Essay on The Dignity of Labour with Outlines for Students

Essay on dignity of work with outline for 2nd year, f.a, fsc, b.a, bsc & b.com.

Here is an essay on The Dignity of Labour with Outline for the students of Graduation. However, Students of 2nd year, F.A, FSc, B.A, BSC and Bcom can prepare this essay for their exams. This essay has been taken from Functional English by (Imran Hashmi) Azeem Academy. You can write the same essay under the title, The Dignity of Work Essay or Essay on the Dignity of Work or Dignity of Work or Labour in Islam Essay. First of all, try to understand and learn the Outline of this essay to make it easy to remember the points of the essay. You can see more essay examples by going to English Essay Writing .

The Dignity of Labour Essay Outline:

- By labour, we generally mean work done by hands.

- There is nothing shameful in becoming a skill-worker.

- In Islam all human being are equal. Islam does not allow distinction on the basis of profession.

- In Islam hones work of all kinds is worth respecting.

- Unfortunately, we ignore the bright example set by our Holy Prophet (Peace be Upon Him) and consider manual work as undignified.

- In the advanced countries, the major cause of the development is that dignity of labour has got its due importance.

- In the less developed countries like Pakistan, the major cause of backwardness is that we have misused the concept of dignity of labour.

- We should give equal status to the labour class in society.

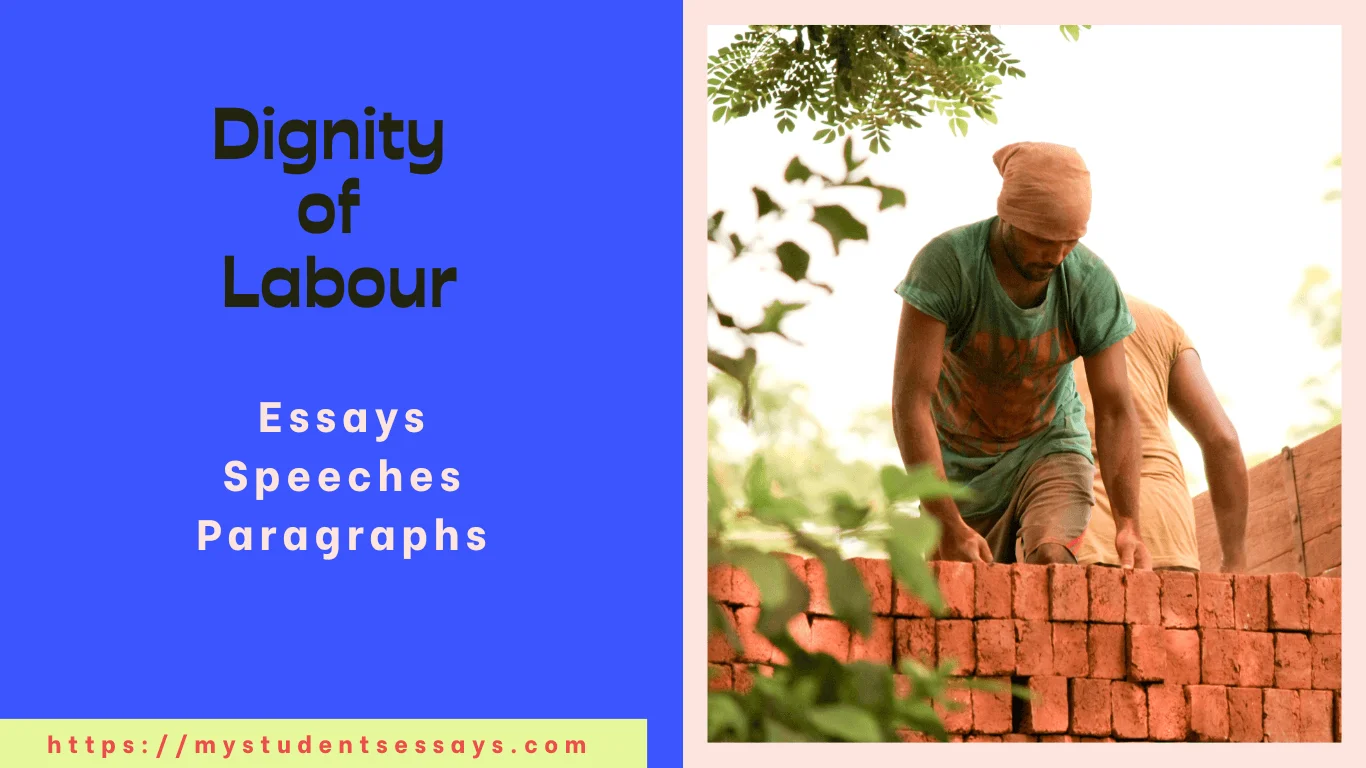

By labour, we generally mean work done by hands. Unfortunately, this word is used in a negative sense. There is nothing shameful in it. People having a narrow mind refer the word labour to professions adopted by carpenters, masons and their assistants. They also associate them with the lower middle class of society. As a matter of fact, these professions are benefactors of society. They play a vital role for peace and prosperity of our life. For example, mason builds a house to shelter us, a tailor sews clothes to cover our body and a farmer tills the soil to feed us.

We should not ignore that no office peon is employed in any office of the advance countries because in those countries every office worker feels no shame in doing the peon work himself. We are Pakistani and unfortunately, we feel it below our dignity.

If we read the history of nations like Japan, China, Germany etc., we shall learn that their economic development is based on attaching dignity to manual work. On the other hand, our Pakistani engineer will feel it below his dignity to join two wires and will say that it is the work of his subordinate mechanic.

In Islam all human beings are equal. Islam does not allow distinction on the basis of profession. The Holy Prophet (Peace Be Upon Him) used to work with his own hands. He carried bricks for the construction of the mosque and did not feel ashamed in mending his outworn shoes. In Islam, the honest work of all kinds is worth respecting. Even a sweeper deserves respect. In Islam work is worship.

Unfortunately, we ignore the bright example set by Holy Prophet (Peace be Upon Him) and consider manual work as undignified. We also look down upon the labour class.

People should change their thinking and should not hesitate in doing their jobs. This spirit will improve our economic condition. In the advanced countries, the major cause of the development is that dignity of labour has got its due importance.

In Pakistan, a large number of people are working in the houses of landlords. They only take the meal and clothes and server like slaves. Today every rich man always wishes to have a large number of servants in his home.

We have misused the concept of labour and this is the major cause of backwardness in our country. If we want to improve our economic condition, we should give equal status to the labour class in society.

You may also like:

- Essay on the Role of Bank with Outline for Students

- Essay on Cash Crops of Pakistan with Outline for Students

- Essay on Terrorism with Outlines and Quotes

- Essay on Overpopulation with Outline

- Essay on Illiteracy Problem with Quotations

- More In English Essays

Essay Writing 101: The Basics That Every Writer Should Know

Students and Social Service Essay with Quotations

Load Shedding in Pakistan Essay – 1200 Words

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Privacy Policty

- Terms of Service

- Advertise with Us

The dignity of Labor Essay |Outlines, Quotes, and good comprehension

1. introduction.

Every sort of labor is respectable

All types of labor contribute to the survival

2. Labor as a manual work

No alternative to working with hands

Labor as innovation in discoveries

3. History of manual work

Ancient people denigrated the value of manual labor

The modern era enlightened the grace of manual workers

4. Value of working with hands

Nations prosper by accepting the worth of manual workers

Variety of manual labor provides a variety of requirements

5. Respect of skilled workers

Holy Prophet (PBUH) teaches us to manual labor

Examples of hard works of Quaid-e-Azam

6. Labor as the satisfaction of the human soul

Not form of labor but intentions matter

Meaningful labor is personally enriched

7. Conclusion

“dignity of labor”.

