December 21, 2017

Norman Rockwell

Carlos Bulosan’s ‘Freedom from Want’

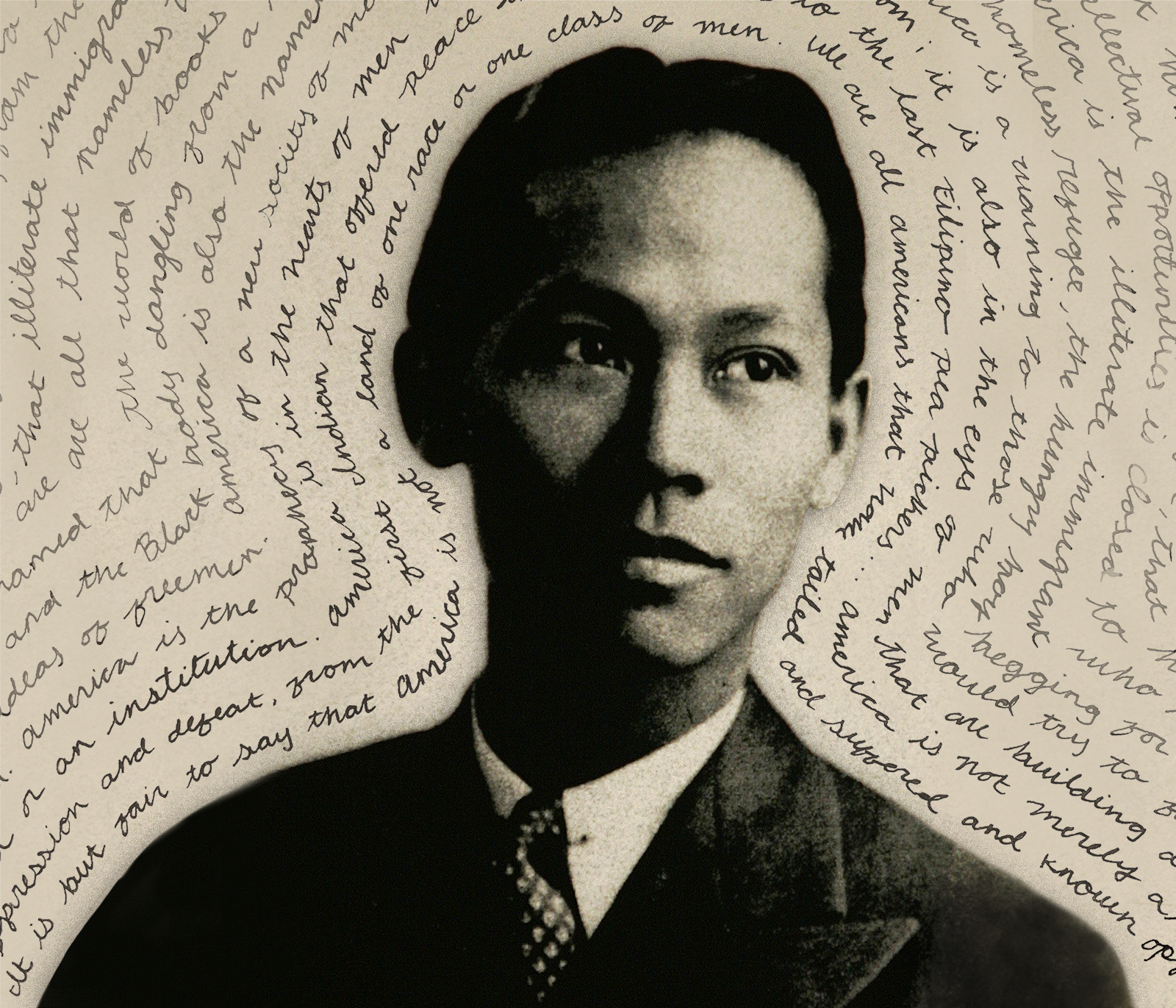

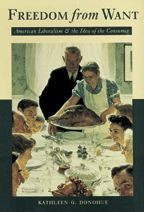

In 1943, the Post commissioned Filipino novelist and poet Carlos Bulosan to craft this essay to accompany Norman Rockwell’s ‘Freedom from Want.’

Carlos Bulosan

- Share on Facebook (opens new window)

- Share on Twitter (opens new window)

- Share on Pinterest (opens new window)

Weekly Newsletter

The best of The Saturday Evening Post in your inbox!

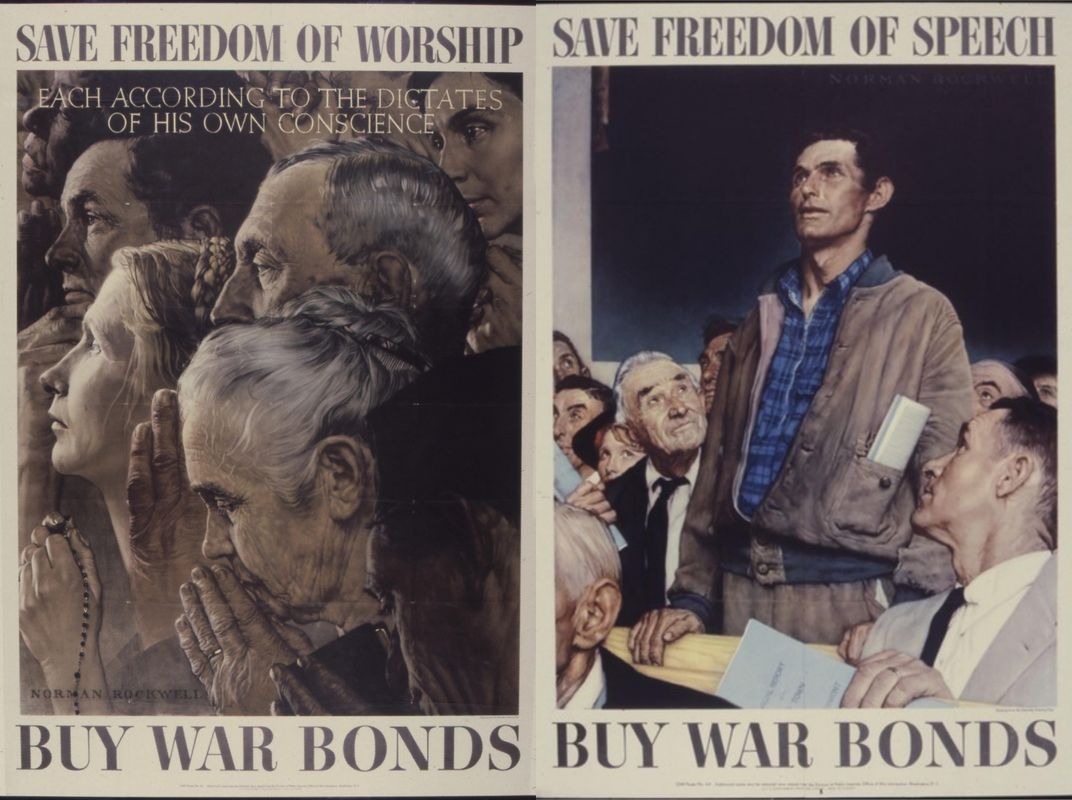

In 1943, the Post commissioned four writers to craft an essay to accompany each of Norman Rockwell’s Four Freedoms paintings, which had quickly come to represent America’s moral imperative during World War II. You can read the other three essays here .

Freedom from Want

Originally published March 6, 1943

Subscribe and get unlimited access to our online magazine archive.

If you want to know what we are, look upon the farms or upon the hard pavements of the city. You usually see us working or waiting for work, and you think you know us, but our outward guise is more deceptive than our history.

Our history has many strands of fear and hope, that snarl and converge at several points in time and space. We clear the forest and the mountains of the land. We cross the river and the wind. We harness wild beast and living steel. We celebrate labor, wisdom, peace of the soul.

When our crops are burned or plowed under, we are angry and confused. Sometimes we ask if this is the real America. Sometimes we watch our long shadows and doubt the future. But we have learned to emulate our ideals from these trials. We know there were men who came and stayed to build America. We know they came because there is something in America that they needed, and which needed them.

We march on, though sometimes strange moods fill our children. Our march toward security and peace is the march of freedom — the freedom that we should like to become a living part of. It is the dignity of the individual to live in a society of free men, where the spirit of understanding and belief exist; of understanding that all men are equal; that all men, whatever their color, race, religion or estate, should be given equal opportunity to serve themselves and each other according to their needs and abilities.

But we are not really free unless we use what we produce. So long as the fruit of our labor is denied us, so long will want manifest itself in a world of slaves. It is only when we have plenty to eat — plenty of everything — that we begin to understand what freedom means. To us, freedom is not an intangible thing. When we have enough to eat, then we are healthy enough to enjoy what we eat. Then we have the time and ability to read and think and discuss things. Then we are not merely living but also becoming a creative part of life. It is only then that we become a growing part of democracy.

We do not take democracy for granted. We feel it grow in our working together — many millions of us working toward a common purpose. If it took us several decades of sacrifices to arrive at this faith, it is because it took us that long to know what part of America is ours.

Our faith has been shaken many times, and now it is put to question. Our faith is a living thing, and it can be crippled or chained. It can be killed by denying us enough food or clothing, by blasting away our personalities and keeping us in constant fear. Unless we are properly prepared, the powers of darkness will have good reason to catch us unaware and trample our lives.

The totalitarian nations hate democracy. They hate us because we ask for a definite guaranty of freedom of religion, freedom of expression, and freedom from fear and want. Our challenge to tyranny is the depth of our faith in a democracy worth defending. Although they spread lies about us, the way of life we cherish is not dead. The American Dream is only hidden away, and it will push its way up and grow again.

We have moved down the years steadily toward the practice of democracy. We become animate in the growth of Kansas wheat or in the ring of Mississippi rain. We tremble in the strong winds of the Great Lakes. We cut timbers in Oregon just as the wild flowers blossom in Maine. We are multitudes in Pennsylvania mines, in Alaskan canneries. We are millions from Puget Sound to Florida. In violent factories, crowded tenements, teeming cities. Our numbers increase as the war revolves into years and increases hunger, disease, death, and fear.

But sometimes we wonder if we are really a part of America. We recognize the mainsprings of American democracy in our right to form unions and bargain through them collectively, our opportunity to sell our products at reasonable prices, and the privilege of our children to attend schools where they learn the truth about the world in which they live. We also recognize the forces which have been trying to falsify American history — the forces which drive many Americans to a corner of compromise with those who would distort the ideals of men that died for freedom.

Sometimes we walk across the land looking for something to hold on to. We cannot believe that the resources of this country are exhausted. Even when we see our children suffer humiliations, we cannot believe that America has no more place for us. We realize that what is wrong is not in our system of government, but in the ideals which were blasted away by a materialistic age. We know that we can truly find and identify ourselves with a living tradition if we walk proudly in familiar streets. It is a great honor to walk on the American earth.

If you want to know what we are, look at the men reading books, searching in the dark pages of history for the lost word, the key to the mystery of living peace. We are factory hands, field hands, mill hands, searching, building, and molding structures. We are doctors, scientists, chemists, discovering and eliminating disease, hunger, and antagonism. We are soldiers, Navy men, citizens, guarding the imperishable dream of our fathers to live in freedom. We are the living dream of dead men. We are the living spirit of free men.

Everywhere we are on the march, passing through darkness into a sphere of economic peace. When we have the freedom to think and discuss things without fear, when peace and security are assured, when the futures of our children are ensured — then we have resurrected and cultivated the early beginnings of democracy. And America lives and becomes a growing part of our aspirations again.

We have been marching for the last 150 years. We sacrifice our individual liberties, and sometimes we fail and suffer. Sometimes we divide into separate groups and our methods conflict, though we all aim at one common goal. The significant thing is that we march on without turning back. What we want is peace, not violence. We know that we thrive and prosper only in peace.

We are bleeding where clubs are smashing heads, where bayonets are gleaming. We are fighting where the bullet is crashing upon armorless citizens, where the tear gas is choking unprotected children. Under the lynch trees, amidst hysterical mobs. Where the prisoner is beaten to confess a crime he did not commit. Where the honest man is hanged because he told the truth.

We are the sufferers who suffer for natural love of man for another man, who commemorate the humanities of every man. We are the creators of abundance.

We are the desires of anonymous men. We are the subways of suffering, the well of dignities. We are the living testament of a flowering race.

But our march to freedom is not complete unless want is annihilated. The America we hope to see is not merely a physical but also a spiritual and an intellectual world. We are the mirror of what America is. If America wants us to be living and free, then we must be living and free. If we fail, then America fails.

What do we want? We want complete security and peace. We want to share the promises and fruits of American life. We want to be free from fear and hunger.

If you want to know what we are — we are marching!

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Recommended

Apr 25, 2024

Art , Cover Art , Norman Rockwell

Rockwell Files: A Sporting Chance

Jeff Nilsson

Apr 15, 2024

Archives , Art , Cover Art , Norman Rockwell

Rockwell Files: In Search of the Lost Deduction

Feb 05, 2024

Archives , Cover Art , Norman Rockwell

Rockwell Files: “Those Were Different Times”

it was kind of back then because nobody writtes like that today.

