Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write a rhetorical analysis | Key concepts & examples

How to Write a Rhetorical Analysis | Key Concepts & Examples

Published on August 28, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on July 23, 2023.

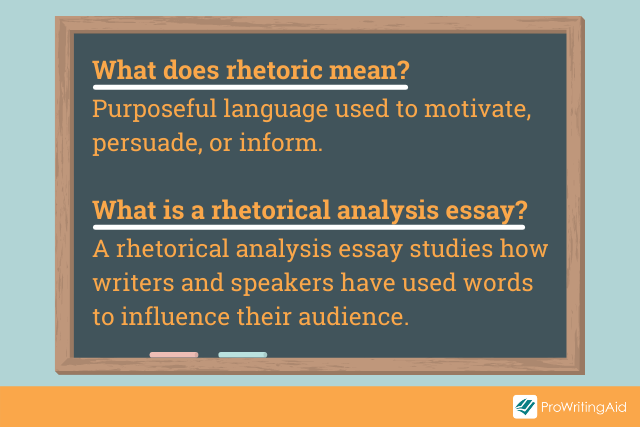

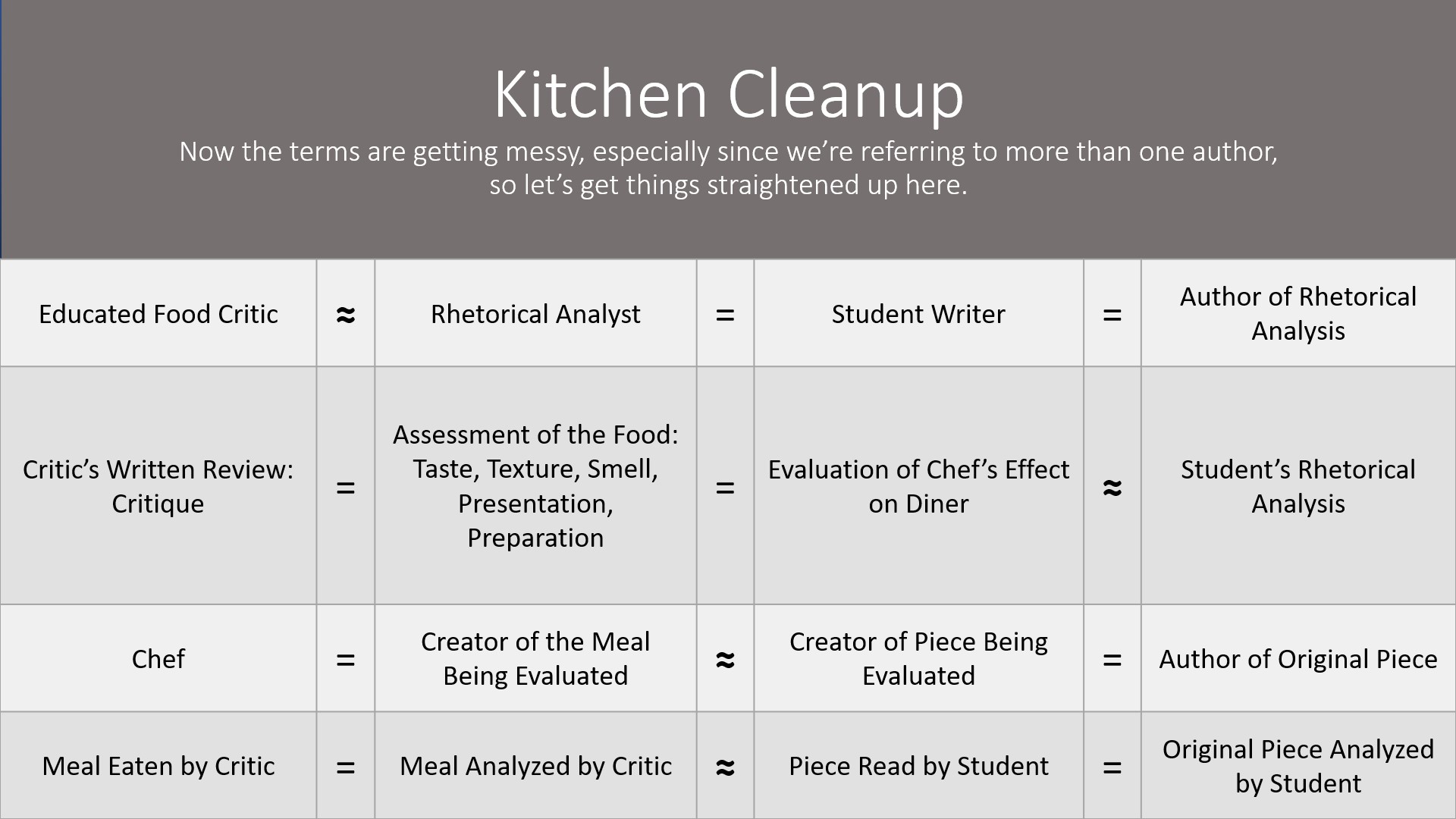

A rhetorical analysis is a type of essay that looks at a text in terms of rhetoric. This means it is less concerned with what the author is saying than with how they say it: their goals, techniques, and appeals to the audience.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Key concepts in rhetoric, analyzing the text, introducing your rhetorical analysis, the body: doing the analysis, concluding a rhetorical analysis, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about rhetorical analysis.

Rhetoric, the art of effective speaking and writing, is a subject that trains you to look at texts, arguments and speeches in terms of how they are designed to persuade the audience. This section introduces a few of the key concepts of this field.

Appeals: Logos, ethos, pathos

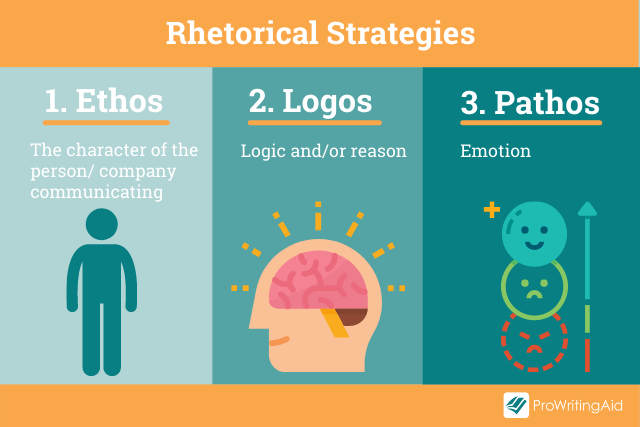

Appeals are how the author convinces their audience. Three central appeals are discussed in rhetoric, established by the philosopher Aristotle and sometimes called the rhetorical triangle: logos, ethos, and pathos.

Logos , or the logical appeal, refers to the use of reasoned argument to persuade. This is the dominant approach in academic writing , where arguments are built up using reasoning and evidence.

Ethos , or the ethical appeal, involves the author presenting themselves as an authority on their subject. For example, someone making a moral argument might highlight their own morally admirable behavior; someone speaking about a technical subject might present themselves as an expert by mentioning their qualifications.

Pathos , or the pathetic appeal, evokes the audience’s emotions. This might involve speaking in a passionate way, employing vivid imagery, or trying to provoke anger, sympathy, or any other emotional response in the audience.

These three appeals are all treated as integral parts of rhetoric, and a given author may combine all three of them to convince their audience.

Text and context

In rhetoric, a text is not necessarily a piece of writing (though it may be this). A text is whatever piece of communication you are analyzing. This could be, for example, a speech, an advertisement, or a satirical image.

In these cases, your analysis would focus on more than just language—you might look at visual or sonic elements of the text too.

The context is everything surrounding the text: Who is the author (or speaker, designer, etc.)? Who is their (intended or actual) audience? When and where was the text produced, and for what purpose?

Looking at the context can help to inform your rhetorical analysis. For example, Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech has universal power, but the context of the civil rights movement is an important part of understanding why.

Claims, supports, and warrants

A piece of rhetoric is always making some sort of argument, whether it’s a very clearly defined and logical one (e.g. in a philosophy essay) or one that the reader has to infer (e.g. in a satirical article). These arguments are built up with claims, supports, and warrants.

A claim is the fact or idea the author wants to convince the reader of. An argument might center on a single claim, or be built up out of many. Claims are usually explicitly stated, but they may also just be implied in some kinds of text.

