- Business Analytics for Managers: Leading with Data

- Entrepreneurial Leadership & Influence

- Entrepreneurial Leadership Essentials

- The Entrepreneurship Bootcamp: A New Venture Entrepreneurship Program

- Executive Leadership Program: Owning Your Leadership

- Innovation & Growth Post-Crisis

- Navigating Volatility & Uncertainty as an Entrepreneurial Leader

- Resilient Leadership

- Strategic Planning & Management in Retailing

- Leadership Program for Women & Allies

- Online Offerings Asia

- The Entrepreneurial Family

- Mastering Generative AI in Your Business

- Rapid Innovation Event Series

- Executive Entrepreneurial Leadership Certificate

- Graduate Certificate Credential

- Part-Time MBA

- Help Me Decide

- Entrepreneurial Leadership

- Inclusive Leadership

- Entrepreneurship

- Strategic Innovation

- Custom Programs

- Corporate Partner Program

- Sponsored Programs

- Get Customized Insights

- Business Advisory

- B-AGILE (Corporate Accelerator)

- Corporate Degree Programs

- Recruit Undergraduate Students

- Student Consulting Projects

- Graduate Student Outcomes

- Graduate Student Coaching

- Guest Rooms

- Resources & Tips

- Babson Academy Team

- One Hour Entrepreneurship Webinar

- Price-Babson Symposium for Entrepreneurship Educators

- Babson Fellows Program for Entrepreneurship Educators

- Babson Fellows Program for Entrepreneurship Researchers

- Building an Entrepreneurship Education Ecosystem

- Certificate in Youth Entrepreneurship Education

- Global Symposia for Entrepreneurship Educators (SEE)

- Babson Build

- Babson Entrepreneurial Thought & Action® (BETA) Workshop

- Entrepreneurial Mindset

- Custom Student Programs

- Facts and Stats

- Mission, Vision, & Values

- College Rankings & Accolades

- Babson’s Strategy in Action

- Community Updates

- Our Process

- Task Forces

- Multimodal Communications and Engagement Plan

- Notable Alumni

- Babson College History

- Roger Babson

- Babson Globe

- Accreditation

- For News Media

- Student Complaint Information

- Entrepreneurial Leadership at Babson

- Entrepreneurial Thought & Action

- Immersive Curriculum

- Babson, Olin, & Wellesley Partnership

- Prior Academic Year Publications

- The Babson Collection

- Teaching Innovation Fund

- The Proposal Process

- Services Provided

- Funding Support Sources

- Post-Award Administration

- Five Steps to Successful Grant Writing

- Simple Budget Template

- Simple Proposal Template

- Curriculum Innovation

- Digital Transformation Initiative

- Herring Family Entrepreneurial Leadership Village

- Stephen D. Cutler Center for Investments and Finance

- Weissman Foundry at Babson College

- Meeting the Moment

- Community Messages

- College Leadership

- Dean of the College & Academic Leadership

- Executives in Residence

- Entrepreneurs in Residence

- Filmmaker in Residence

- Faculty Profiles

- Research and Publications

- News and Events

- Contact Information

- Student Resources

- Division Faculty

- Undergraduate Courses

- Graduate Courses

- Areas of Study

- Language Placement Test

- Make An Appointment

- The Wooten Prize for Excellence in Writing

- How To Become a Peer Consultant

- grid TEST images

- Student Research

- Carpenter Lecture Series

- Visiting Scholars

- Undergraduate Curriculum

- Student Groups and Programming

- Seminar Series

- Best Projects of Fall 2021

- Publications

- Academic Program

- Past Conferences

- Course Listing

- Math Resource Center

- Emeriti Faculty Profiles

- Arthur M. Blank School for Entrepreneurial Leadership

- Anti-Racism Educational Resources

- Clubs & Organizations

- Safe Zone Training

- Ways to Be Gender Inclusive

- External Resources

- Past Events

- Meet the Staff

- JEDI Student Leaders

- Diversity Suite

- Leadership Awards

- Creativity Contest

- Share Your Service

- Featured Speakers

- Black Business Expo

- Heritage Months & Observances

- Bias-Related Experience Report

- Course Catalog

The Blank School engages Babson community members and leads research to create entrepreneurial leaders.

Looking for a specific department's contact information?

Learn about open job opportunities, employee benefits, training and development, and more.

- Why Babson?

- Evaluation Criteria

- Standardized Testing

- Class Profile & Acceptance Rate

- International Applicants

- Transfer Applicants

- Homeschool Applicants

- Advanced Credits

- January Admission Applicants

- Tuition & Expenses

- How to Apply for Aid

- International Students

- Need-Based Aid

- Weissman Scholarship Information

- For Parents

- Access Babson

- Contact Admission

- January Admitted Students

- Fall Orientation

- January Orientation

- How to Write a College Essay

- Your Guide to Finding the Best Undergraduate Business School for You

- What Makes the Best College for Entrepreneurship?

- Six Types of Questions to Ask a College Admissions Counselor

- Early Decision vs Early Action vs Regular Decision

- Entrepreneurship in College: Why Earning a Degree Is Smart Business

- How to Use Acceptance Rate & Class Profile to Guide Your Search

- Is College Worth It? Calculating Your ROI

- How Undergraduate Experiential Learning Can Pave the Way for Your Success

- What Social Impact in Business Means for College Students

- Why Study the Liberal Arts and Sciences Alongside Your Business Degree

- College Concentrations vs. Majors: Which Is Better for a Business Degree?

- Finding the College for You: Why Campus Environment Matters

- How Business School Prepares You for a Career Early

- Your College Career Resources Are Here to Help

- Parent’s Role in the College Application Process: What To Know

- What A College Honors Program Is All About

Request Information

- Business Foundation

- Liberal Arts & Sciences Foundation

- Foundations of Management & Entrepreneurship (FME)

- Socio-Ecological Systems

- Advanced Experiential

- Hands-On Learning

- Business Analytics

- Computational & Mathematical Finance

- Environmental Sustainability

- Financial Planning & Analysis

- Global & Regional Studies

- Historical & Political Studies

- Identity & Diversity

- International Business Environment

- Justice, Citizenship, & Social Responsibility

- Leadership, People, & Organizations

- Legal Studies

- Literary & Visual Arts

- Operations Management

- Quantitative Methods

- Real Estate

- Retail Supply Chain Management

- Social & Cultural Studies

- Strategy & Consulting

- Technology Entrepreneurship

- Undergraduate Faculty

- Global Study

- Summer Session

- Other Academic Opportunities

- Reduced Course Load Policy

- Leadership Opportunities

- Athletics & Fitness

- Social Impact and Sustainability

- Bryant Hall

- Canfield and Keith Halls

- Coleman Hall

- Forest Hall

- Mandell Family Hall

- McCullough Hall

- Park Manor Central

- Park Manor North

- Park Manor South

- Park Manor West

- Publishers Hall

- Putney Hall

- Van Winkle Hall

- Woodland Hill Building 8

- Woodland Hill Buildings 9 and 10

- Gender Inclusive Housing

- Student Spaces

- Policies and Procedures

- Health & Wellness

- Mental Health

- Religious & Spiritual Life

- Advising & Tools

- Internships & Professional Opportunities

- Connect with Employers

- Professional Paths

- Undergraduate News

- Request Info

- Plan a Visit

- How to Apply

98.7% of the Class of 2022 was employed or continuing their education within six months of graduation.

- Application Requirements

- Full-Time Merit Awards

- Part-Time Merit Awards

- Tuition & Deadlines

- Financial Aid & Loans

- Admission Event Calendar

- Admissions Workshop

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Contact Admissions

- Data Scientist Career Path & Business Analytics: Roles, Jobs, & Industry Outlook

- How to Improve Leadership Skills in the Workplace

- Is a Master’s in Business Analytics Worth It?

- Is a Master’s in Leadership Worth It? Yes. Find Out Why.

- The Big Question: Is an MBA Worth It?

- Is Online MBA Worth It? In a Word, Yes.

- Master in Finance Salary Forecast

- Masters vs MBA: How Do I Decide

- MBA Certificate: Everything You Need to Know

- MBA Salary Florida What You Can Expect to Make After Grad School

- Preparing for the GMAT: Tips for Success

- Admitted Students

- Find Your Program

- Babson Full Time MBA

- Master of Science in Management in Entrepreneurial Leadership

- Master of Science in Finance

- Master of Science in Business Analytics

- Certificate in Advanced Management

- Part-Time Flex MBA Program

- Part-Time Online MBA

- Blended Learning MBA - Miami

- Business Analytics and Machine Learning

- Quantitative Finance

- International Business

- STEM Masters Programs

- Consulting Programs

- Graduate Student Services

- Centers & Institutes

- Diversity, Equity, & Inclusion

- Kids, Partners, & Families

- Greater Boston & New England

- Recreation & Club Sports

- Campus Life

- Career & Search Support

- Employer Connections & Opportunities

- Full Time Student Outcomes

- Part Time Student Outcomes

- The Grad CCD Podcast

- Visit & Engage

Review what you'll need to apply for your program of interest.

