10 Books About Emily Dickinson to Read After Watching DICKINSON

Jeffrey Davies

Jeffrey Davies is a professional introvert and writer with imposter syndrome whose work spans the worlds of pop culture, books, music, feminism, and mental health. In addition to Book Riot, his writing has appeared on HuffPost, Collider, PopMatters, Spectrum Culture, and other places. Find him on his website and follow him on Twitter @teeveejeff and Instagram @jeffreyreads . He is also the co-host of a Gilmore Girls podcast, Coffee With a Shot of Cynicism .

View All posts by Jeffrey Davies

Unless you’ve been living under a rock, you’ve probably heard that Apple has come out with their own streaming service, Apple TV+. And if you haven’t dropped everything to go watch future EGOT winner Hailee Steinfeld star as Emily Dickinson on their new series Dickinson , I’m not sure if we can be friends! While the series might not be every literary enthusiast’s cup of tea (they speak in modern vernacular and the soundtrack includes Billie Eilish), it still offers refreshing new insight into the sheltered life of a literary icon who came of age centuries before her time.

If you’ve checked out Dickinson and are looking for some more information on the beloved poet, here are ten titles to check out!

Descriptions are adapted from Goodreads.

Note : Since Emily Dickinson’s lifetime was not a particularly inclusive one for people of color (or women, for that matter), few of these titles were written by authors of color and may not represent the diverse literary atmosphere we strive for here at Book Riot.

Emily Dickinson and the Art of Belief by Roger Lundin

Roger Lundin’s Emily Dickinson and the Art of Belief has been widely recognized as one of the finest biographies of the great American poet Emily Dickinson. Paying special attention to her experience of faith, Lundin skillfully relates Dickinson’s life—as it can be charted through her poems and letters—to 19th century American political, social, religious, and intellectual history.

The Emily Sonnets: The Life of Emily Dickinson by Jane Yolen & Gary Kelley

She was quiet and fiercely private. She was bold and fiercely creative. And it wasn’t until after her death that the world came to know her genius. In The Emily Sonnets , Jane Yolen’s beautiful sonnets and insightful biographical notes spotlight Emily Dickinson’s schooling, seclusion, and the slant rhymes for which she became famous, while Gary Kelley’s captivating artwork portrays the poet’s 19th century Massachusetts world, including her family, faith, and fears.

The Diary of Emily Dickinson by Jamie Fuller & Marlene McLoughlin

The discovery of Emily Dickinson’s poetry after her death unleashed a series of mysteries and revelations that astonished those who knew her and continue to intrigue readers today. Such is the premise of this unique fictional work. This diary begins in March 1867 and ends in April 1868. During this span Dickinson recounts the revelations and trials of her day-to-day life, from burnt puddings to professions of undying love. With discriminating insight, Jamie Fuller helps extract from Dickinson’s cryptic style her views on God, family, nature, death, love, poetry, fame, and her role as a woman in a patriarchal society.

A Voice of Her Own: Becoming Emily Dickinson by Barbara Dana

Before she was an iconic American poet, Emily Dickinson was a spirited girl eager to find her place in the world. Expected by family and friends to mold to the prescribed role for women in mid-1800s New England, Emily was challenged to define herself on her own terms. Barbara Dana brilliantly imagines the girlhood of this extraordinary young woman, capturing the cadences of her unique voice and bringing her to radiant life.

Emily Dickinson Beyond the Myth by Patricia Sierra

Forget what you’ve been taught about Emily Dickinson, discard the myth that has been passed down through the years, and step into Emily’s real life. Although this is a work of fiction, it is told in the first person as if it were an autobiography and contains a mix of both known facts and informed speculation. The Emily Dickinson you’ll meet in these pages is the woman revealed in her letters and in the comments of her contemporaries. She was a strong woman faced with more losses than anyone should have to bear, and her everyday life had more to do with the tasks of maintaining a home than with crafting the perfect poem.

A Loaded Gun: Emily Dickinson for the 21st Century by Jerome Charyn

We think we know Emily Dickinson: the belle of Amherst, virginal, reclusive, and possibly mad. But in A Loaded Gun , Jerome Charyn introduces us to a different Emily Dickinson. Through interviews with contemporary scholars, close readings of Dickinson’s correspondence and handwritten manuscripts, and a suggestive, newly discovered photograph that is purported to show Dickinson with her lover, Charyn’s literary sleuthing reveals the great poet in ways that have only been hinted at previously: as a woman who was deeply philosophical, intensely engaged with the world, attracted to people of various genders, and able to write poetry that disturbs and delights us today.

Miss Emily by Nuala O’Connor

Ada Concannon is the new maid for the respected but eccentric Dickinson family of Amherst, Massachusetts. She befriends Miss Emily, the gifted elder daughter living a spinster’s life at home. Emily is a bastion of support as Ada struggles to find her place in this new world, while Ada’s toil gives Emily the freedom she needs to write. But Emily’s passion for words begins to dominate her life. She decides to wear nothing but white and increasingly avoids the outside world. When Ada’s safety and reputation are threatened, however, Emily faces down her own demons in order to help her friend, with shocking consequences.

My Wars Are Laid Away in Books: The Life of Emily Dickinson by Alfred Habegger

Emily Dickinson, probably the most loved and certainly the greatest of American poets, continues to be seen as the most elusive. One reason she has become a timeless icon of mystery for many readers is that her developmental phases have not been clarified. In this exhaustively researched biography, Alfred Habegger presents the first thorough account of Dickinson’s growth—a richly contextualized story of genius in the process of formation and then in the act of overwhelming production. The definitive treatment of Dickinson’s life and times, and of her poetic development, My Wars Are Laid Away in Books shows how she could be both a woman of her era and a timeless creator. Although many aspects of her life and work will always elude scrutiny, her living, changing profile at least comes into focus in this meticulous and magisterial biography.

These Fevered Days: Ten Pivotal Moments in the Making of Emily Dickinson by Martha Ackmann (February 2020)

Despite spending her days almost entirely “at home” (the occupation listed on her death certificate), Emily Dickinson’s interior world was extraordinary. She loved passionately, was ambivalent toward publication, embraced seclusion, and created 1,789 poems that she tucked into a dresser drawer. In These Fevered Days , forthcoming from W.W. Norton & Company in February 2020, Martha Ackmann unravels the mysteries of Dickinson’s life through ten decisive episodes that distill her evolution as a poet. Ackmann follows Dickinson through her religious crisis while a student at Mount Holyoke, her startling decision to ask a famous editor for advice, her anguished letters to an unidentified “Master,” her exhilarating frenzy of composition, and her terror in confronting possible blindness. Together, these ten days provide new insights into Dickinson’s wildly original poetry and render a concise and vivid portrait of American literature’s most enigmatic figure.

Lives Like Loaded Guns: Emily Dickinson and Her Family’s Feuds by Lyndall Gordon

In 1882, Emily Dickinson’s brother Austin began a passionate love affair with Mabel Todd, a young Amherst faculty wife, setting in motion a series of events that would forever change the lives of the Dickinson family. The feud that erupted as a result has continued for over a century. Lyndall Gordon, an award-winning biographer, tells the riveting story of the Dickinsons, and reveals Emily as a very different woman from the pale, lovelorn recluse that exists in the popular imagination. Thanks to unprecedented use of letters, diaries, and legal documents, Gordon digs deep into the life and work of Emily Dickinson, to reveal the secret behind the poet’s insistent seclusion, and presents a woman beyond her time who found love, spiritual sustenance, and immortality all on her own terms. An enthralling story of creative genius, filled with illicit passion and betrayal, Lives Like Loaded Guns is sure to cause a stir among Dickinson’s many devoted readers and scholars.

Do you have any favorite fascinating books about Emily Dickinson? Or your own favorite poet?

You Might Also Like

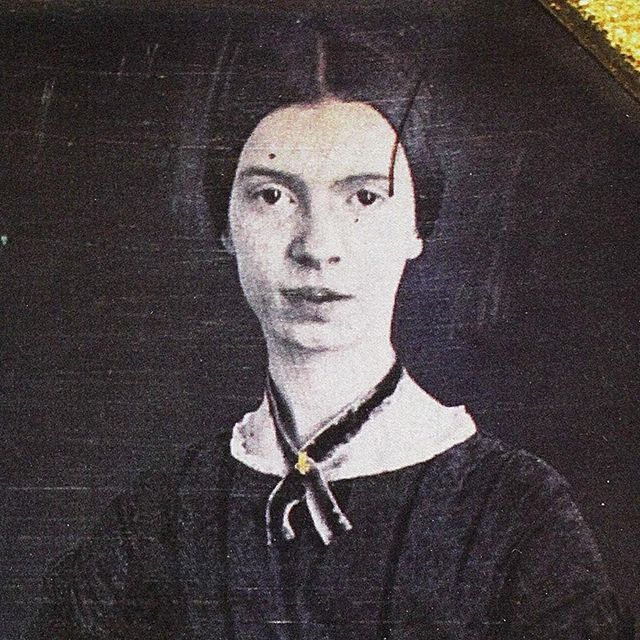

Emily Dickinson

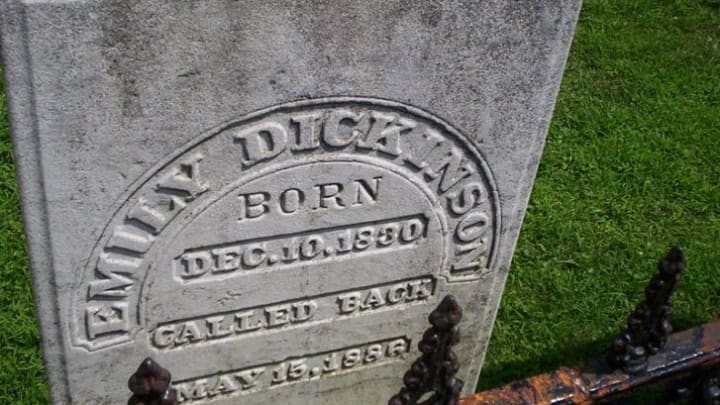

(1830-1886)

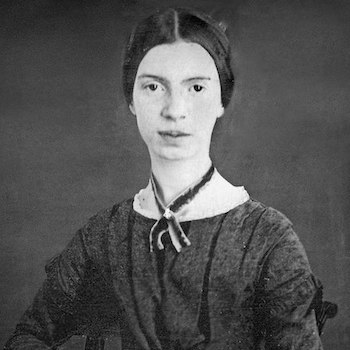

Who Was Emily Dickinson?

Emily Dickinson left school as a teenager, eventually living a reclusive life on the family homestead. There, she secretly created bundles of poetry and wrote hundreds of letters. Due to a discovery by sister Lavinia, Dickinson's remarkable work was published after her death — on May 15, 1886, in Amherst — and she is now considered one of the towering figures of American literature.

Early Life and Education

Dickinson was born on December 10, 1830, in Amherst, Massachusetts. Her family had deep roots in New England. Her paternal grandfather, Samuel Dickinson, was well known as the founder of Amherst College. Her father worked at Amherst and served as a state legislator. He married Emily Norcross in 1828 and the couple had three children: William Austin, Emily and Lavinia Norcross.

An excellent student, Dickinson was educated at Amherst Academy (now Amherst College) for seven years and then attended Mount Holyoke Female Seminary for a year. Though the precise reasons for Dickinson's final departure from the academy in 1848 are unknown; theories offered say that her fragile emotional state may have played a role and/or that her father decided to pull her from the school. Dickinson ultimately never joined a particular church or denomination, steadfastly going against the religious norms of the time.

Family Dynamics and Writing

Among her peers, Dickinson's closest friend and adviser was a woman named Susan Gilbert, who may have been an amorous interest of Dickinson's as well. In 1856, Gilbert married Dickinson's brother, William. The Dickinson family lived on a large home known as the Homestead in Amherst. After their marriage, William and Susan settled in a property next to the Homestead known as the Evergreens. Emily and sister Lavinia served as chief caregivers for their ailing mother until she passed away in 1882. Neither Emily nor her sister ever married and lived together at the Homestead until their respective deaths.

Dickinson's seclusion during her later years has been the object of much speculation. Scholars have thought that she suffered from conditions such as agoraphobia, depression and/or anxiety, or may have been sequestered due to her responsibilities as guardian of her sick mother. Dickinson was also treated for a painful ailment of her eyes. After the mid-1860s, she rarely left the confines of the Homestead. It was also around this time, from the late 1850s to mid-'60s, that Dickinson was most productive as a poet, creating small bundles of verse known as fascicles without any awareness on the part of her family members.

In her spare time, Dickinson studied botany and produced a vast herbarium. She also maintained correspondence with a variety of contacts. One of her friendships, with Judge Otis Phillips Lord, seems to have developed into a romance before Lord's death in 1884.

Death and Discovery

Dickinson died of heart failure in Amherst, Massachusetts, on May 15, 1886, at the age of 55. She was laid to rest in her family plot at West Cemetery. The Homestead, where Dickinson was born, is now a museum .

Little of Dickinson's work was published at the time of her death, and the few works that were published were edited and altered to adhere to conventional standards of the time. Unfortunately, much of the power of Dickinson's unusual use of syntax and form was lost in the alteration. After her sister's death, Lavinia discovered hundreds of poems that Dickinson had crafted over the years. The first volume of these works was published in 1890. A full compilation, The Poems of Emily Dickinson , wasn't published until 1955, though previous iterations had been released.

Dickinson's stature as a writer soared from the first publication of her poems in their intended form. She is known for her poignant and compressed verse, which profoundly influenced the direction of 20th-century poetry. The strength of her literary voice, as well as her reclusive and eccentric life, contributes to the sense of Dickinson as an indelible American character who continues to be discussed today.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Emily Dickinson

- Birth Year: 1830

- Birth date: December 10, 1830

- Birth State: Massachusetts

- Birth City: Amherst

- Birth Country: United States

- Gender: Female

- Best Known For: Emily Dickinson was a reclusive American poet. Unrecognized in her own time, Dickinson is known posthumously for her innovative use of form and syntax.

- Fiction and Poetry

- Writing and Publishing

- Astrological Sign: Sagittarius

- Mount Holyoke Female Seminary

- Amherst Academy (now Amherst College)

- Interesting Facts

- In addition to writing poetry, Emily Dickinson studied botany. She compiled a vast herbarium that is now owned by Harvard University.

- Death Year: 1886

- Death date: May 15, 1886

- Death State: Massachusetts

- Death City: Amherst

- Death Country: United States

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Emily Dickinson Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/authors-writers/emily-dickinson

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: May 7, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

- 'Hope' is the thing with feathers - That perches in the soul - And sings the tunes without the words - And never stops - at all -

- Dwell in possibility.

- The Truth must dazzle gradually/Or every man be blind.

- Truth is so rare, it is delightful to tell it.

- If I read a book and it makes my whole body so cold no fire can warm me I know that is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only way I know it. Is there any other way?

- Success is counted sweetest/By those who ne'er succeed./To comprehend a nectar/Requires sorest need.

Watch Next .css-smpm16:after{background-color:#323232;color:#fff;margin-left:1.8rem;margin-top:1.25rem;width:1.5rem;height:0.063rem;content:'';display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;}

William Shakespeare

How Did Shakespeare Die?

Christine de Pisan

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

14 Hispanic Women Who Have Made History

10 Famous Langston Hughes Poems

5 Crowning Achievements of Maya Angelou

Amanda Gorman

Langston Hughes

7 Facts About Literary Icon Langston Hughes

Maya Angelou

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

A bomb in her bosom: Emily Dickinson's secret life

Beneath the still surface of the poet’s life lay a fiercely passionate nature and a closely guarded secret, argues her latest biographer

E mily Dickinson was a great poet whose life has remained a mystery. The time has come to dispel the myth of a quaint and helpless creature, disappointed in love, who gave up on life. I think she was unafraid of her own passions and talent; that her brother's sexual betrayal and subsequent family feud had a profound effect on the Dickinson legend that has come down to us; and perhaps most significantly, I believe that Emily had an illness – a secret that explains much.

It was Emily herself who helped to devise the blueprint for her legend, starting at the age of 23 when she declined an invitation from a friend: "I'm so old-fashioned, Darling, that all your friends would stare." In place of the tart young woman she was, she adopted this retiring posture. Born in 1830 into the leading family of Amherst, a college town in Massachusetts, she never left what she always called "my father's house". Townsfolk spoke of her as "the Myth".

On the face of it, the life of this New England poet seems uneventful and largely invisible, but there's a forceful, even overwhelming character belied by her still surface. She called it a "still – Volcano – Life", and that volcano rumbles beneath the domestic surface of her poetry and a thousand letters. Stillness was not a retreat from life (as legend would have it) but her form of control. Far from the helplessness she played up at times, she was uncompromising; until the explosion in her family, she lived on her own terms.

Her widely spaced eyes were too keen for the passivity admired in women of her time. It's the sensitive face of a person who (as her brother put it) "saw things directly and just as they were". At 17, as a student at Mount Holyoke in 1848 (the same year that the women's movement took a stand at Seneca Falls), she refused to bend to the founder of her college, the formidable Mary Lyon. At this time Massachusetts was the scene of a religious revival opposed to the inroads of science. Emily, who had chosen mostly science courses, makes her allegiance clear:

"Faith" is a fine invention

When Gentlemen can see –

But Microscopes are prudent

In an Emergency.

