Writing A Narrative Essay

- Library Resources

- Books & EBooks

- What is an Narrative Essay?

- Choosing a Topic

- MLA Formatting

Using Dialogue

- Using Descriptive Writing

- OER Resources

- Copyright, Plagiarism, and Fair Use

Examples of Dialogue Tags

Examples of Dialogue Tags:

interrupted

Ebooks in Galileo

Additional Links & Resources

- Dialogue Cheat Sheet

Dialogue is an exchange of conversation between two or more people or characters in a story. As a literary style, dialogue helps to advance the plot, reveal a character's thoughts or emotions, or shows the character's reaction within the story. Dialogue gives life to the story and supports the story's atmosphere.

There are two types of dialogue that can be used in an narrative essay.

Direct dialogue is written between inverted commas or quotes. These are the actual spoken words of a character

Indirect dialogue is basically telling someone about what another person said

Formatting Dialogue

Dialogue is an important part of a narrative essay, However formatting dialogue can be troublesome at times.

When formatting dialogue use these rules and examples to help with your formatting:

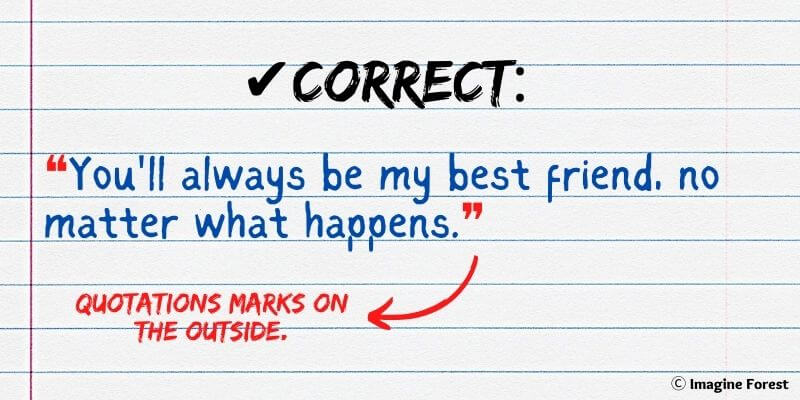

Place double quotation marks at the beginning an end of spoken words. The quotations go on the outside of both the words and end-of-dialogue punctuation.

- Example: "What is going on here?" John asked.

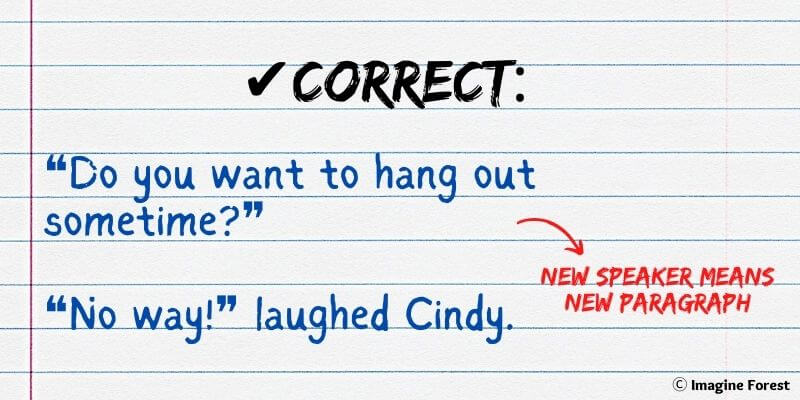

Each speaker gets a new paragraph that is indented.

“hi,” said John as he stretched out his hand.

"Good Morning, how are you?" said Brad shaking John’s hand.

"Good. Thanks for asking," John said.

Each speaker’s actions are in the same paragraph as their dialogue.

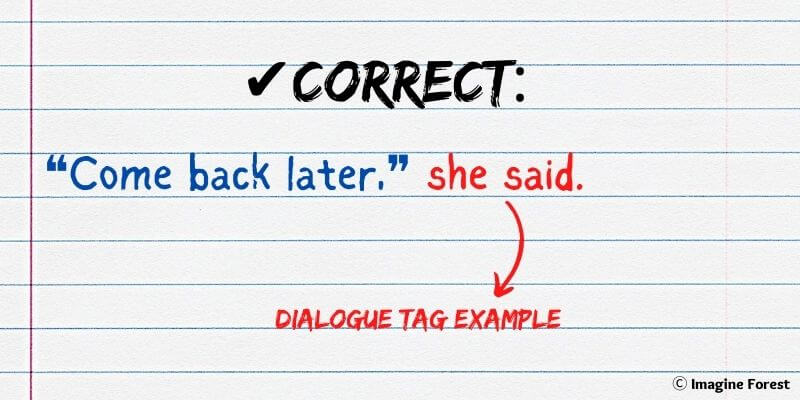

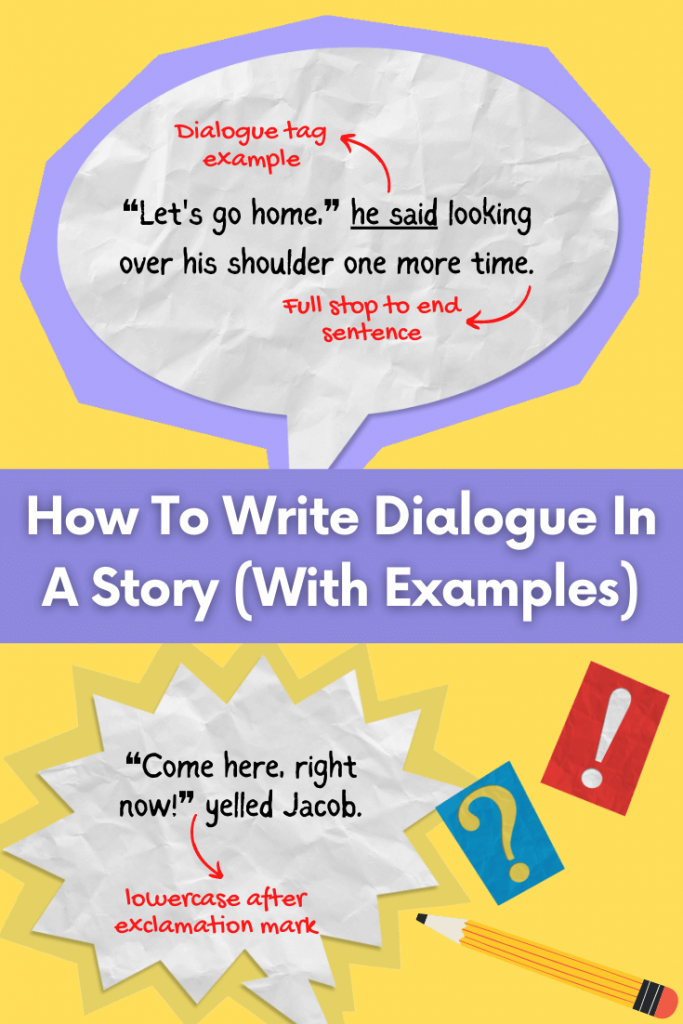

A dialogue tag is anything that indicates which character spoke and describes how they spoke.

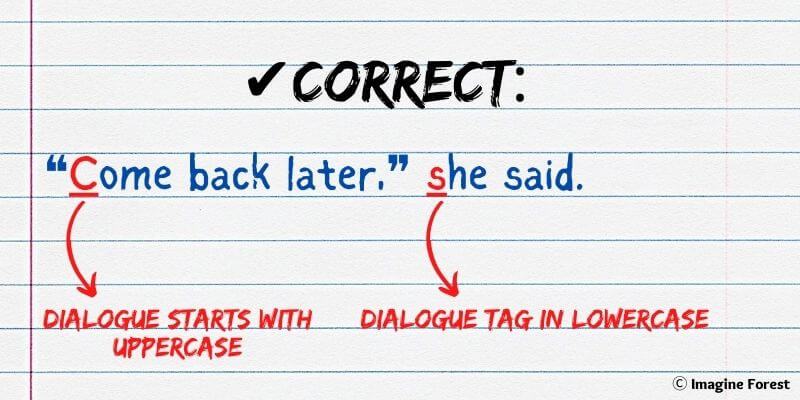

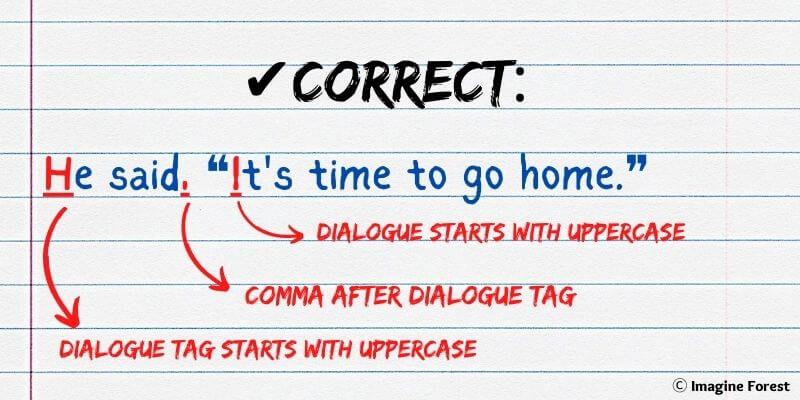

If the tag comes before the dialogue, use a comma straight after the tag. If the dialogue is the beginning of a sentence, capitalize the first letter. End the dialogue with the appropriate punctuation (period, exclamation point, or question mark), but keep it INSIDE the quotation marks.

- Examples Before:

James said, “I’ll never go shopping with you again!”

John said, “It's a great day to be at the beach.”

She opened the door and yelled, “Go away! Leave me alone!”

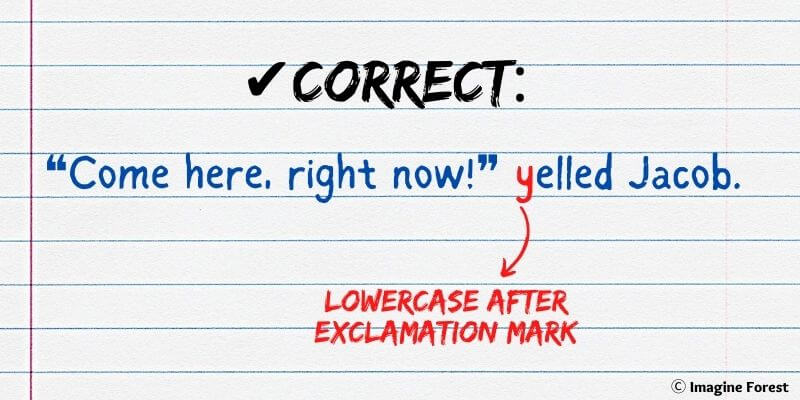

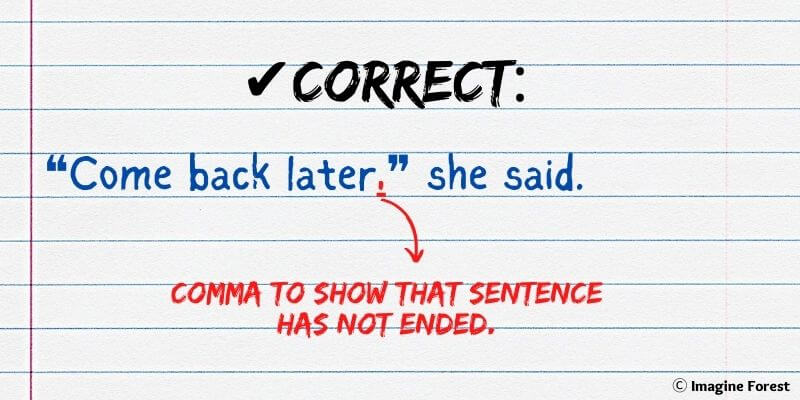

If the dialogue tag comes after the dialogue , Punctuation still goes INSIDE quotation marks. Unless the dialogue tag begins with a proper noun, it is not capitalized. End the dialogue tag with appropriate punctuation. Use comma after the quote unless it ends with a question mark or exclamation mark.

- Examples After:

“Are you sure this is real life?” Lindsay asked.

“It’s so gloomy out,” he said.

“Are we done?” asked Brad .

“This is not your concern!” Emma said.

If dialogue tag is in the middle of dialogue. A comma should be used before the dialogue tag inside the closing quotation mark; Unless the dialogue tag begins with a proper noun, it is not capitalized. A comma is used after the dialogue tag, outside of quotation marks, to reintroduce the dialogue. End the dialogue with the appropriate punctuation followed by the closing quotation marks.

When it is two sentences, the first sentence will end with a punctuation mark and the second begins with a capital letter.

- Examples middle:

“Let’s run away,” she whispered, “we wont get another chance.”

“I thought you cared.” Sandy said, hoping for an explanation. “How could you walk away?”

“I can’t believe he’s gone,” Jerry whispered. “I’ll miss him.”

Questions in dialogue.

