Edinburgh Research Archive

- ERA Home

- Philosophy, Psychology and Language Sciences, School of

Philosophy PhD thesis collection

By Issue Date Authors Titles Subjects Publication Type Sponsor Supervisors

Search within this Collection:

The PhD theses in this collection must be cited in line with the usual academic conventions. These articles are protected under full copyright law. You may download it for your own personal use only.

Recent Submissions

Objectification of women: new types and new measures , wisdom as responsible engagement:how to stop worrying and love epistemic goods , prescribing the mind: how norms, concepts, and language influence our understanding of mental disorder , humean constitutivism: a desire-based account of rational agency and the foundations of morality , predictive embodied concepts: an exploration of higher cognition within the predictive processing paradigm , impacts of childhood psychological maltreatment on adult mental health , epistemic fictionalism , thinking for the bound and dead: beyond man3 towards a new (truly) universal theory of human victory , function-first approach to doubt , abilities, freedom, and inputs: a time traveller's tale , concept is a container , analysing time-consciousness: a new account of the experienced present , emotion, perception, and relativism in vision , justice as a point of equipoise: an aristotelian approach to contemporary corporate ethics , asymmetric welfarism about meaning in life , mindreading in context , economic attitudes and individual difference: replication and extension , mindful love: the role of mindfulness in willingness to sacrifice in romantic relationships , embodied metacognition: how we feel our hearts to know our minds , temporal structure of the world .

- Help & FAQ

The dignity of persons : Kantian ethics and utilitarianism

- Lucas Sierra Vélez

Student thesis : Doctoral Thesis (PhD)

- Kantian ethics

- Utilitarianism

- Animal ethics

- Moral philosophy

- Moral standing

- Consequentialism

Access Status

- Full text open

Full text available in St Andrews Research Repository subject to embargo

- Youth Program

- Wharton Online

Ethics & Legal Studies

Wharton’s phd program in ethics and legal studies is unique: the only doctoral program in the world to focus on ethical and legal norms relevant to individual and organizational decision-making within business..

The Ethics & Legal Studies Doctoral Program at Wharton trains students in the fields of ethics and law in business. Students are encouraged to combine this work with investigation of related fields, including Philosophy, Law, Psychology, Management, Finance, and Marketing. Students take a core set of courses in the area of ethics and law in business, together with courses in an additional disciplinary concentration such as management, philosophy/ethical theory, finance, marketing, or accounting. Our program size and flexibility allow students to tailor their program to their individualized research interests and to pursue joint degrees with other departments across Wharton and Penn. Resources for current Ph.D. students can be found at http://www.wharton.upenn.edu/doctoral-inside/ .

Our world-class faculty take seriously the responsibility of training graduate students for the academic profession. Faculty work closely with students to help them develop their own distinctive academic interests. Our curriculum crosses many disciplinary boundaries. Faculty and student intellectual interests include a range of topics such as:

- Philosophy & Ethics : • philosophical business ethics • normative political philosophy • rights theory • theory of the firm • philosophy of law • philosophy of punishment & coercion • philosophy of deception and fraud • philosophy of blame and complicity • climate change ethics • effective altruism • integrative social contracts theory • corporate moral agency

- Law & Legal Studies : • law and economics • corporate penal theory • constitutional law • bankruptcy • corporate governance • corporate law • financial regulation • administrative law • empirical legal studies • blockchain and law • antitrust law • environmental law and policy • corporate criminal law • corruption • negotiations.

- Behavioral Ethics : • neuroscience and business ethics • moral psychology • moral beliefs and identity • moral deliberation • perceptions of corporate identity

Our program prepares graduates for tenure-track careers in university teaching and research at leading business schools and law schools. We have an excellent record of tenure-track placements, including Carnegie Mellon University, Notre Dame University, and George Washington University. Click here to see our placements .

Sample Schedule

Core courses.

In addition to the Wharton Doctoral course requirements, the student’s four-course unit core in the Legal Studies and Business Ethics Department consists of two required doctoral seminars, LGST 9200 Ethics in Business and Economics, and LGST 9210 Foundations of Business Law. The remaining two LGST courses may be selected from a list of LGST courses that the faculty coordinator has approved.

Students without basic law courses will be required to take LGST 1010 in their first semester. Students will take LGST courses, other than Ph.D. seminars, under an independent study number, meet with the instructor periodically outside class, and write a paper. These requirements should be satisfied through courses taught by members of the LGST standing faculty, though exceptions will be made in special circumstances. The requirements may be adjusted for students with law degrees.

Ethics and Law in Business Courses

Students must take four LGST courses, including these two core course seminars:

- Ethics in Business and Economics (LGST 9200)

- Foundations of Business Law (LGST 9210)

Major Disciplinary Cluster

The purpose of the cluster is to ground students in a single academic specialty other than Business Ethics. Clusters include the following:

Students must choose a disciplinary cluster during the first year, in consultation with a faculty advisor. Required courses may not be double-counted. For example, a student choosing Philosophy as the cluster may not use the two required courses in ethical theory as part of the five course cluster requirement.

Get the Details.

Visit the Ethics & Legal Studies website for details on program requirements and courses. Read faculty and student research and bios to see what you can do with an Ethics & Legal Studies PhD.

Ethics & Legal Studies Doctoral Coordinator Brian Berkey Associate Professor of Legal Studies & Business Ethics

Academic & Business Administrator Tamara English Legal Studies and Business Ethics Department Email: [email protected]

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- JME Commentaries

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 36, Issue 7

- Research ethics in dissertations: ethical issues and complexity of reasoning

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- S Kjellström 1 ,

- S N Ross 2 , 3 ,

- B Fridlund 4

- 1 Institute of Gerontology, School of Health Sciences, Jönköping University, Jönköping, Sweden

- 2 Antioch University Midwest, Yellow Springs, Ohio, USA

- 3 ARINA, Inc., Cincinnati, Ohio, USA

- 4 Department of Nursing, School of Health Sciences, Jönköping University, Jönköping, Sweden

- Correspondence to Sofia Kjellström, Institute of Gerontology, School of Health Sciences, Jönköping University, PO Box 1026, SE-551 11 Jönköping, Sweden; sofia.kjellstrom{at}hhj.hj.se

Background Conducting ethically sound research is a fundamental principle of scientific inquiry. Recent research has indicated that ethical concerns are insufficiently dealt with in dissertations.

Purpose To examine which research ethical topics were addressed and how these were presented in terms of complexity of reasoning in Swedish nurses' dissertations.

Methods Analyses of ethical content and complexity of ethical reasoning were performed on 64 Swedish nurses' PhD dissertations dated 2007.

Results A total of seven ethical topics were identified: ethical approval (94% of the dissertations), information and informed consent (86%), confidentiality (67%), ethical aspects of methods (61%), use of ethical principles and regulations (39%), rationale for the study (20%) and fair participant selection (14%). Four of those of topics were most frequently addressed: the majority of dissertations (72%) included 3–5 issues. While many ethical concerns, by their nature, involve systematic concepts or metasystematic principles, ethical reasoning scored predominantly at lesser levels of complexity: abstract (6% of the dissertations), formal (84%) and systematic (10%).

Conclusions Research ethics are inadequately covered in most dissertations by nurses in Sweden. Important ethical concerns are missing, and the complexity of reasoning on ethical principles, motives and implications is insufficient. This is partly due to traditions and norms that discount ethical concerns but is probably also a reflection of the ability of PhD students and supervisors to handle complexity in general. It is suggested that the importance of ethical considerations should be emphasised in graduate and post-graduate studies and that individuals with capacity to deal with systematic and metasystematic concepts are recruited to senior research positions.

