Scoring Creativity: Decoding the Rubric for Creative Writing

My name is Debbie, and I am passionate about developing a love for the written word and planting a seed that will grow into a powerful voice that can inspire many.

Picture this: a blank page, waiting eagerly for you to fill it with words, with ideas, with a world of your very own creation. Whether you’re a seasoned wordsmith or just beginning to dip your toes into the vast ocean of creative writing, there’s no denying the thrill and challenge that comes with transforming a nebulous concept into a tangible piece of art. But how do we measure this artistry? How can we capture the essence of creativity and quantify it in a way that not only recognizes talent but also provides valuable feedback for improvement? Enter the rubric for creative writing – a powerful tool that unlocks the secrets to scoring creativity. In this article, we will embark on a journey to decode this mysterious rubric, demystifying its components and shedding light on how it can elevate your writing to new heights. So, grab your favorite pen and get ready to uncover the hidden treasures within the intricate world of scoring creativity.

Key Elements of a Rubric for Creative Writing

Understanding the purpose and structure of the rubric, evaluating creativity and originality, exploring language use and style, assessing organization and structure, analyzing grammar and mechanics in creative writing, providing constructive feedback to foster growth and improvement, frequently asked questions, to conclude.

When assessing creative writing assignments, it is important to have a rubric that emphasizes the unique aspects of this genre. A well-structured rubric not only helps evaluate students’ work objectively but also provides clear guidelines for improvement. Here are the key elements to consider when creating an effective rubric for creative writing:

- Originality: Successful creative writing demonstrates a unique and imaginative approach. A rubric should prioritize originality, encouraging students to think outside the box and avoid clichés or common themes.

- Engagement: A captivating story or piece of creative writing should engage the reader from beginning to end. Assessing how well a piece holds the reader’s interest, creates emotional connections, or sparks curiosity is crucial in evaluating a student’s work.

- Structure and Organization: Despite its imaginative nature, creative writing should still exhibit a well-structured and organized composition. A rubric should consider the coherence of ideas, logical progression, and the use of literary devices to enhance the overall structure.

Moreover, a rubric for creative writing should not only focus on the final product but also evaluate the writing process. By considering these key elements, educators can provide meaningful feedback and empower students to develop their creativity and refine their writing skills. Remember that a well-crafted rubric not only provides a clear assessment framework but also encourages students to unleash their creativity and storytelling abilities, fostering growth and improvement.

The rubric is a valuable tool that helps teachers assess student work based on specific criteria. It provides a clear outline of expectations, allowing both teachers and students to understand the purpose and structure of the assessment. By breaking down the assignment into different categories and levels of achievement, the rubric ensures fairness and consistency in evaluating student performance.

The structure of a rubric typically includes criteria, descriptors, and levels of achievement. The criteria outline the specific skills, knowledge, or qualities that students are expected to demonstrate in their work. Descriptors provide detailed explanations or examples of what each level represents, helping students understand what is required to achieve a certain grade. These levels of achievement can be presented in different ways, such as a numerical scale, a letter grade, or even descriptive phrases.

- A rubric allows teachers to provide constructive feedback in a clear and organized manner. Students can easily identify areas where they excel and areas that need improvement, enabling them to focus on specific skills and make progress.

- By , students can effectively plan and organize their work. They can align their efforts with the criteria outlined in the rubric, ensuring that they address all the required components and meet the expectations set by the teacher.

- Rubrics promote transparency in assessment as the criteria and expectations are clearly communicated to both teachers and students. This transparency fosters trust and facilitates meaningful discussions about student performance and progress.

Overall, the rubric serves as a valuable tool for guiding and evaluating student work. Understanding its purpose and structure enhances communication, supports effective teaching, and empowers students to take ownership of their learning.

When it comes to , it’s essential to approach the process with an open mind and a willingness to explore new perspectives. In today’s fast-paced world , where innovation is key, acknowledging and celebrating these qualities can lead to breakthrough ideas and solutions in various fields. So, how can we effectively assess creativity and originality? Let’s dive in:

- Embrace diverse thinking: Creativity is not limited to a specific domain or a particular way of thinking. Encouraging diverse perspectives and welcoming ideas from various backgrounds fosters a rich and fertile ground for innovative thinking. By giving space for unconventional thoughts and perspectives, we can unearth hidden gems of creativity.

- Value experimentation: Creativity often thrives through experimentation. Encouraging individuals to try new approaches, take calculated risks, and test unconventional ideas can yield unexpected and groundbreaking results. Acknowledging the value of experimentation creates an environment that supports and nurtures creativity and originality.

- Promote a learning mindset: Creativity flourishes when individuals have a growth mindset and embrace continuous learning. Providing opportunities for personal and professional development, promoting curiosity, and supporting ongoing education empowers individuals to expand their horizons and think creatively in their respective fields.

Creativity and originality are invaluable assets in our ever-evolving world. By adopting an inclusive and open-minded approach, embracing experimentation, and promoting a culture of ongoing learning, we can create an environment that nurtures and celebrates innovative thinking. Let’s remember, true creativity knows no boundaries!

Language use and style are essential aspects of effective communication. They play a vital role in conveying meaning, eliciting emotions, and engaging the audience. By exploring different language use and styles, we can enhance our writing, speaking, and overall communication skills.

One fascinating aspect of language use is the choice of words and phrases. The words we select can shape the tone and mood of our message. For instance, using vibrant and descriptive language can paint a vivid picture in the reader’s mind, while using technical jargon may be more suitable for specialized audiences. It’s important to consider the impact of our word choices to ensure clarity and precision.

- Metaphors and Similes: These literary devices can add depth and creativity to our language use. They help us explain complex concepts by drawing comparisons to more familiar objects or actions.

- Analogies: Analogies are useful for making abstract ideas more tangible and relatable. By likening a new concept to something familiar, we help our audience better grasp the subject matter.

- Rhetorical Devices: Rhetorical devices, such as alliteration, repetition, and parallelism, add rhythm and emphasis to our writing. They can make our message more memorable and persuasive.

Additionally, understanding different writing and speaking styles allows us to adapt our communication to different contexts and audiences. From formal and academic writing to casual and conversational tones, each style serves its purpose. Adapting our style based on the audience’s expectations can build rapport and improve their overall experience with our message.

By continually , we can cultivate our communication skills and become more effective storytellers. Experimenting with different techniques and styles helps us discover our unique voice and develop a versatile approach to communication.

When evaluating an organization’s effectiveness, one key aspect to consider is its organization and structure. A well-organized and efficiently structured organization can greatly contribute to its overall success and productivity. Here are some factors to assess when evaluating an organization’s organization and structure:

- Clarity of Roles: It is crucial for all team members to have a clear understanding of their roles and responsibilities within the organization. This ensures that tasks are properly allocated and promotes accountability.

- Communication Channels: A strong organization fosters effective communication channels, both vertically and horizontally. Transparent and open lines of communication facilitate the flow of information, enhance collaboration, and minimize misunderstandings.

- Efficiency of Workflow: A well-structured organization streamlines workflow processes, reducing unnecessary delays and optimizing efficiency. Assessing how tasks are assigned and how information flows within the organization can help identify areas for improvement.

Furthermore, a clear hierarchy within an organization ensures that individuals and teams know whom to report to and seek guidance from. Roles such as managers, supervisors, and team leaders establish an accountability structure that promotes effective decision-making and problem-solving. Additionally, an organization’s structure should allow for flexibility and adaptability to meet changing business needs and respond to unforeseen challenges.

Understanding and perfecting grammar and mechanics in creative writing can greatly enhance the overall quality of your work. While creative writing is often seen as free-flowing and expressive, paying attention to the technical aspects can make a huge difference in how your message is conveyed.

To start analyzing grammar and mechanics in your creative writing, consider the following tips:

- Grammar Mastery: Develop a strong foundation in grammar rules, including verb tense, subject-verb agreement , and punctuation. This ensures that your writing flows smoothly and is easily understood by your readers.

- Consistent Voice: Maintain a consistent narrative voice throughout your piece. Whether it’s first-person, third-person limited, or omniscient, clarity in voicing will prevent confusion and keep your readers engaged.

Furthermore, it’s important to recognize the power of effective mechanics in creative writing. Here are some key aspects to consider:

- Punctuation and Sentence Structure: Experiment with different sentence lengths and punctuation marks to create a rhythmic flow in your writing. This can add variety and help maintain the reader’s interest.

- Word Choice: Be conscious of the words you use and their impact on the overall tone and mood of your writing. Employing descriptive and vibrant vocabulary can bring your story to life and captivate your audience.

By paying attention to grammar and mechanics in creative writing, you can effectively convey your message while showcasing your artistry and maintaining the reader’s attention. Embrace these techniques and watch your writing soar to new heights!

Constructive feedback plays a critical role in helping individuals and teams reach their full potential. However, giving feedback in a manner that encourages growth and improvement can be challenging. By following a few key principles, you can provide feedback that is both effective and supportive.

- Focus on specific behaviors: When offering feedback, it is important to pinpoint the specific behaviors or actions that need improvement. By being specific, you can help the recipient understand exactly what they can do differently.