When Miss Lyon pressed her students to be "saved", nearly all succumbed. Emily did not. On 16 May, she owned, "I have neglected the one thing needful when all were obtaining it." It seemed that other girls desired only to be good. "How I wish I could say that with sincerity, but I fear I never can." When Miss Lyon consigned her to the lowest of three categories – the saved, the hopeful and a remnant of about 30 no-hopers – she still held out.

During a creative burst in the early 1860s, she invited a Boston man of letters to be her mentor, but could not take his advice to regularise her verse. Helpful Mr Higginson, a supporter of women, who thought he was corresponding with an apologetic, self-effacing spinster, was puzzled to find himself "drained" of "nerve-power" after his first visit to her in 1870. He was unable to describe the creature he found beyond a few surface facts: she had smooth bands of red hair and no good features; she had been deferential and exquisitely clean in her white piqué dress and blue crocheted shawl; and after an initial hesitation, she had proved surprisingly articulate. She had said a lot of strange things, from which Higginson deduced an "abnormal" life.

There was an increasing divide between people she wished to know and those she didn't. Her clarity could not endure social talk instead of truth; piety instead of "The Soul's Superior instants". Her directness would have been disconcerting if she did not "simulate" conventionality, and this was "stinging work". But a more threatening challenge, deeper below the surface, fired the volcanoes and earthquakes in her poems – an event, as she put it, that "Struck – my ticking – through –".

Something in her life has so far remained sealed. The poems tease the reader about "it" and her almost overwhelming temptation to "tell". I want to open up the possibility of an unsentimental answer. If true, it would explain the conditions of her life: her seclusion and refusal to marry. Once we know what "it" is, it will be obvious why "it" was buried and why its lava jolts out from time to time through the crater of her "buckled lips".

During the poetic spurt of her early 30s, Dickinson transforms sickness into a story of promise:

My loss, by sickness – Was it Loss?

Or that Etherial Gain –

One earns by measuring the Grave –

Then – measuring the Sun –

Sickness is always there, shielded by cover stories: in youth, a cough is mentioned; in her mid-30s, trouble with her eyes. Neither came to much. In her poems, sickness can be violent: she speaks of "Convulsion" or "Throe". There's a mechanism breaking down, a body dropping. It "will not stir for Doctors". "I felt a Funeral, in my Brain", she says, and "I dropped down, and down". Allowing for the poet's resolve to tell it "slant", through metaphor, are we not looking at epilepsy?

In its full-blown form, known as grand mal, a slight swerve in a pathway of the brain prompts a seizure. As Dickinson puts it, "The Brain within its Groove / Runs evenly", but then a "Splinter swerve" makes it hard to put the current back. Such force has this altered current that it would be easier to divert the course of a flood, when "Floods have slit the Hills / And scooped a Turnpike for Themselves".

Since the falling sickness, as epilepsy used to be known, had shaming associations with "hysteria", masturbation, syphilis and impairment of the intellect leading to "epileptic insanity", it was unnameable, particularly when it struck a woman. In the case of men secrecy was less strict, and fame in a few – Caesar, Muhammad, Dostoevsky – overrode the stigma, but a woman had to bury herself in a lifelong silence. If this guess is right, it's remarkable that Dickinson developed a voice from within that silence, one with a volcanic power to bide its time.

Prescriptions (one from an eminent physician, others in the records of an Amherst drugstore) show that Dickinson's medications tally with contemporary treatments for epilepsy. The condition, which has a genetic component, appeared in two other members of the Dickinson family. One was Cousin Zebina, a lifelong invalid, immured at home across the road, whose bitten tongue in the course of a "fit" is noted by Emily in her first surviving letter at the age of 11. "I fit for them," she announced in a poem of c1866. Then her nephew, Ned Dickinson, turned out to be afflicted. He was the son of Emily's brother Austin and his wife Susan Dickinson, who lived next door. To the family's dismay Ned, aged 15, had an epileptic fit in 1877. Horrendous attacks continued, about eight a year, recorded in his father's diary.

We can't know whether Emily Dickinson suffered as her nephew did. There are many forms of epilepsy, and the mild petit mal does not involve convulsions. The mildest manifestations are absences. A schoolmate remembered that Emily dropped crockery. Plates and cups seemed to slide out of her hands and lay in pieces on the floor. The story was designed to bring out her eccentricity for, it was said, she hid the fragments in the fireplace behind a fireboard, forgetting they were bound to be discovered in winter. This memory is more important than the schoolmate realised, because it suggests absences, either accompanying the condition or the condition itself.

Her violent images, the "spasmodic" rhythms Higginson deplored, and the sheer volume of her output show that she coped inventively with gunshots from the brain into the body. She turned an explosive sickness into well-aimed art: scenes with "Revolver" and "Gun". Contained in her own domestic order, protected by her father and sister, Dickinson saved herself from the anarchy of her condition and put it to use.

The mystery the poet was not to "tell" continues to this day to be encased in claims put out by opposed camps who fought for possession of her greatness. These camps go back to the feud. It began with adultery between Emily's brother Austin, in his 50s, and a newcomer to Amherst, a young faculty wife of 27, Mabel Loomis Todd. After the poet's death, the feud came to focus on Emily as her fame grew: who was to own her unpublished papers? Who had the right to claim her?

Both camps proceeded to wrap the poet in legends that stress her pathos: where Dickinson legend built up a bereft Emily in a dimity apron turning away the one and only man she loved, Todd legend built up a pitiful Emily "hurt" by her "cruel" sister-in-law, Susan Dickinson. How can we crack through the sad-sweet picture to find what Dickinson called the red "Fire rocks" below?

One way is to go back to acts of adultery that changed utterly those who were to be the first keepers of her papers. The advantage of approaching the poet through the feud is the entrée it provides to emotional currents in the family. Assignations – sometimes "with a witness" – are on record, recounted precisely as to time and place in the lovers' corroborating diaries. The impact of adultery on the family is plain – and not so plain, for the riddles in the poet's notes to her brother's mistress must be solved if we are to understand where she stood.

A recurring fact during the first years of the affair is crucial to the poet's position. Because it was difficult to keep adultery secret from the tattle of a small town, the safest place was the irreproachable home of the Dickinson sisters. There, the lovers would occupy the library or the dining-room (with its black horsehair sofa) for two to three hours. The door would be shut, blocking the poet's access to her second writing table in one room or to her conservatory via the other.

Austin Dickinson blew apart his family when he rejected his wife, Susan, who had long been the poet's keenest reader. Who had they been before this happened, and why, earlier, did Dickinson speak of a "Bomb" in her bosom? The Bomb may refer to periodic explosions in the brain, but emotionally both Austin and Emily had an eruptive vein, which Emily channelled into poetry. Her letters show that she cultivated adulterous emotions, if only in fantasy, for an unnamed "Master". How did this affect her response to her brother's sudden outbreak into active adultery?

In September 1881, David Todd and his wife, Mabel, had arrived in Amherst from Washington. She was a dressy urban beauty bent on maintaining standards in what appeared to her a negligible "village" full of retired clergymen and elderly academics. Mrs Todd, extending an immaculate white glove, her smile sliding up one cheek, was invited everywhere and was in a position to choose whom to favour. In Amherst, the Dickinsons were like royalty: Mrs Todd was taken with "regal", "magnificent" Austin Dickinson and his wife's dark poise, set off by a scarlet India shawl, when they called on her. Behind Austin's back, Amherst children mocked his auburn hair, arrayed like a fan above his head, and his sniffy walk, tapping his cane as he went.

At first, all the Dickinsons (bar Emily, who kept to her room) warmed to Mrs Todd's accomplishments: her solos soared above the church choir, she painted flowers to professional standard and published stories in magazines. She soon won the friendship of the bookish Susan Dickinson, before it became apparent that she was flirting with Susan's son, 20-year-old Ned, who fell painfully in love. This happened just before his father became a rival. Austin's love for Mabel Todd was to last for the rest of his life.

The result was what came to be known as "the War between the Houses". Austin turned against his children when they sided with their distraught mother. New evidence reveals that, far from withdrawing from the feud, Emily Dickinson took a stand. Unlike her sister Lavinia, who sided with the lovers, she refused to oblige her brother by signing over a plot of Dickinson land to his mistress. In August 1885 the poet wrote to her nephew Ned, confirming her resistance. "Dear Boy," she starts her letter assuring him he would find "no treason". "You never will, My Ned." This letter ends: "And ever be sure of me, Lad – Fondly, Aunt Emily.

