352 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 2012

About the author

Ratings & Reviews

What do you think? Rate this book Write a Review

Friends & Following

Community reviews.

Join the discussion

Can't find what you're looking for.

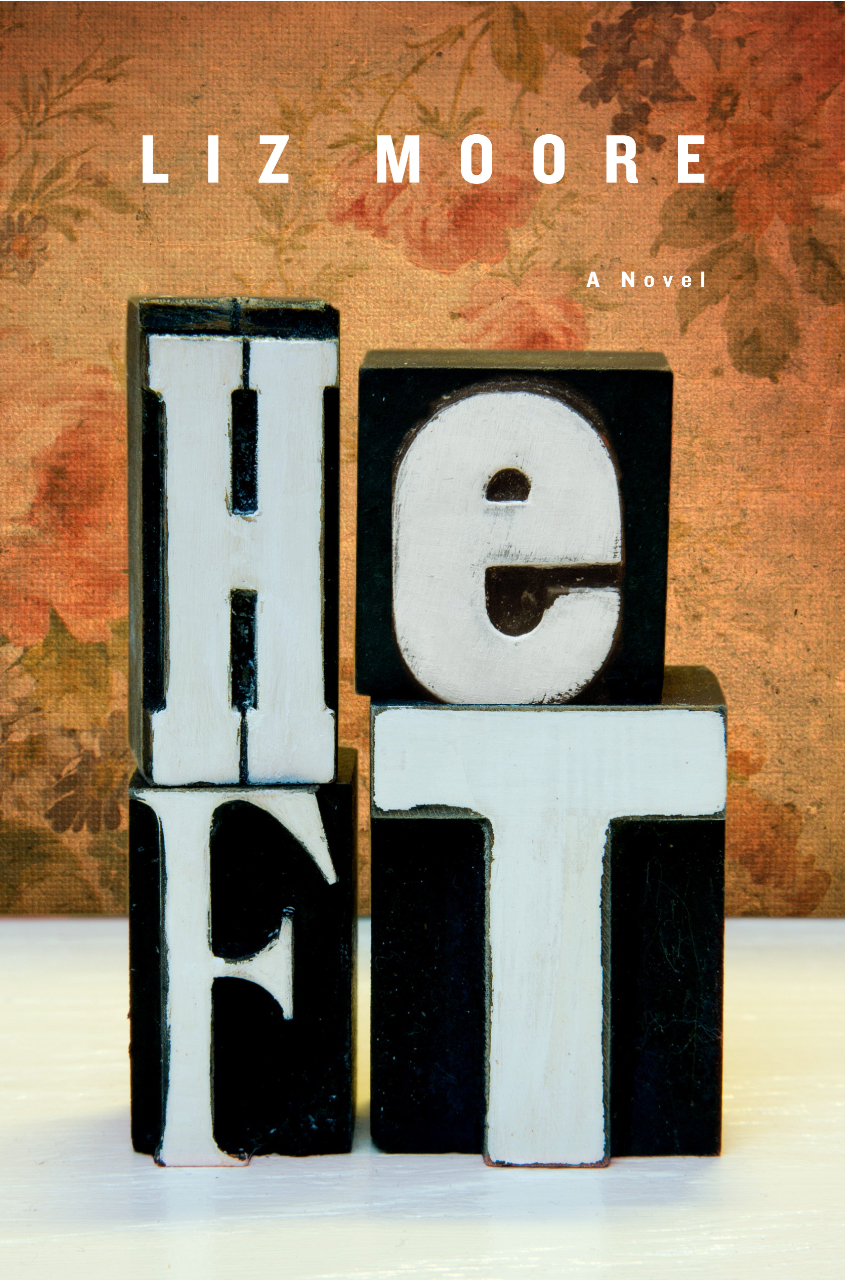

Former academic Arthur Opp weighs 550 pounds and hasn't left his rambling Brooklyn home in a decade. Twenty miles away, in Yonkers, seventeen-year-old Kel Keller navigates life as the poor kid in a rich school and pins his hopes on what seems like a promising baseball career - if he can untangle himself from his family drama. The link between this unlikely pair is Kel's mother, Charlene, a former student of Arthur's. After nearly two decades of silence, it is Charlene's unexpected phone call to Arthur - a plea for help - that jostles them into action. Through Arthur and Kel's own quirky and lovable voices, Heft tells the winning story of two improbable heroes whose sudden connection transforms both their lives. Like Elizabeth McCracken's The Giant's House, Heft is a novel about love and family found in the most unexpected places.

BUY THE BOOK

PRAISE FOR HEFT

"Moore's characters are lovingly drawn . . . A truly original voice." THE NEW YORKER

"Heft is a work that radiantly combines compassion and a clear eyed vision. This is a novel of rare originality and sophistication." MARY GORDON

"A suspenseful, restorative novel from one of our fine young voices." COLUM MCCAM "Beautiful . . . Stunningly sad and heroically hopeful." O, THE OPRAH MAGAZINE "Heft achieves real poignancy . . . the warmth, the humanity and the hope in this novel make it compelling and pleasurable." THE WASHINGTON POST "Few novelists of recent memory have put our bleak isolation into words as clearly as Liz Moore does in her new novel." THE SAN FRANSISCO CHRONICLE

"Moore's writing is clear, persuasive, and totally engaging, bringing her characters to life in all their sweet, quirky glory . . . Heft is about transformation and about accepting that the agent of change can come from the most unlikely source." THE BOSTON GLOBE

"Tender, thoughtful." THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW

"Like its characters' hearts, Heft is full of grace. It's a beautifully written and very moving novel." THE IRISH TIMES

"This is the real deal, Liz Moore is the real deal-she's written a novel that will stick with you long after you've finished it." RUSSELL BANKS

"Moore's lovely novel (after The Words of Every Song) is about overcoming shame and loneliness and learning to connect. It is life-affirming, but never sappy." LIBRARY JOURNAL "An insightful pageturner." PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

- ADMIN AREA MY BOOKSHELF MY DASHBOARD MY PROFILE SIGN OUT SIGN IN

by Liz Moore ‧ RELEASE DATE: Feb. 1, 2012

Only a hardhearted reader will remain immune to Kel’s troubled charm.

In musician/novelist Moore’s bifurcated second novel ( The Words of Every Song, 2007), the two first-person narrations—from a housebound, grossly overweight former literature professor and a teenager in crisis over his future—never converge although they eventually intersect.