- Use the sandwich technique: One way to make feedback more constructive is to employ the sandwich technique. Begin with positive reinforcement, then offer areas for improvement, and finally end on a positive note. This approach helps maintain a healthy balance and ensures that the feedback is not overly critical.

- Be objective and avoid personal attacks: Feedback should always be objective and focused on the task or behavior at hand. Avoid making it personal or attacking the individual’s character. By staying objective, you can keep the conversation focused on growth and improvement.

Moreover, when providing feedback, it is essential to be empathetic and understanding. Put yourself in the recipient’s shoes and try to see things from their perspective. This will help you deliver feedback with empathy, making it easier for the recipient to accept and act upon.

Q: What is creative writing?

A: Creative writing is a form of artistic expression that involves crafting original stories, poems, plays, and other literary works. It allows writers to explore their imagination and unique perspectives through compelling narratives or evocative language.

Q: Why is creative writing important and worth assessing?

A: Creative writing enhances critical thinking, communication skills, and imagination. Assessing creative writing helps recognize and develop the writer’s ability to effectively express ideas, emotions, and experiences. It also promotes individuality, literary analysis, and cultural exchange.

Q: What is a rubric for creative writing?

A: A rubric for creative writing is a scoring tool used to assess and evaluate written works based on specific criteria. It outlines the expectations and benchmarks for various aspects of the writing, such as plot development, characterization, language use, and overall impact. A rubric provides a standardized and transparent evaluation process.

Q: What are the main components of a rubric for creative writing?

A: The components may vary depending on the purpose and level of assessment, but common elements include plot and structure, character development, language and style, creativity, originality, and overall impact. Each component is further divided into specific criteria and assigned different levels of proficiency, usually represented by descriptive statements and corresponding scores.

Q: How does a rubric help both teachers and students in evaluating creative writing?

A: Rubrics provide clear expectations and guidelines for both teachers and students. For teachers, it offers a systematic and consistent method of evaluation, reducing potential bias. Students benefit from the rubric by understanding the grading criteria in advance, which enables them to focus on specific areas of improvement and self-assessment. It promotes a fair and transparent assessment process.

Q: How can a rubric be used to provide constructive feedback?

A: A rubric allows teachers to provide specific feedback based on established criteria, highlighting both strengths and areas for improvement. By referring to the rubric, teachers can offer targeted suggestions to enhance plot development, character portrayal, language use, or creativity in the student’s writing. This feedback helps students understand their progress and areas where they need more practice, leading to growth as writers.

Q: Can a rubric be adjusted or personalized for specific writing assignments or student needs?

A: Yes, rubrics can be modified based on the specific assignment requirements, classroom objectives, or individual student needs. Teachers may adapt the rubric to address unique elements or emphasize particular writing skills relevant to the assignment or curriculum. Personalization enables a more tailored, meaningful assessment and supports the diverse needs and strengths of students.

Q: How can students use rubrics to improve their creative writing skills?

A: Students can refer to the rubric before, during, and after writing to ensure their work meets specific criteria and expectations. By analyzing the rubric, they can identify areas that need improvement and focus their efforts accordingly. Frequent self-assessment using the rubric can ultimately help students achieve a higher level of proficiency in creative writing and guide their growth as competent writers.

Q: Are rubrics the only way to evaluate creative writing?

A: While rubrics provide a structured and objective evaluation method, they are not the only way to assess creative writing. Other assessment tools, such as teacher feedback, conferences, peer reviews, and portfolio assessments, can also complement rubrics and provide a more holistic evaluation of a student’s writing skills. It is crucial to employ multiple evaluation methods to obtain a comprehensive view of a writer’s abilities.

In conclusion, understanding the rubric for creative writing can help writers enhance their skills and meet the criteria for scoring creativity.

Escaping the Rut: How to Get Away From Writer’s Block

Mastering Creativity: Writers Block: How to Overcome

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Reach out to us for sponsorship opportunities.

Welcome to Creative Writing Prompts

At Creative Writing Prompts, we believe in the power of words to shape worlds. Our platform is a sanctuary for aspiring writers, seasoned wordsmiths, and everyone. Here, storytelling finds its home, and your creative journey begins its captivating voyage.

© 2024 Creativewriting-prompts.com

Writing skills - creative and narrative writing

Part of English Writing skills

Imaginative or creative writing absorbs readers in an entertaining way. To succeed with this kind of writing you will need to write in a way that is individual, original and compelling to read.

Responding to Prompts

Imagine you’re in an exam and you are asked to write a creative piece called ‘The Party’. What does this title make you think of?Before you decide what you’d write, it’s useful to remember that you do whatever you want with the prompt as long as it’s somehow connected to a party.

- It doesn’t have to be something that really happened

- It doesn’t have to be based on exactly what the title says or is

- It can be as abstract or as mundane as you want it to be.

So this means that for the title ‘The Party’, you could write a lovely descriptive piece about your dream birthday party, or a personal account of a party you attended that was very good – or very bad. You could write a story about a political party, or a doll’s tea party, or a party held by fans to watch the final episode of a TV show everyone is very excited about, or a party that didn’t actually happen because no one turned up. The most important thing is that you choose a story you can write well, showing off your skill in using language effectively and keeping your reader entertained.

Original ideas

There is no formula for having a great idea – but to begin your writing, you do need, at least, some kind of idea. Then you need to find ways to turn your idea into something a reader would enjoy reading. This is the creative part, taking something ordinary and turning it into something extraordinary.

For example, think about writing a description of a coastline. You might start to think straight away about a crowded beach - children playing, deck chairs, sun shining, happy sounds; but, if you stop for a moment, you’ll recall that that's been done before. It's okay, but it's hardly original.

The 'plot hook' in this example is 'What could possibly go wrong?'.

Establish the time and place, as well as the general situation. This can also be used to help develop a suitable mood or atmosphere. It can sometimes help to use a familiar place that your reader can relate to in some way. At this stage, you need to 'set up' the story and begin to introduce the main character(s).

Fiction trigger (or inciting incident)

Use your narrator to tell of an incident or event that the reader feels will spark a chain of events. This helps make the reader feel that the story has really started. From this point, life cannot be quite the same for your main character (that is your protagonist). There is a problem that has to be faced and overcome.

The fiction trigger can be an event that really starts the story. It will develop from the 'plot hook'. If the story is about a day out at the zoo, then maybe an animal has escaped. If it is about a robbery, it might be the event that makes a character consider carrying out a robbery; and if it is about an accident, it will be the event that causes it to happen.

Keeping up the momentum (plot development or rising action)This section builds the tension – keeps the reader absorbed and guessing where it will all lead.

This is where you will move the story forward and will use lots of techniques to keep the reader guessing, 'What will happen next?!'

The problem reaches a head, with suspense creating lots of tension for the reader– showing the reader the possible result of what has come before.

This is not the end of your story – not quite. It will be the key event but your protagonist will, somehow, overcome it and all will be well.

Conclusion (the resolution)

This must leave your reader with a sense of satisfaction, or it could be a twist in the tale leaving questions that linger in the mind.

This is the ending of your story – where all loose ends are tied up to the satisfaction of the reader. A good story will cause the reader to go, 'Hmm – I liked that' or even 'Wow'

By following this story structure, and planning under each of the above headings, you should be able to come up with a tense plot for your own story, one that will engage and absorb your reader.

Writing techniques

Throughout your own story, you will also need to use writing techniques that will work to keep your reader engaged and absorbed. An important skill is to put clear images of the setting and characters in your reader’s mind, as well as to create a sense of atmosphere that suits each part of the story.

- Narration - the voice that tells the story, either first person (I/me) or third person (he/him/she/her). This needs to have the effect of interesting your reader in the story with a warm and inviting but authoritative voice.

- Description - describing words such as adjectives close adjective A word which describes a noun or pronoun. , adverbs close adverb An adverb gives more information about the verb, an adjective or another adverb. , similes close simile A literary technique where a comparison is made between two things using ‘as’ or ‘like’. and metaphors close metaphor Makes a direct comparison by presenting one thing as if it were something else with the characteristic. For example describing a brave person as a lion. that add detail. This is told by the narrator. It helps engage readers by creating vivid pictures and feelings in their 'mind’s eye'.

- Dialogue - the direct speech of characters, shown inside quotation marks. We all judge characters by what they talk about and by the way they speak. This makes dialogue a key technique for creating interest and realism.

- Alliteration - repetition of the same beginning sounds in nearby words.This can create a useful emphasis, maybe to highlight a sound or movement, or to intensify feeling or even to bind words together.

- Connotation - a word’s meaning can be literal, as in 'It looked like a cat', or it can create connotations as in 'As soon as the food reached the table, the boy pounced on it like a cat.' A connotation is a meaning created by a special use of a word in a particular way or context. It works by adding some kind of emotion or a feeling to a word’s usual meaning. All literature depends upon using language that creates connotations. They engage the reader because they evoke reactions and feelings.

