- Make an Appointment

- Study Connect

- Request Workshop

How to read and understand a scientific paper

How to read and understand a scientific paper: a guide for non-scientists, london school of economics and political science, jennifer raff.

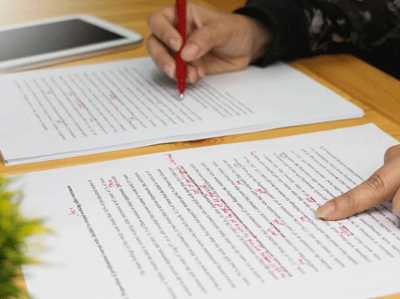

From vaccinations to climate change, getting science wrong has very real consequences. But journal articles, a primary way science is communicated in academia, are a different format to newspaper articles or blogs and require a level of skill and undoubtedly a greater amount of patience. Here Jennifer Raff has prepared a helpful guide for non-scientists on how to read a scientific paper. These steps and tips will be useful to anyone interested in the presentation of scientific findings and raise important points for scientists to consider with their own writing practice.

My post, The truth about vaccinations: Your physician knows more than the University of Google sparked a very lively discussion, with comments from several people trying to persuade me (and the other readers) that their paper disproved everything that I’d been saying. While I encourage you to go read the comments and contribute your own, here I want to focus on the much larger issue that this debate raised: what constitutes scientific authority?

It’s not just a fun academic problem. Getting the science wrong has very real consequences. For example, when a community doesn’t vaccinate children because they’re afraid of “toxins” and think that prayer (or diet, exercise, and “clean living”) is enough to prevent infection, outbreaks happen.

“Be skeptical. But when you get proof, accept proof.” –Michael Specter

What constitutes enough proof? Obviously everyone has a different answer to that question. But to form a truly educated opinion on a scientific subject, you need to become familiar with current research in that field. And to do that, you have to read the “primary research literature” (often just called “the literature”). You might have tried to read scientific papers before and been frustrated by the dense, stilted writing and the unfamiliar jargon. I remember feeling this way! Reading and understanding research papers is a skill which every single doctor and scientist has had to learn during graduate school. You can learn it too, but like any skill it takes patience and practice.

I want to help people become more scientifically literate, so I wrote this guide for how a layperson can approach reading and understanding a scientific research paper. It’s appropriate for someone who has no background whatsoever in science or medicine, and based on the assumption that he or she is doing this for the purpose of getting a basic understanding of a paper and deciding whether or not it’s a reputable study.

The type of scientific paper I’m discussing here is referred to as a primary research article . It’s a peer-reviewed report of new research on a specific question (or questions). Another useful type of publication is a review article . Review articles are also peer-reviewed, and don’t present new information, but summarize multiple primary research articles, to give a sense of the consensus, debates, and unanswered questions within a field. (I’m not going to say much more about them here, but be cautious about which review articles you read. Remember that they are only a snapshot of the research at the time they are published. A review article on, say, genome-wide association studies from 2001 is not going to be very informative in 2013. So much research has been done in the intervening years that the field has changed considerably).

Before you begin: some general advice

Reading a scientific paper is a completely different process than reading an article about science in a blog or newspaper. Not only do you read the sections in a different order than they’re presented, but you also have to take notes, read it multiple times, and probably go look up other papers for some of the details. Reading a single paper may take you a very long time at first. Be patient with yourself. The process will go much faster as you gain experience.

Most primary research papers will be divided into the following sections: Abstract, Introduction, Methods, Results, and Conclusions/Interpretations/Discussion. The order will depend on which journal it’s published in. Some journals have additional files (called Supplementary Online Information) which contain important details of the research, but are published online instead of in the article itself (make sure you don’t skip these files).

Before you begin reading, take note of the authors and their institutional affiliations. Some institutions (e.g. University of Texas) are well-respected; others (e.g. the Discovery Institute ) may appear to be legitimate research institutions but are actually agenda-driven. Tip: g oogle “Discovery Institute” to see why you don’t want to use it as a scientific authority on evolutionary theory.

Also take note of the journal in which it’s published. Reputable (biomedical) journals will be indexed by Pubmed . [EDIT: Several people have reminded me that non-biomedical journals won’t be on Pubmed, and they’re absolutely correct! (thanks for catching that, I apologize for being sloppy here). Check out Web of Science for a more complete index of science journals. And please feel free to share other resources in the comments!] Beware of questionable journals .

As you read, write down every single word that you don’t understand. You’re going to have to look them all up (yes, every one. I know it’s a total pain. But you won’t understand the paper if you don’t understand the vocabulary. Scientific words have extremely precise meanings).

Step-by-step instructions for reading a primary research article

1. Begin by reading the introduction, not the abstract.

The abstract is that dense first paragraph at the very beginning of a paper. In fact, that’s often the only part of a paper that many non-scientists read when they’re trying to build a scientific argument. (This is a terrible practice—don’t do it.). When I’m choosing papers to read, I decide what’s relevant to my interests based on a combination of the title and abstract. But when I’ve got a collection of papers assembled for deep reading, I always read the abstract last. I do this because abstracts contain a succinct summary of the entire paper, and I’m concerned about inadvertently becoming biased by the authors’ interpretation of the results.

2. Identify the BIG QUESTION.

Not “What is this paper about”, but “What problem is this entire field trying to solve?”

This helps you focus on why this research is being done. Look closely for evidence of agenda-motivated research.

3. Summarize the background in five sentences or less.

Here are some questions to guide you:

What work has been done before in this field to answer the BIG QUESTION? What are the limitations of that work? What, according to the authors, needs to be done next?

The five sentences part is a little arbitrary, but it forces you to be concise and really think about the context of this research. You need to be able to explain why this research has been done in order to understand it.

4. Identify the SPECIFIC QUESTION(S)

What exactly are the authors trying to answer with their research? There may be multiple questions, or just one. Write them down. If it’s the kind of research that tests one or more null hypotheses, identify it/them.

Not sure what a null hypothesis is? Go read this one and try to identify the null hypotheses in it. Keep in mind that not every paper will test a null hypothesis.

5. Identify the approach

What are the authors going to do to answer the SPECIFIC QUESTION(S)?

6. Now read the methods section. Draw a diagram for each experiment, showing exactly what the authors did.

I mean literally draw it. Include as much detail as you need to fully understand the work. As an example, here is what I drew to sort out the methods for a paper I read today ( Battaglia et al. 2013: “The first peopling of South America: New evidence from Y-chromosome haplogroup Q” ). This is much less detail than you’d probably need, because it’s a paper in my specialty and I use these methods all the time. But if you were reading this, and didn’t happen to know what “process data with reduced-median method using Network” means, you’d need to look that up.

Image credit: author

You don’t need to understand the methods in enough detail to replicate the experiment—that’s something reviewers have to do—but you’re not ready to move on to the results until you can explain the basics of the methods to someone else.

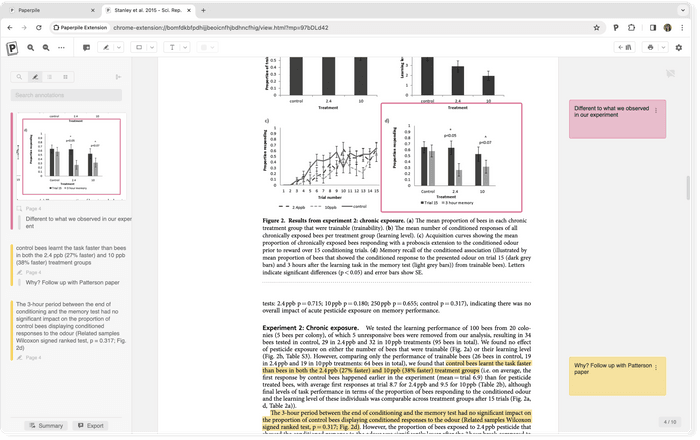

7. Read the results section. Write one or more paragraphs to summarize the results for each experiment, each figure, and each table. Don’t yet try to decide what the results mean , just write down what they are.

You’ll find that, particularly in good papers, the majority of the results are summarized in the figures and tables. Pay careful attention to them! You may also need to go to the Supplementary Online Information file to find some of the results.

It is at this point where difficulties can arise if statistical tests are employed in the paper and you don’t have enough of a background to understand them. I can’t teach you stats in this post, but here , and here are some basic resources to help you. I STRONGLY advise you to become familiar with them.

Things to pay attention to in the results section:

- Any time the words “significant” or “non-significant” are used. These have precise statistical meanings. Read more about this here .

- If there are graphs, do they have error bars on them? For certain types of studies, a lack of confidence intervals is a major red flag.

- The sample size. Has the study been conducted on 10, or 10,000 people? (For some research purposes, a sample size of 10 is sufficient, but for most studies larger is better).

8. Do the results answer the SPECIFIC QUESTION(S)? What do you think they mean?

Don’t move on until you have thought about this. It’s okay to change your mind in light of the authors’ interpretation—in fact you probably will if you’re still a beginner at this kind of analysis—but it’s a really good habit to start forming your own interpretations before you read those of others.

9. Read the conclusion/discussion/Interpretation section.

What do the authors think the results mean? Do you agree with them? Can you come up with any alternative way of interpreting them? Do the authors identify any weaknesses in their own study? Do you see any that the authors missed? (Don’t assume they’re infallible!) What do they propose to do as a next step? Do you agree with that?

10. Now, go back to the beginning and read the abstract.

Does it match what the authors said in the paper? Does it fit with your interpretation of the paper?

11. FINAL STEP: (Don’t neglect doing this) What do other researchers say about this paper?

Who are the (acknowledged or self-proclaimed) experts in this particular field? Do they have criticisms of the study that you haven’t thought of, or do they generally support it?

Here’s a place where I do recommend you use google! But do it last, so you are better prepared to think critically about what other people say.

(12. This step may be optional for you, depending on why you’re reading a particular paper. But for me, it’s critical! I go through the “Literature cited” section to see what other papers the authors cited. This allows me to better identify the important papers in a particular field, see if the authors cited my own papers (KIDDING!….mostly), and find sources of useful ideas or techniques.)

UPDATE: If you would like to see an example of how to read a science paper using this framework, you can find one here .

I gratefully acknowledge Professors José Bonner and Bill Saxton for teaching me how to critically read and analyze scientific papers using this method. I’m honored to have the chance to pass along what they taught me.

I’ve written a shorter version of this guide for teachers to hand out to their classes. If you’d like a PDF, shoot me an email: jenniferraff (at) utexas (dot) edu. For further comments and additional questions on this guide, please see the Comments Section on the original post .

This piece originally appeared on the author’s personal blog and is reposted with permission.

Featured image credit: Scientists in a laboratory of the University of La Rioja by Urcomunicacion (Wikimedia CC BY3.0)

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the LSE Impact blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please review our Comments Policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Jennifer Raff (Indiana University—dual Ph.D. in genetics and bioanthropology) is an assistant professor in the Department of Anthropology, University of Kansas, director and Principal Investigator of the KU Laboratory of Human Population Genomics, and assistant director of KU’s Laboratory of Biological Anthropology. She is also a research affiliate with the University of Texas anthropological genetics laboratory. She is keenly interested in public outreach and scientific literacy, writing about topics in science and pseudoscience for her blog ( violentmetaphors.com ), the Huffington Post, and for the Social Evolution Forum .

- Learning Consultations

- Peer Tutoring

- Getting Started

- Peer Education Courses

- Become a Peer Educator

- ADHD/LD Support

- Workshops & Outreach

- Learning Strategies

- Manage Time

- All Resources

- For Faculty & Staff

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to read a scientific paper: a step-by-step guide

Scientific paper format

How to read a scientific paper in 3 steps, step 1: identify your motivations for reading a scientific paper, step 2: use selective reading to gain a high-level understanding of the scientific paper, step 3: read straight through to achieve a deep understanding of a scientific paper, frequently asked questions about reading a scientific paper efficiently, related articles.

A scientific paper is a complex document. Scientific papers are divided into multiple sections and frequently contain jargon and long sentences that make reading difficult. The process of reading a scientific paper to obtain information can often feel overwhelming for an early career researcher.

But the good news is that you can acquire the skill of efficiently reading a scientific paper, and you can learn how to painlessly obtain the information you need.

In this guide, we show you how to read a scientific paper step-by-step. You will learn:

- The scientific paper format

- How to identify your reasons for reading a scientific paper

- How to skim a paper

- How to achieve a deep understanding of a paper.

Using these steps for reading a scientific paper will help you:

- Obtain information efficiently

- Retain knowledge more effectively

- Allocate sufficient time to your reading task.

The steps below are the result of research into how scientists read scientific papers and our own experiences as scientists.

Firstly, how is a scientific paper structured?

The main sections are Abstract, Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion. In the table below, we describe the purpose of each component of a scientific paper.

Because the structured format of a scientific paper makes it easy to find the information you need, a common technique for reading a scientific paper is to cherry-pick sections and jump around the paper.

In a YouTube video, Dr. Amina Yonis shows this nonlinear practice for reading a scientific paper. She justifies her technique by stating that “By reading research papers like this, you are enabling yourself to have a disciplined approach, and it prevents yourself from drowning in the details before you even get a bird’s-eye view”.

Selective reading is a skill that can help you read faster and engage with the material presented. In his article on active vs. passive reading of scientific papers, cell biologist Tung-Tien Sun defines active reading as "reading with questions in mind" , searching for the answers, and focusing on the parts of the paper that answer your questions.

Therefore, reading a scientific paper from start to finish isn't always necessary to understand it. How you read the paper depends on what you need to learn. For example, oceanographer Ken Hughes suggests that you may read a scientific paper to gain awareness of a theory or field, or you may read to actively solve a problem in your research.

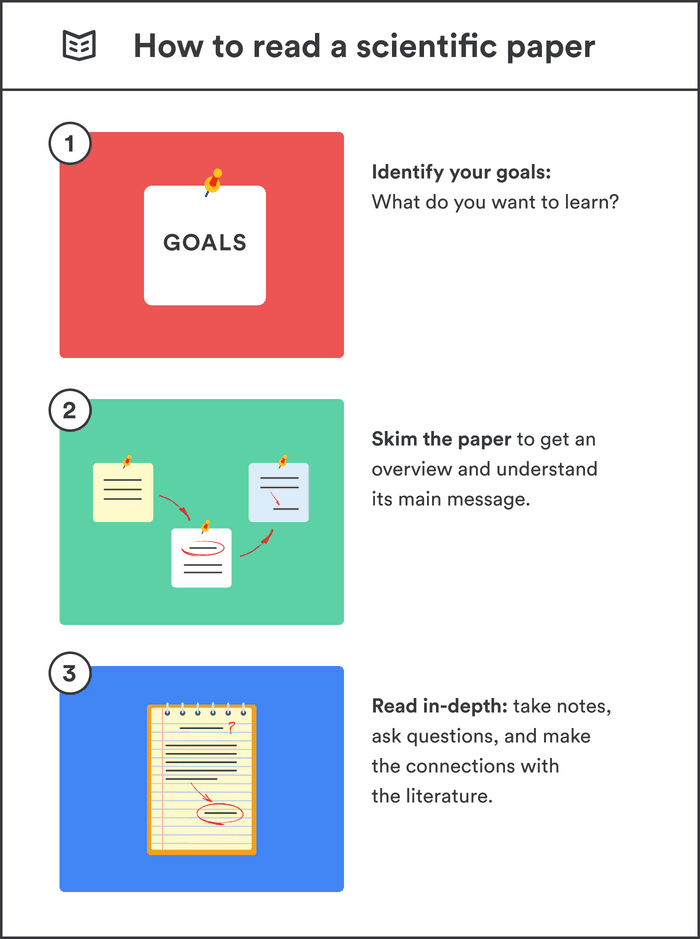

To successfully read a scientific paper, we advise using three strategies:

- Identify your motivations for reading a scientific paper

- Use selective reading to gain a high-level understanding of the scientific paper

- Read straight through to achieve a deep understanding of a scientific paper .

All 3 steps require you to think critically and have questions in mind.

Before you sit down to read a scientific paper, ask yourself these three questions:

- Why do I need to read this paper?

- What information am I looking for?

- Where in the paper am I most likely to find the information I need?