- Research ethics

- human development

- dissertation

- graduate education

- applied and professional ethics

- scientific research

https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.2009.034561

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Research has a potential to encroach on people's lives, autonomy and integrity. To prevent or mitigate the potential for such effects, the research community has created ethics codes and regulations, institutionalised ethics review boards and formalised ethics requirements in scientific journals. 1–3 However, how do we know whether the formalisations of research ethics actually result in researchers' ability to operationalise ethics in the ways intended? One way is to analyse how they write about research ethics.

Including a well-written section about research ethics in a dissertation is important for several reasons. Compared to protocols written for research ethics committees, this section allows a comparison of the expected and actual research ethics as reflected in the entire research process. Scientific journals increasingly require that ethical considerations are elucidated, but most journals severely limit space for elaboration. 4 Since studies have questioned the ethical skills of doctoral students, dissertations provide a forum for students to expound on ethics and enable an assessment of acquired proficiencies. One purpose of graduate school is to train doctoral students in skills necessary for future research careers, including more critical thinking and more complex reasoning. The quality and depth of the research ethics section is essential to examine whether a researcher has acquired necessary skills to reflect and report on ethics.

Despite an increasing interest in research ethics, surprisingly little is known about the quality of research ethics in dissertations, particularly in nursing research. Research on written materials focuses primarily on research review boards 5–9 and journals—for example, ethics guidelines 10 and research ethics in articles. 4 Research on Turkish nursing dissertations showed deficiencies in informing participants and protecting privacy. 11 A study on Swedish nurses' dissertations from 1987 to 2007 showed that an increase in occurrence and proportions of reported ethical considerationsand that the texts were short, had few references and covered a narrow range of topics. 12 We found no other studies that address the design of the research ethics section and how different topics were combined.

The study's purpose was to examine which research ethical topics were addressed and how these were presented in terms of complexity of reasoning in Swedish nurses' dissertations approved in 2007. The research questions were: Which research ethics issues are reported? How is the research ethics section organized around different ethical issues? How is the information coordinated in terms of the complexity of reasoning that structures the text? What is the relationship between ethical issues and complexity of reasoning in the text?

Design and methodological approaches

The study used a mixed-methods approach to address the four research questions. 13 We performed a qualitative content analysis and a quantitative analysis of the hierarchical complexity of ethics-related content. The quantification method was the Hierarchical Complexity Scoring System (HCSS) (Commons, et al , unpublished manual), which derives from the Model of Hierarchical Complexity, a mathematics-based, formal general theory applicable to all actions in which information is organised. 14 15 All reasoning involves organising information. The theory and validated scoring method enable reliable measures of discrete stages of reasoning complexity. 16–20 In accord with Swedish law, ethical approval was not obtained for this study, 21 but ethical principles were used and issues were addressed in ongoing reflective processes.

Data collection

The sample consisted of 64 dissertations from Swedish universities in 2007 (Appendix 1). The primary inclusion criteria were that the dissertation was written by a nurse and that it was a PhD dissertation (4 years of full-time studies). Suitable dissertations were identified from the Swedish Society of Nursing's list of self-reported dissertations (n=65) followed by a systematic comparative analysis with the Swedish National Library (n=1). One of the self-reported dissertations discussed no research ethics and one was by an unsuccessful doctoral candidate: they were not included in the sample. Dissertation languages were English (n=48), Swedish (n=15) and Norwegian (n=1). Dissertations were retrieved via full-text online access or as books from the university library.

Data analysis

The dissertations were examined to identify research ethics sections, often under the subheadings “Ethical considerations” or “Ethical approval”. The texts were analysed for the topics addressed and how they were reported. An unstructured matrix of research ethics issues was created and grounded in the data. The coded texts were further analysed for subcategories through an inductive process. Descriptions of meanings of quantitative and qualitative character, that is manifest and latent content analysis, were sought. The analysis was performed by SK with BF—with extensive experience in qualitative methods.

In hierarchical complexity scoring, such content is “seen through” to examine its underlying structure. The method measures the levels of abstraction and how information is coordinated. Each section and subsection of a research ethics discussion was assessed on stage of hierarchical complexity. The overall discussion was scored based on the highest stage of performance the text demonstrated. The correlation of content and its complexity indicated which topics were addressed at different stages of complexity. Scoring was performed independently by SK and SR, then discussed to reach consensus. Both authors scored the English texts, and SK scored the ones in Scandinavian languages and discussed with SR. SR is an expert HCSS stage-and-transition scorer while SK is a qualified HCSS scorer of stages 8 through 11. See table 1 for stage complexity information. 22

- View inline

Common range of stages of performance in adult tasks' hierarchical complexity

Research ethics issues in dissertations

Dissertations contained one to seven research ethics topics: approval of research ethics board (94%); information process and informed consent (86%); confidentiality (67%); ethical aspects of methods (61%); use of ethical principles and regulations (39%), rationale for the study (20%) and fair participant selection method (14%; table 2 ). All but three of the dissertations involved direct interaction with study participants; three were register-based studies.

Design of research ethics sections in Swedish nurses' dissertations

Ethics approval

The ethics approval category included descriptions of whether the dissertation has been vetted by an ethics review board. Almost all dissertations included a discussion of ethics approval (n=60), and a majority stated they had been approved by a research ethics review board (n=55). A quality and transparency concern was that several sections included no name of the ethics board and/or registration number (n=13). A minority related the issue of ethics approval to ethical codes, the Helsinki declaration or current national research ethics laws (n=14) by either stating that studies were performed in accordance with ethics regulations (n=8) or by arguing against the need for an ethics approval due to national laws (n=6).

Information and informed consent

We broadened the traditional informed consent category to accommodate information-giving processes discussed but not always expressed in terms of informed consent. Most dissertations discussed information-giving and informed consent (n=56). A third of these explicitly mentioned the concept of informed consent (n=19). A substantial amount of space was typically used to detail the informing phase of research, including the information's form (written and/or verbal) (n=41) and type. The most often-given information was freedom to withdraw from the study (n=33) and a declaration of voluntariness (n=30). Other information included confidentiality (n=22), withdrawals' non-interference with further treatment (n=7), the right to not answer questions (n=4), aim of the study (n=2), risks and benefits (n=2) and feedback of results (n=1). Those responsible for providing information as well as those receiving the information were described. Some informed consent discussions included an ethical rationale for the information process by referring to principles, codes or laws (n=16).

Confidentiality

Items coded in the confidentiality category reported that information was accessible to only authorised persons. Confidentiality procedures were succinctly reported (n=43). Besides describing confidentiality as something that participants were guaranteed and informed about, some researchers identified how confidentiality had been handled: data were safely stored protecting participant's identity (n=12); data were analysed and reported without identifying participants (n=19) and participants in focus group interviews were counselled in ways to promote freedom of expression and confidentiality (n=2).