The author uses supports to back up each claim they make. These might range from hard evidence to emotional appeals—anything that is used to convince the reader to accept a claim.

The warrant is the logic or assumption that connects a support with a claim. Outside of quite formal argumentation, the warrant is often unstated—the author assumes their audience will understand the connection without it. But that doesn’t mean you can’t still explore the implicit warrant in these cases.

For example, look at the following statement:

We can see a claim and a support here, but the warrant is implicit. Here, the warrant is the assumption that more likeable candidates would have inspired greater turnout. We might be more or less convinced by the argument depending on whether we think this is a fair assumption.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Rhetorical analysis isn’t a matter of choosing concepts in advance and applying them to a text. Instead, it starts with looking at the text in detail and asking the appropriate questions about how it works:

- What is the author’s purpose?

- Do they focus closely on their key claims, or do they discuss various topics?

- What tone do they take—angry or sympathetic? Personal or authoritative? Formal or informal?

- Who seems to be the intended audience? Is this audience likely to be successfully reached and convinced?

- What kinds of evidence are presented?

By asking these questions, you’ll discover the various rhetorical devices the text uses. Don’t feel that you have to cram in every rhetorical term you know—focus on those that are most important to the text.

The following sections show how to write the different parts of a rhetorical analysis.

Like all essays, a rhetorical analysis begins with an introduction . The introduction tells readers what text you’ll be discussing, provides relevant background information, and presents your thesis statement .

Hover over different parts of the example below to see how an introduction works.

Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech is widely regarded as one of the most important pieces of oratory in American history. Delivered in 1963 to thousands of civil rights activists outside the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., the speech has come to symbolize the spirit of the civil rights movement and even to function as a major part of the American national myth. This rhetorical analysis argues that King’s assumption of the prophetic voice, amplified by the historic size of his audience, creates a powerful sense of ethos that has retained its inspirational power over the years.

The body of your rhetorical analysis is where you’ll tackle the text directly. It’s often divided into three paragraphs, although it may be more in a longer essay.

Each paragraph should focus on a different element of the text, and they should all contribute to your overall argument for your thesis statement.

Hover over the example to explore how a typical body paragraph is constructed.

King’s speech is infused with prophetic language throughout. Even before the famous “dream” part of the speech, King’s language consistently strikes a prophetic tone. He refers to the Lincoln Memorial as a “hallowed spot” and speaks of rising “from the dark and desolate valley of segregation” to “make justice a reality for all of God’s children.” The assumption of this prophetic voice constitutes the text’s strongest ethical appeal; after linking himself with political figures like Lincoln and the Founding Fathers, King’s ethos adopts a distinctly religious tone, recalling Biblical prophets and preachers of change from across history. This adds significant force to his words; standing before an audience of hundreds of thousands, he states not just what the future should be, but what it will be: “The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.” This warning is almost apocalyptic in tone, though it concludes with the positive image of the “bright day of justice.” The power of King’s rhetoric thus stems not only from the pathos of his vision of a brighter future, but from the ethos of the prophetic voice he adopts in expressing this vision.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

The conclusion of a rhetorical analysis wraps up the essay by restating the main argument and showing how it has been developed by your analysis. It may also try to link the text, and your analysis of it, with broader concerns.

Explore the example below to get a sense of the conclusion.

It is clear from this analysis that the effectiveness of King’s rhetoric stems less from the pathetic appeal of his utopian “dream” than it does from the ethos he carefully constructs to give force to his statements. By framing contemporary upheavals as part of a prophecy whose fulfillment will result in the better future he imagines, King ensures not only the effectiveness of his words in the moment but their continuing resonance today. Even if we have not yet achieved King’s dream, we cannot deny the role his words played in setting us on the path toward it.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

The goal of a rhetorical analysis is to explain the effect a piece of writing or oratory has on its audience, how successful it is, and the devices and appeals it uses to achieve its goals.

Unlike a standard argumentative essay , it’s less about taking a position on the arguments presented, and more about exploring how they are constructed.

The term “text” in a rhetorical analysis essay refers to whatever object you’re analyzing. It’s frequently a piece of writing or a speech, but it doesn’t have to be. For example, you could also treat an advertisement or political cartoon as a text.

Logos appeals to the audience’s reason, building up logical arguments . Ethos appeals to the speaker’s status or authority, making the audience more likely to trust them. Pathos appeals to the emotions, trying to make the audience feel angry or sympathetic, for example.

Collectively, these three appeals are sometimes called the rhetorical triangle . They are central to rhetorical analysis , though a piece of rhetoric might not necessarily use all of them.

In rhetorical analysis , a claim is something the author wants the audience to believe. A support is the evidence or appeal they use to convince the reader to believe the claim. A warrant is the (often implicit) assumption that links the support with the claim.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, July 23). How to Write a Rhetorical Analysis | Key Concepts & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 15, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/rhetorical-analysis/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to write an argumentative essay | examples & tips, how to write a literary analysis essay | a step-by-step guide, comparing and contrasting in an essay | tips & examples, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Write a Rhetorical Analysis Essay–Examples & Template

What is a Rhetorical Analysis Essay?

A rhetorical analysis essay is, as the name suggests, an analysis of someone else’s writing (or speech, or advert, or even cartoon) and how they use not only words but also rhetorical techniques to influence their audience in a certain way. A rhetorical analysis is less interested in what the author is saying and more in how they present it, what effect this has on their readers, whether they achieve their goals, and what approach they use to get there.

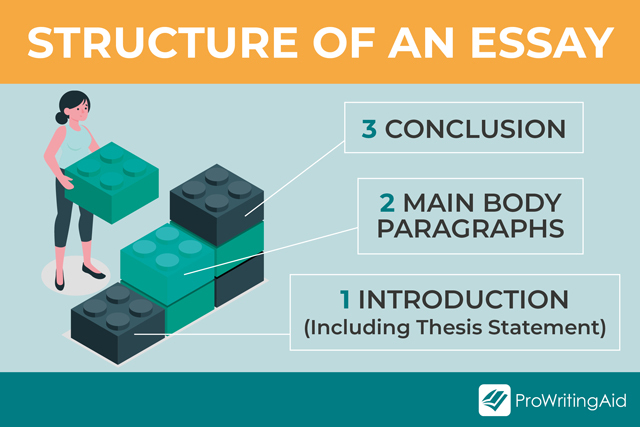

Its structure is similar to that of most essays: An Introduction presents your thesis, a Body analyzes the text you have chosen, breaks it down into sections and explains how arguments have been constructed and how each part persuades, informs, or entertains the reader, and a Conclusion section sums up your evaluation.

Note that your personal opinion on the matter is not relevant for your analysis and that you don’t state anywhere in your essay whether you agree or disagree with the stance the author takes.

In the following, we will define the key rhetorical concepts you need to write a good rhetorical analysis and give you some practical tips on where to start.

Key Rhetorical Concepts

Your goal when writing a rhetorical analysis is to think about and then carefully describe how the author has designed their text so that it has the intended effect on their audience. To do that, you need to consider a number of key rhetorical strategies: Rhetorical appeals (“Ethos”, “Logos”, and “Pathos”), context, as well as claims, supports, and warrants.

Ethos, Logos, and Pathos were introduced by Aristotle, way back in the 4th century BC, as the main ways in which language can be used to persuade an audience. They still represent the basis of any rhetorical analysis and are often referred to as the “rhetorical triangle”.

These and other rhetorical techniques can all be combined to create the intended effect, and your job as the one analyzing a text is to break the writer’s arguments down and identify the concepts they are based on.

Rhetorical Appeals

Rhetorical appeal #1: ethos.

Ethos refers to the reputation or authority of the writer regarding the topic of their essay or speech and to how they use this to appeal to their audience. Just like we are more likely to buy a product from a brand or vendor we have confidence in than one we don’t know or have reason to distrust, Ethos-driven texts or speeches rely on the reputation of the author to persuade the reader or listener. When you analyze an essay, you should therefore look at how the writer establishes Ethos through rhetorical devices.

Does the author present themselves as an authority on their subject? If so, how?

Do they highlight how impeccable their own behavior is to make a moral argument?

Do they present themselves as an expert by listing their qualifications or experience to convince the reader of their opinion on something?