When she died, Mabel got her land. Three weeks after the funeral the deed was signed and the Todds' house rose on the Dickinson meadow – a venue for future assignations.

This might have been a routine story of a femme fatale were it not for the presence of mysterious genius. As the feud sharpened its focus on the poet, it would be seen how Mabel had quickened to the poems of Emily Dickinson and how willing Mabel would be to undertake years of toil with difficult manuscripts. She was to show herself ready in other ways, one of only three people during the poet's lifetime to recognise Dickinson's genius. The name of Mabel Loomis Todd will always be associated with the poet.

Mabel appears to act out a familiar plot – the seduction of a man in power – but what differs here is the presence of another and grander form of power, that of a poet who selects her own society, then shuts the door. To Mabel Todd, with her discerning taste, that shut door, and the elect intelligence behind it, offered an irresistible challenge. So, on 10 September 1882, accompanied by Austin, Mrs Todd knocked on the Homestead door, and had herself admitted to the parlour where she sang to Lavinia and Austin. As she did so, Mabel imagined the poet listening in her fastness upstairs, captivated, as the trained voice trilled through the house.

Over the years to come Mabel was to re-enact this scene, fantasising a bond with the invisible poet. She would insist on this bond yet although she was in and out of the Homestead, she never once laid eyes on Emily Dickinson. On this initial occasion, the poet sent in a glass of homemade cordial together with a poem, which Mabel told herself had been composed spontaneously as a tribute to so pleasing a guest. Then, within 24 hours, on 11 September, there was a declaration of love for Austin – the "Rubicon" where he abandoned marital fidelity at the gate of his home before the pair entered to play a game of whist with the unsuspecting Sue.

Mabel's entry into the Homestead looks politely innocuous beside this initiation of adultery, but it was to present a parallel and more lasting threat to family peace. In time, Mabel would take possession of a large cache of Emily Dickinson's papers, and market them in her own terms, so that the strange nature of the poet would be obscured as a victim of Susan Dickinson. So it was that an eruptive poet sending out her "bolts", "Queen" of her own existence, would be subject to a false plot acted out in the unstoppable momentum of Todd's takeover.

A new and prolonged phase in the war between the houses began with the poet's death in 1886 and her sister's discovery of a lifetime's poems in her chest of drawers. Within a short time, Austin persuaded Lavinia to hand over the papers to his mistress. Yet Austin must have been aware that in his own home, his estranged wife treasured a separate collection – poems Emily had given her over the years. Fuelled by adultery, antagonism between Susan Dickinson and Mabel Todd mounted over possession of the poet, with the success of Todd's four editions of Dickinson (two co-edited with Higginson, two put out on her own) during the 1890s followed by the poet's growing stature in the course of the 20th century. Insistent legend continued to wrap her in the image of the modest, old-fashioned spinster. But the bold voice of the poems can't be categorised: "I'm Nobody," she says, "– who are you?" It's a voice we can't ignore, confrontational, even invasive, defying façades with a question about our nature.

The feud fed into a succession of increasingly public conflicts, starting with a court case in 1898 when Lavinia Dickinson changed sides and took a stand of her own against the Todds' further claim to Dickinson land. At the heart of the trial is Mabel Todd's assertion that this strip of land was due to her as compensation for her years of toil in bringing a great poet before the public. Poems (1890) had sold 11,000 copies in its first year. Her defence turned on her undoubted feat in transcribing, dating and editing piles upon piles of unpublished manuscripts.

Hatred did not die with the deaths of the first generation. The daughters of the feud, Susan's daughter Martha Dickinson and Mabel's daughter Millicent Todd, did battle through adversarial books during the first half of the 20th century. At its height in the 1950s, the feud turned into a conflict over the sale of the Dickinson papers.

The Dickinson camp appeared to win that round. But before Millicent Todd died in 1968, she set up a posthumous campaign that could not fail. Her plan was to co-opt a writer of impeccable credentials for a book she had in mind. To this end she appointed Yale professor Richard B Sewall as her literary executor, granting him exclusive rights to the Todd papers. Her partisan agenda was clear: this executor was to "set the whole network of Dickinson tensions in proper perspective". So it came about that Sewall perpetuated the Todd positions in a two-volume biography of Emily Dickinson that has remained standard for the last 36 years.

Mabel Todd's persuasive grace in presenting her point of view was reinforced by the educated rigour of her daughter's voice on tape as she took Sewall through the legal history of the feud, bristling with facts and dates. These she laid out in the orderly manner of a scholar. To the unwary her testimony would appear objective and informed, and yet in every instance the Todds turn out to be the victims of Susan Dickinson and her fearsome daughter. To hear the tapes is to understand their impact on a biographer. Sewall felt "haunted" by Austin's statement that he went to his wedding as to his execution. Only no one can know what Austin said: the image of execution was transmitted by a mistress determined to oust his wife, and not only in the usual manner, but in various ways to obliterate Sue's centrality in the poet's life.

A biographer tempted by exclusive access to an archive of such eloquence is bound to be influenced, and though Sewall relayed what he found in a cautious manner, he passed on the trove of Todd untruths: that Emily Dickinson had favoured Mabel; that the poet's withdrawal into seclusion had been the result of a family split preceding Mabel's appearance; and that Austin (contrary to evidence in the trial) had "deeded" to the Todds a second strip of land. The biographer even outdoes the Todds when he suggests that Dickinson's "failure" to publish was a result of a family quarrel.

Legends of this kind spread to theatre and fiction. In 1976 an award-winning play The Belle of Amherst reinvigorated the sad-sweet image: a "shy", "chaste", "frightened" poet hardly knows what she says, so keeps busy with baking. The playwright called it an "enterprise of simple beauty", backed by "audiences who have taken our 'Belle' to their hearts". In a novel of 2006 a spiteful Sue ends up "hating" Emily. In a novel of 2007 Sue becomes a death-dealing Lucrezia Borgia. She awaits her victims in the hall of her house, a vamp in décolleté black velvet waving her fan. Can evil go further? It can. Sue "could make mincemeat pie of the Dickinson sisters and eat it for Christmas dinner".

So the pathos has persisted even though Dickinson's words reveal a woman who was fun: a lover who joked; a mystic who mocked heaven. This woman was not like us: to know her is to encounter aspects of a nature more developed than our own. Her poems turn on the communicative power of the unstated between two people attuned to it. So, the question of contacts is crucial: for whom is she writing? Who is being trained in her unique mode of communication? Who provokes her to further communication? "Be Sue – while I am Emily – ", she commanded the friend of her youth who became her sister-in-law, "Be next – what you have ever been – Infinity".

An initiation in infinitude was the gift Dickinson offered to the few she admitted to intimacy. Sewall's assumption that men changed her has dated. It was she who operated on others for the brief periods they could bear it. She created certain people in the same way as she created her poems, many enclosed in letters as extensions of them. She half-found, half-invented a receptive reader in Sue to whom she sent 276 poems – more than twice the number sent to anyone else. In a similar way she created a deathless love for the person whom she called "Master".

Biographers have sought meaning behind the bearded and married "Master", who appears in three mysterious letters from spring 1858 to the summer of 1861. Evidence remains thin, and biographers have taken their pick from an array of unlikely candidates. These letters race from one literary drama to another, including Jane Eyre's encounter with her married "Master" and deathless love in Emily Brontë – in 1858 Dickinson had acquired a copy of an 1857 edition of Wuthering Heights – and it seems likely that the "Master" letters were as much exercises in composition as letters addressing a particular person. The most popular candidate originated in hearsay that the love of Dickinson's life had been the married Rev Charles Wadsworth, whom she met during a visit to Philadelphia in 1855 and then, supposedly, renounced. (Lugubrious, beardless, with stringy locks, Wadsworth sent Miss "Dickenson" a dull pastoral letter about her sufferings – without a clue what those sufferings were.)

In her late 40s and 50s, a new drama began when she turned to fierce Judge Lord of the Massachusetts supreme court. But though she thought of his touch at night, interrupted her writing to anticipate his weekly letter and played up to the comic character he assigned as "Emily Jumbo", she would not marry him. Epileptics in her time were not supposed to marry, and some American states passed laws against it. Drafts of her love letters have survived: they are witty, confident, open (not coded like letters to "Master"), and within the limits of her unrelenting control over her existence, abandoned – hardly the way 19th-century ladies were supposed to behave.

