- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Introspection and How It Is Used In Psychology Research

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amanda Tust is a fact-checker, researcher, and writer with a Master of Science in Journalism from Northwestern University's Medill School of Journalism.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Amanda-Tust-1000-ffe096be0137462fbfba1f0759e07eb9.jpg)

Thomas Barwick / Getty Images

- Improvement Tips

Introspection is a psychological process that involves looking inward to examine one's own thoughts, emotions, judgments, and perceptions.

In psychology, introspection refers to the informal process of exploring one's own mental and emotional states. Although, historically, the term also applies to a more formalized process that was once used as an experimental technique . Learn more about uses for introspection, a few examples, and how to be more introspective.

Uses for Introspection

Introspection is important for several reasons. Among them are that it helps us engage in reflection, it assists with research, and it can be a valuable tool in mental health treatments involving psychotherapy.

One way to use introspection is for reflection, which involves consciously examining our internal psychological processes. When we reflect on our thoughts, emotions , and memories and examine what they mean, we are engaged in introspection.

Doing a reflective dive into our own psychology can help improve our levels of self-awareness. Being self-aware and gaining self-insight through the act of reflection is connected with higher levels of resilience and lower levels of stress . In this way, introspective reflection aids in personal growth.

Research Technique

The term introspection is also used to describe a research technique that was first developed by psychologist Wilhelm Wundt . Also known as experimental self-observation , Wundt's technique involved training people to carefully and objectively as possible analyze the content of their own thoughts.

Some historians suggest that introspection is not the most accurate term to refer to the methods that Wundt utilized. They contend that introspection implies a level of armchair soul-searching, but the methods that Wundt used were a much more highly controlled and rigid experimental technique.

In everyday use, introspection is a way of looking inward and examining one's internal thoughts and feelings. As a research tool, however, the process was much more controlled and structured.

Psychotherapy

Introspection can also be useful in psychotherapy sessions. When both practitioners and patients have the ability to be introspective, this aids in the development of the therapeutic relationship and can even affect treatment outcomes.

Engaging in introspection-based activities has been found beneficial for certain mental health conditions. For example, when people with depression engaged in emotional introspection, they were able to downregulate activity in their amygdala—an area of the brain associated with emotion regulation .

The term introspection can be used to describe both an informal reflection process and a more formalized experimental approach that was used early on in psychology's history. It's also used in psychotherapy sessions.

History of Introspection in Psychology

The process that Wundt used is what set his methods apart from casual introspection. In Wundt's lab, highly trained observers were presented with carefully controlled sensory events. Wundt believed that the observers needed to be in a state of high attention to the stimulus and in control of the situation. The observations were also repeated numerous times.

What was the purpose of these observations? Wundt believed that there were two key components that make up the contents of the human mind: sensations and feelings.

In order to understand the mind, Wundt believed that researchers needed to do more than simply identify its structure or elements. Instead, it was essential to look at the processes and activities that occur as people experience the world around them.

Wundt focused on making the introspection process as structured and precise as possible. Observers were highly trained and the process itself was rigid and highly controlled.

In many instances, respondents were asked to simply respond with a "yes" or "no." In some cases, observers pressed a telegraph key to give their response. The goal of this process was to make introspection as scientific as possible.

Edward Titchener , a student of Wundt's, also utilized this technique, although he has been accused of misrepresenting many of Wundt's original ideas. While Wundt was interested in looking at the conscious experience as a whole, Titchener instead focused on breaking down mental experiences into individual components and asked individuals to describe their mental experiences of events.

Benefits of Introspection

While introspection has fallen out of favor as a research technique, there are many potential benefits to this sort of self-reflection and self-analysis. Among them are:

- Introspection can be a great source of personal knowledge , enabling you to better recognize and understand what you're thinking and feeling. This leads to a higher level of self-awareness, which can help promote mental health and increase our happiness .

- The introspective process provides knowledge that is not possible in any other way ; there is no other process or approach that can provide this information. The only way to understand why you think or feel a certain way is through self-analysis or reflection.

- Introspection can help people make connections between different experiences and their responses . For example, when engaging in self-reflection after a disagreement with your spouse, you may recognize that you responded defensively because you felt belittled or disrespected.

- Introspection can improve our capacity for empathy . The more we understand ourselves, the easier it becomes to understand others. We're able to put ourselves "in their shoes" and empathize with how they may feel.

- Introspection makes us stronger leaders . While some believe that being a good leader requires self-confidence, others contend that self-awareness is more important. People who understand themselves internally are able to lead others effectively, also often making better decisions .

Drawbacks of Introspection

Introspection is not a perfect process. So, it can come with a few drawbacks.

People often give greater weight to introspection about themselves while judging others on their outward behavior. This can result in bias without recognizing that a bias exists.

Even when their introspections don't provide useful or accurate information, people often remain confident that their interpretations are correct. This is a phenomenon known as the introspection illusion.

Cognitive biases are a good example of how people are often unaware of their own thoughts and biases. Despite this, people tend to be very confident in their introspections.

Bias can also exist during research studies using introspection. Because observers have to first be trained by researchers, there is always the possibility that this training introduces a bias to the results.

This bias can influence what they observe. Put another way, observers engaged in introspection might be thinking or feeling things because of how they have been influenced and trained by the experimenters.

Rumination involves obsessing over things or having them run through your mind over and over again. When trying to figure out the inner workings of the mind, one can end up ruminating on their "discoveries." This can have negative impacts mentally.

For example, in a study of adolescents with depression , researchers found that these teens tended to have maladaptive introspection with high levels of rumination, thus contributing to the worsening of their symptoms.

Subjectivity

While Wundt's experimental techniques did a great deal to advance psychology as a more scientific discipline, the introspective method had a number of notable limitations. One is that the process is subjective, making it impossible to examine or repeat the results.

When using introspection in research, different observers often provided significantly different responses to the exact same stimuli. Even the most highly trained observers were not consistent in their responses.

Limited Use

Another problem with introspection as a research technique is its limited use. Complex subjects such as learning, personality, mental disorders, and development are difficult or even impossible to study with this technique. This technique is also difficult to use with children and impossible to use with animals.

Because observers have to first be trained by researchers, there is always the possibility that this training introduces a bias to the results. Those engaged in introspection might be thinking or feeling things because of how they have been influenced and trained by the experimenters.

Examples of Introspection

Sometimes, seeing examples can help increase your understanding of a particular concept or idea. Some examples of introspection in everyday life include:

- Engaging in mindfulness activities designed to increase self-awareness

- Journaling your thoughts and feelings

- Practicing meditation to better understand your inner self

- Reflecting on a situation and how you feel about it

- Talking with a mental health professional while exploring your mental and emotional states

How to Be Introspective

If you want to be more introspective, there are a few things you can do to assist with this.

- Ask yourself "what" questions . When trying to figure out our thoughts and emotions, we often ask ourselves "why" we feel the way we do. However, research indicates that "what" questions are more effective for improving introspection. For instance, instead of asking why you feel sad, ask what makes you feel sad. This can help provide more insight into yourself internally.

- Be more mindful . Introspection is a thoughtful exploration of what you're thinking and feeling at the moment. This requires being present, or more mindful. Greater mindfulness can be achieved in many different ways, some of which include journaling and meditation.