Rhetorical appeal #2: Pathos

The purpose of Pathos-driven rhetoric is to appeal to the reader’s emotions. A common example of pathos as a rhetorical means is adverts by charities that try to make you donate money to a “good cause”. To evoke the intended emotions in the reader, an author may use passionate language, tell personal stories, and employ vivid imagery so that the reader can imagine themselves in a certain situation and feel empathy with or anger towards others.

Rhetorical appeal #3: Logos

Logos, the “logical” appeal, uses reason to persuade. Reason and logic, supported by data, evidence, clearly defined methodology, and well-constructed arguments, are what most academic writing is based on. Emotions, those of the researcher/writer as well as those of the reader, should stay out of such academic texts, as should anyone’s reputation, beliefs, or personal opinions.

Text and Context

To analyze a piece of writing, a speech, an advertisement, or even a satirical drawing, you need to look beyond the piece of communication and take the context in which it was created and/or published into account.

Who is the person who wrote the text/drew the cartoon/designed the ad..? What audience are they trying to reach? Where was the piece published and what was happening there around that time?

A political speech, for example, can be powerful even when read decades later, but the historical context surrounding it is an important aspect of the effect it was intended to have.

Claims, Supports, and Warrants

To make any kind of argument, a writer needs to put forward specific claims, support them with data or evidence or even a moral or emotional appeal, and connect the dots logically so that the reader can follow along and agree with the points made.

The connections between statements, so-called “warrants”, follow logical reasoning but are not always clearly stated—the author simply assumes the reader understands the underlying logic, whether they present it “explicitly” or “implicitly”. Implicit warrants are commonly used in advertisements where seemingly happy people use certain products, wear certain clothes, accessories, or perfumes, or live certain lifestyles – with the connotation that, first, the product/perfume/lifestyle is what makes that person happy and, second, the reader wants to be as happy as the person in the ad. Some warrants are never clearly stated, and your job when writing a rhetorical analysis essay is therefore to identify them and bring them to light, to evaluate their validity, their effect on the reader, and the use of such means by the writer/creator.

What are the Five Rhetorical Situations?

A “rhetorical situation” refers to the circumstance behind a text or other piece of communication that arises from a given context. It explains why a rhetorical piece was created, what its purpose is, and how it was constructed to achieve its aims.

Rhetorical situations can be classified into the following five categories:

Asking such questions when you analyze a text will help you identify all the aspects that play a role in the effect it has on its audience, and will allow you to evaluate whether it achieved its aims or where it may have failed to do so.

Rhetorical Analysis Essay Outline

Analyzing someone else’s work can seem like a big task, but as with every assignment or writing endeavor, you can break it down into smaller, well-defined steps that give you a practical structure to follow.

To give you an example of how the different parts of your text may look when it’s finished, we will provide you with some excerpts from this rhetorical analysis essay example (which even includes helpful comments) published on the Online Writing Lab website of Excelsior University in Albany, NY. The text that this essay analyzes is this article on why one should or shouldn’t buy an Ipad. If you want more examples so that you can build your own rhetorical analysis template, have a look at this essay on Nabokov’s Lolita and the one provided here about the “Shitty First Drafts” chapter of Anne Lamott’s writing instruction book “Bird by Bird”.

Analyzing the Text

When writing a rhetorical analysis, you don’t choose the concepts or key points you think are relevant or want to address. Rather, you carefully read the text several times asking yourself questions like those listed in the last section on rhetorical situations to identify how the text “works” and how it was written to achieve that effect.

Start with focusing on the author : What do you think was their purpose for writing the text? Do they make one principal claim and then elaborate on that? Or do they discuss different topics?

Then look at what audience they are talking to: Do they want to make a group of people take some action? Vote for someone? Donate money to a good cause? Who are these people? Is the text reaching this specific audience? Why or why not?

What tone is the author using to address their audience? Are they trying to evoke sympathy? Stir up anger? Are they writing from a personal perspective? Are they painting themselves as an authority on the topic? Are they using academic or informal language?

How does the author support their claims ? What kind of evidence are they presenting? Are they providing explicit or implicit warrants? Are these warrants valid or problematic? Is the provided evidence convincing?

Asking yourself such questions will help you identify what rhetorical devices a text uses and how well they are put together to achieve a certain aim. Remember, your own opinion and whether you agree with the author are not the point of a rhetorical analysis essay – your task is simply to take the text apart and evaluate it.

If you are still confused about how to write a rhetorical analysis essay, just follow the steps outlined below to write the different parts of your rhetorical analysis: As every other essay, it consists of an Introduction , a Body (the actual analysis), and a Conclusion .

Rhetorical Analysis Introduction

The Introduction section briefly presents the topic of the essay you are analyzing, the author, their main claims, a short summary of the work by you, and your thesis statement .

Tell the reader what the text you are going to analyze represents (e.g., historically) or why it is relevant (e.g., because it has become some kind of reference for how something is done). Describe what the author claims, asserts, or implies and what techniques they use to make their argument and persuade their audience. Finish off with your thesis statement that prepares the reader for what you are going to present in the next section – do you think that the author’s assumptions/claims/arguments were presented in a logical/appealing/powerful way and reached their audience as intended?

Have a look at an excerpt from the sample essay linked above to see what a rhetorical analysis introduction can look like. See how it introduces the author and article , the context in which it originally appeared , the main claims the author makes , and how this first paragraph ends in a clear thesis statement that the essay will then elaborate on in the following Body section:

Cory Doctorow ’s article on BoingBoing is an older review of the iPad , one of Apple’s most famous products. At the time of this article, however, the iPad was simply the latest Apple product to hit the market and was not yet so popular. Doctorow’s entire career has been entrenched in and around technology. He got his start as a CD-ROM programmer and is now a successful blogger and author. He is currently the co-editor of the BoingBoing blog on which this article was posted. One of his main points in this article comes from Doctorow’s passionate advocacy of free digital media sharing. He argues that the iPad is just another way for established technology companies to control our technological freedom and creativity . In “ Why I Won’t Buy an iPad (and Think You Shouldn’t, Either) ” published on Boing Boing in April of 2010, Cory Doctorow successfully uses his experience with technology, facts about the company Apple, and appeals to consumer needs to convince potential iPad buyers that Apple and its products, specifically the iPad, limit the digital rights of those who use them by controlling and mainstreaming the content that can be used and created on the device .

Doing the Rhetorical Analysis

The main part of your analysis is the Body , where you dissect the text in detail. Explain what methods the author uses to inform, entertain, and/or persuade the audience. Use Aristotle’s rhetorical triangle and the other key concepts we introduced above. Use quotations from the essay to demonstrate what you mean. Work out why the writer used a certain approach and evaluate (and again, demonstrate using the text itself) how successful they were. Evaluate the effect of each rhetorical technique you identify on the audience and judge whether the effect is in line with the author’s intentions.

To make it easy for the reader to follow your thought process, divide this part of your essay into paragraphs that each focus on one strategy or one concept , and make sure they are all necessary and contribute to the development of your argument(s).

One paragraph of this section of your essay could, for example, look like this:

One example of Doctorow’s position is his comparison of Apple’s iStore to Wal-Mart. This is an appeal to the consumer’s logic—or an appeal to logos. Doctorow wants the reader to take his comparison and consider how an all-powerful corporation like the iStore will affect them. An iPad will only allow for apps and programs purchased through the iStore to be run on it; therefore, a customer must not only purchase an iPad but also any programs he or she wishes to use. Customers cannot create their own programs or modify the hardware in any way.

As you can see, the author of this sample essay identifies and then explains to the reader how Doctorow uses the concept of Logos to appeal to his readers – not just by pointing out that he does it but by dissecting how it is done.

Rhetorical Analysis Conclusion

The conclusion section of your analysis should restate your main arguments and emphasize once more whether you think the author achieved their goal. Note that this is not the place to introduce new information—only rely on the points you have discussed in the body of your essay. End with a statement that sums up the impact the text has on its audience and maybe society as a whole:

Overall, Doctorow makes a good argument about why there are potentially many better things to drop a great deal of money on instead of the iPad. He gives some valuable information and facts that consumers should take into consideration before going out to purchase the new device. He clearly uses rhetorical tools to help make his case, and, overall, he is effective as a writer, even if, ultimately, he was ineffective in convincing the world not to buy an iPad .

