How to Write an Essay

Use the links below to jump directly to any section of this guide:

Essay Writing Fundamentals

How to prepare to write an essay, how to edit an essay, how to share and publish your essays, how to get essay writing help, how to find essay writing inspiration, resources for teaching essay writing.

Essays, short prose compositions on a particular theme or topic, are the bread and butter of academic life. You write them in class, for homework, and on standardized tests to show what you know. Unlike other kinds of academic writing (like the research paper) and creative writing (like short stories and poems), essays allow you to develop your original thoughts on a prompt or question. Essays come in many varieties: they can be expository (fleshing out an idea or claim), descriptive, (explaining a person, place, or thing), narrative (relating a personal experience), or persuasive (attempting to win over a reader). This guide is a collection of dozens of links about academic essay writing that we have researched, categorized, and annotated in order to help you improve your essay writing.

Essays are different from other forms of writing; in turn, there are different kinds of essays. This section contains general resources for getting to know the essay and its variants. These resources introduce and define the essay as a genre, and will teach you what to expect from essay-based assessments.

Purdue OWL Online Writing Lab

One of the most trusted academic writing sites, Purdue OWL provides a concise introduction to the four most common types of academic essays.

"The Essay: History and Definition" (ThoughtCo)

This snappy article from ThoughtCo talks about the origins of the essay and different kinds of essays you might be asked to write.

"What Is An Essay?" Video Lecture (Coursera)

The University of California at Irvine's free video lecture, available on Coursera, tells you everything you need to know about the essay.

Wikipedia Article on the "Essay"

Wikipedia's article on the essay is comprehensive, providing both English-language and global perspectives on the essay form. Learn about the essay's history, forms, and styles.

"Understanding College and Academic Writing" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

This list of common academic writing assignments (including types of essay prompts) will help you know what to expect from essay-based assessments.

Before you start writing your essay, you need to figure out who you're writing for (audience), what you're writing about (topic/theme), and what you're going to say (argument and thesis). This section contains links to handouts, chapters, videos and more to help you prepare to write an essay.

How to Identify Your Audience

"Audience" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This handout provides questions you can ask yourself to determine the audience for an academic writing assignment. It also suggests strategies for fitting your paper to your intended audience.

"Purpose, Audience, Tone, and Content" (Univ. of Minnesota Libraries)

This extensive book chapter from Writing for Success , available online through Minnesota Libraries Publishing, is followed by exercises to try out your new pre-writing skills.

"Determining Audience" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

This guide from a community college's writing center shows you how to know your audience, and how to incorporate that knowledge in your thesis statement.

"Know Your Audience" ( Paper Rater Blog)

This short blog post uses examples to show how implied audiences for essays differ. It reminds you to think of your instructor as an observer, who will know only the information you pass along.

How to Choose a Theme or Topic

"Research Tutorial: Developing Your Topic" (YouTube)

Take a look at this short video tutorial from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill to understand the basics of developing a writing topic.

"How to Choose a Paper Topic" (WikiHow)

This simple, step-by-step guide (with pictures!) walks you through choosing a paper topic. It starts with a detailed description of brainstorming and ends with strategies to refine your broad topic.

"How to Read an Assignment: Moving From Assignment to Topic" (Harvard College Writing Center)

Did your teacher give you a prompt or other instructions? This guide helps you understand the relationship between an essay assignment and your essay's topic.

"Guidelines for Choosing a Topic" (CliffsNotes)

This study guide from CliffsNotes both discusses how to choose a topic and makes a useful distinction between "topic" and "thesis."

How to Come Up with an Argument

"Argument" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

Not sure what "argument" means in the context of academic writing? This page from the University of North Carolina is a good place to start.

"The Essay Guide: Finding an Argument" (Study Hub)

This handout explains why it's important to have an argument when beginning your essay, and provides tools to help you choose a viable argument.

"Writing a Thesis and Making an Argument" (University of Iowa)

This page from the University of Iowa's Writing Center contains exercises through which you can develop and refine your argument and thesis statement.

"Developing a Thesis" (Harvard College Writing Center)

This page from Harvard's Writing Center collates some helpful dos and don'ts of argumentative writing, from steps in constructing a thesis to avoiding vague and confrontational thesis statements.

"Suggestions for Developing Argumentative Essays" (Berkeley Student Learning Center)

This page offers concrete suggestions for each stage of the essay writing process, from topic selection to drafting and editing.

How to Outline your Essay

"Outlines" (Univ. of North Carolina at Chapel Hill via YouTube)

This short video tutorial from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill shows how to group your ideas into paragraphs or sections to begin the outlining process.

"Essay Outline" (Univ. of Washington Tacoma)

This two-page handout by a university professor simply defines the parts of an essay and then organizes them into an example outline.

"Types of Outlines and Samples" (Purdue OWL Online Writing Lab)

Purdue OWL gives examples of diverse outline strategies on this page, including the alphanumeric, full sentence, and decimal styles.

"Outlining" (Harvard College Writing Center)

Once you have an argument, according to this handout, there are only three steps in the outline process: generalizing, ordering, and putting it all together. Then you're ready to write!

"Writing Essays" (Plymouth Univ.)

This packet, part of Plymouth University's Learning Development series, contains descriptions and diagrams relating to the outlining process.

"How to Write A Good Argumentative Essay: Logical Structure" (Criticalthinkingtutorials.com via YouTube)

This longer video tutorial gives an overview of how to structure your essay in order to support your argument or thesis. It is part of a longer course on academic writing hosted on Udemy.

Now that you've chosen and refined your topic and created an outline, use these resources to complete the writing process. Most essays contain introductions (which articulate your thesis statement), body paragraphs, and conclusions. Transitions facilitate the flow from one paragraph to the next so that support for your thesis builds throughout the essay. Sources and citations show where you got the evidence to support your thesis, which ensures that you avoid plagiarism.

How to Write an Introduction

"Introductions" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page identifies the role of the introduction in any successful paper, suggests strategies for writing introductions, and warns against less effective introductions.

"How to Write A Good Introduction" (Michigan State Writing Center)

Beginning with the most common missteps in writing introductions, this guide condenses the essentials of introduction composition into seven points.

"The Introductory Paragraph" (ThoughtCo)

This blog post from academic advisor and college enrollment counselor Grace Fleming focuses on ways to grab your reader's attention at the beginning of your essay.

"Introductions and Conclusions" (Univ. of Toronto)

This guide from the University of Toronto gives advice that applies to writing both introductions and conclusions, including dos and don'ts.

"How to Write Better Essays: No One Does Introductions Properly" ( The Guardian )

This news article interviews UK professors on student essay writing; they point to introductions as the area that needs the most improvement.

How to Write a Thesis Statement

"Writing an Effective Thesis Statement" (YouTube)

This short, simple video tutorial from a college composition instructor at Tulsa Community College explains what a thesis statement is and what it does.

"Thesis Statement: Four Steps to a Great Essay" (YouTube)

This fantastic tutorial walks you through drafting a thesis, using an essay prompt on Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter as an example.

"How to Write a Thesis Statement" (WikiHow)

This step-by-step guide (with pictures!) walks you through coming up with, writing, and editing a thesis statement. It invites you think of your statement as a "working thesis" that can change.

"How to Write a Thesis Statement" (Univ. of Indiana Bloomington)

Ask yourself the questions on this page, part of Indiana Bloomington's Writing Tutorial Services, when you're writing and refining your thesis statement.

"Writing Tips: Thesis Statements" (Univ. of Illinois Center for Writing Studies)

This page gives plentiful examples of good to great thesis statements, and offers questions to ask yourself when formulating a thesis statement.

How to Write Body Paragraphs

"Body Paragraph" (Brightstorm)

This module of a free online course introduces you to the components of a body paragraph. These include the topic sentence, information, evidence, and analysis.

"Strong Body Paragraphs" (Washington Univ.)

This handout from Washington's Writing and Research Center offers in-depth descriptions of the parts of a successful body paragraph.

"Guide to Paragraph Structure" (Deakin Univ.)

This handout is notable for color-coding example body paragraphs to help you identify the functions various sentences perform.