Need to get in touch with a member of our business development team?

- Contact Babson Executive Education

- Contact Babson Academy

- Email the B-Agile Team

- Your Impact

- Ways to Give

- Make Your Mark

- Barefoot Athletics Challenge

- Roger’s Cup

- Alumni Directory

- Startup Resources

- Career Resources

- Back To Babson

- Going Virtual 2021

- Boston 2019

- Madrid 2018

- Bangkok 2017

- Cartagena 2015

- Summer Receptions

- Sunshine State Swing

- Webinar Library

- Regional Clubs

- Affinity Groups

- Volunteer Opportunities

- Classes and Reunion

- Babson Alumni Advisory Board

- College Advancement Ambassadors

- Visiting Campus

- Meet the Team

- Social Media

- Babson in a Box

- Legacy Awards

When you invest in Babson, you make a difference.

Your one-stop shop for businesses founded or owned by Babson alumni.

Prepare for the future of work.

- Tuition & Financial Aid

- Meet the Faculty Director

- Visit & Engage

- Lifelong Learning

- Babson Street

- Professional

- Faculty & Staff Programs

Learn to Lead a Thriving Entrepreneurship Education Ecosystem

In our increasingly dynamic and unpredictable world, an entrepreneurial mindset is quickly becoming a must-have trait. In order to best serve today’s students and prepare them for tomorrow’s future, university administrators and educators must understand the university-based entrepreneurship ecosystem.

Developing a thriving entrepreneurship education ecosystem is a collaborative effort. Institutions whose entrepreneurship education ecosystems are just beginning to form can accelerate their trajectory with the right network and support. Lay the groundwork to catalyze your school’s entrepreneurship efforts with proven frameworks and action plans from the No. 1 college for entrepreneurship in the United States.

- Watch the Q&A Webinar

Watch a video recording of professors Candida Brush and Patricia Greene discussing the program with prospective attendees and providing an overview of format, curriculum, and learning outcomes.

What Will You Learn?

Gain the approach, plan, guidance, and network of support you need to develop a high-impact entrepreneurship education ecosystem within your institution. Join entrepreneurship educator peers from around the world as you learn a hands-on approach for making progress on your campus. During this program for academic entrepreneurs, you will cover topics such as:

- Assessing your entrepreneurial ecosystem to understand gaps, opportunities, and barriers to progress

- How to develop strategies for overcoming challenges in moving your entrepreneurial initiatives forward

- Networking across the ecosystem to acquire resources, engage stakeholders, and build your reputation

- Leading change both inside and outside your institution

- Key success factors for how institutions create and develop entrepreneurship education ecosystems

- Assembling the resources to build and grow an entrepreneurship education ecosystem

- Gaining the tools to reflect on and amplify your personal entrepreneurial leadership capabilities

When faculty collaborate, as we are with this course, the exchange of ideas provides incredible opportunities for methods that engage students and foster optimal learning.

At A Glance

Who should attend.

This program is well suited for entrepreneurship faculty and administrators who are leading a center, institute, accelerator/incubator, or entrepreneurship project or initiative and who are interested in entrepreneurship education ecosystem development.

- Register Now

What You Need to Know

This three-week online program includes:

- Monday, February 19 from 9–11 a.m. EST

- Monday, February 26 from 9–11 a.m. EST

- Monday, March 4 from 9–11 a.m. EST

- Monday, March 11 from 9–11 a.m. EST

- Approximately 20 hours of session and self-paced work throughout the program.

Program materials include case studies, self-assessments, team projects, discussion boards, reflection exercises, and oral presentations.

A 10% discount is available for Babson Collaborative members. Please email [email protected] for more information about discounts.

Meet the Faculty

Candida Brush, Professor

Renowned entrepreneurship professor Candida Brush is a pioneering entrepreneurship researcher. She has co-authored reports for the OECD, the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, and the Goldman Sachs Foundation, and presented her work at the World Economic Forum in Davos and to the U.S. Department of Commerce. She has authored more than 160 publications including 13 books, and is one of the most highly cited researchers in the field.

Patricia Greene, Professor Emerita

Patricia Greene is Professor Emerita at Babson College. From 2017-2019, she served as the presidentially appointed 18th Director of the Women’s Bureau, U.S. Department of Labor. Prior to her term in Washington, D.C., she held the Paul T. Babson Chair in Entrepreneurial Studies at Babson College where she formerly served as Provost (2006-2008) and Dean of the Undergraduate School (2003-2006). Dr. Greene’s research focuses on the identification, acquisition, and combination of entrepreneurial resources, particularly by women and minority entrepreneurs. She is a founding member of the Diana Project and the founding national academic director for Goldman Sachs 10,000 Small Businesses Program.

What Makes Babson Academy Different?

At Babson Academy, we believe entrepreneurship education changes the world. To date, we have impacted more than 8,700 educators and students from 1,300 educational institutions in more than 80 countries. Our goal? Advancing global entrepreneurial learning across universities worldwide.

Our programs are about more than theory; they’re about action, and equipping you with the practical tools and strategies necessary to have an immediate impact on your institution.

Our Experts in the News

Faculty for the Building an Entrepreneurship Education Ecosystem program have deep expertise in building and growing robust entrepreneurship education ecosystems, all backed by Babson’s 28-year track record as the No. 1 College for entrepreneurship education in the United States.

Amplifying Entrepreneurial Learning Outside the Classroom

Candida Brush served as Babson’s Entrepreneurship Division chair for a decade before eventually becoming vice provost. In that role, she oversaw five of Babson’s academic centers, each focusing on different aspects of entrepreneurship, from family businesses to social enterprises.

Four Approaches to Teaching an Entrepreneurship Method

Patti Greene explains how teaching an entrepreneurship method rather than a process is the best way to combat unpredictability. There are four complementary techniques for teaching entrepreneurship as a method and each requires students to reach beyond their prediction-focused ways of knowing, analyzing, and talking.

Appreciating the Value of Entrepreneurial Women

According to Professor Candida Brush’s Global Entrepreneurship Monitor report, “the research highlights areas where women entrepreneurs have made significant progress, how ecosystems influence and are influenced by women entrepreneurs, and where there are still gaps, challenges, and opportunities.”

Want More Resources for Entrepreneurship Educators?

Become a Babson Collaborative member today, and join forces with 29 member institutions from 21 countries and counting. Gain access to a members-only portal, curriculum resources, the latest field research, the Collaborative WhatsApp community, and unparalleled networking with fellow entrepreneurship educators.

How and when will I have access to the course materials?

Course materials are provided via Canvas, Babson’s online learning portal. Materials will be made available to participants approximately one to seven days prior to the first live online session, depending on the amount of pre-work that participants are expected to complete in advance.

Where can I find the schedule for the days and times of the live online sessions?

The schedule will be sent to registered participants in the registration confirmation email (see the link in your confirmation email to the EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW document).

Do I need to join the virtual sessions live? Will they be recorded?

We highly recommend that participants join the live online sessions. It is an opportunity to ask questions, participate in rich discussion, and learn from the experience of your program peers. Session recordings will not consistently be available, and as such, it is expected that participants engage live in the virtual sessions.

What technology do you use for the live online programs?

- Canvas, Babson’s online learning portal —course calendar, readings, pre-work, faculty bios, presentations and post-session recordings are posted here.

- Video-conferencing Platform —we will use a virtual meeting application (like Webex or Zoom) that allows you to see and communicate with other participants simultaneously and in real time. Your instructor can share documents and interactive media, invite participants to share content, and engage with you in real-time participation. Links to sessions and more information will be provided on Canvas.

What do I need to participate? How do I prepare for the live online sessions?

Live sessions will be delivered via WeChat and Zoom.

Prior to each virtual session, please ensure you are prepared with the following:

- A computer/laptop with a webcam (built-in or external camera) for optimal viewing, but you may also join from a tablet or cellphone.

- Internet connection or cell hotspot

- Operating system: Windows: 7,8.1, or 10; Apple: OS 10.9 or higher

- Recommended browsers for optimal experience: HIGHLY RECOMMEND Google Chrome. Internet Explorer 11, Firefox 52, Safari 11 are not as optimal but should work as well. (Microsoft Edge, Internet Explorer 8, 9, 10, and Safari 7 are not recommended.)

- Headset with microphone (recommended but optional)

- Test your connection, audio and microphone by joining a Zoom test meeting.

