- Home »

find your perfect postgrad program Search our Database of 30,000 Courses

Writing a dissertation proposal.

What is a dissertation proposal?

Dissertation proposals are like the table of contents for your research project , and will help you explain what it is you intend to examine, and roughly, how you intend to go about collecting and analysing your data. You won’t be required to have everything planned out exactly, as your topic may change slightly in the course of your research, but for the most part, writing your proposal should help you better identify the direction for your dissertation.

When you’ve chosen a topic for your dissertation , you’ll need to make sure that it is both appropriate to your field of study and narrow enough to be completed by the end of your course. Your dissertation proposal will help you define and determine both of these things and will also allow your department and instructors to make sure that you are being advised by the best person to help you complete your research.

A dissertation proposal should include:

- An introduction to your dissertation topic

- Aims and objectives of your dissertation

- A literature review of the current research undertaken in your field

- Proposed methodology to be used

- Implications of your research

- Limitations of your research

- Bibliography

Although this content all needs to be included in your dissertation proposal, the content isn’t set in stone so it can be changed later if necessary, depending on your topic of study, university or degree. Think of your dissertation proposal as more of a guide to writing your dissertation rather than something to be strictly adhered to – this will be discussed later.

Why is a dissertation proposal important?

A dissertation proposal is very important because it helps shape the actual dissertation, which is arguably the most important piece of writing a postgraduate student will undertake. By having a well-structured dissertation proposal, you will have a strong foundation for your dissertation and a good template to follow. The dissertation itself is key to postgraduate success as it will contribute to your overall grade . Writing your dissertation will also help you to develop research and communication skills, which could become invaluable in your employment success and future career. By making sure you’re fully briefed on the current research available in your chosen dissertation topic, as well as keeping details of your bibliography up to date, you will be in a great position to write an excellent dissertation.

Next, we’ll be outlining things you can do to help you produce the best postgraduate dissertation proposal possible.

How to begin your dissertation proposal

1. Narrow the topic down

It’s important that when you sit down to draft your proposal, you’ve carefully thought out your topic and are able to narrow it down enough to present a clear and succinct understanding of what you aim to do and hope to accomplish in your dissertation.

How do I decide on a dissertation topic?

A simple way to begin choosing a topic for your dissertation is to go back through your assignments and lectures. Was there a topic that stood out to you? Was there an idea that wasn’t fully explored? If the answer to either of these questions is yes, then you have a great starting point! If not, then consider one of your more personal interests. Use Google Scholar to explore studies and journals on your topic to find any areas that could go into more detail or explore a more niche topic within your personal interest.

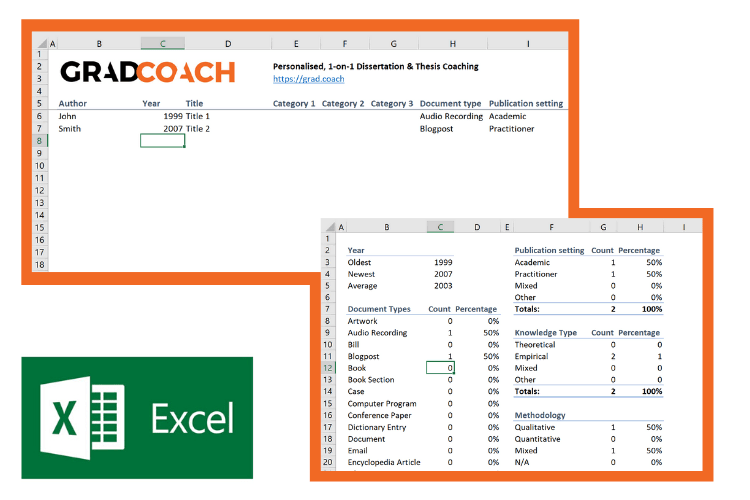

Keep track of all publications

It’s important to keep track of all the publications that you use while you research. You can use this in your literature review.

You need to keep track of:

- The title of the study/research paper/book/journal

- Who wrote/took part in the study/research paper

- Chapter title

- Page number(s)

The more research you do, the more you should be able to narrow down your topic and find an interesting area to focus on. You’ll also be able to write about everything you find in your literature review which will make your proposal stronger.

While doing your research, consider the following:

- When was your source published? Is the information outdated? Has new information come to light since?

- Can you determine if any of the methodologies could have been carried out more efficiently? Are there any errors or gaps?

- Are there any ethical concerns that should be considered in future studies on the same topic?

- Could anything external (for example new events happening) have influenced the research?

Read more about picking a topic for your dissertation .

How long should the dissertation proposal be?

There is usually no set length for a dissertation proposal, but you should aim for 1,000 words or more. Your dissertation proposal will give an outline of the topic of your dissertation, some of the questions you hope to answer with your research, what sort of studies and type of data you aim to employ in your research, and the sort of analysis you will carry out.

Different courses may have different requirements for things like length and the specific information to include, as well as what structure is preferred, so be sure to check what special requirements your course has.

2. What should I include in a dissertation proposal?

Your dissertation proposal should have several key aspects regardless of the structure. The introduction, the methodology, aims and objectives, the literature review, and the constraints of your research all need to be included to ensure that you provide your supervisor with a comprehensive proposal. But what are they? Here's a checklist to get you started.

- Introduction

The introduction will state your central research question and give background on the subject, as well as relating it contextually to any broader issues surrounding it.

The dissertation proposal introduction should outline exactly what you intend to investigate in your final research project.

Make sure you outline the structure of the dissertation proposal in your introduction, i.e. part one covers methodology, part two covers a literature review, part three covers research limitations, and so forth.

Your introduction should also include the working title for your dissertation – although don't worry if you want to change this at a later stage as your supervisors will not expect this to be set in stone.

Dissertation methodology

The dissertation methodology will break down what sources you aim to use for your research and what sort of data you will collect from it, either quantitative or qualitative. You may also want to include how you will analyse the data you gather and what, if any, bias there may be in your chosen methods.

Depending on the level of detail that your specific course requires, you may also want to explain why your chosen approaches to gathering data are more appropriate to your research than others.

Consider and explain how you will conduct empirical research. For example, will you use interviews? Surveys? Observation? Lab experiments?

In your dissertation methodology, outline the variables that you will measure in your research and how you will select your data or participant sample to ensure valid results.

Finally, are there any specific tools that you will use for your methodology? If so, make sure you provide this information in the methodology section of your dissertation proposal.

- Aims and objectives

Your aim should not be too broad but should equally not be too specific.

An example of a dissertation aim could be: ‘To examine the key content features and social contexts that construct successful viral marketing content distribution on X’.

In comparison, an example of a dissertation aim that is perhaps too broad would be: ‘To investigate how things go viral on X’.

The aim of your dissertation proposal should relate directly to your research question.

- Literature review

The literature review will list the books and materials that you will be using to do your research. This is where you can list materials that gave you more background on your topic, or contain research carried out previously that you referred to in your own studies.

The literature review is also a good place to demonstrate how your research connects to previous academic studies and how your methods may differ from or build upon those used by other researchers. While it’s important to give enough information about the materials to show that you have read and understood them, don’t forget to include your analysis of their value to your work.

Where there are shortfalls in other pieces of academic work, identify these and address how you will overcome these shortcomings in your own research.

Constraints and limitations of your research

Lastly, you will also need to include the constraints of your research. Many topics will have broad links to numerous larger and more complex issues, so by clearly stating the constraints of your research, you are displaying your understanding and acknowledgment of these larger issues, and the role they play by focusing your research on just one section or part of the subject.

In this section it is important to Include examples of possible limitations, for example, issues with sample size, participant drop out, lack of existing research on the topic, time constraints, and other factors that may affect your study.

- Ethical considerations

Confidentiality and ethical concerns are an important part of any research.

Ethics are key, as your dissertation will need to undergo ethical approval if you are working with participants. This means that it’s important to allow for and explain ethical considerations in your dissertation proposal.

Keep confidentiality in mind and keep your participants informed, so they are aware of how the data provided is being used and are assured that all personal information is being kept confidential.