"Writing Body Paragraphs" (Univ. of Minnesota Libraries)

The exercises in this section of Writing for Success will help you practice writing good body paragraphs. It includes guidance on selecting primary support for your thesis.

"The Writing Process—Body Paragraphs" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

The information and exercises on this page will familiarize you with outlining and writing body paragraphs, and includes links to more information on topic sentences and transitions.

"The Five-Paragraph Essay" (ThoughtCo)

This blog post discusses body paragraphs in the context of one of the most common academic essay types in secondary schools.

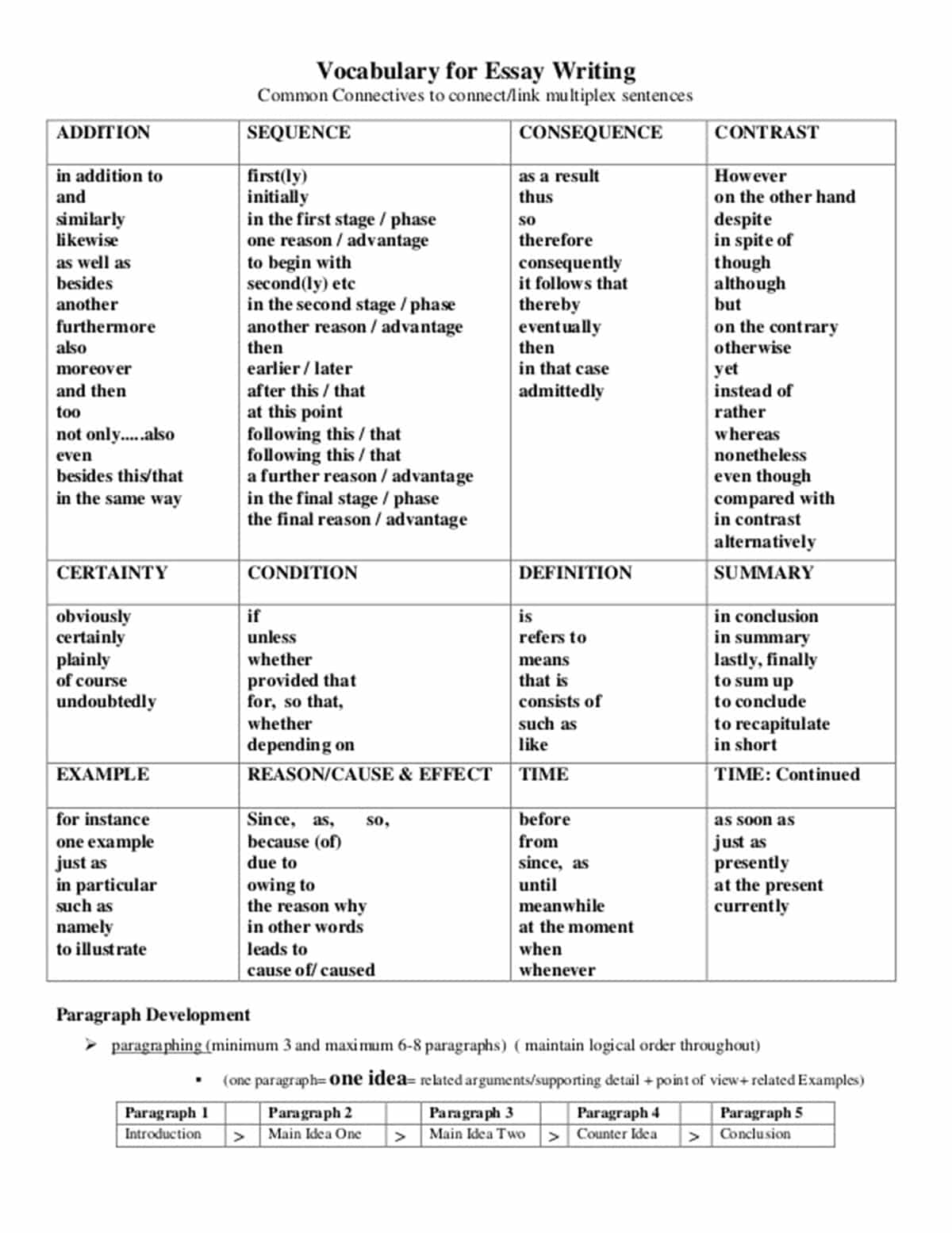

How to Use Transitions

"Transitions" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill explains what a transition is, and how to know if you need to improve your transitions.

"Using Transitions Effectively" (Washington Univ.)

This handout defines transitions, offers tips for using them, and contains a useful list of common transitional words and phrases grouped by function.

"Transitions" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

This page compares paragraphs without transitions to paragraphs with transitions, and in doing so shows how important these connective words and phrases are.

"Transitions in Academic Essays" (Scribbr)

This page lists four techniques that will help you make sure your reader follows your train of thought, including grouping similar information and using transition words.

"Transitions" (El Paso Community College)

This handout shows example transitions within paragraphs for context, and explains how transitions improve your essay's flow and voice.

"Make Your Paragraphs Flow to Improve Writing" (ThoughtCo)

This blog post, another from academic advisor and college enrollment counselor Grace Fleming, talks about transitions and other strategies to improve your essay's overall flow.

"Transition Words" (smartwords.org)

This handy word bank will help you find transition words when you're feeling stuck. It's grouped by the transition's function, whether that is to show agreement, opposition, condition, or consequence.

How to Write a Conclusion

"Parts of An Essay: Conclusions" (Brightstorm)

This module of a free online course explains how to conclude an academic essay. It suggests thinking about the "3Rs": return to hook, restate your thesis, and relate to the reader.

"Essay Conclusions" (Univ. of Maryland University College)

This overview of the academic essay conclusion contains helpful examples and links to further resources for writing good conclusions.

"How to End An Essay" (WikiHow)

This step-by-step guide (with pictures!) by an English Ph.D. walks you through writing a conclusion, from brainstorming to ending with a flourish.

"Ending the Essay: Conclusions" (Harvard College Writing Center)

This page collates useful strategies for writing an effective conclusion, and reminds you to "close the discussion without closing it off" to further conversation.

How to Include Sources and Citations

"Research and Citation Resources" (Purdue OWL Online Writing Lab)

Purdue OWL streamlines information about the three most common referencing styles (MLA, Chicago, and APA) and provides examples of how to cite different resources in each system.

EasyBib: Free Bibliography Generator

This online tool allows you to input information about your source and automatically generate citations in any style. Be sure to select your resource type before clicking the "cite it" button.

CitationMachine

Like EasyBib, this online tool allows you to input information about your source and automatically generate citations in any style.

Modern Language Association Handbook (MLA)

Here, you'll find the definitive and up-to-date record of MLA referencing rules. Order through the link above, or check to see if your library has a copy.

Chicago Manual of Style

Here, you'll find the definitive and up-to-date record of Chicago referencing rules. You can take a look at the table of contents, then choose to subscribe or start a free trial.

How to Avoid Plagiarism

"What is Plagiarism?" (plagiarism.org)

This nonprofit website contains numerous resources for identifying and avoiding plagiarism, and reminds you that even common activities like copying images from another website to your own site may constitute plagiarism.

"Plagiarism" (University of Oxford)

This interactive page from the University of Oxford helps you check for plagiarism in your work, making it clear how to avoid citing another person's work without full acknowledgement.

"Avoiding Plagiarism" (MIT Comparative Media Studies)

This quick guide explains what plagiarism is, what its consequences are, and how to avoid it. It starts by defining three words—quotation, paraphrase, and summary—that all constitute citation.

"Harvard Guide to Using Sources" (Harvard Extension School)

This comprehensive website from Harvard brings together articles, videos, and handouts about referencing, citation, and plagiarism.

Grammarly contains tons of helpful grammar and writing resources, including a free tool to automatically scan your essay to check for close affinities to published work.

Noplag is another popular online tool that automatically scans your essay to check for signs of plagiarism. Simply copy and paste your essay into the box and click "start checking."