The dignity of work can be defined as value and respect given to all forms of labor and work. It means the jobs related to manual labor should be given equal priorities and manual workers should be given equal rights to other workers. The first disobedience of Adam was eating the fruit of the forbidden tree which brought him the curse of the Lord. The curse was to the effect that man was ordered to earn his bread with his sweat and blood. Supposing some sort of labor as demeaning work is a hateful sense of human status. All types of labor equally contribute to the welfare and development of society. There passed a time when slaves were bought and sold openly in the market. In this way, their dignity was lost and they were forced to perform all sorts of hard works. Then time changed and now people are living in the independent and democratic era.

Labor as a manual work:

There is no alternative to working with hands. We cannot survive until we utilize our abilities. Although man is prior of all creatures in the world he cannot live without earning his bread. Nobody can bring him livelihood by waving a magic wand.

Generally, we mean working with hands is the definition of labor. Manual labor or working with hands is considered an inferior sort of work. In this world, nothing can be achieved without labor. Labor and industry contributed to the development of civilization. When we discuss basic human rights labor class is not enjoying the rights as white collared people and merchants. Even educated ones do not appreciate this class’s efforts. Only those people are preferred who own high profiled jobs. These so-called educated and civilized people do not even think that where the world would stand if no one worked.

“Labor is the superior of capital, and deserves much the higher consideration” Abraham Lincoln

Labor is important for making innovations and changes. If after the discovery of the wheel no one has worked for making engines then we will still have been traveling on animals. Or after the discovery of the power of steam, if no one had worked to make a steam engine then what is the use of discovery of steam power? If there were no one to plow the fields, there would have been no crops. As the result, we would have been facing a scarcity of food. If an engineer is important for making buildings drawings then mason is also of equal or even more important for giving a proper shape to this drawing.

History of manual work:

Prosperity and development of nations depend on works done by its masses. If masses live their lives like Lotus-eaters, not only development is possible but also they would not survive long. No pain, no gain is the secret of all the developed nations. Depreciating manual labor is said and shameful act of current society. There is a vast history of people who denigrated the worth of manual labor and tried to tarnish the dignity of labor with hand. But time changed and people are now more modern and enlightened with the power of respect and status befitting to all kinds of labor. The sad image of the story is that this respect and honor of manual labor is still being denied in most parts of the world. Hence this is not a worldwide concept and laborers are still looked down on by upper-class society.

“From the depth of need and despair, people can work together, can organize themselves to solve their own problems and fill their own needs with dignity and strength.” Cesar Chavez

The major cause of retardation in our country is that we do not appreciate our labor. That’s why people are forced to work in European and other developed states. They are still laborers in those countries but the main difference is that they are not treated with disregard by the people of those countries. However, they get good perks in those countries and decent benefits in return for their efforts. If we are willing to earn a good status in the view of other nations then we should give equal rights and benefits to the labor class as well. This is the only way of improving our economy.

Also, Labors should understand their worth and should not be ashamed of their manual work. Manual work bears equal importance as others do.

Value of working with hands:

The reality is that no community, society, or human can survive without manual labor. No nation can prosper without accepting the worth of farmers, industrial workers, masons, and minors who try to make day-to-day life possible. All of these manual labor are the key factors of making prosper and developed society. Every sort of labor is sacred whether it is manual, menial, or mental if it is done with honesty and truthfulness.

A human being is superior to all the creatures just because of their ability to work and power to think. Human is prior because of their capability of differentiating between good and bad. We are provided with all the things naturally like fruits, vegetables, air, and a lot of other blessings but not in a usable form. These blessings become functional with agriculture, industries, trading, and transformation. All these activities are interlinked and the common feature of all these kinds of transformation is labor. We require farmers, constructers, and industrial employees. Without these manual workers, we would not be able to survive like if farmers are not available there would be a scarcity of food. So we should be thankful to these entire professionals and laborers that become sources of providing us blessings of Almighty in proper form. In fact, all of this manual labor is the reason for our existence. This variety of manual labor provides a variety of our requirements. So this is just a distribution of labor that helps us to survive. Labor is labor, whether we are working while sitting in a cabin or on roads both, are interlinked with each other. This chain and cycle are important to be continued for our existence.

When it comes to human dignity, we cannot make compromises. Angela Merkel

Respect of skilled workers:

Our role model and biggest motivation for all mankind Hazrat Muhammad (PBUH) teach us to work hard and present a lot of examples by His deeds in which he worked with his hands. He (PBUH) is a messenger of Allah Almighty still he used to mend his shoe with his own hands. Hazrat Muhammad (PBUH) never hesitated to sew a patch of his shirt by himself. He (PBUH) used to milk his goats and get water from the well. In the battle of khandaq he participated in digging moat by himself that is why this battle is known as Ghazwa Khandaq.

The Holy Prophet (PBUH) said: “Your brothers are your servants whom ALLAH has made your subordinate, he should give them to eat for what he himself eats and wear for what he himself wears and do not put on the burden of any labor which may exhaust them”

Our industrious hero Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah once said:

“Work, work and work”

He used to work from day to night and for the independence of Muslims. His sister, Fatima Jinnah used to advise hos to take care of his health and reduce the amount of work. He used to smile over and reply:

“If the leaders of the nation will not work, who else will?”

Labor as the satisfaction of human soul:

Labor has several forms but all of them have been organized in manual and intellectual labor. Both of them bear equal rights and no one is inferior or superior to the other. Meaningful work and labor can be defined that is personally enriched and contributing positively. We all are responsible for our deeds and we are answerable to Lord in the end. So it is not the manual or mental work that is inferior or superior but it is the work done with which sort of intention.

“Your profession is not what brings home your weekly paycheck, your profession is what you’re put here on earth to do, with such passion and such intensity that it becomes spiritual in calling.” Vincent Van Gogh

If labor is working manually with his pure intentions then no doubt he is superior to all of the mental and intellectual labors as well. So, the aim and designation of doings is the major factor about which we should be careful.

Conclusion:

The dignity of labor means all occupations and professions whether based on intellectual or physical labor should enjoy equal rights and place in society. All the occupations are compounded to make societies prosper and develop. So it is concluded that there is no work and job inferior or superior. All sorts of labor are important for the survival of humankind. Every dutiful worker and every job being done with honesty and sincerity should be appreciated. Regardless of the concept of manual or mental labor, every job deserves honor and respect. We should understand that fellow beings are working to support society and their families as well. So we should not consider any job or labor as insignificant.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Essay on the Dignity of Labor with Outline for Students

- January 10, 2024

Kainat Shakeel

In our ever-evolving society, the conception of the dignity of labor holds profound significance. From historical perspectives to present-day challenges, admitting the value of every job is pivotal for fostering a harmonious and inclusive community.

The dignity of labor is a dateless conception that transcends artistic and societal boundaries. It goes beyond the type of work one engages in and encompasses the natural value every job holds in contributing to the well-being of society. In this essay, we will explore the historical elaboration of views on labor dignity, bandy the challenges faced by sloggers, and claw into the profitable impact of feting the value of every job.

Historical Perspectives

Throughout history, the perception of labor has experienced significant metamorphoses. In ancient societies, certain jobs were supposed more honorable than others, frequently grounded on societal scales. still, as societies evolved, there surfaced a consummation that every part, anyhow of its nature, played a vital part in the functioning of society.

The Value of Every Job

It’s essential to understand that the dignity of labor extends to all professions. Whether one is a croaker, a janitor, or an artist, each part contributes uniquely to the fabric of our community. This recognition fosters a sense of inclusivity and concinnity, breaking down societal walls and conceptions associated with particular occupations.