- Pathetic fallacy - personification is a kind of metaphor and when nature is described in this way, it is called a use of pathetic fallacy. This can help suggest a suitable atmosphere or imply what the mood of the characters is at a certain point, eg in a ghost story, the storm clouds could be said to 'glower down angrily upon the group of youngsters'. A pathetic fallacy can add atmosphere to a scene. It can even give clues to the reader as to what is to come, acting as a kind of foreshadowing close foreshadow Hint at something that will happen later and have greater significance .

- Personification - this is a technique of presenting objects as if they have feelings, eg 'the rain seemed to be dancing merrily on the excited tin roof.' This creates a sense of emotion and mood for the reader.

- Repetition - the action of repeating a word or idea. This can add emphasis or create an interesting pattern of sound or ideas.

- Onomatopoeia - use of words which echo their meaning in sound, for example, 'whoosh' 'bang'. Using this can add emotion or feeling that helps give the reader a vivid sense of the effect being described.

- Simile - a kind of description. A simile compares two things so that the thing described is understood more vividly, eg 'The water was as smooth as glass.' (Hint - 'like' or 'as' are key words to spot as these create the simile). A simile can create a vivid image in the reader’s mind, helping to engage and absorb them.

- Symbolism - we grow up learning lots of symbols and these can be used in stories to convey a lot of meaning as well as feeling in a single idea or word, eg a red rose can symbolise romantic love; a heavy buckled belt can hint at the power held by the character; an apple can even symbolize temptation if it is used in a way that the reader links to the apple that tempted Eve in the biblical Garden of Eden.

- Impact - symbols help writers pack a lot of meaning into just a single word. They work to engage the reader, too, for the reader automatically gets involved in working out the meaning.

Examples of narration

First person narrator.

I held on to the tuft of grass and slowly looked down - I was too shocked to speak. One moment I had been strolling along the cliff with Vicki, the next I was hanging over the edge. And where was Vicki?

The only thing you shouldn't do is swap the narrative point of view during the story - don’t start with 'I' and then switch to 'he', as it is likely to confuse your reader.

Third person narrator

Steve held on to the tuft of grass and slowly looked down - he was too shocked to speak. One moment he had been strolling along the cliff with Vicki, the next he was hanging over the edge. And where was Vicki?

Ending a short story

The ending of a story doesn't necessarily have to be happy but it has to make sense in a way that ties up what has happened.

There are different types of story endings, for example:

- The cliff-hanger - this isn’t an ending as such, it’s a way of tempting the reader to read the next chapter or instalment. Charles Dickens wrote his chapters like this as they were originally published in magazines in serial form. For example, does the spy manage to stop the bomb in time?

- The twist-in-the-tale - the reader will feel fairly sure about the ending, but in the final part everything changes and we are surprised. For example, we learn that it isn’t a bomb after all, it’s a birthday present!

- The enigma ending - the story stops, but the reader is left a little unsure what will come to happen, yet is intrigued by the possibilities - and still feels satisfied. For example, the bomb is defused and everyone is safe, but then an army commander reports the theft of another bomb… only this time twice as powerful.

There are many possibilities; but there are two endings you should try to avoid:

- The trick ending - a bomb will inevitably explode and as it does, the narrator wakes up - it was all a dream. This is too clichéd and unsatisfying for modern readers.

- The disconnected ending - the secret agent suddenly stops worrying about the bomb, retires, and goes off to play golf. Readers don't like this because the ending has nothing to do with the story – very unsatisfying.

Whatever kind of story you write, work out a satisfying ending and include it in your plan.

Writing that is creative and imaginative needs to be entertaining. You need to experiment a little and not be frightened to try something new.

What might you write about if the following tasks came up in an exam? Take a few minutes to think about different ways you could interpret the task, and maybe sketch a quick plan for your best idea.

- The Best Day of My Life

- The Mysterious Door

- Never Again

- Stormy Weather

- How to be a Hero

- Sunday at the Beach

- My Life as an Expert

- Greetings from the Future

- What I REALLY Learned at School

More on Writing skills

Find out more by working through a topic

How to write an essay

- count 5 of 7

How to write a conclusion to an essay

- count 6 of 7

Writing skills

- count 7 of 7

Writing skills - tone & style

- count 1 of 7

Writer's Bounty

Providing Support for Writers and Teachers of Writing

Cheat Sheet for Grading Creative Writing

A cheat sheet for grading creative writing can be a useful tool for teachers and instructors who are looking for a quick and easy way to assess the quality of their students’ writing. By providing a set of guidelines and criteria to follow, a cheat sheet can help instructors quickly and consistently evaluate the creativity, organization, and overall effectiveness of a piece of writing. This then allows them to provide constructive feedback and support to their students as they work to improve their skills.

Why is Grading Creative Writing so Difficult?

Grading creative writing can be challenging for instructors. It’s often very personal and subjective, which makes it hard to assess using traditional grading systems. Plus, creative writing can be complex. It can involve a lot of emotions, which can be difficult to capture in writing. Additionally, the field is constantly changing, making it hard for instructors to stay on top of new styles and techniques. Overall, grading creative writing requires a careful and sensitive approach.

Cheat Sheet for Grading

Here are six quick and easy tips to keep in mind when grading your students’ creative writing.

Tip 1: Focus on the Overall Structure and Organization

- Does it have a clear beginning, middle, and end?

- Does the plot flow smoothly from one event to the next?

- Does it pull you along, or do you lose track of what’s happening?

Tip 2: Pay Attention to the Characters.

- Are they well-developed and believable?

- Do they have distinct personalities and motivations?

- Does the protagonist have any flaws or are they perfect?

- Does the antagonist have any redeeming qualities?

Tip 3: Look for Strong Descriptions and Sensory Details.

- Does the writer use vivid language to bring the scene to life?

- Does the writer use more senses in descriptions than just sight?

- Do the setting descriptions help set up a mood for the writing?

Tip 4: Consider the Use of Dialogue.

- Does it sound natural and add to the story?

- Does it give insight into the personality traits of the characters?

- Is it written correctly, following punctuation and paragraphing norms?

Tip 5: Evaluate the Writer’s Style and Voice.

- Does the writing have a unique and engaging tone?

- Could you tell which student wrote the piece just by reading it?

Tip 6: Look for Creativity and Originality

- Does the writer have fresh ideas?

- Is there anything unique about this writing from that of other students?

Final Thoughts and Freebie

Overall, the key is to provide constructive feedback that will help the writer improve and grow. It’s important to remember that creative writing is a form of self-expression, and everyone has their own unique voice and style. As a grader, your job is to help the writer hone their craft and develop their skills.

If you have any advice for grading creative writing, please put it in the comments below. Also, here is a free checklist to help you have a grade for each student’s creative work. It’s available in both an editable PowerPoint and a quick print PDF.

Similar Posts

The Benefits of Journaling: Teaching Reflective Writing in Creative Writing Classes

The art of teaching reflective writing in creative writing classes is a skill that holds immense value. Journaling, a time-honored tradition, provides an invaluable tool that brings an entirely new perspective to the writing process. In this realm, journaling stands out as a powerful instrument, acting as a catalyst for bolstering creativity, enhancing self-awareness, and…

Mastering ESL Creative Writing in a Multilingual Classroom

Diving headfirst into teaching creative writing for ESL students can feel like navigating through uncharted waters. But guess what? You’re not alone. We’ve been there, and we’ve got the compass to guide you through. The Multilingual Classroom: Challenges and Opportunities Sure, teaching in a multilingual classroom comes with its fair share of challenges. There’s the…

Student Writers Unleashed: Character Interviews 101

Character interviews are an essential tool for teachers who strive to empower their student writers in creating authentic, relatable, and engaging characters. By introducing the concept of character interviews in the classroom, you enable students to delve deep into the psyche of their characters, understanding their motivations, desires, fears, and idiosyncrasies. With your guidance, your…

Top-Notch Tactics for Teaching Creative Writing

Hey there, creative writing teachers! We know you have a pretty amazing gig – you’re in charge of sparking those imaginative fires, guiding the next generation of poets, playwrights, and novelists. It’s a big job, no doubt. But, hey, we’ve got your back. In this article, we’re going to dive into the best techniques you’ll…

Unlocking the Power of Revision: 16 Tips for Teaching Revision

As a creative writing teacher, you know that teaching creative writing can be challenging and rewarding. Unfortunately, while seeing your students explore their imaginations and create new worlds on paper can be exciting, they often refuse to make revisions to improve their work. Here’s a step-by-step guide on how to teach secondary students to revise…

Smashing Writer’s Block: Student Edition

Ever noticed a student gazing at a blank page, stuck in a creative standstill? That pesky problem is none other than writer’s block. But fear not, it’s not an unbeatable monster. Together, we’re going to tackle it and transform your classroom into a hub of creativity by overcoming student writer’s block! Unraveling the Challenges of…

- Primary Hub

- Art & Design

- Design & Technology

- Health & Wellbeing

- Secondary Hub

- Citizenship

- Primary CPD

- Secondary CPD

- Book Awards

- All Products

- Primary Products

- Secondary Products

- School Trips

- Trip Directory

- Trips by Subject

- Trips by Type

- Trips by Region

- Submit a Trip Venue

Trending stories

Top results

- Success Criteria Strategies For Developing Writing Skills In The Classroom

Success criteria – strategies for developing writing skills in the classroom

Criteria for descriptive writing can be restrictive for pupils – but they can be easily expanded, says James Durran…

When approaching a piece of writing, pupils are often given ‘success criteria’ in the form of a list of features which the writing ‘requires’ in order to be successful.