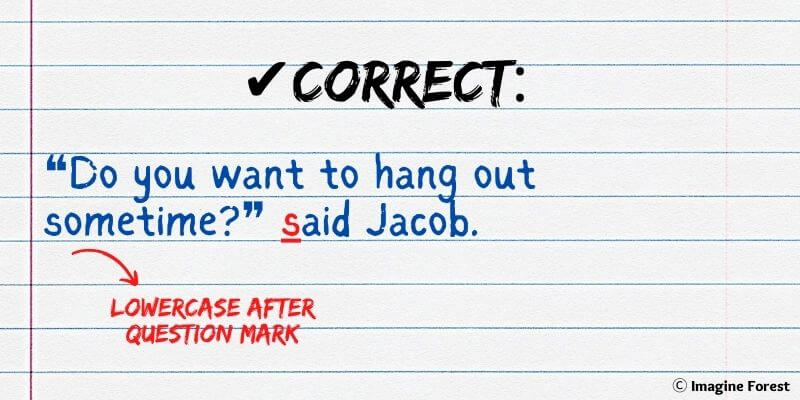

if there is a dialogue tag, the question mark will act as a comma and you will then lowercase the first word in the dialogue tag

- Example: What are you doing?" he asked.

if there is simply an action after the question, the question mark acts as a period and you will then capitalize the first word in the next sentence.

“Sarah, why didn't you text me back?” Jane asked.

“James, why didn’t you show up?” Carol stomped her feet in anger before slamming the door behind her.

If the question or exclamation ends the dialogue, do not use commas to separate the dialogue from dialogue tags.

- Example: “Sarah, why didn't you text me back?” Jane asked.

If the sentence containing the dialogue is a question, then the question mark goes outside of the quotation marks.

Did the teacher say, “The Homework is due Tomorrow”?

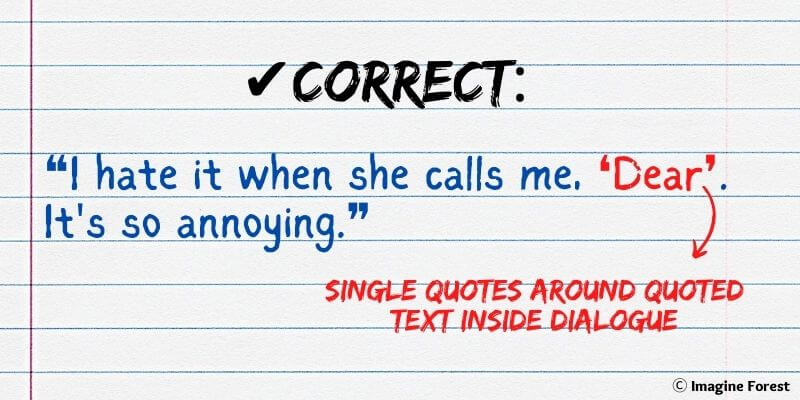

If you have to quote something within the dialogue. When a character quotes someone else, use double-quotes around what your character says, then single-quotes around the speech they’re quoting.

- Example:

"When doling out dessert, my grandmother always said, 'You may have a cookie for each hand.'"

Dashes & Ellipses:

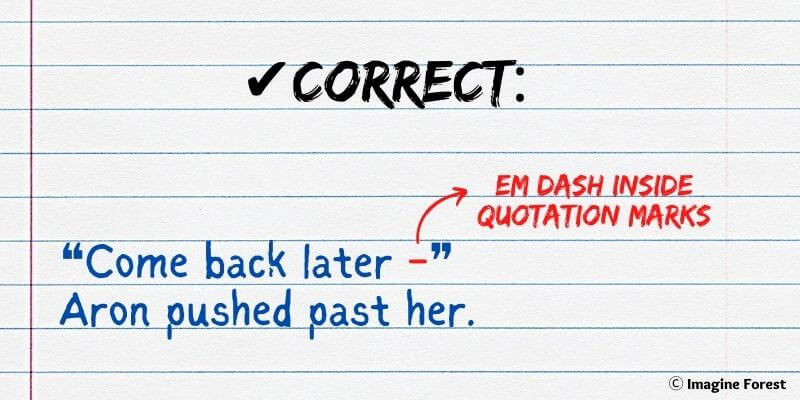

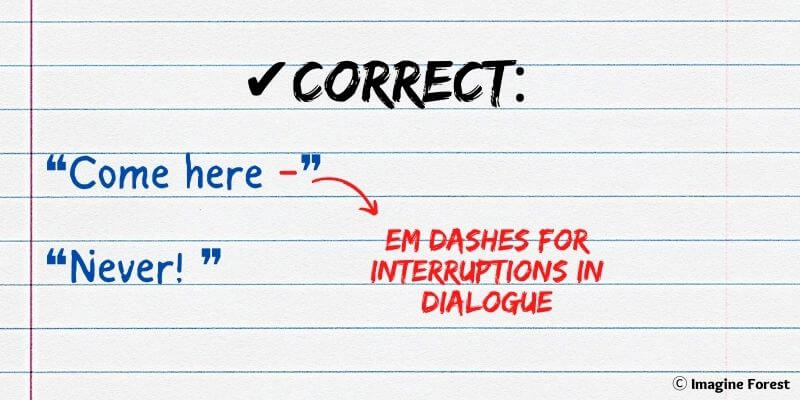

Dashes ( — ) are used to indicate abruptly interrupted dialogue or when one character's dialogue is interrupted by another character.

Use an em dash inside the quotation marks to cut off the character mid-dialogue, usually with either (A) another character speaking or (B) an external action.

- Including the em dash at the end of the line of dialogue signifies that your character wasn't finished speaking.

- If the speaking character's action interrupts their own dialogue .

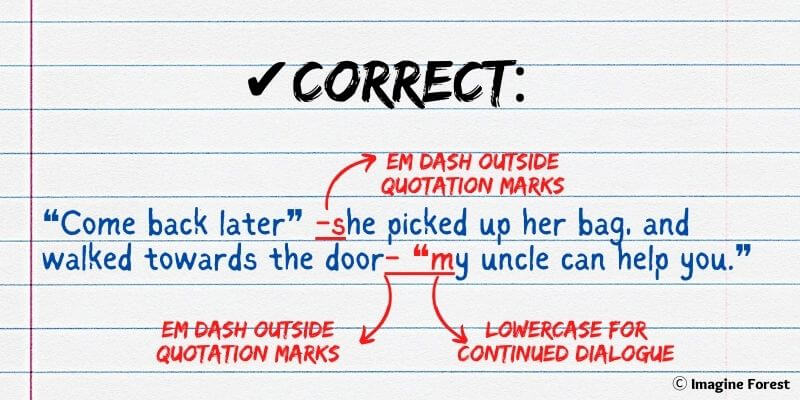

- Use em dashes outside the quotation marks to set off a bit of action without a speech verb.

Examples:

- Heather ran towards Sarah with excitement. “You won’t believe what I found out—”

- "Is everything—" she started to ask, but a sharp look cut her off.

- "Look over there—" She snapped her mouth shut so she didn't give the secret away.

- "Look over there"—she pointed towards the shadow—"by the stairway."

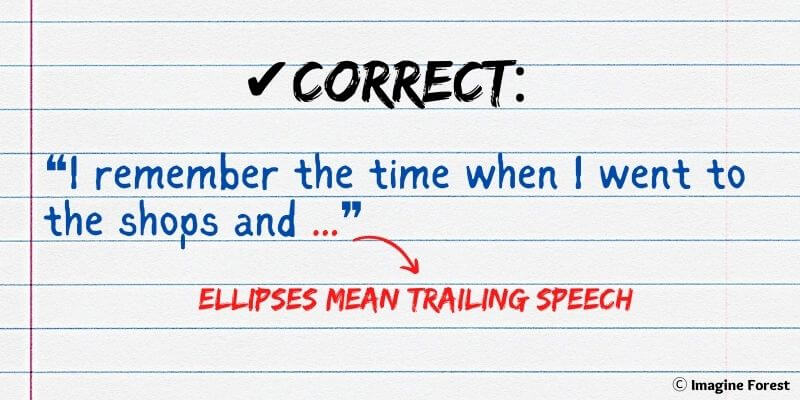

Use ellipses (...) when a character has lost their train of thought or can't figure out what to say

- Example: “You haven’t…” he trailed off in disbelief.

Action Beats

Action beats show what a character is doing before, during, or after their dialogue.

“This isn't right.” She squinted down at her burger. “Does this look like it is well done to you?”

She smiled. “I loved the center piece you chose.”

If you separate two complete sentences, you will simply place the action beat as its own sentence between two sets of quotes.

“I never said he could go to the concert.” Linda sighed and sat in her chair. “He lied to you again.”

- << Previous: MLA Formatting

- Next: Using Descriptive Writing >>

- Last Updated: Jan 24, 2024 1:22 PM

- URL: https://wiregrass.libguides.com/c.php?g=1188382

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

How to Write Dialogue: 7 Great Tips for Writers (With Examples)

Hannah Yang

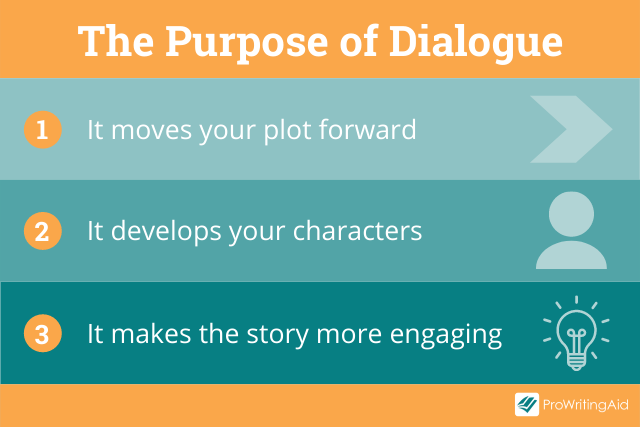

Great dialogue serves multiple purposes. It moves your plot forward. It develops your characters and it makes the story more engaging.

It’s not easy to do all these things at once, but when you master the art of writing dialogue, readers won’t be able to put your book down.

In this article, we will teach you the rules for writing dialogue and share our top dialogue tips that will make your story sing.

Dialogue Rules

How to format dialogue, 7 tips for writing dialogue in a story or book, dialogue examples.

Before we look at tips for writing powerful dialogue, let’s start with an overview of basic dialogue rules.

- Start a new paragraph each time there’s a new speaker. Whenever a new character begins to speak, you should give them their own paragraph. This rule makes it easier for the reader to follow the conversation.

- Keep all speech between quotation marks . Everything that a character says should go between quotation marks, including the final punctuation marks. For example, periods and commas should always come before the final quotation mark, not after.

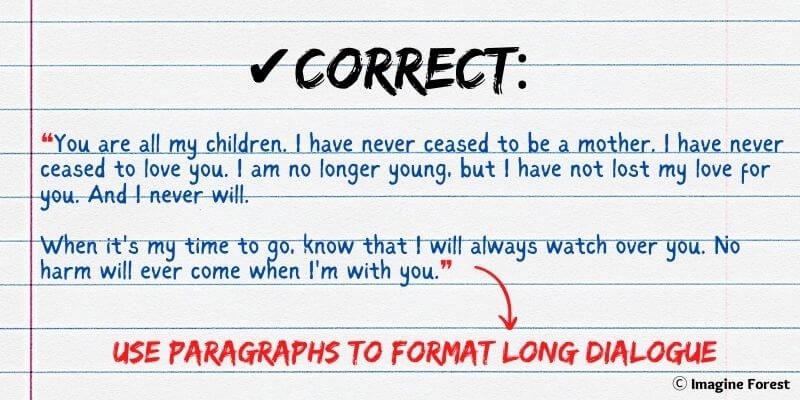

- Don’t use end quotations for paragraphs within long speeches. If a single character speaks for such a long time that you break their speech up into multiple paragraphs, you should omit the quotation marks at the end of each paragraph until they stop talking. The final quotation mark indicates that their speech is over.

- Use single quotes when a character quotes someone else. Whenever you have a quote within a quote, you should use single quotation marks (e.g. She said, “He had me at ‘hello.’”)

- Dialogue tags are optional. A dialogue tag is anything that indicates which character is speaking and how, such as “she said,” “he whispered,” or “I shouted.” You can use dialogue tags if you want to give the reader more information about who’s speaking, but you can also choose to omit them if you want the dialogue to flow more naturally. We’ll be discussing more about this rule in our tips below.

Let’s walk through some examples of how to format dialogue .

The simplest formatting option is to write a line of speech without a dialogue tag. In this case, the entire line of speech goes within the quotation marks, including the period at the end.

- Example: “I think I need a nap.”

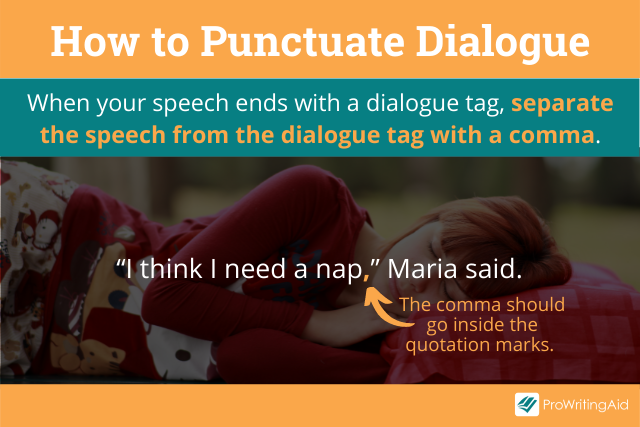

Another common formatting option is to write a single line of speech that ends with a dialogue tag.

Here, you should separate the speech from the dialogue tag with a comma, which should go inside the quotation marks.

- Example: “I think I need a nap,” Maria said.

You can also write a line of speech that starts with a dialogue tag. Again, you separate the dialogue tag with a comma, but this time, the comma goes outside the quotation marks.

- Example: Maria said, “I think I need a nap.”

