Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Obesity and poverty don’t always go together

Americans overwhelmingly see obesity as a very serious public health problem, one with consequences not just for individuals but society as a whole, a new Pew Research Center report finds. But just who is obese? Research on obesity and socioeconomic status from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention throws a few twists into the common wisdom that, in the U.S. at least, obesity is primarily a disease of the poor .

Public health researchers define obesity, and overweight more generally, in terms of body mass index (BMI). A person’s BMI is his or her weight (in kilograms) divided by the square of his or her height (in meters), rounded to one decimal place. A BMI of 25 or more is considered overweight; 30 or more is considered obese.

As we first reported back in 2006 , Americans appear to have a sliding scale (so to speak) when it comes to weight, consistently underestimating their own relative to others’. For instance, only 31% of people surveyed by Pew Research earlier this month said they were overweight; most of those said they were “somewhat” or “only a little” overweight, while 63% termed their weight “just about right.” But according to the CDC, 68% of Americans are overweight, and more than a third are obese. The CDC data come from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey , an ongoing program of studies that combines interviews with standardized physical exams, including height and weight measurements.

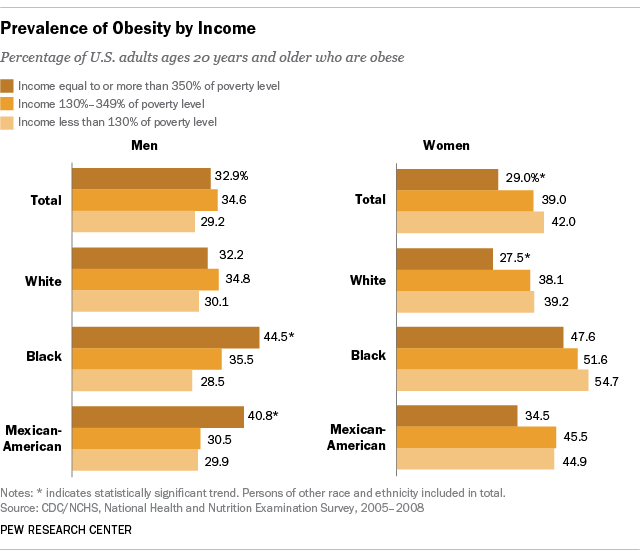

Obesity varies considerably depending on gender, race, ethnicity and socioeconomic factors. In 2010, CDC researchers (using data from 2005-08) found that among black and Mexican-American men, obesity increased with income: 44.5% and 40.8% of those men are obese, respectively, at the highest income level, compared with 28.5% and 29.9% at the lowest level. Beyond that, though, the researchers found little correlation between obesity prevalence among men and either income or education.

Among women, obesity was indeed most prevalent at lower income levels: 42% of women living in households with income below 130% of the poverty level were obese, compared with 29% of women in households at or above 350% of poverty. But the correlation was significant only for white women, though the trend was similar for all racial and ethnic groups studied. ( Poverty thresholds are set every year by the Census Bureau , and vary by family size and composition. In 2008, for instance, the poverty threshold for a single person under 65 was $11,201; for a two-adult, two-child household the threshold was $21,834.)

The most recent government report , covering 2011-12, found that obesity was significantly more common among black women (56.8%) than black men (37.1%). There was far less obesity among Asian Americans than other racial/ethnic groups: 10.8%, compared with 32.6% for whites, 42.5% for Hispanics and 47.8% for blacks. However, body shape and normal build varies by gender, race and ethnicity, and members of different demographic groups can have more or less body fat, even at the same BMI. For instance, as the researchers noted, “at a given BMI, Asian adults may have more body fat than white adults.”

After rising sharply in the 1980s and 1990s, obesity rates in the U.S. appear to have mostly leveled off in recent years. More than a third (34.9%) of U.S. adults, or 78.6 million, were obese in 2011-12, according to government data — not significantly different from the 35.7% obesity rate found in 2009-10 or the 34.2% rate found in 2007-08 .

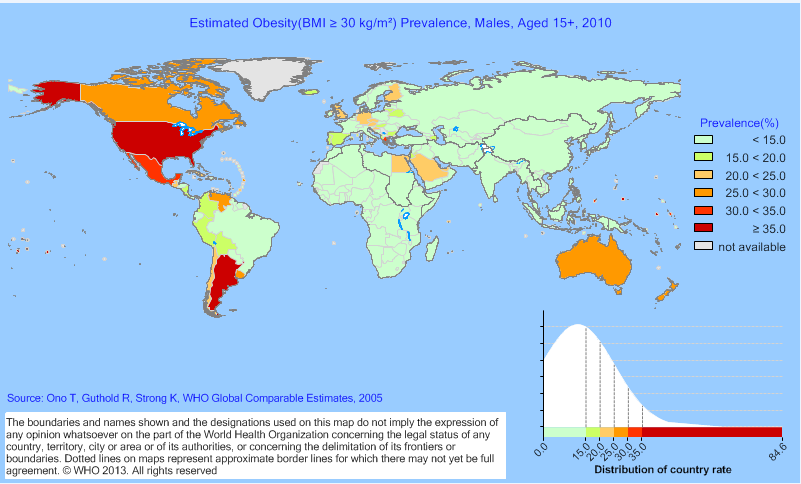

Globally, obesity is overwhelmingly a problem of developed rather than developing nations, and in few places more than in the United States. Using 2010 data, the World Health Organization estimated that 44.2% of U.S. males and 48.3% of U.S. females aged 15 and above were obese.

- Health Policy

- Medicine & Health

Drew DeSilver is a senior writer at Pew Research Center .

9 facts about Americans and marijuana

Most americans favor legalizing marijuana for medical, recreational use, how americans view the coronavirus, covid-19 vaccines amid declining levels of concern, americans’ top policy priority for 2024: strengthening the economy, 5 facts about black americans and health care , most popular.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Featured articles

- Virtual Issues

- Prize-Winning Articles

- Browse content in A - General Economics and Teaching

- Browse content in A1 - General Economics

- A11 - Role of Economics; Role of Economists; Market for Economists

- A12 - Relation of Economics to Other Disciplines

- Browse content in B - History of Economic Thought, Methodology, and Heterodox Approaches

- Browse content in B4 - Economic Methodology

- B41 - Economic Methodology

- Browse content in C - Mathematical and Quantitative Methods

- Browse content in C1 - Econometric and Statistical Methods and Methodology: General

- C10 - General

- C11 - Bayesian Analysis: General

- C12 - Hypothesis Testing: General

- C13 - Estimation: General

- C14 - Semiparametric and Nonparametric Methods: General

- C18 - Methodological Issues: General

- Browse content in C2 - Single Equation Models; Single Variables

- C22 - Time-Series Models; Dynamic Quantile Regressions; Dynamic Treatment Effect Models; Diffusion Processes

- C23 - Panel Data Models; Spatio-temporal Models

- C26 - Instrumental Variables (IV) Estimation

- Browse content in C3 - Multiple or Simultaneous Equation Models; Multiple Variables

- C31 - Cross-Sectional Models; Spatial Models; Treatment Effect Models; Quantile Regressions; Social Interaction Models

- C32 - Time-Series Models; Dynamic Quantile Regressions; Dynamic Treatment Effect Models; Diffusion Processes; State Space Models

- C33 - Panel Data Models; Spatio-temporal Models

- C36 - Instrumental Variables (IV) Estimation

- Browse content in C4 - Econometric and Statistical Methods: Special Topics

- C40 - General

- C44 - Operations Research; Statistical Decision Theory

- C45 - Neural Networks and Related Topics

- C49 - Other

- Browse content in C5 - Econometric Modeling

- C52 - Model Evaluation, Validation, and Selection

- C53 - Forecasting and Prediction Methods; Simulation Methods

- C55 - Large Data Sets: Modeling and Analysis

- Browse content in C6 - Mathematical Methods; Programming Models; Mathematical and Simulation Modeling

- C61 - Optimization Techniques; Programming Models; Dynamic Analysis

- C62 - Existence and Stability Conditions of Equilibrium

- C63 - Computational Techniques; Simulation Modeling

- Browse content in C7 - Game Theory and Bargaining Theory

- C70 - General

- C71 - Cooperative Games

- C72 - Noncooperative Games

- C73 - Stochastic and Dynamic Games; Evolutionary Games; Repeated Games

- C78 - Bargaining Theory; Matching Theory

- Browse content in C8 - Data Collection and Data Estimation Methodology; Computer Programs

