- Sustainability

- Responsible Business

- Small Medium Business

- Pitch A Story

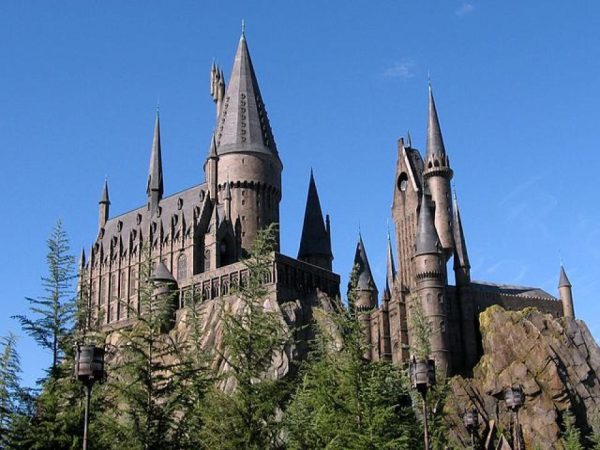

Image Credit- Wikipedia , Pixabay (Representational)

No Tests, No Homework! Here's How Finland Has Emerged As A Global Example Of Quality, Inclusive Education

Others/world, 15 may 2022 3:40 am gmt, editor : shiva chaudhary | .

Shiva Chaudhary

Digital Editor

A post-graduate in Journalism and Mass Communication with relevant skills, specialising in content editing & writing. I believe in the precise dissemination of information based on facts to the public.

Creatives : Shiva Chaudhary

Student-oriented approach to education in finland has been recognised as the most well-developed educational system in the world and ranks third in education worldwide..

"A quality education grants us the ability to fight the war on ignorance and poverty," - Charles Rangel

The uniqueness of the Finnish education model is encapsulated in its values of neither giving homework to students every day nor conducting regular tests and exams. Instead, it is listening to what the kids want and treating them as independent thinkers of society.

In Finland, the aim is to let students be happy and respect themselves and others.

Goodbye Standardised Exams

There is absolutely no program of nationwide standard testing, such as in India or the U.S, where those exams are the decisive points of one's admission to higher education like Board Examinations or Common Entrance Tests.

In an event organised by Shiksha Sanskriti Utthan Nyas, RSS Chief Mohan Bhagwat remarked, "It is because they teach their children to face life struggles and not score in an examination," reported The Print .

Students in Finland are graded based on individual performance and evaluation criteria decided by their teachers themselves. Overall progress is tracked by their government's Ministry of Education, where they sample groups of students across schools in Finland.

Value-Based Education

They are primarily focused on making school a safe and equal space as children learn from the environment.

All Finland schools have offered since the 1980s free school meals, access to healthcare, a focus on mental health through psychological counselling for everyone and guidance sessions for each student to understand their wants and needs.

Education in Finland is not about marks or ranks but about creating an atmosphere of social equality, harmony and happiness for the students to ease learning experiences.

Most of the students spend half an hour at home after school to work on their studies. They mostly get everything done in the duration of the school timings as they only have a few classes every day. They are given several 15 -20 minutes breaks to eat, do recreational activities, relax, and do other work. There is no regiment in school or a rigid timetable, thus, causing less stress as given in the World Economic Forum .

Everyone Is Equal - Cooperate, Not Compete

The schools do not put pressure on ranking students, schools, or competitions, and they believe that a real winner doesn't compete; they help others come up to their level to make everyone on par.

Even though individualism is promoted during evaluation based on every student's needs, collectivity and fostering cooperation among students and teachers are deemed crucial.

While most schools worldwide believe in Charles Darwin's survival of the fittest, Finland follows the opposite but still comes out at the top.

Student-Oriented Model

The school teachers believe in a simple thumb rule; students are children who need to be happy when they attend school to learn and give their best. Focus is put upon teaching students to be critical thinkers of what they know, engage in society, and decide for themselves what they want.

In various schools, playgrounds are created by children's input as the architect talks to the children about what they want or what they feel like playing before setting up the playground.

Compared To The Indian Education Model

Firstly, Finnish children enrol in schools at the age of six rather than in India, where the school age is usually three or four years old. Their childhood is free from constricting education or forced work, and they are given free rein over how they socialise and participate in society.

Secondly, all schools in Finland are free of tuition fees as there are no private schools. Thus, education is not treated as a business. Even tuition outside schools is not allowed or needed, leaving no scope for commodifying education, unlike in India, where multiple coaching centres and private schools require exorbitant fees.

Thirdly, the school hours in Finland do not start early morning at 6 am, or 7 am as done in India. Finland schools begin from 9.30 am as research in World Economic Forum has indicated that schools starting at an early age is detrimental to their health and maturation. The school ends by mostly 2 pm.

Lastly, there is no homework or surprise test given to students in Finland. Teachers believe that the time wasted on assignments can be used to perform hobbies, art, sports, or cooking. This can teach life lessons and have a therapeutic stress-relieving effect on children. Indian schools tend to give a lot of homework to prove their commitment to studying and constantly revise what they learn in school.

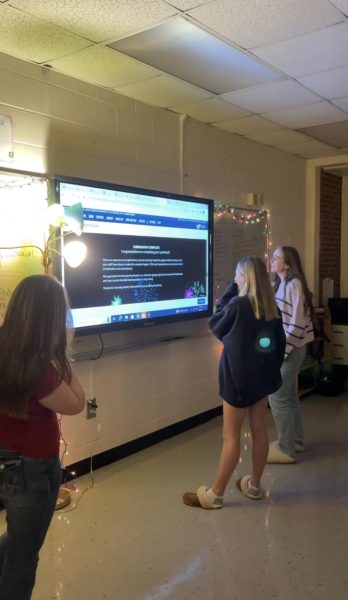

Delhi Govt's Focus On Education

The Delhi model of education transformed under the Aam Aadmi Party's (AAP) tenure in the capital. In line with the Finnish model, Delhi government schools have adopted 'Happiness Classes' to ensure students' mental wellness through courses on mindfulness, problem-solving, social and emotional relationships, etc., from 1st to 8th classes.

Delhi government also introduced 'Entrepreneurial Mindset Classes' in 2019 to instil business and critical thinking skills among students of 9th to 12th classes. The practical approach in this class is indicated in the 'Business Blasters', a competition started by the Delhi government to encourage students to come up with start-up ideas and students were provided with ₹1000. Approximately 51,000 students participated in the first edition of the competition, according to Citizen Matters .

Through these endeavours, India is steadily investing in creating human resources that can get employment and generate employment for themselves.

India is at its demographic dividend stage; more than half of its population is within the working-age group of 14 to 60 years. Education is an essential factor in utilising this considerable advantage to grow economically and socially. Finland's education model is how India can strive closer to its goal and progress as a nation.

Also Read: Connaissance! Delhi Board of School Education Pens MoU To Add French In Government Schools

We are an independent and public-spirited digital media platform for Indian millennials. We report news and issues that matter as well as give you the opportunity to take action.

clock This article was published more than 4 years ago

What Finland is really doing to improve its acclaimed schools

Finland has been paid outsized attention in the education world since its students scored the highest among dozens of countries around the globe on an international test some 20 years ago.

And while it is no longer No. 1 — as the education sector was hurt in the 2008 recession, and budget cuts led to larger class sizes and fewer staff in schools — it is still regarded as one of the more successful systems in the world.

In an effort to improve, the Finnish government began taking some steps in recent years, and some of that reform has made for worldwide headlines. But as it turns out, some of that coverage just isn’t true.

