An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Anal Verbal Behav

On the relationship between speech and writing with implications for behavioral approaches to teaching literacy

Two theories of the relationship between speech and writing are examined. One theory holds that writing is restricted to a one-way relationship with speech—a unidirectional influence from speech to writing. In this theory, writing is derived from speech and is simply a representation of speech. The other theory holds that additional, multidirectional influences are involved in the development of writing. The unidirectional theory focuses on correspondences between speech and writing while the multidirectional theory directs attention to the differences as well as the similarities between speech and writing. These theories have distinctive pedagogical implications. Although early behaviorism may be seen to have offered some support for the unidirectional theory, modern behavior analysis should be seen to support the multidirectional theory.

Full text is available as a scanned copy of the original print version. Get a printable copy (PDF file) of the complete article (2.2M), or click on a page image below to browse page by page. Links to PubMed are also available for Selected References .

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Goldiamond I. Literary behavior analysis. J Appl Behav Anal. 1977 Fall; 10 (3):527–529. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, the third dimension. on the dichotomy between speech and writing.

- Faculté des Lettres, University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland

This paper introduces a more complex and refined articulated view than the classic and simple dichotomy of linguistic production. According to the traditional doxa, what is linguistically articulated is either spoken or written. Forms of written language have previously been considered a secondary representation of spoken forms and, at least in the alphabetic system, the only properly linguistic form. I argue that there exists a third dimension of language, which is internal. This internal form is lexically, phonetically and grammatically articulated, without being spoken in a proper sense, but which can be seen as the pre-condition for both spoken and written production. In other words, linguistic production does not necessarily imply the presence of two interacting speakers (or writers/readers). Production can be seen as the simple effect of an internal activity, and can be described without reduction to spoken or written forms. A consideration of this third dimension in a systematic way could enrich and strengthen approaches to many types of texts and help to productively integrate the traditional schemes adopted in Sociolinguistics, Historical Linguistics, Philology, Literary Criticism, and Pragmatics.

Introduction

Speech in classical linguistic doctrine: saussure.

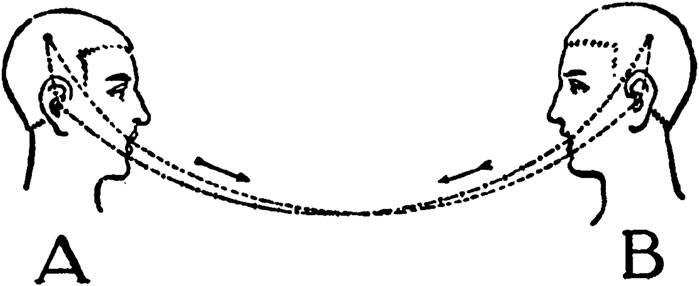

According to Saussure’s Cours de linguistique générale (from here on CLG , 27 Saussure, 1967 ), the act of parole is an individual one, but is realized as the minimum requirement of two “people who are speaking”:

“Pour trouver dans l’ensemble du langage la sphère qui correspond à la langue, il faut se placer devant l’acte individuel qui permet de reconstituer le circuit de la parole. Cet acte suppose au moins deux individus; c’est le minimum exigible pour que le circuit soit complet. Soient donc deux personnes, A et B, qui s’entretiennent”: Figure 1 .

FIGURE 1 . “Le circuit du langage” (from Saussure 1967 : CLG 60).

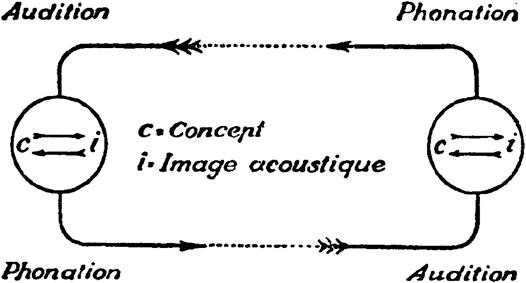

Thus, ideographic systems of writing directly represent the idea of words, and phonetic systems represent their sound ( CLG 47 ss.). Consequently (alphabetic) writing is the representation of the sounds of words, which is manifested in the act of a closed circuit shown above, which assumes two interlocutors. According to Saussure, there exists a connection from a concept to an acoustic image, then to phonation, and finally in inverse order, from a reassociation of the sound to an acoustic image, and then back to the concept Figure 2 .

FIGURE 2 . Phases of saussurean Circuit ( Saussure 1967 : CLG 60).

The written dimension is subordinated, both ontogenetically and phylogenetically, with respect to speech (the latter is identified with language tout court , with an almost imperceptible but crucial deviation). One reads in the CLG 45:

‘Langue et écriture sont deux systèmes de signes distincts; l’unique raison d’être du second est de représenter le premier; l’objet linguistique n’est pas défini par la combinaison du mot écrit et du mot parlé; ce dernier constitue à lui seul cet objet. Mais le mot écrit se mêle si intimement au mot parlé dont il est l’image, qu’il finit par usurper le rôle principal; on en vient à donner autant et plus d’importance à la représentation du signe vocal qu’à ce signe lui-même. C’est comme si l’on croyait que, pour connaître quelqu’un, il vaut mieux regarder sa photographie que son visage ( CLG 45).’

Typical of pre-nineteenth century linguistics was the centrality of writing and written language. Twentieth-century linguistics, then, pushed writing to one side, focusing on the only other perceived dimension, speech. Bloomfield’s famous statement (1935, p. 21) “Writing is not language” became necessarily integrated, in the American structuralist’s perspective, with the notion that the spoken dimension is the only one which duly qualifies as language .

From CLG 45 one can read an entire history of twentieth-century linguistics, which appears to have always taken for granted the dependence of written language on spoken language. This perspective is succinctly highlighted by Martinet, (1972) , p. 70): “a graphic code exists, writing, but apart from this there is no other code: there is language”, obviously referring to speech. There exists almost no twentieth-century treatize which does not define spoken and written language in terms of a dichotomy, and as being the primary (originally, only) and secondary (derived from the first) dimensions of linguistic activity respectively. And there is no work, even among the most recent and attentive studies to questions of the relationship between writing and speech, which does not tend to consider speech simply as the motor of innovation of writing, excluding interference or the role of any other dimension.

Ultimately, according to the model hypothesized by Saussure, spoken language is crucially super-individual. It presupposes at least two individuals, as discussed above. Alphabetic written language is simply a secondary (and often distorted) representation of spoken language, which constitutes the only object of linguistics properly understood (that is, the linguistics of langue , as per the explanation in CLG 38–39).

Twentieth-Century Criticism of the Dichotomy Between Speech and Writing

The dichotomy between speech and writing is discussed at several points during the 20th century. Strictly speaking, this dichotomy is not one of the greatest Saussurian dichotomies, given that Saussure does not theorize it with the same articulation with which he outlines other oppositions, such as those between Langue and Parole, or even Diachrony and Synchrony etc. One reason may be due to the fact that, from his point of view, the written dimension is simply external to the field of linguistics. Already from a structuralist perspective à la Hjelmslev (1966, pp. 131–32), in fact, we see how written and spoken language are not derived from each other, but are simply two manifestations of the same form. In this account, the priority for speech over writing had already been questioned—not from a historical point of view, but from an axiological and epistemological one.

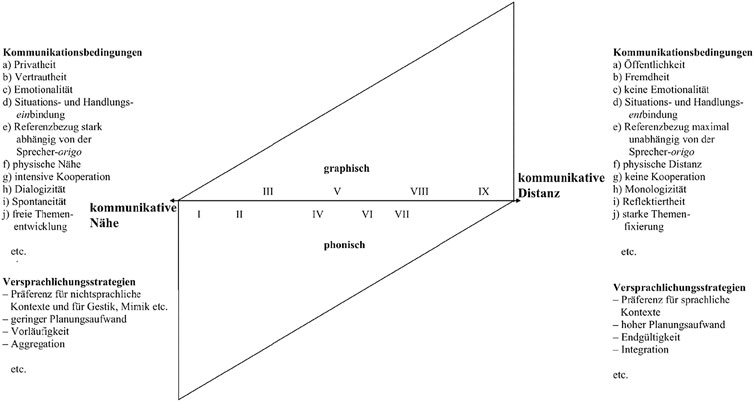

Among the most important discussions, there has been some attempt to refine the sharpness of the boundary between the two fields, highlighting the elements of continuity and, in part, intersection. This is the case of the Koch-Österreicher (1990) model: to the simple distinction between written language vs. spoken language, the two German Romanists oppose a model based on the concepts of distance vs. closeness. These concepts allow, on the one hand, a further realization of the sociolinguistic aspect of situations devoid of writing, and on the other hand, allow us to frame those phenomena which are clearly mixed or hybrid.

