- 2022 Best Tech

- Creating a Lasting Impact on the Future of Sight

- Opt-Out Screening for STIs

- RSV Roundtable

- Food Insecurity and the Dangers of Infant Formula Dilution

- Opt-Out Chlamydia Screening in Adolescent Care

- Pediatric ADHD: Zeroing in on an Untenable Burden

- The Role of the Healthcare Provider Community in Increasing Public Awareness of RSV in All Infants

- Update in Pediatric COVID-19 Vaccines

- Publications

- Conferences

- Partnerships

Case Studies

If you are interested in submitting a Puzzler of your own, please see Puzzler guidelines here .

Quiz: Can you diagnose these muscle spasms in a 19-year-old-male?

Take this Contemporary Pediatrics quiz, and see if you can correctly diagnose the patient in this case study. Submit your answer to see if you were correct.

11-year-old boy with testicular pain and rash

An 11-year-old boy presented to the emergency department complaining of left testicular pain for 2 days, described as intermittent and stabbing, which ranged between 5 and 8 of 10 in intensity. Read the full case to see if you can correctly diagnose the patient.

Newborn with midline neck lesion

A 4-day-old boy with a midline neck lesion was born at term by normal vaginal delivery. After birth, mid line lesion had the configuration of a linear cleft with a cephalocaudal orientation, extending from the level below the hyoid bone to the suprasternal notch with a length of 2.5 cm and a width of 0.5 cm. What's the diagnosis?

A 13-year-old girl with well-demarcated rash on back and chest

A healthy 13-year-old girl presented with a 1-month history of an asymptomatic, well-demarcated rash on her back and upper chest. The eruption consisted of discrete, dark brown papules that coalesced into large, flat-topped plaques with mild superficial scale and accentuation of skin markings. What's the diagnosis?

Suspicious facial swelling in a 22-month-old girl

A 22-month-old female patient with sickle cell disease on folic acid and penicillin prophylaxis with a 3-day history of nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, fever and decreased oral intake presents to the emergency department (ED) for acute facial swelling noted when she woke up from a nap. What's the diagnosis?

Friction-induced blistering on a child’s feet

You are called to the hospital nursery to evaluate a healthy full-term newborn boy who developed painful flaccid blisters and erosions on the tops of his feet and ankles shortly after birth. His mother had a history of similar recurrent skin lesions that healed with scarring. She also had oral and gastrointestinal tract involvement. What's the diagnosis?

Hypothermia and abnormal eye movements in a 5-week-old infant

A 5-week-old female infant born at 38 weeks presents to her pediatrician with abnormal eye movements. What’s the diagnosis?

Neonate experiences coffee ground emesis

The infant did not show signs of illness; her mother experienced a routine pregnancy and prenatal lab test results were normal. What is the diagnosis?

Muscle spasms in a 19-year-old male

A 19-year-old male presents to the emergency department (ED) with headache and fever of 4 days’ duration. Six days earlier, his left palm had been punctured by a rusty nail. What's the diagnosis?

Treating an 18-month-old who tested positive for cannabis exposure

As more and more states legalize recreational marijuana, caregivers need to be vigilant about keeping products out of reach of children.

Scalp thickening and folding in a pubertal boy

A 16-year-old boy with developmental delay and intellectual disability developed dramatic chronic wrinkling of his scalp over a year ago. The lesions were persistent but not symptomatic. What's the diagnosis?

Worsening acne after isotretinoin treatment in an adolescent girl

A healthy 17-year-old girl with inflammatory acne had failed to respond to topical tretinoin, benzoyl peroxide, and oral minocycline. What's the diagnosis?

Psychosis in an 18-year-old male

Alex, an 18-year-old male, presented to the emergency department with a 4-day history of paranoia, agitation, and disorganized behavior. He had no psychiatric history or prior mental health contact and no known medical conditions.

Congenital hypopigmented macules on a healthy child

You are asked to evaluate an African American boy aged 4 years with a birthmark on his back and right arm. He is healthy with normal growth and development. What's the diagnosis?

Just a little birthmark?

You are asked to evaluate a healthy 1.5-day-old girl who has a congenital red patch with coarse telangiectasias and a surrounding ring of pallor on the right shoulder. What's your diagnosis?

Can intranasal corticosteroids improve obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in children?

A study featured at CHEST 2022 investigated INCS in children with OSAS to determine if the therapy improved their symptoms, polysomnography findings, behavior, and quality of life.

Case of inflammatory acne or something else?

This case study analyzes variants of majocchi granuloma and potential treatment.

A case of late-onset group B Streptococcus infection in fraternal twins

A 29-year-old White woman presented to the labor and delivery unit due to preterm premature rupture of membranes and delivered twins. The twins were transferred to the neonatal intensive care unit following delivery.

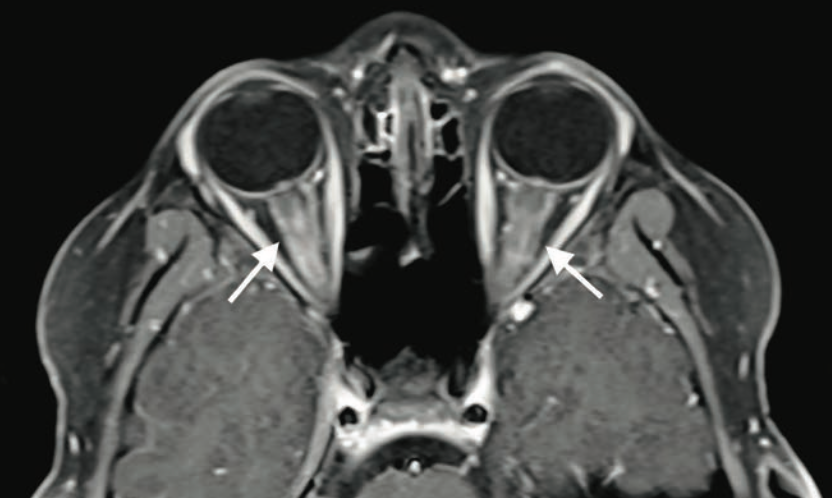

Bilateral blurry vision in a 9-year-old boy

A 9-year-old boy with no significant medical history presented to the emergency department with 2 days of painless blurry vision. What's the diagnosis?

A case of shin guard dermatitis?

A healthy 14-year old boy was evaluated for an intensely pruritic shin rash that developed 2 weeks prior and had been treated with oral antibiotics for 10 days.

A renal anomaly? Look for a Müllerian anomaly as well

A retrospective study found that postmenarchal women with a renal anomaly were also at risk of having a Müllerian anomaly.

A case of progressive joint pain and rash in a 5-year-old

A 5-year-old nonverbal boy with autism spectrum disorder and global developmental delay presented to the emergency department with bilateral lower-extremity bruising and progressive difficulty ambulating. What's the diagnosis?

Fever and facial swelling in a neonate

An 18-day-old girl whose right cheek had become increasingly red and warm over 24 hours was directly admitted to an inpatient unit. She had firmness and pain to the affected area, fussiness, increased sleeping, and poor feeding, preferring the bottle to breastfeeding. What's the diagnosis?

Altered mental state in a 2-year-old boy

A 26-month-old boy presents for mild altered mental status and balance issues following a fall the day before. There was no loss of consciousness or vomiting but he subsequently complained of left-sided head pain. What's the diagnosis?

Painful red lumpy leg

A healthy 4-year-old boy presents with painful deep-seated bumps on the front of his right leg. He also complains of a sore throat for the last 4 days. What's the diagnosis?

Severe hemorrhage from infantile hemangioma

A 5-month-old girl with a large scalp infantile hemangioma (IH), present since 6 weeks of age, is evaluated in the emergency department for lethargy and pallor.

Generalized, eruptive lichen planus in a pediatric patient

A healthy 14-year-old boy presented at our dermatology practice with acute onset of an intensely itchy rash that first appeared 2 months prior.

Annular scars with hyperpigmentation

An 18-month-old girl presents with ringed scars with hyperpigmentation on the right side of her buttocks and back. What's the diagnosis?

Lower-extremity nodules in a 2-year-old girl

A 2-year-old girl presents with an itchy, bilateral leg rash. Additionally, the child had several bruises that felt like "hard welts" and were warm to the touch. What's the diagnosis?

Persistent foot and leg swelling in a 17-year-old female

A 17-year-old girl presents with a 2-year history of unilateral swelling of the left lower extremity as well as a poorly healed ankle sprain of the affected extremity 3 years prior that slowly resolved but left persistent swelling. What's the diagnosis?

2 Commerce Drive Cranbury, NJ 08512

609-716-7777

Paediatrics

Showing results 1 - 10 of 100

Sorted by most recent

10 May 2024

16 April 2024

11 April 2024

8 April 2024

We have a new app!

Take the Access library with you wherever you go—easy access to books, videos, images, podcasts, personalized features, and more.

Download the Access App here: iOS and Android . Learn more here!

- Remote Access

- Save figures into PowerPoint

- Download tables as PDFs

- Case Files®: Pediatrics

- Pediatrics Examination and Board Review

- Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine: Specialty Board Review

- Symptom-Based Diagnosis in Pediatrics

Case Files: Pediatrics, 6e

Author(s): Eugene C. Toy; Mark D. Hormann; Robert J. Yetman; Margaret C. McNeese; Sheela L. Lahoti; Emma A. Omoruyi; Abby M. Geltemeyer

- 2 Infant of a Diabetic Mother

- 3 Neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia

- 4 Sepsis and Group B Streptococcal Infections

- 6 Neonatal Herpes Simplex Virus Infection

- 8 Transient Tachypnea of the Newborn

- 10 Failure to Thrive

- 38 Child Abuse

- 14 Pneumonia

- 17 Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

- 27 Bacterial Meningitis

- 28 Bacterial Enteritis

- 40 Immunodeficiency

- 54 Appendicitis

- 55 Acute Epstein-Barr Virus (Infectious Mononucleosis)

- 29 Subdural Hematoma

- 30 Complex Febrile Seizure

- 48 Migraine Without Aura

- 56 Myasthenia Gravis

- 60 Concussion

- 22 Patent Ductus Arteriosus With Heart Failure

- 23 Truncus Arteriosus

- 18 Cystic Fibrosis

- 20 Asthma Exacerbation

- 61 Electronic Cigarette or Vaping Induced Acute Lung Injury (EVALI) Online Only

- 7 Esophageal Atresia

- 15 Rectal Bleeding

- 34 Intestinal Malrotation

- 53 Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- 35 Posterior Urethral Valves

- 52 Acute Postinfectious Glomerulonephritis

- 11 Anemia in the Pediatric Patient

- 13 Sickle Cell Disease With Vaso-Occlusive Crisis

- 19 Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

- 33 Suspected Neuroblastoma

- 42 Diabetic Ketoacidosis

- 44 Growth Hormone Deficiency

- 45 Precocious Puberty

- 41 Trisomy 21

- 50 Turner Syndrome

- 37 Immune Thrombocytopenic Purpura

- 39 Kawasaki Disease

- 51 Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

- 57 Oligoarticular Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis

- 58 Anaphylactoid Purpura (Henoch-Schönlein Purpura)

- 49 Adolescent Substance Use Disorder

- 62 Alopecia Areata Online Only

- 5 Accidental Ingestion of Opioids

- 25 Lead Ingestion (Microcytic Anemia)

- 59 Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

- 31 Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy

- 36 Nursemaid’s Elbow (Radial Head Subluxation)

- 47 Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis

- 1 Infant Rashes

- 26 Stevens-Johnson Syndrome

- 32 Atopic Dermatitis

- 9 Congenital Cataracts

- 16 Acute Otitis Media

- 43 Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome

- 46 Retropharyngeal Abscess

- 21 Sudden Infant Death Syndrome

- Accidental Ingestion of Opioids

- Acute Epstein-Barr Virus (Infectious Mononucleosis)

- Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

- Acute Otitis Media

- Acute Postinfectious Glomerulonephritis

- Adolescent Substance Use Disorder

- Alopecia Areata Online Only

- Anaphylactoid Purpura (Henoch-Schönlein Purpura)

- Anemia in the Pediatric Patient

- Appendicitis

- Asthma Exacerbation

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

- Bacterial Enteritis

- Bacterial Meningitis

- Child Abuse

- Complex Febrile Seizure

- Congenital Cataracts

- Cystic Fibrosis

- Diabetic Ketoacidosis

- Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy

- Electronic Cigarette or Vaping Induced Acute Lung Injury (EVALI) Online Only

- Esophageal Atresia

- Failure to Thrive

- Growth Hormone Deficiency

- Immune Thrombocytopenic Purpura

- Immunodeficiency

- Infant of a Diabetic Mother

- Infant Rashes

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- Intestinal Malrotation

- Kawasaki Disease

- Lead Ingestion (Microcytic Anemia)

- Migraine Without Aura

- Myasthenia Gravis

- Neonatal Herpes Simplex Virus Infection

- Neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia

- Nursemaid’s Elbow (Radial Head Subluxation)

- Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome

- Oligoarticular Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis

- Patent Ductus Arteriosus With Heart Failure

- Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

- Posterior Urethral Valves

- Precocious Puberty

- Rectal Bleeding

- Retropharyngeal Abscess

- Sepsis and Group B Streptococcal Infections

- Sickle Cell Disease With Vaso-Occlusive Crisis

- Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis

- Stevens-Johnson Syndrome

- Subdural Hematoma

- Sudden Infant Death Syndrome

- Suspected Neuroblastoma

- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

- Transient Tachypnea of the Newborn

- Truncus Arteriosus

- Turner Syndrome

Masks Strongly Recommended but Not Required in Maryland, Starting Immediately

Due to the downward trend in respiratory viruses in Maryland, masking is no longer required but remains strongly recommended in Johns Hopkins Medicine clinical locations in Maryland. Read more .

- Vaccines

- Masking Guidelines

- Visitor Guidelines

Center for Bloodless Medicine and Surgery

Case study: pediatrics, bloodless surgical treatment of a medulloblastoma in a 9-year old boy.

A 9-year old boy presented with loss of balance, headache, vomiting, double vision and was found to have a large left cerebellar brain tumor (5.6x4.8x4.8cm) extending to the margin of the fourth ventricle. An MRI showed no evidence of metastasis. As soon as the surgery was posted, the patient was placed on oral iron supplements (325 mg Ferrous Sulfate, twice a day). A discussion with the parents about Bloodless Medicine revealed their wish to avoid transfusion of the major blood fractions (red blood cells, plasma, or platelets) but they agreed to minor fractions (albumin, cryoprecipitate), as well as autologous blood salvage (Cell Saver) if necessary. We explained the risks and benefits of using Cell Saver blood in Oncology cases, including the use of special filters (leukoreduction filters), which have been shown to remove cancer cells. The clinical and legal aspects of parents requesting to avoid transfusion for their children who are under 18 years of age were discussed. Our team informed the parents that we would do everything to avoid transfusion, however, if it came to a life or death situation, we could not honor the parents' wishes. The parents were comforted to know that all blood conserving measures would be implemented.

The surgical procedure was a suboccipital craniotomy for cerebellar tumor, which was performed under general anesthesia provided by the pediatric anesthesia team. Blood loss was 600 mLs, which represented 25% of his total blood volume. This calculation is based on 80 mLs/kg total blood volume in a 30 Kg child or 2,400 mLs. With a 25% blood loss we expected a 25% decrease in hemoglobin level, which is exactly what occurred. The preoperative hemoglobin level was 12.5 g/dL, and the postoperative level was 9.4. Because the tumor was adherent to the ventricles, the plan was to bring him back for a second surgery 4-6 weeks later. At that time a complete resection after chemo and radiation therapy with a regimen prescribed by the National Cancer Institute under protocol ACNS0331 for standard risk medulloblastoma was planned. This involved radiotherapy in combination with chemotherapy comprising vincristine, cisplatin, lomustine, and cyclophosphamide.

Resection of the residual tumor was accomplished 6 weeks later with only 200 mLs of blood loss. At the end of the procedure an intraventricular drain was placed to prevent hydrocephalus from adhesions at the cervicomedullary junction. The intraventricular drain was removed two weeks later and a ventriculoperitoneal shunt was placed. Follow up care was provided at the Kennedy Kreiger Institute with audiology testing and physical therapy rehabilitation. Brain and spine MRIs as well as CSF from a lumbar puncture were negative for signs of tumor. His current hemoglobin level is 11.1 and he has not required a blood transfusion through all this treatment.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.15(10); 2023 Oct

- PMC10680406

A Brief Overview of Recent Pediatric Physical Therapy Practices and Their Importance

Chavan srushti sudhir.

1 Department of Paedatric Physiotherapy, Ravi Nair Physiotherapy College, Datta Meghe Institute of Higher Education & Research (Deemed to be University), Wardha, IND

H V Sharath

2 Department of Paediatric Physiotherapy, Ravi Nair Physiotherapy College, Datta Meghe Institute of Higher Education & Research (Deemed to be University), Wardha, IND

Recent years have seen a substantial increase in interest in pediatric physical therapy, which is a reflection of improvements in its methods and the rising understanding of its significance in child development and rehabilitation. This review provides a concise overview of the latest trends and techniques in pediatric physical therapy, emphasizing the integration of innovative technologies, evidence-based interventions, and holistic approaches. For children with varied developmental, congenital, and acquired disorders, the significance of early intervention and individualized treatment programs is emphasized, underlining the important influence of prompt interventions on long-term functional results and quality of life. To guarantee comprehensive and coordinated care, the study also examines the interdisciplinary character of pediatric physical therapy placing special emphasis on collaboration with families, caregivers, educators, and healthcare professionals. It also emphasizes the importance of continuing research, instruction, and lobbying to improve the effectiveness and availability of pediatric physical therapy services, eventually promoting the overall well-being of kids and their families.

Introduction and background

Pediatric physical therapy is a branch of physiotherapy that helps treat or develop movement issues in infants and young children and enhances a child's developmental stages. Orthopedics, congenital malformations, neurology, neuropsychiatry, respiration, and preterm are among the systems that affect children [ 1 ]. Pediatric physical therapists address developmental delay and neuromotor disorders. They treat children of all ages, from infants to teenagers, and they have particular knowledge and training in growth and development, syndromes, and diagnosis (Table (Table1) 1 ) [ 2 ].

The pediatric physical therapist may collaborate with a wide range of specialists due to the complicated requirements of the child and the family, including teams from medicine, nursing, social work, education, and psychiatry, as well as speech and occupational therapists [ 3 , 4 ]. Even though India is still in its infancy, the breadth has significantly expanded in the last several years to decades. Despite this point of view, there is controversy around using therapeutic touch in pediatric physical therapy, particularly for children with cerebral palsy [ 5 , 6 ]. Physiotherapists who work with children are experts in evaluating, identifying, diagnosing, and treating movement abnormalities and physiological conditions (Table (Table2). 2 ). They treat children (infants up to 19 years) in the areas of orthopedics, congenital anomalies, neurology, neuropsychiatry, breathing, and preterm [ 7 - 9 ].

ASD: autism spectrum disorder; ADHD: attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; ARDS: acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Study selection

We included all research articles like randomized and non-randomized clinical studies, systematic reviews, and experimental studies of recent pediatric physical practices over the past five years; the English-language literature was searched on Google Scholar, Medline, Cochrane Library, and PubMed. Between 2019 and March 2023, 346 articles were searched using the terms paediatric physiotherapy, modern treatment practices, and advanced physiotherapy. Twenty-three papers were included in the 50 articles eligible for full-text review out of the 346 articles (Figure 1 ), which displays a database search, and data extraction demonstrates the outcome of the article selection process. A list of the examined papers is shown in Table Table3, 3 , which provides a quick summary of current pediatric physical procedures.

GMA: General Movement Assessment; AIMS: Alberta Infant Motor Scale; NDD: Neurodevelopmental Delay; IH: Intermittent Hypoxia; LRT: Lower Respiratory Tract; NDT-B: Neurodevelopmental Therapy Method-Bobath; CMT: Congenital Muscular Torticollis; NTDs: Neural Tube Defects; SB: Spina Bifida; SSC: Stretch Shortening Cycle; DS: Down Syndrome; ADHD: Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder; HCs: Healthy Asymptomatic Controls; MOOSE: Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology; NBPP: Newborn Brachial Plexus Palsy.

PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Pediatric physical therapists give outstanding care to everyone, from infants in the neonatal intensive care unit to young adults with childhood illnesses. Worldwide, prematurity is the leading cause of neonatal deaths, and pneumonia is the second-leading cause of death among children under five. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), India has the world's highest rate of preterm deliveries (Table 4 ). Studies have shown that early intervention therapy and chest physiotherapy for neonatal intensive care unit secretion clearance that comprises manual hyperinflation and vibrations significantly reduce the preterm death ratio. Even children who are malnourished can benefit from physical therapy to build muscle while they are recovering. For children with cerebral palsy, the most cutting-edge treatment, Pedi suit/Rehab suit therapy, is required. The benefits of multimodal stimulation for preterm infants include promoting eating and psychomotor growth. The multimodal stimulus has also been shown to enhance visual function. The General Movement Assessment approach is utilized for baby neurodevelopment. It is a method that aids in the early diagnosis of cerebral palsy. The Albert Infant Motor Scale and Optimality Score are two components of the General Movement Assessment. The handling techniques are especially useful in respiratory disorders like the incidence of intermittent hypoxemia, where it is stated that touch features are basic trigger mechanisms for intermittent hypoxemia [ 31 - 33 ].

Refs. [ 1 - 35 ].

Deformities involving muscles, tissue, or joints are included in musculoskeletal conditions. Exercises for stretching, handling placement, and strengthening are used to treat this issue [ 34 ]. Even adjustments to the surroundings help treat the illnesses. Higher-level data are emerging in favor of microcurrent therapy for torticollis. As the cesarean section appears to be a precaution, Erb's palsy, also known as neonatal brachial plexus palsy, is decreasing. Physiotherapy therapies are useful in assisting and enhancing the range of motion, strength, and functional recovery after brachial plexus and polytrauma injuries. One of the cardiorespiratory illnesses is acute respiratory disorder syndrome (ARDS). In premature neonates, chest physical therapy can treat lung issues. The Vojta approach is useful for treating lung problems in chest physical therapy. Both prone and supine positions were used while measuring oxygen saturation, partial pressure of arterial oxygen, oxygenation index, and thoracoabdominal synchronization [ 35 ].

Children with cerebral palsy are offered stretches and progressive resistance exercises to maintain and build strength. The core stability activities also improve children's balance and coordination. Patients with cerebral palsy and feeding issues might use the Bobath techniques for neurodevelopmental therapy to help with feeding and swallowing tasks. The spastic diplegic condition that children experience in cerebral palsy may be supported by simultaneous proprioceptive and visual training, but it has little or no impact on kinetic gait characteristics. Stretch-shortening cycle exercises based on the trampoline are used to address children's postural control issues as well as to improve strength in children with Down syndrome. Pediatric physiotherapists have a bright future in the rehabilitation of young athletes. Depending on the child's needs, a therapist will undertake sports conditioning, which may involve balance, proprioception, agility, coordination training, postural and gait retraining, dynamic core strengthening, and flexibility training. This is done to reduce the likelihood of sports-related injuries [ 12 ].

Limitations

The limitation of the topic presents a difficulty in fully encompassing the broad range of current pediatric physical therapy approaches and their significance within the context of this review. The overview may not adequately cover all the specific methods, case studies, or clinical applications needed for a complete grasp of pediatric physical therapy practices because of being very condensed.

Furthermore, given that these factors can have a substantial impact on the execution and efficacy of the interventions, the brief summary might not fully address regional or cultural variations in pediatric physical therapy practices. The review does not take into consideration the variations in access to pediatric physical therapy treatments and different socioeconomic backgrounds, which could restrict the generalizability of the findings to all populations and communities.

Additionally, the review might not go into great detail on the difficulties and barriers that pediatric physical therapists encounter in actual clinical settings, such as resource limitations, staffing problems, and changing healthcare regulations. These difficulties, which are so important in determining how pediatric physical therapy services are actually provided, might not be adequately covered in a succinct description. The succinct summary can also miss some important trends and future developments in pediatric physical therapy, such as the potential effects of new interdisciplinary collaborations, technological innovations, and scientific breakthroughs. These factors are essential for comprehending the changing environment of pediatric physical therapy and assuring its ongoing expansion and efficacy. As a result, while providing an insightful introduction, the succinct overview might not fully capture the breadth and depth of the topic of pediatric physical therapy, leaving room for further exploration and analysis.

Conclusions

This study focuses on the current situation of physiotherapy techniques for resolving and enhancing the issues that are developing in pediatric patients. In conclusion, pediatric diseases like spina bifida, congenital torticollis, and cerebral palsy can be managed and improved with physiotherapy. The in-depth investigation reveals the widespread usage of strengthening and stretching workouts for condition control. Beyond correcting errors, it encourages children's physical, cognitive, emotional, and social development, enabling them to realize their full potential. Additionally, the use of cutting-edge methods and technology has improved pediatric physical therapy's effectiveness and engagement levels, improving the experience for patients as a whole. A child's sense of independence and self-confidence are also fostered by therapists in addition to physical disabilities. The importance of pediatric physical therapy must be acknowledged and supported by healthcare professionals, carers, and legislators as the discipline develops. By doing this, we can work together to give physically challenged children a better future, so that they can have healthier, more contented lives. Pediatric physical therapy is a glimmer of hope and advancement for the most impressionable individuals of our society in this constantly changing environment.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

- Open access

- Published: 09 May 2024

Evaluation of integrated community case management of the common childhood illness program in Gondar city, northwest Ethiopia: a case study evaluation design

- Mekides Geta 1 ,

- Geta Asrade Alemayehu 2 ,

- Wubshet Debebe Negash 2 ,

- Tadele Biresaw Belachew 2 ,

- Chalie Tadie Tsehay 2 &

- Getachew Teshale 2

BMC Pediatrics volume 24 , Article number: 310 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

89 Accesses

Metrics details

Integrated Community Case Management (ICCM) of common childhood illness is one of the global initiatives to reduce mortality among under-five children by two-thirds. It is also implemented in Ethiopia to improve community access and coverage of health services. However, as per our best knowledge the implementation status of integrated community case management in the study area is not well evaluated. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the implementation status of the integrated community case management program in Gondar City, Northwest Ethiopia.

A single case study design with mixed methods was employed to evaluate the process of integrated community case management for common childhood illness in Gondar town from March 17 to April 17, 2022. The availability, compliance, and acceptability dimensions of the program implementation were evaluated using 49 indicators. In this evaluation, 484 mothers or caregivers participated in exit interviews; 230 records were reviewed, 21 key informants were interviewed; and 42 observations were included. To identify the predictor variables associated with acceptability, we used a multivariable logistic regression analysis. Statistically significant variables were identified based on the adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) and p-value. The qualitative data was recorded, transcribed, and translated into English, and thematic analysis was carried out.

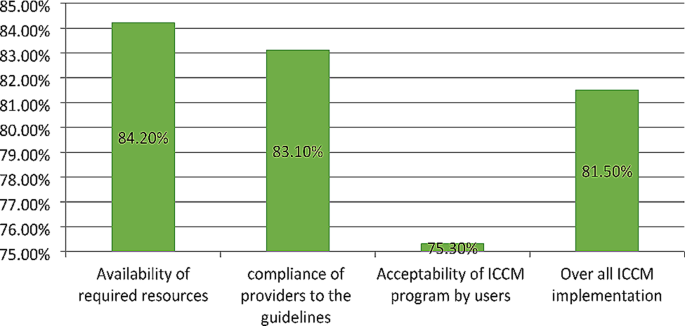

The overall implementation of integrated community case management was 81.5%, of which availability (84.2%), compliance (83.1%), and acceptability (75.3%) contributed. Some drugs and medical equipment, like Cotrimoxazole, vitamin K, a timer, and a resuscitation bag, were stocked out. Health care providers complained that lack of refreshment training and continuous supportive supervision was the common challenges that led to a skill gap for effective program delivery. Educational status (primary AOR = 0.27, 95% CI:0.11–0.52), secondary AOR = 0.16, 95% CI:0.07–0.39), and college and above AOR = 0.08, 95% CI:0.07–0.39), prescribed drug availability (AOR = 2.17, 95% CI:1.14–4.10), travel time to the to the ICCM site (AOR = 3.8, 95% CI:1.99–7.35), and waiting time (AOR = 2.80, 95% CI:1.16–6.79) were factors associated with the acceptability of the program by caregivers.

Conclusion and recommendation

The overall implementation status of the integrated community case management program was judged as good. However, there were gaps observed in the assessment, classification, and treatment of diseases. Educational status, availability of the prescribed drugs, waiting time and travel time to integrated community case management sites were factors associated with the program acceptability. Continuous supportive supervision for health facilities, refreshment training for HEW’s to maximize compliance, construction clean water sources for HPs, and conducting longitudinal studies for the future are the forwarded recommendation.

Peer Review reports

Integrated Community Case Management (ICCM) is a critical public health strategy for expanding the coverage of quality child care services [ 1 , 2 ]. It mainly concentrated on curative care and also on the diagnosis, treatment, and referral of children who are ill with infectious diseases [ 3 , 4 ].

Based on the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) recommendations, Ethiopia adopted and implemented a national policy supporting community-based treatment of common childhood illnesses like pneumonia, Diarrhea, uncomplicated malnutrition, malaria and other febrile illness and Amhara region was one the piloted regions in late 2010 [ 5 ]. The Ethiopian primary healthcare units, established at district levels include primary hospitals, health centers (HCs), and health posts (HPs). The HPs are run by Health Extension Workers (HEWs), and they have function of monitoring health programs and disease occurrence, providing health education, essential primary care services, and timely referrals to HCs [ 6 , 7 ]. The Health Extension Program (HEP) uses task shifting and community ownership to provide essential health services at the first level using the health development army and a network of woman volunteers. These groups are organized to promote health and prevent diseases through community participation and empowerment by identifying the salient local bottlenecks which hinder vital maternal, neonatal, and child health service utilization [ 8 , 9 ].

One of the key steps to enhance the clinical case of health extension staff is to encourage better growth and development among under-five children by health extension. Healthy family and neighborhood practices are also encouraged [ 10 , 11 ]. The program also combines immunization, community-based feeding, vitamin A and de-worming with multiple preventive measures [ 12 , 13 ]. Now a days rapidly scaling up of ICCM approach to efficiently manage the most common causes of morbidity and mortality of children under the age of five in an integrated manner at the community level is required [ 14 , 15 ].

Over 5.3 million children are died at a global level in 2018 and most causes (75%) are preventable or treatable diseases such as pneumonia, malaria and diarrhea [ 16 ]. About 99% of the global burden of mortality and morbidity of under-five children which exists in developing countries are due to common childhood diseases such as pneumonia, diarrhea, malaria and malnutrition [ 17 ].

In 2013, the mortality rate of under-five children in Sub-Saharan Africa decreased to 86 deaths per 1000 live birth and estimated to be 25 per 1000live births by 2030. However, it is a huge figure and the trends are not sufficient to reach the target [ 18 ]. About half of global under-five deaths occurred in sub-Saharan Africa. And from the top 26 nations burdened with 80% of the world’s under-five deaths, 19 are in sub-Saharan Africa [ 19 ].

To alleviate the burden, the Ethiopian government tries to deliver basic child care services at the community level by trained health extension workers. The program improves the health of the children not only in Ethiopia but also in some African nations. Despite its proven benefits, the program implementation had several challenges, in particular, non-adherence to the national guidelines among health care workers [ 20 ]. Addressing those challenges could further improve the program performance. Present treatment levels in sub-Saharan Africa are unacceptably poor; only 39% of children receive proper diarrhea treatment, 13% of children with suspected pneumonia receive antibiotics, 13% of children with fever receive a finger/heel stick to screen for malaria [ 21 ].

To improve the program performance, program gaps should be identified through scientific evaluations and stakeholder involvement. This evaluation not only identify gaps but also forward recommendations for the observed gaps. Furthermore, the implementation status of ICCM of common childhood illnesses has not been evaluated in the study area yet. Therefore, this work aimed to evaluate the implementation status of integrated community case management program implementation in Gondar town, northwest Ethiopia. The findings may be used by policy makers, healthcare providers, funders and researchers.

Method and material

Evaluation design and settings.

A single-case study design with concurrent mixed-methods evaluation was conducted in Gondar city, northwest Ethiopia, from March 17 to April 17, 2022. The evaluability assessment was done from December 15–30, 2021. Both qualitative and quantitative data were collected concurrently, analyzed separately, and integrated at the result interpretation phase.

The evaluation area, Gondar City, is located in northwest Ethiopia, 740 km from Addis Ababa, the capital city of the country. It has six sub-cities and thirty-six kebeles (25 urban and 11 rural). In 2019, the estimated total population of the town was 338,646, and 58,519 (17.3%) were under-five children. In the town there are eight public health centers and 14 health posts serving the population. All health posts provide ICCM service for more than 70,852 populations.

Evaluation approach and dimensions

Program stakeholders.

The evaluation followed a formative participatory approach by engaging the potential stakeholders in the program. Prior to the development of the proposal, an extensive discussion was held with the Gondar City Health Department to identify other key stakeholders in the program. Service providers at each health facility (HCs and HPs), caretakers of sick children, the Gondar City Health Office (GCHO), the Amhara Regional Health Bureau (ARHB), the Minister of Health (MoH), and NGOs (IFHP and Save the Children) were considered key stakeholders. During the Evaluability Assessment (EA), the stakeholders were involved in the development of evaluation questions, objectives, indicators, and judgment criteria of the evaluation.

Evaluation dimensions

The availability and acceptability dimensions from the access framework [ 22 ] and compliance dimension from the fidelity framework [ 23 ] were used to evaluate the implementation of ICCM.

Population and samplings

All under-five children and their caregivers attended at the HPs; program implementers (health extension workers, healthcare providers, healthcare managers, PHCU focal persons, MCH coordinators, and other stakeholders); and ICCM records and registries in the health posts of Gondar city administration were included in the evaluation. For quantitative data, the required sample size was proportionally allocated for each health post based on the number of cases served in the recent one month. But the qualitative sample size was determined by data saturation, and the samples were selected purposefully.

The data sources and sample size for the compliance dimension were all administrative records/reports and ICCM registration books (230 documents) in all health posts registered from December 1, 2021, to February 30, 2022 (three months retrospectively) included in the evaluation. The registries were assessed starting from the most recent registration number until the required sample size was obtained for each health post.

The sample size to measure the mothers’/caregivers’ acceptability towards ICCM was calculated by taking prevalence of caregivers’ satisfaction on ICCM program p = 74% from previously similar study [ 24 ] and considering standard error 4% at 95% CI and 10% non- responses, which gave 508. Except those who were seriously ill, all caregivers attending the ICCM sites during data collection were selected and interviewed consecutively.

The availability of required supplies, materials and human resources for the program were assessed in all 14HPs. The data collectors observed the health posts and collected required data by using a resources inventory checklist.

A total of 70 non-participatory patient-provider interactions were also observed. The observations were conducted per each health post and for health posts which have more than one health extension workers one of them were selected randomly. The observation findings were used to triangulate the findings obtained through other data collection techniques. Since people may act accordingly to the standards when they know they are observed for their activities, we discarded the first two observations from analysis. It is one of the strategies to minimize the Hawthorne effect of the study. Finally a total of 42 (3 in each HPs) observations were included in the analysis.

Twenty one key informants (14 HEWs, 3 PHCU focal person, 3 health center heads and one MCH coordinator) were interviewed. These key informants were selected since they are assumed to be best teachers in the program. Besides originally developed key informant interview questions, the data collectors probed them to get more detail and clear information.

Variables and measurement

The availability of resources, including trained healthcare workers, was examined using 17 indicators, with weighted score of 35%. Compliance was used to assess HEWs’ adherence to the ICCM treatment guidelines by observing patient-provider interactions and conducting document reviews. We used 18 indicators and a weighted value of 40%.

Mothers’ /caregivers’/ acceptance of ICCM service was examined using 14 indicators and had a weighted score of 25%. The indicators were developed with a five-point Likert scale (1: strongly disagree, 2: disagree, 3: neutral, 4: agree and 5: strongly agree). The cut off point for this categorization was calculated using the demarcation threshold formula: ( \(\frac{\text{t}\text{o}\text{t}\text{a}\text{l}\, \text{h}\text{i}\text{g}\text{h}\text{e}\text{s}\text{t}\, \text{s}\text{c}\text{o}\text{r}\text{e}-\,\text{t}\text{o}\text{t}\text{a}\text{l}\, \text{l}\text{o}\text{w}\text{e}\text{s}\text{t} \,\text{s}\text{c}\text{o}\text{r}\text{e}}{2}) +total lowest score\) ( 25 – 27 ). Those mothers/caregivers/ who scored above cut point (42) were considered as “satisfied”, otherwise “dissatisfied”. The indicators were adapted from the national ICCM and IMNCI implementation guideline and other related evaluations with the participation of stakeholders. Indicator weight was given by the stakeholders during EA. Indicators score was calculated using the formula \(\left(achieved \,in \%=\frac{indicator \,score \,x \,100}{indicator\, weight} \right)\) [ 26 , 28 ].

The independent variables for the acceptability dimension were socio-demographic and economic variables (age, educational status, marital status, occupation of caregiver, family size, income level, and mode of transport), availability of prescribed drugs, waiting time, travel time to ICCM site, home to home visit, consultation time, appointment, and source of information.

The overall implementation of ICCM was measured by using 49 indicators over the three dimensions: availability (17 indicators), compliance (18 indicators) and acceptability (14 indicators).

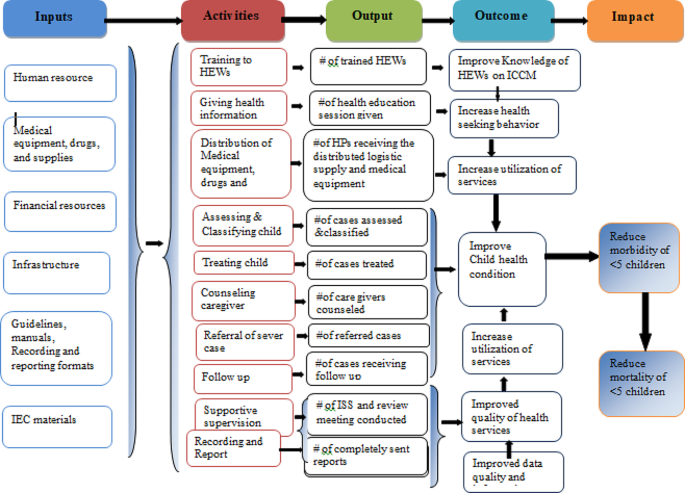

Program logic model

Based on the constructed program logic model and trained health care providers, mothers/caregivers received health information and counseling on child feeding; children were assessed, classified, and treated for disease, received follow-up; they were checked for vitamin A; and deworming and immunization status were the expected outputs of the program activities. Improved knowledge of HEWs on ICCM, increased health-seeking behavior, improved quality of health services, increased utilization of services, improved data quality and information use, and improved child health conditions are considered outcomes of the program. Reduction of under-five morbidity and mortality and improving quality of life in the society are the distant outcomes or impacts of the program (Fig. 1 ).

Integrated community case management of childhood illness program logic model in Gondar City in 2022

Data collection tools and procedure

Resource inventory and data extraction checklists were adapted from standard ICCM tool and check lists [ 29 ]. A structured interviewer administered questionnaire was adapted by referring different literatures [ 30 , 31 ] to measure the acceptability of ICCM. The key informant interview (KII) guide was also developed to explore the views of KIs. The interview questionnaire and guide were initially developed in English and translated into the local language (Amharic) and finally back to English to ensure consistency. All the interviews were done in the local language, Amharic.

Five trained clinical nurses and one BSC nurse were recruited from Gondar zuria and Wegera district as data collectors and supervisors, respectively. Two days training on the overall purpose of the evaluation and basic data collection procedures were provided prior to data collection. Then, both quantitative and qualitative data were gathered at the same time. The quantitative data were gathered from program documentation, charts of ICCM program visitors and, exit interview. Interviews with 21 KIIs and non-participatory observations of patient-provider interactions were used to acquire qualitative data. Key informant interviews were conducted to investigate the gaps and best practices in the implementation of the ICCM program.

A pretest was conducted to 26 mothers/caregivers/ at Maksegnit health post and appropriate modifications were made based on the pretest results. The data collectors were supervised and principal evaluator examined the completeness and consistency of the data on a daily basis.

Data management and analysis

For analysis, quantitative data were entered into epi-data version 4.6 and exported to Stata 14 software for analysis. Narration and tabular statistics were used to present descriptive statistics. Based on established judgment criteria, the total program implementation was examined and interpreted as a mix of the availability, compliance, and acceptability dimensions. To investigate the factors associated with ICCM acceptance, a binary logistic regression analysis was performed. During bivariable analysis, variables with p-values less than 0.25 were included in multivariable analysis. Finally, variables having a p-value less than 0.05 and an adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) were judged statistically significant. Qualitative data were collected recorded, transcribed into Amharic, then translated into English and finally coded and thematically analyzed.