Ethical aspect of the methods

The category for ethical aspect of the methods included the research ethics issues in collecting data, except for questions regarding informing participants. Ethical aspects of study methods were comprised of descriptions of interviews and questionnaires (n=37). Explanations of why interviews were ethically problematic were done by referring to principles or risks of harm (n=17). The negative aspects stated (n=24) were physical and psychological with an emphasis on emotional. Strategies to impede negative consequences were depicted (n=20): adopt a sensitive attitude, adapt to the physical and mental status of the interviewee, reduce questions, provide time to reflect on the interview and arrange for a contact person. Sometimes, statements about how the participants seemed to enjoy the interview experience were included (n=14). A few sections described problems that appeared during the research interview (n=14)—for example, interviewees who cried or did not answer all questions. The most comprehensive sections covered all these issues, but the most common strategy was to mention the potential laboriousness of the interview yet argue that participants benefited from practical solutions that were provided in the interview situation or by claiming that research participants appreciated the opportunity to tell their stories. The reported ethical problems with questionnaires were primarily the tedium of answering questions and how researchers adjusted the number of requests for completion out of respect and concern for participants' possible fatigue.

Use of ethical principles and regulations

Discussions that included the usage of principles and ethical regulations like laws and research ethics codes were coded to the category of ethical principles and regulations. This category was analytically different from others because it revealed how ethics were applied in the research sections. Explicit report of laws, ethics codes and principles occurred in fewer than half of the dissertations (n=25). Principles were employed but performed in qualitatively different ways (n=17). The simplest form was to state that the study had been performed in accordance with a research ethics declaration, code or rules outlined in a research ethics book. The most elaborate ones integrated the principles and described how they were used as compasses for research procedures (n=8).

Rationale for the study

To provide an ethical rationale for the study means to justify why the study is important in a wider perspective. Thirteen dissertations featured an ethical rationale for the study, and when included, it was framed in terms of risks and benefits. The need for new and valuable knowledge that could potentially improve conditions for other people weighed heavier than the extra demand and little direct gain that the research subjects gained from participating. Some reported that the value of pursuing the research outweighed the disadvantages but entailed the necessity of protecting the autonomy of the research participants.

Fair participant selection

Fair selection of participants signifies reflections on a justified choice of participants. The reason to include vulnerable groups and groups that previously has been excluded from research was sometimes given (n=9). A few sections justified the choice of participants (n=8). The importance of including important and vulnerable groups so their voices would be heard was the main reason reported.

Design of the research ethics section

The topics of the research ethics sections are outlined in table 2 . Most frequent was to report four ethics issues (n=16), followed by three (n=14) or five issues (n= 14). The majority (72%) included 3–5 issues. Four sections stated one topic and only one dissertation section reported seven issues. The most common composition of a section about research ethics discussed five topics: the approval from a research review board, information and informed consent, ethical aspects of the methods, confidentiality and principles.

Complexity of reasoning

The analysed texts demonstrated three stages of performance as measured by hierarchical complexity: abstract (n=4), formal (n=54) and systematic (n=6).

Abstract stage text performances consisted of declarative statements ( table 3 ). Unsupported categorical assertions were made and justified by invoking another assertion. Generalisations were created by quantifying people and events. Often-used quantifications in the sample were “all participants” and “all studies”. Research ethics sections included mainly generalisations about actions that had been performed.

Representative examples of reasoning in research ethics at three stages of complexity

Reasoning at the formal stage of performance used empirical or logical evidence ( table 3 ). Assertions were supported by explicit logic or evidence to justify the assertion—for example, by providing a logical explanation—for example, using such terms as because, in order to, since, if, then, therefore. Descriptions of hypothetical or alternative options in the future were sometimes included. The logic was linear. Such linear logic took the form of if–then constructions or chains of logic. Some used principles as logical reasons for actions.

Systematic stage performances were characterised by the ability to coordinate at least two logical relations into a system ( table 3 ); in other words, they demonstrated reasoning about complex causation and ability to understand a system of logical relationships. For example, one researcher described procedures for finding the “right people” by invoking a multivariate system that required the coordination of multiple variables. Systemic stage performances were characterised by more fluid reasoning than the linear, logical performances.

Comparing content and complexity

Few dissertations demonstrated abstract reasoning and systematic reasoning, four and six, respectively, but showed interesting patterns. The texts with abstract stage reasoning reported either one or two topics. All four mentioned approval; information and methodological issues were raised by only two. Texts with systematic reasoning introduced three to five ethical issues. Half of them discussed principles (as compared to merely citing a principle as the reason for an action), and the other three reported the rationale for the study, indicating that the topic and study could perhaps be viewed in a wider context. Among the majority of texts demonstrating formal reasoning, the topics varied from one to seven, meaning at least formal reasoning was needed to explain all conceivable aspects. Formal reasoning is required to report such tasks as fair selection of participants, rationale for the study and principles, ethics codes and laws.

Our study demonstrates that research ethics are insufficiently reported and inadequately described in many nursing dissertations. Few ethical topics are considered, and they are not discussed in a thorough way. While most note official approval and describe informed consent issues, other issues like the rationale for the study and how the participants were selected are infrequently reported. The level of complexity of reasoning was inadequate in most dissertations. The majority of the dissertations used formal reasoning, although by their nature, the ethical issues introduced in them require more complex reasoning to be satisfactorily addressed.

A methodological strength of our study is its inclusion of a large number of dissertations, which are likely representative of dissertations by Swedish nurses. A major advantage of our method is that the analytical approach permits assessments and comparisons of the coverage of ethical issues and the complexity of reasoning.

A methodological shortcoming is that the analysis was primarily focused on the section denoted “Ethical considerations/approval”, thus some ethics topics and reasoning might have passed undetected if they were treated in other parts of the dissertation. The analysis is thus limited to what the authors define as belonging to ethics sections. Our analysis identified the most complex stage of reasoning as a criterion for analysis because ethical considerations are complex matters. A more extensive analysis could have also analysed the entire low to high range of reasoning demonstrated in each ethics section. An implication of the language analyses is that we do not know which and how the ethical issues were applied in reality. Some issues could have been omitted from the dissertation text even though the issue was dealt with in practice and vice versa. The consistency between writing about ethics and ethical behaviour in the field—for example, in contact with research subjects and patients, should be investigated in future studies.

The first main finding is the incompleteness of the elaboration of topics and details in several dissertations, which is consistent with several studies in the domain of research ethics. A previous study showed a high level of errors in research ethics committee letters; that is, procedural violations, missing information, slip-ups and discrepancies. 8 Earlier research on Swedish nurses' dissertations demonstrate the questionable quality due to short length, few references and a narrow range of topics. 12

In our study, few topics were addressed. Emanuel et al argued for seven requirements to be considered and met in the conduct of ethical research: scientific value, validity, fair subject selection, favourable risk–benefit ratio, independent review, informed consent and respect for potential and enrolled subjects. 23 Applied to our findings, some requirements may be treated in other parts of a dissertation, but several dissertations leave out topics that are necessary for judging their ethical quality.

Informing potential participants and pursuing informed consent was reported in almost 90% of the dissertations' ethics sections. This frequency is higher than that reported in a study of Turkish nurses' dissertations where subjects were not informed about the study (72.7%) and the researchers had not obtained permission from the subjects (73.6%). 11

The second main finding is the insufficient level of complexity of reasoning, with which research ethics are handled. Findings from a discourse analysis of research ethics committee letters showed that there was “the lack of formal reasoning” (p 258) and ethical arguments—for example, informed consent are described as procedural norms rather than an ethics principle possible to dispute. 9 This is consistent with our findings, because a significant number invoked research ethics principles to justify procedures taken, rather than to use principles to support ethical arguments for and against certain procedures. However, our findings also showed that the great majority used at least some formal reasoning, as measured by hierarchical complexity.