Once you've written your essay, you'll want to edit (improve content), proofread (check for spelling and grammar mistakes), and finalize your work until you're ready to hand it in. This section brings together tips and resources for navigating the editing process.

"Writing a First Draft" (Academic Help)

This is an introduction to the drafting process from the site Academic Help, with tips for getting your ideas on paper before editing begins.

"Editing and Proofreading" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page provides general strategies for revising your writing. They've intentionally left seven errors in the handout, to give you practice in spotting them.

"How to Proofread Effectively" (ThoughtCo)

This article from ThoughtCo, along with those linked at the bottom, help describe common mistakes to check for when proofreading.

"7 Simple Edits That Make Your Writing 100% More Powerful" (SmartBlogger)

This blog post emphasizes the importance of powerful, concise language, and reminds you that even your personal writing heroes create clunky first drafts.

"Editing Tips for Effective Writing" (Univ. of Pennsylvania)

On this page from Penn's International Relations department, you'll find tips for effective prose, errors to watch out for, and reminders about formatting.

"Editing the Essay" (Harvard College Writing Center)

This article, the first of two parts, gives you applicable strategies for the editing process. It suggests reading your essay aloud, removing any jargon, and being unafraid to remove even "dazzling" sentences that don't belong.

"Guide to Editing and Proofreading" (Oxford Learning Institute)

This handout from Oxford covers the basics of editing and proofreading, and reminds you that neither task should be rushed.

In addition to plagiarism-checkers, Grammarly has a plug-in for your web browser that checks your writing for common mistakes.

After you've prepared, written, and edited your essay, you might want to share it outside the classroom. This section alerts you to print and web opportunities to share your essays with the wider world, from online writing communities and blogs to published journals geared toward young writers.

Sharing Your Essays Online

Go Teen Writers

Go Teen Writers is an online community for writers aged 13 - 19. It was founded by Stephanie Morrill, an author of contemporary young adult novels.

Tumblr is a blogging website where you can share your writing and interact with other writers online. It's easy to add photos, links, audio, and video components.

Writersky provides an online platform for publishing and reading other youth writers' work. Its current content is mostly devoted to fiction.

Publishing Your Essays Online

This teen literary journal publishes in print, on the web, and (more frequently), on a blog. It is committed to ensuring that "teens see their authentic experience reflected on its pages."

The Matador Review

This youth writing platform celebrates "alternative," unconventional writing. The link above will take you directly to the site's "submissions" page.

Teen Ink has a website, monthly newsprint magazine, and quarterly poetry magazine promoting the work of young writers.

The largest online reading platform, Wattpad enables you to publish your work and read others' work. Its inline commenting feature allows you to share thoughts as you read along.

Publishing Your Essays in Print

Canvas Teen Literary Journal

This quarterly literary magazine is published for young writers by young writers. They accept many kinds of writing, including essays.

The Claremont Review

This biannual international magazine, first published in 1992, publishes poetry, essays, and short stories from writers aged 13 - 19.

Skipping Stones

This young writers magazine, founded in 1988, celebrates themes relating to ecological and cultural diversity. It publishes poems, photos, articles, and stories.

The Telling Room

This nonprofit writing center based in Maine publishes children's work on their website and in book form. The link above directs you to the site's submissions page.

Essay Contests

Scholastic Arts and Writing Awards

This prestigious international writing contest for students in grades 7 - 12 has been committed to "supporting the future of creativity since 1923."

Society of Professional Journalists High School Essay Contest

An annual essay contest on the theme of journalism and media, the Society of Professional Journalists High School Essay Contest awards scholarships up to $1,000.

National YoungArts Foundation

Here, you'll find information on a government-sponsored writing competition for writers aged 15 - 18. The foundation welcomes submissions of creative nonfiction, novels, scripts, poetry, short story and spoken word.

Signet Classics Student Scholarship Essay Contest

With prompts on a different literary work each year, this competition from Signet Classics awards college scholarships up to $1,000.

"The Ultimate Guide to High School Essay Contests" (CollegeVine)

See this handy guide from CollegeVine for a list of more competitions you can enter with your academic essay, from the National Council of Teachers of English Achievement Awards to the National High School Essay Contest by the U.S. Institute of Peace.

Whether you're struggling to write academic essays or you think you're a pro, there are workshops and online tools that can help you become an even better writer. Even the most seasoned writers encounter writer's block, so be proactive and look through our curated list of resources to combat this common frustration.

Online Essay-writing Classes and Workshops

"Getting Started with Essay Writing" (Coursera)

Coursera offers lots of free, high-quality online classes taught by college professors. Here's one example, taught by instructors from the University of California Irvine.

"Writing and English" (Brightstorm)

Brightstorm's free video lectures are easy to navigate by topic. This unit on the parts of an essay features content on the essay hook, thesis, supporting evidence, and more.

"How to Write an Essay" (EdX)

EdX is another open online university course website with several two- to five-week courses on the essay. This one is geared toward English language learners.

Writer's Digest University

This renowned writers' website offers online workshops and interactive tutorials. The courses offered cover everything from how to get started through how to get published.

Writing.com

Signing up for this online writer's community gives you access to helpful resources as well as an international community of writers.

How to Overcome Writer's Block

"Symptoms and Cures for Writer's Block" (Purdue OWL)

Purdue OWL offers a list of signs you might have writer's block, along with ways to overcome it. Consider trying out some "invention strategies" or ways to curb writing anxiety.

"Overcoming Writer's Block: Three Tips" ( The Guardian )

These tips, geared toward academic writing specifically, are practical and effective. The authors advocate setting realistic goals, creating dedicated writing time, and participating in social writing.

"Writing Tips: Strategies for Overcoming Writer's Block" (Univ. of Illinois)

This page from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign's Center for Writing Studies acquaints you with strategies that do and do not work to overcome writer's block.

"Writer's Block" (Univ. of Toronto)

Ask yourself the questions on this page; if the answer is "yes," try out some of the article's strategies. Each question is accompanied by at least two possible solutions.

If you have essays to write but are short on ideas, this section's links to prompts, example student essays, and celebrated essays by professional writers might help. You'll find writing prompts from a variety of sources, student essays to inspire you, and a number of essay writing collections.

Essay Writing Prompts

"50 Argumentative Essay Topics" (ThoughtCo)

Take a look at this list and the others ThoughtCo has curated for different kinds of essays. As the author notes, "a number of these topics are controversial and that's the point."

"401 Prompts for Argumentative Writing" ( New York Times )

This list (and the linked lists to persuasive and narrative writing prompts), besides being impressive in length, is put together by actual high school English teachers.

"SAT Sample Essay Prompts" (College Board)

If you're a student in the U.S., your classroom essay prompts are likely modeled on the prompts in U.S. college entrance exams. Take a look at these official examples from the SAT.

"Popular College Application Essay Topics" (Princeton Review)

This page from the Princeton Review dissects recent Common Application essay topics and discusses strategies for answering them.

Example Student Essays

"501 Writing Prompts" (DePaul Univ.)

This nearly 200-page packet, compiled by the LearningExpress Skill Builder in Focus Writing Team, is stuffed with writing prompts, example essays, and commentary.

"Topics in English" (Kibin)

Kibin is a for-pay essay help website, but its example essays (organized by topic) are available for free. You'll find essays on everything from A Christmas Carol to perseverance.

"Student Writing Models" (Thoughtful Learning)

Thoughtful Learning, a website that offers a variety of teaching materials, provides sample student essays on various topics and organizes them by grade level.

"Five-Paragraph Essay" (ThoughtCo)

In this blog post by a former professor of English and rhetoric, ThoughtCo brings together examples of five-paragraph essays and commentary on the form.

The Best Essay Writing Collections

The Best American Essays of the Century by Joyce Carol Oates (Amazon)

This collection of American essays spanning the twentieth century was compiled by award winning author and Princeton professor Joyce Carol Oates.

The Best American Essays 2017 by Leslie Jamison (Amazon)

Leslie Jamison, the celebrated author of essay collection The Empathy Exams , collects recent, high-profile essays into a single volume.