Challenges Faced by Laborers

Despite the universal significance of labor, workers frequently face colorful challenges. From societal prejudices to conceptions about certain professions, individuals may encounter walls that undermine their sense of dignity. It’s imperative to address these issues inclusively to produce a further indifferent work environment.

Economic Impact

Admitting the dignity of labor isn’t simply a moral imperative but also a sound profitable strategy. When every job is valued, it enhances overall productivity and contributes to the growth of frugality. Feting the link between labor dignity and profitable success is essential for erecting a sustainable and thriving society.

Particular Stories

Real-life stories of individuals prostrating societal impulses and chancing fulfillment in their work serve as important illustrations of the dignity of labor. These stories humanize the conception, making it relatable to compendiums from all walks of life. similar narratives inspire a shift in perspective, encouraging a more inclusive and regardful view of different professions.

Education and mindfulness

Education plays a pivotal part in shaping stations towards labor. By incorporating assignments on the dignity of labor into educational classes, we can inseminate a sense of respect for all professions from an early age. also, adding mindfulness about the significance of different places in society can contribute to a further enlightened and inclusive perspective.

Changing comprehensions

Enterprise and movements aimed at changing societal stations towards certain professions have gained instigation in recent times. Success stories of individualities breaking walls and grueling preconceived sundries demonstrate the power of collaborative efforts in reshaping comprehensions about the dignity of labor.

Global Perspectives

Stations towards labor dignity vary across different countries. By comparing and differing these perspectives, we gain precious perceptivity into the artistic nuances that shape societal views on work. international efforts to ameliorate working conditions and promote fair labor practices contribute to a global discussion on the significance of feting the dignity of every worker.

Government programs

The part of government programs in securing workers’ rights and promoting a fair and staid work environment can not be exaggerated. assaying the impact of legislation on labor conditions allows us to understand the positive changes brought about by nonsupervisory fabrics and identify areas for enhancement.

Technological Advances

Advancements in technology are reshaping the geography of work. While robotization and artificial intelligence bring about an unknown edge, they also pose challenges to the traditional conception of labor. Balancing technological progress with preserving labor dignity requires thoughtful consideration and ethical decision-making.

Future Trends

As we navigate the complications of the ultramodern work geography, it’s pivotal to anticipate unborn trends and their counteraccusations for labor dignity. From remote work to gig frugality, understanding the evolving nature of work is essential for ensuring that the dignity of labor remains a central tenet of our societal values.

The part of Unions

Labor unions have historically played a vital part in championing workers’ rights. Examining the influence of unions in different surroundings provides precious perceptivity into collaborative efforts to cover the dignity of labor. Their part in negotiating fair stipends, safe working conditions, and other essential benefits can not be exaggerated.

Empowering the Next Generation

Instilling a sense of dignity in labor from an early age is crucial to shaping the stations of the coming generation. Educational strategies that emphasize the value of different professions and promote a regardful view of all jobs contribute to erecting a society that values and respects every existent’s donation. In conclusion, the dignity of labor isn’t a conception confined to history but a living principle that shapes our present and unborn. Feting the value of every job, challenging conceptions, and championing fair labor practices are essential ways to create a society where every existent’s donation is conceded and admired.

Kainat Shakeel is a versatile Content Writer Head and Digital Marketer with a keen understanding of tech news, digital market trends, fashion, technology, laws, and regulations. As a storyteller in the digital realm, she weaves narratives that bridge the gap between technology and human experiences. With a passion for staying at the forefront of industry trends, her blog is a curated space where the worlds of fashion, tech, and legal landscapes converge.

The Endless

August 29, 2022

Dignity Of Labour Essay: Suitable For All Class Students

Essay on Dignity Of Labour

[Introduction. Labour and life. Labor and social status. Labour and achievement. Conclusion.]

“….if any would not work,neither should he eat.” (The Bible)

Dignity Of Labour Essay – Work or labor has no alternative. There is no shame in working. All must work according to their ability. Man can not, and should not, live without labour . Although man is the greatest creature of the universe, he has to earn his own bread; nobody brings him his livelihood by a wave of any magic wand. Whatever he needs, he must acquire through hard work. If anyone wants to have anything without undertaking the burden of labour , he has io indulge in illegal activities which deserves no dignity at all.

Labour gives us life and livelihood. That is why it is above all other things in life.

The main success of man’s life is to strike a unique balance between his needs desires or dreams and achievements. What man wants really exits in the world. But if he wants to have it, he has to labor hard. He has to earn all this: his bread for survival, knowledge, success, wealth, friendship, fame and all other things that he craves for. Likewise, social status, historical identity, esteem from others—these all need to be procured through hard labor. If there is to be anything called luck, then it must be a series of blanks that must be filled up by hard labor. Or, more specifically

“Luck is what happens when preparation meets opportunity.”

So, preparation must be there. Nothing can actually come to man from the empty luck.

Likewise, we have to define fate in a practical way. It can be said that fate is the external environment of man which he directly or indirectly reacts to but can not control. It is, in other words, a set of restrictions. We can not, as has already been said, control fate, but we can easily control ourselves. And it can be possible by dint of labour. Hence the saying goes:

“When fate shuts the door, come in through the window.”

Therefore, labor makes everything possible. Without it, nothing can be done or achieved. Even any religious practice without any labor has no value. Pure religion is what we do after our prayer is over. Prayer is indeed a preparation. For this reason, labor is given the most importan in all religious books of the world.

Don’t Forget to Check: Essay in English

The idle brain is the root of all evils, they say. This may do big harms to the society as well as the nation. Thoughts which are aloof from work or labour do not advance much; they reduce into daydreams and fancies. An author aptly says, ” There is no such way by which man can escape from labour, and the act of thinking is more laborious.”

No labor is detestable. The thinking of the scholar, the leading of the leader, the advice of the specialist all these are as essential as to us as the labor of the cooley, the day laborer, the sweeper, the farmer, the hawker, the shopkeeper, the clerk, and all others. If we abhor the work of the sweeper and he postpones his work only for two days, then this gentlemanly town life of ours will become a hell. Likewise, if the cobbler ceases to work, and yet we want to keep our status intact, then we ourselves will have to become cobblers, at least for our own purposes. Therefore, all types of work are dignified and valuable. We all are labourers .

But it is a matter of great regret that in this sub-contiment, even in this modern age, people are socially classified according to what they do, and consequently, are considered as of varying status. We consider that labourer as mean but for whose labour we could not have been in the so-called higher position. It is very sad. No nation believing in such incongruous classification of mankind has ever prospered enough. In the developed countries, a labourer is most esteemed. All kinds of labour are encouraged there. We too should take lessons from their examples.

Only labour has made it possible to create the great things of the world. The Taj, the Great Wall of China, Mona Lisa-all these are fruits of unfatigued labour. Nothing has been, can be, and will be possible without labour.

In conclusion, a famous man can be quoted: “Man’s greatest friends are the ten fingers of his hands.” He is quite right. But it should not be forgotten that physical labor and mental labor are complementary to each other.

Dignity of labor essay 2

Topic: (Introduction, Classification, Importance, Manual labor does not make man low, Conclusion)

The work of a clerk, a teacher, a professor, a lawyer, a doctor does not require much physical labor. On the contrary, the work of a cultivator, a miner, an artisan requires physical labor. When we say that the work of the cultivators, miners, artisans etc. is as respected as the work of the clerk, the teacher, the lawyer, and the doctor, we mean there is the dignity of labor.

There are two kinds of labor-manual and intellectual. Each of them has the dignity of its own and none is inferior to the other.

