Private Equity Case Study: Example, Prompts, & Presentation

Private equity case studies are an important part of the private equity recruiting process because they allow firms to evaluate a candidate’s analytical, investing, and presentation abilities.

In this article, we’ll look at the various types of private equity case studies and offer advice on how to prepare for them.

This guide will help you ace your next private equity case study, whether you’re a seasoned analyst or new to the field.

Types Of Private Equity Case Studies

Case studies are very common in private equity interviews, and they are a key part of the overall recruiting process.

While you’re extremely likely to encounter a case study of some kind during your recruiting process, there is considerable variety in the types of case studies you might face.

Below I cover the major types:

Take-home assignment

In-person lbo modeling assignment.

For this case study, you’ll get some company information (e.g. a 10-K or a CIM) and be asked to assess whether or not you’re likely to invest.

Generally, you’ll get between 2-7 days to prepare a full presentation or investment memo with your recommendations that you’ll present to the interviewer. To support your investment recommendation, you’ll be expected to complete a full LBO model . The prompt may give certain details or assumptions to include in the model.

This type of test is most common during “off-cycle” hiring throughout the year, since firms have more time to allow you to complete the assignment.

This is pretty similar to the take-home assignment. You’re given company materials, will build a financial model, and decide whether you would invest.

The difference here is the time you’re given to complete the case. You’ll generally get between two to three hours, and you’ll typically complete the case study in the firm’s office, though some firms are becoming newly open to completing the assignment remotely.

In this case, you’ll typically only complete an LBO model. There is usually no presentation or investment memo. Rather, you’ll do the model and then have a short discussion afterward.

This is a shorter, more condensed version of an LBO model. You can complete a paper LBO with a piece of paper and a pen. Alternatively, you may be asked to discuss it verbally with the interviewer.

Rather than using an Excel spreadsheet, you use an actual sheet of paper to show your calculations. You don’t go into all the detail but focus on the essence of the model instead.

In this article, we’ll be focusing on the first two types of case studies because they are the most widely used. But if you’re interested, here is a deep dive on Paper LBOs .

Private Equity Case Study Prompt

Regardless of the type of case study you’re asked to do, the prompt from the interviewer will ultimately ask you to answer: “would you invest in this company?”

To answer this question you’ll need to take on the provided materials about the company and complete a leveraged buyout model to determine whether there is a high enough return. Generally, this is 20% or higher.

Usually, prompts also provide you with certain assumptions that you can use to build your LBO model. For example:

- Pro forma capital structure

- Financial assumptions

- Acquisition and exit multiples

Some private equity firms provide you with the Excel template needed for an LBO model, while others prefer you to make one from scratch. So be ready to do that.

Private Equity Case Study Presentation

As you’ve seen above, if you get a take-home assignment as a case study, there’s a good chance you’re going to have to present your investment memo in the interview.

There will usually be one or two people from the firm present for your presentation.

Each PE firm has a different interview process, some may expect you to present first and then ask questions, or the other way around. Either way, be prepared for questions. The questions are where you can stand out!

While private equity recruitment is there to assess your skills, it’s not all about your findings or what your model says. The interviewers are also looking at your communication skills and whether you have strong attention to detail.

Remember, in the private equity interview process, no detail is too small. So, the more you provide, the better.

How To Do A Private Equity Case Study

Let’s look at the step-by-step process of completing a case study for the private equity recruitment process:

- Step 1: Read and digest the material you’ve been given. Read through the materials extensively and get an understanding of the company.

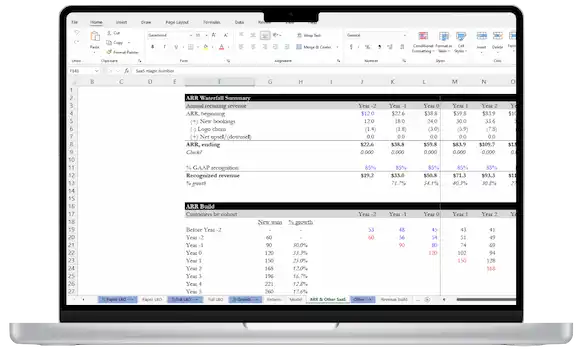

- Step 2: Build a basic LBO model. I recommend using the ASBICIR method (Assumptions, Sources & Uses, Balance Sheet, Income Statement, Cash Flow Statement, Interest Expense, and Returns). You can follow these steps to build any model.

- Step 3: Build advanced LBO model features, if the prompts call for it, you can jump to any advanced features. Of course, you want to get through the entire model, but your number 1 priority is to finish the core financial model. If you’re running out of time, I would skip or reduce time on advanced features.

- Step 4: Take a step back and form your “investment view”. I would try to answer these questions:

- What assumptions need to be present for this to be a good deal?

- Under what circumstances would you do the deal?

- What is the biggest risk in the deal? (e.g. valuation, growth, and margins).

- What is the biggest driver of returns in the deal? (e.g. valuation, growth, and debt paydown).

- 12+ video hours

- Excels & templates

PREMIUM COURSE

Become a Private Equity Investor

How To Succeed In A Private Equity Case Study

Here are a few of my tips for getting through the private equity fund case study successfully.

Get the basics down first

It’s very easy to want to jump into the more complex things first. If you go in and they start asking you to complete complex LBO modeling features like PIK preferred equity, getting to that might be on the top of your list.

But I recommend taking a step back and starting with the fundamentals. Get that out the way before moving on to the complicated stuff.

The fundamentals ground you, getting you through the things you know you can do easily. It also gives you time to really think about those complex ideas.

Show nuanced investment judgment; don’t be too black-and-white

When giving your investment recommendation for a private equity fund you shouldn’t be giving a simple yes or no.

It’s boring and gives you no space to elaborate. Instead, go in with what price would make you interested in investing and why. Don’t be shy to dig in here.

Know where there is a value-creation opportunity in the deal, and mention the key assumptions you need to believe to create that value.

Additionally, if you are recommending that the investment move forward then bring up things you would want to know before closing a deal. You can highlight the key risks of the investment, or key things you’d want to ask management if you could meet with them.

At the end of the day, financial modeling is a commodity skill. Every investor can do it. What will really set you apart is how you think about the deals, and the nuance you bring to analyzing them.

You win by talking about the model

Along those lines, you don’t win by building the best model. Modeling is just a check-the-box thing in the interview process to show you can do it. The interviewers need to know you can do the basics with no glaring errors.

What matters is showing that you can discuss the investment intelligently. It’s about bringing a sensible recommendation to the table with the information to back it up.

How Do I Prepare For A Private Equity Case Study?

There is no one-size-fits-all when it comes to preparing for a private equity case study. Everyone is different.

However, the best thing you can do is PRACTICE, PRACTICE, and more PRACTICE!

I know of a recent client that successfully obtained an offer from multiple mega funds . She practiced until she was able to build 10 LBO models from scratch without any errors or help … yes, that’s 10 models!

Now, whether it takes 5 or 20 practice case studies doesn’t matter. The whole point is to get to a stage where you feel confident enough to do an LBO model quickly while under pressure.

There is no way around the pressure in a private equity interview. The heat will be on. So, you need to prepare yourself for that. You need to feel confident in yourself and your capabilities.

You’d be surprised how pressure can leave you stumped for an answer to a question that you definitely know.

It’s also a good idea to think about the types of questions the private equity interviewer might ask you about your investment proposal. Prepare your answers as far as possible. It’s important that you stick to your guns too when the situation calls for it, because interviewers may push back on your answers to see how you react..

You need to have your answer to “would you invest in this company?” ready, and also how you got to that answer (and what new information might change your mind).

Another thing that gets a lot of people is limited time. If you’re running out of time, double down on the fundamentals or the core part of the model. Make sure you nail those. Also, you can make “reasonable” assumptions if there’s information you wish you had, but don’t have access to. Just make sure to flag it to your interviewer

How important is modeling in a private equity case study?

