. Did you make any mistakes? Did you let any personal feelings get in the way? This step helps make sure your thinking is clear and fair.

And remember, you might sometimes need to go back and redo some steps if you discover something new. If you realize you missed an important clue, you might have to go back and collect more information.

Critical Thinking Methods

Just like doing push-ups or running helps our bodies get stronger, there are special exercises that help our brains think better. These brain workouts push us to think harder, look at things closely, and ask many questions.

It's not always about finding the "right" answer. Instead, it's about the journey of thinking and asking "why" or "how." Doing these exercises often helps us become better thinkers and makes us curious to know more about the world.

Now, let's look at some brain workouts to help us think better:

1. "What If" Scenarios

Imagine crazy things happening, like, "What if there was no internet for a month? What would we do?" These games help us think of new and different ideas.

Pick a hot topic. Argue one side of it and then try arguing the opposite. This makes us see different viewpoints and think deeply about a topic.

3. Analyze Visual Data

Check out charts or pictures with lots of numbers and info but no explanations. What story are they telling? This helps us get better at understanding information just by looking at it.

4. Mind Mapping

Write an idea in the center and then draw lines to related ideas. It's like making a map of your thoughts. This helps us see how everything is connected.

There's lots of mind-mapping software , but it's also nice to do this by hand.

5. Weekly Diary

Every week, write about what happened, the choices you made, and what you learned. Writing helps us think about our actions and how we can do better.

6. Evaluating Information Sources

Collect stories or articles about one topic from newspapers or blogs. Which ones are trustworthy? Which ones might be a little biased? This teaches us to be smart about where we get our info.

There are many resources to help you determine if information sources are factual or not.

7. Socratic Questioning

This way of thinking is called the Socrates Method, named after an old-time thinker from Greece. It's about asking lots of questions to understand a topic. You can do this by yourself or chat with a friend.

Start with a Big Question:

"What does 'success' mean?"

Dive Deeper with More Questions:

"Why do you think of success that way?" "Do TV shows, friends, or family make you think that?" "Does everyone think about success the same way?"

"Can someone be a winner even if they aren't rich or famous?" "Can someone feel like they didn't succeed, even if everyone else thinks they did?"

Look for Real-life Examples:

"Who is someone you think is successful? Why?" "Was there a time you felt like a winner? What happened?"

Think About Other People's Views:

"How might a person from another country think about success?" "Does the idea of success change as we grow up or as our life changes?"

Think About What It Means:

"How does your idea of success shape what you want in life?" "Are there problems with only wanting to be rich or famous?"

Look Back and Think:

"After talking about this, did your idea of success change? How?" "Did you learn something new about what success means?"

8. Six Thinking Hats

Edward de Bono came up with a cool way to solve problems by thinking in six different ways, like wearing different colored hats. You can do this independently, but it might be more effective in a group so everyone can have a different hat color. Each color has its way of thinking:

White Hat (Facts): Just the facts! Ask, "What do we know? What do we need to find out?"

Red Hat (Feelings): Talk about feelings. Ask, "How do I feel about this?"

Black Hat (Careful Thinking): Be cautious. Ask, "What could go wrong?"

Yellow Hat (Positive Thinking): Look on the bright side. Ask, "What's good about this?"

Green Hat (Creative Thinking): Think of new ideas. Ask, "What's another way to look at this?"

Blue Hat (Planning): Organize the talk. Ask, "What should we do next?"

When using this method with a group:

- Explain all the hats.

- Decide which hat to wear first.

- Make sure everyone switches hats at the same time.

- Finish with the Blue Hat to plan the next steps.

9. SWOT Analysis

SWOT Analysis is like a game plan for businesses to know where they stand and where they should go. "SWOT" stands for Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats.

There are a lot of SWOT templates out there for how to do this visually, but you can also think it through. It doesn't just apply to businesses but can be a good way to decide if a project you're working on is working.

Strengths: What's working well? Ask, "What are we good at?"

Weaknesses: Where can we do better? Ask, "Where can we improve?"

Opportunities: What good things might come our way? Ask, "What chances can we grab?"

Threats: What challenges might we face? Ask, "What might make things tough for us?"

Steps to do a SWOT Analysis:

- Goal: Decide what you want to find out.

- Research: Learn about your business and the world around it.

- Brainstorm: Get a group and think together. Talk about strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats.