Arguments for and Against Physician-Assisted Suicide

The right to legally end your own life is a heavily debated issue..

Posted September 16, 2020 | Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

- Suicide Risk Factors and Signs

- Find a therapist near me

Although September is designated National Suicide Awareness Month, there are those who think about suicide 12 months of the year. They may be survivors of suicide loss—the family and friends of those who have taken their own lives—or they may be people who often contemplate suicide or have already made attempts. Articles and anecdotes of suicide published during the month of September and at other times most often focus on prevention. But there’s another side to the story.

Many people believe that ending one’s own life is a human right, particularly for those who are terminally ill and suffering from indescribable pain or impairment. In the United States, however, it is only a right for those in the nine places where physician-assisted death is now legal when strict guidelines are followed. In Oregon, Washington, Vermont, Maine, Hawaii, California, Colorado, New Jersey, or the District of Columbia, eligible, terminally ill patients can legally seek medical assistance in dying from a licensed physician. In all of these places, a physician can decide whether or not to provide that assistance. At the same time, other states—Alabama, Arizona, Georgia, Idaho, Louisiana, New Mexico, Ohio, South Dakota, and Utah—have, in recent years, strengthened their laws against assisted suicide. In 2018, for instance, Utah amended its manslaughter statute to include assisted suicide.

In a nutshell, it works like this: The patient orally requests legal medical assistance in dying from a qualified physician. That physician must assess and confirm the patient’s eligibility and also inform the patient of alternative treatments that provide pain relief or hospice care. At that point, a second physician must confirm the patient’s diagnosis and mental competence to make such a decision. If deemed necessary, either physician can require the patient to undergo a psychological evaluation. The patient must then make a second oral request for assistance. Once approved, the original physician writes a prescription for lethal medication (usually a high-dose barbiturate powder that must be mixed with water) that the patient can self-administer when and where they choose, as long as it is not in a public place. Some people never fill the prescription or fill the prescription but never take the medication. Those who do generally fall asleep within minutes and die peacefully within a few hours.

Several organizations have been formed to both support and oppose physician-assisted dying for moral, ethical, and legal reasons. Groups such as Death with Dignity and Compassion and Choices are in favor of what they call “medical aid in dying” and work to provide assistance and lobbying efforts to initiate legal “right to die” programs in every state. They support patient autonomy and choice, particularly in the case of terminal illness. To these groups and their supporters, most of whom come to this side of the issue as a result of agonizing personal experience, death with dignity is a human rights issue and those who are suffering are entitled to a peaceful death.

On the other side of the debate, groups like the Patients Rights Council and Choice Is an Illusion work to tighten laws against euthanasia and medical aid in dying. They fear a complete lack of oversight at the moment of death, as well as normalization of the process to the degree that patients will feel they must relieve their families of the burden they are inflicting by living with their illness. They are concerned that decisions will be made by others on behalf of those too ill to speak for themselves. These groups believe the job of a physician is to find ways to eliminate patients’ suffering, not the patients themselves. They do not believe a physician is qualified to make the decision to assist in ending a life.

In the end, no group really wants assisted suicide to be the final answer, but those who favor medical aid in dying see little recourse for those living with unbearable chronic pain , who are terminally ill, and who have no hope of improving the quality of their lives because medical science has not yet caught up with our modern potential for longevity.

Compassion and Choices: https://compassionandchoices.org/

Death with Dignity: https://www.deathwithdignity.org/

Patients Rights Council: http://www.patientsrightscouncil.org/site/

Choice is An Illusion: https://www.choiceillusion.org/2019/04/in-last-ten-years-at-least-nine-…

Susan McQuillan is a food, health, and lifestyle writer.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

The Impact of Physician Assisted Suicide on Suicide Rates and Individual Propensities for Suicidal Action

Add to collection, downloadable content.

- February 26, 2019

- Affiliation: College of Arts and Sciences, Department of Political Science

- In the past decade, Physician Assisted Suicide (PAS) has emerged as a heavily contested policy issue for state governments. A central political argument against PAS claims that access to PAS practices enables terminally ill individuals—who were once statistically unlikely to commit suicide—to develop an increased risk for suicidal action. This study analyzes this claim by examining the relationship between policy and behavior, and assessing whether PAS legislation influences suicide risk. By analyzing annual suicide rates released by state health departments, I find that PAS legislation causes suicide rates to increase. Furthermore, I additionally measured individuals’ propensities for suicidal action by assessing which demographic traits enable an individual to be most at risk of committing suicide, and comparing these traits with traits that increase an individual’s risk of pursuing PAS. I find that some of the risk factors for suicide do not align with the risk factors for PAS, implying that PAS enables certain individuals to develop an increased risk of suicide. Therefore, this study provides two pieces of evidence that PAS ultimately affects suicidal behavior.

- Education Level

- Suicide Rate

- Physician Assisted Suicide

- Marital Status

- https://doi.org/10.17615/8qv9-4z31

- Honors Thesis

- In Copyright

- McGuire, Kevin T.

- Bachelor of Arts

- University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

This work has no parents.

Select type of work

Master's papers.

Deposit your masters paper, project or other capstone work. Theses will be sent to the CDR automatically via ProQuest and do not need to be deposited.

Scholarly Articles and Book Chapters

Deposit a peer-reviewed article or book chapter. If you would like to deposit a poster, presentation, conference paper or white paper, use the “Scholarly Works” deposit form.

Undergraduate Honors Theses

Deposit your senior honors thesis.

Scholarly Journal, Newsletter or Book

Deposit a complete issue of a scholarly journal, newsletter or book. If you would like to deposit an article or book chapter, use the “Scholarly Articles and Book Chapters” deposit option.

Deposit your dataset. Datasets may be associated with an article or deposited separately.

Deposit your 3D objects, audio, images or video.

Poster, Presentation, Protocol or Paper

Deposit scholarly works such as posters, presentations, research protocols, conference papers or white papers. If you would like to deposit a peer-reviewed article or book chapter, use the “Scholarly Articles and Book Chapters” deposit option.

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Diet & Nutrition

- Supplements

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

What Is the Debate Over Physician-Assisted Suicide?

The debate over the ethics and legality of physician-assisted suicide (PAS) is a long-standing and highly charged one. Notable legal challenges in the United States include Washington v. Glucksberg and Vacco v. Quill, both in 1997 and both of which upheld bans on PAS in Washington State and New York.

On the opposite side of the debate, Oregon enacted the first law legalizing PAS with the passing of the Oregon Death with Dignity Act in 1994. Since then, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Maine, Montana, New Jersey, New Mexico, Vermont, Washington, and Washington D.C. joined Oregon in enacting similar legislation.

Abroad, PAS in various forms (and with various restrictions) is currently legal in Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Colombia, Ecuador, Germany, Jersey, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Portugal, Scotland, and Spain. Though attempts were made to lift assisted suicide bans, it is still illegal in Denmark, England, France, Ireland, South Africa, Switzerland, and Wales, among others.