Weighing in at over 500 pounds, Arthur Opp is approaching 60, alone and lonely in the Brooklyn house he hasn’t left for years. Since his only friend has died, he avoids facing the world outside his front door; all his material needs are delivered. He spends his days eating. Then he receives a letter from a former student. When Charlene Turner took Arthur’s class 20 years ago, she was intellectually out of her depth. Yet Arthur recognized a kindred spirit. After one semester she dropped out and he never saw her again; soon after, partly due to unfounded suspicions about their relationship, his own career disintegrated. Now Charlene makes a vague request that Arthur tutor her son. Anticipating her visit, Arthur hires a maid, Yolanda, a pregnant high-school dropout who brings unexpected life and energy into his home. But although the title refers to Arthur’s quirky, larger-than-life charm, readers will find his story expendable compared to the struggles faced by single mom Charlene’s son Kel. Kel’s narrative, full of male adolescent swagger and uncertainty, is heart-wrenching. Charlene’s desperate attempts to give him the chances she missed cause Kel to struggle with deeply divided loyalties as he commutes from his working-class Yonkers neighborhood to a prestigious Westchester high school where Charlene used to work as secretary. Handsome and athletic, Kel is beloved by his friends and teachers, who have bent rules to keep Kel enrolled ever since Charlene quit (or was fired) several years ago. Now a senior, Kel is tempted by a professional baseball scout, while Charlene drinks away her days to dull the pain of lupus and concocts her wild scheme, doing whatever it takes to get Kel to attend college.

Pub Date: Feb. 1, 2012

ISBN: 978-0-393-08150-3

Page Count: 384

Publisher: Norton

Review Posted Online: Nov. 2, 2011

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Nov. 15, 2011

LITERARY FICTION | FAMILY LIFE & FRIENDSHIP

Share your opinion of this book

More by Liz Moore

BOOK REVIEW

by Liz Moore

THE MOST FUN WE EVER HAD

by Claire Lombardo ‧ RELEASE DATE: June 25, 2019

Characters flip between bottomless self-regard and pitiless self-loathing while, as late as the second-to-last chapter, yet...

Four Chicago sisters anchor a sharp, sly family story of feminine guile and guilt.

Newcomer Lombardo brews all seven deadly sins into a fun and brimming tale of an unapologetically bougie couple and their unruly daughters. In the opening scene, Liza Sorenson, daughter No. 3, flirts with a groomsman at her sister’s wedding. “There’s four of you?” he asked. “What’s that like?” Her retort: “It’s a vast hormonal hellscape. A marathon of instability and hair products.” Thus begins a story bristling with a particular kind of female intel. When Wendy, the oldest, sets her sights on a mate, she “made sure she left her mark throughout his house—soy milk in the fridge, box of tampons under the sink, surreptitious spritzes of her Bulgari musk on the sheets.” Turbulent Wendy is the novel’s best character, exuding a delectable bratty-ness. The parents—Marilyn, all pluck and busy optimism, and David, a genial family doctor—strike their offspring as impossibly happy. Lombardo levels this vision by interspersing chapters of the Sorenson parents’ early lean times with chapters about their daughters’ wobbly forays into adulthood. The central story unfurls over a single event-choked year, begun by Wendy, who unlatches a closed adoption and springs on her family the boy her stuffy married sister, Violet, gave away 15 years earlier. (The sisters improbably kept David and Marilyn clueless with a phony study-abroad scheme.) Into this churn, Lombardo adds cancer, infidelity, a heart attack, another unplanned pregnancy, a stillbirth, and an office crush for David. Meanwhile, youngest daughter Grace perpetrates a whopper, and “every day the lie was growing like mold, furring her judgment.” The writing here is silky, if occasionally overwrought. Still, the deft touches—a neighborhood fundraiser for a Little Free Library, a Twilight character as erotic touchstone—delight. The class calibrations are divine even as the utter apolitical whiteness of the Sorenson world becomes hard to fathom.

Pub Date: June 25, 2019

ISBN: 978-0-385-54425-2

Page Count: 544

Publisher: Doubleday

Review Posted Online: March 3, 2019

Kirkus Reviews Issue: March 15, 2019

More About This Book

SEEN & HEARD

THEN SHE WAS GONE

by Lisa Jewell ‧ RELEASE DATE: April 24, 2018

Dark and unsettling, this novel’s end arrives abruptly even as readers are still moving at a breakneck speed.

Ten years after her teenage daughter went missing, a mother begins a new relationship only to discover she can't truly move on until she answers lingering questions about the past.

Laurel Mack’s life stopped in many ways the day her 15-year-old daughter, Ellie, left the house to study at the library and never returned. She drifted away from her other two children, Hanna and Jake, and eventually she and her husband, Paul, divorced. Ten years later, Ellie’s remains and her backpack are found, though the police are unable to determine the reasons for her disappearance and death. After Ellie’s funeral, Laurel begins a relationship with Floyd, a man she meets in a cafe. She's disarmed by Floyd’s charm, but when she meets his young daughter, Poppy, Laurel is startled by her resemblance to Ellie. As the novel progresses, Laurel becomes increasingly determined to learn what happened to Ellie, especially after discovering an odd connection between Poppy’s mother and her daughter even as her relationship with Floyd is becoming more serious. Jewell’s ( I Found You , 2017, etc.) latest thriller moves at a brisk pace even as she plays with narrative structure: The book is split into three sections, including a first one which alternates chapters between the time of Ellie’s disappearance and the present and a second section that begins as Laurel and Floyd meet. Both of these sections primarily focus on Laurel. In the third section, Jewell alternates narrators and moments in time: The narrator switches to alternating first-person points of view (told by Poppy’s mother and Floyd) interspersed with third-person narration of Ellie’s experiences and Laurel’s discoveries in the present. All of these devices serve to build palpable tension, but the structure also contributes to how deeply disturbing the story becomes. At times, the characters and the emotional core of the events are almost obscured by such quick maneuvering through the weighty plot.

Pub Date: April 24, 2018

ISBN: 978-1-5011-5464-5

Page Count: 368

Publisher: Atria

Review Posted Online: Feb. 5, 2018

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Feb. 15, 2018

GENERAL THRILLER & SUSPENSE | SUSPENSE | FAMILY LIFE & FRIENDSHIP | SUSPENSE

More by Lisa Jewell

by Lisa Jewell

- Discover Books Fiction Thriller & Suspense Mystery & Detective Romance Science Fiction & Fantasy Nonfiction Biography & Memoir Teens & Young Adult Children's

- News & Features Bestsellers Book Lists Profiles Perspectives Awards Seen & Heard Book to Screen Kirkus TV videos In the News

- Kirkus Prize Winners & Finalists About the Kirkus Prize Kirkus Prize Judges

- Magazine Current Issue All Issues Manage My Subscription Subscribe

- Writers’ Center Hire a Professional Book Editor Get Your Book Reviewed Advertise Your Book Launch a Pro Connect Author Page Learn About The Book Industry

- More Kirkus Diversity Collections Kirkus Pro Connect My Account/Login

- About Kirkus History Our Team Contest FAQ Press Center Info For Publishers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Reprints, Permission & Excerpting Policy

© Copyright 2024 Kirkus Media LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Popular in this Genre

Hey there, book lover.

We’re glad you found a book that interests you!

Please select an existing bookshelf

Create a new bookshelf.

We can’t wait for you to join Kirkus!

Please sign up to continue.

It’s free and takes less than 10 seconds!

Already have an account? Log in.

Trouble signing in? Retrieve credentials.

Almost there!

- Industry Professional

Welcome Back!