However, colleagues and I have been working with primary schools to develop an alternative to listed success criteria for writing, which we call ‘boxed’ or ‘expanded success criteria’.

It is very easy to adopt, and teachers have been finding that it can transform how writing is discussed and approached in the classroom, with an immediate impact on the quality of what pupils are producing.

Current criteria are tied explicitly to particular curriculum and teaching ‘objectives’, and often include technicalities such as full stops and commas; may include features such as metaphors, adjectives for description, varied sentence openers and so on; and they tend to include grammatical or cohesive devices , such as time adverbials, subordinate clauses or relative pronouns.

These ingredients can be useful, such as reminding pupils of things they might do to make the writing effective, reinforcing learning, providing a ready checklist for self and peer assessment, and so on. But teachers are increasingly aware of their potential drawbacks:

- They can promote a ‘writing-by-numbers’ approach, in which writing becomes a performance of features rather than a coherent whole.

- They can encourage teaching and task-setting by narrow text type, limiting the scope of what pupils might achieve.

- They are not really success criteria. The success of a piece of actual writing can only be measured by how well it communicates or achieves its purpose for its intended reader, not by whether it contains specified ingredients.

- Feedback – at the end or while drafting and editing – can therefore tend to focus just on whether specific elements are included, rather than on how effective the writing is as a complete piece.

Together, these interrelated factors can work against pupils’ development as real writers, writing for specific, authentic purpose and audiences .

Read the room

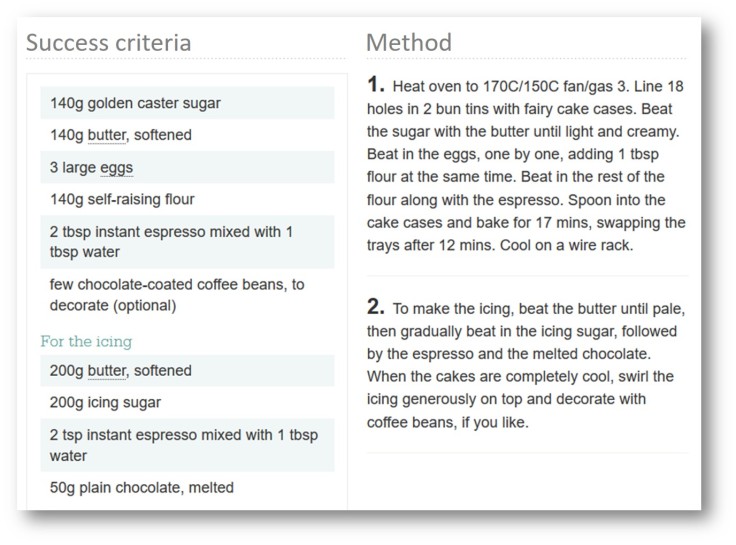

If pupils are writing a recipe, it is simple and easy to give them a list of components including, for example, ingredients and equipment; numbered steps; time and sequence adverbials; imperative or command verbs.

And these components are a useful starting point. But if you then ask children to compare the following two fragments, which each give the same instruction:

Add Worcester sauce for extra flavour. Slosh in some Worcester sauce to make it even yummier.

Suddenly there is much more to consider. Now, questions such as ‘Who is the recipe for?’ , ‘What do they want and need?’ , ‘How can we engage them?’ and ‘What sort of verbs, nouns and adjectives might we therefore use?’ come up.

Although this might sound like more work, it is much more interesting for pupils, and is certainly more fun to teach!

It is important to teach about genre and the features of different kinds of writing. But as teachers we know that when pupils move on from thinking just in terms of text type, their writing opens up, with much more potential for richness, variety and authenticity.

For example, an account of a trip – perhaps in the form of an article – is not just a ‘recount’. It can be engagingly descriptive, will have elements of entertaining narrative, is likely to involve explanation, and even elements of persuasion and argument.

Similarly, a brochure about a town should be much more than a ‘non-chronological report’. Depending on the intended audience, it will modulate between and blend elements of description, narrative, explanation, instruction and persuasion.

When considering how to help a pupil develop a story opening, it is easy to start listing technical or stylistic devices. For example:

Billy went into the house. He looked into the kitchen. He saw a big dog. The dog ran to him.

But the first question to ask this child is not ‘Could you use some…?’ or ‘Can you add in…?’ It is, simply, ‘What sort of story is this, and how do you want the reader to feel?’ . Then things move forward.

Boxed criteria in practice

Traditional ‘success criteria’ are really the wrong way round. They define ‘success’ in terms of the presence of ingredients, not in terms of the actual point of the writing.

Boxed criteria keep the ingredients, but link them explicitly to purpose and to the reader. It’s really that simple.