Unfortunately, formal reasoning is necessary but not sufficient for adequacy in ethical matters. The analysis showed that formal reasoning and systematic reasoning were needed to elaborate on topics, and the comparison of complexity reasoning and content indicated that higher levels of reasoning involved more elaborated use of ethics principles. Very few used systematic reasoning, and none used metasystematic, which would be preferable because several of the research ethics concepts are metasystematic stage principles. For example, informed consent is a metasystematic stage concept because it coordinates the system of informing a research subject and the system of obtaining consent from the person. 24 This means that metasystematic reasoning is needed for a full understanding and use of these concepts.

What are possible explanations for the low levels of reasoning on research ethics? One possibility is that ethical issues are dealt with at a sufficiently high level of complexity in practice, whereas the text of the dissertation merely reflects a research tradition that discounts the importance of performing and explaining ethical reasoning. Disciplinary norms for terse writing styles are presumably promoted by supervisors and department guidelines. For example, nurses' dissertations in social science use more references to methods, ethics and philosophy of science than dissertation in the medical science tradition. 23 In addition, poor writing may occur because researchers mimic previous dissertations or regard ethical considerations as bureaucratic hurdles rather than moral requirements to protect participants. The supervisor role is an important factor since they sometimes acknowledge a considerable lack of knowledge about research ethics. 25 Another conceivable explanation is that the level of ethical reasoning corresponds rather accurately to the level of complexity the doctoral students and their supervisors use to handle complex issues in general. In other words, they are arguing on ethical issues at their highest complexity level. In that case, the scientists' (PhD students' and supervisors') ability to discuss at more complex levels must be improved for ethical issues to be sufficiently managed in the future. All these possibilities suggest further research is needed to account for our findings, since ethics have long been an important part of nurses' education and occupation.

There are several implications of insufficient ethical reasoning. Integrity of the research subjects and patients are at risk, and patients, if they participate, may be informed without understanding the implications. From the perspective of the readers of the scientific literature, it is impossible to assess how and why the authors dealt with various ethical issues. A crucial implication is the consequences of selection of research questions, methods and participants/sample. Scientists performing at abstract or formal stages are less likely to integrate relevant ethical aspects into their research aims than scientists at higher complexity levels. This is because such integration, by its nature, is multivariate at minimum. They will differ quite dramatically in the way they understand principles as principles, “risks” and “benefits”, rationale of the investigation, etc. Researchers with systemic or metasystematic stage reasoning are able to ask more complex questions, juggle ethics, research questions, and methods and design more complex research projects. 26

Our conclusion is that if the established praxis to include discussion of research ethics in Swedish nurses' dissertations is going to be valuable, and if its purpose is to indicate that the research complied with expected ethics, then the reporting must exhibit a certain quality, comprehensiveness and sufficiently significant treatment of ethics. Our study illustrates that factors that improve the quality include: appropriately thorough consideration of several ethical issues while avoiding minutiae; use of ethical principles in appropriate contexts to justify choices and reasons to support actions taken and use of at least formal and systematic reasoning. In addition, we would like to see more reflection and a critical stance to what has been done in the dissertation work.

In order to accomplish the intent of reporting research ethics, several improvements are needed. The most straightforward solution is to enhance the research ethics teaching in graduate education. Students must learn how to perform ethically sound research from the first steps of planning and performing to writing up the results and their potential and ability to report and reflect on ethical aspects of the research process must be enhanced. A more profound resolution is to emphasise metasystematic thinking in post-graduate studies and recruit senior researcher and post-graduate students who already have developed a systematic or metasystematic way of reasoning. This longer-term solution will also constitute the foundation for further development of complexity in handling ethics issues in the future.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank professor Per Sjölander for valuable comments on the discussion.

- Emanuel EJ ,

- Wendler D ,

- Dixon-Woods M ,

- Ashcroft RE

- Finlay KA ,

- Fernandez CV

- Angell EL ,

- Jackson CJ ,

- Ashcroft RE ,

- Dixon-Woods M

- O'Reilly M ,

- Rowan-Legg A ,

- Ulusoy MF ,

- Kjellström S ,

- Creswell JW

- Commons ML ,

- Smith JEV ,

- Goodheart EA ,

- Dawson TL ,

- Swedish law

- Rodriguez JA ,

- Szirony TA ,

- Richards FA

Supplementary materials

Web only appendix.

Files in this Data Supplement:

- web only appendix

Competing interests None.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Other content recommended for you.

- 3D bioprint me: a socioethical view of bioprinting human organs and tissues Niki Vermeulen et al., Journal of Medical Ethics, 2017

- Towards a European code of medical ethics. Ethical and legal issues Sara Patuzzo et al., Journal of Medical Ethics, 2016

- Strengthening ethics committees for health-related research in sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review protocol Val Thurtle et al., BMJ Open, 2021

- Ethical navigation of biobanking establishment in Ukraine: learning from the experience of developing countries Oksana N Sulaieva et al., Journal of Medical Ethics, 2023

- A comparative analysis of biomedical research ethics regulation systems in Europe and Latin America with regard to the protection of human subjects Eugenia Lamas et al., Journal of Medical Ethics, 2010

- Understanding ethics guidelines using an internet-based expert system G Shankar et al., Journal of Medical Ethics, 2008

- The experiences of ethics committee members: contradictions between individuals and committees L Elliott et al., Journal of Medical Ethics, 2008

- Beyond regulatory approaches to ethics: making space for ethical preparedness in healthcare research Kate Lyle et al., Journal of Medical Ethics, 2022

- Proportional ethical review and the identification of ethical issues D Hunter, Journal of Medical Ethics, 2007

- How not to argue against mandatory ethics review David Hunter, Journal of Medical Ethics, 2012

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- JMIR Res Protoc

- v.9(1); 2020 Jan

Examining the Ethical Implications of Health Care Technology Described in US and Swedish PhD Dissertations: Protocol for a Scoping Review

Jens m nygren.

1 Halmstad University, Halmstad, Sweden

Hans-Peter de Ruiter

2 Minnesota State University, Mankato, MN, United States

The development of new biomedical technologies is accelerating at an unprecedented speed. These new technologies will undoubtedly bring solutions to long-standing problems and health conditions. However, they will likely also have unintended effects or ethical implications accompanying them. It may be presumed that the research behind new technologies has been evaluated from an ethical perspective; however, the evidence that this has been done is scant.

This study aims to understand whether and in what manner PhD dissertations focused on health technologies describe actual or possible ethical issues resulting from their research.

The purpose of scoping reviews is to map a topic in the literature comprehensively and systematically to identify gaps in the literature or identify key evidence. The search strategy for this protocol will include electronic databases (eg, ProQuest, PubMed, Diva, SwePub, and LIBRIS). Searches will be limited to PhD dissertations published in the United States and Sweden in the last 10 years. The study will be mapped in 5 stages: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) retrieving and charting the data, and (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results.

The findings of this study will indicate if and how researchers, PhD students, and their supervisors are considering ethics in their studies, including both research ethics and the ethical implications of their work. The findings can guide researchers in determining gaps and shortcomings in current doctoral education and offer a foundation to adjusting doctoral research education.

Conclusions

In a society where technology and research are advancing at speeds unknown to us before, we need to find new and more efficient ways to consider ethical issues and address them in a timely manner. This study will offer an understanding of how ethics is currently being integrated into US and Swedish PhD dissertations and inform the future direction of ethics education at a doctoral level.

