Ethical Norms as the Foundation of Torah

Parashat Va'Etchanan

Rabbi ethan tucker, download files.

Essay download

Source sheet download

Dvar Torah download

The Torah and ethical norms are not supposed to be in conflict. One of the most difficult and wrenching experiences one can have is to feel that they are. We have all felt it at one point or another, if only for a fleeting moment: Our understanding of what God wants of us and our understanding of what is demanded of the average, decent person sometimes feel irreconcilable. Even more deeply, the Torah often speaks in very different terms and with very different assumptions than does any given contemporary discourse of ethics and morality. Should these two different discourses and frames remain separate or ought they to be integrated in some meaningful way? Is the parochial covenantal discourse of the Jewish covenant meant to be walled off from a more general human discourse about what is right? Or does the Torah intend for these conversations to be unified, even if a great deal of learning and searching is required in order to bridge the apparent gaps between them?

In a way, the Torah addresses this question explicitly in this week’s reading. In Devarim 4:6 the Torah says the following:

ושמרתם ועשיתם כי הוא חכמתכם ובינתכם לעיני העמים אשר ישמעון את כל החקים האלה ואמרו רק עם חכם ונבון הגוי הגדול הזה

You shall guard and perform [the mitzvot ], for doing so is your wisdom and understanding in the eyes of the nations. When they hear all of these rules, they will say, “What a wise and understanding people is this great nation!”

We can read this verse through its surface meaning: The mitzvot are obviously good, attractive, and compelling, such that doing them will quite evidently evoke appreciation—and even envy—from outsiders who encounter a life based on them. Moshe here is exhorting the people to recognize what a good thing they have. But one need not dig too much deeper to hear that the text here is not necessarily making just a descriptive claim here, but a prescriptive one as well. The Torah and its mitzvot are supposed to evoke this sort of admiration from outsiders. If it does not, something is wrong. It is not a far leap from here to suggest that interpretations and applications of the Torah that evoke revulsion from external observers are potentially suspect and in need of deeper thought and reevaluation. This line of thinking can be applied not only to our intellectual interpretations of Torah and its Sages, but to its vision of covenantal life through mitzvot as well. In other words, one of the very basic things the Torah tells us about itself is that it is intended to be a blueprint for life that telegraphs the soundness of its structure and beauty of its architecture.

In this week’s longer essay, I explore this line of argument by looking in depth at a lengthy passage from one modern rabbi, R. Moshe Shmuel Glasner, who tackled this issue. I will give an overview of one of his central points here, but it is an outstanding and fascinating text and I urge you to encounter it directly.

R. Glasner begins with a provocative argument about the relationship between specifically Jewish and generally human norms:

דור רביעי, הקדמה, כו.-כו:, ר' משה שמואל גלזנר, הונגריה, המאה הי"ט-כ'

ועוד תדע דבכל דברים המאוסים שנפשו של אדם קצה בהם, אפילו לא היה התורה אסרתן, היה האדם העובר ואכלן יותר מתועב ממי שעובר על לאו מפורש בתורה כי כל מה שנתקבל בעיני בני אדם הנאורים לתועבה אפילו אינו מפורש בתורה לאיסור, העובר על זה גרע מן העובר על חוקי התורה.

Dor Revi’i, R. Moshe Shmuel Glasner, Hungary, 19 th -20 th c.

Moreover, understand that if one eats things that are disgusting and reviling, even if the Torah has not forbidden them, he is more abominable that one who violates an explicit biblical prohibition. If one violates anything agreed upon as abominable by enlightened people—even if it is not explicitly forbidden by the Torah—he is worse than one who violates the laws of the Torah.

The Torah, says R. Glasner, forbids and requires many things. But it is also silent about many things as well. It never says, “Don’t eat a sandwich that has fallen into the gutter and is covered with polluted slime.” Nonetheless, eating such a sandwich would be deemed revolting and disgusting by any reasonable person. Not only should we not mistake the Torah’s silence for neutrality on this front; rather, we should understand that committing such revolting acts is even worse than violating the Torah’s explicit prohibitions! In other words, eating such a filthy, disgusting piece of food is worse than eating pig! R. Glasner argues that this is self-evidently so, because the Torah chooses to begin with a general human story about pre-Jewish people created in the image of God. Properly read, the Torah must be understood as building the specific Jewish revelation on top of this more elemental human condition.

What is the barometer for classifying something as reviling in this sort of foundational way? If an action is something that is “agreed upon as abominable by enlightened people,” then it is a more basic prohibition than anything the Torah singles out for us. For R. Glasner, the “enlightened people” he speaks of here represent his fellow non-Jewish Europeans whom he admires and feels to be decent people. If such people understand something to be disgusting, the Torah cannot possibly be neutral on that point. Rather, that instinct must be incorporated into the Torah’s expectations of all people, including Jews.

In building his case for this point of view, R. Glasner turns to this week’s Torah reading:

וכל שאסור לכלל מין האנושי הנאורה בחוק הנימוס אי אפשר להיות מותר לנו עם קדוש, שמי איכא מידי דלדידהו אסור ולדידן שרי? והתורה אמרה שהגוים יאמרו: "כי מי גוי גדול אשר לו חקים ומשפטים צדיקים, ואם המה יעמדו על המדרגה יותר גבוה בחוקים ונימוסים, הרי יאמרו עלינו, "עם סכל ונבל" ולא חכם.

Anything that violates the norms of enlightened human beings cannot be permitted to us, a holy nation; can there be anything forbidden for them but permitted to us? The Torah says that the nations are supposed to say: “What a great nation, with such just laws and statutes!” But if they are on a higher level than we in their laws and norms, they will say about us: “What a foolish and disgusting nation!”

For R. Glasner, when human opinion has squarely and resolutely lined up against the morality of a given activity, that is a religiously significant fact. A universally-shared revulsion at something is a barometer of that thing being beyond the bounds of basic human decency. And that, in turn, should make us realize that the thing in question is regulated by the internal Torah command of קדשים תהיו, the demand to be holy. His proof for this interpretation comes from the Torah’s self-description with which we began this essay. The story the Torah tells us about itself is that the way of life it prescribes for the Jewish people is meant to be the envy of the world. People are meant to encounter an observant Jew and to say, “This seems like the most fantastic and wise way of living one’s life that I can imagine.” The moment that a person’s interpretation of Torah would evoke the deep disgust of the average civilized person is the moment when the Torah’s intended story about itself has been lost. For R. Glasner, it is a bedrock principle of the Torah, a core internal principle of Jewish law, that Jews can never be perceived to be on a lower level than their Gentile neighbors.

The image that perhaps best captures this is one of a boat floating above the water. The waterline represents the basic human standards of decency and morality that we expect of all people. The Torah is a boat that floats above that level, meant to give its passengers an even greater sense of responsibility. The parochial covenant rests on top of the universal mandate from which it sprung. But if the waterline rises, clearly so too must the boat. If the boat is anchored to a fixed point, it will be submerged by the rising sea levels and soon be entirely underwater. This, says R. Glasner, is impossible and unimaginable. Even if certain universal human norms are not historically prior to the Torah, they are surely philosophically prior to it. It doesn’t matter if humanity considered a certain action to be neutral for most of its history. If all enlightened, decent, intelligent people come to abhor that action, then the Torah implicitly tells us that Jews must abhor it as well. In fact, it is even more basic that that: Jews are also human beings, and the Torah never wants us to forget that. Instead of seeing an emerging human consensus around a given practice’s morality as a challenge external to Torah that must be grappled with, we should instead see the human part of ourselves and of the Torah calling to us to reckon with this aspect of God’s word as well.

This vision of Torah and mitzvot asserts that the Jewish and human stories are not separate and competing frames. Rather, the Torah tells a story of a Jewishness that emerges from humanity and a particular revelation that emerges from, is built on, and remains interdependent with a more universal human ethics. Asserting this does not downgrade the Torah. In fact, it is the only way to truly honor it.