There is a great importance of manual labor in human life. We grow crops, build houses and factories, construct roads and streets etc. by manual labor. Manual labor is also necessary for the fields, mines, mills, and ships. If the sweepers, the porters, the carpenters, mason, the blacksmith, and the peasants did not perform their duties, the whole of mankind could not have enjoyed the present result of civilization. It gives us good physical exercise and so keeps our body fit and strong. It helps the continuation of our existence in this world. We cannot live without food, drink, clothes, and houses. But these are gifts of manual labor. So manual labor is more essential than the intellectual.

In our country, people usually do not respect manual labor. They think that manual labor lowers down their position in society. So they hate manual labor. A man with a little bit of education does not even wash his own clothes because of his vanity.

But this picture is quite different in the developed countries of the world. For instance, Tolstoy came of a very rich family. He himself did manual work like another peasant. Great men of the world believe that manual labor can never lower down the prestige of a man.

At present, the outlook of our countrymen has not yet completely changed. But we should understand that manual labor makes a man great and dignified. An ordinary laborer without education is better than an educated idle man. So, we should feel that there is the dignity of labor in every sphere of life.

Dignity Of Labor Essay 3

Introduction : Everything has its own dignity whatever it may be. It is dignified in accordance with its utilization and utility. It is the most valuable powerful element of success in life .

Kinds of labor: Labour is of two types-manual and intellectual. Each of them should have a dignity of its own. But unfortunately, most of our educated persons have a wrong idea of manual labour . Consequently, they look down upon the people engaged in manual work. In such a context we should keep in mind that manual labour has noting debasing about it.’

Manual labor : Manual labor is at the root of our livelihood. The food, drink, clothes, and houses without which we cannot live are all the gifts of manual labor. It is manual labor that drives the plow and reaps the harvest. It grinds the corn and turns it into bread. It spins the thread and weaves our clothes. It lays brick upon brick and builds our houses. Manual-workers are thus the backbone of a nation. In western countries, all house-hold works are done by the people themselves. They have to clean their own floors and wash their own bathrooms. There is no porter to carry their pieces of luggage. A passenger has to carry his own bag. A carpenter, a mason or an electrician has his own dignity.

Intellectual labor: Labour of this type is dignified to many. Working in the office, bank, insurance company etc is regarded as intellectual labor. It has a touch with manual labor. The country’s development in the international field depends on it. Science, literature, culture, technology etc are intellectual labor. But unfortunately, many people in our country still think that manual labor is not dignified. It is ridiculous to think that a clerical job is more dignified than manual work in agriculture, horticulture, carpentry, pottery, tailoring, book-binding, spinning, weaving, dairy, poultry etc. This false notion should be changed. It is especially important in the context of the economic realities of the country. Indeed this dignity of labor may be a powerful means of combating the problem of unemployment which is becoming large in our country.

Importance: Dignity of labor has an important role in the country. No nation can develop unless her people undergo any labor. If we consider the developed countries, we find that the people of those countries did not hesitate but labored hard. Labour of any kind is dignified as it can give everything to society. The nation’s development depends largely on labor. All the great men in the world labored hard and achieved dignity.

Difficult to provide employment: We cannot expect that every educated young man would be given a secured and comfortable job with a chair and a table and a fan in an office or in a bank. We must admit that no government can provide employment to all the unemployed youths.

Labour gives dignity: Hence self-reliance and dignity of labor may be the only reasonable way to solve the problem of unemployment. We should remember that God has given us not only the head but hands also. We should fully utilize these gifts to enrich our lives. Moreover, those who are engaged in intellectual jobs should do some manual works for keeping a balance between the two for a normal and healthy life.

Teaching dignity of labor: Thus we should have an ideal position of manual labor in our society. And for this, the dignity of labor should be taught from childhood. If every child is asked to do his or her own work as much as possible, it will be good for the future struggle of life. We should all bear in mind that work is worship and in this way, the dignity of labor should be recognized in its due importance.

Conclusion : Labour of any kind pays much more than anything else. It helps contribute to the economic development of an individual and a nation.

About the Author

This is my personal Blog. I love to play with Web. Blogging, Web design, Learning, traveling and helping others are my passion.This blog is the place where I write anything whatever comes to my mind. You can call it My Personal Diary. This blog is the partner of My Endless Journey

July 13, 2020 at 10:33 pm

Thank u soo much It really helpful for me

October 5, 2020 at 9:02 am

Help ful for me.😎

Comment Policy: Your words are your own, so be nice and helpful if you can. Please, only use your real name and limit the number of links submitted in your comment. We accept clean XHTML in comments, but don't overdo it, please.Let's have a personal and meaningful discussion.

Please Say Something or Ask Any question about this topic! Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Academic Test Guide

Essay on Dignity of Labour in English For Students and Children

We are Sharing Essay on Dignity of Labour in English for students and children. In this article, we have tried our best to give an essay about Dignity of Labour for Classes 5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12 and Graduation in 200, 300, 400, 500, 800 1000 words, a Short essay on Dignity of Labour.

Short Essay on Dignity of Labour in English

Labour implies a piece of work as well as manual labour, i.e., those who work with their hands. hi ancient times, manual labour was looked down upon in society. The labourers were treated as slaves. This gave rise to a feeling of contempt for manual work Slavery has been banned and abolished of late. In modem times, people have begun to realise the dignity of labour. But there are few people of the higher class who still have a different view. Mahatma Gandhi himself wove the khadi garments he sore. He is a perfect example of the dignity of labour. Manual work is in no way inferior to mental work. When mind and hands combine, the results are praiseworthy. Honest work of all types is worthy of respect. Work is worship.

Essay on Dignity of Labour in English ( 500 words )

Labour implies ‘a task’ or ‘a piece of work’. It also implies ‘workers’, especially those who work with their hands. It refers to manual labour. Dignity means ‘honourable rank or position’. ‘Dignity of labour’ thus implies the honourable position of workers who work with their hands. Manual labour is distinguished from mental labour. When we do mental work, our minds work, but our hands remain still. In manual labour, we exercise our hands, whereas, in mental labour, we exercise our brain, i.e., the mind.

In ancient times, manual labourers were considered slaves. They were looked down upon in society. They were treated as inferiors. This gave rise to a feeling of contempt for manual work. The mason, the carpenter, the farmer were all differentiated from the other class of people. Slaves were victims of mockery and hatred. Slavery existed in almost all countries. It was more prevalent in America where the whites bought the blacks to employ them in the plantations. Later on, slavery was banned and abolished.

In modern times, people have become more civilised. They began to realise the dignity of labour. Manual labour is no longer looked down upon in society. There are few people belonging to the upper class who still have a different view. They think it below their dignity to do their work themselves. They employ servants to do the household activities and to look after their children.

Today, the worth of labour is recognised by all. There is no longer the feeling of contempt for manual work. Manual labourers today are treated as equals in society. India is a democratic country and all are considered equal in the eyes of law.

Mahatma Gandhi preached dignity of labour in the Sabarmati Ashram. He taught the dwellers to clean night soil’ with their own hands. During the struggle for Independence, Gandhiji advised the people to weave the clothes that they would wear. Gandhiji himself wove the khadi garments he wore. This is a perfect example of ‘the dignity of labour’.

Honest work is worthy of praise and credit. Today, manual work is in no way inferior to mental work. When mind and hands combine, the results are praiseworthy’. Monuments, forts or other historical buildings are the results of such a combination. The immortal works of sculptors and painters are also the results of such a combination.

Honest work of all types is dignified. They are worthy of respect. There is no discrimination between a sweeper and a mason, a carpenter and a doctor, a farmer and an engineer or a driver and a teacher. If all become doctors, engineers and teachers, there will be none to do the other types of work. Every honest work is important in society.