- C81 - Methodology for Collecting, Estimating, and Organizing Microeconomic Data; Data Access

- Browse content in C9 - Design of Experiments

- C90 - General

- C91 - Laboratory, Individual Behavior

- C92 - Laboratory, Group Behavior

- C93 - Field Experiments

- C99 - Other

- Browse content in D - Microeconomics

- Browse content in D0 - General

- D00 - General

- D01 - Microeconomic Behavior: Underlying Principles

- D02 - Institutions: Design, Formation, Operations, and Impact

- D03 - Behavioral Microeconomics: Underlying Principles

- Browse content in D1 - Household Behavior and Family Economics

- D11 - Consumer Economics: Theory

- D12 - Consumer Economics: Empirical Analysis

- D13 - Household Production and Intrahousehold Allocation

- D14 - Household Saving; Personal Finance

- D15 - Intertemporal Household Choice: Life Cycle Models and Saving

- D18 - Consumer Protection

- Browse content in D2 - Production and Organizations

- D21 - Firm Behavior: Theory

- D22 - Firm Behavior: Empirical Analysis

- D23 - Organizational Behavior; Transaction Costs; Property Rights

- D24 - Production; Cost; Capital; Capital, Total Factor, and Multifactor Productivity; Capacity

- Browse content in D3 - Distribution

- D30 - General

- D31 - Personal Income, Wealth, and Their Distributions

- D33 - Factor Income Distribution

- Browse content in D4 - Market Structure, Pricing, and Design

- D40 - General

- D42 - Monopoly

- D43 - Oligopoly and Other Forms of Market Imperfection

- D44 - Auctions

- D47 - Market Design

- Browse content in D5 - General Equilibrium and Disequilibrium

- D50 - General

- D52 - Incomplete Markets

- Browse content in D6 - Welfare Economics

- D60 - General

- D61 - Allocative Efficiency; Cost-Benefit Analysis

- D62 - Externalities

- D63 - Equity, Justice, Inequality, and Other Normative Criteria and Measurement

- D64 - Altruism; Philanthropy

- Browse content in D7 - Analysis of Collective Decision-Making

- D70 - General

- D71 - Social Choice; Clubs; Committees; Associations

- D72 - Political Processes: Rent-seeking, Lobbying, Elections, Legislatures, and Voting Behavior

- D73 - Bureaucracy; Administrative Processes in Public Organizations; Corruption

- D74 - Conflict; Conflict Resolution; Alliances; Revolutions

- D78 - Positive Analysis of Policy Formulation and Implementation

- Browse content in D8 - Information, Knowledge, and Uncertainty

- D80 - General

- D81 - Criteria for Decision-Making under Risk and Uncertainty

- D82 - Asymmetric and Private Information; Mechanism Design

- D83 - Search; Learning; Information and Knowledge; Communication; Belief; Unawareness

- D84 - Expectations; Speculations

- D85 - Network Formation and Analysis: Theory

- D86 - Economics of Contract: Theory

- D87 - Neuroeconomics

- D89 - Other

- Browse content in D9 - Micro-Based Behavioral Economics

- D90 - General

- D91 - Role and Effects of Psychological, Emotional, Social, and Cognitive Factors on Decision Making

- D92 - Intertemporal Firm Choice, Investment, Capacity, and Financing

- Browse content in E - Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Browse content in E0 - General

- E01 - Measurement and Data on National Income and Product Accounts and Wealth; Environmental Accounts

- E02 - Institutions and the Macroeconomy

- E1 - General Aggregative Models

- Browse content in E2 - Consumption, Saving, Production, Investment, Labor Markets, and Informal Economy

- E20 - General

- E21 - Consumption; Saving; Wealth

- E22 - Investment; Capital; Intangible Capital; Capacity

- E23 - Production

- E24 - Employment; Unemployment; Wages; Intergenerational Income Distribution; Aggregate Human Capital; Aggregate Labor Productivity

- E25 - Aggregate Factor Income Distribution

- E26 - Informal Economy; Underground Economy

- E27 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in E3 - Prices, Business Fluctuations, and Cycles

- E30 - General

- E31 - Price Level; Inflation; Deflation

- E32 - Business Fluctuations; Cycles

- E37 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in E4 - Money and Interest Rates

- E43 - Interest Rates: Determination, Term Structure, and Effects

- E44 - Financial Markets and the Macroeconomy

- Browse content in E5 - Monetary Policy, Central Banking, and the Supply of Money and Credit

- E51 - Money Supply; Credit; Money Multipliers

- E52 - Monetary Policy

- E58 - Central Banks and Their Policies

- Browse content in E6 - Macroeconomic Policy, Macroeconomic Aspects of Public Finance, and General Outlook

- E61 - Policy Objectives; Policy Designs and Consistency; Policy Coordination

- E62 - Fiscal Policy

- E63 - Comparative or Joint Analysis of Fiscal and Monetary Policy; Stabilization; Treasury Policy

- E65 - Studies of Particular Policy Episodes

- Browse content in F - International Economics

- Browse content in F0 - General

- F01 - Global Outlook

- F02 - International Economic Order and Integration

- Browse content in F1 - Trade

- F10 - General

- F11 - Neoclassical Models of Trade

- F12 - Models of Trade with Imperfect Competition and Scale Economies; Fragmentation

- F13 - Trade Policy; International Trade Organizations

- F14 - Empirical Studies of Trade

- F15 - Economic Integration

- F16 - Trade and Labor Market Interactions

- F17 - Trade Forecasting and Simulation

- Browse content in F2 - International Factor Movements and International Business

- F20 - General

- F21 - International Investment; Long-Term Capital Movements

- F22 - International Migration

- F23 - Multinational Firms; International Business

- Browse content in F3 - International Finance

- F31 - Foreign Exchange

- F32 - Current Account Adjustment; Short-Term Capital Movements

- F33 - International Monetary Arrangements and Institutions

- F34 - International Lending and Debt Problems

- F35 - Foreign Aid

- Browse content in F4 - Macroeconomic Aspects of International Trade and Finance

- F41 - Open Economy Macroeconomics

- F42 - International Policy Coordination and Transmission

- F43 - Economic Growth of Open Economies

- F45 - Macroeconomic Issues of Monetary Unions

- Browse content in F5 - International Relations, National Security, and International Political Economy

- F50 - General

- F51 - International Conflicts; Negotiations; Sanctions

- F52 - National Security; Economic Nationalism

- F55 - International Institutional Arrangements

- Browse content in F6 - Economic Impacts of Globalization

- F60 - General

- F61 - Microeconomic Impacts

- F66 - Labor

- F68 - Policy

- Browse content in G - Financial Economics

- Browse content in G0 - General

- G01 - Financial Crises

- Browse content in G1 - General Financial Markets

- G10 - General

- G11 - Portfolio Choice; Investment Decisions

- G12 - Asset Pricing; Trading volume; Bond Interest Rates

- G15 - International Financial Markets

- Browse content in G2 - Financial Institutions and Services

- G20 - General

- G21 - Banks; Depository Institutions; Micro Finance Institutions; Mortgages

- G24 - Investment Banking; Venture Capital; Brokerage; Ratings and Ratings Agencies

- G28 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in G3 - Corporate Finance and Governance

- G30 - General

- G31 - Capital Budgeting; Fixed Investment and Inventory Studies; Capacity

- G32 - Financing Policy; Financial Risk and Risk Management; Capital and Ownership Structure; Value of Firms; Goodwill

- G33 - Bankruptcy; Liquidation

- G34 - Mergers; Acquisitions; Restructuring; Corporate Governance

- Browse content in G4 - Behavioral Finance

- G41 - Role and Effects of Psychological, Emotional, Social, and Cognitive Factors on Decision Making in Financial Markets

- Browse content in G5 - Household Finance

- G51 - Household Saving, Borrowing, Debt, and Wealth

- G53 - Financial Literacy

- Browse content in H - Public Economics

- Browse content in H0 - General

- H00 - General

- Browse content in H1 - Structure and Scope of Government

- H11 - Structure, Scope, and Performance of Government

- H12 - Crisis Management

- Browse content in H2 - Taxation, Subsidies, and Revenue

- H20 - General

- H21 - Efficiency; Optimal Taxation

- H22 - Incidence

- H23 - Externalities; Redistributive Effects; Environmental Taxes and Subsidies

- H24 - Personal Income and Other Nonbusiness Taxes and Subsidies; includes inheritance and gift taxes