Is it background reading or a literature review for a research project you are currently working on? Are you getting into a new field of research? Do you wish to compare your results with the ones presented in the paper? Are you following an author’s work, and need to keep up-to-date on their current research? Are you keeping tabs on emerging methods in your field?

All of these intentions require a different reading approach.

For example, if you're delving into a new field of research, you'll want to read the introduction to gather background information and seminal references. The discussion section will also be important to understand the broader context of the findings.

If you aim to extend the work presented in a paper, and this study will be the starting point for your work, it's crucial to read the paper deeply.

If your focus is on the study design and techniques used by the authors, you'll spend most of your time reading and understanding the methods section.

Sometimes you'll need to read a paper to discuss it in your own research. This may be to compare or contrast your work with the paper's content, or to stimulate a discussion on future applications of your work.

If you are following an author’s work, a quick skim might suffice to understand how the paper fits into their overall research program.

Tip: Knowing why you want to read the paper facilitates how you will read the paper. Depending on your needs, your approach may take the form of a surface-level reading or a deep and thorough reading.

Knowing your motivations will guide your navigation through the paper because you have already identified which sections are most likely to contain the information you need. Approaching reading a paper in this way saves you time and makes the task less daunting.

➡️ Learn more about how to write a literature review

Begin by gaining an overview of the paper by following these simple steps:

- Read the title. What type of paper is it? Is it a journal article, a review, a methods paper, or a commentary?

- Read the abstract . The abstract is a summary of the study. What is the study about? What question was addressed? What methods were used? What did the authors find, and what are the key findings? What do the authors think are the implications of the work? Reading the abstract immediately tells you whether you should invest the time to read the paper fully.

- Look at the headings and subheadings, which describe the sections and subsections of the paper. The headings and subheadings outline the story of the paper.

- Skim the introduction. An introduction has a clear structure. The first paragraph is background information on the topic. If you are new to the field, you will read this closely, whereas an expert in that field will skim this section. The second component defines the gap in knowledge that the paper aims to address. What is unknown, and what research is needed? What problem needs to be solved? Here, you should find the questions that will be addressed by the study, and the goal of the research. The final paragraph summarizes how the authors address their research question, for example, what hypothesis will be tested, and what predictions the authors make. As you read, make a note of key references. By the end of the introduction, you should understand the goal of the research.

- Go to the results section, and study the figures and tables. These are the data—the meat of the study. Try to comprehend the data before reading the captions. After studying the data, read the captions. Do not expect to understand everything immediately. Remember, this is the result of many years of work. Make a note of what you do not understand. In your second reading, you will read more deeply.

- Skim the discussion. There are three components. The first part of the discussion summarizes what the authors have found, and what they think the implications of the work are. The second part discusses some (usually not all!) limitations of the study, and the final part is a concluding statement.

- Glance at the methods. Get a brief overview of the techniques used in the study. Depending on your reading goals, you may spend a lot of time on this section in subsequent readings, or a cursory reading may be sufficient.

- Summarize what the paper is about—its key take-home message—in a sentence or two. Ask yourself if you have got the information you need.

- List any terminology you may need to look up before reading the paper again.

- Scan the reference list. Make a note of papers you may need to read for background information before delving further into the paper.

Congratulations, you have completed the first reading! You now have gained a high-level perspective of the study, which will be enough for many research purposes.

Now that you have an overview of the work and you have identified what information you want to obtain, you are ready to understand the paper on a deeper level. Deep understanding is achieved in the second and subsequent readings with note-taking and active reflection. Here is a step-by-step guide.

- Active engagement with the material

- Critical thinking

- Creative thinking

- Synthesis of information

- Consolidation of information into memory.

Highlighting sentences helps you quickly scan the paper and be reminded of the key points, which is helpful when you return to the paper later.

Notes may include ideas, connections to other work, questions, comments, and references to follow up on.

There are many ways for taking notes on a paper. You can:

- Print out the paper, and write your notes in the margins.

- Annotate the paper PDF from your desktop computer, or mobile device .

- Use personal knowledge management software, like Notion , Obsidian, or Evernote, for note-taking. Notes are easy to find in a structured database and can be linked to each other.

- Use reference management tools to take notes. Having your notes stored with the scientific papers you’ve read has the benefit of keeping all your ideas in one place. Some reference managers, like Paperpile, allow you to add notes to your papers, and highlight key sentences on PDFs .

Note-taking facilitates critical thinking and helps you evaluate the evidence that the authors present. Ask yourself questions like:

- What new contribution has the study made to the literature?

- How have the authors interpreted the results? (Remember, the authors have thought about their results more deeply than anybody else.)

- What do I think the results mean?

- Are the findings well-supported?

- What factors might have affected the results, and have the authors addressed them?

- Are there alternative explanations for the results?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the study?

- What are the broader implications of the study?

- What should be done next?

Note-taking also encourages creative thinking . Ask yourself questions like:

- What new ideas have arisen from reading the paper?

- How does it connect with your work?

- What connections to other papers can you make?

- Write a summary of the paper in your own words. This is your attempt to integrate the new knowledge you have gained with what you already know from other sources and to consolidate that information into memory. You may find that you have to go back and re-read some sections to confirm some of the details.

- Discuss the paper with others. You may find that even at this stage, there are still aspects of the paper that you are striving to understand. It is now a good time to reach out to others—peers in your program, your advisor, or even on social media. In their 10 simple rules for reading a scientific paper , Maureen Carey and coauthors suggest that participating in journal clubs, where you meet with peers to discuss interesting or important scientific papers, is a great way to clarify your understanding.

- A scientific paper can be read over many days. According to research presented in the book " Make it Stick: The Science of Successful Learning " by writer Peter Brown and psychology professors Henry Roediger and Mark McDaniel, "spaced practice" is more effective for retaining information than focusing on a single skill or subject until it is mastered. This involves breaking up learning into separate periods of training or studying. Applying this research to reading a scientific paper suggests that spacing out your reading by breaking the work into separate reading sessions can help you better commit the information in a paper to memory.

A dense journal article may need many readings to be understood fully. It is useful to remember that many scientific papers result from years of hard work, and the expectation of achieving a thorough understanding in one sitting must be modified accordingly. But, the process of reading a scientific paper will get easier and faster with experience.

The best way to read a scientific paper depends on your needs. Before reading the paper, identify your motivations for reading a scientific paper, and pinpoint the information you need. This will help you decide between skimming the paper and reading the paper more thoroughly.

Don’t read the paper from beginning to end. Instead, be aware of the scientific paper format. Take note of the information you need before starting to read the paper. Then skim the paper, jumping to the appropriate sections in the paper, to get the information you require.

It varies. Skimming a scientific paper may take anywhere between 15 minutes to one hour. Reading a scientific paper to obtain a deep understanding may take anywhere between 1 and 6 hours. It is not uncommon to have to read a dense paper in chunks over numerous days.

First, read the introduction to understand the main thesis and findings of the paper. Pay attention to the last paragraph of the introduction, where you can find a high-level summary of the methods and results. Next, skim the paper by jumping to the results and discussion. Then carefully read the paper from start to finish, taking notes as you read. You will need more than one reading to fully understand a dense research paper.

To read a scientific paper critically, be an active reader. Take notes, highlight important sentences, and write down questions as you read. Study the data. Take care to evaluate the evidence presented in the paper.

- About the LSE Impact Blog

- Comments Policy

- Popular Posts

- Recent Posts

- Subscribe to the Impact Blog

- Write for us

- LSE comment

May 9th, 2016

How to read and understand a scientific paper: a guide for non-scientists.

95 comments | 1998 shares

Estimated reading time: 7 minutes

Enjoying this blogpost? 📨 Sign up to our mailing list and receive all the latest LSE Impact Blog news direct to your inbox.

My post, The truth about vaccinations: Your physician knows more than the University of Google sparked a very lively discussion, with comments from several people trying to persuade me (and the other readers) that their paper disproved everything that I’d been saying. While I encourage you to go read the comments and contribute your own, here I want to focus on the much larger issue that this debate raised: what constitutes scientific authority?

It’s not just a fun academic problem. Getting the science wrong has very real consequences. For example, when a community doesn’t vaccinate children because they’re afraid of “toxins” and think that prayer (or diet, exercise, and “clean living”) is enough to prevent infection, outbreaks happen .

