Changing Expectations for the K-12 Teacher Workforce: Policies, Preservice Education, Professional Development, and the Workplace (2020)

Chapter: 5 preparing teachers to meet new expectations: preservice teacher education, 5 preparing teachers to meet new expectations: preservice teacher education.

As described in the previous chapters, student demographics and expectations for student learning have changed dramatically in the past two decades, and with them, the demands placed on teachers. Preservice teacher education—a vast and varied enterprise—plays a key role in preparing teacher candidates for these new conditions and increased responsibilities. Whether present approaches to teacher education fulfill that role well, and whether or not teacher education has changed in response to changes in expectations for students, have been the subjects of considerable debate. Given the size of the teacher workforce and the sheer scale of teacher education in the United States, it is perhaps not a surprise to find variation in the quality of programs or in their impact on individual graduates. Some past research has yielded critiques of teacher education as a weak intervention, largely ineffective in persuading teacher candidates of the need for deep specialized preparation or providing them with a sufficient understanding of the students they would likely be teaching ( Book, Byers, and Freeman, 1983 ; Olsen, 2008 ). Policy makers, 1 academics, and advocacy groups alike have issued sweeping critiques ( Levine, 2006 ; National Council on Teacher Quality [NCTQ], 2018).

Such all-encompassing critiques do not provide much empirically based guidance on the ways teacher preparation could be improved. There is evidence that some features of teacher preparation can make a difference with respect to teachers’ sense of efficacy ( Darling-Hammond, Chung, and

___________________

1 For remarks by Education Secretary Arne Duncan at Teachers College, Columbia University, see https://www.ed.gov/news/speeches/teacher-preparation-reforming-uncertain-profession .

Frelow, 2002 ; Ronfeldt, Schwarz, and Jacob, 2014 ) and with teachers’ retention in the profession ( Ingersoll, Merrill, and May, 2014 ; Ronfeldt, Schwarz, and Jacob, 2014 ). For example, a requirement of a capstone project as part of teacher preparation is associated with teachers’ students exhibiting greater test score gains ( Boyd et al., 2009 ).

States and institutions have undertaken initiatives to strengthen the quality of preservice preparation and to develop systems of teacher accountability based on outcome measures (e.g., see Chief Council of State School Officers [CCSSO], 2017 ). Case study research supplies persuasive examples of programs and practices with the capacity to shape the knowledge, practices, and dispositions of novice teachers ( Boerst et al., 2011 ; Darling-Hammond and Oakes, 2019 ; Lampert et al., 2013 ). Finally, the availability of large administrative datasets in some states has enabled quantitative research that seeks to uncover the relationship between a teacher’s enrollment in a particular program and the learning subsequently demonstrated by that teacher’s students. Although the last of these developments has been controversial on multiple grounds, it may spur additional research that could fruitfully inform improvements in preservice education. 2

This chapter provides a “broad strokes” characterization of teacher education opportunities to meet new expectations and respond to changing student demographics, drawing on scholarship about what does happen in teacher preparation programs while also noting arguments about what should happen in teacher preparation programs (e.g., CCSSO, 2017 ; Darling-Hammond and Oakes, 2019 ; Espinoza et al., 2018 ), particularly with regard to producing novice teachers who are prepared to be successful with all students. It explores the range of visions promoted by teacher preparation programs and describes scholarship about preservice teacher preparation in general as well as highlights particular programs that are engaging in innovative approaches that show promise for recruiting—and supporting—teacher candidates from a diverse range of backgrounds.

The chapter also describes mechanisms for influencing preservice teacher education, provides illustrative cases of institutions and programs that represent deliberate and strategic responses to both the demographic changes and the evolving shifts in expectations for teaching and learning, and describes policies and practices designed to recruit, prepare, and retain teachers of color. It also highlights reform efforts in teacher education in recent years.

2 Goldhaber, Liddle, and Theobald (2012 , p. 34) conclude: “There is no doubt that evaluating teacher training programs based on the value-added estimates of the teachers they credential is controversial. It is true that the value-added program estimates do not provide any direct guidance on how to improve teacher preparation programs. However, it is conceivable that it is not possible to move policy toward explaining why we see these program estimates until those estimates are first quantified. Moreover, it is certainly the case that some of the policy questions that merit investigation . . . require additional data.”

In this chapter and the following two chapters, discussion is framed around the capacity of teacher education, inservice professional development, and the school workplace to:

- Recruit, prepare, and retain a diverse teacher workforce.

- Prepare and support teachers to engage students in the kind of conceptually rich, intellectually ambitious, and meaningful experience encompassed by the term “deeper learning.”

- Prepare and support teachers to work with a student population that is ethnically, racially, linguistically, culturally, and economically diverse.

- Prepare teachers to pursue equity and social justice in schools and communities.

The committee acknowledges that these goals of teacher education are closely intertwined. In particular, it is noted throughout Chapters 2 and 3 that achieving goals of “deeper learning” will require the capacity to work effectively within a diverse landscape of students, families, and communities.

A SPRAWLING LANDSCAPE

This section provides a brief overview of what might best be described (borrowing a phrase from Cochran-Smith et al., 2016 ) as a “sprawling landscape.” Amid that sprawling landscape are the contributions and limitations of existing research. This chapter identifies cases in which preservice preparation programs seem particularly well positioned to attract and prepare teachers with the capacity and disposition to meet high expectations for an increasingly diverse student population. The chapter highlights programs that are part of colleges and universities as well as programs that have evolved in organizations outside institutions of higher education.

The Scale and Variability of Preservice Teacher Education

As noted above and described in Chapter 4 , preservice teacher education is marked by a range of pathways into teaching, which vary considerably from state to state. The different interpretations of the term “alternative route” complicate how to analyze and report trends in preparation. The National Research Council ( NRC; 2010 ) report Preparing Teachers: Building Evidence for Sound Policy concluded that distinctions between “traditional” and “alternative” routes are not clearly defined, and that more variation exists within the “traditional” and “alternative” categories than between them. States vary in the definition of “alternative” they use

in federal Title II reports, and many of the “alternative” routes included in those reports are based in institutions of higher education. Yet it is worth noting that while the past 20–30 years have witnessed a proliferation of “alternative routes” (however defined—within or outside of institutions of higher education [IHEs]), the majority of prospective teachers continue to be prepared by traditional programs within IHEs. Eighty-eight percent of the organizations that offer teacher preparation programs are 2- and 4-year colleges and universities, including minority-serving institutions (see Box 5-1 ). The remaining 12 percent are school districts, nonprofit organizations, and other entities that run state-approved alternative teacher preparation programs. Alternative routes to teacher certification tend to enroll more racially diverse student populations than traditional programs ( U.S. Department of Education, 2016 ). Finally, state-level data in California reveal the

prominent place now occupied by online teacher preparation programs; in data reported for 2016–2017, five of the top six producers in that state were online programs, and the top five online producers accounted for one-third of all completers. 3

Like K–12 education in the United States, most preservice teacher education (with the exception of some online programs) is varied and localized: programs differ considerably among and within states. Programs are accredited by the states, which vary in terms of their requirements for preservice teacher candidates ( Cochran-Smith et al., 2016 ; NRC, 2010 ). Even within states, where state standards and regulations govern program

3 Detailed information can be found at https://www.ctc.ca.gov/docs/default-source/educator-prep/standards/adopted-tpes-2016.pdf?sfvrsn=0 .

accreditation and teacher licensure, programs of teacher preparation vary in size, duration, curriculum, and the nature of field experience ( NRC, 2010 ).

The discussion that follows describes general characteristics and trends in preservice teacher education over the past 20 years. It focuses in particular on characteristics that bear on the likelihood that teacher preparation programs will successfully recruit a more diverse teacher workforce and that they will develop the kind of curriculum, pedagogy, and learning experiences that are responsive to changing demographics and expectations.