Modeling is part and parcel of private equity case studies. Your basics need to be correct and there should be no obvious mistakes. That’s why practicing is so important. You want to focus on the presentation, but your calculations need to be correct first. They do, after all, make up your final decision.

How can I stand out from other candidates?

Knowing your stuff covers the basics. To stand out, you need to be an expert in showing how you came to a decision, a stickler for details, and inquisitive. Anyone can do the calculations with practice, but someone who thinks clearly and brings nuance to their discussion of the investment will thrive in interviews.

Private equity case studies are a difficult but necessary part of the private equity recruiting process . Candidates can demonstrate their analytical abilities and impress potential employers by understanding the various types of case studies and how to approach them.

Success in private equity case studies necessitates both technical and soft skills, from analyzing financial statements to discussing the investment case with your interviewer.

Anyone can ace their next private equity case study and land their dream job in the private equity industry with the right preparation and mindset. If you’re looking to learn more about private equity, you can read my recommended Private Equity Books.

- Articles in Guide

- More Guides

DIVE DEEPER

The #1 online course for growth investing interviews.

- Step-by-step video lessons

- Self-paced with immediate access

- Case studies with Excel examples

- Taught by industry expert

Get My Best Tips on Growth Equity Recruiting

Just great content, no spam ever, unsubscribe at any time

Copyright © Growth Equity Interview Guide 2023

HQ in San Francisco, CA

Phone: +1 (415) 236-3974

Growth Equity Industry & Career Primer

Growth Equity Interview Prep

How To Get Into Private Equity

Private Equity Industry Primer

Growth Equity Case Studies

SaaS Metrics Deep Dive

Investment Banking Industry Primer

How To Get Into Investment Banking

How To Get Into Venture Capital

Books for Finance & Startup Careers

Growth Equity Jobs & Internships

Mike Hinckley

Growth stage expertise.

Coached and assisted hundreds of candidates recruiting for growth equity & VC

with Mike Hinckley

Premium online course

- Private equity recruiting plan

- LBO modeling & financial diligence

- Interview case studies

Register for Waitlist

FREE RESOURCES

Get My Best Growth Equity Interview Tips

No spam ever, unsubscribe anytime

Username or Email Address

Remember Me

How to prepare for the case study in a private equity interview

If you're interviewing for a job in a private equity firm , then you will almost certainly come across a case study. Be warned: recruiters say this is the hardest part of the private equity interview process and how you handle it will decide whether you land the job.

“The case study is the most decisive part of the interview process because it’s the closest you get to doing the job," says Gail McManus of Private Equity Recruitment. It's purpose is to make you answer one question: 'Would you invest in this company?'

In most cases, you'll be given a 'Confidential Information Memorandum' (CIM) relating to a company the private equity fund could invest in. You'll be expected to a) value the company, and b) put together an investment proposal - or not. Often, you'll be allowed to take the CIM away to prepare your proposal at home.

“The case study is still the most decisive element of the recruitment process because it’s the closest you get to actually doing the job. Candidates can win or lose based on how they perform on case study. People who are OK in the interview can land the job by showing the quality of their thinking, ” says McManus. “You need to show that you can think, and think like an investor.”

"The end decision [on whether to invest] is not important," says one private equity professional who's been through the process. "The important thing is to show your thinking/logic behind answer."

Preparing for a PE case study has distinctive challenges for consultants and bankers. If you're a consultant, you need to, "make a big effort to mix your strategic toolkit with financial analysis. You need to prove that you can go from a strategic conclusion to a finance conclusion," says one PE professional. Make sure you're totally familiar with the way an LBO model works.

If you're a banker, you need to, "make a big effort to develop your strategic thinking," says the same PE associate. The fund you're interviewing with will want to see that you can think like an investor, not just a financier. "Reaching financial conclusions is not enough. You need to argue why certain industry is good, and why you have a competitive advantage or not. Things can look good on paper, but things can change from a day to another. As a PE investor, hence as a case solver, you need to highlight and discuss risks, and whether you are ready or not to underwrite them."

Kadeem Houson, partner at KEA consultants, which specialises in hiring junior to mid-level PE professionals, says: “If you’re a banker you’re expected to have great technical skills so you need to demonstrate you can think commercially about the numbers you plugged in. Conversely, a consultant who is good at blue sky thinking might be pressed more on their understanding of the model. Neither is better or worse – just be conscious of your blank spots.”

A good business versus a good investment

For McManus, one of the most important things to consider when looking at the case study is to understand the difference between a good business and a good investment. The difference between a good business and a good investment is the price. So you might have a great business but if you have to pay hugely for it it might not be a great business. Conversely you can have a so-so business but if you get it a good price it might make a great investment. “

McManus says as well as understanding the difference between a good business and a good investment, it’s important to focus on where the added value lies. This has become a critical element for private equity firms to consider as competition for assets has become even more fierce, given the amount of dry powder that funds now have at their disposal through a wide array of funds. “Because of the competition for transactions generally you have to overpay to win a deal. So in the case study it’s really important you think about where the value creation opportunity lies in this business and what the exit would be,” says McManus.

She advises candidates to be brave and state a specific price, provided you can demonstrate how you’ve arrived at your answer.

Another private equity professional says you shouldn't go out on a limb, though, and you should appear cautious: "Keep all assumptions conservative at all times so as not to raise difficult questions. Always highlight risks, downsides as well as upsides."

Research the fund – find the angle

One private equity professional says that understanding why an investment might suit a particular firm could prove to be a plus. Prior to the case study, check whether the fund favours a particular industry sector, so that when it comes to the case study, you can add that to the investment thesis. “This enables you to showcase you have read up on the firm’s strategy/unique characteristics Something that would make it more likely for the fund you’re interviewing with winning the deal in what’s a very competitive market, said the PE source, who said this knowledge made him stand out.

However, the primary purpose of the case study is to test the quality of your thinking - it is not to test you on your knowledge of the fund. “Knowing about the fund will tick an extra box, but the case study is about focusing on the three most critical things that will drive the investment decision,” says McManus.

You need to think through these questions and issues:

We spoke to another private equity professional who's helpfully prepared a checklist of points to think about when you're faced with the case study. "It's a cheat sheet for some of my friends," he says.

When you're faced with a case study, he says you need to think in terms of: the industry, the company, the revenues, the costs, the competition, growth prospects, due dliligence, and the transaction itself.

The questions from his checklist are below. There's some overlap, but they're about as thorough as you can get.

When you're considering the industry, you need to think about:

- What the company does. What are its key products and markets? What's the main source of demand for its products?

- What are the key drivers in that industry?

- Who are the market participants? How intense is the competition?

- Is the industry cyclical? Where are we in the cycle?

- Which outside factors might influence the industry (eg. government, climate, terrorism)?

When you're considering the company, you need to think about:

- Its position in the industry

- Its growth profile

- Its operational leverage (cost structure)

- Its margins (are they sustainable/improvable)?

- Its fixed costs from capex and R&D

- Its working capital requirements

- Its management

- The minimum amount of cash needed to run the business

When you're considering the revenues, you need to think about:

- What's driving them

- Where the growth is coming from

- How diverse the revenues are

- How stable the revenues are (are they cyclical?)

- How much of the revenues are coming from associates and joint ventures

- What's the working capital requirement? - How long before revenues are booked and received?

When you're considering the costs, you need to think about:

- The diversity of suppliers

- The operational gearing (What's the fixed cost vs. the variable cost?)

- The exposure to commodity prices

- The capex/R&D requirements

- The pension funding

- The labour force (is it unionized?)

- The ability of the company to pass on price increases to customers

- The selling, general and administrative expenses (SG&A). - Can they be reduced?

When you're considering the competition, you need to think about:

- Industry concentration

- Buyer power

- Supplier power

- Brand power

- Economies of scale/network economies/minimum efficient scale

- Substitutes

- Input access

When you're considering the growth prospects, you need to think about:

- Scalability

- Change of asset usage (Leasehold vs. freehold, could manufacturing take place in China?)

- Disposals

- How to achieve efficiencies

- Limitations of current management

When you're considering the due diligence, you need to think about:

- Change of control clauses

- Environmental and legal liabilities

- The power of pension schemes and unions

- The effectiveness of IT and operations systems

When you're considering the transaction, you need to think about:

- Your LBO model

- The basis for your valuation (have you used a Sum of The Parts (SOTP) valuation or another method - why?)

- The company's ability to raise debt

- The exit opportunities from the investment

- The synergies with other companies in the PE fund's portfolio

- The best timing for the transaction

BUT: keep things simple.

While this checklist is important as an input and a way to approach the task, w hen it comes to presenting the information, quality beats quantity. McManus says: “The main reason why people aren’t successful in case studies is that they say too much. What you’ve got to focus on is what’s critical, what makes a difference. It’s not about quantity, it’s about quality of thinking. If you do 30 strengths and weaknesses it might only be three that matter. It’s not the analysis that matters, but what’s important from that analysis. What’s critical to the investment thesis. Most firms tend to use the same case study so they can start to see what a good answer looks like.”

Houson agrees that picking out the most important elements in the case study are more important than spending too much time on an elaborate model. “You don’t necessarily need to demonstrate such technical prowess when it comes to building the model. But you need to be comfortable about being challenged around the business case. Frankly it’s better to go for a simple answer which sparks a really interesting conversation rather than something that is purely judged from a technical standpoint. The model is meant to inform the discussion, not be the discussion itself.”

Softer factors such as interpersonal skills are also important because if the case study is the closest thing you’ll get to doing the job, then it’s also a measure of how you might behave in a live situation. McManus says: “This is what it will be like having a conversation at 11am with your boss having been given the information memorandum the day before. Not only are the interviewers looking at how you approach the case study, but they’re also looking at whether they want to have this conversation with you every Tuesday morning at 11am.”

The exercise usually takes around four hours if you include the modelling aspect, so there is time pressure. “Top tips are to practice how to think in a way that is simple, but fit for purpose. Think about how to work quickly. The ability to work under pressure is still important,” says Houson.

But some firms will allow you do complete the CIM over the weekend. In that case on one private equity professional says you should get someone who already works in PE to check it over for you. He also advises getting friends who've been through case study interviews before to put you through some mock questions on your presentation.

But McManus says this can lead to spending too much time and favours the shorter method. “It’s fairer and you can illustrate the quality of your thinking over a short space of time.”

The case study is conducted online, and because of Covid, so too are many of the follow-up discussions, so it’s worth thinking about how to present yourself on zoom or Teams. “Although a lot of these case studies over the last couple of years have been done remotely, in many ways that’s even more reason to try to bring out a bit of engagement and personality with the people you’re talking to."

“ There’s never a right or wrong answer. Rather it’s showing your thinking and they like to have that discussion with you. It’s the nearest you get to doing the job. And that cuts both ways – if you don’t like the case study, you won't like doing the job. “

Contact: [email protected] in the first instance. Whatsapp/Signal/Telegram also available (Telegram: @SarahButcher)

Bear with us if you leave a comment at the bottom of this article: all our comments are moderated by human beings. Sometimes these humans might be asleep, or away from their desks, so it may take a while for your comment to appear. Eventually it will – unless it’s offensive or libelous (in which case it won’t.

Photo by Adam Kring on Unsplash

Sign up to Morning Coffee!

The essential daily roundup of news and analysis read by everyone from senior bankers and traders to new recruits.

Boost your career

Associate at US bank said to die after working 120 hour weeks

Edward Ruff, 40 year-old Citigroup MD accused of shouting at juniors, had a rough start

Reflections of a banking MD: "20 years of 70-90 hour weeks; six million air miles"

JPMorgan's new "young" investment bank head is inordinately popular

Morning Coffee: Cause of death of banking associate disclosed. Family offices hiring juniors on $300k

Goldman Sachs & Morgan Stanley juniors among recent hires at closing Hong Kong hedge fund

The 20-year-old finance interns earning $20k a month are quants and engineers

The banks with the best and worst working hours

Hedge fund Brevan Howard is parting with an ex-JPMorgan MD, but still hiring

Morning Coffee: HSBC sent rejected candidates an unfortunate email. Citi compliance officer says she was fired for whistleblowing

Related articles

How to move from banking to private equity, by a former associate at Goldman Sachs

Private equity pay: where the money has been made

The qualifications you need to work in banking, trading, and more

- Harvard Business School →

- Faculty & Research →

Private Equity: A Casebook

- Format: Print

- Find it at Harvard

About The Authors

Paul A. Gompers

Victoria Ivashina

Richard S. Ruback

More from the authors.

- Faculty Research

Forest Park Capital (B)

Forest park capital (a), biomanufacturing decentralization by stämm.

- Forest Park Capital (B) By: Richard S. Ruback and Royce Yudkoff

- Forest Park Capital (A) By: Richard S. Ruback and Royce Yudkoff

- Biomanufacturing Decentralization by Stämm By: Paul A. Gompers, Jenyfeer Martínez Buitrago and Mariana Cal

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Private equity

- Entrepreneurial financing

- Entrepreneurship

- Finance and investing

- Investment management

Corporate Governance Should Combine the Best of Private Equity and Family Firms

- Dominic Houlder

- Nandu Nandkishore

- December 22, 2016

Does Business Need a New Model?

- Roger L. Martin

- Lucian A. Bebchuk

- From the January–February 2021 Issue

The Role of Private Equity in Driving Up Health Care Prices

- Lovisa Gustafsson

- Shanoor Seervai

- David Blumenthal

- October 29, 2019

Lessons from Private Equity Any Company Can Use

- Orit Gadiesh & Hugh MacArthur

- March 07, 2008

Private Equity’s Lessons for the Rest of Us

- Paul Michelman

- July 23, 2007

Private Equity's Long View

- Walter Kiechel

- From the July–August 2007 Issue

The CEO of New Mountain Capital on Using PE Management to Ignite Growth

- Steve Klinsky

- From the May–June 2022 Issue

Establish a Productive Private Equity Partnership

- Katherine Alexander

- Richard Davis

- November 08, 2021

How to Attract the Right Shareholders

- Mark DesJardine

- August 08, 2023

Private Equity Should Take the Lead in Sustainability

- Robert G. Eccles

- Vinay Shandal

- David Young

- Benedicte Montgomery

- From the July–August 2022 Issue

How to Compete for Talent like a Private Equity Firm

- March 31, 2008

The Strategic Secret of Private Equity

- Felix Barber

- Michael Goold

- From the September 2007 Issue

Private Equity and the Ownership Decision

- Thomas H. Davenport

- June 29, 2009

Do Politics Shape Buyout Performance?