“Be skeptical. But when you get proof, accept proof.” –Michael Specter

What constitutes enough proof? Obviously everyone has a different answer to that question. But to form a truly educated opinion on a scientific subject, you need to become familiar with current research in that field. And to do that, you have to read the “primary research literature” (often just called “the literature”). You might have tried to read scientific papers before and been frustrated by the dense, stilted writing and the unfamiliar jargon. I remember feeling this way! Reading and understanding research papers is a skill which every single doctor and scientist has had to learn during graduate school. You can learn it too, but like any skill it takes patience and practice.

I want to help people become more scientifically literate, so I wrote this guide for how a layperson can approach reading and understanding a scientific research paper. It’s appropriate for someone who has no background whatsoever in science or medicine, and based on the assumption that he or she is doing this for the purpose of getting a basic understanding of a paper and deciding whether or not it’s a reputable study.

The type of scientific paper I’m discussing here is referred to as a primary research article . It’s a peer-reviewed report of new research on a specific question (or questions). Another useful type of publication is a review article . Review articles are also peer-reviewed, and don’t present new information, but summarize multiple primary research articles, to give a sense of the consensus, debates, and unanswered questions within a field. (I’m not going to say much more about them here, but be cautious about which review articles you read. Remember that they are only a snapshot of the research at the time they are published. A review article on, say, genome-wide association studies from 2001 is not going to be very informative in 2013. So much research has been done in the intervening years that the field has changed considerably).

Before you begin: some general advice

Reading a scientific paper is a completely different process than reading an article about science in a blog or newspaper. Not only do you read the sections in a different order than they’re presented, but you also have to take notes, read it multiple times, and probably go look up other papers for some of the details. Reading a single paper may take you a very long time at first. Be patient with yourself. The process will go much faster as you gain experience.

Most primary research papers will be divided into the following sections: Abstract, Introduction, Methods, Results, and Conclusions/Interpretations/Discussion. The order will depend on which journal it’s published in. Some journals have additional files (called Supplementary Online Information) which contain important details of the research, but are published online instead of in the article itself (make sure you don’t skip these files).

Before you begin reading, take note of the authors and their institutional affiliations. Some institutions (e.g. University of Texas) are well-respected; others (e.g. the Discovery Institute ) may appear to be legitimate research institutions but are actually agenda-driven. Tip: g oogle “Discovery Institute” to see why you don’t want to use it as a scientific authority on evolutionary theory.

Also take note of the journal in which it’s published. Reputable (biomedical) journals will be indexed by Pubmed . [EDIT: Several people have reminded me that non-biomedical journals won’t be on Pubmed, and they’re absolutely correct! (thanks for catching that, I apologize for being sloppy here). Check out Web of Science for a more complete index of science journals. And please feel free to share other resources in the comments!] Beware of questionable journals .

As you read, write down every single word that you don’t understand. You’re going to have to look them all up (yes, every one. I know it’s a total pain. But you won’t understand the paper if you don’t understand the vocabulary. Scientific words have extremely precise meanings).

Step-by-step instructions for reading a primary research article

1. Begin by reading the introduction, not the abstract.

The abstract is that dense first paragraph at the very beginning of a paper. In fact, that’s often the only part of a paper that many non-scientists read when they’re trying to build a scientific argument. (This is a terrible practice—don’t do it.). When I’m choosing papers to read, I decide what’s relevant to my interests based on a combination of the title and abstract. But when I’ve got a collection of papers assembled for deep reading, I always read the abstract last. I do this because abstracts contain a succinct summary of the entire paper, and I’m concerned about inadvertently becoming biased by the authors’ interpretation of the results.

2. Identify the BIG QUESTION.

Not “What is this paper about”, but “What problem is this entire field trying to solve?”

This helps you focus on why this research is being done. Look closely for evidence of agenda-motivated research.

3. Summarize the background in five sentences or less.

Here are some questions to guide you:

What work has been done before in this field to answer the BIG QUESTION? What are the limitations of that work? What, according to the authors, needs to be done next?

The five sentences part is a little arbitrary, but it forces you to be concise and really think about the context of this research. You need to be able to explain why this research has been done in order to understand it.

4. Identify the SPECIFIC QUESTION(S)

What exactly are the authors trying to answer with their research? There may be multiple questions, or just one. Write them down. If it’s the kind of research that tests one or more null hypotheses, identify it/them.

Not sure what a null hypothesis is? Go read this , then go back to my last post and read one of the papers that I linked to (like this one ) and try to identify the null hypotheses in it. Keep in mind that not every paper will test a null hypothesis.

5. Identify the approach

What are the authors going to do to answer the SPECIFIC QUESTION(S)?

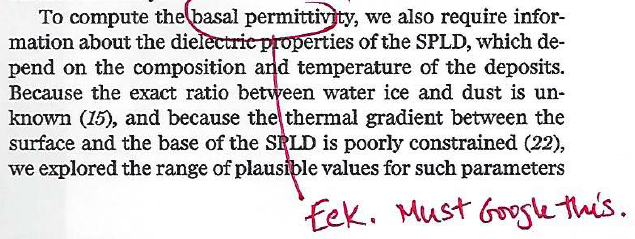

6. Now read the methods section. Draw a diagram for each experiment, showing exactly what the authors did.

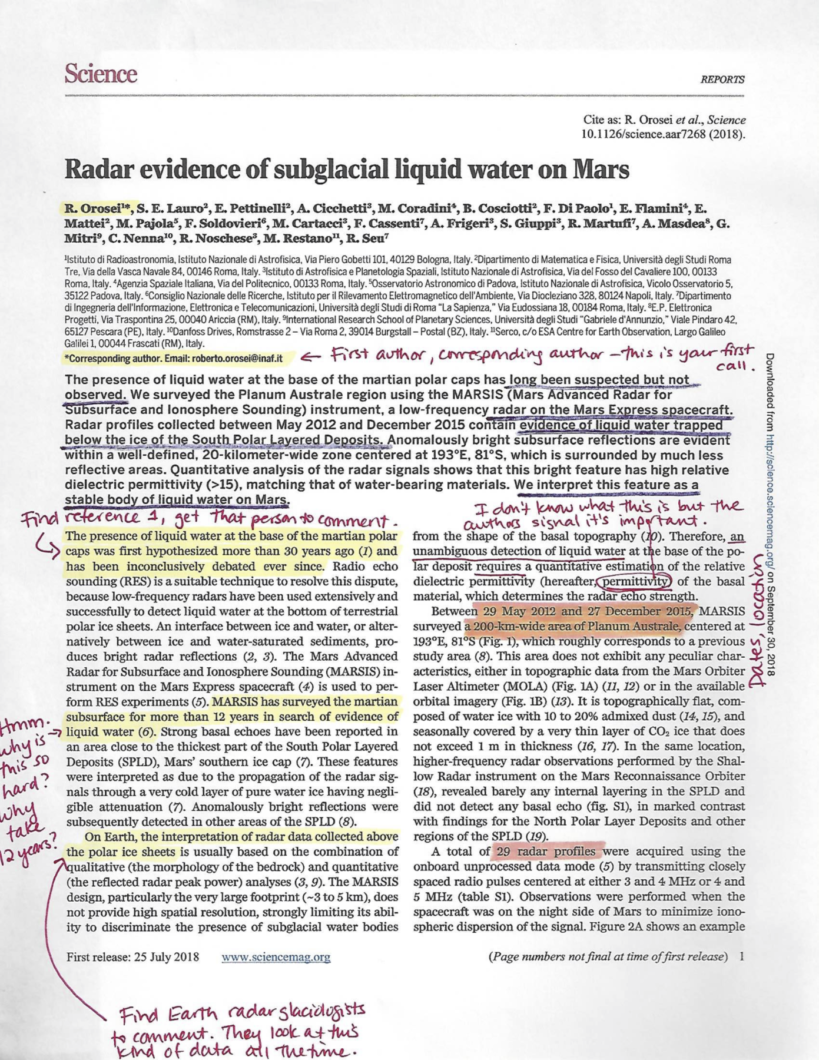

I mean literally draw it. Include as much detail as you need to fully understand the work. As an example, here is what I drew to sort out the methods for a paper I read today ( Battaglia et al. 2013: “The first peopling of South America: New evidence from Y-chromosome haplogroup Q” ). This is much less detail than you’d probably need, because it’s a paper in my specialty and I use these methods all the time. But if you were reading this, and didn’t happen to know what “process data with reduced-median method using Network” means, you’d need to look that up.