International Registered Report Identifier (IRRID)

PRR1-10.2196/14157

Introduction

The importance of understanding the ethical implications of new health technologies is more important now than ever owing to the accelerated speed in which it is developing. Having insight into the possible ethical implications of new health technologies enhances research and development, thereby increasing the likeliness of successful implementation in clinical practice. It may be presumed that the findings presented in dissertations have been evaluated from an ethical perspective; however, evidence that this is the case is scant. This review protocol is developed to evaluate to what extent and how ethical issues are being addressed in PhD dissertations that focus on health technologies. This can give insight into and steer what ethical and moral education would prepare future researchers and academics for recognizing and addressing ethical issues. The proposal builds on a 2-year grant that focused on evaluating and integrating ethics when developing new health technologies [ 1 ].

The development of new technologies is accelerating at an unprecedented speed. It is predicted that in the next century, our earth will experience as much change as we have in the preceding 20,000 years [ 2 ]. These technological changes will also include medical advances such as electronic health, robotics, genomics, bioinformatics, nanotechnology, and numerous others [ 3 , 4 ]. This will undoubtedly bring solutions to long-standing problems and health conditions. However, they will likely also have a shadow side in the form of unintended effects or ethical implications accompanying them [ 5 ]. Owing to the rate at which technology is advancing, bioethics is falling further and further behind in staying current with new evolving issues. This is mainly because examining ethical issues has historically occurred retrospectively, which is a slow process [ 6 , 7 ]. Developers of new health technologies should thus be integrating ethical discernment early on in the development and research phase.

Much has been written, discussed, and taught about the importance of performing health research involving human subjects in an ethical manner and in accordance with strict guidelines [ 8 - 10 ]. In addition, medical and health journals should no longer publish research that has not gone through an ethical review by an independent ethics board [ 11 ]. These ethical review boards limit their review to the ethics of the study itself by reviewing issues such as informed consent, coercion, and risks or benefits to study participants. Research ethics and the role of the ethical review boards limit themselves exclusively to the ethical nature of research studies and do not consider possible ethical and unintended effects resulting from the research findings after the study has been completed. Efforts have been made in teaching and socializing [ 12 ] ethical and moral thinking and behaviors as a part of doctoral education [ 13 - 15 ]; however, the impact of those efforts remains to be determined. A number of studies have focused on the extent that research ethics is discussed in PhD dissertations and found deficiencies in the extent that the ethics pertaining to the study method was addressed [ 16 - 18 ]. The primary focus of this study is to evaluate the extent to which PhD students have addressed the ethical implications of their work, not only limited to the study method.

To be proactive in anticipating and understanding the ethical implications of these new developments, research ethics should be considered from each study's conception. A researcher’s awareness of possible ethical implications will allow him or her to respond proactively and address issues at an early stage, which points toward the importance of developing this awareness and capability to respond already during the postgraduate training of new researchers. To obtain an understanding of this practice, this study will analyze dissertations that pertain to health technology and analyze to what extent ethical implications are discussed and how they are addressed. As PhD students work with advisors/supervisors and dissertation committees, the findings from this study will also give a general insight into how senior academic researchers understand and value the ethical implications of research. Thus, this study does not intend to be a comprehensive overview of specific ethical issues in health technologies nor offer a comprehensive overview of all technologies; instead, it will focus on giving preliminary insights into what extent doctoral students are incorporating ethics in their work. This information is essential to identify if educational changes need to be made in doctoral education to allow for a more proactive approach to identifying the ethical and unintended effects of one’s research.

This study aims to understand in what manner and whether PhD dissertations focused on health technologies describe actual or possible ethical issues resulting from their research. This study will examine US and Swedish PhD dissertations with the future objective of showing the applicability of the protocol in other countries.

Study Design

The method of inquiry for this study will be a scoping review based on a study by Arksey and O’Malley [ 19 ] comprising 5 stages: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) retrieving and charting the data, and (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results.

Stage 1: Identifying the Research Question

In the context of scoping reviews, maintaining a broad approach in the first instance improves the possibility to generate a breadth of coverage and allows setting parameters based on the scope and volume of references generated. For this scoping study, the overarching research question is the following:

Are US and Swedish PhD dissertations researching health care technologies addressing possible ethical implications of their research findings, and if so how?

Answering this question will not only require a thorough examination of the extent to which PhD students are considering possible ethical issues during the design phase of their study but also if and how the ethical implications of their research findings are discussed in their dissertation.

For this study, we will use the definition of technology as defined by Jacques Ellul as the underlying ethical framework and theory [ 20 ]. Ellul argues that the basis of all technologies are techniques, systems that make a process more efficient [ 20 ]. Technologies are typically devices or systems that automate 1 or more techniques. On the basis of this view, this proposal considers technology to be broader than mere electronic devices and equipment and also include techniques such as health economics, risk management, health quality assurance, and genomics [ 20 ]. The importance of understanding the impact of techniques and technology, such as the ethical implications, is thus crucial in fully comprehending the full effect of new technologies. A list of technologies ( Textbox 1 ) presented in the World Health Organization (WHO) report, “Human Resources for Medical Devices, the Role of Biomedical Engineers” [ 21 ], will be used to identify current technologies and techniques used worldwide. The WHO listing was selected because of the comprehensive nature and scope of technologies and techniques. The list includes not only devices but also techniques to help manage health care delivery, which is in line with the definition of technology and technique as identified by Ellul [ 20 ]. To confirm the validity of using these terms concerning ethics and health care technologies, we will perform a search among all original peer-reviewed publications written in English and listed in PubMed in the period 2009 to 2019. The search will explore to what extent publications are mentioning ethics accompanying technologies. The following searches will be performed:

Subspecialisms of biomedical engineering.

Research and development

1. Biomechanics

2. Biomaterials

3. Bioinformatics

4. Systems biology

5. Synthetic biology

7. Biological engineering

8. Nanotechnology

9. Genomics

10. Population health or data analytics

11. Computational epidemiology

12. Intellectual property innovation

13. Theranostics

14. Biosignals

Rehabilitation

15. Artificial organs

16. Neural engineering

17. Tissue engineering or regeneration

18. Mechatronics

19. Assistive devices

20. Rehabilitation software

21. Prosthetics

Application and operation: clinical engineering

22. Technology management

23. Health quality assurance

24. Health regulatory assurance

25. Health education and training

26. Ethics committee

27. Clinical trials

28. Disaster preparedness

29. eHealth

30. Telemedicine

31. mHealth

32. Wearable sensors

33. Health economics

34. Health systems engineering

35. Health technology assessment or evaluation

36. Health informatics

37. Service delivery management

38. Field service support

39. Heath and security

40. Heath and privacy

41. Heath and cybersecurity

42. Forensic engineering or investigation

43. Manufacturing QMS

44. Manufacturing GMP

45. Medical imaging

46. Project management

47. Robotics

48. Virtual environments

49. Risk management

50. EMI compliance

51. EMC compliance

52. Technology Innovation strategies

53. Population- and community-based needs assessment

54. Engineering asset management

55. Environmental health

56. Systems science

- Term of technology in title or abstract

- Term of technology + ethics or unintended effects in text

- Term of technology + ethics or unintended effects in title or abstract in text.

Findings will be entered into a matrix describing the number of articles identified by each search combination. A total of 168 searches (56 terms x 3 searches) will be performed during this stage.