A few years ago, for example, a change in curriculum sparked stories that Finland was giving up teaching traditional subjects. Nope .

You can find stories on the Internet saying Finnish kids don’t get any homework. Nope.

Even amid its difficulties, American author William Doyle, who lived there and sent his then-7-year-old son to a Finnish school, wrote in 2016 that they do a lot of things right:

What is Finland’s secret? A whole-child-centered, research-and-evidence based school system, run by highly professionalized teachers. These are global education best practices, not cultural quirks applicable only to Finland.

‘I have seen the school of tomorrow. It is here today, in Finland.’

Here is a piece looking at changes underway in Finnish schools by two people who know what is really going on. They are Pasi Sahlberg and Peter Johnson. Johnson is director of education of the Finnish city of Kokkola. Sahlberg is professor of education policy at the University of New South Wales in Sydney. He is one of the world’s leading experts on school reform and is the author of the best-selling “ Finnish Lessons: What Can the World Learn About Educational Change in Finland ?”

No, Finland isn’t ditching traditional school subjects. Here’s what’s really happening.

By Pasi Sahlberg and Peter Johnson

Finland has been in the spotlight of the education world since it appeared, against all odds, on the top of the rankings of an international test known as PISA , the Program for International Student Assessment, in the early 2000s. Tens of thousands visitors have traveled to the country to see how to improve their own schools. Hundreds of articles have been written to explain why Finnish education is so marvelous — or sometimes that it isn’t. Millions of tweets have been shared and read, often leading to debates about the real nature of Finland’s schools and about teaching and learning there.

We have learned a lot about why some education systems — such as Alberta, Ontario, Japan and Finland — perform better year after year than others in terms of quality and equity of student outcomes. We also understand now better why some other education systems — for example, England, Australia, the United States and Sweden — have not been able to improve their school systems regardless of politicians’ promises, large-scale reforms and truckloads of money spent on haphazard efforts to change schools during the past two decades.

Among these important lessons are:

- Education systems and schools shouldn’t be managed like business corporations where tough competition, measurement-based accountability and performance-determined pay are common principles. Instead, successful education systems rely on collaboration, trust, and collegial responsibility in and between schools.

- The teaching profession shouldn’t be perceived as a technical, temporary craft that anyone with a little guidance can do. Successful education systems rely on continuous professionalization of teaching and school leadership that requires advanced academic education, solid scientific and practical knowledge, and continuous on-the-job training.

- The quality of education shouldn’t be judged by the level of literacy and numeracy test scores alone. Successful education systems are designed to emphasize whole-child development, equity of education outcomes, well being, and arts, music, drama and physical education as important elements of curriculum.

Besides these useful lessons about how and why education systems work as they do, there are misunderstandings, incorrect interpretations, myths and even deliberate lies about how to best improve education systems. Because Finland has been such a popular target of searching for the key to the betterment of education, there are also many stories about Finnish schools that are not true.

Part of the reason reporting and research often fail to paint bigger and more accurate picture of the actual situation is that most of the documents and resources that describe and define the Finnish education system are only available in Finnish and Swedish. Most foreign education observers and commentators are therefore unable to follow the conversations and debates taking place in the country.

For example, only very few of those who actively comment on education in Finland have ever read Finnish education law , the national core curriculum or any of thousands of curricula designed by municipalities and schools that explain and describe what schools ought to do and why.

The other reason many efforts to report about Finnish education remain incomplete — and sometimes incorrect — is that education is seen as an isolated island disconnected from other sectors and public policies. It is wrong to believe that what children learn or don’t learn in school could be explained by looking at only schools and what they do alone.

Most efforts to explain why Finland’s schools are better than others or why they do worse today than before fail to see these interdependencies in Finnish society that are essential in understanding education as an ecosystem.

Here are some of those common myths about Finnish schools.

First, in recent years there have been claims that the Finnish secret to educational greatness is that children don’t have homework.

Another commonly held belief is that Finnish authorities have decided to scrap subjects from school curriculum and replace them by interdisciplinary projects or themes.

And a more recent notion is that all schools in Finland are required to follow a national curriculum and implement the same teaching method called “phenomenon-based learning” (that is elsewhere known as “project-based learning”).

All of these are false.

In 2014, Finnish state authorities revised the national core curriculum (NCC) for basic education. The core curriculum provides a common direction and basis for renewing school education and instruction. Only a very few international commentators of Finnish school reform have read this central document. Unfortunately, not many parents in Finland are familiar with it, either. Still, many people seem to have strong opinions about the direction Finnish schools are moving — the wrong way, they say, without really understanding the roles and responsibilities of schools and teachers in their communities.

Before making any judgments about what is great or wrong in Finland, it is important to understand the fundamentals of Finnish school system. Here are some basics.

First, education providers, most districts in 311 municipalities, draw up local curricula and annual work plans on the basis of the NCC. Schools though actually take the lead in curriculum planning under the supervision of municipal authorities.

Second, the NCC is a fairly loose regulatory document in terms of what schools should teach, how they arrange their work and the desired outcomes. Schools have, therefore, a lot of flexibility and autonomy in curriculum design, and there may be significant variation in school curricula from one place to another.

Finally, because of this decentralized nature of authority in Finnish education system, schools in Finland can have different profiles and practical arrangements making the curriculum model unique in the world. It is incorrect to make any general conclusions based on what one or two schools do.

Current school reform in Finland aims at those same overall goals that the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development — which gives the PISA exams every three years to 15-year-olds in multiple countries — as well as governments and many students say are essential for them: to develop safe and collaborative school culture and to promote holistic approaches in teaching and learning. The NCC states that the specific aim at the school level is that children would:

- understand the relationship and interdependencies between different learning contents;

- be able to combine the knowledge and skills learned in different disciplines to form meaningful wholes; and

- be able to apply knowledge and use it in collaborative learning settings.

All schools in Finland are required to revise their curricula according to this new framework. Some schools have taken only small steps from where they were before, while some others went on with much bolder plans. One of those is the Pontus School in Lappeenranta, a city in the eastern part of Finland.

The Pontus School is a new primary school and kindergarten for some 550 children from ages 1 to 12. It was built three years ago to support the pedagogy and spirit of the 2014 NCC. The Pontus School was in international news recently when the Finnish Broadcasting Company reported that parents have filed complaints over the “failure” of the new school.

But according to Lappeenranta education authorities, there have been only two complaints by parents, both being handled by Regional Authorities. That’s all. It is not enough to call that a failure.

What we can learn from Finland, again, is that it is important to make sure parents, children and media better understand the nature of school reforms underway.

“Some parents are not familiar with what schools are doing,” said Anu Liljestrom, superintendent of the education department in Lappeenranta. “We still have a lot of work to do to explain what, how and why teaching methods are different nowadays,” she said to a local newspaper. The Pontus School is a new school, and it decided to use the opportunity provided by new design to change pedagogy and learning.

Ultimately, it is wrong to think that reading, writing and arithmetic will disappear in Finnish classrooms.

For most of the school year, teaching in Finnish schools will continue to be based on subject-based curricula, including at the Pontus School.

What is new is that now all schools are required to design at least one week-long project for all students that is interdisciplinary and based on students’ interests. Some schools do that better more often than others, and some succeed sooner than others.

Yes, there are challenges in implementing the new ideas. We have seen many schools succeed at creating new opportunities for students to learn knowledge and skills they need in their lives.

It is too early to tell whether Finland’s current direction in education meets all expectations. What we know is that schools in Finland should take even bolder steps to meet the needs of the future as described in national goals and international strategies. Collaboration among schools, trust in teachers and visionary leadership are those building blocks that will make all that possible.