Dickinson found love, spiritual quickening and immortality, all on her own terms. One model remained: Wuthering Heights . Yet unlike the anarchic lovers of the Heights, Dickinson was a moral being, a product of upright New England: she grasped the potential destructiveness – to her sanity, for a start – of the "Bomb" in her bosom; and she witnessed the eruption of the feud – during her lifetime, another secret within the family. She refers repeatedly to a secret "Existence" – primarily her poetry – that must be seen in terms of New England individualism, the Emersonian ethos of self-reliance that in its fullest bloom eludes label. It's more awkward and less lovable than English eccentricity – dangerous, in fact, as Dickinson owned when she said, "My Life had stood – a Loaded Gun –".

- Emily Dickinson

- Biography books

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

- National Poetry Month

- Materials for Teachers

- Literary Seminars

- American Poets Magazine

Main navigation

- Academy of American Poets

User account menu

Search more than 3,000 biographies of contemporary and classic poets.

Page submenu block

- literary seminars

- materials for teachers

- poetry near you

Emily Dickinson

Emily Dickinson was born on December 10, 1830, in Amherst, Massachusetts. She attended Mount Holyoke Female Seminary in South Hadley, but only for one year. Her father, Edward Dickinson, was actively involved in state and national politics, serving in Congress for one term. Her brother, Austin, who attended law school and became an attorney, lived next door with his wife, Susan Gilbert. Dickinson’s younger sister, Lavinia, also lived at home, and she and Austin were intellectual companions for Dickinson during her lifetime.

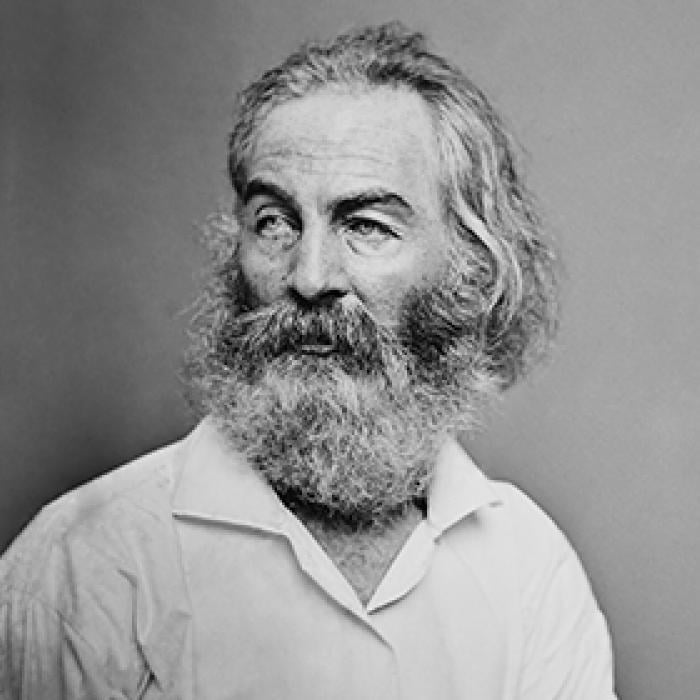

Dickinson’s poetry was heavily influenced by the Metaphysical poets of seventeenth-century England, as well as her reading of the Book of Revelation and her upbringing in a Puritan New England town, which encouraged a Calvinist, orthodox, and conservative approach to Christianity. She admired the poetry of Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning , as well as John Keats . Though she was dissuaded from reading the verse of her contemporary Walt Whitman by rumors of its disgracefulness, the two poets are now connected by the distinguished place they hold as the founders of a uniquely American poetic voice. While Dickinson was extremely prolific and regularly enclosed poems in letters to friends, she was not publicly recognized during her lifetime. The first volume of her work was published posthumously in 1890 and the last in 1955. She died in Amherst in 1886.

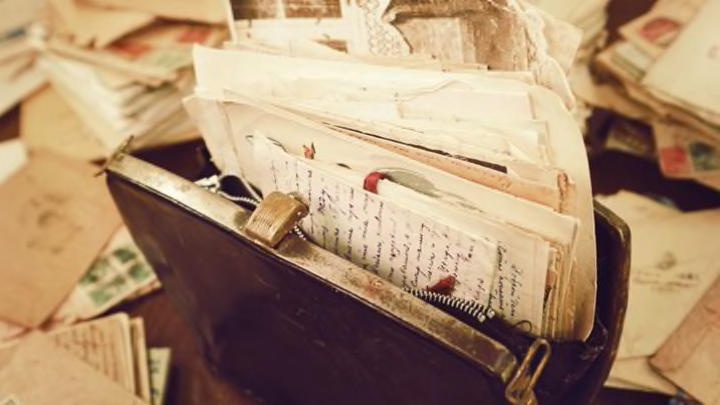

Upon her death, Dickinson’s family discovered forty handbound volumes of nearly 1,800 poems, or “fascicles,” as they are sometimes called. Dickinson assembled these booklets by folding and sewing five or six sheets of stationery paper and copying what seem to be final versions of poems. The handwritten poems show a variety of dash-like marks of various sizes and directions (some are even vertical). The poems were initially unbound and published according to the aesthetics of her many early editors, who removed her annotations. The current standard version of her poems replaces her dashes with an en-dash, which is a closer typographical approximation to her intention. The original order of the poems was not restored until 1981, when Ralph W. Franklin used the physical evidence of the paper itself to restore her intended order, relying on smudge marks, needle punctures, and other clues to reassemble the packets. Since then, many critics have argued that there is a thematic unity in these small collections, rather than their order being simply chronological or convenient. The Manuscript Books of Emily Dickinson (Belknap Press, 1981) is the only volume that keeps the order intact.

Related Poets

William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth, who rallied for “common speech” within poems and argued against the poetic biases of the period, wrote some of the most influential poetry in Western literature, including his most famous work, The Prelude , which is often considered to be the crowning achievement of English romanticism.

W. B. Yeats

William Butler Yeats, widely considered one of the greatest poets of the English language, received the 1923 Nobel Prize for Literature. His work was greatly influenced by the heritage and politics of Ireland.

Walt Whitman

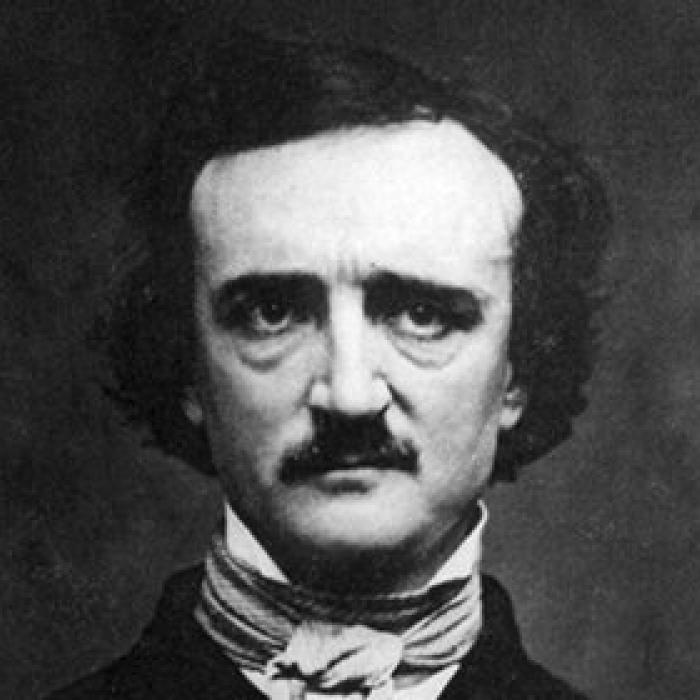

Edgar Allan Poe

Born in 1809, Edgar Allan Poe had a profound impact on American and international literature as an editor, poet, and critic.

William Blake

William Blake was born in London on November 28, 1757, to James, a hosier, and Catherine Blake. Two of his six siblings died in infancy. From early childhood, Blake spoke of having visions—at four he saw God "put his head to the window"; around age nine, while walking through the countryside, he saw a tree filled with angels.

Newsletter Sign Up

- Academy of American Poets Newsletter

- Academy of American Poets Educator Newsletter

- Teach This Poem

My Wars Are Laid Away in Books: The Life of Emily Dickinson

Alfred habegger.

800 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 2001

About the author

Ratings & Reviews

What do you think? Rate this book Write a Review

Friends & Following

Community reviews.

"At certain levels, we are not meant to understand at all , and our interpretation, indeed our reading itself, is an intrusion."

Join the discussion

Can't find what you're looking for.

- Literature & Fiction

- History & Criticism

Enjoy fast, free delivery, exclusive deals, and award-winning movies & TV shows with Prime Try Prime and start saving today with fast, free delivery

Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new: .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } $43.10 $ 43 . 10 FREE delivery Wednesday, May 29 Ships from: Amazon Sold by: Ibook USA

Return this item for free.