The Art of the Personal Essay by Phillip Lopate (Amazon)

Documentary writer Phillip Lopate curates this historical overview of the personal essay's development, from the classical era to the present.

The White Album by Joan Didion (Amazon)

This seminal essay collection was authored by one of the most acclaimed personal essayists of all time, American journalist Joan Didion.

Consider the Lobster by David Foster Wallace (Amazon)

Read this famous essay collection by David Foster Wallace, who is known for his experimentation with the essay form. He pushed the boundaries of personal essay, reportage, and political polemic.

"50 Successful Harvard Application Essays" (Staff of the The Harvard Crimson )

If you're looking for examples of exceptional college application essays, this volume from Harvard's daily student newspaper is one of the best collections on the market.

Are you an instructor looking for the best resources for teaching essay writing? This section contains resources for developing in-class activities and student homework assignments. You'll find content from both well-known university writing centers and online writing labs.

Essay Writing Classroom Activities for Students

"In-class Writing Exercises" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page lists exercises related to brainstorming, organizing, drafting, and revising. It also contains suggestions for how to implement the suggested exercises.

"Teaching with Writing" (Univ. of Minnesota Center for Writing)

Instructions and encouragement for using "freewriting," one-minute papers, logbooks, and other write-to-learn activities in the classroom can be found here.

"Writing Worksheets" (Berkeley Student Learning Center)

Berkeley offers this bank of writing worksheets to use in class. They are nested under headings for "Prewriting," "Revision," "Research Papers" and more.

"Using Sources and Avoiding Plagiarism" (DePaul University)

Use these activities and worksheets from DePaul's Teaching Commons when instructing students on proper academic citation practices.

Essay Writing Homework Activities for Students

"Grammar and Punctuation Exercises" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

These five interactive online activities allow students to practice editing and proofreading. They'll hone their skills in correcting comma splices and run-ons, identifying fragments, using correct pronoun agreement, and comma usage.

"Student Interactives" (Read Write Think)

Read Write Think hosts interactive tools, games, and videos for developing writing skills. They can practice organizing and summarizing, writing poetry, and developing lines of inquiry and analysis.

This free website offers writing and grammar activities for all grade levels. The lessons are designed to be used both for large classes and smaller groups.

"Writing Activities and Lessons for Every Grade" (Education World)

Education World's page on writing activities and lessons links you to more free, online resources for learning how to "W.R.I.T.E.": write, revise, inform, think, and edit.

- PDFs for all 136 Lit Terms we cover

- Downloads of 1924 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 40,556 quotes across 1924 books

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

Need something? Request a new guide .

How can we improve? Share feedback .

LitCharts is hiring!

- If you are writing in a new discipline, you should always make sure to ask about conventions and expectations for introductions, just as you would for any other aspect of the essay. For example, while it may be acceptable to write a two-paragraph (or longer) introduction for your papers in some courses, instructors in other disciplines, such as those in some Government courses, may expect a shorter introduction that includes a preview of the argument that will follow.

- In some disciplines (Government, Economics, and others), it’s common to offer an overview in the introduction of what points you will make in your essay. In other disciplines, you will not be expected to provide this overview in your introduction.

- Avoid writing a very general opening sentence. While it may be true that “Since the dawn of time, people have been telling love stories,” it won’t help you explain what’s interesting about your topic.

- Avoid writing a “funnel” introduction in which you begin with a very broad statement about a topic and move to a narrow statement about that topic. Broad generalizations about a topic will not add to your readers’ understanding of your specific essay topic.

- Avoid beginning with a dictionary definition of a term or concept you will be writing about. If the concept is complicated or unfamiliar to your readers, you will need to define it in detail later in your essay. If it’s not complicated, you can assume your readers already know the definition.

- Avoid offering too much detail in your introduction that a reader could better understand later in the paper.

- picture_as_pdf Introductions

Places on our 2024 summer school are filling fast. Don’t miss out. Enrol now to avoid disappointment

- 40 Useful Words and Phrases for Top-Notch Essays

To be truly brilliant, an essay needs to utilise the right language. You could make a great point, but if it’s not intelligently articulated, you almost needn’t have bothered.

Developing the language skills to build an argument and to write persuasively is crucial if you’re to write outstanding essays every time. In this article, we’re going to equip you with the words and phrases you need to write a top-notch essay, along with examples of how to utilise them.

It’s by no means an exhaustive list, and there will often be other ways of using the words and phrases we describe that we won’t have room to include, but there should be more than enough below to help you make an instant improvement to your essay-writing skills.

If you’re interested in developing your language and persuasive skills, Oxford Royale offers summer courses at its Oxford Summer School , Cambridge Summer School , London Summer School , San Francisco Summer School and Yale Summer School . You can study courses to learn english , prepare for careers in law , medicine , business , engineering and leadership.

General explaining

Let’s start by looking at language for general explanations of complex points.

1. In order to

Usage: “In order to” can be used to introduce an explanation for the purpose of an argument. Example: “In order to understand X, we need first to understand Y.”

2. In other words

Usage: Use “in other words” when you want to express something in a different way (more simply), to make it easier to understand, or to emphasise or expand on a point. Example: “Frogs are amphibians. In other words, they live on the land and in the water.”

3. To put it another way

Usage: This phrase is another way of saying “in other words”, and can be used in particularly complex points, when you feel that an alternative way of wording a problem may help the reader achieve a better understanding of its significance. Example: “Plants rely on photosynthesis. To put it another way, they will die without the sun.”

4. That is to say

Usage: “That is” and “that is to say” can be used to add further detail to your explanation, or to be more precise. Example: “Whales are mammals. That is to say, they must breathe air.”

5. To that end

Usage: Use “to that end” or “to this end” in a similar way to “in order to” or “so”. Example: “Zoologists have long sought to understand how animals communicate with each other. To that end, a new study has been launched that looks at elephant sounds and their possible meanings.”

Adding additional information to support a point

Students often make the mistake of using synonyms of “and” each time they want to add further information in support of a point they’re making, or to build an argument . Here are some cleverer ways of doing this.

6. Moreover

Usage: Employ “moreover” at the start of a sentence to add extra information in support of a point you’re making. Example: “Moreover, the results of a recent piece of research provide compelling evidence in support of…”

7. Furthermore

Usage:This is also generally used at the start of a sentence, to add extra information. Example: “Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that…”

8. What’s more

Usage: This is used in the same way as “moreover” and “furthermore”. Example: “What’s more, this isn’t the only evidence that supports this hypothesis.”

9. Likewise

Usage: Use “likewise” when you want to talk about something that agrees with what you’ve just mentioned. Example: “Scholar A believes X. Likewise, Scholar B argues compellingly in favour of this point of view.”

10. Similarly

Usage: Use “similarly” in the same way as “likewise”. Example: “Audiences at the time reacted with shock to Beethoven’s new work, because it was very different to what they were used to. Similarly, we have a tendency to react with surprise to the unfamiliar.”

11. Another key thing to remember

Usage: Use the phrase “another key point to remember” or “another key fact to remember” to introduce additional facts without using the word “also”. Example: “As a Romantic, Blake was a proponent of a closer relationship between humans and nature. Another key point to remember is that Blake was writing during the Industrial Revolution, which had a major impact on the world around him.”

12. As well as

Usage: Use “as well as” instead of “also” or “and”. Example: “Scholar A argued that this was due to X, as well as Y.”

13. Not only… but also

Usage: This wording is used to add an extra piece of information, often something that’s in some way more surprising or unexpected than the first piece of information. Example: “Not only did Edmund Hillary have the honour of being the first to reach the summit of Everest, but he was also appointed Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire.”

14. Coupled with

Usage: Used when considering two or more arguments at a time. Example: “Coupled with the literary evidence, the statistics paint a compelling view of…”

15. Firstly, secondly, thirdly…

Usage: This can be used to structure an argument, presenting facts clearly one after the other. Example: “There are many points in support of this view. Firstly, X. Secondly, Y. And thirdly, Z.

16. Not to mention/to say nothing of

Usage: “Not to mention” and “to say nothing of” can be used to add extra information with a bit of emphasis. Example: “The war caused unprecedented suffering to millions of people, not to mention its impact on the country’s economy.”