- Oliver F. Gottschalg

- Aviad A. Pe'er

- From the November 2008 Issue

If Private Equity Sized Up Your Business

- Robert C. Pozen

- From the November 2007 Issue

Private Equity's New Phase

- Dave Ulrich

- Justin Allen

- August 09, 2016

Why Private Equity Still Makes Us a Little Queasy

- January 17, 2012

To Make Deals in the Middle Market, Private Equity Needs Cultural Literacy

- Nancy Langer

- Sharon B. Heaton

- March 11, 2022

What You Can Learn from the Private Equity School of Management

- June 29, 2007

Turbocharging Asian Turnarounds

- Chul-Joon Park

- From the June 2006 Issue

Careem vs. the Ride-Hailing Goliath: Abraaj Journeys Further Into the Tech-enabled Consumer Space

- Claudia Zeisberger

- Bowen White

- December 15, 2017

Sam Barnstable and Blue Sky Radio Devices

- G. Felda Hardymon

- July 15, 2008

Sahrudaya Health Care Pvt. Ltd. (2017): Towards a Term Sheet

- Ramana Sonti

- Lalita Anand

- March 24, 2022

Project Deutschland: Unpeeling the Onion of a Distressed Real Estate Portfolio

- Nori Gerardo Lietz

- Ricardo Andrade

- March 31, 2016

Venture Capital and Private Equity: Module II

- Josh Lerner

- October 21, 1996

H. J. Heinz M&A

- David P. Stowell

- Nicholas Kawar

- December 03, 2014

Interline Brands: Don't Stop Believing

- March 02, 2017

The Abraaj Group and the Acibadem Healthcare Investment (A)

- Paul A. Gompers

- Bora Uluduz

- Firdevs Abacioglu

- September 03, 2013

Tribune Company, 2007

- Timothy A. Luehrman

- Eric Seth Gordon

- May 12, 2008

Zain Group: Diversity and Inclusion in the Middle East

- Lina Daouk-Oyry

- Charlotte Karam

- Axelle Meouchy

- November 11, 2021

Granite Equity Partners

- Victoria Ivashina

- Jeffrey Boyar

- September 24, 2018

Firmenich: Juggling the short and the long term (Cartoon case)

- Sameh Abadir

- October 27, 2022

Captain Fresh: Value Fishing across Segments

- Renuka Kamath

- ShabbirHusain RV

- June 06, 2023

Venture Capital and Private Equity: Module III

- October 17, 1996

Blue River Capital

- Krishna G. Palepu

- Tarun Khanna

- Richard J. Bullock

- October 04, 2007

Private Equity Real Estate Investors - Overcoming the challenge of Sustainability & ESG: Pro-invest Group's ESG Journey

- Alexandra von Stauffenberg

- Cindy Van Der Wal

- April 13, 2022

Sustainable Investing in Ambienta (A)

- Atalay Atasu

- Benjamin Kessler

- November 13, 2022

Spyder Active Sports, Inc. and CHB Capital Partners (A)

- John A. Davis

- Louis B. Barnes

- Peter Botticelli

- September 22, 1998

Dollar General Going Private

- Sharon Katz

- August 12, 2007

Transforming Tommy Hilfiger (B)

- Raffaella Sadun

- Hanoch Feit

- Vaibhav Gujral

- Gerard Zouein

- March 10, 2014

Careem vs. the Ride-Hailing Goliath: Abraaj Journeys Further Into the Tech-enabled Consumer Space, Teaching Note

Chevalier group: using a private equity "style" strategy to maximize a listed company's value, teaching note.

- Winnie Qian Peng

- Ambrose Tong

- May 23, 2016

IFMR Capital: Securitizing Microloans for Non-Bank Investors, Teaching Note

- M. Suresh Sundaresan

- September 23, 2013

Brazos Partners and the Tri-Northern Exit, Teaching Note

- Matthew Rhodes-Kropf

- Nathaniel Burbank

- March 05, 2014

Blue Haven Initiative: The PEGAfrica Investment, Video

- Vikram Gandhi

- October 22, 2020

Elephant Bar Restaurant: Mezzanine Financing, Student Spreadsheet

- Susan Chaplinsky

- Kristina Anderson

- September 20, 2008

Finance Reading: The Mergers and Acquisitions Process, Debrief Slides

- John Coates

- June 22, 2017

Popular Topics

Partner center.

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

What Is Private Equity?

Understanding private equity, private equity specialties, private equity deal types, how private equity creates value, why private equity draws criticism.

- Private Equity FAQs

The Bottom Line

- Government & Policy

Private Equity Explained With Examples and Ways to Invest

What you need to know about this alternative investment class

James Chen, CMT is an expert trader, investment adviser, and global market strategist.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/photo__james_chen-5bfc26144cedfd0026c00af8.jpeg)

Gordon Scott has been an active investor and technical analyst or 20+ years. He is a Chartered Market Technician (CMT).

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/gordonscottphoto-5bfc26c446e0fb00265b0ed4.jpg)

Private equity describes investment partnerships that buy and manage companies before selling them. Private equity firms operate these investment funds on behalf of institutional and accredited investors .

Private equity funds may acquire private companies or public ones in their entirety, or invest in such buyouts as part of a consortium . They typically do not hold stakes in companies that remain listed on a stock exchange .

Private equity is often grouped with venture capital and hedge funds as an alternative investment . Investors in this asset class are usually required to commit significant capital for years, which is why access to such investments is limited to institutions and individuals with high net worth .

Key Takeaways

- Private equity firms buy companies and overhaul them to earn a profit when the business is sold again.

- Capital for the acquisitions comes from outside investors in the private equity funds the firms establish and manage, usually supplemented by debt.

- The private equity industry has grown rapidly; it tends to be most popular when stock prices are high and interest rates low.

- An acquisition by private equity can make a company more competitive or saddle it with unsustainable debt, depending on the private equity firm's skills and objectives.

In contrast with venture capital , most private equity firms and funds invest in mature companies rather than startups . They manage their portfolio companies to increase their worth or to extract value before exiting the investment years later.

The private equity industry has grown rapidly amid increased allocations to alternative investments and following private equity funds' relatively strong returns since 2000. In 2022, private equity buyouts totaled $654 billion, the second-best performance in history. Private equity investing tends to grow more lucrative and popular during periods when stock markets are riding high and interest rates are low and less so when those cyclical factors turn less favorable.

Private equity firms raise client capital to launch private equity funds , and operate them as general partners, managing fund investments in exchange for fees and a share of profits above a preset minimum known as the hurdle rate .

Image by Sabrina Jiang © Investopedia 2020

Private equity funds have a finite term of 10 to 12 years, and the money invested in them isn't available for subsequent withdrawals. The funds do typically start to distribute profits to their investors after a number of years. The average holding period for a private equity portfolio company was about 5.6 years in 2023.

Several of the largest private equity firms are now publicly listed companies in the wake of the landmark initial public offering (IPO) by Blackstone Group Inc. ( BX ) in 2007. In addition to Blackstone, KKR & Co. Inc. ( KKR ), Carlyle Group Inc. ( CG ), and Apollo Global Management Inc. ( APO ) all have shares traded on U.S. exchanges. A number of smaller private equity firms have also gone public via IPOs, primarily in Europe.

Mira Norian / Investopedia

Some private equity firms and funds specialize in a particular category of private-equity deals. While venture capital is often listed as a subset of private equity, its distinct function and skillset set it apart, and have given rise to dedicated venture capital firms that dominate their sector. Other private equity specialties include:

- Distressed investing , specializing in struggling companies with critical financing needs

- Growth equity, funding expanding companies beyond their startup phase

- Sector specialists, with some private equity firms focusing solely on technology or energy deals, for example

- Secondary buyouts , involving the sale of a company owned by one private-equity firm to another such firm

- Carve-outs involving the purchase of corporate subsidiaries or units.

The deals private equity firms make to buy and sell their portfolio companies can be divided into categories according to their circumstances.

The buyout remains a staple of private equity deals, involving the acquisition of an entire company, whether public, closely held or privately owned. Private equity investors acquiring an underperforming public company will often seek to cut costs, and may restructure its operations.

Another type of private equity acquisition is the carve-out, in which private equity investors buy a division of a larger company, typically a non-core business put up for sale by its parent corporation. Examples include Carlyle's acquisition of Tyco Fire & Security Services Korea Co. Ltd. from Tyco International Ltd. in 2014, and Francisco Partners' deal to acquire corporate training platform Litmos from German software giant SAP SE ( SAP ), announced in August 2022. Carve-outs tend to fetch lower valuation multiples than other private equity acquisitions, but can be more complex and riskier.