Sign in using your Kirkus account

Contact us: 1-800-316-9361 or email [email protected].

Don’t fret. We’ll find you.

Magazine Subscribers ( How to Find Your Reader Number )

If You’ve Purchased Author Services

Don’t have an account yet? Sign Up.

The Book Report Network

- Bookreporter

- ReadingGroupGuides

- AuthorsOnTheWeb

Sign up for our newsletters!

Find a Guide

For book groups, what's your book group reading this month, favorite monthly lists & picks, most requested guides of 2023, when no discussion guide available, starting a reading group, running a book group, choosing what to read, tips for book clubs, books about reading groups, coming soon, new in paperback, write to us, frequently asked questions.

- Request a Guide

Advertise with Us

Add your guide, you are here:.

- About the Book

Former academic Arthur Opp weighs 550 pounds and hasn't left his rambling Brooklyn home in a decade. Twenty miles away, in Yonkers, 17-year-old Kel Keller navigates life as the poor kid in a rich school and pins his hopes on what seems like a promising baseball career --- if he can untangle himself from his family drama. The link between this unlikely pair is Kel’s mother, Charlene, a former student of Arthur’s. After nearly two decades of silence, it is Charlene’s unexpected phone call to Arthur --- a plea for help --- that jostles them into action.

Through Arthur and Kel’s own quirky and lovable voices, HEFT tells the winning story of two improbable heroes whose sudden connection transforms both their lives. Like Elizabeth McCracken’s THE GIANT'S HOUSE, HEFT is a novel about love and family found in the most unexpected places.

Heft by Liz Moore

- Publication Date: January 23, 2012

- Genres: Family Life , Fiction

- Hardcover: 352 pages

- Publisher: W. W. Norton & Company

- ISBN-10: 0393081508

- ISBN-13: 9780393081503

- How to Add a Guide

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Newsletters

Copyright © 2024 The Book Report, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

- Bookreporter

- ReadingGroupGuides

- AuthorsOnTheWeb

The Book Report Network

Sign up for our newsletters!

Regular Features

Author spotlights, "bookreporter talks to" videos & podcasts, "bookaccino live: a lively talk about books", favorite monthly lists & picks, seasonal features, book festivals, sports features, bookshelves.

- Coming Soon

Newsletters

- Weekly Update

- On Sale This Week

- Spring Preview

- Winter Reading

- Holiday Cheer

- Fall Preview

- Summer Reading

Word of Mouth

Submitting a book for review, write the editor, you are here:.

Arthur Opp was once a plump college professor, but now he is a lonely recluse who weighs over 500 pounds. He has secreted himself away in his family's once fine Brooklyn home. The house, like Arthur, has seen better days. Arthur no longer leaves his house. He buys necessities and luxuries via his phone or online. Every day, a delivery person leaves something for him; delivery people are literally the only people he ever speaks to face to face. He keeps up a little charade with customer service folks, hinting that he has a busy life that leaves him no time to go out and shop for his needs. Arthur's mother is deceased, and he is estranged from his father and half-brother. His best friend has also died, leaving him friendless, except for one person.

"HEFT is both a lyrically written tale and an engrossing page-turner.... Although not a light read, this tender tale is ultimately hopeful and unforgettable."

Nearly 20 years ago, Arthur had a tentative, not-quite-romantic connection with a beguiling young woman who had been one of his students. Although he hasn't seen Charlene Turner in those two decades, they have developed a pen pal relationship. Although Charlene has not responded to Arthur's letter in a year, she suddenly calls him. Hearing the phone ring shocks Arthur, and he is so delighted when he hears Charlene's voice that he has to clap his hand over his mouth in order to squelch a cry of joy. Arthur has always imagined that they would meet one day and resume their relationship. Now, on the phone, he finds himself continuing the lies he relays to her in his correspondence, elaborating on trips he has never taken, visits with people he has no relationship with, and hobbies he's never had, making it sound like he lives a full life instead of his empty existence.

When Arthur lets it slip that he no longer teaches, Charlene says, "Oh, no," so he obligingly tells her that he tutors instead, although that is yet another falsehood. Charlene becomes enthused at this news and says she's sending him a letter, and that he must watch for it. Before he can ask what the letter will contain, she has hung up, leaving him to contemplate the way she sounded --- rather strange, remote, filled with regret, and slow. In fact, he can't help wondering if Charlene was drunk, even though it is only two in the afternoon.

Arthur pulls out his cherished packet containing every letter Charlene has written to him, allowing himself the rare luxury of reading every word. Then he writes her a long letter, telling her the truth about his life, an impassioned unveiling of all the secrets that have weighed upon him for these many years. He lays bare the facts about his obesity, his lies about having friends, and the fact that he hasn't been out of his house since September 11, 2001, when he forced himself to walk a few blocks to prove to himself that the world was still there beyond his front stoop. Then, berating himself as a coward, he can't bring himself to mail this intimate letter.

Charlene's phone call unleashes a strong yearning in Arthur. He remembers their friendship in great detail. Days later, when the envelope arrives from her, he is mystified by the contents. There is no letter. Instead there is a small photograph of a teenage boy holding a baseball bat. On the back, Charlene has written "My Son Kel." How can this be? If Charlene has a son, she certainly hasn't told Arthur about him. And what does it mean, that she should send him this boy's picture?

HEFT is both a lyrically written tale and an engrossing page-turner. In Arthur Opp, author Liz Moore gives us a complete, three-dimensional person rather than the media's stereotypical obese recluse; Arthur is quite heartbreakingly real, as is young Kel Keller, who we also grow to know. Their stories, simply told without soap opera-ish flourishes, tug at a reader's emotions. Although not a light read, this tender tale is ultimately hopeful and unforgettable.

Reviewed by Terry Miller Shannon on February 2, 2012

Heft by Liz Moore

- Publication Date: January 23, 2012

- Genres: Family Life , Fiction

- Hardcover: 352 pages

- Publisher: W. W. Norton & Company

- ISBN-10: 0393081508

- ISBN-13: 9780393081503

Find a Book

View all » | By Author » | By Genre » | By Date »

- bookreporter.com on Facebook

- bookreporter.com on Twitter

- thebookreportnetwork on Instagram

Copyright © 2024 The Book Report, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

- Become a Reviewer

- Meet the Reviewers

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Getting Started

- Start a Book Club

- Book Club Ideas/Help▼

- Our Featured Clubs ▼

- Popular Books

- Book Reviews

- Reading Guides

- Blog Home ▼

- Find a Recipe

- About LitCourse

- Course Catalog

Heft (Moore)

Heft Liz Moore, 2012 W.W. Norton & Co. 352 pp. ISBN-13: 9780091944209 Summary Former academic Arthur Opp weighs 550 pounds and hasn't left his rambling Brooklyn home in a decade. Twenty miles away, in Yonkers, seventeen-year-old Kel Keller navigates life as the poor kid in a rich school and pins his hopes on what seems like a promising baseball career—if he can untangle himself from his family drama. The link between this unlikely pair is Kel’s mother, Charlene, a former student of Arthur’s. After nearly two decades of silence, it is Charlene’s unexpected phone call to Arthur—a plea for help—that jostles them into action. Through Arthur and Kel’s own quirky and lovable voices, Heft tells the winning story of two improbable heroes whose sudden connection transforms both their lives. Heft is a novel about love and family found in the most unexpected places. ( From the publisher .)