Judgment matrix analysis

The weighted values of availability, compliance, and acceptability dimensions were 35, 40, and 25 based on the stakeholder and investigator agreement on each indicator, respectively. The judgment parameters for each dimension and the overall implementation of the program were categorized as poor (< 60%), fair (60–74.9%), good (75-84.9%), and very good (85–100%).

Availability of resources

A total of 26 HEWs were assigned within the fourteen health posts, and 72.7% of them were trained on ICCM to manage common childhood illnesses in under-five children. However, the training was given before four years, and they didn’t get even refreshment training about ICCM. The KII responses also supported that the shortage of HEWs at the HPs was the problem in implementing the program properly.

I am the only HEW in this health post and I have not been trained on ICCM program. So, this may compromise the quality of service and client satisfaction.(25 years old HEW with two years’ experience)

All observed health posts had ICCM registration books, monthly report and referral formats, functional thermometer, weighting scale and MUAC tape meter. However, timer and resuscitation bag was not available in all HPs. Most of the key informant finding showed that, in all HPs there was no shortage of guideline, registration book and recording tool; however, there was no OTP card in some health posts.

“Guideline, ICCM registration book for 2–59 months of age, and other different recording and reporting formats and booklet charts are available since September/2016. However, OTP card is not available in most HPs.”. (A 30 years male health center director)

Only one-fifth (21%) of HPs had a clean water source for drinking and washing of equipment. Most of Key-informant interview findings showed that the availability of infrastructures like water was not available in most HPs. Poor linkage between HPs, HCs, town health department, and local Kebele administer were the reason for unavailability.

Since there is no water for hand washing, or drinking, we obligated to bring water from our home for daily consumptions. This increases the burden for us in our daily activity. (35 years old HEW)

Most medicines, such as anti-malaria drugs with RDT, Quartem, Albendazole, Amoxicillin, vitamin A capsules, ORS, and gloves, were available in all the health posts. Drugs like zinc, paracetamol, TTC eye ointment, and folic acid were available in some HPs. However, cotrimoxazole and vitamin K capsules were stocked-out in all health posts for the last six months. The key informant also revealed that: “Vitamin K was not available starting from the beginning of this program and Cotrimoxazole was not available for the past one year and they told us they would avail it soon but still not availed. Some essential ICCM drugs like anti malaria drugs, De-worming, Amoxicillin, vitamin A capsules, ORS and medical supplies were also not available in HCs regularly.”(28 years’ Female PHCU focal)

The overall availability of resources for ICCM implementation was 84.2% which was good based on our presetting judgment parameter (Table 1 ).

Health extension worker’s compliance

From the 42 patient-provider interactions, we found that 85.7%, 71.4%, 76.2%, and 95.2% of the children were checked for body temperature, weight, general danger signs, and immunization status respectively. Out of total (42) observation, 33(78.6%) of sick children were classified for their nutritional status. During observation time 29 (69.1%) of caregivers were counseled by HEWs on food, fluid and when to return back and 35 (83.3%) of children were appointed for next follow-up visit. Key informant interviews also affirmed that;

“Most of our health extension workers were trained on ICCM program guidelines but still there are problems on assessment classification and treatment of disease based on guidelines and standards this is mainly due to lack refreshment training on the program and lack of continuous supportive supervision from the respective body.” (27years’ Male health center head)

From 10 clients classified as having severe pneumonia cases, all of them were referred to a health center (with pre-referral treatment), and from those 57 pneumonia cases, 50 (87.7%) were treated at the HP with amoxicillin or cotrimoxazole. All children with severe diarrhea, very severe disease, and severe complicated malnutrition cases were referred to health centers with a pre-referral treatment for severe dehydration, very severe febrile disease, and severe complicated malnutrition, respectively. From those with some dehydration and no dehydration cases, (82.4%) and (86.8%) were treated at the HPs for some dehydration (ORS; plan B) and for no dehydration (ORS; plan A), respectively. Moreover, zinc sulfate was prescribed for 63 (90%) of under-five children with some dehydration or no dehydration. From 26 malaria cases and 32 severe uncomplicated malnutrition and moderate acute malnutrition cases, 20 (76.9%) and 25 (78.1%) were treated at the HPs, respectively. Of the total reviewed documents, 56 (93.3%), 66 (94.3%), 38 (84.4%), and 25 (78.1%) of them were given a follow-up date for pneumonia, diarrhea, malaria, and malnutrition, respectively.

Supportive supervision and performance review meetings were conducted only in 10 (71.4%) HPs, but all (100%) HPs sent timely reports to the next supervisory body.

Most of the key informants’ interview findings showed that supportive supervision was not conducted regularly and for all HPs.

I had mentored and supervised by supportive supervision teams who came to our health post at different times from health center, town health office and zonal health department. I received this integrated supervision from town health office irregularly, but every month from catchment health center and last integrated supportive supervision from HC was on January. The problem is the supervision was conducted for all programs.(32 years’ old and nine years experienced female HEW)

Moreover, the result showed that there was poor compliance of HEWs for the program mainly due to weak supportive supervision system of managerial and technical health workers. It was also supported by key informants as:

We conducted supportive supervision and performance review meeting at different time, but still there was not regular and not addressed all HPs. In addition to this the supervision and review meeting was conducted as integration of ICCM program with other services. The other problem is that most of the time we didn’t used checklist during supportive supervision. (Mid 30 years old male HC director)

Based on our observation and ICCM document review, 83.1% of the HEWs were complied with the ICCM guidelines and judged as fair (Table 2 ).

Acceptability of ICCM program

Sociodemographic and obstetric characteristics of participants.

A total of 484 study participants responded to the interviewer-administered questionnaire with a response rate of 95.3%. The mean age of study participants was 30.7 (SD ± 5.5) years. Of the total caregivers, the majority (38.6%) were categorized under the age group of 26–30 years. Among the total respondents, 89.3% were married, and regarding religion, the majorities (84.5%) were Orthodox Christian followers. Regarding educational status, over half of caregivers (52.1%) were illiterate (unable to read or write). Nearly two-thirds of the caregivers (62.6%) were housewives (Table 3 ).

All the caregivers came to the health post on foot, and most of them 418 (86.4%) arrived within one hour. The majority of 452 (93.4%) caregivers responded that the waiting time to get the service was less than 30 min. Caregivers who got the prescribed drugs at the health post were 409 (84.5%). Most of the respondents, 429 (88.6%) and 438 (90.5%), received counseling services on providing extra fluid and feeding for their sick child and were given a follow-up date.

Most 298 (61.6%) of the caregivers were satisfied with the convenience of the working hours of HPs, and more than three-fourths (80.8%) were satisfied with the counseling services they received. Most of the respondents, 366 (75.6%), were satisfied with the appropriateness of waiting time and 431 (89%) with the appropriateness of consultation time. The majority (448 (92.6%) of caregivers were satisfied with the way of communicating with HEWs, and 269 (55.6%) were satisfied with the knowledge and competence of HEWs. Nearly half of the caregivers (240, or 49.6%) were satisfied with the availability of drugs at health posts.

The overall acceptability of the ICCM program was 75.3%, which was judged as good. A low proportion of acceptability was measured on the cleanliness of the health posts, the appropriateness of the waiting area, and the competence and knowledge of the HEWs. On the other hand, high proportion of acceptability was measured on appropriateness of waiting time, way of communication with HEWs, and the availability of drugs (Table 4 ).

Factors associated with acceptability of ICCM program

In the final multivariable logistic regression analysis, educational status of caregivers, availability of prescribed drugs, time to arrive, and waiting time were factors significantly associated with the satisfaction of caregivers with the ICCM program.

Accordingly, the odds of caregivers with primary education, secondary education, and college and above were 73% (AOR = 0.27, 95% CI: 0.11–0.52), 84% (AOR = 0.16, 95% CI: 0.07–0.39), and 92% (AOR = 0.08, 95% CI: 0.07–0.40) less likely to accept the program as compared to mothers or caregivers who were not able to read and write, respectively. The odds of caregivers or mothers who received prescribed drugs were 2.17 times more likely to accept the program as compared to their counters (AOR = 2.17, 95% CI: 1.14–4.10). The odds of caregivers or mothers who waited for services for less than 30 min were 2.8 times more likely to accept the program as compared to those who waited for more than 30 min (AOR = 2.80, 95% CI: 1.16–6.79). Moreover, the odds of caregivers/mothers who traveled an hour or less for service were 3.8 times more likely to accept the ICCM program as compared to their counters (AOR = 3.82, 95% CI:1.99–7.35) (Table 5 ).