What happens if I have technical issues?

Additional, detailed instructions will be provided on Canvas. Babson staff will be online and available to assist you, and will identify themselves during each live online delivery. Contact the staff via the chat function for help, or email them if needed. Contact information is available in the EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW document.

How long will I have access to the online materials?

Course materials on Canvas will be available for six months following the completion of the program.

When is payment due and what types of payment do you accept?

Payment is due in full at the time of registration. Babson accepts Visa, MasterCard, or American Express.

Do you offer discounts?

Discounts on Babson Academy courses are available for the following:

- Alumni of Babson College (undergraduate or graduate)

- Babson Collaborative members

- Groups of three or more registering at the same time

Please email [email protected] for more information and for discount codes before registering. In addition, please note that discounts cannot be combined.

Do you offer online programs for large groups from the same company?

Yes, we can customize a program to your company’s specific needs from our diverse certificate and courses portfolio. Please email [email protected] for additional information.

What will I receive upon completion of the program?

Each program participant receives a certificate of completion. We invite participants to add the program to their LinkedIn profile. Note that a certificate will not be provided if there is insufficient evidence of participation.

Do you have translation for non-English speaking participants?

We do not offer translation in our programs. Although we do not require the TOEFL, all Babson Academy programs are taught in English, so it is a prerequisite that you speak, read, and write English proficiently.

Where can I find information for in-person programs?

Explore Babson Academy’s full suite of programs .

What is your cancellation policy for live online programs?

Registration changes must be requested in writing to Babson Academy.

- Cancellations receive a 100% refund

- Substitutions* are allowed, subject to a $250 administration fee

- One-Time Transfers* allowed subject to a $250 administration fee, to be utilized within a one-year period

- Cancellations receive a 50% refund

- One-Time Transfers* are not allowed

- Cancellations do not receive a refund

- Substitutions* are not allowed

*Substitutions and transfers are subject to approval to ensure that participants and programs are suitable.

By submitting this form, you agree to receive communications from Babson College and our representatives about our educational programs and activities via phone and/or email. You can unsubscribe at any time by clicking Unsubscribe from an email.

Ready to Talk Now?

Contact Babson Academy [email protected]

ENTREPRENEURSHIP EDUCATION EVERY STUDENT, EVERY YEAR

As the future of work continues to evolve, entreed instills entrepreneurial mindsets in every student, every year to forge a more entrepreneurial america., our mission.

EntreEd champions entrepreneurship education, cultivating students for a prosperous future. Through leadership, professional development, advocacy, and networking. EntreEd curates educational practices and programs that forge entrepreneurial capabilities in all students.

Entrepreneurship education is not “one more thing” for our teachers – it can be done in any classroom setting seamlessly. We empower educators to shift their teaching strategies to further promote creativity, problem solving, and critical thinking skills within their students.

Our Offerings

EntreEd provides a strong collective network for entrepreneurial educators and professionals representing all aspects of entrepreneurial education. We support you and your entrepreneurial programming, initiatives, and innovations by offering a rich array of professional development options, resources, events, and networking opportunities.

EntreEd Academy

EntreEd Academy has immersive digital courses for K-12 educators to gain an understanding of entrepreneurship education, best practices for aligning entrepreneurship in their classroom, and resources to help students succeed in their future careers. These self-paced programs are applicable in any and every classroom.

AES Program

The America’s Entrepreneurial Schools (AES) initiative is a program designed to recognize K-12 schools that have provided entrepreneurship education to every student, every year. To earn the designation, schools must provide an entrepreneurship experience to every student in a school building in a given year.

SUBSCRIBE FOR UPDATES

Member Login

- Account Settings

- Upgrade Membership

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 30 March 2024

Entrepreneurial education and its role in fostering sustainable communities

- M. Suguna 1 ,

- Aswathy Sreenivasan 2 ,

- Logesh Ravi 3 , 4 ,

- Malathi Devarajan 1 ,

- M. Suresh 2 ,

- Abdulaziz S. Almazyad 5 ,

- Guojiang Xiong 6 ,

- Irfan Ali 7 &

- Ali Wagdy Mohamed 8

Scientific Reports volume 14 , Article number: 7588 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Socioeconomic scenarios

- Sustainability

Establishing sustainable communities requires bridging the gap between academic knowledge and societal requirements; this is where entrepreneurial education comes in. The first phase involved a comprehensive review of the literature and extensive consultation with experts to identify and shortlist the components of entrepreneurship education that support sustainable communities. The second phase involved Total Interpretative Structural Modelling to explore or ascertain how the elements interacted between sustainable communities and entrepreneurial education. The factors are ranked and categorized using the Matrice d'impacts croises multiplication appliquee an un classement (MICMAC) approach. The MICMAC analysis classifies partnerships and incubators as critical drivers, identifying Student Entrepreneurship Clubs and Sustainability Research Centers as dependent elements. The study emphasizes alumni networks and curriculum designs as key motivators. The results highlight the critical role that well-designed entrepreneurial education plays in developing socially conscious entrepreneurs, strengthening communities, and generating long-term job prospects. The study provides a valuable road map for stakeholders dedicated to long-term community development agendas by informing the creation of strategic initiatives, curriculum updates, and policies incorporating entrepreneurial education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Determinants of behaviour and their efficacy as targets of behavioural change interventions

The impact of artificial intelligence on employment: the role of virtual agglomeration

The role of artificial intelligence in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals

Introduction.

Sustainability represents a fresh way of reframing the interaction between people and the natural world, making it more than merely a research topic. It emphasizes how inadequate environmental protection is on its own. Instead, pursuing sustainability necessitates looking beyond self-interest and addressing social and economic aspects 1 , 2 . Thinking ahead means ensuring the next generation has at least as many opportunities as the current one 3 . The next generation's new models for balancing ecosystems—which combine socioeconomic development and environmental protection—may be sparked by sustainable education and trust 4 . Sustainable development is critical to our shared future, and entrepreneurship is acknowledged as a powerful driver of this sustainable economic growth 5 , 6 . In order to thrive without sacrificing future demands, modern businesses are aggressively implementing sustainability concepts 7 . Entrepreneurial skills are needed to address sustainability's social, economic, and environmental aspects and overcome challenges in today's rapidly evolving global world. The significance of entrepreneurial education in preparing people for sustainability-focused projects is shown by the emphasis on the entrepreneurial spirit in the shift to sustainable communities 8 . Smart cities (SC) should implement specific measures to prevent isolation in academic institutions, thereby fostering the formation of community clusters. Furthermore, since encouraging immigrant entrepreneurship can boost the local economy, SC should lessen the difficulties associated with starting a firm and providing mentorship and training to entrepreneurs involved in administration and regulation 9 .

Recent research underscores the significance of integrating sustainability into entrepreneurial education. Kotla and Bosman 10 argue for a multifaceted strategy to bridge the gap between integrating sustainability and entrepreneurship in higher education. The difficulties arise from the necessity of fusing the long-term, systemic perspective required by sustainability with the dynamic, frequently unpredictable character of entrepreneurship. In light of the numerous and intricate difficulties we face today, Klapper and Fayolle 11 suggest redefining entrepreneurial education to effectively address sustainability, social justice and hope. In order to assist with the purpose of sustainability, Fanea-Ivanovici and Baber 12 look into how colleges may help Indian students who aspire to be future entrepreneurs by promoting sustainability and sustainable development goals.

As a multifaceted approach, entrepreneurial education fosters creativity, adaptability, and a profound understanding of socioeconomic dynamics 13 . It explores the profound effects of an entrepreneurial mindset on social structures, environmental preservation, and long-term economic sustainability in society, going beyond traditional business acumen. This study's main objective is to investigate the variables that influence how entrepreneurship education contributes to the development of sustainable communities.

Although there is a growing corpus of research examining the distinct effects of sustainable community development and entrepreneurial education 6 , 14 , 15 , a thorough grasp of the complex interactions between these two fields is noticeably lacking. This research gap highlights the need for a study that uses a systematic modeling method to reveal the complex linkages between sustainable community development and entrepreneurial education and explore the individual contributions of these two phenomena. By providing a novel on the practical ways in which entrepreneurial education may support sustainable community development, this study aims to close this gap. Based on the latest developments in sustainability research and entrepreneurship education, our method uses Total Interpretive Structural Modeling (TISM) to methodically examine the intricate connections between these fields. Our research attempts to provide detailed knowledge of how entrepreneurial education might encourage sustainable community development in various socioeconomic circumstances by identifying essential components and their interdependencies. The novelty of our study resides in its theoretical framework and methodological approach, which combine ideas from the most recent literature with empirical analysis to provide practitioners, policymakers, and educators with helpful information. We contribute to the theoretical debate on sustainable entrepreneurial education by synthesizing and expanding on existing research and providing helpful advice for creating successful educational initiatives and policy interventions.

