- NONFICTION BOOKS

- BEST NONFICTION 2023

- BEST NONFICTION 2024

- Historical Biographies

- The Best Memoirs and Autobiographies

- Philosophical Biographies

- World War 2

- World History

- American History

- British History

- Chinese History

- Russian History

- Ancient History (up to 500)

- Medieval History (500-1400)

- Military History

- Art History

- Travel Books

- Ancient Philosophy

- Contemporary Philosophy

- Ethics & Moral Philosophy

- Great Philosophers

- Social & Political Philosophy

- Classical Studies

- New Science Books

- Maths & Statistics

- Popular Science

- Physics Books

- Climate Change Books

- How to Write

- English Grammar & Usage

- Books for Learning Languages

- Linguistics

- Political Ideologies

- Foreign Policy & International Relations

- American Politics

- British Politics

- Religious History Books

- Mental Health

- Neuroscience

- Child Psychology

- Film & Cinema

- Opera & Classical Music

- Behavioural Economics

- Development Economics

- Economic History

- Financial Crisis

- World Economies

- Investing Books

- Artificial Intelligence/AI Books

- Data Science Books

- Sex & Sexuality

- Death & Dying

- Food & Cooking

- Sports, Games & Hobbies

- FICTION BOOKS

- BEST NOVELS 2024

- BEST FICTION 2023

- New Literary Fiction

- World Literature

- Literary Criticism

- Literary Figures

- Classic English Literature

- American Literature

- Comics & Graphic Novels

- Fairy Tales & Mythology

- Historical Fiction

- Crime Novels

- Science Fiction

- Short Stories

- South Africa

- United States

- Arctic & Antarctica

- Afghanistan

- Myanmar (Formerly Burma)

- Netherlands

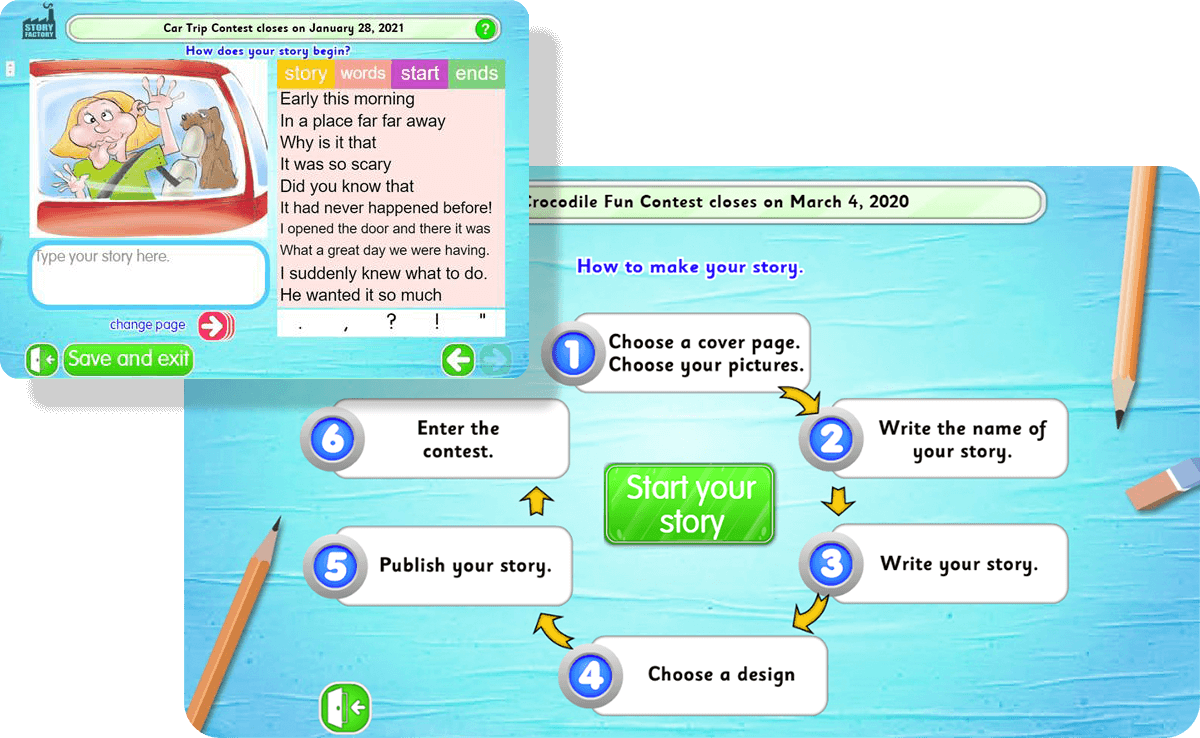

- Kids Recommend Books for Kids

- High School Teachers Recommendations

- Prizewinning Kids' Books

- Popular Series Books for Kids

- BEST BOOKS FOR KIDS (ALL AGES)

- Ages Baby-2

- Books for Teens and Young Adults

- THE BEST SCIENCE BOOKS FOR KIDS

- BEST KIDS' BOOKS OF 2023

- BEST BOOKS FOR TEENS OF 2023

- Best Audiobooks for Kids

- Environment

- Best Books for Teens of 2023

- Best Kids' Books of 2023

- Political Novels

- New History Books

- New Historical Fiction

- New Biography

- New Memoirs

- New World Literature

- New Economics Books

- New Climate Books

- New Math Books

- New Philosophy Books

- New Psychology Books

- New Physics Books

- THE BEST AUDIOBOOKS

- Actors Read Great Books

- Books Narrated by Their Authors

- Best Audiobook Thrillers

- Best History Audiobooks

- Nobel Literature Prize

- Booker Prize (fiction)

- Baillie Gifford Prize (nonfiction)

- Financial Times (nonfiction)

- Wolfson Prize (history)

- Royal Society (science)

- Pushkin House Prize (Russia)

- Walter Scott Prize (historical fiction)

- Arthur C Clarke Prize (sci fi)

- The Hugos (sci fi & fantasy)

- Audie Awards (audiobooks)

Make Your Own List

Language » Writing Books

The best books on creative writing, recommended by andrew cowan.

The professor of creative writing at UEA says Joseph Conrad got it right when he said that the sitting down is all. He chooses five books to help aspiring writers.

Becoming a Writer by Dorothea Brande

On Becoming a Novelist by John C. Gardner

On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King

The Forest for the Trees by Betsy Lerner

Worstward Ho by Samuel Beckett

1 Becoming a Writer by Dorothea Brande

2 on becoming a novelist by john c. gardner, 3 on writing: a memoir of the craft by stephen king, 4 the forest for the trees by betsy lerner, 5 worstward ho by samuel beckett.

How would you describe creative writing?

But because it is in academia there is all this paraphernalia that has to go with it. So you get credits for attending classes. You have to do supporting modules; you have to be assessed. If you are doing an undergraduate degree you have to follow a particular curriculum and only about a quarter of that will be creative writing and the rest will be in the canon of English literature . If you are doing a PhD you have to support whatever the creative element is with a critical element. So there are these ways in which academia disciplines writing and I think of that as Creative Writing with a capital C and a capital W. All of us who teach creative writing are doing it, in a sense, to support our writing, but it is also often at the expense of our writing. We give up quite a lot of time and mental energy and also, I think, imaginative and creative energy to teach.

Your first choice is Dorothea Brande’s Becoming a Writer , which for someone writing in 1934 sounds pretty forward thinking.

Because creative writing has now taken off and has become this very widespread academic discipline it is beginning to acquire its own canon of key works and key texts. This is one of the oldest of them. It’s a book that almost anyone who teaches creative writing will have read. They will probably have read it because some fundamentals are explained and I think the most important one is Brande’s sense of the creative writer being comprised of two people. One of them is the artist and the other is the critic.

Actually, Malcolm Bradbury who taught me at UEA, wrote the foreword to my edition of Becoming a Writer , and he talks about how Dorothea Brande was writing this book ‘in Freudian times’ – the 1930s in the States. And she does have this very Freudian idea of the writer as comprised of a child artist on the one hand, who is associated with spontaneity, unconscious processes, while on the other side there is the adult critic making very careful discriminations.

And did she think the adult critic hindered the child artist?

No. Her point is that the two have to work in harmony and in some way the writer has to achieve an effective balance between the two, which is often taken to mean that you allow the artist child free rein in the morning. So you just pour stuff on to the page in the morning when you are closest to the condition of sleep. The dream state for the writer is the one that is closest to the unconscious. And then in the afternoon you come back to your morning’s work with your critical head on and you consciously and objectively edit it. Lots of how-to-write books encourage writers to do it that way. It is also possible that you can just pour stuff on to the page for days on end as long as you come back to it eventually with a critical eye.