Image credit: author

You don’t need to understand the methods in enough detail to replicate the experiment—that’s something reviewers have to do—but you’re not ready to move on to the results until you can explain the basics of the methods to someone else.

7. Read the results section. Write one or more paragraphs to summarize the results for each experiment, each figure, and each table. Don’t yet try to decide what the results mean , just write down what they are.

You’ll find that, particularly in good papers, the majority of the results are summarized in the figures and tables. Pay careful attention to them! You may also need to go to the Supplementary Online Information file to find some of the results.

It is at this point where difficulties can arise if statistical tests are employed in the paper and you don’t have enough of a background to understand them. I can’t teach you stats in this post, but here , here , and here are some basic resources to help you. I STRONGLY advise you to become familiar with them.

Things to pay attention to in the results section:

- Any time the words “significant” or “non-significant” are used. These have precise statistical meanings. Read more about this here .

- If there are graphs, do they have error bars on them? For certain types of studies, a lack of confidence intervals is a major red flag.

- The sample size. Has the study been conducted on 10, or 10,000 people? (For some research purposes, a sample size of 10 is sufficient, but for most studies larger is better).

8. Do the results answer the SPECIFIC QUESTION(S)? What do you think they mean?

Don’t move on until you have thought about this. It’s okay to change your mind in light of the authors’ interpretation—in fact you probably will if you’re still a beginner at this kind of analysis—but it’s a really good habit to start forming your own interpretations before you read those of others.

9. Read the conclusion/discussion/Interpretation section.

What do the authors think the results mean? Do you agree with them? Can you come up with any alternative way of interpreting them? Do the authors identify any weaknesses in their own study? Do you see any that the authors missed? (Don’t assume they’re infallible!) What do they propose to do as a next step? Do you agree with that?

10. Now, go back to the beginning and read the abstract.

Does it match what the authors said in the paper? Does it fit with your interpretation of the paper?

11. FINAL STEP: (Don’t neglect doing this) What do other researchers say about this paper?

Who are the (acknowledged or self-proclaimed) experts in this particular field? Do they have criticisms of the study that you haven’t thought of, or do they generally support it?

Here’s a place where I do recommend you use google! But do it last, so you are better prepared to think critically about what other people say.

(12. This step may be optional for you, depending on why you’re reading a particular paper. But for me, it’s critical! I go through the “Literature cited” section to see what other papers the authors cited. This allows me to better identify the important papers in a particular field, see if the authors cited my own papers (KIDDING!….mostly), and find sources of useful ideas or techniques.)

UPDATE: If you would like to see an example of how to read a science paper using this framework, you can find one here .

I gratefully acknowledge Professors José Bonner and Bill Saxton for teaching me how to critically read and analyze scientific papers using this method. I’m honored to have the chance to pass along what they taught me.

I’ve written a shorter version of this guide for teachers to hand out to their classes. If you’d like a PDF, shoot me an email: jenniferraff (at) utexas (dot) edu. For further comments and additional questions on this guide, please see the Comments Section on the original post .

This piece originally appeared on the author’s personal blog and is reposted with permission.

Featured image credit: Scientists in a laboratory of the University of La Rioja by Urcomunicacion (Wikimedia CC BY3.0)

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the LSE Impact blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please review our Comments Policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

About the Author

Jennifer Raff (Indiana University—dual Ph.D. in genetics and bioanthropology) is an assistant professor in the Department of Anthropology, University of Kansas, director and Principal Investigator of the KU Laboratory of Human Population Genomics, and assistant director of KU’s Laboratory of Biological Anthropology. She is also a research affiliate with the University of Texas anthropological genetics laboratory. She is keenly interested in public outreach and scientific literacy, writing about topics in science and pseudoscience for her blog ( violentmetaphors.com ), the Huffington Post , and for the Social Evolution Forum .

About the author

95 Comments

Very good Indeed.I always Read Abstract First Time always ……Thanks

Great information and guide to reading and understanding scientific paper. However, there are non-scientific student asked to do scientific research and it would be great to actually give an example and you point out the answers to the steps in the sample article or journal cited. Thank you.

- Pingback: Very useful (for scientists too): How to read and understand a scientific paper: a guide for non-scientists – microBEnet: the microbiology of the Built Environment network.

- Pingback: Reader beware | Liblog

- Pingback: Research Roundup: DOAJ’s Clean Sweep, A.I. In The Classroom And More | PLOS Blogs Network

I can summarize it eve further: three stars by a number in a table = good, no stars = bad

within the context of the fact that a very sizable portion of scientific papers are falsified, what does this article mean?

Your “fact” needs explanation and evidence, otherwise it can be considered alternative.

That’s why you don’t skip step 11

I think it would be useful also to point out that, even after diligently pursuing all of these excellent steps, the reader is usually still unable to determine whether the subjects or materials even existed. Unlike with lay media, where most important stories are covered by multiple sources, and where facts are sometimes checkable from primary sources – even by readers – it is rare indeed that a reader can go beyond the words on the page.

Is the fact that you read instructions on how to read a paper not evidence that there is something wrong with the way we write papers?

The issue of scientific literacy is always challenging for my students. But this is the most practical and helpful guide I’ve ever seen on the web, thanks for this. I usually share with my students the following tips already mentioned above: – Learn the vocabulary before reading – Summarize the background in five sentences or less – Identify the BIG QUESTION

But the pieces of advice this guide gives are structured better and easier. I especially love this one: Don’t yet try to decide what the results mean, just write down what they are. Thanks again for writing this piece!

- Pingback: Como ler um artigo científico – um guia para não-cientistas | Antônio Carlos Lessa

you left out ask for the data, so you can check for yourself… (ie trust but verify)

an example a psychology paper that surveyed a group of people about conspiracy theories (n=137) and it’s main/only novel finding was that people that believed in conspiracies theories, there was a tendency for people to believe in mutually contradictory conspiracy theories. ie individual could believe that Princess Diana faked her own death, whilst at the same time had been murdered by MI5

The paper, was duly called – Dead and Alive – M Wood et al…

However. after requesting the data. there was not a single individual person that ticked the survey boxes, that simultaneously believed this finding. Not one person.

The problem, most people surveyed did not believe either of those conspiracies, and inappropriate stats method was applied to data, that assumed a non skewed dataset. Thus, not believing in A and not believing in B correlated, but it also gave a ‘result that believing in A, and Believing in B also correlated..

A very dumb paper… Author still hasn’t retracted it yet.

- Pingback: How to Read a Scientific Paper as a Non-Scientist » Public(s) Sociology

I love this! Great simmered-down resource for my undergrads- both science and non-science majors. Thanks for sharing!

“Web of Science” link is broken (at least for me) but a useable alternative is webofknowledge.com (same resource, different name).

I think it is important to note that the journal in which a paper is published is no proof as to the rigor of that paper. A listing in PubMed does not guarantee quality; thus, you need to focus on teaching people how to interpret the paper without relying on a simple JTASS approach to initial assessment. This may be a guide, but nothing more. I say this as a former editor of a MEDLINE journal. There can be good papers in bad journals and bad papers in good ones. But you are correct. Key questions are: What is the question? How will we answer the question? What answer did we get? Did we use the right tools to answer the question? What do we think it means? What else could we do? And thus we can train people to watch for sleights of hand, such as shifting primary outcomes, data mining, salami slicing, etc.

- Pingback: How to read and understand a scientific paper: a guide for non-scientists – Sociology of Knowledge

Yikes! This is a lot of work just to read a single paper! It’s almost the same as writing a paper! I understand the logic in why you recommend this, but the average person is going to be willing to spend 20-30 minutes reading and trying to learn. This method calls for multiple hours of effort and I just don’t seem many non-scientist people being willing to do that when they’re more curious than actually invested. I was really hoping this entry was going to make it easier to navigate the foreign and confusing world that these papers represent, and it probably will if someone does this process repeatedly for quite some time…..like a scientist…..but most of us aren’t scientists and don’t have that kind of time to dedicate to something that’s not our work or family.

By tradition, we expect our scientists to report their findings by codifying them in unreadable gobbledygook. Then we write instructions on how to decode that unreadable nonsense!!