How much is the ” Freedom from want” year published 1992 off set Lithograph 281 / 1000 arenworth now?

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- 1865-1925: Hunger in the Industrial City

- 1929-1940: America in Crisis and Recovery

- 1945-1965: WWII and the Paradoxes of the Postwar Era

- 1955-1980: The Fight for the Right for Food

- 1975-1996: The Unmaking of the Great Society

- 1997-Present: How It Is — And How It Should Be

- Museum Lobby

- The Wishing Tree

- The SNAP Café

- Terrace Restaurant

- Get Involved

- Book a Tour

- Leave your Wish

- Patron Program

- Educational Curriculum

- The Hunger Museum

- About MAZON

- In the News

Carlos Bulosan, “Freedom From Want”

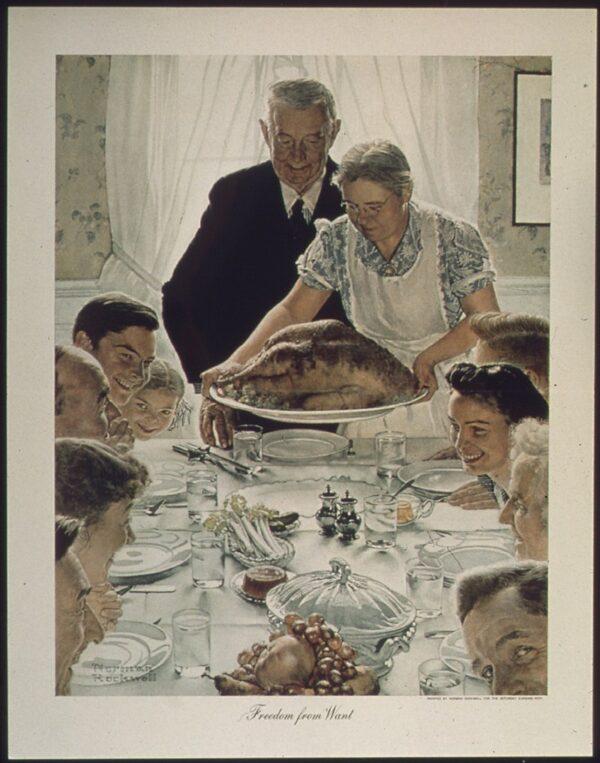

When Norman Rockwell’s famous painting ran in The Saturday Evening Post , it was accompanied by an essay written by Carlos Bulosan, a Filipino American migrant worker. His essay about labor, farm life, and hunger offers a stunning juxtaposition against Rockwell’s imagining of a white, middle-class family’s holiday feast.

We have been marching for the last 150 years. We sacrifice our individual liberties, and sometimes we fail and suffer. Sometimes we divide into separate groups and our methods conflict, though we all aim at one common goal. The significant thing is that we march on without turning back. What we want is peace, not violence. We know that we thrive and prosper only in peace.

We are bleeding where clubs are smashing heads, where bayonets are gleaming. We are fighting where the bullet is crashing upon armorless citizens, where the tear gas is choking unprotected children. Under the lynch trees, amidst hysterical mobs. Where the prisoner is beaten to confess a crime he did not commit. Where the honest man is hanged because he told the truth.

We are the sufferers who suffer for natural love of man for another man, who commemorate the humanities of every man. We are the creators of abundance.

We are the desires of anonymous men. We are the subways of suffering, the well of dignities. We are the living testament of a flowering race.

But our march to freedom is not complete unless want is annihilated. The America we hope to see is not merely a physical but also a spiritual and an intellectual world. We are the mirror of what America is. If America wants us to be living and free, then we must be living and free. If we fail, then America fails.

What do we want? We want complete security and peace. We want to share the promises and fruits of American life. We want to be free from fear and hunger.

— Carlos Bulosan, Filipino American migrant worker, 1943

- The Standard American Diet

Galleries & Exhibits

A complicated love story: Author Carlos Bulosan’s critique of America gave Filipino migrants a voice

“america is in the heart,” his definitive work, unveils hardships, heartaches and hopes of the first wave of filipino workers to arrive in the usa..

Illustration by Mara Corbett, USA TODAY NETWORK; Photo by AP

ALLOS, THE PROTAGONIST of Carlos Bulosan’s 1946 autobiographical novel, “America Is in the Heart,” wandered into a crowded pool hall one day shortly after arriving in Los Angeles.

A few minutes later, two police officers “darted into the place” and shot a young Filipino in the back. “The boy fell on his knees, face up, and expired,” Bulosan wrote.

The cops called an ambulance before dumping the youth’s lifeless body in the street, then “left hurriedly, untouched by their act, as though killing were a part of their day’s work.”

Allos was horrified and bewildered. He couldn’t believe what he witnessed. His fellow pinoys – young Filipino men recently arrived in America – stopped to consider the bloodshed for a brief moment before turning back to their games.

“They often shoot pinoys like that,” one said. “Without provocation. Sometimes when they have been drinking and they want to have fun, they come to our district and kick or beat the first Filipino they meet.”

When Allos asked why the Filipinos didn’t complain, he replied, “Complain? Are you kidding? Why, when we complain it always turns out that we attacked them! And they become more vicious, I’m telling you!”

Bulosan was a novelist, poet, labor activist and one of the manong, the young men in the first wave of Filipino migrants arriving from 1903 to 1934. His best-known essay, “Freedom from Want,” was published in The Saturday Evening Post in 1943 as a companion piece to Norman Rockwell's famous painting of the same name. It called on a nation at war to honor the values for which its young men were dying.

“America Is in the Heart” is Bulosan’s definitive work, a call to his fellow Americans, a cry for the rights of immigrants and workers by a Filipino who found his adopted country did not live up to the ideals American teachers had imparted onto a generation of colonial wards. The book documents how the earliest Filipino farmworkers were subjected to exploitation, systemic racism, brutal treatment by white law enforcement and anti-miscegenation laws that prevented them from starting families.

Bulosan’s work has been largely obscured by time and marginalized because of his association with liberals and communists in the labor movement. But his writing was important not just during his short life; it remains so as our nation grapples with the same questions and conflicts he wrote about: questions about race and workers’ rights, questions about whose histories deserve to be taught, questions about what it means to be an American.

“Bulosan is emblematic of the Filipino condition,” said Robyn Rodriguez, founder of the Bulosan Center for Filipino Studies at the University of California-Davis. “He was chronicling the early migration and settlement of Filipinos in a hostile society. One of the things that’s so striking about 'America Is in the Heart’ is this dissonance between his main characters, his protagonist and their undergoing this colonial education – America is this ideal, but all those dreams are shattered upon arriving here.