In a secondary buyout, a private equity firm buys a company from another private equity group rather than a listed company. Such deals were assumed to constitute a distress sale but have become more common amid increased specialization by private equity firms. For instance, one firm might buy a company to cut costs before selling it to another PE partnership seeking a platform for acquiring complementary businesses.

Other exit strategies for a private-equity investment include the sale of a portfolio company to one of its competitors as well as its IPO.

By the time a private equity firm acquires a company, it will already have a plan in place to increase the investment's worth. That could include dramatic cost cuts or a restructuring, steps the company's incumbent management may have been reluctant to take. Private equity owners with a limited time to add value before exiting an investment have more of an incentive to make major changes.

The private equity firm may also have special expertise the company's prior management lacked. It may help the company develop an e-commerce strategy, adopt new technology, or enter additional markets. A private-equity firm acquiring a company may bring in its own management team to pursue such initiatives or retain prior managers to execute an agreed-upon plan.

The acquired company can make operational and financial changes without the pressure of having to meet analysts' earnings estimates or to please its public shareholders every quarter. Ownership by private equity may allow management to take a longer-term view, unless that conflicts with the new owners' goal of making the biggest possible return on investment .

Making Money the Old-Fashioned Way With Debt

Industry surveys suggest operational improvements have become private equity managers' main focus and source of added value.

But debt remains an important contributor to private equity returns, even as the increase in fundraising has made leverage less essential. Debt used to finance an acquisition reduces the size of the equity commitment and increases the potential return on that investment accordingly, albeit with increased risk .

Private equity managers can also cause the acquired company to take on more debt to accelerate their returns through a dividend recapitalization , which funds a dividend distribution to the private equity owners with borrowed money.

Dividend recaps are controversial because they allow a private equity firm to extract value quickly while saddling the portfolio company with extra debt . On the other hand, the increased debt presumably lowers the company's valuation when it is sold again, while lenders must agree with the owners that the company will be able to manage the resulting debt load .

Private equity firms have pushed back against the stereotype depicting them as strip miners of corporate assets, stressing their management expertise and examples of successful transformations of portfolio companies.

Many are touting their commitment to environmental, social, and governance (ESG) standards directing companies to mind the interests of stakeholders other than their owners.

Still, rapid changes that often follow a private equity buyout can often be difficult for a company's employees and the communities where it has operations.

Another frequent focus of controversy is the carried interest provision allowing private equity managers to be taxed at the lower capital gains tax rate on the bulk of their compensation. Legislative attempts to tax that compensation as income have met with repeated defeat, notably when this change was dropped from the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 .

How Are Private Equity Funds Managed?

A private equity fund is managed by a general partner (GP) , typically the private equity firm that established the fund. The GP makes all of the fund's management decisions. It also contributes 1% to 3% of the fund's capital to ensure it has skin in the game . In return, the GP earns a management fee often set at 2% of fund assets, and may be entitled to 20% of fund profits above a preset minimum as incentive compensation, known in private equity jargon as carried interest. Limited partners are clients of the private equity firm that invest in its fund; they have limited liability .

What Is the History of Private Equity Investments?

In 1901, J.P. Morgan bought Carnegie Steel Corp. for $480 million and merged it with Federal Steel Company and National Tube to create U.S. Steel in one of the earliest corporate buyouts and one of the largest relative to the size of the market and the economy.

In 1919, Henry Ford used mostly borrowed money to buy out his partners, who had sued when he slashed dividends to build a new auto plant. In 1989, KKR engineered what is still the largest leveraged buyout in history after adjusting for inflation , buying RJR Nabisco for $25 billion.

Are Private Equity Firms Regulated?

While private equity funds are exempt from regulation by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) under the Investment Company Act of 1940 or the Securities Act of 1933 , their managers remain subject to the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 as well as the anti-fraud provisions of federal securities laws. In February 2022, the SEC proposed extensive new reporting and client disclosure requirements for private fund advisers including private equity fund managers. The new rules would require private fund advisers registered with the SEC to provide clients with quarterly statements detailing fund performance, fees, and expenses, and to obtain annual fund audits. All fund advisors would be barred from providing preferential terms for one client in an investment vehicle without disclosing this to the other investors in the same fund.

For a large enough company, no form of ownership is free of the conflicts of interests arising from the agency problem . Like managers of public companies, private equity firms can at times pursue self-interest at odds with those of other stakeholders, including limited partners. Still, most private equity deals create value for the funds' investors, and many of them improve the acquired company. In a market economy , the owners of the company are entitled to choose the capital structure that works best for them, subject to sensible regulation.

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. " "Accredited Investor" Net Worth Standard ."

CAIA Association. " Strategic Portfolio Construction with Private Equity ."

Bain & Company. " Private Equity Outlook in 2023: Anatomy of a Slowdown ."

Dealogic. " M&A Highlight: Full Year 2021 ."

Moonfare. " What We Learned About Private Equity in H1 2022 ."

S&P Dow Jones Indices. " S&P Listed Private Equity Index ." Chart View: 10Y; Compare: S&P 500.

Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. " Unlocking Private Equity ."

Congressional Research Service. " Taxation of Carried Interest ." Pages 2-3.

Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. " Unlocking Private Equity ." Select "Life Cycle of a Private Equity Fund."

Private Equity Info. " Holding Periods Reach Record Highs as Private Equity Recovers from COVID-19 ."

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. " Form S-1, The Blackstone Group L.P., As Filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on March 22, 2007 ."

S&P Global. " Private Equity Firms Go Public as Valuations Soar, Retail Investors Buy In ."

Carlyle. " The Carlyle Group Agrees to Acquire ADT Korea from Tyco for $1.93 Billion ."

Francisco Partners. " Francisco Partners to Acquire Litmos From SAP ."

PwC. " Driving Transformative Value Creation in Private Equity Carve Outs ."

Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance. " Private Equity Carve-Outs Ride Post-COVID Wave ."

PitchBook. " How Secondary Buyouts Became Ubiquitous: SBOs as an Exit and Deal Sourcing Strategy ."

PitchBook. " Specialization in Private Equity Buyout Funds and Niche Investment Strategies ."

10X. " Private Equity Buyout Strategies That Generate Superior Returns ."

McKinsey & Company. " Private Equity Exit Excellence: Getting the Story Right ."

Moonfare. " Five Real-World Examples of Private Equity Creating Value by Improving Companies ."

KPMG. " Delivering on the Promise of Value Creation ."

The New York Times. " Private Equity Firms Are Piling On Debt to Pay Dividends ."

Oaktree Capital Management, L.P. " Case Study: Elgin National Industries ."

Bain & Company. " Limited Partners and Private Equity Firms Embrace ESG ."

Davis, Steven J. and et al. " The Economic Effects of Private Equity Buyouts. " National Bureau of Economic Research , Working Paper 26371, July 2021, pp. 1-89.

The New York Times. " The Carried Interest Loophole Survives Another Political Battle ."

Fogelström, Erik and Gustafsso, Jonatan. " GP Stakes in Private Equity: An Empirical Analysis of Minority Stakes in Private Equity Firms ." MSc Thesis in Finance , Stockholm School of Economics, pp. 1.

Harvard Business School, Baker Library, Bloomberg Center. " The Founding of U.S. Steel and the Power of Public Opinion ."

Carnegie Corporation of New York. " Andrew Carnegie: Pioneer. Visionary. Innovator ."

The Henry Ford. " Henry Ford: Founder, Ford Motor Company ."

Financial Times. " Memories From Barbarians at the Gate ."

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. " Private Fund ."

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. " SEC Proposes to Enhance Private Fund Investor Protection ."