- H25 - Business Taxes and Subsidies

- H26 - Tax Evasion and Avoidance

- Browse content in H3 - Fiscal Policies and Behavior of Economic Agents

- H30 - General

- H31 - Household

- Browse content in H4 - Publicly Provided Goods

- H41 - Public Goods

- H42 - Publicly Provided Private Goods

- H44 - Publicly Provided Goods: Mixed Markets

- Browse content in H5 - National Government Expenditures and Related Policies

- H50 - General

- H51 - Government Expenditures and Health

- H52 - Government Expenditures and Education

- H53 - Government Expenditures and Welfare Programs

- H54 - Infrastructures; Other Public Investment and Capital Stock

- H55 - Social Security and Public Pensions

- H56 - National Security and War

- H57 - Procurement

- Browse content in H6 - National Budget, Deficit, and Debt

- H62 - Deficit; Surplus

- H63 - Debt; Debt Management; Sovereign Debt

- H68 - Forecasts of Budgets, Deficits, and Debt

- Browse content in H7 - State and Local Government; Intergovernmental Relations

- H71 - State and Local Taxation, Subsidies, and Revenue

- H72 - State and Local Budget and Expenditures

- H75 - State and Local Government: Health; Education; Welfare; Public Pensions

- H76 - State and Local Government: Other Expenditure Categories

- H77 - Intergovernmental Relations; Federalism; Secession

- Browse content in H8 - Miscellaneous Issues

- H87 - International Fiscal Issues; International Public Goods

- Browse content in I - Health, Education, and Welfare

- Browse content in I1 - Health

- I10 - General

- I11 - Analysis of Health Care Markets

- I12 - Health Behavior

- I14 - Health and Inequality

- I15 - Health and Economic Development

- I18 - Government Policy; Regulation; Public Health

- I19 - Other

- Browse content in I2 - Education and Research Institutions

- I20 - General

- I21 - Analysis of Education

- I22 - Educational Finance; Financial Aid

- I23 - Higher Education; Research Institutions

- I24 - Education and Inequality

- I25 - Education and Economic Development

- I26 - Returns to Education

- I28 - Government Policy

- Browse content in I3 - Welfare, Well-Being, and Poverty

- I30 - General

- I31 - General Welfare

- I32 - Measurement and Analysis of Poverty

- I38 - Government Policy; Provision and Effects of Welfare Programs

- Browse content in J - Labor and Demographic Economics

- Browse content in J0 - General

- J00 - General

- J01 - Labor Economics: General

- J08 - Labor Economics Policies

- Browse content in J1 - Demographic Economics

- J10 - General

- J11 - Demographic Trends, Macroeconomic Effects, and Forecasts

- J12 - Marriage; Marital Dissolution; Family Structure; Domestic Abuse

- J13 - Fertility; Family Planning; Child Care; Children; Youth

- J14 - Economics of the Elderly; Economics of the Handicapped; Non-Labor Market Discrimination

- J15 - Economics of Minorities, Races, Indigenous Peoples, and Immigrants; Non-labor Discrimination

- J16 - Economics of Gender; Non-labor Discrimination

- J17 - Value of Life; Forgone Income

- J18 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J2 - Demand and Supply of Labor

- J20 - General

- J21 - Labor Force and Employment, Size, and Structure

- J22 - Time Allocation and Labor Supply

- J23 - Labor Demand

- J24 - Human Capital; Skills; Occupational Choice; Labor Productivity

- J26 - Retirement; Retirement Policies

- J28 - Safety; Job Satisfaction; Related Public Policy

- Browse content in J3 - Wages, Compensation, and Labor Costs

- J31 - Wage Level and Structure; Wage Differentials

- J32 - Nonwage Labor Costs and Benefits; Retirement Plans; Private Pensions

- J33 - Compensation Packages; Payment Methods

- Browse content in J4 - Particular Labor Markets

- J42 - Monopsony; Segmented Labor Markets

- J43 - Agricultural Labor Markets

- J45 - Public Sector Labor Markets

- J46 - Informal Labor Markets

- J47 - Coercive Labor Markets

- Browse content in J5 - Labor-Management Relations, Trade Unions, and Collective Bargaining

- J50 - General

- J51 - Trade Unions: Objectives, Structure, and Effects

- J53 - Labor-Management Relations; Industrial Jurisprudence

- Browse content in J6 - Mobility, Unemployment, Vacancies, and Immigrant Workers

- J61 - Geographic Labor Mobility; Immigrant Workers

- J62 - Job, Occupational, and Intergenerational Mobility

- J63 - Turnover; Vacancies; Layoffs

- J64 - Unemployment: Models, Duration, Incidence, and Job Search

- J65 - Unemployment Insurance; Severance Pay; Plant Closings

- J68 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J7 - Labor Discrimination

- J71 - Discrimination

- Browse content in K - Law and Economics

- Browse content in K1 - Basic Areas of Law

- K10 - General

- K12 - Contract Law

- K14 - Criminal Law

- Browse content in K3 - Other Substantive Areas of Law

- K36 - Family and Personal Law

- Browse content in K4 - Legal Procedure, the Legal System, and Illegal Behavior

- K40 - General

- K41 - Litigation Process

- K42 - Illegal Behavior and the Enforcement of Law

- Browse content in L - Industrial Organization

- Browse content in L0 - General

- L00 - General

- Browse content in L1 - Market Structure, Firm Strategy, and Market Performance

- L11 - Production, Pricing, and Market Structure; Size Distribution of Firms

- L12 - Monopoly; Monopolization Strategies

- L13 - Oligopoly and Other Imperfect Markets

- L14 - Transactional Relationships; Contracts and Reputation; Networks

- L15 - Information and Product Quality; Standardization and Compatibility

- L16 - Industrial Organization and Macroeconomics: Industrial Structure and Structural Change; Industrial Price Indices

- Browse content in L2 - Firm Objectives, Organization, and Behavior

- L22 - Firm Organization and Market Structure

- L25 - Firm Performance: Size, Diversification, and Scope

- L26 - Entrepreneurship

- Browse content in L3 - Nonprofit Organizations and Public Enterprise

- L31 - Nonprofit Institutions; NGOs; Social Entrepreneurship

- L32 - Public Enterprises; Public-Private Enterprises

- L33 - Comparison of Public and Private Enterprises and Nonprofit Institutions; Privatization; Contracting Out

- Browse content in L4 - Antitrust Issues and Policies

- L41 - Monopolization; Horizontal Anticompetitive Practices

- L42 - Vertical Restraints; Resale Price Maintenance; Quantity Discounts

- L44 - Antitrust Policy and Public Enterprises, Nonprofit Institutions, and Professional Organizations

- Browse content in L5 - Regulation and Industrial Policy

- L51 - Economics of Regulation

- L52 - Industrial Policy; Sectoral Planning Methods

- Browse content in L6 - Industry Studies: Manufacturing

- L60 - General

- L66 - Food; Beverages; Cosmetics; Tobacco; Wine and Spirits

- L67 - Other Consumer Nondurables: Clothing, Textiles, Shoes, and Leather Goods; Household Goods; Sports Equipment

- Browse content in L8 - Industry Studies: Services

- L81 - Retail and Wholesale Trade; e-Commerce

- L82 - Entertainment; Media

- L83 - Sports; Gambling; Recreation; Tourism

- L86 - Information and Internet Services; Computer Software

- Browse content in L9 - Industry Studies: Transportation and Utilities

- L91 - Transportation: General

- L94 - Electric Utilities

- L96 - Telecommunications

- L98 - Government Policy

- Browse content in M - Business Administration and Business Economics; Marketing; Accounting; Personnel Economics

- Browse content in M1 - Business Administration

- M10 - General

- M12 - Personnel Management; Executives; Executive Compensation

- M13 - New Firms; Startups

- Browse content in M2 - Business Economics

- M21 - Business Economics

- Browse content in M3 - Marketing and Advertising

- M30 - General

- M31 - Marketing

- Browse content in M5 - Personnel Economics

- M50 - General

- M51 - Firm Employment Decisions; Promotions

- M52 - Compensation and Compensation Methods and Their Effects

- M55 - Labor Contracting Devices

- Browse content in N - Economic History

- Browse content in N1 - Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics; Industrial Structure; Growth; Fluctuations

- N10 - General, International, or Comparative

- N12 - U.S.; Canada: 1913-

- N13 - Europe: Pre-1913

- N14 - Europe: 1913-

- N15 - Asia including Middle East

- Browse content in N2 - Financial Markets and Institutions

- N20 - General, International, or Comparative

- N23 - Europe: Pre-1913

- N26 - Latin America; Caribbean

- Browse content in N3 - Labor and Consumers, Demography, Education, Health, Welfare, Income, Wealth, Religion, and Philanthropy