Words and phrases for demonstrating contrast

When you’re developing an argument, you will often need to present contrasting or opposing opinions or evidence – “it could show this, but it could also show this”, or “X says this, but Y disagrees”. This section covers words you can use instead of the “but” in these examples, to make your writing sound more intelligent and interesting.

17. However

Usage: Use “however” to introduce a point that disagrees with what you’ve just said. Example: “Scholar A thinks this. However, Scholar B reached a different conclusion.”

18. On the other hand

Usage: Usage of this phrase includes introducing a contrasting interpretation of the same piece of evidence, a different piece of evidence that suggests something else, or an opposing opinion. Example: “The historical evidence appears to suggest a clear-cut situation. On the other hand, the archaeological evidence presents a somewhat less straightforward picture of what happened that day.”

19. Having said that

Usage: Used in a similar manner to “on the other hand” or “but”. Example: “The historians are unanimous in telling us X, an agreement that suggests that this version of events must be an accurate account. Having said that, the archaeology tells a different story.”

20. By contrast/in comparison

Usage: Use “by contrast” or “in comparison” when you’re comparing and contrasting pieces of evidence. Example: “Scholar A’s opinion, then, is based on insufficient evidence. By contrast, Scholar B’s opinion seems more plausible.”

21. Then again

Usage: Use this to cast doubt on an assertion. Example: “Writer A asserts that this was the reason for what happened. Then again, it’s possible that he was being paid to say this.”

22. That said

Usage: This is used in the same way as “then again”. Example: “The evidence ostensibly appears to point to this conclusion. That said, much of the evidence is unreliable at best.”

Usage: Use this when you want to introduce a contrasting idea. Example: “Much of scholarship has focused on this evidence. Yet not everyone agrees that this is the most important aspect of the situation.”

Adding a proviso or acknowledging reservations

Sometimes, you may need to acknowledge a shortfalling in a piece of evidence, or add a proviso. Here are some ways of doing so.

24. Despite this

Usage: Use “despite this” or “in spite of this” when you want to outline a point that stands regardless of a shortfalling in the evidence. Example: “The sample size was small, but the results were important despite this.”

25. With this in mind

Usage: Use this when you want your reader to consider a point in the knowledge of something else. Example: “We’ve seen that the methods used in the 19th century study did not always live up to the rigorous standards expected in scientific research today, which makes it difficult to draw definite conclusions. With this in mind, let’s look at a more recent study to see how the results compare.”

26. Provided that

Usage: This means “on condition that”. You can also say “providing that” or just “providing” to mean the same thing. Example: “We may use this as evidence to support our argument, provided that we bear in mind the limitations of the methods used to obtain it.”

27. In view of/in light of

Usage: These phrases are used when something has shed light on something else. Example: “In light of the evidence from the 2013 study, we have a better understanding of…”

28. Nonetheless

Usage: This is similar to “despite this”. Example: “The study had its limitations, but it was nonetheless groundbreaking for its day.”

29. Nevertheless

Usage: This is the same as “nonetheless”. Example: “The study was flawed, but it was important nevertheless.”

30. Notwithstanding

Usage: This is another way of saying “nonetheless”. Example: “Notwithstanding the limitations of the methodology used, it was an important study in the development of how we view the workings of the human mind.”

Giving examples

Good essays always back up points with examples, but it’s going to get boring if you use the expression “for example” every time. Here are a couple of other ways of saying the same thing.

31. For instance

Example: “Some birds migrate to avoid harsher winter climates. Swallows, for instance, leave the UK in early winter and fly south…”

32. To give an illustration

Example: “To give an illustration of what I mean, let’s look at the case of…”

Signifying importance

When you want to demonstrate that a point is particularly important, there are several ways of highlighting it as such.

33. Significantly

Usage: Used to introduce a point that is loaded with meaning that might not be immediately apparent. Example: “Significantly, Tacitus omits to tell us the kind of gossip prevalent in Suetonius’ accounts of the same period.”

34. Notably

Usage: This can be used to mean “significantly” (as above), and it can also be used interchangeably with “in particular” (the example below demonstrates the first of these ways of using it). Example: “Actual figures are notably absent from Scholar A’s analysis.”

35. Importantly

Usage: Use “importantly” interchangeably with “significantly”. Example: “Importantly, Scholar A was being employed by X when he wrote this work, and was presumably therefore under pressure to portray the situation more favourably than he perhaps might otherwise have done.”

Summarising

You’ve almost made it to the end of the essay, but your work isn’t over yet. You need to end by wrapping up everything you’ve talked about, showing that you’ve considered the arguments on both sides and reached the most likely conclusion. Here are some words and phrases to help you.

36. In conclusion

Usage: Typically used to introduce the concluding paragraph or sentence of an essay, summarising what you’ve discussed in a broad overview. Example: “In conclusion, the evidence points almost exclusively to Argument A.”

37. Above all

Usage: Used to signify what you believe to be the most significant point, and the main takeaway from the essay. Example: “Above all, it seems pertinent to remember that…”

38. Persuasive

Usage: This is a useful word to use when summarising which argument you find most convincing. Example: “Scholar A’s point – that Constanze Mozart was motivated by financial gain – seems to me to be the most persuasive argument for her actions following Mozart’s death.”

39. Compelling

Usage: Use in the same way as “persuasive” above. Example: “The most compelling argument is presented by Scholar A.”

40. All things considered

Usage: This means “taking everything into account”. Example: “All things considered, it seems reasonable to assume that…”

How many of these words and phrases will you get into your next essay? And are any of your favourite essay terms missing from our list? Let us know in the comments below, or get in touch here to find out more about courses that can help you with your essays.

At Oxford Royale Academy, we offer a number of summer school courses for young people who are keen to improve their essay writing skills. Click here to apply for one of our courses today, including law , business , medicine and engineering .

Comments are closed.

How to Write the Perfect Essay

06 Feb, 2024 | Blog Articles , English Language Articles , Get the Edge , Humanities Articles , Writing Articles

You can keep adding to this plan, crossing bits out and linking the different bubbles when you spot connections between them. Even though you won’t have time to make a detailed plan under exam conditions, it can be helpful to draft a brief one, including a few key words, so that you don’t panic and go off topic when writing your essay.

If you don’t like the mind map format, there are plenty of others to choose from: you could make a table, a flowchart, or simply a list of bullet points.

Discover More

Thanks for signing up, step 2: have a clear structure.

Think about this while you’re planning: your essay is like an argument or a speech. It needs to have a logical structure, with all your points coming together to answer the question.

Start with the basics! It’s best to choose a few major points which will become your main paragraphs. Three main paragraphs is a good number for an exam essay, since you’ll be under time pressure.

If you agree with the question overall, it can be helpful to organise your points in the following pattern:

- YES (agreement with the question)

- AND (another YES point)

- BUT (disagreement or complication)

If you disagree with the question overall, try:

- AND (another BUT point)

For example, you could structure the Of Mice and Men sample question, “To what extent is Curley’s wife portrayed as a victim in Of Mice and Men ?”, as follows:

- YES (descriptions of her appearance)

- AND (other people’s attitudes towards her)

- BUT (her position as the only woman on the ranch gives her power as she uses her femininity to her advantage)

If you wanted to write a longer essay, you could include additional paragraphs under the YES/AND categories, perhaps discussing the ways in which Curley’s wife reveals her vulnerability and insecurities, and shares her dreams with the other characters. Alternatively, you could also lengthen your essay by including another BUT paragraph about her cruel and manipulative streak.

Of course, this is not necessarily the only right way to answer this essay question – as long as you back up your points with evidence from the text, you can take any standpoint that makes sense.

Step 3: Back up your points with well-analysed quotations

You wouldn’t write a scientific report without including evidence to support your findings, so why should it be any different with an essay? Even though you aren’t strictly required to substantiate every single point you make with a quotation, there’s no harm in trying.