- Education System

- Fins and Fun

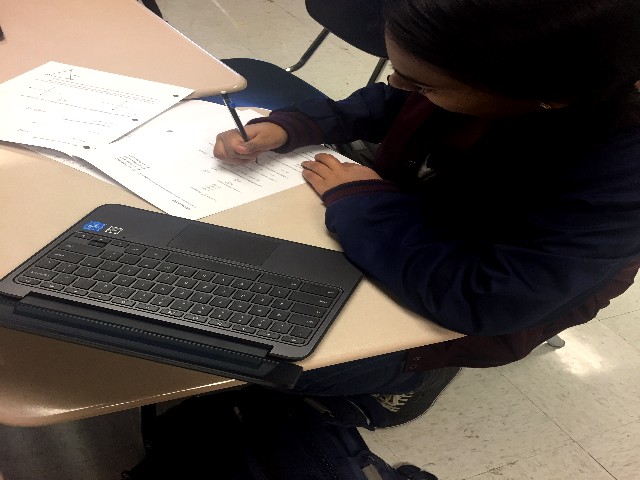

Homework in Finland School

How many parents are bracing themselves for nightly battles to get their kids to finish their homework every year with the beginning of a school year? Thousands and thousands of them. Though not in Finland. The truth is that there is nearly no homework in the country with one of the top education systems in the world. Finnish people believe that besides homework, there are many more things that can improve child’s performance in school, such as having dinner with their families, exercising or getting a good night’s sleep.

Do We Need Homework?

There are different homework policies around the world. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) keeps track of such policies and compares the amount of homework of students from different countries. For example, an average high school student in the US has to spend about 6 hours a day doing homework, while in Finland, the amount of time spent on after school learning is about 3 hours a day. Nevertheless, these are exactly Finnish students who lead the world in global scores for math and science. It means that despite the belief that homework increases student performance, OECD graph shows the opposite. Though there are some exceptions such as education system in Japan, South Korea, and some other Asian countries. In fact, according to OECD, the more time students spend on homework, the worse they perform in school.

Finnish education approach shows the world that when it comes to homework, less is more. It is worth to mention that the world has caught onto this idea and, according to the latest OECD report, the average number of hours spent by students doing their homework decreased in nearly all countries around the world.

So what Finland knows about homework that the rest of the world does not? There is no simple answer, as the success of education system in Finland is provided by many factors, starting from poverty rates in the country to parental leave policies to the availability of preschools. Nevertheless, one of the greatest secrets of the success of education system in Finland is the way Finns teach their children.

How to Teach Like The Finns?

There are three main points that have to be mentioned when it comes to the success of education system in Finland.

First of all, Finns teach their children in a “playful” manner and allow them to enjoy their childhood. For example, did you know that in average, students in Finland only have three to four classes a day? Furthermore, there are several breaks and recesses (15-20 minutes) during a school day when children can play outside whatever the weather. According to statistics, children need physical activity in order to learn better. Also, less time in the classroom allows Finnish teachers to think, plan and create more effective lessons.

Secondly, Finns pay high respect to teachers. That is why one of the most sought after positions in Finland is the position of a primary school teacher. Only 10% of applicants to the teaching programs are accepted. In addition to a high competition, each primary school teacher in Finland must earn a Master’s degree that provides Finnish teachers with the same status as doctors or lawyers.

High standards applied to applicants for the university teaching programs assure parents of a high quality of teaching and allow teachers to innovate without bureaucracy or excessive regulation.

Thirdly, there is a lot of individual attention for each student. Classes in Finland are smaller than in the most of other countries and for the first six years of study, teachers get to know their students, their individual needs, and learning styles. If there are some weaker students, they are provided by extra assistance. Overall, Finnish education system promotes warmth, collaboration, encouragement, and assessment which means that teachers in this country are ready to do their best to help students but not to gain more control over them.

The combination of these three fundamentals is the key to success of any education system in the world and Finns are exactly those people who proved by way of example that less is more, especially when it comes to the amount of homework.

System of education in Finland

School System in Finland

Finland Education Reform

Fins and Fun: Distinctive Features of Education in Finland

10 Facts About Education in Finland

- Privacy policy

Don’t Let Faulty Plumbing Ruin your Child’s Lesson

Flagship of Distance Education

LAST STRETCH!

You can still support your source of education news this teacher appreciation week.

The Hechinger Report

Covering Innovation & Inequality in Education

OPINION: How Finland broke every rule — and created a top school system

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

The Hechinger Report is a national nonprofit newsroom that reports on one topic: education. Sign up for our weekly newsletters to get stories like this delivered directly to your inbox. Consider supporting our stories and becoming a member today.

Spend five minutes in Jussi Hietava’s fourth-grade math class in remote, rural Finland, and you may learn all you need to know about education reform – if you want results, try doing the opposite of what American “education reformers” think we should do in classrooms.

Instead of control, competition, stress, standardized testing, screen-based schools and loosened teacher qualifications, try warmth, collaboration, and highly professionalized, teacher-led encouragement and assessment.

At the University of Eastern Finland’s Normaalikoulu teacher training school in Joensuu, Finland, you can see Hietava’s students enjoying the cutting-edge concept of “personalized learning.”

Related: Everyone aspires to be Finland, but this country beats them in two out of three subjects

But this is not a tale of classroom computers. While the school has the latest technology, there isn’t a tablet or smartphone in sight, just a smart board and a teacher’s desktop.

Screens can only deliver simulations of personalized learning, this is the real thing, pushed to the absolute limit.

This is the story of the quiet, daily, flesh-and-blood miracles that are achieved by Hietava and teachers the world over, in countless face-to-face and over-the-shoulder interactions with schoolchildren.

Related: Ranking countries by worst students

Often, Hietava does two things simultaneously: both mentoring young student teachers and teaching his fourth grade class.

“Finland’s historic achievements in delivering educational excellence and equity to its children are the result of a national love of childhood, a profound respect for teachers as trusted professionals, and a deep understanding of how children learn best.”

Hieteva sets the classroom atmosphere. Children are allowed to slouch, wiggle and giggle from time to time if they want to, since that’s what children are biologically engineered to do, in Finland, America, Asia and everywhere else.

This is a flagship in the “ultimate charter school network” – Finland’s public schools.

Related: Why Americans should not be coming up with their own solutions to teacher preparation issues

Here, as in any other Finnish school, teachers are not strait-jacketed by bureaucrats, scripts or excessive regulations, but have the freedom to innovate and experiment as teams of trusted professionals.

Here, in contrast to the atmosphere in American public schools, Hietava and his colleagues are encouraged to constantly experiment with new approaches to improve learning.

Hietava’s latest innovations are with pilot-testing “self-assessments,” where his students write daily narratives on their learning and progress; and with “peer assessments,” a striking concept where children are carefully guided to offer positive feedback and constructive suggestions to each other.

Related: In Singapore, training teachers for the classroom of the future

The 37 year-old Hietava, a school dad and Finnish champion golfer in his spare time, has trained scores of teachers, Unlike in America, where thousands of teacher positions in inner cities are filled by candidates with five or six weeks of summer training, no teacher in Finland is allowed to lead a primary school class without a master’s degree in education, with specialization in research and classroom practice, from one of this small nation’s eleven elite graduate schools of education.

As a boy, Hietava dreamed of becoming a fighter pilot, but he grew so tall that he couldn’t safely eject from an aircraft without injuring his legs. So he entered an even more respected profession, teaching, which is the most admired job in Finland next to medical doctors.