- N30 - General, International, or Comparative

- N32 - U.S.; Canada: 1913-

- N33 - Europe: Pre-1913

- N34 - Europe: 1913-

- N35 - Asia including Middle East

- Browse content in N4 - Government, War, Law, International Relations, and Regulation

- N40 - General, International, or Comparative

- N41 - U.S.; Canada: Pre-1913

- N42 - U.S.; Canada: 1913-

- N43 - Europe: Pre-1913

- N44 - Europe: 1913-

- N45 - Asia including Middle East

- Browse content in N5 - Agriculture, Natural Resources, Environment, and Extractive Industries

- N50 - General, International, or Comparative

- N51 - U.S.; Canada: Pre-1913

- N53 - Europe: Pre-1913

- N55 - Asia including Middle East

- N57 - Africa; Oceania

- Browse content in N6 - Manufacturing and Construction

- N63 - Europe: Pre-1913

- Browse content in N7 - Transport, Trade, Energy, Technology, and Other Services

- N70 - General, International, or Comparative

- N71 - U.S.; Canada: Pre-1913

- N72 - U.S.; Canada: 1913-

- N73 - Europe: Pre-1913

- N75 - Asia including Middle East

- Browse content in N9 - Regional and Urban History

- N90 - General, International, or Comparative

- N92 - U.S.; Canada: 1913-

- N94 - Europe: 1913-

- N95 - Asia including Middle East

- Browse content in O - Economic Development, Innovation, Technological Change, and Growth

- Browse content in O1 - Economic Development

- O10 - General

- O11 - Macroeconomic Analyses of Economic Development

- O12 - Microeconomic Analyses of Economic Development

- O13 - Agriculture; Natural Resources; Energy; Environment; Other Primary Products

- O14 - Industrialization; Manufacturing and Service Industries; Choice of Technology

- O15 - Human Resources; Human Development; Income Distribution; Migration

- O16 - Financial Markets; Saving and Capital Investment; Corporate Finance and Governance

- O17 - Formal and Informal Sectors; Shadow Economy; Institutional Arrangements

- O18 - Urban, Rural, Regional, and Transportation Analysis; Housing; Infrastructure

- O19 - International Linkages to Development; Role of International Organizations

- Browse content in O2 - Development Planning and Policy

- O22 - Project Analysis

- O24 - Trade Policy; Factor Movement Policy; Foreign Exchange Policy

- O25 - Industrial Policy

- Browse content in O3 - Innovation; Research and Development; Technological Change; Intellectual Property Rights

- O30 - General

- O31 - Innovation and Invention: Processes and Incentives

- O32 - Management of Technological Innovation and R&D

- O33 - Technological Change: Choices and Consequences; Diffusion Processes

- O34 - Intellectual Property and Intellectual Capital

- O38 - Government Policy

- O39 - Other

- Browse content in O4 - Economic Growth and Aggregate Productivity

- O40 - General

- O41 - One, Two, and Multisector Growth Models

- O43 - Institutions and Growth

- O44 - Environment and Growth

- O47 - Empirical Studies of Economic Growth; Aggregate Productivity; Cross-Country Output Convergence

- Browse content in O5 - Economywide Country Studies

- O50 - General

- O52 - Europe

- O53 - Asia including Middle East

- O55 - Africa

- Browse content in P - Economic Systems

- Browse content in P0 - General

- P00 - General

- Browse content in P1 - Capitalist Systems

- P14 - Property Rights

- P16 - Political Economy

- Browse content in P2 - Socialist Systems and Transitional Economies

- P26 - Political Economy; Property Rights

- Browse content in P3 - Socialist Institutions and Their Transitions

- P39 - Other

- Browse content in P4 - Other Economic Systems

- P48 - Political Economy; Legal Institutions; Property Rights; Natural Resources; Energy; Environment; Regional Studies

- Browse content in P5 - Comparative Economic Systems

- P50 - General

- P51 - Comparative Analysis of Economic Systems

- Browse content in Q - Agricultural and Natural Resource Economics; Environmental and Ecological Economics

- Browse content in Q1 - Agriculture

- Q12 - Micro Analysis of Farm Firms, Farm Households, and Farm Input Markets

- Q14 - Agricultural Finance

- Q15 - Land Ownership and Tenure; Land Reform; Land Use; Irrigation; Agriculture and Environment

- Q16 - R&D; Agricultural Technology; Biofuels; Agricultural Extension Services

- Q17 - Agriculture in International Trade

- Q18 - Agricultural Policy; Food Policy

- Browse content in Q2 - Renewable Resources and Conservation

- Q23 - Forestry

- Q28 - Government Policy

- Browse content in Q3 - Nonrenewable Resources and Conservation

- Q32 - Exhaustible Resources and Economic Development

- Q33 - Resource Booms

- Browse content in Q4 - Energy

- Q41 - Demand and Supply; Prices

- Q48 - Government Policy

- Browse content in Q5 - Environmental Economics

- Q51 - Valuation of Environmental Effects

- Q52 - Pollution Control Adoption Costs; Distributional Effects; Employment Effects

- Q53 - Air Pollution; Water Pollution; Noise; Hazardous Waste; Solid Waste; Recycling

- Q54 - Climate; Natural Disasters; Global Warming

- Q55 - Technological Innovation

- Q56 - Environment and Development; Environment and Trade; Sustainability; Environmental Accounts and Accounting; Environmental Equity; Population Growth

- Q58 - Government Policy

- Browse content in R - Urban, Rural, Regional, Real Estate, and Transportation Economics

- Browse content in R1 - General Regional Economics

- R10 - General

- R11 - Regional Economic Activity: Growth, Development, Environmental Issues, and Changes

- R12 - Size and Spatial Distributions of Regional Economic Activity

- R13 - General Equilibrium and Welfare Economic Analysis of Regional Economies

- R15 - Econometric and Input-Output Models; Other Models

- Browse content in R2 - Household Analysis

- R21 - Housing Demand

- R23 - Regional Migration; Regional Labor Markets; Population; Neighborhood Characteristics

- Browse content in R3 - Real Estate Markets, Spatial Production Analysis, and Firm Location

- R30 - General

- R31 - Housing Supply and Markets

- Browse content in R4 - Transportation Economics

- R41 - Transportation: Demand, Supply, and Congestion; Travel Time; Safety and Accidents; Transportation Noise

- Browse content in R5 - Regional Government Analysis

- R52 - Land Use and Other Regulations

- R58 - Regional Development Planning and Policy

- Browse content in Z - Other Special Topics

- Browse content in Z1 - Cultural Economics; Economic Sociology; Economic Anthropology

- Z10 - General

- Z12 - Religion

- Z13 - Economic Sociology; Economic Anthropology; Social and Economic Stratification

- Z19 - Other

- Browse content in Z2 - Sports Economics

- Z20 - General

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Self-Archiving Policy

- About The Economic Journal

- About the Royal Economic Society

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

1. why is rising obesity a problem, 2. what determines food choices, 3. what can governments do to reduce obesity, 4. final comments, obesity, poverty and public policy.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Rachel Griffith, Obesity, Poverty and Public Policy, The Economic Journal , Volume 132, Issue 644, May 2022, Pages 1235–1258, https://doi.org/10.1093/ej/ueac013

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Obesity rates in the United Kingdom, and around the world, are high and rising. They are higher, and rising faster, amongst people growing up and living in deprivation. These patterns raise potential concerns about both market failures and equity. There is much that policy can do to address these concerns. However, policy can also do harm if it is poorly targeted or has unintended consequences. In order to design effective policies we need an understanding of who we are trying to target, and for what reasons. This paper provides an overview of some of the evidence, and some recent policy initiatives.

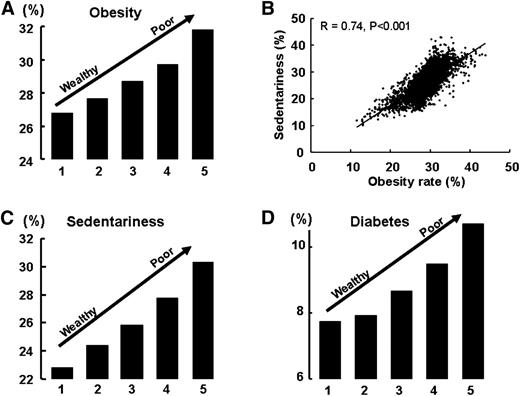

Obesity rates in the UK, and around the world, are high and rising. They are higher, and rising faster, amongst people growing up and living in deprivation. Rising obesity is a concern because it suggests that there are potential market failures that are leading people to make suboptimal choices about the foods they eat and the activities they engage in. These choices are potentially suboptimal in the sense that they may lead to higher than anticipated costs for the person themselves in the future and for wider society. Even if markets are functioning well, obesity may also potentially be a concern for equity reasons. If some children, for example those from disadvantaged backgrounds, are not able to access sufficient nourishment for healthy development, then there might be a role for policy intervention to provide greater equality of opportunity by ensuring access to a nutritious diet.