Frequently Asked Questions about Rhetorical Analysis Essays

What is a rhetorical analysis essay.

A rhetorical analysis dissects a text or another piece of communication to work out and explain how it impacts its audience, how successfully it achieves its aims, and what rhetorical devices it uses to do that.

While argumentative essays usually take a stance on a certain topic and argue for it, a rhetorical analysis identifies how someone else constructs their arguments and supports their claims.

What is the correct rhetorical analysis essay format?

Like most other essays, a rhetorical analysis contains an Introduction that presents the thesis statement, a Body that analyzes the piece of communication, explains how arguments have been constructed, and illustrates how each part persuades, informs, or entertains the reader, and a Conclusion section that summarizes the results of the analysis.

What is the “rhetorical triangle”?

The rhetorical triangle was introduced by Aristotle as the main ways in which language can be used to persuade an audience: Logos appeals to the audience’s reason, Ethos to the writer’s status or authority, and Pathos to the reader’s emotions. Logos, Ethos, and Pathos can all be combined to create the intended effect, and your job as the one analyzing a text is to break the writer’s arguments down and identify what specific concepts each is based on.

Let Wordvice help you write a flawless rhetorical analysis essay!

Whether you have to write a rhetorical analysis essay as an assignment or whether it is part of an application, our professional proofreading services feature professional editors are trained subject experts that make sure your text is in line with the required format, as well as help you improve the flow and expression of your writing. Let them be your second pair of eyes so that after receiving paper editing services or essay editing services from Wordvice, you can submit your manuscript or apply to the school of your dreams with confidence.

And check out our editing services for writers (including blog editing , script editing , and book editing ) to correct your important personal or business-related work.

How to Write the AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Essay (With Example)

November 27, 2023

Feeling intimidated by the AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Essay? We’re here to help demystify. Whether you’re cramming for the AP Lang exam right now or planning to take the test down the road, we’ve got crucial rubric information, helpful tips, and an essay example to prepare you for the big day. This post will cover 1) What is the AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Essay? 2) AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Rubric 3) AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis: Sample Prompt 4) AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Essay Example 5)AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Essay Example: Why It Works

What is the AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Essay?

The AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Essay is one of three essays included in the written portion of the AP English Exam. The full AP English Exam is 3 hours and 15 minutes long, with the first 60 minutes dedicated to multiple-choice questions. Once you complete the multiple-choice section, you move on to three equally weighted essays that ask you to synthesize, analyze, and interpret texts and develop well-reasoned arguments. The three essays include:

Synthesis essay: You’ll review various pieces of evidence and then write an essay that synthesizes (aka combines and interprets) the evidence and presents a clear argument. Read our write up on How to Write the AP Lang Synthesis Essay here.

Argumentative essay: You’ll take a stance on a specific topic and argue your case.

Rhetorical essay: You’ll read a provided passage, then analyze the author’s rhetorical choices and develop an argument that explains why the author made those rhetorical choices.

AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Rubric

The AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Essay is graded on just 3 rubric categories: Thesis, Evidence and Commentary, and Sophistication . At a glance, the rubric categories may seem vague, but AP exam graders are actually looking for very particular things in each category. We’ll break it down with dos and don’ts for each rubric category:

Thesis (0-1 point)

There’s nothing nebulous when it comes to grading AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Essay thesis. You either have one or you don’t. Including a thesis gets you one point closer to a high score and leaving it out means you miss out on one crucial point. So, what makes a thesis that counts?

- Make sure your thesis argues something about the author’s rhetorical choices. Making an argument means taking a risk and offering your own interpretation of the provided text. This is an argument that someone else might disagree with.

- A good test to see if you have a thesis that makes an argument. In your head, add the phrase “I think that…” to the beginning of your thesis. If what follows doesn’t logically flow after that phrase (aka if what follows isn’t something you and only you think), it’s likely you’re not making an argument.

- Avoid a thesis that merely restates the prompt.

- Avoid a thesis that summarizes the text but does not make an argument.

Evidence and Commentary (0-4 points)

This rubric category is graded on a scale of 0-4 where 4 is the highest grade. Per the AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis rubric, to get a 4, you’ll want to:

- Include lots of specific evidence from the text. There is no set golden number of quotes to include, but you’ll want to make sure you’re incorporating more than a couple pieces of evidence that support your argument about the author’s rhetorical choices.

- Make sure you include more than one type of evidence, too. Let’s say you’re working on your essay and have gathered examples of alliteration to include as supporting evidence. That’s just one type of rhetorical choice, and it’s hard to make a credible argument if you’re only looking at one type of evidence. To fix that issue, reread the text again looking for patterns in word choice and syntax, meaningful figurative language and imagery, literary devices, and other rhetorical choices, looking for additional types of evidence to support your argument.

- After you include evidence, offer your own interpretation and explain how this evidence proves the point you make in your thesis.

- Don’t summarize or speak generally about the author and the text. Everything you write must be backed up with evidence.

- Don’t let quotes speak for themselves. After every piece of evidence you include, make sure to explain your interpretation. Also, connect the evidence to your overarching argument.

Sophistication (0-1 point)

In this case, sophistication isn’t about how many fancy vocabulary words or how many semicolons you use. According to College Board , one point can be awarded to AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis essays that “demonstrate sophistication of thought and/or a complex understanding of the rhetorical situation” in any of these three ways:

- Explaining the significance or relevance of the writer’s rhetorical choices.

- Explaining the purpose or function of the passage’s complexities or tensions.

- Employing a style that is consistently vivid and persuasive.

Note that you don’t have to achieve all three to earn your sophistication point. A good way to think of this rubric category is to consider it a bonus point that you can earn for going above and beyond in depth of analysis or by writing an especially persuasive, clear, and well-structured essay. In order to earn this point, you’ll need to first do a good job with your thesis, evidence, and commentary.

- Focus on nailing an argumentative thesis and multiple types of evidence. Getting these fundamentals of your essay right will set you up for achieving depth of analysis.

- Explain how each piece of evidence connects to your thesis.

- Spend a minute outlining your essay before you begin to ensure your essay flows in a clear and cohesive way.

- Steer clear of generalizations about the author or text.

- Don’t include arguments you can’t prove with evidence from the text.

- Avoid complex sentences and fancy vocabulary words unless you use them often. Long, clunky sentences with imprecisely used words are hard to follow.

AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis: Sample Prompt

The sample prompt below is published online by College Board and is a real example from the 2021 AP Exam. The prompt provides background context, essay instructions, and the text you need to analyze. For sake of space, we’ve included the text as an image you can click to read. After the prompt, we provide a sample high scoring essay and then explain why this AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis essay example works.

Suggested time—40 minutes.

(This question counts as one-third of the total essay section score.)

On February 27, 2013, while in office, former president Barack Obama delivered the following address dedicating the Rosa Parks statue in the National Statuary Hall of the United States Capitol building. Rosa Parks was an African American civil rights activist who was arrested in 1955 for refusing to give up her seat on a segregated bus in Montgomery, Alabama. Read the passage carefully. Write an essay that analyzes the rhetorical choices Obama makes to convey his message.

In your response you should do the following:

- Respond to the prompt with a thesis that analyzes the writer’s rhetorical choices.

- Select and use evidence to support your line of reasoning.

- Explain how the evidence supports your line of reasoning.

- Demonstrate an understanding of the rhetorical situation.

- Use appropriate grammar and punctuation in communicating your argument.

AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Essay Example

In his speech delivered in 2013 at the dedication of Rosa Park’s statue, President Barack Obama acknowledges everything that Parks’ activism made possible in the United States. Telling the story of Parks’ life and achievements, Obama highlights the fact that Parks was a regular person whose actions accomplished enormous change during the civil rights era. Through the use of diction that portrays Parks as quiet and demure, long lists that emphasize the extent of her impacts, and Biblical references, Obama suggests that all of us are capable of achieving greater good, just as Parks did.

Although it might be a surprising way to start to his dedication, Obama begins his speech by telling us who Parks was not: “Rosa Parks held no elected office. She possessed no fortune” he explains in lines 1-2. Later, when he tells the story of the bus driver who threatened to have Parks arrested when she refused to get off the bus, he explains that Parks “simply replied, ‘You may do that’” (lines 22-23). Right away, he establishes that Parks was a regular person who did not hold a seat of power. Her protest on the bus was not part of a larger plan, it was a simple response. By emphasizing that Parks was not powerful, wealthy, or loud spoken, he implies that Parks’ style of activism is an everyday practice that all of us can aspire to.

AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Essay Example (Continued)

Even though Obama portrays Parks as a demure person whose protest came “simply” and naturally, he shows the importance of her activism through long lists of ripple effects. When Parks challenged her arrest, Obama explains, Martin Luther King, Jr. stood with her and “so did thousands of Montgomery, Alabama commuters” (lines 27-28). They began a boycott that included “teachers and laborers, clergy and domestics, through rain and cold and sweltering heat, day after day, week after week, month after month, walking miles if they had to…” (lines 28-31). In this section of the speech, Obama’s sentences grow longer and he uses lists to show that Parks’ small action impacted and inspired many others to fight for change. Further, listing out how many days, weeks, and months the boycott lasted shows how Parks’ single act of protest sparked a much longer push for change.

To further illustrate Parks’ impact, Obama incorporates Biblical references that emphasize the importance of “that single moment on the bus” (lines 57-58). In lines 33-35, Obama explains that Parks and the other protestors are “driven by a solemn determination to affirm their God-given dignity” and he also compares their victory to the fall the “ancient walls of Jericho” (line 43). By of including these Biblical references, Obama suggests that Parks’ action on the bus did more than correct personal or political wrongs; it also corrected moral and spiritual wrongs. Although Parks had no political power or fortune, she was able to restore a moral balance in our world.

Toward the end of the speech, Obama states that change happens “not mainly through the exploits of the famous and the powerful, but through the countless acts of often anonymous courage and kindness” (lines 78-81). Through carefully chosen diction that portrays her as a quiet, regular person and through lists and Biblical references that highlight the huge impacts of her action, Obama illustrates exactly this point. He wants us to see that, just like Parks, the small and meek can change the world for the better.

AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Essay Example: Why It Works

We would give the AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis essay above a score of 6 out of 6 because it fully satisfies the essay’s 3 rubric categories: Thesis, Evidence and Commentary, and Sophistication . Let’s break down what this student did:

The thesis of this essay appears in the last line of the first paragraph:

“ Through the use of diction that portrays Parks as quiet and demure, long lists that emphasize the extent of her impacts, and Biblical references, Obama suggests that all of us are capable of achieving greater good, just as Parks did .”

This student’s thesis works because they make a clear argument about Obama’s rhetorical choices. They 1) list the rhetorical choices that will be analyzed in the rest of the essay (the italicized text above) and 2) include an argument someone else might disagree with (the bolded text above).

Evidence and Commentary:

This student includes substantial evidence and commentary. Things they do right, per the AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis rubric:

- They include lots of specific evidence from the text in the form of quotes.

- They incorporate 3 different types of evidence (diction, long lists, Biblical references).

- After including evidence, they offer an interpretation of what the evidence means and explain how the evidence contributes to their overarching argument (aka their thesis).

Sophistication

This essay achieves sophistication according to the AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis essay rubric in a few key ways:

- This student provides an introduction that flows naturally into the topic their essay will discuss. Before they get to their thesis, they tell us that Obama portrays Parks as a “regular person” setting up their main argument: Obama wants all regular people to aspire to do good in the world just as Rosa Parks did.

- They organize evidence and commentary in a clear and cohesive way. Each body paragraph focuses on just one type of evidence.

- They explain how their evidence is significant. In the final sentence of each body paragraph, they draw a connection back to the overarching argument presented in the thesis.

- All their evidence supports the argument presented in their thesis. There is no extraneous evidence or misleading detail.

- They consider nuances in the text. Rather than taking the text at face value, they consider what Obama’s rhetorical choices imply and offer their own unique interpretation of those implications.

- In their final paragraph, they come full circle, reiterate their thesis, and explain what Obama’s rhetorical choices communicate to readers.

- Their sentences are clear and easy to read. There are no grammar errors or misused words.

AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Essay—More Resources

Looking for more tips to help your master your AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Essay? Brush up on 20 Rhetorical Devices High School Students Should Know and read our Tips for Improving Reading Comprehension . If you’re ready to start studying for another part of the AP English Exam, find more expert tips in our How to Write the AP Lang Synthesis blog post.

Considering what other AP classes to take? Read up on the Hardest AP Classes .

- High School Success

Christina Wood

Christina Wood holds a BA in Literature & Writing from UC San Diego, an MFA in Creative Writing from Washington University in St. Louis, and is currently a Doctoral Candidate in English at the University of Georgia, where she teaches creative writing and first-year composition courses. Christina has published fiction and nonfiction in numerous publications, including The Paris Review , McSweeney’s , Granta , Virginia Quarterly Review , The Sewanee Review , Mississippi Review , and Puerto del Sol , among others. Her story “The Astronaut” won the 2018 Shirley Jackson Award for short fiction and received a “Distinguished Stories” mention in the 2019 Best American Short Stories anthology.

- 2-Year Colleges

- Application Strategies

- Best Colleges by Major

- Best Colleges by State

- Big Picture

- Career & Personality Assessment

- College Essay

- College Search/Knowledge

- College Success

- Costs & Financial Aid

- Dental School Admissions

- Extracurricular Activities

- Graduate School Admissions

- High Schools

- Law School Admissions

- Medical School Admissions

- Navigating the Admissions Process

- Online Learning

- Private High School Spotlight

- Summer Program Spotlight

- Summer Programs

- Test Prep Provider Spotlight

“Innovative and invaluable…use this book as your college lifeline.”

— Lynn O'Shaughnessy

Nationally Recognized College Expert

College Planning in Your Inbox

Join our information-packed monthly newsletter.

I am a... Student Student Parent Counselor Educator Other First Name Last Name Email Address Zip Code Area of Interest Business Computer Science Engineering Fine/Performing Arts Humanities Mathematics STEM Pre-Med Psychology Social Studies/Sciences Submit

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

What Is a Rhetorical Analysis and How to Write a Great One

Helly Douglas

Do you have to write a rhetorical analysis essay? Fear not! We’re here to explain exactly what rhetorical analysis means, how you should structure your essay, and give you some essential “dos and don’ts.”

What is a Rhetorical Analysis Essay?

How do you write a rhetorical analysis, what are the three rhetorical strategies, what are the five rhetorical situations, how to plan a rhetorical analysis essay, creating a rhetorical analysis essay, examples of great rhetorical analysis essays, final thoughts.

A rhetorical analysis essay studies how writers and speakers have used words to influence their audience. Think less about the words the author has used and more about the techniques they employ, their goals, and the effect this has on the audience.

In your analysis essay, you break a piece of text (including cartoons, adverts, and speeches) into sections and explain how each part works to persuade, inform, or entertain. You’ll explore the effectiveness of the techniques used, how the argument has been constructed, and give examples from the text.

A strong rhetorical analysis evaluates a text rather than just describes the techniques used. You don’t include whether you personally agree or disagree with the argument.

Structure a rhetorical analysis in the same way as most other types of academic essays . You’ll have an introduction to present your thesis, a main body where you analyze the text, which then leads to a conclusion.

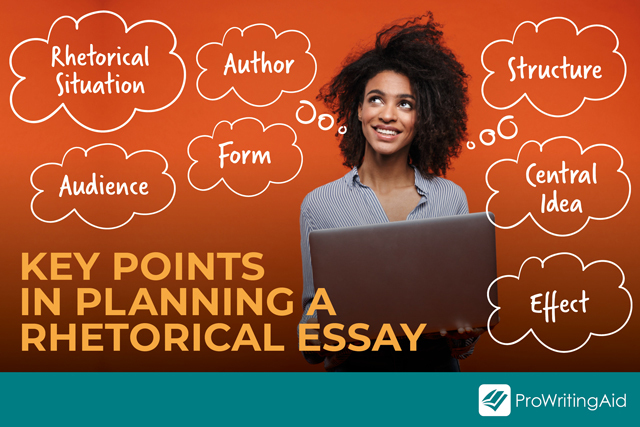

Think about how the writer (also known as a rhetor) considers the situation that frames their communication:

- Topic: the overall purpose of the rhetoric

- Audience: this includes primary, secondary, and tertiary audiences

- Purpose: there are often more than one to consider

- Context and culture: the wider situation within which the rhetoric is placed

Back in the 4th century BC, Aristotle was talking about how language can be used as a means of persuasion. He described three principal forms —Ethos, Logos, and Pathos—often referred to as the Rhetorical Triangle . These persuasive techniques are still used today.