Consider how involved your patients will be with your research, this will help you think about what ethical considerations to take and discuss them fully in your dissertation proposal. For example, face-to-face participant interview methods could require more ethical measures and confidentiality considerations than methods that do not require participants, such as corpus data (a collection of existing written texts) analysis.

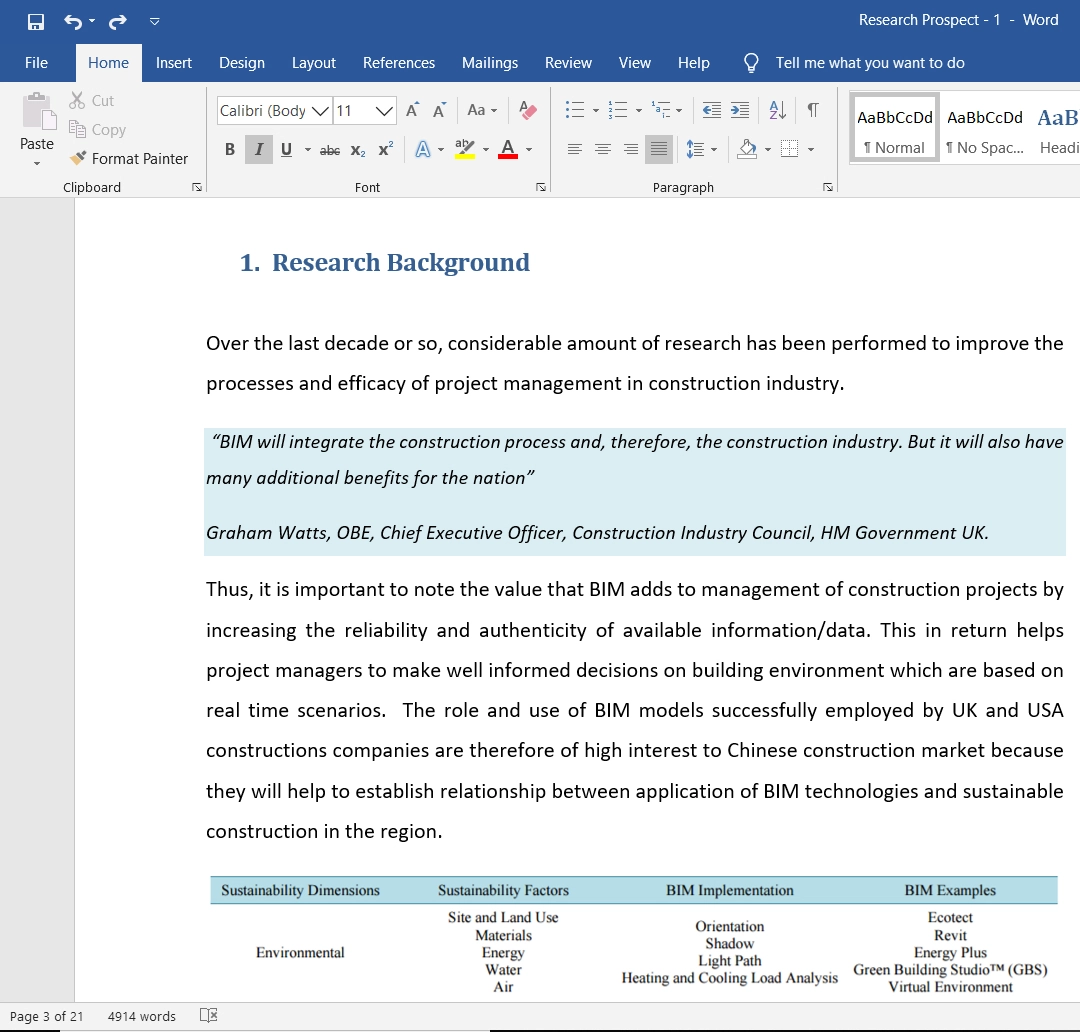

3. Dissertation proposal example

Once you know what sections you need or do not need to include, it may help focus your writing to break the proposal up into separate headings, and tackle each piece individually. You may also want to consider including a title. Writing a title for your proposal will help you make sure that your topic is narrow enough, as well as help keep your writing focused and on topic.

One example of a dissertation proposal structure is using the following headings, either broken up into sections or chapters depending on the required word count:

- Methodology

- Research constraints

In any dissertation proposal example, you’ll want to make it clear why you’re doing the research and what positives could come from your contribution.

Dissertation proposal example table

This table outlines the various stages of your dissertation proposal.

Apply for one of our x5 bursaries worth £2,000

We've launched our new Postgrad Solutions Study Bursaries for 2024. Full-time, part-time, online and blended-learning students eligible. 2024 & 2025 January start dates students welcome. Study postgraduate courses in any subject taught anywhere worldwide.

Related articles

What Is The Difference Between A Dissertation & A Thesis

Dissertation Methodology

Top Tips When Writing Your Dissertation

How To Survive Your Masters Dissertation

Everything You Need To Know About Your Research Project

Postgrad Solutions Study Bursaries

Exclusive bursaries Open day alerts Funding advice Application tips Latest PG news

Sign up now!

Take 2 minutes to sign up to PGS student services and reap the benefits…

- The chance to apply for one of our 5 PGS Bursaries worth £2,000 each

- Fantastic scholarship updates

- Latest PG news sent directly to you.

- How it works

How to Write a Dissertation Proposal with Structure & Steps

Published by Anastasia Lois at August 14th, 2021 , Revised On October 26, 2023

“A dissertation proposal is a stepping stone towards writing the final dissertation paper. It’s a unique document that informs the reader of the aim & objectives of dissertation research and its course of action.”

The main purpose of a proposal paper is to showcase to your supervisor or dissertation committee members that your dissertation research will add value to existing knowledge in your area of study.

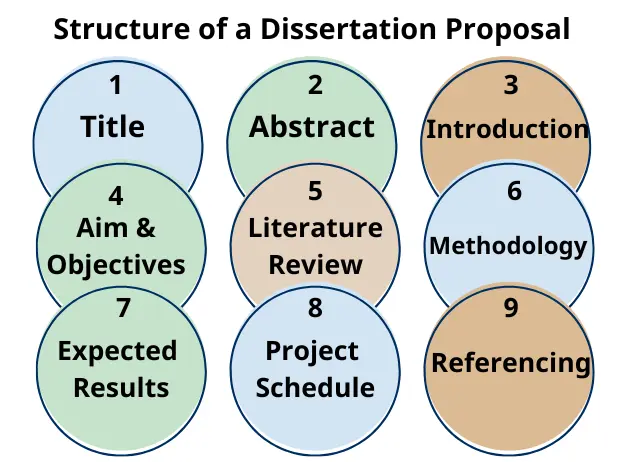

Although the exact structure of a dissertation proposal may vary depending on your academic level, academic subject, and size of the paper, the contents remain pretty much the same.

However, it will still make sense to consult with your supervisor about the proposal formatting and structuring guidelines before working on your dissertation proposal paper.

You may lose out on scoring some important marks if your proposal paper does not follow your department’s specific rules. Here are some tips for you on how to structure a dissertation proposal paper.

Tips on Completing a Dissertation Proposal in Due Time

Consult your supervisor or department to find out how much time you have to complete your dissertation proposal . Each graduate program is different, so you must adhere to the specific rules to avoid unwelcome surprises.

Depending on the degree program you are enrolled in, you may have to start working on your chosen topic right away, or you might need to deal with some assignments and exams first.

You can learn about the rules and timelines concerning your dissertation project on the university’s online portal. If you are still unsure, it will be best to speak with your department’s admin clerk, the program head, or supervisor.