- Expand your curiosity . Curiosity about your inner self can help you better understand your emotions, reflect on your past, and explore your identity and purpose. Get in touch with your curious side. With curiosity comes exploration, providing a clearer understanding of your psychological workings.

- Spend some time alone, doing nothing . If the world is always busy around you, it can be difficult to quiet your mind enough to explore its inner workings. Make time regularly to spend some time alone, removing all distractions in your surroundings. This can help create an environment in which you're able to do a deeper dive into your psychological processes.

The use of introspection as a tool for looking inward is an important part of self-awareness and is even used in psychotherapy as a way to help clients gain insight into their own feelings and behavior.

While Wundt's efforts contributed a great deal to the development and advancement of experimental psychology, researchers now recognize the numerous limitations and pitfalls of using introspection as an experimental technique.

Cowden RG, Meyer-Weitz A. Self-reflection and self-insight predict resilience and stress in competitive tennis . Soc Behav Personal . 2016;44(7):1133-1149. doi:10.2224/sbp.2016.44.7.1133

Brock AC. The History of Introspection Revisited . In: Clegg JW, editor. Self-Observation in the Social Sciences . London: Taylor & Francis; 2018:25-44. doi:10.4324/9781351296809-3

Anders A. Introspection and psychotherapy . SFU Res Bull . 2019. doi:10.15135/2019.7.2.55-70

Herwig U, Opialla S, Cattapan K, Wetter TC, Jäncke L, Brühl A. Emotion introspection and regulation in depression . Psychiat Res: Neuroimag . 2018;277:7-13. doi:10.1016/j.psychresns.2018.04.008

Hergenhahn B. An Introduction to the History of Psychology .

Pal M. Promoting mental health through self awareness among the disabled and non-disabled students at higher education level in North 24 paraganas . Int Res J Modern Eng Tech Sci . 2021;3(1):51-53.

Jubraj B, Barnett NL, Grimes L, Varia S, Chater A, Auyeung V. Why we should understand the patient experience: clinical empathy and medicines otimisation . Int J Pharm Pract . 2016;24(5):367-370. doi:10.1111/ijpp.12268

Zhao X. On leadership and self-awareness . Wharton Magazine .

Lilienfeld SO, Basterfield C. Reflective practice in clinical psychology: Reflections from basic psychological science . Clin Psychol Sci Pract . 2020;27(4):e12352. doi:10.1111/cpsp.12352

Kaiser RH, Kang MS, Lew Y, et al. Abnormal frontinsular-default network dynamics in adolescent depression and rumination: a preliminary resting-state co-activation pattern analysis . Neuropsychopharmacol . 2019;44:1604-1612. doi:10.1038/s41386-019-0399-3

Eurich T. What self-awareness really is (and how to cultivate it) . Harvard Business Review .

Litman JA, Robinson OC, Demetre JD. Intrapersonal curiosity: Inquisitiveness about the inner self . Self Ident . 2017;16(2):231-250. doi:10.1080/15298868.2016.1255250

Brock, AC. The history of introspection revisited . In JW Clegg (Ed.), Self-Observation in the Social Sciences .

Pronin, E & Kugler, MB. Valuing thoughts, ignoring behavior: The introspection illusion as a source of the bias blind spot. J Exper Soc Psychol . 2007; 43(4): 565-578. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2006.05.011.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Introspection as the Basic Method in Psychological Science

- First Online: 19 July 2017

Cite this chapter

- Jaan Valsiner 2

Part of the book series: SpringerBriefs in Psychology ((BRIEFSTHEORET))

1418 Accesses

The primary method of psychology needs to be introspection. Yet any introspective evidence, to be of value to science, needs to be explicated into the public domain—“shared” between people and generalized from scientific knowledge creation. In this chapter I outline the original Wurzburg method of Karl Buhler and its transformation by Brady Wagoner. Analysis of the rating scales is included.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Compare two rating tasks: (1) Object = MOTHER , end points in scale “ GOOD ”___“ BAD ”, and (2) Object = MOTHER , end points in scale “ POTATO ”_____.“ CELLPHONE ” No. (1) is usual in psychology, and no. (2) is blatantly weird. Yet even the weird version is—at the level of a person’s affective abstraction—answerable (see processes of symbol formation in Werner and Kaplan 1963 ).

Abbey, E., & Diriwächter, R. (Eds.). (2008). Innovating genesis: Microgenesis and the constructive mind in action . Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishers.

Google Scholar

Brentano, F. (1874). Psychologie vom empirischen Standpunkte . Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot.

Brock, A. (1991). Imageless thought or stimulus error? The social construction of private experiences. In W. R. Woodward & R. S. Cohen (Eds.), World views and scientific discipline formation (pp. 97–106). Dordrecht: Kluwerr.

Chapter Google Scholar

Bühler, K. (1951). On thought connections. In D. Rapaport (Ed.), Organization and pathology of thought (pp. 39–57). New York: Columbia University Press [partial translation of Bühler’s original published in 1908].

Burkart, T. (2010). Qualitatives Experiment. In G. Mey & K. Mruck (Eds.), Handbuch qualitative Forschung in der Psychologie (pp. 254–262). VS Verlag: Wiesbaden.

Burkart, T., & Weggen, J. (2015). Dialogic introspection: A method for exploring emotions in everyday life and experimental contexts. In H. Flam & J. Kleres (Eds.), Methods of exploring emotions (pp. 101–111). London: Routledge.

Burkart, T., Kleining, G., & Witt, H. (2010). Dialogische Introspektion . Wiesbaden: VS Verlag.

Book Google Scholar

Diriwächter, R. (2009). Idiographic microgenesis: Re-visiting the experimental tradition of Aktualgenese. In J. Valsiner, P. Molenaar, M. Lyra, & N. Chaudhary (Eds.), Dynamic process methodology in the social and developmental sciences (pp. 319–352). New York: Springer.

Ericsson, K. A., & Simon, H. (1993). Protocol analysis: Verbal reports as data (2nd ed.). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Humphrey, G. (1951). Thinking . London: Methuen.

Kleining, G. (2010). Erleben eines Bahnhofs. In T. Burkart, G. Kleining, & H. Witt (Eds.), Dialogische Introspektion (pp. 64–75). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag.

Sander, F. (1928). Experimentelle Ergebnisse der Gestaltpsychologie. In E. Becher (Ed.), Bericht über den X. Kongress für experimentelle Psychologie in Bonn (pp. 23–88). Jena: Gustav Fischer.

Simon, H. (2007). Karl Duncker and cognitive science. In J. Valsiner (Ed.), Thinking in psychological science (pp. 3–16). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Toomela, A., & Valsiner, J. (Eds.). (2010). Methodological thinking in psychology: 60 years gone astray? Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishers.

Valsiner, J. (2012). A guided science . New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

Wagoner, B. (2007). Overcoming psychology’s methodology: Finding synthesis beyond the American and German-Austrian division. IPBS: Integrative Psychological & Behavioral Science, 41 (1), 66–74.

Wagoner, B. (2009). The experimental methodology of constructive microgenesis. In J. Valsiner, P. Molenaar, M. Lyra, & N. Chaudhary (Eds.), Dynamic process methodology in the social and developmental sciences (pp. 99–121). New York: Springer.

Wagoner, B. (2012). Culture in constructive remembering. In J. Valsiner (Ed.), Oxford handbook of culture and psychology (pp. 1034–1054). New York: Oxford University Press.