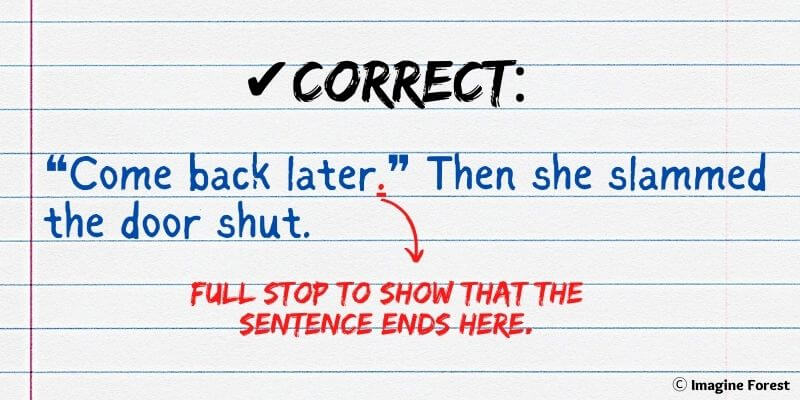

As an alternative to a simple dialogue tag, you can write a line of speech accompanied by an action beat. In this case, you should use a period rather than a comma, because the action beat is a full sentence.

- Example: Maria sat down on the bed. “I think I need a nap.”

Finally, you can choose to include an action beat while the character is talking.

In this case, you would use em-dashes to separate the action from the dialogue, to indicate that the action happens without a pause in the speech.

- Example: “I think I need”—Maria sat down on the bed—“a nap.”

Now that we’ve covered the basics, we can move on to the more nuanced aspects of writing dialogue.

Here are our seven favorite tips for writing strong, powerful dialogue that will keep your readers engaged.

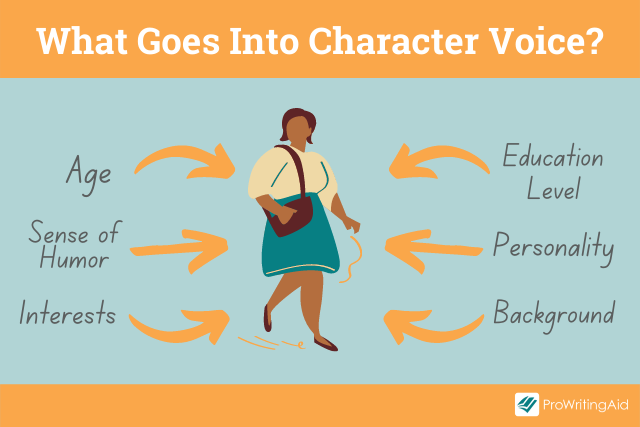

Tip #1: Create Character Voices

Dialogue is a great way to reveal your characters. What your characters say, and how they say it, can tell us so much about what kind of people they are.

Some characters are witty and gregarious. Others are timid and unobtrusive.

Speech patterns vary drastically from person to person.

To make someone stop talking to them, one character might say “I would rather not talk about this right now,” while another might say, “Shut your mouth before I shut it for you.”

When you’re writing dialogue, think about your character’s education level, personality, and interests.

- What kind of slang do they use?

- Do they prefer long or short sentences?

- Do they ask questions or make assertions?

Each character should have their own voice.

Ideally, you want to write dialogue that lets your reader identify the person speaking at any point in your story just by looking at what’s between the quotation marks.

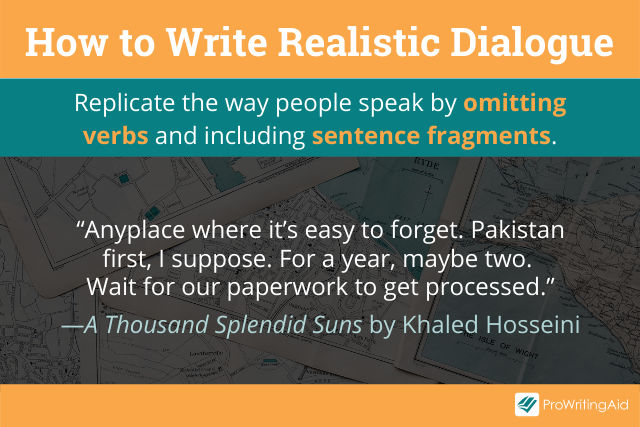

Tip #2: Write Realistic Dialogue

Good dialogue should sound natural. Listen to how people talk in real life and try to replicate it on the page when you write dialogue.

Don’t be afraid to break the rules of grammar, or to use an occasional exclamation point to punctuate dialogue.

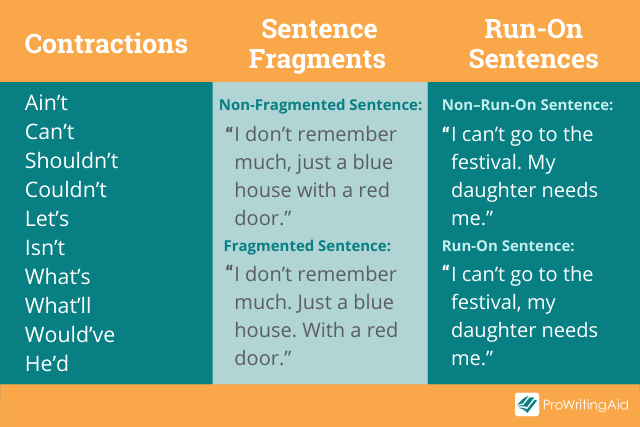

It’s okay to use contractions , sentence fragments , and run-on sentences , even if you wouldn’t use them in other parts of the story.

This doesn’t mean that realistic dialogue should sound exactly like the way people speak in the real world.

If you’ve ever read a court transcript, you know that real-life speech is riddled with “ums” and “ahs” and repeated words and phrases. A few paragraphs of this might put your readers to sleep.

Compelling dialogue should sound like a real conversation, while still being wittier, smoother, and better worded than real speech.

Tip #3: Simplify Your Dialogue Tags

A dialogue tag is anything that tells the reader which character is talking within that same paragraph, such as “she said” or “I asked.”

When you’re writing dialogue, remember that simple dialogue tags are the most effective .

Often, you can omit dialogue tags after the conversation has started flowing, especially if only two characters are participating.

The reader will be able to keep up with who’s speaking as long as you start a new paragraph each time the speaker changes.

When you do need to use a dialogue tag, a simple “he said” or “she said” will do the trick.

Our brains generally skip over the word “said” when we’re reading, while other dialogue tags are a distraction.

A common mistake beginner writers make is to avoid using the word “said.”

Characters in amateur novels tend to mutter, whisper, declare, or chuckle at every line of dialogue. This feels overblown and distracts from the actual story.

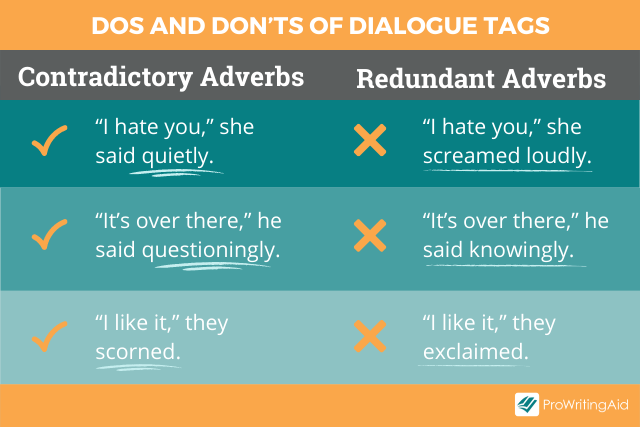

Another common mistake is to attach an adverb to the word “said.” Characters in amateur novels rarely just say things—they have to say things loudly, quietly, cheerfully, or angrily.

If you’re writing great dialogue, readers should be able to figure out whether your character is cheerful or angry from what’s within the quotation marks.

The only exception to this rule is if the dialogue tag contradicts the dialogue itself. For example, consider this sentence:

- “You’ve ruined my life,” she said angrily.

The word “angrily” is redundant here because the words inside the quotation marks already imply that the character is speaking angrily.

In contrast, consider this sentence:

- “You’ve ruined my life,” she said thoughtfully.

Here, the word “thoughtfully” is well-placed because it contrasts with what we might otherwise assume. It adds an additional nuance to the sentence inside the quotation marks.

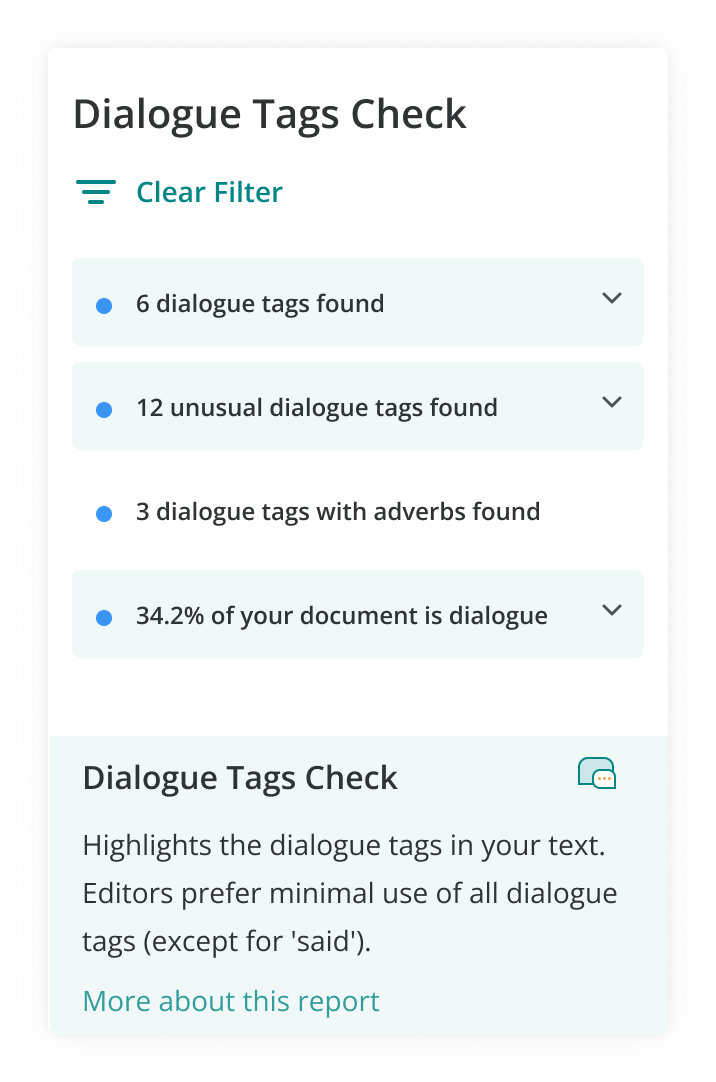

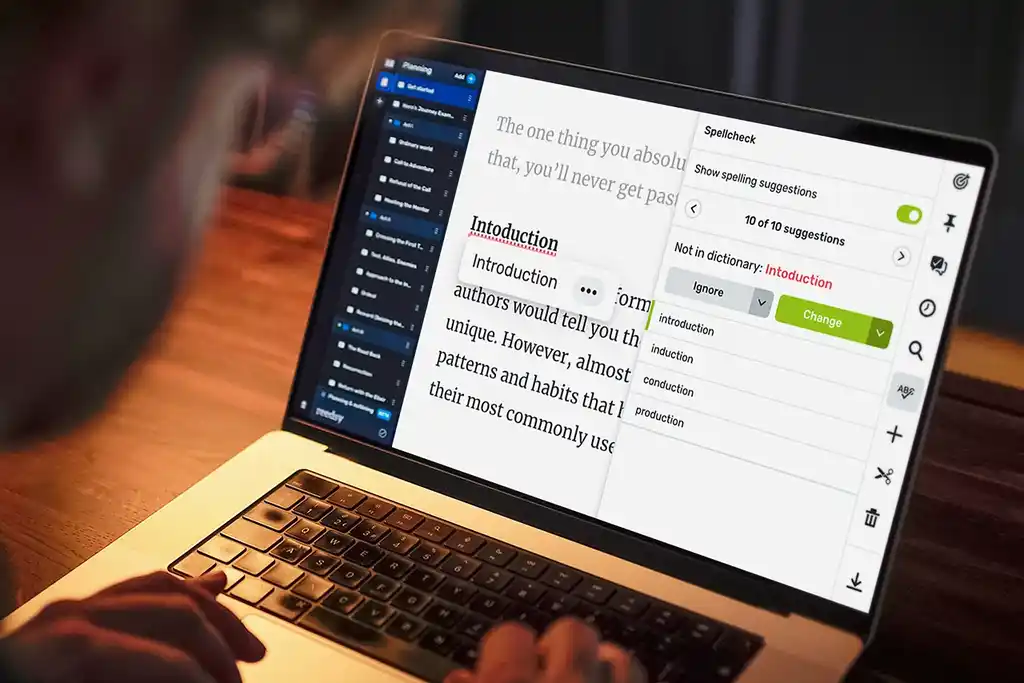

You can use the ProWritingAid dialogue check when you write dialogue to make sure your dialogue tags are pulling their weight and aren’t distracting readers from the main storyline.

Sign up for your free ProWritingAid account to check your dialogue tags today.

Tip #4: Balance Speech with Action

When you’re writing dialogue, you can use action beats —descriptions of body language or physical action—to show what each character is doing throughout the conversation.

Learning how to write action beats is an important component of learning how to write dialogue.

Good dialogue becomes even more interesting when the characters are doing something active at the same time.

You can watch people in real life, or even characters in movies, to see what kinds of body language they have. Some pick at their fingernails. Some pace the room. Some tap their feet on the floor.

Including physical action when writing dialogue can have multiple benefits:

- It changes the pace of your dialogue and makes the rhythm more interesting

- It prevents “white room syndrome,” which is when a scene feels like it’s happening in a white room because it’s all dialogue and no description

- It shows the reader who’s speaking without using speaker tags

You can decide how often to include physical descriptions in each scene. All dialogue has an ebb and flow to it, and you can use beats to control the pace of your dialogue scenes.

If you want a lot of tension in your scene, you can use fewer action beats to let the dialogue ping-pong back and forth.

If you want a slower scene, you can write dialogue that includes long, detailed action beats to help the reader relax.

You should start a separate sentence, or even a new paragraph, for each of these longer beats.

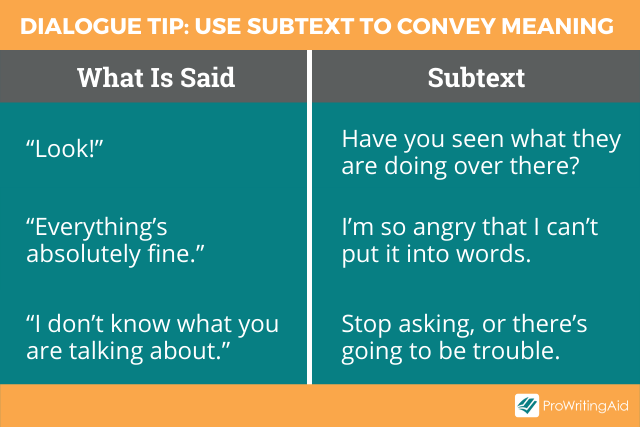

Tip #5: Write Conversations with Subtext

Every conversation has subtext , because we rarely say exactly what we mean. The best dialogue should include both what is said and what is not said.

I once had a roommate who cared a lot about the tidiness of our apartment, but would never say it outright. We soon figured out that whenever she said something like “I might bring some friends over tonight,” what she meant was “Please wash your dishes, because there are no clean plates left for my friends to use.”

When you’re writing dialogue, it’s important to think about what’s not being said. Even pleasant conversations can hide a lot beneath the surface.

Is one character secretly mad at the other?

Is one secretly in love with the other?

Is one thinking about tomorrow’s math test and only pretending to pay attention to what the other person is saying?

Personally, I find it really hard to use subtext when I write dialogue from scratch.

In my first drafts I let my characters say what they really mean. Then, when I’m editing, I go back and figure out how to convey the same information through subtext instead.

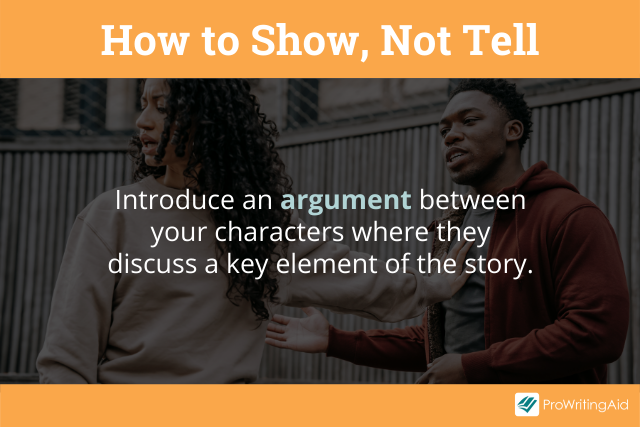

Tip #6: Show, Don’t Tell

When I was in high school, I once wrote a story in which the protagonist’s mother tells her: “As you know, Susan, your dad left us when you were five.”

I’ve learned a lot about the writing craft since high school, but it doesn’t take a brilliant writer to figure out that this is not something any mother would say to her daughter in real life.

The reason I wrote that line of dialogue was because I wanted to tell the reader when Susan last saw her father, but I didn’t do it in a realistic way.

Don’t shoehorn information into your characters’ conversations if they’re not likely to say it to each other.

One useful trick is to have your characters get into an argument.

You can convey a lot of information about a topic through their conflicting opinions, without making it sound like either of the characters is saying things for the reader’s benefit.

Here’s one way my high school self could have conveyed the same information in a more realistic way in just a few lines:

Susan: “Why didn’t you tell me Dad was leaving? Why didn’t you let me say goodbye?”

Mom: “You were only five. I wanted to protect you.”

Tip #7: Keep Your Dialogue Concise

Dialogue tends to flow out easily when you’re drafting your story, so in the editing process, you’ll need to be ruthless. Cut anything that doesn’t move the story forward.

Try not to write dialogue that feels like small talk.

You can eliminate most hellos and goodbyes, or summarize them instead of showing them. Readers don’t want to waste their time reading dialogue that they hear every day.

In addition, try not to write dialogue with too many trigger phrases, which are questions that trigger the next line of dialogue, such as:

- “And then what?”

- “What do you mean?”

It’s tempting to slip these in when you’re writing dialogue because they keep the conversation flowing. I still catch myself doing this from time to time.

Remember that you don’t need three lines of dialogue when one line could accomplish the same thing.

Let’s look at some dialogue examples from successful novels that follow each of our seven tips.

Dialogue Example #1: How to Create Character Voice

Let’s start with an example of a character with a distinct voice from Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets by J.K. Rowling.

“What happened, Harry? What happened? Is he ill? But you can cure him, can’t you?” Colin had run down from his seat and was now dancing alongside them as they left the field. Ron gave a huge heave and more slugs dribbled down his front. “Oooh,” said Colin, fascinated and raising his camera. “Can you hold him still, Harry?”

Most readers could figure out that this was Colin Creevey speaking, even if his name hadn’t been mentioned in the passage.

This is because Colin Creevey is the only character who speaks with such extreme enthusiasm, even at a time when Ron is belching slugs.

This snippet of written dialogue does a great job of showing us Colin’s personality and how much he worships his hero Harry.

Dialogue Example #2: How to Write Realistic Dialogue

Here’s an example of how to write dialogue that feels realistic from A Thousand Splendid Suns by Khaled Hosseini.

“As much as I love this land, some days I think about leaving it,” Babi said. “Where to?” “Anyplace where it’s easy to forget. Pakistan first, I suppose. For a year, maybe two. Wait for our paperwork to get processed.” “And then?” “And then, well, it is a big world. Maybe America. Somewhere near the sea. Like California.”

Notice the punctuation and grammar that these two characters use when they speak.

There are many sentence fragments in this conversation like, “Anyplace where it’s easy to forget.” and “Somewhere near the sea.”

Babi often omits the verbs from his sentences, just like people do in real life. He speaks in short fragments instead of long, flowing paragraphs.

This dialogue shows who Babi is and feels similar to the way a real person would talk, while still remaining concise.

Dialogue Example #3: How to Simplify Your Dialogue Tags

Here’s an example of effective dialogue tags in Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier.

In this passage, the narrator’s been caught exploring the forbidden west wing of her new husband’s house, and she’s trying to make excuses for being there.

“I lost my way,” I said, “I was trying to find my room.” “You have come to the opposite side of the house,” she said; “this is the west wing.” “Yes, I know,” I said. “Did you go into any of the rooms?” she asked me. “No,” I said. “No, I just opened a door, I did not go in. Everything was dark, covered up in dust sheets. I’m sorry. I did not mean to disturb anything. I expect you like to keep all this shut up.” “If you wish to open up the rooms I will have it done,” she said; “you have only to tell me. The rooms are all furnished, and can be used.” “Oh, no,” I said. “No. I did not mean you to think that.”

In this passage, the only dialogue tags Du Maurier uses are “I said,” “she said,” and “she asked.”

Even so, you can feel the narrator’s dread and nervousness. Her emotions are conveyed through what she actually says, rather than through the dialogue tags.

This is a splendid example of evocative speech that doesn’t need fancy dialogue tags to make it come to life.

Dialogue Example #4: How to Balance Speech with Action

Let’s look at a passage from The Princess Bride by William Goldman, where dialogue is melded with physical action.

With a smile the hunchback pushed the knife harder against Buttercup’s throat. It was about to bring blood. “If you wish her dead, by all means keep moving," Vizzini said. The man in black froze. “Better,” Vizzini nodded. No sound now beneath the moonlight. “I understand completely what you are trying to do,” the Sicilian said finally, “and I want it quite clear that I resent your behavior. You are trying to kidnap what I have rightfully stolen, and I think it quite ungentlemanly.” “Let me explain,” the man in black began, starting to edge forward. “You’re killing her!” the Sicilian screamed, shoving harder with the knife. A drop of blood appeared now at Buttercup’s throat, red against white.

In this passage, William Goldman brings our attention seamlessly from the action to the dialogue and back again.

This makes the scene twice as interesting, because we’re paying attention not just to what Vizzini and the man in black are saying, but also to what they’re doing.

This is a great way to keep tension high and move the plot forward.

Dialogue Example #5: How to Write Conversations with Subtext

This example from Ender’s Game by Orson Scott Card shows how to write dialogue with subtext.

Here is the scene when Ender and his sister Valentine are reunited for the first time, after Ender’s spent most of his childhood away from home training to be a soldier.

Ender didn’t wave when she walked down the hill toward him, didn’t smile when she stepped onto the floating boat slip. But she knew that he was glad to see her, knew it because of the way his eyes never left her face. “You’re bigger than I remembered,” she said stupidly. “You too,” he said. “I also remembered that you were beautiful.” “Memory does play tricks on us.” “No. Your face is the same, but I don’t remember what beautiful means anymore. Come on. Let’s go out into the lake.”

In this scene, we can tell that Valentine missed her brother terribly, and that Ender went through a lot of trauma at Battle School, without either of them saying it outright.

The conversation could have started with Valentine saying “I missed you,” but instead, she goes for a subtler opening: “You’re bigger than I remembered.”

Similarly, Ender could say “You have no idea what I’ve been through,” but instead he says, “I don’t remember what beautiful means anymore.”

We can deduce what each of these characters is thinking and feeling from what they say and from what they leave unsaid.

Dialogue Example #6: How to Show, Not Tell

Let’s look at an example from The Name of the Wind by Patrick Rothfuss. This scene is the story’s first introduction of the ancient creatures called the Chandrian.

“I didn’t know the Chandrian were demons,” the boy said. “I’d heard—” “They ain’t demons,” Jake said firmly. “They were the first six people to refuse Tehlu’s choice of the path, and he cursed them to wander the corners—” “Are you telling this story, Jacob Walker?” Cob said sharply. “Cause if you are, I’ll just let you get on with it.” The two men glared at each other for a long moment. Eventually Jake looked away, muttering something that could, conceivably, have been an apology. Cob turned back to the boy. “That’s the mystery of the Chandrian,” he explained. “Where do they come from? Where do they go after they’ve done their bloody deeds? Are they men who sold their souls? Demons? Spirits? No one knows.” Cob shot Jake a profoundly disdainful look. “Though every half-wit claims he knows...”

The three characters taking part in this conversation all know what the Chandrian are.

Imagine if Cob had said “As we all know, the Chandrian are mysterious demon-spirits.” We would feel like he was talking to us, not to the two other characters.

Instead, Rothfuss has all three characters try to explain their own understanding of what the Chandrian are, and then shoot each other’s explanations down.

When Cob reprimands Jake for interrupting him and then calls him a half-wit for claiming to know what he’s talking about, it feels like a realistic interaction.

This is a clever way for Rothfuss to introduce the Chandrian in a believable way.

Dialogue Example #7: How to Keep Your Dialogue Concise

Here’s an example of concise dialogue from The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger.

“Do you blame me for flunking you, boy?” he said. “No, sir! I certainly don’t,” I said. I wished to hell he’d stop calling me “boy” all the time. He tried chucking my exam paper on the bed when he was through with it. Only, he missed again, naturally. I had to get up again and pick it up and put it on top of the Atlantic Monthly. It’s boring to do that every two minutes. “What would you have done in my place?” he said. “Tell the truth, boy.” Well, you could see he really felt pretty lousy about flunking me. So I shot the bull for a while. I told him I was a real moron, and all that stuff. I told him how I would’ve done exactly the same thing if I’d been in his place, and how most people didn’t appreciate how tough it is being a teacher. That kind of stuff. The old bull.

Here, the last paragraph diverges from the prior ones. After the teacher says “Tell the truth, boy,” the rest of the conversation is summarized, rather than shown.

The summary of what the narrator says in the last paragraph—“I told him I was a real moron, and all that stuff”—serves to hammer home that this is the type of “old bull” that the narrator has fed to his teachers over and over before.

It doesn’t need to be shown because it’s not important to the narrator—it’s just “all that stuff.”

Salinger could have written out the entire conversation in dialogue, but instead he kept the dialogue concise.

Final Words

Now you know how to write clear, effective dialogue! Start with the basic rules for dialogue and try implementing the more advanced tips as you go.

What are your favorite dialogue tips? Let us know in the comments below.

Do you know how to craft memorable, compelling characters? Download this free book now:

Creating Legends: How to Craft Characters Readers Adore… or Despise!

This guide is for all the writers out there who want to create compelling, engaging, relatable characters that readers will adore… or despise., learn how to invent characters based on actions, motives, and their past..