This article takes a look at both sides of the debate over physician-assisted suicide, including the "morality" of PAS and whether it violates or supports the Hippocratic Oath ("first, do no harm").

What Is Physician-Assisted Suicide?

Physician-assisted suicide (PAS) is defined as the voluntary termination of one's own life by the administration of a lethal substance with the direct or indirect assistance of a physician . In the United States, a physician is a licensed practitioner with a doctor of medicine (MD) or doctor of osteopathic medicine (DO) degree.

PAS is not the same thing as euthanasia . Euthanasia takes place when a physician performs the intervention; with PAS, the physician provides the necessary means and the patient performs the act.

There are arguments for and against PAS based on ethics (the designated code of conduct for professions like medicine), mortality (the subjective designation of right or wrong), and legality (the interpretation of law).

Legal Challenges to Consent Laws

Many who opposed PAS are concerned that if assisted suicide is allowed, euthanasia won't be far behind and may lead to "mercy killings" in which people are euthanized without consent. These include people who are on life support, have serious mental illness, or are otherwise unable to grant informed consent for such actions.

Those who endorse PAS consider such conjecture inflammatory, arguing that the enactment of such laws goes against every constitutional law in place to ensure patient autonomy and self-determination. This includes the right to refuse or accept any medical procedure protected by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Proponents of PAS further argue that a ban on assisted suicide restricts a patient's right of self-determination, namely by denying the choice to "die with dignity."

Moreover, physicians are not required by law to assist in the ending of a patient's life. They can conscientiously refuse and are protected by law to do so.

Violation of the Hippocratic Oath

The Hippocratic Oath is an oath of ethics historically taken by physicians that was written between the fifth and third centuries BC. Central to the oath is the phrase primum non nocere (meaning “first, do no harm”).

Opponents of PAS believe that the participation of a physician in a patient's suicide is the definition of harm and directly contradicts the oath. Doing so, they argue, is equivalent to "killing" or "murder."

Proponents of PAS argue that "death" and "harm" are not synonymous and neither are "suicide" and "murder." Many of these terms are legally defined and, as such, are not seen to be equivalent in the eyes of the law.

Countering this argument is the word "harm," which is legally defined as the "loss or damage of a person's physical well-being." While this may suggest the loss of life is "harm," the Hippocratic Oath is ultimately a principle rather than and law and the use of the term in the context is subject to debate.

Limit of Patient Autonomy

It was determined in the case of Bouvia v. Superior Court in 1986 that “the right to die is an integral part of our right to control our own destinies so long as the rights of others are not affected.”

The lawyers for Elizabeth Bouvia, a young quadriplegic woman who suffered from cerebral palsy , successfully argued that a person could not be forced to stay alive (in this case, through forced feeding) if their quality of life is severely and irreparably in decline. Doing so essentially deprives a patient of autonomy, including the right to die.

Opponents of PAS, many of whom would oppose forced feeding, nevertheless regard the Bouvia case and PAS as non-equivalent. Central to the argument is that PAS is not a completely autonomous act; it requires the assistance of another person.

Proponents of PAS counter that there is equivalence and that forcing a person to live with extreme, intractable suffering is unethical. By denying PAS, these same individuals may be forced to take extreme and violent actions to end their lives (and possibly fail).

Alternatives Make PAS Unnecessary

Palliative care is the practice of increasing comfort and easing pain and physical and emotional suffering in people with severe illness. Hospice care is a form of palliative care where comfort and pain control are provided when life-extending treatment is no longer desired.

Proponents of PAS argue that palliative and hospice care are humane and provide people the means to die with dignity if they are terminally ill.

Opponents of PAS counter that this excludes many with severe illnesses who will not improve and are exposed to needless suffering. They argue that PAS is an entirely different issue unrelated to palliative or hospice care.

Under the law, only people with six months or less to live are afforded coverage under Medicare and most other insurance. Palliative care can last for years. PAS, on the other hand, is the legal means to end a person's suffering whose life may or may not end soon.

Moreover, some people in hospice care choose to stop life-extending treatment because of the financial burden it places on their families. Supporters of PAS contend that the same choice should be afforded to people with severe, intractable illnesses who may also want to protect their families from financial harm.

Risk of 'Suicide Contagion'

Suicide contagion is an increase in suicide and suicidal behaviors as a result of exposure to suicide or suicidal behaviors within one’s family, from peers, or through media reports.

Opponents of PAS argue that providing a person with the legal means to end their life may promote suicide as a "solution" and encourage others to do the same.

Proponents of PAS point out that suicide contagion is not associated with a desire to end one's life for long-standing medical reasons but rather a response to emotional trauma, such as the suicide of someone the person was close to.

Studies investigating suicide rates after the passing of PAS laws have thus far found no association. A multi-center review of studies published in 2022 concluded that "no study has found a negative association between assisted suicide and non-assisted suicide."

In fact, one study from Oregon found a reduction in suicide rates among other males following the passage of that state's law.

In addition, there is no evidence that people "rush" to get PAS once laws are enacted. While the number of assisted suicides in Oregon has increased from 16 in 1998 to 278 in 2023, the rate of increase has been slow and gradual. Over 25 years, only 2,454 assisted suicides have been performed in the state.

PAS May Benefit Insurers and Others

There are some who argue that PAS will benefit insurers who can "save money" by avoiding the cost of life-extending treatments that could last for years. Over time, insurers may not only promote PAS to their patients but encourage it.

To date, there is no evidence of that occurring. While it is true that the cost of treating an illness like cancer can cost tens of thousands of dollars (and sometimes more), there is little evidence that insurers are "eager" to fund PAS.

A study published in the American Journal of Public Health found that many insurers will not cover the cost of a lethal dose of Seconal (secobarbital), a barbiturate drug most commonly used in PAS. As such, people are more often denied access to PAS due to the cost, particularly poor people.

Federal law currently prohibits Medicare, Medicaid, or any other government insurance from paying for or covering any expense associated with assisted suicide even in states where PAS is allowed.

Moreover, given the relatively modest number of patient-assisted suicides to date—as of 2022, 2,422 in California, 2,454 in Oregon, 291 in Washingon, 246 in Colorado, and 17 in Vermont—there is currently no indication that insurance practices have shifted from life-extending treatments to PAS.

Patient's Judgement May be Clouded by Depression

A concern frequently shared among people whose loved ones chose to stop life-saving treatment is that they are "just depressed" and will eventually change their minds.

The same concerns are shared among many opponents of PAS who express fears that not enough may be done to screen people for depression and other psychiatric illnesses who might otherwise avoid PAS if they are properly treated.

While it is true that a person with severe, intractable illness is almost certain to have a certain degree of anxiety or depression, proponents of PAS argue that the medical workup prior to the approval of PAS is extensive and intended to take that into account.