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. " Proposed Rule: Private Fund Advisers; Documentation of Registered Investment Adviser Compliance Reviews ."

Kirkland & Ellis. " SEC Proposes Sweeping Rule Changes for Private Fund Advisers (Part 1 of 2) ."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/GettyImages-957732426-4bf75cb01e6746fc96a7aaf1a570f3a8.jpg)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

- 22 Apr 2024

- Research & Ideas

When Does Impact Investing Make the Biggest Impact?

More investors want to back businesses that contribute to social change, but are impact funds the only approach? Research by Shawn Cole, Leslie Jeng, Josh Lerner, Natalia Rigol, and Benjamin Roth challenges long-held assumptions about impact investing and reveals where such funds make the biggest difference.

- 27 Apr 2023

- Cold Call Podcast

Equity Bank CEO James Mwangi: Transforming Lives with Access to Credit

James Mwangi, CEO of Equity Bank, has transformed lives and livelihoods throughout East and Central Africa by giving impoverished people access to banking accounts and micro loans. He’s been so successful that in 2020 Forbes coined the term “the Mwangi Model.” But can we really have both purpose and profit in a firm? Harvard Business School professor Caroline Elkins, who has spent decades studying Africa, explores how this model has become one that business leaders are seeking to replicate throughout the world in her case, “A Marshall Plan for Africa': James Mwangi and Equity Group Holdings.” As part of a new first-year MBA course at Harvard Business School, this case examines the central question: what is the social purpose of the firm?

- 18 Apr 2023

The Best Person to Lead Your Company Doesn't Work There—Yet

Recruiting new executive talent to revive portfolio companies has helped private equity funds outperform major stock indexes, says research by Paul Gompers. Why don't more public companies go beyond their senior executives when looking for top leaders?

- 13 Dec 2022

The Color of Private Equity: Quantifying the Bias Black Investors Face

Prejudice persists in private equity, despite efforts to expand racial diversity in finance. Research by Josh Lerner sizes up the fundraising challenges and performance double standards that Black and Hispanic investors confront while trying to support other ventures—often minority-owned businesses.

- 30 Nov 2020

- Working Paper Summaries

Short-Termism, Shareholder Payouts, and Investment in the EU

Shareholder-driven “short-termism,” as evidenced by increasing payouts to shareholders, is said to impede long-term investment in EU public firms. But a deep dive into the data reveals a different story.

- 16 Nov 2020

Private Equity and COVID-19

Private equity investors are seeking new investments despite the pandemic. This study shows they are prioritizing revenue growth for value creation, giving larger equity stakes to management teams, and targeting somewhat lower returns.

- 13 Nov 2020

Long-Run Returns to Impact Investing in Emerging Markets and Developing Economies

Examination of every equity investment made by the International Finance Corporation, one of the largest and longest-operating impact investors, shows this portfolio has outperformed the S&P 500 by 15 percent.

- 13 Jan 2020

Do Private Equity Buyouts Get a Bad Rap?

Elizabeth Warren calls private equity buyouts "Wall Street looting," but a recent study by Josh Lerner and colleagues shows they have both positive and negative impacts. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 05 Nov 2019

The Economic Effects of Private Equity Buyouts

Private equity buyouts are a major financial enterprise that critics see as dominated by rent-seeking activities with little in the way of societal benefits. This study of 6,000 US buyouts between 1980 and 2013 finds that the real side effects of buyouts on target firms and their workers vary greatly by deal type and market conditions.

- 16 Oct 2019

Core Earnings? New Data and Evidence

Using a novel dataset of earnings-related disclosures embedded in the 10-Ks, this paper shows how detailed financial statement analysis can produce a measure of core earnings that is more persistent than traditional earnings measures and forecasts future performance. Analysts and market participants are slow to appreciate the importance of transitory earnings.

- 19 Nov 2018

Lazy Prices

The most comprehensive information windows that firms provide to the markets—in the form of their mandated annual and quarterly filings—have changed dramatically over time, becoming significantly longer and more complex. When firms break from their routine phrasing and content, this action contains rich information for future firm stock returns and outcomes.

- 04 Sep 2018

Investing Outside the Box: Evidence from Alternative Vehicles in Private Capital

Private equity vehicles that differ from the traditional structure have become a major portion of investors’ portfolios, especially over the past decade. This study identifies differences in performance across limited and general partners participating in such vehicles, as well as across the two broad classes of alternative vehicles.

- 29 Aug 2018

How Much Does Your Boss Make? The Effects of Salary Comparisons

This study of more than 2,000 employees at a multibillion dollar firm explores how perceptions about peers’ and managers’ salaries affect employee behaviors and preferences for equity. Employees exhibit a high tolerance for inequality when job titles differ, which may explain why incentives are granted through promotions, and gender pay differences are most pronounced across positions.

- 12 Feb 2018

Private Equity, Jobs, and Productivity: Reply to Ayash and Rastad

In 2014, the authors published an influential analysis of private equity buyouts in the American Economic Review. Recently, economists Brian Ayash and Mahdi Rastad have challenged the accuracy of those findings. This new paper responds point by point to their critique, contending that it reflects a misunderstanding of the data and methodology behind the original study.

- 19 Sep 2017

An Invitation to Market Design

Effective market design can improve liquidity, efficiency, and equity in markets. This paper illustrates best practices in market design through three examples: the design of medical residency matching programs, a scrip system to allocate food donations to food banks, and the recent “Incentive Auction” that reallocated wireless spectrum from television broadcasters to telecoms.

- 28 Aug 2017

Should Industry Competitors Cooperate More to Solve World Problems?

George Serafeim has a theory that if industry competitors collaborated more, big world problems could start to be addressed. Is that even possible in a market economy? Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 04 Aug 2017

Private Equity and Financial Fragility During the Crisis

Examining the activity of almost 500 private equity-backed companies during the 2008 financial crisis, this study finds that during a time in which capital formation dropped dramatically, PE-backed companies invested more aggressively than peer companies did. Results do not support the hypothesis that private equity contributed to the fragility of the economy during the recent financial crisis.

- 12 May 2017

Equality and Equity in Compensation

Why do some firms such as technology startups offer the same equity compensation packages to all new employees despite very different cash salaries? This paper presents evidence that workers dislike inequality in equity compensation more than salary compensation because of the perceived scarcity of equity.

- 03 May 2016

Pay Now or Pay Later? The Economics within the Private Equity Partnership

Partnerships are essential to the professional service and investment sectors. Yet the partnership structure raises issues including intergenerational continuity. This study of more than 700 private equity partnerships finds 1) the allocation of fund economics is typically weighted toward the founders of the firms, 2) the distributions of carried interest and ownership substantially affect the stability of the partnership, and 3) partners’ departures have a negative effect on private equity groups’ ability to raise additional funds.

- 15 Feb 2016

Replicating Private Equity with Value Investing, Homemade Leverage, and Hold-to-Maturity Accounting

This paper studies the asset selection of private equity investors and the risk and return properties of passive portfolios with similarly selected investments in publicly traded securities. Results indicate that sophisticated institutional investors appear to significantly overpay for the portfolio management services associated with private equity investments.

- Partnership Perspectives Home

- New Harbor Capital Home

AI and Machine Learning in Private Equity: A Case Study

Feat. Blueprint Prep, a New Harbor Capital portfolio company

In today's ever-evolving technological landscape, private equity firms must remain agile and adaptable to stay on top of advancing technology such as artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning. AI has the power to revolutionize how private equity firms operate, streamlining processes and unlocking the power of data for firms.

In this Partnership Perspectives blog post, we will highlight some ways in which private equity firms like New Harbor Capital and our portfolio companies are beginning to think about and deploy AI.