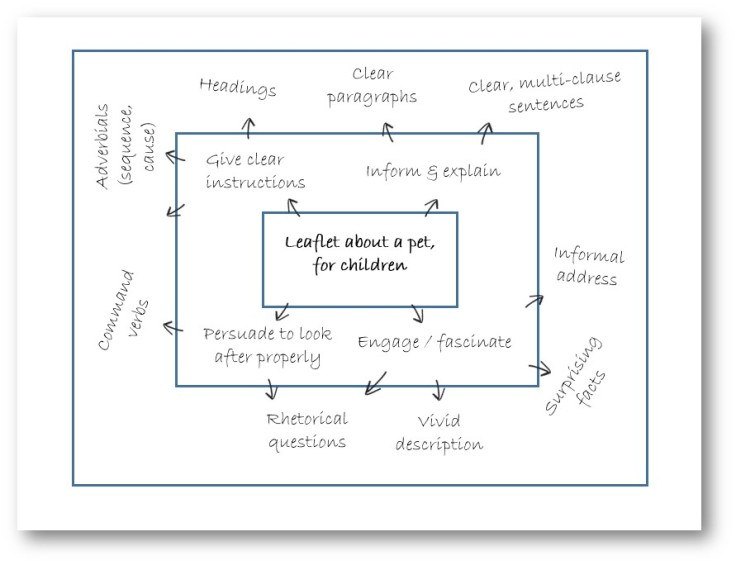

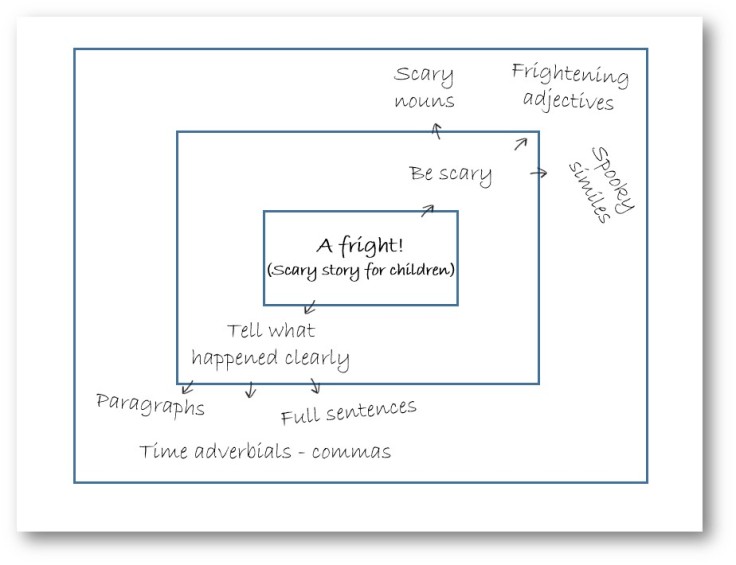

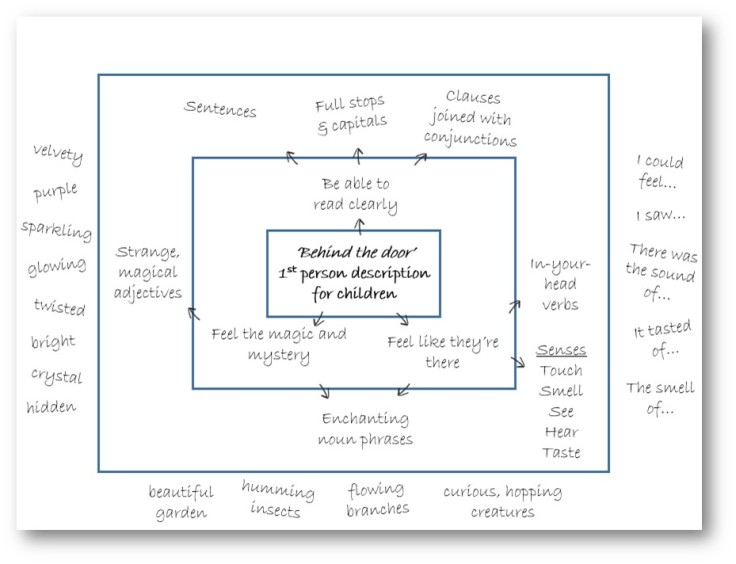

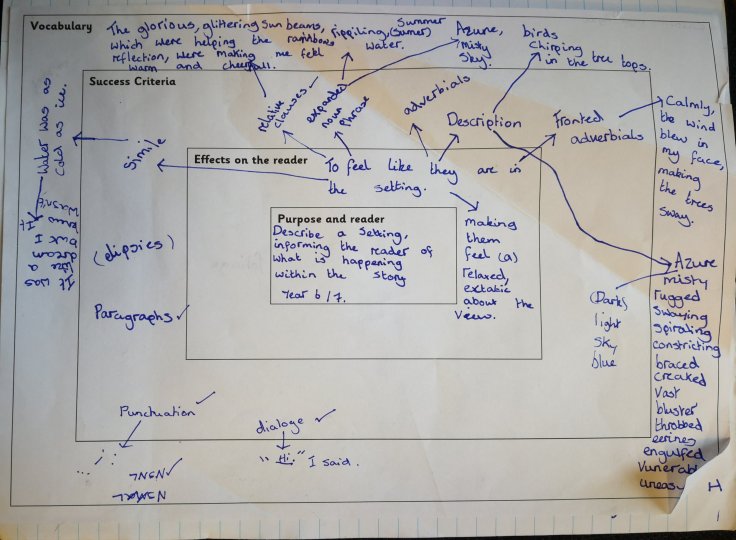

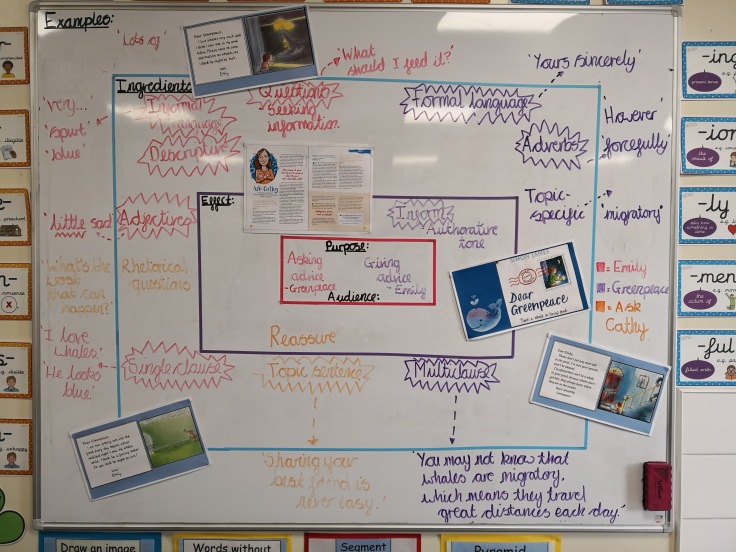

In the middle, pupils put what type of writing they’re doing and its intended audience; outwards from this are the intended ‘effects’ on that audience, or what the writing is meant to provide for its readers; outwards again are the ingredients – the features which might help to achieve these things.

Note that in this example the ingredients are themselves described in terms of their impact: ‘scary nouns’, ‘frightening adjectives’ and ‘spooky similes’. Grammatical forms should be used for a reason, not for their own sake.

You might create these boxes yourself and give them to the children. It is more likely, however, that the class will construct them together through discussion, and reading and picking apart examples.

Ultimately, there is nothing radical or intrinsically innovative about this method. It is just a visual device for focusing the thinking of teachers and pupils on what writing is actually about: communication and effect, not just the performance of skills.

Pupils might have their own grid in their books, which can be easily replicated through a simple template. (You can create this in a Word document and keep it handy for the children to stick into their books).

Or, you might decide to have a big class one on the wall. This can be drawn onto the whiteboard, or constructed as part of a classroom display.

A fun way to mix up the boxes is to print out examples of sentences in texts you like and stick them up on the board with an image.

Either way, it can be a dynamic, evolving thing, added to and adjusted as ideas are developed and shared through the planning, drafting and editing stages of writing.

This is a tool which can live with the piece of writing through its stages: from reading and exploring examples, to planning and assembling ideas, drafting and editing, proof-reading, all the way through to publication and reflection.

And of course, at every stage, the starting point for teacher, peer or self-assessment and feedback is not a list of ingredients, but whether the writing is achieving what it is meant to achieve.

Sign up to our newsletter

You'll also receive regular updates from Teachwire with free lesson plans, great new teaching ideas, offers and more. (You can unsubscribe at any time.)

Which sectors are you interested in?

Early Years

Thank you for signing up to our emails!

You might also be interested in...

Why join Teachwire?

Get what you need to become a better teacher with unlimited access to exclusive free classroom resources and expert CPD downloads.

Exclusive classroom resource downloads

Free worksheets and lesson plans

CPD downloads, written by experts

Resource packs to supercharge your planning

Special web-only magazine editions

Educational podcasts & resources

Access to free literacy webinars

Newsletters and offers

Create free account

By signing up you agree to our terms and conditions and privacy policy .

Already have an account? Log in here

Thanks, you're almost there

To help us show you teaching resources, downloads and more you’ll love, complete your profile below.

Welcome to Teachwire!

Set up your account.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipisicing elit. Commodi nulla quos inventore beatae tenetur.

I would like to receive regular updates from Teachwire with free lesson plans, great new teaching ideas, offers and more. (You can unsubscribe at any time.)

Log in to Teachwire

Not registered with Teachwire? Sign up for free

Reset Password

Remembered your password? Login here

How to Teach Writing with Success Criteria

Teaching children how to write and get their ideas onto paper can be challenging, but it is also very rewarding. There are a lot of fun ways to teach this essential skill. Using success criteria and clear examples help guide children as they learn.

Below is an activity that I use every year in my classroom with young children. It is always incredibly effective and I see the results of the learning immediately with my students. Also, they always love the activity and are engaged throughout!

I always talk to my students about all of the great things that they include in their writing.

However, as a teacher we also talk a lot about things that can be done to improve their work, the success criteria, and aiming for their best.

I truly believe that all kids want to do well, however, they often don’t know or fully understand what they need to do to improve their work and marks. This activity helps with this!

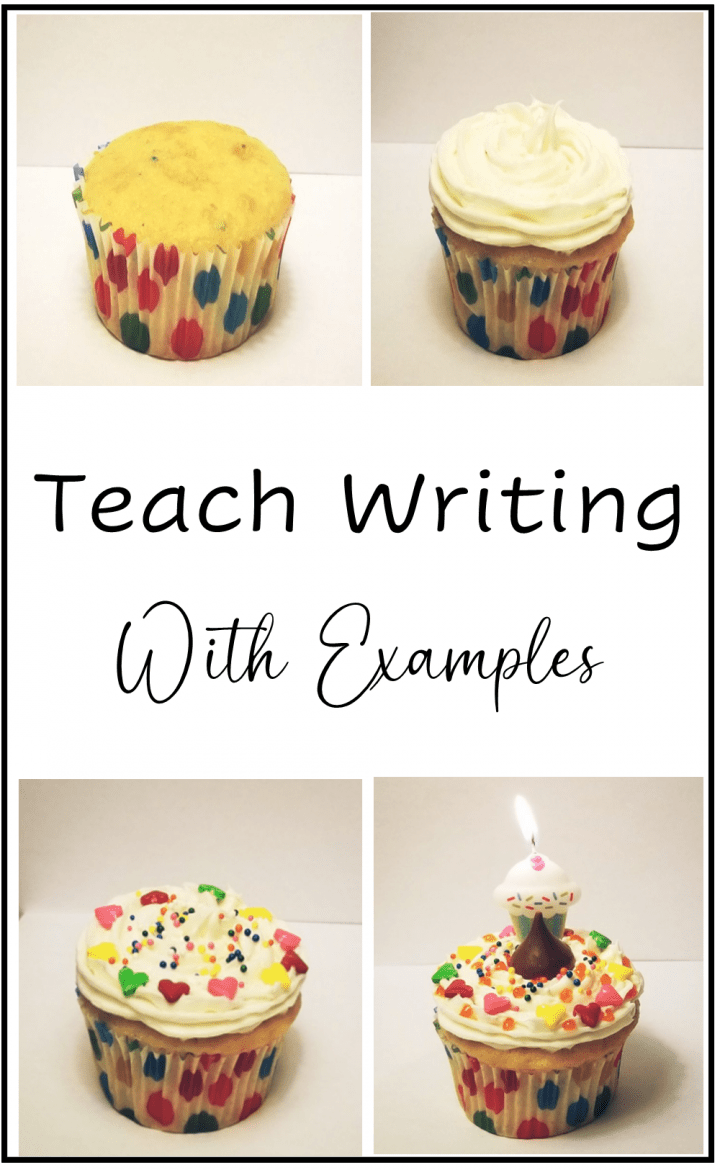

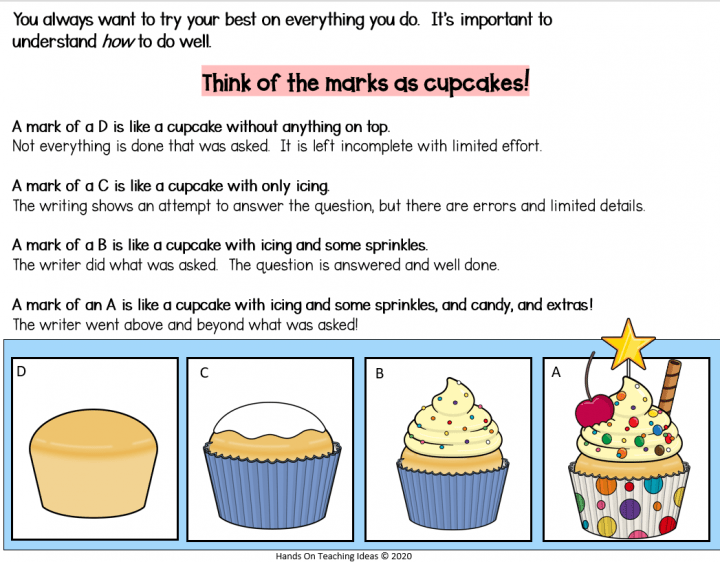

That’s where cupcakes come in!