Overall ICCM program implementation and judgment

The implementation of the ICCM program in Gondar city administration was measured in terms of availability (84.2%), compliance (83.1%), and acceptability (75.3%) dimensions. In the availability dimension, amoxicillin, antimalarial drugs, albendazole, Vit. A, and ORS were available in all health posts, but only six HPs had Ready-to-Use Therapeutic Feedings, three HPs had ORT Corners, and none of the HPs had functional timers. In all health posts, the health extension workers asked the chief to complain, correctly assessed for pneumonia, diarrhea, malaria, and malnutrition, and sent reports based on the national schedule. However, only 70% of caretakers counseled about food, fluids, and when to return, 66% and 76% of the sick children were checked for anemia and other danger signs, respectively. The acceptability level of the program by caretakers and caretakers’/mothers’ educational status, waiting time to get the service and travel time ICCM sites were the factors affecting its acceptability. The overall ICCM program in Gondar city administration was 81.5% and judged as good (Fig. 2 ).

Overall ICCM program implementation and the evaluation dimensions in Gondar city administration, 2022

The implementation status of ICCM was judged by using three dimensions including availability, compliance and acceptability of the program. The judgment cut of points was determined during evaluability assessment (EA) along with the stakeholders. As a result, we found that the overall implementation status of ICCM program was good as per the presetting judgment parameter. Availability of resources for the program implementation, compliance of HEWs to the treatment guideline and acceptability of the program services by users were also judged as good as per the judgment parameter.

This evaluation showed that most medications, equipment and recording and reporting materials available. This finding was comparable with the standard ICCM treatment guide line [ 10 ]. On the other hand trained health care providers, some medications like Zink, Paracetamol and TTC eye ointment, folic acid and syringes were not found in some HPs. However the finding was higher than the study conducted in SNNPR on selected health posts [ 33 ] and a study conducted in Soro district, southern Ethiopia [ 24 ]. The possible reason might be due to low interruption of drugs at town health office or regional health department stores, regular supplies of essential drugs and good supply management and distribution of drug from health centers to health post.

The result of this evaluation showed that only one fourth of health posts had functional ORT Corner which was lower compared to the study conducted in SNNPR [ 34 ]. This might be due poor coverage of functional pipe water in the kebeles and the installation was not set at the beginning of health post construction as reported from one of ICCM program coordinator.

Compliance of HEWs to the treatment guidelines in this evaluation was higher than the study done in southern Ethiopia (65.6%) [ 24 ]. This might be due to availability of essential drugs educational level of HEWs and good utilization of ICCM guideline and chart booklet by HEWs. The observations showed most of the sick children were assessed for danger sign, weight, and temperature respectively. This finding is lower than the study conducted in Rwanda [ 35 ]. This difference might be due to lack of refreshment training and regular supportive supervision for HEWs. This also higher compared to the study done in three regions of Ethiopia indicates that 88%, 92% and 93% of children classified as per standard for Pneumonia, diarrhea and malaria respectively [ 36 ]. The reason for this difference may be due to the presence of medical equipment and supplies including RDT kit for malaria, and good educational level of HEWs.

Moreover most HPs received supportive supervision and performance review meeting was conducted and all of them send reports timely to next level. The finding of this evaluation was lower than the study conducted on implementation evaluation of ICCM program southern Ethiopia [ 24 ] and study done in three regions of Ethiopia (Amhara, Tigray and SNNPR) [ 37 ]. This difference might be due sample size variation.

The overall acceptability of the ICCM program was less than the presetting judgment parameter but slightly higher compared to the study in southern Ethiopia [ 24 ]. This might be due to presence of essential drugs for treating children, reasonable waiting and counseling time provided by HEWs, and smooth communication between HEWs and caregivers. In contrast, this was lower than similar studies conducted in Wakiso district, Uganda [ 38 ]. The reason for this might be due to contextual difference between the two countries, inappropriate waiting area to receive the service and poor cleanness of the HPs in our study area. Low acceptability of caregivers to ICCM service was observed in the appropriateness of waiting area, availability of drugs, cleanness of health post, and competence of HEWs while high level of caregiver’s acceptability was consultation time, counseling service they received, communication with HEWs, treatment given for their sick children and interest to return back for ICCM service.

Caregivers who achieved primary, secondary, and college and above were more likely accept the program services than those who were illiterate. This may more educated mothers know about their child health condition and expect quality service from healthcare providers which is more likely reduce the acceptability of the service. The finding is congruent with a study done on implementation evaluation of ICCM program in southern Ethiopia [ 24 ]. However, inconsistent with a study conducted in wakiso district in Uganda [ 38 ]. The possible reason for this might be due to contextual differences between the two countries. The ICCM program acceptability was high in caregivers who received all prescribed drugs than those did not. Caregivers those waited less than 30 min for service were more accepted ICCM services compared to those more than 30 minutes’ waiting time. This finding is similar compared with the study conducted on implementation evaluation of ICCM program in southern Ethiopia [ 24 ]. In contrary, the result was incongruent with a survey result conducted by Ethiopian public health institute in all regions and two administrative cities of Ethiopia [ 39 ]. This variation might be due to smaller sample size in our study the previous one. Moreover, caregivers who traveled to HPs less than 60 min were more likely accepted the program than who traveled more and the finding was similar with the study finding in Jimma zone [ 40 ].

Strengths and limitations

This evaluation used three evaluation dimensions, mixed method and different data sources that would enhance the reliability and credibility of the findings. However, the study might have limitations like social desirability bias, recall bias and Hawthorne effect.

The implementation of the ICCM program in Gondar city administration was measured in terms of availability (84.2%), compliance (83.1%), and acceptability (75.3%) dimensions. In the availability dimension, amoxicillin, antimalarial drugs, albendazole, Vit. A, and ORS were available in all health posts, but only six HPs had Ready-to-Use Therapeutic Feedings, three HPs had ORT Corners, and none of the HPs had functional timers.

This evaluation assessed the implementation status of the ICCM program, focusing mainly on availability, compliance, and acceptability dimensions. The overall implementation status of the program was judged as good. The availability dimension is compromised due to stock-outs of chloroquine syrup, cotrimoxazole, and vitamin K and the inaccessibility of clean water supply in some health posts. Educational statuses of caregivers, availability of prescribed drugs at the HPs, time to arrive to HPs, and waiting time to receive the service were the factors associated with the acceptability of the ICCM program.

Therefore, continuous supportive supervision for health facilities, and refreshment training for HEW’s to maximize compliance are recommended. Materials and supplies shall be delivered directly to the health centers or health posts to solve the transportation problem. HEWs shall document the assessment findings and the services provided using the registration format to identify their gaps, limitations, and better performances. The health facilities and local administrations should construct clean water sources for health facilities. Furthermore, we recommend for future researchers and program evaluators to conduct longitudinal studies to know the causal relationship of the program interventions and the outcomes.

Data availability

Data will be available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey

Health Center/Health Facility

Health Extension Program

Health Extension Workers

Health Post

Health Sector Development Plan

Integrated Community Case Management of Common Childhood Illnesses

Information Communication and Education

Integrated Family Health Program

Integrated Management of Neonatal and Childhood Illness

Integrated Supportive Supervision

Maternal and Child Health

Mid Upper Arm Circumference

Non-Government Organization

Oral Rehydration Salts

Outpatient Therapeutic program

Primary health care unit

Rapid Diagnostics Test

Ready to Use Therapeutic Foods

Sever Acute Malnutrition

South Nation Nationalities People Region

United Nations International Child Emergency Fund

World Health Organization

Brenner JL, Barigye C, Maling S, Kabakyenga J, Nettel-Aguirre A, Buchner D, et al. Where there is no doctor: can volunteer community health workers in rural Uganda provide integrated community case management? Afr Health Sci. 2017;17(1):237–46.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Mubiru D, Byabasheija R, Bwanika JB, Meier JE, Magumba G, Kaggwa FM, et al. Evaluation of integrated community case management in eight districts of Central Uganda. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(8):e0134767.

Samuel S, Arba A. Utilization of integrated community case management service and associated factors among mothers/caregivers who have sick eligible children in southern Ethiopia. Risk Manage Healthc Policy. 2021;14:431.