The Koch-Österreicher model proposes a scale of distance (and of the quantity of interlocutors included by the single linguistic act) whose minimum value is in fact 1. The conditions of communication are identified, in the first instance, in the Grad der Öffentlichkeit («für den die Zahl der Rezipienten—vom Zweiengespräch bis zum hin zur Massenkommunikation», Koch-Österreicher 2011, p. 7, Italics mine). In short, as in the Saussurian model, there does not appear to be an inferior degree with respect to communication when two are present.

Linguistics in the late 20th century elaborated the concept of diamesic variation (a term invented by Mioni 1983 , extending a series of analogous categories from Coseriu). But it struggled to demonstrate that there exist various “intermediate” positions between these two poles. Apparently, the poles are not united (as instead occurs for similar polarities, such as the classic dimensions of sociolinguistic variation).

A further contribution to overcoming the exclusive and rigid dichotomy between writing and speech was provided by the twentieth-century development of studies on sign language (SL). It is thanks to this line of research and the continued appreciation of SL as an alternative channel to spoken and written language, that traditional expressions such as “spoken or written language” are often substituted with other ones. In recent studies, a trinomial “spoken, signed or written language” (for example, as recently as in Haspelmath 2020 , p. 2) has entered the literature. In short, one finds an all-encompassing category of verbal language in addition to the traditional dichotomy of spoken/written language. This category synthesizes, rather than supersedes, the old contraposition (notwithstanding the distinct nature of signed languages, which can be acquired spontaneously, with respect to writing, and which are the fruit of cultural transmission and learning).

In sum, twentieth-century linguistics approaches the polarities of written vs. spoken language both in a theoretical perspective as well as in a specifically sociolinguistic perspective. Linguistics aimed to overcome this conception as an exclusive dichotomy, placing greater emphasis on those elements of continuity which overlap. This approach was favored also by the emergence of new methodologies of communication. A further contribution to superseding the written/spoken duality was provided by research on sign language: dealing, as it does, with phenomena that cannot be reduced to either category, nor to either one of the polarities.

The Internal Text of G. R. Cardona

Among the few contributions which properly highlighted the linguistic question posed by an internal text, and taking inspiration from both literary and non-literary texts, is the work of Giorgio Raimondo Cardona, (1986 , reprinted Cardona, 1990 ). Published 2 years before his unexpected and premature death, the article deals with “mental text” as an indispensable premise for the production of any oral, but especially written, text.

Let us consider in particular one of the crucial passages of Cardona’s essay: “There is no analytic thread (whatever its itinerary may be) that can be exempt from choosing internal discourse as a point of departure: apart from some cases of automatic writing or trance or similar, no external communicative activity can be disregarded from endophasic, mental and communicative discourse”.

Cardona, (1986) begins from an examination of the literary manifestations of internal speech, bringing to light suggestions from the field of semiotics (and particularly from Lotman et al., 1975 ). He focuses on criticism from genetics and on twentieth-century variationist linguistics, before moving to what he considers a particular type of text, understood as a preparatory and evolving phase that precedes the development in written form, but also its spoken realization. In this way, “the various genres, written and spoken, open up into a natural typology, widening to become waves from the nucleus of internal discourse”.

Another fundamental passage from Cardona consists in recognizing internal discourse (or “interior text”) as the essential absence of a pragmatic dimension, beyond an extreme simplification of syntax (“in one’s thought for oneself, the combination can be reduced to its minimum, the mental nuclei find their minimal linguistic expression. It can, at times, be substituted or integrated by images, as per the manuscripts of Leonardo da Vinci”). Cardona’s examples usefully extend to textual and typological instances that are quite varied.

Cardona’s gifted intuition has been recognized by Italian studies of general linguistics, by history of the Italian language, and literary criticism, which occasionally quote him (among the most important studies, see D’Achille 1990 : 18, who dedicates a note to him). But it has never been explored in full and, in fact, it has not led to any substantial new analysis in the general study of written and spoken language. Significant, for example, is the absence of any reference to him in the best work of German Romance studies in the new century, from Kabatek (2000) to the second edition of Koch-Österreicher (2011) . Furthermore, Cardona’s work does not appear to have been recognized even by contemporary French linguistics, which has, on several occasions, returned to the notions of langage and parole intérieur(e). This includes within the traditional studies of psychology, which we will take up below (exemplary in this regard is Bergounioux 2001 ). In terms of Italian linguistics, which has always been attentive to the social dimension of language and its recent evolution, historians of the Italian language have concentrated mainly on the opposition between spoken and written speech (see, for example, the studies following the work of Giovanni Nencioni, later published in Nencioni 1983 ). Up until now, Cardona’s work has mainly influenced the realm of literature (for example, Bologna 1993 ).

The Perspective From Generative Linguistics

Linguistics in the past few decades has opened up a debate with particular vigor, especially in the field of studies on the origin of language and its biological foundations, which can be summarily characterized by the following two extremes: 1) language is studied primarily as an instrument of communication; 2) language is studied primarily as a form of organization of thought.

Generative grammar resolutely derives from 2) within a theory of externalization. This theory identifies the human specificity of language in its internal, computational (syntactic) capacity (that is, in what Chomsky calls internal language, I-language) and not in the interaction between it and the materiality of phonation. As for the executive function of neurons, the human species shares this aspect with various other animals (hence the computational-syntactic capacity is exclusive of homo, cf. for example Berwick, 2013 ). Generally speaking, only syntactic characteristics are assigned to I-language, dealing as it does with a computational system, that is, with the product of a mental apparatus.

In a partially complementary position, a recent string of neurolinguistic studies (for example, the various works by A. Moro and others, cf. Magrassi et al., 2015a ) has made it possible to observe the cerebral traces of the mental representation of words with the tools from clinical observation. These observations occur not just during the listening phase, but also in the phase of production. In particular, they are visible in those areas of the encephalon that are crucially non acoustic, such as the Broca area. This has highlighted the many affinities between spoken language and “thought language”: the latter showing a great number of elements in common with the former, and thus comprising something similar to what Saussure had already called the acoustic image of words. In short, to summarize with an efficient phrase from Moro, (2016) , p. 89: “when we think without speaking, we are putting the sounds of words in our thoughts”.

One consequence of the theories and of the hypotheses (even though partially divergent) of what we have just said, is that recent linguistics has made it possible to ascertain a certain finding of linguistic dimension preceding phonation, but still within the domain of linguistics. This is due to the fact that we are dealing not only with syntactic structure, which must be considered the specific nucleus of the very faculty of language, but also of a phonetic and phonic consistency at the level of the neural networks. It is, therefore, a recognition in terms of the language(s) involved. In other words, we do not only think linguistically but (at least in certain situations), rather in a very well defined language .

Therefore, not only does language have a foremost interior dimension, if it is understood as the disposition of a computational system with a mainly syntactic nature. It also has a further dimension, still internal, but to which we can add the application of universal syntactic parameters as well as characteristics that are already fully recognizable as single languages. There exists, that is, a form of thought which is already proprerly articulated (and is even formed with features of a single language). At the same time, it is independent from an external, phonic expression in the same language, with which it also maintains strong relations even at the level of activation of neural networks linked to hearing.

The Perspective From Textual Criticism and Philology

The existence of forms of linguistic production that are independent both from acts of phonation, and from writing, has always been known in an intuitive sense. Nevertheless, the received wisdom has tendentially merged or even confused the mental articulation of language with the dimensions of speech or writing. This appears to be the case with metaphors of daily language such as “I said to myself” (in order to introduce the content of a thought that is not truly “said”, but simply “thought”), or “I made a mental note”. Therefore, mental content exists that is linguistically articulated but which is neither “said” nor “written” in the true sense of these two words.