Identifying Relevant Investment Opportunities

The deal origination process is the heart of any private equity firm’s operations. Firms are constantly looking for new investment opportunities, but it can be challenging to identify relevant deals in a competitive market. AI can help private equity firms identify relevant investment opportunities by analyzing large datasets and identifying patterns and trends that would be difficult or impractical to spot manually. AI can also conduct industry research and competitor analyses to supplement a private equity deal team’s sourcing efforts.

Enhancing the Due Diligence Process

Due diligence is a critical step in the private equity investment process, where firms meticulously assess the risks and opportunities associated with a potential investment. AI can support and streamline the due diligence process by automating repetitive tasks like data aggregation and analysis. AI can quickly and efficiently analyze financial statements, contracts, and other legal documents to identify potential red flags or risks associated with a target company. This not only saves teams time, but also enhances accuracy, ensuring firms gain a comprehensive understanding of a potential investment.

Streamlining Operational Efficiency

AI can modernize operational efficiency for private equity firms by automating repetitive tasks and streamlining internal processes, such as meeting scheduling, compliance and regulatory reporting, and project management, freeing up human capital as a result. This allows private equity professionals to redirect their efforts toward more value-added activities, like deal origination and relationship management.

Blueprint Prep: A Case Study in AI-Powered Personalized Learning

New Harbor is not only leveraging AI at a firm level to gain a competitive advantage - we are also encouraging our portfolio companies to do the same. One example is Blueprint Prep , a leading platform for high-stakes test preparation and continuing education. Blueprint has been using AI to drive personalized learning at scale for several years.

Founded in 2005, Blueprint Prep is a leading platform for test prep related to high stakes exams, certification and licensure in the U.S., offering live and self-paced online courses, private tutoring, self-study materials, and question banks for pre-law, pre-med, and medical school students, as well as residents, practicing physicians, PAs, and NPs.

Blueprint began its journey with AI by focusing on personalized and adaptive practice question banks. The Blueprint team has developed machine learning models that feed each learner the highest-value practice content at every step of their journey. They also use AI tools to build personalized study plans for students.

Most recently, Blueprint released a first-gen AI feature : a conversational AI chatbot that acts as a tutor for MCAT students, helping them understand the strategy behind certain exam questions. The AI chatbot, named Blue, is the first of its kind in the MCAT test preparation market. It can provide students with personalized guidance on how to tackle Critical Analysis and Reasoning Skills (CARS) questions through genuine one-on-one conversations while adapting in real time to their individual learning needs.

The launch of Blue comes at a time when interest in the use of AI in medical school and healthcare education is on the rise. AI offers medical schools the ability to provide a more personalized curriculum that can adjust to each student's needs. As the demand for medical education increases, AI technology is fast becoming necessary to meet the evolving needs and preferences of students.

Blueprint’s Founder and CEO, Matt Riley, believes that AI will continue to be a disruptive force in the education and online learning industry: “In our space, AI will be incredibly beneficial to learners. No longer will they need to labor through piles of content without knowing how to drive results. With AI, we can now make the entire learning journey more efficient and enjoyable, which will unlock tons of untapped human potential.”

As private equity firms strive to maintain competitiveness amidst a constantly evolving technological landscape, the adoption of AI and machine learning will be increasingly important. By embracing AI’s capabilities, private equity firms can gain a distinct advantage — identifying more relevant investment opportunities, enhancing the due diligence process, streamlining internal operations, and adeptly managing risks. As AI continues to advance, private equity firms that embrace and integrate it into their operations and workflows will be at a significant competitive advantage.

Share this post with your networks via the buttons below! Questions? Reach out to us at [email protected] tod ay.

Leave a Comment

Share this post.

Related Posts

Private equity partnerships, why data matters to your private equity partner, aligning priorities in healthcare provider partnerships.

Join 307,012+ Monthly Readers

Get Free and Instant Access To The Banker Blueprint : 57 Pages Of Career Boosting Advice Already Downloaded By 115,341+ Industry Peers.

- Break Into Investment Banking

- Write A Resume or Cover Letter

- Win Investment Banking Interviews

- Ace Your Investment Banking Interviews

- Win Investment Banking Internships

- Master Financial Modeling

- Get Into Private Equity

- Get A Job At A Hedge Fund

- Recent Posts

- Articles By Category

Infrastructure Private Equity: The Definitive Guide

If you're new here, please click here to get my FREE 57-page investment banking recruiting guide - plus, get weekly updates so that you can break into investment banking . Thanks for visiting!

If I put together a list of the longest-running “unfulfilled requests” on this site and BIWS , infrastructure private equity would be near the top of that list.

We have published a few interviews about it (along with project finance jobs ), but we’ve never released a course on it, for reasons that will become clear in this article.

UPDATE: We now have a Project Finance Modeling course . Check it out!

And while I’m skeptical about the long-term prospects of private equity , especially at the mega-funds, there are some bright spots – and I think infrastructure is one of them.

But before delving into deals, top firms, salaries/bonuses, interview questions, and exit opportunities, let’s start with the fundamentals:

What is Infrastructure Private Equity?

At a high level, infrastructure private equity resembles any other type of private equity : firms raise capital from outside investors (Limited Partners) and then use that capital to invest in assets, operate them, and eventually sell them to earn a high return.

Profits are then distributed between the Limited Partners (LPs) and the General Partners (GPs) – with the GPs representing the private equity firm.

Just as in traditional PE, professionals spend their time on origination (finding new assets), execution (doing deals), managing existing assets, and fundraising.

The difference is that infrastructure PE firms invest in assets that provide essential utilities or services.

Real estate private equity is similar because both firm types invest in assets rather than companies.

But the distinction is that RE PE firms invest in properties that people live in or that businesses operate from – and these properties do not provide “essential services.”

Sectors within infrastructure include utilities (gas, electric, and water distribution), transportation (airports, roads, bridges, rail, etc.), social infrastructure (hospitals, schools, etc.), and energy (power plants, pipelines, and renewable assets like solar/wind farms).

Many of these assets are extremely stable and last for decades.

Some, like airports, also have natural monopolies that make them incredibly valuable (well, except for when there’s a pandemic…).

Infrastructure assets have the following shared characteristics:

- Relatively Low Volatility and Stable Cash Flows – Power plants can’t just “shut down” unless human civilization collapses.

- Strong Cash Yields – Unlike traditional leveraged buyouts, where all the returns might depend on the exit, infrastructure assets usually yield high cash flows during the holding period.

- Links to the Macro Environment and Inflation – Investors often view infrastructure assets as “inflation hedges” because they’re linked to population growth, GDP, and other macro factors that change the demand for infrastructure.

- Low Correlation with Other Asset Classes – For example, returns in infrastructure investing don’t correlate that closely with those in traditional PE, equities, fixed income, or even real estate.

On the last point, here’s what JP Morgan found when comparing infrastructure, real estate, and the S&P 500 from 1986 to 2013:

Holding periods are also longer, partially because customer contracts tend to be lengthy, such as power purchase agreements that last for 15 years.

Overall, infrastructure private equity sits above fixed income but below equities in terms of risk and potential returns; it might be comparable to mezzanine funds .

The History and Scale of Infrastructure Investing

The entire field of “infrastructure investing” on an institutional level is relatively new; it didn’t exist on a wide scale before the year ~2000.

It started in Australia in the 1990s, spread to Canada and Europe in the early 2000s, and eventually made its way to the U.S. as well.

Partially because it is a newer field, infrastructure private equity has raised less in funding than real estate private equity or traditional private equity:

- Infrastructure PE: $50 – $100 billion USD per year globally

- Real Estate PE: $100 – $150 billion

- Traditional PE: $200 – $500 billion

Despite the lower fundraising, “small deals” are quite rare in infrastructure because of the nature of the assets.

The average deal size is over $500 million, and the top 10 deals each year are in the multi-billions, up to $10+ billion.