Look for Proposal Structural Requirements in the Guidelines

Most academic institutions will provide precise rules for structuring your dissertation proposal in terms of the document’s content and how to arrange it. If you have not figured out these requirements, you must speak with your supervisor to find out what they recommend. Typical contents and structure of a dissertation proposal include the following;

- Statement of the Problem

- Background/Rationale

- Introduction (Justifying your Research)

- Research Questions or Hypothesis (Research aim and objectives)

- Literature Review

- Proposed Methodology

- Opportunities and Limitations

Project Schedule

Have an unhelpful dissertation project supervisor? Here is some advice to help you deal with an uncompromising dissertation advisor.

How Long is a Dissertation Proposal?

The length of your dissertation proposal will depend on your degree program and your research topic. PhD-level dissertation proposals are much longer in terms of word count than Bachelors’s and Master’s level proposals.

- Bachelor’s level dissertation proposals are about 5-6 pages long.

- Masters and Ph.D. level proposals’ length varies from 15-25 pages depending on the academic subject and degree program’s specifications.

- If the word count or page length expectation is not mentioned in the dissertation handbook or the guidelines on the university’s website, you should check with your supervisor or program coordinator for a clear understanding of this particular requirement.

The proposals we write have:

- Precision and Clarity

- Zero Plagiarism

- High-level Encryption

- Authentic Sources

Dissertation Proposal Formatting

Formatting your dissertation proposal will also depend on your program’s specific guidelines and your research area. Find the exact guidelines for formatting cover sheets and title pages, referencing style, notes, bibliography, margin sizes, page numbers, and fonts. Again if you are unsure about anything, it is recommended to consult with your project advisor.

Find out About the Approval Criteria

The process of writing your dissertation proposal paper and getting acceptance from the committee of members of your supervisor is tricky.

Consult your department’s academic assistant, supervisor, or program chair to learn about all the process stages. Here are a couple of points you will need to be aware of:

- You might be required to have your chosen research topic approved by your academic supervisor or department chair.

- Submit your proposal and have it formally signed and approved so you can continue with your research.

You may find the dissertation proposal writing process perplexing and challenging if this is the first time you are preparing such a document. All the essential elements of a dissertation proposal paper need to be present before submitting it for approval.

Any feedback received from the tutor or the supervising committee should be taken very seriously and incorporated into your planning for dissertation research. Do not start working on your final dissertation paper until your supervisor has accepted the proposal.

To help you organise your dissertation proposal paper correctly, we have detailed guidelines for structuring a dissertation proposal. Irrespective of the degree program you are developing your dissertation proposal for, you will find these guidelines equally important.

Our expert academics can produce a flawless dissertation proposal on your chosen topic. They can also suggest free topics in your area of study if you haven’t selected a topic. Order free topics here or get a quote for our proposal writing service here.

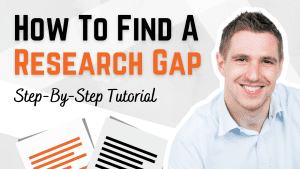

Select a Topic

Selecting an appropriate topic is the key to having your research work recognised in your field of study. Make sure your chosen topic is relevant, interesting, and manageable.

Ideally, you would want to research a topic that previous researchers have not explored so you can contribute to knowledge on the academic subject.

But even if your topic has been well-researched previously, you can make your study stand out by tweaking the research design and research questions to add a new dimension to your research.

How to Choose a Suitable Research Topic

Here are some guidelines on how to choose a suitable research topic.

List all the topics that you find interesting and relevant to your area of study. PhD and MaMasters’sevel students are already well aware of their academic interests.

Bachelor students can consider unanswered questions that emerged from their past academic assignments and drove them to conduct a detailed investigation to find answers.

Follow this process, and you’ll be able to choose the most appropriate topic for your research. Not only will this make your dissertation unique, but it also increases the chances of your proposal being accepted in the first attempt.

- Think about all your past academic achievements and associations, such as any research notes you might have written for your classes, any unsettled questions from your previous academic assignments that left you wondering, and the material you learned in classes taught by professors.

- For example , you learned about how natural gas is supplied to households in the UK in one of your coursework assignments and now eagerly wish to know exactly how natural gas is processed at an industrial scale.

ORDER YOUR PROPOSAL NOW

Conduct initial research on your chosen topic(s). This will include reading authentic text material on the topic(s) to familiarise yourself with each potential topic. Doing so will help you figure out whether there really is a need to investigate your selected topics further.

Visit your university’s library or online academic databases such as ProQuest, EBSCO, QuickBase to find articles, journals, books, peer-reviewed articles, and thesis/dissertation papers (by other students) written on your possible research topic .

Ignore all academic sources that you find methodologically flawed or obsolete. Visit our online research topics library to choose a topic relevant to your interests .

Consult your academic supervisor and show them your list of potential topics. Their advice will be crucial for deciding whether the topic you are interested in is appropriate and meets your degree program requirements.

It is recommended to set up an appointment with your supervisor to see them in person to discuss your potential topics, even though you can do the same in email too.

- If the topics you are interested in are too broad or lack focus, your supervisor will be able to guide you towards academic sources that could help narrow down your research.

- Having several topics in your list of potential topics will mean that you will have something to fall back onto if they don’t approve your first choice.

Narrow the Focus of your Research – Once a topic has been mutually agreed upon between you and your academic supervisor, it is time to narrow down the focus. Hence, your research explores an aspect of the topic that has not been investigated before.

Spend as much time as possible examining different aspects of the topic to establish a research aim that would truly add value to the existing knowledge.

- For example, you were initially interested in studying the different natural gas process techniques in the UK on an industrial scale. But you noticed that the existing literature doesn’t count for one advanced gas processing method that helps the industry save millions of pounds every year. Hence, you decide to make that the focus of your research.

- Your topic could be too broad as you start your research, but as you dig deep into your research, the topic will continue to narrow and evolve. TIP – It is better to work on a topic that is too broad rather than on something there is not enough text material to work with.

Structure of a Dissertation Proposal

The key elements of a great dissertation proposal are explained in detail under this section ‘structure of a dissertation proposal’. Once you’ve finalised your topic, you need to switch to writing your dissertation proposal paper quickly. As previously mentioned, your proposal paper’s exact structure may vary depending on your university/college requirements.

A good dissertation proposal title will give the reader an insight into the aim/idea of your study. Describe the purpose and/or contents of your dissertation proposal paper in the fewest possible words.

A concise and focused title will help you gain the attention of the readers. However, you might need to adjust your title several times as you write the paper because your comprehensive research might continue to add new dimensions to your study.

- Your title must be as categorical as possible. For example, instead of “Natural Gas Processing Techniques in the UK”, use a more specific title like “Investigating various industrial natural gas processing technologies employed in the UK” so the reader can understand exactly what your research is about.

Write a brief executive summary or an abstract of your proposal if you have been asked to do so in the structural guidelines. Generally, the abstract is included in the final dissertation paper with a length of around 300-400 words.

If you have to write an abstract for your proposal, here are the key points that it must cover;

- The background to your research.

- Research questions that you wish to address.

- Your proposed methods of research, which will either test the hypothesis or address the research problem.

- The significance of your research as to how it will add value to the scientific or academic community.

Get Help With Your Assignment!

Uk’s best academic support services. how would you know until you try.

Introduction

This is your first chance to make a strong impression on the reader. Not only your introduction section should be engaging, contextually, but it is also supposed to provide a background to the topic and explain the thesis problem .

Here is what the first paragraph of the introduction section should include:

- Explain your research idea and present a clear understanding as to why you’ve chosen this topic.

- Present a summary of the scope of your research study, taking into account the existing literature.

- Briefly describe the issues and specific problems your research aims to address!

In the next paragraphs, summarise the statement of the problem . Explain what gap in the existing knowledge your research will fill and how your work will prove significant in your area of study.

For example, the focus of your research could be the stage of carbon monoxide removal from natural gas. Still, other similar studies do not sufficiently explore this aspect of natural gas processing technology.

Here is a comprehensive article on “ How to Write Introduction for Dissertation Paper .”

Aim & Objectives

This is the most critical section of the proposal paper . List the research questions or the research objectives your study will address. When writing this particular section, it will make sense to think of the following questions:

- Are there any specific findings that you are expecting?