Rhetorical Strategy 1: Ethos

Are you more likely to buy a car from an established company that’s been an important part of your community for 50 years, or someone new who just started their business?

Reputation matters. Ethos explores how the character, disposition, and fundamental values of the author create appeal, along with their expertise and knowledge in the subject area.

Aristotle breaks ethos down into three further categories:

- Phronesis: skills and practical wisdom

- Arete: virtue

- Eunoia: goodwill towards the audience

Ethos-driven speeches and text rely on the reputation of the author. In your analysis, you can look at how the writer establishes ethos through both direct and indirect means.

Rhetorical Strategy 2: Pathos

Pathos-driven rhetoric hooks into our emotions. You’ll often see it used in advertisements, particularly by charities wanting you to donate money towards an appeal.

Common use of pathos includes:

- Vivid description so the reader can imagine themselves in the situation

- Personal stories to create feelings of empathy

- Emotional vocabulary that evokes a response

By using pathos to make the audience feel a particular emotion, the author can persuade them that the argument they’re making is compelling.

Rhetorical Strategy 3: Logos

Logos uses logic or reason. It’s commonly used in academic writing when arguments are created using evidence and reasoning rather than an emotional response. It’s constructed in a step-by-step approach that builds methodically to create a powerful effect upon the reader.

Rhetoric can use any one of these three techniques, but effective arguments often appeal to all three elements.

The rhetorical situation explains the circumstances behind and around a piece of rhetoric. It helps you think about why a text exists, its purpose, and how it’s carried out.

The rhetorical situations are:

- 1) Purpose: Why is this being written? (It could be trying to inform, persuade, instruct, or entertain.)

- 2) Audience: Which groups or individuals will read and take action (or have done so in the past)?

- 3) Genre: What type of writing is this?

- 4) Stance: What is the tone of the text? What position are they taking?

- 5) Media/Visuals: What means of communication are used?

Understanding and analyzing the rhetorical situation is essential for building a strong essay. Also think about any rhetoric restraints on the text, such as beliefs, attitudes, and traditions that could affect the author's decisions.

Before leaping into your essay, it’s worth taking time to explore the text at a deeper level and considering the rhetorical situations we looked at before. Throw away your assumptions and use these simple questions to help you unpick how and why the text is having an effect on the audience.

1: What is the Rhetorical Situation?

- Why is there a need or opportunity for persuasion?

- How do words and references help you identify the time and location?

- What are the rhetoric restraints?

- What historical occasions would lead to this text being created?

2: Who is the Author?

- How do they position themselves as an expert worth listening to?

- What is their ethos?

- Do they have a reputation that gives them authority?

- What is their intention?

- What values or customs do they have?

3: Who is it Written For?

- Who is the intended audience?

- How is this appealing to this particular audience?

- Who are the possible secondary and tertiary audiences?

4: What is the Central Idea?

- Can you summarize the key point of this rhetoric?

- What arguments are used?

- How has it developed a line of reasoning?

5: How is it Structured?

- What structure is used?

- How is the content arranged within the structure?

6: What Form is Used?

- Does this follow a specific literary genre?

- What type of style and tone is used, and why is this?

- Does the form used complement the content?

- What effect could this form have on the audience?

7: Is the Rhetoric Effective?

- Does the content fulfil the author’s intentions?

- Does the message effectively fit the audience, location, and time period?

Once you’ve fully explored the text, you’ll have a better understanding of the impact it’s having on the audience and feel more confident about writing your essay outline.

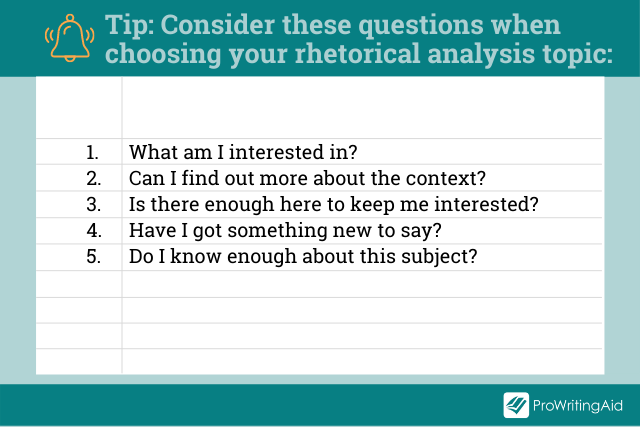

A great essay starts with an interesting topic. Choose carefully so you’re personally invested in the subject and familiar with it rather than just following trending topics. There are lots of great ideas on this blog post by My Perfect Words if you need some inspiration. Take some time to do background research to ensure your topic offers good analysis opportunities.

Remember to check the information given to you by your professor so you follow their preferred style guidelines. This outline example gives you a general idea of a format to follow, but there will likely be specific requests about layout and content in your course handbook. It’s always worth asking your institution if you’re unsure.

Make notes for each section of your essay before you write. This makes it easy for you to write a well-structured text that flows naturally to a conclusion. You will develop each note into a paragraph. Look at this example by College Essay for useful ideas about the structure.

1: Introduction

This is a short, informative section that shows you understand the purpose of the text. It tempts the reader to find out more by mentioning what will come in the main body of your essay.

- Name the author of the text and the title of their work followed by the date in parentheses

- Use a verb to describe what the author does, e.g. “implies,” “asserts,” or “claims”

- Briefly summarize the text in your own words

- Mention the persuasive techniques used by the rhetor and its effect

Create a thesis statement to come at the end of your introduction.

After your introduction, move on to your critical analysis. This is the principal part of your essay.

- Explain the methods used by the author to inform, entertain, and/or persuade the audience using Aristotle's rhetorical triangle

- Use quotations to prove the statements you make

- Explain why the writer used this approach and how successful it is

- Consider how it makes the audience feel and react

Make each strategy a new paragraph rather than cramming them together, and always use proper citations. Check back to your course handbook if you’re unsure which citation style is preferred.

3: Conclusion

Your conclusion should summarize the points you’ve made in the main body of your essay. While you will draw the points together, this is not the place to introduce new information you’ve not previously mentioned.

Use your last sentence to share a powerful concluding statement that talks about the impact the text has on the audience(s) and wider society. How have its strategies helped to shape history?

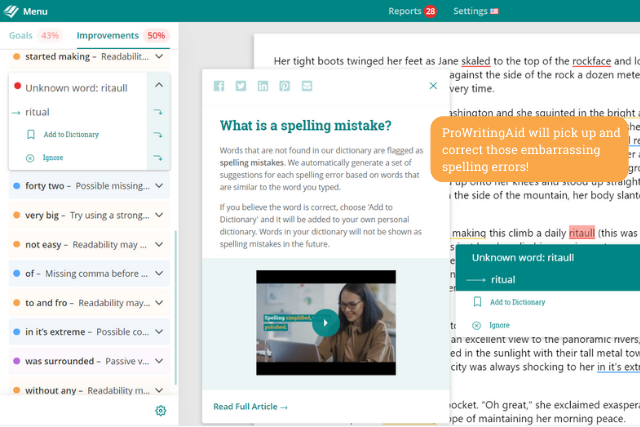

Before You Submit

Poor spelling and grammatical errors ruin a great essay. Use ProWritingAid to check through your finished essay before you submit. It will pick up all the minor errors you’ve missed and help you give your essay a final polish. Look at this useful ProWritingAid webinar for further ideas to help you significantly improve your essays. Sign up for a free trial today and start editing your essays!

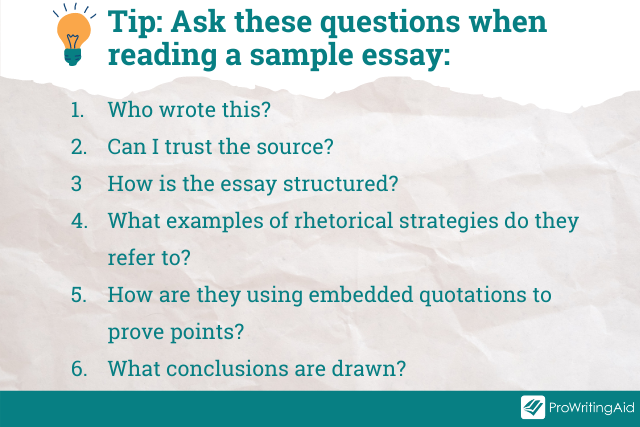

You’ll find countless examples of rhetorical analysis online, but they range widely in quality. Your institution may have example essays they can share with you to show you exactly what they’re looking for.