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

Hannah Yang is a speculative fiction writer who writes about all things strange and surreal. Her work has appeared in Analog Science Fiction, Apex Magazine, The Dark, and elsewhere, and two of her stories have been finalists for the Locus Award. Her favorite hobbies include watercolor painting, playing guitar, and rock climbing. You can follow her work on hannahyang.com, or subscribe to her newsletter for publication updates.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

How to Write Interesting and Effective Dialogue

- Homework Tips

- Learning Styles & Skills

- Study Methods

- Time Management

- Private School

- College Admissions

- College Life

- Graduate School

- Business School

- Distance Learning

- M.Ed., Education Administration, University of Georgia

- B.A., History, Armstrong State University

Writing verbal conversations or dialogue is often one of the trickiest parts of creative writing. Crafting effective dialogue within the context of a narrative requires much more than following one quote with another. With practice, though, you can learn how to write natural-sounding dialogue that is creative and compelling.

The Purpose of Dialogue

Put simply, dialogue is narrative conveyed through speech by two or more characters. Effective dialogue should do many things at once, not just convey information. It should set the scene, advance action, give insight into each character, and foreshadow future dramatic action.

Dialogue doesn't have to be grammatically correct; it should read like actual speech. However, there must be a balance between realistic speech and readability. Dialogue is also a tool for character development. Word choice tells a reader a lot about a person: their appearance, ethnicity, sexuality, background, even morality. It can also tell the reader how the writer feels about a certain character.

How to Write Direct Dialogue

Speech, also known as direct dialogue, can be an effective means of conveying information quickly. But most real-life conversations are not that interesting to read. An exchange between two friends may go something like this:

"Hi, Tony," said Katy.

"Hey," Tony answered.

"What's wrong?" Katy asked.

"Nothing," Tony said.

"Really? You're not acting like nothing's wrong."

Pretty tiresome dialogue, right? By including nonverbal details in your dialogue, you can articulate emotion through action. This adds dramatic tension and is more engaging to read. Consider this revision:

"Hi, Tony."

Tony looked down at his shoe, dug in his toe and pushed around a pile of dust.

"Hey," he replied.

Katy could tell something was wrong.

Sometimes saying nothing or saying the opposite of what we know a character feels is the best way to create dramatic tension. If a character wants to say "I love you," but his actions or words say "I don't care," the reader will cringe at the missed opportunity.

How to Write Indirect Dialogue

Indirect dialogue doesn't rely on speech. Instead, it uses thoughts, memories, or recollections of past conversations to reveal important narrative details. Often, a writer will combine direct and indirect dialogue to increase dramatic tension, as in this example:

Katy braced herself. Something was wrong.

Formatting and Style

To write dialogue that is effective, you must also pay attention to formatting and style. Correct use of tags, punctuation , and paragraphs can be as important as the words themselves.

Remember that punctuation goes inside quotations. This keeps the dialogue clear and separate from the rest of the narrative. For example: "I can't believe you just did that!"

Start a new paragraph each time the speaker changes. If there is action involved with a speaking character, keep the description of the action within the same paragraph as the character's dialogue.

Dialogue tags other than "said" are best used sparingly, if at all. Often a writer uses them to try to convey a certain emotion. For example:

"But I don't want to go to sleep yet," he whined.

Instead of telling the reader that the boy whined, a good writer will describe the scene in a way that conjures the image of a whining little boy:

He stood in the doorway with his hands balled into little fists at his sides. His red, tear-rimmed eyes glared up at his mother. "But I don't want to go to sleep yet."

Practice Makes Perfect

Writing dialogue is like any other skill. It requires constant practice if you want to improve as a writer. Here are a few tips to help you prepare to write effective dialogue.

- Start a dialogue diary. Practice speech patterns and vocabulary that may be foreign to you. This will give you the opportunity to really get to know your characters.

- Listen and take notes. Carry a small notebook with you and write down phrases, words, or whole conversations verbatim to help develop your ear.

- Read. Reading will hone your creative abilities. It will help familiarize you with the form and flow of narration and dialogue until it becomes more natural in your own writing.

- How to Write a Good Descriptive Paragraph

- Dialogue Definition, Examples and Observations

- What Are Reporting Verbs in English Grammar?

- Definition and Examples of Narratives in Writing

- Writing a Lead or Lede to an Article

- How to Write a Narrative Essay or Speech

- Constructed Dialogue in Storytelling and Conversation

- Writing the Parts of a Stage Play Script

- What Are the Parts of a Short Story? (How to Write Them)

- Reported Speech

- Foreshadowing in Narratives

- Ellipsis: Definition and Examples in Grammar

- detail (composition)

- How to Read Shakespeare Dialogue Aloud

- How to Write a Personal Narrative

Looking to publish? Meet your dream editor, designer and marketer on Reedsy.

Find the perfect editor for your next book

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Sep 21, 2023

How to Write Fabulous Dialogue [9 Tips + Examples]

This post is written by author, editor, and bestselling ghostwriter Tom Bromley. He is the instructor of Reedsy's 101-day course, How to Write a Novel .

Good dialogue isn’t about quippy lines and dramatic pauses.

Good dialogue is about propelling the story forward, pulling the reader along, and fleshing out characters and their dynamics in front of readers. Well-written dialogue can take your story to a new level — you just have to unlock it.

In this article, I’ll break down the major steps of writing great dialogue, and provide exercises for you to practice your own dialogue on.

Here's how to write great dialogue in 9 steps:

1. Use quotation marks to signal speech

2. pace dialogue lines by three , 3. use action beats , 4. use ‘said’ as a dialogue tag , 5. write scene-based dialogue, 6. model any talk on real life , 7. differentiate character voices, 8. "show, don't tell" information in conversation , 9. delete superfluous words, which dialogue tag are you.

Find out in just a minute.

Alfred Hitchcock once said, “Drama is life with all the boring bits cut out.”

Similarly, I could say that good dialogue in a novel is a real conversation without all the fluff — and with quotation marks.

Imagine, for instance, if every scene with dialogue in your novel started out with:

'Hey, buddy! How are you doing?"

“Great! How are you?""

'Great! Long time no see! Parking was a nightmare, wasn’t it?"

Firstly, from a technical perspective, the quotation marks are inconsistent and incorrectly formatted. To learn about the mechanics of your dialogue and how to format it, we also wrote this full post on the topic that I recommend reading.

Secondly, from a novel perspective, such lines don’t add anything to the story. And finally, from a reading perspective, your readers will not want to sit through this over and over again. Readers are smart: they can infer that all these civilities occur. Which means that you can skip the small talk (unless it’s important to the story) to get to the heart of the dialogue from the get-go.

For a more tangible example of this technique, check out the dialogue-driven opening to Barbara Kingsolver's novel, Unsheltered .

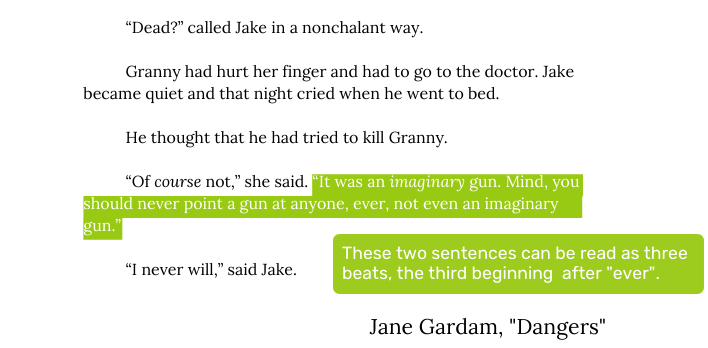

Screenwriter Cynthia Whitcomb once proposed an idea called the “Three-Beat Rule.” What this recommends, essentially, is to introduce a maximum of three dialogue “beats” (the short phrases in speech you can say without pausing for breath) at a time. Only after these three dialogue beats should you insert a dialogue tag, action beat, or another character’s speech.

Here’s an example from Jane Gardam’s short story, “Dangers”, in which the boy Jake is shooting an imaginary gun at his grandmother:

In theory, this sounds simple enough. In practice, however, it’s a bit more complicated than that, simply because dialogue conventions continue to change over time. There’s no way to condense “good dialogue” into a formula of three this, or two that. But if you’re just starting out and need a strict rule to help you along, then the Three-Beat Rule is a good place to begin experimenting.

FREE COURSE

How to Write Believable Dialogue

Master the art of dialogue in 10 five-minute lessons.

Let’s take a look at another kind of “beats” now — action beats.

Action beats are the descriptions of the expressions, movements, or even internal thoughts that accompany the speaker’s words. They’re always included in the same paragraph as the dialogue, so as to indicate that the person acting is also the person speaking.

On a technical level, action beats keep your writing varied, manage the pace of a dialogue-heavy scene, and break up the long list of lines ending in ‘he said’ or ‘she said’.

But on a character level, action beats are even more important because they can go a level deeper than dialogue and illustrate a character’s body language.

When we communicate, dialogue only forms a half of how we get across what we want to say. Body language is that missing half — which is why action beats are so important in visualizing a conversation, and can help you “show” rather than “tell” in writing.

Here’s a quick exercise to practice thinking about body language in the context of dialogue: imagine a short scene, where you are witnessing a conversation between two people from the opposite side of a restaurant or café. Because it’s noisy and you can’t hear what they are saying, describe the conversation through the use of body language only.

Remember, at the end of the day, action beats and spoken dialogue are partners in crime. These beats are a commonly used technique so you can find plenty of examples — here’s one from Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro .

If there’s one golden rule in writing dialogue, it’s this: ‘said’ is your friend.

Yes, ‘said’ is nothing new. Yes, ‘said’ is used by all other authors out there already. But you know what? There’s a reason why ‘said’ is the king of dialogue tags: it works.

Pro-tip: While we cannot stress enough the importance of "said," sometimes you do need another dialogue tag. Download this free cheatsheet of 270+ other words for said to get yourself covered!

FREE RESOURCE

Get our Dialogue Tag Cheatsheet

Upgrade your dialogue with our list of 270 alternatives to “said.”

The thinking goes that ‘said’ is so unpretentious, so unassuming that it focuses readers’ attention on what’s most important on the page: the dialogue itself. As writer Elmore Leonard puts it:

“Never use a verb other than ‘said’ to carry dialogue. The line of dialogue belongs to the character; the verb is the writer sticking his nose in. But ‘said’ is far less intrusive than ‘grumbled,’ ‘gasped,’ ‘cautioned,’ ‘lied.’”

It might be tempting at times to turn towards other words for ‘said’ such as ‘exclaimed,’ or ‘declared,’ but my general rule of thumb is that in 90% of scenarios, ‘said’ is going to be the most effective dialogue tag for you to use while writing dialogue.

So now that we have several guidelines in place, this is a good spot to pause, reflect, and say that there’s no wrong or right way to write dialogue. It depends on the demands of the scene, the characters, and the story. Great dialogue isn’t about following this or that rule — but rather learning what technique to use when .

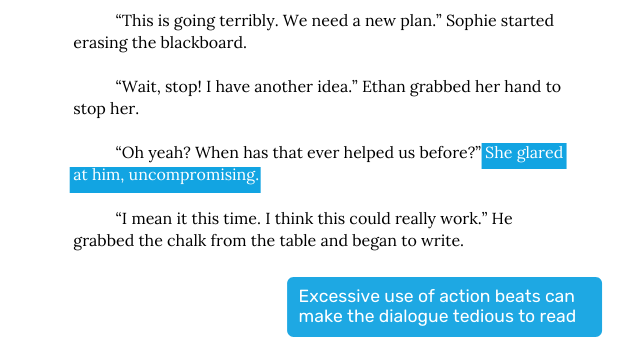

If you stick to one rule the whole time — i.e. if you only use ‘said,’ or you finish every dialogue line with an action beat — you’ll wear out readers. Let’s see how unnaturally it plays out in the example below with Sophie and Ethan:

All of which is to say: don’t be afraid to make exceptions to the rule if the scene asks for it. The key is to know when to switch up your dialogue structure or use of dialogue tags or action beats throughout a scene — and by extension, throughout your book.

Tell us about your book, and we'll give you a writing playlist

It'll only take a minute!

Dialogue isn’t always about writing grammatically perfect prose. The way a person speaks reflects the way a person is — and not all people are straight-A honor students who speak in impeccable English. In real life, the way people talk is fragmented, and punctuated by pauses.

That’s something that you should also keep in mind when you’re aiming to write authentic dialogue.

It can be tempting to think to yourself, “ Oh, I’ll try and slip in some exposition into my dialogue here to reveal important background information.” But if that results in an info-dump such as this — “ I’m just going to the well, Mother — the well that my brother, your son, tragically fell down five years ago ” — then you’ll probably want to take a step back and find a more organic, timely, and digestible way to incorporate that into your story.

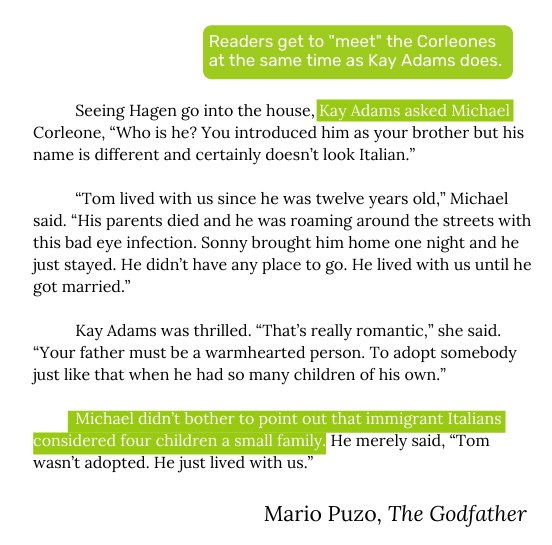

Kay Adams is Michael’s date at his sister’s wedding in this scene. Her interest in his family is natural enough that the expository conversation doesn’t feel shoehorned in.