Wagoner, B. (2017). The constructive mind . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wagoner, B., & Valsiner, J. (2005). Rating tasks in psychology: From static ontology to dialogical synthesis of meaning. In A. Gülerce, A. Hofmeister, I. Staeuble, G. Saunders, & J. Kaye (Eds.), Contemporary theorizing in psychology: Global perspectives (pp. 197–213). Toronto: Captus Press.

Werner, H. (1956). Microgenesis and aphasia. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 52 , 347–353.

Article Google Scholar

Werner, H., & Kaplan, B. (1963). Symbol formation . New York: Wiley.

Witt, H. (2010). Introspektion. In G. Mey & K. Mruck (Eds.), Handbuch Qualitative Forschung in der Psychologie (pp. 491–505). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Communication and Psychology, Aalborg University, Aalborg, Denmark

Jaan Valsiner

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Valsiner, J. (2017). Introspection as the Basic Method in Psychological Science. In: From Methodology to Methods in Human Psychology . SpringerBriefs in Psychology(). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-61064-1_6

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-61064-1_6

Published : 19 July 2017

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-61063-4

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-61064-1

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Psychological Foundations

Early psychology—structuralism and functionalism, learning objectives.

- Define structuralism and functionalism and the contributions of Wundt and James to the development of psychology

Psychology is a relatively young science with its experimental roots in the 19th century, compared, for example, to human physiology, which dates much earlier. As mentioned, anyone interested in exploring issues related to the mind generally did so in a philosophical context prior to the 19th century. Two men, working in the 19th century, are generally credited as being the founders of psychology as a science and academic discipline that was distinct from philosophy. Their names were Wilhelm Wundt and William James.

Wundt and Structuralism

Structuralism is one of the earliest schools of psychology, focused on understanding the conscious experience through introspection. It was introduced by Wilhelm Wundt and built upon by his student, Edward Titchener. Let’s review a brief history of how structuralism was developed by these two scholars.

Wilhelm Wundt (1832–1920) was a German scientist who was the first person to be referred to as a psychologist. His famous book entitled Principles of Physiological Psychology was published in 1873. Wundt viewed psychology as a scientific study of conscious experience, and he believed that the goal of psychology was to identify components of consciousness and how those components combined to result in our conscious experience. Wundt used introspection (he called it “internal perception”), a process by which someone examines their own conscious experience as objectively as possible, making the human mind like any other aspect of nature that a scientist observed. He believed in the notion of voluntarism—that people have free will and should know the intentions of a psychological experiment if they were participating (Danziger, 1980). Wundt considered his version experimental introspection; he used instruments such as those that measured reaction time. He also wrote Volkerpsychologie in 1904 in which he suggested that psychology should include the study of culture, as it involves the study of people.

Wundt’s version of introspection used only very specific experimental conditions in which an external stimulus was designed to produce a scientifically observable (repeatable) experience of the mind (Danziger, 1980). The first stringent requirement was the use of “trained” or practiced observers, who could immediately observe and report a reaction. The second requirement was the use of repeatable stimuli that always produced the same experience in the subject and allowed the subject to expect and thus be fully attentive to the inner reaction. These experimental requirements were put in place to eliminate “interpretation” in the reporting of internal experiences and to counter the argument that there is no way to know that an individual is observing their mind or consciousness accurately, since it cannot be seen by any other person.

Edward Titchener, one of his students, built upon Wundt’s ideas to develop the idea concept of structuralism . Its focus was on the contents of mental processes rather than their function (Pickren & Rutherford, 2010). Wundt established his psychology laboratory at the University at Leipzig in 1879. In this laboratory, Wundt and his students conducted experiments on, for example, reaction times. A subject, sometimes in a room isolated from the scientist, would receive a stimulus such as a light, image, or sound. The subject’s reaction to the stimulus would be to push a button, and an apparatus would record the time to reaction. Wundt could measure reaction time to one-thousandth of a second (Nicolas & Ferrand, 1999). Experimental requirements of using trained observers and repeatable stimuli were put in place to eliminate “interpretation” of the reporting of internal experiences. However, despite the efforts to train individuals in the process of introspection, this process remained highly subjective, and there was very little agreement between individuals.

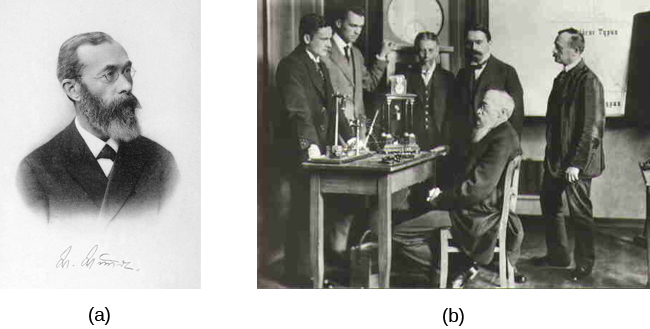

Figure 1 . (a) Wilhelm Wundt is credited as one of the founders of psychology. He created the first laboratory for psychological research. (b) This photo shows him seated and surrounded by fellow researchers and equipment in his laboratory in Germany.

Watch this video to learn more about the early history of psychology.

Figure 2 . William James, shown here in a self-portrait, was the first American psychologist.

James and Functionalism

William James (1842–1910) was the first American psychologist who espoused a different perspective on how psychology should operate. James was introduced to Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection and accepted it as an explanation of an organism’s characteristics. Key to that theory is the idea that natural selection leads to organisms that are adapted to their environment, including their behavior. Adaptation means that a trait of an organism has a function for the survival and reproduction of the individual, because it has been naturally selected. As James saw it, psychology’s purpose was to study the function of behavior in the world, and as such, his perspective was known as functionalism , which is regarded as another early school of psychology.

Functionalism focused on how mental activities helped an organism fit into its environment. Functionalism has a second, more subtle meaning in that functionalists were more interested in the operation of the whole mind rather than of its individual parts, which were the focus of structuralism. Like Wundt, James believed that introspection could serve as one means by which someone might study mental activities, but James also relied on more objective measures, including the use of various recording devices, and examinations of concrete products of mental activities and of anatomy and physiology (Gordon, 1995).

- Modification, adaptation, and original content. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- The History of Psychology. Authored by : OpenStax College. Located at : https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-2-history-of-psychology . License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Download for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Wundt and Structuralism. Provided by : OpenStax. Located at : https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-2-history-of-psychology . License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Psychology 101 - Wundt & James: Structuralism & Functionalism - Vook. Provided by : VookInc's channel. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SW6nm69Z_IE . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

Search form

You are here.

- Structuralism: Introspection and the Awareness of Subjective Experience

Wundt’s research in his laboratory in Liepzig focused on the nature of consciousness itself. Wundt and his students believed that it was possible to analyze the basic elements of the mind and to classify our conscious experiences scientifically. Wundt began the field known as structuralism, a school of psychology whose goal was to identify the basic elements or “structures” of psychological experience . Its goal was to create a “periodic table” of the “elements of sensations,” similar to the periodic table of elements that had recently been created in chemistry.