In California, for example, a person wanting to pursue PAS must be evaluated by a psychiatrist or licensed psychologist in addition to obtaining a confirmed diagnosis of a terminal illness with a life expectancy of less than months. Some states require multiple diagnoses from multiple providers.

To date, less than 1% of people who underwent PAS in Oregon were diagnosed with a mental illness. However, all were diagnosed with a terminal illness in which they were expected to live for less than six months.

Physician-assisted suicide remains a hotly contested topic despite laws allowing for it in 10 U.S. states and the District of Columbia. Arguments for and against assisted suicide include limits on patient autonomy, interpretation of the Hippocratic Oath, insurance coercion, whether current regulations are sufficient or lacking, and how current laws may affect future ones.

Connecticut General Assembly. Suicide - assisted: court cases; federal laws/regulations .

Patients Rights Council. Assisted suicide laws in the United States .

Congress.gov. Amdt14.S1.6.5.1 Right to Refuse Medical Treatment and Substantive Due Process .

Ahlzen R. Suffering, authenticity, and physician assisted suicide . Med Health Care Philos. 2020;23(3):353–359. doi:10.1007/s11019-019-09929-z

American Medical Association. Bouvia v. Superior Court: quality of life matters .

National Institute on Aging. What are palliative care and hospice care?

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Hospice Benefits .

Doherty AM, Axe CJ, Jones DA. Investigating the relationship between euthanasia and/or assisted suicide and rates of non-assisted suicide: systematic review . BJPsych Open. 2022 Jul;8(4):e108. doi:10.1192/bjo.2022.71

Regnard C, Worthington A, Finlay I. Oregon Death with Dignity Act access: 25 year analysis , BMJ Support Palliat Care . 2023 Oct 3:spcare-2023-004292. doi:10.1136/spcare-2023-004292

Buchbinder M. Access to aid-in-dying in the United States: shifting the debate from rights to justice . Am J Public Health. 2018 June;108(6):754–759. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2018.304352

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Assisted Suicide Funding Restriction Act of 1997 .

CNN. Physician-assisted suicides fast facts .

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Conceptual, legal, and ethical considerations in physician-assisted death . In: Physician-Assisted Death: Scanning the Landscape: Proceedings of a Workshop . Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2017.

Braverman D, Marcus B, Wakim P, Mercurio M, Kopf G. Healthcare professionals’ attitudes about physician-assisted death: An analysis of their justifications and the roles of terminology and patient competency . Journal of Pain and Symptom Management . 2017 Oct;54(4):538-545.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.07.024

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hospice care. Updated 07/06/16.

Emanuel EJ, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Urwin JW, Cohen J. Attitudes and practices of euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide in the United States, Canada, and Europe . JAMA . 2016 Jul 5;316(1):79-90. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.8499. Erratum in: JAMA. 2016 Sep 27;316(12):1319

By Angela Morrow, RN Angela Morrow, RN, BSN, CHPN, is a certified hospice and palliative care nurse.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 03 November 2020

US medical and surgical society position statements on physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia: a review

- Joseph G. Barsness 3 ,

- Casey R. Regnier 4 ,

- C. Christopher Hook 1 &

- Paul S. Mueller ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9411-2203 2

BMC Medical Ethics volume 21 , Article number: 111 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

23k Accesses

9 Citations

8 Altmetric

Metrics details

An analysis of the position statements of secular US medical and surgical professional societies on physician-assisted suicide (PAS) and euthanasia have not been published recently. Available statements were evaluated for position, content, and sentiment.

In order to create a comprehensive list of secular medical and surgical societies, the results of a systematic search using Google were cross-referenced with a list of societies that have a seat on the American Medical Association House of Delegates. Societies with position statements were identified. These statements were divided into 5 categories: opposed to PAS and/or euthanasia, studied neutrality, supportive, acknowledgement without statement, and no statement. Linguistic analysis was performed using RapidMinder in order to determine word frequency and sentiment respective to individual statements. To ensure accuracy, only statements with word counts > 100 were analyzed. A 2-tailed independent t test was used to test for variance among sentiment scores of opposing and studied neutrality statements.

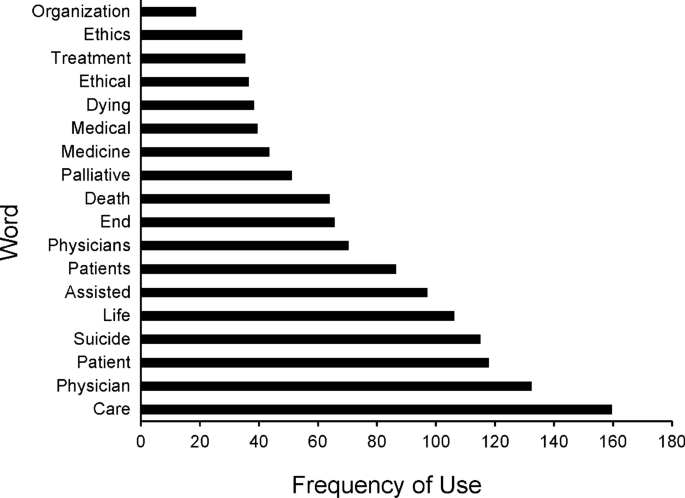

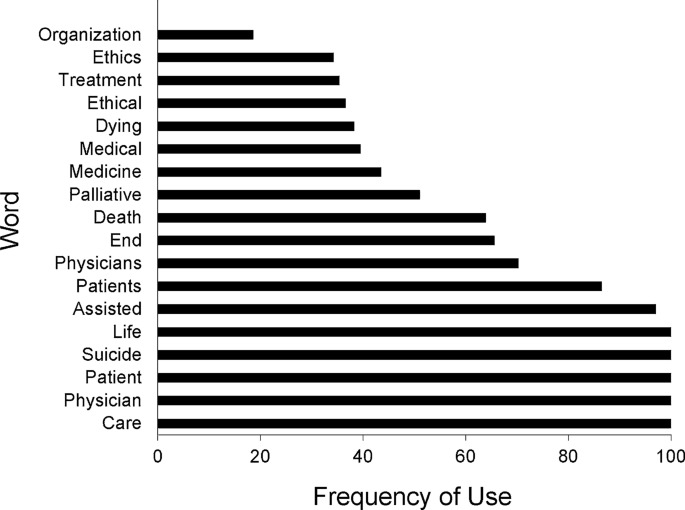

Of 150 societies, only 12 (8%) have position statements on PAS and euthanasia: 11 for PAS (5 opposing and 4 studied neutrality) and 9 for euthanasia (6 opposing and 2 studied neutrality). Although the most popular words used in opposing and studied neutrality statements are similar, notable exceptions exist ( suicide , medicine , and treatment appear frequently in opposing statements, but not in studied neutrality statements, whereas psychologists , law , and individuals appear frequently in studied neutrality statements, but not in opposing statements). Sentiment scores for opposing and studied neutrality statements do not differ (mean, 0.094 vs. 0.104; P = 0.90).