TISM, particularly influential within the context of startups, is employed in this study to answer the following research questions: “What are the factors influencing the role of entrepreneurship education in fostering sustainable communities? How do they influence one another and entrepreneurship education in fostering sustainable communities? Which factors drive others, and which factors depend on others? Can the priority of each of these factors be measured?”

Our study takes a two-pronged approach, starting with a thorough qualitative analysis to pinpoint the variables influencing the contribution of entrepreneurship education to sustainable community development. To provide a balanced view, we also consulted a review of the literature and expert comments. After that, we move into a quantitative phase where we use TISM to methodically investigate the interactions between these components, revealing their hierarchical structure and effects on the entrepreneurial education ecosystem. This mixed-methods approach guarantees a comprehensive analysis by combining quantitative clarity with qualitative depth to shed light on the intricate dynamics involved in utilizing entrepreneurship education for sustainable community development.

Table 1 presents the identified factors influencing the role of entrepreneurship education in fostering sustainable communities:

This paper is structured as follows: The research approach is discussed in the subsequent section, presenting findings and discussions. Subsequently, the paper depicts managerial/practical, theoretical, and societal contributions while finally including the conclusion, limitations, and future study areas.

Research methodology

In order to assess the influence of the identified enablers, this study uses a closed-ended questionnaire with pairwise comparisons 26 . Semi-structured interviews provide detailed insights because they are exploratory in character 27 . Data analysis techniques include TISM and MICMAC analyses. The study use snowball sampling to identify participants aware of the importance of entrepreneurship education in sustainable communities. Prioritizing convenience over ethical considerations led to conducting one-hour company interviews over a month. Twenty-seven Indian entrepreneurs from various industries and areas participated in the study. Participants had various experiences and viewpoints because they were involved in different business endeavors. Convenience played a role in participant selection, but ethical considerations came first. The study proactively ensured adherence to the highest ethical standards by implementing necessary measures. It sought informed consent to prioritize participants' autonomy by outlining the study's goals and ensuring voluntary participation. Strict protocols protected confidentiality and privacy; personally identifying information was securely managed, available only to the research team, and never revealed in published data or conclusions. These ethical protections highlight the dedication to participant welfare and scientific integrity throughout the study. The closed-ended survey consists of broad and specific questions that are scored on a five-point Likert scale to determine how different elements affect the development of sustainable communities. A TISM and MICMAC are employed to identify the prominent, influential relations amongst entrepreneurship education's contribution to sustainable communities.

Data analysis method

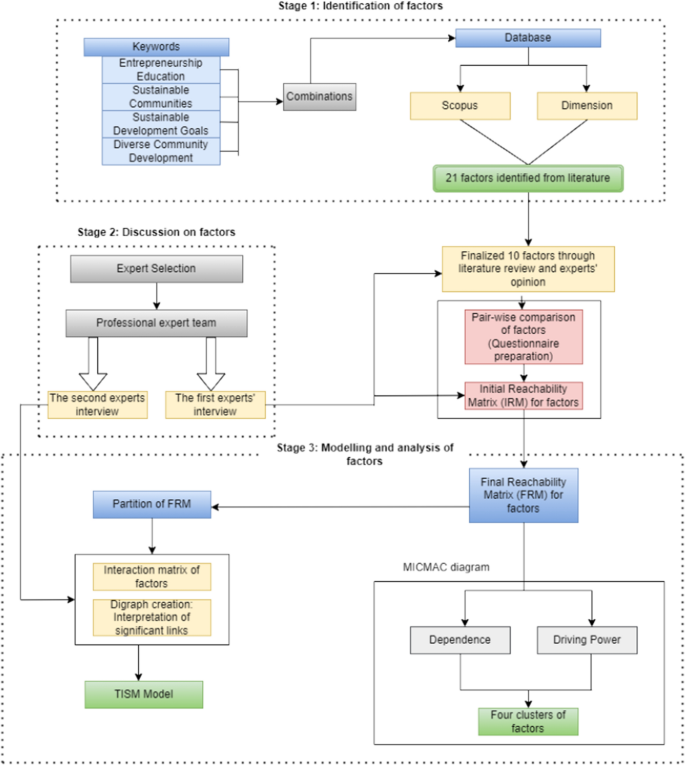

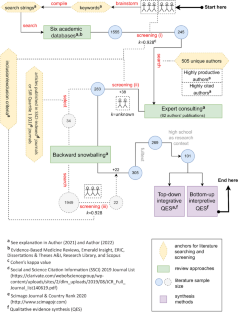

Figure 1 shows the steps in the research approach sequence. The conventional ISM approach, which creates a contextual relationship-based performance framework, is expanded upon by TISM 28 . The detected components and their associated order structure are displayed in the structural model created using the TISM methodology by their reciprocal influencing relationships 29 . The TISM technique facilitates the modeling of interrelationships between variables in a digraph form. An arrow represents the flow and hierarchical order of the relationships between the elements. The connecting arrow denotes the contextual connections between any two elements, and the levels at which the significant aspects are ultimately organized in the diagram define the influencing factors. TISM builds the model by considering just the most useful transitive relationships and leverages expert input to confirm the trustworthy source of transitivity, if any. In line with the approaches taken by other researchers, this study models entrepreneurship education variables and their function in creating sustainable communities using TISM 30 (Jayalaksmi & Pramod, 2015). TISM modeling commences with the critical task of identifying and defining the components for analysis.

Flow of TISM approach for entrepreneurship education and its role in fostering sustainable communities.

The study determines the critical components of entrepreneurship education contribution to sustainable communities through a survey of the literature and expert discussions. During our literature evaluation, we carefully examined every peer-reviewed article released in the past. This comprehensive research aimed to gather various viewpoints regarding the effects, modes of operation, and results of entrepreneurship education about sustainable community development. We held expert discussions after the literature review to deepen our comprehension of the crucial elements found. We investigated their perspectives on successful teaching strategies, obstacles encountered when including sustainability in entrepreneurship education, and possible long-term effects on communities through semi-structured interviews. Through these discussions, we could confirm our conclusions from the literature review and pinpoint any new themes or neglected regions. By integrating findings from expert talks and the literature review, we developed a comprehensive and evidence-based framework that outlines the essential elements of entrepreneurship education that support sustainable communities. Table 1 displays ten components and pertinent references chosen from a list of twenty-one. After identifying factors, the next step is to ascertain the contextual connections among these elements. Subject matter experts offer perspectives that shed light on these linkages. These connections within the framework suggest that “factor A influences or improves factor B.” Based on experts' judgments, a “pairwise interaction matrix” is created to show the interactions between the elements.

TISM goes above and beyond Interpretive Structural Modelling (ISM) by elucidating these linkages' mechanisms. A high influence is denoted by a 1 in the Initial Reachability Matrix (IRM) (Table 2 ), whereas a low influence is indicated by a 0. The Final Reachability Matrix (FRM) was created by appending the “transitivity rule” to the IRM (Table 3 ). Following transitivity testing, the transitive elements—represented by the number “0” in the IRM—are replaced with “1*” in the FRM. Organizing components level by level is the next stage. With other influencing factors, variables comprise the “antecedent set,” each factor's “reachability set” consists of further elements it might affect. For every aspect, the “intersection set” is found. The element-sharing entities with the “intersection set” and the “reachability set” are advanced to the top level in each iteration. The study repeats this process until all element levels are determined. The “interaction matrix design” is shown in Table 4 .