Stage 2: Identifying Relevant Studies

To identify dissertations as comprehensively as possible for answering the research question of this study, the search strategy will involve searching broadly via multiple sources. Electronic databases will primarily be used, but other sources will be considered in the context of practicability. The following databases will be prioritized, based on topic and coverage:

- ProQuest Dissertations and Theses—contains dissertations and theses from over 1000 North American and European universities (only a limited number of Swedish universities are indexed in ProQuest and the use of ProQuest will be limited to US dissertations).

- LIBRIS—the national catalogue for Swedish PhD dissertations covering a substantial part of all the books and periodicals published in Sweden from the 16th century onward.

- SwePub—contains references to research publications from approximately 40 Swedish universities and other publication databases. Selection and extent vary among contributing universities and authorities.

- DiVA portal—an institutional repository for research publications and student theses written at 47 universities and research institutions in Sweden.

To identify dissertations that refer or mention ethics in relation to technology or techniques defended in the US and Sweden during the last 10 years, each database will be searched for the terms used by WHO in the report, “Human Resources for Medical Devices, the Role of Biomedical Engineers” [ 21 ] ( Textbox 1 ). The following search strategy will be used:

- Term of technology

- Term of technology + ethics in title or abstract

- Term of technology + ethics in text

Stage 3: Selecting Studies

Unlike systematic reviews, inclusion and exclusion criteria in scoping reviews are developed posthoc, once there is familiarity with the literature. However, all dissertations written in a language other than English or Swedish will be excluded. Our focus is on PhD dissertations researching a technique or technology intended to improve or impact the health of individuals or a population. This will include health treatments, diagnostic and testing equipment, health monitoring systems, and quality assurance and health economics systems. Even though we anticipate most dissertations to be from health sciences such as medicine, nursing, and physical therapy, other disciplines will also be included as indicated to assure an accurate and comprehensive overview.

Stage 4: Retrieving and Charting the Data

The process for classifying and synthesizing the data retrieved involves 2 steps: first, to map how the dissertations are distributed according to the search terms, that is, technology and technique terms and ethics, and second, to map in relevance to the research question.

Charting the data retrieved will involve classifying and synthesizing the data identified in the dissertations. The steps for mapping the data will be the following:

- Step 1.0—Map the distribution of dissertations among the 56 search terms (from the WHO human resources for medical devices report) for technologies and techniques

- Step 2.0—Map publication years, disciplines, and names of universities

- Step 2.1—Map dissertations into groups describing different topic areas

- Step 2.2—Map the extent of mentioning and elaboration of ethics in the dissertations.

Selected and included dissertations will be manually assessed by using a self-developed Dissertation Ethics Assessment Tool recording; 1) year, 2) discipline, 3) name of University, 4) topic area, 5) discussion of research ethics “Quotations of texts”, 6) discussion of unintended effects of ethical issues of the research findings “Quotations of texts”, 7) suggestions regarding ethics or unintended effects offered “Quotations of texts”, and 8) comments. Data coding and categorization will be performed by 2 researchers independently, and findings will be compared and discussed. When there is a difference in assessment, the researchers will discuss to come to a consensus. If no consensus is achieved, the dissertation will be excluded from the study.

Stage 5: Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

Processing of the results in a scoping review does not emphasize the level or quality of evidence presented, but instead develops a thematic framework based on the existing literature relating to the research question. This study will focus on the sections found in the dissertations that pertain to (1) research ethics and (2) ethical implications of the research that are described.

This will be qualitatively analyzed by using the Web-based research tool, Covidence. Any sections from dissertations that mention ethics will be entered into Covidence for coding and analysis purposes. After the data are entered, data analysis will be based on the work of Cobin et al [ 22 , 23 ]. First, qualitative data analysis will focus on identifying codes, phrases, or words with an objective to organize the data. Second, a unified coding system will be developed, and codes will be collapsed into categories while continuing to code the data when relevant. Finally, the categories will be abstracted into themes, and narrative descriptions will be written for each theme. The Covidence tool was selected as it allows for several researchers to code and analyze the same dataset simultaneously and is specifically intended for use for this type of research. The authors will follow and adapt Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses reporting guidelines for systematic reviews to accurately report the analysis process and the outcomes from the study [ 24 ].

The findings of this study will indicate how far researchers, PhD students, and their supervisors are considering ethics in their studies, including both research ethics and the ethical implications of their work. The importance of our findings is to help understand what deficits exist in the discussion of ethics in peer-reviewed research publications and in US and Swedish PhD dissertations. The findings can guide researchers in determining gaps and shortcomings in current doctoral education. These findings will offer a foundation for adjusting doctoral research education to meet the needs of a society in which research and technological advancement is accelerating at a rate previously unknown. The awareness of ethical issues will allow ethical implications to be addressed more responsively and to start thinking and addressing ethical implications at the beginning of a research project. Some limitations to the interpretations and applicability of the study are (1) the technologies researched will be based on the WHO classification, this might not be all-inclusive, (2) articles and dissertations that are relevant for this study might be missed, (3) discussion and education regarding ethics might occur during the PhD education without being reflected in the dissertations, and (4) studies might discuss ethics without using the term ethics and hence might not be captured in this study.

In an era where technology and research are advancing at speeds unknown to us before, we need to find new and more efficient ways to consider these issues and address them in a timely manner. This study could offer ways of starting an ethical analysis earlier and making it a part of every researcher’s foundation. Not only will addressing ethical issues during the education of future researchers increase their knowledge, but it will also instill a higher level of accountability for how their research could be used in unethical ways.

This study will give insights into and steer what ethical education might prepare future researchers for joining the community of academics by completing a PhD. This study will contribute to the goal of teaching and embedding ethical thinking and moral discernment as part of PhD education to meet the needs of a world that is changing at an accelerating pace.

Abbreviations

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

Profiles of doctoral students’ experience of ethics in supervision: an inter-country comparison

- Open access

- Published: 24 August 2022

- Volume 86 , pages 617–636, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Erika Löfström ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0838-9626 1 ,

- Jouni Peltonen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7458-6532 2 ,

- Liezel Frick ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4797-3323 3 ,

- Katrin Niglas ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0867-9594 4 &

- Kirsi Pyhältö ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8766-0559 1 , 3

2596 Accesses

Explore all metrics

This article has been updated

The purpose of this study was to examine variation in doctoral students’ experiences of ethics in doctoral supervision and how these experiences are related to research engagement, burnout, satisfaction, and intending to discontinue PhD studies. Data were collected from 860 doctoral students in Finland, Estonia, and South Africa. Four distinct profiles of ethics experience in doctoral supervision were identified, namely students puzzled by the supervision relationship, strugglers in the ethical landscape, seekers of ethical allies, and students with ethically trouble-free experiences. The results show that the profiles were related to research engagement, satisfaction with supervision and studies, and burnout. Not experiencing any major ethical problems in supervision was associated with experiencing higher engagement and satisfaction with supervision and doctoral studies and low levels of exhaustion and cynicism. Similar profiles were identified across the countries, yet with different emphases. Both Estonian and South African PhD students were overrepresented in the profile of students with ethically trouble-free experiences, while the Finnish students were underrepresented in this profile. The Finnish PhD students were overrepresented among the seekers of ethical allies. Profiles provide information that can alert supervisors and administrators about the extent of the risk of burnout or discontinuing of PhD studies based on students’ negative experiences of the ethics in supervision.