Conclusions

Few US medical and surgical societies have position statements on PAS and euthanasia. Among them, opposing and studied neutrality statements share similar linguistic sentiment. Opposing and studied neutrality statements have clear differences, but share recommendations. Both opposing and studied neutrality statements cite potential risks of PAS legalization and suggest that good palliative care might diminish a patient’s desire for PAS.

Peer Review reports

Physician-assisted suicide (PAS) and euthanasia are highly debated and controversial topics in the United States. In PAS, a patient ingests a drug prescribed by a physician for the purpose of causing the patient’s death, in order to relieve unacceptable symptoms or quality of life. Currently, California [ 1 ], Colorado [ 2 ], Hawaii [ 3 ], Maine [ 4 ], Oregon [ 5 ], Vermont [ 6 ], Washington [ 7 ], and the District of Columbia [ 8 ] have legalized PAS. (The Montana Supreme Court ruled that PAS does not conflict with Montana public policy [ 9 ]) The other US states prohibit PAS and punish it by law [ 10 ]. In euthanasia, a physician (or someone else) administers a lethal drug. Euthanasia is illegal throughout the United States [ 10 ].

Laws concerning PAS, also known as physician-assisted death (PAD), are generally more rigid in the United States than in countries where PAD is legal. For instance, in the Netherlands, PAS and euthanasia are legal for adults (or for persons age 12 through 17 years with parental involvement). Requests for PAD “often come from patients experiencing unbearable suffering with no prospect of improvement. Their request must be made earnestly and with full conviction… However, patients have no absolute right to euthanasia and doctors no absolute duty to perform it” [ 11 ]. Currently, no US state allows PAS for persons younger than 18 years, and PAS is illegal in the absence of a severe physical ailment that will result in natural death within 6 months [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ]. The ethical permissibility of PAS and euthanasia, along with considerations regarding what constitutes patient autonomy in decision-making associated with the dying process, creates an emotionally provocative and divisive debate. The position statements of medical and surgical professional societies concerning PAS and euthanasia may reflect complexities.

The statements of professional societies guide clinicians on various topics, such as disease prevention and management. For PAS and euthanasia, such statements inform, provide multiple (sometimes opposing) perspectives, and advocate for specific positions. Because PAS and euthanasia involve physician action, physicians understandably may turn to their professional societies for guidance on these topics. A comprehensive analysis of such statements issued by secular US medical and surgical professional societies has not been published recently. Therefore, in this cross-sectional study, we determined the number of secular US societies that have position statements about PAS and euthanasia and the positions they have taken. We also analyzed the contents and conducted a linguistic analysis of the statements.

We developed a comprehensive list of secular US medical and surgical professional societies with use of 2 methods. To do so, we first conducted a systematic Google search using the phrase “American […] medical societies,” with the bracket including a name of a specialty derived from the Mayo Clinic directory. An original search was performed for each specialty in the directory, and the respective first 2 Google search pages were analyzed for societies. Second, we obtained a list of specialty societies from the American Medical Association (AMA) website [ 12 ]. This list reflects organizations entitled to a seat in the AMA House of Delegates. It served to provide a cross-reference for our Google search results. In a combination of these 2 methods, a comprehensive list was created of the US specialty-based medical and surgical professional societies.

We determined the positions of these societies on PAS or euthanasia, or both. These positions were organized into 5 categories: supportive, opposed, studied neutrality, acknowledgement without statement, and no statement. Studied neutrality position statements are characterized by an understanding of the practical concerns associated with PAS or euthanasia and the persistent desire of some patients for PAS or euthanasia despite these concerns. The American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine (AAHPM) position statement [ 13 ] exemplifies a studied neutrality statement. To determine whether a society had publicly issued a position statement on PAS or euthanasia, or both, the society’s official website was consulted. If no such statement was available on the website, an email was sent to a society contact listed on the website. If the society website did not provide a statement and no official position statement was publicly available, the society was categorized as having no statement.

For each available position statement, linguistic analysis was performed using a data science software platform (RapidMiner; RapidMiner) [ 14 ]. From each statement, so-called stop words (such as is , a , or the ) and the name of the society were filtered out because these words provided no insights into the intent of the statement authors. The other words were sorted by frequency of use, producing a chart of each statement’s top word choices. In addition, a given statement’s words that were used more than once were processed by a sentiment analysis tool (Twinword; Twinword Inc). This approach relates word choice to emotional attitude and generates a quantitative score of emotional positivity. Medhat et al. [ 15 ] provided a comprehensive survey of sentiment analysis approaches, including a description of the dictionary-based approach used in the present study. To ensure the tool’s generated score was reflective of the statement, we analyzed only the statements with more than 100 words. A mean score was generated for opposing statements and studied neutrality statements. Sentiment scores were compared among the opposing and studied neutrality statements with a 2-tailed independent t test.

Our search methodology identified a total of 150 distinct secular US medical and surgical professional societies (Additional file 1 : Table S1). Of these, only 12 (8%) had position statements regarding PAS or euthanasia, or both (Table 1 ). Eleven societies (7%) had statements on PAS. Of these, 5 (45%) had positions opposing PAS; 4 (36%), positions of studied neutrality; and 2 (18%), acknowledgment of PAS without a position. No society had a statement overtly in support of PAS. Regarding euthanasia, 9 societies (6%) had position statements: 6 (67%), positions opposing euthanasia; 2 (22%), positions of studied neutrality; and 1 (11%), acknowledgement of euthanasia without a position. No society had a statement overtly supporting euthanasia. Three societies have had their position statements published in peer-reviewed journals (American Academy of Neurology [AAN] [ 16 ], American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ 17 ], and American College of Physicians [ACP] [ 19 ]).

The most popular words used in opposing position statements and studied neutrality statements are shown in Figs. 1 and 2 . Suicide , medicine , and treatment appear frequently in opposing statements but not in studied neutrality statements. By comparison, psychologists , law , and individuals appear frequently in studied neutrality statements but not in opposing statements. Otherwise, the words used in these 2 statement types are similar. In linguistic analysis, the mean sentiment score was 0.094 for opposing statements and 0.104 for studied neutrality statements, a nonsignificant difference ( P = 0.90). Of note, Twinword categorizes any sentiment score below − 0.05 as negative and any score above 0.05 as positive [ 28 ]. Thus, given the mean scores in this study, the opposing and studied neutrality statements both used emotionally positive language.