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Save with Used - Good .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } $17.04 $ 17 . 04 FREE delivery Wednesday, May 29 on orders shipped by Amazon over $35 Ships from: Amazon Sold by: Laurie Lucille

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Follow the author

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

The Life of Emily Dickinson Paperback – July 15, 1998

Purchase options and add-ons.

- Print length 924 pages

- Language English

- Publisher Harvard University Press

- Publication date July 15, 1998

- Dimensions 6 x 1.7 x 9 inches

- ISBN-10 0674530802

- ISBN-13 978-0674530805

- See all details

Frequently bought together

Editorial Reviews

Amazon.com review, about the author, product details.

- Publisher : Harvard University Press; Reprint edition (July 15, 1998)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 924 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0674530802

- ISBN-13 : 978-0674530805

- Item Weight : 2.67 pounds

- Dimensions : 6 x 1.7 x 9 inches

- #1,598 in Literary Criticism & Theory

- #2,545 in Author Biographies

- #5,786 in Women's Biographies

About the author

Richard benson sewall.

Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read author blogs and more

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

Biography of Emily Dickinson, American Poet

Famously reclusive and experimental in poetic form

Culture Club / Getty Images

- Favorite Poems & Poets

- Poetic Forms

- Best Sellers

- Classic Literature

- Plays & Drama

- Shakespeare

- Short Stories

- Children's Books

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/ThoughtCo_Amanda_Prahl_webOG-48e27b9254914b25a6c16c65da71a460.jpg)

- M.F.A, Dramatic Writing, Arizona State University

- B.A., English Literature, Arizona State University

- B.A., Political Science, Arizona State University

Emily Dickinson (December 10, 1830–May 15, 1886) was an American poet best known for her eccentric personality and her frequent themes of death and mortality. Although she was a prolific writer, only a few of her poems were published during her lifetime. Despite being mostly unknown while she was alive, her poetry—nearly 1,800 poems altogether—has become a staple of the American literary canon, and scholars and readers alike have long held a fascination with her unusual life.

Fast Facts: Emily Dickinson

- Full Name: Emily Elizabeth Dickinson

- Known For: American poet

- Born: December 10, 1830 in Amherst, Massachusetts

- Died: May 15, 1886 in Amherst, Massachusetts

- Parents: Edward Dickinson and Emily Norcross Dickinson

- Education: Amherst Academy, Mount Holyoke Female Seminary

- Published Works: Poems (1890), Poems: Second Series (1891), Poems: Third Series (1896)

- Notable Quote: "If I read a book and it makes my whole body so cold no fire can ever warm me, I know that is poetry."

Emily Elizabeth Dickinson was born into a prominent family in Amherst, Massachusetts. Her father, Edward Dickinson, was a lawyer, a politician, and a trustee of Amherst College , of which his father, Samuel Dickinson, was a founder. He and his wife Emily (nee Norcross ) had three children; Emily Dickinson was the second child and eldest daughter, and she had an older brother, William Austin (who generally went by his middle name), and a younger sister, Lavinia. By all accounts, Dickinson was a pleasant, well-behaved child who particularly loved music.

Because Dickinson’s father was adamant that his children be well-educated, Dickinson received a more rigorous and more classical education than many other girls of her era. When she was ten, she and her sister began attending Amherst Academy, a former academy for boys that had just begun accepting female students two years earlier. Dickinson continued to excel at her studies, despite their rigorous and challenging nature, and studied literature, the sciences, history, philosophy, and Latin. Occasionally, she did have to take time off from school due to repeated illnesses.

Dickinson’s preoccupation with death began at this young age as well. At the age of fourteen, she suffered her first major loss when her friend and cousin Sophia Holland died of typhus . Holland’s death sent her into such a melancholy spiral that she was sent away to Boston to recover. Upon her recovery, she returned to Amherst, continuing her studies alongside some of the people who would be her lifelong friends, including her future sister-in-law Susan Huntington Gilbert.

After completing her education at Amherst Academy, Dickinson enrolled at Mount Holyoke Female Seminary. She spent less than a year there, but explanations for her early departure vary depending on the source: her family wanted her to return home, she disliked the intense, evangelical religious atmosphere, she was lonely, she didn’t like the teaching style. In any case, she returned home by the time she was 18 years old.

Reading, Loss, and Love

A family friend, a young attorney named Benjamin Franklin Newton, became a friend and mentor to Dickinson. It was most likely him who introduced her to the writings of William Wordsworth and Ralph Waldo Emerson , which later influenced and inspired her own poetry. Dickinson read extensively, helped by friends and family who brought her more books; among her most formative influences was the work of William Shakespeare , as well as Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre .

Dickinson was in good spirits in the early 1850s, but it did not last. Once again, people near to her died, and she was devastated. Her friend and mentor Newton died of tuberculosis, writing to Dickinson before he died to say he wished he could live to see her achieve greatness. Another friend, the Amherst Academy principal Leonard Humphrey, died suddenly at only 25 years old in 1850. Her letters and writings at the time are filled with the depth of her melancholy moods.

During this time, Dickinson’s old friend Susan Gilbert was her closest confidante. Beginning in 1852, Gilbert was courted by Dickinson’s brother Austin, and they married in 1856, although it was a generally unhappy marriage. Gilbert was much closer to Dickinson, with whom she shared a passionate and intense correspondence and friendship. In the view of many contemporary scholars, the relationship between the two women was, very likely, a romantic one , and possibly the most important relationship of either of their lives. Aside from her personal role in Dickinson’s life, Gilbert also served as a quasi-editor and advisor to Dickinson during her writing career.

Dickinson did not travel much outside of Amherst, slowly developing the later reputation for being reclusive and eccentric. She cared for her mother, who was essentially homebound with chronic illnesses from the 1850s onward. As she became more and more cut off from the outside world, however, Dickinson leaned more into her inner world and thus into her creative output.

Conventional Poetry (1850s – 1861)

I'm nobody who are you (1891).

I'm Nobody! Who are you? Are you — Nobody — too? Then there's a pair of us! Don't tell! they'd advertise — you know. How dreary — to be — Somebody! How public — like a Frog — To tell one's name — the livelong June — To an admiring Bog!

It’s unclear when, exactly, Dickinson began writing her poems, though it can be assumed that she was writing for some time before any of them were ever revealed to the public or published. Thomas H. Johnson, who was behind the collection The Poems of Emily Dickinson , was able to definitely date only five of Dickinson's poems to the period before 1858. In that early period, her poetry was marked by an adherence to the conventions of the time.

Two of her five earliest poems are actually satirical, done in the style of witty, “mock” valentine poems with deliberately flowery and overwrought language. Two more of them reflect the more melancholy tone she would be better known for. One of those is about her brother Austin and how much she missed him, while the other, known by its first line “I have a Bird in spring,” was written for Gilbert and was a lament about the grief of fearing the loss of friendship.

A few of Dickinson’s poems were published in the Springfield Republican between 1858 and 1868; she was friends with its editor, journalist Samuel Bowles, and his wife Mary. All of those poems were published anonymously, and they were heavily edited, removing much of Dickinson’s signature stylization, syntax, and punctuation. The first poem published, "Nobody knows this little rose,” may have actually been published without Dickinson’s permission. Another poem, “Safe in their Alabaster Chambers,” was retitled and published as “The Sleeping.” By 1858, Dickinson had begun organizing her poems, even as she wrote more of them. She reviewed and made fresh copies of her poetry, putting together manuscript books. Between 1858 and 1865, she produced 40 manuscripts, comprising just under 800 poems.

During this time period, Dickinson also drafted a trio of letters which were later referred to as the “Master Letters.” They were never sent and were discovered as drafts among her papers. Addressed to an unknown man she only calls “Master,” they’re poetic in a strange way that has eluded understanding even by the most educated of scholars. They may not have even been intended for a real person at all; they remain one of the major mysteries of Dickinson’s life and writings.

Prolific Poet (1861 – 1865)

“hope” is the thing with feathers (1891).

"Hope" is the thing with feathers That perches in the soul And sings the tune without the words And never stops at all And sweetest in the Gale is heard And sore must be the storm — That could abash the little Bird That kept so many warm — I've heard it in the chillest land — And on the strangest Sea — Yet, never, in Extremity, It asked a crumb — of Me.

Dickinson’s early 30s were by far the most prolific writing period of her life. For the most part, she withdrew almost completely from society and from interactions with locals and neighbors (though she still wrote many letters), and at the same time, she began writing more and more.

Her poems from this period were, eventually, the gold standard for her creative work. She developed her unique style of writing, with unusual and specific syntax , line breaks, and punctuation. It was during this time that the themes of mortality that she was best known for began to appear in her poems more often. While her earlier works had occasionally touched on themes of grief, fear, or loss, it wasn’t until this most prolific era that she fully leaned into the themes that would define her work and her legacy.