A close reading of your quotations can enrich your appreciation of the question and will be sure to impress examiners. When selecting the best quotations to use in your essay, keep an eye out for specific literary techniques. For example, you could highlight Curley’s wife’s use of a rhetorical question when she says, a”n’ what am I doin’? Standin’ here talking to a bunch of bindle stiffs.” This might look like:

The rhetorical question “an’ what am I doin’?” signifies that Curley’s wife is very insecure; she seems to be questioning her own life choices. Moreover, she does not expect anyone to respond to her question, highlighting her loneliness and isolation on the ranch.

Other literary techniques to look out for include:

- Tricolon – a group of three words or phrases placed close together for emphasis

- Tautology – using different words that mean the same thing: e.g. “frightening” and “terrifying”

- Parallelism – ABAB structure, often signifying movement from one concept to another

- Chiasmus – ABBA structure, drawing attention to a phrase

- Polysyndeton – many conjunctions in a sentence

- Asyndeton – lack of conjunctions, which can speed up the pace of a sentence

- Polyptoton – using the same word in different forms for emphasis: e.g. “done” and “doing”

- Alliteration – repetition of the same sound, including assonance (similar vowel sounds), plosive alliteration (“b”, “d” and “p” sounds) and sibilance (“s” sounds)

- Anaphora – repetition of words, often used to emphasise a particular point

Don’t worry if you can’t locate all of these literary devices in the work you’re analysing. You can also discuss more obvious techniques, like metaphor, simile and onomatopoeia. It’s not a problem if you can’t remember all the long names; it’s far more important to be able to confidently explain the effects of each technique and highlight its relevance to the question.

Step 4: Be creative and original throughout

Anyone can write an essay using the tips above, but the thing that really makes it “perfect” is your own unique take on the topic. If you’ve noticed something intriguing or unusual in your reading, point it out – if you find it interesting, chances are the examiner will too!

Creative writing and essay writing are more closely linked than you might imagine. Keep the idea that you’re writing a speech or argument in mind, and you’re guaranteed to grab your reader’s attention.

It’s important to set out your line of argument in your introduction, introducing your main points and the general direction your essay will take, but don’t forget to keep something back for the conclusion, too. Yes, you need to summarise your main points, but if you’re just repeating the things you said in your introduction, the body of the essay is rendered pointless.

Think of your conclusion as the climax of your speech, the bit everything else has been leading up to, rather than the boring plenary at the end of the interesting stuff.

To return to Of Mice and Men once more, here’s an example of the ideal difference between an introduction and a conclusion:

Introduction

In John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men , Curley’s wife is portrayed as an ambiguous character. She could be viewed either as a cruel, seductive temptress or a lonely woman who is a victim of her society’s attitudes. Though she does seem to wield a form of sexual power, it is clear that Curley’s wife is largely a victim. This interpretation is supported by Steinbeck’s description of her appearance, other people’s attitudes, her dreams, and her evident loneliness and insecurity.

Overall, it is clear that Curley’s wife is a victim and is portrayed as such throughout the novel in the descriptions of her appearance, her dreams, other people’s judgemental attitudes, and her loneliness and insecurities. However, a character who was a victim and nothing else would be one-dimensional and Curley’s wife is not. Although she suffers in many ways, she is shown to assert herself through the manipulation of her femininity – a small rebellion against the victimisation she experiences.

Both refer back consistently to the question and summarise the essay’s main points. However, the conclusion adds something new which has been established in the main body of the essay and complicates the simple summary which is found in the introduction.

Hannah is an undergraduate English student at Somerville College, University of Oxford, and has a particular interest in postcolonial literature and the Gothic. She thinks literature is a crucial way of developing empathy and learning about the wider world. When she isn’t writing about 17th-century court masques, she enjoys acting, travelling and creative writing.

Recommended articles

A Day in the Life of an Oxford Scholastica Student: The First Monday

Hello, I’m Abaigeal or Abby for short, and I attended Oxford Scholastica’s residential summer school as a Discover Business student. During the Business course, I studied various topics across the large spectrum that is the world of business, including supply and...

Mastering Writing Competitions: Insider Tips from a Two-Time Winner

I’m Costas, a third-year History and Spanish student at the University of Oxford. During my time in secondary school and sixth form, I participated in various writing competitions, and I was able to win two of them (the national ISMLA Original Writing Competition and...

Beyond the Bar: 15 Must-Read Books for Future Lawyers

Reading within and around your subject, widely and in depth, is one of the most important things you can do to prepare yourself for a future in Law. So, we’ve put together a list of essential books to include on your reading list as a prospective or current Law...

Would you like to explore a topic?

- LEARNING OUTSIDE OF SCHOOL

Or read some of our popular articles?

Free downloadable english gcse past papers with mark scheme.

- 19 May 2022

How Will GCSE Grade Boundaries Affect My Child’s Results?

- Akshat Biyani

- 13 December 2021

The Best Free Homeschooling Resources UK Parents Need to Start Using Today

- Joseph McCrossan

- 18 February 2022

How to Write the Perfect Essay: A Step-By-Step Guide for Students

- June 2, 2022

- What is an essay?

What makes a good essay?

Typical essay structure, 7 steps to writing a good essay, a step-by-step guide to writing a good essay.

Whether you are gearing up for your GCSE coursework submissions or looking to brush up on your A-level writing skills, we have the perfect essay-writing guide for you. 💯

Staring at a blank page before writing an essay can feel a little daunting . Where do you start? What should your introduction say? And how should you structure your arguments? They are all fair questions and we have the answers! Take the stress out of essay writing with this step-by-step guide – you’ll be typing away in no time. 👩💻

What is an essay?

Generally speaking, an essay designates a literary work in which the author defends a point of view or a personal conviction, using logical arguments and literary devices in order to inform and convince the reader.

So – although essays can be broadly split into four categories: argumentative, expository, narrative, and descriptive – an essay can simply be described as a focused piece of writing designed to inform or persuade. 🤔

The purpose of an essay is to present a coherent argument in response to a stimulus or question and to persuade the reader that your position is credible, believable and reasonable. 👌

So, a ‘good’ essay relies on a confident writing style – it’s clear, well-substantiated, focussed, explanatory and descriptive . The structure follows a logical progression and above all, the body of the essay clearly correlates to the tile – answering the question where one has been posed.

But, how do you go about making sure that you tick all these boxes and keep within a specified word count? Read on for the answer as well as an example essay structure to follow and a handy step-by-step guide to writing the perfect essay – hooray. 🙌

Sometimes, it is helpful to think about your essay like it is a well-balanced argument or a speech – it needs to have a logical structure, with all your points coming together to answer the question in a coherent manner. ⚖️

Of course, essays can vary significantly in length but besides that, they all follow a fairly strict pattern or structure made up of three sections. Lean into this predictability because it will keep you on track and help you make your point clearly. Let’s take a look at the typical essay structure:

#1 Introduction

Start your introduction with the central claim of your essay. Let the reader know exactly what you intend to say with this essay. Communicate what you’re going to argue, and in what order. The final part of your introduction should also say what conclusions you’re going to draw – it sounds counter-intuitive but it’s not – more on that below. 1️⃣

Make your point, evidence it and explain it. This part of the essay – generally made up of three or more paragraphs depending on the length of your essay – is where you present your argument. The first sentence of each paragraph – much like an introduction to an essay – should summarise what your paragraph intends to explain in more detail. 2️⃣

#3 Conclusion

This is where you affirm your argument – remind the reader what you just proved in your essay and how you did it. This section will sound quite similar to your introduction but – having written the essay – you’ll be summarising rather than setting out your stall. 3️⃣

No essay is the same but your approach to writing them can be. As well as some best practice tips, we have gathered our favourite advice from expert essay-writers and compiled the following 7-step guide to writing a good essay every time. 👍

#1 Make sure you understand the question

#2 complete background reading.

#3 Make a detailed plan

#4 Write your opening sentences

#5 flesh out your essay in a rough draft, #6 evidence your opinion, #7 final proofread and edit.

Now that you have familiarised yourself with the 7 steps standing between you and the perfect essay, let’s take a closer look at each of those stages so that you can get on with crafting your written arguments with confidence .