- What aspects of the topic have you decided not to investigate and why?

- How will your research contribute to the existing knowledge in your field?

Literature Review

The literature review section is your chance to state the key established research trends, hypotheses , and theories on the subject. Demonstrate to the reader that your research is a unique contribution to your field because it explores the topic from a new angle.

In a dissertation proposal, you won’t be expected to provide an extensive list of all previous research studies on the topic. Still, all the key theories reported by other scholars should be briefly referred to.

Take into consideration the following when writing the literature review section:

- The gaps identified in the previous research studies on the topic which your own research aims to fill. State the limitations of previous studies, whether lacking sufficient evidence, invalid, or too broad.

- The key established research trends, theories, and hypotheses as reported by other researchers.

- Any specific arguments and/or methodologies that previous scholars used when investigating your topic.

Our expert dissertation proposal editors can improve the quality of your proposal paper to the First Class standard. Complete this short and simple order form here so we can get feedback from our writers.

Methodology

A focused and well-defined methodology in a proposal paper can help you explain to your readers how you plan to conduct your research and why your chosen research design can provide reliable answers to your research questions.

The choice of research design and analytical approach will depend on several factors, including but not limited to your area of study and research constraints.

Depending on your topic and the existing literature, you will need to decide whether your dissertation will be purely descriptive or use primary (quantitative/qualitative data) as part of the research design.

Any research limitations and ethical issues that you expect to deal with should be clearly stated. For example, you might not be able to use a large sample size of respondents due to financial constraints. Small sample size can undermine your research significance.

How to Write a First Class Dissertation Proposal or Research Proposal.

“If you’re unable to pull off a first-class proposal, we’re here to help. We at ResearchProspect make sure that our writers prepare a flawless dissertation proposal for you. Our highly qualified team of writers will also help you choose a relevant topic for your subject area. Get in touch with us today, and let us take care of all your dissertation worries! Learn more about our dissertation proposal writing service.

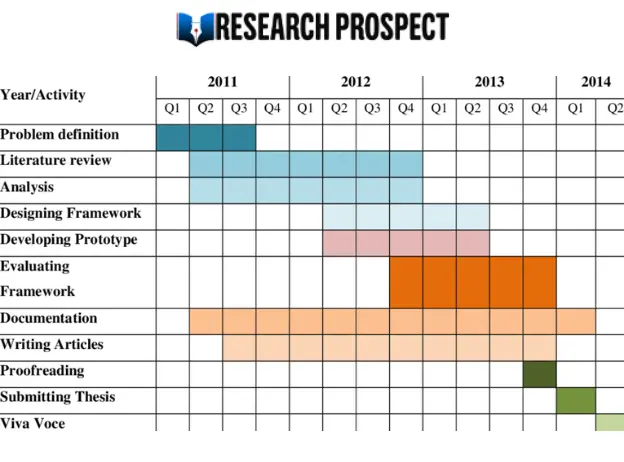

Some Masters and PhD level degree programs require students to include a project timeline or timetable to give readers an idea of how and when they plan to complete different stages of the project.

Project timeline can be a great planning tool, mainly if your research includes experiments, statistical analysis , designing, and primary data collection. However, it may have to be modified slightly as you progress into your research.

By no means is it a fixed program for carrying out your work. When developing the project timeline in your proposal, always consider the time needed for practical aspects of the research, such as travelling, experiments, and fieldwork.

Referencing and In-Text Citations

Underrated, but referencing is one of the most crucial aspects of preparing a proposal. You can think of your proposal as the first impression of your dissertation.

You would want everything to be perfect and in place, wouldn’t you? Thus, always make sure that your dissertation consists of all the necessary elements.

You will have to cite information and data that you include in your dissertation. So make sure that the references that you include are credible and authentic.

You can use well-known academic journals, official websites, past researches, and concepts presented by renowned authors and writers in the respective field.

The same rule applies to in-text citations. Make sure that you cite references accurately according to the required referencing style as mentioned in the guidelines.

References should back statistics, facts, and figures at all times. It is highly recommended to back every 100-200 words written with at least one academic reference. The quantity of references does not matter; however, the quality does.

These are the basic elements of a dissertation proposal. Taking care of all these sections will help you when you are confused about structuring a dissertation proposal. In addition to these steps, look for different dissertation proposal examples on your research topic. A sample dissertation proposal paper can provide a clear understanding of how to go about the “pro”osal stage” of”the dissertation project.

“If you’re unable to pull off a first-class proposal, we’re here to help. We at ResearchProspect make sure that our writers prepare a flawless dissertation proposal for you. Our highly qualified team of writers will also help you choose a relevant topic for your subject area. Get in touch with us today, and let us take care of all your dissertation worries! Learn more about our dissertation proposal writing service .”

Frequently Asked Questions

What is dissertation proposal in research.

A dissertation proposal in research outlines the planned study. It includes research objectives, methods, scope, and significance. It’s a blueprint that demonstrates the feasibility and value of the research, helping gain approval before proceeding with the full dissertation.

How do you write a dissertation proposal?

A dissertation proposal outlines your research topic, objectives, methodology, and potential significance. Start with a clear title, state your research question, detail the methods you will use to answer it, and highlight the contribution it will make to the field. Ensure it is well-researched, concise, and compelling to gain approval.

How long is a dissertation proposal?

A dissertation proposal’s length varies by field and institution. Typically, it ranges from 10 to 20 pages, but can be longer for complex topics. It includes an introduction, research question, literature review, methodology, and potential significance. Always consult department guidelines or advisors to ensure appropriate length and content.

What are the types of dissertation proposals?

Dissertation proposal types largely depend on the research’s nature and methodology. Common types include empirical (collecting data from the real world), non-empirical (theory or literature-based), and narrative (case studies). Each type dictates a different approach to data collection, analysis, and presentation, tailored to the subject and field of study.

You May Also Like

Make sure that your selected topic is intriguing, manageable, and relevant. Here are some guidelines to help understand how to find a good dissertation topic.

How to write a hypothesis for dissertation,? A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested with the help of experimental or theoretical research.

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

University Libraries

Writing a dissertation or thesis proposal, what is a proposal, what is the purpose of a proposal.

- Video Tutorials

- Select a Topic

- Research Questions

- Search the Literature

- Plan Before Reviewing

- Review the Literature

- Write the Review

- IRB Approval

The proposal, sometimes called the prospectus, is composed mainly of the Introduction, Research Questions, Literature Review, Research Significance and Methodology. It may also include a dissertation/thesis outline and a timeline for your proposed research. You will be able to reuse the proposal when you actually write the entire dissertation or thesis.

In the graduate student timeline, the proposal comes after successfully passing qualifying or comprehensive exams and before starting the research for a dissertation or thesis.

Each UNT department has slightly different proposal requirements, so be sure to check with your advisor or the department's graduate advisor before you start!

- Examples of Proposals from UTexas More than 20 completed dissertation proposals are available to read at the UT Intellectual Entrepreneurship website.

- Dissertation Proposal Guidelines This document from the Department of Communication at the University of Washington is a good example of what you might be expected to include in a proposal.

The purpose of a proposal is to convince your dissertation or thesis committee that you are ready to start your research project and to create a plan for your dissertation or thesis work. You will submit your proposal to your committee for review and then you will do your proposal defense, during which you present your plan and the committee asks questions about it. The committee wants to know if your research questions have academic merit and whether you have chosen the right methods to answer the questions.

- How to Prepare a Successful Dissertation Proposal Defense Some general tips for a proposal defense from synonym.com

Need help? Then use the library's Ask Us service. Get help from real people face-to-face, by phone, or by email.

- Next: Resources >>

- Last Updated: Nov 13, 2023 4:28 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.unt.edu/Dissertation-thesis-proposal

Additional Links

UNT: Apply now UNT: Schedule a tour UNT: Get more info about the University of North Texas

UNT: Disclaimer | UNT: AA/EOE/ADA | UNT: Privacy | UNT: Electronic Accessibility | UNT: Required Links | UNT: UNT Home

- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty/Staff

- Current Students Hub

Doctoral handbook

You are here

- Dissertation Proposal

On this page:

Proposal Overview and Format

Proposal committee, proposal hearing or meeting.