Get the weekly Five Books newsletter

Good! Your next book, John Gardner’s On Becoming a Novelist , is described as comfort food for the aspiring novelist.

This is another one of the classics. He was quite a successful novelist in the States, but possibly an even more successful teacher of creative writing. The short story writer and poet Raymond Carver, for instance, was one of his students. And he died young in a motorcycle accident when he was 49. There are two classic works by him. One is this book, On Becoming a Novelist , and the other is The Art of Fiction: Notes on Craft for Young Writers . They were both put together from his teaching notes after he died.

On Becoming a Novelist is the more succinct and, I think, is the better of the two. He talks about automatic writing and the idea, just like Dorothea Brande, of the artist being comprised of two people. But his key idea is the notion of the vivid and continuous dream. He suggests that when we read a novel we submit to the logic of that novel in the same way as we might submit to the logic of a dream – we sink into it, and clearly the events that occur could not exist outside the imagination.

What makes student writing in particular go wrong is when it draws attention to itself, either through bad writing or over-elaborate writing. He suggests that these faults in the aspirant writer alert the reader to the fact that they are reading a fiction and it is a bit like giving someone who is dreaming a nudge. It jolts them out of the dream. So he proposes that the student writer should try to create a dream state in the reader that is vivid and appeals to all the senses and is continuous. What you mustn’t do is alert the reader to the fact that they are reading a fiction.

It is a very good piece of advice for writers starting out but it is ultimately very limiting. It rules out all the great works of modernism and post-modernism, anything which is linguistically experimental. It rules out anything which draws attention to the words as words on a page. It’s a piece of advice which really applies to the writing of realist fiction, but is a very good place from which to begin.

And then people can move on.

I never would have expected the master of terror Stephen King to write a book about writing. But your next choice, On Writing , is more of an autobiography .

Yes. It is a surprise to a lot of people that this book is so widely read on university campuses and so widely recommended by teachers of writing. Students love it. It’s bracing: there’s no nonsense. He says somewhere in the foreword or preface that it is a short book because most books are filled with bullshit and he is determined not to offer bullshit but to tell it like it is.

It is autobiographical. It describes his struggle to emerge from his addictions – to alcohol and drugs – and he talks about how he managed to pull himself and his family out of poverty and the dead end into which he had taken them. He comes from a very disadvantaged background and through sheer hard work and determination he becomes this worldwide bestselling author. This is partly because of his idea of the creative muse. Most people think of this as some sprite or fairy that is usually feminine and flutters about your head offering inspiration. His idea of the muse is ‘a basement guy’, as he calls him, who is grumpy and turns up smoking a cigar. You have to be down in the basement every day clocking in to do your shift if you want to meet the basement guy.

Stephen King has this attitude that if you are going to be a writer you need to keep going and accept that quite a lot of what you produce is going to be rubbish and then you are going to revise it and keep working at it.

Do you agree with him?

He sounds inspirational. Your next book, Betsy Lerner’s The Forest for the Trees , looks at things from the editor’s point of view.

Yes, she was an editor at several major American publishing houses, such as Simon & Schuster. She went on to become an agent, and also did an MFA in poetry before that, so she came through the US creative writing process and understands where many writers are coming from.

The book is divided into two halves. In the second half she describes the process that goes from the completion of the author’s manuscript to submitting it to agents and editors. She explains what goes on at the agent’s offices and the publisher’s offices. She talks about the drawing up of contracts, negotiating advances and royalties. So she takes the manuscript from the author’s hands, all the way through the publishing process to its appearance in bookshops. She describes that from an insider’s point of view, which is hugely interesting.

But the reason I like this book is for the first half of it, which is very different. Here she offers six chapters, each of which is a character sketch of a different type of author. She has met each of them and so although she doesn’t mention names you feel she is revealing something to you about authors whose books you may have read. She describes six classic personality types. She has the ambivalent writer, the natural, the wicked child, the self-promoter, the neurotic and a chapter called ‘Touching Fire’, which is about the addictive and the mentally unstable.

Your final choice is Worstward Ho by Samuel Beckett .

This is a tiny book – it is only about 40 pages and it has got these massive white margins and really large type. I haven’t counted, but I would guess it is only about two to three thousand words and it is dressed up as a novella when it is really only a short story. On the first page there is this riff: ‘Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.’

Support Five Books

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you're enjoying this interview, please support us by donating a small amount .

When I read this I thought I had discovered a slogan for the classroom that I could share with my students. I want to encourage them to make mistakes and not to be perfectionists, not to feel that everything they do has to be of publishable standard. The whole point of doing a course, especially a creative writing MA and attending workshops, is that you can treat the course as a sandpit. You go in there, you try things out which otherwise you wouldn’t try, and then you submit it to the scrutiny of your classmates and you get feedback. Inevitably there will be things that don’t work and your classmates will help you to identify those so that you can take it away and redraft it – you can try again. And inevitably you are going to fail again because any artistic endeavour is doomed to failure because the achievement can never match the ambition. That’s why artists keep producing their art and writers keep writing, because the thing you did last just didn’t quite satisfy you, just wasn’t quite right. And you keep going and trying to improve on that.

But why, when so much of it is about failing – failing to get published, failing to be satisfied, failing to be inspired – do writers carry on?

I have a really good quote from Joseph Conrad in which he says the sitting down is all. He spends eight hours at his desk, trying to write, failing to write, foaming at the mouth, and in the end wanting to hit his head on the wall but refraining from that for fear of alarming his wife!

It’s a familiar situation; lots of writers will have been there. For me it is a kind of obsessive-compulsive disorder. It is something I have to keep returning to. I have to keep going back to the sentences, trying to get them right. Trying to line them up correctly. I can’t let them go. It is endlessly frustrating because they are never quite right.

You have published four books. Are you happy with them?

Reasonably happy. Once they are done and gone I can relax and feel a little bit proud of them. But at the time I just experience agonies. It takes me ages. It takes me four or five years to finish a novel partly because I always find distractions – like working in academia – something that will keep me away from the writing, which is equally as unrewarding as it is rewarding!

September 27, 2012

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]

Andrew Cowan

Andrew Cowan is Professor of Creative Writing and Director of the Creative Writing programme at UEA. His first novel, Pig , won the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award, the Betty Trask Award, the Ruth Hadden Memorial Prize, the Author’s Club First Novel Award and a Scottish Council Book Award. He is also the author of the novels Common Ground , Crustaceans , What I Know and Worthless Men . His own creative writing guidebook is The Art of Writing Fiction .

We ask experts to recommend the five best books in their subject and explain their selection in an interview.

This site has an archive of more than one thousand seven hundred interviews, or eight thousand book recommendations. We publish at least two new interviews per week.

Five Books participates in the Amazon Associate program and earns money from qualifying purchases.

© Five Books 2024

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Lit Century

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

The Classes 25 Famous Writers Teach

They're not always what you'd expect.

Plenty of writers teach. Even famous ones. This is a known fact of the universe. After all, academy jobs are notoriously cushy; what you give up in writing time you get back in the form of a steady salary, summers off, and the nebulous reward of eager minds to mold. As for how exactly they might be molded, well, that’s up to the writer in question.

Last week, I started looking through college catalogs to see what interesting literature courses I might read along with this fall, and in the process I stumbled across more than a few descriptions for classes taught by famous writers—and some of them surprised me. Who knew, for instance, that Jonathan Lethem loved animals enough to build a course around them? Or that in addition to writing workshops, Jim Shepard likes to teach horror movies at Williams? On the other hand, I’m not at all surprised to find that Claudia Rankine teaches classes that seek to unpack the nature of whiteness, but I’m thrilled to have come across her meticulous reading list for last year’s course.

Below, I’ve collected course descriptions for classes taught by 25 well-known writers at both the graduate and undergraduate levels. Most of these are from the current school year, but a few have been culled from recent semesters. Though plenty of writers teach straight workshops (whether poetry, fiction, or non-fiction), I’ve omitted those here, since we all pretty much know what a workshop consists of. Instead, I’ve picked out the more interesting options, whether themed workshops or literature classes, which give a little more insight into the writer’s interests, academic or otherwise. It’s enough to make any reader envious of the youth today—and to that end, if you’re lucky enough to be at one of these schools right now, I suggest that you don’t miss taking one of these classes with a literary legend.

Lorrie Moore:

Special Topics in Creative Writing : “What’s So Funny?: An Investigation” (Engl. 3891.01), Vanderbilt University, Spring 2017

Course Description : A look at literary texts from Shakespeare to Toni Cade Bambara to discover how literary humor is used in writing. What are the mechanics of making it occur? What are its various attributes and categories and sub-species? What are the underlying theories in practice? This is not a lecture course but an intensive reading and discussion course—class presentations and quizzes required but only a little writing.