Similar content being viewed by others

Clinical supervision for clinical psychology students in Uganda: an initial qualitative exploration

Establishing a Holistic Approach for Postgraduate Supervision

How do ethics translate identifying ethical challenges in transnational supervision settings.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Supervision calls for pedagogical considerations of ethics as practiced in the student-supervisor relationship (Halse & Bansel, 2012 ). We have previously shown that Finnish PhD students’ experiences of ethics in supervision predict research engagement, satisfaction with doctoral studies and supervision, burnout, and intentions to discontinue studies (Löfström & Pyhältö, 2020 ). This indicates that sustainable experiences of ethics in the supervision relationship may not only provide a buffer against attrition (Cloete et al., 2015 ) and mental health problems documented in the literature on PhD students (Levecque et al., 2017 ; Reevy & Deason, 2014 ) but could provide a resource allowing doctoral students to flourish (Shin & Jung, 2014 ; Vekkaila et al., 2018 ) . In turn, negative experiences related to ethics in supervision may increase the risk of burnout and dropping out from doctoral studies (Jacobsson & Gillström, 2006 ). However, not much research is available on how doctoral students differ in their experiences of ethics in supervision and how these differences contribute to their research engagement, satisfaction, burnout, and intentions of discontinuing PhD studies. Even less is known about the variation in such experiences across different sociocultural contexts of doctoral education. This study provides insight into how doctoral students differ in their experiences of ethics in supervision and how these differences contribute to their research engagement, satisfaction, burnout, and discontinuing PhD studies and identifies variation in three distinct sociocultural contexts.

Theoretical underpinnings

- Ethics in supervision

Ethics in supervision consist of components of normative principles about acceptable and nonacceptable behavior (ethics) and values that are essential in everyday practices, such as honesty and transparency (integrity) (Jordan, 2013 ). Here, we use the term ethics in supervision to encompass both dimensions in doctoral supervision. Supervision includes both expectations regarding moral positions and acting on those positions. Questions of ethics and integrity are simultaneously present in expectations regarding how research ought to be carried out and how the relationship between a supervisor and a doctoral candidate is construed. We operationalized ethics in supervision through a set of principles familiar from codes of conduct for researchers, such as the Singapore Statement (World Conferences on Research Integrity, 2010 ), and the European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity (ALLEA, 2017 ), and research ethics guidelines, such as the Belmont Report (National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical & Behavioral Research, 1979 ) and the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association WMA, 2013 ), to name a few. These principles include respect for autonomy , beneficence , non-maleficence , justice , and fidelity .

Respect for autonomy is a fundamental ethical principle and refers to the respect for individuals’ right to make decisions concerning themselves (Kitchener, 1985 , 2000 ). In doctoral supervision, this refers to providing sufficient space for the doctoral student to make choices regarding his or her research (Löfström & Pyhältö, 2014 ). The autonomy experienced by doctoral students is shown to be a substantial source of engagement (Vekkaila et al., 2013 ). This does not mean that supervisors should not guide doctoral students in finding proper directions and helping them to make informed choices in the research process. If doctoral students’ freedom of choice or space to explore their own ideas are severely limited, or they feel that different options cannot be raised for discussion, it can infringe on their development in becoming independent researchers (Lee, 2008 ). There is evidence that students’ ethical views develop when supervisors show respect for the students’ own decisions regarding their research (Gray & Jordan, 2012 ). Furthermore, the lack of support that is experienced in the transition into an autonomous and independent researcher may expedite doctoral students’ decisions to discontinue PhD studies (Leijen et al., 2016 ).

Beneficence refers to an intention to do good for others. In supervisory relationships, this entails supporting the doctoral student in developing increased competence and independence and ultimately gaining a doctoral degree. Failure to provide benefits to the doctoral student can be a consequence of insufficient content, pedagogical, and supervisory competence including confusion about role expectations (Jairam & Kahl, 2012 ; Parker-Jenkins, 2018 ).

The principle of non-maleficence is compromised when the doctoral student or his or her rights are harmed in one way or another. In supervisory practices, this may take place as misappropriation or exploitation of a doctoral student’s work or through psychologically confounded relationships, involving a parent/child-like relations or an intimate relationship between a supervisor and a supervisee (Goodyear et al., 1992 ; Löfström & Pyhältö, 2014 ; Parker-Jenkins, 2018 ).

Supervisors use a range of strategies to level out the issues of power asymmetry in their pursuit of supporting doctoral students’ well-being and development (Elliot & Kobayashi, 2018 ). However, asymmetrical power relationships can cause breaches of the principle of justice (Kitchener, 1985 ). Doctoral students may find it difficult to assert themselves in situations in which seniority and expectations of gratitude influence ownership, authorship, or workload (Löfström & Pyhältö, 2014 ; Yarwood-Ross & Haigh, 2014 ).

The principle of fidelity is a vital basis for sustaining any relationship. It includes keeping promises and treating others with respect (Kitchener, 1985 ; 2000 ). In supervision, breaches of fidelity involve failure to keep a supervision promise. The reasons for discontinued supervision may be fully comprehensible, such as a supervisor retiring, moving away, taking parental leave, or falling ill (Löfström & Pyhältö, 2014 ; Wisker & Robinson, 2013 ; Yarwood-Ross & Haigh, 2014 ), but sometimes less so, that is, outright neglect (Johnson et al., 2000 ). In either case, the doctoral student may experience abandonment. Supervisor unavailability is one of the most disruptive aspects for progression in the doctoral journey (McAlpine, 2012 ). Insufficient supervision increases the risk of discontinuing doctoral studies (Pyhältö et al., 2012 ).

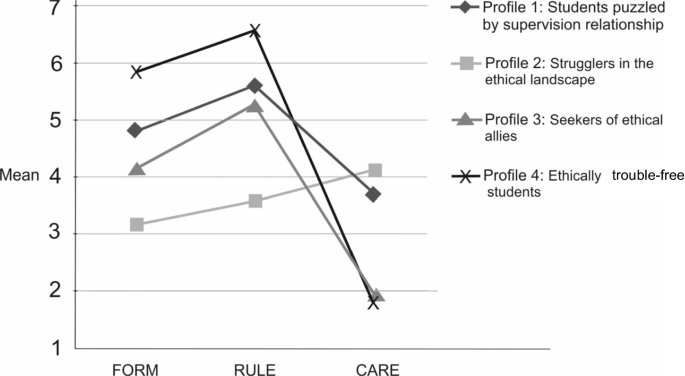

These five ethical principles converge on three thematic dimensions: first, the dimension ethical aspects in the research community, including social structures and programmatic aspects (FORM) , encompasses the principles of autonomy, beneficence, and fidelity. Second, the dimension fairness and adherence to common formal and informal rules as a means of ensuring equal treatment of doctoral students (RULE) encompasses justice, non-maleficence, and fidelity. Third, the dimension respect in personal relations (CARE) encompasses autonomy and beneficence. Positive experiences of these dimensions contribute to engagement and satisfaction while negative experiences contribute to burnout and intentions to drop out (Löfström & Pyhältö, 2020 ).

Combining these dimensions of ethics in supervision raises a question about the interrelation between the constructs (for approaches related to burnout and engagement, see Shirom, 2011 ; Larsen & McGraw, 2011 ; Shraga & Shirom, 2009 ). If these dimensions are independent, one may score high on one and low on the other dimensions. For instance, a PhD student might simultaneously experience high levels of fairness and equal treatment of doctoral students (RULE) and lack of respect in personal relations (CARE). Alternatively, they may be dependent, and a high score on one dimension would correlate with a high score on the other. Applying a person-centered approach to PhD students’ experiences of ethics in supervision allows us to explore the question in more detail.