It is estimated that Dickinson wrote more than 700 poems between 1861 and 1865. She also corresponded with literary critic Thomas Wentworth Higginson, who became one of her close friends and lifelong correspondents. Dickinson’s writing from the time seemed to embrace a little bit of melodrama, alongside deeply felt and genuine sentiments and observations.

Later work (1866 – 1870s)

Because i could not stop for death (1890).

Because I could not stop for Death— He kindly stopped for me— The Carriage held but just Ourselves— And Immortality. We slowly drove—He knew no haste, And I had put away My labor and my leisure too, For His Civility— We passed the School, where Children strove At recess—in the ring— We passed the Fields of Gazing Grain— We passed the Setting Sun— Or rather—He passed Us— The Dews drew quivering and chill— For only Gossamer, my Gown— My Tippet—only Tulle— We paused before a House that seemed A Swelling of the Ground— The Roof was scarcely visible— The Cornice—in the Ground— Since then—'tis centuries— and yet Feels shorter than the Day I first surmised the Horses' Heads Were toward Eternity—

By 1866, Dickinson’s productivity began tapering off. She had suffered personal losses, including that of her beloved dog Carlo, and her trusted household servant got married and left her household in 1866. Most estimates suggest that she wrote about one third of her body of work after 1866.

Around 1867, Dickinson’s reclusive tendencies became more and more extreme. She began refusing to see visitors, only speaking to them from the other side of a door, and rarely went out in public. On the rare occasions she did leave the house, she always wore white, gaining notoriety as “the woman in white.” Despite this avoidance of physical socialization, Dickinson was a lively correspondent; around two-thirds of her surviving correspondence was written between 1866 and her death, 20 years later.

Dickinson’s personal life during this time was complicated as well. She lost her father to a stroke in 1874, but she refused to come out of her self-imposed seclusion for his memorial or funeral services. She also may have briefly had a romantic correspondence with Otis Phillips Lord, a judge and a widower who was a longtime friend. Very little of their correspondence survives, but what does survive shows that they wrote to each other like clockwork, every Sunday, and their letters were full of literary references and quotations. Lord died in 1884, two years after Dickinson’s old mentor, Charles Wadsworth, had died after a long illness.

Literary Style and Themes

Even a cursory glance at Dickinson’s poetry reveals some of the hallmarks of her style. Dickinson embraced highly unconventional use of punctuation , capitalization, and line breaks, which she insisted were crucial to the meaning of the poems. When her early poems were edited for publication, she was seriously displeased, arguing the edits to the stylization had altered the whole meaning. Her use of meter is also somewhat unconventional, as she avoids the popular pentameter for tetrameter or trimeter, and even then is irregular in her use of meter within a poem. In other ways, however, her poems stuck to some conventions; she often used ballad stanza forms and ABCB rhyme schemes.

The themes of Dickinson’s poetry vary widely. She’s perhaps most well known for her preoccupation with mortality and death, as exemplified in one of her most famous poems, “Because I did not stop for Death.” In some cases, this also stretched to her heavily Christian themes, with poems tied into the Christian Gospels and the life of Jesus Christ. Although her poems dealing with death are sometimes quite spiritual in nature, she also has a surprisingly colorful array of descriptions of death by various, sometimes violent means.

On the other hand, Dickinson’s poetry often embraces humor and even satire and irony to make her point; she’s not the dreary figure she is often portrayed as because of her more morbid themes. Many of her poems use garden and floral imagery, reflecting her lifelong passion for meticulous gardening and often using the “ language of flowers ” to symbolize themes such as youth, prudence, or even poetry itself. The images of nature also occasionally showed up as living creatures, as in her famous poem “ Hope is the thing with feathers .”

Dickinson reportedly kept writing until nearly the end of her life, but her lack of energy showed through when she no longer edited or organized her poems. Her family life became more complicated as her brother’s marriage to her beloved Susan fell apart and Austin instead turned to a mistress, Mabel Loomis Todd, who Dickinson never met. Her mother died in 1882, and her favorite nephew in 1883.

Through 1885, her health declined, and her family grew more concerned. Dickinson became extremely ill in May of 1886 and died on May 15, 1886. Her doctor declared the cause of death to be Bright’s disease, a disease of the kidneys . Susan Gilbert was asked to prepare her body for burial and to write her obituary, which she did with great care. Dickinson was buried in her family’s plot at West Cemetery in Amherst.

The great irony of Dickinson’s life is that she was largely unknown during her lifetime. In fact, she was probably better known as a talented gardener than as a poet. Fewer than a dozen of her poems were actually published for public consumption when she was alive. It wasn’t until after her death, when her sister Lavinia discovered her manuscripts of over 1,800 poems, that her work was published in bulk. Since that first publication, in 1890, Dickinson’s poetry has never been out of print.

At first, the non-traditional style of her poetry led to her posthumous publications getting somewhat mixed receptions. At the time, her experimentation with style and form led to criticism over her skill and education, but decades later, those same qualities were praised as signifying her creativity and daring. In the 20th century, there was a resurgence of interest and scholarship in Dickinson, particularly with regards to studying her as a female poet , not separating her gender from her work as earlier critics and scholars had.

While her eccentric nature and choice of a secluded life has occupied much of Dickinson’s image in popular culture, she is still regarded as a highly respected and highly influential American poet. Her work is consistently taught in high schools and colleges, is never out of print, and has served as the inspiration for countless artists, both in poetry and in other media. Feminist artists in particular have often found inspiration in Dickinson; both her life and her impressive body of work have provided inspiration to countless creative works.

- Habegger, Alfred. My Wars Are Laid Away in Books: The Life of Emily Dickinson . New York: Random House, 2001.

- Johnson, Thomas H. (ed.). The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson . Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1960.

- Sewall, Richard B. The Life of Emily Dickinson . New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1974.

- Wolff, Cynthia Griffin. Emily Dickinson . New York. Alfred A. Knopf, 1986.

- Dickinson's 'The Wind Tapped Like a Tired Man'

- Emily Dickinson's Mother, Emily Norcross

- Best-Loved American Women Poets

- Emily Dickinson's 'If I Can Stop One Heart From Breaking'

- Biography of Emily Brontë, English Novelist

- Biography of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Poet and Activist

- Emily Dickinson Quotes

- Poems to Read on Thanksgiving Day

- Biography of Sylvia Plath, American Poet and Writer

- 42 Must-Read Feminist Female Authors

- Phillis Wheatley

- Biography of Gabriela Mistral, Chilean Poet and Nobel Prize Winner

- Early Black American Poets

- Women Poets in History

- Biography of Hilda Doolittle, Poet, Translator, and Memoirist

Emily Dickinson

By ellen gutoskey | nov 4, 2019.

AUTHORS (1830–1886); AMHERST, MASSACHUSETTS

Though almost all of Emily Dickinson’s famous poems, from the morbid “Because I Could Not Stop for Death” to the uplifting “‘Hope’ Is the Thing With Feathers,” were published after her death, she’s now considered one of the greatest American poets of the 19th century. Read on for facts, quotes, and more from Emily Dickinson’s life and career.

1. Emily Dickinson’s Poem “Because I Could Not Stop for Death” Was Published Posthumously.

Only ten of Emily Dickinson's poems were published during her lifetime—the majority of her work was edited and published after her death by her friend and mentor Thomas Wentworth Higginson, with the help of her brother’s mistress, Mabel Loomis Todd, among others. “Because I Could Not Stop For Death,” possibly Dickinson’s most famous poem , was released in the first volume, Poems , in 1890.

2. Most of Emily Dickinson’s Poems Didn’t Have Titles.

Since Emily Dickinson didn’t title her poems, her editors took the liberty of giving some of them titles before publication. “Because I Could Not Stop for Death,” for example, is sometimes called “The Chariot.” Otherwise, they’re usually referred to by the first line of the poem and/or a number that corresponds to its location in whichever collection it first appeared.

3. Emily Dickinson’s “‘Hope’ Is the Thing With Feathers” Illustrates Her Often Unconventional Use of Punctuation.

Though Dickinson’s early editors altered much of the punctuation in her poems after her death, her original manuscripts reveal just how often she used varying dashes to accentuate certain lines and phrases in her work. In “‘Hope’ Is the Thing With Feathers,” for example, dashes separate “in the Gale” in the line “And sweetest – in the Gale – is heard –” and “never” in the line “Yet – never – in Extremity.” How exactly Dickinson meant those dashes to influence rhythm and meaning is up for interpretation.