Jonathan Lethem:

Topics in Contemporary Fiction : Animals (ENGL055B PO), Pomona College; Spring 2015

Course Description : Readings in stories, novels, and essays in which the subject of the lives of animals invites consideration of topics of empathy, suffering and the body, in contemporary writing and thought generally. We’ll also take more than a sidelong glance at the function and uses of literary strategies of allegory, parable and fable. Letter grade only.

Impossible Novels : The Man Without Qualities (ENGL055A PO), Pomona College; Spring 2016

Course Description : In the poet Randall Jarrell’s definition, “a novel is a prose narrative of a certain length with something wrong with it.” The Austrian Modernist Robert Musil’s The Man Without Qualities , an unfinished novel of 1700 pages in its most comprehensive edition, is an exemplary case of the above. Musil is often classed with Proust and Joyce in the 20th Century pantheon; he’s also rarely read. In this seminar we’ll tackle this vast book directly and by using a number of historical and critical sources, as well as Musil’s diaries, to surround and inform it with useful context. The result will be a reading expedition to an unknown shore. Letter grade only.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Writing Narrative (ENGL 302), USC, Fall 2016

Course Description : This course takes as its premise that art and politics can co-exist. e writers that we will read grapple with what it means to be an “other” and how to write about it. Frequently this involves dealing with the history that has produced one’s otherness; with the task of translation that often falls on the other; with the burden of representing the marginalized community from which one comes; with crossing borders of all kinds — linguistic, sexual, geographical, generic. All the writers we will read are hard to classify, because they rebel against classi cation itself, which seeks to pin the other down into a manageable category (race, class, gender, sexuality, nationality, religion, etc.). As writers, students will have the chance to experiment with narrative, to disregard generic boundaries, to take on di cult subjects, to be critical in their creative writing, or to be creative in their critical writing. e form of what will be written is secondary to the story that needs narration.

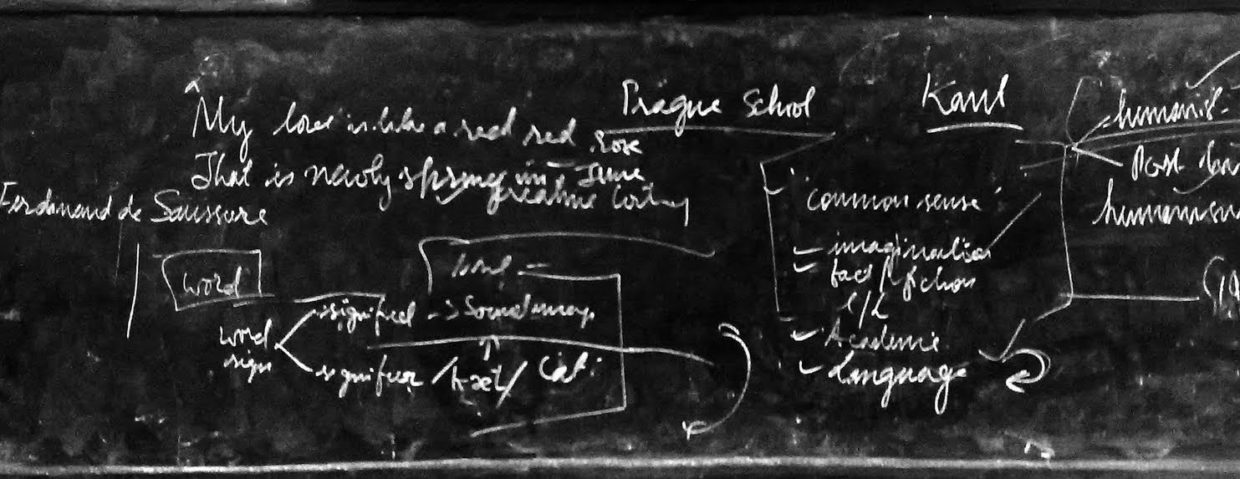

Introduction to Literary and Cultural Criticism and Theory (ENGL 501), USC, Fall 2015

Course Description : As the title indicates, this course is an introduction. It requires no advance knowledge of literary and cultural criticism and theory. We will read excerpts from the N orton Anthology of Theory and Criticism on the major theorists and philosophers who have shaped contemporary criticism (in no particular order: Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault, Judith Butler, Edward Said, Gayatri Spivak, Sigmund Freud, Jacques Lacan, Stuart Hall, Fredric Jameson, and others). In addition, given that half of the seminar will be composed of creative writers and the other half of literary critics (although perhaps some may cross the line and do both), we will also look at some figures who do both creative and critical work, such as Roland Barthes, Susan Sontag, Claudia Rankine, Gloria Anzaldúa, and Trinh T. Minh-ha, in an effort to see how criticism can inform creative work, and vice versa. Figuring out what terms like structuralism, poststructuralism, postcolonialism, psychoanalysis, feminism, Marxism, and others, do in literary and cultural theory will also be on the agenda. Be prepared to lead the seminar in discussion, to participate in the conversation both in seminar and online, and to write a research paper or an essay.

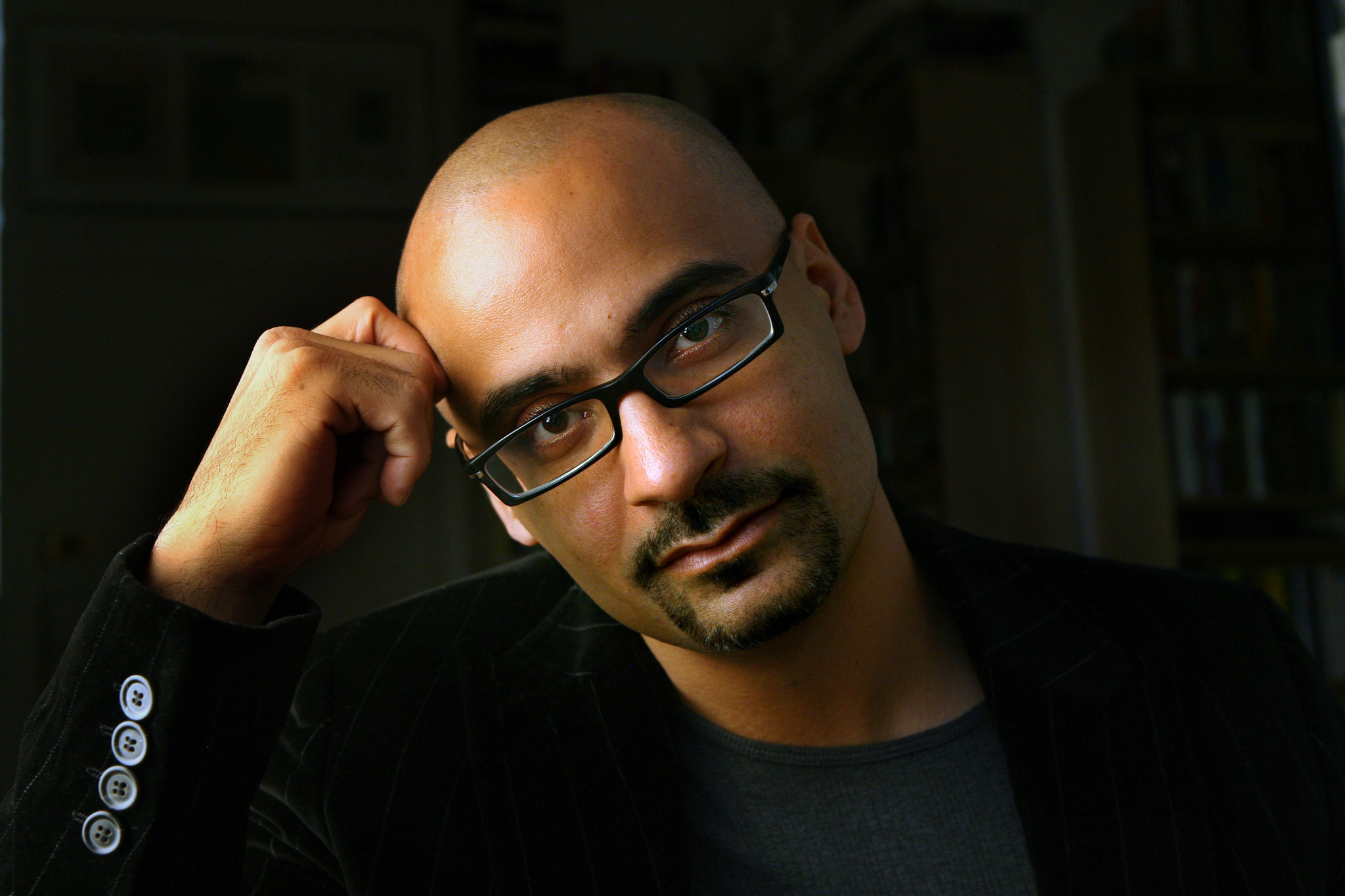

Junot Díaz:

Apocalyptic Storytelling (CMS.848), MIT, Fall 2017

Course Description : Focuses on the critical making of apocalyptic, post-apocalyptic and dystopian stories across various narrative media. Considers the long history of Western apocalypticism as well as the uses and abuses of apocalypticism across time. Examines a wide variety of influential texts in order to enhance students’ creative and theoretical repertoires. Students create their own apocalyptic stories and present on selected texts. Investigates conventions such as plague, zombies, nuclear destruction, robot uprising, alien invasion, environmental collapse, and supernatural calamities. Considers questions of race, gender, sexuality, colonialism, trauma, memory, witness, and genocide. Intended for students with prior creative writing experience. Students taking graduate version complete additional assignments. Limited to 15.