- Next >>

LitLovers © 2024

- Australia edition

- International edition

- Europe edition

New Cold Wars review: China, Russia and Biden’s daunting task

David Sanger of the New York Times delivers a must-read on the foreign policy challenges now facing US leaders

R ussia bombards Ukraine. Israel and Hamas are locked in a danse macabre. The threat of outright war between Jerusalem and Tehran grows daily. Beijing and Washington snarl. In a moment like this, David Sanger’s latest book, subtitled China’s Rise, Russia’s Invasion, and America’s Struggle to Defend the West , is a must-read. Painstakingly researched, New Cold Wars brims with on-record interviews and observations by thinly veiled sources.

Officials closest to the president talk with an eye on posterity. The words of the CIA director, Bill Burns, repeatedly appear on the page. Antony Blinken, the secretary of state, and Jake Sullivan, the national security adviser, surface throughout the book. Sanger, White House and national security correspondent for the New York Times, fuses access, authority and curiosity to deliver an alarming message: US dominance is no longer axiomatic.

In the third decade of the 21st century, China and Russia defy Washington, endeavoring to shatter the status quo while reaching for past glories. Vladimir Putin sees himself as the second coming of Peter the Great, “a dictator … consumed by restoring the old Russian empire and addressing old grievances”, in Sanger’s words.

The possibility of nuclear war is no longer purely theoretical. “In 2021 Biden, [Gen Mark] Milley, and the new White House national security team discovered that America’s nuclear holiday was over,” Sanger writes. “They were plunging into a new era that was far more complicated than the cold war had ever been.”

As Russia’s war on Ukraine faltered, Putin and the Kremlin raised the specter of nuclear deployment against Kyiv.

“The threat that Russia might use a nuclear weapon against its non-nuclear-armed foe surfaced and resurfaced every few months,” Sanger recalls.

The world was no longer “flat”. Rather, “the other side began to look more like a security threat and less like a lucrative market”. Unfettered free trade and interdependence had yielded prosperity and growth for some but birthed anger and displacement among many. Nafta – the North American Free Trade Agreement – became a figurative four-letter word. In the US, counties that lost jobs to China and Mexico went for Trump in 2016 .

Biden and the Democrats realized China never was and never would be America’s friend. “‘I think it’s fair to say that just about every assumption across different administrations was wrong,” one of Biden’s “closest advisers” tells Sanger.

“‘The internet would bring political liberty. Trade would liberalize the regime’ while creating high-skill jobs for Americans. The list went on. A lot of it was just wishful thinking.”

Sanger also captures the despondency that surrounded the botched US withdrawal from Afghanistan. A suicide bombing at the Kabul airport left 13 US soldiers and 170 civilians dead. The event still haunts.

“The president came into the room shortly thereafter, and at that point Gen [Kenneth] McKenzie informed him of the attack and also the fact that there had been at least several American military casualties, fatalities in the attack,” Burns recalls. “I remember the president just paused for at least 30 seconds or so and put his head down because he was absorbing the sadness of the moment and the sense of loss as well.”

Almost three years later, Biden’s political standing has not recovered. “The bitter American experience in Afghanistan and Iraq seemed to underscore the dangers of imperial overreach,” Sanger writes. With Iran on the front burner and the Middle East mired in turmoil, what comes next is unclear.

A coda: a recent supplemental review conducted by the Pentagon determined that a sole Isis member carried out the Kabul bombing. The review also found that the attack was tactically unpreventable.

Sanger also summarizes a tense exchange between Biden and Benjamin Netanyahu, prime minister of Israel , over the Gaza war.

“Hadn’t the US firebombed Tokyo during world war two? Netanyahu demanded. “Hadn’t it unleashed two atom bombs? What about the thousands who died in Mosul, as the US sought to wipe out Isis?”

On Thursday, the US vetoed a resolution to confer full UN membership on the “State of Palestine”. Hours later, Standard & Poor’s downgraded Israel’s credit rating and Israel retaliated against Iran.

N ew Cold Wars does contain lighter notes. For example, Sanger catches Donald Trump whining to Randall Stephenson, then CEO of AT&T , about his (self-inflicted) problems with women. The 45th president invited Stephenson to the Oval Office, to discuss China and telecommunications. Things did not quite work out that way.

“Trump burned up the first 45 minutes of the meeting by riffing on how men got into trouble,” Sanger writes. “It was all about women. Then he went into a long diatribe about Stormy Daniels.”

Stephenson later recalled: “It was ‘all part of the same stand-up comedy act’ … and ‘we were left with 15 minutes to talk about Chinese infrastructure’.”

Trump wasn’t interested. Stephenson “could see that the president’s mind was elsewhere. ‘This is really boring,’ Trump finally said.”

On Thursday, in Trump’s hush-money case in New York, the parties picked a jury. Daniels is slated to be a prosecution witness.

Sanger ends his book on a note of nostalgia – and trepidation.

“For all the present risks, it is worth remembering that one of the most remarkable and little-discussed accomplishments of the old cold war was that the great powers never escalated their differences into a direct conflict. That is an eight-decade-long streak we cannot afford to break.”

New Cold Wars is published in the US by Penguin Random House

- Politics books

- US foreign policy

- US national security

- US military

- Biden administration

Most viewed

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

5 Strategies for Improving Mental Health at Work

- Morra Aarons-Mele

Benefits and conversations around mental health evolved during the pandemic. Workplace cultures are starting to catch up.

Companies are investing in — and talking about — mental health more often these days. But employees aren’t reporting a corresponding rise in well-being. Why? The author, who wrote a book on mental health and work last year, explores several key ways organizations haven’t gone far enough in implementing a culture of well-being. She also makes five key suggestions on what they can do to improve the mental health of their employees.

“I have never felt so seen.”

- Morra Aarons-Mele is a workplace mental health consultant and author of The Anxious Achiever: Turn Your Biggest Fears Into Your Leadership Superpower (Harvard Business Review Press, 2023). She has written for The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, O the Oprah Magazine, TED, among others, and is the host of the Anxious Achiever podcast from LinkedIn Presents. morraam

Partner Center

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Taylor Swift's 'Tortured Poets' is written in blood

On Taylor Swift's 11th album, The Tortured Poets Department , her artistry is tangled up in the details of her private life and her deployment of celebrity. But Swift's lack of concern about whether these songs speak to and for anyone but herself is audible throughout the album. Beth Garrabrant /Courtesy of the artist hide caption

On Taylor Swift's 11th album, The Tortured Poets Department , her artistry is tangled up in the details of her private life and her deployment of celebrity. But Swift's lack of concern about whether these songs speak to and for anyone but herself is audible throughout the album.