Structuralists used the method of introspection to attempt to create a map of the elements of consciousness. Introspection involves asking research participants to describe exactly what they experience as they work on mental tasks , such as viewing colors, reading a page in a book, or performing a math problem. A participant who is reading a book might report, for instance, that he saw some black and colored straight and curved marks on a white background. In other studies the structuralists used newly invented reaction time instruments to systematically assess not only what the participants were thinking but how long it took them to do so. Wundt discovered that it took people longer to report what sound they had just heard than to simply respond that they had heard the sound. These studies marked the first time researchers realized that there is a difference between the sensation of a stimulus and theperception of that stimulus, and the idea of using reaction times to study mental events has now become a mainstay of cognitive psychology.

Perhaps the best known of the structuralists was Edward Bradford Titchener (1867–1927). Titchener was a student of Wundt who came to the United States in the late 1800s and founded a laboratory at Cornell University. In his research using introspection, Titchener and his students claimed to have identified more than 40,000 sensations, including those relating to vision, hearing, and taste.

An important aspect of the structuralist approach was that it was rigorous and scientific. The research marked the beginning of psychology as a science, because it demonstrated that mental events could be quantified. But the structuralists also discovered the limitations of introspection. Even highly trained research participants were often unable to report on their subjective experiences. When the participants were asked to do simple math problems, they could easily do them, but they could not easily answer how they did them. Thus the structuralists were the first to realize the importance of unconscious processes—that many important aspects of human psychology occur outside our conscious awareness, and that psychologists cannot expect research participants to be able to accurately report on all of their experiences.

- 22184 reads

- Approach and Pedagogy

- The Problem of Intuition Research Focus: Unconscious Preferences for the Letters of Our Own Name

- Why Psychologists Rely on Empirical Methods

- Levels of Explanation in Psychology

- The Challenges of Studying Psychology KET TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Early Psychologists

- Functionalism and Evolutionary Psychology

- Psychodynamic Psychology

- Behaviorism and the Question of Free Will Research Focus: Do We Have Free Will?

- The Cognitive Approach and Cognitive Neuroscience The War of the Ghosts

- Social-Cultural Psychology

- The Many Disciplines of Psychology Psychology in Everyday Life: How to Effectively Learn and Remember KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Chapter Summary

- The Scientific Method

- Laws and Theories as Organizing Principles

- The Research Hypothesis

- Conducting Ethical Research Characteristics of an Ethical Research Project Using Human Participants

- Ensuring That Research Is Ethical

- Research With Animals APA Guidelines on Humane Care and Use of Animals in Research KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Descriptive Research: Assessing the Current State of Affairs

- Correlational Research: Seeking Relationships Among Variables

- Experimental Research: Understanding the Causes of Behavior Research Focus: Video Games and Aggression KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- You Can Be an Informed Consumer of Psychological Research Learning Objectives Threats to the Validity of Research Psychology in Everyday Life: Critically Evaluating the Validity of Websites KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Neurons Communicate Using Electricity and Chemicals Video Clip: The Electrochemical Action of the Neuron

- Neurotransmitters: The Body’s Chemical Messengers KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- The Old Brain: Wired for Survival

- The Cerebral Cortex Creates Consciousness and Thinking

- Functions of the Cortex

- The Brain Is Flexible: Neuroplasticity Research Focus: Identifying the Unique Functions of the Left and Right Hemispheres Using Split-Brain Patients Psychology in Everyday Life: Why Are Some People Left-Handed? KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Lesions Provide a Picture of What Is Missing

- Recording Electrical Activity in the Brain

- Peeking Inside the Brain: Neuroimaging Research Focus: Cyberostracism KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Electrical Control of Behavior: The Nervous System

- The Body’s Chemicals Help Control Behavior: The Endocrine System KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Sensory Thresholds: What Can We Experience? Link

- Measuring Sensation Research Focus: Influence without Awareness KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- The Sensing Eye and the Perceiving Visual Cortex

- Perceiving Color

- Perceiving Form

- Perceiving Depth

- Perceiving Motion Beta Effect and Phi Phenomenon KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Hearing Loss KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Experiencing Pain KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- How the Perceptual System Interprets the Environment Video Clip: The McGurk Effect Video Clip: Selective Attention

- The Important Role of Expectations in Perception Psychology in Everyday Life: How Understanding Sensation and Perception Can Save Lives KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Sleep Stages: Moving Through the Night

- Sleep Disorders: Problems in Sleeping

- The Heavy Costs of Not Sleeping

- Dreams and Dreaming KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Speeding Up the Brain With Stimulants: Caffeine, Nicotine, Cocaine, and Amphetamines

- Slowing Down the Brain With Depressants: Alcohol, Barbiturates and Benzodiazepines, and Toxic Inhalants

- Opioids: Opium, Morphine, Heroin, and Codeine

- Hallucinogens: Cannabis, Mescaline, and LSD

- Why We Use Psychoactive Drugs Research Focus: Risk Tolerance Predicts Cigarette Use KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Changing Behavior Through Suggestion: The Power of Hypnosis

- Reducing Sensation to Alter Consciousness: Sensory Deprivation

- Meditation Video Clip: Try Meditation Psychology in Everyday Life: The Need to Escape Everyday Consciousness KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- How the Environment Can Affect the Vulnerable Fetus KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- The Newborn Arrives With Many Behaviors Intact Research Focus: Using the Habituation Technique to Study What Infants Know

- Cognitive Development During Childhood

- Video Clip: Object Permanence

- Social Development During Childhood

- Knowing the Self: The Development of the Self-Concept

- Video Clip: The Harlows’ Monkeys

- Video Clip: The Strange Situation Research Focus: Using a Longitudinal Research Design to Assess the Stability of Attachment KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Physical Changes in Adolescence

- Cognitive Development in Adolescence

- Social Development in Adolescence

- Developing Moral Reasoning: Kohlberg’s Theory

- Video Clip: People Being Interviewed About Kohlberg’s Stages KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Physical and Cognitive Changes in Early and Middle Adulthood

- Social Changes in Early and Middle Adulthood KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Cognitive Changes During Aging

- Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease

- Social Changes During Aging: Retiring Effectively

- Death, Dying, and Bereavement KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Pavlov Demonstrates Conditioning in Dogs

- The Persistence and Extinction of Conditioning

- The Role of Nature in Classical Conditioning KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- How Reinforcement and Punishment Influence Behavior: The Research of Thorndike and Skinner

- Video Clip: Thorndike’s Puzzle Box

- Creating Complex Behaviors Through Operant Conditioning KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Observational Learning: Learning by Watching

- Video Clip: Bandura Discussing Clips From His Modeling Studies Research Focus: The Effects of Violent Video Games on Aggression KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Using Classical Conditioning in Advertising

- Video Clip: Television Ads Psychology in Everyday Life: Operant Conditioning in the Classroom

- Reinforcement in Social Dilemmas KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Video Clip: Kim Peek

- Explicit Memory

- Implicit Memory Research Focus: Priming Outside Awareness Influences Behavior

- Stages of Memory: Sensory, Short-Term, and Long-Term Memory

- Sensory Memory

- Short-Term Memory KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Encoding and Storage: How Our Perceptions Become Memories Research Focus: Elaboration and Memory

- Using the Contributions of Hermann Ebbinghaus to Improve Your Memory

- The Structure of LTM: Categories, Prototypes, and Schemas

- The Biology of Memory KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Source Monitoring: Did It Really Happen?

- Schematic Processing: Distortions Based on Expectations

- Misinformation Effects: How Information That Comes Later Can Distort Memory

- Overconfidence

- Heuristic Processing: Availability and Representativeness

- Salience and Cognitive Accessibility

- Counterfactual Thinking Psychology in Everyday Life: Cognitive Biases in the Real World KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- How We Talk (or Do Not Talk) about Intelligence How We Talk (or Do Not Talk) about Intelligence

- General (g) Versus Specific (s) Intelligences

- Measuring Intelligence: Standardization and the Intelligence Quotient

- The Biology of Intelligence

- Is Intelligence Nature or Nurture? Psychology in Everyday Life: Emotional Intelligence KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Extremes of Intelligence: Retardation and Giftedness

- Extremely Low Intelligence

- Extremely High Intelligence

- Sex Differences in Intelligence

- Racial Differences in Intelligence Research Focus: Stereotype Threat KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- The Components of Language Examples in Which Syntax Is Correct but the Interpretation Can Be Ambiguous

- The Biology and Development of Language Research Focus: When Can We Best Learn Language? Testing the Critical Period Hypothesis

- Learning Language

- How Children Learn Language: Theories of Language Acquisition

- Bilingualism and Cognitive Development

- Can Animals Learn Language?

- Video Clip: Language Recognition in Bonobos

- Languageand Perception KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Captain Sullenberger Conquers His Emotions Captain Sullenberger Conquers His Emotions

- Video Clip: The Basic Emotions

- The Cannon-Bard and James-Lange Theories of Emotion Research Focus: Misattributing Arousal

- Communicating Emotion KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- The Negative Effects of Stress

- Stressors in Our Everyday Lives

- Responses to Stress

- Managing Stress

- Emotion Regulation Research Focus: Emotion Regulation Takes Effort KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Finding Happiness Through Our Connections With Others

- What Makes Us Happy? KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Eating: Healthy Choices Make Healthy Lives

- Sex: The Most Important Human Behavior

- The Experience of Sex

- The Many Varieties of Sexual Behavior Psychology in Everyday Life: Regulating Emotions to Improve Our Health KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISE AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Identical Twins Reunited after 35 Years Identical Twins Reunited after 35 Years

- Personality as Traits Example of a Trait Measure

- Situational Influences on Personality

- The MMPI and Projective Tests Psychology in Everyday Life: Leaders and Leadership KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Psychodynamic Theories of Personality: The Role of the Unconscious

- Id, Ego, and Superego Research Focus: How the Fear of Death Causes Aggressive Behavior

- Strengths and Limitations of Freudian and Neo-Freudian Approaches

- Focusing on the Self: Humanism and Self-Actualization Research Focus: Self-Discrepancies, Anxiety, and Depression KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Studying Personality Using Behavioral Genetics

- Studying Personality Using Molecular Genetics

- Reviewing the Literature: Is Our Genetics Our Destiny? KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- When Minor Body Imperfections Lead to Suicide When Minor Body Imperfections Lead to Suicide

- Defining Disorder Psychology in Everyday Life: Combating the Stigma of Abnormal Behavior

- Diagnosing Disorder: The DSM

- Diagnosis or Overdiagnosis? ADHD, Autistic Disorder, and Asperger’s Disorder

- Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

- Autistic Disorder and Asperger’s Disorder KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Generalized Anxiety Disorder

- Panic Disorder

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders

- Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

- Dissociative Disorders: Losing the Self to Avoid Anxiety

- Dissociative Amnesia and Fugue

- Dissociative Identity Disorder

- Explaining Anxiety and Dissociation Disorders KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Dysthymia and Major Depressive Disorder

- Bipolar Disorder

- Explaining Mood Disorders Research Focus: Using Molecular Genetics to Unravel the Causes of Depression KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Symptoms of Schizophrenia

- Explaining Schizophrenia KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISE AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Borderline Personality Disorder Research Focus: Affective and Cognitive Deficits in BPD

- Antisocial Personality Disorder (APD) KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Somatoform and Factitious Disorders

- Sexual Disorders

- Disorders of Sexual Function

- Gender Identity Disorder

- Paraphilias KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Therapy on Four Legs Therapy on Four Legs

- Psychodynamic Therapy Important Characteristics and Experiences in Psychoanalysis

- Humanistic Therapies

- Behavioral Aspects of CBT

- Cognitive Aspects of CBT

- Combination (Eclectic) Approaches to Therapy KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Drug Therapies

- Using Stimulants to Treat ADHD

- Antidepressant Medications

- Antianxiety Medications

- Antipsychotic Medications

- Direct Brain Intervention Therapies KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Group, Couples, and Family Therapy

- Self-Help Groups

- Community Mental Health: Service and Prevention Some Risk Factors for Psychological Disorders Research Focus: The Implicit Association Test as a Behavioral Marker for Suicide KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISE AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Effectiveness of Psychological Therapy ResearchFocus:Meta-AnalyzingClinicalOutcomes

- Effectiveness of Biomedical Therapies

- Effectiveness of Social-CommunityApproaches KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Binge Drinking and the Death of a Homecoming Queen Binge Drinking and the Death of a Homecoming Queen

- Perceiving Others

- Forming Judgments on the Basis of Appearance: Stereotyping, Prejudice, and Discrimination Implicit Association Test Research Focus: Forming Judgments of People in Seconds

- Close Relationships

- Causal Attribution: Forming Judgments by Observing Behavior

- Attitudes and Behavior KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Helping Others: Altruism Helps Create Harmonious Relationships

- Why Are We Altruistic?

- How the Presence of Others Can Reduce Helping

- Video Clip: The Case of Kitty Genovese

- Human Aggression: An Adaptive y et Potentially Damaging Behavior

- The Ability to Aggress Is Part of Human Nature

- Negative Experiences Increase Aggression

- Viewing Violent Media Increases Aggression

- Video Clip Research Focus: The Culture of Honor

- Conformity and Obedience: How Social Influence Creates Social Norms

- Do We Always Conform? KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISES AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Working in Front of Others: Social Facilitation and Social Inhibition

- Working Together in Groups Psychology in Everyday Life: Do Juries Make Good Decisions?

- Using Groups Effectively KEY TAKEAWAYS EXERCISE AND CRITICAL THINKING

- Back Matter

This action cannot be undo.

Choose a delete action Empty this page Remove this page and its subpages

Content is out of sync. You must reload the page to continue.

New page type Book Topic Interactive Learning Content

- Config Page

- Add Page Before

- Add Page After

- Delete Page

Psychologily

Unlocking the Power of Introspection and How It Is Used In Psychology Research

Have you ever wondered what is introspection and how it is used in psychology research? If you’re interested in psychology research, you may have encountered the term “introspection.” Introspection is examining your thoughts, emotions, judgments, and perceptions inwardly. It’s a valuable tool in psychology research, as it allows researchers to gain insight into the mind’s inner workings.

Introspection has a long history in psychology, dating back to the early days of the field. While it’s not always considered a scientific method, it can be valuable for generating hypotheses and exploring new ideas. In recent years, there has been renewed interest in introspection as a research method, and many psychologists are now exploring its potential benefits and drawbacks.

In this article, we’ll examine introspection and how it is used in psychology research. We’ll explore its history, benefits, weaknesses, and some examples of how it has been used in study.

Historical Overview of Introspection

Introspection is a psychological process involving looking inward to examine one’s thoughts, emotions, judgments, and perceptions. The concept of introspection has a long history, dating back to ancient Greek philosophers such as Socrates and Plato. However, introspection as a scientific method of studying the mind emerged in the late 19th century.

A German psychologist, Wilhelm Wundt , is often credited with foundering modern psychology and inventing introspection as a research method. Wundt believed that psychology should be a science that studies the conscious experience of individuals. He used introspection to study the structure of the mind and the elements of consciousness.

Wundt’s approach to introspection involved careful observation and analysis of one’s own experiences. Participants in his experiments were asked to describe their own conscious experiences in detail, such as the sensations they felt when looking at a particular color or listening to a sound. Wundt believed that by studying the structure of consciousness, psychologists could better understand the workings of the mind.

Wundt’s approach to introspection was later criticized for its subjectivity and lack of reliability. However, his work paved the way for developing other methods of studying the mind, such as behaviorism and cognitive psychology. Today, introspection is still used as a research method in psychology. Still, it is usually combined with other ways, such as neuroimaging and behavioral observation, to understand the mind better.

Introspection in Modern Psychology

Introspection is a fundamental process in modern psychology that involves examining one’s own thoughts, emotions, judgments, and perceptions. The method of introspection is used in various areas of psychology, including cognitive and behavioral psychology. Here are some of the ways introspection is used in modern psychology.

Role in Cognitive Psychology

Cognitive psychology is a branch of psychology that focuses on the study of mental processes, including perception, attention, memory, and problem-solving. Introspection plays a crucial role in cognitive psychology, as it allows researchers to gain insight into the subjective experiences of individuals.

For example, in a study on attention, researchers may use introspection to ask participants to describe their experience of focusing on a particular task. This information can then be used to develop theories about how attention works and can be improved.

Influence on Behavioral Psychology

Behavioral psychology is a branch of psychology that focuses on studying behavior, including observable actions and responses to stimuli. While introspection is not as central to behavioral psychology as cognitive psychology, it still plays a role in understanding behavior.

For example, in a study on addiction, researchers may use introspection to ask participants to describe their experience of craving a particular substance. This information can then be used to develop interventions targeting the underlying psychological processes contributing to addiction.

Methods of Introspection

If you want to learn more about your internal psychological processes, introspection can be helpful. Here are some methods of introspection that you can use to gain more insight into your thoughts, emotions, and memories.

Self-Report

Self-report is a standard method of introspection that involves asking yourself questions about your thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. You can use self-reporting to gain more insight into your personality traits, values, and beliefs. For example, you might ask yourself questions like:

- What are my biggest strengths and weaknesses?

- What are my core values and beliefs?

- What motivates me to do the things I do?

By answering these questions honestly, you can better understand your own psychology.

Diaries and Journals

Keeping a diary or journal is another effective method of introspection. By writing down your thoughts and feelings on a regular basis, you can gain more insight into your own psychology. You can use your diary or journal to reflect on your day-to-day experiences, explore your emotions, and identify patterns in your behavior. For example, you might write about:

- What happened today that made me feel happy or sad?

- What are some of the challenges I’m facing right now?

- What are some of the things I’m grateful for in my life?

By regularly reflecting on your experiences in this way, you can gain a deeper understanding of your psychology.

Think-Aloud Protocols

Think-aloud protocols are a method of introspection that involves verbalizing your thoughts as you complete a task. This can be a helpful way to gain insight into your own cognitive processes. For example, use a think-aloud protocol to explore how you approach a problem-solving task. As you work through the study, you verbalize your thoughts, explaining why you’re making certain decisions and how you’re solving the problem.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Introspection

Introspection is a useful tool in psychology research for gaining insight into one’s mental processes. However, like any method, it has both strengths and limitations.

Strengths of Introspection

One of the primary strengths of introspection is that it allows researchers to access private mental experiences that cannot be directly observed through other scientific methods. By examining their own thoughts, emotions, and perceptions, individuals can provide valuable data that can be used to develop theories and hypotheses about mental processes.

Additionally, introspection is a relatively easy and straightforward method that does not require extensive training or specialized equipment. This makes it accessible to a wide range of individuals, including those without a background in psychology.

Limitations of Introspection

Despite its strengths, introspection also has several limitations that must be considered. One primary end is that introspective reports may be biased or inaccurate due to various factors, including social desirability bias and difficulty accurately recalling past experiences.

Another limitation is that introspection is a subjective process influenced by various factors, including mood, motivation, and cognitive biases. Different individuals may provide additional reports of the same mental experience, making it difficult to draw definitive conclusions.

Introspection in Clinical Practice

Introspection is a valuable tool in clinical practice as it allows individuals to explore their thoughts, emotions, and behaviors in a safe and controlled environment. This process can help individuals gain insight into their mental health and make positive life changes. In this section, we will explore the therapeutic applications of introspection and provide case studies to illustrate its effectiveness.

Therapeutic Applications

Introspection is often used in psychotherapy to help individuals gain insight into their mental health. By exploring their thoughts, emotions, and behaviors, individuals can identify patterns contributing to their mental health issues. This process can help individuals develop coping strategies and make positive life changes.

One therapeutic application of introspection is cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). CBT is a type of therapy that focuses on changing negative thought patterns and behaviors. Introspection can be used in CBT to help individuals identify their negative thought patterns and replace them with more positive ones.

Another therapeutic application of introspection is psychodynamic therapy. Psychodynamic therapy is a type of therapy that focuses on exploring the unconscious mind and how it influences behavior. Introspection can be used in psychodynamic therapy to help individuals gain insight into their unconscious thoughts and behaviors.

Case Studies

Case studies can provide valuable insight into the effectiveness of introspection in clinical practice. Here are two examples:

- Case Study 1: Jane has been struggling with depression for several years. She has tried various treatments, but nothing seems to be working. Her therapist suggests that she try introspection to gain insight into her depression. Through introspection, Jane realizes that her depression is linked to negative self-talk. She works with her therapist to develop strategies to replace her negative self-talk with more positive self-talk. Over time, Jane’s depression improves.

- Case Study 2: John has been struggling with anxiety for several years. He has tried various treatments, but nothing seems to be working. His therapist suggests that he try introspection to gain insight into his anxiety. Through introspection, John realizes that his concern is linked to his fear of failure. He works with his therapist to develop strategies to overcome his fear of failure. Over time, John’s anxiety improves.

In both case studies, introspection was valuable in helping individuals gain insight into their mental health issues and make positive changes in their lives.

Introspection in Social and Cultural Context

Cultural considerations.

Regarding introspection, cultural differences can play a significant role in shaping how individuals perceive and reflect on their mental states. For instance, some cultures may emphasize group harmony and social conformity, which can make it more challenging for individuals to engage in introspection without feeling self-conscious or uncomfortable. In contrast, cultures prioritizing individualism may encourage individuals to explore their inner selves more freely.

Additionally, cultural differences can influence which aspects of the self an individual focuses on during introspection. For example, in some cultures, individuals may be more likely to reflect on their relationships with others or their roles within their communities, while in others, individuals may be more inclined to focus on their achievements or goals.

Social Implications

Introspection can also have important social implications, particularly in social psychology. For example, research has shown that social factors, such as the presence of others or the perceived expectations of others, can influence individuals’ introspective processes. Additionally, introspection can influence social behavior by shaping how individuals respond to social feedback or make decisions in social contexts.

One classic example of the social implications of introspection is the phenomenon of “self-serving bias,” where individuals are more likely to attribute their successes to internal factors (such as their abilities) and their failures to external factors (such as bad luck). This bias can have important implications for how individuals perceive themselves and their place within social groups.

Future of Introspection in Psychology Research

As the field of psychology continues to evolve, the role of introspection in research is likely to change as well. While introspection has been a valuable tool for exploring one’s mental and emotional states, it has limitations that may make it less useful in certain contexts.

One potential future use of introspection in psychology research is as a complement to other methods, such as physiological measures or behavioral observations. By combining multiple data sources, researchers can better understand the complex processes underlying psychological phenomena.

Another potential future direction for introspection in psychology research is the development of more structured and standardized methods for collecting and analyzing introspective data. This could involve using specific prompts or questions to guide participants’ introspection or the development of standardized rating scales to quantify the results.

It is also possible that advances in technology will allow for new ways of collecting and analyzing introspective data. For example, wearable devices that can track physiological responses may provide a more objective measure of participants’ internal experiences. Similarly, machine learning algorithms can identify patterns in introspective data that are not immediately apparent to human observers.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the definition of introspection in psychology research.

Introspection is a psychological process involving looking inward to examine one’s thoughts, emotions, judgments, and perceptions. In psychology, introspection refers to the informal process of exploring one’s own mental and emotional states. It is a method of self-observation and self-reflection that can provide insights into one’s own experiences and mental processes.

How is introspection used in real-life examples?

Introspection is used in real-life examples, including therapy sessions, meditation practices, and self-help techniques. In therapy, clients may be asked to reflect on their thoughts and emotions to gain insight into their behavior and feelings. In meditation, practitioners may use introspection to observe their thoughts and emotions without judgment. Self-help techniques like journaling or self-reflection exercises can also involve introspection.

Who is the founder of introspection in psychology?

Wilhelm Wundt is often credited as the founder of introspection in psychology. He is known for his work in establishing psychology as a scientific discipline and for his use of introspection as a research method in his laboratory experiments.

What is the difference between introspection and self-reflection?

Introspection and self-reflection are often used interchangeably, but there is a subtle difference between the two. Introspection refers to the process of looking inward to examine one’s own thoughts and emotions. Self-reflection, however, involves thinking about one’s own experiences and behavior more generally, without necessarily looking at specific thoughts or feelings.

What is the role of introspection in psychological research?

Introspection can play a valuable role in psychological research by providing insights into subjective experiences and mental processes. It can be used to explore topics such as emotion, perception, and memory, and can provide a rich source of data for researchers. However, introspection has limitations, as it is subjective and can be influenced by factors such as bias and memory.

Can you provide an example of how introspection is used in psychological research?

One example of how introspection is used in psychological research is in emotion studies. Participants may be asked to reflect on their emotional experiences and report their thoughts and feelings during specific situations. This data can then be used to gain insights into the nature of emotions and how individuals experience them.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Table of Contents

- New in this Archive

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Introspection

Introspection, as the term is used in contemporary philosophy of mind, is a means of learning about one's own currently ongoing, or perhaps very recently past, mental states or processes. You can, of course, learn about your own mind in the same way you learn about others' minds—by reading psychology texts, by observing facial expressions (in a mirror), by examining readouts of brain activity, by noting patterns of past behavior—but it's generally thought that you can also learn about your mind introspectively , in a way that no one else can. But what exactly is introspection? No simple characterization is widely accepted.

Introspection is a key concept in epistemology, since introspective knowledge is often thought to be particularly secure, maybe even immune to skeptical doubt. Introspective knowledge is also often held to be more immediate or direct than sensory knowledge. Both of these putative features of introspection have been cited in support of the idea that introspective knowledge can serve as a ground or foundation for other sorts of knowledge.

Introspection is also central to philosophy of mind, both as a process worth study in its own right and as a court of appeal for other claims about the mind. Philosophers of mind offer a variety of theories of the nature of introspection; and philosophical claims about consciousness, emotion, free will, personal identity, thought, belief, imagery, perception, and other mental phenomena are often thought to have introspective consequences or to be susceptible to introspective verification. For similar reasons, empirical psychologists too have discussed the accuracy of introspective judgments and the role of introspection in the science of the mind.

1.1 Necessary Features of an Introspective Process

1.2 the targets of introspection, 1.3 the products of introspection, 2.1.1 behavioral observation accounts, 2.1.2 theory theory accounts, 2.1.3 restrictions on parity, 2.2.1 simple monitoring accounts, 2.2.2 multi-process monitoring accounts, 2.3.1 self-fulfillment and containment, 2.3.2 self-shaping, 2.3.3 expressivism, 2.3.4 transparency, 2.4 introspective pluralism, 3.1 the rise of introspective psychology as a science, 3.2 early skepticism about introspective observation, 3.3 the decline of scientific introspection, 3.4 the re-emergence of scientific introspection, 4.1.1 varieties of perfection: infallibility, indubitability, incorrigibility, and self-intimation, 4.1.2 weaker guarantees, 4.1.3 privilege without guarantee, 4.2.1 of the causes of attitudes and behavior, 4.2.2 of attitudes, 4.2.3 of conscious experience, other internet resources, related entries, 1. general features of introspection.

Introspection is generally regarded as a process by means of which we learn about our own currently ongoing, or very recently past, mental states or processes. Not all such processes are introspective, however: Few would say that you have introspected if you learn that you're angry by seeing your facial expression in the mirror. However, it's unclear and contentious exactly what more is required for a process to qualify as introspective. A relatively restrictive account of introspection might require introspection to involve attention to and direct detection of one's ongoing mental states; but many philosophers think attention to or direct detection of mental states is impossible or at least not present in many paradigmatic instances of introspection.

For a process to qualify as “introspective” as the term is ordinarily used in contemporary philosophy of mind, it must minimally meet the following three conditions:

The mentality condition : Introspection is a process that generates, or is aimed at generating, knowledge, judgments, or beliefs about mental events, states, or processes, and not about affairs outside one's mind, at least not directly. In this respect, it is different from sensory processes that normally deliver information about outward events or about the non-mental aspects of the individual's body. The border between introspective and non-introspective knowledge can begin to seem blurry with respect to bodily self-knowledge such as proprioceptive knowledge about the position of one's limbs or nociceptive knowledge about one's pains. But it seems that in principle the introspective part of such processes, pertaining to judgments about one's mind—e.g., that one has the feeling as though one's arms were crossed or of toe-ishly located pain—can be distinguished from the non-introspective judgment that one's arms are in fact crossed or one's toe is being pinched.

The first-person condition : Introspection is a process that generates, or is aimed at generating, knowledge, judgments, or beliefs about one's own mind only and no one else's, at least not directly. Any process that in a similar manner generates knowledge of one's own and others' minds is by that token not an introspective process. (Some philosophers have contemplated peculiar or science fiction cases in which we might introspect the contents of others' minds directly—for example in telepathy or when two individuals' brains are directly wired together—but the proper interpretation of such cases is disputable see, e.g., Gertler 2000.)

The temporal proximity condition : Introspection is a process that generates knowledge, beliefs, or judgments about one's currently ongoing mental life only; or, alternatively (or perhaps in addition) immediately past (or even future) mental life, within a certain narrow temporal window (sometimes called the specious present; see the entry on the experience and perception of time ). You may know that you were thinking about Montaigne yesterday during your morning walk, but you cannot know that fact by current introspection alone—though perhaps you can know introspectively that you currently have a vivid memory of having thought about Montaigne. Likewise, you cannot know by introspection alone that you will feel depressed if your favored candidate loses the election in November—though perhaps you can know introspectively what your current attitude is toward the election or what emotion starts to rise in you when you consider the possible outcomes. Whether the target of introspection is best thought of as one's current mental life or one's immediately past mental life may depend on one's model of introspection: On self-detection models of introspection, according to which introspection is a causal process involving the detection of a mental state (see Section 2.2 below), it's natural to suppose that a brief lapse of time will transpire between the occurrence of the mental state that is the introspective target and the final introspective judgment about that state, which invites (but does not strictly imply) the idea that introspective judgments generally pertain to immediately past states. On self-shaping and self-fulfillment models of introspection, according to which introspective judgments create or embed the very state introspected (see Sections 2.3.1 and 2.3.2 below), it seems more natural to think that the target of introspection is one's current mental life or perhaps even the immediate future.

Few contemporary philosophers of mind would call a process “introspective” if it does not meet some version of the three conditions above, though in ordinary language the temporal proximity condition may sometimes be violated. (For example, in ordinary speech we might describe as “introspective” a process of thinking about why you abandoned a relationship last month or whether you're really as kind to your children as you think you are.) However, many philosophers of mind will resist calling a process that meets these three conditions “introspective” unless it also meets some or all of the following three conditions:

The directness condition : Introspection yields judgments or knowledge about one's own current mental processes relatively directly or immediately . It's difficult to articulate exactly what directness or immediacy involves in the present context, but some examples should make the import of this condition relatively clear. Gathering sensory information about the world and then drawing theoretical conclusions based on that information should not, according to this condition, count as introspective, even if the process meets the three conditions above. Seeing that a car is twenty feet in front of you and then inferring from that fact about the external world that you are having a visual experience of a certain sort does not, by this condition, count as introspective. However, as we will see in Section 2.3.4 below, those who embrace transparency theories of introspection may reject at least strong formulations of this condition.

The detection condition : Introspection involves some sort of attunement to or detection of a pre-existing mental state or event, where the introspective judgment or knowledge is (when all goes well) causally but not ontologically dependent on the target mental state. For example, a process that involved creating the state of mind that one attributes to oneself would not be introspective, according to this condition. Suppose I say to myself in silent inner speech, “I am saying to myself in silent inner speech, ‘haecceities of applesauce’”, without any idea ahead of time how I plan to complete the embedded quotation. Now, what I say may be true, and I may know it to be true, and I may know its truth (in some sense) directly, by a means by which I could not know the truth of anyone else's mind. That is, it may meet all the four conditions above and yet we may resist calling such a self-attribution introspective. Self-shaping (Section 2.3.2 below), expressivist (Section 2.3.3 below), and transparency (Section 2.3.4 below) accounts of self-knowledge emphasize the extent to which our self-knowledge often does not involve the detection of pre-existing mental states; and because something like the detection condition is implicitly or explicitly accepted by many philosophers, some philosophers (including some but not all of those who endorse self-shaping, expressivist, and/or transparency views) would regard it as inappropriate to regard such accounts of self-knowledge as accounts of introspection proper.

The effort condition : Introspection is not constant, effortless, and automatic . We are not every minute of the day introspecting. Introspection involves some sort of special reflection on one's own mental life that differs from the ordinary un-self-reflective flow of thought and action. The mind may monitor itself regularly and constantly without requiring any special act of reflection by the thinker—for example, at a non-conscious level certain parts of the brain or certain functional systems may monitor the goings-on of other parts of the brain and other functional systems, and this monitoring may meet all five conditions above—but this sort of thing is not what philosophers generally have in mind when they talk of introspection. However, this condition, like the directness and detection conditions, is not universally accepted. For example, philosophers who think that conscious experience requires some sort of introspective monitoring of the mind and who think of conscious experience as a more or less constant feature of our lives may reject the effort condition (Armstrong 1968, 1999; Lycan 1996).

Though not all philosophical accounts that are put forward by their authors as accounts of “introspection” meet all of conditions 4–6, most meet at least two of those. Because of differences in the importance accorded to conditions 4–6, it is not unusual for authors with otherwise similar accounts of self-knowledge to differ in their willingness to describe their accounts as accounts of “introspection”.

Accounts of introspection differ in what they treat as the proper targets of the introspective process. No major contemporary philosopher believes that all of mentality is available to be discovered by introspection. For example, the cognitive processes involved in early visual processing and in the detection of phonemes are generally held to be introspectively impenetrable and nonetheless (in some important sense) mental (Marr 1983; Fodor 1983). Many philosophers also accept the existence of unconscious beliefs or desires, in roughly the Freudian sense, that are not introspectively available (e.g., Gardner 1993; Velleman 2000; Moran 2001; Wollheim 2003; though see Lear 1998). Although in ordinary English usage we sometimes say we are “introspecting” when we reflect on our character traits, contemporary philosophers of mind generally do not believe that we can directly introspect character traits in the same sense in which we can introspect some of our other mental states (especially in light of research suggesting that we sometimes have poor knowledge of our traits, reviewed in Taylor and Brown 1988; Paulhus and John 1998; Vazire 2010).

The two most commonly cited classes of introspectible mental states are attitudes , such as beliefs, desires, evaluations, and intentions, and conscious experiences , such as emotions, images, and sensory experiences. (These two groups may not be wholly, or even partially, disjoint: Depending on other aspects of her view, a philosopher may regard some or all conscious experiences as involving attitudes, and/or she may regard attitudes as things that are or can be consciously experienced.) It of course does not follow from the fact (if it is a fact) that some attitudes are introspectible that all attitudes are, or from the fact that some conscious experiences are introspectible that all conscious experiences are. Some accounts of introspection focus on attitudes (e.g., Nichols and Stich 2003), while others focus on conscious experiences (e.g., Hill 1991; Goldman 2006; Schwitzgebel 2012); and it is sometimes unclear to what extent philosophers intend their remarks about the introspection of one type of target to apply to the other type. There is no guarantee that the same mechanism or process is involved in introspecting all the different potential targets.

Generically, this article will describe the targets of introspection as mental states , though in some cases it may be more apt to think of the targets as processes rather than states. Also, in speaking of the targets of introspection as targets , no presupposition is intended of a self-detection view of introspection as opposed to a self-shaping or containment or expressivist view (see Section 2 below). The targets are simply the states self-ascribed as a consequence of the introspective process if the process works correctly, or if the introspective process fails, the states that would have been self-ascribed.

Though philosophers have not explored the issue very thoroughly, accounts also differ regarding the products of introspection. Most philosophers hold that introspection yields something like beliefs or judgments about one's own mind, but others prefer to characterize the products of introspection as “thoughts”, “representations”, “awareness”, or the like. For ease of exposition, this article will describe the products of the introspective process as judgments, without meaning to beg the question against competing views.

2. Introspective Versus Non-Introspective Accounts of Self-Knowledge