I am “embedded” at this university as a Fulbright Scholar and university lecturer, as a classroom observer, and as the father of a second grader who attends this school.

Related: Schools exacerbate the growing achievement gap between rich and poor, a 33-country study finds

How did I wind up here in Europe’s biggest national forest, on the edge of the Western world in Joensuu, Finland, the last, farthest-east sizable town in the EU before you hit the guard towers of the Russian border?

In 2012, while helping civil rights hero James Meredith write his memoir “ A Mission From God ,” we interviewed a panel of America’s greatest education experts and asked them for their ideas on improving America’s public schools.

One of the experts, the famed Professor Howard Gardner of the Harvard University Graduate School of Education, told us, “Learn from Finland, which has the most effective schools and which does just about the opposite of what we are doing in the United States. You can read about what Finland has accomplished in ‘Finnish Lessons’ by Pasi Sahlberg.”

Related: While the U.S. struggles, Sweden pushes older students back to college

I read the book and met with Sahlberg, a former Finnish math teacher who is now also at Harvard’s education school as Visiting Professor.

After speaking with him I decided I had to give my own now-eight-year old child a public school experience in what seemed to be the most child-centered, most evidence-based, and most effective primary school system in the world.

Now, after watching Jussi Hietava and other Finnish educators in action for five months, I have come to realize that Finland’s historic achievements in delivering educational excellence and equity to its children are the result of a national love of childhood, a profound respect for teachers as trusted professionals, and a deep understanding of how children learn best.

Related: In Norway, where college is free, children of uneducated parents still don’t go

Children at this and other Finnish public schools are given not only basic subject instruction in math, language and science, but learning-through-play-based preschools and kindergartens, training in second languages, arts, crafts, music, physical education, ethics, and, amazingly, as many as four outdoor free-play breaks per day, each lasting 15 minutes between classes, no matter how cold or wet the weather is. Educators and parents here believe that these breaks are a powerful engine of learning that improves almost all the “metrics” that matter most for children in school – executive function, concentration and cognitive focus, behavior, well-being, attendance, physical health, and yes, test scores, too.

The homework load for children in Finland varies by teacher, but is lighter overall than most other developed countries. This insight is supported by research, which has found little academic benefit in childhood for any more than brief sessions of homework until around high school.

Related: Demark pushes to make students graduate on time

There are some who argue that since Finland has less socio-economic diversity than, for example, the United States, there’s little to learn here. But Finland’s success is not a “Nordic thing,” since Finland significantly out-achieves its “cultural control group” countries like Norway and Sweden on international benchmarks. And Finland’s size, immigration and income levels are roughly similar to those of a number of American states, where the bulk of education policy is implemented.

There are also those who would argue that this kind of approach wouldn’t work in America’s inner city schools, which instead need “no excuses,” boot-camp drilling-and-discipline, relentless standardized test prep, Stakhanovian workloads and stress-and-fear-based “rigor.”

But what if the opposite is true?

What if many of Finland’s educational practices are not cultural quirks or non-replicable national idiosyncrasies — but are instead bare-minimum global best practices that all our children urgently need, especially those children in high-poverty schools?

Related: China downturn, increased competition could affect supply of foreign students

Finland has, like any other nation, a unique culture. But it has identified, often by studying historical educational research and practices that originated in the United States, many fundamental childhood education insights that can inspire, and be tested and adapted by, any other nation.

As Pasi Sahlberg has pointed out, “If you come to Finland, you’ll see how great American schools could be.”

Finland’s education system is hardly perfect, and its schools and society are entering a period of huge budget and social pressures. Reading levels among children have dropped off. Some advanced learners feel bored in school. Finland has launched an expensive, high-risk national push toward universal digitalization and tabletization of childhood education that has little basis in evidence and flies in the face of a recent major OECD study that found very little academic benefit for school children from most classroom technology.

Related: In Brazil, fast-growing universities mirror the U.S. wealth divide

But as a parent or prospective parent, I have spent time in many of the most prestigious private schools in New York City and toured many of the city’s public school classrooms, in the largest public school system in the world. And I am convinced that the primary school education my child is getting in the Normaalikoulu in Joensuu is on a par with, or far surpasses, that available at any other school I’ve seen.

I have a suggestion for every philanthropist, parent, educator and policymaker in the world who wants to improve children’s education.

Start by coming to Finland. Spend some time sitting in the back of Jussi Hietava’s classroom, or any other Finnish classroom.

If you look closely and open your mind, you may see the School of Tomorrow.

William Doyle is a 2015-2016 Fulbright Scholar and New York Times bestselling author from New York City on the faculty of the University of Eastern Finland, and father of an eight year old who attends a Finnish public school.

Related articles

The Hechinger Report provides in-depth, fact-based, unbiased reporting on education that is free to all readers. But that doesn't mean it's free to produce. Our work keeps educators and the public informed about pressing issues at schools and on campuses throughout the country. We tell the whole story, even when the details are inconvenient. Help us keep doing that.

Join us today.

William Doyle

William... More by William Doyle

Letters to the Editor

At The Hechinger Report, we publish thoughtful letters from readers that contribute to the ongoing discussion about the education topics we cover. Please read our guidelines for more information. We will not consider letters that do not contain a full name and valid email address. You may submit news tips or ideas here without a full name, but not letters.

By submitting your name, you grant us permission to publish it with your letter. We will never publish your email address. You must fill out all fields to submit a letter.

Enjoyed reading William Doyle’s piece on school education in Finland. Am independently developing a flexible, interdisciplinary, interactive, and affordable learning model for K-12 education in India that integrates concept learning, hands- on activities, and life skills. Look forward to read more on new thinking in learning and education!

> But it has identified, often by studying historical educational research and practices that originated in the United States, many fundamental childhood education insights that can inspire, and be tested and adapted by, any other nation.

Can you elaborate on this? Did Finland learn from specific research that originated from the USA or studies from the USA? If so, which ones?

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Sign me up for the newsletter!

Submit a letter

What Americans Keep Ignoring About Finland's School Success

The Scandinavian country is an education superpower because it values equality more than excellence.

Everyone agrees the United States needs to improve its education system dramatically, but how? One of the hottest trends in education reform lately is looking at the stunning success of the West's reigning education superpower, Finland. Trouble is, when it comes to the lessons that Finnish schools have to offer, most of the discussion seems to be missing the point.

The small Nordic country of Finland used to be known -- if it was known for anything at all -- as the home of Nokia, the mobile phone giant. But lately Finland has been attracting attention on global surveys of quality of life -- Newsweek ranked it number one last year -- and Finland's national education system has been receiving particular praise, because in recent years Finnish students have been turning in some of the highest test scores in the world.

Finland's schools owe their newfound fame primarily to one study: the PISA survey , conducted every three years by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The survey compares 15-year-olds in different countries in reading, math, and science. Finland has ranked at or near the top in all three competencies on every survey since 2000, neck and neck with superachievers such as South Korea and Singapore. In the most recent survey in 2009 Finland slipped slightly, with students in Shanghai, China, taking the best scores, but the Finns are still near the very top. Throughout the same period, the PISA performance of the United States has been middling, at best.

Compared with the stereotype of the East Asian model -- long hours of exhaustive cramming and rote memorization -- Finland's success is especially intriguing because Finnish schools assign less homework and engage children in more creative play. All this has led to a continuous stream of foreign delegations making the pilgrimage to Finland to visit schools and talk with the nation's education experts, and constant coverage in the worldwide media marveling at the Finnish miracle.