Children who always have servants to look after them or cater’ to their needs as they grow up, fail to understand the dignity of labour. They do not prove to be good and responsible citizens. They get spoiled from their very childhood. Parents should bring up their children, giving importance to the values of life.

One should not remain idle. One should not be ashamed to do labour. Work is worship. We work and get something in return. Work is an essential need for survival. We must, thus, value the dignity of labour.

# Essay on The Dignity of Labour for Students # Speech on Dignity of Labour # Short note on Dignity of Labour

Dear viewers, Hope you like this article Essay on Dignity of Labour in English and Please let us know by commenting below.

In search of someone for hire to write a paper on dignity of labor topics? You are not alone, feel free to buy essay online written by an expert writer.

Essay on Mahatma Gandhi

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Human Development Report 2023-24

- The paths to equal

- 2023 Global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI)

- 2023 Gender Social Norms Index Publication

- Human Development Index

- Country Insights

- Human Climate Horizons data and insights platform

- Thematic Composite Indices

- Documentation and downloads

- What is Human development?

- NHDR/RHDR Report preparation toolkit

Valuing the dignity of work

Dr. Juan Somavia

In today’s world defending the dignity of work is a constant uphill struggle. Prevailing economic thinking sees work as a cost of production, which in a global economy has to be as low as possible in order to be competitive. It sees workers as consumers who because of their relative low wages need to be given easy access to credit to stimulate consumption and wind up with incredible debts. Nowhere in sight is the societal significance of work as a foundation of personal dignity, as a source of stability and development of families or as a contribution to communities at peace. This is the meaning of ‘decent work’. It is an effort at reminding ourselves that we are talking about policies that deal with the life of human beings not just bottom line issues. It is the reason why the International Labour Organization constitution tells us “Labour is not a commodity. i ” And we know that the quality of work defines in so many ways the quality of a society. And that’s what our policies should be about: keeping people moving into progressively better jobs with living wages, respect for worker rights, nondiscrimination and gender equality, facilitating workers organization and collective bargaining, universal social protection, adequate pensions and access to health care.

All societies face decent work challenges, particularly in the midst of the global crisis that still haunts us. Why is this so difficult? There are many converging historical and policy explanations, but there is a solid underlying fact: in the values of today’s world, capital is more important than labour. The signs have been all over the place—from the unacceptable growth of inequality to the shrinking share of wages in GDP. We must all reflect on the implications for social peace and political stability, including those benefitting from their present advantage.

But things are changing. Many emerging and developing countries have shown great policy autonomy in defining their crisis responses, guided by a keen eye on employment and social protection, as the 2014 Human Development Report advocates. Policies leading to the crisis overvalued the capacity of markets to self-regulate; undervalued the role of the State, public policy and regulations and devalued respect for the environment, the dignity of work and the social services and welfare functions in society. They led into a pattern of unsustainable, inefficient and unfair growth. We have slowly begun to close this policy cycle, but we don’t have a ready-made alternative prepared to take its place.

This is an extraordinary political opportunity and intellectual challenge for the United Nations System. Coming together around a creative post-2015 global vision with clear Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) can be a first step into a new policy cycle looking at what a post-crisis world should look like. And beyond the United Nations, we need to listen. There is great disquiet and insecurity in too many societies. . And that’s why the insistence of the 2014 Human Development Report on reclaiming the role of full employment, universal social protection and the road to decent work is so important. It builds on the existing consensus of the largest meeting of Heads of State and Government in the history of the United Nations. In their 2005 Summit they stated that “We strongly support fair globalization and resolve to make the goals of full and productive employment and decent work for all, including for women and young people, a central objective of our relevant national and international policies as well as our national development strategies. ii ” So, at least on paper, the commitment is there in no uncertain terms.

Let me finish with one example of the changes necessary for which I believe there is widespread consensus. Strong real economy investments, large and small, with their important job-creating capacity must displace financial operations from the driver’s seat of the global economy. The expansion of short-term profits in financial markets, with little employment to show for it, has channeled away resources from the longer term horizon of sustainable real economy enterprises. The world is awash in liquidity that needs to become productive investments through a regulatory framework ensuring that financial institutions fulfil their original role of channeling savings into the real economy. Also, expanding wage participation in GDP within reasonable inflation rates will increase real demand and serve as a source of sustainable development growth. Moving from committed minimum wage policies to a much fairer distribution of productivity gains and profits should be a point of departure. Dreams or potential reality? We shall see, but no doubt this is what politics and social struggles will be all about in the years to come.

This blog entry is slightly shortened version of a special contribution made to the 2014 Human Development Report “Sustaining Human Progress: Reducing Vulnerabilities and Building Resilience” .

Dr. Juan Somavia is the former Director General of the International Labour Oganization.

Notes: i Constitution of the International Labour Organisation and Selected Texts. Geneva: International Labour Office. www.ilo.org/public/english/bureau/leg/download/constitution.pdf . Accessed 25 March 2014. ii UN World Summit Outcome (A/60/L.I) 15 September, 2005. New York. www.un.org/womenwatch/ods/A-RES-60-1-E.pdf . Accessed 25 March 2014.

Photo credit: ILO/Jacek Cislo

The HDialogue blog is a platform for debate and discussion. Posts reflect the views of respective authors in their individual capacities and not the views of UNDP/HDRO.

Related News

Sustainable Human Development Pathways - a consultation with Southern-based think tanks

How COVID-19 is changing the world: a statistical perspective

Essay on “Dignity of Labour” for School, College Students, Long and Short English Essay, Speech for Class 10, Class 12, College and Competitive Exams.

Dignity of Labour

Essay No. 01

The dignity of labour means respect and value given to all forms of work. It refers to equal respect for the jobs that involve manual labour. In earlier times, daily several slaves were bought and sold openly in the markets. They lost their dignity and performed all sorts of hard and laborious works. Today, we are living in an independent and democratic age. It has been realized by most of the people that all forms of labour contribute to the welfare and development of society. The labourers through trade unions and different groups have gained success in attaining a recognized position in society.

When we talk about basic rights, the working class do not enjoy that respect which is enjoyed by business executives, white-collared people and merchants. Many learned people do not appreciate and practice. the principle of dignity of labour. They prefer high-profile jobs. For example, a science graduate, who is the son of a wealthy farmer, would like to take up any job in a nearby city rather than to follow his father’s occupation. Thus, it is not wise to look down upon manual labour.

Manual labour is extremely important and necessary for the smooth functioning in society. Although today most of the work in industries and factories is done by machines, production can be paused without the manual assistance of the workers. Lakhs of labourers work imines, agricultural sectors, construction fields and industries. Although they work with the help of machines, it is their duty to operate and maintain the machines. Invention and introduction of machinery have given rise to a new class of industrial workers. If the workers slow or stop the manufacturing of the essential goods even for a few days than the entire nation can suffer a severe setback. Thus, it is our main duty to show them respect and offer dignity.

In many western countries, the dignity of labour is recognized. Young people do not mind in earning money by doing pan-time work as food delivery boy or waiters at the restaurant. Much of the domestic work like cooking food and washing clothes is done by the members of the family. However, in countries like India, domestic servants are scarce and their demands for wages are very high. Many middle-class families pay more to servants to maintain their prestige in society.

A sense of dignity of labour should be conveyed to students in schools and colleges. They should be encouraged to participate in various kinds of programmes. If their minds are cleared of the view that none of the works is undignified and humiliating, the problem of unemployment will be solved to some extent.

Essay No. 02

A domestic help- she cleans, she washes, she even runs house errands but at the end of the day, she is yelled at for leaving a small little mark on the otherwise clean floor. Lenin founded Communism. Mark came up with the idea of socialism. But in a democracy like India, people have the right to do what they want, right? They can treat people of so-called lower stature in any which way.