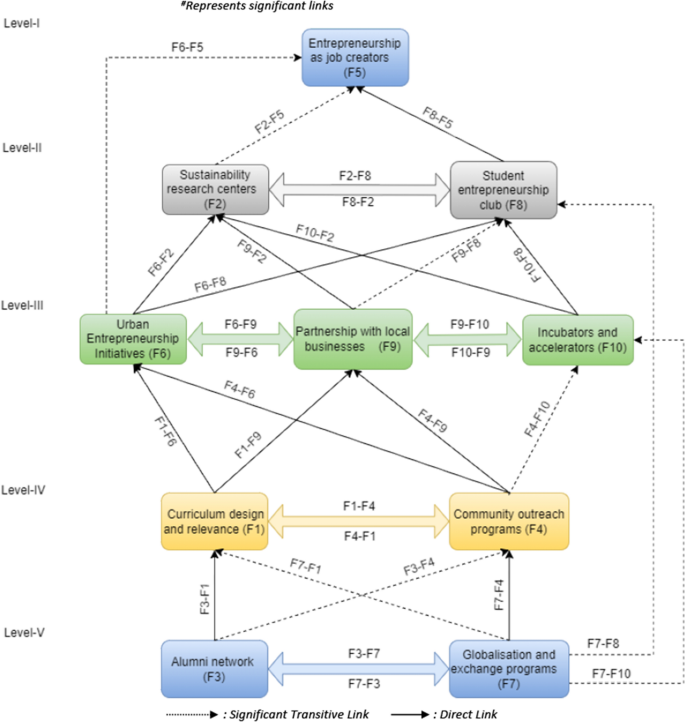

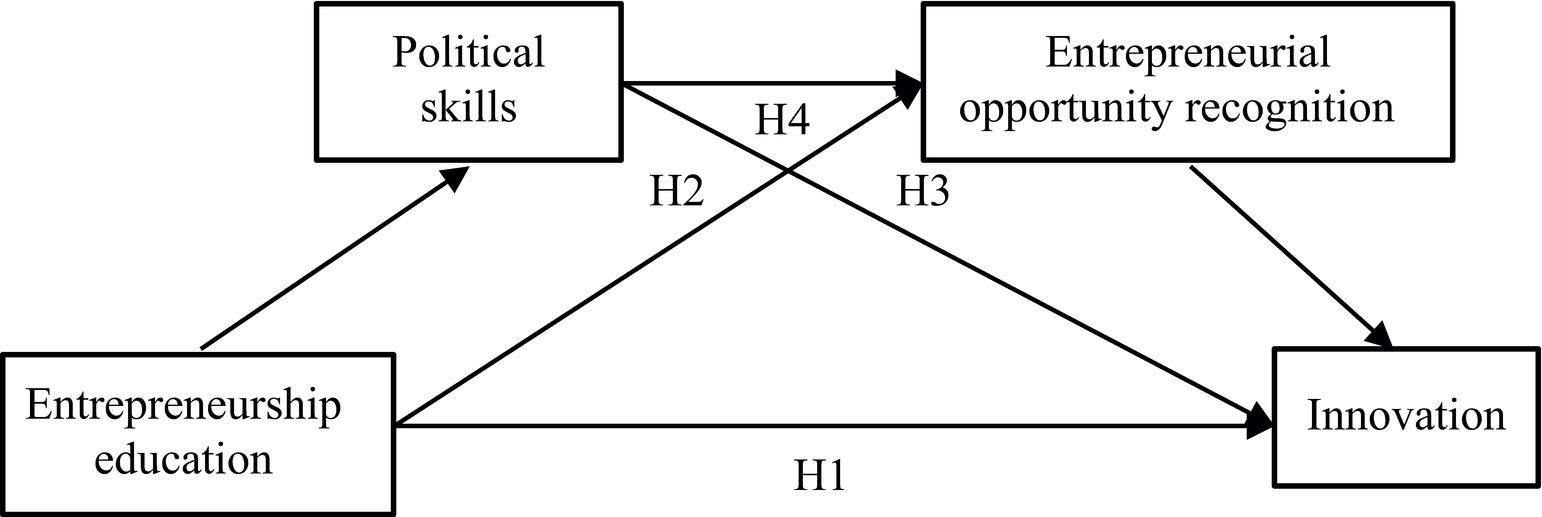

A directed graph (digraph) is produced by visually organizing the elements based on their levels and connecting them through the linkages found in the FRM. The digraph includes all “transitive links” and provides insightful explanations. Every relationship in TISM is defined and explained logically. Developing interpretive assertions about the digraph's links is part of this process. The study then utilizes the data to construct the TISM model (Fig. 2 ) by replacing the factors with the digraph nodes.

TISM model for factors influencing entrepreneurial education.

Ethical considerations

The Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham (AVV) institutional review board approved the study, and we obtained a formal letter of permission from Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham, the school of business, with registration number ERB-ASB-2023-020. There is no potential risk that may cause any harm to respondents. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study received ethical approval from the AVV Ethical Review Committee and written informed consent from each participant. The study ensured that all methods complied with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Interpretation of TISM digraph

Figure 2 visually depicts the TISM analysis of factors influencing entrepreneurial education and its role in promoting sustainable communities, while Table 5 provides an interpretation of the findings.

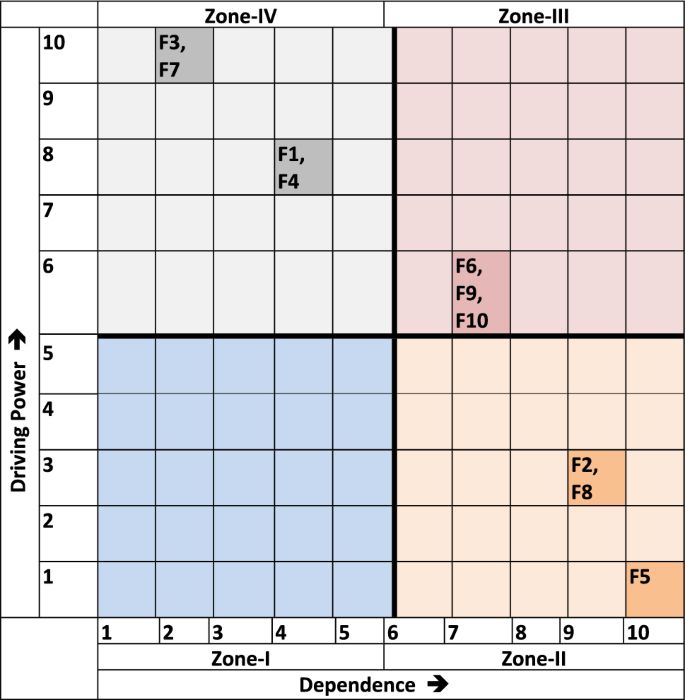

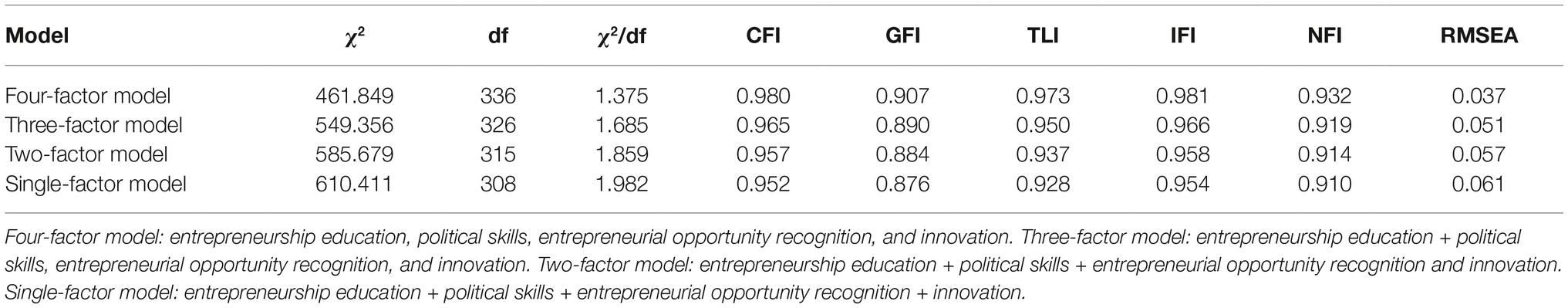

MICMAC analysis

Compared to previous multi-attribute techniques, TISM has several advantages, but it still cannot analyze the strength and relationship between the components. MICMAC addresses this TISM problem by categorizing the relationships between the components to make the concept of driving and dependency power more understandable. It also distinguishes between strong and weak elements since their interactions are not consistently balanced and can alter in response to environmental demands 43 . The MICMAC framework identifies four main zones as elements associated with entrepreneurial education: autonomous factors, dependent factors, linkage factors, and driving (independent) factors. The following are each zone’s characteristics:

Autonomous factors (Zone 1): These are known as autonomous enablers with weak reliance and

Driving power 44 . Notably, this study’s components do not fall under this autonomous zone.

Dependence factors (Zone 2): We classify these variables as dependence factors because other variables strongly depend on them but have a lower driving force 45 .

Linkage factors (Zone 3): Linkage factors are those that exhibit both firm reliance and strong driving power and driving or independent factors: These are what are known as driving or independent factors since they have a significant driving force in curriculum design and relevance, and community outreach initiatives are among the motivating elements found in this study.

Driving factors (Zone 4): These variables are referred to as driving factors since they strongly drive the other variables but have a lower dependence 45 . Table 6 presents the ranking of the elements impacting entrepreneurial education based on the MICMAC analysis.

To illustrate the MICMAC analysis, Fig. 3 presents the corresponding graph. Based on its driving force and dependence, Table 5 ranks the variables impacting entrepreneurial education and its function in developing sustainable communities. The rankings place globalization and exchange programs (F7) and alumni networks (F3) at the top. The MICMAC analysis ranks entrepreneurship as job producers (F5) at the fifth position. It indicates a greater reliance on external factors.