Public Finance vs. Project Finance vs. Infrastructure Private Equity vs. “Infrastructure Investing”

Several terms are closely related to infrastructure, so let’s go down the list and clarify the differences before moving on:

- “Infrastructure Investing” – This one is the broadest term and could refer to investing in the debt or equity of infrastructure assets. Investors could fund the construction of new assets or acquire existing, stabilized ones. And the investors could be PE firms, pensions, sovereign wealth funds , and many others.

- Infrastructure Private Equity – This term refers to investing in the equity of infrastructure assets to gain ownership and control. There are dedicated infra PE firms, but plenty of pensions, large banks, SWFs, and other entities also make “equity investments in infrastructure.”

- Project Finance – This one refers to investing in the debt of infrastructure assets (both new and existing ones), which is mostly about assessing the downside risk, how much money could be lost in the worst-case scenario, and then offering terms commensurate with the risk.

- Public Finance – This one also relates to investing in the debt of infrastructure assets, but in this case, it’s to support governments and tax-exempt entities that need to raise funds to build assets.

Infrastructure Private Equity Strategies

The main investment strategies are similar to the ones in real estate private equity: core , core-plus, value-add , and opportunistic .

The main difference is slightly different names: “greenfield” refers to brand-new assets that a sponsor is building, while “brownfield” refers to existing assets that it is acquiring.

Here’s a quick summary by category:

- Core: There’s limited-to-no growth here; examples might be regulated electricity distribution assets, such as power lines. Governments set rates, so there’s little revenue risk. Most of the returns come from the asset’s cash flows, and the expected IRRs are usually below 10%.

- Core-Plus: These assets have modest growth potential (via additional CapEx or other improvements), or they’re stabilized assets operating in regions outside developed markets. The expected IRRs might be in the low teens.

- Value-Add: These assets require serious operational improvements or re-positioning. The risk and potential returns are higher, and more of the potential returns come from capital appreciation rather than cash flows during the holding period. An example might be acquiring a small airport and then performing additional construction to turn it into more of a regional hub.

- Opportunistic: These deals are the riskiest ones because they often produce limited-to-no cash flow for a long time, and they depend on building new and unproven assets (e.g., a new power plant or toll road). The potential IRRs might be 15%+, but there’s also a huge downside risk.

A single infrastructure PE firm could have different types of funds, each one specializing in one of these categories, but in practice, the first three strategies are the most popular ones.

One final note: in addition to everything above, public-private partnerships (PPP) represent another strategy within this sector.

For example, a private firm might build a toll road, and the local government might guarantee a certain amount in revenue per year as an incentive to complete the project.

Sometimes PPP deals are labeled “core” even when the asset changes significantly or is built from scratch because the revenue risks are much lower if there’s government backing.

Yes, construction overruns and delays could still be issues, but the overall risk is lower.

The Top Infrastructure Private Equity Funds

You can divide infrastructure investors into a few main categories: actual private equity firms (“fund managers”), large banks, pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, and the investment arms of insurance companies.

Technically, only the private equity firms count as “infrastructure private equity” – but each firm type here still invests in the equity of infrastructure assets.

For many years, fund managers dominated the market, but institutional investors such as pension funds have been building their internal investment teams to do deals directly.

Private Equity Firms and Fund Managers

Some PE firms focus on infrastructure; examples include Global Infrastructure Partners, IFM Investors, Stonepeak Infrastructure Partners, I Squared Capital, ArcLight Capital, Dalmore Capital, and Energy Capital Partners.

Then, some firms invest in a broader set of “real assets,” with Brookfield in Canada being the best example (it has also raised the third-highest amount of capital for infrastructure worldwide).

In the U.S., Colony Capital and AMP Capital are examples (they do both real estate and infrastructure).

Finally, there are large, diversified private equity firms that also have a presence in infrastructure, such as KKR, EQT, Blackstone, Ardian, and Carlyle.

Large Banks

The biggest “infrastructure investing firm” worldwide is Macquarie Infrastructure and Real Assets (MIRA) , which is a branch of the Australian bank Macquarie.

Many of the other large banks also do infrastructure investing, but they often use different names for their infra businesses (e.g., Goldman Sachs and “West Street Infrastructure Partners” or Morgan Stanley and “North Haven Infrastructure Partners”).

JP Morgan and Deutsche Bank are also active in the space.

There are also infrastructure investment banking groups , which advise sponsors and asset owners on deals rather than investing in debt or equity directly.

Pension Funds

Canadian pension funds , such as CPPIB and OTPP, are some of the biggest investors in the infrastructure space, and they all have internal teams to do it.

These funds have advantages over traditional PE firms because their returns expectations are lower, and they’re non-taxable in Canada , so they can afford to out-bid other parties and pay high prices for Canadian assets.

In Europe, various pension managers, such as APG and PGGM in the Netherlands and USS in the U.K., also invest in infrastructure, and in Australia, plenty of “superannuation funds” (AustralianSuper, QSuper, etc.) also do domestic infrastructure deals.

Sovereign Wealth Funds

These are very similar to pension funds: historically, they acted as Limited Partners, but they’ve been building their internal teams to invest in infrastructure directly.

Just like pensions, they also target lower returns, but they also have far more capital since they’re backed by governments in places like the Middle East and Asia.

Names include the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority, the Abu Dhabi Investment Council, the China Investment Corporation, and GIC in Singapore.

For more about these points, please see our coverage of investment banking in Dubai and sovereign wealth funds .

Insurance Companies

Most insurance companies do not invest directly in infrastructure, but many are Limited partners of existing funds.

Well-known names include Swiss Life, Allianz Capital Partners in Germany, and Samsung Life Insurance in South Korea.

Other Investment Firms

There are plenty of “miscellaneous” firms that do infrastructure investing as well.

For example, some construction companies invest their cash into infrastructure, and some larger, energy-focused PE funds such as Encap and Riverstone have also gotten into it.

There’s a blurry line between “energy private equity” and “infrastructure private equity” in the U.S., which is why firms like ArcLight and Energy Capital could be in either category.

Infrastructure Private Equity Jobs: The Full Description

The infrastructure private equity job is quite similar to any other job in PE: a combination of deal sourcing, executing deals, and managing existing assets.

Deal sourcing consists of inbound flow from bankers, competitive auctions, secondary deals from other financial sponsors, and sometimes buying entire infrastructure companies or individual assets.

Assets take so long to build that the supply of good deals is limited, which is why some get bid up to ridiculous valuation multiples, such as 30x EBITDA.

When evaluating deals, assessing the downside risk is critical because the upside is quite limited.

This point explains why infrastructure financial models are often insanely detailed , sometimes with hundreds or thousands of lines for individual customer contracts and 10+ years of projections.

You can’t just say, “Assume revenue growth of 5%” – it has to be backed by contract-level data and extensive industry research.

As in real estate, infrastructure deals often use high leverage (think: 80%+), and the debt may be “sculpted” to meet a minimum Debt Service Coverage Ratio (DSCR) requirement:

When you evaluate deals, you focus on:

- Contracts – How does the asset earn revenue, how much water/electricity/energy has it promised to deliver, and are there any onerous terms? Are there step-ups for inflation? Are any counterparties promising to pay for fuel or other expenses?

- Expenses and CapEx – Will the asset need major CapEx for maintenance or expansion? What do its ongoing operating expenses look like, and are they expected to grow in-line with inflation or above/below it?

- Growth Opportunities – The asset’s overall growth rate should be aligned to its key macro drivers, especially for “core” deals. For example, if air traffic in the region is growing at 2% per year, but an airport’s revenue is growing by 5%, something is off – unless the airport is planning to expand in some way.

- Downside Protection – What happens if inflation exceeds expectations? How easily can customers cancel their contracts? If something goes wrong, does the government back the asset or promise anything? What if there’s a construction delay or cost overrun?