In the longer essay I engage the challenges with this model and how we might critique and refine it. Wouldn’t this model destabilize all recognizable structures of Torah and mitzvot in the face of significant shifts in human opinion? What happens when human norms on sexuality shift drastically and conflict with the Torah’s laws? What happens if circumcision is regarded as a barbarity? Doesn’t R. Glasner’s model just lead to the self-liquidation of Judaism in the face of external norms? I address these questions and would argue forcefully that R. Glasner’s model is an indispensable way to think about Torah, even if it must be carefully and thoughtfully applied. Most important is the notion that both the Torah and Jews are a part of the larger human conversation about morality, such that they do not simply capitulate to the moral trends of the day but engage with them as equal partners. Just as many mitzvot are countercultural, pushing against social conventions in order to create better and holier realities, so too the Torah has a voice in shaping humanity’s moral sense when it affirms the basic holiness of certain actions like circumcision. And Jews are not just passive respondents to global surveys on morality. Yes, R. Glasner insists, rightly, that one cannot be a Jew without being a human being first, and one cannot be a human being created in the image of God while ignoring fundamental categories of human decency, ethics, and morality. But Jews are a part of that human fabric as well and they have the right—and the obligation—to be participants in the human conversation about morality and human dignity. R. Glasner’s speaks about כל מה שנתקבל בעיני בני אדם הנאורים לתועבה/“anything agreed upon as abominable by enlightened people.” Jews are part of this set of enlightened people as well and they have the right to weigh in on a debate regarding what is and is not abominable. It is appropriate and necessary for Jews to bring their voice, influenced by the Torah, to that conversation.

R. Glasner would, above all, insist that we must integrate our human/moral and Jewish/Torah conversations. It might be possible that, in some circumstances, our human/moral instincts would push us to discover internally articulated applications of Torah we had not previously considered and come to translate universal insights and critiques of mitzvot into the language of halakhah . More likely, our Jewish/Torah perspective on an affirmative commandment would lead us to argue vociferously for the morality of a mitzvah under attack. But here is the key: R. Glasner would insist that we defend the mitzvah in question on human/moral terms , pushing back against the apparent human consensus against it. What is required is an articulation of the defensibility of the mitzvah in a general forum, an effort to persuade the average, decent person that they ought not to be appalled by this practice. What is unacceptable is to hide behind a bifurcated discourse that says, “Circumcision does indeed seem barbaric, but what can I do, the Torah commands it?” It is that sort of split between the human and Jewish realms that leads to a distortion of the Torah’s message about itself and prevents it from being great in the eyes of the nations. If an emerging moral consensus among humanity does not force one to reconsider the proper application of a mitzvah , then it virtually commands us to write opinion pieces to persuade our fellow human beings that that consensus is wrong. That obligation flows from being recipients of a Torah that is simultaneously human and Jewish.

At the end of the day, the Torah itself tells us that other peoples will admire it and find its teachings wise. That means we must live religious lives that respond to one unified question: What does God want from me? We must never forget that we are meant to answer that as Jews and as human beings, all at the same time.

Related Content

Recounting the Omer

Parashat emor, jewish law and jewish values, a conversation.

"Do Moshe's Hands Really Make War?"

The battle with amalek.

Love, Compassion, and the Future of Jewish Life

Codes in conversation, parashat kedoshim.

Sefer Bemidbar Kickoff

Devash: parashat beha'alotkha 5784, devash: parashat naso 5784, devash: parashat bemidbar 5784, devash: parashat behukkotai 5784.

How to Write a D'var Torah

A d’var Torah (a word of Torah) is a talk or essay based on the parashah (the weekly Torah portion).

As most frequently encountered, a d’var Torah (a word of Torah) is a talk or essay based on the parashah (the weekly Torah portion). Divrei Torah (plural of d’var Torah ) may be offered in lieu of a sermon during a worship service, to set a tone and a context at the opening of a synagogue board or committee meeting, or to place personal reflection within a Jewish context. Especially at times of loneliness, distress, indecision or other personal difficulties, you may find it helpful to read and interpret the Torah portion with a particular focus on how the thoughts and actions of our foremothers and forefathers—intensely human characters—might help you deal with your own challenges.

Many of the same principles apply to preparing and delivering a d’var Torah as to other presentations before a group

- Adhere to the allotted time frame;

- Make your comments appropriate to the audience;

- Know what message you want to leave with the audience;

Many people are reluctant to accept an invitation to write or give a d’var Torah for the first time. They shouldn’t be, not only because all kinds of help is available, as described below, but also because they will be fulfilling numerous mitzvot: the mitzvah of learning Torah, the mitzvah of teaching Torah, and, perhaps most important, the mitzvah of reminding the community that talmud Torah, the serious study of Torah, is not an activity limited to rabbis but is available to and incumbent upon all of us.

The person who delivers a d’var Torah is called the darshan (interpreter or explainer), and the interpretation offered is known as the drash . As darshan, you have the option of discussing the parashah , the weekly Torah portion, as a whole, or of zeroing in on certain words or verses. Often, your time allotment will make that choice for you. If time permits, you may want to start with an overview of the entire parashah , and then segue to the verses that will be your focus, explaining why you find those verses particularly compelling or worthy of attention.

As you prepare your drash, you are not alone. You are just the latest in a chain of darshanim that goes back two millennia. In fact, you are well advised to approach the text as your predecessors would have, using the PaRDeS* method, the historic approach to studying Jewish text, which focuses on these questions:

- What’s the simple meaning or literal translation?

- What did that signify in the context of its time?

- How has it been explained by the rabbis over the centuries?

- What should it convey to us today?

However, you have an advantage over those countless generations of Torah explicators who have gone before you. You have access to numerous Torah translations and commentaries, including these from a Reform perspective:

- The Torah: A Modern Commentary (Plaut, URJ Books and Music)

- The Torah: A Woman’s Commentary (Eskenazi and Weiss, URJ Books and Music)

- A Torah Commentary for Our Times (Fields, URJ Books and Music)

- The Torah commentaries on this site

I personally like to compare translations and commentaries from other perspectives, and typically consult alternate translations–especially the “old” JPS translation as found in the classic Hertz Torah commentary, plus those of Everett Fox and Robert Alter. I also consult what is perhaps the broadest, deepest resource of all by typing into “Reb Google” the name of the parashah .

Although all these resources can show you what others have thought and said about the parashah , your job as darshan i s to share with your listeners what you have learned from the text and the sources, and now want to teach them. Here are some guidelines that may help:

- If you have a problem with the text, or with the historic interpretations, share it with the group–particularly if your setting permits your presentation to be interactive.

- If you are struck by a particular insight, rather than presenting it as your original thought, cite your source–let Rabbi Gamaliel’s authority enhance your credibility, and show that you have done your homework.

- Show respect for your audience. Chances are that many of them know as much about the material as you do. But don’t be intimidated by that either, because chances are even greater that most of them don’t.

- Be sure to translate any Hebrew word you use. Even as common a word as mitzvah is likely to be heard as “good deed” if you don’t clarify it as “sacred obligation.”

- If, like me, you prefer to present from a written text, use your manuscript as a guide, but talk it, rather than reading what you have written.

- Make regular eye contact with your listeners–be there for them and with them. (It’s okay to read brief quotations from the attributed writings of others, but keep them brief!)

- Don’t try to wing it from the text alone. Because we construe the Torah as a living document, its words can only be understood in the context of the generations.