- Printing Credit for Use in School of Education Labs

Students are urged to begin thinking about a dissertation topic early in their degree program. Concentrated work on a dissertation proposal normally begins after successful completion of the Second-Year Review, which often includes a “mini” proposal, an extended literature review, or a theoretical essay, plus advancement to doctoral candidacy. In defining a dissertation topic, the student collaborates with their faculty advisor or dissertation advisor (if one is selected) in the choice of a topic for the dissertation.

The dissertation proposal is a comprehensive statement on the extent and nature of the student’s dissertation research interests. Students submit a draft of the proposal to their dissertation advisor between the end of the seventh and middle of the ninth quarters. The student must provide a written copy of the proposal to the faculty committee no later than two weeks prior to the date of the proposal hearing. Committee members could require an earlier deadline (e.g., four weeks before the hearing).

The major components of the proposal are as follows, with some variations across Areas and disciplines:

- A detailed statement of the problem that is to be studied and the context within which it is to be seen. This should include a justification of the importance of the problem on both theoretical and educational grounds.

- A thorough review of the literature pertinent to the research problem. This review should provide proof that the relevant literature in the field has been thoroughly researched. Good research is cumulative; it builds on the thoughts, findings, and mistakes of others.

- its general explanatory interest

- the overall theoretical framework within which this interest is to be pursued

- the model or hypotheses to be tested or the research questions to be answered

- a discussion of the conceptual and operational properties of the variables

- an overview of strategies for collecting appropriate evidence (sampling, instrumentation, data collection, data reduction, data analysis)

- a discussion of how the evidence is to be interpreted (This aspect of the proposal will be somewhat different in fields such as history and philosophy of education.)

- If applicable, students should complete a request for approval of research with human subjects, using the Human Subjects Review Form ( http://humansubjects.stanford.edu/ ). Except for pilot work, the University requires the approval of the Administrative Panel on Human Subjects in Behavioral Science Research before any data can be collected from human subjects.

Registration (i.e., enrollment) is required for any quarter during which a degree requirement is completed, including the dissertation proposal. Refer to the Registration or Enrollment for Milestone Completion section for more details.

As students progress through the program, their interests may change. There is no commitment on the part of the student’s advisor to automatically serve as the dissertation chair. Based on the student’s interests and the dissertation topic, many students approach other GSE professors to serve as the dissertation advisor, if appropriate.

A dissertation proposal committee is comprised of three academic council faculty members, one of whom will serve as the major dissertation advisor. Whether or not the student’s general program advisor serves on the dissertation proposal committee and later the reading committee will depend on the relevance of that faculty member’s expertise to the topic of the dissertation, and their availability. There is no requirement that a program advisor serve, although very often they do. Members of the dissertation proposal committee may be drawn from other area committees within the GSE, from other departments in the University, or from emeriti faculty. At least one person serving on the proposal committee must be from the student’s area committee (CTE, DAPS, SHIPS). All three members must be on the Academic Council; if the student desires the expertise of a non-Academic Council member, it may be possible to petition. After the hearing, a memorandum listing the changes to be made will be written and submitted with the signed proposal cover sheet and a copy of the proposal itself to the Doctoral Programs Officer.

Review and approval of the dissertation proposal occurs normally during the third year. The proposal hearing seeks to review the quality and feasibility of the proposal. The Second-Year Review and the Proposal Hearing are separate milestones and may not occur as part of the same hearing or meeting.

The student and the dissertation advisor are responsible for scheduling a formal meeting or hearing to review the proposal; the student and proposal committee convene for this evaluative period. Normally, all must be present at the meeting either in person or via conference phone call.

At the end of this meeting, the dissertation proposal committee members should sign the Cover Sheet for Dissertation Proposal and indicate their approval or rejection of the proposal. This signed form should be submitted to the Doctoral Programs Officer. If the student is required to make revisions, an addendum is required with the written approval of each member of the committee stating that the proposal has been revised to their satisfaction.

After submitting the Proposal Hearing material to the Doctoral Programs Officer, the student should make arrangements with three faculty members to serve on their Dissertation Reading Committee. The Doctoral Dissertation Reading Committee form should be completed and given to the Doctoral Programs Officer to enter in the University student records system. Note: The proposal hearing committee and the reading committee do not have to be the same three faculty members. Normally, the proposal hearing precedes the designation of a Dissertation Reading Committee, and faculty on either committee may differ (except for the primary dissertation advisor). However, some students may advance to Terminal Graduate Registration (TGR) status before completing their dissertation proposal hearing if they have established a dissertation reading committee. In these cases, it is acceptable for the student to form a reading committee prior to the dissertation proposal hearing. The reading committee then serves as the proposal committee.

The proposal and reading committee forms and related instructions are on the GSE website, under current students>forms.

Printing Credit for Use in GSE Labs

Upon completion of their doctoral dissertation proposal, GSE students are eligible for a $300 printing credit redeemable in any of the GSE computer labs where students are normally charged for print jobs. Only one $300 credit per student will be issued, but it is usable throughout the remainder of her or his doctoral program until the balance is exhausted. The print credit can be used only at the printers in Cubberley basement and CERAS, and cannot be used toward copying.

After submitting the signed dissertation proposal cover sheet to the Doctoral Programs Officer indicating approval (see above), students can submit a HELP SU ticket online at helpsu.stanford.edu to request the credit. When submitting the help ticket, the following should be selected from the drop-down menus for HELP SU:

Request Category : Computer, Handhelds (PDAs), Printers, Servers Request Type : Printer Operating System : (whatever system is used by the student, e.g., Windows XP.)

The help ticket will be routed to the GSE's IT Group for processing; they will in turn notify the student via email when the credit is available.

- Printer-friendly version

Handbook Contents

- Timetable for the Doctoral Degree

- Degree Requirements

- Registration or Enrollment for Milestone Completion

- The Graduate Study Program

- Student Virtual and Teleconference Participation in Hearings

- First Year (3rd Quarter) Review

- Second Year (6th Quarter) Review

- Committee Composition for First- and Second-Year Reviews

- Advancement to Candidacy

- Academic Program Revision

- Dissertation Content

- Dissertation Reading Committee

- University Oral Examination

- Submitting the Dissertation

- Registration and Student Statuses

- Graduate Financial Support

- GSE Courses

- Curriculum Studies and Teacher Education (CTE)

- Developmental and Psychological Sciences (DAPS)

- Learning Sciences and Technology Design (LSTD)

- Race, Inequality, and Language in Education (RILE)

- Social Sciences, Humanities, and Interdisciplinary Policy Studies in Education (SHIPS)

- Contact Information

- Stanford University Honor Code

- Stanford University Fundamental Standard

- Doctoral Programs Degree Progress Checklist

- GSE Open Access Policies

PhD students, please contact

MA POLS and MA/PP students, please contact

EDS, ICE/IEPA, Individually Designed, LDT, MA/JD, MA/MBA students, please contact

Stanford Graduate School of Education

482 Galvez Mall Stanford, CA 94305-3096 Tel: (650) 723-2109

- Contact Admissions

- GSE Leadership

- Site Feedback

- Web Accessibility

- Career Resources

- Faculty Open Positions

- Explore Courses

- Academic Calendar

- Office of the Registrar

- Cubberley Library

- StanfordWho

- StanfordYou

Improving lives through learning

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

Library Guides

Dissertations 1: getting started: writing a proposal.

- Starting Your Dissertation

- Choosing A Topic and Researching

- Devising An Approach/Method

- Thinking Of A Title

- Writing A Proposal

What is a Proposal?

Before you start your dissertation, you may be asked to write a proposal for it.

The purpose of a dissertation proposal is to provide a snapshot of what your study involves. Usually, after submission of the proposal you will be assigned a supervisor who has some expertise in your field of study. You should receive feedback on the viability of the topic, how to focus the scope, research methods, and other issues you should consider before progressing in your research.