Cupcakes may seem like an unusual thing to include in a writing activity, but I feel strongly that any time you can add a hands-on and engaging element to an activity then it will benefit all children.

As children begin writing and improving their spelling, try some Hands-on spelling activities to support this part of their writing.

Once you’ve tried the activity below to demonstrate to children some writing strategies, and understanding of ways to make their writing better, check out these Tips for a Child Who Hates Writing .

How to Write Success Criteria Materials

I created a set of leveled writing examples for children to read and tell what is well done in the writing and what can be improved upon. I have included a link to the examples at the bottom of this post. You can use these examples, or your own.

- Leveled Writing Examples (Level 1,2,3,4 – or A, B, C, D)

- Sprinkles and Other Decorations for the Cupcakes

For a lot of children, being able to see what a level 1 writing (or a mark of a D) looks like in comparison to a level 2 (a C mark) can be eye opening for them.

They may notice that it is small things, like adding a period to the end of their sentences that can bump them up a level.

We teach kids how to read and write and lots of other important skills, I also need to teach what a level 4 (or an A) looks like in order for children to strive for it.

Teaching Success Criteria with Cupcakes

Using cupcakes teaches writing in an engaging way that kids understand, and pay attention to.

Each marking level is represented by a cupcake.

Before showing each cupcake, I started by showing an example of each level of writing. We started with level 1 and then I showed my level 1 cupcake.

We talked about what was well done in the level 1 writing and what it lacked.

I then showed the plain cupcake. Nothing on it. No icing. No sprinkles. Nothing.

The level 1 cupcake is incomplete, just like the writing example. The plain cupcake is a visual representation of the writing.

As a class, we went though each grading level. For each level, I added something to our cupcake. We talked about how adding a capital to the beginning of each sentence improves their writing.

I added icing to the cupcake just like capitals were added to the writing.

The level 2 cupcake is a bit better than the level 1. It includes a bit more and looks a bit better, but there is still lots that we can do to improve it.

Our level 3 cupcake included some candy hearts and some sprinkles. The level 3 is an average piece of writing. It looks good and includes everything that was asked for the writing.

Children were pretty excited about our level 3 (a B grade) cupcake. They thought that it looked pretty appealing and certainly felt that it represented the level 3 writing.

The cupcake modeled that a level 3 piece of work is good. The work is complete and it included what was assigned. It looks good too!

Finally, we got to our level 4 cupcake. A level 4 is the equivalent mark of an A. This cupcake includes everything you could possibly want in a cupcake. It has everything that the level 3 cupcake had, but then even more was added.

There’s a huge chocolate, some orange gel icing and even a candle. (I didn’t light the candle in class and would avoid using fire in a classroom.) However, all of the extras on this cupcake certainly looked impressive.

This cupcake (and a level 4 piece of work) goes above and beyond just like the level 4 piece of writing.

The level 4 piece of writing has everything that was required for the assignment, but it also goes above and beyond. The spelling and technical parts, such as periods, are all included and done properly.

Another big part of the level 4 work is the extra details that are added to it. Often simply writing more and putting all of their thoughts down on paper improves their writing.

I represented this attention to detail by slowing adding the extra cupcake toppings. I carefully put the orange icing into the right spots to show that the details matter.

Teach Writing Success Criteria

Once we had gone through all of the levels, we weren’t done yet. I gave each child a cupcake and I posted our cupcake pictures in the classroom to remind students the differences between the levels.

After modeling the grade levels in this way, my students all completed amazing pieces of writing. They clearly understood the success criteria that I was looking for.

Although I used the cupcakes for a writing example, the idea can be used for any subject area and for any project.

In class, we constantly talked about our “Level 4 Cupcake” when completing work and children visualize our cupcakes and they remember how adding a few things can make a huge difference.

Success Criteria Leveled Writing Examples

The leveled writing examples that I used with my class are available below. They include an example for each level as well as explanations for the marking.

For your convenience, this post contains affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases and I may earn a small commission at no cost to you.

Tracing Paper Roll 18 Inch x 30 Yards White Trace Paper Translucent Pattern Paper for Drawing Sewing

BOHADIY Moon Diamond Painting Kits for Adults,Moon Beach Diamond Art Kits Full Drill Moon Landscape Paint with Diam…

JFYHAB DIY Cat Diamond Art Kits with Round Diamond, 5D Diamond Painting Kits for Adults, Cat Family Diamond Paintin…

Subscribe to hands-on teaching ideas.

Join the mailing list to be the first to learn about latest products, promotions and activity ideas. By subscribing you will also gain access to the Free Resource Library filled with resources you can download and use today!

More Hands-On Teaching Ideas

Looking for more hands-on activities for kids at home or school? Below is a collection of some of my favourite, and most popular learning activities to try out at home or school.

Leave a Reply Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

How to Create Leveled Success Criteria

Three years ago Ross School set off on a mission to ensure every student (or as we call them learners) developed their assessment capabilities. Put simply, the school wanted all learners to independently answer three fundamental questions:

- Where am I going in my learning?

- Where am I now in my learning?, and

- What’s next to improve my learning?

These questions went to the heart of what learners were thinking about during class. Often learners were found focusing on tasks to complete, such as the number of problems they needed to do. Other times, learners were focused on the context of the unit. For example, learners were thinking about sea otters when they were really suppose to be thinking about the movement of energy in a food chain.

We knew that if learners were not focused on the actual learning they would be unable to develop long term memories of the core ideas, and wouldn’t be able to apply those ideas in different situations. The first step for us as a team was to ensure learners were clear on teacher expectations.

Teacher Clarity

Teacher clarity may be best defined as a learner’s ability to know the outcomes of learning (ie learning intention) and the expectations (i.e. success criteria) for meeting the outcomes of learning.

Teacher clarity as an influence has been found to be linked to almost two years’ growth in one year’s time (Hattie, 2009). Teacher clarity is actually a misnomer in that it’s not really about how clear teachers are on outcomes for learning, but that students are clear. Moreover, clarity of outcomes is an essential ingredient to other variables that have a powerful influence on student learning including:

- Assessment capabilities

- Scaffolding

- Seeking help from peers, and

- Classroom discussion

Numerous books have been written on the importance of learning intentions and success criteria for learners (Clarke, 2014). Often these books show success criteria as one set list for students to meet.

The challenge with this approach is that it assumes students can inherently recognize the complexity of each success criterion independently. More often than not, students are unfamiliar with the material to be learned and are therefore unable to decipher the right sequence of success criteria to be met over time.

Leveled Success Criteria

At Ross School, we use a simple taxonomy that articulates complexity for students. The taxonomy, a modified version of Biggs and Collins’s SOLO taxonomy , is based on three levels of learning and articulates a student’s ability to understand, relate, and apply ideas or skills. The taxonomy may be best represented in the following way:

- Surface: I know one or more ideas/skills but am unable to relate or apply them .

- Deep: I can connect ideas/skills together but am unable to apply them.

- Transfer: I can apply ideas/skills in different situations.

To assist students in understanding complexity of learning and to support them in tracking their own learning needs and progress over time, articulating reference for expectations across surface, deep, and transfer has been immensely helpful for our learners.

Leveled Success Criteria Development Process

The process for designing leveled success criteria is a simple six-step process:

Step 1 : Craft learning intentions in student-friendly language

Take the outcomes of your syllabus and convert them into “I will” statements for learners. Ensure that the verb that is used after “I will” requires deep or transfer expectations (see the list below for potential verbs).

E.g. I will apply multiplication of fractions.

Step 2 : Craft leveled success criteria at surface, deep, and transfer learning.

Once you established your learning intention you will need to create success criteria to ensure students know what to know and be able to do to meet your expectations. When writing out your expectations, you want to use verbs at each level of learning (ie surface, deep, and transfer). The following table lists a series of verbs that may be helpful in this process.