An honest day’s work does not earn a person’s respect. And not much money either. So in the modern-day and age money earns respect, not the job you do. A mechanic, a domestic help, a driver cannot walk with their heads held high. Even though they work an equal amount of time (sometimes even more), they are looked down upon.

Who decides which work is better? Who decides which form of work deserves respect? Shouldn’t an honest and descent job be enough? But it’s not the case. The dignity of labor is a thing of the past, seems as though it never even existed. The definition of the dignity of labor is no work should be looked on upon. No one should be treated with any less respect just because of the work they do.

In a democratic system, the rights of the people are protected. Everyone is equal in the eyes of law, the government, and the country. But no one is equal in each other’s eyes. Of late the present environment of the society, the dignity of labor is considered one of the major topics dealing with laborers. The ongoing debate on this topic has reached its peak with people coming to know about their rights. Society has come to terms with the act that every job performed by a laborer is a tough one. Also, it has been understood that he is specialized in these jobs and these jobs are an integral part of the functioning of society. These jobs might be considered menial but think about it. Will you get up and wash the utensils every day? Will you wash your car?

The answer to all of the above is that we have to respect every form of work and thus the solution to all of this is Dignity of Labor. Respect people who work, as this will help not only increase employment but also provide the basis for a healthy society.

Essay No. 03

Nature provides us with everything we need, but not in usable forms. With our various activities like agriculture, trade, industry, and learning, we transform the gifts given to us by the Almighty into products useful to us. As a common feature of all these activities, labour in one form or another is an important factor that makes such transformation possible. It is, in fact, the key factor to our very existence. The variety labour matches a variety of our needs. Therefore, each form of labour is important to us in its own way while few people among us work the iron is in nature to make steel, which builds our industries, some others generate power from water, coal or oil, to run them. If another group tills the land to raise crops, yet another transforms them into vital food. It is such distribution of labour among ourselves that helps us survive. We cannot imagine what our lives would be like. If we were unwilling to work or unprepared to engage in different occupations.

Life is a struggle; one must fight the battle of life valiantly. Everybody who takes birth has to die one day. Therefore, one should make the best of life. Time at our disposal is very short. We must make the best use of every minute given to us by God. Life consists of action, not contemplation. Those who do not act, but go on hesitating and postponing things, achieve nothing in life. Such persons as going on thinking and brooding can never attain the height of glory.

A short life full of action is much better than a long life of inactivity and indolence. Tennyson has rightly remarked that one crowded hour of glorious life is worth an age without a name. A man lives in deeds, not in years. Age or longevity does not matter. What matters is what one makes of life. Ben Jonson, the scholar-poet writes :

“It is not growing big in bulk like a tree Doth make man better be.”

Life is not an idle dream. Every beat of our heart is taking us nearer to our death. We must not lose any time in crying over the past or worrying about the present. H.W. Longfellow writes in his ‘Psalm of life’ :

“Trust no future, however pleasant; Let the dead past bury its dead Act, act in the living present Heart within, and God overhead.”

Though originally all occupations that were necessary and useful to humanity were encouraged and respected. However, as time passed some prejudices developed against certain occupations especially against those occupations that were relatively unimportant or unpleasant, and those that involved more physical effort than the others, were discriminated against. This tendency, along with the practice of deciding the social status of people, on the basis of their occupations, created unrest in society. Thus before long, the concept of distribution of labour, so essential for the health of society, ended up as its main bane. The unfortunate consequences of the distribution of labour and the deep-rooted prejudices against certain occupations were the main causes of casteism and untouchability, which have been plugging the Indian society for centuries. Through the efforts of many philanthropists and social reformers, who upheld the dignity of labour and restored respect for occupations, much of the prejudices have been eliminated.

However, much more needs to be done before we can realize the ideals of egalitarianism and social amity. Modern education, which helped change the outlook of people, was another factor that revived the dignity of labour. The life of Mahatma Gandhi is a typical example of the contribution of modern education in revolutionizing living. Though Gandhiji was born in a traditional, orthodox Hindu family and had a career as a successful lawyer the exposure he had to the outside world, earned him respect for all types of occupations. Gandhiji’s example is all the more important, because, unlike most others, he practiced the virtues of labour that he preached. It was his practice of cleaning his toilet, which was normally the job or scavengers, that ensured a sense of dignity for that job. He willingly did menial jobs on the farm, and while in jail, learned to cobble shoes. He virtually glamorized the occupation of spinning to the extent, that people of all classes and castes adopted the practice in their lives. Gandhiji’s identical respect for all occupations and his willingness to do or learn all manners of work, helped him establish self-sustaining communities, in India and South Africa. To this day the members of these communities honour the dignity of the labour and do all their work themselves, with no dependence of any kind on others. Thus, respect for labour and ensuring its dignity, give us a sense of independence. If nourished in all the members of community property and that too at the proper stage of life, the dignity of labour will help foster healthy relationships among them, thereby contributing to the strength of the community.

Related Posts

Absolute-Study

Hindi Essay, English Essay, Punjabi Essay, Biography, General Knowledge, Ielts Essay, Social Issues Essay, Letter Writing in Hindi, English and Punjabi, Moral Stories in Hindi, English and Punjabi.

Ot was a nice essay.It helped me in my summer vacations work.Thanks.

It help me to learn about Dignity of Labour. And also to participate in elocution competition?? I \ ‘

It was a very very very very nice essay . I really like it so much .I can participate in elocution competition .

it is nice essay it works in my english 1project

me too. it helped in my english assignment,,

Thanks it is really helpful

it was really helpful and it got me 1st prize in elocution competition

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

A philosopher’s view: the benefits and dignity of work

Professor of Philosophy, Macquarie University

Disclosure statement

Nicholas Smith receives funding from the ARC.

Macquarie University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

In a recent speech presented at the Sydney Institute, Julia Gillard reaffirmed her commitment to welfare reform aimed at full employment. This was justified not by the need for the government to cut its costs — there was no mention this time of a tough imminent budget–but by an _ethical _principle: work is a social good that governments ought to promote and help make available to everyone, if the circumstances allow it.

Furthermore, pursuit of the goal of full employment, on account of the “benefits and dignity” of working, is not just one political aim amongst others, but the central purpose of the Labor Party, as the prime minister depicted it in her speech. Under her leadership, “a new culture of work” would be entrenched.

Gillard’s speech raises some deep philosophical issues. Is work really a social good? If it is such a good, is it a special one, one that should be prioritized over others?

Is it the legitimate business of democratic governments to promote one conception of the good life over others (in this case, one that involves working) or to favour one particular culture or “ethos”?

Wouldn’t it be fairer to let people choose their own idea of what is good for them?

To get the question of whether work is really a social good into focus, it helps to specify, in suitably abstract terms, the kind of activity that work is.

The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle did this by way of a distinction between praxis , which is action done for its own sake, and poiesis , or activity aimed at the production of something useful.

The excellence or worth of _poiesis _consists entirely in the excellence or worth of the thing made by the activity.

This contrasts with _praxis _which, when it goes well, is its own end, worthwhile for its own sake.

Aristotle’s distinction between _poiesis _and _praxis _has had a huge influence on Western thinking about work.

It shaped Christian (especially but not exclusively Catholic) thinking about the value of work and was taken up in various ways by key philosophers of the Enlightenment, such as Adam Smith, and currents of Marxist and neo-classical economic thought in the twentieth century.

The conception of work as _poiesis _rather than _praxis _continues to be dominant to this day.

Work is widely seen as activity which is done exclusively for the sake of something else, as worth doing solely as a means to some external end.