Even literary production has always considered the purely internal dimension of language, and not in a written or spoken sense. Literary works have given conventional representations which, once again, are mainly anchored in the traditional forms of dialogic speech: the form of an (interior) monologue assumes, in an earlier literary tradition, elements such as allocution to oneself (such as those of epic or tragic heroes, as well as lyricists of Antiquity). These elements represent the endophasic dimension as a variation of speech in which two interlocutors coincide.

More recent forms of literary representation (for example, the twentieth-century stream of consciousness) have allowed an attempt to give an autonomous and more “realistic” representation of such phenomena to emerge. In recent years, French stylistique has deepened the literary reflexes of the late nineteenth-century psychological debate (especially in France, as detailed below) on langage intérieur (for example, Rabatel 2001 , Martin-Achard 2016, Dujardin 1931 , Pettenati 1961 ). The in-depth analyses of literary criticism are numerous in these fields (for example, Philippe 2001 ; see above for G. R. Cardona’s particular linguistic view on variationist linguistics).

In fact, the (at least) partially autonomous nature of the articulation of internal language appears to have slipped away attention from its spoken form. This does not mean they are completely separated from it. Little attention has been given to the fact that the same act of writing (autonomous or as a form of copying) assumes a formalized pre-elaboration of content which is not spoken at all, but only thought.

In recent times, before the neurolinguistic studies discussed above, even a particular phenomenon such as transference— via copying—of a written text to another written text has been studied within philology. Indeed, philology has considered phenomena such as the so-called internal dictation in a profound way during the course of the 20th century (see the fundamental studies by Alphonse Dain (1975) ; on “internal pronunciation”, and cf. also Avalle’s considerations 1972, p. 34). Philology has identified a great number of indices which refer us back to a form of “listening” and internal “repetition” (in an acoustic sense) of a graphic sequence that is looked at during the first act of copying, and then transcribed in the second. Most copying errors that are ascribable to defects of internal dictation can be traced, in fact, to the acoustic nature of such repetitions. These errors, nevertheless, do not assume any sound if only that “of thought”, to return to Moro’s expression.

The Perspective From Psychology

The category of internal language was investigated in the fields of psychology and medicine before linguistics. The research conducted by Victor Egger (1881) , Egger (1904) and by Georges Saint-Paul (1892) , Saint-Paul (1904) , Saint-Paul (1912) during the last twenty years of the 19th century, has a seminal value. Partly adopting contrasting perspectives, they proposed establishing a typological classification of the forms of endophasy, bringing attention to the faculty of hearing, as well as visual and verbal-kinetic aspects of the internal representation of language. Until then, these aspects were not able to be investigated simply through introspection (Egger) or interrogation of witnesses (Saint-Paul). The latter originally used a questionnaire which was also distributed among writers; for a historiographical overview of this debate, see Carroy 2001 .

As is general for other aspects of linguistics, the approach that is based on the study of child language acquisition has allowed us to untangle that which appears difficult to ascertain in adults. According to Lev Vygotsky (1966) , whose theory on the formation of internal language is widely accepted, language in the child has a function for social interaction with people in immediate surrounding. Then an egocentric phase from which socialized and internal language derive.

In this particular area, Vygotsky’s model is accepted in substance by Jean Piaget, while reinterpreting the Vygotskian theory. Despite some cases of divergence on specific points, even the theoretician of genetic psychology agrees with the hypothesis that egocentric child language is the point of departure for the development of internal language. This phase is found during a successive stage of development, and is parallel to the formation of “socialized” language (it does not follow it, therefore, and is not derived from it either).

To the general category of internal language can be traced, in the adult, both endophasy (which does not assume any phonation), as well as solitary speech, which represents a sort of medial point between the proper dimension of internal language and the typical dimension of speech in the presence of an interlocutor.

Despite the debates outlined above in the field of psychology, a conspicuous part of general linguistics has continued (more or less) to explicitly reduce internal language to a simplified form of dialogue, in which two interlocutors coincide, through a sort of duplication of the subject into two interlocutors. In fact, this is the point of view, for example, that Benveniste, (1974) , p. 85 adopts in considering monologues: “le monologue procède bien de l’énonciation. Il doit être posé, malgré l’apparence, comme une variété du dialogue, structure fondamentale”. The example is valid also in showing a much broader tendency as well.

Writing, Speech, Thought

In reality, it is obvious that most linguistic production however it is understood occurs outside the domains of speech and writing. Most content that is articulated in a linguistic way (and, as we have said, this includes also mental content, in every sense) happens in thought, and precedes—literally—any form of external expression, spoken or written.

The way in which language is articulated internally is still largely unattainable. This explains the reason why its perception has always turned out to be fleeting, and its nature confused with other forms. If this is the case, the same relationship between spoken language and written language has been read in a completely different way from other graphical cultures (for example, Chinese, on which see the recent paper by Banfi 2020 ). This relationship has been consistently characterized by a tradition that adopts graphemes of a phonetic nature, and in a modern way.

The fact that “thought” language is attainable only in a difficult way, and describable only in specific forms, does not mean that it does not exist, however. The recent findings from neurolinguistics (which have created the possibility of tracing the recognition of syntactic structures independent from sound in the brain, as Moro et al., (2020) have recently done) open up interesting perspectives on the concrete attainability of the thought dimension of language. But even other elements may be involved, in the same sense.

On the other hand, even the spoken dimension of language (obviously much more relevant than written language) has long been neglected, since it is more difficult to obtain with respect to written language. Today, speech can be observed in various forms–that is, one can not only transcribe, but also record. This means that it has been considered as an autonomous subject.

Describing the study of the thought dimension, even in linguistic studies, could have further consequences for the way in which the two tangible dimensions of writing and speech are evaluated. We know that these dimensions influence each other. Koch and Österreicher have produced the most refined model, perhaps, to describe such reciprocal influence. But we do not know exactly what the relationship between them and the third dimension is.

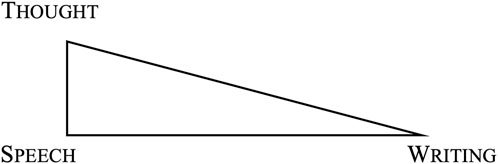

The representation of the relationship that has traditionally been conceived between speech and writing can therefore be summarized in a simple dependency of one on the other:

SPEECH(language proper).↓Writing.(conventional representation of speech, «non language»)

The model proposed by Koch-Österreicher energizes and complicates such a representation, while maintaining an eminently communicative vision of language, shifting the focus toward the notions of Distance and Conception: Figure 3 .

FIGURE 3 . Spoken vs Written Language according to Koch-Österreicher 1990 : 13.

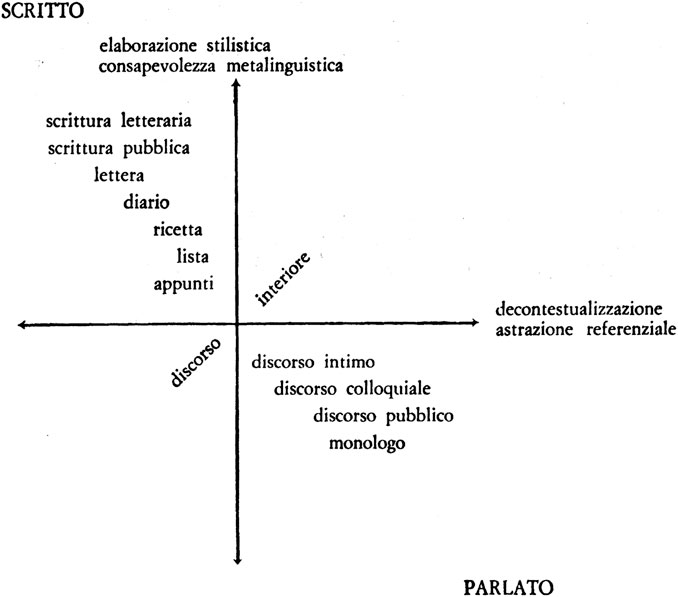

Cardona (1986) adopts an even broader and more articulated perspective, producing a model that is formally similar to those that were being elaborated contemporaneously in various subdisciplines of sociolinguistics (e.x., the well-known Berruto, 1987 model for contemporary Italian): Figure 4 .