A distinctive voice for each character is perhaps the most important element to get right in dialogue. Just as no one person in the world talks the same as each other, no one person in your book should also talk similarly.

To get this part of writing dialogue down pat, you need to start out by knowing your characters inside out. How does your character talk? Do they come with verbal quirks? Non-verbal quirks?

Jay Gatsby’s “old sport,” for example, gives him a distinctive, recognizable voice. It stands out because no one else has something as memorable about their speech. But more than that, it reveals something valuable about Gatsby’s character: he’s trying to impersonates a gentleman in his speech and lifestyle.

Likewise, think carefully about your character’s voice, and use catchphrases and character quirks when they can say something about your character.

Which famous author do you write like?

Find out which literary luminary is your stylistic soulmate. Takes one minute!

“Show, don’t tell” is one of the most oft-repeated rules in writing, and a conversation on the page can be a gold mine for “showing.”

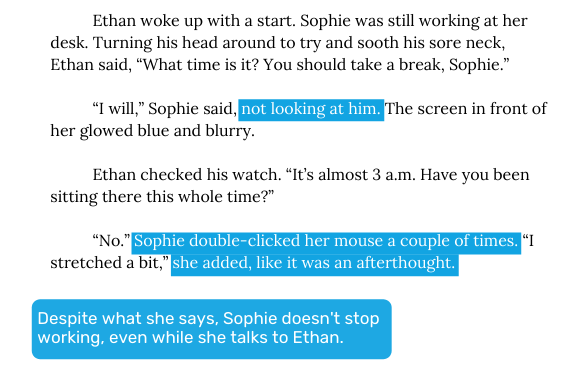

Authors can use action beats and descriptions to provide clues for readers to read between the lines. Let’s revisit Sophie and Ethan in this example:

While Sophie claims she hasn’t been obsessing over this project all night, the actions in between her words indicate there’s nothing on her mind but work. The result is that you show , through the action beats vs. the dialogue, Sophie being hardworking—rather than telling it.

Show, Don't Tell

Master the golden rule of writing in 10 five-minute lessons.

As always when it comes to writing a novel: all roads lead back to The Edit, and the dialogue you’ve written is no exception.

So while you’re editing your novel at the end, you may find that a “less is more” mentality will be helpful. Remember to cut out the unnecessary bits of dialogue, so that you can focus on making sure the dialogue you do keep matters. Good writing is intentional and purposeful, always striving to keep the story going and readers engaged. The importance lies in quality rather than quantity.

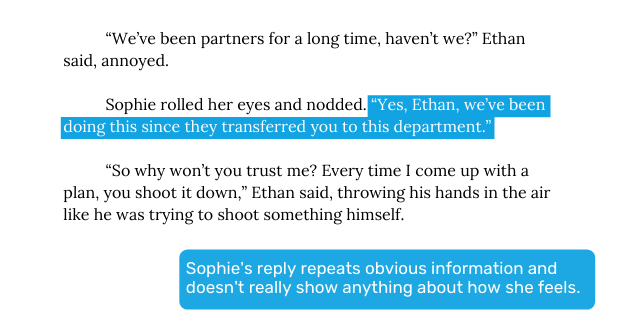

One point I haven’t addressed yet is repetition. If used well (i.e. with clear intention), repetition is a literary device that can help you build motifs in your writing. But when you find yourself repeating information in your dialogue, it might be a good time to revise your work.

For instance, here’s a scene with Sophie and Ethan later on in the story:

As I’ve mentioned before, good dialogue shows character — and dialogue itself is a playground where character dynamics play out. If you write and edit your dialogue with this in mind, then your dialogue will be sharper, cleaner, and more organic.

I know that writing dialogue can be intimidating, especially if you don’t have much experience with it. But that should never keep you from including it in your work! Just remember that the more you practice — especially with the help of these tips — the better you’ll get.

And once you’re confident with the conversational content you can conjure up, follow along to the next part of our guide to see how you can punctuate and format your dialogue flawlessly .

As an editor and publisher, Tom has worked on several hundred titles, again including many prize-winners and international bestsellers.

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

Catch your errors

Polish your writing in the *free* Reedsy Book Editor.

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Mentor Texts

Writing Dialogue: ‘The Missing Piece Son’

Considering the role of dialogue in a narrative, with an example from The Times’s Lives column to help.

By Katherine Schulten

Our new Mentor Text series spotlights writing from The Times that students can learn from and emulate.

This entry, like several others we are publishing, focuses on an essay from The Times’s long-running Lives column to consider skills prized in narrative writing. We are starting with this genre to help support students participating in our 2020 Personal Narrative Essay Contest .

Please note: For this contest, students are not required to include dialogue, but we suspect many will. We hope that demystifying it a bit here might encourage more students to try.

When should you include actual dialogue in a piece, and when should you simply report what was said? How can dialogue reveal character? How does it affect the pacing of a story? Does every narrative essay require dialogue?

Take a look at this mentor text, alongside a related text by the same author, to think about these questions and to experiment with dialogue in your own work.

Before Reading

Have you ever written dialogue before? Try it!

To prepare for the mentor text you are about to read, you might make it a conversation between two family members. You can work with a partner, each of you claiming one of the characters and all of his or her lines, or you can do it alone. You can write down a conversation you have actually had, or you can make one up.

Here are some possible scenarios, in case you need help getting started:

One character wants something and the other doesn’t.

The characters are in a fight.

The characters are avoiding talking about something.

The characters have just met and are getting to know each other.

The characters are experiencing something together — maybe they’re on a trip, cooking together, playing a game or at a party.

When you’re done, ask yourself, what was difficult about this task? What was easy (or even fun)? What additional questions about writing dialogue did this exercise raise for you?

Mentor Text: “ The Missing-Piece Son ” by Randa Jarrar

This essay centers on a conversation, as the opening lines tell you right away:

I don’t think anything would rattle the mother of a preteen boy quite like the words my 12-year-old uttered this spring: “Mom, we need to talk,” he said. “It’s something serious.”

There is a great deal to notice about how this writer uses dialogue, starting from this first sentence. For instance, why do you think she writes, “Mom, we need to talk,” he said. “It’s something serious.” rather than “Mom, we need to talk. It’s something serious,” he said ?

Here is the first paragraph in its entirety. Notice how the narrator tells you what her son says, but then immediately parses what it might mean:

I don’t think anything would rattle the mother of a preteen boy quite like the words my 12-year-old uttered this spring: “Mom, we need to talk,” he said. “It’s something serious.” The reversal of roles; the need for him to address me . The “serious” part. These were enough, in the very short time it took to follow him to his bedroom, to completely freak me out. He’d just returned to Michigan after visiting his father in New York. Had something catastrophic happened while he was there? Had he done drugs or had sex? I hoped he’d just left his iPod on the plane.

Read the full piece, paying close attention to who talks, what they say, and how the narrator continues this strategy of varying the spoken dialogue with her own thoughts.

For instance:

“We should think about this,” I said. “I’ve been thinking about it, Mom,” he said. “And I really want to.” Don’t go ! I thought. “Well, then you should do it,” I said. “Really, Mom? I can?” Please don’t ! “Absolutely.”

What is the effect of varying spoken conversation with thoughts about the conversation?

How does the writer help the reader keep track of who is talking? Does every line need what’s known as a dialogue tag — like “he said” and “she shouted” — after a character has spoken? What dialogue tags does this writer use? How does she help the reader understand what she’s thinking versus what is being said?

What do you learn about the son solely through what he says and how he says it? Imagine that this piece was told from the son’s point of view instead, and we had access to his thoughts as he spoke. How might this piece change? What do you imagine some of those thoughts might be?

What else do you notice about how dialogue works in this story? Does it help address any of the questions you had after you tried writing your own?

Now, take your study a bit further, and contrast what you just read with the related Lives essay, “ I Was 18 and Pregnant ,” also by Randa Jarrar.

What do you notice about how dialogue is used here? Why do you think the writer might have made different choices about its use in this piece? (Hint: How is “talk” — or lack thereof — a theme?)

What can you take away from the two essays together about when and how to include dialogue in a piece and when not to? Why?

Now Try This:

Take a fresh look at a narrative you’re working on, and see what you might borrow from this writer.

Are there places where you could tell your story more effectively through dialogue? Why? What can dialogue do in your piece that narration alone might not?

Are there places where a conversation is best simply described, or where only a line or two is needed? Why? How can you make the dialogue you add have the most impact?

Are there places where it might be useful to borrow the technique in “The Missing-Piece Son” and vary dialogue with the thoughts of a narrator? What could that add to the story?

Other Mentor Texts for Writing Dialogue

Below each title is an excerpt from the piece.

“ The Other Talk ,” a 2019 essay from the Rites of Passage column , by Shaquille Heath

In an earnest voice, he looked at me and said, “You’re black.” He said it so sternly that I thought that this remark may have been the end of the talk. “I’m sure you’ve already had encounters in life that tell you what this means,” he said, “but I want to talk to you about it.”

“ Arguing With God ,” a 2006 essay from a Times Magazine column called True-Life Tales, by Samantha M. Shapiro

“Forget about going to Boston next month,” my mother called to report. “The rabbi canceled Michael’s bar mitzvah.” “How is that possible?” I asked. “You know Michael’s a wild kid,” my mother said.

“ We Found Our Son in the Subway ,” a 2013 essay from the Opinion section’s Townies column, by Peter Mercurio

Danny called me that day, frantic. “I found a baby!” he shouted. “I called 911, but I don’t think they believed me. No one’s coming. I don’t want to leave the baby alone. Get down here and flag down a police car or something.”

“ The Man on Death Row Who Changed Me ,” a 2014 essay from the Lives column, by Bryan Stevenson

“I’m very sorry,” I blurted out. “I’m really sorry, I’m really sorry, uh, O.K., I don’t really know, uh, I’m just a law student, I’m not a real lawyer.”

“ When a Dating Dare Leads to Months of Soul Searching ,” a 2019 essay from the Modern Love column, by Andrew Lee

“If things don’t work out,” she said, “would it hurt your confidence?” “Hey, don’t worry about it,” I said. “I’ve got enough confidence for both of us. When my friends ask what happened, I’ll say, ‘She had everything going for her, but sometimes things get between people.’” I smiled. “‘Like racism.’”

Questions for Any Narrative Essay on Dialogue:

Where is dialogue used in this piece? Where is dialogue implied but not actually written out? (For example, “They talked about what happened in class that day and decided ...”) Who speaks and who doesn’t?

What do you notice about the places where the writer chooses to use dialogue? How does it advance the plot, deepen your understanding of a character, or emphasize a theme or idea? What do you learn through it? How would it be different if the writer did not use dialogue here, but just described a conversation instead?

Do the voices of each character sound distinct? How so? What do they tell you about those characters?

What else do you notice or admire about this essay? What lessons might it have for your own writing?

Writing Dialogue [20 Best Examples + Formatting Guide]

Have you ever found yourself cringing at clunky dialogue while reading a book or watching a movie? I know I have.

It’s like nails on a chalkboard, completely ruining the experience. But on the flip side, well-written dialogue can transform a story. It’s the magic that makes characters leap off the page, immersing us in their world.

As a writer, I’m fascinated by the mechanics of great dialogue.

So here are 20 of the best examples of writing dialogue that brings your story to life.

Example 1: Dialogue that Reveals Character

Table of Contents

One of the most powerful functions of dialogue is to shed light on your characters’ personalities.

The way they speak – their word choice, tone, even their hesitations – can tell us so much about who they are. Check out this example:

“Look, I ain’t gonna sugarcoat this,” the detective growled, his knuckles whitening as he gripped the chair. “You were spotted leaving the scene, and the murder weapon’s got your prints all over it.”

Without any lengthy description, we get a sense of this detective as a no-nonsense, direct type of guy.

Example 2: Dialogue that Builds Tension

Dialogue can become this amazing tool to ratchet up the tension in a scene.

Short, clipped exchanges and carefully placed silences can leave the reader on the edge of their seat.

Here’s how it might play out:

“Do you hear that?” Sarah whispered. “Hear what?” A scratching noise echoed from the attic. Sarah’s eyes widened. “It’s coming back.”

The suspense is killing me just writing that!

Example 3: Dialogue that Drives the Plot

Conversations aren’t just about characters sitting around and chatting.

Great dialogue should actively push the story forward. It can set up a conflict, reveal key information, or change the course of events.

Take a look at this:

“I’ve made my decision,” the king declared, the crown heavy on his brow. “We go to war.”

A single line, and the whole trajectory of the story shifts.

Formatting Tips: The Basics

Now, before we get carried away, let’s cover some essential dialogue formatting rules.

Think of these as the grammar of a good conversation.

- Quotation Marks: Yep, those little squiggles are your best friend. They signal to the reader: “Hey! Someone’s talking!”

- New Speaker, New Paragraph: Whenever a different character starts talking, give them a new paragraph. It’s all about keeping things easy to follow.

- Dialogue Tags: These are the little phrases like “he said” or “she replied.” Use them, but try not to overuse them. A well-placed action beat can often do a better job of showing who’s speaking.