Of course, gainful employment in a market economy always _is _done for the sake of something else: it is how most people make a living for themselves and their families. Work, as gainful employment, is an instrumental good.

It is instrumentally valuable from the individual worker’s point of view because of the income it brings.

And from a broader social-economic point of view, it is instrumental in the creation of the common wealth.

Now if this were the whole story about the value of work, then those who get an income without working, say by gaining an inheritance, or winning the lottery, or even claiming benefits, would not really be missing out on anything.

Indeed, they would be in the enviable position of receiving the benefits of work (income) without having to pay the costs (the effort, the time).

But it is clear that the lives of people who do not work are typically lacking in certain goods.

Research shows that physical and mental health are adversely affected by lack of work. You are more likely to suffer from obesity and depression, for example, if you are unemployed. This may be linked to another good that work helps to provide: self-esteem.

Self-esteem, in the sense of having a perception of the worth of one’s own existence, is bound up with the recognition one receives from others of one’s competences, achievements and contributions.

Your family and friends may love you just for who you are, and you may feel entitled to certain basic rights, like a right to basic welfare, just on account of being a person.

But the status of being a somebody , as the German philosopher Hegel famously put it, depends in modern societies on the public recognition of skills and achievements, which participation in a suitably regulated labour market is able to secure.

This brings us to another good that work can help to realise: the sense of being connected to something larger than oneself.

By participating in the division of labour, the French sociologist Durkheim observed, individuals can come to a livelier appreciation of their dependence on others and the need for cooperation.

And day-to-day practice in the activity of cooperative problem-solving, the American philosopher John Dewey persuasively argued, provides vital training for the citizens of a healthy democracy.

Health, the exercise and development of skills and capacities, self-esteem based on the recognition of one’s achievements, a sense of social connectedness and exposure to the demands of cooperation are some of the intrinsic goods associated with working life that are imperilled by lack of work.

Such goods are not subjective preferences, or expressions of cultural bias, but rationally justifiable ethical objectives that a government can legitimately seek to pursue.

But of course these goods are endangered not just by unemployment, but by the way in which work is actually organised .

Many jobs are in fact bad for your health, they stunt your capacities, they damage your self-esteem, leave you feeling isolated, and seem systematically designed to prevent you from cooperating with anyone.

So if the “new culture of work” called for by the prime minister is to have ethical weight, it needs to involve much more than the provision of more jobs: the _quality _of work has to improve.

For the benefits and dignity of work are as much a matter of what one _does _while working, and of the social relations one enjoys or endures there, as they are of the economic power it brings.

- Australian politics

Events and Communications Coordinator

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Winter 2024

The Dignity of Labor

Despite the outpouring of praise for essential workers during the COVID-19 pandemic, their own interests continue to come second to the broader public’s need for cheap and reliable labor.

This essay is part of a special section on the pandemic in the Summer 2020 issue .

Even before the coronavirus hit, the Bureau of Labor Statistics predicted that the highest demand for labor in the next decade would be seen in occupations where average pay is less than $35,000 a year. Among these jobs were personal care and home health aides, medical assistants, warehouse workers, janitors, and others now on the front lines of the pandemic.

These essential workers have long faced harsh conditions on the job, regardless of the economic and political context. This was the case even in the 1960s when a tight labor market increased wages for unskilled workers and when organized labor was at its strongest. “So often we overlook the work and the significance of those who are not in professional jobs, of those who are not in the so-called big jobs,” Martin Luther King Jr. stated to sanitation workers on strike in Memphis, Tennessee, in 1968. “But let me say to you tonight, that whenever you are engaged in work that serves humanity and is for the building of humanity, it has dignity, and it has worth.”

The problems facing the sanitation workers in Memphis stemmed from their exclusion from federal labor laws that had protected the rights of mostly white, male industrial workers to form unions and bargain collectively for better wages and working conditions since the 1930s. This exclusion was rooted in policies aimed at ensuring the availability and affordability of essential goods and services, which stretched back to the Progressive Era. Reformers insisted that rapid urbanization and industrialization required city and state governments to provide services that had previously been performed within private households, such as child care, healthcare, food preparation, cleaning, and waste disposal. They coined the terms “Public Housekeeping” and “Municipal Housekeeping” to explain the transition.

The comparison between domestic and public service helped to legitimize women’s participation in public life and leadership in city government, but it also encouraged officials to adopt racist and sexist assumptions that had informed structures of domestic servitude for centuries. In 1930 the trade journal The American City published an article by a Philadelphia sanitation engineer, which boasted of various methods used to reduce costs and raise funds. It was illustrated with a photograph of African-American women sorting rubbish for material that could be sold or burned for heat. “Colored women are used for this work,” the engineer informed readers, adding: “many typical mammies are found there.”

That a prominent professional journal would employ such derogatory language to describe city employees demonstrates how uncritically assumptions about the value of domestic labor were adapted to essential public services. And through the 1930s, conservatives fretted that increasing public employment would deprive them of low-wage household labor. “Five Negroes on my place in South Carolina refused work this Spring, after I had taken care of them and given them house rent free and work for three years during bad times saying they had easy jobs with the government,” wrote a prominent critic of New Deal employment programs in 1934.

This didn’t mean that these public jobs provided a decent living. Liberals constrained government expenditure by limiting wages and benefits. To ensure public access to inexpensive care, cleaning, and food, for example, Congress excluded farm workers, domestic servants, and public employees from policies designed to assist workers during the Great Depression. Franklin D. Roosevelt adopted the language of servitude to explain why these workers were denied collective bargaining rights under the National Labor Relations Act. Acknowledging that their interests were “basically no different from that of employees in private industry,” the president insisted that those concerns were overshadowed by “the special relationships and obligations of public servants to the public itself and to the Government.” As government expanded to provide healthcare, education, and other essential services in the mid-twentieth century, “The division of labor in public settings mirror[ed] the division of labor in the household,” observed sociologist Evelyn Nakano Glenn.

Essential workers did not accept these arguments. They launched vigorous movements to demand better treatment and compensation. Public employees were the most successful and by the 1950s they emerged as the fastest growing sector of organized labor. While conservatives blocked efforts to extend federal labor protections, states granted limited collective bargaining rights and minimum wage floors to public employees and farm workers in the 1960s and 1970s.

This was the context in which King went to Memphis. Tennessee was among the mostly Southern states that resisted the trend toward legalizing public unions, and the city hired sanitation workers as day laborers without any benefits or job stability. King’s assassination in Memphis steeled the resolve of those striking workers he was there to support, and they went on to win union recognition and wage increases. “What Memphis and the spirit of Memphis did was gave a new kind of recognition to some workers that had been there all along but never recognized,” recalled union leader William Lucy, an organizer of the strike.

But the spirit of Memphis met stiff resistance nationwide, both from conservatives who opposed the expansion of government and from liberals who insisted that government could be expanded without increasing taxes. The recession of the 1970s killed any hope for a federal extension of collective bargaining rights to public employees, and in 1981 Ronald Reagan famously fired 11,345 striking air-traffic controllers after they disobeyed an order to return to work.

While public-sector pay and benefits lagged behind other sectors, a steady beat of misinformation fed broad resentment of reputedly overprivileged government workers. In the early twenty-first century, that same warped envy burst back onto the scene, first directed toward home healthcare workers, who were paid with public funds but hired by private households. A 2007 Supreme Court ruling classified these aides as domestic workers, a move that, according to Nakano Glenn, “decreed that the burden of providing ‘affordable care’ for vulnerable members of society would continue to be borne not by state or federal governments or corporations but by the poorest and most disadvantaged members of the work force.” Similar logic fed the backlash against public-sector unions in New Jersey, Wisconsin, and other states during the Great Recession and the further weakening of federal protections for public employees and domestic workers.