FIGURE 4 . Spoken vs Written Language (and Internal Language) according to Cardona (1986) .

The direction which Cardona had already invited us to consider, and which the combined perspectives of twentieth-century psychology and recent neurolinguistics appear to endorse, is that of an even more decisive integration of the internal dimension in the study of language and languages. The consideration of thought language appears to be inevitably presupposed to the study of every manifestation—spoken and written—of language itself. One can attempt to supersede, in this way, the traditional, hierarchical vision which subordinates speech to writing on both of the traditionally identified dimensions. Both appear to be subjected, and equally so, to the overriding internal elaboration of language.

In this sense, the persistent idea loses some force that speech should take on a priority role in both the description and the realization of language. Speech is, certainly, the most direct and immediate projection of thought, but perhaps not the necessary cause of every manifestation of writing. Rather, in many cases it continues from thought in a much more plausible way. Naturally, this does not prevent the idea that the conception (in the sense intended by Koch-Österreicher) of text can bring the dimensions of speech and writing into communication. In the views which we have summarized here, they do not necessarily seem to be in a relationship of direct derivation: Figure 5 .

FIGURE 5 . Thought, Speech, Writing according our hypothesis.

In this model, the different length of the sides of the triangle refer to the diverse nature of spoken forms, as is natural, with respect to written forms, which are cultural and obviously negotiated. A possible representation of what is signed in this model would lead to a further derivation from thought which, in turn, would be independent from speech.

Possible Prospects: Outside Literature

Among the consequences of a possible autonomous recognition of the thought dimension of language, distinct from both speech and writing, is the question of overcoming an automatic act which appears to be reasonably widespread. This act derives from the consideration of written language as a simple reflection of speech. If what Saussure had already observed concerning alphabetic writing is irrefutable (that is, that writing reproduces more or less efficiently the phonic substance of words), then it is also true that a certain tendency can be observed to attribute the least characteristic or marginal facts of written language to a pure and simple influence of speech. In the elaboration of writing, thought generally appears much more decisive than speech proper.

In reality, there are various forms of written production that are difficult to interpret as representations of corresponding forms of speech. At the most simple level, what is obvious in forms of elementary text (the oldest attested forms in the development of writing) such as lists, notes, or annotations written down from memory, the writer does not address others but rather him or herself. Nor does the author intend to be comprehended by people other than themselves. It will be useful to recall that among the earliest manifestations of writing throughout history, we find functional texts that are not intended for interpersonal communication, nor for the reproduction of spoken discourse, but rather computational ones. In other words, numbers are born well before letters and “the code of abstract ideas, in particular the numerical code, seems to have performed an essential role from the first stages in the appearance of writing, and perhaps in the very idea that concepts can be written down” ( Deahaene 2009 , p. 211).

In general, a large part of so-called “semi learned” texts, which have been the object of linguistic enquiry for just a short time, present a linguistic phenomenology that is perhaps inappropriately described as being influenced by speech. A much more persuasive explanation of its various phenomena is provided by referring to the dimensions of thought, rather than to speech.

Cardona (1986 , p. 80) has also investigated this aspect of language. With respect to the category of ‘semi learned’ persons, he alludes to the modality of “writing down in real time one’s own mental discourse which is first and foremost—due to a lack of other models—an oral discourse”. But the priority of oral discourse appears dominant here too, when it appears necessary to shift toward a description of the syntax of thought in an analogous way that, for the syntax of speech, has allowed us to re-read and re-interpret such phenomena of written production coherently (as well as programmatic, in this sense, see Sabatini 1990 ).

Therefore, it can be useful to reconsider in a systematic way the elements which in non-literary writing (and particularly in less attentive writing) have traditionally been considered as reflexes of spoken language. One may ask whether these elements should not be removed from that dimension, and restored to the proper category of internal language. To quote one of the clearest and most recent formulations, it is a common opinion that “semi learned writing is characterized by an integral and large adoption of spoken structures” ( Testa 2014 , p. 107). But semi learned writing also includes the modality that Trifone 1986 has aptly described as being “writing for oneself”. Whether this type of writing simply integrates elements and styles of spoken language is a partially equivocal notion. It is created by a lack of features, made up of traits that are external to spoken language, and includes elements both of speech proper and elements of thought. Diaries, notes, jottings made out of necessity or from memory: those who write for themselves (and more so if the writer is semi learned) do not necessarily rely on speech, but more likely draw on the most immediate form of their linguistic production: thought.

Possible Prospects: Literary Production

Some elements of thought language have been highlighted by criticism and literary theory. But in terms of linguistic studies applied to literary texts, there seems to remain a certain reluctance to consider the relationship between internal language and literary language.

We have often borne witness to an appreciation of the literary reproduction of speech. In other words, the mimetic capacity of some literary production (especially in prose) reproduces phenomena in written form that are (or would be) unique to orality. This is one line of research that has been very productive, and which has the merit of clearly distinguishing between that which pertains to the written dimension (studied longer and in a deeper way) from that which does not pertain to it. In a certain sense, it is as if the term “speech” has long indicated simply “that which is not written”, or whatever is different from writing.

Among literary texts that best lend themselves to an indirect investigation of the typical characteristics of thought language, we find also poetic texts (especially lyrical ones), in which the subject, at the center of the discourse, does not seem to have any interlocutor. These texts can be placed alongside prose, discussed above on the flow of conscious and internal monologue.

Economy of syntax, omissions of references to context, advances of the text free from association of ideas without explanations, and a centering of the ego: these are just some of the elements which distinguish a part of poetic production—particularly modern poetry—from more traditional forms of poetic discourse, founded above all on the adoption of canonical verse and metrics. A conspicuous part of modern poetry seems to distinguish itself from prose above all for its privileged link, even if implicit, with the internal dimension of language, that is with thought language.

In this way, some stylistic traits unique to poetry—especially recent poetry—can be explained in an even more persuasive way if one attempts to describe them as outcomes just in terms of thought language. These forms have been typically characterized as an implausible reproduction of speech. This is a parallel, but distinct, step with respect to what we have said above in terms of non-literary writing. In both cases, it is a question of overcoming the almost seamless, and unwarranted, process of assigning phenomena that occur in certain forms of written language only in a marginal and peculiar way to an implausible flow of speech.

In conclusion, the intersection between literary writing and thought language deserves to be explored more attentively, with tools appropriate to linguistics. The noteworthy study of tracing reproducible elements, more or less consciously, of speech in literary texts could also be applied in identifying elements of thought language in literary writing proper. In modern poetry, the ongoing relaxation of the canonical, formal requirements seem to be compensated by an ever stronger relationship between poetry and thought language, whose syntactic, textual, and pragmatic points deserve further definition and articulation.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Avalle, D.-S. (1972). Principi di critica testuale . Padova: Antenore .

Banfi, E. (2020). “ Antinomia ‘parlato’ vs. ‘scritto’ Nel Pensiero Linguistico Cinese ,” in L’antinomia scritto/parlato , a cura di Franca Orletti e Federico Albano Leoni, Città di Castello, ( Emil , 69–87.

Google Scholar

Benveniste, É. (1974). Problèmes de linguistique générale . Paris,: Gallimard .

Bergounioux, G., (2001). (dir.), La parole intérieure , volume thématique de “Langue française” , 132.

Berruto, G. (1987). Sociolinguistica Dell’italiano Contemporaneo . Roma: La Nuova Italia .

Berwick, R. C., Friederici, A. D., Chomsky, N., and Bolhuis, J. J. (2013). Evolution, Brain, and the Nature of Language. Trends Cogn. Sci. 17, 89–98. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2012.12.002

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bloomfield, L. (1935). Language . London: Allen & Unwin .

Bologna, C. (1993). Tradizione e fortuna dei classici italiani: Dall'Arcadia al Novecento . Torino: Einaudi .