MICMAC graph.

Discussion and implications

The complex web of interconnected components that make up entrepreneurial education emphasizes the need for a comprehensive approach to promote long-term community development. This conversation explores the consequences of our research and compares it with existing literature to highlight how vital entrepreneurial education is in promoting sustainable behaviors in various contexts.

Our research points to sustainable education as a crucial component, consistent with the body of literature highlighting the transformational potential of education in fostering sustainable practices and beliefs 46 . In line with UNESCO's emphasis on Education for Sustainable Development, entrepreneurial education incorporating sustainability into the curriculum generates socially and environmentally conscious entrepreneurs and sparks creative solutions to urgent global issues 47 .

Our research demonstrates how entrepreneurial education can foster inclusive and resilient economic growth, and the study highlights workable solutions for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals through entrepreneurship. These solutions include encouraging urban entrepreneurship and supporting incubators and accelerators, which are approaches backed by research on the vital role of entrepreneurship in sustainability. Our study proposes a balanced strategy integrating social equality, economic viability, and environmental stewardship into the entrepreneurial education ecosystem while adopting a pragmatic sustainability perspective. This concept is consistent with the triple bottom line approach—which takes sustainability to include social, environmental, and economic aspects—discussed in the literature 48 . Focusing on a practical approach emphasizes how important it is for entrepreneurial education programs to equip students with the skills they need to traverse and balance various dimensions successfully.

Our study's findings, which highlight the interdisciplinarity in successful entrepreneurial education programs, emphasize how critical it is to transcend conventional academic boundaries to handle challenging sustainability issues. Literature emphasizing the importance of interdisciplinary approaches in generating innovation and problem-solving abilities required for sustainable development supports this finding 49 .

Our research actively highlights the importance of stakeholder engagement in strengthening the ecosystem of entrepreneurial education for sustainability. It is consistent with research showing that partnerships, local expertise, and a better understanding of community needs are all made possible through stakeholder participation, strengthening educational efforts' resilience and sustainability.

This study, which enriches theories by analyzing the effect of entrepreneurship education on sustainable community development, uses TISM as a methodological framework. The results highlight how entrepreneurial education can support socially conscious behavior and support comprehensive strategies for long-term community sustainability.

By emphasizing sustainability, entrepreneurial education helps underprivileged populations become more powerful, which lowers inequality and promotes inclusive economic growth. This socially responsible strategy fosters the development of a new generation of company leaders, encouraging moral behavior and long-term job creation. It improves civic engagement, community resilience, and environmental stewardship. Promoting sustainable habits in society and stimulating innovation are two benefits of entrepreneurial education that may extend to public health. In conclusion, including sustainability in education has long-term advantages that range from enhanced quality of life to social cohesion and economic development.

With its practical implications, this study substantially improves community sustainability via entrepreneurial education. Specific implications and additions to the sustainability of communities are:

Program designers and instructors should take a comprehensive approach to creating and executing entrepreneurial education initiatives. Understanding how these elements are related to one another is essential for a thorough and successful educational plan.

Educational institutions and support networks must prioritize adaptability and ongoing observation. Ensuring the robustness of dependent factors through responsiveness to environmental changes sustains the efficacy of entrepreneurial education programs.

These linkage elements (i.e., initiatives promoting urban entrepreneurship, alliances with nearby companies, incubators, and accelerators) should be actively supported and funded by policymakers and local government units. Acknowledging their critical role in establishing strong connections inside the system creates an atmosphere favorable for long-term entrepreneurial endeavors.

Educators and policymakers should prioritize the driving factors when creating and executing programs for entrepreneurial education.

Highlighting these elements strengthens the overall effectiveness and success of community-focused entrepreneurship projects

General contributions to the sustainability of the community are:

Policymakers, educators, and support groups can use the study's findings to build entrepreneurial education programs tailored to sustainable community development.

The recommendations include redesigning courses, judiciously assigning resources, and offering educators specialized training. These actions enhance the effectiveness and long-term success of entrepreneurship education programs.

Local government agencies and development organizations should collaborate by aligning their initiatives with educational objectives. For businesses and entrepreneurs, ongoing evaluations offer insightful information that promotes long-term success.

Including sustainability as a critical education component empowers marginalized groups, lowers inequality, encourages inclusive economic growth, and develops socially conscious behavior.

The socially responsible approach fosters a new generation of socially conscious leaders enabled through entrepreneurial education. It also increases civic involvement, community resilience, and environmental stewardship.

Investigating the complex interactions between entrepreneurship education and its influence on developing sustainable communities is crucial, as demonstrated using TISM and MICMAC analysis. The understanding of entrepreneurship education as a complex ecosystem with interdependent parts that work together to achieve sustainability is the fundamental tenet of our research. The meticulous mapping of these elements has shed light on the ecosystem's dynamism and complexity, exposing a web of interrelationships that support the idea that entrepreneurship education can support the establishment of sustainable communities.

Through TISM and MICMAC analysis, this study explores the function of entrepreneurship education in promoting sustainable communities. Using this method, we could map the roles and relationships of 10 critical components of the entrepreneurship education ecosystem. It improved the comprehension of how these components work together to affect sustainability. According to our analysis, every element in the entrepreneurship education ecosystem actively works to create sustainable communities; not a single element operates independently. It demonstrates the intricate nature of the ecosystem, in which each element—including dependent elements like student entrepreneurial groups and sustainability research centers—plays a vital role. These dependent components highlight the interconnectedness of the ecosystem and the need for supportive interactions to meet sustainability goals. Their distinction lies in their low driving strength and high dependence on influence from more dominant forces. Our findings reveal a startling fact: the entrepreneurial education ecosystem is incredibly intertwined. Each component is essential to the general health and effectiveness of the ecosystem, meaning that this interconnection is not just structural but also functional. Identifying interdependent components, such as sustainability research centers and student entrepreneurial clubs, highlights the delicate balance of the ecosystem, where the vitality of its constituent parts influences the resilience and flexibility of the whole.

The study emphasizes the significance of driving forces and linking factors as crucial components that create connections and advance the ecosystem. Establishing connections with nearby businesses, initiatives promoting urban entrepreneurship, and the thoughtful planning of the curriculum are essential for connecting the many components of the ecosystem and focusing their combined efforts on achieving lasting results. The results above highlight the need for a systematic and comprehensive strategy to improve the ecosystem of entrepreneurship education, stressing the vital functions of stakeholder collaboration, curricular relevance, and community involvement.

Linkage variables show a substantial dependence on other factors and significantly influence them. Examples of these are relationships with local firms and urban entrepreneurship efforts. These constituents are crucial in connecting disparate elements of the entrepreneurship education framework, guaranteeing a unified and cooperative endeavor to cultivate sustainable communities.

Through integrating TISM to examine variables affecting sustainable community development, this study promotes ideas related to entrepreneurship education. Theoretical ramifications include developing comprehensive frameworks for sustainability and improving social entrepreneurship ideas. Practical applications guide governments, entrepreneurship organizations, educational institutions, and community leaders. Opportunities for inclusive employment, socially responsible company practices, and community empowerment are among the societal effects. However, the dynamic nature of entrepreneurial ecosystems and findings particular to a given setting are limits. The paper provides complementary strategies for future research and advises caution when extrapolating results. The study offers a comprehensive grasp of the variables in entrepreneurial education. However, it also calls for more investigation into contextual variations, longitudinal impacts, the effectiveness of interventions, and regional/cultural influences. Overall, it emphasizes how entrepreneurship education can be revolutionary when it aligns with environmental goals and helps create sustainable communities and resilient economies.

Although our study offers insightful information about the connection between sustainable community development and entrepreneurship education, it is important to recognize several limitations that could impact how our findings are interpreted and applied more broadly. Due to the specific environment of this study, its conclusions might only apply to some situations or demographics. Cultural variations, economic conditions, and educational systems contribute to distinct effects on the dynamics of entrepreneurship education and its impact on community sustainability across different contexts. New ideas, regulations, and methods are constantly emerging in sustainable community development and entrepreneurial education. Although our analysis offers a quick overview of the situation, it might not account for long-term patterns or upcoming advancements in the sector. Given these limitations, it is essential to interpret the results with caution and to remember that further research is needed to examine these correlations in greater detail using a variety of approaches, contexts, and sample sizes. Our intention in disclosing these limitations is to foster openness and stimulate thoughtful consideration of the extent and consequences of our research.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Baker, M., Gray, R. & Schaltegger, S. Debating accounting and sustainability: From incompatibility to rapprochement in pursuing corporate sustainability. Account. Audit. Account. J. 36 (2), 591–619 (2023).