This paper provides an overview of the main evidence (and lack of evidence) on why obesity is an issue of public policy concern, what are some of the factors that might be driving rising obesity and its association with deprivation, and where policy might be most effective at improving welfare. There is much that public policy can do in terms of changing market signals, such as relative prices, and changing the choice environment to encourage people to make choices that better align with their own long-term interests. However, policy can also do harm if it is poorly targeted or has unintended consequences. In order to design effective policies we need an understanding of who we are trying to target, and for what reasons.

Obesity has risen dramatically in recent years in the UK and around the world. 1 Obesity is defined using the ‘body mass index’ (BMI), which is the ratio of weight to height squared (kilograms per |${\rm metre}^2$| ). BMI is a simple summary statistic used by medical professionals as an indicator of whether an individual is overweight (or underweight) and how overweight they are. An adult is obese when their BMI is over 30, they are morbid or severely obese when their BMI is over 40. BMI is not a perfect indicator, nor is it the only indicator that medical professionals care about. 2 For example, excess fat around the waist is another indicator. However, BMI is relatively easy to measure and track across time and locations, it is correlated with other measures, and it is seen as useful as a broad and relatively easy to measure indicator.

In England in 2018 nearly one in three adults was obese, and around one in twenty-five were morbidly obese. The rate of obesity in adults has doubled since 1993, shown in Figure 1 . Obesity rates are higher in more deprived areas (see Table 5 of NHSDigital, 2019 ). The statistics show similar trends in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland and other parts of the world.

Adult Obesity Rate in England.

Notes: Obese is defined as a BMI over 30; morbid or severely obese is defined as a BMI over 40.

Source . Table 6 of NHSDigital ( 2019 ).

Obesity in children is also high, for example, around one in five 10–11 year olds in England were obese in 2019. Worryingly, children are becoming obese at younger ages and are staying obese into adulthood (Johnson et al ., 2015 ). Obesity is more prevalent in more deprived areas, with children living in the most deprived regions being nearly twice as likely to be obese as those living in the least deprived regions. If we focus on children that are severely obese, the rate in the most deprived regions is over four times the least deprived areas (NHSDigital, 2020 ). 3

The gap in obesity rates between children growing up in the least and most deprived areas has widened over the last decade, as shown in Figure 2 . Panel (a) shows that in 2006 the gap was 8.5 percentage points; by 2019, it had grown to 13.3. Panel (b) shows that, for severely obese children, the gap between the share of children in the least and most deprived areas grew from 3.1 percentage points in 2006 to 5.3 in 2019.

Child Obesity Rate in England, by Deprivation.

Notes: Location is measured by the postcode of the child’s school. The dashed lines show 95% confidence intervals. See footnote 3 for definitions of the least and most deprived regions. Details on how obesity in children is measured is available in NHS ( 2011 ).

Source . Tables 13(a) and 14(b) of NHSDigital ( 2020 ).

Rising obesity is a concern because it suggests that there might be market failures that are leading people to make suboptimal choices. These market failures could arise if people do not fully account for the costs that obesity imposes on wider society, and on themselves, in the future when they make consumption choices. While there are many good papers that try to estimate the extent of these social costs, 4 the magnitude and nature of these costs (and in particular how they vary across different people), and what market failures are causing them, is still not fully understood. 5 However, policy-makers (and many others) believe that these costs are large, particularly amongst children, and especially amongst those growing up in deprivation.

Even if markets are functioning well, obesity may also potentially be a concern for equity reasons. Ensuring that all children, including those from disadvantaged backgrounds, are well nourished seems a corner stone of the provision of equality of opportunity. It is well established that child nutrition has important impacts on later life outcomes (see, among others, Currie, 2009 ; Almond et al ., 2018 and Lundborg et al ., 2021 ). Higher and growing rates of obesity amongst children from disadvantaged backgrounds might indicate that these children are not able to access sufficient nourishment, and suggest a role for policy intervention to provide greater equality of opportunity.

Obesity is associated with, and potentially causes, a number of adverse health, social and economic outcomes. Obesity arises due to a caloric imbalance (too many calories consumed relative to expended) leading to excess weight. It is also associated with, and might be an indicator of, a potentially unhealthy balance of nutrients, for example, a diet with too many sugars and carbohydrates. Obesity can also be associated with food insecurity (the inability to regularly access a healthy diet) if, when people do have the resources and ability to obtain food, they choose low-cost calorie-dense foods with a low nutritional value.

The main medical concern about excess weight is that it indicates an excess of fat (too much bone or muscle is not a problem). Excess fat is thought to increase an individual’s risk factor for a number of diseases, including metabolic syndrome, high blood pressure, atherosclerosis, heart disease, diabetes, high blood cholesterol, cancers and sleep disorders (NIH, 2021 ). The increased risk of these diseases likely increases costs to the healthcare system, both through an increase in the prevalence or severity of these diseases, and also because the costs of treating obese patients can be higher than normal weight individuals. Hospital admissions either directly attributable to obesity, or where obesity was a factor, are more prevalent amongst individuals from more deprived areas (NHS, 2020 ).

Obesity in childhood can have significant impacts on physical and psychological health (Sahoo et al ., 2015 ). The widening gap in obesity rates between children growing up in the least and most deprived areas raises the concern that obesity, and associated poor nutrition, may be important drivers of long-term inequalities. There is no strong causal evidence on the impact of obesity and poor nutrition on outcomes, but Public Health England (PHE) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States highlight being obese as at least correlated with long-term harms in children, for example, through increased school absences and behavioural problems. We do not have good evidence on whether these effects are all driven by poor health, which feeds through to poor social and educational outcomes, or whether other factors are also at play. But at least amongst public health officials there is a concern that as well as affecting health, childhood obesity can have potentially important consequences for children’s long-term social and economic outcomes. 6 Economists have formalised the costs and related effects that fall on the person themselves in the future as ‘internalities’ . 7 For children, they are likely too young to understand the long-term consequences of eating an unhealthy diet, and so it is not factored into their decision-making, and for some children at least, their parents may also not fully account for these effects either.

Obesity is the result of an imbalance in energy consumed and energy expended. A common question is whether it matters what type of calories you eat, or is it only calories (net of energy expended on activities) that matter? Many governments give advice on the ‘optimal’ combination of foods; 8 however, the evidence seems to suggest that many different combinations of foods can yield healthy outcomes. 9 Recently, attention has focused on processed foods as leading to poor health outcomes, rather than foods containing any particular macro nutrients. 10

Excess consumption of some types of foods is also associated, and possibly causally so, with specific diseases. For example, high consumption of foods that have a lot of ‘free sugars’ (sugars added in manufacturing) can cause insulin resistance, which can cause diabetes (Ludwig, 2002 ; Kalra and Gupta, 2014 ; Imamura et al ., 2015 ). High consumption of salt can harden your arteries, leading to high blood pressure and cardiovascular disease (Trieu et al ., 2015 ).

Excess sugar consumption has been a particular target of policy-makers around the world. To see one reason why, consider Figure 3 . The horizontal axis shows age, and the vertical access shows grams of added sugar per day. Added sugar does not include naturally occurring sugars, for example in fruit or milk. The red dashed line is the UK government’s recommended maximum daily consumption based on medical advice. The solid black line shows the mean daily consumption reported in the National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS); the dashed black lines show 95% confidence intervals. The NDNS is a continuous, cross-sectional survey. It is designed to collect detailed, quantitative information on food consumption, nutrient intake and nutritional status of the general population aged 1.5 years and over. The survey covers a representative sample of around 1,000 people per year. Respondents are asked to record consumption of all foods over two days. What is clear from panel (a) is that consumption is way above the recommended maximum at all ages, but particularly at younger ages. Panels (b)–(d) show that in fact almost all young children consume more than the medically recommended amounts of added sugar.

Sugar Consumption by Age.