- Just because a d’var Torah primarily is designed to teach does not mean it may not entertain. A touch of humor is in order, as long as it is germane to the lesson. No jokes for joke’s sake. As darshan , you have a responsibility to take the material you are presenting seriously, which doesn’t mean you can’t find the humor in it. What could be funnier than Adam passing the buck—“The woman whom You gave me, gave me the fruit, so I ate,”—or Abraham’s negotiation with Ephron the Hittite: “What’s 400 shekels between you and me?”

The approach you take with your d’var Torah is dependent on the hand you were dealt. Character analysis is an obvious possibility if you’re in Genesis, but won’t work if your parashah is in Leviticus, where major themes like purity and sacrifice come to the fore. Even when the text doesn’t direct you to your message, the commentators will. And where you find dueling commentators, you might want to resolve their argument to your own satisfaction. As we read in Pirke Avot, The Sayings of the Fathers, “Turn it and turn it, for everything is in it.” As a darshan , you are in charge, and have the privilege of turning it until you find a topic or an issue that resonates with you.

Giving a d’var Torah is serious business, and you should feel seriously honored that you were invited to do so. As you go about preparing your d’var , remember to take the task seriously, but try not to take yourself too seriously. A gentle touch will go far in shedding light on the text, and in earning you the respect of your colleagues, from whom you likely will hear the words “ Yasher koach. ”May your strength remain, so you can teach us Torah again.

*PaRDeS is an acronym for the four levels of understanding: P’shat , the simple meaning of the words, Remez , hint, construed as the context of what lay behind those words at the time they were first uttered, Drash , explanation, or how the text has been interpreted or enhanced by the rabbis over the centuries in the Midrash and other commentaries, and Sod , secret, the hidden meaning that we should extract from the words to make them relevant in our lives today.

- Torah Study

Laurence (Larry) Kaufman , z"l, was a member of Beth Emet, the Free Synagogue , in Evanston IL, where he coached b'nai mitzvah candidates on their divrei Torah . A long-time Reform Movement activist, he served on the North American Board of Union for Reform Judaism, the North American Council of the World Union for Progressive Judaism, the Board of ARZA, and was a past president of Temple Sholom of Chicago. In retirement, he consulted with an Israeli technology company on its U.S. public relations and marketing communications.

Torah (The Five Books of Moses)

Rishonim on tanakh, acharonim on tanakh, modern commentary on tanakh, about tanakh, weekly torah portion, visualizations, support sefaria.

Stay updated with the latest scholarship

Basing Judaism on Truth: Does the Torah Lie?

November 4, 2015

Marc Zvi Brettler

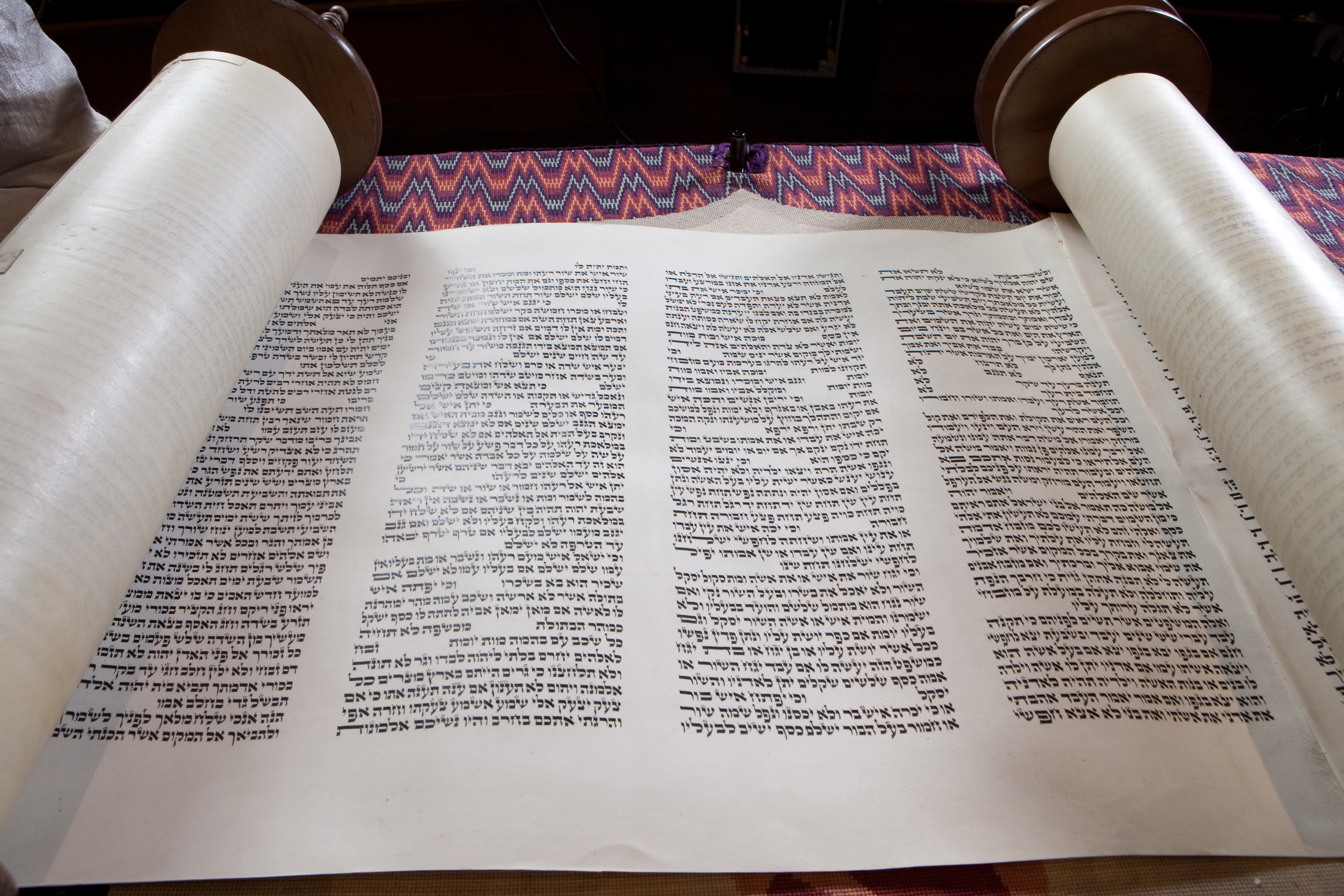

A Torah scroll. 123rf

Over my thirty plus years of teaching biblical criticism, or, as I prefer to call it, the contextual approach to the Bible, [1] I have seen a wide spectrum of reactions by students to the academic finding that the Torah developed over time. For many, myself included (see my essay, “ On Becoming A Critical Torah Scholar” ), this approach enriches our appreciation of Torah and Judaism. Others, however, have experienced a sense of betrayal—that what they had been previously been taught was a lie, or even that the Torah is a “book of lies.” This is a challenge that TheTorah.com has been asked to address on numerous occasions.

In the post titled “Controlled Exposure or Isolationism,” on the blog with the telling name Emes Ve-Emunah – A Forum for Orthodox Jewish thought, R. Harry Maryles recently explored the extent to which students of different ages at different educational venues should be exposed to what the author calls “biblical criticism,” an unfortunate term, since it suggests to some, like Maryles, that its goal is to “criticize” the Bible. In presenting the issue, the author observes:

“I personally find it impossible to believe that the entire narrative of the Torah never happened. …that it’s just an allegory used to convey God’s message. Because that would make it a lie. Basing belief on lies is not the best way to find God.”

While I sympathize with the fear that motivates this line of reasoning, this statement is highly problematic. [2] It attributes, incorrectly, to biblical scholars the idea that the entire Bible was invented out of whole cloth, a view with which few scholars would concur also assumes that allegories, or symbols, or metaphors all lie, and cannot assist in our search for God. But why should we privilege the literal over the figurative? Do we learn less from novels than from biographies?