He interrogated it. That’s the mindset we need to see more … Bulosan saw America in all its beauty and all its faults.

“He saw it as his obligation to use his writing as a way of critiquing the structures of power,” Rodriguez said. “He knew there was power in the pen, and he deployed that power in all the ways he could.”

Jose Antonio Vargas, a Filipino American journalist, author and activist for undocumented immigrants, said Bulosan “speaks to the working-class experience in America.”

“That’s why documenting the manong experience is so incredibly important. We have to remind ourselves. … I have nieces and nephews for whom America is a given; and for Bulosan, it was an open question. His vision of America is very wide-eyed and open – it’s not this blind patriotism.

“He interrogated it. That’s the mindset we need to see more. … Bulosan saw America in all its beauty and all its faults.”

Is this the real America?

“If you want to know what we are, look at the men reading books, searching in the dark pages of history for the lost word, the key to the mystery of living peace. We are factory hands, field hands, mill hands, searching, building, and molding structures. We are doctors, scientists, chemists, discovering and eliminating disease, hunger, and antagonism. We are soldiers, Navy men, citizens, guarding the imperishable dream of our fathers to live in freedom. We are the living dream of dead men. We are the living spirit of free men.”

Bulosan was born around 1911 in Pangasinan, a province in the Philippines. He migrated to the USA in 1930.

In “America Is in the Heart,” Bulosan described a hardscrabble life with his father, a subsistence farmer, and his mother, who sold salted fish in a village market. His father was forced to sell off his land piece by piece, so without property to inherit and few prospects for employment, Bulosan joined an exodus of young, single Filipino men who boarded steamships for the USA and the territory of Hawaii.

After hundreds of years of Spanish annexation, the Philippines became an American colony in 1898, the spoils of victory after the Spanish-American War. Filipinos who fought against Spain alongside the United States saw the Americans’ demand for independence from England in 1776 as a template for the island nation’s self-rule.

Instead, another war – called an “insurrection” by the United States, as Filipinos fought to keep their own land – “would disrupt life across the provinces in ways that would reverberate over the generations and play a central role in the movement of Filipinas/os to the United States,” wrote Dawn Bohulano Mabalon in her 2013 book, “Little Manila Is in the Heart,” an answer to Bulosan’s book.

The United States sent all-Black regiments overseas, pitting Black soldiers against brown people. A policy of “benevolent assimilation” was adopted even as the Americans brutally fought Filipino guerrillas, calling them by racial slurs “n------” and “goo-goos . ” Filipinos’ education by American teachers sent abroad – modeled on the boarding school education of Native Americans at the time that separated them from their families, cultures and languages – snuffed the sparks of Filipino nationalism, culture, languages and traditions.

Bob Sampayan’s father was Bulosan’s first cousin. They grew up together in the Philippines and came to the USA in 1930 with high hopes to work, to be educated and to eventually return to their homeland, though Bulosan would never see the islands again.

“They wandered the streets and found what they thought was this beautiful park, and they slept there” upon their arrival, said Sampayan, who had a long career in law enforcement and became mayor of Vallejo, California. “When they woke up at dawn, they realized it was a cemetery. Then, they did what you’d do when you arrive in a new country: They went looking for work, for a place to stay. They worked at various jobs, anything they could do: working in restaurants, busing tables, washing dishes. They worked in agriculture, working the fields, traveling all over the Central Valley.”

Bulosan landed in Seattle, one of thousands of young, single Filipino men who traveled from the fish canneries of Alaska down to Washington, Oregon and California, following crop cycles. Very few Filipino women were allowed to migrate, as men were thought to be a stronger source of labor, and white lawmakers had no desire to see Filipinos bear children who would be U.S. citizens.

The workers were exploited at every turn: Predatory farm managers fired them on a whim, charged exorbitant rents for overcrowded, vermin-infested field houses and worked them to exhaustion. Filipinos were beaten, brutalized, even lynched for talking to white women or going into towns where they were unwelcome.

“I could not compromise my picture of America with the filthy bunkhouses in which we lived and the falling wooden houses in which the natives lived,” Bulosan wrote in his essay “My Education,” an undated work included in “On Becoming Filipino,” a collection of his poems, essays and short stories.

“I began to ask if this was the real America – and if it was, why did I come? I was sad and confused. But I believed in the other men before me who had come and stayed to discover America. I knew they came because there was something in America which needed them and which they needed. Yet I slowly began to doubt the promise that was America,” Bulosan wrote.

Black, brown, exploited

“...We sacrifice our individual liberties, and sometimes we fail and suffer. Sometimes we divide into separate groups and our methods conflict, though we all aim at one common goal. ...What we want is peace, not violence. We know that we thrive and prosper only in peace.”

“It’s important for Americans to understand the exploitation that happened in the building of this country,” said Patrick Rosal, a Filipino American poet, writer and professor at Rutgers University-Camden in New Jersey. “The emancipation of slaves and the rise of industrial farming occurred around the same time. They needed workers, but they needed them cheap, so they brought in immigrants.”

Black people freed after the Civil War sought better lives and higher wages, leaving the fields of the South to work in factories in the North; those who’d enslaved them resented paying those they considered less than fully human for labor that had once been free. Rapidly expanding farms in Hawaii, California, Washington and Oregon needed cheap, easily exploitable labor.

“It was a direct result of white supremacy,” Rosal said, “globalizing it through the annexation of the Philippines and using Black soldiers to do it. They needed labor, but they also wondered, just who were these Filipinos? Are they immigrants or citizens? They aren’t Black. But they aren’t white, either.”

The emancipation of slaves and the rise of industrial farming occurred around the same time. They needed workers, but they needed them cheap, so they brought in immigrants.

In “America Is in the Heart,” Bulosan’s Allos described his first months in America as frightening, violent and humiliating.

Allos saw a fellow worker’s severed arm float past him at an Alaska fish cannery. He ran from a gun-wielding mob of white men after picking apples on a Washington farm; and found himself targeted by law enforcement for the color of his skin, the slant of his eyes and the accent in his speech.

“It was the worst life,” said Dillon Delvo, executive director of Little Manila Rising, a Stockton, California-based nonprofit that advocates for environmental justice and historic preservation.

Delvo’s father came to the USA in 1928, he said, “an 18-year-old man who left everything behind and came with this idea of creating the first Filipino American family.”

That dream would be long deferred; His father was 67 by the time Delvo was born.

“There are a lot of us who had really, really old dads,” said Delvo, 48, “and ... it wasn’t until much later that I found out there were laws preventing them from marrying.”