Source . Panel (a) is Figure 1 , panels (b)–(d) are Figure 2 of Griffith et al . ( 2020 ), using National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS).

Another common question is—if weight gain results from eating more calories than you burn in activity, is it only calories that matter, or does increasing activity through exercise lead to weight loss? In principle yes, but the relationship between exercise and weight loss is complicated. Exercise is good for you for all sorts of reasons, but some evidence suggests that on its own it might not lead to a lot of weight loss. This is partly because you would have to increase the amount of exercise you do by quite a lot, and also because the body responds in complicated ways that might mitigate some of the effects of increasing exercise on weight loss (see, for example, Prentice and Jebb, 2004 and Jebb, 2015 ). On the other hand, the analysis in Griffith et al . (2016a ) suggests that a reduction in the strenuousness of daily life may be at least partially responsible for the increase in obesity in adults over the 1980s and 1990s in the UK.

In this section we discuss some of the important factors that determine food choices. If markets are functioning well then consumers’ choices will be determined by market prices, income and the attributes of consumption that yield (positive or negative) utility. For markets to function well requires that consumers have good information about these attributes and about the utility they generate, and that consumers can and do act on this information appropriately; it also requires that consumers can access the foods they want to buy and that prices reflect costs.

We highlight some of the possible reasons that people might be making suboptimal choices, due to market failures or resource constraints. This is important because in order to design good policy we need to understand why some people are making bad choices. In the next section we consider how some specific policies might encourage people to make better choices, or to otherwise mitigate the negative consequences of their suboptimal choices, and whether they might also have other unintended consequences.

2.1. Food Prices

The price of foods is obviously an important determinant of consumers’ choices, and many policies aim to change relatives prices of different food products or food groups in order to incentivise producers and consumers to account for the excess social costs of consumption. In this section we highlight some of the main recent trends in food prices.

2.1.1. Price levels

From the 1980s until the mid-2000s, food prices have fallen in OECD countries; see OECD ( 2020 ). In the UK, this was particularly the case (Griffith et al ., 2015 ). The reduction in food prices benefited poorer households, for whom foods represent a significant share of their budget, and a much higher proportion than for richer households. While access to cheaper food could have contributed to people eating more, increasing the overall price of food seems unlikely to be an effective way to reduce obesity or improve diet quality. It will hit the poorest hardest, and the increase would likely have to be very large to have an appreciable impact. Food prices in the UK increased dramatically in the mid-2000s due to the depreciation of the sterling, though fell back below the OECD average reasonably quickly, but now look likely to rise again due to increased trade costs due to Brexit. There is so far no indication that these large price rises are having a positive impact on health or reducing obesity.

2.1.2. Relative prices

Changing the relative prices of different foods is a policy that many governments are pursuing, for example by introducing taxes on sugar sweetened beverages. The National Food Strategy (Dimbleby, 2021 ) has recommended expanding this to a more general tax on added sugar.

How do the prices of different food products and food groups vary with the healthiness of that product? This is not a simple question to answer. One common approach is to show that the average price per calorie of more healthy products is higher than that of less healthy products. 11

However, this comparison of prices misses the key point. Why do some foods cost more than others? The price of a product depends on the interaction of supply and demand factors. If something costs more to make or grow then this will typically be reflected in a higher price. However, if there are social costs to the consumption of some foods—that is, if the costs of production do not fully reflect the costs to society of that product being consumed—then the price might be ‘too low’, in the sense that there may be a benefit (in terms of higher social welfare) if government intervened to raise the price above the market price. It is the existence of these social costs that provide a rationale for taxes on unhealthy foods, such as sugary drinks. The appropriate level of these taxes does not depend on the differences in price between healthy and unhealthy products, but on the magnitude of the social costs that are associated with the consumption of unhealthy foods.

Another reason why the price of two products that cost the same to produce might differ is if firms have market power that enables them to mark prices up above marginal cost. If one product is much more popular, and has fewer substitutes, than another, then the firm can markup the price by more. Processed foods are typically produced and sold in more concentrated markets with more advertising, so if anything, we would expect the price of these products to be marked up above marginal costs by more than products where producers have less market power.

If healthy foods are more expensive to produce, there may also be equity reasons to provide targeted subsidies to low-income households to reduce the costs of healthy foods. For example, Healthy Start Vouchers and Free School Meals (discussed further in Subsection 3.4 ) do that in the UK.

2.1.3. Time use and prices

Some foods take time to prepare, and both the technology of food product and the opportunity cost of time can affect the costs of doing this. Households may increase their time spent searching for lower prices or in home production in order to reduce the costs of consumption at some points in time (Stigler, 1961 ; Becker, 1965 ; Aguiar and Hurst, 2007 ). They may also change the composition of their shopping basket (e.g., switching from a preferred brand to a cheaper generic product) to maintain its nutritional quality for a given cost.

Several papers study the ways that households reduced the prices they paid in response to the adverse shocks to incomes and food prices over the 2007–8 recession. Unlike during previous recessions in the UK the amount that households spent on food did not keep pace with rising food prices, and this led some to infer a substantial reduction in the size and nutritional quality of households’ food baskets (see, for example, Lock et al ., 2009 ; Taylor-Robinson et al ., 2013 ), with similar concerns in the United States (US Department of Agriculture, 2010 ; US Department of Agriculture, 2013 ). Griffith et al . ( 2016b ) showed that in the UK households were able to exploit various mechanisms to smooth, or ‘insure’, the quantity and nutritional quality of their food basket in the face of these adverse shocks. Evidence from the United States suggests that, as economic conditions worsened, households spent more time shopping and thus paid lower prices (Kaplan and Menzio, 2015 ), increased their use of sales, switched to generic products (Nevo and Wong, 2019 ) and switched to low-price retailers (Coibion et al ., 2014 ).

The costs of making and eating nutritious foods is not just the money spent on buying the ingredients, but also the time spent in preparation. Griffith et al . ( 2022 ) showed that over the last several decades the share of the food budget that goes on ingredients fell, while the share on processed foods increased. This is surprising because they also showed that the market prices of ingredients declined most. The distinction between ingredients and prepared foods is particularly relevant due to the recent attention on processed foods as leading to poor health outcomes, discussed above.

Griffith et al . ( 2022 ) documented that time spent on food management, which includes shopping and cooking, declined between 1974 and 2000; Cutler et al . ( 2003 ) showed the same is true in the United States. Mean hours on food management have fallen, with women reducing time spent and men increasing time spent on these activities, but not by enough to compensate for the reduction by women. Women are spending more time in the labour market; labour force participation has increased, hours worked conditional on participation have increased and wage offers have increased. Putting these together, Griffith et al . ( 2022 ) constructed a shadow price of a home cooked meal. The shadow price reflects both the costs of purchasing the ingredients and the time needed to prepare it for consumption, where the cost of time is estimated and has increased due to outside labour market opportunities for women. Figure 4 shows that, while market prices have fallen, the shadow price—the cost of home cooked food—has increased.

Market and Shadow Prices of Foods.

Notes : The shadow price incorporates the observed wage for labour market participants, and the maximum of the estimated market wage or the estimated reservation wage for non-participants.

Source . Figure 4.2 of Griffith et al . ( 2022 ).

2.2. Income

There is clearly a strong correlation between deprivation and obesity (see Figure 2 for example), and more generally there are strong intergenerational correlations in health and income (see, for example, Case et al ., 2002 ). However, convincingly identifying the causal impacts of income on obesity and nutrition in a developed countries context remains a challenge.

A large and growing literature suggests that even relatively mild negative economic shocks in childhood can have long lasting negative impacts, although these are heterogeneous (see the survey in Almond et al ., 2018 ). For example, Hoynes et al . ( 2016 ) used the roll out of the Food Stamp Program in the United States in the 1960s and early 1970s to show that access to food stamps in childhood leads to a significant reduction in the incidence of metabolic syndrome (conditions that include obesity, high blood pressure, heart disease and diabetes) and, for women, an increase in economic self-sufficiency. However, a literature that looks at the short-run impacts of economic shocks suggests that diet quality is either not affected by, or is improved by, adverse economic conditions, 12 and Adda et al . ( 2009 ) showed that permanent income shocks have little effect on a range of health outcomes.

Another way that income and deprivation might affect the nutritional quality of individuals’ diets is through the availability of healthy foods. Many papers have documented that healthy foods are less available, or cost more, in lower income neighbourhoods—what is referred to as ‘food deserts’. 13

One important question, on which there is still limited evidence, is what is the direction of causation in this observed relationship. The food offering in any location is a result of supply and demand factors. Is the supply of healthy foods driven by restrictions to supply, or by differences in demand preferences by consumers in those locations? Allcott et al . ( 2019a ) provided evidence for the United States that it is largely differences in preferences, and not supply constraints. The answer to this is important for policy design; either response might merit policy intervention, but the effective policy will differ. Even where differences in the food offering are driven by differences in the market demand curve, it might be that individuals within a market with a restricted offering have preferences that differ from the mean, and they are affected by supply constraints.

In the next section we discuss some of the ways that income might interact with other factors to affect the way that people make decisions, and that might lead to market failures and suboptimal outcomes.

2.3. Information, Cognition, Self-Control and Advertising

In addition to prices and incomes economists have long studied the importance of information, and the ways that information is processed, in determining consumer choices (see, for example, Stigler, 1961 ; Nelson, 1970 ; Loewenstein et al ., 2014 ), and the role of information in promoting healthier food choices (see, for example, Schofield and Mullainathan, 2008 ; Wisdom et al ., 2010 ; Reutskaja et al ., 2011 ).

There is a long history of government policies that aim at providing information and education, for example, on the safety benefits of wearing seat belts and the health consequences of smoking. There have been many information campaigns on food and nutrition; in the UK these have included the Eatwell Guide, the five-a-day campaign, Change4life and nutrient labelling regulations, amongst many others.

Information campaigns will be most effective where people want, but lack, information. One important reason that some campaigns might not be that successful is if people already have the information they need (people probably already know that vegetables are good for them). However, work by behavioural economists suggests that people do not always fully pay attention to the information they have when making decisions (Bordalo et al ., 2013 ), for example, some people may group products into categories in order to reduce ‘cognitive overload’ (Mullainathan et al ., 2008 ). Work by Sendhil Mullainathan and colleagues 14 has looked at the impact of poverty on cognition. The poor often behave in less capable ways, which can perpetuate them staying in poverty. This body of work argues that poverty directly impedes cognitive function, because poverty-related concerns consume mental resources, leaving less for other tasks. The fact of being poor means that you have to cope not only with a shortfall of money, but also with many other calls on cognitive resources. This view suggests that the poor are less capable not because of inherent traits, but because the very context of poverty imposes a load of concerns on people that impedes cognitive capacity.

Another reason that people might not fully take account of all of the information available to them is that they might succumb to temptation due to self-control problems. Read and Van Leeuwen ( 1998 ) and Sadoff et al . ( 2020 ) provided some of the most direct evidence (based on experiments in the field) of self-control problems in diet. Cherchye et al . ( 2017 ) showed that, as well as some people eating a healthier diet than others, there is considerable variation in the quality of most individuals’ diets over time that cannot be explained by standard factors such as prices and incomes, and which is likely to be at least partially driven by self-control problems in food choice.

An extensive psychological literature shows that individual choice behaviour varies with context and time, and that individuals sometimes use self-regulation and behaviour modification in an attempt to mitigate these influences (see the references and discussion in Rabin, 1998 and DellaVigna, 2009 ). For example, experimental evidence suggests that individuals may be willing to impose (sometimes costly) commitments on themselves. 15 New Years’ resolutions to eat a more healthy diet are an example of a common form of self-regulation and behaviour modification with regards to diet (Dai et al ., 2014 ; 2015 ).

Figure 5 shows an example of these fluctuations in diet quality over the calendar year. Panel (a) shows variation in the nutritional quality of food purchased by a large sample of UK households. 16 This suggests a clear ‘reset’ in January of each year to a healthier diet, with a decline over the year. Panel (b) shows the same trend in Google searches for the term ‘healthy foods’.

Variation in Diet Quality.

Source . Figures 1(b) and 2(a) in Cherchye et al . ( 2017 ).

Cherchye et al . ( 2017 ) used information on individuals’ stated preferences and attitudes to investigate whether greater fluctuations in the share of calories from healthy food reflect impulsive behaviour. Their findings suggest that fluctuations are larger for individuals who state that they are more impulsive (e.g., spend money without thinking). They relate their findings to the literature that finds empirical evidence of considerable within-individual variation in choice behaviour in other settings, 17 as well as in grocery purchases using alternative identification strategies. 18 They formalise this behaviour in a two-selves model of food purchasing behaviour in the spirit of this literature, in which individuals’ food choices are the outcome of an intra-personal bargaining process between a healthy and an unhealthy self. 19

What affects might advertising have on food choices? In the economics literature advertising is modelled as either informative (it gives consumers information about a characteristic of the product) or distortionary (it gives consumers misleading information, or distracts them from information they have). 20 Informative advertising will improve the choices that consumers make, while distortionary advertising will lead to worse choices. Another important distinction for our purposes here is whether the impact of advertising is to expand the market, or whether it is largely rivalrous, leading to shifts in market share between firms within a market. If advertising expands a market then it is more likely to have adverse impacts on nutrition (if the products being advertised are less nutritious), whereas if advertising largely leads consumers to switch between products that have similar nutrient value (e.g., between Coca Cola and Pepsi) then its impact on nutrition will likely be smaller. We return to discuss this further in Subsection 3.3 .

Advertising might amplify problems of temptation and self-control; the products that are advertised most heavily are also those that are the least healthy (see, for example, the figure on UK advertising expenditure by food group in Abi-Rafeh et al ., 2021 ). Experimental evidence shows that children exposed to food advertising ate more and were more likely to be obese. 21 Advertisers can frame a consumers’ view of a product using a desirable product category, or transfer desirable attributes from other products in the same category in the consumers’ mind. For example, in the context of food advertising, a kind of chewing gum can be viewed as healthy by ‘coarse’ thinking consumers if it is advertised as low-fat (Schofield and Mullainathan, 2008 ). This may be particularly true for people living in poverty who have a lot of other things to worry about and so experience cognitive overload (Mani et al ., 2013 ).

Griffith et al . ( 2018a ) attempted to measure exposure of consumers to food advertising in the UK, and estimated that households in the lowest income quartile see something like 20% more adverts for unhealthy foods than households in the highest income quartile; this is because they watch more TV, and they watch at a time and watch TV shows on which these adverts are more likely to be shown.

Governments are considering, and have implemented, a large range of policies that change relative prices, alter the choice environment, provide information and education to consumers, incentivise firms to reformulate, encourage a more active lifestyle and more. Policies that are aimed at correcting market failures should reduce externalities (costs imposed on wider society) and internalities (costs imposed on the person themselves in the future), while minimising any unintended adverse consequences. Policies that are aimed at alleviating equity concerns should be well targeted and minimise deadweight costs.

Designing and implementing policies that meet these ambitions is difficult. 22 That does not mean that it is not worth trying, but it is important to recognise that policies can (inadvertently) do harm as well as good. For example, poorly designed taxes might fail to improve outcomes if people with high externalities or internalities do not respond, yet could impose additional costs on exactly those people it is intended to help.

3.1. Corrective Taxes

Corrective taxes are a common approach to tackle externalities. 23 Increasing the overall price of food seems unlikely to be an effective way to reduce obesity. It will hit the poorest hardest, and the increase would likely have to be very large to have an appreciable impact. Instead, corrective taxes generally aim to change relative prices , i.e., to increase the price of less healthy foods relative to more healthy foods.

To date, one of the most popular corrective taxes aimed at reducing obesity and improving nutrition is taxes on sugary soft drinks. 24 The UK introduced the Soft Drinks Industry Levy in 2018, and Dimbleby ( 2021 ) is recommending broader taxes on added sugar and salt in the UK. Griffith et al . ( 2020 ) reviewed twenty-seven studies of taxes in eleven jurisdictions—all studies find that taxes lead to increased prices—pass-through is lower in smaller jurisdictions; in settings like the UK, taxes are fully passed through to prices. Most studies find that taxes led to substantial reductions in purchases of soda. Allcott et al . ( 2019b ) provided further discussion of the evidence.

One key ingredient to understanding whether soda taxes are effective is to know whether they lead to reductions in consumption in those individuals who generate the largest externalities and internalities. Unfortunately, we do not have good estimates of the scale or distribution of externalities and internalities; this is a key piece of missing evidence. Policy-makers in the UK and elsewhere have targeted some specific groups more than others, including the young, poor and heavy sugar consumers. One question is whether these groups are responsive to taxes. If they are, and if policy-makers are right that they suffer higher internalities, then they gain in the long run due to reduced internalities, which compensates them for the loss from higher prices. However, if they are not responsive to taxes then they do not benefit from reduction in internalities, and they are made worse off because they pay higher prices.