Here is an example of success criteria in a 3rd grade math classroom:

Step 3 : Refine learning intentions by ensuring the verbs are aligned to deep or transfer and refine success criteria by removing tasks, activities, and contexts.

Once you have sketched your learning intentions and leveled success criteria it’s a good idea to review your work and ensure you have alignment of verbs and expectations at each level of the success criteria and that your learning intention is written at the highest level of learning you expect.

In addition, you will want to ensure that your success criteria doesn’t include assignments or products in the descriptors. Assignments, products, and activities are all ways in which students demonstrate their learning but more often that not they are not a learning intention nor success criteria. For example, if students are learning to write a balanced argument, then we want to include the criteria that is necessary in such an argument including forming an opinion in the closing, relating two opinions, backing up opinions by experts, and using high percentages. We would not want to include in the success criteria “write a paper”. The paper is a task in which students will demonstrate the success criteria. The success criteria is what we want them to focus on during class and when writing a paper.

Step 4 : Create a driving question that presents students a rationale for meeting transfer expectations

This may be viewed as an optional step but is actual critical in presenting the learning intention as important for learning. Driving questions positioning the learning intention as a question rather than a statement and often show students one or more contexts (or situations) in which they, the students, will engage in to meet the learning intention. Driving questions are usually presented to students at the beginning of a unit to drive the learning.

How do we apply multiplication of fractions [when converting units in chemistry to demonstrate the relationships between quantities]?

Step 5 : Receive feedback from peers to ensure alignment of learning intentions and success criteria.

Before building other parts of your unit (such as building tasks and activities for kids), ask colleagues to review your work and look for the following:

- Learning intentions: Does the learning intention require deep and transfer learning?

- Success criteria: Do the success criteria align to surface, deep, and transfer? Are the success criteria devoid of contexts and tasks?

- Driving Question: Does the driving question align to the learning intention? Does it require surface, deep, and transfer learning to answer?

Written by Michael McDowell, Ed.D.

Michael McDowell, Ed.D. is the Superintendent of the Ross School District. Most recently, he served as the Associate Superintendent of Instructional and Personnel Services at the Tamalpais Union High School District. During his tenure, the Tamalpais Union High School District was recognized by the Marzano Research Laboratories as one of the top highly reliable organizations in the United States, and schools within the district received recognitions by the US News and World Report, and honored with California Distinguished Schools accolades.

Prior to his role as a central office administrator, Dr. McDowell served as the Principal of North Tahoe High School, a California Distinguished School. Prior to administration, Dr. McDowell was a leadership and instructional coach for the New Tech Network supporting educators in designing, implementing, and enhancing innovative schools across the country. Before engaging in the nonprofit sector, Dr. McDowell created and implemented an environmental science and biology program at Napa New Technology High School, infusing 1:1 technology, innovative teaching and assessment, and leveraging student voice in the classroom. Additionally, Dr. McDowell, taught middle school math and science in Pacifica, CA. Dr.

McDowell is a national presenter, speaking on instruction, learning, leadership and innovation. He has provided professional development services to large school districts, State Departments of Education, and higher education. In addition, he was a former National Faculty member for the Buck Institute of Education and a key thought leader in the inception of their leadership work in scaling innovation in instructional methodologies. His expertise in design and implementation is complimented by his scholarly approach to leadership, learning, and instruction.

He holds a B.S. in Environmental Science and a M.A. in Curriculum and Instruction from the University of Redlands and an Ed.D. from the University of La Verne. He received departmental honors for his work in Environmental Science and was awarded the Tom Fine Creative Leadership Award for his doctoral work at the University of La Verne. He has also completed certification programs through Harvard University, the California Association of School Business Officials, the American Association of School Personnel Administrators, and Cognition Education. He holds both a California single subject teaching credential and an administrative credential.

Which VISIBLE LEARNING Book is Right for You?

The 7 steps to become an effective coach, no comments, leave a comment cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related posts

Even More Learning Made Visible

Visible Learning and Teaching Multilingual Learners: 5 Considerations

‘TRUE’ Visible Learning: Evidence of Impact

Making Learning Visible in Early Childhood Through Play

It’s Not Only HOW You Use a Strategy – Its...

Bridging the Implementation Gap: From Inklings to Ideas to (Godzilla-like)...

How to Write Success Criteria

A step-by-step guide to writing success criteria.

Writing success criteria can be a challenging task, especially for teachers who are new to the process. However, by following a few simple steps, you can create clear and effective success criteria that will help your students understand what is expected of them, and guide their learning.

1) Determine your Learning Intention

To write Success Criteria, you first need to know what learning will be taking place in your lesson/s. Your Learning Intention will outline what knowledge or skills you will be teaching your students to understand or demonstrate.

2) Identify prior learning needed for gaining that new knowledge or skills

What is the underpinning knowledge that students will need to be successful? Do they need to know their times up to 12x12 off by heart? Do they need to know the 3 main types of rocks? Do they need to know how to perform an overarm throw? We have to know our starting point before we can spring off onwards and upwards.

3) Identify the new knowledge students will learn (if applicable)

Make a list of new knowledge you’re teaching your students. If anything is quite similar, you might like to combine these into one Success Criteria statement. This list does NOT have to look pretty.

For converting between mixed numbers and improper fractions, your list might look like:

Mixed number = whole number & proper fraction

Improper fraction = numerator is greater than or equal to denominator

Can write whole number as fraction with denominator of 1

Times tables to 12x12 memorised

4) Make it actionable

Now, turn these into actions by adding ‘I can’ + one of these knowledge verbs: define, state, recall, name, recognise, list, label, count, write ... ( see more here ).

I can define a mixed number

I can recognise an improper fraction

I can record a whole number as a fraction with a denominator of 1

I can recall all times tables up to 12x12 instantly

BOOM! How simple was that?

5) Repeat the process

List the new skills/understandings/processes students will need to be able to demonstrate but this time, use the understanding/ application/ analysis/ evaluation/ creation verbs you can find here .

For our Maths scenario, we want students to be able to make a common denominator so they can add fractions together.

We want students to apply a skill so we use an application verb e.g. demonstrate, perform, select, use, solve, apply, predict, practise (see list)...or subject-specific verbs such as add, subtract, multiply, or calculate.

I can use multiplication to make an equivalent fraction with a common denominator

I can add the numerators together

All Categories

Sign up for the latest content and updates.

James Durran

Occasional posts on teaching, English and literacy

Re-thinking ‘success criteria’: a simple device to support pupils’ writing

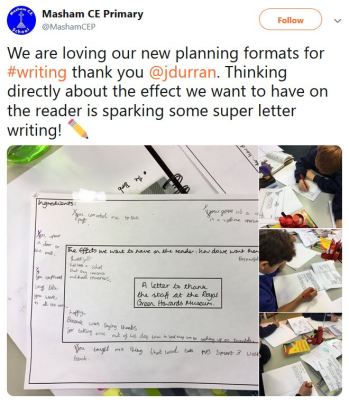

Colleagues and I have been working with primary schools to develop an alternative to listed ‘success criteria’ for writing, which we call ‘boxed’ or ‘expanding success criteria’ (or often just ‘the rectangles thing.’) It is very easy to adopt, and teachers have been finding that it can transform how writing is talked about and approached in the classroom, with an immediate impact on the quality of what pupils are producing. (That is something which we now need to research properly!)

When approaching a piece of writing, pupils are often given ‘success criteria’ in the form of a list of features which the writing ‘requires’ in order to be successful. These often include technicalities such as full stops and commas; they may include features such as metaphors, adjectives for description, varied sentence openers and so on; and they tend to include grammatical or cohesive devices, such as time adverbials, subordinate clauses or relative pronouns. In this way, they are tied explicitly to particular curriculum and teaching ‘objectives’.

These lists of ingredients clearly have usefulness – for reminding pupils of some things they might do to make the writing effective, for reinforcing learning, for providing a ready checklist for self and peer assessment, and so on. But teachers are increasingly aware of their potential drawbacks:

- They can promote a ‘writing-by-numbers’ approach, in which writing becomes a performance of features rather than a coherent whole.

- They can encourage teaching and task-setting by narrow text type, limiting the scope of what pupils might achieve.

- They are not really success criteria: the success of a piece of actual writing can only be measured by how well it communicates or achieves its purpose for its intended reader, not by whether it contains specified ingredients.

- Feedback – at the end or while drafting and editing – can therefore tend to focus just on whether specific elements are included, rather than on how effective the writing is as writing .*

Together, these interrelated factors can work against pupils’ development as real writers, writing for real purposes and real audiences. By ‘real’, we don’t mean a real life situation, like a letter to the school governors, or a story to be published, although there is an important place for such tasks; we mean an imagined but specific and authentic purpose and audience.

Purpose and audience: the starting point for teaching

If pupils are to write a recipe, it is simple and easy to give them a list like this:

- Lists of ingredients and equipment

- Numbered steps

- Time and sequence adverbials

- Imperative or command verbs

Certainly, these things are a useful starting point. But ask pupils then to compare the following two fragments, each giving exactly the same instruction …

Add Worcester sauce for extra flavour.

Slosh in some Worcester sauce to make it even yummier.