Despite the outpouring of praise for essential workers during the COVID-19 pandemic, their own interests continue to come second to the broader public’s need for cheap and reliable labor. This was evident in Republican Senator Lindsey Graham’s opposition to increased unemployment benefits for nurses, on the grounds that this was “literally incentivizing taking people out of the workforce at a time when we need critical infrastructure supplied with workers.” But it may also be limiting Democrats’ support for proposals such as the Public Service Freedom to Negotiate Act (which was referred to the House Committee on Education last June and remains there) and Senator Elizabeth Warren and Representative Ro Khanna’s recent Essential Workers Bill of Rights.

Politicians’ resistance or reluctance to support worker power indicates that we are not yet prepared, as King hoped over fifty years ago, to respect “the dignity of labor.” But as he and those who went on strike from collecting garbage knew, together workers can force that recognition by depriving us of the essential services they provide.

William P. Jones is professor of history at the University of Minnesota, the Jerry Wurf Memorial Fund Scholar-in-Residence at the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, President of the Labor and Working-Class History Association and author of The March on Washington: Jobs, Freedom, and the Forgotten History of Civil Rights . He is writing a book about race and labor in the public sector.

Sign up for the Dissent newsletter:

Socialist thought provides us with an imaginative and moral horizon.

For insights and analysis from the longest-running democratic socialist magazine in the United States, sign up for our newsletter:

LearningKiDunya

- Arts Subject

- Science Subjects

- Pair of Words

- Arts Subjects

- Applications

- English Book II Q/A

- Aiou Autumn 2020 Paper

- Guess Paper

- PAST PAPERS

- Exercise Tips

- Weight loss Products

- 2000 Calories Formula

- Books On Weight loss

- RELATIONSHIP

- MARRIGE COUNCLING

- FAMILY COUNCLING

- Private Jobs

- Cookies Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy Policy

Header$type=social_icons

Dignity of work essay | dignity of labour essay with quotations | dignity of labour essay with outline.

essay on dignity of work, dignity of work essay with outline, importance of dignity of labour in points, dignity of labour pdf, dignity of work essay

Self-respect and dignity both in thoughts and actions have been the main traits of great personalities history preserves the names and deeds of such men in golden words as led their lives in a dignified manner. They did not give in before False ego, inferiority or superiority complex, and self-pity. they fixed some goals for themselves and then with unflinching determination, perseverance and diligence tried to achieve that goal.

They passed through many tests and trials but faced each ordeal with a smiling face without begging for mercy or seeking any dishonest means. their lives bear witness to the fact that labor, hard work, or diligence whether it is manual or mental pleasant or unpleasant is the only assurance or guarantee for a dignified and successful life. You can earn heaps of money by using dishonest and illegal means but this money can never earn you respect and dignity. A poor laborer who earns his living with his own hands is far more respectable than a millionaire who accumulates money through unfair means.

Money can give a dishonest person comforts in life but not a clean conscience and peace of mind. Peace is the lot of only the person who believes in the purity and dignity of work.

Our holy Prophet (PBUH) was the king of the kings. He could get every comfort and luxury of a life without doing any work himself. But he chose a dignified way of life. He worked as a shepherd and then as a merchant and earned his living by working with his own hands. Not only this but he also used to mend his clothes himself, clean his room, and do other domestic errands. His style of life lent dignity and importance to work. He advised his followers to work hard and not to feel shame in doing any kind of manual or menial work.

Idleness is like a moth that eats up a man's vitality and verve and makes him mentally mean and abject. The lazy and the work shirker do not hesitate from begging and even selling their honor for a few rupees. An idle person has no self-respect and so other people too do not respect him. It is said that an honorable death is better than a life full of humiliation and disgrace.

Some people consider manual work insulting and below their standards. They forget that it is manual work that translates mental work into reality and gives it a concrete form. the idea in mind is good but they are useful only when they are given some practical shape.

Work whether it is manual, menial, or mental is sacred if it is done with a good intention using honest means. Such work gives dignity, sobriety, and gravity to our personalities and leads us from one success to another.

Footer Social$type=social_icons

Student Essays

Essay on Dignity of Labour

The labor has a great dignity within itself. It’s the symbol of a man’s integrity and upright consciousness. The labor is done to achieve or earn things in life in a great meaningful and well acceptable ways. No one should be ashamed of doing labor. The following Essay on Labor talks about the meaning and concept of labor, reasons why labor has got great dignity and how we should promote the respect of labor among students etc.

Essay on Dignity of Labor | Meaning & Concept of Dignity of Labor Essay

The dignity is integrated instinct in human being. It is the sense of self-respect which we carry within ourselves. It is the feeling that we are not just animals, but human beings with a special quality, a spiritual component in addition to our physical makeup. The labour is an important activity to fulfill the instinct of dignity.

Labour is not just a physical activity. It is something that we do with our mind, body and soul. It is an activity that helps us to grow as human beings and to realize our potential. The satisfaction that we get from labour is not just material; it is also spiritual. When we do something with our hands, we feel a sense of accomplishment and pride. This is because we are using our God-given talents to make a contribution to society.

>>>>> Related Post: ” Essay on Feudalism & Its Impacts “

Why Labor has Dignity?

Labour is the source of all wealth. It is through labour that we create value and produce goods and services. It is the foundation of our economy and our society. Labour has dignity because it is the source of our sustenance and well-being. It is through labour that we provide for our families, build our homes, and create a better future for our children.

Labour also has dignity because it is an expression of our creativity and our humanity. When we work, we are using our minds and our bodies to create something new. We are using our talents and abilities to make a contribution to the world.

Labour has dignity because it is essential to our survival. We need to work in order to provide for our basic needs. We need to labour in order to build a better life for ourselves and our families. Labour has dignity because it is the key to human progress. It is through labour that we create wealth and improve our standard of living. It is through labour that we make our society more prosperous and more equitable.

Labour has dignity because it is a source of human fulfilment. It is through labour that we express our talents and abilities. It is through labour that we realize our potential. We should respect the labor. It is the foundation of our economy and our society. It is essential to our survival. It is the key to human progress. It is a source of human fulfilment. We should also respect the workers. They are the ones who make our economy and our society run. They are the ones who create wealth and improve our standard of living.

>>>>> Related Post: ” Essay on Poverty in India “

The dignity of labour is an important concept because it reminds us that all work has value. All work is essential to our survival, to our well-being, and to our progress as a society. All work is a source of human fulfilment. We should respect all forms of labour, and all workers, regardless of their occupation or social status.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Philosophical Approaches to Work and Labor

Work is a subject with a long philosophical pedigree. Some of the most influential philosophical systems devote considerable attention to questions concerning who should work, how they should work, and why. For example, in the ideally just city outlined in the Republic , Plato proposed a system of labor specialization, according to which individuals are assigned to one of three economic strata, based on their inborn abilities: the laboring or mercantile class, a class of auxiliaries charged with keeping the peace and defending the city, or the ruling class of ‘philosopher-kings’. Such a division of labor, Plato argued, will ensure that the tasks essential to the city’s flourishing will be performed by those most capable of performing them.

In proposing that a just society must concern itself with how work is performed and by whom, Plato acknowledged the centrality of work to social and personal life. Indeed, most adults spend a significant time engaged in work, and many contemporary societies are arguably “employment-centred” (Gorz 2010). In such societies, work is the primary source of income and is ‘normative’ in the sociological sense, i.e., work is expected to be a central feature of day-to-day life, at least for adults.

Arguably then, no phenomenon exerts a greater influence on the quality and conditions of human life than work. Work thus deserves the same level of philosophical scrutiny as other phenomena central to economic activity (for example, markets or property) or collective life (the family, for instance).