Study engagement and study burnout

Study engagement has been suggested as being a hallmark of optimal doctoral experience, characterized by sense of vigor , dedication , and absorption (Vekkaila et al., 2018 ; see seminal work on work engagement by Bakker & Demerouti, 2008 ; González-Romá et al., 2006 ; Schaufeli et al., 2002 ). Such doctoral experiences encompass immersion in research, a feeling of time passing quickly, strong psychological involvement in research combined with a sense of significance, enthusiasm, inspiration, pride, positive challenge, and high levels of energy resulting in positive outcomes in post-PhD researcher careers (Shin & Jung, 2014 ; Vekkaila et al., 2018 ) . Doctoral students who receive sufficient supervisory and research community support are more likely to experience higher levels of engagement than their less fortunate peers (Pyhältö et al., 2016 ).

Problems in the supervisory relationship and lack of faculty support appear to be related to increased risk of burnout (Peluso et al., 2011 ). PhD burnout resulting from extensive and prolonged stress has two main symptoms, namely exhaustion characterized by a lack of emotional energy and feeling drained and tired of doctoral studies and cynicism comprising feeling that one’s research has lost its meaning and distancing oneself from the work and members of the research community (Maslach & Leiter, 2008 ). Research environment attributes, such as sufficient supervisory and research community support, sense of belonging, and good work-environment fit, have been found to be associated with reduced burnout risk and increased levels of engagement among doctoral students (Hunter & Devine, 2016 ). Burnout entails negative consequences including reduced research productivity, reduced engagement, reduced interest in research, study prolongation, and increased risk of discontinuing doctoral studies (Ali & Kohun, 2007 ; Pyhältö et al., 2018 ; Rigg et al., 2013 ).

Little is known about individual differences in doctoral students’ experiences of the ethics in supervision, and how these differences are related to supervision arrangements and student well-being or a lack thereof. The theoretical underpinnings and results from earlier studies in Finland (e.g., Löfström & Pyhältö, 2020 ) inspired us to hypothesize that the underlying structures concerning the experiences of ethics in supervision may be the same across different cultural contexts as similar problems have been described elsewhere (see Muthanna & Alduais, 2021 ). Therefore, we set out to identify profiles of doctoral students’ experiences of ethics in supervision and their association with engagement, burnout, and intentions to drop out in the historically diverse but culturally and regionally relatively similar contexts of Finland and Estonia, in comparison to the culturally and regionally rather different context of South Africa.

These countries have in common high levels of attrition and distress and exhaustion in addition to prolonged studies, insufficient supervision, and poor integration of doctoral students into the research community (ASSAf, 2010 ; Herman, 2011 ; Leijen et al., 2016 ; Stubb et al., 2011 ; Vassil & Solvak, 2012 ). There is evidence that 35–45% of Finnish doctoral students have considered discontinue studies (Pyhältö et al., 2016 ). In South Africa, the attrition rate amongst doctoral students is 22% nationally in the first year with less than half of candidates graduating within 7 years (Cloete et al., 2015 ). In Estonia, the reported attrition in the phase prior to planning our study was 34% (Vassil & Solvak, 2012 ). Outcomes such as exhaustion and attrition have been shown to be related to negative experiences of ethics in supervision (Löfström & Pyhältö, 2020 ). These shared problems in doctoral education and differences in the settings make it relevant to study the chosen countries from the perspective of ethics in supervision and compare the results in order to understand universal and context-specific aspects of doctoral students’ experiences of the ethics in supervision. Following the above, we posed the research questions:

How do Finnish, South African, and Estonian PhD students experience the ethics in supervision, engagement, burnout, and satisfaction with supervision and doctoral studies?

What kind of profiles do experiences of the ethics in supervision, engagement, burnout, and satisfaction with supervision and doctoral studies constitute among Finnish, South African, and Estonian PhD students?

Is there a relationship between the experiences of ethics in supervision profiles and supervisory arrangements (frequency of supervision, number of supervisors, and individual or group supervision)?

As profiles of doctoral students’ experiences of the ethics in supervision have not been identified before using a broad set of key variables of importance in the doctoral experience, we were interested in the profiles as such in the comparative context set out for our study.

In Finland, doctoral studies are research-intensive rather than course-centered, and research generally begins immediately (Pyhältö et al., 2012 ). In Estonia, the recent reform of doctoral studies introduced a substantial amount of course work to the curriculum and regardless of the emphasis put on research, the first year of a doctoral program is often devoted to course work, leaving less time for research activities. In South Africa, doctoral studies are research oriented. Although professional doctorates are now included in the South African Higher Education Qualifications Sub-framework (Council on Higher Education, 2014 ), doctoral programs continue predominantly to be by research only, with no credit-bearing coursework.

Tuition fees

In Finland, doctoral education is publicly funded, and there are no tuition fees for students. However, there is no automatic funding for studying at the doctoral level. Students apply for competitive funding from a number of foundations that support research or find employment at the university on various projects, or outside the university (Pyhältö et al., 2011 ). In addition, in Estonia, doctoral education is publicly funded (Lepp et al., 2016 ). Since 2012, every student who is granted a doctoral study place receives a grant for 4 years. Recently, several Estonian universities have introduced a policy by which they grant doctoral students an income comparable to the average salary, but the Estonian data were collected in 2016, before this policy came into existence, and the grant was substantially smaller. Consequently, there has been a tradition of finding additional employment in or outside the university. In South Africa, the doctoral education system is funded by a combination of government subsidies and student fees (Cloete et al., 2015 ). Many students are already employed when enrolling for a doctorate or are soon usurped into academic positions. However, in humanities, arts, and social sciences, many students receive little or no financial support, while funded full time doctoral study is more common in STEM.

Supervision arrangements

In Finland, doctoral students are expected to have two named supervisors. One of these is generally a full professor. It is common that doctoral students take part in research seminars organized by a supervisor (Pyhältö et al., 2012 ). In Estonia, doctoral students must have at least one named supervisor at the professorial level, but if the supervisor is less experienced, the doctoral program committee commonly assigns a senior supervisor to support the process. A similar practice of teaming up inexperienced supervisors with more experienced ones is in place in South Africa, although a supervisor does not need to be at a professorial level. Given the current lack of suitably qualified supervisory capacity in a variety of fields, inexperienced supervisors are often allocated to students, and single student-supervisor dyadic arrangements are still common (Cloete et al., 2015 ).

Types of doctoral dissertation

In both Finland and Estonia, a doctoral dissertation can be written either as a monograph or as an article compilation, with the latter being more prevalent in many fields. The articles are usually co-authored with the supervisors and sometimes with other senior researchers (Lepp et al., 2016 ; Pyhältö et al., 2012 ). In South Africa, doctoral dissertations follow a variety of formats, including both monographs and publication-based theses, or various permutations of these formats (Odendaal & Frick, 2017 ).

Participants

The data were collected at four universities in 2016 and 2017 as independent surveys. The universities included two in Finland, one in Estonia and one in South Africa. All four have an international profile and play important national and regional roles. All are research universities, but they are at different stages of building up their research profiles. The response rate in each country was 25–26%. The data set consisted of 860 doctoral students with a mean age of 37.59 (Table 1 ). The largest subset, namely the Finnish data, are representative of age and disciplines, with women slightly overrepresented among the respondents.