Critical Worldbuilding (CMS.307), MIT, Fall 2017

Course Description : Studies the design and analysis of invented (or constructed) worlds for narrative media, such as television, films, comics, and literary texts. Provides the practical, historical and critical tools with which to understand the function and structure of imagined worlds. Examines world-building strategies in the various media and genres in order to develop a critical and creative repertoire. Participants create their own invented worlds. Students taking graduate version complete additional assignments. Limited to 13.

Alexander Chee:

Imaginary Countries (ENGL 87.04), Dartmouth College, Fall 2017

Course Description : This course introduces the techniques used in speculative fiction—literary novels and stories using either science fiction, magical realism, or myth, or a mix of these, so the author can reinvent a country’s history, the country itself—even the world. We will read for technique, and discuss the effects these fictions achieve with their structures and the narrative and aesthetic strategies deployed. Students will write and workshop two stories. Readings may include: Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, Andrew Sean Greer’s “Darkness”, Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go, Chris Adrian’s “Every Night For A Thousand Years”, Anne Carson’s Autobiography of Red, Yiyun Li’s “Immortality”, Jan Morris’ Hav, Toni Morrison’s Sula, and Carmen Machado’s “The Husband Stitch.”

Jeffery Renard Allen:

Shadow Narration (ENG8510), University of Virginia; Fall 2017

Course Description : In this course we will look at experimentation in prose narrative over the last one hundred years or so, using Marcel Proust’s 1913 novel Swann’s Way as a frame for this examination. Given that this is a course primarily designed for writers, we will engage in close readings of a number of exemplary texts as way to think through an understanding of certain key narrative concerns and techniques that define modernist and postmodernist prose. Texts include book-length works of fiction and nonfiction by Mavis Gallant, Ishmael Reed, Micheline Aharonian Marcom, Clarice Lispector, Italo Calvino, Jorge Luis Borges, Michael Ondaatje, Edouard Leve, John Edgar Wideman, and Marlene van Niekerk. As we will see, shadow narration represents an extensive tradition of experimentation that stretches back to the origins of both spoken and written narrative. At the same time, it represents a range of narrative gestures and strategies that allow for the layering of subtext. Indeed, one might best think of subtext as shadow narration, as the totality of meaning and implication that accompanies the narrative as written on the page.

The Fantastic (ENLP4550), University of Virginia, Fall 2017

Course Description : The course will look at the fantastic as a narrative in fiction and film. We will read some representative texts, both classic and contemporary, and from here and abroad. Assignments will include short response pieces to the assigned readings and films, as well as creative exercises based on the readings and screenings. Texts will include short stories, novels, graphic novels, and films by Helen Oyeyemi, Stephen Graham Jones, Neil Gaiman, Angela Carter, Julio Cortazar, Silvina Ocampo, David Cronenberg, Anais Nin, Larry Cohen, Juan Rulfo, Leonara Carrington, Hideo Nakata, J.G. Ballard, Anais Nin, Rene’ Depestre, Philip K. Dick, Souleymane Cisse, and Colson Whitehead. Genres will include the undead (zombies, vampires, and ghosts), shapeshifters, speculative fiction, surrealism, expressionism, magical realism, and Afro-Futurism, among others. From time to time over the course of the semester, we will draw a few critical texts to inform our discussion, including Tzevtan Todorov’s important study The Supernatural .

Lisa Russ Spaar:

The Poetics of Ecstasy (ENG8520), University of Virginia; Fall 2017

Course Description : The Greek word ekstasis signifies displacement, trance—literally, “standing elsewhere.” In this seminar class, serious makers and readers of poems will explore the poetics of fervor—erotic, visionary, psychosomatic, negative, religious, mystical. When the precincts of poetry and rapture intersect, what transpires? What is possible? What is at stake and why does it matter? We will read widely and deeply across cultures and time, including work by Dickinson, Whitman, Carson, Hopkins, Sappho, Keats, Juan de la Cruz, Rilke, Mirabai, Rumi, Ginsberg, Rimbaud, Teare, Young, and other ancient, modern, and contemporary writers who have explored the experience of being beside one’s self in the transport of ecstasy. Key critical texts include readings from Anne Carson’s Eros the Bittersweet , Michel de Certeau’s The Mystic Fable , Georges Bataille’s Erotism: Death and Sensuality , and Roland Barthes’s A Lover’s Discourse.

Forms: Poetry, Memoir, & Nonfiction (ENG 650-3), Syracuse University, Fall 2017

Course Description : We’ll read and discuss eleven memoirs, plus excerpts of a few others. Work for the semester will consist of reading and being engaged with the books. Assignments will include: small creative projects and in-class writing sprinkled through the semester; a presentation on one of the writers; and a final paper, memoir, or 10 poems. Readings may include (a) poems by Roger Fanning, Louise Gluck, Robert Hass, Terrance Hayes, Seamus Heaney, Yusef Komunyaaka, William Matthews, Heather McHugh, Pablo Neruda, Craig Raine, Charles Simic, and Dean Young; (b) fiction by George Saunders; (c) essays by James Wood, and (d) a memoir by Elif Batuman.

Kaitlyn Greenidge:

Forms: Ghost Stories (ENG 650-9), Syracuse University, Fall 2017

Course Description : In this class, we will explore the use of ghosts and ghost stories in literature. We will begin by establishing the elements in classic ghost stories of the nineteenth century and move on to modern interpretations in contemporary fiction. We will also explore ghosts in folklore. During this class, we will explore the symbolism of ghosts in literature and attempt to uncover why this genre of storytelling remains popular. Students will be required to write creative and/or critical response papers, make oral presentations, and produce either a final 10-page ghost story of their own or a critical essay, subject to the instructor’s approval.

Justin Torres:

Adaptation, Inspiration, and Reinvention: Queer Lit and Film (English 118C), UCLA, Fall 2017

Course Description : This course will ask what are the costs, and what are the compensations, of adaptation both in art and in life? We will look at a wide range of literary works with queer themes and their cinematic adaptations: Billy Budd / Beau Travail, The Color Purple, The Haunting of Hill House, and Kiss of the Spider Woman are just some examples. How have filmmakers like Almodovar, Campion, Jarman, and Fassbinder, approached literary adaptation? What, if anything, is queer about adaptation?

Anne Fadiman:

Writing About Oneself (ENGL 455), Yale University, Spring 2018

Course Description : This is a reading and writing class—part lecture, part seminar, part workshop—in which students explore a series of themes (including love, loss, family, and identity) both by writing about their own lives and by reading British and American memoirs, autobiographies, letters, and personal essays.

First-person writing is a peculiar blend of candor, catharsis, narcissism, and indiscretion. The purpose of this class is to harness these elements with sufficient rigor and imagination that self-portraiture becomes interesting to others as well as to oneself. Each week, we will read two works on a particular theme, one “old” (ranging from four decades to more than two centuries ago) and one “new” (mostly from the last two decades) —a coupling designed to erode the traditional academic boundaries between eras and between “ought” and “want” reading. (For instance, when we consider the theme of love, we will read excerpts from H. G. Wells’s On Loves and the Lover-Shadow and Joyce Maynard’s At Home in the World , and write personal essays on an aspect of love, not necessarily romantic.) Readings will include works by James Baldwin, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Joan Didion, Lucy Grealy, Maxine Hong Kingston, Mary McCarthy, James Thurber, and Virginia Woolf, among others. Our connections to the readings will be reinforced by several author visits. By writing a thousand-word first-person essay every other week, students will face the same problems the authors in our syllabus have faced, though they may come up with very different solutions. Students will critique each other’s work in class and by e-mail. Each student will have at least five individual conferences with me, most of them an hour long, in which we’ll edit your work together.

Claudia Rankine:

Constructions of Whiteness (ENGL 233), Yale University, Spring 2018

Course Description : An interdisciplinary approach to the understanding of whiteness. Discussion of whiteness as a culturally constructed and economic incorporated entity, which touches upon and assigns value to nearly every aspect of American life and culture.