The following links should give you a good starting point if you’re looking for ideas:

Pearson Canada has a range of good examples. Look at how embedded quotations are used to prove the points being made. The end questions help you unpick how successful each essay is.

Excelsior College has an excellent sample essay complete with useful comments highlighting the techniques used.

Brighton Online has a selection of interesting essays to look at. In this specific example, consider how wider reading has deepened the exploration of the text.

Writing a rhetorical analysis essay can seem daunting, but spending significant time deeply analyzing the text before you write will make it far more achievable and result in a better-quality essay overall.

It can take some time to write a good essay. Aim to complete it well before the deadline so you don’t feel rushed. Use ProWritingAid’s comprehensive checks to find any errors and make changes to improve readability. Then you’ll be ready to submit your finished essay, knowing it’s as good as you can possibly make it.

Try ProWritingAid's Editor for Yourself

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

Helly Douglas is a UK writer and teacher, specialising in education, children, and parenting. She loves making the complex seem simple through blogs, articles, and curriculum content. You can check out her work at hellydouglas.com or connect on Twitter @hellydouglas. When she’s not writing, you will find her in a classroom, being a mum or battling against the wilderness of her garden—the garden is winning!

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

9.5 Writing Process: Thinking Critically about Rhetoric

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Develop a rhetorical analysis through multiple drafts.

- Identify and analyze rhetorical strategies in a rhetorical analysis.

- Demonstrate flexible strategies for generating ideas, drafting, reviewing, collaborating, revising, rewriting, and editing.

- Give and act on productive feedback for works in progress.

The ability to think critically about rhetoric is a skill you will use in many of your classes, in your work, and in your life to gain insight from the way a text is written and organized. You will often be asked to explain or to express an opinion about what someone else has communicated and how that person has done so, especially if you take an active interest in politics and government. Like Eliana Evans in the previous section, you will develop similar analyses of written works to help others understand how a writer or speaker may be trying to reach them.

Summary of Assignment: Rhetorical Analysis

The assignment is to write a rhetorical analysis of a piece of persuasive writing. It can be an editorial, a movie or book review, an essay, a chapter in a book, or a letter to the editor. For your rhetorical analysis, you will need to consider the rhetorical situation—subject, author, purpose, context, audience, and culture—and the strategies the author uses in creating the argument. Back up all your claims with evidence from the text. In preparing your analysis, consider these questions:

- What is the subject? Be sure to distinguish what the piece is about.

- Who is the writer, and what do you know about them? Be sure you know whether the writer is considered objective or has a particular agenda.

- Who are the readers? What do you know or what can you find out about them as the particular audience to be addressed at this moment?

- What is the purpose or aim of this work? What does the author hope to achieve?

- What are the time/space/place considerations and influences of the writer? What can you know about the writer and the full context in which they are writing?

- What specific techniques has the writer used to make their points? Are these techniques successful, unsuccessful, or questionable?

For this assignment, read the following opinion piece by Octavio Peterson, printed in his local newspaper. You may choose it as the text you will analyze, continuing the analysis on your own, or you may refer to it as a sample as you work on another text of your choosing. Your instructor may suggest presidential or other political speeches, which make good subjects for rhetorical analysis.

When you have read the piece by Peterson advocating for the need to continue teaching foreign languages in schools, reflect carefully on the impact the letter has had on you. You are not expected to agree or disagree with it. Instead, focus on the rhetoric—the way Peterson uses language to make his point and convince you of the validity of his argument.

Another Lens. Consider presenting your rhetorical analysis in a multimodal format. Use a blogging site or platform such as WordPress or Tumblr to explore the blogging genre, which includes video clips, images, hyperlinks, and other media to further your discussion. Because this genre is less formal than written text, your tone can be conversational. However, you still will be required to provide the same kind of analysis that you would in a traditional essay. The same materials will be at your disposal for making appeals to persuade your readers. Rhetorical analysis in a blog may be a new forum for the exchange of ideas that retains the basics of more formal communication. When you have completed your work, share it with a small group or the rest of the class. See Multimodal and Online Writing: Creative Interaction between Text and Image for more about creating a multimodal composition.

Quick Launch: Start with a Thesis Statement

After you have read this opinion piece, or another of your choice, several times and have a clear understanding of it as a piece of rhetoric, consider whether the writer has succeeded in being persuasive. You might find that in some ways they have and in others they have not. Then, with a clear understanding of your purpose—to analyze how the writer seeks to persuade—you can start framing a thesis statement : a declarative sentence that states the topic, the angle you are taking, and the aspects of the topic the rest of the paper will support.

Complete the following sentence frames as you prepare to start:

- The subject of my rhetorical analysis is ________.

- My goal is to ________, not necessarily to ________.

- The writer’s main point is ________.

- I believe the writer has succeeded (or not) because ________.

- I believe the writer has succeeded in ________ (name the part or parts) but not in ________ (name the part or parts).

- The writer’s strongest (or weakest) point is ________, which they present by ________.

Drafting: Text Evidence and Analysis of Effect

As you begin to draft your rhetorical analysis, remember that you are giving your opinion on the author’s use of language. For example, Peterson has made a decision about the teaching of foreign languages, something readers of the newspaper might have different views on. In other words, there is room for debate and persuasion.

The context of the situation in which Peterson finds himself may well be more complex than he discusses. In the same way, the context of the piece you choose to analyze may also be more complex. For example, perhaps Greendale is facing an economic crisis and must pare its budget for educational spending and public works. It’s also possible that elected officials have made budget cuts for education a part of their platform or that school buildings have been found obsolete for safety measures. On the other hand, maybe a foreign company will come to town only if more Spanish speakers can be found locally. These factors would play a part in a real situation, and rhetoric would reflect that. If applicable, consider such possibilities regarding the subject of your analysis. Here, however, these factors are unknown and thus do not enter into the analysis.

Introduction

One effective way to begin a rhetorical analysis is by using an anecdote, as Eliana Evans has done. For a rhetorical analysis of the opinion piece, a writer might consider an anecdote about a person who was in a situation in which knowing another language was important or not important. If they begin with an anecdote, the next part of the introduction should contain the following information:

- Author’s name and position, or other qualification to establish ethos

- Title of work and genre

- Author’s thesis statement or stance taken (“Peterson argues that . . .”)

- Brief introductory explanation of how the author develops and supports the thesis or stance

- If relevant, a brief summary of context and culture

Once the context and situation for the analysis are clear, move directly to your thesis statement. In this case, your thesis statement will be your opinion of how successful the author has been in achieving the established goal through the use of rhetorical strategies. Read the sentences in Table 9.1 , and decide which would make the best thesis statement. Explain your reasoning in the right-hand column of this or a similar chart.

The introductory paragraph or paragraphs should serve to move the reader into the body of the analysis and signal what will follow.

Your next step is to start supporting your thesis statement—that is, how Octavio Peterson, or the writer of your choice, does or does not succeed in persuading readers. To accomplish this purpose, you need to look closely at the rhetorical strategies the writer uses.

First, list the rhetorical strategies you notice while reading the text, and note where they appear. Keep in mind that you do not need to include every strategy the text contains, only those essential ones that emphasize or support the central argument and those that may seem fallacious. You may add other strategies as well. The first example in Table 9.2 has been filled in.

When you have completed your list, consider how to structure your analysis. You will have to decide which of the writer’s statements are most effective. The strongest point would be a good place to begin; conversely, you could begin with the writer’s weakest point if that suits your purposes better. The most obvious organizational structure is one of the following:

- Go through the composition paragraph by paragraph and analyze its rhetorical content, focusing on the strategies that support the writer’s thesis statement.

- Address key rhetorical strategies individually, and show how the author has used them.