So there was considerable interest in a recent visit to the U.S. by one of the leading Finnish authorities on education reform, Pasi Sahlberg, director of the Finnish Ministry of Education's Center for International Mobility and author of the new book Finnish Lessons: What Can the World Learn from Educational Change in Finland? Earlier this month, Sahlberg stopped by the Dwight School in New York City to speak with educators and students, and his visit received national media attention and generated much discussion.

And yet it wasn't clear that Sahlberg's message was actually getting through. As Sahlberg put it to me later, there are certain things nobody in America really wants to talk about.

During the afternoon that Sahlberg spent at the Dwight School, a photographer from the New York Times jockeyed for position with Dan Rather's TV crew as Sahlberg participated in a roundtable chat with students. The subsequent article in the Times about the event would focus on Finland as an "intriguing school-reform model."

Yet one of the most significant things Sahlberg said passed practically unnoticed. "Oh," he mentioned at one point, "and there are no private schools in Finland."

This notion may seem difficult for an American to digest, but it's true. Only a small number of independent schools exist in Finland, and even they are all publicly financed. None is allowed to charge tuition fees. There are no private universities, either. This means that practically every person in Finland attends public school, whether for pre-K or a Ph.D.

The irony of Sahlberg's making this comment during a talk at the Dwight School seemed obvious. Like many of America's best schools, Dwight is a private institution that costs high-school students upward of $35,000 a year to attend -- not to mention that Dwight, in particular, is run for profit, an increasing trend in the U.S. Yet no one in the room commented on Sahlberg's statement. I found this surprising. Sahlberg himself did not.

Sahlberg knows what Americans like to talk about when it comes to education, because he's become their go-to guy in Finland. The son of two teachers, he grew up in a Finnish school. He taught mathematics and physics in a junior high school in Helsinki, worked his way through a variety of positions in the Finnish Ministry of Education, and spent years as an education expert at the OECD, the World Bank, and other international organizations.

Now, in addition to his other duties, Sahlberg hosts about a hundred visits a year by foreign educators, including many Americans, who want to know the secret of Finland's success. Sahlberg's new book is partly an attempt to help answer the questions he always gets asked.

From his point of view, Americans are consistently obsessed with certain questions: How can you keep track of students' performance if you don't test them constantly? How can you improve teaching if you have no accountability for bad teachers or merit pay for good teachers? How do you foster competition and engage the private sector? How do you provide school choice?

The answers Finland provides seem to run counter to just about everything America's school reformers are trying to do.

For starters, Finland has no standardized tests. The only exception is what's called the National Matriculation Exam, which everyone takes at the end of a voluntary upper-secondary school, roughly the equivalent of American high school.

Instead, the public school system's teachers are trained to assess children in classrooms using independent tests they create themselves. All children receive a report card at the end of each semester, but these reports are based on individualized grading by each teacher. Periodically, the Ministry of Education tracks national progress by testing a few sample groups across a range of different schools.

As for accountability of teachers and administrators, Sahlberg shrugs. "There's no word for accountability in Finnish," he later told an audience at the Teachers College of Columbia University. "Accountability is something that is left when responsibility has been subtracted."

For Sahlberg what matters is that in Finland all teachers and administrators are given prestige, decent pay, and a lot of responsibility. A master's degree is required to enter the profession, and teacher training programs are among the most selective professional schools in the country. If a teacher is bad, it is the principal's responsibility to notice and deal with it.

And while Americans love to talk about competition, Sahlberg points out that nothing makes Finns more uncomfortable. In his book Sahlberg quotes a line from Finnish writer named Samuli Paronen: "Real winners do not compete." It's hard to think of a more un-American idea, but when it comes to education, Finland's success shows that the Finnish attitude might have merits. There are no lists of best schools or teachers in Finland. The main driver of education policy is not competition between teachers and between schools, but cooperation.

Finally, in Finland, school choice is noticeably not a priority, nor is engaging the private sector at all. Which brings us back to the silence after Sahlberg's comment at the Dwight School that schools like Dwight don't exist in Finland.

"Here in America," Sahlberg said at the Teachers College, "parents can choose to take their kids to private schools. It's the same idea of a marketplace that applies to, say, shops. Schools are a shop and parents can buy what ever they want. In Finland parents can also choose. But the options are all the same."

Herein lay the real shocker. As Sahlberg continued, his core message emerged, whether or not anyone in his American audience heard it.

Decades ago, when the Finnish school system was badly in need of reform, the goal of the program that Finland instituted, resulting in so much success today, was never excellence. It was equity.

Since the 1980s, the main driver of Finnish education policy has been the idea that every child should have exactly the same opportunity to learn, regardless of family background, income, or geographic location. Education has been seen first and foremost not as a way to produce star performers, but as an instrument to even out social inequality.

In the Finnish view, as Sahlberg describes it, this means that schools should be healthy, safe environments for children. This starts with the basics. Finland offers all pupils free school meals, easy access to health care, psychological counseling, and individualized student guidance.

In fact, since academic excellence wasn't a particular priority on the Finnish to-do list, when Finland's students scored so high on the first PISA survey in 2001, many Finns thought the results must be a mistake. But subsequent PISA tests confirmed that Finland -- unlike, say, very similar countries such as Norway -- was producing academic excellence through its particular policy focus on equity.

That this point is almost always ignored or brushed aside in the U.S. seems especially poignant at the moment, after the financial crisis and Occupy Wall Street movement have brought the problems of inequality in America into such sharp focus. The chasm between those who can afford $35,000 in tuition per child per year -- or even just the price of a house in a good public school district -- and the other "99 percent" is painfully plain to see.

Pasi Sahlberg goes out of his way to emphasize that his book Finnish Lessons is not meant as a how-to guide for fixing the education systems of other countries. All countries are different, and as many Americans point out, Finland is a small nation with a much more homogeneous population than the United States.

Yet Sahlberg doesn't think that questions of size or homogeneity should give Americans reason to dismiss the Finnish example. Finland is a relatively homogeneous country -- as of 2010, just 4.6 percent of Finnish residents had been born in another country, compared with 12.7 percent in the United States. But the number of foreign-born residents in Finland doubled during the decade leading up to 2010, and the country didn't lose its edge in education. Immigrants tended to concentrate in certain areas, causing some schools to become much more mixed than others, yet there has not been much change in the remarkable lack of variation between Finnish schools in the PISA surveys across the same period.

Samuel Abrams, a visiting scholar at Columbia University's Teachers College, has addressed the effects of size and homogeneity on a nation's education performance by comparing Finland with another Nordic country: Norway. Like Finland, Norway is small and not especially diverse overall, but unlike Finland it has taken an approach to education that is more American than Finnish. The result? Mediocre performance in the PISA survey. Educational policy, Abrams suggests, is probably more important to the success of a country's school system than the nation's size or ethnic makeup.

Indeed, Finland's population of 5.4 million can be compared to many an American state -- after all, most American education is managed at the state level. According to the Migration Policy Institute , a research organization in Washington, there were 18 states in the U.S. in 2010 with an identical or significantly smaller percentage of foreign-born residents than Finland.

What's more, despite their many differences, Finland and the U.S. have an educational goal in common. When Finnish policymakers decided to reform the country's education system in the 1970s, they did so because they realized that to be competitive, Finland couldn't rely on manufacturing or its scant natural resources and instead had to invest in a knowledge-based economy.

With America's manufacturing industries now in decline, the goal of educational policy in the U.S. -- as articulated by most everyone from President Obama on down -- is to preserve American competitiveness by doing the same thing. Finland's experience suggests that to win at that game, a country has to prepare not just some of its population well, but all of its population well, for the new economy. To possess some of the best schools in the world might still not be good enough if there are children being left behind.