Class and Gender (ENGL 504), USC, Fall 2016

Course Description : This course will consider the construction of whiteness in contemporary America.

Historical Overview 1. The History of White People , by Nell Irvin Painter (W. W. Norton) 2. Look, A White!: Philosophical Essays on Whiteness , by George Yancy (Temple University Press) 3. The Invention of the White Race, Volume 1: Racial Oppression and Social Control , by Theodore W. Allen and Jeffrey B. Perry 4. The Invention of the White Race, Volume 2: The Origin of Racial Oppression in Anglo- America , by Theodore W. Allen and Jeffrey B. Perry 5. Dear White America , by Tim Wise (City Lights Open Media) 6. Working Towards Whiteness: How America’s Immigrants Became White: The Strange Journey from Ellis Island to the Suburbs , David R. Roediger 7. Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States , by Kenneth T. Jackson (Oxford University Press)

Entertainment & Media 1. White: Essays on Race and Culture by Richard Dyer (Oxford) 2. White Girls , by Hilton Als (McSweeney’s) 3. The Devil Finds Work , by James Baldwin (Vintage)

White Activism (And Failures) 1. Good White People: The Problem with Middle-Class White Anti-Racism , by Shannon Sullivan (State University of New York Press) 2. Revealing Whiteness: The Unconscious Habits of Racial Privilege , by Shannon Sullivan (Indiana University Press) 3. Between Barack and a Hard Place , by Tim Wise (Soft Skull Press)

Confronting Whiteness: Systemic Racism, Economic Inequality, Prison Complex, Housing Discrimination 1. The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit , by Thomas J. Sugrue (Princeton University Press) 2. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness , by Michelle Alexander (The New Press) 3. Race Matters , by Cornell West (Vintage) 4. “The Condition of Black Life is One of Mourning,” by Claudia Rankine, (New York Times Op-Ed)

Literary Criticism 1. Reading Race: White American Poets and the Racial Discourse in the Twentieth Century , by Aldon Lynn Nielsen (University of Georgia Press) 2. Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination , by Toni Morrison (Vintage)

Memoirs & Personal Narratives 1. White Like Me: Reflections on Race from a Privileged Son , by Tim Wise 2. Detroit: An American Autopsy , by Charlie LeDuff (Penguin) 3. Between the World and Me , by Ta-Nehisi Coates (Spiegel & Grau) 4. Times Square Red, Times Square Blue , by Samuel R. Delany (New York University Press)

Poetry 1. Delusions of Whiteness in the Avant-Garde , by Cathy Park Hong (Lana Turner onine) 2. White Papers , by Martha Collins (Pitt Poetry Series) 3. The Forage House , by Tess Taylor (Red Hen Press) 4. The Cloud Corporation , by Timothy Donnelly (Wave Books) 5. Metropole , by Geoffrey G. O’Brien (University of California Press)

The Situation of Writing (ENG 392), Northwestern University, Fall 2015

Course Description : Writers are the inheritors, perpetuators, and innovators of literary culture. In this class we will explore the contemporary landscape of creative writing, with a particular emphasis on the role of small presses and small journals and magazines. We will explore how venues for writing, including online publications, shape contemporary literature. We will discuss the distinct missions and personalities of a number of presses, while exploring the relationship between press and practitioner. This course is designed especially for students who hope to forge careers as writers, and it will challenge all participants to think creatively about the place of literature in our society.

Stuart Dybek:

Advanced Creative Writing: Fabulous Fictions (ENG 307), Northwestern University, Winter 2018

Course Description : Fabulous Fictions focuses on writing that departs from realism. Often the subject matter of such writing explores states of mind that are referred to as non-ordinary reality. A wide variety of genres and subgenres fall under this heading: fabulism, myth, fairy tales, fantasy, science ction, speculative ction, horror, the grotesque, the supernatural, surrealism, etc. Obviously, in a mere quarter we could not hope to study each of these categories in the kind of detail that might be found in a literature class. The aim in 307 is to discern and employ writing techniques that overarch these various genres, to study the subject through doing—by writing your own fabulist stories. We will read examples of fabulism as writers read: to understand how these ctions are made—studying them from the inside out, so to speak. Many of these genres overlap. For instance, they are all rooted in the tale, a kind of story that goes back to primitive sources. They all speculate: they ask the question, What If? They all are stories that demand invention, which, along with the word transformation, will be a key term in the course. The invention might be a monster, a method of time travel, an alien world, etc., but with rare exceptions the story will demand an invention and that invention will often also be the central image of the story. So, in discussing how these stories work we will also be learning some of the most basic, primitive moves in storytelling. To get you going I will be bringing in exercises that employ fabulist techniques and hopefully will promote stories. These time-tested techniques will be your entrances—your rabbit holes and magic doorways—into the gurative. You will be asked to keep a dream journal, which will serve as basis for one of the exercises. Besides the exercises, two full-length stories will be required, as well as written critiques of one another’s work. Because we all serve to make up an audience for the writer, attendance is mandatory.

Vievee Francis:

Engaging Hybridity: Race, Gender, Genre (ENGL 87.10), Dartmouth College, Fall 2017

Course Description : In this course, from the graphic novel written by poets to the narrative collage to the imagined tweets of Anne Sexton, all of the contemporary readings and visual materials dare take on social, political and cultural engagement with this anxious moment in history. The stakes are high. We will consider the diverse and provocative creative work of Mat Johnson ( Incognegro ), Maggie Nelson ( Bluets ), Sebastian Matthews ( Beginner’s Guide to A Head On Collision ), Claudia Rankine ( Citizen ), Tyehimba Jess ( Olio ), Kwame Dawes ( Duppy Conqueror ), A. Van Jordan ( The Cineaste ) and Dee Matthews ( Simulacra ), among others, to explore hybrid genres (such as the prose poem) and other sites of artistic production met through intersection, exchange, conflict, inhabitance, resistance, and cultural address. These writers and artists may work as well in more than one distinct genre and or take on hybridity of forms and approaches within a particular genre. We will respond to the readings (and visual material) by creating our own. Further, this class will encourage topical discussion and readings will include author interviews, commentaries, and critical analyses of their process and production, as we ask what kind of parameters, if any, art, particularly literature, truly requires? Are they porous enough? Is there a skein where a wall is necessary? What role does identity play in the choice to cross such borders?

Kevin Young:

Special Topics in Creative Writing: The Lyric (ENGCW379W-01P), Emory University, Fall 2016

Course Description : The Lyric will explore recent adventures in the ancient form of the lyric, that primal mode of song and sustenance. In this advanced course, students will study and write in a range of forms, from the manifesto to the three-line novel, from sonnets to erasures, the prose poem and the lyrical essay, in order to discover new paths in reading and writing. They will emerge with their own work and their own sense of the English-language tradition, the avant-garde, and the counterculture.

We will also explore primary materials, discovering many of these works in their original form in the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library (the Rose Library) and its Raymond Danowski Poetry Library, where I serve as curator. The course reflects the broad scope of the Danowski Poetry Library itself, which, despite its name, also includes prose, counterculture, the roots of the lyric essay, and artists’ books.

Besides weekly reading and writing assignments, students also will be monitoring new media, including Twitter, where much of this new lyricism might be found. The result would also involve a possible web presence as students familiarize themselves with the latest in digital scholarship. The course concludes with students curating a final project. All these innovations are meant to help students understand the widespread place of the lyric in culture. In its fresh mix of digital and dust jackets, new media and material culture, The Lyric Essay’s investigations and instigations will help us discover the lyric mode in the modern world, and ourselves.

Natasha Trethewey:

Poetry and the Muse of History (ENGCW190-000), Emory University, Fall 2016

Course Description : A freshman-only workshop for students who have had little or no experience in creative writing. Not a prerequisite for other courses in the program. The course will take an in-depth look at poems that seek to engage and document our stories—those histories both public and private, real and imagined. We will discuss the ways that some poets have used personal and public history in their work, define some strategies for using information gathered from our research, and begin writing some poems that engage those histories to which we have some connection. In all of this, we will focus on cultivating the craft of poetry with particular emphasis on what makes a poem work—metaphor, image, musicality, voice, etc. We will work to develop the critical language necessary for discussing each other’s work and for critically approaching our own poems during the important process of revision.

Vikram Chandra:

The Short Story (English 180H), University of California, Berkeley, Fall 2017

Course Description :

The lyf so short, the crafte so longe to lerne. . . —Chaucer

This course will investigate how authors craft stories, so that both non-writers and writers may gain a new perspective on reading stories. In thinking of short stories as artefacts produced by humans, we will consider—without any assertions of certainty—how those people may have experienced themselves and their world, and how history and culture may have participated in the making of these stories. So, in this course we will explore the making, purposes, and pleasures of the short story form. We will read—widely, actively and carefully—many published stories from various countries in order to begin to understand the conventions of the form, and how this form may function in diverse cultures. Students will write a short story and revise it; engaging with a short story as a writer will aid them in their investigations as readers and critics. Students will also write two analytical papers about stories we read in class. Attendance is mandatory.