Cardona, G. R. (1983). “Culture dell'oralità e culture della scrittura,” in (a cura di), Letteratura italiana , II, Produzione e consumo . Editor A. Asor Rosa (Torino: Einaudi ), 25–101.

Cardona, G. R. (1990). I linguaggi del sapere , a cura di C . Bologna, Roma-Bari: Laterza .

Cardona, G. R. (1986). Testo Interiore, Testo Orale, Testo Scritto. «Belfagor» 41/1, 1–12.

Carroy, J. (2001). Bergounioux 2001 , 132, 48–56. doi:10.3406/lfr.2001.6314Le langage intérieur comme miroir du cerveau : une enquête, ses enjeux et ses limites “Langue française”

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

D’Achille, P. (1990). Sintassi del parlato e tradizione scritta della lingua italiana . Roma, Bonacci: Analisi di testi dalle origini al secolo XVIII .

Dain, A. (1975). Les Manuscrits . Paris, Les Belles-Lettres .

Deahaene, S. (2009). I Neuroni Della Lettura , Trad. it . Milano: Raffaello Cortina .

Dujardin, E. (1931). Le Monologue Intérieur . Paris: Messein .

Egger, V. (1881). La parole intérieure. Essai de psychologie descriptive . Paris: Berger-Levrault .

Egger, V. (1904). La parole intérieure. Essai de psychologie descriptive . Paris: Alcan .

Haspelmath, M. (2020). Human Linguisticality and the Building Blocks of Language. Front. Psychol. 10 (January 2020), 3056. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.03056)

Hjelmslev, L. (1966). Prolégomènes à une théorie du langage , trad. fr. Paris: Editions de Minuit , 1968–1971.

Kabatek, J. (2000). L’oral et l’écrit – quelques aspects théoriques d’un «nouveau» paradigme dans le canon de la linguistique romane, in W. Dahmen, G. Holtus, J. Kramer, M. Metzeltin, W. Schweickard, and O. Winkelmann (Hrsg.), Kanonbildung in der Romanistik und in den Nachbardisziplinen . Romanistisches Kolloquium XIV , Tübingen, Narr , pp. 305–320.

Koch, P., and Österreicher, W. (1990). “Gesprochene Sprache in der Romania”, in Französisch, Italienisch, Spanisch, Tübingen: Niemeye. doi:10.1515/9783111372914

Koch, P., and Österreicher, W. (2011). “Gesprochene Sprache in der Romania,” in Französisch, Italienisch, Spanisch , 2 . Ausgabe (Berlin/New York: De Gruyter ). doi:10.1515/9783110252620

Lotman, J., Uspenskij, M., and Boris, A. (1975). Editor R. M. Facciani / M. Marzaduri, Tipologia della cultura , Milano: Bompiani.

Magrassi, L., Aromataris, G., Cabrini, A., Annovazzi-Lodi, V., and Moro, A. (2015a). Sound Representation in Higher Language Areas during Language Generation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112 (6), 1868–1873. doi:10.1073/pnas.1418162112

Magrassi, L., Cabrini, A., Aromataris, G., Moro, A., and Annovazzi Lodi, V. (2015b). “Tracking of the Speech Envelope by Neural Activity during Speech Production Is Not Limited to Broca’s Area in the Dominant Frontal Lobe,” in Articolo presentato durante la 37th Annual International Conference of the ieee Engineering (Milano: Medicine and Biology Society ).

Martinet, A. (1972). “Lingua parlata e codice scritto,” in Linguistica e pedagogia , trad. it . Editor J. Martinet (Milano: Angeli ), 69–77.

Mioni, A. M. (1983). Italiano tendenziale: osservazioni su alcuni aspetti della standardizzazione, in Scritti linguistici in onore di Giovan Battista Pellegrini , Pisa: Pacini , 1983, pp. 495–517.

Moro, A. (2016). Le Lingue Impossibili . Milano: Raffello Cortina. doi:10.7551/mitpress/9780262034890.001.0001

CrossRef Full Text

Moro, A., Micera, S., Artoni, F., d'Orio, P., Catricalà, E., Conca, F., et al. (2020). High Gamma Response Tracks Different Syntactic Structures in Homophonous Phrases. «Scientific reports» . https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-64375-9 .

Nencioni, G. (1983). Di Scritto e di Parlato. Discorsi linguistici , Bologna: Zanichelli.

Pettenati, G. (1961). Su alcuni riflessi del discorso interiore nel discorso scritto. «Annali dell’Istituto Universitario Orientale – Sezione Linguistica» 3, 237–246.

Philippe, G. (2001). Le paradoxe énonciatif endophasique et ses premières solutions fictionnelles, in Bergouioux 2001 ( “Langue française” , 132), pp. 96–105. doi:10.3406/lfr.2001.6317

Rabatel, A. (2001). Les représentations de la parole intérieure [Monologue intérieur, discours direct et indirect libres, point de vue], lfr, in Bergounioux 2001 ( “Langue française” , 132), pp. 72–95. doi:10.3406/lfr.2001.6316

Sabatini, F. (1990). Una Lingua Ritrovata: L’italiano Parlato [1990], Ora in Id., L’italiano nel mondo moderno. Saggi scelti dal 1968 al 2009, ed. by V. Coletti, R. Coluccia, P. D’Achille, N. De Blasi, D. Proietti, Napoliet al. 2011, pp. 89–108.

Saint-Paul, G. (1892). Essais sur le langage intérieur . Lyon: Storck .

Saint-Paul, G. (1912). L’art de parler en publique . Paris: L’aphasie et le langage mentalDoin .

Saint-Paul, G. (1904). Le langages intérieur et les paraphasies . Paris: Alcan .

Saussure, F. (1967). Cours de linguistique générale . Paris: Payot .

Testa, Enrico. (2014). L’italiano nascosto. Una storia linguistica e culturale . Torino: Einaudi .

Trifone, P. (1986). “Rec. a E. Mattesini, Il ‘Diario’ in volgare quattrocentesco di Antonio Lotieri di Pisano notaio in Nepi (1985),” in «Studi linguistici italiani» XIIRinascimento dal basso. Il nuovo spazio del volgare tra Quattro e Cinquecento ( Roma: Bulzoni ), 133–142.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1966). Pensiero e linguaggio (con un’appendice di Jean Piaget) . Firenze: Giunti .

Keywords: language, spoken (and written language), written, psycholinguistic, linguistic variation

Citation: Tomasin L (2021) The Third Dimension. On the Dichotomy Between Speech and Writing. Front. Commun. 6:695917. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2021.695917

Received: 15 April 2021; Accepted: 06 May 2021; Published: 07 June 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Tomasin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lorenzo Tomasin, [email protected]

On the relationship between speech and writing with implications for behavioral approaches to teaching literacy

- PMID: 22477610

- PMCID: PMC2748615

- DOI: 10.1007/BF03392853

Two theories of the relationship between speech and writing are examined. One theory holds that writing is restricted to a one-way relationship with speech-a unidirectional influence from speech to writing. In this theory, writing is derived from speech and is simply a representation of speech. The other theory holds that additional, multidirectional influences are involved in the development of writing. The unidirectional theory focuses on correspondences between speech and writing while the multidirectional theory directs attention to the differences as well as the similarities between speech and writing. These theories have distinctive pedagogical implications. Although early behaviorism may be seen to have offered some support for the unidirectional theory, modern behavior analysis should be seen to support the multidirectional theory.

Speaking and Writing: Similarities and Differences

by Alan | May 2, 2017 | Communication skills , public speaking , writing

Similarities and Differences Between Speaking and Writing

There are many similarities between speaking and writing. While I’ve never considered myself a writer by trade, I have long recognized the similarities between writing and speaking. Writing my book was the single best thing I’ve ever done for my business. It solidified our teaching model and clarified and organized our training content better than any other method I’d ever tried.

A few weeks ago I was invited by a client to attend a proposal writing workshop led by Robin Ritchey . Since I had helped with the oral end of proposals, the logic was that I would enjoy (or gain insight) from learning about the writing side. Boy, were they right. Between day one and two, I was asked by the workshop host to give a few thoughts on the similarities of writing to speaking. These insights helped me recognize some weaknesses in my writing and also to see how the two crafts complement each other.