… and suddenly there is much more to consider and to teach. Who is the recipe for? Other children? A professional chef? Grandparents? What do they want and need? How can we engage them? What sort of verbs, nouns and adjectives might we therefore use? And so on. This is much more interesting for pupils. It is certainly more fun to teach.

It is important to teach about genre and about the features of different kinds of writing. But teachers know that, when pupils move on from thinking just in terms of text type, their writing opens up, with much more potential for richness, variety and authenticity. An account of a trip – perhaps in the form of an article – is not just a ‘recount’: it can be engagingly descriptive; it will have elements of entertaining narrative; it is likely to involve explanation, and even elements of persuasion and argument. Similarly a brochure about a town should be much more than a ‘non-chronological report’: depending on the intended audience, it will modulate between and blend elements of description, narrative, explanation, instruction and persuasion.

Purpose and audience: the starting point for feedback

Thinking about how to move on the pupil writing this story opening, it is easy to start listing technical or stylistic devices.

Billy went into the house. He looked into the kitchen. He saw a big dog. The dog ran to him.

The child could use more conjunctions, and perhaps a fronted adverbial or two. She could add description, using adjectives and adverbs. Perhaps she could expand some noun-phrases.

But, of course, the first question to ask this child is not ‘Could you use some…?’ or ‘Can you add in…?’ It is, simply: ‘What sort of story is this, and how do you want the reader to feel?’ Then things move forward. If it is a scary story, then perhaps the verb ‘went’ could be replaced by a scarier verb, with a scary adverb, such as ‘crept slowly’. Meanwhile, ‘looked’ could become ‘peered nervously’. The kitchen could be ‘dark and shadowy’. The dog could be ‘lion-like’ and it could ‘charge’ rather than ‘run’. The last sentence could be fronted with ‘Suddenly,…’ If it is a sad story, he might ‘walk slowly’ into the house, the kitchen could be ‘gloomy’. If it is happy, then he might ‘skip’ and the dog might ‘bounce’ up to him. And so on.

The ‘boxed’ or ‘expanding’ success criteria

So traditional ‘success criteria’ are really the wrong way round. They define ‘success’ in terms of the presence of ingredients, not in terms of the actual point of the writing.

The boxed criteria keep the ingredients, but link them explicitly to purpose and to the reader. It’s really that simple. In the middle, pupils put what the writing is and its intended audience; outwards from this are the intended ‘effects’ on that audience, or what the writing is meant to provide for its readers; outwards again are the ingredients – the features which might help to achieve these things.

For example, a guide for children to looking after a chosen pet animal might be planned like this:

The ‘boxed success criteria’ for the story (above) of Billy entering the house might look like this:

Note that in this example the ingredients are themselves described in terms of their impact: ‘scary nouns’, ‘frightening adjectives’ and ‘spooky similes’. Grammatical forms should be used for a reason, not for their own sake.

The grid might be created by the teacher and given to the pupils. It is more likely, however, that it will be constructed out of discussion with the class, and out of their reading and picking apart of examples. In the example below, for a description of what lies behind a mysterious door, the ingredients have come directly from discussion of an example text, and the outermost layer has been used for assembling examples of language.

Pupils might have their own grid in their books. (In the one below, the school has kept the label of ‘success criteria’ for the ingredients layer, to ease the transition to a new format!)

Or there might be a big class one on the wall.

Either way, it can be a dynamic, evolving thing, added to and adjusted as ideas are developed and shared through the planning, drafting and editing stages of writing. This is a tool which can live with the piece of writing through its stages: from reading and exploring examples, to planning and assembling ideas, to drafting and editing, to proof-reading, to publication, to reflection. And of course, at every stage, the starting point for teacher, peer or self-assessment and feedback is not a list of ingredients, but whether the writing is achieving what it is meant to achieve.

There is nothing radical or intrinsically innovative about this. It is just a visual device for focusing the thinking of teachers and pupils on what writing is actually about: communication and effect, not just the performance of skills.

___________________________

* In the article Objectives and purpose in English , I wrote this about the hazards of misapplied success criteria:

In their 2014 report for CfBT on educational blogging and its effects on writing, Myra Barrs and Sarah Horrocks noted a discrepancy between primary teachers’ views of what makes ‘good writing’ and that of their pupils. The teachers valued “good content and ideas”, “real meaning and purpose”, “imagination, originality and creativity”, “fluency and momentum” and “a strong sense of a reader/audience.” In contrast, pupils’ conception of ‘good writing’ “reflected the teachers’ marking of their books, and the learning objectives and targets that they were used to: ‘It would need ‘wow’ words to impress me’; ‘Good sentences full of adjectives’; ‘Describing. Good punctuation’; ‘Vocabulary that catches attention’ ‘Description and similes.’”

Pupils tend to define success in terms of such mechanistic attributes because these – rather than the real purposes of reading, writing or talking – are so often the starting point in lessons. They also dominate the checklists of ‘success criteria’ given to children when they embark on tasks. A description will be ‘successful’ not if it ‘makes the reader feel as though they are there’ but if it contains at least one metaphor, at least one simile, some adjectives, and so on. A persuasive letter will be successful not if it is ‘powerful’ but if it contains all the elements of ‘AFOREST’ or ‘SPEARFACTOR’. And a response to a poem will be successful not if it convinces or is interesting, but if it contains P.E.E. paragraphs, quotations and at least three ideas. All of these elements may be useful, but they are ingredients not recipes. Checklists of features can limit, rather than raise, attainment, if they are allowed to define success.

It is often easy to spot where such features are being deployed by children, keen to ‘move up a level’ rather than, perhaps, to be real writers. In this piece, a Year 5 boy steeped in the excitable rhythms and language of football reports, writes:

All the fans were booing around the ground. We got a free kick. Our striker was taking it. He whipped it past the wall. We were level at half time. He celebrated by sliding on his knees. The goal was fantastic to watch – curved it to the top corner, wow! The ref blew his whistle for half time. The fans were singing.

Redrafting it, he dutifully writes in more detail, adds description and uses more adjectives, with ruinous results.

All the fans booing really loud around the ground. We got a free kick. The striker was number 10 and had orange boots. He took a run up at the football. He struck it. It went around the wall and went into the top corner. The player celebrated by sliding on his knees through the wet green grass. It was nearly half time. We were levelling. The ref blew his whistle for half time. The manager gave the number 10 a high five. The team went into the big changing room to talk about the plan for the next half.

For years, I have used in training an extract from a Year 7 girl’s writing, which I was given by Simon Wrigley. In her first draft, she introduces the reader to her main character like this.

His mates called him Flash Harry because he was a rich photographer who liked to flash his cash around. They weren’t really his friends, of course, because he was too horrible to have any friends. He had yellow teeth and always smelt of beer. He was also very rude.

In her second draft, she ‘improves’ her description.

His friends called him Flash Harry as he was a wealthy photographer who loved showing off his money. They were not really his friends due to the fact that he was an extremely rude alcoholic with yellowing teeth.

The feedback that she was given on her draft, the objectives that she was chasing and the ‘success criteria’ that she was following are long lost. However, it is quite fun to guess. What is very clear is the way that her second draft, although ticking off such ‘higher-level’ features as more sophisticated language (‘wow words’?), a more formal register and more varied connectives, has lost the vitality and the narrative richness of the first. A great piece of real story-telling has become a performance of skills, dislocated from real purpose.

Share this:

23 thoughts on “ re-thinking ‘success criteria’: a simple device to support pupils’ writing ”.

Please can you tell me which text you used to lead to the ‘Behind the door’ boxed success criteria example? I found these ideas really inspirational. Thank you.

Hi. Thanks! It was an abridged version of Alice in Wonderland, but I can’t remember which one now! I’ll try to find out.

Thank you. I’ve been feeling this too (writing to a checklist can deaden and stifle the writer’s voice) and will try out your ideas.

This is fab. Thanks for sharing!

- Pingback: Re-thinking ‘success criteria’: a simple device to support pupils’ writing James Durran (@jdurran) – teachingandlearningblog

- Pingback: 5 Ways To Make Room for Ownership with “Learning Targets” – HonorsGradU

Thanks James – This is a great approach and I successfully tried it with my class here in Tokoroa, New Zealand this week – so much more meaningful and user-friendly than We are Learning to’s and a list of success criteria.

I really love the boxed approche, I will certainly try it in my french class. The only hesitation I have is that my curriculum has different categories : Knowledge and Understanding, Thinking, Communication and Application. How would you go about to include these in the boxed technique ? Or would it be better to not bother and focus on the text as a whole ? Thanks again for the great post, I don’t really know how I happened to find it, but I’m glad I did! Bye Alex Ottawa, Canada

- Pingback: BLOGAGGEDON – mrmorgs

I was introduced to your idea of rectangles by the Devon literacy team. I have been trialling it my year 1/2 class and have found that we are much more focussed on the purpose of the text and how it comes across to the reader. I am about to plan a unit of poetry and wondered what your views were on the purpose of poetry. My poem tells people about the things that happen in Spring but why would I do it in poem format and not just sentences or an information text? Am I over thinking purpose?