Lyn Hejinian:

Slow Seeing / Slow Reading (English 190), University of California, Berkeley, Fall 2016

Course Description : This is a seminar in the poetics of reading poems and seeing paintings. Over the course of the semester, students will undertake prolonged, exploratory, multi-contextual readings of a selection of recent and contemporary “difficult” poems. Each student will also undertake a similar engagement with a 20th/21st century painting of his or her choice from the permanent collection of the Berkeley Art Museum. Poems by W. B. Yeats, Claude McKay, Rae Armantrout, Elizabeth Bishop, Ed Roberson, Marianne Moore, Juliana Spahr, and Susan Howe are among the poems that will be considered. Paintings by Philip Guston, Hans Hoffman, Willem de Kooning, and Helen Frankenthaler are among the paintings that will be available for repeated viewing. The individual poems and paintings will be read/seen against the backdrop of their historical moment and contextual purport and in conjunction with assigned critical texts, but students will be expected to conduct their own research, using primary and secondary sources in the process of coming to relevant, meaningful readings/seeings of the works. Students will be asked to maintain a reading/seeing journal and to write two critical papers.

“English 190: Slow Seeing / Slow Reading” is an experiment, and is offered as a collaboration between Lyn Hejinian, of the English Department, and Apsara DiQuinzio, of the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive. Among the outcomes of the course will be an exhibition at BAMPFA that will be part of a new exhibition series at the museum titled Cal Conversations; the materials for the “Slow Seeing / Slow Reading” exhibition will be determined by the seminar’s students and include some of their course writings.

21st-Century American Writing (English 134), University of California, Berkeley, Fall 2016

Course Description : In this course we will take seriously the notion of “the contemporary” as that which coexists with us and is relevant to our times—or our spaces. All the works on the syllabus have been published in the past ten years, most within the past three. They offer examples of current literature’s attempts to dwell in the present while thinking both about that temporal situation (“the present”) and that activity (“dwelling”). Not all the works are readily categorizable as to genre; the syllabus is weighted toward prose, but some of the prose works are, arguably, poetry. In many, communication, and even humanness, appear to be in question. Or, perhaps, they are evolving into new forms. But, as many of the books on the course reading list suggest, one thing that is not vanishing is the centrality of desire in the experiencing of lived life.

The first two books on the syllabus are Open City , by Teju Cole, and SPRAWL , by Danielle Dutton. It is suggested that at least the first, and preferably both, be purchased in advance, so that the course can proceed without anyone’s falling behind.

Book List: Brown, Brandon: Top 40 ; Clevidence, Cody-Rose: Beast Feast ; Coates, Ta-Nehisi: Between the World and Me ; Cole, Teju: Open City ; Dutton, Danielle: Sprawl ; Díaz, Junot: The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao ; Gladman, Renee: Event Factory ; Lerner, Ben: 10:04 ; Moten, Fred: The Service Porch ; Notley, Alice: Certain Magical Acts ; Rankine, Claudea: Citizen: An American Lyric ; Robertson, Lisa: Nilling ; Spahr, Juliana and Buuck, David: The Army of Lovers

Geoff Dyer:

Reporting and Literature (ENGL 620), USC, Spring 2017

Course Description : At what point does reporting become literature? How does the obligation to record facts or document events sit alongside the artistic urge to shape and embellish? To what extent can a highly individual personal style conflict with reliability? These are some of the questions to be raised in a survey of landmark books by—among others—Gay Talese, Janet Malcolm, Rebecca West, Dexter Filkins, Norman Mailer and Ryszard Kapuscinski. We will also consider some photographic books, especially collaborations between writers and photographers such as A Fortunate Man by John Berger and Jean Mohr and Let Us Now Praise Famous Men by James Agee and Walker Evans. It was Evans, after all, who expressed the crux of the matter most concisely by making a distinction between documentary and what he insisted on calling “documentary style.”

Jim Shepard:

Motherhood and Horror: The Movie (ENGL 380), Williams College, Spring 2018

Course Description : Horror might be the most durable of film genres as well as the genre that’s done the most work in terms of transforming the medium as a whole, and its transgressive nature has insured it attention, giving its most famous texts enormous cultural reach when it comes to ongoing conversations as to what defines evil, what constitutes normality, or what comprises the taboo. A look at the particular anxieties the genre has—especially recently—mobilized through its portraits of mothers and motherhood. The course will also touch on other genres that suggest an unspeakable invisible beneath the maternal quotidian. Films to be studied will include Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho , Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby , Jee-Woo Kim’s A Tale of Two Sisters , Juan Antonio Bayona’s The Orphanage, Jennifer Kent’s The Babadook, James Cameron’s Aliens, Michael Curtiz’s Mildred Pierce, Mike Nichols’ Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, Juan Carlos Fresnadillo’s 28 Weeks Later, and Veronika Franz’s and Severin Fiala’s Goodnight Mommy.

Hollywood Film (ENGL 204), Williams College, Fall 2017

Course Description : For almost a century, Hollywood films have been the world’s most influential art form, shaping how we dress and talk, how we think about sex, race, and power, and what it means to be American. We’ll examine both the characteristic pleasures provided by Hollywood’s dominant genres—including action films, horror films, thrillers and romantic comedies—and the complex, sometimes unsavory fantasies they mobilize. We will do this by looking carefully at a dozen or so iconic films, probably including Psycho ; Casablanca ; The Godfather ; Schindler’s List ; Bridesmaids ; Groundhog Day , and 12 Years a Slave . In addition to the assigned reading, students will be required to attend free screenings of course films on Sunday evenings at Images Cinema.

Karen Shepard:

Imagination and Authority (ENGL 154), Williams College, Fall 2017

Course Description : A course on the subject of who gets to write about what when it comes to fiction. Among the questions we’ll be taking up: What are the outer boundaries of those imaginative acts that should be attempted? The central goal of this course is to teach you how to write a well-argued and interesting analytical paper. We will spend most of our class time actively engaged in a variety of techniques to improve your critical reasoning and analytical skills, both written and oral. Though the skills you learn will be applicable to other disciplines, this is also a literature class, designed as well to prepare you for upper level courses in the English Department.

Frank Bidart:

Great Works of Poetry (English 115), Wellesley College, Spring 2018

Course Description : We live in a culture that has lost any collective agreement or wisdom about what a poem is, or why we read poetry. Yet many of the greatest things ever written are poems. How can we read poems so that we experience them as brilliantly made things, as powerful, seductive works of art? This course will look at great poems from the whole history of poetry in English (and at some poems in translation). Why read poetry? This course attempts to tackle that question head-on, with an emphasis on the pleasure and insight great art brings.

Contemporary American Poetry (English 253), Wellesley College, Fall 2017

Course Description : A survey of the great poems and poets of the last 75 years, a period of immense invention and brilliant creation. Our poets articulate the inside story of what being an American person feels like in an age of mounting visual spectacle, and in an environment where identities are suddenly, often thrillingly, sometimes distressingly, in question. Without repudiating the great heritage of Modernism, how have the poets that followed added to it? Poets include: Robert Lowell, Elizabeth Bishop, Allen Ginsberg, Sylvia Plath, the poets of “The New York School” (John Ashbery, Frank O’Hara), Adrienne Rich, Louise Glück, Robert Pinsky, Anne Carson, Yusef Komunyakaa, Rita Dove, Dan Chiasson, and others.

Tiphanie Yanique:

Girls: Character Development Across Genres (ENGL 312), Wesleyan University, Fall 2017

Course Description : In this special topics course we will study the craft of character building. We will focus on how novelists, short story writers, film makers, poets and essayists over the 20th and the beginning of 21st century have crafted the female child in literature to have a broad but challenging conversation about narration, voice, subjectivity, and agency. We will use the course materials and discussions as impetus to write characters that challenge easy tropes while also contributing to ongoing conversations about literature and writing.

Possible texts include : Girls dir by Lena Dunham Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov Pippi Longstocking by Astrid Lindgren The Woman Warrior by Maxine Hong Kingston How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents by Julia Alvarez The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison White Teeth by Zadie Smith Of Love and Other Demons by Gabriel Garcia Marquez Cowboys and East Indians by Nina McConigley

Living Room: Place and Structure in the Novel and Short Story (ENGL 318), Wesleyan University, Spring 2018

Course Description : In this special topics course we will study the craft of structure and setting. We will focus on how novelists and short story writers have made use of architecture and the environment as a means to shape story, reveal character, and direct plot. We will apply our learning to our own fiction by writing work that reveals a sophisticated awareness of the relationship between content and form.

Possible texts include : The Book of Unknown Americans by Cristina Henriquez Blindness by Jose Saramago A House for Mr. Biswas by VS Naipaul The Turner House by Angela Flournoy

Hisham Matar:

Estrangement and Exile in Global Novels (ENGL BC3192), Barnard College, Fall 2017

Course Description : “I would never be part of anything. I would never really belong anywhere, and I knew it, and all my life would be the same, trying to belong, and failing. Always something would go wrong. I am a stranger and I always will be, and after all I didn’t really care.” —Jean Rhys.

This course examines the experiential life of the novelist as both artist and citizen. Through the study of the work of two towering figures in 20th century literature, we will look at the seemingly contradictory condition of the novelist as both outsider and integral to society, as both observer and expresser of time’s yearnings and passions. In different ways and with different repercussions, Jean Rhys and Albert Camus were born into realities shaped by colonialism. They lived across borders, identities and allegiances. Rhys was neither black-Caribbean nor white-English. Albert Camus could be said to have been both French and Algerian, both the occupier and the occupied, and, perhaps, neither. We will look at how their work reflects the contradictions into which they were born. We will trace, through close reading and open discussion, the ways in which their art continues to have lasting power and remain, in light of the complexities of our own time, vivid, true and alive. The objective is to pinpoint connections between novelistic form and historical time. The uniqueness of the texts we will read lies not just in their use of narrative, ideas and myths, but also in their resistance to generalization. We will examine how our novelists’ existential position, as both witnesses and participants, creates an opportunity for fiction to reveal more than the author intends and, on the other hand, more than power desires.

Listen: Claudia Rankine talks to Paul Holdengräber about objectifying the moment, investigating a subject, and accidental stalking.

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Emily Temple

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

The Living Infinite

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

The 19 best online writing classes led by famous authors, including Malcolm Gladwell, Neil Gaiman, and Judy Blume

When you buy through our links, Business Insider may earn an affiliate commission. Learn more

- Strong communication and writing skills will help you succeed in any profession.

- Online classes are an affordable way to learn writing tips and receive feedback on your work.

- All the classes on this list are taught by award-winning writers with decades of experience.

Good writing skills can take you far (just take it from a business major who wormed her way into an editorial career). Strong written communication skills can help you land a job or move up in your career , but good writing doesn't come easily or instinctively to everyone. As with any skill, you won't get any better at writing simply by reading books or watching videos about it.

Online classes from e-learning platforms like MasterClass and Skillshare are affordable, flexible ways to not only learn the proper strategies but also practice and receive feedback on your writing. And who better to learn from than actual published authors, writers, and editors?

The following classes are all taught by accomplished, award-winning writers who have decades of experience in communicating ideas, telling stories, and captivating audiences. Some specialize in fiction, while others employ storytelling tricks to make even the driest facts shine.

If you see the word "creative" in the title, don't immediately dismiss the class. All the courses have valuable lessons to learn for making your writing more effective, whether you're in a creative industry or not.

19 writing classes taught by experienced authors, writers, and editors:

Neil gaiman's masterclass on the art of storytelling.

The teacher: Award-winning writer Neil Gaiman (" The Sandman ," " Coraline ," " American Gods ") has dabbled in everything from novels and comic books to film and audio theatre. The course: Gaiman covers the fundamentals of storytelling, from finding your voice to fleshing out your characters. The price: $180 ($15 per month) for an annual MasterClass membership.

Joyce Carol Oats' MasterClass on the Art of the Short Story

The teacher: Joyce Carol Oates is the author of over 58 novels (" We Were the Mulvaneys ," " Blonde ," " The Accursed "), as well as countless short stories, essays, and articles. She is also a former professor of creative writing at Princeton University .

The course: Oates' class helps students finetune their storytelling instincts for short story writing, from learning how to observe the world around them to nailing down structure and form.

The price: $180 ($15 per month) for an annual MasterClass membership.

Judy Blume's MasterClass on Writing

The teacher: Judy Blume's beloved children's books (" Are You There God? It's Me, Margaret ," " Superfudge ") have sold millions of copies, and Blume has written over 25 novels. She's also the recipient of the 2004 National Book Foundation medal for distinguished contribution to American letters, as well as numerous other awards.

The course: With a focus on writing for young readers, Blume's course dives into developing ideas, creating plot structure, and even pitching book ideas to editors, and even dealing with issues like rejection or censorship. The price: $180 ($15 per month) for an annual MasterClass membership.

N.K. Jemisin's MasterClass on Fantasy and Science Fiction Writing

The teacher: NK Jemisin, a Hugo Award winner for three consecutive years for her " Broken Earth " trilogy, is an an acclaimed science fiction and fantasy author. The course: Jemisin's course, geared towards sci-fi/fantasy writing, teaches students how to build a believable world from scratch (including macro and micro details), create characters that truly feel relatable even in fantastical settings, and find a literary agent. The price: $180 ($15 per month) for an annual MasterClass membership.

Creative Nonfiction: Write Truth with Style

The teacher: Susan Orlean has been a staff writer at The New Yorker since 1992 and is the author of eight books, including New York Times bestseller " Rin Tin Tin " and " The Orchid Thief ," which was later adapted into Spike Jonze's "Adaptation," (in which Meryl Streep portrayed Orlean). The course: The best nonfiction makes facts compelling and interesting to read, but it's not easy to do this. This course takes students through Susan Orlean's writing process, from finding a topic to making final edits, and helps them polish their own creative processes. The class project is a 1,000-word profile on someone you find mysterious. The price: Free with 14-day Skillshare trial; $8.25 per month or $19 per month after trial ends.

Malcolm Gladwell's MasterClass on Writing

The teacher: Malcolm Gladwell has written for "The New Yorker" since 1996. His fascinating books, which include " The Tipping Point ," " Blink ," and " Outliers " reveal the most unexpected insights into our world. "The Tipping Point" was named as one of the best books of the decade by Amazon customers, The A.V. Club, and The Guardian, and was Barnes & Noble's 5th bestselling nonfiction book of the decade.

The course: In 24 lessons, you'll learn how to find, research, and write stories that capture big ideas. This is Gladwell's first-ever online class, where he analyzes his own works to reveal his unique creative process. He also answers select student questions during virtual office hours.

Roxane Gay's MasterClass on Writing for Social Change and Creative Writing: Crafting Personal Essays with Impact

The teacher: On top of writing bestselling memoirs like " Bad Feminist " and " Hunger: A Memoir of (My) Body ," Roxane Gay is a professor and New York Times columnist , making her as experienced an author as she is an educator. The course: If you want to see change in the world, strong storytelling skills can help you get there. Gay's MasterClass teaches you how to tap into your identity, figure out your voice, and write about emotionally hard subjects with care, so that you can get people on board with the broader visions you have for improving the world.

Roxane Gay also teaches a short Skillshare class on crafting impactful personal essays from start to finish. You can read a review of it here .

The price: $180 ($15 per month) for an annual MasterClass membership. Free with 14-day Skillshare trial; $8.25 per month or $19 per month after trial ends.

Daniel José Older's Storytelling 101: Character, Conflict, Context, Craft

The teacher: Daniel José Older is the bestselling author of the " Bone Street Rumba " urban fantasy series and the YA novel " Shadowshaper ." "Shadowshaper" was a "New York Times" Notable Book of 2015 and named one of Esquire's "80 Books Every Person Should Read." Older's short stories and essays have appeared in the Guardian, NPR, and a number of other sites. The course: This short 40-minute class breaks down the fundamentals of narrative storytelling and what makes a story different from a mere anecdote. Learn the "4 C's" of storytelling and see them in action in one of the teacher's own short stories. The fun final project is to write a short story about something that happened on a single block in your hometown over the course of one hour.

The price: Free with 14-day Skillshare trial; $8.25 per month or $19 per month after trial ends

Steven Heller's The Designer's Guide to Writing and Research

The teacher: Steven Heller writes the Visuals column for the "New York Times Book Review" and is the editor of the AIGA Journal of Graphic Design. A former "New York Times" art director , he is the author, co-author, or editor of over 170 books on design and popular culture , and also regularly contributes to design publications. The course: Geared towards designers, this course illuminates the parallels between writing and design. You'll learn about the professional importance of research and writing to designers today, best practices for developing your voice, and creative ways to communicate. The final project is a 500-word essay on an object in your wallet, bag, or pocket.

David Sedaris’s MasterClass on Storytelling and Humor

The teacher: If you want to inject your writing with a dash of comedy, David Sedaris — "The New Yorker" essayist and author of " Me Talk Pretty One Day ," " Calypso ," and " The Best of Me " — is one of the best people to teach you how to do it.

The course: Beyond covering tips and tricks for writing eye-grabbing openings and endings with huge payoffs, Sedaris also gives his advice on finding humor in the darkest moments of our lives.

Amy Tan's MasterClass on Fiction, Memory, and Imagination

The teacher: Most known for her bestselling novel " The Joy Luck Club " (which spent 40 weeks on the "New York Times" bestseller list), Amy Tan is an inspiration to anyone who's started exploring their writing voice later in life — she started at age 33 and published her famed debut novel a mere few years later. Tan went on to write many other books, including " The Bonesetter's Daughter " and " The Kitchen God's Wife: A Novel ." The course: With a focus on utilizing your most powerful memories, this course teaches you how to find your voice as well as sharpen your story with compelling beginnings and endings. The price: $180 ($15 per month) for an annual MasterClass membership.

Shani Raja's Writing With Flair: How To Become An Exceptional Writer

The teacher: Shani Raja is a former Wall Street Journal editor who has written for The Economist, Financial Times, and Bloomberg News. He has also taught advanced writing skills to professionals and edited for leading global companies like Microsoft, IBM, and PwC. The course: Another bestseller from Shani Raja, this course promises to "dramatically improve the quality of your writing in as little as days or weeks" through a few key principles. Both new students and experienced writers have benefitted from the course, which teaches you how to sharpen your words and command the reader's attention.

Raja also has a Udemy course on the four levels of writing mastery .

The price: Both of Raja's Udemy courses are $109.99 each.

Margaret Atwood's MasterClass on Creative Writing

The teacher: Of " The Handmaid's Tale " fame, Margaret Atwood has been titled the "Prophet of Dystopia" for works such as " Oryx and Crake " and the "Handmaid's Tale" sequel, " The Testaments: A Novel ." The course: Atwood's MasterClass "covers the general points of interest for writers — how to get started, handle the middle of a story, develop characters, craft dialogue, and address writers' block — as well as more specific queries, like research and maintaining historical accuracy," according to Insider senior reporter Mara Leighton. You can read her full review of the course here . The price: $180 ($15 per month) for an annual MasterClass membership.

Simon Van Booy's The Writer's Toolkit: 6 Steps to a Successful Writing Habit

The teacher: Simon Van Booy's short story collection " Love Begins in Winter " won the 2009 Frank O'Connor International Short Story Award. He has written two other short story collections as well as three anthologies of philosophy, and his work has been translated into over a dozen languages throughout the world. In 2013, he founded Writers for Children, a project that helps young people build confidence in their storytelling abilities through annual awards. The course: Writing should be approachable and fun, not torturous. By optimizing your space for your writing style, creating a daily writing routine, and acting on inspiration, you can build a long-term writing process to rely on for years to come. This short video course teaches you how.

Jennifer Keishin Armstrong's Finding Your Writing Voice: How to Express Your Unique Self in Your Work

The teacher: Jennifer Keishin Armstrong is a former Entertainment Weekly writer and current TV columnist for BBC Culture who has also written for The New York Times Book Review, Fast Company, New York's Vulture, and The Verge. She wrote the New York Times bestseller " Seinfeldia: The Secret World of the Show About Nothing that Changed Everything ." The course: You don't have to lose your unique personality when you write; in fact, it's what will make your writing stand out in the crowd. Using pop culture icons like Beyoncé and Britney Spears, the class discusses different voices and explores ways to take chances with your writing.

The price: Free with 14-day Skillshare trial; $8.25 per month or $19 per month after trial ends.

Salman Rushdie’s MasterClass on Storytelling and Writing

The teacher: Winner of the Man Booker Prize, Salman Rushdie is known for his mystical world-building and genre-bending plotlines as seen in books like " Quichotte ," " Midnight's Children ," and " Shame ."

The course: Rushdie provides tips on creating fleshed-out characters, believable surrealist worlds, and an air-tight plot. This is a great course for those who have lots of fantastical ideas but struggle to ground them into a cohesive story.

Clare Lynch's Writing With Confidence: Writing Beginner To Writing Pro

The teacher: Dr. Clare Lynch is a former Financial Times journalist who teaches academic writing and professional communication at the University of Cambridge. She has written for organizations like Deutsche Bank, Microsoft, and UBS and is the author of the business-writing blog Good Copy, Bad Copy . The course: Learn powerful principles that can be applied to all types of writing, including emails, speeches, news writeups, and even presentations. The course takes you through fundamentals from techniques to beat writer's block to lessons on getting readers hooked and creating a clear, persuasive angle.

The price: $109.99.

Joyce Maynard's Writing Your Story

The teacher: The author of 17 books (including novels and memoirs), Joyce Maynard has worked as a "New York Times" reporter and a contributor to outlets like NPR and "Vogue." Her books include " Labor Day ," " The Good Daughters ," and " Under the Influence ."

The course: Focusing on memoir writing, Maynard explains the difference between simply retelling events that happened to you and exploring your journey as a protagonist. She also covers some of the biggest questions that come up when writing about yourself, from what to cut to dealing with fears of judgment so that you can present a narrative that's authentic to readers.

The price: $89 for the course, or $11 per month for a CreativeLive membership.

Wesleyan University's Creative Writing Specialization

The teachers : Salvatore Scibona was named one of "The New Yorker's" "20 under 40: Fiction Writers to Watch" and is the author of 2008 National Book Award finalist " The End ," the research for which he conducted while on a Fulbright Fellowship.

Amy Bloom , author of two "New York Times" bestsellers and three collections of short stories, has written for "The New Yorker," "The New York Times Magazine," and "Vogue," among many other publications, and has won a National Magazine Award for Fiction. Her work has been translated into fifteen languages.

Brando Skyhorse is an Associate Professor of English at Indiana University in Bloomington who won the 2011 PEN/Hemingway Award and the 2011 Sue Kaufman Prize for First Fiction for his debut novel " The Madonnas of Echo Park ."

Amity Gaige is the author of three novels, " O My Darling ," " Sea Wife ," and " Schroder ," which was shortlisted for The Folio Prize in 2014. To date, "Schroder" has been published in eighteen countries.

The course: This specialization created by Wesleyan University consists of four courses (each taught by a teacher listed above) and covers elements of three major creative writing genres: short story, narrative essay, and memoir. It culminates in a challenging capstone project in which you'll draft, rewrite, and complete a substantial original story in the genre of your choosing. The price: Free with 7-day Coursera trial; $49 per month to keep learning after trial ends.

- Main content

- Writing, Research & Publishing Guides

Enjoy fast, free delivery, exclusive deals, and award-winning movies & TV shows with Prime Try Prime and start saving today with fast, free delivery

Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Return this item for free

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Follow the author

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Teaching Creative Writing: The Essential Guide

Purchase options and add-ons.

- ISBN-10 1350276480

- ISBN-13 978-1350276482

- Publisher Bloomsbury Academic

- Publication date February 8, 2024

- Language English

- Dimensions 5.5 x 0.64 x 8.5 inches

- Print length 198 pages

- See all details

Customers who viewed this item also viewed

Editorial Reviews

About the author, product details.

- Publisher : Bloomsbury Academic (February 8, 2024)

- Language : English

- Hardcover : 198 pages

- ISBN-10 : 1350276480

- ISBN-13 : 978-1350276482

- Item Weight : 13.4 ounces

- Dimensions : 5.5 x 0.64 x 8.5 inches

About the author

Stephanie vanderslice.

Stephanie Vanderslice's was born in Queens, NY in 1967 and grew up there and in the suburbs of Albany. Her essays have appeared in Mothers in All But Name, Knowing Pains: Women on Love, Sex and Work in their 40's and many others. In addition to The Geek's Guide to the Writing Life, she has also published Can Creative Writing Really Be Taught? 10th Anniversary edition (co-edited with Rebecca Manery) with Bloomsbury. Other books include Rethinking Creative Writing and Teaching Creative Writing to Undergraduates (with Kelly Ritter). Professor of Creative Writing and Director of the Arkansas Writer's MFA Workshop at the University of Central Arkansas, she also writes novels and has published creative nonfiction, fiction, and creative criticism in such venues as Ploughshares Online, Easy Street and others. Her column, The Geek's Guide to the Writing Life appears regularly in the Huffington Post.

Recommended reads include Simon Van Booy's Father's Day, Nicole Krauss's Great House, Jhumpa Lahiri's Unaccustomed Earth, and Jesse Lee Kercheval's The Museum of Happiness (all time favorite). Stephanie lives in Conway, Arkansas with her husband, writer John Vanderslice (no, not the indie songster) and two sons. She can also make a mean loaf of french bread.

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

No customer reviews

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business