For all of its fetishization of new sounds and stances, pop music was born and still thrives by asking fundamental questions. For example, what do you do with a broken heart? That's an awfully familiar one. Yet romantic failure does feel different every time. Its isolating sting produces a kind of obliterating possessiveness: my pain, my broken delusions, my hope for healing. A broken heart is a screaming baby demanding to be held and coddled and nurtured until it grows up and learns how to function properly. This is as true in the era of the one-percent glitz goddess as it was when blues queens and torch singers organized society's crying sessions. It's true of Taylor Swift , who's equated songwriting with the heart's recovery since she released " Teardrops on my Guitar " 18 years ago, and whose 11th album, The Tortured Poets Department , is as messy and confrontational as a good girl's work can get, blood on her pages in a classic shade of red.

Taylor Swift, Beyoncé and 50 more albums coming out this spring

Turning the Tables

Taylor swift is the 21st century's most disorienting pop star.

Back in her Lemonade days, when her broken heart turned her into a bearer of revolutionary spirit, Swift's counterpart and friendly rival, Beyoncé , got practical, advising her listeners that while feelings do need tending, a secured bank account is what counts. "Your best revenge is your paper," she sang .

For Swift, the best revenge is her pen. One of the first Tortured Poets songs revealed back in February (one of the album's many bonus tracks, it turns out, but a crucial framing device) is called " The Manuscript "; in it, a woman re-reads her own scripted account of a "torrid love affair." Screenwriting is one of a few literary ambitions Swift aligns with this project. At The Grove mall in Los Angeles, Swift partnered with Spotify to create a mini-library where new lyrics were inscribed in weathered books and on sheets of parchment in the days leading up to its release. The scene was a fans' photo op invoking high art and even scripture. In the photographs of the installation that I saw, every bound volume in the library bears Swift's name. The message is clear: When Taylor Swift makes music, she authors everything around her.

For years, Swift has been pop's leading writer of autofiction , her work exploring new dimensions of confessional songwriting, making it the foundation of a highly mediated public-private life. The standard line about her teasing lyrical disclosures (and it's correct on one level) is that they're all about fueling fan interest. But on Tortured Poets , she taps into a much more established and respected tradition. Using autobiography as a sword of justice is a move as ancient as the women saints who smote abusive fathers and priests in the name of an early Christian Jesus; in our own time, just among women, it's been made by confessional poets like Sylvia Plath, memoirists from Maya Angelou to Joyce Maynard and literary stars like the Nobel prize winner Annie Ernaux. And, of course, Swift's reluctant spiritual mother, Joni Mitchell .

Even in today's blather-saturated cultural environment, a woman speaking out after silence can feel revolutionary; that this is an honorable act is a fundamental principle within many writers' circles. "I write out of hurt and how to make hurt okay, how to make myself strong and come home, and it may be the only home I ever have," Natalie Goldberg declares in Writing Down the Bones , the most popular writing manual of the 20th century. When on this album's title track, Swift sings, "I think some things I never say," she's making an offhand joke; but this is the album where she does say all the things she thinks, about love at least, going deeper into the personal zone that is her métier than ever before. Sharing her darkest impulses and most mortifying delusions, she fills in the blank spaces in the story of several much-mediated affairs and declares this an act of liberation that has changed and ultimately strengthened her. She spares no one, including herself; often in these songs, she considers her naiveté and wishfulness through a grown woman's lens and admits she's made a fool of herself. But she owns her heartbreak now. She alone will have the last word on its shape and its effects.

This includes other people's sides of her stories. The songs on Tortured Poets , most of which are mid- or up-tempo ballads spun out in the gossamer style that's defined Swift's confessional mode since Folklore , build a closed universe of private and even stolen moments, inhabited by only two people: Swift and a man. With a few illuminating exceptions that stray from the album's plot, she rarely looks beyond their interactions. The point is not to observe the world, but to disclose the details of one sometimes-shared life, to lay bare what others haven't seen. Tortured Poets is the culmination of a catalog full of songs in which Swift has taken us into the bedrooms where men pleasured or misled her, the bars where they charmed her, the empty playgrounds where they sat on swings with her and promised something they couldn't give. When she sings repeatedly that one of the most suspect characters on the album told her she was the love of her life, she's sharing something nobody else heard. That's the point. She's testifying under her own oath.

Swift's musical approach has always been enthusiastic and absorbent. She's created her own sounds by blending country's sturdy song structures with R&B's vibes, rap's cadences and pop's glitz; as a personality and a performer, she's all arms, hugging the world. The sound of Tortured Poets offers that familiar embrace, with pop tracks that sparkle with intelligence, and meditative ones that wrap tons of comforting aura around Swift's ruminations. Beyond a virtually undetectable Post Malone appearance and a Florence Welch duet that also serves as an homage to Swift's current exemplar/best friendly rival, Lana Del Rey , the album alternates between co-writes with Jack Antonoff and Aaron Dessner, the producers who have helped Swift find her mature sound, which blends all of her previous approaches without favoring any prevailing trend. There are the rap-like, conversational verses, the reaching choruses, the delicate piano meditations, the swooning synth beats. Antonoff's songs come closest to her post- 1989 chart toppers; Dessner's fulfill her plans to remain an album artist. Swift has also written two songs on her own, a rarity for her; both come as close to ferocity as she gets. As a sustained listen, Tortured Poets harkens back to high points throughout Swift's career, creating a comforting environment that both supports and balances the intensity of her storytelling.

It's with her pen that Swift executes her battle plans. As always, especially when she dwells on the work and play of emotional intimacy, her lyrics are hyper-focused, spilling over with detail, editing the mess of desire, projection, communion and pain that constitutes romance into one sharp perspective: her own. She renders this view so intensely that it goes beyond confession and becomes a form of writing that can't be disputed. Remember that parchment and her quill pen; her songs are her new testaments. It's a power play, but for many fans, especially women, this ambition to be definitive feels like a necessary corrective to the misrepresentations or silence they face from ill-intentioned or cluelessly entitled men.

"A great writer can be a dangerous creature, however gentle and nice in person," the biographer Hermione Lee once wrote . Swift has occasionally taken this idea to heart before, especially on her once-scorned, now revered hip-hop experiment, Reputation . But now she's screaming from the hilltop, sparing no one, including herself as she tries to prop up one man's flagging interest and then falls for others' duplicity. "I know my pain is such an imposition," Swift sang in last year's " You're Losing Me ," a prequel to the explosive confessional mode of Tortured Poets , where that pain grows nearly suicidal, feeds romantic obsession, and drives her to become a "functional alcoholic" and a madwoman who finds strength in chaos in a way that recalls her friend Emma Stone's cathartic performance as Bella in Poor Things . (Bella, remember, comes into self-possession by learning to read and write.) " Who's afraid of little old me? " Swift wails in the album's window-smashing centerpiece bearing that title; in " But Daddy I Love Him ," she runs around screaming with her dress unbuttoned and threatens to burn down her whole world. These accounts of unhinged behavior reinforce the message that everybody had better be scared of this album — especially her exes, but also her business associates, the media and, yes, her fans, who are not spared in her dissection of just who's made her miserable over the past few years.