Example 4: Dialogue that Creates Humor

Dialogue can be ridiculously funny when done well.

The key? Snappy exchanges, playful misunderstandings, and just a dash of absurdity. Consider this:

“I saw the weirdest thing at the grocery store today,” Tom said, “A woman arguing with a head of lettuce.” “Was she winning?” Lily asked, a grin playing on her lips.

You can almost hear the deadpan delivery, can’t you?

Example 5: Dialogue that Shows Relationships

The way characters speak to each other says a ton about the dynamics between them.

Is there warmth, hostility, an underlying power struggle? Dialogue can paint a crystal-clear picture. Imagine this exchange:

“You didn’t do the dishes again?” Sarah sighed, hands planted on her hips. “Aw, c’mon babe. I was busy,” Mike whined, avoiding her gaze.

We instantly sense the long-suffering tone from Sarah and the playful guilt from Mike.

Example 6: Dialogue with Subtext

The most interesting dialogue often has layers. What the characters say might not be exactly what they mean.

This is where subtext comes in – the unspoken thoughts and feelings bubbling beneath the surface.

Take this snippet:

“It’s a nice ring,” Emily said, her voice flat. “You don’t like it?” Mark’s brow furrowed. Emily shrugged. “It’s fine.”

Is Emily truly indifferent? Or is she masking disappointment, perhaps a sense of something not being quite right? Subtext makes us read between the lines.

Formatting Tips: Getting Fancy

Now, let’s spice things up with a few more advanced formatting tricks:

- Ellipses (…): These little dots are perfect for showing a character trailing off, hesitating, or searching for words. Example: “I…I don’t know what to say.”

- Em Dashes (—): These guys can interrupt a thought or indicate a sudden change in direction. Example: “I was going to apologize, but then — well, you’re still being a jerk.”

- Internal Dialogue: Instead of quotation marks, sometimes you’ll want to italicize a character’s inner thoughts. Example: Why did I say that? I’m such an idiot.

Cautionary Note

It’s important to remember: dialogue shouldn’t feel like an interrogation. Avoid rigid “question-answer, question-answer” patterns. Real conversations flow and meander naturally.

Example 7: Dialogue with Dialects and Accents

Regional dialects and accents can bring so much flavor to your characters, but it’s a delicate balance.

You want to add authenticity without it becoming a caricature or making it hard to understand.

Here’s a subtle example:

“Well, I’ll be darned,” drawled the farmer, squinting at the sky. “Looks like a storm’s brewin’.”

Notice how just a few word choices and a slight change in pronunciation hint at the speaker’s background.

Example 8: Dialogue in Groups

Writing conversations with more than two people can get chaotic fast. The key is clarity.

Here are a few tips:

- Strong Dialogue Tags: Sometimes, you need to be more specific than just “he said” or “she said”. Example: “Don’t be ridiculous,” scoffed Sarah.

- Action Beats: Break up chunks of dialogue with actions that show who’s speaking. Example: Tom slammed his fist on the table. “I won’t stand for this!”

Example 9: Dialogue Over the Phone (or Other Technology)

Conversations where characters aren’t physically together pose unique challenges.

You can’t rely on body language cues. Instead, focus on conveying tone and potential misunderstandings.

For instance:

“Hello?” Sarah’s voice crackled through the phone. A long pause. “Sarah, is that you?” “Mom? Why are you whispering?”

Instantly there’s a sense of distance and something not being quite right.

Example 10: Inner Monologue with a Twist

We often think of internal dialogue as a single character reflecting, but sometimes our inner voices can argue.

This can be a powerful way to showcase internal conflict.

Here’s how it might look:

You should just tell him how you feel, one voice chimed. Are you crazy? the other shrieked back. He’ll never feel the same way .

This creates a vivid picture of a character torn between opposing desires.

Example 11: Dialogue With a Manipulative Character

Manipulative characters often use language as a weapon.

They might use guilt trips, flattery, or veiled threats to get what they want.

Consider this:

“After everything I’ve done for you…” The old woman sighed, a flicker of disappointment in her eyes. “Well, I guess I shouldn’t expect gratitude.”

Notice how she doesn’t directly ask for anything, instead hinting at a debt, leaving the listener feeling uneasy and obligated.

Example 12: Dialogue Across Time Periods

If you’re writing historical fiction or anything with time travel elements, you’ll need to capture the distinct speech patterns of different eras.

Imagine this exchange:

“Gadzooks! What manner of contraption is this?” The Victorian gentleman exclaimed, staring in bewilderment at the smartphone. “It’s a phone,” the teenager replied, barely suppressing a laugh. “Let me show you.”

This little snippet highlights the potential for both humor and linguistic challenges when worlds collide.

Formatting Tip: Dialogue Without Tags

Sometimes, for a rapid-fire or dreamlike effect, you might want to ditch the “he said” or “she asked” altogether.

It’s a bold move, but it can be effective if done sparingly.

Check this out:

“Where are you going?” “Away.” “When will you be back?” “I don’t know.” “Please don’t leave me.”

This creates a sense of urgency, the raw exchange forcing us to focus solely on the words themselves.

Example 13: Dialogue that Shows Transformation

A great way to showcase how a character develops is through shifts in how they speak.

Maybe they become bolder, quieter, or their vocabulary changes.

Let’s see an example:

Scene 1: “I-I don’t know,” Emily whimpered, cowering in the corner. Scene 2 (Later in the story): “That’s it. I’m not taking this anymore!” Emily declared, her chin held high.

The dialogue itself reflects her transformation from victim to someone ready to stand up for herself.

Example 14: Dialogue that’s Just Plain Weird

It’s okay to get strange sometimes.

Absurdist humor or unsettling conversations can add a unique flavor to your story. Just be sure it fits the overall tone.

“Do you believe in cucumbers?” the man asked, his eyes wide and unblinking. “Excuse me?” “Cucumbers, my dear. Agents of the underground vegetable kingdom.”

This immediately creates a sense of oddness and perhaps a touch of unease. Is this guy crazy, or is there something more going on?

Example 15: Dialogue with a Purpose

Remember, good dialogue isn’t just about being entertaining.

It should move your story along. Here are some functions dialogue can serve:

- Providing Exposition: Sometimes, you need to inform the reader of backstory or world-building details. Trickle information through natural conversation rather than an information dump.

- Foreshadowing: Subtle hints within a conversation can foreshadow future events or create a sense of unease for the reader.

- Revealing a Twist: A single line of dialogue can completely flip the script and reframe everything that came before.

Example 16: Dialogue with Non-Verbal Elements

So much of communication happens beyond just words.

Sighs, laughs, and gestures can add richness to dialogue on the page.

“I’m fine,” she said, crossing her arms and looking away.

Notice how the body language contradicts her words, hinting at inner turmoil.

Example 17: Silence as Dialogue

Sometimes, what isn’t said is the most powerful thing of all.

A pregnant pause or a character refusing to speak can convey volumes.

Imagine this:

“So, will you help me or not?” Tom pleaded. Sarah stared at him, her lips a thin line. Finally, she turned and walked away.

The lack of a verbal response speaks louder than any words could.

Example 18: Dialogue With Humorous Effect

A well-timed O.S. voice can deliver a funny remark or punchline, undercutting the seriousness of a scene or taking a moment in an unexpected comedic direction.

INT. CLASSROOM – DAY The teacher drones on about the causes of the American Revolution, his voice as dull as the worn textbook in front of him. KEVIN tries to stifle his yawns, failing miserably. STUDENT (O.S.) Is he ever going to stop talking? My brain just turned to mush. Snickers ripple through the class. The teacher pauses, a look of annoyance flickering across his face. Kevin shoots a desperate look towards the source of the O.S. voice.

- Timing is everything. The best comedic O.S. lines act as a witty reaction to something else happening in a scene. The student’s comment comes right as Kevin’s boredom peaks.

- Subverting expectations is funny. The audience expects the scene to continue with a stern reprimand for speaking out of turn, but the script doesn’t give us that. This leaves room for further humor.

- Consider the tone of the voice – sarcastic, matter-of-fact, or outright whiny? This adds to the comedic effect.

Example 19: Dialogue With Unexpected Reveals

Think of this as a surprise twist using O.S. dialogue.

The audience (and maybe even some characters) are led to believe one thing, only for an O.S. voice to reveal something completely unexpected, shifting the scene’s dynamic.

INT. POLICE INTERROGATION ROOM – NIGHTDETECTIVE HARRIS paces in front of a nervous SUSPECT. Photos of the crime scene are scattered on the table. HARRIS Don’t lie to me! We’ve got witnesses who saw you at the scene. SUSPECT I – I swear, I had nothing to do with it! I was… I was with my girlfriend. Harris leans in, a triumphant glint in her eyes. She claps her hands sharply, startling the suspect. WOMAN (O.S.) That’s a lie! He was nowhere near me last night! The suspect whips around. His face pales as we hear the sound of the interrogation room door swinging open…

- The power lies in the build-up. The initial dialogue and the characters’ reactions should lead the audience to believe one outcome, making the O.S. interruption all the more impactful.

- Consider who speaks the O.S. line. Is it someone the audience recognizes, or a totally new character whose identity becomes a new mystery?

- Play with the proximity of the voice. Is it right outside the room, adding to the dramatic reveal as the door opens, or is it more distant – perhaps a voice over an intercom – for an even more unsettling effect?

Example 20: Dialogue With a “Haunted” Feeling

Explanation: O.S. can be used to create an eerie or unsettling atmosphere, particularly in horror or psychological thrillers. This could be unexplained voices, creepy whispers, or sounds that hint at a supernatural (or simply unnerving) presence.

INT. OLD MANSION – NIGHTSARAH explores the abandoned mansion, flashlight cutting through the thick dust. Cobwebs cling to every surface. A faint WHISPER drifts through the air, seeming to come from everywhere at once. Sarah freezes. VOICE (O.S.) Get out… leave this place… Sarah’s breath catches in her throat. She hesitantly follows the direction of the voice, her flashlight beam trembling.

- Less is more. The vaguer and more inexplicable the O.S. voice, the more chilling it becomes.

- Layer sounds for a full creepy effect. Combine whispers with unexpected bangs, creaks, or the faint sound of footsteps following behind Sarah.

- Play with audience expectations. If the script initially leads the audience to think the house is merely abandoned, the O.S. voices become that much more terrifying.

Here is a good video about writing dialogue:

Additional Dialogue Tips & Tricks

- Read Your Dialogue Aloud: This is the best way to catch awkward phrasing or unnatural rhythms. Our ears often pick up on what our eyes might miss.

- Less is More: Don’t feel the need to have every single interaction be profound. Sometimes a simple “Hey” or “Thanks” can do the job just fine.

- Eavesdrop: Paying attention to real-life conversations is fantastic research. Note the pauses, the filler words, the way people interrupt each other.

Final Thoughts: Writing Dialogue

Phew! We did it!

Does that feel like a solid collection of dialogue examples? We haven’t covered absolutely every scenario, but I hope these illustrate the vast potential within dialogue to bring your stories to life.

Read This Next:

- How To Use Action Tags in Dialogue: Ultimate Guide

- How Do Writers Fill a Natural Pause in Dialogue? [7 Crazy Effective Ways]

- Can You Start a Novel with Dialogue?

- How To Write A Southern Accent (17 Tips + Examples)

- How to Write a French Accent (13 Best Tips with Examples)

- How-To Guides

How To Write Dialogue In A Story (With Examples)

One of the biggest mistakes made by writers is how they use dialogue in their stories. Today, we are going to teach you how to write dialogue in a story using some easy and effective techniques. So, get ready to learn some of the best techniques and tips for writing dialogue!

There are two main reasons why good dialogue is so important in works of fiction. First, good dialogue helps keep the reader interested and engaged in the story. Second, it makes your work easier to write, read and understand. So, if you want to write dialogue that is interesting, engaging and easy to read, keep on reading. We will be teaching you the best techniques and tips for writing dialogue in a story.

Internal vs External Dialogue

Direct vs indirect dialogue, 20 tips for formatting dialogue in stories, step 1: use a dialogue outline, step 2: write down a script, step 3: edit & review your script, step 4: sprinkle in some narrative, step 5: format your dialogue, what is dialogue .

Dialogue is the spoken words that are spoken between the characters of a story. It is also known as the conversation between the characters. Dialogue is a vital part of a story. It is the vehicle of the characters’ thoughts and emotions. Good dialogue helps show the reader how the characters think and feel. It also helps the reader better understand what is happening in the story. Good dialogue should be interesting, informative and natural.

In a story, dialogue can be expressed internally as thoughts, or externally through conversations between characters. A character thinking to themself would be considered internal dialogue. Here there is no one else, just one character thinking or speaking to themselves:

Mary thought to herself, “what if I can do better…”

While two or more characters talking to each other in a scene would be an external dialogue:

“Watch out!” cried Sam. “What’s wrong with you?” laughed Kate.

In most cases, the words spoken by your character will be inside quotation marks. This is called direct dialogue. And then everything outside the quotation marks is called narrative:

“What do you want?” shrieked Penelope as she grabbed her notebooks. “Oh, nothing… Just checking if you needed anything,” sneered Peter as he tried to peek over at her notes.

Indirect dialogue is a summary of your dialogue. It lets the reader know that a conversation happened without repeating it exactly. For example:

She was still fuming from last night’s argument. After being called a liar and a thief, she had no choice but to leave home for good.

Direct dialogue is useful for quick conversations, while indirect dialogue is useful for summarising long pieces of dialogue. Which otherwise can get boring for the reader. Writers can combine both types of dialogue to increase tension and add drama to their stories.