The research proposal should present the dissertation topic, justify your reasons for choosing it and outline how you are going to research it . You'll have to keep it brief, as word counts can vary from anywhere between 800 to 3,000 words at undergraduate, postgraduate and doctoral levels.

It is worth bearing in mind that you are not bound by your proposal. Your project is likely going to evolve and may move in a new direction . Your dissertation supervisor is aware that this may occur as you delve deeper into the literature in your field of study. Nevertheless, always discuss any major developments with your supervisor in the first instance.

Reading for your Proposal

Before writing a proposal, you will need to read. A lot! But that doesn’t mean you must read everything. Be targeted! What do you really need to know?

Instead of reading every page in every book, look for clues in chapter titles and introductions to narrow your focus down. Use abstracts from journal articles to check whether the material is relevant to your study and keep notes of your reading along with clear records of bibliographic information and page numbers for your references.

Ultimately, your objective should be to create a dialogue between the theories and ideas you have read and your own thoughts. What is your personal perspective on the topic? What evidence is there that supports your point of view? Furthermore, you should ask questions about each text. Is it current or is it outdated? What argument is the author making? Is the author biased?

Approaching your reading in this way ensures that you engage with the literature critically. You will demonstrate that you have done this in your mini literature review (see Proposal Structure box).

If you have not yet started reading for your proposal, the Literature Review Guide offers advice on choosing a topic and how to conduct a literature search. Additionally, the Effective Reading Guide provides tips on researching and critical reading.

Proposal Structure

So, how is a dissertation proposal typically structured? The structure of a proposal varies considerably.

This is a list of elements that might be required. Please check the dissertation proposal requirements and marking criteria on Blackboard or with your lecturers if you are unsure about the requirements.

Title : The title you have devised, so far - it can change throughout the dissertation drafting process! A good title is simple but fairly specific. Example: "Focus and concentration during revision: an evaluation of the Pomodoro technique."

Introduction/Background : Provides background and presents the key issues of your proposed research. Can include the following:

Rationale : Why is this research being undertaken, why is it interesting and worthwhile, also considering the existing literature?

Purpose : What do you intend to accomplish with your study, e.g. improve something or understand something?

Research question : The main, overarching question your study seeks to answer. E.g. "How can focus and concentration be improved during revision?"

Hypothesis : Quantitative studies can use hypotheses in alternative to research questions. E.g. "Taking regular breaks significantly increases the ability to memorise information."

Aim : The main result your study seeks to achieve. If you use a research question, the aim echoes that, but uses an infinitive. E.g. "The aim of this research is to investigate how can focus and concentration be improved during revision."

Objectives : The stepping stones to achieve your aim. E.g. "The objectives of this research are 1) to review the literature on study techniques; 2) to identify the factors that influence focus and concentration; 3) to undertake an experiment on the Pomodoro technique with student volunteers; 4) to issue recommendations on focus and concentration for revision."

Literature review : Overview of significant literature around the research topic, moving from general (background) to specific (your subject of study). Highlight what the literature says, and does not say, on the research topic, identifying a gap(s) that your research aims to fill.

Methods : Here you consider what methods you are planning to use for your research, and why you are thinking of them. What secondary sources (literature) are you going to consult? Are you going to use primary sources (e.g. data bases, statistics, interviews, questionnaires, experiments)? Are you going to focus on a case study? Is the research going to be qualitative or quantitative? Consider if your research will need ethical clearance.

Significance/Implications/Expected outcomes : In this section you reiterate what are you hoping to demonstrate. State how your research could contribute to debates in your particular subject area, perhaps filling a gap(s) in the existing works.

Plan of Work : You might be asked to present your timeline for completing the dissertation. The timeline can be presented using different formats such as bullet points, table, Gantt chart. Whichever format you use, your plan of work should be realistic and should demonstrate awareness of the various elements of the study such as literature research, empirical work, drafting, re-drafting, etc.

Outline : Here you include a provisional table of contents for your dissertation. The structure of the dissertation can be free or prescribed by the dissertation guidelines of your course, so check that up.

Reference List : The list should include the bibliographical information of all the sources you cited in the proposal, listed in alphabetical order.

Most of the elements mentioned above are explained in the tabs of this guide!

Literature-based dissertations in the humanities

A literature-based dissertation in the humanities, however, might be less rigidly structured and may look like this:

- Short introduction including background information on your topic, why it is relevant and how it fits into the literature.

- Main body which outlines how you will organise your chapters .

- Conclusion which states what you hope your study will achieve.

- Bibliography .

After Writing

Check your proposal!

Have you shown that your research idea is:

Ethical?

Relevant?

Feasible with the timeframe and resources available?

Have you:

Identified a clear research gap to focus on?

Stated why your study is important?

Selected a methodology that will enable you to gather the data you need?

Use the marking criteria for dissertation proposals provided by your department to check your work.

Locke, L.F., Spirduso, W.W. and Silverman, S.J. (2014). Proposals that Work: A Guide for Planning Dissertations and Grant Proposals . Sage.

- << Previous: Planning

- Last Updated: Aug 1, 2023 2:36 PM

- URL: https://libguides.westminster.ac.uk/starting-your-dissertation

CONNECT WITH US

Dissertation Strategies

What this handout is about.

This handout suggests strategies for developing healthy writing habits during your dissertation journey. These habits can help you maintain your writing momentum, overcome anxiety and procrastination, and foster wellbeing during one of the most challenging times in graduate school.

Tackling a giant project

Because dissertations are, of course, big projects, it’s no surprise that planning, writing, and revising one can pose some challenges! It can help to think of your dissertation as an expanded version of a long essay: at the end of the day, it is simply another piece of writing. You’ve written your way this far into your degree, so you’ve got the skills! You’ll develop a great deal of expertise on your topic, but you may still be a novice with this genre and writing at this length. Remember to give yourself some grace throughout the project. As you begin, it’s helpful to consider two overarching strategies throughout the process.

First, take stock of how you learn and your own writing processes. What strategies have worked and have not worked for you? Why? What kind of learner and writer are you? Capitalize on what’s working and experiment with new strategies when something’s not working. Keep in mind that trying out new strategies can take some trial-and-error, and it’s okay if a new strategy that you try doesn’t work for you. Consider why it may not have been the best for you, and use that reflection to consider other strategies that might be helpful to you.

Second, break the project into manageable chunks. At every stage of the process, try to identify specific tasks, set small, feasible goals, and have clear, concrete strategies for achieving each goal. Small victories can help you establish and maintain the momentum you need to keep yourself going.

Below, we discuss some possible strategies to keep you moving forward in the dissertation process.

Pre-dissertation planning strategies

Get familiar with the Graduate School’s Thesis and Dissertation Resources .

Create a template that’s properly formatted. The Grad School offers workshops on formatting in Word for PC and formatting in Word for Mac . There are online templates for LaTeX users, but if you use a template, save your work where you can recover it if the template has corrruption issues.

Learn how to use a citation-manager and a synthesis matrix to keep track of all of your source information.

Skim other dissertations from your department, program, and advisor. Enlist the help of a librarian or ask your advisor for a list of recent graduates whose work you can look up. Seeing what other people have done to earn their PhD can make the project much less abstract and daunting. A concrete sense of expectations will help you envision and plan. When you know what you’ll be doing, try to find a dissertation from your department that is similar enough that you can use it as a reference model when you run into concerns about formatting, structure, level of detail, etc.

Think carefully about your committee . Ideally, you’ll be able to select a group of people who work well with you and with each other. Consult with your advisor about who might be good collaborators for your project and who might not be the best fit. Consider what classes you’ve taken and how you “vibe” with those professors or those you’ve met outside of class. Try to learn what you can about how they’ve worked with other students. Ask about feedback style, turnaround time, level of involvement, etc., and imagine how that would work for you.

Sketch out a sensible drafting order for your project. Be open to writing chapters in “the wrong order” if it makes sense to start somewhere other than the beginning. You could begin with the section that seems easiest for you to write to gain momentum.

Design a productivity alliance with your advisor . Talk with them about potential projects and a reasonable timeline. Discuss how you’ll work together to keep your work moving forward. You might discuss having a standing meeting to discuss ideas or drafts or issues (bi-weekly? monthly?), your advisor’s preferences for drafts (rough? polished?), your preferences for what you’d like feedback on (early or late drafts?), reasonable turnaround time for feedback (a week? two?), and anything else you can think of to enter the collaboration mindfully.

Design a productivity alliance with your colleagues . Dissertation writing can be lonely, but writing with friends, meeting for updates over your beverage of choice, and scheduling non-working social times can help you maintain healthy energy. See our tips on accountability strategies for ideas to support each other.

Productivity strategies

Write when you’re most productive. When do you have the most energy? Focus? Creativity? When are you most able to concentrate, either because of your body rhythms or because there are fewer demands on your time? Once you determine the hours that are most productive for you (you may need to experiment at first), try to schedule those hours for dissertation work. See the collection of time management tools and planning calendars on the Learning Center’s Tips & Tools page to help you think through the possibilities. If at all possible, plan your work schedule, errands and chores so that you reserve your productive hours for the dissertation.

Put your writing time firmly on your calendar . Guard your writing time diligently. You’ll probably be invited to do other things during your productive writing times, but do your absolute best to say no and to offer alternatives. No one would hold it against you if you said no because you’re teaching a class at that time—and you wouldn’t feel guilty about saying no. Cultivating the same hard, guilt-free boundaries around your writing time will allow you preserve the time you need to get this thing done!

Develop habits that foster balance . You’ll have to work very hard to get this dissertation finished, but you can do that without sacrificing your physical, mental, and emotional wellbeing. Think about how you can structure your work hours most efficiently so that you have time for a healthy non-work life. It can be something as small as limiting the time you spend chatting with fellow students to a few minutes instead of treating the office or lab as a space for extensive socializing. Also see above for protecting your time.

Write in spaces where you can be productive. Figure out where you work well and plan to be there during your dissertation work hours. Do you get more done on campus or at home? Do you prefer quiet and solitude, like in a library carrel? Do you prefer the buzz of background noise, like in a coffee shop? Are you aware of the UNC Libraries’ list of places to study ? If you get “stuck,” don’t be afraid to try a change of scenery. The variety may be just enough to get your brain going again.

Work where you feel comfortable . Wherever you work, make sure you have whatever lighting, furniture, and accessories you need to keep your posture and health in good order. The University Health and Safety office offers guidelines for healthy computer work . You’re more likely to spend time working in a space that doesn’t physically hurt you. Also consider how you could make your work space as inviting as possible. Some people find that it helps to have pictures of family and friends on their desk—sort of a silent “cheering section.” Some people work well with neutral colors around them, and others prefer bright colors that perk up the space. Some people like to put inspirational quotations in their workspace or encouraging notes from friends and family. You might try reconfiguring your work space to find a décor that helps you be productive.

Elicit helpful feedback from various people at various stages . You might be tempted to keep your writing to yourself until you think it’s brilliant, but you can lower the stakes tremendously if you make eliciting feedback a regular part of your writing process. Your friends can feel like a safer audience for ideas or drafts in their early stages. Someone outside your department may provide interesting perspectives from their discipline that spark your own thinking. See this handout on getting feedback for productive moments for feedback, the value of different kinds of feedback providers, and strategies for eliciting what’s most helpful to you. Make this a recurring part of your writing process. Schedule it to help you hit deadlines.

Change the writing task . When you don’t feel like writing, you can do something different or you can do something differently. Make a list of all the little things you need to do for a given section of the dissertation, no matter how small. Choose a task based on your energy level. Work on Grad School requirements: reformat margins, work on bibliography, and all that. Work on your acknowledgements. Remember all the people who have helped you and the great ideas they’ve helped you develop. You may feel more like working afterward. Write a part of your dissertation as a letter or email to a good friend who would care. Sometimes setting aside the academic prose and just writing it to a buddy can be liberating and help you get the ideas out there. You can make it sound smart later. Free-write about why you’re stuck, and perhaps even about how sick and tired you are of your dissertation/advisor/committee/etc. Venting can sometimes get you past the emotions of writer’s block and move you toward creative solutions. Open a separate document and write your thoughts on various things you’ve read. These may or may note be coherent, connected ideas, and they may or may not make it into your dissertation. They’re just notes that allow you to think things through and/or note what you want to revisit later, so it’s perfectly fine to have mistakes, weird organization, etc. Just let your mind wander on paper.

Develop habits that foster productivity and may help you develop a productive writing model for post-dissertation writing . Since dissertations are very long projects, cultivating habits that will help support your work is important. You might check out Helen Sword’s work on behavioral, artisanal, social, and emotional habits to help you get a sense of where you are in your current habits. You might try developing “rituals” of work that could help you get more done. Lighting incense, brewing a pot of a particular kind of tea, pulling out a favorite pen, and other ritualistic behaviors can signal your brain that “it is time to get down to business.” You can critically think about your work methods—not only about what you like to do, but also what actually helps you be productive. You may LOVE to listen to your favorite band while you write, for example, but if you wind up playing air guitar half the time instead of writing, it isn’t a habit worth keeping.

The point is, figure out what works for you and try to do it consistently. Your productive habits will reinforce themselves over time. If you find yourself in a situation, however, that doesn’t match your preferences, don’t let it stop you from working on your dissertation. Try to be flexible and open to experimenting. You might find some new favorites!

Motivational strategies

Schedule a regular activity with other people that involves your dissertation. Set up a coworking date with your accountability buddies so you can sit and write together. Organize a chapter swap. Make regular appointments with your advisor. Whatever you do, make sure it’s something that you’ll feel good about showing up for–and will make you feel good about showing up for others.

Try writing in sprints . Many writers have discovered that the “Pomodoro technique” (writing for 25 minutes and taking a 5 minute break) boosts their productivity by helping them set small writing goals, focus intently for short periods, and give their brains frequent rests. See how one dissertation writer describes it in this blog post on the Pomodoro technique .

Quit while you’re ahead . Sometimes it helps to stop for the day when you’re on a roll. If you’ve got a great idea that you’re developing and you know where you want to go next, write “Next, I want to introduce x, y, and z and explain how they’re related—they all have the same characteristics of 1 and 2, and that clinches my theory of Q.” Then save the file and turn off the computer, or put down the notepad. When you come back tomorrow, you will already know what to say next–and all that will be left is to say it. Hopefully, the momentum will carry you forward.

Write your dissertation in single-space . When you need a boost, double space it and be impressed with how many pages you’ve written.

Set feasible goals–and celebrate the achievements! Setting and achieving smaller, more reasonable goals ( SMART goals ) gives you success, and that success can motivate you to focus on the next small step…and the next one.

Give yourself rewards along the way . When you meet a writing goal, reward yourself with something you normally wouldn’t have or do–this can be anything that will make you feel good about your accomplishment.

Make the act of writing be its own reward . For example, if you love a particular coffee drink from your favorite shop, save it as a special drink to enjoy during your writing time.

Try giving yourself “pre-wards” —positive experiences that help you feel refreshed and recharged for the next time you write. You don’t have to “earn” these with prior work, but you do have to commit to doing the work afterward.

Commit to doing something you don’t want to do if you don’t achieve your goal. Some people find themselves motivated to work harder when there’s a negative incentive. What would you most like to avoid? Watching a movie you hate? Donating to a cause you don’t support? Whatever it is, how can you ensure enforcement? Who can help you stay accountable?

Affective strategies

Build your confidence . It is not uncommon to feel “imposter phenomenon” during the course of writing your dissertation. If you start to feel this way, it can help to take a few minutes to remember every success you’ve had along the way. You’ve earned your place, and people have confidence in you for good reasons. It’s also helpful to remember that every one of the brilliant people around you is experiencing the same lack of confidence because you’re all in a new context with new tasks and new expectations. You’re not supposed to have it all figured out. You’re supposed to have uncertainties and questions and things to learn. Remember that they wouldn’t have accepted you to the program if they weren’t confident that you’d succeed. See our self-scripting handout for strategies to turn these affirmations into a self-script that you repeat whenever you’re experiencing doubts or other negative thoughts. You can do it!