Article Google Scholar

Kim, R. C. Rethinking corporate social responsibility under contemporary capitalism: Five ways to reinvent CSR. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 31 (2), 346–362 (2022).

Biancardi, A. et al. Strategies for developing sustainable communities in higher education institutions. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 20596 (2023).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Caferra, R., Colasante, A., D’Adamo, I., Morone, A. & Morone, P. Interacting locally, acting globally: Trust and proximity in social networks for developing energy communities. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 16636 (2023).

Roseland, M. Sustainable community development: integrating environmental, economic, and social objectives. Prog. Plan. 54 (2), 73–132 (2000).

Shepherd, D. A. & Patzelt, H. The new field of sustainable entrepreneurship: Studying entrepreneurial action linking “what is to be sustained” with “what is to be developed”. Entrep. Theory Pract. 35 (1), 137–163 (2011).

Nosratabadi, S. et al. Sustainable business models: A review. Sustainability 11 (6), 1663 (2019).

Kandachar, P. & Halme, M. (eds) Sustainability Challenges and Solutions at the Pyramid’s base: Business, Technology and the Poor (Routledge, 2017).

Google Scholar

Setiawan, R. et al. IoT-based virtual E-learning system for sustainable development of smart cities. J. Grid Comput. 20 (3), 24 (2022).

Kotla, B. & Bosman, L. Redefining sustainability and entrepreneurship teaching. Trends High. Educ. 2 (3), 498–513 (2023).

Klapper, R. G. & Fayolle, A. A transformational learning framework for sustainable entrepreneurship education: The power of Paulo Freire’s educational model. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 21 (1), 100729 (2023).

Fanea-Ivanovici, M. & Baber, H. Sustainability at universities as a determinant of entrepreneurship for sustainability. Sustainability 14 (1), 454 (2022).

Del Vecchio, P., Secundo, G., Mele, G. & Passiante, G. Sustainable entrepreneurship education for circular economy: Emerging perspectives in Europe. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 27 (8), 2096–2124 (2021).

Nabi, G., Liñán, F., Fayolle, A., Krueger, N. & Walmsley, A. The impact of entrepreneurship education in higher education: A systematic review and research agenda. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 16 (2), 277–299 (2017).

Omotosho, A. O., Akintolu, M., Kimweli, K. M. & Modise, M. Assessing the enactus global sustainability initiative’s alignment with United Nations sustainable development goals: Lessons for higher education institutions. Educ. Sci. 13 (9), 935 (2023).

Shahid, S. M. & Alarifi, G. Social entrepreneurship education: A conceptual framework and review. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 19 (3), 100533 (2021).

Ndou, V., Secundo, G., Schiuma, G. & Passiante, G. Insights for shaping entrepreneurship education: Evidence from the European entrepreneurship centers. Sustainability 10 (11), 4323 (2018).

Fenton, M. & Barry, A. Breathing space–graduate entrepreneurs’ perspectives of entrepreneurship education in higher education. Education+ Train. 56 (8/9), 733–744 (2014).

Desplaces, D. E., Wergeles, F. & McGuigan, P. Economic gardening through entrepreneurship education: A service-learning approach. Ind. High. Educ. 23 (6), 473–484 (2009).

Owusu-Mintah, S. B. Entrepreneurship education and job creation for tourism graduates in Ghana. Education+ Train. 56 (8/9), 826–838 (2014).

Johansen, V. & Schanke, T. Entrepreneurship education in secondary education and training. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 57 (4), 357–368 (2013).

Zilincikova, M. & Stofkova, Z. Entrepreneurship education as a competitiveness support in the conditions of globalisation. In INTED2021 Proceedings 7833–7840 (IATED, 2021).

Pittaway, L. & Cope, J. Entrepreneurship education: A systematic review of the evidence. Int. Small Bus. J. 25 (5), 479–510 (2007).

Katz, J. A. The chronology and intellectual trajectory of American entrepreneurship education: 1876–1999. J. Bus. Ventur. 18 (2), 283–300 (2003).

Breznitz, S. M. & Zhang, Q. Entrepreneurship education and firm creation. Reg. Stud. 56 (6), 940–955 (2022).

Tashakkori, A. & Teddlie, C. Introduction to a mixed method and mixed model studies in the social and behavioral sciences. In The Mixed Methods Reader (eds Clark, V. L. P. & Creswell, J. W.) 5–6 (SAGE, 2008).

Robson, C. Real World Research (Blackwell, 2002).

Mahajan, R., Agrawal, R., Sharma, V. & Nangia, V. Analysis of challenges for management education in India using total interpretive structural modelling. Qual. Assur. Educ. 24 (1), 95–122 (2016).

Mathivathanan, D., Mathiyazhagan, K., Rana, N. P., Khorana, S. & Dwivedi, Y. K. Barriers to the adoption of blockchain technology in business supply chains: A total interpretive structural modelling (TISM) approach. Int. J. Prod. Res. 59 , 3338–3359 (2021).

Jena, J., Sidharth, S., Thakur, L. S., Pathak, D. K. & Pandey, V. C. Total interpretive structural modeling (TISM): Approach and application. J. Adv. Manag. Res. 14 (2), 162–181 (2017).

Davis, M. Teaching Design: A Guide to Curriculum and Pedagogy for College Design Faculty and Teachers Who use Design in Their Classrooms (Simon and Schuster, 2017).

Montgomery, B. L., Dodson, J. E. & Johnson, S. M. Guiding the way: Mentoring graduate students and junior faculty for sustainable academic careers. Sage Open 4 (4), 2158244014558043 (2014).

Malhotra, R., Massoudi, M. & Jindal, R. An alumni-based collaborative model to strengthen academia and industry partnership: The current challenges and strengths. Educ. Inf. Technol. 28 (2), 2263–2289 (2023).

Ahsan, M., Zheng, C., DeNoble, A. & Musteen, M. From student to entrepreneur: How mentorships and affect influence student venture launch. J. Small Bus. Manag. 56 (1), 76–102 (2018).

Surana, K., Singh, A. & Sagar, A. D. Strengthening science, technology, and innovation-based incubators to help achieve Sustainable Development Goals: Lessons from India. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 157 , 120057 (2020).

Menon, S. & Suresh, M. Synergizing education, research, campus operations, and community engagements towards sustainability in higher education: A literature review. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 21 (5), 1015–1051 (2020).

Thomson, A. M., Smith-Tolken, A. R., Naidoo, A. V. & Bringle, R. G. Service learning and community engagement: A comparison of three national contexts. VOLUNTAS Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 22 , 214–237 (2011).

Dharamsi, S. et al. Nurturing social responsibility through community service-learning: Lessons learned from a pilot project. Med. Teach. 32 (11), 905–911 (2010).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bliemel, M., Flores, R., De Klerk, S. & Miles, M. P. Accelerators as start-up infrastructure for entrepreneurial clusters. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 31 (1–2), 133–149 (2019).

Madaleno, M., Nathan, M., Overman, H. & Waights, S. Incubators, accelerators and urban economic development. Urban Stud. 59 (2), 281–300 (2022).

Jones, O., Meckel, P. & Taylor, D. Situated learning in a business incubator: Encouraging students to become real entrepreneurs. Ind. High. Educ. 35 (4), 367–383 (2021).

Ye, Q., Zhou, R., Anwar, M. A., Siddiquei, A. N. & Asmi, F. Entrepreneurs and environmental sustainability in the digital era: Regional and institutional perspectives. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17 (4), 1355 (2020).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bindra, S., Sharma, D., Achhnani, B., Mishra, H. G. & Ongsakul, V. Critical factors for knowledge management implementation: A TISM validation. J. Int. Bus. Entrep. Dev. 14 (1), 125–144 (2022).

Chillayil, J., Suresh, M., Viswanathan, P. K. & Kottayil, S. K. Is imperfect evaluation a deterrent to adopting energy audit recommendations?. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-05-2020-0236 (2021).

Sreenivasan, A. & Suresh, M. Modeling the enablers of sourcing risks faced by startups in the COVID-19 era. J. Glob. Oper. Strateg. Sourc. https://doi.org/10.1108/JGOSS-12-2020-0070 (2021).

Kioupi, V. & Voulvoulis, N. Education for sustainable development: A systemic framework for connecting the SDGs to educational outcomes. Sustainability 11 (21), 6104 (2019).

UNESCO. Education for sustainable development, https://www.unesco.org/en/sustainable-development/education , (February 06, 2024), Retrieved on February 23, 2024.

de Jesus Pacheco, D. A., ten Caten, C. S., Jung, C. F., Pergher, I. & Hunt, J. D. Triple bottom line impacts of traditional product-service systems models: Myth or truth? A natural language understanding approach. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 96 , 106819 (2022).

Mitchell, I. K. & Walinga, J. The creative imperative: The role of creativity, creative problem solving and insight as critical drivers for sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 140 , 1872–1884 (2017).

Download references

Acknowledgements

The research is funded by the Researchers Supporting Program at King Saud University. The authors present their appreciation to King Saud University for funding the publication of this research through the Researchers Supporting Program (RSPD2024R809), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

The research is funded by the Researchers Supporting Program at King Saud University (RSPD2024R809).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Computer Science and Engineering, Vellore Institute of Technology, Chennai, 600127, India

M. Suguna & Malathi Devarajan

Amrita School of Business, Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham, Coimbatore, 641112, India

Aswathy Sreenivasan & M. Suresh

Centre for Advanced Data Science, Vellore Institute of Technology, Chennai, 600127, India

Logesh Ravi

School of Electronics Engineering, Vellore Institute of Technology, Chennai, 600127, India

Department of Computer Engineering, College of Computer and Information Sciences, King Saud University, P.O. Box 51178, 11543, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Abdulaziz S. Almazyad

Guizhou Key Laboratory of Intelligent Technology in Power System, College of Electrical Engineering, Guizhou University, Guiyang, 550025, China

Guojiang Xiong

Department of Statistics and Operations Research, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, 202002, India

Operations Research Department, Faculty of Graduate Studies for Statistical Research, Cairo University, Giza, 12613, Egypt

Ali Wagdy Mohamed

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Conceptualization—S.M., A.S., Su.M.; Methodology—L.R., M.D., Su.M., I.A., A.W.M.; Software—M.D., A.S.M., G.X., I.A.; Validation—S.M., A.S.M., G.X., I.A.; Formal Analysis—L.R., M.D., Su.M.; Investigation—S.M., A.S., L.R., Su.M.; Resources—A.S.M., G.X., I.A.; Data Curation—M.D., A.S., Su.M.; Writing – Original Draft—S.M., A.S., Su.M.; Writing – Review & Editing—L.R., M.D., A.S.M., G.X., I.A., A.W.M.; Visualization—S.M., A.S.M., G.X., I.A.; Supervision—L.R., Su.M., A.W.M.; Project Administration—L.R., M.D., A.W.M.; Funding Acquisition—A.S.M., A.W.M.; All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ali Wagdy Mohamed .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Suguna, M., Sreenivasan, A., Ravi, L. et al. Entrepreneurial education and its role in fostering sustainable communities. Sci Rep 14 , 7588 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-57470-8

Download citation

Received : 08 December 2023

Accepted : 18 March 2024

Published : 30 March 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-57470-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Entrepreneurship education

- Sustainable communities

- Sustainable development goals

- Diverse community development

- Total interpretive structural modeling

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

How to Inspire Entrepreneurial Thinking in Your Students

Explore more.

- Course Design

- Experiential Learning

- Perspectives

- Student Engagement

T he world is in flux. The COVID-19 pandemic has touched every corner of the globe, profoundly impacting our economies and societies as well as our personal lives and social networks. Innovation is happening at record speed. Digital technologies have transformed the way we live and work.

At the same time, world leaders are collaborating to tackle the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals , which aim to address issues related to health, education, gender equality, energy, and more. Private sector leaders, too, are recognizing that it makes good business sense to be aware of corporations’ social and environmental impact.

So, how can we as educators prepare our students to succeed in this tumultuous and uncertain—yet hopeful and exhilarating—global environment? As the world changes, so do the skills students need to build their careers—and to build a better society. For students to acquire these evolving skills, we believe educators must help students develop an entrepreneurial mindset.

6 Ways You Can Inspire Entrepreneurial Thinking Among Your Students

An entrepreneurial mindset —attitudes and behaviors that encapsulate how entrepreneurs tend to think and act—enables one to identify and capitalize on opportunities, change course when needed, and view mistakes as an opportunity to learn and improve.

If a student decides to become an entrepreneur, an entrepreneurial mindset is essential. And for students who plan to join a company, nonprofit, or government agency, this mindset will enable them to become intrapreneurs —champions of innovation and creativity inside their organizations. It can also help in everyday life by minimizing the impact of failure and reframing setbacks as learning opportunities.

“As the world changes, so do the skills students need to build their careers—and to build a better society.”

Effective entrepreneurship professors are skilled at nurturing the entrepreneurial mindset. They, of course, have the advantage of teaching a subject that naturally demands students think in this way. However, as we will explore, much of what they do in their classroom is transferable to other subject areas.

We interviewed top entrepreneurship professors at leading global institutions to understand the pedagogical approaches they use to cultivate this mindset in their students. Here, we will delve into six such approaches. As we do, think about what aspects of their techniques you can adopt to inspire entrepreneurial thinking in your own classroom.

1. Encourage Students to Chart Their Own Course Through Project-Based Learning

According to Ayman Ismail, associate professor of entrepreneurship at the American University in Cairo, students are used to pre-packaged ideas and linear thinking. “Students are often told, ‘Here’s X, Y, Z, now do something with it.’ They are not used to exploring or thinking creatively,” says Ismail.

To challenge this linear pattern, educators can instead help their students develop an entrepreneurial mindset through team-based projects that can challenge them to identify a problem or job to be done, conduct market research, and create a new product or service that addresses the issue. There is no blueprint for students to follow in developing these projects, so many will find this lack of direction confusing—in some cases even frightening. But therein lies the learning.

John Danner, who teaches entrepreneurship at Princeton University and University of California, Berkeley, finds his students similarly inhibited at the start. “My students come in trying to understand the rules of the game,” he says. “I tell them the game is to be created by you.”

Danner encourages students to get comfortable navigating life’s maze of ambiguity and possibility and to let their personal initiative drive them forward. He tells them, “At best you have a flashlight when peering into ambiguity. You can shine light on the next few steps.”

In your classroom: Send students on an unstructured journey. Dive right in by asking them to identify a challenge that will hone their problem-finding skills and encourage them to work in teams to find a solution. Do not give them a blueprint.

For example, in our M²GATE virtual exchange program, we teamed US students with peers located in four countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. We asked them to identify a pressing social issue in MENA and then create a product or service to address it. One of the teams identified the high rate of youth unemployment in Morocco as an issue. They discovered that employers want workers with soft skills, but few schools provide such training. Their solution was a low-cost after-school program to equip students ages 8-16 with soft skills.

2. Help Students Think Broadly and Unleash Their Creativity

Professor Heidi Neck says her students at Babson College struggle with problem finding at the start of the entrepreneurial journey. “They are good at solving problems, but not as good at finding the problem to solve,” she explains. “For example, they know that climate change is a problem, and they’re interested in doing something about it, but they’re not sure what problem within that broad area they can focus on and find a market for.”

Professor Niko Slavnic, who teaches entrepreneurship at IEDC-Bled School of Management in Slovenia and the ESSCA School of Management in France, says he first invests time in teaching his students to unlearn traditional ways of thinking and unleash their creativity. He encourages students to get outside their comfort zones. One way he does this is by having them make paper airplanes and then stand on their desks and throw them. Many ask, “Should we do this? Is this allowed?” When his students start to question the rules and think about new possibilities, this indicates to Slavnic that they are primed for the type of creative exploration his course demands.

“When students start to question the rules and think about new possibilities, this indicates to Professor Niko Slavnic that they are primed for the type of creative exploration his course demands.”

In your classroom: Think about the concept of “unlearning.” Ask yourself if students are entering your class with rigid mindsets or attitudes based on rules and structures that you would like to change. For example, they may be coming into your classroom with the expectation that you, the instructor, have all the answers and that you will impart your wisdom to them throughout the semester. Design your course so that students spend more time than you do presenting, with you acting more as an advisor (the “guide on the side”).

3. Prompt Students to Take Bold Actions

Geoff Archer, an entrepreneurship professor at Royal Roads University in Canada, says Kolb’s theory of experiential learning underpins the entrepreneurial management curriculum he designed. Archer takes what he calls a “ready-fire-aim approach,” common in the startup world—he throws students right into the deep end. They are tasked with creating a for-profit business from scratch and operating it for a month. At the end of the semester, they must come up with a “pitch deck”—a short presentation providing potential investors with an overview of their proposed new business—and an investor-ready business plan.

This approach can be met with resistance, especially with mature learners. “They’re used to winning, and it’s frustrating and more than a bit terrifying to be told to do something without being given more structure upfront,” says Archer.

Professor Rita Egizii, who co-teaches with Archer, says students really struggled when instructed to get out and talk with potential customers about a product they were proposing to launch as part of their class project. “They all sat outside on the curb on their laptops. For them, it’s not normal and not okay to make small experiments and fail,” says Egizii.

Keep in mind that, culturally, the taboo of failure—even on a very small scale and even in the name of learning—can be ingrained in the minds of students from around the world.