Filipino men initially were not seen as a threat, but as the Depression threw millions out of work, simmering resentments began to boil over, said James Zarsadiaz, director of the Yuchengco Philippine Studies Program at the University of San Francisco.

“In the 1920s and ’30s, you began to see more Filipinos getting involved with white women and vice versa,” he said. “And it’s not just about them having mixed-race children and interracial marriages, but also white working-class resentment about Filipinos taking their jobs, so there was an economic impetus.”

The manong “were not alone, though they were actively segregated from white society,” said Rodriguez, who is trying to preserve their history, traveling through the Central Valley to talk with farmworkers. “They lived very rich lives with each other.”

Writing for their lives

“We are bleeding where clubs are smashing heads, where bayonets are gleaming. We are fighting where the bullet is crashing upon armorless citizens, where the tear gas is choking unprotected children. Under the lynch trees, amidst hysterical mobs. Where the prisoner is beaten to confess a crime he did not commit. Where the honest man is hanged because he told the truth.”

In the 1930 s, Bulosan and other Filipinos, angered by the treatment of their fellow pinoys, as well as the Mexican, Native American and Black farmworkers they encountered, tried to organize them to fight for better conditions. The effort moved in fits and starts, and Bulosan fell ill with tuberculosis.

By 1937, Bulosan wound up in Los Angeles County Hospital, where he remained for two years. He spent the time there reading works by American, European and Filipino writers. Two white sisters, Sanora and Dorothy Babb, supplied him with books by Pablo Neruda, Karl Marx, Walt Whitman, George Bernard Shaw, Mahatma Gandhi, John Steinbeck and José Rizal, a Philippine nationalist who was executed by the Spanish for sedition in 1896.

Bulosan endured surgeries on a cancerous leg, to remove lesions from his lungs and to remove a kidney, leaving him frail and vulnerable for the rest of his life.

“One day, before I came to the hospital, I was talking to a Negro boy about race and prejudice and he asked, ‘But there isn’t any prejudice against the Filipino in this country, is there?’” Bulosan wrote to a friend in 1937. “When I told him some of my experiences he was surprised, believing that Negroes were the only persecuted race in America.

“We who know prejudice sometimes have a tendency to believe that we are the only ones discriminated against,” he continued. “There have been times when I have been sad and bitter and felt this way. Then I remember that there are thousands of people besides Filipinos who have had similar experiences – Negroes, Chinese, Japanese and even native-born whites. And I began to feel less alone, remembering those people and those few Americans I have known without a trace of prejudice.”

The Filipino Agricultural Laborers Association staged a strike in 1939, and after World War II, Bulosan helped organize cannery workers’ and asparagus pickers’ strikes along with Rudy Delvo, Claro Candelario, Chris Mensalvas and Larry Itliong, who would go on to lead the Delano grape strike/boycott of 1965-70 in California along with Philip Vera Cruz (a fellow Filipino), Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta.

“I met (Chavez), and one of the things he talked about was Carlos Bulosan and what Carlos tried to do in the 1930s and ’40s,” Sampayan recalled. “He was trying to get people to unionize but also to be part of mainstream America while also retaining their roots and culture and heritage.”

“Studying Bulosan is studying the history of work itself,” Rosal said. “There’s a difference between studying the tables and the statistics, and the stories: the exploitation, the way they lived, the danger that was a part of their everyday lives. ... Bulosan gives us things economics don’t: the stories of the workers and their interior lives.”

Even as Bulosan’s writing gained attention – besides The Saturday Evening Post, his work appeared in The New Republic and The New Yorker – he remained poor, sharing money with destitute friends, spending it, funneling it into the labor movement.

As the Cold War began, federal law enforcement targeted liberals who’d been active in the labor movement.

According to the University of Washington’s online archive of his work, Bulosan was under government surveillance as he worked with a cannery workers’ union. Five of its officers were targeted for deportation, and Bulosan was among those who fought successfully for them to remain – selling signed and numbered copies of his poems to benefit the defense fund.

Hospitalized again in 1952 for tuberculosis, Bulosan struggled with alcoholism and homelessness after he was released from the sanitarium a year later.

Bulosan died Sept. 11, 1956, “when, after a night of drinking with a labor lawyer who was a close friend, he wandered around the streets of Seattle,” Filipino poet and essayist E. San Juan wrote in the introduction to “On Becoming Filipino.” “At dawn he was found sprawled on the steps of the City Hall, ‘comatose and in an advanced stage of broncho-pneumonia.’

“He was less a victim of neurosis or despair than of cumulative suffering from years of privation and persecution,” San Juan concluded.

Bulosan “was victimized by McCarthyism at the height of the Cold War, when those who stood on the side of the labor movement were seen as threatening,” said Rodriguez, founder of the center that bears his name. “And that helped to make him disappear from the national narrative.”

Still, he and the other manongs persevered, she said. “There were some successes; they managed. And that’s important when you see what it really was to be a minority then, and what can happen when minoritized people come together.”

Preserving Filipino stories

“America is also the nameless foreigner, the homeless refugee, the hungry boy begging for a job and the Black body dangling from a tree. America is the illiterate immigrant who is ashamed that the world of books and intellectual opportunities is closed to him. We are all that nameless foreigner, that homeless refugee, that hungry boy, that illiterate immigrant and that lynched Black body. All of us, from the first Adams to the last Filipino, native born or alien, educated or illiterate — We are America!”

Many stories of the manong have been lost or overlooked for a variety of reasons: U.S. history curricula have long failed to tell the stories of marginalized people, people of color and non-European immigrants. The manongs’ bachelorhood meant many of them had no sons or daughters with whom to share their stories. Some who married wed white women and assimilated into American society, raising their children less as Filipinos and more as Americans.

“It’s very much a part of Filipinos to embrace full-on American assimilation,” said Zarsadiaz of the University of San Francisco. “They might want their children to be Catholic or to eat Filipino foods, but they teach them that they’re Americans first.”

That mindset is rooted in the colonial relationship the Philippines had with the United States and its influence on Filipino culture.

“To them, (English) is the language of modernity, and they embraced it,” Zarsadiaz said.

Zarsadiaz said some manong may not have shared their stories because they didn’t want to relive painful memories of the racism and brutality they faced.

“Some of that might be trauma, and some of it might be that way of, just do the damn thing and don’t talk about it,” he said. “It’s a very Filipino thing to just tough it out. There’s this stereotype of Filipino resilience; it took a long time for them to work their way to a decent life – not a rich life, but a decent life.”

The Bulosan Center faces an existential crisis, Rodriguez said: State funding is set to run out by the end of the 2021-22 academic year , and there is little support from the University of California-Davis .

Rodriguez plans to leave academia after 30 years and start a nonprofit to preserve the stories of the manong and the field workers, labor organizers and other Filipinos who came after them. She plans to work directly with community groups, free from the constraints of academia, frustrated and tired at having to fight the university for resources to support the Bulosan Center.

The nonprofit would be named for her son, Amado Khaya, an activist and community organizer who went to the Philippines to live and work with indigenous farmers on the island of Mindoro as they fought to preserve their land and way of life. He died in August 2020 from severe food poisoning.

Rodriguez has been traveling on her own through the Central Valley, collecting stories for the Central Valley Empowerment Alliance, which launched the Larry Itliong Resource Center in late October.

We have to tell the stories that were not told, but we also have to connect them to our present to sow the seeds of community among us — that’s why it matters to a wider audience.

Preserving Filipino stories has been an uphill struggle, she said.

There’s an urgency to the work: “Many of them are getting older, and there’s not a lot of physical evidence, no employment records or photographs. All we have is memories, and some of them are fading, and then what?”

“We have to tell the stories that were not told, but we also have to connect them to our present to sow the seeds of community among us – that’s why it matters to a wider audience,” said Rosal, whose latest collection of poetry, “The Last Thing,” examines life in the USA and the Philippines.

“These are American stories not being told – and that’s a detriment to America itself,” Delvo said.

The Digital Collections website will be partially or fully unavailable from May 12, 8pm - May 13, 2am PDT.--> The ability to search for and view database items will still be possible during that time.

- Advanced Search

Author, Poet, and Worker: The World of Carlos Bulosan

- Biography and Overview

- US Imperlialism in the Phillipines and at Home

- Immigration History, Union History

- Union History, Early Publications, Left Community

- World War II and Bulosan's Rise as a Writer

- Cold War Attacks on the Union, Bulosan's Work

- ILWU Local 37 - 1952 Yearbook

- Bulosan's Final Years in Seattle

- Bulosan's FBI File

- Cannery Worker Activism and Civil Rights

- Exhibit Bibliography

- Read in English

- Basahin sa Tagalog

Portraits with Cities Falling: World War II and Bulosan’s Newfound Fame

When the United States entered World War II, the popular image of Filipinos in the country took a turn. With the Philippines holding the line against Japan in the Pacific, Filipinos were suddenly cast as allies in the war effort. Hostility towards the Left also lessened somewhat, with the Soviet Union as an ally against fascism, and the U.S. Communist Party adopting new policies friendly to U.S. patriotism. Carlos Bulosan found himself working under new global conditions. As he titled a 1942 poem, he was writing “Portraits with Cities Falling.”

The wartime atmosphere occasioned new opportunities for Bulosan, with the 1940s proving to be his most successful decade in terms of publication. He published numerous articles and short stories in national publications, including The New Yorker, Harper’s Bazaar, Town & Country, The Saturday Review of Literature, The New Republic, and Mademoiselle . Most widely read of all was a March 6, 1943 piece in The Saturday Evening Post called “Freedom from Want,” based on U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s “Four Freedoms.” The essay is a lyrical testament to the struggles of American laborers. It was accompanied by a seemingly incongruous painting by Norman Rockwell of a white American family on Thanksgiving . Bulosan’s author profile in the Evening Post tells of how he nearly lost the manuscript in a Tacoma bar.

Bulosan also published a series of books in the 1940s. Two volumes of his poetry appeared in 1942, Chorus for America and Letter from America , followed by a poetic celebration of the US/Philippine war effort, The Voice of Bataan , in 1943. He then hit the national bestseller lists in 1944 with the publication of The Laughter of My Father , a collection of satirical short stories based on folktales from the Philippines. Lastly, Bulosan published his semi-autobiographical novel America is in the Heart in 1946, recounting the experiences of himself and other Filipinos along the West Coast during the Great Depression.

"Mga Larawan na May Nasisirang Lungsod": Ang Ikalawang Digmaang Pandaigdig at Ang Panibagong Kabantugan ni Bulosan

Nang pumasok ang Estados Unidos sa Ikalawang Digmaang Pandaigdig, binago ang pangkaraniwang pansin ng mga Pinoy na nasa U.S. Dahil sa pagsisikap ng mga hukbong Pilipino laban sa Hapon sa Pasipiko, biglang naging magkapanalig ang U.S. sa Pilipinas. At saka binawasan ang kapootan laban sa mga maka-kaliwa, dahil naging kapanalig din laban sa Pasismo ang Soviet Union, at humiram ang Lapiang Komunista ng U.S. ng bagong patakaran ukol sa pagkamakabayan ng mga Amerikano. Na tamo ni Bulosan ang pagbabago ng kapaligirang politiko. Nang sinulat niya ang tula noong 1942, "Mga Larawan na May Nasisirang Lungsod" ["Portraits with Cities Falling"].

Dahil sa panahong pandigmaan, nagkaroon ng bagong pagkakataon si Carlos Bulosan, kaya napakatagumpay siya noong dekadang 1940. Pinaglagyan ng maraming mga artikulo at maikling kuwento ang paglalathalang pambansa, katulad ng The New Yorker, Harper’s Bazaar, Town & Country, The Saturday Review of Literature, The New Republic , and Mademoiselle . Ang pinakabinasa ng mga artikulong ito ay ang tinatawag na "Freedom from Want" noong 1943, binase sa "Four Freedoms" ni Pangulo ng U.S. si Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Noong dekadang 1940, naglathala si Bulosan ng mga hanay na aklat. Ilinitaw ang dalawang tomo ng kaniyang mga tula noong 1942, "Chorus for America" at "Letter from America." Noong 1943, ang sumunod dito'y ang pagdiriwang ng mag-pagsisikap pangdigmaan ng U.S. at ng Pilipinas, "The Voice of Bataan." Naging miyembro siya ng pinakamataas sa mga nabibiling aklat dahil sa kaniyang paglalathala ng The Laughter of My Father noong 1944, ang paglilikom ng mga satirikal na maikling kuwento base sa mga alamat galing sa Pilipinas. Sa katapusan, ilinathala niya ang kaniyang mala-kathambuhay, America is in the Heart , noong 1946. Ang paksang ito’y ang mga pangyayari ni Bulosan at ng mga ibang tao, sa Kanlurang Baybayin noong Great Depression.

Back to top

- Biographies and Features

- Morgenthau Holocaust Project

- Timeline: FDR Day by Day

- Research the Archives

- The Pare Lorentz Center

- Student Resources

- Summer Activities

- Social Media

- Museum Visit

- Research Visit

- Field Trips & Group Visits

- Museum Store

- What is a Presidential Library

- The Roosevelt Story

- Events & Registration

- Press and Media

- Program Archives

- Search FRANKLIN

- Plan a Research Visit

- Digital Collections

- Featured Topics

- Morgenthau Project

- Teaching Tools

- Civics for All of US

- Resources for Students

- Distance Learning

- Teacher Workshops

- Field Trips

- NAIN Teachers Conference

- Activities at Home

- 75th Anniversary

- History of the FDR Library

- Library Trustees

- Tell Us Your Roosevelt Story

- Intern and Volunteer

- Donate TODAY!

- Ways To Give

- Get Involved

- Roosevelt Institute

- RI Annual Reports for Roosevelt Library

FDR and the Four Freedoms Speech

Web content display web content display.

Franklin Roosevelt was elected president for an unprecedented third term in 1940 because at the time the world faced unprecedented danger, instability, and uncertainty. Much of Europe had fallen to the advancing German Army and Great Britain was barely holding its own. A great number of Americans remained committed to isolationism and the belief that the United States should continue to stay out of the war, but President Roosevelt understood Britain's need for American support and attempted to convince the American people of the gravity of the situation.

In his Annual Message to Congress (State of the Union Address) on January 6, 1941, Franklin Roosevelt presented his reasons for American involvement, making the case for continued aid to Great Britain and greater production of war industries at home. In helping Britain, President Roosevelt stated, the United States was fighting for the universal freedoms that all people possessed.

As America entered the war these "four freedoms" - the freedom of speech, the freedom of worship, the freedom from want, and the freedom from fear - symbolized America's war aims and gave hope in the following years to a war-wearied people because they knew they were fighting for freedom.

Roosevelt’s preparation of the Four Freedoms Speech was typical of the process that he went through on major policy addresses. To assist him, he charged his close advisers Harry L. Hopkins, Samuel I. Rosenman, and Robert Sherwood with preparing initial drafts. Adolf A. Berle, Jr., and Benjamin V. Cohen of the State Department also provided input. But as with all his speeches, FDR edited, rearranged, and added extensively until the speech was his creation. In the end, the speech went through seven drafts before final delivery.

The famous Four Freedoms paragraphs did not appear in the speech until the fourth draft. One night as Hopkins, Rosenman, and Sherwood met with the President in his White House study, FDR announced that he had an idea for a peroration (the closing section of a speech). As recounted by Rosenman: “We waited as he leaned far back in his swivel chair with his gaze on the ceiling. It was a long pause—so long that it began to become uncomfortable. Then he leaned forward again in his chair” and dictated the Four Freedoms. “He dictated the words so slowly that on the yellow pad I had in my lap I was able to take them down myself in longhand as he spoke.”

The ideas enunciated in the Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms were the foundational principles that evolved into the Atlantic Charter declared by Winston Churchill and FDR in August 1941; the United Nations Declaration of January 1, 1942; President Roosevelt’s vision for an international organization that became the United Nations after his death; and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted by the United Nations in 1948 through the work of Eleanor Roosevelt.

Suggested Reading

Elizabeth Borgwardt, A New Deal for the World: America’s Vision for Human Rights (Belknap Press, 2005).

Laura Crowell, “The Building of the ‘Four Freedoms’ Speech,” Speech Monographs 22, (November 1955): 266-283.

Samuel I. Rosenman, Working with Roosevelt (Harper & Brothers, 1952).

Halford R. Ryan, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Rhetorical Presidency (Greenwood Press, 1988).

Mission Statement

The Library's mission is to foster research and education on the life and times of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, and their continuing impact on contemporary life. Our work is carried out by four major areas: Archives, Museum, Education and Public Programs.

- Research the Roosevelts

- News & Events

- Historic Collections

- Accessibility

- Terms & Conditions

AT THE SMITHSONIAN

Norman rockwell’s ‘four freedoms’ brought the ideals of america to life.

This wartime painting series reminded Americans what they were fighting for

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)

Alice George

Museums Correspondent

![essay freedom from want A4000110C[1].jpg](https://th-thumbnailer.cdn-si-edu.com/zucqM_kKi8RwPzX4nU4t1R7s9D4=/1000x750/filters:no_upscale():focal(731x475:732x476)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f9/63/f963c1ff-f960-4449-865f-6406aff22c4f/a4000110c1.jpg)

Norman Rockwell, the master of Americana, captured the essence of daily life in hundreds of 20th-century magazine covers, and 75 years ago this month, he accomplished a greater feat, translating the nation’s ideals into indelible images known as the Four Freedoms .

By illuminating rights that every American—and every person—should enjoy, Rockwell’s Four Freedoms validated the U.S. decision to enter World War II and overcome powerful enemies whose actions devalued human life. His enduring messages have lingered in the national consciousness, remaining as significant today as they were when the Saturday Evening Post published them in four consecutive weeks during the winter of 1943.

Rockwell’s images had a clear meaning, says the Smithsonian’s Larry Bird : “Why we fight, what we’re about, what we’re fighting for, what we’re fighting to save.” Bird is co-curator of the National Museum of American History’s exhibition “ American Democracy: A Great Leap of Faith,” which features a large set of the original Four Freedoms war bond posters from 1943.

Immediately after publishing Rockwell’s four paintings— Freedom of Speech , Freedom of Religion , Freedom from Want and Freedom from Fear —the magazine received 25,000 requests to purchase copies. Color reproductions of all four sold for 25 cents apiece. The paintings became the basis for 4 million war posters sold as part of the War Bonds effort, raising $132,992,539. “They were received by the public with more enthusiasm, perhaps, than any other paintings in the history of American art,” The New Yorker reported in 1945.

Within weeks of publication, Rockwell’s paintings began a national journey. Across 16 separate cities, a total of 1.2 million people lined up to see the paintings, which were put on display in department stores, not museums. Those who bought war bonds received color reproductions in return. After completing that tour, the paintings rode the rails to a wider assortment of towns and cities, where Americans could admire Rockwell’s works in a custom-made train car.

Although the paintings became famous as an endorsement of the struggle to defend American ideals in World War II, the Four Freedoms first entered the American lexicon in President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s January 1941 State of the Union address, almost a year before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor swept the United States onto the field of battle. At the beginning of 1941, when isolationist sentiments still held sway over many Americans, Roosevelt’s goal was a simple one: to convince voters that standing alone ultimately could sacrifice freedoms at home and abroad.

“By an impressive expression of the public will and without regard to partisanship, we are committed to the proposition that principles of morality and considerations for our own security will never permit us to acquiesce in a peace dictated by aggressors and sponsored by appeasers,” he told Americans. “We know that enduring peace cannot be bought at the cost of other people's freedom.”