What makes this task challenging is that the field lacks empirical evidence about what programs are effective, why, and for whom. Most state data systems fail to link preservice teacher candidates to inservice outcomes. Part of the problem has to do with the disagreement about what constitutes effectiveness (i.e., should indicators of effectiveness be student test scores, teacher retention rates, or closing achievement gaps among groups of students, or some other measure?). The NRC report Preparing Teachers (2010) called for research on the development of links between teacher preparation and outcomes for students, but that call has yet to be fulfilled. The problem also has to do with the difficulty in examining the causal effectiveness of teacher preparation programs, given all the confounding variables—including individual teacher traits—that might explain teacher success. The chapter instead examines qualitative research that dives deeply into program aims, characteristics of programs, innovations in practice, and accountability of programs.

The Visions of Teaching and Teachers Conveyed by Programs

The field lacks national data about the nature/substance of teacher preparation programs and the degree to which they have changed in any collective way over time, clearly signaling a critical area for research. There are, however, indicators of general shifts and developments in teacher preparation. For example, as highlighted in Chapter 2 , the past two decades can be characterized as an “era of accountability” in education generally, and in teacher education specifically, in which federal, state, and professional association policy initiatives have been aimed at measuring outcomes such as student achievement ( Cochran-Smith et al., 2018 ). This focus on outcomes is a shift from previous accountability emphases on measuring inputs ( Cochran-Smith et al., 2018 ). Even if national data are lacking, there is evidence that increased attention to standards, accreditation, and the development and growing influence of new players committed to advancing equity and justice, such as the Education Deans for Justice and Equity ( Cochran-Smith et al., 2018 ), have led to changes in teacher preparation, as reflected by case studies of programs.

A report by the National Academy of Education ( Feuer et al., 2013 ) describes the variety of organizations that conduct evaluations of the quality of teacher preparation programs in the United States, including the federal government, state governments, national organizations (e.g., accreditors), private organizations (e.g., NCTQ), and individual programs themselves. It notes that selection or development of appropriate measures is a key component of designing a study of teacher preparation program quality. The measures might include assessments of program graduates’ knowledge and skills, observations of their teaching practice, or assessments of what their pupils learn. Measures of program features could include analyses of course syllabi, qualifications of program faculty, and program uses of educational technology. The report describes general strengths and limitations of varying types of measures.

High-profile reports on teacher education (e.g., Educating School Teachers [ Levine, 2006 ] and Powerful Teacher Education: Lessons from Exemplary Programs [ Darling-Hammond, 2006 ]) have singled out specific programs as exemplars of excellence. Whereas these programs vary greatly in terms of program design, it is important to recognize that judgments about what constitutes “excellence” are often based on subjective assessments of what teacher preparation ought to look like rather than empirical, causal evidence on the effectiveness of teacher education.

Other reports describe programs that highlight particular approaches to program design, such as close connections to local communities ( Guillen and Zeichner, 2018 ; Lee, 2018 ). Scholars looking at program similarities and differences across countries also have selected and described programs because of particular features they had, such as an intention to be coherent ( Jenset, Klette, and Hammerness, 2018 ). The large international comparative study of preparation of mathematics teachers for elementary and lower secondary school ( Tatto et al., 2012 ) described features of nationally representative samples of teacher preparation programs. All of these studies provide more information about what goes on in teacher preparation, but none can support causal claims about the effects of programs or program features on desired outcomes.

In the recent volume Preparing Teachers for Deeper Learning Darling-Hammond and Oakes (2019) identify seven “exemplars” that include public and private colleges and universities, a teacher residency program, and a “new graduate school of education” embedded in a charter management organization (see Box 5-2 ). These exemplars as described in the volume suggest that they are aligned with the five principles of deeper learning: (1) learning that is developmentally grounded and personalized; (2) learning that is contextualized; (3) learning that is applied and transferred; (4) learning that occurs in productive communities of practice; and (5) learning that is equitable and oriented to social justice ( Darling-Hammond and

Oakes, 2019 , pp. 13–14). The programs are diverse across many axes but all “have track records of developing teachers who are strongly committed to all students’ learning—and to ensuring, especially, that students who struggle to learn can succeed” ( Darling-Hammond and Oakes, 2019 , p. 25). Common features of these programs are that they have a coherent set of courses and clinical experience (these programs have intensive relationships with schools and carefully matched student teaching placements that share the programs’ commitments to deeper learning and equity); instructors model powerful practices rather than lecture and teach through textbooks; there is a strong connection between theory and practice; and they use performance assessments to evaluate teacher candidates’ learning (pp. 323–324). Interpretation of key terms, such as “coherent,” “intensive relationship,” and “powerful practice,” are still matters of judgment.

Pondering the question of what would constitute a “strong intervention” in preservice teacher education requires considering the conception of teachers and teaching conveyed by teacher preparation programs. Preparing

Teachers ( NRC, 2010 , p. 44) notes, “All teacher preparation programs presumably have the goal of preparing excellent teachers, but a surprising variation is evident in their stated missions.” The sheer scale of preservice teacher education in the United States, combined with the fact that teacher preparation is governed at the state level, suggests wide variation in the degree to which a distinctive and coherent vision undergirds a given program. Although many web-based descriptions provide only vague and generic portraits of a program’s conception of teachers and teaching, some institutions and programs articulate a goal to recruit and prepare teacher candidates who fit a strongly conceptualized and distinctive vision of teaching, and describe a program designed to embody that vision.

Program Coherence and Integration

Programs of teacher education confront the challenge of preparing prospective teachers for a complex and multi-faceted professional role, one that requires not only specialized knowledge related to the subjects, grades, and students they are likely to teach but also the capacity to assume responsibilities beyond the classroom and to engage in productive communication with professionals in other specializations (social work, school psychology, health professions). Yet long-standing criticisms of teacher education point to its fragmented or “siloed” character as a limitation on the quality of preparation experienced by teacher candidates ( Ball, 2000 ; Grossman, Hammerness, and McDonald, 2009a ; Harvey et al., 2010 ; Lanier and Little, 1986 ; Scruggs, Mastropieri, and McDuffie, 2007 ; Stone and Charles, 2018 ). This siloed nature takes the form of university coursework disconnected from clinical field experience; classroom teachers being trained separately from special education teachers, social workers, school psychologists, or other specialists focused on the development and well-being of students; elementary teachers prepared separately from early childhood educators, or from middle and high school teachers; and preservice preparation segmented from induction experiences and ongoing professional development. Achieving a conceptually coherent and experientially integrated program proves challenging for teacher education programs; Darling-Hammond terms this “probably the most difficult aspect of constructing a teacher education program” (2006, p. 305), but also underscores the importance of providing teacher candidates an “almost seamless experience of learning to teach” (p. 306).

The most prominent efforts to bridge the silos in the past two decades center on strengthening the relationship between university coursework and clinical practice, and on enhancing the quality of student teachers’ field experiences. These efforts respond most directly to complaints that candidates receive little help in bridging theory and practice in their preparation, with training in content knowledge separate from training in classroom

management and pedagogy ( Ball, 2000 ). Some programs are addressing the chasm between university coursework and clinical practice by situating university courses within school sites ( Zeichner, 2010 ), with results some scholars see as promising ( Hodges and Baum, 2019 ). National associations have taken steps to promote higher quality approaches to clinical experience, closely integrated with other components of teacher preparation, as reflected most recently in the “proclamations” issued by AACTE’s Clinical Practice Commission (2018) .

CHARACTERISTICS OF TEACHER CANDIDATES

Every occupation must find ways of attracting newcomers to its ranks. The individuals who enroll in programs of teacher preparation bring with them a view of teaching as an occupation, and a set of experiences, perspectives, and motivations that shape their decision to enroll. Three developments in the past 20 years deserve particular attention, as they may shape both the capacity and motivation of new teachers to respond to changing student demographics and to expectations for teaching and learning in the 21st century. The committee offers a few illustrations of initiatives that have been started; however, the examples highlighted represent a small subset. Given time constraints, the committee was unable to offer a comprehensive review of all national efforts.

First, individuals who are now becoming teachers, with the possible exception of career changers (see Box 5-3 ), likely attended school during the era of test-based accountability. Their ideas of what it means to teach—the goals of learning, the nature of classroom instruction, the form and role of assessment, the relationships between teachers and students—may have been influenced strongly by the kinds of accountability-based instruction that evolved in the wake of No Child Left Behind (NCLB; see Chapters 2 and 3 ). Elementary instruction in particular shifted under NCLB to focus increasingly on math and reading at the expense of social studies, science, and the arts, and to emphasize narrowly defined, standardized forms of assessment ( Dee and Jacob, 2010 ; Dee, Jacob, and Schwartz, 2013 ).

A second development conceives of teaching as short-term public service. The advent of Teach For America (TFA) introduced the premise that “that young, highly educated individuals will stimulate achievement and motivation in low-performing schools, even if they remain only a short period; a corollary but more implicit premise is that high turnover of such teachers will do no harm to students or schools, presuming that programs and schools are able to recruit a steady supply” ( Little and Bartlett, 2010 , p. 310). Although teachers recruited by TFA and by similar recruitment efforts (including the hiring of overseas-trained teachers) represent a small percentage of the teacher workforce (see Chapter 4 ), they are concentrated

in high-minoritized and high-poverty schools and districts ( Bartlett, 2014 ; Clotfelder, Ladd, and Vigdor, 2005 ). More important than their numbers may be the staying power of the institutional logic of teaching as short-term service rather than a career for which one requires in-depth preparation and ongoing opportunity to learn (see Chapter 4 ).

A third development of the past two decades entails efforts to recruit a more diverse pool of teacher candidates, with respect to both teachers’ demographic characteristics (more teachers of color and male teachers) and teachers’ ability to help remedy chronic shortages in STEM fields, special education, and bilingual education (as discussed in Chapter 4 ). A report issued by the American Association of Colleges of Teacher Education (AACTE) ( King and Hampel, 2018 ) identifies several initiatives intended to diversify the workforce, including Federal TEACH grants, state-level scholarships, foundation-supported initiatives, and AACTE initiatives. Most supply financial incentives or supports, but AACTE has also adopted the idea of a Networked Improvement Community to help institutions increase the number of Black and Hispanic/Latino men (see Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, 2019 ). TFA’s current teacher corps is now half people of color ( Teach For America, 2019 ), with active recruitment from MSIs, reflecting the organization’s success in meeting one of the workforce’s top agenda items.

PREPARING TEACHERS TO ENGAGE STUDENTS IN DEEPER LEARNING

As described in Chapter 3 , teaching for deeper learning arguably requires teachers to have deep command of content knowledge (i.e., disciplinary knowledge) and specialized content knowledge for teaching (i.e., knowing how to teach disciplinary knowledge and practices), as well as strong practical training in what it means to engage and empower learners from diverse communities through culturally relevant education. Intentional, purposeful instruction in disciplinary learning is critical to developing students’ deep learning. Deeper learning also involves cultivating the disposition and ability to work effectively with a diverse population of students and families.

However, the constant refrain that teachers must be able to serve “all students” tends to emphasize academic competencies and render opaque some of the complex issues entailed in working for equity and social justice both in and beyond the classroom that in fact impact academic success ( Cochran-Smith et al., 2016 ; Darling-Hammond, 2006 ). Some “deeper learning” documents focus learning outcomes principally on academic competencies, often characterizing this as a pursuit of “excellence.” A notable example of this can be observed in the creation of particular standards such as computer science (e.g., Grover, Pea, and Cooper, 2015 ). In contrast, the five principles identified in the Darling-Hammond and Oakes (2019) book Preparing Teachers for Deeper Learning explicitly reference learning for equity and social justice. A substantial body of research suggests that each of these aims—achieving depth of understanding and skill, and catalyzing

equity and social justice—present daunting challenges and tensions that may be compounded by the tendency to address “excellence” and “equity” as divergent rather than convergent aspects of an equitable learning ecology ( Khalil and Kier, 2018 ).

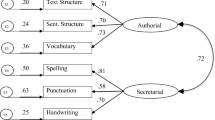

Having acknowledged this dilemma, and having underscored the intersection of the preparation goals identified here, this section concentrates on approaches that teacher preparation programs have developed to supply novice teachers with deep specialized content knowledge for teaching ( Ball, Thames, and Phelps, 2008 ) and with the ability to design and enact instruction that engages students in rich, complex, and authentic tasks. Three developments are highlighted: the movement to focus on professional practice, with particular focus on “core” or “high leverage” practices (and critiques of that movement); field experiences; and innovations in teacher education pedagogy.

Practice-Based Teacher Education

As described in Chapter 3 , developing the knowledge, skills, and dispositions to support an increasingly diverse set of learners to engage in deeper learning requires significant shifts in what teaching looks and sounds like in most U.S. classrooms. It can be challenging to support preservice teachers in shifting their conceptions of instruction so as to be able to teach in ways substantially different from those experienced as K–12 students. Over the past two decades, a growing appreciation for the multi-faceted and specialized nature of teachers’ knowledge has been joined to a richer conceptualization of the complexities of professional practice (see Box 5-4 ). Shulman (1987) introduced a taxonomy of teacher knowledge that in turn stimulated a substantial body of empirical research (especially on the nature of “pedagogical content knowledge”) as well as further conceptual refinements ( Ball, Thames, and Phelps, 2008 ; Gess-Newsome, 2015 ).

In a widely cited essay, Ball and Cohen (1999) present a compelling case for why this multi-faceted and specialized knowledge requires professional learning opportunities rooted in practice, especially if our educational system aspires to “deeper and more complex learning in students as well as teachers” (p. 5). Ball and Cohen envision professional education “ centered in the critical activities of the profession—that is, in and about the practices of teaching ,” but caution that this does not entail a simplistic recommendation to locate more of teacher preparation in schools and classrooms, where the immediacy of classroom activity may limit teachers’ ability to gain new insight into central problems of practice. Throughout, they urge (and illustrate) the thoughtful, collective analysis of well-chosen records of professional practice that include samples of student work, video-records

of classroom lessons, curriculum materials, and teachers’ plans and notes. Ball and Cohen nonetheless acknowledge that centering professional learning in an intensive consideration of practice would represent a fundamental, systemic change in the organization of teacher education and in the role of teacher educators.

Grossman and colleagues (2009b) developed a framework of the pedagogies of practice-based teacher education that elaborates on Ball and Cohen’s (1999) call to center professional education on practice. The framework is grounded in a cross-field study that included teacher education together with preparation for the clergy and for clinical psychology. It distinguishes between pedagogies of investigation , which focus on analyzing and reflecting on records of practice (e.g., video recordings, student work), and pedagogies of enactment , or “opportunities to practice elements of interactive teaching in settings of reduced complexity” ( Grossman and McDonald, 2008 , p. 190). Analyzing records of practice to reflect upon and improve teaching, while necessary, is not sufficient for supporting novices to develop the enact the “contingent, interactive aspects of teaching” ( Grossman, 2011 , p. 2837)—especially when the goals of teaching are, for many novices, substantially different from what they experienced themselves as K–12 learners (see Box 5-5 ).

One issue in practice-based teacher education entails deciding what aspects of practice to focus on with novices, and when, and why. Grossman, Hammerness, and McDonald (2009a , p. 277) argued for the value in focusing teacher education on “core practices,” which the authors describe as those that occur with high frequency in teaching; can be enacted in classrooms across different curricula or instructional approaches; allow teachers to learn more about students and about teaching; preserve the integrity and complexity of teaching; and are research-based and have the potential to improve student achievement. (See also Ball et al., 2009 for a discussion of “high-leverage practices.”)

Facilitating whole-class discussions is an example of what might count as a “core” or “high-leverage” practice. Substantial research has indicated that engaging students in whole-class discussions, in which students are supported and pressed to reason about central ideas, and to connect their ideas to those of their peers, deepens students’ understanding of content and competence with disciplinary forms of argument and reasoning (e.g., Fogo, 2014 ; Franke, Kazemi, and Battey, 2007 ; NASEM, 2018 ).

In 2012, a group of educators from multiple institutions and subject matter disciplines formed the Core Practices Consortium (CPC) to advance program innovations and a related research agenda. The premise underlying the work of the Consortium is that focusing on a selected set of core practices may better prepare novice teachers to “counter longstanding inequities in the schooling experiences of youth from historically marginalized communities in the U.S.” ( Core Practice Consortium, 2016 ). Although CPC participants share a set of commitments and understandings, the core practices they identify “vary in grain size, content-specificity, exhaustiveness, and other features” ( Grossman, 2018 , p. 4). For example, TeachingWorks, a center at the University of Michigan School of Education, identified

19 high-leverage practices that include leading a group discussion, building respectful relationships with students, and checking student understanding during and at the conclusion of lessons. A set of core science teaching practices in secondary classrooms was developed by a Delphi panel of expert science teachers and university faculty; these practices include engaging students in investigations, facilitating classroom discourse, and eliciting, assessing, and using student thinking about science ( Kloser, 2014 ). Also using a Delphi panel, a set of core teaching practices for secondary history education were developed, including employing historical evidence, the use of history concepts, big ideas, and essential questions, and making connections to personal/cultural experiences ( Fogo, 2014 ).

Some scholars have questioned the compatibility of organizing teacher education coursework around high-leverage practices with a commitment to advancing equity and social justice ( Philip et al., 2018 ; Souto-Manning, 2019 ). Dutro and Cartun (2016) argue that calling some practices “core” necessarily suggests other practices are peripheral. They suggest that while choosing to focus on routine aspects of teaching can be of great value, it is important for teacher educators to remain vigilant in interrogating what is identified as central and what is less so. Moreover, they call for teacher educators to support novices to treat and approach teaching as complex, especially when narrowing focus to a particular form of practice. Similarly concerned with what is centered and what is pushed to the periphery, Philip et al. (2018) argue that a focus on core practices may result in the parsing of teaching into discrete, highly precise skills with not enough consideration into the character and complexity of local schooling contexts, and thus “decenter justice” (p. 6).

Recent research, including studies involving scholars affiliated with CPC, has begun to shed light on the impact of the core practices approach and issues related to equity. Several studies focus on determining whether and how core practices are evident in the planning and instruction of novice teachers. For example, Kang and Windschitl (2018) conducted a mixed-methods study of the lessons taught by two groups of first-year science teachers; one group had completed a “practice-embedded” program organized around core practices, and the second group completed a program that did not feature a core practices approach. The research team found that the graduates of the practice-embedded program were significantly different from the comparison group with respect to the opportunities for student learning embodied in the lesson plans (goals, tasks, tools) and in the level of active science sense-making evident in classroom discourse (see Chapter 6 for similar findings related to inservice professional development).

In an extension of that research, Kang and Zinger (2019) explicitly take up questions regarding the relationship between preparation in core practices and outcomes centered on equity and social justice. The authors

draw on a longitudinal (3-year) case study of White women as they completed a program focused on core practices in science teaching and then in their first 2 years of teaching as they taught students from ethnically, linguistically, and economically diverse backgrounds. Even within a small case study sample of three teachers, they found variations in the teachers’ use of ambitious science teaching practices (enabled or constrained in part by their workplace context), but also found that the awareness of core practices alone did not help novice teachers adopt teaching methods that reflect a critical consciousness about racism and systemic, structural inequity. The researchers attributed these results in part to a preparation program in which coursework focused on cultural diversity and equity remained separate from coursework on science teaching methods.

In a second example, Kavanagh and Danielson (2019) investigated novice elementary teachers’ opportunities to attend to issues of social justice and facilitate text-based discussions in a literacy methods course, and the ways novices integrated the two domains when reflecting on their teaching practice. The literacy methods course was co-taught by a literacy methods instructor and a foundations instructor. Data included video recordings of the literacy methods course in which the novices prepared to teach text-based discussions (specifically in the context of interactive read-alouds), video recordings of the novices engaging elementary students in read-alouds, and novices’ written reflections on their videos.

One finding concerned differences in teacher educator pedagogies as they relate to a focus on social justice issues or content. Kavanagh and Danielson found that when teaching about facilitating a text-based discussion, teacher educators supported the novices to both analyze and try out (e.g., rehearse) specific moves one might make during an interactive read-aloud, and to reason about their instructional decisions. However, while novices engaged in conversations about social justice in relation to planning for text-based discussions (e.g., which text to select in relation to their students’ lived experiences), novices rarely engaged in discussions of social justice in relation to their actual facilitation of text-based discussions. Kavanagh and Danielson write: “When TEs . . . support[ed] teachers to attend to social justice in their teaching, justice was exclusively treated as an element of lesson planning rather than as a factor in in-the-moment instructional decision making, or instruction . . . Only on extremely rare occasions did novices discuss attending to social justice while making in-the-moment instructional decisions.” (p. 19). Further, when reflecting on video recordings of their teaching, novices discussed issues of facilitating text-based discussions much more frequently than issues of attending to social justice (p. 19).

Kavanagh and Danielson suggest that novices’ tendency to center issues of content and decenter issues of social justice when reflecting on their instructional decision-making is likely shaped by the pedagogies employed

by the teacher educators. “While [Teacher Educators] frequently represented, decomposed, and approximated practice with novices, they rarely did so when supporting novices to attend to social justice” (p. 30). On the basis of these findings, and in relation to the ongoing debates about the relationships between “core practices” and advancing social justice and equity, Kavanagh and Danielson suggest the value in understanding more deeply how teacher educators might more purposefully integrate attention to specific forms of practice (e.g., facilitating a text-based discussion) and social justice concerns (e.g., representation of students, addressing classroom power relations during a discussion) in the context of practice-based teacher education.

The Field Experience

One hallmark of professional education in all fields is its reliance on practical experience to help novices develop key skills and cultivate professional judgment. Numerous correlational studies have shown some aspects of clinical experiences to be positively associated with measures of teacher effectiveness and retention (e.g., Boyd et al., 2009 ; Goldhaber, Krieg, and Theobold, 2017 ; Krieg, Theobold, and Goldhaber, 2016 ; Ronfeldt, 2012 , 2015 ). Ronfeldt (2012 , p. 4) points to variations in the degree to which programs take an active role in selecting and overseeing field placements, citing the NYC Pathways Study 4 conducted by Boyd and colleagues (2009) as an example.

[P]rogram oversight of field experiences was positively and significantly associated with teacher effects. More specifically, new teachers who graduated from programs that were actively involved in selecting field placements had minimum experience thresholds for cooperating teachers and required supervisors to observe student teachers at least five times had higher student achievement gains in their first year as teacher of record.

Recent scholarship points to the relationship between field experience and teacher candidates’ perceptions of the quality of their program and their preparedness to teach. Using longitudinal data from the Schools and Staffing Survey, Ronfeldt, Schwarz, and Jacob (2014) found that teachers who completed more methods-related coursework and practice teaching felt they were better prepared and were more likely to stay in teaching. These findings applied to teachers no matter what preparation route they

4 The NYC Pathways Study reviewed the entry points for teachers in New York City through an analysis of more than 30 programs, including a survey of all first-year teachers. The study examined the differences in the components of the teacher preparation programs and examined the effects related to student achievement.

took. In an experimental study of a project called Improving Student Teaching Initiative (ISTI), Ronfeldt et al. (2018) found that teachers randomly assigned to placements evaluated as more promising rather than less promising (in terms of various measures of teacher and school characteristics) had higher perceptions of the quality of the instruction of their mentor teachers and the quantity and quality of the coaching they received. Additionally, candidates in the more promising placements were more likely to report better working conditions, stronger collaboration among teachers, more opportunities to learn to teach, and feeling better prepared to teach ( Ronfeldt et al., 2018 ). In their study of six Washington State teacher education programs, Goldhaber, Krieg, and Theobald (2017) found that teachers are more effective when the student demographics of the schools where they did their student teaching and those of their current schools are similar. Scholarship also shows an association between the effectiveness of the mentor teacher and the future effectiveness of teacher candidates ( Goldhaber, Krieg, and Theobald, 2018 ), using value-added as a measure of effectiveness.

Research on preservice preparation in multiple fields, including teacher education, points to the difficulties that novices may encounter in integrating their academic preparation with their clinical or field experience ( Benner et al., 2010 ; Cooke, Irby, and O’Brien, 2010 ; Grossman et al., 2009b ; Sheppard et al., 2009 ; Sullivan, 2005 ). Those difficulties may be compounded when novices lack access to clinical experiences in settings that reflect high standards of professional practice and that prepare novice professionals to take a reflective and questioning stance toward their own practice. As Ball and Cohen (1999) caution, some clinical experiences do little to disrupt or address the “apprenticeship of observation” ( Lortie, 1975 ) that teachers bring with them to their field experiences and student teaching: that is, the thousands of hours in the classroom spent observing teaching as students. This apprenticeship of observation may reinforce the conservatism of teaching practice if teacher education, including clinical experience, does not offer opportunities for preservice teachers to seriously study their own experiences and practice, and engage in “substantial professional discourse” ( Ball and Cohen, 1999 , p. 5).

Concerns about the quality of clinical experience seem particularly warranted in situations where teacher candidates have little or no field experience, or where candidates are permitted or even required to find their own placement sites for early field experiences and/or student teaching ( Levine, 2006 ). In a study of mathematics and science teachers using the 2003–2004 Schools and Staffing Survey, and the supplement, the 2004–2005 Teacher Follow-up Survey, Ingersoll, Merrill, and May (2012, 2014 ) found that 21 percent of new teachers did not have any practice or student teaching before their first job, and the rates were even higher for science teachers: 40 per-

cent had no practice teaching. The latest data from the 2015–2016 National Teacher and Principal Survey indicate that this has not changed: 23 percent of first-year teachers in 2015 had no practice teaching ( Ingersoll, personal communication, 2019 ). This matters because the amount of practice teaching teachers candidates have is associated with whether they remain in the field as teachers ( Ingersoll, Merrill, and May, 2014 ). However, much is not known about how the student teaching experience contributes to teacher candidates’ development ( Anderson and Stillman, 2013 ). Much of the scholarship tends to focus on changing beliefs among teacher candidates rather than the development of teaching practice, and a more robust research base is needed to understand the role such development plays in teacher preparation ( Anderson and Stillman, 2013 ).

Innovations in Teacher Preparation

Efforts to strengthen the quality of clinical experience have taken center stage in recent years, spurred in part by high-profile reports such as the Blue Ribbon Panel report, Transforming Teacher Education through Clinical Practice: A National Strategy to Prepare Effective Teachers (NCATE, 2010; see also the report of the AACTE Clinical Practice Commission, 2018 ). In addition, some studies have demonstrated the potential of field experiences to support teacher learning when well designed and coordinated with campus coursework ( Darling-Hammond, 2006 ; Lampert et al., 2013 ; Tatto, 1996 ). Three recent innovations in the organization of clinical experience, discussed below, show promise for developing teacher candidates’ practice, particularly in working in urban and high-need contexts.

Clinical Experiences

In an approach modeled after medical rounds attended by physicians in training, Robert Bain and Elizabeth Moje at the University of Michigan developed a project to integrate student teachers’ discipline-specific preparation with their preparation to tackle problems of practice in the field ( Bain, 2012 ; Bain and Moje, 2012 ). The Clinical Rounds Project was launched in 2005 with a pilot in the area of social studies; it has since expanded to include methods instructors, field instructors, interns, and practicing classroom teachers across five content areas: social studies, mathematics, science, English language arts, and world languages. The project seeks to integrate the disparate components of the teacher education program through a spiraling program of study. Teacher candidates rotate through classrooms of carefully selected mentor teachers (called “attending teachers”) who model selected practices and intervene in the teaching of teacher candidates to offer real-time feedback. Based on video of preservice

teachers working in the field and on other project documentation, Bain (2012) reports several changes evident in the “Rounds” cohorts compared to previous cohorts: a new conception of the teacher’s role; a heightened appreciation for the kinds of curricular and instructional tools they would need to achieve their goals; a deeper understanding of the challenges their secondary students are likely to experience in the history classroom; and end-of-program perception that their coursework and field experiences had been fruitfully integrated.

Methods courses located at school sites (sometimes referred to as a hybrid space) can facilitate new connections between teacher candidates, practicing teachers, and university-based teacher educators in new ways that can address the historical divide that exists between campus and field-based teacher education and enhance teacher candidates’ learning. This hybrid space has the potential of creating a partnership among key stakeholders (K–12 students, teacher candidates, university faculty, and mentor teachers) characterized by more egalitarian and collegial relationships than conventional school-university partnerships ( Zeichner, 2010 ).

Different kinds of hybrid spaces exist. Some examples include having “studio days” focused on teaching English learners, with prospective teachers working jointly with experienced teachers to focus on language structures ( Von Esch and Kavanagh, 2018 ); incorporating K–12 teachers and their knowledge bases into campus courses and field experiences (e.g., by having teachers with high levels of competence spend a residency working in all aspects of a preservice teacher education program); incorporating representation of teachers’ practices in campus courses (through writing and research of K–12 teachers or multimedia representations of their teaching practice); and incorporating knowledge from communities into preservice teacher preparation ( Zeichner, 2010 ).

Many other clinical innovations exist and are in various phases of development. Empirical research is needed to explore the effectiveness of these innovations on a range of outcome measures (e.g., teacher candidates’ future effectiveness related to student achievement and in centering equity and justice in their teaching) as well as the feasibility and cost of implementing them. Some clinical approaches, such as microteaching, have been used for many years ( Grossman, 2005 ) and continue to be common components of field instruction, with adaptions to make use of current contexts ( Abendroth, Golzy, and O’Connor, 2011 ; Fernandez, 2010 ).

Technological Innovations

Teacher preparation programs are increasingly using technological innovations in a range of ways in attempts to better prepare teacher candidates ( Hollett, Brock, and Hinton, 2017 ; Kennedy and Newman Thomas,

2012 ; Rock et al., 2009 , 2014 ; Schaefer and Ottley, 2018 ; Scheeler et al., 2006 ; Sherin and Russ, 2014 ; Uerz, Volman, and Kral, 2018 ). eCoaching through bug-in-ear technology is a relatively new technology that allows for discreet coaching to be offered via an online coach or supervisor ( Hollett, Brock, and Hinton, 2017 ; Rock et al., 2009 , 2014 ; Schaefer and Ottley, 2018 ; Scheeler et al., 2006 ). Current research examines the way bug-in-ear technology can enhance teacher preparation programs ( Hollett, Brock, and Hinton, 2017 ; Schaefer and Ottley, 2018 ; Scheeler et al., 2006 ), especially the long-term benefits for special education teachers-in-training ( Rock et al., 2009 , 2014 ).

Video recordings of practice are used for reflection, peer collaboration (e.g., through a “video club”), evaluation, and coaching. In response to the increased use of video recordings, there has been a corresponding development in video sharing platforms (e.g., Edthena, Torsh Talent, Class Forward, Iris Connect). For example, in one recent study of preparation for mathematics teaching, Sun and van Es (2015) designed a video-based secondary-level mathematics methods course, Learning to Learn from Teaching (LLFT), in which teacher candidates studied video cases of teaching to learn to notice features of ambitious pedagogy, with particular attention to analysis of student thinking. Researchers compared videos of teaching practice between teacher candidates enrolled in the LLFT course and teacher candidates in the same program from a prior year who did not take the LLFT course. They analyzed the videos along the dimensions of (1) making student thinking visible, (2) probing student thinking, and (3) learning in the context of teaching. Sun and van Es found that the teacher candidates in the LLFT course enacted responsive teaching practices attending to student thinking with more frequency.