Article Google Scholar

Kavle JA, Pacqué M, Dalglish S, Mbombeshayi E, Anzolo J, Mirindi J, et al. Strengthening nutrition services within integrated community case management (iCCM) of childhood illnesses in the Democratic Republic of Congo: evidence to guide implementation. Matern Child Nutr. 2019;15:e12725.

Miller NP, Amouzou A, Tafesse M, Hazel E, Legesse H, Degefie T, et al. Integrated community case management of childhood illness in Ethiopia: implementation strength and quality of care. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;91(2):424.

WHO. Annual report 2016: Partnership and policy engagement. World Health Organization, 2017.

Banteyerga H. Ethiopia’s health extension program: improving health through community involvement. MEDICC Rev. 2011;13:46–9.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Wang H, Tesfaye R, Ramana NV, Chekagn G. CT. Ethiopia health extension program: an institutionalized community approach for universal health coverage. The World Bank; 2016.

Donnelly J. Ethiopia gears up for more major health reforms. Lancet. 2011;377(9781):1907–8.

Legesse H, Degefie T, Hiluf M, Sime K, Tesfaye C, Abebe H, et al. National scale-up of integrated community case management in rural Ethiopia: implementation and early lessons learned. Ethiop Med J. 2014;52(Suppl 3):15–26.

Google Scholar

Miller NP, Amouzou A, Hazel E, Legesse H, Degefie T, Tafesse M et al. Assessment of the impact of quality improvement interventions on the quality of sick child care provided by Health Extension workers in Ethiopia. J Global Health. 2016;6(2).

Oliver K, Young M, Oliphant N, Diaz T, Kim JJNYU. Review of systematic challenges to the scale-up of integrated community case management. Emerging lessons & recommendations from the catalytic initiative (CI/IHSS); 2012.

FMoH E. Health Sector Transformation Plan 2015: https://www.slideshare.net . Accessed 12 Jan 2022.

McGorman L, Marsh DR, Guenther T, Gilroy K, Barat LM, Hammamy D, et al. A health systems approach to integrated community case management of childhood illness: methods and tools. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2012;87(5 Suppl):69.

Young M, Wolfheim C, Marsh DR, Hammamy D. World Health Organization/United Nations Children’s Fund joint statement on integrated community case management: an equity-focused strategy to improve access to essential treatment services for children. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 2012;87(5 Suppl):6.

Ezbakhe F, Pérez-Foguet A. Child mortality levels and trends. Demographic Research.2020;43:1263-96.

UNICEF, Ending child deaths from pneumonia and diarrhoea. 2016 report: Available at https://data.unicef.org. accessed 13 Jan 2022.

UNITED NATIONS, The Millinium Development Goals Report 2015: Available at https://www.un.org.Accessed 12 Jan 2022

Bent W, Beyene W, Adamu A. Factors Affecting Implementation of Integrated Community Case Management Of Childhood Illness In South West Shoa Zone, Central Ethiopia 2015.

Abdosh B. The quality of hospital services in eastern Ethiopia: Patient’s perspective.The Ethiopian Journal of Health Development. 2006;20(3).

Young M, Wolfheim C, Marsh DR, Hammamy DJTAjotm, hygiene. World Health Organization/United Nations Children’s Fund joint statement on integrated community case management: an equity-focused strategy to improve access to essential treatment services for children.2012;87(5_Suppl):6–10.

Obrist B, Iteba N, Lengeler C, Makemba A, Mshana C, Nathan R, et al. Access to health care in contexts of livelihood insecurity: a framework for analysis and action.PLoS medicine. 2007;4(10):e308.

Carroll C, Patterson M, Wood S, Booth A, Rick J, Balain S. A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implementation science. 2007;2(1):1–9.

Dunalo S, Tadesse B, Abraham G. Implementation Evaluation of Integrated Community Case Management of Common Childhood Illness (ICCM) Program in Soro Woreda, Hadiya Zone Southern Ethiopia 2017 2017.

Asefa G, Atnafu A, Dellie E, Gebremedhin T, Aschalew AY, Tsehay CT. Health System Responsiveness for HIV/AIDS Treatment and Care Services in Shewarobit, North Shewa Zone, Ethiopia. Patient preference and adherence. 2021;15:581.

Gebremedhin T, Daka DW, Alemayehu YK, Yitbarek K, Debie A. Process evaluation of the community-based newborn care program implementation in Geze Gofa district,south Ethiopia: a case study evaluation design. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2019;19(1):1–13.

Pitaloka DS, Rizal A. Patient’s satisfaction in antenatal clinic hospital Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. Jurnal Kesihatan Masyarakat (Malaysia). 2006;12(1):1–10.

Teshale G, Debie A, Dellie E, Gebremedhin T. Evaluation of the outpatient therapeutic program for severe acute malnourished children aged 6–59 months implementation in Dehana District, Northern Ethiopia: a mixed-methods evaluation. BMC pediatrics. 2022;22(1):1–13.

Mason E. WHO’s strategy on Integrated Management of Childhood Illness. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2006;84(8):595.

Shaw B, Amouzou A, Miller NP, Tafesse M, Bryce J, Surkan PJ. Access to integrated community case management of childhood illnesses services in rural Ethiopia: a qualitative study of the perspectives and experiences of caregivers. Health policy and planning.2016;31(5):656 – 66.

Organization WH. Annual report 2016: Partnership and policy engagement. World Health Organization, 2017.

Berhanu D, Avan B. Community Based Newborn Care Baseline Survey Report Ethiopia,October 2014.

Save the children, Enhancing Ethiopia’s Health Extension Package in the Southern Nations and Nationalities People’s Region (SNNPR) Shebedino and Lanfero Woredas report.Hawassa;. 2012: Avalable at https://ethiopia.savethechildren.net

Kolbe AR, Muggah R, Hutson RA, James L, Puccio M, Trzcinski E, et al. Assessing Needs After the Quake: Preliminary Findings from a Randomized Survey of Port-au-Prince Households. University of Michigan/Small Arms Survey: Available at https://deepbluelibumichedu PDF. 2010.

Teferi E, Teno D, Ali I, Alemu H, Bulto T. Quality and use of IMNCI services at health center under-five clinics after introduction of integrated community-based case management (ICCM) in three regions of Ethiopia. Ethiopian Medical Journal. 2014;52(Suppl 3):91 – 8.

Last 10 Km project, Integrated Community Case Management (iCCM) Survey report in Amhara, SNNP, and Tigray Regions, 2017: Avaialable at https://l10k.jsi.com

Tumuhamye N, Rutebemberwa E, Kwesiga D, Bagonza J, Mukose A. Client satisfaction with integrated community case management program in Wakiso District, Uganda, October 2012: A cross sectional survey. Health scrip org. 2013;2013.

EPHI. Ethiopia service provision assessment plus survey 2014 report: available at http://repository.iifphc.org

Gintamo B. EY, Assefa Y. Implementation Evaluation of IMNCI Program at Public Health Centers of Soro District, Hadiya Zone, Southern Ethiopia,. 2017: Available at https://repository.ju.edu.et

Download references

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to University of Gondar and Gondar town health office for its welcoming approaches. We would also like to thank all of the study participants of this evaluation for their information and commitment. Our appreciation also goes to the data collectors and supervisors for their unreserved contribution.

No funding is secured for this evaluation study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Metema District Health office, Gondar, Ethiopia

Mekides Geta

Department of Health Systems and Policy, Institute of Public Health, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Gondar, P.O. Box 196, Gondar, Ethiopia

Geta Asrade Alemayehu, Wubshet Debebe Negash, Tadele Biresaw Belachew, Chalie Tadie Tsehay & Getachew Teshale

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors contributed to the preparation of the manuscript. M.G. conceived and designed the evaluation and performed the analysis then T.B.B., W.D.N., G.A.A., C.T.T. and G.T. revised the analysis. G.T. prepared the manuscript and all the authors revised and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Getachew Teshale .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethical approval was obtained from Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Institute of Public Health, College of Medicine and Health sciences, University of Gondar (Ref No/IPH/1482/2013). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declared that they have no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Geta, M., Alemayehu, G.A., Negash, W.D. et al. Evaluation of integrated community case management of the common childhood illness program in Gondar city, northwest Ethiopia: a case study evaluation design. BMC Pediatr 24 , 310 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-024-04785-0

Download citation

Received : 20 February 2024

Accepted : 22 April 2024

Published : 09 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-024-04785-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.