Similarities between Speaking and Writing

Here are some of the similarities I find between speaking and writing:

- Rule #1 – writers are encouraged to speak to the audience and their needs. Speakers should do the same thing.

- Organization, highlight, summary (tell ‘em what you’re going to tell them, tell them, tell them what you told them). Structure helps a reader/listener follow along.

- No long sentences. A written guideline is 12-15 words. Sentences in speaking are the same way. T.O.P. Use punctuation. Short and sweet.

- Make it easy to find what they are looking for (Be as subtle as a sledgehammer!) .

- Avoid wild, unsubstantiated claims. If you are saying the same thing as everyone else, then you aren’t going to stand out.

- Use their language. Avoid internal lingo that only you understand.

- The audience needs to walk away with a repeatable message.

- Iteration and thinking are key to crafting a good message. In writing, this is done through editing. A well prepared speech should undergo the same process. Impromptu is slightly different, but preparing a good structure and knowing a core message is true for all situations.

- Build from an outline; write modularly. Good prose follows from a good structure, expanding details as necessary. Good speakers build from a theme/core message, instead of trying to reduce everything they know into a time slot. It’s a subtle mindset shift that makes all the difference in meeting an audience’s needs.

- Make graphics (visuals) have a point. Whether it’s a table, figure, or slide, it needs to have a point. Project schedule is not a point. Network diagram is not a point. Make the “action caption” – what is the visual trying to say? – first, then add the visual support.

- Find strong words. My editor once told me, “ An adverb means you have a weak verb. ” In the workshop, a participant said, “ You are allowed one adverb per document. ” Same is true in speaking – the more powerful your words, the more impact they will have. Really (oops, there was mine).

- Explain data, don’t rely on how obvious it is. Subtlety doesn’t work.

Differences between Speaking and Writing

There are also differences. Here are three elements of speaking that don’t translate well to (business) writing:

- Readers have some inherent desire to read. They picked up your book, proposal, white paper, or letter and thus have some motivation. Listeners frequently do not have that motivation, so it is incumbent on the speaker to earn attention, and do so quickly. Writers can get right to the point. Speakers need to get attention before declaring the point.

- Emotion is far easier to interpret from a speaker than an author. In business writing, I would coach a writer to avoid emotion. While it is a motivating factor in any decision, you cannot accurately rely on the interpretation of sarcasm, humor, sympathy, or fear to be consistent across audience groups. Speakers can display emotion through gestures, voice intonations, and facial expressions to get a far greater response. It is interesting to note that these skills are also the most neglected in speakers I observe – it apparently isn’t natural, but it is possible.

- Lastly, a speaker gets the benefit of a live response. She can answer questions, or respond to a quizzical look. She can spend more time in one area and speed through another based on audience reaction. And this also can bring an energy to the speech that helps the emotion we just talked about. With the good comes the bad. A live audience frequently brings with it fear and insecurity – and another channel of behaviors to monitor and control.

Speaking and writing are both subsets of the larger skill of communicating. Improving communication gives you more impact and influence. And improving is something anyone can do! Improve your speaking skills at our Powerful, Persuasive Speaking Workshop and improve your writing skills at our Creating Powerful, Persuasive Content Workshop .

Communication matters. What are you saying?

This article was published in the May 2017 edition of our monthly speaking tips email, Communication Matters. Have speaking tips like these delivered straight to your inbox every month. Sign up today and receive our FREE download, “Twelve Tips that will Save You from Making a Bad Presentation.” You can unsubscribe at any time.

Enter your email for once monthly speaking tips straight to your inbox…

GET FREE DOWNLOAD “Twelve Tips that will Save You from Making a Bad Presentation” when you sign up. We only collect, use and process your data according to the terms of our privacy policy .

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Recent posts.

- Reading Scripts

- Your First Words

- The Problem with “Them”

- Same Old Same Ol’

- I Don’t Have Time to Prepare

- Don’t Sound like you’re Reading

- Bad PowerPoint

- Desperate Times, Desperate Measures

- Three Phrases to Avoid When Trying to Convince

Enter your email for once monthly speaking tips straight to your inbox!

FREE eBOOK DOWNLOAD when you sign up . We only collect, use and process your data according to the terms of our privacy policy.

Thanks. Your tips are on the way!

MillsWyck Communications

Pin It on Pinterest

Relationship and Difference Between Speech and Writing in Linguistics

Back to: Pedagogy of English- Unit 4

Many differences exist between the written language and the spoken language. These differences impact subtitling which is a practice that has become highly prevalent in the modern age. It is a process used to translate what the speaker is saying for those of other languages or who are deaf.

The main difference between written and spoken languages is that written language is comparatively more formal and complex than spoken language. Some other differences between the two are as follows:

Writing is more permanent than the spoken word and is changed less easily. Once something is printed, or published on the internet, it is out there for the world to see permanently. In terms of speaking, this permanency is present only if the speaker is recorded but they can restate their position.

Apart from formal speeches, spoken language needs to be produced instantly. Due to this, the spoken word often includes repetitions, interruptions, and incomplete sentences. As a result, writing is more polished.

Punctuation

Written language is more complex than spoken language and requires punctuation. Punctuation has no equivalent in spoken language.

Speakers can receive immediate feedback and can clarify or answer questions as needed but writers can’t receive immediate feedback to know whether their message is understood or not apart from text messages, computer chats, or similar technology.

Writing is used to communicate across time and space for as long as the medium exists and that particular language is understood whereas speech is more immediate.

Use of Slang

Written and spoken communication uses different types of language. For instance, slang and tags are more often used when speaking rather than writing.

Speaking and listening skills are more prevalent in spoken language whereas writing and reading skills are more prevalent in written language.

Tone and pitch are often used in spoken language to improve understanding whereas, in written language, only layout and punctuation are used.

These are the major differences between spoken language and written language.

Language and Emotion: Introduction to the Special Issue

- COMMENTARY / OPINIONS

- Published: 25 May 2021

- Volume 2 , pages 91–98, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Kristen A. Lindquist ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5368-9302 1

19k Accesses

16 Citations

18 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

What is the relationship between language and emotion? The work that fills the pages of this special issue draws from interdisciplinary domains to weigh in on the relationship between language and emotion in semantics, cross-linguistic experience, development, emotion perception, emotion experience and regulation, and neural representation. These important new findings chart an exciting path forward for future basic and translational work in affective science.

Similar content being viewed by others

Literalism in Autistic People: a Predictive Processing Proposal

Color associations to emotion and emotion-laden words: a collection of norms for stimulus construction and selection.

Transformer models for text-based emotion detection: a review of BERT-based approaches

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

What does language have to do with emotion? Estimates place the origin of spoken language around 50,000–150,000 years ago, a period that coincides with the speciation of Homo sapiens (Botha & Knight, 2009 ; Perreault & Mathew, 2012 ). Estimates on the origin of emotion in our evolutionary past are less clear. Although even the earliest nervous systems mitigated threats and acquired rewards, some scholars argue that the experience of discrete and conscious emotions only emerged with brain structures and functions unique to H. sapiens (Barrett, 2017 ; Ledoux, 2019 ). Indeed, some scholars hypothesize that the evolutionary pressures and adaptations that may have led to spoken language (caregiving, living in large social groups; de Boer, 2011 ; Dunbar, 2011 ; Falk, 2011 ) may be the same that scaffolded the development of discrete and conscious emotions in H. sapiens (Barrett, 2017 ; Ledoux, 2019 ). Correspondingly, H. sapiens’ ability to make discrete meaning of their affective states and to communicate about those states to others could itself have conferred evolutionary fitness (Bliss-Moreau, 2017 ). When taken together, these anthropological findings suggest that the relationship between language and emotion may be as deep as the origin of our species. They also suggest that the answer to the question “what does language have to do with emotion?” requires a truly interdisciplinary lens that blends questions and tools from fields as far-ranging as biological anthropology, cultural anthropology, linguistics, sociology, psychology, and neuroscience. Addressing this question is the purpose of this special issue of Affective Science.