4. The Emily Dickinson Museum in Amherst, Massachusetts, Hosts an Annual 19th-Century Children’s Circus.

Though the specifics of the summer circus vary from year to year, highlights have included 19th-century activities like tightrope-walking and ring tosses, as well as poetry readings, parades, and tours through Dickinson’s home. The circus was inspired by Dickinson’s recollections of a similar circus put on by her niece and nephews.

5. Emily Dickinson’s Love Poems and Letters Imply a Mystery Man of Her Own.

The famously unmarried Dickinson wrote three “Master Letters” between 1858 and 1862 to an anonymous love interest she called only “Master,” and some of her poems—“Wild Nights,” for example—also broach the subject of passionate, romantic love. Though we’ll likely never know whom Dickinson was writing about, scholars have suggested he was a mentor, a newspaper editor, a reverend, an Amherst student, a fictional muse of her own making, or God himself.

6. Emily Dickinson’s Cause of Death Might’ve Been High Blood Pressure.

According to Emily Dickinson’s death certificate, she died of Bright’s disease, a type of kidney disease. Based on her symptoms and medicine, however, her actual cause of death could’ve been heart failure or a brain hemorrhage brought on by hypertension, or high blood pressure. She passed away in her Amherst home on May 15, 1886, aged 55.

7. Emily Dickinson’s Grandfather Founded Amherst College.

Her paternal grandfather, Samuel Dickinson, was one of the founders of Amherst College, and her father and brother each served as the institution’s treasurer. Not only does the college house the largest collection of Emily Dickinson’s work, it also owns the Emily Dickinson Museum, which includes the Homestead—Dickinson’s birthplace and home—and the neighboring property the Evergreens, where her brother’s family lived.

Famous Emily Dickinson Poems

- “Because I Could Not Stop for Death” (1863)

- “‘Hope’ Is the Thing With Feathers” (1861)

- “I’m Nobody! Who Are You?” (1861)

- “Wild Nights – Wild Nights!” (1861)

- “Success Is Counted Sweetest” (1859)

- “I Felt a Funeral, in My Brain” (1861)

- “This Is My Letter to the World” (1862)

- “I Dwell in Possibility” (1862)

- “It Was Not Death, for I Stood Up” (1862)

- “I Taste a Liquor Never Brewed” (1861)

Famous Emily Dickinson Quotes

- “If I can stop one heart from breaking/I shall not live in vain.”

- “Hope is the thing with feathers/That perches in the soul/And sings the tune without the words/And never stops at all.”

- “Forever – is composed of Nows –.”

- “The Brain – is wider than the Sky –.”

- “I’m Nobody! Who are you?/Are you – Nobody – too?”

- “The soul should always stand ajar.”

- “Were I with thee/Wild nights should be/Our luxury!”

Emily Dickinson and Reading

“i am glad there are books. they are better than heaven, for that is unavoidable, while one may miss these.” – emily dickinson to f. b. sanborn, about 1873 (l402).

In childhood, aside from her schoolbooks, she read the Bible, and was given carefully chosen, principally moralistic, Sabbath School stories by her parents and relatives. Sometime later, a young man studying in her father’s law office slipped one of Lydia Maria Child’s historical novels into the Dickinson children’s hands. “This then is a book! And there are more of them,” was her ecstatic response (L342b). Her youth was the hey-day of the Romantic literary era, with Washington Irving and Sir Walter Scott, Byron and Wordsworth, Longfellow and Tennyson at the height of popularity, not to mention the novels of Dickens and a host of minor novelists whose now forgotten titles provided popular girlhood reading. In 1848 the novels of the Brontës launched a new era of psychological fiction, much of it by women, which captured Dickinson’s sensibilities, and initiated her particular love, in turn, for the works of poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning and novelist George Eliot.

In her early twenties, discussing books was Dickinson’s stock in trade with the Amherst students and tutors who were her friends and among whom circulated books by Thomas De Quincey, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Thomas Carlyle, and German novelist Jean Paul Richter. Dickinson belonged to a reading group of Amherst young people who tackled reading Shakespeare aloud, and she was introduced to Emerson’s work by his first book of poems, a gift from her early mentor Benjamin Franklin Newton. Friendships of early adulthood, such as that with Amherst student Henry Vaughn Emmons, enlarged her awareness of and access to books beyond her own home shelves. While her father might prefer “lonely & rigorous books” (L342a) and spurn the authors his eldest daughter preferred as “modern Literati” (L113), he seems always to have purchased any books she asked for.

In addition, Dickinson kept up with current events through the daily reading of The Springfield Republican , perhaps New England’s best political and literary newspaper. She read every issue of sister-in-law Susan Dickinson ’s subscription to The Atlantic Monthly , in addition to perusing a range of other periodicals that came to the Homestead, so that her gradual reclusiveness in no way interfered with knowing what was going on in the world, particularly the world of books.

Of all the literature that Dickinson devoured, the one book to which she returned again and again was the King James Bible. She read and reread it, often quoting it from memory. Its stories and personages made frequent appearances in her letters and poems, sometimes through the deftest of references. She once told a friend that all literature might be sifted to the Bible and Shakespeare.

A vital ally in the poet’s love of books, Susan Dickinson was an astonishing book acquirer for her time and equally enamored of the Brownings, Tennyson, Ruskin, and other Romantics. Sue had a taste for religious philosophers, such as Francis Quarles and Thomas à Kempis, books that became essential to the poet as well. Susan and Emily shared Sue’s library; their markings of favorite passages with light pencil strokes provides a guide to the books and authorial insights that interested them most.

Today the libraries of the Dickinson houses are in the possession of two major universities. Many books from the Homestead are in the Houghton Library at Harvard, and the majority of those from The Evergreens are in the John Hay Library at Brown. The Museum has begun a program, called “ Replenishing the Shelves ,” to replace the hundreds of nineteenth-century titles that once occupied the family bookcases and were important to the poet and her family members.

Further reading:

Capps, Jack. Emily Dickinson’s Reading 1836-1886 . Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1966.

Sewall, Richard B. The Life of Emily Dickinson . New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1974. See especially Chapter 28, “Books and Reading,” 668-705.

Heginbotham, Eleanor. “‘What Are You Reading Now?’: Emily Dickinson’s Epistolary Book Club.” Reading Emily Dickinson’s Letters: Critical Essays . Eds. Eberwein, Jane Donahue, Cindy MacKenzie and Marietta Messmer. Amherst, MA: U of Massachusetts P, 2009. xiii, 293 pp. Print.

Deppman, Jed. “Through the Dark Sod: Trying to Read with Emily Dickinson.” In Trying to Think with Emily Dickinson , 150-83. University of Massachusetts Press, 2008. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5vk41f.10 .

Finnerty, Páraic. ““Shakespeare Always and Forever”: Dickinson’s Circulation of the Bard.” In Emily Dickinson’s Shakespeare , 117-39. University of Massachusetts Press, 2006. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5vk963.10 .

Miller, Cristanne. Reading in Time : Emily Dickinson in the Nineteenth Century . Amherst : University of Massachusetts Press, 2012.

Biography Online

Biography Emily Dickinson

Emily Dickinson, regarded as one of America’s greatest poets, is also well known for her unusual life of self-imposed social seclusion. Living a life of simplicity and seclusion, she yet wrote poetry of great power; questioning the nature of immortality and death, with at times an almost mantric quality. Her different lifestyle created an aura; often romanticised, and frequently a source of interest and speculation. But ultimately Emily Dickinson is remembered for her unique poetry. Within short, compact phrases she expressed far-reaching ideas; amidst paradox and uncertainty, her poetry has an undeniable capacity to move and provoke.

Early Life Emily Dickinson

Emily Dickinson was born on 10th December 1830, in the town of Amherst, Massachusetts. Amherst, 50 miles from Boston, had become well known as a centre for Education, based around Amherst College. Her family were pillars of the local community; their house known as “The Homestead” or “Mansion” was often used as a meeting place for distinguished visitors including, Ralph Waldo Emerson. (although it unlikely he met with Emily Dickinson)

Religious Influence on the Poetry of Emily Dickinson

A crucial issue at the time was the issue of religion, which to Emily was the “all important question” The antecedents of the Dickinson’s can be traced back to the early Puritan settlers, who left Lincolnshire in the late 17th Century. Her antecedents had left England so that they could practise religious freedom in America. In the nineteenth- century, religion was still the dominant issue of the day. The East coast, in particular, saw a revival of strict Calvinism; developing partly in response to the more inclusive Unitarianism. Amherst College itself was founded with the intention of training ministers to spread the Christian word. Calvinism. By incrimination, Emily Dickinson would probably have been more at ease with the looser and more inclusive ideology of Unitarianism. However, the “Great Revival” as it was known, pushed the Calvinist view to greatest prominence.

Religious Belief – Emily Dickinson