Figurative Passages in the Bible

In fact, whether or not the Bible is meant to be taken literally, or only literally, has been debated by the most significant medieval Jewish interpreters and philosophers. It is a remarkable coincidence that several recent TheTorah.com articles have focused on this issue, showing how vibrantly it was debated in the middle ages. [3]

Modern academic scholars continue to debate—often unaware of the important earlier roots of the issue—if particular stories were meant to be taken literally or not. For example, in How to Read the Jewish Bible , [4] I argue that the creation stories were written as myths, not as natural history or science. By “myth” I do not mean a silly or scientifically incorrect story, but a narrative interested in explaining and advocating basic values. That is what torah, in the sense of “instruction” means. Indeed, many traditional mefarshim have understood the initial chapters of Genesis similarly in their insistence that these stories are primarily didactic rather than historical.

Whether to take a story literally or figuratively may be one of the most difficult broad questions in modern biblical scholarship. But certainly not all biblical stories that are set in the past are meant literally. I agree that we cannot, and should not, search for God through lies, but non-literal texts are not lying. But is it a lie when we say, e.g., of a women we love “she is a pearl”?

Even when a biblical text is gets its history wrong, the author need not be characterized as a “liar.” [5] Moreover, does the value of a biblical account reside merely in its accuracy? For example, it is clear that the book of Chronicles reports events in a way that is factually different than Samuel-Kings—and most scholars believe that many of these differences are not based on better, new sources, but on the author’s theological beliefs and historiographical creativity. [6] Is the Chronicler a liar? Can we not learn much that is valuable about God and morality from this work, even while accepting that it is often factually inaccurate? Furthermore, would this need for “accuracy in reporting” apply to midrash or aggada as well? Perhaps some biblical texts are similar to midrash or aggada, and had no intention of narrating the past as it transpired?

Apikursus and the Search for God

Maryles’s post, in an effort to prevent what it believes is apikursus , is also premised on the assumption that Judaism mandates particular beliefs. This is a debatable point, and it has been much discussed especially since the Rambam promulgated this ikkarim , or central tenets of belief. After all— if ikkarim are so central to Judaism, why weren’t such ikkarim collected and promulgated in the period of the Talmud? The work of Menahem Kellner [7] offers important insights into the place of belief in general, and of particular beliefs, in Judaism. It is not an open and closed issue that disagreeing with a particular formulation of the Rambam constitutes apikursus .

I appreciate Maryles’s search for “best way to find God,” but doubt that the unreserved, multiple use of the term apirkursus is the best way to do so. Nor do I agree with his entire approach, which assumes that it is better to declare a priori that the Torah is factually true when in may not be, rather than declaring personal loyalty and attachment to the Torah irrespective of its factual accuracy.

Finally, Maryles’ post, and much of the aggressive response to academic biblical studies in general, assumes that academic biblical scholarship is a disease that requires inoculation lest we get sick. We certainly should discuss, as he suggests, how, when, and where different types of biblical scholarship should be taught, and TABS – TheTorah.com has begun to address this. [8] But we should do so in a more positive fashion, without presuming that we must bring an epidemic under control. It is important to realize instead that exposure to contextual, or historical-critical biblical studies has for many enhanced Jewish appreciation and observance.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Prof. Marc Zvi Brettler is Bernice & Morton Lerner Distinguished Professor of Judaic Studies at Duke University, and Dora Golding Professor of Biblical Studies (Emeritus) at Brandeis University. He is author of many books and articles, including How to Read the Jewish Bible ( also published in Hebrew), co-editor of The Jewish Study Bible and The Jewish Annotated New Testament (with Amy-Jill Levine), and co-author of The Bible and the Believer (with Peter Enns and Daniel J. Harrington), and The Bible With and Without Jesus: How Jews and Christians Read the Same Stories Differently (with Amy-Jill Levine). Brettler is a cofounder of TheTorah.com.

Publish Date

[1] This term is used in Barry W. Holtz, Textual Knowledge: Teaching the Bible in Theory and Practice (NY: JTS Press, 2012); it has a more neutral ring than “biblical criticism.”

[2] In his TABS essay, “Metempsychosis (Gilgul), Academic Study of the Bible, and the Meaning of Truth,” Isaac Sassoon also deals with the fear issue, and the problematic responses it engenders.

[3] See David Frankel’s TABS essay, “Torah Narratives with Angels Never Actually Happened: Heretical or Sublime?” See also Gregg Stern’s TABS essay “ Allegorizers of Torah and the Story of their Prosecution in Languedoc (1305)” See also my article, “The Bible as History,” in People of Faith and Biblical Criticism (eds., Yehudah Brandes, Tova Ganzel and Chayuta Deutsch; Jerusalem: Beit Morasha, 2015), 211-223 [Hebrew]. For more on this book see, “An Interview with Dr. Tova Ganzel.”

[4] NY: Oxford Univ. Press, 2007, pp. 38-40.

[5] For an example of a story in the Torah whose plot is based on a discredited scientific notion, see Zev Farber’s TABS essay, “Maternal Impressions: From Sheep to Humans – Jacob’s Ancient Scientific Trick.” See also Ziony Zevit’s analysis of the creation story, in his TABS essay, “Before the Beginning: Appreciating the Thought of an Ancient Cosmologist.” He comes at the account assuming that the author is trying to describe factually how creation happened and is still able to learn much about how the Torah thinks about God and the universe and notice intersections with modern cosmology.

[6] For more on this see Hartley Koschitzky’s TABS essay, “The Chronicles of Divine Justice: Why God Destroyed the Kingdom of Judah.”

[7] See Menachem Kellner’s TABS essay, “Must we have Heretics.”

[8] See Steve Bayme’s “Embracing Academic Torah Study: Modern Orthodoxy’s Challenge,” Eric Grossman’s “Bible Scholarship in Orthodoxy,” and Zev Farber’s, “Can Orthodox Education Survive Biblical Criticism.”

Renewing the Torah’s Authority

Why Write a Biblical Commentary?

Is halacha still binding if one accepts biblical criticism?

Benjamin D. Sommer

“Who Wrote the Bible?” Challenged My Conservative Jewish Education

It’s Biblical! The Meaning Is Less Relevant

A Journey of Twenty Years with R. Dovid Steinberg

A Tribute to My Friendship with David Steinberg

To See the Enemy’s Family

Rescuing Captives: From Abraham to David

When Peace Fails: Psalm 120

Virtue Signaling or Speaking Out: Ezekiel versus Jeremiah

The Flood of Regret

When Words Fail, the Bible Still Murmurs

Launched Shavuot 5773 / 2013 | Copyright © Project TABS, All Rights Reserved

The Jewish Publication Society

Creating a shared literary heritage since 1888.

The Heart of Torah Essays on the Weekly Torah Portion, Vol 1 & 2, Gift Set

- Rabbi Shai Held (author)

- Rabbi Irving Greenberg (foreword)

- Author Info

- Excerpt & Resources

About the Book

Or buy the volumes separately: Vol.1: Genesis and Exodus , Vol. 2:Leviticus, Numbers & Deuteronomy

Collectively, Rabbi Shai Held’s Torah essays—2 essays for each weekly portion— in The Heart of Torah, Volume 1 (Genesis and Exodus) and Volume II (Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy) open new horizons in the world of Jewish biblical commentary. A renowned rabbi, lecturer and educator, Held brings creative theological exploration, penetrating psychological observation, keen attentiveness to literary detail, deep learning in Jewish philosophy and theology, and compassionate attention to the stirrings of the human heart.

He mines Talmud and midrashim, great writers of world literature, and even astute commentators of other religious backgrounds. He lets small textual anomalies slowly open up into fundamental questions about God, human nature, and what it truly means to be a religious person in the modern world. Along the way, he illuminates the centrality of empathy in Jewish ethics, the predominance of divine love in Jewish theology, the primacy of gratitude and generosity, and God’s summoning of each of us—with all our limitations—into the dignity of covenantal relationship.

Rabbi Shai Held

Rabbi Shai Held (PhD, Harvard, 2010; Ordination, JTS, 1999) is co‑founder, dean and chair of Jewish Thought at Mechon Hadar and directs its Center for Jewish Leadership and Ideas. A renowned lecturer and educator, he is a 2011 recipient of the Covenant Award for excellence in Jewish education and has been named multiple times to Newsweek ’s list of the top 50 rabbis in America. He has taught at institutions such as Drisha, Me’ah, Combined Jewish Philanthropies, and the Rabbinic Training Institute, and he currently serves on the faculty of the Wexner Heritage program. He is author of Abraham Joshua Heschel: The Call of Transcendence (Indiana, 2013).

Rabbi Irving Greenberg

Rabbi Irving Greenberg is a preeminent Jewish thinker, theologian, activist, president of the J.J. Greenberg Institute for the Advancement of Jewish Life, and senior scholar in residence at Hadar. He is the author of five books, including For the Sake of Heaven and Earth: The New Encounter between Judaism and Christianity (JPS, 2004).

Book Reviews

- Rabbi Held quoted in this Forward piece by Jane Eisner: http://forward.com/opinion/386768/how-do-we-be-jewish-after-a-year-of-trumps-America/

- Rabbi Held included in the “Forward 50,” including a mention of the book:

- http://forward.com/series/forw ard-50/2017/shai-held/

- Parabola excerpt listed in new issue’s TOC, ://parabola.org/cu rrent-issue/

- Christian Century excerpt: https://www.christian century.org/article/critical-e ssay/babel-story-about-dangers -uniformity

- Review on Jewschool ( https://jewschool.com/2017/10 /80422/learned-jew-two-easy-st eps/ )

- Mention in Jane Eisner’s “The Happiest Day of My Life” in print issue of Forward magazine (online version now up, too: http://forward.com/cultur e/jewishness/384965/why-my-bat -mitzvah-was-the-happiest-day- of-my-life/ )

- Unorthodox podcast appearance: http://www.tabletm ag.com/jewish-life-and-religio n/246524/unorthodox-episode-10 7-rabbi-shai-held-high-holiday -resolutions-5778

- Jewish Standard profile: http://jewishstandard .timesofisrael.com/the-heart-o f-torah/

- Brief mention in Southern Jewish Life magazine ( https://issuu.com/sjlmag/docs /sjl1017ds/48 )

- Interview on Chicago radio: https://www.wbez.org/sh ows/morning-shift/rabbi-questi ons-what-kind-of-god-you-worsh ip/aed2ccee-c4b5-4c62-8af0-1ea a66d03766

- Profile on JewishBoston.com: https://www. jewishboston.com/rabbi-shai-he lds-contemporary-torah-comment ary/

- Profile from The Jewish Week: http://jewishweek.timeso fisrael.com/a-biblical-comment ator-with-heart/

- Profile in Jewish Herald-Voice (Houston): http://jhvonline.com/on- gratit ude-and-fraudulent-leadership- p23231-89.htm

- Review in Jewish Advocate (paywalled): http://www.thejew ishadvocate.com/news/2017-09-1 5/Arts/A_pair_of_books_on_pars has_and_menschlichkeit.html

- Mention of October 9 event on Philadelphia Jewish Voice site: http://pjvoice.org/event /sicha-delving-into-the-heart- of-the-torah-rabbi-shai-held-i n-conversation-with-elsie-ster n-phd/#.Wav-4a2ZM_U

- Mention of October 9 event on Philadelphia Jewish Exponent site: http://jewishexponent.co m/event/sicha-delving-heart-to rah/

- Mention of October 8 event on Washington Jewish Week site: http://washingtonjewishw eek.com/events/rabbi-shai-held -in-conversation-with-jeffrey- goldberg/

- Jewish Book Council review: http://www.jewishbookc ouncil.org/book/the-heart-of-t orah

- Jerusalem Post excerpt: http://www.jpost.com/ In-Jerusalem/Against-entitleme nt-why-blessings-can-be-danger ous-504289

- Mention of Sept. 13th event in Chicago Jewish News: https://www.chicagojewis hnews.com/2017/08/events-comin g-up-in-jewish-chicago-19/ .

- JTA profile re-published in many venues, perhaps most notably in the major Israel-based site, The Times of Israel: https://www.timesofisr ael.com/how-rabbi-shai-held-is -shaping-the-conversation-arou nd-love-and-politics/

- JTA profile: http://www.jta.org/20 17/08/22/life-religion/how-rab bi-shai-held-is-shaping-the-co nversation-around-love-and-pol itics

- Elul project from Ritualwell/Reconstructionist Rabbinical Association: https://www.jewis hrecon.org/embracing-the-stran ger

To Order JPS Books

ONLINE: Click on Read More and Buy from any book page on this site. You will be redirected to JPS's publishing partner, the University of Nebraska Press.

PHONE: Call Longleaf Services at 800-848-6224 or 919-966-7449.

EMAIL: [email protected]

FAX: 800-272-6817 OR 919-962-2704

EBOOKS: Most JPS books are available from ebook vendors.

FOREIGN ORDERS: 919-966-7449 CANADA: Ampersand , 866-736-5620 ISRAEL, EUROPE, MIDDLE EAST, AND AFRICA: Combined Academic Publishers, Ltd., +44 (0) 1423 526350, www.combinedacademic.co.uk [email protected] HAWAII, ASIA, THE PACIFIC, AUSTRALIA, AND NEW ZEALAND: [email protected]

The Best of JPS

Top titles for undergraduate and adult education. Prepared by Rabbi Barry L. Schwartz, JPS Director Emeritus.

JPS 2023 Catalog

Donor discount.

Donate $180 or more to JPS and save 40% on books for an entire year! Donor benefits described here.

Dedicate a Book

Many new JPS books are in progress. Attach your name to a future JPS classic!

JPS Classics

Jps audio bible.

A recorded version of the JPS TANAKH, the most widely read English translation of the Hebrew (the Jewish) Bible.

Produced and recorded for JPS by The Jewish Braille Institute. This complete, unabridged audio version features over 60 hours of readings by 13 narrators.

Visit our Audio Bible page to learn more.

Braille and large print formats of biblical and liturgical materials are also available through the JBI Library.

Subscribe to JPS News

The Torah: a Quick Overview of the Pentateuch

by Jeffrey Kranz | Aug 16, 2019 | Bible Books | 4 comments

The first five books of the Bible ( Genesis , Exodus , Leviticus , Numbers , and Deuteronomy ) form one unified group, which goes by several names. You’ve likely heard them called:

- The Torah , which comes from the Hebrew word for “law”

- The Pentateuch , which comes from a means “five-book work,” or “five-fold book”

- The Books of Moses (also “the Book of Moses,” or simply “Moses”), who’s traditionally credited as the primary source of these books

- The Law of Moses , a blend of the first and third names

Each of these books has their own structure and story to tell, but right now we’re going to zoom out to look at the whole work of the Torah.

Click to zoom.

What does “Torah” mean?

The Hebrew word torah means “law,” or “regulations.” And if you’re at all familiar with these books, that’s almost all the explanation you need. This is where the prophet Moses introduces the people of Israel to the Ten Commandments, along with a host of other “thou shalts” and “thou shalt nots.” If you’re reading the Bible in English, you won’t find the word “Torah” used—instead, you’ll mostly just see the phrase, “the law.”

But this isn’t the kind of law that we’re used to thinking of today. When the writers of the Bible mention “the law,” they’re usually referring to one of two things:

1. The partnership between God and Israel

Humans make modern laws to maintain social order. But the Torah isn’t about legislation; it’s about allegiance . The second book of the Torah, Exodus, tells the story of how God made a pact between the nation of Israel and himself: he would be their god, and they would be his people. This type of pact was known in those days as a covenant , which was a common kind of agreement in the ancient Near East.

A covenant is similar to a contract or a treaty. In ancient times, some kingdoms would become powerful enough to exert their authority beyond their own borders. These kings would come across smaller, lesser nations or city-states and strike up alliances with them. The lesser kings, called vassals , would swear allegiance to the greater king, called the suzerain . The vassals would maintain their own national identity and a degree of autonomy, and would depend on the economic opportunities and military protection provided by the suzerain. The mighty suzerain got tribute and taxes from the vassal—not to mention the bragging rights of another kingdom under their authority.

These covenants usually included rules for the vassal to follow. If the vassal kept the rules, then they could enjoy being in the suzerain’s good graces. If the vassal broke the rules—and especially if the vassal betrayed the suzerain and helped the suzerain’s enemies—they would be punished and cursed.

In a similar fashion, God himself assumes the role of the suzerain in the Torah. He rescues the nation of Israel from Egypt, and offers to partner with them in a covenant. If Israel keeps God’s rules (his law), they will enjoy his guidance and protection in a land of their own. If they don’t, God will remove his protection, and Israel won’t be able to keep their land. Israel agrees to these terms, and the covenant of the law is enacted.

When Moses went and told the people all the LORD’s words and laws, they responded with one voice, “Everything the LORD has said we will do.” Moses then wrote down everything the LORD had said. (Exodus 24:3–4)

That covenant agreement is known throughout the rest of the Bible as “the law.”

2. The specific terms of that covenant

These are the decrees, the laws and the regulations that the Lord established at Mount Sinai between himself and the Israelites through Moses. (Leviticus 26:46)

“The law” can refer to the covenant in general, but you’ll also find references to “laws” within the law. These are the “thou shalts” and the “thou shalt nots.” They’re the rituals for observing feasts and offering sacrifices. They’re the rules about food, sex, clothing, and justice. They’re the directions for setting up an acceptable place of worship. That kind of stuff.

You’ll find these throughout the last half of Exodus, and Leviticus is almost entirely these lists of regulations. They’re interspersed throughout Numbers, and Deuteronomy groups them in the middle. There are hundreds of individual laws, but they all boil down to two overarching principles:

- Love and devotion for God. Israelites couldn’t worship other deities, and because God’s temple was in their midst, the people maintained a degree of ritualistic purity.

- Love and respect for other humans. Israelites were expected to show generosity toward marginalized people, execute justice for both the rich and the poor, and not bring shame on each other.

The specific reasons why certain laws exist can be nebulous. Scholars have made all kinds of arguments for why the ancient Jews believed pork and mixed fabrics were off-limits. The important thing to remember is that they believed that these practices separated them from the surrounding nations of the ancient Near East and reflected how their God is separate from the gods of the other nations.

3. The part of Scripture that records that covenant

Not only does “the law” refer to the stipulations of the covenant and the covenant itself, but it’s also used to refer to the work of the Bible that tells the story of the covenant. While the first five books of the Bible were individual scrolls themselves, they still constitute one general work—which the Jews and Christians call “the Torah.”

Summary of the Pentateuch

The Torah is a five-book work, each book serving its purpose to make the whole. Here’s the primary contents of each book, and how each contributes to the overall work of the Law of Moses.

Genesis ( full summary here ) gives the general backstory of the Torah, setting up a few key dynamics in the cosmos. The ancient Israelites believed that their God called the world out of chaos, and filled it with plants, animals, and people. This God was in charge of both the physical and the metaphysical realms (earth and heaven) and their inhabitants. At the start of the Bible, God, the humans, and the rest of the spiritual beings are at peace with one another.

However, rebellion breaks out, and at least one spiritual rebel (called “the serpent”) tempts humans to rebel against God’s order—instead choosing what’s right and wrong for themselves. Things get violent, and eventually God divides the human and spiritual worlds into nations. (That’s the story of the Tower of Babel .) The ancient Israelites believed that each nation was assigned their own pantheon of spiritual beings (“gods”) to seek protection and provision from. (Deuteronomy 4:19–20; 32:7–9)

“I will make you [Abraham] into a great nation, and I will bless you […] and all peoples on earth will be blessed through you.” (Genesis 12:3–4)

However, the being above all the other gods (“God Most High”), chooses to deal directly with a man we know as Abraham. He promises to give Abraham’s descendants a land of their own. And eventually, God plans to bless every nation through Abraham, even the nations he’s not directly working with. The book of Genesis closes with Abraham’s grandson, named Israel, moving his family to Egypt to escape a famine.

Exodus ( full summary here ) tells the story of how Israel exits Egypt (hence the name) and enters a covenant with God. The descendants of Abraham multiplied in Egypt, and so Pharaoh (part of the Egyptian pantheon) puts them to work as slaves. God then rescues the Israelites from both the oppressive Egyptian humans and their oppressive Egyptian gods.

“I will bring judgment on all the gods of Egypt. I am the Lord.” (Exodus 12:12)

God brings the people of Israel to the foot of a mountain in the wilderness, called Mount Sinai. Here, the people enter that covenant we discussed earlier. Throughout this process, God works with a prophet named Moses. He becomes the human go-between for both God and Israel, tasked with calling the people to follow God and also dealing with their complaints and disputes. He represents God to the people, and mediates on behalf of the nation when the people break God’s laws.

Exodus closes with Moses and the people constructing a portable temple (called the tabernacle). God then comes down from the mountaintop and fills the tabernacle—and just like that, the most powerful being in the cosmos moves in to a migrant camp of mortals.

3. Leviticus

Leviticus ( full summary here ) explores what the people of Israel can and should do about being in such proximity to such a powerful being. It’s mostly a book of rules and rituals for the people and priests to follow in order to keep themselves and the tabernacle acceptable places for such a powerful being.

The first half of this book focuses on expectations for the Israelite priests: the people who maintained the tabernacle and performed religious rituals to God on behalf of the rest of the people. These priests all came from a subgroup of Israelites: the tribe of Levi. The book gets its name from the Levitical priesthood.

Numbers ( full summary here ) charts the journey from Mount Sinai to the very edge of the promised land of Canaan … twice. The book gets its name because at the beginning and end of the book, Moses numbers the people in a census. After the first census, Moses and the people move to the edge of the promised land. However, when a few scouts report back that the people in the land are too strong to be driven out, the people revolt against Moses and God—planning to kill Moses and go back to serving Pharaoh and the Egyptians.

With this move, the whole generation of Israelites forfeits the promised land. The people don’t want to take the land, but God can’t let them undo his work and re-enslave their children in Egypt. So instead God guides, protects, and disciplines the people in the wilderness for the next 40 years, until the next generation replaces the population. This generation comes back to the edge of Canaan, almost ready to possess the land.

Throughout Numbers, we see a tension that builds for the rest of the Old Testament: God finding ways to keep his end of the deal even though Israel consistently doesn’t keep theirs. When the people rebel against Moses and God, the Lord punishes them—but there’s a always remnant of people whom God spares.

5. Deuteronomy

Deuteronomy ( full summary here ) is both a recap of the Torah and a preview of the rest of the Old Testament. The name itself comes from the Greek word for “second law,” because in Deuteronomy Moses again presents God’s laws to the next generation of Israel. Moses reviews all God’s generous and mighty deeds: how he rescued them from Egypt, thundered from Mount Sinai, and provided for them in the wilderness.

Moses then tells the people that when they enter the land, they will need to choose whether or not they will serve the God who gave it to them. They can choose to abide by the laws Moses gives them and enjoy God’s blessings of protection and prosperity. Or, they can abandon the Torah and choose what’s right and wrong for themselves (like the rebellious humans in Genesis). If they make themselves enemies of God by breaking the covenant, then God will remove his protection, and Israel won’t be able to keep their land.

Moses strongly advises that the people just stick with the Torah.

Jan W. thank you for such a clear overview of the Pentateuch . I too have used it for my OT Exegesis assignment. i have used your resources before when preparing a Bible Study. Thank you for sharing your gifts of teaching it has been a blessing .

Superb presentation illustration of The Torah. Use it for my Exegesis assignment of the Book of Genesis and The Pentateuch. Thank you and God bless your ministry.

Great summary. Well done. God bless you!

You do a fantastic job of illustrating the Bible. i use them for our own Bible study like passing on the word.

Keep up the good work and thank you.

- Bible Books

- Bible characters

- Bible facts

- Bible materials

- Bible topics

Recent Posts

- Interesting Facts about the Bible

- Logos Bible Software 10 review: Do you REALLY need it?

- Who Was Herod? Wait… There Were How Many Herods?!

- 16 Facts About King David

- Moses: The Old Testament’s Greatest Prophet

Privacy Overview

The story of the ANZAC Torah and how it survived

From the battles of yesteryear to the present-day defenders of our precious freedom, the story of the anzac torah embodies the enduring spirit of jewish heroism..

Rabbi Friedman throughout Gallipoli Campaign

Trending Topics:

- How to Count the Omer

- Say Kaddish Daily

The Written Torah and the Oral Torah

According to Jewish tradition, two Torahs were received on Mount Sinai -- one written, and one passed down orally for generations.

By My Jewish Learning

The scroll read in synagogue consists of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible — Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. Along with the latter books of the Prophets and the Writings — 24 books in all — this is the Hebrew Bible , also known as the Written Torah, or Torah she-bich’tav in Hebrew.

But there’s another Torah, known as the Oral Torah — or Torah she-ba’al peh . The Oral Torah refers to the later works of the rabbinic period — most prominently the Mishnah and the Gemara , jointly known as the Talmud — that explain and expound upon the statutes recorded in the Written Torah. The traditional Jewish view is that both these Torahs were revealed at Mount Sinai, but the Oral Torah was passed down as oral tradition (hence the name) until the destruction of the Second Temple in the early part of the Common Era, when fear of it being lost forever led to it being committed to writing for the first time.

The classic statement of the authority of the Oral Torah is found in the first mishnah in Avot 1:1: “Moses received the Torah at Sinai and transmitted it to Joshua, Joshua to the elders, and the elders to the prophets, and the prophets to the Men of the Great Assembly.” This statement was meant to establish that the traditions practiced during the time of the Mishnah were not human creations, but traced their authority back to Sinai. In the Middle Ages, Maimonides stated this quite explicitly in his Introduction to the Mishnah :

Know that each commandment that the Holy One, blessed be He, gave to Moshe, our teacher – peace be upon him – was given to him with its explanation. He would say to him the commandment and afterward tell him its explanation and content; and [so too with] everything that is included in the Book of the Torah.

The Oral Torah is crucial to the normative practice of Judaism today. The prescriptions for daily life found in the Bible are typically cryptic, vague, and even contradictory. Some are completely indecipherable on their own. The Oral Law expounds at great length on these sources, providing a vast literature that translates scriptural sources into a guide for daily living.

For example, the Tefillin that some Jews wear during prayer on weekday mornings is derived from a handful of biblical verses that refer to the binding of “signs” and “symbols” on the arm and between the eyes. From those sources, later rabbis derived a detailed set of practices — determining that those signs and symbols are specific biblical verses inscribed on parchment, sealed in wooden boxes, and bound to the body with leather straps. They determined a whole host of requirements about how these items should be constructed, standards for what make them ritually appropriate, and when and how to put them on. None of this would have been obvious from the biblical verses alone.

Or consider one of the most expansive and detailed areas of Jewish law: the regulations around dietary practice, known as kashrut . The Written Torah states twice, in Exodus 23:19 and Deuteronomy 14:21, that it is forbidden to “boil a kid in its mother’s milk.” Without further elaboration, one might understand those verses to be proscribing only the cooking of a young goat in the milk of its mother. But the Oral Torah explains that these verses indicate a vast array of practices , including the complete ban on eating any kind of land animal with any kind of dairy product, the requirement of separate sets of cooking equipment and serving utensils for meat and dairy, and the obligation to wait some period of time after eating meat before eating dairy. None of these rules would have been obvious from the Written Torah alone.

The laws promulgated in the Oral Law take a variety of forms. Some are explanations and details of laws derived directly from interpretations of Torah verses. These are known by the Aramaic term d’oraita — literally “of the Torah” — and are considered as binding as if they were explicitly detailed in the Written Torah. Others are laws known as d’rabbanan — or “of the rabbis.” These are laws that were legislated by the rabbis and are also considered obligatory by observant Jews, though transgressing them doesn’t carry the same severity as transgressing a d’oraita law. There are two types of d’rabbanan laws : A gezerah (literally “fence”), which was imposed as a guard against violating a more serious prohibition, such as the ban on touching objects used to perform forbidden actions on the Sabbath; and a takkanah (literally “remedy” or “fixing”), established to fix a defect in the law or for some other purpose, such as the celebration of the holiday of Hanukkah.

Though the Oral Law is essential to the normative practice of Judaism, it was not universally accepted — neither in antiquity nor today. In ancient times, the Sadducees famously rejected the authority of oral traditions. In modern times, the tiny Karaite community rejects them as well, relying solely on the Written Torah to formulate their customs. This results in Karaites engaging in many practices — such as prostration during prayer and avoiding the burning (not merely the lighting) of flames on Shabbat — that Jews do not observe.

Among modern Jews, however, religious life would be unrecognizable without the traditions recorded in the Oral Law, though the various denominations still differ significantly in their views of it.

For Orthodox Jews, the obligations recorded in the Oral Law are as binding as those recorded in the Written Torah. In this view, the laws articulated by the rabbis of the Talmud — and those who later codified them systematically in works like the Mishneh Torah and the Shulchan Aruch — were not merely legislating, but deducing law that had always been practiced going back to Sinai. The rabbis of the Gemara were scrupulous about rooting the sources for their teachings in scriptural verses and/or received traditions so as to buttress their legitimacy. As such, the Oral Law has the status of a direct divine command among Orthodox Jews.

Liberal Jews take a somewhat different approach. As a general rule, Reform Judaism does not accept the binding nature of Jewish law, or halacha, seeing the Oral Law as the product of human beings operating within the assumptions and beliefs of a specific historical moment rather than an extension of divine revelation. Conservative Judaism officially accepts the binding nature of the oral tradition, but finds much more flexibility within its strictures than Orthodox Jews and claims for modern rabbis greater authority to depart from rabbinic rulings made centuries ago.

Pronounced: ah-VOTE, Origin: Hebrew, fathers or parents, usually refering to the biblical Patriarchs.

Pronounced: MISH-nuh, Origin: Hebrew, code of Jewish law compiled in the first centuries of the Common Era. Together with the Gemara, it makes up the Talmud.

Pronounced: TALL-mud, Origin: Hebrew, the set of teachings and commentaries on the Torah that form the basis for Jewish law. Comprised of the Mishnah and the Gemara, it contains the opinions of thousands of rabbis from different periods in Jewish history.

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.

Join Our Newsletter

Empower your Jewish discovery, daily

Discover More

Tractate Kiddushin

Kiddushin 66

Murdering the sages.

Tractate Gittin

Returning a stolen beam.

Full faith and credit.

COMMENTS

The Torah's stories, laws and poetry stand at the center of Jewish culture. They chronicle God's creation of the world, the selection and growth of the family of Abraham and Sarah in relationship to God in the land of Canaan, the exile and redemption from Egypt of that "family-become-nation" known as Israel, and their travels through the desert until they return to the land of Canaan.

The following essays explore the nature and functions of the Torah and the significance of the revelation at Sinai, on Sivan 6 in the year 2448 from creation (1313 BCE), at which G‑d granted the Torah to the people of Israel. "The world is sustained by three things," says Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel in Ethics of the Fathers. "Law, truth ...

Torah in 24 Books. The Five Books of Moses are actually one section of a collection of works which is also called Torah, but otherwise known as Tanach (תנ״ך).. Tanach is an acronym of the words:. Torah: Chumash (Five Books of Moses) —as above Nevi'im (Prophets) Ketuvim (Writings, such as Psalms, Lamentations and Proverbs). All the books of Torah are divine works, yet the Chumash holds ...

The Torah is our mandate as a people, the marriage contract of our special relationship with G‑d as His chosen "kingdom of priests and holy nation." But it is not only that: to the Jew, the Torah is nothing less than the basis and objective of all existence. In the words of the Midrash: " G‑d made a condition with the work of creation: if ...

The Torah (/ ˈ t ɔːr ə, ˈ t oʊ r ə /; Biblical Hebrew: תּוֹרָה Tōrā, "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. The Torah is known as the Pentateuch (/ ˈ p ɛ n t ə tj uː k /) or the Five Books of Moses by Christians.It is also known as the ...

His proof for this interpretation comes from the Torah's self-description with which we began this essay. The story the Torah tells us about itself is that the way of life it prescribes for the Jewish people is meant to be the envy of the world. People are meant to encounter an observant Jew and to say, "This seems like the most fantastic ...

A d'var Torah (a word of Torah) is a talk or essay based on the parashah (the weekly Torah portion). Especially at times of loneliness, distress, indecision or other personal difficulties, you may find it helpful to read and interpret the Torah portion with a particular focus on how the thoughts and actions of our foremothers and forefathers—intensely human characters—might help you deal ...

The Torah that Ezra restored, however, has all of the signs of imperfection and human composition that the critics have identified, but the Torah is nonetheless the best restoration possible. Halivni's solution acknowledges the arguments of the critics, while affirming a faith in God's revelation of real objective content to the people of ...

Short (500-1,000 words) written commentaries — each written by a different rabbi — relating the week's Torah portion to issues of disabilities and special needs in education. TheTorah.com. Extensive trove of essays and academic commentaries on the weekly portion, written by professors and scholars of Jewish studies.

In his famous essay on Moses, Asher Ginsberg (Ahad Ha'am 1856-1927), an influential Zionist thinker, recasts the revelation at the burning bush as Moses encountering his internal voice. ... God forgives Israel but erases Moses from the Torah portion of Tetzaveh anyway because the curse of a Torah scholar always comes true. Here is the story ...

A d'var Torah (a word of Torah) is a talk or essay based on the parashah (the weekly Torah portion). Especially at times of loneliness, distress, indecision or other personal difficulties, you may find it helpful to read and interpret the Torah portion with a particular focus on how the thoughts and actions of our foremothers and forefathers—intensely human characters—might help you deal ...

Essays and criticism on Torah - Critical Essays. (Also known as the Pentateuch, the Five Books of Moses, Hummash, Mikra, and Law.) Hebrew history.

Tanakh (the Hebrew Bible) is Judaism's foundational text. The word "Tanakh" is an acronym of its three parts: Torah (The Five Books of Moses), Nevi'im (Prophets), and Ketuvim (Writings). It contains stories, law, poetry, and teachings about God and humanity. ... 21st-century collection of Hebrew essays on the weekly Torah portion that ...

Scholarship on the Torah portion, Jewish holidays, and questions of faith: Torah from Sinai, Torah from Heaven, Biblical criticism and Documentary Hypothesis. Donate. Newsletter. ... Latest Essays. Israel-Hamas War. Blog. Op-ed. Interview. Featured Post. God Doesn't Come Down to Earth Lower than Ten. Blog. More. Browse Topics. Resource Guide ...

Torah (תּוֹרָה) The word bible is of Greek origin, possibly a reference to Biblia, a historic port city in modern-day Lebanon that was widely known in ancient times for the superb paper it exported to many parts of the world, including Greece. Bible, then, is a reference to the medium of the book itself, a static form originally designed ...

Over my thirty plus years of teaching biblical criticism, or, as I prefer to call it, the contextual approach to the Bible, [1] I have seen a wide spectrum of reactions by students to the academic finding that the Torah developed over time. For many, myself included (see my essay, "On Becoming A Critical Torah Scholar"), this approach enriches our appreciation of Torah and Judaism.

Or buy the volumes separately: Vol.1: Genesis and Exodus, Vol. 2:Leviticus, Numbers & Deuteronomy. Collectively, Rabbi Shai Held's Torah essays—2 essays for each weekly portion— in The Heart of Torah, Volume 1 (Genesis and Exodus) and Volume II (Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy) open new horizons in the world of Jewish biblical commentary.

The Written Torah, mentiones each of the Commandments, or Mitzvos, only in passing or by allusion. The Oral Law fills in the gaps. Here is an example: "And you shall tie them as a sign on your arm and for ( Totafos) between your eyes." (Deut. 6 8) This is the source for the Mitzvah of Tefillin (phylacteries - if that's any clearer), but ...

The Torah, which comes from the Hebrew word for "law". The Pentateuch, which comes from a means "five-book work," or "five-fold book". The Books of Moses (also "the Book of Moses," or simply "Moses"), who's traditionally credited as the primary source of these books. The Law of Moses, a blend of the first and third names.

After the war, rabbi Friedman returned home, but the journey of the ANZAC Torah continued, albeit with twists and turns. Rabbi Friedman passed away in 1939, and somehow, the Sefer Torah found its ...

One of my seminary professors used to say, "When I pray, I speak to God. When I study Torah, I keep quiet and let God speak to me.". If worship is the effort to connect with God, Judaism affirms that we don't have to do all the work ourselves. God is prepared to meet us halfway. By immersing ourselves in Torah, we transport ourselves back ...

There are too many papers hindering the hidden attraction. Those pages are preventing the magnet from doing what the magnet does best. Peel away what is unnecessary from that stack of information, misinformation, and disinformation and suddenly the magnet magically wakes up. If only we give ourselves a chance, then we too are holy.

Torah Essays. The Torah: The Five Books Of The Torah 314 Words | 2 Pages. The 5 books of the Torah are central documents in Judaism and the Torah, both written and oral is utilised by the Jewish adherents through many practices, prayers and rituals. The Torah records the expression of the covenantal relationship between God and his chosen ...

Uploaded by Crhodes8828. Charleston Southern University The Message of the Torah An Essay Submitted to Dr. Peter Link, JR. In Partial Fulfillment of CHST 111: Survey of the Old Testament By Caselyhn Rhodes September 21, 2020. The Torah, also known as the book of Moses, or the Pentateuch, refers to the first five books of the Old Testament.

The classic statement of the authority of the Oral Torah is found in the first mishnah in Avot 1:1: "Moses received the Torah at Sinai and transmitted it to Joshua, Joshua to the elders, and the elders to the prophets, and the prophets to the Men of the Great Assembly.". This statement was meant to establish that the traditions practiced ...

In the Torah, as well as the Talmud, multiple references to antisemitism are found. ... This essay was a disturbing, honest history. 1. Reply. Lauren Roth 10 hours ago Excellent article. Thank you. 1. Reply. Dvirah 17 hours ago What the Koran forgets to say is that the Jew behind the tree is holding a gun at the ready - B"H! 0.

Simchat Torah: October 23-25, 2024. Following the seven joyous days of Sukkot, we come to the happy holiday of Shemini Atzeret/Simchat Torah. In the diaspora, the first day is known by its biblical name, Shemini Atzeret. We still dwell in the sukkah, but without a blessing. Yizkor, the memorial for the departed, is also said on this day.