In recent decades, there has been a veritable explosion of interdisciplinary research on language and emotion within modern affective science. For instance, linguistics research shows that almost all aspects of human spoken language communicate emotion, including prosody, phonetics, semantics, grammar, discourse, and conversation (Majid, 2012 ). Computational tools applied to natural human language reveal affective meanings that predict outcomes ranging from health and well-being to political behavior (see Jackson et al., 2020 ). Anthropological and linguistic research demonstrates differences in the meaning of emotion words around the world (Jackson et al., 2019 ; Lutz, 1988 ; Wierzbicka, 1992 ), which could contribute to obsverved cross-cultural differences in emotional experiences (Mesquita et al., 2016 ) and emotional expressions (Jack et al., 2016 ) and have implications for cross-cultural communication and diplomacy (see Barrett, 2017 ). Research in developmental psychology demonstrates that caregiver’s use of emotion words in conversation with infants longitudinally predicts emotion understanding and self-regulatory abilities in later childhood (see Shablack & Lindquist, 2019 ). In adults, psychological, physiological, and neuroscience research show that accessing emotion words alters emotion perception, self-reported experiences of emotion, the physiology and brain activity associated with emotion, and emotion regulation (Lindquist et al., 2016 ; Torre & Lieberman, 2018 ). It is thus no surprise that being able to specifically describe one’s emotional states predicts a range of physical and mental health outcomes (Kashdan et al., 2015 ) and that expressive writing can have a therapeutic effect (Pennebaker, 1997 ).

It was this burst of far-reaching and interesting recent findings that led us to propose a special issue on language and emotion at Affective Science . This special issue is the first of its kind at our still nascent journal, and I am grateful to the scholars who submitted 50 proposals for consideration in early 2020, the editorial team that helped evaluate them, and the authors, reviewers, and copyeditors of the 11 articles that now appear herein (all of whom accomplished this feat during the trials of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic). The result is an issue that builds on foundational knowledge about the relationship between language and emotion with a set of interdisciplinary tools that weigh in on new questions about this topic. The papers herein address the role of affect in semantics; the role of bilingualism in pain, emotional experiences, and emotion regulation; the role of language in the development of emotion knowledge; the role of labeling in emotion regulation; the role of language in the visual perception of emotion on faces; and the shared functional neuroanatomy of language and emotion. In this brief introduction to the special issue, I discuss why these findings are so fascinating and important by situating them in the existing literature and looking to still-unanswered questions. I close by looking forward to the future of research on language and emotion and the bright future of affective science.

What Is the Role of Emotion in Semantics?

Perhaps one of the most essential questions about the relationship between language and emotion revolves around the information that language conveys about emotion. Spoken language expresses experiences, which means that studying language can shine light on the nature of emotions. Indeed, language communicates emotion via almost every aspect (Majid, 2012 ). Computational linguistics approaches can now use tools from computer science and mathematics to summarize huge databases of spoken language to reveal the semantic meanings conveyed by language on an unprecedented scale (see Jackson et al., 2020 ). Perhaps most interesting among those endeavors is the ability to use the structure of spoken language to ask questions about how humans understand emotion concepts in particular and concepts in general (i.e., semantics).

Especially when analyzed at scale, linguistic databases offer an unprecedented opportunity to explore human mental life. For instance, we (Jackson et al., 2019 ) recently used a computational linguistics approach to examine humans’ understanding of 24 emotion concepts (e.g., “anger,” “sadness,” “fear,” “love,” “grief,” “joy”) across 2,474 languages spanning the globe. We used colexification—a phenomenon in which multiple concepts within a language are named by the same word—as an index of semantic similarity between concepts within a language family. We subsequently constructed networks representing universal and language-specific representations of emotion semantics—that is, which emotion concepts were understood as similar and which were understood as different within a language family. We observed significant cross-linguistic variability in the semantic structure of emotion across the 19 language families in our database. Interestingly, cross-linguistic similarity in emotion semantics was predicted by geographic proximity between language families, suggesting the potential role of cultural contact in shaping a language family’s understanding of emotions. Notably, we also observed a universal semantic structure for emotion concepts; emotion similarity was predicted by the affective dimensions of valence and arousal.

In this issue, DiNatale et al. ( in press ) used computational linguistics to show that valence and arousal do not just undergird the meaning of emotion concepts; these affective dimensions may undergird all linguistic concepts. Osgood ( 1952 ) classically demonstrated that valence, arousal, and dominance predict the extent to which people judge concepts as semantically similar. DiNatale et al. ( in press ) used a computational linguistics approach to show, for the first time at scale, that colexifications of roughly 40,000 concepts in 2,456 languages are predicted by the affective dimensions of valence, arousal, and dominance. This study exemplifies how computational tools and large corpora of text can be used to delve deeper into the relationship between language and emotion. More specifically, it provides strong empirical evidence at scale that affect underlies word meaning around the globe and that colexificationis a useful index of semantic similarity. These findings are fascinating in that they suggest that knowing what something is may fundamentally depend on knowing its impact on one’s emotions.

How Does Speaking Multiple Languages Alter Emotion?

Computational linguistics of course builds on linguistics, anthropology, sociology, cross-cultural psychology, and other social sciences that use ethnography and cross-cultural comparisons to understand cross-linguistic differences and similarities in emotion. Classic accounts of the 19th and 20th centuries (Darwin, 1872/ 1965 ; Levy, 1984 ; Lutz, 1988 ; Mead, 1930 ) documented cross-cultural differences and similarities in emotion concepts (see Russell, 1991 for a review). Similarly, qualitative comparisons between languages (Wierzbicka, 1992 ) documented both variability in the semantic meaning of emotion concepts across lexicons and core commonalities.

More recently, cross-cultural psychology has addressed cross-cultural similarities and differences in the experience, perception, regulation, and expression of emotions (Chentsova-Dutton, 2020 ; Kitayama & Markus, 1994 ; Mesquita et al., 2016 ; Mesquita & Boiger, 2014 ; Scherer, 1997 ; Tsai, 2007 ). Although this work studies people from different cultures (who largely speak different languages), relatively little has explicitly addressed the role of language in emotion. Pavlenko’s ( 2008 ) work on bilingualism and emotion examines how access to different languages can subserve cross-cultural differences in emotion but much more work is needed in our increasingly bicultural world.

Two papers in this special issue specifically address how bilingualism alters affective states. Gianola et al. ( in press ) examined how bilingualism can impact the intensity of pain by assessing bilingual Latinx participants’ experience of pain when reporting in Spanish versus English. They found that participants reported more intense thermal pain when reporting in the language consistent with their dominant cultural identity (Spanish vs. English). This effect was mediated by skin conductance responses during pain, such that speaking in Spanish resulted in greater skin conductance and greater intensity pain for Latinx participants.

Zhou et al. ( in press ) investigated in this issue how both culture and language impact the pattern of daily self-reported emotional experiences in Chinese–English bilinguals. They show that the patterns of Chinese and English monolinguals’ emotion self-reports are distinct, but that Chinese–English bilinguals’ self-reported emotion patterns are a blend of their monolingual counterparts’ patterns. Answering the survey in Chinese versus English exacerbated the difference between the emotion patterns of Chinese bilinguals and English monolinguals; this effect was also influenced by the extent of exposure to speakers’ non-native culture. Collectively, these findings are beginning to show that language is not merely a form of communication, but that speaking different languages may differentially impact the experience of affective states.

How Does Learning About Emotion Words Alter the Development of Emotion?

Different languages may impact emotion because they encode different emotion concepts. Learning a language helps speakers acquire the emotion concepts relevant to their culture. Indeed, developmental psychology research demonstrates that early discourse with adults helps children to acquire and develop a complex understanding of the emotion concepts encoded in their language (see Shablack & Lindquist, 2019 ). For instance, early findings showed that parents’ use of language about emotions in child-directed speech longitudinally predicted children’s understanding of other’s emotions at 36 months (Dunn et al., 1991 ). Other work found that language abilities, more generally, predicted emotion understanding (Pons et al., 2003 ). Widen and Russell ( 2003 , 2008 ) showed that young (aged 2–7) children’s ability to perceive emotions on faces correlated with the number of emotion category labels that those children produced in spoken discourse. These findings furthermore showed that children’s understanding of the meaning of labels such as “anger,” “sadness,” “fear,” and “disgust” started quite broadly in terms of valence but that it narrowed over time to be more discrete and categorical. More recently, Nook et al. ( 2020 ) demonstrated a developmental shift in the structure of emotion knowledge, such that children’s understanding of linguistic emotion categories starts unidimensionally in terms of valence but becomes more multidimensional from childhood to adolescence.