As you read the next few paragraphs, consult Table 9.3 for a visual plan of your rhetorical analysis. Your first body paragraph is the first of the analytical paragraphs. Here, too, you have options for organizing. You might begin by stating the writer’s strongest point. For example, you could emphasize that Peterson appeals to ethos by speaking personally to readers as fellow citizens and providing his credentials to establish credibility as someone trustworthy with their interests at heart.

Following this point, your next one can focus, for instance, on Peterson’s view that cutting foreign language instruction is a danger to the education of Greendale’s children. The points that follow support this argument, and you can track his rhetoric as he does so.

You may then use the second or third body paragraph, connected by a transition, to discuss Peterson’s appeal to logos. One possible transition might read, “To back up his assertion that omitting foreign languages is detrimental to education, Peterson provides examples and statistics.” Locate examples and quotes from the text as needed. You can discuss how, in citing these statistics, Peterson uses logos as a key rhetorical strategy.

In another paragraph, focus on other rhetorical elements, such as parallelism, repetition, and rhetorical questions. Moreover, be sure to indicate whether the writer acknowledges counterclaims and whether they are accepted or ultimately rejected.

The question of other factors at work in Greendale regarding finances, or similar factors in another setting, may be useful to mention here if they exist. As you continue, however, keep returning to your list of rhetorical strategies and explaining them. Even if some appear less important, they should be noted to show that you recognize how the writer is using language. You will likely have a minimum of four body paragraphs, but you may well have six or seven or even more, depending on the work you are analyzing.

In your final body paragraph, you might discuss the argument that Peterson, for example, has made by appealing to readers’ emotions. His calls for solidarity at the end of the letter provide a possible solution to his concern that the foreign language curriculum “might vanish like a puff of smoke.”

Use Table 9.3 to organize your rhetorical analysis. Be sure that each paragraph has a topic sentence and that you use transitions to flow smoothly from one idea to the next.

As you conclude your essay, your own logic in discussing the writer’s argument will make it clear whether you have found their claims convincing. Your opinion, as framed in your conclusion, may restate your thesis statement in different words, or you may choose to reveal your thesis at this point. The real function of the conclusion is to confirm your evaluation and show that you understand the use of the language and the effectiveness of the argument.

In your analysis, note that objections could be raised because Peterson, for example, speaks only for himself. You may speculate about whether the next edition of the newspaper will feature an opposing opinion piece from someone who disagrees. However, it is not necessary to provide answers to questions you raise here. Your conclusion should summarize briefly how the writer has made, or failed to make, a forceful argument that may require further debate.

For more guidance on writing a rhetorical analysis, visit the Illinois Writers Workshop website or watch this tutorial .

Peer Review: Guidelines toward Revision and the “Golden Rule”

Now that you have a working draft, your next step is to engage in peer review, an important part of the writing process. Often, others can identify things you have missed or can ask you to clarify statements that may be clear to you but not to others. For your peer review, follow these steps and make use of Table 9.4 .

- Quickly skim through your peer’s rhetorical analysis draft once, and then ask yourself, What is the main point or argument of my peer’s work?

- Highlight, underline, or otherwise make note of statements or instances in the paper where you think your peer has made their main point.

- Look at the draft again, this time reading it closely.

- Ask yourself the following questions, and comment on the peer review sheet as shown.

The Golden Rule

An important part of the peer review process is to keep in mind the familiar wisdom of the “Golden Rule”: treat others as you would have them treat you. This foundational approach to human relations extends to commenting on others’ work. Like your peers, you are in the same situation of needing opinion and guidance. Whatever you have written will seem satisfactory or better to you because you have written it and know what you mean to say.

However, your peers have the advantage of distance from the work you have written and can see it through their own eyes. Likewise, if you approach your peer’s work fairly and free of personal bias, you’re likely to be more constructive in finding parts of their writing that need revision. Most important, though, is to make suggestions tactfully and considerately, in the spirit of helping, not degrading someone’s work. You and your peers may be reluctant to share your work, but if everyone approaches the review process with these ideas in mind, everyone will benefit from the opportunity to provide and act on sincerely offered suggestions.

Revising: Staying Open to Feedback and Working with It

Once the peer review process is complete, your next step is to revise the first draft by incorporating suggestions and making changes on your own. Consider some of these potential issues when incorporating peers’ revisions and rethinking your own work.

- Too much summarizing rather than analyzing

- Too much informal language or an unintentional mix of casual and formal language

- Too few, too many, or inappropriate transitions

- Illogical or unclear sequence of information

- Insufficient evidence to support main ideas effectively

- Too many generalities rather than specific facts, maybe from trying to do too much in too little time

In any case, revising a draft is a necessary step to produce a final work. Rarely will even a professional writer arrive at the best point in a single draft. In other words, it’s seldom a problem if your first draft needs refocusing. However, it may become a problem if you don’t address it. The best way to shape a wandering piece of writing is to return to it, reread it, slow it down, take it apart, and build it back up again. Approach first-draft writing for what it is: a warm-up or rehearsal for a final performance.

Suggestions for Revising

When revising, be sure your thesis statement is clear and fulfills your purpose. Verify that you have abundant supporting evidence and that details are consistently on topic and relevant to your position. Just before arriving at the conclusion, be sure you have prepared a logical ending. The concluding statement should be strong and should not present any new points. Rather, it should grow out of what has already been said and return, in some degree, to the thesis statement. In the example of Octavio Peterson, his purpose was to persuade readers that teaching foreign languages in schools in Greendale should continue; therefore, the conclusion can confirm that Peterson achieved, did not achieve, or partially achieved his aim.

When revising, make sure the larger elements of the piece are as you want them to be before you revise individual sentences and make smaller changes. If you make small changes first, they might not fit well with the big picture later on.

One approach to big-picture revising is to check the organization as you move from paragraph to paragraph. You can list each paragraph and check that its content relates to the purpose and thesis statement. Each paragraph should have one main point and be self-contained in showing how the rhetorical devices used in the text strengthen (or fail to strengthen) the argument and the writer’s ability to persuade. Be sure your paragraphs flow logically from one to the other without distracting gaps or inconsistencies.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Authors: Michelle Bachelor Robinson, Maria Jerskey, featuring Toby Fulwiler

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Writing Guide with Handbook

- Publication date: Dec 21, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/9-5-writing-process-thinking-critically-about-rhetoric

© Dec 19, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How to Write a Rhetorical Analysis Essay

3-minute read

- 22nd August 2023

A rhetorical analysis essay is a type of academic writing that analyzes how authors use language, persuasion techniques , and other rhetorical strategies to communicate with their audience. In this post, we’ll review how to write a rhetorical analysis essay, including:

- Understanding the assignment guidelines

- Introducing your essay topic

- Examining the rhetorical strategies

- Summarizing your main points

Keep reading for a step-by-step guide to rhetorical analysis.

What Is a Rhetorical Strategy?

A rhetorical strategy is a deliberate approach or technique a writer uses to convey a message and/or persuade the audience. A rhetorical strategy typically involves using language, sentence structure, and tone/style to influence the audience to think a certain way or understand a specific point of view. Rhetorical strategies are especially common in advertisements, speeches, and political writing, but you can also find them in many other types of literature.

1. Understanding the Assignment Guidelines

Before you begin your rhetorical analysis essay, make sure you understand the assignment and guidelines. Typically, when writing a rhetorical analysis, you should approach the text objectively, focusing on the techniques the author uses rather than expressing your own opinions about the topic or summarizing the content. Thus, it’s essential to discuss the rhetorical methods used and then back up your analysis with evidence and quotations from the text.

2. Introducing Your Essay Topic

Introduce your essay by providing some context about the text you’re analyzing. Give a brief overview of the author, intended audience, and purpose of the writing. You should also clearly state your thesis , which is your main point or argument about how and why the author uses rhetorical strategies. Try to avoid going into detail on any points or diving into specific examples – the introduction should be concise, and you’ll be providing a much more in-depth analysis later in the text.

3. Examining the Rhetorical Strategies

In the body paragraphs, analyze the rhetorical strategies the author uses. Here are some common rhetorical strategies to include in your discussion:

● Ethos : Establishing trust between the writer and the audience by appealing to credibility and ethics

● Pathos : Appealing to the audience’s emotions and values

● Logos : Employing logic, reason, and evidence to appeal to the reader

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

● Diction : Deliberately choosing specific language and vocabulary

● Syntax : Structuring and arranging sentences in certain ways