Listen to the album

I'm not getting into the dirty details; those who crave them can listen to Tortured Poets themselves and easily uncover them. They're laid out so clearly that anyone who's followed Swift's overly documented life will instantly comprehend who's who: the depressive on the heath, the tattooed golden retriever in her dressing room. Here's my reading of her album-as-novel — others' interpretations may vary: Swift's first-person protagonist (let's call her "Taylor") begins in a memory of a long-ago love affair that left her melancholy but on civil terms, then has an early meeting with a tempting rogue, who declares he's the Dylan Thomas to her Patti Smith; no, she says, though she's sorely tempted, we're "modern idiots," and she leaves him behind for a while. Then we get scenes from a stifling marriage to a despondent and distracted child-man. "So long, London," she declares, fleeing that dead end. From then on, it's the rogue on all cylinders. They connect, defy the daddy figures who think they're bad for each other, speak of rings and baby carriages. Those daddies continue to meddle in this newfound freedom.

In this main story arc, Swift writes about erotic desire as she never has before: She's "fresh out the slammer" (ouch, the rhetoric) and her bedsheets are on fire. She cannot stop rhapsodizing about this new love object and her commitment to their outlaw hunger for each other. It's " Love Story ," updated and supersized, with a proper Romeo at its center — a forbidden, tragic soulmate, a perfect match who's also a disastrous one. Swift peppers this section of Tortured Poets with name-drops ("Jack" we know, " Lucy " might be a tricky slap at Romeo, hard to tell) and instantly searchable references; he sends her a song by The Blue Nile and traces hearts on her face but tells revolting jokes in the bar and eventually reveals himself as a cad, a liar, a coward. She recovers, but not really. In the end, she does move on but still dreams of him hearing one of their songs on a jukebox and dolefully realizing the young girl he's now with has never heard it before.

Insert the names yourself. They do matter, because her backstories are key to Swift's appeal; they both keep her human-sized and amplify her fame. Swift's artistry is tied up in her deployment of celebrity, a slippery state in which a real life becomes emblematic. Like no one before, she's turned her spotlit day-to-day into a conceptual project commenting on women's freedom, artistic ambition and the place of the personal in the public sphere. As a celebrity, Swift partners with others: her model and musician friends, her actor/musician/athlete consorts, brands, even (warily) political causes. And with her fans, the co-creators of her stardom.

Her songs stand apart, though. They remain the main vehicle through which, negotiating unimaginable levels of renown, Swift continually insists on speaking only for herself. A listener has to work to find the "we" in her soliloquies. There are plenty of songs on Tortured Poets in which others will find their own experiences, from the sultry blue eroticism of " Down Bad " to the click of recognition in " I Can Fix Him (No Really I Can) ." But Swift's lack of concern about whether these songs speak for and to anyone besides herself is audible throughout the album. It's the sound of her freedom.

Taylor Swift: Tiny Desk Concert

She also confronts the way fame has cost her, fully exploring questions she raised on Reputation and in " Anti-Hero ." There are hints, more than hints, that her romance with the rogue was derailed partly because her business associates found it problematic, a danger to her precious reputation. And when she steps away from the man-woman predicament, Swift ponders the ephemeral reality of the success that has made private decisions nearly impossible. A lovely minuet co-written with Dessner, " Clara Bow " stages a time-lapsed conversation between Swift and the power players who've helped orchestrate her rise even as she knows they won't be concerned with her eventual obsolescence. "You look like Clara Bow ," they say, and later, "You look like Stevie Nicks in '75." Then, a turn: "You look like Taylor Swift," the suits (or is it the public, the audience?) declare. "You've got edge she never did." The song ends abruptly — lights out. This scene, redolent of All About Eve , reveals anxieties that all of Swift's love songs rarely touch upon.

One reason Swift went from being a normal-level pop star to sharing space with Beyoncé as the era's defining spirit is because she is so good at making the personal huge, without fussing over its translation into universals. In two decades of talking back to heartbreakers, Swift has called out gaslighting, belittling, neglect, false promises — all the hidden injuries that lovers inflict on each other, and that a sexist society often overlooks or forgives more easily from men. In "The Manuscript," which calls back to a romantic trauma outside the Tortured Poets frame, she sings of being a young woman with an older man making "coffee in a French press" and then "only eating kids cereal" and sleeping in her mother's bed when he dumps her; any informed Swift fan's mind will race to songs and headlines about cads she's previously called out in fan favorites like "Dear John" and "All Too Well" — the beginnings of the mission Tortured Poets fulfills.

Reviews of more Taylor Swift albums on NPR

In the haze of 'Midnights,' Taylor Swift softens into an expanded sound

Let's Talk About Taylor Swift's 'Folklore'

Show And Tell: On 'Lover,' Taylor Swift Lets Listeners In On Her Own Terms

The Old Taylor's Not Dead

The Many New Voices Of Taylor Swift

Taylor Swift Leaps Into Pop With 'Red'

Swift's pop side (and perhaps her co-writers' influence) shows in the way she balances the claustrophobic referentiality of her writing with sparkly wordplay and well-crafted sentimental gestures. On Tortured Poets , she's less strategic than usual. She lets the details fall the way they would in a confession session among besties, not trying to change them from painful memories into points of connection. She's just sharing. Swift bares every crack in her broken heart as a way of challenging power structures, of arguing that emotional work that men can sidestep is still expected from women who seem to own the world.

Throughout Tortured Poets, Swift is trying to work out how emotional violence occurs: how men inflict it on women and women cultivate it within themselves. It's worth asking how useful such a brutal evisceration of one privileged private life can be in a larger social or political sense; critics, including NPR's Leah Donnella in an excellent 2018 essay on the limits of the songwriter's reach, have posed that question about Swift's work for years. But we should ask why Swift's work feels so powerful to so many — why she has become, in the eyes of millions, a standard-bearer and a freedom fighter. Unlike Beyoncé, who loves a good emblem and is always thinking about history and serving the culture and communities she claims, Swift is making an ongoing argument about smaller stories still making a difference. Her callouts can be viewed as petty, reflecting entitlement or even narcissism. But they're also part of her wrestling with the very notion of significance and challenging hierarchies that have proven to be so stubborn they can feel intractable. That Swift has reached such a peak of influence in the wake of the #MeToo movement isn't an accident; even as that chapter in feminism's history can seem to be closing, she insists on saying, "believe me." That isn't the same as saying "believe all women," but by laying claim to disputed storylines and fighting against silence, she at the very least reminds listeners that such actions matter.