What still remains unknown is how infants and children learn to map emotion labels to emotional behaviors and sensations in the world, and how their understanding of emotions ultimately becomes adult-like through experience and learning. Although such label-concept mapping has been well studied in object perception, it is relatively unstudied in emotion (see Hoemann et al., 2020 ). In this issue, Ruba et al. ( in press ) weighed in on this question by examining how 1-year-olds learn to map novel labels to facial expressions. They found that 18-month-olds are readily able to match labels to human facial muscle movements but that vocabulary size and stimulus complexity predict 14-month-olds’ ability to do so. What is perhaps most interesting about these findings is not that 18-month-olds can map labels to facial muscle movements, but that variation in linguistic abilities and stimulus complexity predicts 14-month-olds’ ability to do so. These findings are consistent with other research showing that receptive vocabulary also predicts 14-month-olds’ ability to categorize physical objects in a more complex abstract, goal-directed, and situated manner (e.g., that blocks can be categorized by both shape or material; Ellis & Oakes, 2006 ) Taken together, these findings may suggest that emotion categories are more akin to abstract categories that are a product of social learning than concrete categories that exist in the physical world.

In this special issue, Grosse et al. ( in press ) also provide important new evidence on how children aged 4–11 learn to use words to communicate about emotion. They reveal that children’s use of a range of emotion labels to describe vignettes increases with age, but that children fail to show an adult-like understanding of emotion labels even by age 11. Critically, they build upon the prior developmental work by showing that the more children hear certain labels for emotion in adults’ child-directed discourse, the earlier and more frequently children use those labels to describe emotional situations. Collectively, the work of Ruba et al. ( in press ) and Grosse et al. ( in press ) is beginning to show exactly how exposure to language about emotion contributes to more complex emotional abilities from infancy onward.

How Does Language Alter Emotion Perception?

The research makes increasingly clear that language represents semantic content related to emotion, impacts the emotional reports—and perhaps even physiological intensity of --affective experiences for bilingual individuals, and influences emotion perception and understanding during early development. These findings may still leave open the possibility that language has a relatively superficial effect on emotion, insofar as it only impacts emotion after the fact during communication. Yet a body of growing research suggests that momentary access to emotion words may also impact the content of individuals’ emotional perceptions (Lindquist et al., 2016 ). Studies that use cognitive techniques such as semantic satiation or priming to increase or decrease accessibility to the meaning of emotion category labels demonstrate respective impairments or facilitation in participants’ ability to perceive emotion on other’s faces; these effects occur even in tasks that do not explicitly require verbal labeling during responding. For instance, in the first study to this effect, we (Lindquist et al., 2006 ) used semantic satiation—in which participants repeat a word relevant to an upcoming perceptual judgment (e.g., “anger”) out loud 30 times—to temporarily impair participants’ access to the semantic meaning of emotion category labels. Participants then made a perceptual judgment about whether two facial portrayals of the named emotion category (e.g., anger) matched one another or not. We found that participants were slower and less accurate to perceptually match the two angry faces on satiation but not control trials (in which they had repeated the word out loud only 3 times). Multiple studies have since replicated and extended this effect. For instance, we have shown that semantic satiation impairs an emotional facial portrayals’ ability to perceptually prime itself in the subsequent moments (Gendron et al., 2012 ) and that individuals with semantic dementia, who have permanently reduced access to the meaning of words following neurodegeneration, can no longer freely sort facial portrayals of emotion into six discrete categories of anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, and neutral (Lindquist et al., 2014 ). In contrast, studies found that priming emotion labels facilitates and biases the perception of emotional facial portrayals. For instance, verbalizing the emotional meaning of facial muscle movements with an emotion label (e.g., “anger”) biases perceptual memory of the face towards a more prototypical representation of the facial muscle movements associated with that category (Halberstadt et al., 2009 ). Access to emotion category labels also speeds and sensitizes perceptions of facial portrayals of emotion towards a more accurate representation of the observed face (Nook et al., 2015 ). Moreover, learning novel emotion category labels induces categorical perception of unfamiliar facial behaviors (Fugate et al., 2010 ) and helps individuals to acquire and update their perceptual categories of emotional facial behaviors (Doyle & Lindquist, 2018 ).

Collectively, these findings lead to the hypothesis that emotion category labels serve as a form of context that helps disambiguate the meaning of others’ affective behaviors (Barrett et al., 2007 ; Lindquist et al., 2015 ; Lindquist & Gendron, 2013 ). Two papers in this special issue are the first to my knowledge to show that emotion category labels are superior to other forms of context when participants are perceiving emotion in facial portrayals. Lecker and Aviezer ( in press ) presented a study that extends their prior work demonstrating that body postures serve as a form of context for understanding the meaning of emotional facial portrayals. They found that labeling face–body pairs with emotion category labels boosts the effect of the body on facial emotion perception when compared to trials in which participants use a nonverbal response option; these findings suggest that emotion concepts are likely used to make meaning of both facial and body cues as instances of emotion categories, and that body cues may evoke contextual effects on the perception of facial emotion, in part, because they prime emotion concepts. Indeed, one interpretation of the effect of other forms of context on perception of facial emotion is that these contexts prime emotion categories. To test this hypothesis, we (Doyle et al., in press ) explicitly compared the effect of visual scenes versus emotion category labels as primes for perceptions of facial emotion. Mirroring the findings of Lecker and Aviezer ( in press ), we found that priming the words “sadness” and “disgust” facilitates the perception of those emotions in facial portrayals to a greater extent than do visual scenes conveying sad versus disgusting contexts (e.g., a funeral, cockroaches on food). We further demonstrate that basic-level categories such as “sadness” and “disgust” more effectively prime facial emotion perception than subordinate-level categories such as “misery” or “repulsion,” consistent with the notion that basic-level categories are those that most efficiently guide categorization (Rosch, 1973 ).

Finally, in this issue Schwering et al. ( in press ) extended these “language as context” findings by showing how exposure to emotion words via fiction reading may help individuals to build the cache of emotion concepts that in turn guide emotion perception. Through a large-scale corpus analysis, the authors demonstrate that fiction specifically contains linguistic information related to the contents of other’s minds; exposure to fiction, in turn, predicts participants’ ability to perceive emotion in facial portrayals. These findings mirror the developmental evidence that exposure to emotion words in childhood predicts emotion understanding (Dunn et al., 1991 ; Grosse et al., in press ) and suggest that exposure to emotion words via fiction may continue to facilitate greater emotion perception ability across the lifespan.

How Does Language Alter Emotion Experience and Regulation?

Finally, there is growing evidence that language not only alters emotion perception on others’ faces, but that it also alters how a person experiences and regulates emotional sensations within their own bodies. Like the perception findings, these findings suggest that the effect of language on emotion goes beyond mere communication insofar as access to emotion labels during emotional experience impacts behavioral, physiological, and neural correlates of emotion and emotion regulation. Some research suggests that labeling one’s affective state solidifies it, causing participants to experience a more ambiguous affective state as a discrete and specific instance of an emotion category. For instance, we (Lindquist & Barrett, 2008 ) found that priming participants with the linguistic emotion category “fear” (vs. “anger” or a neutral control prime) prior to an unpleasant experience made participants exhibit greater risk aversion, which is prototypically associated with experiences of fear but not anger. Similarly, Kassam and Mendes ( 2013 ) demonstrated that asking participants to label (vs. not label) their experience of anger during an unpleasant interview may have solidified participants’ experience of anger. Participants who labeled versus did not label their feelings had increased cardiac output and vasoconstriction, which are both associated with experiences of anger.