Appreciate your successes . Not meeting a goal isn’t a failure–and it certainly doesn’t make you a failure. It’s an opportunity to figure out why you didn’t meet the goal. It might simply be that the goal wasn’t achievable in the first place. See the SMART goal handout and think through what you can adjust. Even if you meant to write 1500 words, focus on the success of writing 250 or 500 words that you didn’t have before.

Remember your “why.” There are a whole host of reasons why someone might decide to pursue a PhD, both personally and professionally. Reflecting on what is motivating to you can rekindle your sense of purpose and direction.

Get outside support . Sometimes it can be really helpful to get an outside perspective on your work and anxieties as a way of grounding yourself. Participating in groups like the Dissertation Support group through CAPS and the Dissertation Boot Camp can help you see that you’re not alone in the challenges. You might also choose to form your own writing support group with colleagues inside or outside your department.

Understand and manage your procrastination . When you’re writing a long dissertation, it can be easy to procrastinate! For instance, you might put off writing because the house “isn’t clean enough” or because you’re not in the right “space” (mentally or physically) to write, so you put off writing until the house is cleaned and everything is in its right place. You may have other ways of procrastinating. It can be helpful to be self-aware of when you’re procrastinating and to consider why you are procrastinating. It may be that you’re anxious about writing the perfect draft, for example, in which case you might consider: how can I focus on writing something that just makes progress as opposed to being “perfect”? There are lots of different ways of managing procrastination; one way is to make a schedule of all the things you already have to do (when you absolutely can’t write) to help you visualize those chunks of time when you can. See this handout on procrastination for more strategies and tools for managing procrastination.

Your topic, your advisor, and your committee: Making them work for you

By the time you’ve reached this stage, you have probably already defended a dissertation proposal, chosen an advisor, and begun working with a committee. Sometimes, however, those three elements can prove to be major external sources of frustration. So how can you manage them to help yourself be as productive as possible?

Managing your topic

Remember that your topic is not carved in stone . The research and writing plan suggested in your dissertation proposal was your best vision of the project at that time, but topics evolve as the research and writing progress. You might need to tweak your research question a bit to reduce or adjust the scope, you might pare down certain parts of the project or add others. You can discuss your thoughts on these adjustments with your advisor at your check ins.

Think about variables that could be cut down and how changes would affect the length, depth, breadth, and scholarly value of your study. Could you cut one or two experiments, case studies, regions, years, theorists, or chapters and still make a valuable contribution or, even more simply, just finish?

Talk to your advisor about any changes you might make . They may be quite sympathetic to your desire to shorten an unwieldy project and may offer suggestions.

Look at other dissertations from your department to get a sense of what the chapters should look like. Reverse-outline a few chapters so you can see if there’s a pattern of typical components and how information is sequenced. These can serve as models for your own dissertation. See this video on reverse outlining to see the technique.

Managing your advisor

Embrace your evolving status . At this stage in your graduate career, you should expect to assume some independence. By the time you finish your project, you will know more about your subject than your committee does. The student/teacher relationship you have with your advisor will necessarily change as you take this big step toward becoming their colleague.

Revisit the alliance . If the interaction with your advisor isn’t matching the original agreement or the original plan isn’t working as well as it could, schedule a conversation to revisit and redesign your working relationship in a way that could work for both of you.

Be specific in your feedback requests . Tell your advisor what kind of feedback would be most helpful to you. Sometimes an advisor can be giving unhelpful or discouraging feedback without realizing it. They might make extensive sentence-level edits when you really need conceptual feedback, or vice-versa, if you only ask generally for feedback. Letting your advisor know, very specifically, what kinds of responses will be helpful to you at different stages of the writing process can help your advisor know how to help you.

Don’t hide . Advisors can be most helpful if they know what you are working on, what problems you are experiencing, and what progress you have made. If you haven’t made the progress you were hoping for, it only makes it worse if you avoid talking to them. You rob yourself of their expertise and support, and you might start a spiral of guilt, shame, and avoidance. Even if it’s difficult, it may be better to be candid about your struggles.

Talk to other students who have the same advisor . You may find that they have developed strategies for working with your advisor that could help you communicate more effectively with them.

If you have recurring problems communicating with your advisor , you can make a change. You could change advisors completely, but a less dramatic option might be to find another committee member who might be willing to serve as a “secondary advisor” and give you the kinds of feedback and support that you may need.

Managing your committee

Design the alliance . Talk with your committee members about how much they’d like to be involved in your writing process, whether they’d like to see chapter drafts or the complete draft, how frequently they’d like to meet (or not), etc. Your advisor can guide you on how committees usually work, but think carefully about how you’d like the relationship to function too.

Keep in regular contact with your committee , even if they don’t want to see your work until it has been approved by your advisor. Let them know about fellowships you receive, fruitful research excursions, the directions your thinking is taking, and the plans you have for completion. In short, keep them aware that you are working hard and making progress. Also, look for other ways to get facetime with your committee even if it’s not a one-on-one meeting. Things like speaking with them at department events, going to colloquiums or other events they organize and/or attend regularly can help you develop a relationship that could lead to other introductions and collaborations as your career progresses.

Share your struggles . Too often, we only talk to our professors when we’re making progress and hide from them the rest of the time. If you share your frustrations or setbacks with a knowledgeable committee member, they might offer some very helpful suggestions for overcoming the obstacles you face—after all, your committee members have all written major research projects before, and they have probably solved similar problems in their own work.

Stay true to yourself . Sometimes, you just don’t entirely gel with your committee, but that’s okay. It’s important not to get too hung up on how your committee does (or doesn’t) relate to you. Keep your eye on the finish line and keep moving forward.

Helpful websites:

Graduate School Diversity Initiatives : Groups and events to support the success of students identifying with an affinity group.

Graduate School Career Well : Extensive professional development resources related to writing, research, networking, job search, etc.

CAPS Therapy Groups : CAPS offers a variety of support groups, including a dissertation support group.

Advice on Research and Writing : Lots of links on writing, public speaking, dissertation management, burnout, and more.

How to be a Good Graduate Student: Marie DesJardins’ essay talks about several phases of the graduate experience, including the dissertation. She discusses some helpful hints for staying motivated and doing consistent work.

Preparing Future Faculty : This page, a joint project of the American Association of Colleges and Universities, the Council of Graduate Schools, and the Pew Charitable Trusts, explains the Preparing Future Faculty Programs and includes links and suggestions that may help graduate students and their advisors think constructively about the process of graduate education as a step toward faculty responsibilities.

Dissertation Tips : Kjell Erik Rudestam, Ph.D. and Rae Newton, Ph.D., authors of Surviving Your Dissertation: A Comprehensive Guide to Content and Process.

The ABD Survival Guide Newsletter : Information about the ABD Survival Guide newsletter (which is free) and other services from E-Coach (many of which are not free).

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Login or sign up to be automatically entered into our next $10,000 scholarship giveaway

Get Started

- College Search

- College Search Map

- Graduate Programs

- Featured Colleges

- Scholarship Search

- Lists & Rankings

- User Resources

Articles & Advice

- All Categories

- Ask the Experts

- Campus Visits

- Catholic Colleges and Universities

- Christian Colleges and Universities

- College Admission

- College Athletics

- College Diversity

- Counselors and Consultants

- Education and Teaching

- Financial Aid

- Graduate School

- Health and Medicine

- International Students

- Internships and Careers

- Majors and Academics

- Performing and Visual Arts

- Public Colleges and Universities

- Science and Engineering

- Student Life

- Transfer Students

- Why CollegeXpress

- $10,000 Scholarship

- CollegeXpress Store

- Corporate Website

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- CA and EU Privacy Policy

Articles & Advice > Graduate School > Articles