Now you know some of the different types of dialogue in stories, let’s learn how to write dialogue in a story.

Here are the main tips to remember when formatting dialogue in stories or works of fiction:

- Always use quotation marks: All direct dialogue is written inside quotation marks, along with any punctuation relating to that dialogue.

- Don’t forget about dialogue tags: Dialogue tags are used to explain how a character said something. Each tag has at least one noun or pronoun, and one verb indicating how the dialogue is spoken. For example, he said, she cried, they laughed and so on.

- Dialogue before tags: Dialogue before the dialogue tags should start with an uppercase. The dialogue tag itself begins with a lowercase.

- Dialogue after tags: Both the dialogue and dialogue tags start with an uppercase to signify the start of a conversation. The dialogue tags also have a comma afterwards, before the first set of quotation marks.

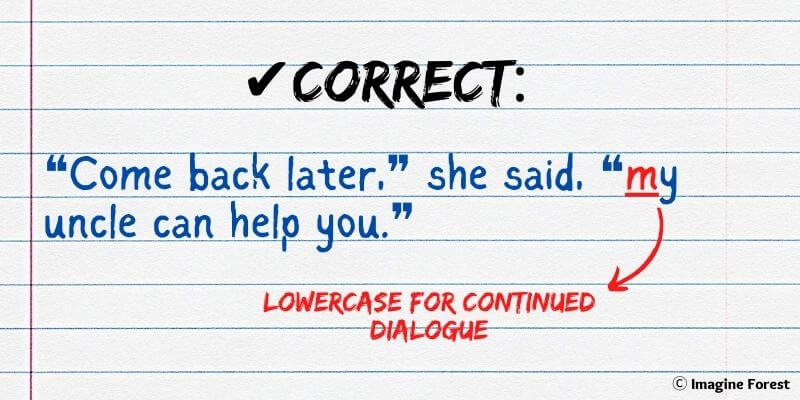

- Lowercase for continued dialogue: If the same character continues to speak after the dialogue tags or action, then this dialogue continues with a lowercase.

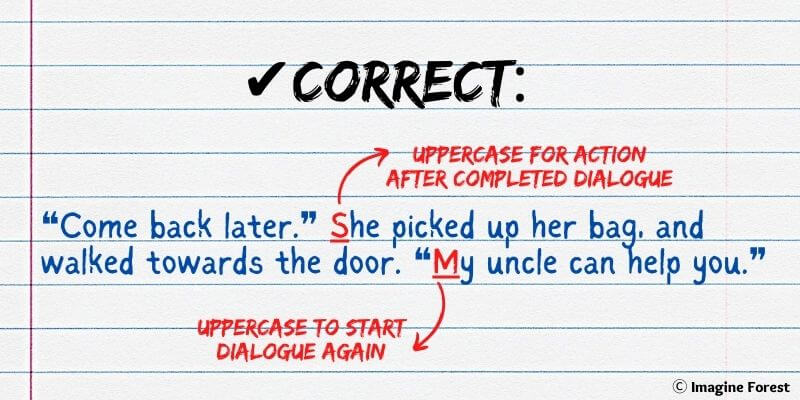

- Action after complete dialogue: Any action or narrative text after completed dialogue starts with an uppercase as a new sentence.

- Action interrupting dialogue: If the same character pauses their dialogue to do an action, then this action starts with a lowercase.

- Interruptions by other characters: If another character Interrupts a character’s dialogue, then their action starts with an uppercase on a new line. And an em dash (-) is used inside the quotation marks of the dialogue that was interrupted.

- Use single quotes correctly: Single quotes mean that a character is quoting someone else.

- New paragraphs equal new speaker: When a new character starts speaking, it should be written in a new paragraph.

- Use question marks correctly: If the dialogue ends with a question mark, then the part after the dialogue should begin with a lowercase.

- Exclamation marks: Similar to question marks, the next sentence should begin with a lowercase.

- Em dashes equal being cut off: When a character has been interrupted or cut off in the middle of their speech, use an em dash (-).

- Ellipses mean trailing speech: When a character is trailing off in their speech or going on and on about something use ellipses (…). This is also good to use when a character does not know what to say.

- Spilt long dialogue into paragraphs: If a character is giving a long speech, then you can split this dialogue into multiple paragraphs.

- Use commas appropriately: If it is not the end of the sentence then end the dialogue with a comma.

- Full stops to end dialogue: Dialogue ending with a full stop means it is the end of the entire sentence.

- Avoid fancy dialogue tags: For example, ‘he moderated’ or ‘she articulated’. As this can distract the reader from what your characters are actually saying and the content of your story. It’s better to keep things simple, such as using he said or she said.

- No need for names: Avoid repeating your character’s name too many times. You could use pronouns or even nicknames.

- Keep it informal: Think about how real conversations happen. Do people use technical or fancy language when speaking? Think about your character’s tone of voice and personality, what would they say in a given situation?

Remember these rules, and you’ll be able to master dialogue writing in no time!

How to Write Dialogue in 5 Steps

Dialogue is tricky. Follow these easy steps to write effective dialogue in your stories or works of fiction:

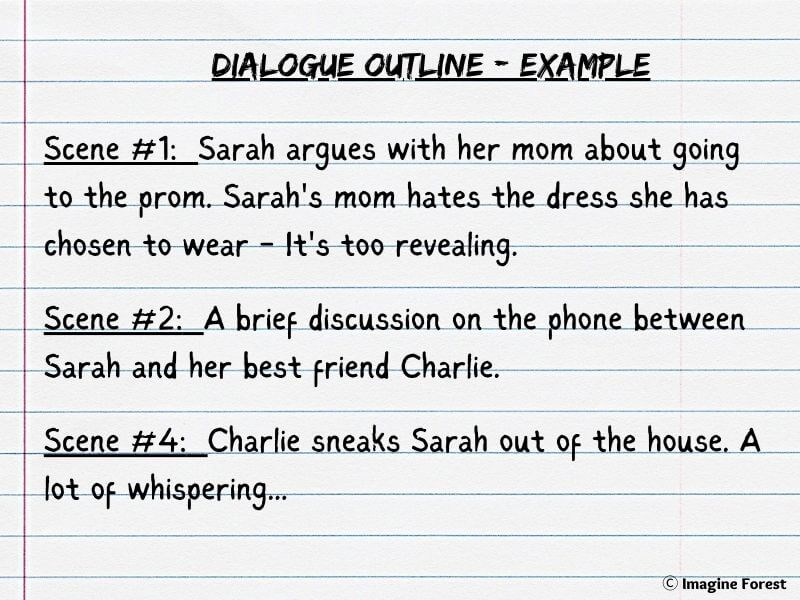

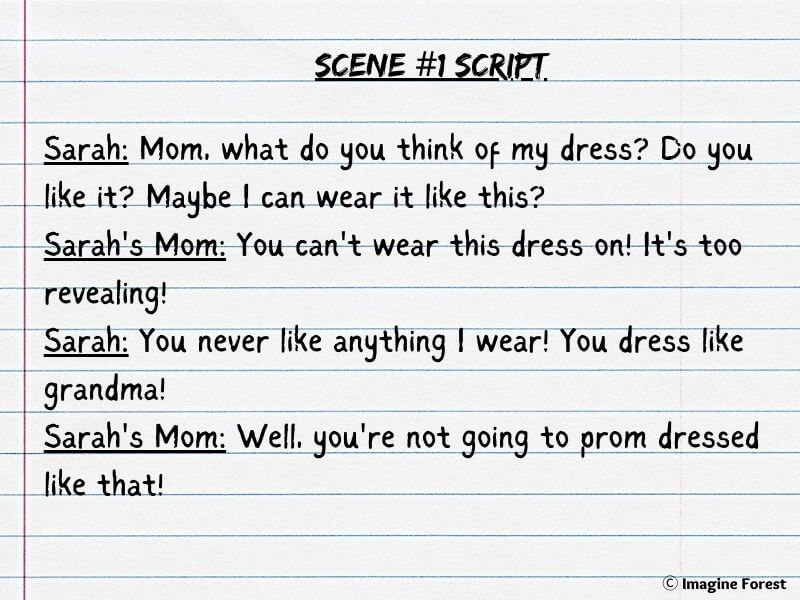

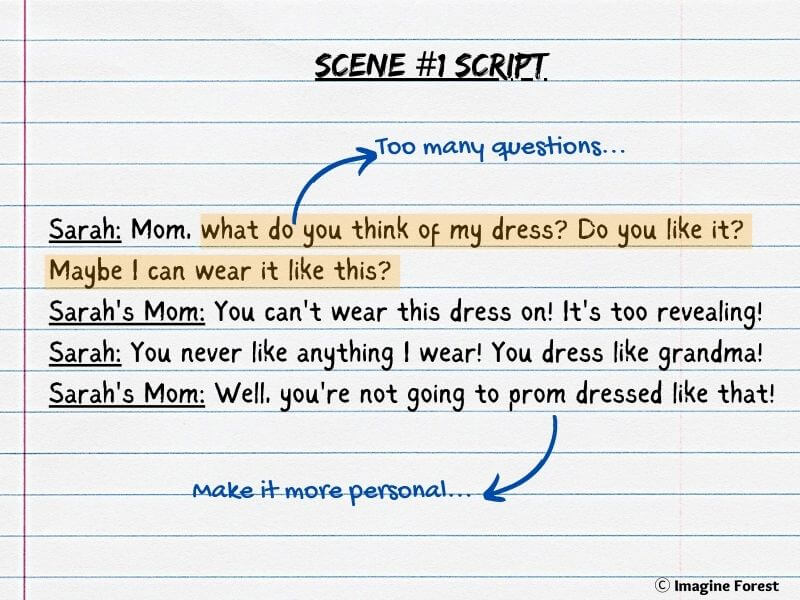

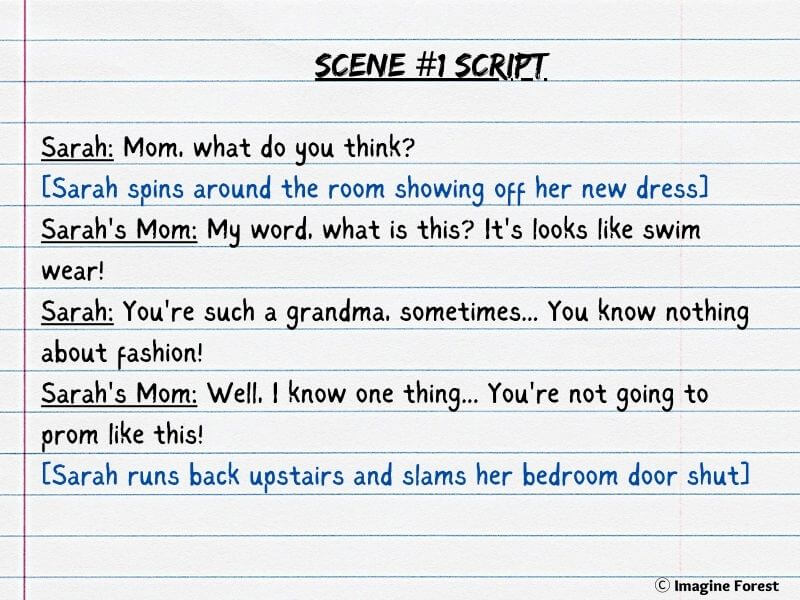

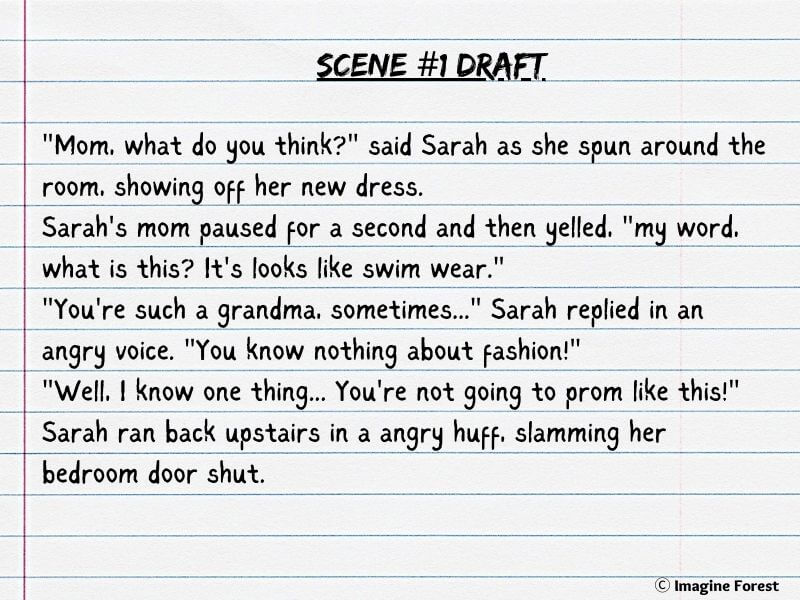

A dialogue outline is a draft of what your characters will say before you actually write the dialogue down. This draft can be in the form of notes or any scribblings about your planned dialogue. Using your overall book outline , you can pinpoint the areas where you expect to see the most dialogue used in your story. You can then plan out the conversation between characters in these areas.

A good thing about using a dialogue outline is that you can avoid your characters saying the same thing over and over again. You can also skim out any unnecessary dialogue scenes if you think they are unnecessary or pointless.

Here is an example of a dialogue outline for a story: