How to Write a Good English Literature Essay

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

How do you write a good English Literature essay? Although to an extent this depends on the particular subject you’re writing about, and on the nature of the question your essay is attempting to answer, there are a few general guidelines for how to write a convincing essay – just as there are a few guidelines for writing well in any field.

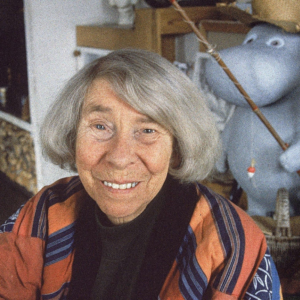

We at Interesting Literature call them ‘guidelines’ because we hesitate to use the word ‘rules’, which seems too programmatic. And as the writing habits of successful authors demonstrate, there is no one way to become a good writer – of essays, novels, poems, or whatever it is you’re setting out to write. The French writer Colette liked to begin her writing day by picking the fleas off her cat.

Edith Sitwell, by all accounts, liked to lie in an open coffin before she began her day’s writing. Friedrich von Schiller kept rotten apples in his desk, claiming he needed the scent of their decay to help him write. (For most student essay-writers, such an aroma is probably allowed to arise in the writing-room more organically, over time.)

We will address our suggestions for successful essay-writing to the average student of English Literature, whether at university or school level. There are many ways to approach the task of essay-writing, and these are just a few pointers for how to write a better English essay – and some of these pointers may also work for other disciplines and subjects, too.

Of course, these guidelines are designed to be of interest to the non-essay-writer too – people who have an interest in the craft of writing in general. If this describes you, we hope you enjoy the list as well. Remember, though, everyone can find writing difficult: as Thomas Mann memorably put it, ‘A writer is someone for whom writing is more difficult than it is for other people.’ Nora Ephron was briefer: ‘I think the hardest thing about writing is writing.’ So, the guidelines for successful essay-writing:

1. Planning is important, but don’t spend too long perfecting a structure that might end up changing.

This may seem like odd advice to kick off with, but the truth is that different approaches work for different students and essayists. You need to find out which method works best for you.

It’s not a bad idea, regardless of whether you’re a big planner or not, to sketch out perhaps a few points on a sheet of paper before you start, but don’t be surprised if you end up moving away from it slightly – or considerably – when you start to write.

Often the most extensively planned essays are the most mechanistic and dull in execution, precisely because the writer has drawn up a plan and refused to deviate from it. What is a more valuable skill is to be able to sense when your argument may be starting to go off-topic, or your point is getting out of hand, as you write . (For help on this, see point 5 below.)

We might even say that when it comes to knowing how to write a good English Literature essay, practising is more important than planning.

2. Make room for close analysis of the text, or texts.

Whilst it’s true that some first-class or A-grade essays will be impressive without containing any close reading as such, most of the highest-scoring and most sophisticated essays tend to zoom in on the text and examine its language and imagery closely in the course of the argument. (Close reading of literary texts arises from theology and the analysis of holy scripture, but really became a ‘thing’ in literary criticism in the early twentieth century, when T. S. Eliot, F. R. Leavis, William Empson, and other influential essayists started to subject the poem or novel to close scrutiny.)

Close reading has two distinct advantages: it increases the specificity of your argument (so you can’t be so easily accused of generalising a point), and it improves your chances of pointing up something about the text which none of the other essays your marker is reading will have said. For instance, take In Memoriam (1850), which is a long Victorian poem by the poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson about his grief following the death of his close friend, Arthur Hallam, in the early 1830s.

When answering a question about the representation of religious faith in Tennyson’s poem In Memoriam (1850), how might you write a particularly brilliant essay about this theme? Anyone can make a general point about the poet’s crisis of faith; but to look closely at the language used gives you the chance to show how the poet portrays this.

For instance, consider this stanza, which conveys the poet’s doubt:

A solid and perfectly competent essay might cite this stanza in support of the claim that Tennyson is finding it increasingly difficult to have faith in God (following the untimely and senseless death of his friend, Arthur Hallam). But there are several ways of then doing something more with it. For instance, you might get close to the poem’s imagery, and show how Tennyson conveys this idea, through the image of the ‘altar-stairs’ associated with religious worship and the idea of the stairs leading ‘thro’ darkness’ towards God.

In other words, Tennyson sees faith as a matter of groping through the darkness, trusting in God without having evidence that he is there. If you like, it’s a matter of ‘blind faith’. That would be a good reading. Now, here’s how to make a good English essay on this subject even better: one might look at how the word ‘falter’ – which encapsulates Tennyson’s stumbling faith – disperses into ‘falling’ and ‘altar’ in the succeeding lines. The word ‘falter’, we might say, itself falters or falls apart.

That is doing more than just interpreting the words: it’s being a highly careful reader of the poetry and showing how attentive to the language of the poetry you can be – all the while answering the question, about how the poem portrays the idea of faith. So, read and then reread the text you’re writing about – and be sensitive to such nuances of language and style.

The best way to become attuned to such nuances is revealed in point 5. We might summarise this point as follows: when it comes to knowing how to write a persuasive English Literature essay, it’s one thing to have a broad and overarching argument, but don’t be afraid to use the microscope as well as the telescope.

3. Provide several pieces of evidence where possible.

Many essays have a point to make and make it, tacking on a single piece of evidence from the text (or from beyond the text, e.g. a critical, historical, or biographical source) in the hope that this will be enough to make the point convincing.

‘State, quote, explain’ is the Holy Trinity of the Paragraph for many. What’s wrong with it? For one thing, this approach is too formulaic and basic for many arguments. Is one quotation enough to support a point? It’s often a matter of degree, and although one piece of evidence is better than none, two or three pieces will be even more persuasive.

After all, in a court of law a single eyewitness account won’t be enough to convict the accused of the crime, and even a confession from the accused would carry more weight if it comes supported by other, objective evidence (e.g. DNA, fingerprints, and so on).

Let’s go back to the example about Tennyson’s faith in his poem In Memoriam mentioned above. Perhaps you don’t find the end of the poem convincing – when the poet claims to have rediscovered his Christian faith and to have overcome his grief at the loss of his friend.

You can find examples from the end of the poem to suggest your reading of the poet’s insincerity may have validity, but looking at sources beyond the poem – e.g. a good edition of the text, which will contain biographical and critical information – may help you to find a clinching piece of evidence to support your reading.

And, sure enough, Tennyson is reported to have said of In Memoriam : ‘It’s too hopeful, this poem, more than I am myself.’ And there we have it: much more convincing than simply positing your reading of the poem with a few ambiguous quotations from the poem itself.

Of course, this rule also works in reverse: if you want to argue, for instance, that T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land is overwhelmingly inspired by the poet’s unhappy marriage to his first wife, then using a decent biographical source makes sense – but if you didn’t show evidence for this idea from the poem itself (see point 2), all you’ve got is a vague, general link between the poet’s life and his work.

Show how the poet’s marriage is reflected in the work, e.g. through men and women’s relationships throughout the poem being shown as empty, soulless, and unhappy. In other words, when setting out to write a good English essay about any text, don’t be afraid to pile on the evidence – though be sensible, a handful of quotations or examples should be more than enough to make your point convincing.

4. Avoid tentative or speculative phrasing.

Many essays tend to suffer from the above problem of a lack of evidence, so the point fails to convince. This has a knock-on effect: often the student making the point doesn’t sound especially convinced by it either. This leaks out in the telling use of, and reliance on, certain uncertain phrases: ‘Tennyson might have’ or ‘perhaps Harper Lee wrote this to portray’ or ‘it can be argued that’.

An English university professor used to write in the margins of an essay which used this last phrase, ‘What can’t be argued?’

This is a fair criticism: anything can be argued (badly), but it depends on what evidence you can bring to bear on it (point 3) as to whether it will be a persuasive argument. (Arguing that the plays of Shakespeare were written by a Martian who came down to Earth and ingratiated himself with the world of Elizabethan theatre is a theory that can be argued, though few would take it seriously. We wish we could say ‘none’, but that’s a story for another day.)

Many essay-writers, because they’re aware that texts are often open-ended and invite multiple interpretations (as almost all great works of literature invariably do), think that writing ‘it can be argued’ acknowledges the text’s rich layering of meaning and is therefore valid.

Whilst this is certainly a fact – texts are open-ended and can be read in wildly different ways – the phrase ‘it can be argued’ is best used sparingly if at all. It should be taken as true that your interpretation is, at bottom, probably unprovable. What would it mean to ‘prove’ a reading as correct, anyway? Because you found evidence that the author intended the same thing as you’ve argued of their text? Tennyson wrote in a letter, ‘I wrote In Memoriam because…’?

But the author might have lied about it (e.g. in an attempt to dissuade people from looking too much into their private life), or they might have changed their mind (to go back to the example of The Waste Land : T. S. Eliot championed the idea of poetic impersonality in an essay of 1919, but years later he described The Waste Land as ‘only the relief of a personal and wholly insignificant grouse against life’ – hardly impersonal, then).

Texts – and their writers – can often be contradictory, or cagey about their meaning. But we as critics have to act responsibly when writing about literary texts in any good English essay or exam answer. We need to argue honestly, and sincerely – and not use what Wikipedia calls ‘weasel words’ or hedging expressions.

So, if nothing is utterly provable, all that remains is to make the strongest possible case you can with the evidence available. You do this, not only through marshalling the evidence in an effective way, but by writing in a confident voice when making your case. Fundamentally, ‘There is evidence to suggest that’ says more or less the same thing as ‘It can be argued’, but it foregrounds the evidence rather than the argument, so is preferable as a phrase.

This point might be summarised by saying: the best way to write a good English Literature essay is to be honest about the reading you’re putting forward, so you can be confident in your interpretation and use clear, bold language. (‘Bold’ is good, but don’t get too cocky, of course…)

5. Read the work of other critics.

This might be viewed as the Holy Grail of good essay-writing tips, since it is perhaps the single most effective way to improve your own writing. Even if you’re writing an essay as part of school coursework rather than a university degree, and don’t need to research other critics for your essay, it’s worth finding a good writer of literary criticism and reading their work. Why is this worth doing?

Published criticism has at least one thing in its favour, at least if it’s published by an academic press or has appeared in an academic journal, and that is that it’s most probably been peer-reviewed, meaning that other academics have read it, closely studied its argument, checked it for errors or inaccuracies, and helped to ensure that it is expressed in a fluent, clear, and effective way.

If you’re serious about finding out how to write a better English essay, then you need to study how successful writers in the genre do it. And essay-writing is a genre, the same as novel-writing or poetry. But why will reading criticism help you? Because the critics you read can show you how to do all of the above: how to present a close reading of a poem, how to advance an argument that is not speculative or tentative yet not over-confident, how to use evidence from the text to make your argument more persuasive.

And, the more you read of other critics – a page a night, say, over a few months – the better you’ll get. It’s like textual osmosis: a little bit of their style will rub off on you, and every writer learns by the examples of other writers.

As T. S. Eliot himself said, ‘The poem which is absolutely original is absolutely bad.’ Don’t get precious about your own distinctive writing style and become afraid you’ll lose it. You can’t gain a truly original style before you’ve looked at other people’s and worked out what you like and what you can ‘steal’ for your own ends.

We say ‘steal’, but this is not the same as saying that plagiarism is okay, of course. But consider this example. You read an accessible book on Shakespeare’s language and the author makes a point about rhymes in Shakespeare. When you’re working on your essay on the poetry of Christina Rossetti, you notice a similar use of rhyme, and remember the point made by the Shakespeare critic.

This is not plagiarising a point but applying it independently to another writer. It shows independent interpretive skills and an ability to understand and apply what you have read. This is another of the advantages of reading critics, so this would be our final piece of advice for learning how to write a good English essay: find a critic whose style you like, and study their craft.

If you’re looking for suggestions, we can recommend a few favourites: Christopher Ricks, whose The Force of Poetry is a tour de force; Jonathan Bate, whose The Genius of Shakespeare , although written for a general rather than academic audience, is written by a leading Shakespeare scholar and academic; and Helen Gardner, whose The Art of T. S. Eliot , whilst dated (it came out in 1949), is a wonderfully lucid and articulate analysis of Eliot’s poetry.

James Wood’s How Fiction Works is also a fine example of lucid prose and how to close-read literary texts. Doubtless readers of Interesting Literature will have their own favourites to suggest in the comments, so do check those out, as these are just three personal favourites. What’s your favourite work of literary scholarship/criticism? Suggestions please.

Much of all this may strike you as common sense, but even the most commonsensical advice can go out of your mind when you have a piece of coursework to write, or an exam to revise for. We hope these suggestions help to remind you of some of the key tenets of good essay-writing practice – though remember, these aren’t so much commandments as recommendations. No one can ‘tell’ you how to write a good English Literature essay as such.

But it can be learned. And remember, be interesting – find the things in the poems or plays or novels which really ignite your enthusiasm. As John Mortimer said, ‘The only rule I have found to have any validity in writing is not to bore yourself.’

Finally, good luck – and happy writing!

And if you enjoyed these tips for how to write a persuasive English essay, check out our advice for how to remember things for exams and our tips for becoming a better close reader of poetry .

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

Type your email…

30 thoughts on “How to Write a Good English Literature Essay”

You must have taken AP Literature. I’m always saying these same points to my students.

I also think a crucial part of excellent essay writing that too many students do not realize is that not every point or interpretation needs to be addressed. When offered the chance to write your interpretation of a work of literature, it is important to note that there of course are many but your essay should choose one and focus evidence on this one view rather than attempting to include all views and evidence to back up each view.

Reblogged this on SocioTech'nowledge .

Not a bad effort…not at all! (Did you intend “subject” instead of “object” in numbered paragraph two, line seven?”

Oops! I did indeed – many thanks for spotting. Duly corrected ;)

That’s what comes of writing about philosophy and the subject/object for another post at the same time!

Reblogged this on Scribing English .

- Pingback: Recommended Resource: Interesting Literature.com & how to write an essay | Write Out Loud

Great post on essay writing! I’ve shared a post about this and about the blog site in general which you can look at here: http://writeoutloudblog.com/2015/01/13/recommended-resource-interesting-literature-com-how-to-write-an-essay/

All of these are very good points – especially I like 2 and 5. I’d like to read the essay on the Martian who wrote Shakespeare’s plays).

Reblogged this on Uniqely Mustered and commented: Dedicate this to all upcoming writers and lovers of Writing!

I shall take this as my New Year boost in Writing Essays. Please try to visit often for corrections,advise and criticisms.

Reblogged this on Blue Banana Bread .

Reblogged this on worldsinthenet .

All very good points, but numbers 2 and 4 are especially interesting.

- Pingback: Weekly Digest | Alpha Female, Mainstream Cat

Reblogged this on rainniewu .

Reblogged this on pixcdrinks .

- Pingback: How to Write a Good English Essay? Interesting Literature | EngLL.Com

Great post. Interesting infographic how to write an argumentative essay http://www.essay-profy.com/blog/how-to-write-an-essay-writing-an-argumentative-essay/

Reblogged this on DISTINCT CHARACTER and commented: Good Tips

Reblogged this on quirkywritingcorner and commented: This could be applied to novel or short story writing as well.

Reblogged this on rosetech67 and commented: Useful, albeit maybe a bit late for me :-)

- Pingback: How to Write a Good English Essay | georg28ang

such a nice pieace of content you shared in this write up about “How to Write a Good English Essay” going to share on another useful resource that is

- Pingback: Mark Twain’s Rules for Good Writing | Interesting Literature

- Pingback: How to Remember Things for Exams | Interesting Literature

- Pingback: Michael Moorcock: How to Write a Novel in 3 Days | Interesting Literature

- Pingback: Shakespeare and the Essay | Interesting Literature

A well rounded summary on all steps to keep in mind while starting on writing. There are many new avenues available though. Benefit from the writing options of the 21st century from here, i loved it! http://authenticwritingservices.com

- Pingback: Mark Twain’s Rules for Good Writing | Peacejusticelove's Blog

Comments are closed.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

You are using an outdated browser. This site may not look the way it was intended for you. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience and security.

London School of Journalism

- Tel: +44 (0) 20 7432 8140

- [email protected]

- Student log in

Search courses

English literature essays, an english literature essay archive, written by our students, with subjects ranging from shakespeare to artistotle, and from dickens to hemingway, essay subjects in alphabetical order:.

- Aristotle: Poetics

Margaret Atwood

Margaret atwood 'gertrude talks back'.

- Matthew Arnold

John Bunyan: The Pilgrim's Progress and Geoffrey Chaucer: The Canterbury Tales

- Jonathan Bayliss

- Lewis Carroll, Samuel Beckett

- Saul Bellow and Ken Kesey

- Castiglione: The Courtier

- Joseph Conrad: Heart of Darkness

- Kate Chopin: The Awakening

- T S Eliot, Albert Camus

- Charles Dickens

- John Donne: Love poetry

- John Dryden: Translation of Ovid

- T S Eliot: Four Quartets

- Henry Fielding

- William Faulkner: Sartoris

- Graham Greene: Brighton Rock

- Ibsen, Lawrence, Galsworthy

- Jonathan Swift and John Gay

- Oliver Goldsmith

- Ernest Hemingway

- Nathaniel Hawthorne: The Scarlet Letter

Thomas Hardy: Tess of the d'Urbervilles

- Carl Gustav Jung

James Joyce: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

- Jon Jost: American independent film-maker

- Jamaica Kincaid, Merle Hodge, George Lamming

- Rudyard Kipling: Kim

- D. H. Lawrence: Women in Love

Henry Lawson: 'Eureka!'

- Ian McEwan: The Cement Garden

- Jennifer Maiden: The Winter Baby

- Machiavelli: The Prince

- Toni Morrison: Beloved and Jazz

R K Narayan

- R K Narayan: The English Teacher

- R K Narayan: The Guide

- Alexander Pope: The Rape of the Lock

- Brian Patten

- Harold Pinter

- Sylvia Plath and Alice Walker

Jean Rhys: Wide Sargasso Sea. Charlotte Bronte: Jane Eyre

- Edmund Spenser: The Faerie Queene

- Shakespeare: Antony and Cleopatra

- Shakespeare: Coriolanus

- Shakespeare: Hamlet

- Shakespeare: Measure for Measure

Shakespeare: Shakespeare's Women

Shakespeare: the winter's tale and the tempest.

- Shakespeare: Twelfth Night

- Sir Philip Sidney: Astrophil and Stella

- Tom Stoppard

William Styron: Sophie's Choice

- William Wordsworth

Miscellaneous

- Alice, Harry Potter and the computer game

Indian women's writing

- New York! New York!

- Photography and the New Native American Aesthetic

- Renaissance poetry

- Renaissance tragedy and investigator heroes

- Romanticism

- Studying English Literature

- The Age of Reason

- The author, the text, and the reader

- The Spy in the Computer

- What is literary writing?

- Margaret Atwood: Bodily Harm and The Handmaid's Tale

- Margaret Atwood 'Gertrude Talks Back'

- John Bunyan: The Pilgrim's Progress and Geoffrey Chaucer: The Canterbury Tales

- Thomas Hardy: Tess of the d'Urbervilles

- James Joyce: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: Will McManus

- James Joyce: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: Ian Mackean

- James Joyce: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: Ben Foley

- Henry Lawson: 'Eureka!'

- R K Narayan's vision of life

- Jean Rhys: Wide Sargasso Sea. Charlotte Bronte: Jane Eyre: Doubles

- Jean Rhys: Wide Sargasso Sea. Charlotte Bronte: Jane Eyre: Symbolism

- Shakespeare: Shakespeare's Women

- Shakespeare: The Winter's Tale and The Tempest

- William Styron: Sophie's Choice

- William Wordsworth and Lucy

- Indian women's writing

Suggestions

- Don Quixote

- Pride and Prejudice

- The Crucible

- The Odyssey

- The Outsiders

Please wait while we process your payment

Reset Password

Your password reset email should arrive shortly..

If you don't see it, please check your spam folder. Sometimes it can end up there.

Something went wrong

Log in or create account.

- Be between 8-15 characters.

- Contain at least one capital letter.

- Contain at least one number.

- Be different from your email address.

By signing up you agree to our terms and privacy policy .

Don’t have an account? Subscribe now

Create Your Account

Sign up for your FREE 7-day trial

- Ad-free experience

- Note-taking

- Flashcards & Quizzes

- AP® English Test Prep

- Plus much more

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Already have an account? Log in

Choose Your Plan

Group Discount

$4.99 /month + tax

$24.99 /year + tax

Save over 50% with a SparkNotes PLUS Annual Plan!

Purchasing SparkNotes PLUS for a group?

Get Annual Plans at a discount when you buy 2 or more!

$24.99 $18.74 / subscription + tax

Subtotal $37.48 + tax

Save 25% on 2-49 accounts

Save 30% on 50-99 accounts

Want 100 or more? Contact us for a customized plan.

Payment Details

Payment Summary

SparkNotes Plus

Change

You'll be billed after your free trial ends.

7-Day Free Trial

Not Applicable

Renews May 10, 2024 May 3, 2024

Discounts (applied to next billing)

SNPLUSROCKS20 | 20% Discount

This is not a valid promo code.

Discount Code (one code per order)

SparkNotes PLUS Annual Plan - Group Discount

SparkNotes Plus subscription is $4.99/month or $24.99/year as selected above. The free trial period is the first 7 days of your subscription. TO CANCEL YOUR SUBSCRIPTION AND AVOID BEING CHARGED, YOU MUST CANCEL BEFORE THE END OF THE FREE TRIAL PERIOD. You may cancel your subscription on your Subscription and Billing page or contact Customer Support at [email protected] . Your subscription will continue automatically once the free trial period is over. Free trial is available to new customers only.

For the next 7 days, you'll have access to awesome PLUS stuff like AP English test prep, No Fear Shakespeare translations and audio, a note-taking tool, personalized dashboard, & much more!

You’ve successfully purchased a group discount. Your group members can use the joining link below to redeem their group membership. You'll also receive an email with the link.

Members will be prompted to log in or create an account to redeem their group membership.

Thanks for creating a SparkNotes account! Continue to start your free trial.

We're sorry, we could not create your account. SparkNotes PLUS is not available in your country. See what countries we’re in.

There was an error creating your account. Please check your payment details and try again.

Your PLUS subscription has expired

- We’d love to have you back! Renew your subscription to regain access to all of our exclusive, ad-free study tools.

- Renew your subscription to regain access to all of our exclusive, ad-free study tools.

- Go ad-free AND get instant access to grade-boosting study tools!

- Start the school year strong with SparkNotes PLUS!

- Start the school year strong with PLUS!

How to Write Literary Analysis

Introduction.

When you read for pleasure, your only goal is enjoyment. You might find yourself reading to get caught up in an exciting story, to learn about an interesting time or place, or just to pass time. Maybe you’re looking for inspiration, guidance, or a reflection of your own life. There are as many different, valid ways of reading a book as there are books in the world.

When you read a work of literature in an English class, however, you’re being asked to read in a special way: you’re being asked to perform literary analysis. To analyze something means to break it down into smaller parts and then examine how those parts work, both individually and together. Literary analysis involves examining all the parts of a novel, play, short story, or poem—elements such as character, setting, tone, and imagery—and thinking about how the author uses those elements to create certain effects.

A literary essay isn’t a book review: you’re not being asked whether or not you liked a book or whether you’d recommend it to another reader. A literary essay also isn’t like the kind of book report you wrote when you were younger, where your teacher wanted you to summarize the book’s action. A high school- or college-level literary essay asks, “How does this piece of literature actually work?” “How does it do what it does?” and, “Why might the author have made the choices he or she did?”

The Seven Steps

No one is born knowing how to analyze literature; it’s a skill you learn and a process you can master. As you gain more practice with this kind of thinking and writing, you’ll be able to craft a method that works best for you. But until then, here are seven basic steps to writing a well-constructed literary essay.

- 1. Ask questions

- 2. Collect evidence

- 3. Construct a thesis

- 4. Develop and organize arguments

- 5. Write the introduction

- 6. Write the body paragraphs

- 7. Write the conclusion

1 Ask Questions

When you’re assigned a literary essay in class, your teacher will often provide you with a list of writing prompts. Lucky you! Now all you have to do is choose one. Do yourself a favor and pick a topic that interests you. You’ll have a much better (not to mention easier) time if you start off with something you enjoy thinking about. If you are asked to come up with a topic by yourself, though, you might start to feel a little panicked. Maybe you have too many ideas—or none at all. Don’t worry. Take a deep breath and start by asking yourself these questions:

What struck you?

Did a particular image, line, or scene linger in your mind for a long time? If it fascinated you, chances are you can draw on it to write a fascinating essay.

What confused you?

Maybe you were surprised to see a character act in a certain way, or maybe you didn’t understand why the book ended the way it did. Confusing moments in a work of literature are like a loose thread in a sweater: if you pull on it, you can unravel the entire thing. Ask yourself why the author chose to write about that character or scene the way he or she did and you might tap into some important insights about the work as a whole.

Did you notice any patterns?

Is there a phrase that the main character uses constantly or an image that repeats throughout the book? If you can figure out how that pattern weaves through the work and what the significance of that pattern is, you’ve almost got your entire essay mapped out.

Did you notice any contradictions or ironies?

Great works of literature are complex; great literary essays recognize and explain those complexities. Maybe the title Happy Days totally disagrees with the book’s subject matter (hungry orphans dying in the woods). Maybe the main character acts one way around his family and a completely different way around his friends and associates. If you can find a way to explain a work’s contradictory elements, you’ve got the seeds of a great essay.

At this point, you don’t need to know exactly what you’re going to say about your topic; you just need a place to begin your exploration. You can help direct your reading and brainstorming by formulating your topic as a question, which you’ll then try to answer in your essay. The best questions invite critical debates and discussions, not just a rehashing of the summary. Remember, you’re looking for something you can prove or argue based on evidence you find in the text. Finally, remember to keep the scope of your question in mind: is this a topic you can adequately address within the word or page limit you’ve been given? Conversely, is this a topic big enough to fill the required length?

Good questions

“Are Romeo and Juliet’s parents responsible for the deaths of their children?”

“Why do pigs keep showing up in Lord of the Flies ?”

“Are Dr. Frankenstein and his monster alike? How?”

Bad questions

“What happens to Scout in To Kill a Mockingbird ?”

“What do the other characters in Julius Caesar think about Caesar?”

“How does Hester Prynne in The Scarlet Letter remind me of my sister?”

2 Collect Evidence

Once you know what question you want to answer, it’s time to scour the book for things that will help you answer the question. Don’t worry if you don’t know what you want to say yet—right now you’re just collecting ideas and material and letting it all percolate. Keep track of passages, symbols, images, or scenes that deal with your topic. Eventually, you’ll start making connections between these examples and your thesis will emerge.

Here’s a brief summary of the various parts that compose each and every work of literature. These are the elements that you will analyze in your essay, and which you will offer as evidence to support your arguments. For more on the parts of literary works, see the Glossary of Literary Terms at the end of this section.

Elements of Story

These are the whats of the work—what happens, where it happens, and to whom it happens.

Elements of Style

These are the hows —how the characters speak, how the story is constructed, and how language is used throughout the work.

Structure and organization

Point of view, figurative language, 3 construct a thesis.

When you’ve examined all the evidence you’ve collected and know how you want to answer the question, it’s time to write your thesis statement. A thesis is a claim about a work of literature that needs to be supported by evidence and arguments. The thesis statement is the heart of the literary essay, and the bulk of your paper will be spent trying to prove this claim. A good thesis will be:

“ The Great Gatsby describes New York society in the 1920s” isn’t a thesis—it’s a fact.

Provable through textual evidence.

“ Hamlet is a confusing but ultimately very well-written play” is a weak thesis because it offers the writer’s personal opinion about the book. Yes, it’s arguable, but it’s not a claim that can be proved or supported with examples taken from the play itself.

Surprising.

“Both George and Lenny change a great deal in Of Mice and Men ” is a weak thesis because it’s obvious. A really strong thesis will argue for a reading of the text that is not immediately apparent.

“Dr. Frankenstein’s monster tells us a lot about the human condition” is almost a really great thesis statement, but it’s still too vague. What does the writer mean by “a lot”? How does the monster tell us so much about the human condition?

Good Thesis Statements

Question: In Romeo and Juliet , which is more powerful in shaping the lovers’ story: fate or foolishness?

Thesis: “Though Shakespeare defines Romeo and Juliet as ‘star- crossed lovers’ and images of stars and planets appear throughout the play, a closer examination of that celestial imagery reveals that the stars are merely witnesses to the characters’ foolish activities and not the causes themselves.”

Question: How does the bell jar function as a symbol in Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar ?

Thesis: “A bell jar is a bell-shaped glass that has three basic uses: to hold a specimen for observation, to contain gases, and to maintain a vacuum. The bell jar appears in each of these capacities in The Bell Jar , Plath’s semi-autobiographical novel, and each appearance marks a different stage in Esther’s mental breakdown.”

Question: Would Piggy in The Lord of the Flies make a good island leader if he were given the chance?

Thesis: “Though the intelligent, rational, and innovative Piggy has the mental characteristics of a good leader, he ultimately lacks the social skills necessary to be an effective one. Golding emphasizes this point by giving Piggy a foil in the charismatic Jack, whose magnetic personality allows him to capture and wield power effectively, if not always wisely.”

4 Develop and Organize Arguments

The reasons and examples that support your thesis will form the middle paragraphs of your essay. Since you can’t really write your thesis statement until you know how you’ll structure your argument, you’ll probably end up working on steps 3 and 4 at the same time.

There’s no single method of argumentation that will work in every context. One essay prompt might ask you to compare and contrast two characters, while another asks you to trace an image through a given work of literature. These questions require different kinds of answers and therefore different kinds of arguments. Below, we’ll discuss three common kinds of essay prompts and some strategies for constructing a solid, well-argued case.

Types of Literary Essays

Compare and contrast.

Compare and contrast the characters of Huck and Jim in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn .

Chances are you’ve written this kind of essay before. In an academic literary context, you’ll organize your arguments the same way you would in any other class. You can either go subject by subject or point by point . In the former, you’ll discuss one character first and then the second. In the latter, you’ll choose several traits (attitude toward life, social status, images and metaphors associated with the character) and devote a paragraph to each. You may want to use a mix of these two approaches—for example, you may want to spend a paragraph apiece broadly sketching Huck’s and Jim’s personalities before transitioning into a paragraph or two that describes a few key points of comparison. This can be a highly effective strategy if you want to make a counterintuitive argument—that, despite seeming to be totally different, the two objects being compared are actually similar in a very important way (or vice versa). Remember that your essay should reveal something fresh or unexpected about the text, so think beyond the obvious parallels and differences.

Choose an image—for example, birds, knives, or eyes—and trace that image throughout Macbeth .

Sounds pretty easy, right? All you need to do is read the play, underline every appearance of a knife in Macbeth , and then list them in your essay in the order they appear, right? Well, not exactly. Your teacher doesn’t want a simple catalog of examples. He or she wants to see you make connections between those examples—that’s the difference between summarizing and analyzing. In the Macbeth example above, think about the different contexts in which knives appear in the play and to what effect. In Macbeth , there are real knives and imagined knives; knives that kill and knives that simply threaten. Categorize and classify your examples to give them some order. Finally, always keep the overall effect in mind. After you choose and analyze your examples, you should come to some greater understanding about the work, as well as your chosen image, symbol, or phrase’s role in developing the major themes and stylistic strategies of that work.

Is the society depicted in 1984 good for its citizens?

In this kind of essay, you’re being asked to debate a moral, ethical, or aesthetic issue regarding the work. You might be asked to judge a character or group of characters ( Is Caesar responsible for his own demise ?) or the work itself ( Is Jane Eyre a feminist novel ?). For this kind of essay, there are two important points to keep in mind. First, don’t simply base your arguments on your personal feelings and reactions. Every literary essay expects you to read and analyze the work, so search for evidence in the text. What do characters in 1984 have to say about the government of Oceania? What images does Orwell use that might give you a hint about his attitude toward the government? As in any debate, you also need to make sure that you define all the necessary terms before you begin to argue your case. What does it mean to be a “good” society? What makes a novel “feminist”? You should define your terms right up front, in the first paragraph after your introduction.

Second, remember that strong literary essays make contrary and surprising arguments. Try to think outside the box. In the 1984 example above, it seems like the obvious answer would be no, the totalitarian society depicted in Orwell’s novel is not good for its citizens. But can you think of any arguments for the opposite side? Even if your final assertion is that the novel depicts a cruel, repressive, and therefore harmful society, acknowledging and responding to the counterargument will strengthen your overall case.

5 Write the Introduction

Your introduction sets up the entire essay. It’s where you present your topic and articulate the particular issues and questions you’ll be addressing. It’s also where you, as the writer, introduce yourself to your readers. A persuasive literary essay immediately establishes its writer as a knowledgeable, authoritative figure.

An introduction can vary in length depending on the overall length of the essay, but in a traditional five-paragraph essay it should be no longer than one paragraph. However long it is, your introduction needs to:

Provide any necessary context.

Your introduction should situate the reader and let him or her know what to expect. What book are you discussing? Which characters? What topic will you be addressing?

Answer the “So what?” question.

Why is this topic important, and why is your particular position on the topic noteworthy? Ideally, your introduction should pique the reader’s interest by suggesting how your argument is surprising or otherwise counterintuitive. Literary essays make unexpected connections and reveal less-than-obvious truths.

Present your thesis.

This usually happens at or very near the end of your introduction.

Indicate the shape of the essay to come.

Your reader should finish reading your introduction with a good sense of the scope of your essay as well as the path you’ll take toward proving your thesis. You don’t need to spell out every step, but you do need to suggest the organizational pattern you’ll be using.

Your introduction should not:

Beware of the two killer words in literary analysis: interesting and important. Of course the work, question, or example is interesting and important—that’s why you’re writing about it!

Open with any grandiose assertions.

Many student readers think that beginning their essays with a flamboyant statement such as, “Since the dawn of time, writers have been fascinated with the topic of free will,” makes them sound important and commanding. You know what? It actually sounds pretty amateurish.

Wildly praise the work.

Another typical mistake student writers make is extolling the work or author. Your teacher doesn’t need to be told that “Shakespeare is perhaps the greatest writer in the English language.” You can mention a work’s reputation in passing—by referring to The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn as “Mark Twain’s enduring classic,” for example—but don’t make a point of bringing it up unless that reputation is key to your argument.

Go off-topic.

Keep your introduction streamlined and to the point. Don’t feel the need to throw in all kinds of bells and whistles in order to impress your reader—just get to the point as quickly as you can, without skimping on any of the required steps.

6 Write the Body Paragraphs

Once you’ve written your introduction, you’ll take the arguments you developed in step 4 and turn them into your body paragraphs. The organization of this middle section of your essay will largely be determined by the argumentative strategy you use, but no matter how you arrange your thoughts, your body paragraphs need to do the following:

Begin with a strong topic sentence.

Topic sentences are like signs on a highway: they tell the reader where they are and where they’re going. A good topic sentence not only alerts readers to what issue will be discussed in the following paragraph but also gives them a sense of what argument will be made about that issue. “Rumor and gossip play an important role in The Crucible ” isn’t a strong topic sentence because it doesn’t tell us very much. “The community’s constant gossiping creates an environment that allows false accusations to flourish” is a much stronger topic sentence— it not only tells us what the paragraph will discuss (gossip) but how the paragraph will discuss the topic (by showing how gossip creates a set of conditions that leads to the play’s climactic action).

Fully and completely develop a single thought.

Don’t skip around in your paragraph or try to stuff in too much material. Body paragraphs are like bricks: each individual one needs to be strong and sturdy or the entire structure will collapse. Make sure you have really proven your point before moving on to the next one.

Use transitions effectively.

Good literary essay writers know that each paragraph must be clearly and strongly linked to the material around it. Think of each paragraph as a response to the one that precedes it. Use transition words and phrases such as however, similarly, on the contrary, therefore, and furthermore to indicate what kind of response you’re making.

7 Write the Conclusion

Just as you used the introduction to ground your readers in the topic before providing your thesis, you’ll use the conclusion to quickly summarize the specifics learned thus far and then hint at the broader implications of your topic. A good conclusion will:

Do more than simply restate the thesis.

If your thesis argued that The Catcher in the Rye can be read as a Christian allegory, don’t simply end your essay by saying, “And that is why The Catcher in the Rye can be read as a Christian allegory.” If you’ve constructed your arguments well, this kind of statement will just be redundant.

Synthesize the arguments, not summarize them.

Similarly, don’t repeat the details of your body paragraphs in your conclusion. The reader has already read your essay, and chances are it’s not so long that they’ve forgotten all your points by now.

Revisit the “So what?” question.

In your introduction, you made a case for why your topic and position are important. You should close your essay with the same sort of gesture. What do your readers know now that they didn’t know before? How will that knowledge help them better appreciate or understand the work overall?

Move from the specific to the general.

Your essay has most likely treated a very specific element of the work—a single character, a small set of images, or a particular passage. In your conclusion, try to show how this narrow discussion has wider implications for the work overall. If your essay on To Kill a Mockingbird focused on the character of Boo Radley, for example, you might want to include a bit in your conclusion about how he fits into the novel’s larger message about childhood, innocence, or family life.

Stay relevant.

Your conclusion should suggest new directions of thought, but it shouldn’t be treated as an opportunity to pad your essay with all the extra, interesting ideas you came up with during your brainstorming sessions but couldn’t fit into the essay proper. Don’t attempt to stuff in unrelated queries or too many abstract thoughts.

Avoid making overblown closing statements.

A conclusion should open up your highly specific, focused discussion, but it should do so without drawing a sweeping lesson about life or human nature. Making such observations may be part of the point of reading, but it’s almost always a mistake in essays, where these observations tend to sound overly dramatic or simply silly.

Take a Study Break

Every Literary Reference Found in Taylor Swift's Lyrics

The 7 Most Messed-Up Short Stories We All Had to Read in School

QUIZ: Which Greek God Are You?

QUIZ: Which Bennet Sister Are You?

Anthony Cockerill

| Writing | The written word | Teaching English |

How to write great English literature essays at university

Essential advice on how to craft a great english literature essay at university – and how to avoid rookie mistakes..

If you’ve just begun to study English literature at university, the prospect of writing that first essay can be daunting. Tutors will likely offer little in the way of assistance in the process of planning and writing, as it’s assumed that students know how to do this already. At A-level, teachers are usually very clear with students about the Assessment Objectives for examination components and centre-assessed work, but it can feel like there’s far less clarity around how essays are marked at university. Furthermore, the process of learning how to properly reference an essay can be a steep learning curve.

But essentially, there are five things you’re being asked to do: show your understanding of the text and its key themes, explore the writer’s methods, consider the influence of contextual factors that might influence the writing and reading of the text, read published critical work about the text and incorporate this discourse into your essay, and finally, write a coherent argument in response to the task.

With advice from English teachers, HE tutors and other people who’ve been there and done it, here are the most crucial things to remember when planning and writing an essay.

Read around the subject and let your argument evolve.

‘One of the big step-ups from A-level, where students might only have had to deal with critical material as part of their coursework, is the move toward engaging with the critical debate around a text.’

Reading around the task and making notes is all important. Get familiar with the reading list. Become adept at searching for critical material in books and articles that’s not on the reading list. Talk with the librarian. Make sure you can find your way around the stacks. Get log-ins for the various databases of online criticism, such as the MLA International Bibliography .

‘Tutors are looking for flair… for students to be nuanced and creative with their ideas as opposed to reproducing the same criticism that others already have.’

When reading, keep notes, make summaries and write down useful quotations. Make sure you keep track of what you’ve read as you go. Note the publication details (author, publisher, year and place of publication). If you write down a quotation, note the page number. This will make dealing with citations and writing your bibliography much easier later on, as there’s nothing more annoying than getting to the end of the first draft of your essay and realising you’ve no idea which book or article a quote came from or which page it was on.

‘The more I read, the sharper my own writing style became because I developed an opinion of the writing style I liked and I had a clear sense of the subject matter that I was discussing.’

‘Don’t wing the reading. Or the thinking. Crap writing emerges from style over substance.’

Get to grips with the question and plan a response.

‘Brain dump at the start in the form of a mind map. This will help you focus and relax. You can add to it as go along and can shape it into a brief plan.’

Before writing a single word, brainstorm. Do some free-thinking. Get your ideas down on paper or sticky notes. Cross things out; refine. Allow your planning to be led by ideas that support your argument.

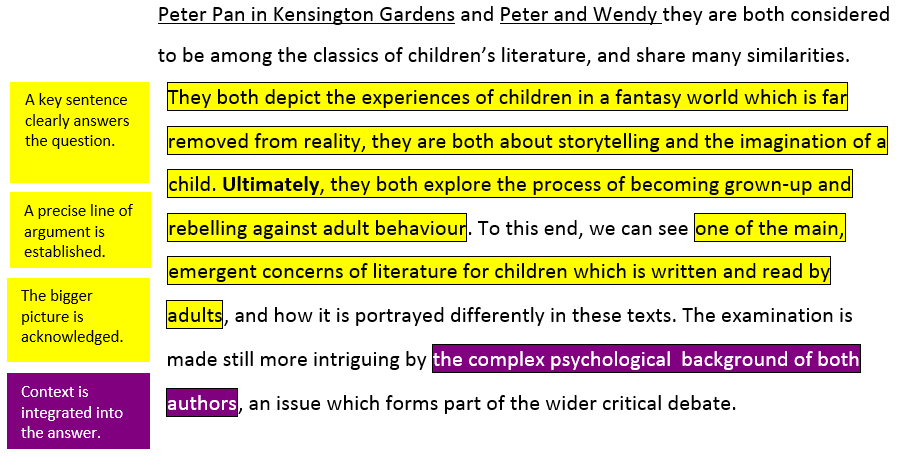

Use different colour-coded sticky notes for your planning. In the example below, the student has used yellow sticky notes for ideas, blue for language, structure and methods, purple for context and green for literary criticism, which makes planning the sequence of the essay much easier.

Structure and sequence your ideas

‘Make your argument clear in your opening paragraph, and then ensure that every subsequent paragraph is clearly addressing your thesis.’

Plan the essay by working out a sequence of your ideas that you believe to be the most compelling. Allow your ideas to serve as structural signposts. Augment these with relevant criticism, context and focus on language and style.

‘Read wide and look at different pieces of criticism of a particular work and weave that in with your own interpretation of said work.’

Write a great introduction.

‘By the end of the first paragraph, make sure you have established a very clear thesis statement that outlines the main thrust of the essay.’

Your introduction should make your argument very clear. It’s also a chance to establish working definitions of any problematic terms and to engage with key aspects of the wider critical debate.

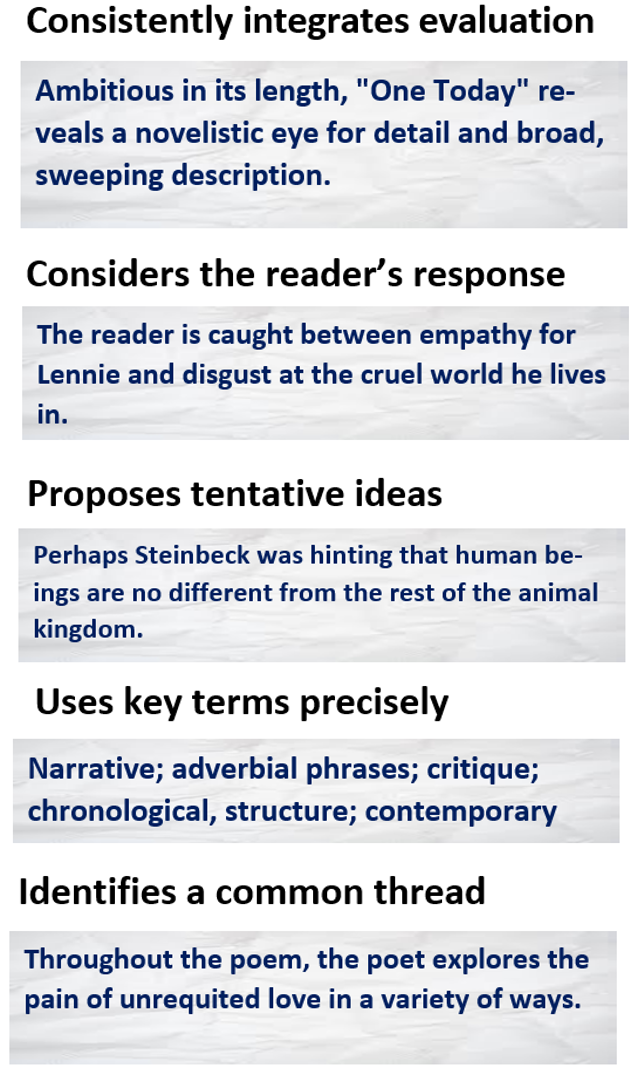

Get to grips with academic style and draft the essay

‘[Write with] an ‘exploratory’ tone rather than ‘dogmatic’ one.’

Academic writing is characterised by argument, analysis and evaluation. In an earlier post , I explored how students in high school might improve their analytical writing by adopting three maxims. These maxims are just as helpful for undergraduates. Firstly, aim for precise, cogent expression. Secondly, deliver an individual response supported by your reading – and citing – of published literary criticism. Thirdly, work on your personal voice. In formal analytical writing such as the university essay, your personal voice might be constrained rather more than it would be in a blog or a review, but it must nonetheless be exploratory in tone. Tentativity can be an asset as it suggests appreciation of nuances and alternative ways of thinking.

‘I got to grips with what was being asked of me by reading lots of literary criticism and becoming more familiar with academic writing conventions.’

Avoid unnecessary or clunky sign-post phrases such as ‘in this essay, I am going to…’ or ‘a further thing…’ A transition devices that can work really well is the explicit paragraph link, in which a motif or phrase in the last sentence of a paragraph is repeated in the first sentence of the next paragraph.

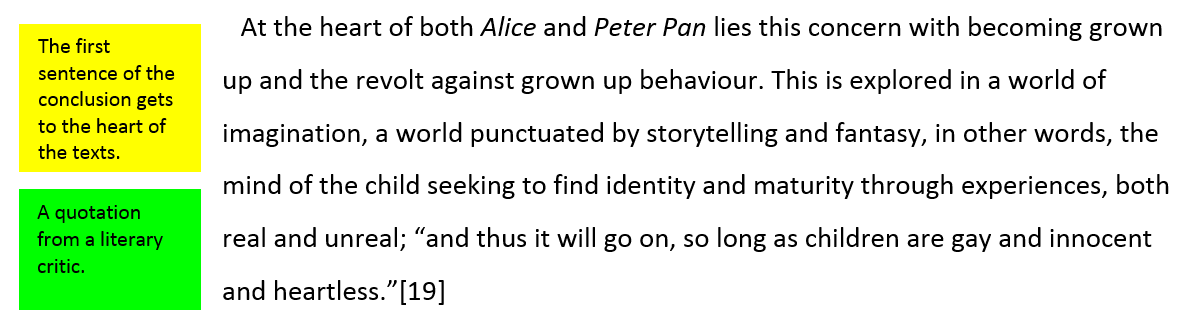

Write a killer conclusion

‘There is more emphasis on finding your own voice at university, something which in many ways is inhibited by Assessment Objectives at A-Level. I don’t think ‘good’ academic writing is necessarily taught very well in schools — at least from my experience.’

The conclusion is a really important part of your essay. It’s a chance to restate your thesis and to draw conclusions. You might achieve closure or instead, allude to interesting questions or ideas the essay has perhaps raised but not answered. You might synthesise your argument by exploring the key issue. You could zoom-out and explore the issue as part of a bigger picture.

Be meticulous in your referencing.

Having supported your argument with quotations from published critics, it’s important to be meticulous about how you reference these, otherwise you could be accused of plagiarism – passing someone else’s work off as your own. There are three broad ways of referencing: author-date, footnote and endnote. However, within each of these three approaches, there are specific named protocols. Most English literature faculties use either the MLA (Modern Languages Association of America) style or the Harvard style (variants of the author-date approach). It’s important to check what your faculty or department uses, learn how to use it (faculties invariably publish guidance, but ask if you’re unsure) and apply the rules meticulously.

‘Read your work aloud, slowly, sentence by sentence. It’s the best way to spot typos, and it allows you to hear what is awkward and/or ungrammatical. Then read the essay aloud again.’

Write with precision. Use a thesaurus to help you find the right word, but make sure you use it properly and in the right context. Read sentences back and prune unnecessary phrases or redundant words. Similarly, avoid words or phrases which might sound self-important or pompous.

Like those structural signposts that don’t really add anything, some phrases need to be omited, such as ‘many people have argued that…’ or ‘futher to the previous paragraph…’.

Finally, make sure the essay is formatted correctly. University departments are usually clear about their expectations, but font, size, and line spacing are usually stipulated along with any other information you’re expected to include in the essay’s header or footer. And don’t expect the proofing tool to pick up every mistake.

Featured image by Glenn Carstens-Peters on Unsplash

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- analytical writing

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- UCAS Guide Home >

- A-Level English Literature

How to Write an A-Level English Literature Essay

Writing an A-level English Literature essay is like creating a masterpiece. It’s a skill that can make a big difference in your academic adventure.

In this article, we will explore the world of literary analysis in an easy-to-follow way. We’ll show you how to organise your thoughts, analyse texts, and make strong arguments.

The Basics of Crafting A-Level English Literature Essays

Understanding the Assignment: Decoding Essay Prompts

Writing begins with understanding. When faced with an essay prompt, dissect it carefully. Identify keywords and phrases to grasp what’s expected. Pay attention to verbs like “analyse,” “discuss,” or “evaluate.” These guide your approach. For instance, if asked to analyse, delve into the how and why of a literary element.

Essay Structure: Building a Solid Foundation

The structure is the backbone of a great essay. Start with a clear introduction that introduces your topic and thesis. The body paragraphs should each focus on a specific aspect, supporting your thesis. Don’t forget topic sentences—they guide readers. Finally, wrap it up with a concise conclusion that reinforces your main points.

Thesis Statements: Crafting Clear and Powerful Arguments

Your thesis is your essay’s compass. Craft a brief statement conveying your main argument. It should be specific, not vague. Use it as a roadmap for your essay, ensuring every paragraph aligns with and supports it. A strong thesis sets the tone for an impactful essay, giving your reader a clear sense of what to expect.

Exploring PEDAL for Better A-Level English Essays

Going beyond PEE to PEDAL ensures a holistic approach, hitting the additional elements crucial for A-Level success. This structure delves into close analysis, explains both the device and the quote, and concludes with a contextual link.

Below are some examples to illustrate how PEDAL can enhance your essay:

Clearly state your main idea.

Example: “In this paragraph, we explore the central theme of love in Shakespeare’s ‘Romeo and Juliet.'”

Pull relevant quotes from the text.

Example: “Citing Juliet’s line, ‘My only love sprung from my only hate,’ highlights the conflict between love and family loyalty.”

Identify a literary technique in the evidence.

Example: “Analysing the metaphor of ‘love sprung from hate,’ we unveil Shakespeare’s use of contrast to emphasise the intensity of emotions.”

Break down the meaning of the evidence.

Example: “Zooming in on the words ‘love’ and ‘hate,’ we dissect their individual meanings, emphasising the emotional complexity of the characters.”

Link to Context:

Connect your point to broader contexts.

Example: “Linking this theme to the societal norms of the Elizabethan era adds depth, revealing how Shakespeare challenges prevailing beliefs about love and family.”

Navigating the World of Literary Analysis

Breaking Down Literary Elements: Characters, Plot, and Themes

Literary analysis is about dissecting a text’s components. Characters, plot, and themes are key players. Explore how characters develop, influence the narrative, and represent broader ideas. Map out the plot’s structure—introduction, rising action, climax, and resolution. Themes, the underlying messages, offer insight into the author’s intent. Pinpointing these elements enriches your analysis.

Effective Text Analysis: Uncovering Hidden Meanings

Go beyond the surface. Effective analysis uncovers hidden layers. Consider symbolism, metaphors, and imagery. Ask questions: What does a symbol represent? How does a metaphor enhance meaning? Why was a particular image chosen? Context is crucial. Connect these literary devices to the broader narrative, revealing the author’s nuanced intentions.

Incorporating Critical Perspectives: Adding Depth to Your Essays

Elevate your analysis by considering various perspectives. Literary criticism opens new doors. Explore historical, cultural, or feminist viewpoints. Delve into how different critics interpret the text. This depth showcases a nuanced understanding, demonstrating your engagement with broader conversations in the literary realm. Incorporating these perspectives enriches your analysis, setting your essay apart.

Secrets to Compelling Essays

Structuring your ideas: creating coherent and flowing essays.

Structure is the roadmap readers follow. Start with a captivating introduction that sets the stage. Each paragraph should have a clear focus, connected by smooth transitions. Use topic sentences to guide readers through your ideas. Aim for coherence—each sentence should logically follow the previous one. This ensures your essay flows seamlessly, making it engaging and easy to follow.

Presenting Compelling Arguments: Backing Up Your Points

Compelling arguments rest on solid evidence. Support your ideas with examples from the text. Quote relevant passages to reinforce your points. Be specific—show how the evidence directly relates to your argument. Avoid generalisations. Strong arguments convince the reader of your perspective, making your essay persuasive and impactful.

The Power of Language: Writing with Clarity and Precision

Clarity is key in essay writing. Choose words carefully to convey your ideas precisely. Avoid unnecessary complexity—simple language is often more effective. Proofread to eliminate ambiguity and ensure clarity. Precision in language enhances the reader’s understanding and allows your ideas to shine. Crafting your essay with care elevates the overall quality, leaving a lasting impression.

Mastering A-level English Literature essays unlocks academic success. Armed with a solid structure, nuanced literary analysis, and compelling arguments, your essays will stand out. Transform your writing from good to exceptional.

For personalised guidance, join Study Mind’s A-Level English Literature tutors . Elevate your understanding and excel in your literary pursuits. Enrich your learning journey today!

How long should my A-level English Literature essay be, and does word count matter?

While word count can vary, aim for quality over quantity. Typically, essays range from 1,200 to 1,500 words. Focus on expressing your ideas coherently rather than meeting a specific word count. Ensure each word contributes meaningfully to your analysis for a concise and impactful essay.

Is it acceptable to include personal opinions in my literature essay?

While it’s essential to express your viewpoint, prioritise textual evidence over personal opinions. Support your arguments with examples from the text to maintain objectivity. Balance your insights with the author’s intent, ensuring a nuanced and well-supported analysis.

Can I use quotes from literary critics in my essay, and how do I integrate them effectively?

Yes, incorporating quotes from critics can add depth. Introduce the critic’s perspective and relate it to your argument. Analyse the quote’s relevance and discuss its impact on your interpretation. This demonstrates a broader engagement with literary conversations.

How do I avoid sounding repetitive in my essay?

Vary your language and sentence structure. Instead of repeating phrases, use synonyms and explore different ways to express the same idea. Ensure each paragraph introduces new insights, contributing to the overall development of your analysis. This keeps your essay engaging and avoids monotony.

Is it necessary to memorise quotes, or can I refer to the text during exams?

While memorising key quotes is beneficial for a closed text exam, you can refer to the text during open text exams. However, it’s crucial to be selective. Memorise quotes that align with common themes and characters, allowing you to recall them quickly and use them effectively in your essay under time constraints.

How can I improve my essay writing under time pressure during exams?

Practise timed writing regularly to enhance your speed and efficiency. Prioritise planning—allocate a few minutes to outline your essay before starting. Focus on concise yet impactful analysis. Develop a systematic approach to time management to ensure each section of your essay receives adequate attention within the given timeframe.

Still got a question? Leave a comment

Leave a comment, cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Let's get acquainted ? What is your name?

Nice to meet you, {{name}} what is your preferred e-mail address, nice to meet you, {{name}} what is your preferred phone number, what is your preferred phone number, just to check, what are you interested in, when should we call you.

It would be great to have a 15m chat to discuss a personalised plan and answer any questions

What time works best for you? (UK Time)

Pick a time-slot that works best for you ?

How many hours of 1-1 tutoring are you looking for?

My whatsapp number is..., for our safeguarding policy, please confirm....

Please provide the mobile number of a guardian/parent

Which online course are you interested in?

What is your query, you can apply for a bursary by clicking this link, sure, what is your query, thank you for your response. we will aim to get back to you within 12-24 hours., lock in a 2 hour 1-1 tutoring lesson now.

If you're ready and keen to get started click the button below to book your first 2 hour 1-1 tutoring lesson with us. Connect with a tutor from a university of your choice in minutes. (Use FAST5 to get 5% Off!)

What is Essay? Definition, Usage, and Literary Examples

Essay definition.

An essay (ES-ey) is a nonfiction composition that explores a concept, argument, idea, or opinion from the personal perspective of the writer. Essays are usually a few pages, but they can also be book-length. Unlike other forms of nonfiction writing, like textbooks or biographies, an essay doesn’t inherently require research. Literary essayists are conveying ideas in a more informal way.

The word essay comes from the Late Latin exigere , meaning “ascertain or weigh,” which later became essayer in Old French. The late-15th-century version came to mean “test the quality of.” It’s this latter derivation that French philosopher Michel de Montaigne first used to describe a composition.

History of the Essay

Michel de Montaigne first coined the term essayer to describe Plutarch’s Oeuvres Morales , which is now widely considered to be a collection of essays. Under the new term, Montaigne wrote the first official collection of essays, Essais , in 1580. Montaigne’s goal was to pen his personal ideas in prose . In 1597, a collection of Francis Bacon’s work appeared as the first essay collection written in English. The term essayist was first used by English playwright Ben Jonson in 1609.

Types of Essays

There are many ways to categorize essays. Aldous Huxley, a leading essayist, determined that there are three major groups: personal and autobiographical, objective and factual, and abstract and universal. Within these groups, several other types can exist, including the following:

- Academic Essays : Educators frequently assign essays to encourage students to think deeply about a given subject and to assess the student’s knowledge. As such, an academic essay employs a formal language and tone, and it may include references and a bibliography. It’s objective and factual, and it typically uses a five-paragraph model of an introduction, two or more body paragraphs, and a conclusion. Several other essay types, like descriptive, argumentative, and expository, can fall under the umbrella of an academic essay.

- Analytical Essays : An analytical essay breaks down and interprets something, like an event, piece of literature, or artwork. This type of essay combines abstraction and personal viewpoints. Professional reviews of movies, TV shows, and albums are likely the most common form of analytical essays that people encounter in everyday life.

- Argumentative/Persuasive Essays : In an argumentative or persuasive essay, the essayist offers their opinion on a debatable topic and refutes opposing views. Their goal is to get the reader to agree with them. Argumentative/persuasive essays can be personal, factual, and even both at the same time. They can also be humorous or satirical; Jonathan Swift’s A Modest Proposal is a satirical essay arguing that the best way for Irish people to get out of poverty is to sell their children to rich people as a food source.

- Descriptive Essays : In a descriptive essay, the essayist describes something, someone, or an event in great detail. The essay’s subject can be something concrete, meaning it can be experienced with any or all of the five senses, or abstract, meaning it can’t be interacted with in a physical sense.

- Expository Essay : An expository essay is a factual piece of writing that explains a particular concept or issue. Investigative journalists often write expository essays in their beat, and things like manuals or how-to guides are also written in an expository style.

- Narrative/Personal : In a narrative or personal essay, the essayist tells a story, which is usually a recounting of a personal event. Narrative and personal essays may attempt to support a moral or lesson. People are often most familiar with this category as many writers and celebrities frequently publish essay collections.

Notable Essayists

- James Baldwin, “ Notes of a Native Son ”

- Joan Didion, “ Goodbye To All That ”

- George Orwell, “ Shooting an Elephant ”

- Ralph Waldo Emerson, “ Self-Reliance ”

- Virginia Woolf, " Three Guineas "

Examples of Literary Essays

1. Michel De Montaigne, “Of Presumption”

De Montaigne’s essay explores multiple topics, including his reasons for writing essays, his dissatisfaction with contemporary education, and his own victories and failings. As the father of the essay, Montaigne details characteristics of what he thinks an essay should be. His writing has a stream-of-consciousness organization that doesn’t follow a structure, and he expresses the importance of looking inward at oneself, pointing to the essay’s personal nature.

2. Virginia Woolf, “A Room of One’s Own”

Woolf’s feminist essay, written from the perspective of an unknown, fictional woman, argues that sexism keeps women from fully realizing their potential. Woolf posits that a woman needs only an income and a room of her own to express her creativity. The fictional persona Woolf uses is meant to teach the reader a greater truth: making both literal and metaphorical space for women in the world is integral to their success and wellbeing.

3. James Baldwin, “Everybody’s Protest Novel”

In this essay, Baldwin argues that Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin doesn’t serve the black community the way his contemporaries thought it did. He points out that it equates “goodness” with how well-assimilated the black characters are in white culture:

Uncle Tom’s Cabin is a very bad novel, having, in its self-righteous, virtuous sentimentality, much in common with Little Women. Sentimentality […] is the mark of dishonesty, the inability to feel; […] and it is always, therefore, the signal of secret and violent inhumanity, the mask of cruelty.

This essay is both analytical and argumentative. Baldwin analyzes the novel and argues against those who champion it.

Further Resources on Essays

Top Writing Tips offers an in-depth history of the essay.

The Harvard Writing Center offers tips on outlining an essay.

We at SuperSummary have an excellent essay writing resource guide .

Related Terms

- Academic Essay

- Argumentative Essay

- Expository Essay

- Narrative Essay

- Persuasive Essay

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Lit Century

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

Read the 1962 Short Story That Inspired This Year’s Met Gala Theme

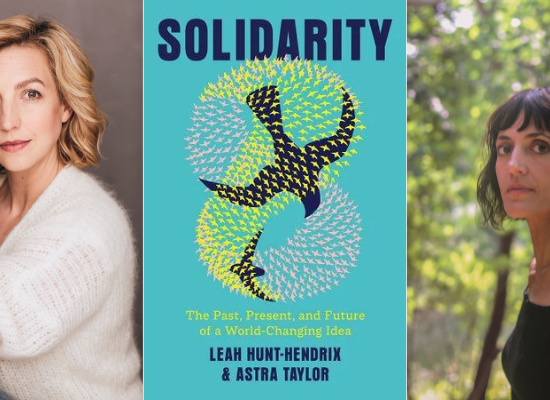

J.g. ballard’s “the garden of time”, i don’t want to talk to my coworker about their stupid writing: am i the literary asshole, kristen arnett answers your awkward questions about bad bookish behavior, the literary film & tv you need to stream in may, because somehow it’s still raining, from austen to larkin: why writers could be more prone to hypochondria, caroline crampton considers the intersection of creative pursuits and health anxiety, the problem with giant book preview lists, maris kreizman on one of the necessary evils of book coverage, crash again, crash better: a brief history of failed attempts at human flight, joe fassler ponders our innate desire to rise above it all, survival of the wealthiest: joseph e. stiglitz on the dangerous failures of neoliberalism, in which “the intellectual handmaidens of the capitalists” are taken to task, yan lianke wants you to stop describing him as china’s most censored author, on state censorship, artistic integrity, and the market forces behind local and global publishing, “pale fire” (tavi’s version): notes on taylor swift and the literature of obsessive fandom, leigh stein considers tavi gevinson’s new zine, “fan fiction”, how much is enough on the writerly balance between money and time, for novelist ryan chapman, “there are wants, and there are needs.”, writing as labor: doing more with less, together, david hill on the myth of the middle class writer, the money diaries: real writers, real budgets, what writers spend in a week of their lives, in service: writers on making ends meet in the service industry, “it’s easy to remain clueless about how the world works for most people.”, what christiane amanpour—and the rest of us—can learn from palestinian journalists in gaza, steven w. thrasher on the myth of the “independent journalist”, contemporary literary novels are haunted by the absence of money, naomi kanakia wonders why nobody talks about the thing we all need, premonition in the west bank: ben ehrenreich on life in the village of burin, “sometimes you hear an echo of a sound that has not yet been voiced, of a shot that has not yet been fired.”, 50 ways to end a poem, emily skaja has some recommendations for making a strong exit, a woman out of time: rebecca solnit on mary shelley’s dystopian sci-fi novel the last man, in praise of a truly innovative writer, 10 great new children’s books out in april, caroline carlsonrecommends maple lam, felicita sala, laurie morrison and more, vampires, selkies, familiars, and more april’s best sci-fi and fantasy books, career retrospectives and historical fantasies from cixin liu, ann leckie, leigh bardugo, and others, the literary film & tv you need to stream in april, april showers bring opportunities to binge watch, here’s your 2024 literary film & tv preview, 53 shows and movies to stream and see this year, lit hub’s most anticipated books of 2024, 230 books we’re looking forward to reading this year, 24 sci-fi and fantasy books to look forward to in 2024, exciting new series’ and standalones from kelly link, lev grossman, sofia samatar, james s.a. corey, and more, we need your help: support lit hub, become a member, you get editors’ personalized book recs, an ad-free reading experience, and the joan didion tote bag, 40 books to understand palestine, from ghassan kanafani's "men in the sun" to adania shibli's "minor detail", leah hunt-hendrix and astra taylor on solidarity, change, and our interconnected world.

In Conversation with Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan on Fiction/Non/Fiction

Finding a Home in Stories: 10 New Children’s Books to Read in May

Caroline Carlson Recommends Matt Hunt, Julie Flett, Vera Brosgol, and More

5 Book Reviews You Need to Read This Week

“Kafka seems both genius and ingenue, and the contradiction brings him closer to us.”

A Struggle for Survival: Inside Mexico City’s Illegal Detox Centers

Angela Garcia on Those Caught in the Crossfire of Mexico's Drug Wars

How a Multitude of Voices Can Broaden Our Understanding of the Natural World

Rebecca Kormos on the Changing Face of Nature and Climate Narratives

Professors, Priests, Provosts, Manholes, and More: 7 Poetry Books to Read This May

Rebecca Morgan Frank Recommends Catherine Barnett, Jeremy Michael Clark, Ann Jäderlund, and More

May 2, 2024