We need to encourage papers to be written in everyday language so it is easier for all. Problem solved.

I wholeheartedly agree with Kaveh Bazargan. From personal experience as a non-scientist trying to do this with medical research papers is a very intimidating and isolating experience. Most people don’t have the time spare to even try to learn this skill. It would be great if systematic reviewers who are acknowledged experts in reading and analysing papers could find a way of communicating the important information about individual papers to non-scientists before – or instead of – burying them in systematic reviews and meta-analyses which are even more difficult to understand. Structured plain language summaries of primary research would be very helpful rather than individuals having to teach themselves how to read and understand a scientific paper which is written for other scientists in “unreadable goggledygook”. Many (most?) papers conceal methodogical flaws in the research conduct which are almost impossible to spot without years of scientific training.

I love this! Extraordinary cooled off assets for my students both science and non-science majors. A debt of gratitude is in order for sharing!

Regarding step 11, if you have access to Web of Science I recommend looking up how many citations the paper has (this will also vary depending on the age of the paper) and who cites it, and whether there even any replies to it in the peer-reviewed literature.

Do you literally do this for every paper you read? I’m curious how much time it takes you to go from start to finish on what you would consider a typical paper. How often do you read new articles a week?

This post has the laudable goal of helping nonscientists understand the primary literature, but the recommendations seem even more onerous than they have to be. For example, the idea that one should write down every single word that he/she doesn’t know? That sounds more like a task for a scientist scrutinizing the work of a rival. For a nonscientist, there may be dozens and dozens of unknown words, and chasing down the meaning of each one may cause a serious forest/trees problem. I agree that there’s no substitute for the hard work of digging into a paper, but following the prescribed advice to the letter would be utterly exhausting for almost any lay reader. I base these comments on my experiences as a biology researcher and undergraduate instructor.

- Pingback: How to read and understand a scientific paper: a guide for non-scientists – Agriculture Blog!

- Pingback: The Literary Drover No. 354 | The Literary Drover

- Pingback: Weekly Digest – February 6-12 – Austin Science Advocates

- Pingback: Impact of Social Sciences – How to read and understand a scientific paper: a guide for non-scientists | ARC Playground

I really like your post and the effort, but much of the problem wouldn’t exist if we, academics, did a better job in writing down the correct conclusions. Researcher degrees of freedom are seldom properly understood and we keep on having the tendency to be overdeterministic about statistics that are not intended as such. Of course we want to communicate in black and white about our tests (significance!) because it is a human tendency to persuade the reader. Most of the research probably is not as inconsistent as it first seems but we forget to report the proper statistics to see so (CI around the ES)

- Pingback: Rare Disease Research – moving from Study Participant to Research Partner | hcldr

- Pingback: Tips on Reading Scientific Papers – The Inner Scientist

- Pingback: How to read and understand a scientific paper | EDS and Chronic Pain News & Info

Thank you very much for sharing a guide that will help me to follow the best standards for writing a scientific paper even I am not a scientist.

- Pingback: Știința din spatele convingerii – 24 de ore

- Pingback: How to read and understand a scientific paper: A guide for non-scientists. | Climate Change

Reading the abstract last is one, not the, way to read a paper. It it biases the naive reader, then they are not reviewing with a level of skepticism required to evaluate science. We put abstracts first because they lay out the problem, overview the sample and design, and tersely describe what they think they discovered. Then, as I read, I have a roadmap in my head of what to look for to determine for myself whether or not they found something noteworthy.

What is the problem? Are hypotheses to be tested likely to illuminate/clarify the problem? Is the sample appropriate for testing and was it sampled without imputing bias? Were measures appropriate and do they have a history of validity? We the analytics applied appropriate for testing at the level of power needed give the sample size? [Here even many scientist are ill-equipped to judge.] After enumerating results, do the authors list weaknesses in their design that might suggest replication is necessary? If not, check for snow – as in snowjob. If significance levelsare low or variables correlate with one another too much, are moderators discussed? [e.g., results hold for males but not females, old vs young, fat vs skinny, etc.). If so, why were data not re-analyzed to control for moderator effects on results?

Lastly, if the word “prove” appears anywhere in the paper, assume it is junk science (like fake news). Research is never ever done to prove anything. Research is only done to find out. Once a preponderance of studies report a similar finding looking at the same problem with different people, measures, designs, and statistical analyses, then you have something like proof; consensus.

Lastly, if you are a conspiracy theory believer, you will disbelieve any scientific study that does not support your word view. Keep this in mind. A few studies that run counter to the prevailing consensus is not PROOF that your conspiracy is correct, and mainstream science is wrong. I do not know a single scientist (and I know thousands globally) who do not consider climate change to be well-evidenced. Similarly, evolutionary theory remains useful – our current understanding of genomic medicine hinges on cellular mutation, which is evolution on a microscopic scale.

This is a very useful set of instructions, but I found the following statement highly amusing: “Before you begin reading, take note of the authors and their institutional affiliations. Some institutions (e.g. University of Texas) are well-respected; others (e.g. the Discovery Institute) may appear to be legitimate research institutions but are actually agenda-driven.”

All research institutions are agenda driven (including my alma mater, the University of Texas), because funding and professional advancement depend on results. Researchers are fallible humans and subject to temptation and error. There is a very big lawsuit pending against Duke University (see below) for falsifying data.

When I read any research (especially medical), I now search for evidence of legal or professional action. So you might add that as #12: “Lawsuits? Retractions?” Caveat lector.

http://science.sciencemag.org/content/353/6303/977.full

http://www.dukechronicle.com/article/2016/09/experts-address-research-fabrication-lawsuit-against-duke-note-litigation-could-be-protracted

- Pingback: Four short links: 27 June 2017 | Vedalgo

- Pingback: How to read and understand a scientific paper: a guide for non-scientists | ExtendTree

- Pingback: Bookmarks for June 26th through June 27th | Chris's Digital Detritus

- Pingback: Four short links: 27 June 2017 | A bunch of data

Weird advice, like: ‘I always read the abstract last’ . This is advice for referees, not for general readers. I always read the abstract first.

An abstract can be misleading, but I am often not qualified enough to judge that. Actually, this blog post title and abstract are misleading too: your advice is for referees, not for non-scientists. So you wanted to provide an immersive experience into a misleading piece, well done 😉

First thing, get rid of the word proof. This is a huge error in that even if you have reputable scientists, journals, institutions, etc. that what is published, especially in a single article, is anything resembling a fact. It is merely research findings from one instance and in no way forms a fact. This is the next level of misinterpretation of science, even among those able to comprehend the journal article, that science produces or discovers facts. There is nothing that is factual that we know of.

Several comments:

For the mid-term exam in a graduate class I took in experimental design the professor would select half a dozen articles from the peer reviewed literature, tell her students to pick three and explain what they had done wrong. New articles for every class and she never ran out.

Beware of articles published in inappropriate journals, no matter how respectable (E.g., something about sociology or criminology published in a medical journal). This is a strategy for sneaking agenda driven research past the peer review process by going to a journal whose reviewers are likely to be unfamiliar with the subject while the editors are sympathetic to the agenda.

There is a reason research papers are written in what looks like “scientific gobbledygook” to lay persons. They are not intended for a lay audience and the goal is to be extremely precise with the technical details of what was done and found so other scientists can examine the results and, most important, attempt to replicate them.. There is no way to simplify the language and put it in lay terms without losing the precision required for a scientific study. E.g., a particle physicist may give a lay explanation of an experiment in metaphorical terms of little balls of energy smashing into each other, but their peers are going to want to see the pages and pages of mathematics that really describe what was happening.

- Pingback: Climate News: Top Stories for the Week of June 24-30 - ecoAmerica

I would add “Check the source of funding for the research.” If paper on the safety of glyphosate is funded by Bayer or Monsanto, or a paper on climactic change is funded by Exxon, read no further.

- Pingback: Stats Trek IV | The IAABC Journal

Get the dissertation writing service students look for these days with the prime focus being creating a well researched and lively content on any topic.

The non-scientist should pay extra attention towards this article for the non-technical writing and understanding for them.