Technology-supported simulations provide preservice teacher candidates opportunities to hone classroom management and instructional skills with multiple opportunities for practice without experimenting on actual students. This standardized tool is often found in other professions such as medicine, business, and the military. There are forms of simulations that are not aided by technology, such as work being done at Syracuse University in which actors play the part of students in the simulations (similar to the work being done within medical schools) and experimental efforts at the University of Michigan with an assessment that utilizes a “standardized student.”

According to one teacher educator and researcher with extensive experience with this technology, an effective simulation needs to have three critical components: “(a) personalized learning, (b) suspension of disbelief, and (c) cyclical procedures to ensure impact” ( Dieker et al., 2014 , p. 22). For example, TLE TeachLivE, a mixed-reality teaching environment, provides a room for the teacher or teacher candidate to physically enter that

simulates an actual classroom, with “virtual students” as avatars (played by a live “actor” offsite) ( Dieker et al., 2014 ). Teachers interact with the virtual students (who represent a range of ages, cultures, backgrounds, and abilities), teach new content, and monitor students as they work independently. Following feedback or self-reflection, the teacher candidates may re-enter the virtual classroom to attempt different responses and strategies to support student learning ( Dieker et al., 2014 , p. 3).

PREPARING TEACHER CANDIDATES TO WORK WITH DIVERSE POPULATIONS

At their best, all of the approaches outlined above—developing a command of core practices in subject-specific teaching, participating in well-designed clinical experiences integrated with coursework, and capitalizing on new technologies—should aid in the preparation of teachers to work with a diverse student population. Some recent studies supply evidence that field experiences in local communities—beyond classrooms and schools, and where preservice teachers are carefully prepared and guided through mediation, debriefing of these experiences, and connecting these experiences to the rest of their program—may help teacher candidates develop a richer understanding of students whose backgrounds differ from their own ( McDonald et al., 2011 ). Yet the charge that teacher preparation programs fail to effectively prepare teacher candidates for the students they teach remains a common theme in the scholarship on teacher preparation (Anderson and Stillman, 2010; Cochran-Smith et al., 2016 ).

As illustrated in Chapter 3 , one response to the disconnect between teachers (who are predominantly White, middle class, and female) and their students has been to emphasize the tenets of culturally relevant pedagogy and culturally sustaining pedagogy that support multilingualism and multiculturalism. Although a full characterization of teacher education faculty was beyond the scope of this report, teacher education faculty including adjunct faculty (which as of 2007 were 78% White) may play a key role in “how urgently a program works to address race and ethnicity” ( Sleeter, 2017 , p. 158).

There is no shortage of approaches and programs designed to prepare teachers for increasing cultural diversity, conceptualized in terms of social class, ethnicity, culture, and language ( Major and Reid, 2017 ). However, there is no single “formula” ( Major and Reid, 2017 , p. 8) for implementing these approaches because, as Gay (2013) argues, the sociocultural context in which instructional practices are taught should influence the approaches used: “Culturally responsive teaching, in idea and action, emphasizes localism and contextual specificity” ( Gay, 2013 , p. 63). As Major and Reid (2017) observe, “Cultural and linguistic difference is inevitably overlaid

with larger historical and political issues of migration, indigeneity, invasion, economic power, citizenship and racism. All of these are realised differently in different contexts and require teachers to understand their own cultural positioning and power in relation to the varieties of cultural difference with which they are engaged” (p. 11).

To what extent do teacher preparation programs foreground approaches for teaching multilingual, multicultural students? Critics argue that most teacher programs fall short. In their review of the literature on culturally responsive schooling for indigenous youth, Castagno and Brayboy (2008) found that schools and classrooms were failing to meet the needs of Indigenous students; they also found that although much theory and scholarship has been devoted to culturally responsive schooling for Indigenous populations, the main tenets of such pedagogies are often essentialized or too generalized to be applicable and effective. Similarly, few teachers develop the required skills to effectively work with emergent bilinguals—skills such as gauging students’ language development and content understanding and using informal and formal assessments to promote literacy development ( López and Santibañez, 2018 ). Scholars who have examined these issues argue that the consequences of these failures are serious, with consequences for a range of indicators of student success, including achievement, classification as emergent bilinguals, and high school completion ( López and Santibañez, 2018 ).

In one effort to advance the integration of culturally relevant pedagogy preparation into programs of teacher education, Allen and colleagues (2017) developed a conceptual framework that “requires teacher educators and candidates to pose questions that disrupt, deconstruct, reimagine, and develop concepts in an effort to promote academic rigor and higher-order thinking” (p. 18). The authors urge questions that challenge the “status quo” curriculum, the nature of classroom and field learning opportunities, the content of the program, instructional practices, and avenues for voice.

Given the demographic divide between teacher candidates and the students they teach, preparing teacher candidates to address issues of diversity and focus on equity in meaningful, authentic, and practical ways is critical. Teacher preparation programs vary dramatically in their approaches. Box 5-6 highlights two approaches that show promise for developing teacher candidates’ will and capacity to value students’ diverse backgrounds and engage in culturally sustaining pedagogy ( Paris and Alim, 2017 ): (1) valuing students’ funds of knowledge from outside of school and (2) building relationships with the students’ communities.

This section highlights principles, commitments, and pedagogies that hold promise for preparing teachers to work for equity and social justice. Preparing teachers to work for equity and social justice is not the

same as preparing teachers to work with a diverse student population ( Cochran-Smith, 2004 ). Rather, it involves preparation that fosters a deep understanding of the structures and processes that reproduce inequality, cultivates a disposition to act in ways that interrupt those structures and processes, and equips teachers for equity-oriented leadership.

Educators have been calling for teacher preparation that reflects commitments to equity for decades ( Fraser, 2007 ). For example, a recent issue of Teachers College Record compiled articles devoted to the goal to “reclaim the power and possibility of university-based teacher education to engage in transformations that prioritize the preparation of asset-, equity-, and social justice-oriented teachers” ( Souto-Manning, 2019 , p. 2).

As discussed earlier, the philosophical approach of culturally sustaining pedagogy directly seeks to foster linguistic, literate, and cultural

pluralism with the aim of positive social transformation for education. Culturally sustaining pedagogy is an assets-based approach that addresses the colonial aspect of contemporary schooling and actively works to disrupt anti-Blackness, anti-Indigeneity, anti-Brownness, model minority myths, and other ways in which schools foster colonialism and seeks to provide an alternative to the dominant “White gaze” ( Paris and Alim, 2017 , pp. 2–3).

Contemporary teacher education scholarship continues to argue that programs are not adequately preparing teachers to enact teaching in ways that are informed by equity-oriented interpretive frames ( Carter Andrews et al., 2019 ; Sleeter, 2017 ). Such programs may employ interpretive frameworks in coursework and field experience and engage in activity that deepens teacher candidates’ understanding, skills, and commitments (e.g., asset

mapping, placement in community-based organizations). Unfortunately, many scholars claim that most programs tend to fall short of equipping teacher candidates with a deep understanding of structural inequalities and tools needed to create more equitable opportunities (e.g., Carter Andrews et al., 2019 ; Cochran-Smith et al., 2014; Sleeter, 2017 ). Understanding how to prepare teacher candidates for this kind of work is an area for both research and innovation.

MECHANISMS FOR INFLUENCING PRESERVICE TEACHER EDUCATION

If preservice teacher education is to be a more uniformly coherent and demonstrably effective contributor to the quality of teachers and teaching in the 21st century, it will require change at multiples levels and in multiple respects. Thinking about levers for change proves challenging. Nonetheless, four (admittedly overlapping) categories of influence occupy a prominent place in the available research literature and in educational journalism.

First, teacher education has been increasingly shaped by regulatory and policy mechanisms including professional standards, program admission criteria, state licensure requirements, and program accreditation. Over the past two decades, policy makers supported new and flexible pathways into teaching while simultaneously moving to tighten accountability for program outcomes ( Cochran-Smith et al., 2018a ). States and other accrediting bodies have specified criteria for admission that emphasize both the academic qualifications of individuals and the formation of a diverse pool of teacher candidates. Standards of professional teaching practice encompass the expectations outlined in Chapter 3 , although the field lacks the kind of empirical evidence to know with certainty how standards translate into preparation and practice outcomes. Nonetheless, changes in licensure requirements and program accreditation mark a shift from program inputs and components to teacher candidate outcomes, with some states requiring candidate performance assessment for licensure and/or program accreditation ( AACTE, n.d. ).

A second potential source of influence on teacher education are the multiple institutional or professional associations and networks that populate the teacher education terrain, as well as various policy-related organizations that include teacher education policies on a broader agenda of educational reform. Professional associations of teachers and teacher educators have served as mechanisms for developing and promoting research-based conceptions of learning that in turn have influenced programs of teacher preparation and professional development; a well-known example

is the conception of mathematics learning advanced by the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics in the late 1980s ( NRC, 2001 ). Professional associations with institutional (rather than individual) membership are more likely to promote broad programmatic priorities, as NCATE did by appealing to program to place field experience as the center of teacher preparation, and AACTE did in 2018 when it followed up with a set of proclamations regarding clinical practice ( Little, 1993 ). 5

A third source of influence takes the form of targeted change initiatives. Some initiatives have emerged from within the field of teacher education, led by teacher educators and teacher education researchers. Among the examples that span several decades are the Holmes Group and the more recent CPC. Other initiatives flow from initiatives or funding streams supported by the federal government (such as support for Teach For America and for alternatives to university-based teacher preparation). Still others stem from private corporations, venture capitalists, or foundations that have altered the landscape of teacher education through their investments in new institutional entities (such as new Graduate Schools of Education) and their ties to federal policy makers. Some private-sector initiatives recruit institutions that agree to pursue a particular reform agenda; Teachers for a New Era, launched by the Carnegie Corporation of New York, presents one well-funded example (see Box 5-7 ).

Finally, the committee acknowledges the potential of ideas, messaging, and exemplars to stimulate new organizational arrangements and practices. The rapid spread of terms such as “deeper learning” and “core practices” points to the potential for influence though the technology-aided and network-supported spread of new ideas and associated exemplars. Powerful ideas may be developed and spread by any number of entities, including public agencies, universities, reform organizations, private foundations, networks, and individuals—and by numerous means including social media, conferences, publications, as well as privately and publicly funded initiatives. Of course, the rapid spread of organizing ideas and images does not signal common definitions of what those terms mean (in fact, rapid spread may impede such common definition, complicating the conduct of related research), nor does it entail uniform endorsement of any given idea or approach ( Aydarova and Berliner, 2018 ; Zeichner, 2014 ).

5 More information regarding NCATE’s appeal to place field experiences at the center of teacher preparation can be found at http://www.highered.nysed.gov/pdf/NCATECR.pdf . More on AACTE’s proclamations can be found at https://secure.aacte.org/apps/rl/res_get.php?fid=3750&ref=rl .

The past 20 years has witnessed a proliferation in the pathways to teacher preparation and a range of innovations in teacher preparation programs including in the field and in technology. Preservice teacher education content, goals, and approaches have changed due in part to the accountability movement, increased attention to deeper learning, the changing nature of standards for what teachers should know and be able to do, and increased attention to equity. Qualitative studies of programs suggest that factors leading to stronger candidates include program coherence, instructors’ modeling of powerful practices in methods courses, a strong connection between theory and practice, and intentional design of the field experience. However, the committee did not find evidence to support policies that would address questions about systems-level issues in preservice teacher preparation due to the high degree of variation in institutional type and mission, as well as decentralization of control that is built into the historical development of colleges and universities ( Labaree, 2017 ).

In general, there is a lack of systematic research or evidence beyond anecdotes and case studies about teacher preparation programs’ content and effectiveness, and whether these programs have changed over time. Despite a call nearly ten years ago ( NRC, 2010 ) for an independent evaluation of teacher education approval and accreditation, no such evaluation has been initiated.

Abendroth, M., Golzy, J.B., and O’Connor, E.A. (2011). Self-created YouTube recordings of microteachings: Their effects upon candidates’ readiness for teaching and instructors’ assessment. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 40 (2), 141–159.

Adler, S. (2008). The education of social studies teachers. In L.S. Levstik and C.A. Tyson (Eds.), Handbook of Research in Social Studies Education (pp. 329–351). New York: Routledge.

Allen, A., Hancock, S.D., W. Lewis, C., and Starker-Glass, T. (2017). Mapping culturally relevant pedagogy into teacher education programs: A critical framework. Teachers College Record, 119 (1), 1–26.

American Association of Colleges for Teacher Educators (AACTE) (n.d.). Participation Map . Available: http://edtpa.aacte.org/state-policy .

American Association of Colleges for Teacher Educators Clinical Practice Commission. (2018). A Pivot Toward Clinical Practice, Its Lexicon, and the Renewal of Educator Preparation . Available: https://aacte.org/programs-and-services/clinical-practice-commission .

Anderson, L.M., and Stillman, J.A. (2013). Student teaching’s contribution to preservice teacher development: A review of research focused on the preparation of teachers for urban and high-needs contexts. Review of Educational Research , 83 (1), 3–69.

Anderson, M. (2017). A Look at Historically Black Colleges and Universities as Howard Turns 150 . Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Available: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/02/28/a-look-at-historically-black-colleges-and-universities-as-howard-turns-150 .

Aydarova, E., and Berliner D.C. (2018). Responding to policy challenges with research evidence: Introduction to special issue. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 26 (32).

Bain, R.B. (2012). Using disciplinary literacy to develop coherence in history teacher education: The Clinical Rounds Project. The History Teacher, 45 (4), 513–532.

Bain, R.B., and Moje, E.B. (2012). Mapping the teacher education terrain for novices. Kappan, 93 (5), 62–66.

Ball, D. (2000). Bridging practices: Intertwining content and pedagogy in teaching and learning to teach. Journal of Teacher Education, 51 (3), 241–247.

Ball, D.L., and Cohen, D.K. (1999). Developing practice, developing practitioners: Toward a practice-based theory of professional education. In L. Darling-Hammond and G. Sykes (Eds.), Teaching as the Learning Profession: Handbook of Policy and Practice (pp. 3–32). San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Ball, D.L., and Forzani, F.M. (2009). The work of teaching and the challenge for teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 60 (5), 497–511.

Ball, D.L., Thames, M.H., and Phelps, G. (2008). Content knowledge for teaching: What makes it special? Journal of Teacher Education, 59 , 389–407.

Ball, D.L., Sleep, L., Boerst, T.A., and Bass, H. (2009). Combining the development of practice and the practice of development in teacher education. Elementary School Journal, 109 (5), 458–474.

Banilower, E.R., Smith, P.S., Malzahn, K.A., Plumley, C.L., Gordon, E.M., and Hayes, M.L. (2018). Report of the 2018 NSSME+ . Chapel Hill, NC: Horizon Research, Inc.

Bartlett, L. (2014). Migrant Teachers: How American Schools Import Labor . Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Benner, P.E., Sutphen, M., Leonard, V., and Day, L. (2010). Educating Nurses: A Call for Radical Transformation . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Bhabha, H. (1990). The third space: Interview with Homi Bhabha. In J. Rutherford (Ed.), Identity, Community, Culture, Difference (pp. 207–221). London: Lawrence & Wishart.

Boerst, T., Sleep, L., Ball, D., and Bass, H. (2011). Preparing teachers to lead mathematics discussions. Teachers College Record, 113 (12), 2844–2877.