This is the most crucial stage in essay writing – r ead the essay prompt carefully and understand the question. Highlight the keywords – like ‘compare,’ ‘contrast’ ‘discuss,’ ‘explain’ or ‘evaluate’ – and let it sink in before your mind starts racing . There is nothing worse than writing 500 words before realising you have entirely missed the brief . 🧐

Unless you are writing under exam conditions , you will most likely have been working towards this essay for some time, by doing thorough background reading. Re-read relevant chapters and sections, highlight pertinent material and maybe even stray outside the designated reading list, this shows genuine interest and extended knowledge. 📚

#3 Make a detailed plan

Following the handy structure we shared with you above, now is the time to create the ‘skeleton structure’ or essay plan. Working from your essay title, plot out what you want your paragraphs to cover and how that information is going to flow. You don’t need to start writing any full sentences yet but it might be useful to think about the various quotes you plan to use to substantiate each section. 📝

Having mapped out the overall trajectory of your essay, you can start to drill down into the detail. First, write the opening sentence for each of the paragraphs in the body section of your essay. Remember – each paragraph is like a mini-essay – the opening sentence should summarise what the paragraph will then go on to explain in more detail. 🖊️

Next, it's time to write the bulk of your words and flesh out your arguments. Follow the ‘point, evidence, explain’ method. The opening sentences – already written – should introduce your ‘points’, so now you need to ‘evidence’ them with corroborating research and ‘explain’ how the evidence you’ve presented proves the point you’re trying to make. ✍️

With a rough draft in front of you, you can take a moment to read what you have written so far. Are there any sections that require further substantiation? Have you managed to include the most relevant material you originally highlighted in your background reading? Now is the time to make sure you have evidenced all your opinions and claims with the strongest quotes, citations and material. 📗

This is your final chance to re-read your essay and go over it with a fine-toothed comb before pressing ‘submit’. We highly recommend leaving a day or two between finishing your essay and the final proofread if possible – you’ll be amazed at the difference this makes, allowing you to return with a fresh pair of eyes and a more discerning judgment. 🤓

If you are looking for advice and support with your own essay-writing adventures, why not t ry a free trial lesson with GoStudent? Our tutors are experts at boosting academic success and having fun along the way. Get in touch and see how it can work for you today. 🎒

Popular posts

- By Guy Doza

- By Akshat Biyani

- By Joseph McCrossan

- In LEARNING TRENDS

4 Surprising Disadvantages of Homeschooling

- By Andrea Butler

What are the Hardest GCSEs? Should You Avoid or Embrace Them?

- By Clarissa Joshua

More great reads:

Benefits of Reading: Positive Impacts for All Ages Everyday

- May 26, 2023

15 of the Best Children's Books That Every Young Person Should Read

- By Sharlene Matharu

- March 2, 2023

Ultimate School Library Tips and Hacks

- By Natalie Lever

- March 1, 2023

Book a free trial session

Sign up for your free tutoring lesson..

Ultimate Guide to Writing Your College Essay

Tips for writing an effective college essay.

College admissions essays are an important part of your college application and gives you the chance to show colleges and universities your character and experiences. This guide will give you tips to write an effective college essay.

Want free help with your college essay?

UPchieve connects you with knowledgeable and friendly college advisors—online, 24/7, and completely free. Get 1:1 help brainstorming topics, outlining your essay, revising a draft, or editing grammar.

Writing a strong college admissions essay

Learn about the elements of a solid admissions essay.

Avoiding common admissions essay mistakes

Learn some of the most common mistakes made on college essays

Brainstorming tips for your college essay

Stuck on what to write your college essay about? Here are some exercises to help you get started.

How formal should the tone of your college essay be?

Learn how formal your college essay should be and get tips on how to bring out your natural voice.

Taking your college essay to the next level

Hear an admissions expert discuss the appropriate level of depth necessary in your college essay.

Student Stories

Student Story: Admissions essay about a formative experience

Get the perspective of a current college student on how he approached the admissions essay.

Student Story: Admissions essay about personal identity

Get the perspective of a current college student on how she approached the admissions essay.

Student Story: Admissions essay about community impact

Student story: admissions essay about a past mistake, how to write a college application essay, tips for writing an effective application essay, sample college essay 1 with feedback, sample college essay 2 with feedback.

This content is licensed by Khan Academy and is available for free at www.khanacademy.org.

100+ Useful Words and Phrases to Write a Great Essay

By: Author Sophia

Posted on Last updated: October 25, 2023

Sharing is caring!

How to Write a Great Essay in English! This lesson provides 100+ useful words, transition words and expressions used in writing an essay. Let’s take a look!

The secret to a successful essay doesn’t just lie in the clever things you talk about and the way you structure your points.

Useful Words and Phrases to Write a Great Essay

Overview of an essay.

Useful Phrases for Proficiency Essays

Developing the argument

- The first aspect to point out is that…

- Let us start by considering the facts.

- The novel portrays, deals with, revolves around…

- Central to the novel is…

- The character of xxx embodies/ epitomizes…

The other side of the argument

- It would also be interesting to see…

- One should, nevertheless, consider the problem from another angle.

- Equally relevant to the issue are the questions of…

- The arguments we have presented… suggest that…/ prove that…/ would indicate that…

- From these arguments one must…/ could…/ might… conclude that…

- All of this points to the conclusion that…

- To conclude…

Ordering elements

- Firstly,…/ Secondly,…/ Finally,… (note the comma after all these introductory words.)

- As a final point…

- On the one hand, …. on the other hand…

- If on the one hand it can be said that… the same is not true for…

- The first argument suggests that… whilst the second suggests that…

- There are at least xxx points to highlight.

Adding elements

- Furthermore, one should not forget that…

- In addition to…

- Moreover…

- It is important to add that…

Accepting other points of view

- Nevertheless, one should accept that…

- However, we also agree that…

Personal opinion

- We/I personally believe that…

- Our/My own point of view is that…

- It is my contention that…

- I am convinced that…

- My own opinion is…

Others’ opinions

- According to some critics… Critics:

- believe that

- suggest that

- are convinced that

- point out that

- emphasize that

- contend that

- go as far as to say that

- argue for this

Introducing examples

- For example…

- For instance…

- To illustrate this point…

Introducing facts

- It is… true that…/ clear that…/ noticeable that…

- One should note here that…

Saying what you think is true

- This leads us to believe that…

- It is very possible that…

- In view of these facts, it is quite likely that…

- Doubtless,…

- One cannot deny that…

- It is (very) clear from these observations that…

- All the same, it is possible that…

- It is difficult to believe that…

Accepting other points to a certain degree

- One can agree up to a certain point with…

- Certainly,… However,…

- It cannot be denied that…

Emphasizing particular points

- The last example highlights the fact that…

- Not only… but also…

- We would even go so far as to say that…

Moderating, agreeing, disagreeing

- By and large…

- Perhaps we should also point out the fact that…

- It would be unfair not to mention the fact that…

- One must admit that…

- We cannot ignore the fact that…

- One cannot possibly accept the fact that…

Consequences

- From these facts, one may conclude that…

- That is why, in our opinion, …

- Which seems to confirm the idea that…

- Thus,…/ Therefore,…

- Some critics suggest…, whereas others…

- Compared to…

- On the one hand, there is the firm belief that… On the other hand, many people are convinced that…

How to Write a Great Essay | Image 1

How to Write a Great Essay | Image 2

Phrases For Balanced Arguments

Introduction

- It is often said that…

- It is undeniable that…

- It is a well-known fact that…

- One of the most striking features of this text is…

- The first thing that needs to be said is…

- First of all, let us try to analyze…

- One argument in support of…

- We must distinguish carefully between…

- The second reason for…

- An important aspect of the text is…

- It is worth stating at this point that…

- On the other hand, we can observe that…

- The other side of the coin is, however, that…

- Another way of looking at this question is to…

- What conclusions can be drawn from all this?

- The most satisfactory conclusion that we can come to is…

- To sum up… we are convinced that…/ …we believe that…/ …we have to accept that…

How to Write a Great Essay | Image 3

- Recent Posts

- Plural of Process in the English Grammar - October 3, 2023

- Best Kahoot Names: Get Creative with These Fun Ideas! - October 2, 2023

- List of Homophones for English Learners - September 30, 2023

Related posts:

- How to Write a Formal Letter | Useful Phrases with ESL Image

- 50+ Questions to Start a Conversation with Anyone in English

- Useful English Greetings and Expressions for English Learners

- Asking for Help, Asking for Opinions and Asking for Approval

Nur Syuhadah Zainuddin

Friday 19th of August 2022

thank u so much its really usefull

12thSeahorse

Wednesday 3rd of August 2022

He or she who masters the English language rules the world!

Friday 25th of March 2022

Thank you so so much, this helped me in my essays with A+

Theophilus Muzvidziwa

Friday 11th of March 2022

Monday 21st of February 2022

What Makes a Good Essay?

By stephanie whetstone.

The deadline for this year’s Princeton Writes Prize Staff Essay Contest has been set (March 1, 2020)! We hope you are already hard at work polishing your prose, but in case you are struggling to get started, let’s consider what makes a “good” essay.

Dictionary.com defines the essay as “a short literary composition on a particular theme or subject, usually in prose and generally analytic, speculative, or interpretative.” This leaves a lot of room for creativity. For a personal essay, focus on the personal part. Why are you writing about this subject? Why now? How does your experience connect with your audience’s? A personal essay is not self-indulgent; rather, it is a means of connecting with others through the common experience of being human.

The winners of the Princeton Writes Prize have written about New South, travels in Japan, a timeworn stone step, and a dining room table. None of these subjects is inherently gripping, but they became so when connected to the writer’s thoughtful, heartfelt experience.

Write as specifically as you can about what is important to you, what excites you, what connects you to the world, or what you can’t seem to get off your mind. So how do you start? Think about your purpose: is it to entertain, to explain, to argue, to compare, or to reveal? It can also be a combination of these things.

At Princeton, we are lucky to have one of the great essay writers of our time, John McPhee, on faculty. In his wonderful essay, “Searching for Marvin Gardens,” McPhee has a few stories going at once: the “real time” experience of playing monopoly with a friend, his walk through the streets of Atlantic City, the history of the creation of the game of Monopoly, and a commentary about the economic and social realities of the time in which the essay was written. It begins:

“Go. I roll the dice—a six and a two. Through the air I move my token, the flatiron, to Vermont Avenue, where dog packs range.

“The dogs are moving (some are limping) through ruins, rubble, fire damage, open garbage. Doorways are gone. Lath is visible in the crumbling walls of the buildings. The street sparkles with shattered glass. I have never seen, anywhere, so many broken windows. A sign—”Slow, Children at Play”—has been bent backward by an automobile. At the farmhouse, the dogs turn up Pacific and disappear.”

The primary action puts the reader immediately into the world the writer has created and follows “characters” through a plot. The connecting paragraphs provide context and place the experience in the broader world. You may want to tell your story straight through or, like McPhee, stray from a linear structure—not just beginning, middle, end—moving back and forth in time.

Begin your story at the last possible moment you can without losing important information. If you are writing about the birth of a child, for example, you might want to start in the hospital in the midst of labor, rather than months before.

To shift in time, make sure you have an object or experience to “trigger” the shift, such as McPhee’s dogs. You need not be as accomplished as he to write your own essay, but reading his work and the work of other writers can provide guidance and inspiration.

Remember that an essay is a story, so even though it is nonfiction, it will benefit from the elements of a story: characters, plot, setting, dialogue, point of view, and tone. Is your story funny, sad, contemplative, nostalgic, magical, or a combination of these?

Your job as a writer is to help the reader imagine what you see in your mind’s eye. That requires sensory detail. Be sure to write about sounds, sights, smells, textures, and tastes. Remember, too, that your work will be read by a wide audience, so you need to determine how much of yourself and your intimate experience you are comfortable sharing.

Another great Princeton writer, Joyce Carol Oates, writes with exquisite sensory detail in her essay, “They All Just Went Away.”

“To push open a door into such silence: the absolute emptiness of a house whose occupants have departed. Often, the crack of broken glass underfoot. A startled buzzing of flies, hornets. The slithering, ticklish sensation of a garter snake crawling across floorboards.

“Left behind, as if in haste, were remnants of a lost household. A broken toy on the floor, a baby’s bottle. A rain-soaked sofa, looking as if it had been gutted with a hunter’s skilled knife. Strips of wallpaper like shredded skin. Smashed crockery, piles of tin cans; soda, beer, whiskey bottles. An icebox, its door yawning open. Once, on a counter, a dirt-stiffened rag that, unfolded like precious cloth, revealed itself to be a woman’s cheaply glamorous “see-through” blouse, threaded with glitter-strips of gold.”

No matter what you choose to write about, forgive your first draft if it’s terrible. You will improve it in the editing. And finally, read each draft aloud: tell the story first to yourself.

Happy writing!

Contact Info

B03 New South Building, Princeton University

Phone: 609.258.9980

Email: [email protected]

Recent Posts

- Word of the Week: bedizen (bih-DYE-zun)

- Word of the Week: Minion (MIN-yun)

- A Poem for You: Parkside & Ocean by b ferguson

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, getting college essay help: important do's and don’ts.

College Essays

If you grow up to be a professional writer, everything you write will first go through an editor before being published. This is because the process of writing is really a process of re-writing —of rethinking and reexamining your work, usually with the help of someone else. So what does this mean for your student writing? And in particular, what does it mean for very important, but nonprofessional writing like your college essay? Should you ask your parents to look at your essay? Pay for an essay service?

If you are wondering what kind of help you can, and should, get with your personal statement, you've come to the right place! In this article, I'll talk about what kind of writing help is useful, ethical, and even expected for your college admission essay . I'll also point out who would make a good editor, what the differences between editing and proofreading are, what to expect from a good editor, and how to spot and stay away from a bad one.

Table of Contents

What Kind of Help for Your Essay Can You Get?

What's Good Editing?

What should an editor do for you, what kind of editing should you avoid, proofreading, what's good proofreading, what kind of proofreading should you avoid.

What Do Colleges Think Of You Getting Help With Your Essay?

Who Can/Should Help You?

Advice for editors.

Should You Pay Money For Essay Editing?

The Bottom Line

What's next, what kind of help with your essay can you get.

Rather than talking in general terms about "help," let's first clarify the two different ways that someone else can improve your writing . There is editing, which is the more intensive kind of assistance that you can use throughout the whole process. And then there's proofreading, which is the last step of really polishing your final product.

Let me go into some more detail about editing and proofreading, and then explain how good editors and proofreaders can help you."

Editing is helping the author (in this case, you) go from a rough draft to a finished work . Editing is the process of asking questions about what you're saying, how you're saying it, and how you're organizing your ideas. But not all editing is good editing . In fact, it's very easy for an editor to cross the line from supportive to overbearing and over-involved.

Ability to clarify assignments. A good editor is usually a good writer, and certainly has to be a good reader. For example, in this case, a good editor should make sure you understand the actual essay prompt you're supposed to be answering.

Open-endedness. Good editing is all about asking questions about your ideas and work, but without providing answers. It's about letting you stick to your story and message, and doesn't alter your point of view.

Think of an editor as a great travel guide. It can show you the many different places your trip could take you. It should explain any parts of the trip that could derail your trip or confuse the traveler. But it never dictates your path, never forces you to go somewhere you don't want to go, and never ignores your interests so that the trip no longer seems like it's your own. So what should good editors do?

Help Brainstorm Topics

Sometimes it's easier to bounce thoughts off of someone else. This doesn't mean that your editor gets to come up with ideas, but they can certainly respond to the various topic options you've come up with. This way, you're less likely to write about the most boring of your ideas, or to write about something that isn't actually important to you.

If you're wondering how to come up with options for your editor to consider, check out our guide to brainstorming topics for your college essay .

Help Revise Your Drafts

Here, your editor can't upset the delicate balance of not intervening too much or too little. It's tricky, but a great way to think about it is to remember: editing is about asking questions, not giving answers .