A lot of a researcher’s work includes perusing research papers, regardless of whether it’s to remain progressive in their field, propel their logical comprehension, survey compositions, or assemble data for a task proposition or concede application. Since logical articles are not the same as different writings, similar to books or daily paper stories, they ought to be perused in an unexpected way.

- Pingback: 2017 – collected articles – The Old Git's Cave

Thanks, I’ll use this a lot for my MSc Thesis.

Those are some great tips but please don’t forget that each school has its own requirements to academic papers.

Clarifying your methodology for reading science paper: excellent idea and great information. Thanks a lot!

Thanks for sharing this blog. Its very helpful for me and I bookmarked this for future

Excelente trabajo, original. Lo recomendaré para mis estudiantes de Posgrado. Si no hay problema, me gustaría hacer una traducción al castellano para el uso de mis estudiantes de pregrado de Sociología.

Excellent work,original. I will recommend it for my graduate students. If there is no problem, I would like to make a translation into Spanish for the use of my undergraduate Sociology students.

Hi Luis, all our works are CC licensed so you are more than welcome to make a translation provided you link back to the original source. See here for details: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en_GB

Great information , it is very helpful thanks for sharing the blog .

Step 1 and 10 is a great idea, but I still think it’s possible to read the abstract with the introduction and still keep an open mind? and shouldn’t they keep their results for the interpretation section? sorry new to reading scientific papers

Step 1 and 10 is a great idea, but I still think it’s possible to read the abstract with the introduction and still keep an open mind? and shouldn’t they keep their results for the interpretation section? sorry new to reading scientific papers

- Pingback: Eight Blogging Mistakes Which Most Beginners Make | Congress of International Society of Peritoneal Dialysis

- Pingback: Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) is a rare and often fatal form of breast cancer. In IBC, lymphatic vessels in the skin are blocked causing the breasts to appear swollen and red. - Versed Writers

- Pingback: Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) is a rare and often fatal form of breast cancer. In IBC, lymphatic vessels in the skin are blocked causing the breasts to appear swollen and red. – essay studess

Thank you for sharing the tips, they were very helpful.

- Pingback: Introduce Yourself (Example Post) – Dr. Hemachandran Nair G

The article is extremely helpful. Considering that scientific research are not as easy, the tips in the article are great.

- Pingback: Seattle: notes from a pandemic: 9 | Genevieve Williams

Thank you for posting this. It has really helped a lot, especially for those of us who always read the abstract first haha

Thanks for writing this blog. It is very much informative and at the same time useful for me

Yeah, great advice on how to be objective from someone who openly declares their prejudice in the opening statement.

- Pingback: How to Read and Understand a Scientific Paper -

- Pingback: Mirroring your partner’s stress, if your partner is anxious – Celia Smith

Do you in a real sense do this for each paper you read? I’m interested what amount of time it requires for you to go beginning to end on what you would think about an average paper. How frequently do you read new articles seven days?

- Pingback: CRAFT: Writing Science by Sarah Boon | Hippocampus Magazine - Memorable Creative Nonfiction

- Pingback: HOW TO READ AND UNDERSTAND A SCIENTIFIC PAPER FOR NON-SCIENTIST – KALISHAAR

That is literally my question too, I see it as quite time consuming to conduct such a lengthy process for all scientific articles we come across especially as one has other responsibilities to give attention too

- Pingback: Straight from the horse’s mouth: How to read (and hopefully understand) a scientific research paper – Notes from a small scientist

- Pingback: How to read cannabis research papers | Toronto Cannabis Delivery - Toronto Relief Chronic Pain

- Pingback: How to read cannabis research papers - Social Pothead

- Pingback: 2 – Cory Doctorow on unfair contracts for writers - Traffic Ventures

There is a reason research papers are written in what looks like “scientific gobbledygook” to lay persons. They are not intended for a lay audience and the goal is to be extremely precise with the technical details of what was done and found so other scientists can examine the results and, most important, attempt o replicate them.

- Pingback: How to Read Cannabis Research Papers – BARC Collective

- Pingback: Your 3-Step Guide to Start Reading Research Papers

- Pingback: How to Read Cannabis Research Papers - BARC Collective

Thanks for posting this. You are doing a service to the general public and also graduate students by not only posting this but answering all sincere questions. I have a Ph. D. in Zoology and have been a peer-reviewer for at least 12 papers and am first author of three peer-reviewed papers. I have taught statistics in two universities as a contract professor and all of my papers rely on use of statistics. To answer a frequently asked question, yes, personally it can take me a couple of hours or several more to read some papers. This is true for my colleagues as well. Scientific papers are written so as to be as concise as possible and this can make them hard to read. They often also use technical terms which one has to look up. At least biology and statistics. nothing I have read (or written) has been in “goobledygook” or purposely incomprehensible jargon but they do use terms and concepts that are probably unfamiliar to the layman. I think what the author means, by her comment on absstracts can be intepreted as “don’t JUST read the abstract. Be sure to read the introduction. Personally I go to the discussion and conclusion next.

- Pingback: Bagaimana Cara Download Jurnal Gratis Itu? - EMAF

- Pingback: How to read a clinical research study about trichotillomania

- Pingback: Reading studies: Resources – 495R Research Studies

Your writing skills and passion for sharing your knowledge and experiences are truly outstanding. . Keep writing and inspiring others with your words.

I would add, look at who funded the study and their financial interests. Most science is not independent it is funded by those with an agenda. Look at the demographic data, length of time the study took place, what was left out, where you might need more information. Look at who was included and excluded in the data set. Anyone that has taken statistics knows what you include or exclude in the data set can skew and or outright change the outcome.

- Pingback: Undergraduate Economics Resources – tanvi madhaw

- Pingback: How Do I Critically Consume Quantitative Research?

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Related Posts

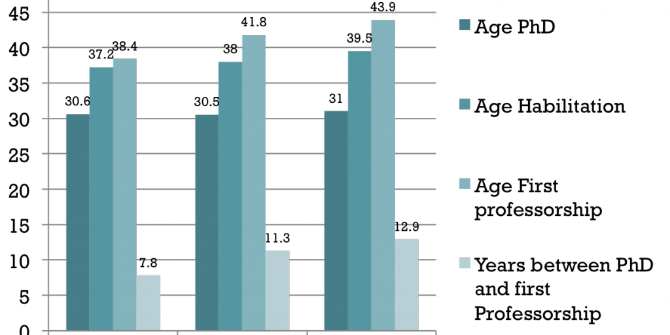

How Academia Resembles a Drug Gang

December 11th, 2013.

What would honest university rankings look like?

September 11th, 2023.

When publishing becomes the sole focus of PhD programmes academia suffers

December 5th, 2022.

Student evaluations of teaching are not only unreliable, they are significantly biased against female instructors.

February 4th, 2016.

Visit our sister blog LSE Review of Books

- Peterborough

Reading Scientific Papers

Understanding and analyzing empirical articles, understanding scientific papers, reading as a process, step 1: preview the scientific paper, introduction, step 3: reflect and take notes.

The first step to reading more critically and efficiently is to understand the structure of the source you’re reading. Thankfully, scientific papers, a.k.a. articles, typically follow a standard format that you may already be familiar with from writing lab reports—both are based on the scientific method and typically contain the following four sections: The introduction is where the authors present their research question and explain their hypotheses and predictions. The methods section details how they conducted the study and analyzed the data, and the results section summarizes the key findings. Finally, scientific papers end with a discussion where the authors interpret the results, explain whether they support the hypothesis, and relate the study to the broader field of research. This common structure helps scientists better communicate their research with one another and the larger public—armed with an understanding of this structure, you’ll now be able to better understand and analyze scientific research.

You likely think of reading as a one-step event: you pick up a book or article and read it. Experts on reading, however, suggest that a multi-step process can make you a more efficient and critical reader.

Step 1: Preview the source to get a sense of what it will offer

Step 2: Read for understanding and analysis

Step 3: Reflect and takes notes on the reading

Keep in mind that how you accomplish each of these steps will differ depending on what kind of source you are reading. The remainder of this guide details how to approach each step when reading scientific papers.

Before you begin to read a scientific paper, consider how it relates to the course, your experiment, or your research project. Next, preview the source itself to determine its main goal, method, and findings. Your first step should be to read the abstract, which provides a brief summary of the paper . As you read, ask

- WHAT did the authors want to find out?

- WHY did they want to know this?

- HOW did they answer the question?

- WHAT did they find out?

- SO WHAT? Why is this research important?

Keep in mind that reading the abstract alone will not provide you with an understanding of the source. You must read the article in full, section by section: the next portion of this guide will help you focus your reading to both understand what the author is trying to say and to analyze and evaluate the source.

Step 2: Read for Understanding and Analysis

Each section of a scientific paper is carefully organized to present information in an expected format—as you become familiar with this standard structure, you’ll be able to easily locate the specific information you seek. Use the following descriptions and guiding questions to navigate each section as you read. You may also want to use our Template for Taking Notes on Scientific Papers to organize your notes after you read each section.

A careful reading of the introduction is essential to understanding the reasons for and goals of a scientific study. In this section, authors provide an overview of the general topic, summarizing background information from the existing literature. The authors explain how their research adds to current knowledge and convey its importance. The introduction is also where you’ll find the research question(s) and expected answer(s)—in scientific papers, these answers come in the form of hypotheses and predictions (to learn more about these, check out our guide to Understanding Hypotheses and Predictions . Introductions often conclude with a brief summary of how the authors tested their hypotheses—a preview of the methods section.

Questions to Check Your Understanding

- What is the research question?

- Why should it be studied (what gap does this research fill)?

- How has it been studied before?

- What are the hypotheses and predictions?

Questions to Guide Your Analysis & Evaluation

- Is the question clear?

- How does the work compare to other studies in the field?

- Will this research contribute to our knowledge in an important way?

- Is the hypothesis justified?

In the methods section, the authors provide a detailed account of how they completed their study or experiment, the materials and/or participants they used, how they measured particular variables, and how they analyzed their data. As a reader, you will want to pay careful attention to this section and determine the strengths and weaknesses of the study’s design.

- How did the authors conduct the study or experiment?

- What materials and measures did they use?

- How did they sample the study area, subjects, or population?

- How did they analyze the collected data?

- Are the measures appropriate and clearly related to the research question? Do they adequately test the hypothesis?

- Does the sampling (e.g., study areas, subjects, participants) fairly represent the larger population of the study?

- Is the analysis appropriate for the data?

- Are there noticeable flaws in the method?

The results section summarizes the data in text, figures, and tables. As a careful reader, you should examine this section and consider not only what the authors found but also what findings they chose to present and how (for example, which results warranted display in a figure? which didn’t?).

- What are the major findings?

- How are the findings presented/displayed?

- Are enough data displayed to demonstrate the results?

- How do the findings relate to the hypotheses?

- Are the statistics appropriately presented?

- Did you note patterns that the author does not mention?

In this section, the authors analyze their findings and explain whether their results support their hypotheses and predictions. The authors explain why (or why not) by comparing not only their results but also their approach to those of other related studies, providing essential context and grounding their work in the existing literature. They also discuss the limitations, importance, and implications of their results and detail possible applications, extensions, or revisions of their study.

- Did the data support the hypothesis?

- If not, does the author explain why?

- How do the results compare to those of other studies?

- Are the findings significant?

- What are the limitations and applications?

- Did the authors interpret the results appropriately?

- Are you persuaded by the findings?

- How significant are the limitations of the study?

- Do the authors offer plausible applications for their research?

- Does the discussion reflect the major points from the introduction?

Taking notes while you read is time consuming and can even distract you from focusing on the ideas you are reading. Instead, separate the acts of reading and notetaking by reading a section or a few pages and then stopping to take notes. Make sure that your notes provide answers to the questions posed in each of the sections above. Again, you may want to use our Template for Taking Notes on Scientific Papers to organize your notes as you go.

After you have read and taken notes on the paper, be sure to reflect on it. How does it compare to other papers you’ve read on this topic? How does it relate to your experiment or research project? How might you use it in your course work, lab report, or paper?

Research Techniques for Undergraduate Research

- Library Research

- Citation Tracing/Tracking in Google Scholar

- Strategies for Research

- Chicago Manual of Style

- Writing Research Papers

- How to Read a Citation

- How to read and understand a scientific paper

- Skimming an article

- Workshop presentation powerpoint

- Post-Workshop Quiz

- Post-Workshop Reflection

How to Read a Scientific Paper overview

Below, you'll find two different articles about how to read a scientific paper. The second one is written by a science journalist and was added to this guide in 2024. We hope you find both articles useful. They overlap and bring useful techniques to light.

How to read and understand a scientific paper: a guide for non-scientists

- Handout for How to Read and Understand a Scientific Paper: A Guide for Non-Scientists

Reprinted by permission of the author, Jennifer Raff, Assistant Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Kansas, https://about.me/jenniferraff :: original URL: https://violentmetaphors.com/2013/08/25/how-to-read-and-understand-a-scientific-paper-2/ Last week’s post ( The truth about vaccinations: Your physician knows more than the University of Google ) sparked a very lively discussion, with comments from several people trying to persuade me (and the other readers) that their paper disproved everything that I’d been saying. While I encourage you to go read the comments and contribute your own, here I want to focus on the much larger issue that this debate raised: what constitutes scientific authority?

It’s not just a fun academic problem. Getting the science wrong has very real consequences. For example, when a community doesn’t vaccinate children because they’re afraid of “toxins” and think that prayer (or diet, exercise, and “clean living”) is enough to prevent infection, outbreaks happen .

“Be skeptical. But when you get proof, accept proof.” –Michael Specter

What constitutes enough proof? Obviously everyone has a different answer to that question. But to form a truly educated opinion on a scientific subject, you need to become familiar with current research in that field. And to do that, you have to read the “primary research literature” (often just called “the literature”). You might have tried to read scientific papers before and been frustrated by the dense, stilted writing and the unfamiliar jargon. I remember feeling this way! Reading and understanding research papers is a skill which every single doctor and scientist has had to learn during graduate school. You can learn it too, but like any skill it takes patience and practice.

I want to help people become more scientifically literate, so I wrote this guide for how a layperson can approach reading and understanding a scientific research paper. It’s appropriate for someone who has no background whatsoever in science or medicine, and based on the assumption that he or she is doing this for the purpose of getting a basic understanding of a paper and deciding whether or not it’s a reputable study.

The type of scientific paper I’m discussing here is referred to as a primary research article . It’s a peer-reviewed report of new research on a specific question (or questions). Another useful type of publication is a review article . Review articles are also peer-reviewed, and don’t present new information, but summarize multiple primary research articles, to give a sense of the consensus, debates, and unanswered questions within a field. (I’m not going to say much more about them here, but be cautious about which review articles you read. Remember that they are only a snapshot of the research at the time they are published. A review article on, say, genome-wide association studies from 2001 is not going to be very informative in 2013. So much research has been done in the intervening years that the field has changed considerably).

Before you begin: some general advice Reading a scientific paper is a completely different process than reading an article about science in a blog or newspaper. Not only do you read the sections in a different order than they’re presented, but you also have to take notes, read it multiple times, and probably go look up other papers for some of the details. Reading a single paper may take you a very long time at first. Be patient with yourself. The process will go much faster as you gain experience.

Most primary research papers will be divided into the following sections: Abstract, Introduction, Methods, Results, and Conclusions/Interpretations/Discussion. The order will depend on which journal it’s published in. Some journals have additional files (called Supplementary Online Information) which contain important details of the research, but are published online instead of in the article itself (make sure you don’t skip these files).

Before you begin reading, take note of the authors and their institutional affiliations. Some institutions (e.g. University of Texas) are well-respected; others (e.g. the Discovery Institute ) may appear to be legitimate research institutions but are actually agenda-driven. Tip: g oogle “Discovery Institute” to see why you don’t want to use it as a scientific authority on evolutionary theory.

Also take note of the journal in which it’s published. Reputable (biomedical) journals will be indexed by Pubmed . [ EDIT: Several people have reminded me that non-biomedical journals won’t be on Pubmed, and they’re absolutely correct! (thanks for catching that, I apologize for being sloppy here). Check out Web of Science for a more complete index of science journals. And please feel free to share other resources in the comments!] Beware of questionable journals .

As you read, write down every single word that you don’t understand. You’re going to have to look them all up (yes, every one. I know it’s a total pain. But you won’t understand the paper if you don’t understand the vocabulary. Scientific words have extremely precise meanings).