Most popular words in opposing position statements among 150 US medical and surgical professional societies

Most popular words in studied neutrality position statements among 150 US medical and surgical professional societies

From a content standpoint, the opposing statements generally argue that PAS is problematic in practice and in society. The statements of the Society for Post-Acute and Long-term Care Medicine (AMDA), ACP, AMA, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) assert that PAS contradicts the healing role of the physician [ 19 , 20 , 25 , 27 ]. To counter the claim that PAS is a legitimate approach to symptom control in extreme cases, the statements of AMDA, ACP, and the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO) highlight the legal permissibility of palliative sedation. Finally, ACP and NHPCO mention that the US Supreme Court has ruled that no legal right to PAS exists. Studied neutrality statements provide supportive and cautionary arguments concerning PAS. The statements of AAHPM, AAN, and the American Pharmacists Association acknowledge the complexities of the physician–patient relationship [ 13 , 16 , 22 ], and American Psychological Association (APA) acknowledges the social complexities of the medical environment [ 24 ]. Each of these statements emphasizes patient autonomy in decision-making associated with the dying process.

The studied neutrality statements generally support further study of palliative care techniques or physician ethics training, or a combination. Opposing statements (ACP [ 19 ] and AMA [ 20 ]) and studied neutrality statements (AAHPM [ 13 ] and AAN [ 16 ]) warn of potential long-term societal risks associated with a legalization of PAS (e.g., slippery slope ). Opposing statements (AMDA [ 27 ], ACP [ 19 ], and NHPCO [ 26 ]) and 1 studied neutrality statement (APA [ 24 ]) suggest that effective palliative care can diminish a patient’s desire for PAS.

This study has several key findings. First, of 150 secular US medical and surgical professional societies, only 12 (8%) have position statements on PAS and euthanasia: 11 for PAS (5 opposing and 4 studied neutrality) and 9 for euthanasia (6 opposing and 2 studied neutrality). Only 3 of these statements have been published in peer-reviewed journals. Second, opposing and studied neutrality statements use similar linguistic sentiment. Third, although opposing and studied neutrality statements have clear differences, they also share recommendations.

It is unclear why so few US societies have position statements on PAS and euthanasia. A given society’s lack of a statement regarding these topics may be due to numerous factors. For example, large and influential societies such as AMA and ACP have position statements on PAS and euthanasia, potentially inhibiting smaller societies from taking positions or causing the smaller societies to perceive their taking a position as unnecessary or irrelevant. Indeed, in personal communications with representatives of societies that do not have position statements, some representatives directed us to the AMA website (J. Barsness, written communication, June 2018). Society specialty may be another factor. For example, in an email from a specialized surgical society, the contact cited the highly specialized field of its members as a reason for not having a position statement (J. Barsness, written communication, June 2018). These phenomena, along with the controversy surrounding the topics, may discourage a society from creating a position statement about PAS or euthanasia (or both).

No position statement argued in favor of PAS or euthanasia. In consideration of a general desire to avoid controversy, a position of studied neutrality may be perceived by a professional society as the only feasible alternative to an opposing position. The decisions of several societies to acknowledge PAS or euthanasia without taking a position appear similar in intent. Either ethical uncertainty exists in the field or the societies believe the need exists to suppress potentially controversial statements.

Among available position statements, linguistic trends are apparent. Societies with studied neutrality positions emphasize patient autonomy regarding end-of-life decision-making but also respect the physician’s role as a health care provider and recognize the benefit of palliative care [ 16 , 24 ]. The AAN, which takes a studied neutral position, reasons that,

“The Ethics, Law, and Humanities Committee endorses the belief that the primary role of a physician is to prevent and treat disease whenever possible. At the same time, the committee strongly endorses the provision of palliative care to alleviate suffering in patients with illnesses that are unresponsive to disease-specific treatments” [ 16 ].

Studied neutrality statements typically call for rigorous ethical training and further study of palliative care and PAS. This call leaves open the possibility of further analysis [ 17 ]. The APA, taking a studied neutrality position, reasons, “[We] encourage psychologists to obtain training in ethics (e.g., medical ethics, professional codes of conduct) in the context of diversity, as applied to palliative and end-of-life decisions and care” [ 24 ].

Societies with opposing statements view PAS as contrary to the physician’s role in the general US society, do not view death as a right, and view that patient autonomy is an insufficient reason for legalization of PAS. The statements of the AMDA, ACP, AMA, and ASA posit that PAS contradicts the role of a physician [ 19 , 20 , 25 , 27 ]. The ACP position statement provides illustrative reasoning: “Physician-assisted suicide requires physicians to breach specific prohibitions as well as the general duties of beneficence and nonmaleficence. Such breaches are viewed as inconsistent with the physician’s role as healer and comforter” [ 19 ]. Unsurprisingly, the opposing statements do not mention further study of PAS. Statements that oppose euthanasia follow similar reasoning.

Some opposing statements (of AMDA, ACP, and NHPCO) reference the permissibility of palliative sedation to counter the claim that PAS is a legitimate symptom management approach in the case of extreme discomfort [ 19 , 26 , 27 ]. In such cases, patients should receive aggressive palliation. AMDA reasons, “AMDA supports aggressive treatment toward relieving the pain, anxiety, depression, emotional isolation, and other physical symptoms that can accompany the dying process even if the unintended result of such treatment may hasten the patient’s death” [ 27 ]. The ACP and NHPCO statements also highlight the US Supreme Court’s prior ruling that there is no right to die (or PAS) in the United States [ 19 , 26 ].

Of note, studied neutrality statements (AAHPM and AAN) [ 13 , 16 ] and opposing statements (ACP and AMA) [ 19 , 20 ] warn of a slippery slope of long-term risks that PAS legalization may incur. The ACP opposing statement says, “Although the ACP’s fundamental concerns are based on ethical principles, research suggests that a ‘slippery slope’ exists in jurisdictions where physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia are legal” [ 19 ]. The AAHPM’s studied neutral statement says, “Such a change risks unintended long-range consequences that may not yet be discernible, including effects on the relationship between medicine and society” [ 13 ]. Such long-range consequences include broadened use of PAS for nonterminal conditions and use of PAS in favor of palliative care. Additionally, the studied neutrality and opposing statements suggest that effective palliative care can diminish a patient’s desire for PAD [ 19 , 24 , 27 , 29 ]. The AAN’s studied neutrality statement says,

“[The committee] expresses support for improved availability of palliative care services, palliative care education for AAN members, and palliative care research intended to identify more effective means to alleviate refractory suffering of dying patients. By doing so, it hopes to minimize future patient interest in hastened death” [ 16 ].

The language of position statements correlates with the position taken by the societies. For instance, studied neutrality statements refrain from the word suicide and instead use such terms as hastened death or assisted death [ 13 , 16 , 24 ]. This use of language is justified in the AAN statement as a means of reducing stigma associated with PAS [ 16 ]. Alternative terminology regarding PAS has been actively considered in the literature [ 30 ]. In contrast, the ACP opposing statement states a rationalization of use of the word suicide as not being derogatory and aiding in clarity in the discussion of the topic (e.g., in contrast to “physician aid in dying,” which could refer to palliative care, terminal sedation, PAS, and euthanasia) [ 19 ]. Unsurprisingly, statements that oppose PAS or euthanasia (or both) use the word suicide more frequently [ 19 , 20 , 21 , 27 , 29 ]. In contrast, studied neutrality statements use psychologists , law , and individuals more frequently than opposing statements—likely a reflection of the procedures used to request PAS and the emphasis on patient autonomy in association with PAS. That said, the most popular words used in the opposing statements and studied neutrality statements are similar.

Statements have considered the culturally and historically negative connotations of the term suicide [ 19 ]. Recognizing these connotations, we sought to explore whether the opposing statements’ preference for referring to PAS as a suicide and studied neutrality statements’ preference for alternative terms such as assisted death indicates a statement’s comprehensive use of emotionally positive or negative language. Therefore, we extended the linguistic analysis by exploring possible associations between linguistic sentiment and statement position through comparison of mean sentiment scores across position categories. Although studied neutrality statements commonly use phrases such as assisted death in place of suicide , our linguistic analysis showed similar mean sentiment scores for studied neutrality statements and opposing statements. Furthermore, both opposing and studied neutrality statements tended to use emotionally positive language.

Nonetheless, our analysis and findings provide no insight into the rhetorical decision to use the label suicide or an alternate. Rather, our findings suggest that use of suicide or an alternate term such as assisted death does not indicate that a position statement intentionally uses emotionally positive or negative language.

Limitations

A limitation of the present analysis is the small number of position statements of the organizations. Corpus-based sentiment analysis would provide a better understanding of author intent in the statements because this approach has the ability to consider phrase context more thoroughly [ 15 ]. That said, we did not use this type of analysis because the authors of these position statements were unlikely to use techniques such as sarcasm or irony. In addition, we did not include position statements from societies with religious affiliations, some of which have large memberships (e.g., Christian Medical and Dental Associations [ 31 ]). Because our study focused on position statements of US professional societies, we intentionally did not include statements from non-US–based societies. Nonetheless, given the variability of perspectives and laws on PAS and euthanasia globally, a study comparing US with non-US statements should be considered.

Only a dozen secular US medical and surgical professional societies have position statements on PAS and euthanasia, and only 3 of these statements have been published in peer-reviewed journals. The reasons for these small numbers are unclear but may be related to the controversial nature of the topics, the positions of large and influential societies, and the relevancy of the topics for specific specialty societies.

Aside from the use of the words suicide , medicine , and treatment in opposing statements and the words psychologists , law , and individuals in studied neutrality statements, the most popular words used in opposing and studied neutrality position statements are similar. Use of the word suicide or assisted death does not appear to indicate a statement’s comprehensive use of emotionally positive or negative language.

Opposing statements generally claim PAS contradicts the healing role of the physician and that alternative approaches to symptom control exist for extreme cases (e.g., palliative sedation). Studied neutrality statements highlight patient autonomy in decision-making associated with the dying process. The opposing statements and the studied neutrality statements cite potential long-term societal risks associated with legalization of PAS and suggest that effective palliative care can diminish a patient’s desire for PAS.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine

American Academy of Neurology

American College of Physicians

American Medical Association

Society for Post-Acute and Long-term Care Medicine

American Psychological Association

American Society of Anesthesiologists

National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization

Physician-assisted death

- Physician-assisted suicide

End of Life Option Act, ABX2-15 (2016).

Proposition 106, End of Life Options Act (2016).

Our Care, Our Choice Act (2019).

Maine Death With Dignity Act. In: 2019.

Oregon Death With Dignity Act (1994).

Act 39, Vermont Patient Choice and Control at the End of Life Act (2013).

Washington Assisted Death Initiative, Initiative 1000 (2008).

Death With Dignity Act of 2015.

Baxter v Montana , 27 Jan 2009 (2009).

Assisted Suicide Laws in the United States. Patients Rights Council. https://www.patientsrightscouncil.org/site/assisted-suicide-state-laws/ . Updated 6 Jan 2017. Accessed 16 Apr. 2019.

Euthanasia, assisted suicide and non-resuscitation on request. https://www.government.nl/topics/euthanasia/euthanasia-assisted-suicide-and-non-resuscitation-on-request . Accessed 16 Apr. 2019.

Member Organizations of the AMA House of Delegates. American Medical Association. https://www.ama-assn.org/house-delegates/hod-organization/member-organizations-ama-house-delegates . Accessed 16 Apr. 2019.

Statement on Physician-Assisted Dying. American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. https://aahpm.org/positions/pad . Published 2016. Accessed 16 Apr. 2019.

Verma T, Renu, Gaur D. Tokenization and filtering process in RapidMiner. Int J Appl Inform Syst. 2014;7(2):16–8.

Google Scholar

Medhat W, Hassan A, Korashy H. Sentiment analysis algorithms and applications: a survey. Ain Shams Eng J. 2014;5(4):1093–113.

Article Google Scholar

Russell JA, Epstein LG, Bonnie RJ, et al. Lawful physician-hastened death: AAN position statement. Neurology. 2018;90(9):420–2.

Committee on Ethics. Committee opinion no. 617: end-of-life decision making. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(1):261–7.

Vizcarrondo FE. Neonatal euthanasia: the Groningen Protocol. Linacre Q. 2014;81(4):388–92.

Snyder Sulmasy L, Mueller PS, Ethics, Professionalism and Human Rights Committee of the American College of Physicians. Ethics and the Legalization of Physician-Assisted Suicide: An American College of Physicians Position Paper. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(8):576–78.

Physician-Assisted Suicide. American Medical Association. Code of Medical Ethics Opinion 5.7 Web site. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/ethics/physician-assisted-suicide . Accessed 16 Apr. 2019.

Euthanasia. American Medical Association. Code of Medical Ethics Opinion 5.8 Web site. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/ethics/euthanasia . Accessed 16 Apr. 2019.

Physician Assisted Suicide. American Pharmacists Association. APhA Policy Manual Web site. https://www.pharmacist.com/policy-manual?key=suicide&op=search . Accessed 16 Apr. 2019.

Position Statement on Medical Euthanasia. American Psychiatric Association. APA Official Actions Web site. https://www.psychiatry.org/home/search-results?k=euthanasia . Published 2016. Accessed 16 Apr. 2019.

Resolution on Assisted Dying. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/about/policy/assisted-dying-resolution . Published 2017. Accessed 16 Apr. 2019.

Statement on Physician Nonparticipation in Legally Authorized Executions. American Society of Anesthesiologists. Standards and Guidelines Web site. https://www.asahq.org/standards-and-guidelines/statement-on-physician-nonparticipation-in-legally-authorized-executions . Published 2006. Updated 26 Oct. 2016. Accessed 16 Apr. 2019.

Commentary and Resolution on Physician Assisted Suicide. National Hospice & Palliative Care Organization. https://www.nhpco.org/sites/default/files/public/PAS_Resolution_Commentary.pdf . Published 2005. Accessed 16 Apr. 2019.

Position Statement on Care at the End of Life. American Medical Directors Association The Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine. https://paltc.org/amda-white-papers-and-resolution-position-statements/position-statement-care-end-life . Published 1997. Accessed 16 Apr. 2019.

Shih J. Interpreting the Score and Ratio of Sentiment Analysis. Twinword. https://www.twinword.com/blog/interpreting-the-score-and-ratio-of-sentiment/ . Accessed 16 Apr. 2019.

Kirk TW, Mahon MM, Palliative Sedation Task Force of the National H, Palliative Care Organization Ethics C. National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO) position statement and commentary on the use of palliative sedation in imminently dying terminally ill patients. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2010;39(5):914–23.

Quill TE, Back AL, Block SD. Responding to patients requesting physician-assisted death: physician involvement at the very end of life. JAMA. 2016;315(3):245–6.

Physician Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia. Christian Medical & Dental Associations. https://cmda.org/physician-assisted-suicide/ . Accessed 17 Apr. 2019.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

This study had no funding source.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Division of Hematology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA

C. Christopher Hook

Department of Internal Medicine, Mayo Clinic Health System–Franciscan Healthcare in La Crosse, 800 West Ave S, La Crosse, WI, 54601, USA

Paul S. Mueller

Hamline University, St. Paul, MN, USA

Joseph G. Barsness

Augsburg University, Minneapolis, MN, USA

Casey R. Regnier

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

JB contributed to study design, the collection and analysis of position statement data, and the writing and editing of the manuscript. CR contributed to position statement data collection and made major contributions to data organization. CH made contributions to data collection and organization as well as manuscript editing. PM contributed to and oversaw study design, data collection, position statement analysis, and the writing and editing of the manuscript. All authors have read, approved, and are accountable for the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Paul S. Mueller .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication.

Not applicable (see cover letter).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1. table s1.

: Positions on PAS and Euthanasia of all Identified US Medical and Surgical Societies.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Barsness, J.G., Regnier, C.R., Hook, C.C. et al. US medical and surgical society position statements on physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia: a review. BMC Med Ethics 21 , 111 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-020-00556-5

Download citation

Received : 21 August 2019

Accepted : 28 October 2020

Published : 03 November 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-020-00556-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Assisted death

BMC Medical Ethics

ISSN: 1472-6939

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Oregon’s Death with Dignity Law: a Complex Choice

This essay about Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act, enacted in 1997, which allows terminally ill individuals meeting strict criteria to choose physician-assisted death. It outlines the procedural intricacies, emphasizing safeguards to ensure autonomous decision-making, including verbal and written appeals, confirmation of diagnosis and mental competence, and alternative options like palliative care. Advocates highlight it as a means of individual self-determination and compassion, while detractors raise concerns about potential misuse and ethical dilemmas. Overall, the Act represents a structured legal framework balancing personal autonomy with robust safeguards in end-of-life decision-making.

How it works

The discourse surrounding end-of-life decisions delves into the profoundly intimate and often contentious realm, with Oregon emerging as a focal point since the implementation of the Death with Dignity Act in 1997. This legislative stride grants terminally ill individuals meeting stringent criteria the agency to electively conclude their lives through physician-assisted demise. Comprehending the procedural intricacies and robust prerequisites underpinning Oregon’s approach sheds light on its nuanced handling of such sensitive deliberations, underscored by the intricate interplay between personal autonomy and ethical imperatives.

Oregon’s statute extends exclusively to individuals afflicted with terminal ailments, where prognosis forecasts a life expectancy of six months or less. A meticulously outlined procedure ensues, aimed at safeguarding the integrity of decisions, ensuring they are made autonomously devoid of undue influence or coercion. Eligible patients must attain the threshold of adulthood (18 years or older), hold legal residency in Oregon, and exhibit capacity to articulate and articulate their healthcare preferences.

Initiating the process mandates a patient to articulate two verbal appeals to their attending physician, spaced by an interval of at least 15 days. This stipulated “respite” duration endeavors to afford contemplative space for individuals to ruminate upon their resolution. Simultaneously, the patient must furnish a written plea endorsed by two impartial witnesses, with one barred from familial ties or any entitlement to the patient’s estate, a precautionary measure aimed at mitigating undue sway.

Confirmation of the terminal diagnosis and patient’s decisional competence rests within the purview of the attending physician, while an independent consultant validates both the diagnosis and the patient’s mental acuity. Suspicions concerning impaired judgment attributable to psychiatric disorders or melancholic disposition prompt referral for psychological assessment, a precautionary measure aimed at obviating the influence of ancillary factors such as despondency upon decision-making faculties.

Upon ascertaining eligibility and duly documenting the solicitations, the attending physician prescribes medication, typically a potent barbiturate. However, it devolves upon the patient to self-administer the medication, underscoring the essence of autonomous volition. Concurrently, legal mandates necessitate healthcare providers to furnish insights into viable alternatives such as palliative care and hospice, thus ensuring patients are apprised of the full spectrum of options.

Despite the embedded safeguards, Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act remains enmeshed in contention. Advocates extol its virtue as a conduit for individual self-determination and the conferment of dignity upon end-of-life decisions. They contend that prolonging the suffering of terminally ill individuals contravenes principles of compassion, advocating for the provision of a compassionate recourse for those who meet the criteria. Moreover, empirical data from Oregon’s Department of Human Services illuminate a notable proportion of patients eschewing the prescription, indicative of the palliative effect engendered by the mere acknowledgment of the option.

Conversely, detractors raise apprehensions regarding potential misuse or ethical quandaries. They apprehend susceptibility among vulnerable patients to coercion into precipitating their demise, or the prospect of underdiagnosis, wherein conditions susceptible to amelioration via enhanced treatment or pain management might be overlooked. Moreover, concerns pertaining to the disparate impact of socio-economic disparities or limited access to quality healthcare upon certain demographics underscore the imperative for fortified safeguards or enhanced palliative interventions.

In summation, Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act delineates a structured legal framework catering to terminally ill patients contemplating end-of-life alternatives consonant with their philosophical ethos. It constitutes a momentous juncture laden with profound personal import, meticulously regulated to curtail potential abuses whilst empowering those grappling with terminal ailments to navigate their suffering on their own terms. Despite disparate ethical outlooks on physician-assisted demise, the legislation stands as a paradigmatic exemplar of states’ capacity to grapple with sensitive healthcare issues, foregrounding reverence for autonomy amidst robust safeguards.

Cite this page

Oregon's Death with Dignity Law: A Complex Choice. (2024, May 12). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/oregons-death-with-dignity-law-a-complex-choice/

"Oregon's Death with Dignity Law: A Complex Choice." PapersOwl.com , 12 May 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/oregons-death-with-dignity-law-a-complex-choice/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Oregon's Death with Dignity Law: A Complex Choice . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/oregons-death-with-dignity-law-a-complex-choice/ [Accessed: 14 May. 2024]

"Oregon's Death with Dignity Law: A Complex Choice." PapersOwl.com, May 12, 2024. Accessed May 14, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/oregons-death-with-dignity-law-a-complex-choice/

"Oregon's Death with Dignity Law: A Complex Choice," PapersOwl.com , 12-May-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/oregons-death-with-dignity-law-a-complex-choice/. [Accessed: 14-May-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Oregon's Death with Dignity Law: A Complex Choice . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/oregons-death-with-dignity-law-a-complex-choice/ [Accessed: 14-May-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

COMMENTS

Thesis Statement For Physician Assisted Suicide. The Right to Die 1) Introduction a) Thesis statement: Physician assisted suicide offers patients a choice of getting out of their pain and misery, presents a way to help those who are already dead mentally because of how much a disease has taken over them, proves to be a great option in many ...

depression or other mental impairments, these laws require the attending physician 1 This is a controversial topic, evoking broad ethical debate within the medical profession, and within society at large. The language used---ranging from "physician-assisted suicide (PAS)" and "euthanasia" to

Physician-assisted suicide (PAS), also known as physician aid-in-dying (AID), is one of the most contentious ethical issues facing medicine today. The American Medical Association (AMA) states that, "Physician-assisted suicide occurs when a physician facilitates a patient's death by providing the necessary means and/or information to enable ...

A THESIS . Presented to the Department of Planning, Public Policy and Management ... state in the country to legalize physician-assisted death policy. The successful campaign . 3. of the Oregon Death with Dignity Act in November 1994 passed and defeated a repeal effort in November 1997. Oregon has since been an example to other states when

The right to legally end your own life is a heavily debated issue. Physician-assisted death brings up moral, ethical, and legal questions. Although September is designated National Suicide ...

Physician-assisted suicide has been a heated topic for many years and is still ongoing. Many are concerned with the ethics, or lack thereof, associated with the practice. ... actual thesis in an organized and coherent manner could take a few months, along with the time it takes to revise, add, and/or edit. When presented at Scholars Day, the ...

Abstract. Health care is intentionally moving in a direction which emphasizes patient autonomy. This mentality has caused some patients to seek control over their own death when faced with a terminal illness. Claiming the right to "death with dignity," patients exercise the method of physician assisted suicide in order to avoid the ...

Assisted dying: The motivations, benefits and pitfalls of hastening death. As physician-assisted dying becomes more available, psychologists are finding opportunities to study people's motivations and the potential benefits and harms of aid in dying. By Kirsten Weir. December 2017, Vol 48, No. 11. Print version: page 26. 13 min read

assisted suicide (PAS) is defined as a "physician providing, at the patient's request, a. prescription for a lethal dose of medication that the patient can self-administer by ingestion, with. the explicit intention of ending life" (American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 2016).

In the past decade, Physician Assisted Suicide (PAS) has emerged as a heavily contested policy issue for state governments. A central political argument against PAS claims that access to PAS practices enables terminally ill individuals—who were once statistically unlikely to commit suicide—to develop an increased risk for suicidal action.

A NEW JUSTIFICATION FOR PHYSICIAN-ASSISTED SUICIDE BY WILLIAM CLYDE FRANTZ A Thesis Submitted to The Honors College In Partial Fulfillment of the Bachelors Degree With Honors in Philosophy THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA MAY201 1 Approved by: Dr. Michael Gill Department of Philosophy . STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial ...

Opinion 5.7. Physician-assisted suicide occurs when a physician facilitates a patient's death by providing the necessary means and/or information to enable the patient to perform the life-ending act (e.g., the physician provides sleeping pills and information about the lethal dose, while aware that the patient may commit suicide).

Bando, Catherine, "Assisted Death: Historical, Moral and Theological Perspectives of End of Life Options" (2018). LMU/LLS Theses and Dissertations. 513. https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/etd/513. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School.

Use of the word suicide or assisted death does not appear to indicate a statement's comprehensive use of emotionally positive or negative language. Opposing statements generally claim PAS contradicts the healing role of the physician and that alternative approaches to symptom control exist for extreme cases (e.g., palliative sedation).

PAD is a physician-provided medication or prescription at the patient's explicit request that the patient intends to use to end his or her life. 6 The laws that permit PAD generally model the Oregon Death With Dignity Act passed in 1997. Laws in Vermont, California, and Colorado specifically state that the option of PC must be mentioned to the patient 7-10; otherwise, the standard language ...

Physician aid in dying is a controversial subject raising issues central to the role of physicians. According to the American Medical Association, it occurs when a physician provides "the necessary means and/or information" to facilitate a patient's choice to end his or her life [].This essay's authors hold varying views on the ethics of aid in dying; thus, the essay explores the ...

There is a clear distinction between a physician allowing a terminally ill person to decline treatment and to die in the natural course of his or her terminal illness, on one hand, and a physician prescribing PAS/PAD, on the other. 9-11 When care is appropriately withdrawn, the course of the terminal illness is the cause of death. If a medication is prescribed to cause death, the prescription ...

As of June, 9th 2016 California became the fifth state to allow physician - assisted suicide. The California's End of Life Option Act authorizes any individual 18 years of age or older, who has been diagnosed as terminally ill and fits specific criteria, to solicit administration of assisted dying drugs at the hands of his/her attending ...

The debate over the ethics and legality of physician-assisted suicide (PAS) is a long-standing and highly charged one. Notable legal challenges in the United States include Washington v. Glucksberg and Vacco v. Quill, both in 1997 and both of which upheld bans on PAS in Washington State and New York. On the opposite side of the debate, Oregon ...

In the case of physician-assisted suicide, the medical issue must place the patient in excessive inevitable pain, such as incurable cancers and mental diseases. The second qualification is the patient must be aware of their specific diagnosis and they must consent to the treatment option necessary (Welie 2014). ... Assisted Suicide Thesis ...

This article is a complement to "A Template for Non-Religious-Based Discussions Against Euthanasia" by Melissa Harintho, Nathaniel Bloodworth, and E. Wesley Ely which appeared in the February 2015 Linacre Quarterly.Herein we build upon Daniel Sulmasy's opening and closing arguments from the 2014 Intelligence Squared debate on legalizing assisted suicide, supplemented by other non-faith ...

Weak thesis: This paper will explore the legalization of physician-assisted suicide in California. One Revision: Physician-assisted suicide, which became legal in California in October 2015, should remain legal because of x and y. (Signals the main points for the reader.) And remember: your thesis should be written as a statement, not a question.

An analysis of the position statements of secular US medical and surgical professional societies on physician-assisted suicide (PAS) and euthanasia have not been published recently. Available statements were evaluated for position, content, and sentiment. In order to create a comprehensive list of secular medical and surgical societies, the results of a systematic search using Google were ...

This essay about Oregon's Death with Dignity Act, enacted in 1997, which allows terminally ill individuals meeting strict criteria to choose physician-assisted death. It outlines the procedural intricacies, emphasizing safeguards to ensure autonomous decision-making, including verbal and written appeals, confirmation of diagnosis and mental ...