Listening to Tortured Poets , I often thought of "The Last Day of Our Acquaintance," a song that Sinéad O'Connor recorded when she was in her young prime, not yet banished from the mainstream for her insistence on speaking politically. Like Swift's best work, its lyrics are very specific — allegedly about a former manager and lover — yet her directness and conviction expand their reach. In 1990, that a woman in her mid-20s would address a belittling man in this way felt startling and new. Taylor Swift came to prominence in a culture already changing to make room for such testimonies, if not — still — fully able to honor them. She has made it more possible for them to be heard. "I talk and you won't listen to me," O'Connor wailed . "I know your answer already." Swift doesn't have to worry about whether people will listen. But she knows that this could change. That's why she is writing it all down.

- Taylor Swift

Advertisement

Supported by

Review: Steve Carell as the 50-Year-Old Loser in a Comic ‘Uncle Vanya’

Sleek, lucid, amusing, often beautiful, it’s Chekhov with everything, except the main thing.

- Share full article

By Jesse Green

Why is it called “Uncle Vanya”? All the man does is mope, mope harder, try to do something other than moping, fail miserably and mope some more.

You can’t blame him. Vanya has spent most of his nearly 50 years scraping thin profit from a provincial estate, and not even for himself. The money he makes, running the farm with his unmarried niece, goes to support life in the city for his fatuous, gouty sort-of-ex-brother-in-law, an art professor who “knows nothing about art.” Also, Vanya is hopelessly in love with the old man’s exquisitely languorous young wife, who, reasonably enough, finds the moper pathetic.

In short, he is the opposite of the bold, laudable characters most writers of the late 1890s would name a play for. That’s probably just why Chekhov did it, announcing a new kind of protagonist for a new kind of drama. Life in his experience having turned squalid and absurd, he could no longer paint it for audiences as heroic. So how could his protagonist be a hero?

The “Uncle Vanya” that opened on Wednesday at the Vivian Beaumont Theater, its 10th Broadway revival in 100 years, sees Chekhov’s epochal bet and raises it. If Vanya is properly no hero in this amusing but rarely deeply affecting production, it’s because he’s no one at all. He despairs and disappears.

That would seem to be quite a trick, given that he’s played by Steve Carell, the star of “The Office” and, perhaps more relevantly, “The 40-Year-Old Virgin.” Carell’s Vanya imports from those appearances the weaselly overeagerness that makes you roll your eyes at him while also worrying about his mental health. He makes jokes that aren’t. He gets excited over all the wrong things. Rain coming? He called it.

Without a camera trained on such a man, you quickly learn to ignore him, as you would in real life. Indeed, in Lila Neugebauer’s sleek, lucid staging, you barely notice Vanya even as he makes his first entrance, hidden behind a bench. When he speaks you don’t pay much more attention; in Heidi Schreck’s smooth, faithful yet colloquial new version, his first words, naturally, are complaints. “Ever since the professor showed up with his spouse ,” he says, with a bitterly sarcastic spin on the last word, “my life has been total chaos.”

It’s true that the professor — here called Alexander instead of the Russian mouthful Aleksandr Vladimirovich Serebryakov — has thrown the household into disarray with his demands and pains and unearned hauteur. But his wife, here called Elena, has been, if possible, even more disruptive.

Beauty and boredom in close quarters will do that. If Vanya is a malodorous dog she easily shoos away, a local doctor, Astrov, proves the more tempting companion. He is intelligent, cynical and passionate, at first about ecology only, but soon about Elena as well.

Vanya is usually the linchpin of the plot. His envy of both Alexander and Astrov, his crush on Elena, his resentment of his mother (who delights in Alexander’s every apothegm), and his heedlessness of his niece’s needs (Sonia is in love with Astrov) all return to ding him like a comically inerrant boomerang. No wonder the role has been catnip for big Broadway hams like Ralph Richardson, George C. Scott, Derek Jacobi and Nicol Williamson.

But Carell is no ham: He’s precise, natural, unimposing. That’s a reasonable choice given the text in vitro, which reads as a comedy of anticlimax. But in vivo, onstage, it should be, as well, a tragedy of inertia. For that you need a dominant Vanya with a rageful inner life.

That it does not have one here is not fatal. Neugebauer is such a detailed director, honing every moment and movement to a chic polish, that this typically gorgeous Lincoln Center Theater production offers a hundred things to enjoy. Mimi Lien’s sylvan set, receding into the depths of the Beaumont stage, is one. Musical interludes, by the songwriter Andrew Bird, often featuring accordion and violin, are another, striking the play’s jaunty melancholy just right. Kaye Voyce’s contemporary costumes, quickly identifying each character’s status and self-concept, are wonderful, and in the case of Elena’s knit dresses with their form-hugging cuts, sensational.

So is the woman who wears them: Anika Noni Rose. Building on her history of ingénues (“Caroline, or Change”) and sirens (“Carmen Jones”), she arrives here as the haunting question mark at the end of everyone’s thoughts. I have never seen an Elena so decisive and, at the same time, so lost.

That’s an advantage of Carell ceding ground: The other characters have more room to emerge. Of course, the play always draws attention to Elena (written for Chekhov’s soon-to-be wife) and Astrov (originally played by Stanislavsky himself) because they are the only feasible lovers. But here, Astrov, given great self-deprecatory wit by William Jackson Harper, is more dimensional than usual, including, for once, an interest in trees that’s as painfully visceral as his interest in Elena.

The supporting roles are just as vividly filled. Alfred Molina as the professor is especially luxurious casting; nailing the babyish self-regard of the academically pampered, he is never funnier than when totally serious about his imaginary importance. As Sonia, Alison Pill has obviously thought about what it means to have lived so long with her uncle, breathing in his grievance, not daring to credit her own. This makes her the only truly dignified character: the one who makes you want to cry.

Otherwise, I wanted to laugh. Jayne Houdyshell creates an instantly recognizable type out of Vanya’s mother: the cultured Upper West Side lady in multicolor shmattes who reads political journals and is probably skeptical about produce. Even Marina, the family’s former nanny, is given room for a wicked read by Mia Katigbak. Lovingly resigned to the family’s foibles, she is nevertheless the pin in their hot air balloon.

If all this works well as light comedy, the ideal Chekhov balance may require something heavier as ballast. I don’t just mean a heavier central performance, one that believably builds to the famous attempt at violence in Act III, and suffers its full consequences.

It may also be that Schreck — with the keen ear for unimpeded flow she demonstrated in “What the Constitution Means to Me,” on Broadway in 2019 — has wiped the text too clean of the specifics and formalities that can provide useful resistance. She sets the play nowhere and at no time in particular: The cottage in Finland the professor wants to buy becomes, in this version, an unmapped “beach house”; money is measured in what sounds like contemporary dollars, yet there are (thank God) no cellphones.

These small decisions — and the production’s big ones, too — make sense individually. Collectively, they add up to a lovely evening in the theater. That’s not a backhanded compliment. But I have a feeling that if Chekhov heard “Uncle Vanya” described that way, well, he’d never stop moping.

Uncle Vanya Through June 16 at the Vivian Beaumont Theater, Manhattan; vanyabroadway.com . Running time: 2 hours 25 minutes.

Jesse Green is the chief theater critic for The Times. He writes reviews of Broadway, Off Broadway, Off Off Broadway, regional and sometimes international productions. More about Jesse Green

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

By Suzzy Roche. Voice/Hyperion, $24.99. A singer herself, Roche surely knows firsthand the kind of things her fictional rocker, Mary Saint, went through on that "long Tilt-A-Whirl ride" from ...

An intensely moving story about an ex-teacher whose obesity defines his life. T his lovely and memorable novel could sound schmaltzy or sentimental from a short description. It is very far from ...

11 books2,474 followers. Liz Moore is the author of the novels THE WORDS OF EVERY SONG (Broadway Books, 2007), HEFT (W.W. Norton, 2012), THE UNSEEN WORLD (W.W. Norton, 2016), and the New York Times-bestselling Long Bright River (Riverhead, 2019). A winner of the Rome Prize in Literature, she lives in Philadelphia with her family, and teaches in ...

Reviews, essays, best sellers and children's books coverage from The New York Times Book Review.

Like Elizabeth McCracken's The Giant's House, Heft is a novel about love and family found in the most unexpected places. BUY THE BOOK. PRAISE FOR HEFT "Moore's characters are lovingly drawn . . . A truly original voice." ... THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW "Like its characters' hearts, Heft is full of grace. It's a beautifully written and very ...

From Amal El-Mohtar's science-fiction and fantasy column. Blackstone | $26.99. TO FREE THE CAPTIVES: A Plea for the American Soul. Tracy K. Smith. In her musical new memoir, the former poet ...

At times, the characters and the emotional core of the events are almost obscured by such quick maneuvering through the weighty plot. Dark and unsettling, this novel's end arrives abruptly even as readers are still moving at a breakneck speed. 66. Pub Date: April 24, 2018. ISBN: 978-1-5011-5464-5. Page Count: 368.

Reviews; Heft; Heft. About the Book Heft. by Liz Moore. Former academic Arthur Opp weighs 550 pounds and hasn't left his rambling Brooklyn home in a decade. Twenty miles away, in Yonkers, 17-year-old Kel Keller navigates life as the poor kid in a rich school and pins his hopes on what seems like a promising baseball career --- if he can ...

HEFT is both a lyrically written tale and an engrossing page-turner. In Arthur Opp, author Liz Moore gives us a complete, three-dimensional person rather than the media's stereotypical obese recluse; Arthur is quite heartbreakingly real, as is young Kel Keller, who we also grow to know.

From the New York Times bestselling author of Long Bright River : 'A stunningly sad and heroically hopeful tale…This is a beautiful novel about relationships of the most makeshift kind.' — O, The Oprah Magazine , Heft, A Novel, Liz Moore, 9780393343885. From the New York Times bestselling author of Long Bright River : 'A stunningly sad and ...

Our Reading Guide for Heft by Liz Moore includes Book Club Discussion Questions, Book Reviews, Plot Summary-Synopsis and Author Bio. HOME; ABOUT; CONTACT; Search Go . Getting Started ... Book Reviews: Discussion Questions: Full Version: Print: Page 1 of 4. Heft Liz Moore, 2012 W.W. Norton & Co. 352 pp.

Heft leads to hope." ― People "Tender, thoughtful." ― New York Times Book Review "Moore's writing is clear, persuasive, and totally engaging, bringing her characters to life in all their sweet, quirky glory." ― Boston Globe "This is not a novel with a happy ending, and that's a good thing. Moore doesn't tie her story up in a pretty ...

I purchased the book because of the rave reviews and the very promising sample, which introduces the reader to Arthur Opp - a unique, quirky but utterly believable and intriguing character. However, beyond the sample, the book quickly shifts to the point of view of Charlene's son, whose present-tense, 17-year-old voice did not ring true to me.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, The New York Times Book Review is operating remotely and will accept physical submissions by request only. If you wish to submit a book for review consideration, please email a PDF of the galley at least three months prior to scheduled publication to [email protected]. . Include the publication date and any related press materials, along with links to ...

From Tariro Mzezewa's review. Penguin Press | $30. THE CAR: The Rise and Fall of the Machine That Made the Modern World. Bryan Appleyard. In his appropriately propulsive history of the automobile ...

Tales of Murder and Retribution. Extra Salt. EVERY LIVING THING. Taxonomy Men. The Rise of the Machines. THE ANXIOUS GENERATION How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness. The writer discusses his new book, ' The Anxious Generation.'. History's Ghosts.

Pablo Amargo. By Sarah Weinman. Dec. 23, 2021. Murder is a shock to anyone's system, but especially so for Molly Gray, the titular character of Nita Prose's endearing debut, THE MAID ...

David Sanger of the New York Times delivers a must-read on the foreign policy challenges now facing US leaders Lloyd Green Sun 21 Apr 2024 05.00 EDT Last modified on Sun 21 Apr 2024 05.02 EDT

The writer Ayana Mathis finds unexpected hope in novels of crisis by Ling Ma, Jenny Offill and Jesmyn Ward. At 28, the poet Tayi Tibble has been hailed as the funny, fresh and immensely skilled ...

5 Strategies for Improving Mental Health at Work. by. Morra Aarons-Mele. April 18, 2024, Updated April 24, 2024. Xin He/Getty Images. Summary. Companies are investing in — and talking about ...

For Caleb Carr, Salvation Arrived on Little Cat's Feet. As he struggled with writing and illness, the "Alienist" author found comfort in the feline companions he recalls in a new memoir ...

Enlarge this image. On Taylor Swift's 11th album, The Tortured Poets Department, her artistry is tangled up in the details of her private life and her deployment of celebrity. But Swift's lack of ...

April 24, 2024. Spring! There's no better time of year for a baseball romance. We'll wind up the column with a much-anticipated book by Cat Sebastian, but we lead off with KT Hoffman's ...

Danielle Dutton's Surreal Take on Human Existence. "Prairie, Dresses, Art, Other," the author's new collection, ranges from a playful one-act drama set in a lake to short fiction rife with ...

Our Coverage of the Capitol Riot and its Fallout. The Events on Jan. 6. Timeline: On Jan. 6, 2021, a mob of supporters of President Donald Trump raided the U.S. Capitol. Here is a close look at ...

A version of this Best Sellers report appears in the April 21, 2024 issue of The New York Times Book Review. Rankings on weekly lists reflect sales for the week ending April 6, 2024. Rankings ...

Reviews, essays, best sellers and children's books coverage from The New York Times Book Review.

From Megan O'Grady's review. Mariner | $37.50. OUT OF THE DARKNESS: The Germans, 1942-2022. Frank Trentmann. Over the past eight decades, the public debates about guilt and suffering in the ...

The blade went in all the way to the optic nerve, which meant there would be no possibility of saving the vision. It was gone. As bad as this was, he had been fortunate. A doctor says, "You're ...

All the man does is mope, mope harder, try to do something other than moping, fail miserably and mope some more. You can't blame him. Vanya has spent most of his nearly 50 years scraping thin ...