Book, C., Byers, J. and Freeman, D. (1983). Student expectations and teacher education traditions with which we can and cannot live. Journal of Teacher Education, 34 (1), 9–13.

Boser, U. (2011). Teacher Diversity Matters: A State-by-State Analysis of Teachers of Color. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress. Available: https://cdn.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/issues/2011/11/pdf/teacher_diversity.pdf .

Boser, U. (2014). Teacher Diversity Revisited: A New State-by-State Analysis. Center for American Progress. Available: https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/race/reports/2014/05/04/88962/teacher-diversity-revisited/ .

Boyd, D.J., Grossman, P.L., Lankford, H., Loeb, S., and Wyckoff, J. (2009). Teacher preparation and student achievement. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 31 (4), 416–440.

Boyd, D., Grossman, P., Lankford, H., Loeb, S., Wyckoff, J., McDonald, M., and Hammerness, K. (2012). Stanford Center for Education Policy Analysis . Available: https://cepa.stanford.edu/tpr/teacher-pathway-project-overview .

Carnegie Forum on Education and the Economy. (1986). A Nation Prepared: Teachers for the 21st Century: The Report of the Task Force on Teaching as a Profession . Hyattsville, MD: Author.

Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. (2019). Our Ideas. Using Improvement Science to Accelerate Learning and Address Problems of Practice . Available: https://www.carnegiefoundation.org/our-ideas .

Carter Andrews, D.J., Brown, T., Castillo, B.M., Jackson, D., and Vellanki, V. (2019). Beyond damage-centered teacher education: Humanizing pedagogy for teacher educators and preservice teachers. Teachers College Record, 121 (6).

Carver-Thomas, D. (2018). Diversifying the Teaching Profession: How to Recruit and Retain Teachers of Color. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.

Carver-Thomas, D., and Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). Teacher Turnover: Why It Matters and What We Can Do About It . Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.

Castagno, A.E., and Brayboy, B.M.J. (2008). Culturally responsive schooling for indigenous youth: A review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 78 (4), 941–993.

Clotfelder, C., Ladd, H., and Vigdor, J. (2005). Who teaches whom? Race and the distribution of novice teachers. Economics of Education Review, 24 (4), 377–392.

Cochran-Smith, M. (2004). Walking the Road: Race, Diversity, and Social Justice in Teacher Education . New York: Teachers College Press.

Cochran-Smith, M. (2019). Studying Teacher Preparation at New Graduate Schools of Education (nGSEs): Missions, Goals, and Logics. Paper presentation at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association. Toronto, Canada.

Cochran-Smith, M., Carney, M.C., Keefe, E.S., Burton, S., Chang, W., Fernandez, M.B., Miller, A.F., Sanchez, J.G., and Baker, M. (2018). Reclaiming Accountability in Teacher Education. New York: Teachers College Press.

Cochran-Smith, M., Keefe, E.S., Chang, W.C., and Carney, M.C. (2018). NEPC Review: 2018 State Teacher Policy Best Practices Guide . Boulder, CO: National Education Policy Center. Available: http://nepc.colorado.edu/thinktank/review-teacher-quality .

Cochran-Smith, M., Piazza, P., and Power, C. (2013). The politics of accountability: Assessing teacher education in the United States. The Educational Forum, 77 (1), 6–27.

Cochran-Smith, M., Ell, F., Grudnoff, L., Haigh, M., Hill, M., and Ludlow, L. (2016). Initial teacher education: What does it take to put equity at the center? Teaching and Teacher Education, 57 , 67–78.

Cochran-Smith, M., Villegas, A.M., Abrams, L.W., Chavez-Moreno, L.C., Mills, T., and Stern, R. (2016). Research on teacher preparation: Charting the landscape of a sprawling field. In D.H. Gitomer and C.A. Bell (Eds.), AERA Handbook of Research on Teaching, 5th Edition (pp. 439–547). Washington, DC: AERA.

Conrad, C., and Gasman, M. (2015). Educating a Diverse Nation: Lessons from Minority-Serving Institutions . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Cooke, M., Irby, D.M., and O’Brien, B.C. (2010). Educating Physicians: A Call for Reform of Medical School and Residency . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Core Practice Consortium. (2016). The Problem We Are Trying to Solve . Available: http://corepracticeconsortium.com/ .

Council of Chief State School Officers. (2017). Transforming Educator Preparation: Lessons Learned from Leading States . Washington, DC: Author.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2006). Powerful Teacher Education: Lessons from Exemplary Programs . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Darling-Hammond, L. and Oakes, J. (2019). Preparing Teachers for Deeper Learning. Cambridge: Harvard Education Press.

Darling-Hammond, L., Chung, R., and Frelow, F. (2002). Variation in teacher preparation: How well do different pathways prepare teachers to teach? Journal of Teacher Education, 53 (4), 286–302.

Dee, T.S., and Jacob, B.A. (2010). The Impact of No Child Left Behind on Students, Teachers, and Schools. Brookings Paper. Available: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/2010b_bpea_dee.pdf .

Dee, T.S., Jacob, B., and Schwartz, N.L. (2013). The effects of NCLB on school resources and practices. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 35 (2), 252–279.

Dieker, L.A., Rodriguez, J., Lingnugaris-Kraft, B., Hynes, M., and Hughes, C.E. (2014). The future of simulated environments in teacher education: Current potential and future possibilities. Teacher Education and Special Education, 37 (1), 21–33.

Dilworth, M.E. (Ed.). (2018). Millennial Teachers of Color . Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Dilworth, M.E., and Coleman, M.J. (2014). Time for a Change: Diversity in Teaching Revisited . Washington, DC: National Education Association. Available: https://www.nea.org/assets/docs/Time_for_a_Change_Diversity_in_Teaching_Revisited_(web).pdf .

Dutro, E., and Cartun, A. (2016). Cut to the core practices: Toward visceral disruptions of binaries in PRACTICE-based teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 58 , 119–128.

Espinoza, D., Saunders, R., Kini, T., and Darling-Hammond, L. (2018). Taking the Long View: State Efforts to Solve Teacher Shortages by Strengthening the Profession . Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.

Evans, C.M. (2017). Predictive validity and impact of CAEP standard 3.2: Results from one master’s-level teacher preparation program. Journal of Teacher Education , 68 (4), 363.

Fernandez, M.L. (2010). Investigating how and what prospective teachers learn through microteaching lesson study. Teaching & Teacher Education, 26 (2), 351–362.

Feuer, M.J., Floden, R.E., Chudowsky, N., and Ahn, J. (2013). Evaluation of Teacher Preparation Programs: Purposes, Methods, and Policy Options . Washington, DC: National Academy of Education.

Fogo, B. (2014). Core practices for teaching history: The results of a Delphi Panel Survey. Theory and Research in Social Education, 42( 2), 151–196.

Franke, M.L., Kazemi, E., and Battey, D. (2007). Mathematics teaching and classroom practice. In F.K. Lester (Ed.), Second Handbook of Research on Mathematics Teaching and Learning (pp. 225–256). Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishers.

Fraser, J.W. (2007). Preparing America’s Teachers: A History . New York: Teachers College Press.

Fraser, J.W., and Lefty, L. (2018). Teaching Teachers: Changing Paths and Enduring Debates . Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Fraser, J.W., and Watson, A.M. (2014). Why Clinical Experience and Mentoring Are Replacing Student Teaching on the Best Campuses . Princeton, NJ: The Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation. Available: http://woodrow.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/WoodrowWilson_FraserWatson_StudentTeaching_Nov20141.pdf .

Freeman, H.R. (2018). Millennial teachers of color and their question for community. In M.E. Dilworth, (Ed.), Millennial Teachers of Color (pp. 63–72). Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Fullan, M., Galluzzo, G., Morris, P., and Watson, N. (1998). The Rise and Stall of Teacher Education Reform . Washington, DC: American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education.

Gasman, M., Baez, B., Sotello, C., and Turner, V. (2008). Understanding Minority-Serving Institutions . Albany, NY: SUNY Press.