Is that an impossible goal? Sahlberg says that while his book isn't meant to be a how-to manual, it is meant to be a "pamphlet of hope."

"When President Kennedy was making his appeal for advancing American science and technology by putting a man on the moon by the end of the 1960's, many said it couldn't be done," Sahlberg said during his visit to New York. "But he had a dream. Just like Martin Luther King a few years later had a dream. Those dreams came true. Finland's dream was that we want to have a good public education for every child regardless of where they go to school or what kind of families they come from, and many even in Finland said it couldn't be done."

Clearly, many were wrong. It is possible to create equality. And perhaps even more important -- as a challenge to the American way of thinking about education reform -- Finland's experience shows that it is possible to achieve excellence by focusing not on competition, but on cooperation, and not on choice, but on equity.

The problem facing education in America isn't the ethnic diversity of the population but the economic inequality of society, and this is precisely the problem that Finnish education reform addressed. More equity at home might just be what America needs to be more competitive abroad.

Unlocking Finland’s Secret: A Revolutionary Approach to Homework and Testing

- June 26, 2023

Did you know in recent years Finland has been hailed as a global leader in education? Well, yes Finland is consistently achieving top rankings in international assessments such as the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). One of the key aspects that sets Finland apart from other countries is its unique approach to homework and testing. Unlike traditional systems that emphasize heavy workloads and high-stakes examinations, Finland’s educational philosophy promotes a balanced and holistic learning experience. In this blog post, we will explore Finland’s innovative strategies regarding homework and testing, and discuss how these approaches contribute to the remarkable success of the Finland education system .

1. The Role of Homework in Finland:

Finland takes a remarkably different approach to homework compared to many other countries. In Finnish schools, the emphasis is not on the quantity but on the quality of homework. Instead of assigning excessive amounts of homework, Finnish educators focus on promoting meaningful and purposeful assignments that reinforce classroom learning. Homework is viewed as a tool for self-reflection, consolidation of knowledge, and promoting independent thinking. Additionally, the Finnish system recognizes the importance of free time for children to engage in recreational activities, develop social skills, and maintain a healthy work-life balance. Consequently, Finnish students have significantly less homework compared to their peers in other nations, allowing them ample time for rest, relaxation, and pursuing extracurricular interests.

Also read: What is Finnish education System?

2. Assessments in Finland:

Moving Beyond Standardized Testing: Unlike many countries that heavily rely on standardized testing as a measure of student performance, Finland adopts a more comprehensive and holistic approach to assessments. The Finnish education system prioritizes continuous evaluation and formative assessments over high-stakes exams. Teachers regularly assess students’ progress through a combination of observation, classroom discussions, project work, and practical assignments. This student-centered approach allows teachers to understand each student’s unique learning style and adapt instruction accordingly. By focusing on individual growth and providing constructive feedback, Finnish educators foster a supportive and nurturing learning environment, free from the stress and pressure associated with high-stakes testing.

3. The Benefits of Finland’s Approach:

Finland’s approach to homework and testing has several notable benefits. Firstly, by reducing the emphasis on homework, Finnish students experience less academic stress and have more time for relaxation and extracurricular activities. This balanced approach promotes overall well-being and fosters the development of well-rounded individuals. Secondly, the shift away from standardized testing allows for a more comprehensive evaluation of students’ abilities, including their critical thinking, problem-solving, and collaborative skills. This holistic assessment aligns with the needs of the 21st-century workforce, which values creativity, adaptability, and teamwork. Additionally, the focus on formative assessments provides students with regular feedback, allowing them to understand their strengths and areas for improvement, and promoting a growth mindset.

Conclusion:

Finland has revolutionized the conventional notions of education through its unique approach to homework and testing. By emphasizing purposeful homework and prioritizing holistic assessments, Finland has cultivated an educational system that nurtures well-rounded individuals, fosters critical thinking, and instills a genuine passion for learning. While every educational system faces its own challenges, Finland’s remarkable success serves as an inspiration for other nations to reassess their approaches to homework and testing. By adopting a more balanced and student-centered methodology, countries can establish educational environments that prioritize well-being, stimulate creativity, and effectively prepare students for the demands of the future. Finland’s educational paradigm shift stands as a testament to the transformative power of reimagining traditional education systems, emphasizing the vital importance of continually questioning and improving our approaches to teaching and learning. If you are interested in providing your child with a Finnish education curriculum, look no further than finlandeducationhub.com – your comprehensive resource for all your needs.

Leave A Reply Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Scandal and Gossip

- Pop Culture

- Performing Arts

- Visual Arts

Countries with Less Homework and Why More Countries Should Follow Them

Countries with less homework and why more countries should follow them: It may sound counter intuitive but studies are showing that less homework might be the right way to go in better learning.

In an ideal world, students are entitled to an evening of some revision, rest and entertainment after a whole day of study. In many school systems, however, kids are assigned tons of assignments to handle in their free time in a bid to improve their grasp of themes and keep them occupied in books.

As much as the intentions are good, more homework only keeps children drowned in books and does little in achieving the latter. A testament to this, countries with fewer homework policies have better statistics of students that join campus and even lesser dropouts.

A testament to the benefits of fewer time commitment to homework, educational systems in powerhouses like Finland and USA have adopted the policies championing for least homework with the US recommending at most 10 minutes of assignment in any unit per night.

For proper insight, here is a list of countries that embrace the motion for least homework and reasons for other countries to emulate this move. For assistance on homework and clarity on concepts, engage experts on myHomework done , thus earning your student spurs and conceptualizing various classes better.

1. Finland

On top of the list of countries giving less assignment is Finland. Apart from boasting of short school terms and extended holidays, the country limits the homework load to 2.8 hours total of homework per week.

Despite their educational system, Finland manages to rank among the top countries in math and science innovations and also with a smaller drop-out rate. Due to their approach on education, students feel a lesser burden imposed on them thus embracing learning.

Even better, Finland educational system discourages cramming of concepts and trains teachers to impart lessons to students in a matter that they all understand the information equally.

2. South Korea

Like the former, South Korea limits its homework duration per week to a maximum of 2.9 hours. By reducing the burden on students, the country boasts of more educated persons per level of education and even lesser dropout rates.

Unlike other countries, South Korea majors on continuous assessments which excel at testing the understanding of students as opposed to daily homework.

3. Japan

Among the leading countries in technology and science is Japan . Although it has the highest amount of hours for homework per week than its counterparts at 3.8 hours, the numbers are way low than the average.

Even better, the Japanese system of study trains students to gather information from social media platforms thus honing their research and creativity skills. By limiting the amounts of homework, students get to spend quality time with parents thus giving them a platform to instill morals and gain perspective for the upcoming classes.

Reasons why more countries should reduce the homework load on students

1. By assigning more homework to students, the level of anxiety increases thus leading to low motivation in school work. As such, the productivity and attitude of kids towards education is lowered which in turn leads to more dropout rates and lesser grades.

2. With alarming rates of obesity and immorality in kids, less homework creates more parent-kid time and allows kids to engage in more co-curricular activities. As such, parents get a chance to instill moral character in kids and also involve kids in sports and exercise.

3. Time off books allows kids to relax their mind thus increasing the ability to grasp more concepts hence getting the most from every session.

Apart from denying students a change for co-curricular activities, students are also deprived of social time which in turn leads to less time for parents to instill morals in children and also spikes anxiety levels in kids.

Whether more homework is helpful or not is a debatable issue. However, the burden on students leads to daunting effects. Given that academic frontiers assign lesser homework; it shows the need for change in lesser ranking countries.

Recent Posts

Customer, 57 who gunned down Houston lawyer over McDonald’s order id...

Georgia teen, 15, dies after buying fentanyl laced pill from classmate

Middle school teacher fired after student drinks her vodka thinking it...

Popular posts.

Houston attorney shot dead trying to calm down McDonald’s customer angry...

Minnesota mom stabs 2 brothers, flees with third after setting home...

Bear drags car crash victim body from Hatfield scene later euthanized

Popular categories.

- Scandal and Gossip 17884

- Pop Culture 2816

- Fashion 960

- Nightlife 550

- Visual Arts 220

- Performing Arts 213

- Eating Out 137

- Contact & Corrections:

- About S&V & Author Bio:

- Privacy Policy

- Editorial Construct:

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Finland's education ambassador spreads the word

I magine a country where children do nothing but play until they start compulsory schooling at age seven. Then, without exception, they attend comprehensives until the age of 16. Charging school fees is illegal, and so is sorting pupils into ability groups by streaming or setting. There are no inspectors, no exams until the age of 18, no school league tables, no private tuition industry, no school uniforms. Children address teachers by their first names. Even 15-year-olds do no more than 30 minutes' homework a night.

The national curriculum is confined to broad outlines. All teachers take five-year degree courses (there are no fast tracks) and, if they intend to work in primary schools, are thoroughly immersed in educational theory. They teach only four lessons daily, and their professional autonomy is sacrosanct. So attractive (some might say cushy) is a teacher's life that there are 10 applicants for every place on a primary education course, and only 10-15% drop out of a teaching career.

It sounds like Michael Gove's worst nightmare, a country where some combination of teachers' union leaders and trendy academics, "valuing Marxism, revering jargon and fighting excellence" (to use the education secretary's words), have taken over the asylum.

Yet since 2000, this same country, Finland , has consistently featured at or near the top of international league tables for educational performance, whether children are tested on literacy, numeracy or science. More than 60% of its young people enrol in higher education, roughly evenly divided between universities and polytechnics.

Even the management consultancy McKinsey, which has spearheaded the global movement for testing, "accountability" and marketisation, acknowledges that Finland is top. The country's defiance of current political orthodoxies appears to do little economic harm.

According to the World Economic Forum, Finland ranks third in the world for competitiveness thanks to the strength of its schooling, which overcomes the nation's drawbacks, in the forum's view, such as restrictive labour market regulations and high tax rates.

The story, at least for Guardian readers, sounds too good to be true. Is it possible to pick holes in it? I met Pasi Sahlberg, a rather dour (though not, I am told, by Finnish standards) 53-year-old former maths teacher and education academic, during his recent visit to London.

Sahlberg, who now heads an international centre at the education ministry, was Finland's last chief inspector of schools in the early 1990s before politicians decided that teachers could be trusted to do their jobs without Ofsted-style surveillance. "I only ever inspected one school," he says.

Now he has emerged as the global spokesman for Finnish schooling. His book, Finnish Lessons , has been translated into 15 languages, including Chinese, Russian and Arabic, and each day he receives two or three invitations from across the planet to give talks or lectures.

I met him the day after Gove had announced his plans to transform GCSEs , restoring traditional three-hour exams to their former glory. He's never met Gove, but what would he say to him if he did? "I would say: 'I am afraid, Mr Secretary, that the evidence is clear. If you rely on prescription, testing and external control over schools, they are not likely to improve. The GCSE proposals are a step backwards'."

He is similarly dismissive about Gove's enthusiasm for academies and free schools, largely modelled on those in Finland's neighbour, Sweden. "In Sweden," Sahlberg says, "everybody now agrees free schools were a mistake. The quality has not improved and equity has disappeared. If that is what Mr Gove wants, that is what he will get."

Finland hasn't always been an educational superstar. Before the 1970s, fewer than 10% continued their education until the age of 18. The schools were similar to those of England in the 1950s, only worse. After taking tests at the age of 11, children whose results were in the top 25% went mostly to private grammar schools – if their parents could afford the fees. Sahlberg himself, initially educated in a tiny village primary in northern Finland, where both his parents were teachers, was one of the last to go through this system.

By the time he left school in the mid-1970s, the move towards peruskoulu (or comprehensives), had begun, heavily influenced by British thinking. Mixed-ability teaching, teacher education reforms, abolition of the national curriculum (once 700 pages), and devolution of schooling to local authorities followed later.

While England began to dilute its comprehensive system almost as soon as it was established – in the early 1980s, the Tories introduced "parental choice" and offered subsidised places in elite private schools – Finland was further extending its ideal of the common school.

Like England, it had a vociferous lobby demanding a return to selection as well as Swedish-style free schools. Business leaders and rightwing politicians argued that comprehensives held back the gifted and talented and jeopardised the country's economic future.

But the critics were silenced early this century when the first results from the Programme for International Student Assessment (Pisa) emerged. All of a sudden, politicians and educators flocked to Finland in their hundreds, seeking the secret of its success. Finnish education became almost as big a global brand as Nokia. "Pisa stopped the arguments for privatisation and national testing," says Sahlberg. "Many say it saved the Finnish school system."

Sahlberg is reluctant to attribute Finland's economic success to its schools. "Some would say it's the other way round: we have educational success because we have economic success." To him and other Finns, equity is the schools' greatest achievement: the gap between high and low achievers is the smallest in the world and nobody talks of failing schools because there isn't that much difference between schools' results.

Sahlberg insists: "Pisa is not what we are about. League tables are not a good measure of a school system. We never aimed to be the best in education, only to have good schools for all. Equity came before a 'race to the top' mentality." Like many other educational researchers, he argues that most pupil achievement is explained by factors outside of school authorities' control and that, if politicians wish to elevate children out of poverty, they should look to other public policy areas.

Which leaves the question of whether Finnish schooling is exportable. Finland is an unusually homogeneous society: child poverty is low, and the ratio of income share between the richest 20% of the population and the poorest 20% is only a little over four-to-one, against nine-to-one in the UK. Its proportion of foreign-born citizens, moreover, is under 5%, and was much lower a decade ago.

All this, critics argue, makes it easy for Finland to put all children through comprehensives without social or educational strain. Other critics point to the Finnish language which, like Korean (South Korea is also near the top of the Pisa tables), is written almost exactly as it is pronounced. Young Finns and Koreans have little trouble with spelling, which not only makes reading and writing easier, but leaves more time for other subjects.

Sahlberg doesn't wholly dismiss either of these arguments, but suggests that other influences outside the schools are more important. Finnish adults, he says, are the world's most active readers. They take out more library books, own more books and read more newspapers than any other nation.

"Reading is part of our culture. At one time, you couldn't marry unless you could read. If you belonged to the Lutheran state church, you had to go a camp for two weeks before confirmation, as I did. I had to read the Bible and other religious books to the priest and answer questions to show I understood them. Only then could I be confirmed and only if I was confirmed could I get a licence to marry in church. That is still the case. Now, of course, you can get married anywhere, but 50 years ago there were very few options other than marrying in church and, 100 years ago, none at all."

There is another issue. Finnish education isn't quite what it seems. Exams and competitive pressures may have been eradicated from schools, leaving teachers and pupils free for the co-operative pursuit of cultural, creative and moral improvement. But this educational idyll eventually comes to an abrupt end.

Pupils who stay beyond 16, as more than 90% do, move into separate (allegedly self-selected) streams: "general" and "vocational" upper secondary schools. Though there is some crossover between the two, the vocational school students usually go to polytechnics or directly into jobs.

Only the general school – catering for what, in effect, is the academic stream – offers the 155-year-old national matriculation exam, a minimum requirement for university entry. Wholly financed from student fees (in a system in which everything else, including school meals, is completely free until university graduation), the exam comprises traditional essay-based external tests covering at least four subject areas. To study a particular subject at a particular institution, students must take yet more exams set by the universities themselves.

As Sahlberg acknowledges, Finland hasn't abolished competition; it has just moved it to a different part of the system. "It is getting tougher and tougher to reach the end points," he says. "It is the Finnish compromise."

In other words, although Finland unarguably achieves better results for more of its children than almost any other country in the world, success may (and I emphasise "may") be attributable less to its laid-back school regime than to the children's expectations of later competitive pressures. Exporting what appear to be educational success stories is a dubious enterprise, because it is so easy to misread how another country's system works and to discount its cultural background.

Sahlberg, I think, would agree. He is an odd, diffident sort of ambassador, spreading the message about "the Finnish miracle" but not really believing in the data that supposedly proves that it works. His fear now is that Finland's educational success is breeding complacency.

"Ask Finns about how our system will look in 2030, and they will say it will look like it does now. We don't have many ideas about how to renew our system. We need less formal, class-based teaching, more personalised learning, more focus on developing social and team skills. We are not talking about these things at all."

- The profile

- Michael Gove

- Education policy

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

- Close Menu Search

The Raider Wire

- Last day of school May 23

- Graduation May 20

- Finals May 20-23

- Senior breakfast and awards May 14

- Virtual Week May 6-10

Does Finland Have it Right?: Cutting Down on Homework

Homework takes up far too much time of the day for students who are also involved in extra clubs or sports. It leaves no room for time to relax at home, spend time with family or even get jobs.

December 21, 2017

After a grueling eight hours of schoolwork and learning, students should be able to go home and relax, right? Wrong. Instead, they have to spend what should be free time doing homework. On average, high school students have about 3.5 hours of homework every night. This means that students spend 11.5 hours of school and homework every day, 47.9% of their day. This is a ridiculous expectation to e for teens who are also to join clubs and involved in extracurricular. With almost half of their day being school, how are students supposed to have time for anything else?

Assuming teens get the recommended eight hours of sleep, adds up to 19.5 hours taken up of a 24 hour day. Add on to that an hour for eating, 20.5 hours. Let’s say the student is involved in a school activity or sport, which practice for three hours day. All together, adds up to 23.5 hours, giving the student just half an hour to relax, be with family, or just have time to themselves. Research shows that homework actually does not boost student achievement when and the only homework is stress. Understand that teachers will never completely eliminate homework, but they should instead focus on quality vs. quantity. , more homework would mean that the student would understand the topic, but in actuality, it really only hurts the student. Imagine you have a lump of homework sitting in front of you and you would like nothing more than to just lay down and sleep. Do you spend your time completing the work to your full ability, or do you look up the answer key because you cannot stand the idea of doing 30 math problems? Most would choose option two so they could move on to the. However, if the student saw five problems that covered what they had done in class, they would be able to complete them to their full ability, retain the information, and move onto their project without feeling overwhelmed.

Homework also has physical repercussions. With the amount of work assigned today, pulling all-nighters is not foreign to high school students. Not to mention, stress caused by too much homework results its own physical side-effects. c cause headaches , exhaustion and weight loss, which are ridiculous to experience because teacher assign too much homework.

Finland has banned homework entirely, and it has shown incredible boosts in student achievement. In fact, the graduation rate in Finland is at 93% , America falls at just 75%. They also have a rate of 2 in 3 of their students attend college, the highest rate in Europe. They also far exceed international standardized testing. Their tests scores on the PISA (Program for International Student Assessment) beat out everyone else, with them scoring n average 20 points higher than their runner up, Hong Kong. Although the success of Finland could not be solely on the fact that they do not have homework, it is still one of the main factors that differ from America and cause them to be more successful.

Banning homework clearly shows better success rates and that American students are overworked when it comes to homework. 3.5 hours of homework is completely unnecessary for student success, and teachers should heavily consider cutting down their workload for the benefit of the student body.

As a senior writing for the Raider Wire, I have learned so much that I will be forever grateful for. Although I could not be any happier to graduate and this was unfortunately...

- Senior Year Wrapped April 30, 2024

- Out April 30, 2024

- An Unexpected Finish April 30, 2024

Editorial/Opinion

Should Abstract Art Be Replaced?

Taylor Swift: Music Messiah or Lyrical Loser?

AP Gov: It’s Gotta Go

Captured Memories to Last a Lifetime

Ravioli: The Superior Pasta dish

Fun Controversial Opinions

Unveiling the Manipulator: Why Dumbledore is the true Antagonist

Quality Time is the Best Gift

Consider Letting it Linger

Revolutionizing Healthcare: Phage Therapy

The student news site of North Forsyth High School

Sun 12 May 2024

2024 newspaper of the year

@ Contact us

Your newsletters

Finland has no private schools – and its pupils perform better than British children

Finland ranked seventh in the world in oecd's student assessment chart in 2018, well above the uk and the united states, where there is a mix of private and state education.

Labour’s plan to add VAT to private school fees has refuelled a long-standing debate over state versus private education.

Rishi Sunak has accused Labour of stoking a “class war”, while the independent sector has warned of widespread closures if the plans take effect.

This system is replicated in many countries across the world. Finland , however, has no fee-paying schools at all.

Everyone from six to 18, whether in a state-run or independently-run school, is entitled to it free of charge. It’s a policy of which the Finns are particularly proud.

And it’s proven to be successful, with Finland ranked seventh in the world in 2018 on its Pisa score (the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment), well above the UK and the United States, where there is a mix of private and state education.

Parents do not contribute financially to their children’s education, and textbooks, materials, and school meals are provided free – all funded by taxpayers.

‘Education is a human right’

Pasi Sahlberg, a former teacher and policymaker in Finland turned professor of educational leadership at the University of Melbourne, Australia said Finland’s system was built on the idea “ education is considered a public service and a human right” with “equal opportunity of access to schools and universities regardless of who students are or where they live”.

He told i : “This was considered to be the central idea in having an equitable and well-functioning education system.

“In Nordic countries in general, education has been the driver of social mobility and equality in society.

“The current model of Finland’s education is still based on those common values and ideal of Nordic values where there is not much room in education for profit, especially in school education sectors.”

A relatively young nation, only gaining independence in 1917, Finland does not have embedded traditions in its education system of centuries-old public fee-paying schools.

Compulsory schooling in Finland starts at the age of seven rather than five and goes up to 18.

It began a comprehensive reform of its school system in 1970 and two years later, primary and lower secondary education (grades one to nine) became free of charge across the board. Further reforms in the early 2020s saw six-year-olds in pre-primary and upper secondary school students included in this.

It means education in Finland is now free for all Finnish citizens from pre-primary up to higher education.

Siru Korkala, senior specialist at the Finnish National Agency for Education, described the policy as the “cornerstone” of the nation’s educational policy.

“Finland’s commitment to equal access to education for all children and young people, regardless of their socioeconomic background, has been a cornerstone of its educational policy,” she told i . “By providing free education, Finland ensures that all students have equal opportunities, which can help improve overall educational standards.”

The only areas that do require any parental outlay are optional, non-compulsory activities or services, such as school trips or extracurricular activities.

Private schools in Finland

Private schools (those not operated by the government or local authorities) do exist in Finland but are mostly faith-based, Steiner, Montessori or university-run.

Of 2,100 institutions providing primary and lower secondary education, only 65 of them are private and the majority of their funding comes from the government.