Dubois et al . ( 2020 ) used UK data to study how well targeted taxes on sugary drinks are, and in doing so tackle a number of methodological challenges. It is important to capture heterogeneity in preferences and in responses across people, and in order to study how well targeted the policy is, to be able to relate this heterogeneity to demographics of interest. They focused on the young, poor and heavy sugar consumers because policy-makers have focused on these groups, for which they believe consumption leads to high internalities. Dubois et al . ( 2020 ) exploited longitudinal data and relaxed some of the parametric assumptions imposed by traditional methods for estimating demand in differentiated product markets. Their results show that high sugar consumers would be less responsive to a tax than low sugar consumers, but that the young are more responsive than the old, so this form of tax is well targeted in one dimension, but not the other.

O’Connell and Smith ( 2020 ) considered the design of taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages, accounting for the fact that firms have market power, showing how optimal policy depends on the relative size of price-cost margins among externality generating goods and alternative products, and the degree of consumer switching across these product sets. They showed that taking these factors into account can substantially increase the welfare improvements achieved by these taxes.

3.2. Incentivising Reformulation

Consumer information campaigns, such as those to promote greater consumption of fruit and vegetables (Stables et al ., 2002 ; Capacci and Mazzocchi, 2011 ) and reduce salt consumption (PHE, 2020b ), have been a favoured policy of governments. However, changing the behaviour of a large number of consumers can be challenging, for many of the reasons discussed above, and strong evidence on their effectiveness has been limited. Because of this, many governments have focused instead on encouraging and incentivising firms to reformulate (see, for example, Vagnoni and Prpa, 2021 ).

Griffith et al . ( 2017 ) showed that following a large public health campaign in the UK resulted in a decline in dietary salt intake but that this was entirely attributable to product reformulation; consumer switching between products worked in the opposite direction and led to a slight increase in the salt intensity of grocery products purchased.

When the UK soft drinks industry levy was introduced, an explicit aim was to encourage reformulation. The tax has two rates. Products that contain between 5–8 g of sugar per 100 mL are taxed at the rate of 18p per litre of drink, and those that contains 8 g of sugar per 100 mL or more are taxed at 24p per litre of drink. Because the tax is based on volume, not directly on sugar, the tax rate within a band declines in sugar intensity; see the dashed line in Figure 6 . The idea behind this design was to give producers incentives to reformulate to just below 8 g and just below 5 g. These points were chosen with detailed knowledge of the industry, and the technological feasibility of reformulation.

Reformulation Following the SDIL.

Notes: The dashed line shows the tax per gram of sugar under the UK Soft Drinks Industry Levy (SDIL), which was introduced on April 6, 2018. The bars are based on the Kantar (FMCG) Purchase Panel (Take Home) 2016–9 (Kantar UK, 2020 ). The figure was created in Stata using three lines of code: ‘replace sugars=sugars/100’ to make the variable gram of sugar per 100 g, ‘collapse (mean) sugars,by(rf prodcode)’ to make the data at the product (rather than transaction) level, and ‘twoway histogram sugars if (lowsugarcaloriefat==‘Regular’ |$|$| lowsugarcaloriefat==‘Standard’) & sugars |$\lt $| =20, width(0.25) lc(black) fc(black) frac |$||$| line taxpersugar sugars if (lowsugarcaloriefat==‘Regular’ |$|$| lowsugarcaloriefat==‘Standard’) & sugars |$\lt $| =20, lc(black) lp(dash) lw(thick) yaxis(2) legend(off)’ to draw the figure.

The different panels in Figure 6 show the evolution of the distribution of soft drinks available in the market by sugar intensity. Prior to the introduction of the tax (panels (a) and (b)) there was a mass point of products with around 10 g of sugar per 100 g; this is approximately the sugar intensity of a standard can of Coca Cola. After the tax (panels (c) and (d)) we see a shift towards lower sugar intensity, with a pronounced shifting to reformulate below 5 g per 100 g, the lower tax threshold, and by 2019 we see considerable bunching just below this point. 25

This result is somewhat surprising, as standard models do not suggest that the optimal tax design is tiered in this way. Nonetheless, it seems in this case that the introduction of the tax was at least associated with reformulation. However, more work is needed to understand whether this design was what caused the reformulation. What would a more standard linear corrective tax on sugar have achieved? If, for some reason, this banded design was more effective, what does it require in terms of information about the technology of production to know where to position the bands if it was to be extended to other products.

3.3. Changing the Choice Environment

A large number of policies aim to change the choice environment in which consumers make decisions, by altering the products that consumers perceive to be in their choice set, removing temptation and changing the way that information is presented. These types of policies (sometimes called ‘nudge’ policies) are attractive because they are often low cost to the policy-maker and might be less regressive than taxes (Farhi and Gabaix, 2020 ).

Regulations specify how nutritional information is presented to consumers (for example, through simpler front-of-package labelling 26 and standards of measurement), how and when products can be advertised (for example, the UK bans online advertising of products that are high in fat, sugar or salt (DCMS and DHSC, 2021 ), where products can be sold (for example, fast food outlets are restricted near schools, 27 and sugary treats are discouraged from being placed near the check out counter), amongst others.

Above we raised the possibility that advertising distorts choices, and we saw that unhealthy foods, and particularly very sugary products, are the most advertised. Dubois et al . ( 2018 ) studied the impact of banning advertising for junk food (using the market for crisps, or potato chips, as an example). They modelled consumer choice and firm behaviour, in a model where firms compete in prices and advertising. They showed that advertising affects the choices that consumers make, and affects firms’ strategic behaviours. However, in order to interpret the welfare impacts of this ban, we have to take a stance on whether advertising is informative of distortionary. 28 Dubois et al . ( 2018 ) did not have a strategy for identifying whether advertising for crisps is informative or persuasive, so they calculated the welfare impact of banning advertising in both situations.

Subjectively looking at adverts for junk food, which show sports stars and models eating crisps, it seems likely that they distract people from characteristics of the product that people do not like (for example, price and the bad health consequences of eating crisps), and lead people to choose to buy more junk food (than they would in the absence of adverts). In the case where adverts are persuasive and distort consumers’ decision-making the impact of banning junk food adverts is to lead consumers to pay more attention to the unattractive characteristics (price and unhealthiness). Because firms can no longer compete in advertising, and because consumers pay more attention to prices, price competition increases, and this leads prices to fall. So while banning persuasive advertising reduces purchases of junk foods, it also leads to a reduction in prices, which partially mitigates that impact.

In 2007 adverts for food and drink that are high in fat, salt or sugar (HFSS)—junk foods—were banned from children’s TV in the UK (see Section 8 of Conway, 2021 ). This led to a reduction in the number of adverts for HFSS that children viewed, but firms' response to the advertising restrictions partially mitigated this (Ofcom, 2010 ). Firms adapted their advertising strategies in a number of ways, such as shifting the timing of adverts to avoid showing them during children’s programs, and changed the nature of the adverts they showed. Despite the ban, most adverts that children see on TV are for junk foods (Griffith et al ., 2018a ), and because of this the UK government is currently legislating to extend restrictions to adverts for high in fat, salt or sugar (see Griffith et al ., 2019 and DHSC and DCMS, 2021 ).

3.4. Cash and In-Kind Benefits

Above we have cited evidence that poor nutrition is clearly associated with poverty, and argued that it is likely that this at least partially represents a causal relationship (although conclusive scientific evidence on this is still lacking). For example, it may be that poverty impedes cognitive functioning. Even in the absence of market failures associated with poverty, it might be that households living in poverty might not be able to obtain as nutritious of a diet as households with higher incomes. Society might take the view, particularly for children, that this is not the level of inequality we prefer, and want policies that improve the diet quality of children growing up in poverty.

Child poverty in the UK increased from 2011–2 to 2016–7, the first increase sustained over such a substantial period since the 1990s (Bourquin et al ., 2020 ). Out-of-work households are more likely to be in poverty—about 60% are in poverty, with the poverty rate in working households more like 20%. However, the share of households who are workless is reasonably low in the UK, or at least it was prior to the pandemic, so more children living in poverty are living in households with at least some work. We do not yet know the full impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, but it looks likely to be worse in households in poverty, and it may increase worklessness and poverty amongst some groups. The UK government introduced increases in benefits to help people through the pandemic; however, these were temporary (Waters and Wernham, 2021 ), and there have been large real-term cuts in the generosity of out-of-work benefits over the decade before the pandemic (Bourquin et al ., 2020 ). 29