FDR then described the four freedoms every human being should enjoy—an addition to the speech that the president himself made in its fourth draft. He wanted to make Americans understand why the United States should provide material support for the western Allies as they battled Germany’s Nazi regime and the Japanese empire, both of which were stripping away individual rights. At the time, Roosevelt was convinced the United States was not ready to enter the war, but he believed armaments production for the Allies represented one way to protect cherished freedoms without risking American lives. While his speech planted a seed of inspiration in Rockwell’s brain, staunch isolationists rejected FDR’s message, claiming that it promoted war.

The United States and Great Britain wrapped Roosevelt’s ideas into the Atlantic Charter issued in August 1941. Both the State of the Union and the Atlantic Charter represented these freedoms as international ideals—rights that should belong to anyone anywhere. And through international initiatives such as disarmament and economic stability agreements, any nation should be able to exist without fear and with the opportunity to offer broad rights to its citizens.

For Americans, the First Amendment to the Constitution guarantees freedom of speech and freedom of religion. “Freedom from want” and “freedom from fear” are nowhere in the nation’s founding documents, but they reflect the hopes of a nation emerging from the Great Depression and preparing to enter the biggest global conflict ever. “They are aspirational goals that we, or at least those who believed in the sort of New Deal politics, saw as the role of government,” says Harry R. Rubenstein , who also curated the museum's exhibition American Democracy: A Great Leap of Faith and, like Bird, is a contributor to a book bearing the same title.

Seventeen months after FDR’s address, Rockwell traveled to Washington to promote his idea of illustrating the Four Freedoms to bolster the war effort. His autobiography states that not one official initially welcomed his proposal. The hard truth was that there were people inside and outside of government who questioned the artistic value of Rockwell’s storytelling works, which were often equated with advertising illustrations. Ultimately, though—and the historical record is unclear on the details here—Rockwell was able to persuade the powers that were, reaching an agreement to produce the paintings for the government and the Saturday Evening Post magazine.

After promising to create the images, Rockwell faced the difficult task of transforming governmental phraseology into evocative tableaux on canvas. He had expected to finish all four scenes in two months, but the work dragged on through seven months of false starts and revisions.

Nonetheless, Rockwell was fully committed to the Four Freedoms . “I just cannot express to you how much this series means to me. Aside from their wonderful patriotic motive,” he told his impatient editors, “there are no subjects which could rival them in opportunity for human interest.”

With the February 20, 1943 issue of The Saturday Evening Post , the paintings began appearing weekly, each accompanied by an essay. Freedom of Speech features a blue-collar worker speaking to a room filled with more finely dressed Americans, all listening intently to the Lincolnesque figure’s words. Freedom of Religion depicts several individuals of different religious backgrounds in a moment of prayer. A man wearing a fez holds a Bible or Koran; a woman fingers a rosary. Rockwell worked for two months on this painting, which carries an inscription: “Each according to the dictates of his own conscience.” The artist said later that he could not recall the source of the words; however, almost identical language can be found in the “Thirteen Articles of Faith” written by prophet Joseph Smith in 1842 to explain the bedrock beliefs of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (Mormons).

Freedom from Want pictures a large, healthy family eagerly awaiting a Thanksgiving feast. In Freedom from Fear, a mother and a father check on their sleeping children. In the father’s hand is a newspaper reporting the bombing of London—the only international reference in all four paintings. Rockwell finished these two paintings most quickly, and later said he thought they were the weakest. However, Bird says Freedom from Fear “continues to speak to me, just in daily life. And in that sense, it’s timeless.” Whether the headline refers to German attacks on London or to frightening developments in today’s world, the painting’s message applies.

While the Four Freedoms experienced huge success within the United States, they met a less receptive audience abroad. FDR described freedoms that should belong to everyone in all nations. Rockwell’s paintings, on the other hand, showed recognizably American scenes and seemed to celebrate life in the United States. Like most of his works, they portrayed Americans as a humble, God-fearing people who enjoy a strong and prosperous family life.

Freedom from Want features a dinner table laden with food—an image that rankled non-Americans suffering from the effects of wartime shortages. The sumptuous scene is colored by a playful Rockwell smiling up at the viewer from the lower right-hand corner. (This occasional representation of himself, much like film director Alfred Hitchcock’s cameo appearances in his suspenseful films, offers an unexpected dash of humor. A single eye on Freedom of Speech ’s right edge also belongs to Rockwell. He thought that inserting part or all of his face into scenes appropriately cast doubt on connections between art and truth.) Freedom from Fear , too, irritated some people in Allied war zones who were unable to protect their children from an immediate threat. Oceans away from World War II’s battlefronts, Rockwell’s protective parents enjoyed an extra layer of safety unavailable to parents in most nations at war.

Rockwell’s simple images transmit complex messages. What Bird calls “his toolkit” included Rockwell’s interpretation of “human nature, human condition, irony, juxtaposition of things”—all part of a technique now well-known to most Americans. Rubenstein believes “the genius of his work is taking a very lofty ideal and bringing it down to the most personal experience.” He also sees Rockwell’s choice of domestic scenes as one of the paintings’ strengths: “These aren’t the politicians; these aren’t heroic soldiers. These are the people who support the nation, or what the nation had been and hoped to be again.”

Roosevelt admired Rockwell’s skillful delivery of a potent message. “I think you have done a superb job in bringing home to the plain, everyday citizens the plain, everyday truths behind the Four Freedoms,” he told Rockwell. Says Bird, the artist “dramatized their meaning in a way that was not available to Roosevelt, as great as he was as a radio orator and as a communicator.” Capturing idealized visions of Americans, what Bird calls “our better angels,” empowers Rockwell’s art.

After the war, the already well-traveled paintings made another national expedition aboard the Freedom Train. More than 3.5 million Americans in 326 cities saw them on that 1947-48 trek. The offices of the Saturday Evening Post served as the paintings’ home throughout the 1950s and most of the 1960s, with Rockwell finally reclaiming them before the magazine closed its doors in 1969.

Today, the paintings reside in the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, but this year, they begin another tour, entitled "Enduring Ideals: Rockwell, Roosevelt & The Four Freedoms." It starts in May at the New York Historical Society, and visits Detroit, Washington, D.C., Houston and Caen in Normandy, France.

Get the latest on what's happening At the Smithsonian in your inbox.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)

Alice George | | READ MORE

Alice George, Ph.D. is an independent historian with a special interest in America during the 1960s. A veteran newspaper editor, she is recently the author of The Last American Hero: The Remarkable Life of John Glenn and has authored or co-authored seven other books, focusing on 20th-century American history or Philadelphia history.

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

4 Freedom from Want

- Published: December 2015

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions