- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Case Study Research in Counselling and Psychotherapy

- John McLeod - University of Oslo, Norway

- Description

- the role of case studies in the development of theory, practice and policy in counselling and psychotherapy

- strategies for responding to moral and ethical issues in therapy case study research

- practical tools for collecting case data

- 'how-to-do-it' guides for carrying out different types of case study

- team-based case study research for practitioners and students

- questions, issues and challenges that may have been raised for readers through their study.

Concrete examples, points for reflection and discussion, and recommendations for further reading will enable readers to use the book as a basis for carrying out their own case investigation.

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

This text offers students the opportunity to grasp the importance of using case studies to inform research and is recommended for our students taking an Introduction to Evidence based practice in counselling module

An excellent textbook with clear guidelines to help students understand the importance of developing consistent methods for gathering evidence as they work with cases. The role of case studies for students as they learn about the different theories is essential for them to grasp a practical understanding of applications. This book covers the knowledge of writing case reports in a clear and comprehensive way.

John McLeod is and probably always will be the author we recommend when talking about evidence based practice. His other texts in Doing Counselling Research and Qualitative Research are seminal in this context. This text fills the gap around working with case studies in research, and is very relevant as this is an area that most counsellors will need to be familiar with. The book is well written and if possible makes the subject even more approachable and interesting. Our third year students are now recommended to read this title in relation to all of the third year professional level study modules, as it offers so the opportunity to become familiar with research methodologies and language.

An excellent book which helps people understand the ethics and processes involved in a case study approach. Some very useful examples contained within the book which makes the subject understandable. It has provided me with the motivation to consider applying this in my own practice.

Part of the beauty of this book is the accessibility of the author; as he brings the reader through an exciting, interesting, pragmatic and richly informed account of living qualitative research in action. The book considers; pragmatic, n=1, HSCED, theory-building adn one of my personal favourites - narrative approaches. This book is a required resource for anyone interested in qualitative research or therapy practice. A gem.

A thorough and rigorous review of the latest developments in case study research. Important reading for all counselling and psychotherapy research students, and practitioners who want to write up their clinical work.

This is a useful book, that makes a considered case for the the use of Case Studies for effective research as well as a developmental method for students.

Excellent book, which fills a gap in the current literature; especially useful in clinical psychology training where alternatives to n=1 empirical case studies are not widely accepted.

this has everything that you need for researching

This book has been useful in thinking about revalidation the Social Work degree and its themes will take a more central part in the revalidated degree from 2011-12 onwards.

Preview this book

Sample materials & chapters.

Foreword by Daniel B. Fishman, Ph.D., Rutgers University

For instructors

Select a purchasing option, related products.

This title is also available on SAGE Research Methods , the ultimate digital methods library. If your library doesn’t have access, ask your librarian to start a trial .

Change Password

Your password must have 6 characters or more:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

Create your account

Forget yout password.

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password

Forgot your Username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

- March 15, 2024 | VOL. 77, NO. 1 CURRENT ISSUE pp.1-42

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has updated its Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , including with new information specifically addressed to individuals in the European Economic Area. As described in the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences.

Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

Recovery in First-Episode Psychosis: A Case Study of Metacognitive Reflection and Insight Therapy (MERIT)

- Bethany L. Leonhardt , Psy.D. ,

- Kristen Ratliff , M.S. ,

- Jenifer L. Vohs , Ph.D.

Search for more papers by this author

Despite historically pessimistic views from both the professional community and lay public, research is emerging that recovery from psychosis is possible. Recovery has evolved to include not only a reduction in symptoms and return to functioning, but a sense of agency and connection to meaningful roles in life. The development of a more comprehensive conceptualization of recovery has particular importance in the treatment of first-episode psychosis, because early intervention may avoid some of the prolonged dysfunction that may make recovery difficult. As the mental health field moves to intervene early in the course of psychosis and to support recovery for individuals with severe mental illness, it is essential to develop and assess interventions that may promote a more comprehensive recovery. This case illustration offers an account of a type of integrative psychotherapy that may assist individuals in achieving recovery: metacognitive reflection and insight therapy (MERIT).

Despite early pessimism about the chronicity and course of schizophrenia spectrum disorders in psychiatry, there has been a shift in discussion in research, treatment, and policy suggesting that recovery from severe mental illness is possible. Various factors have contributed to this shift, including long-term outcomes studies that show a heterogeneous course for those with schizophrenia spectrum disorders ( 1 ), as well as a shift in the conceptualization of recovery in serious mental illness. Due to a grassroots movement of activists and scholars embracing a broadened view of recovery, recovery now includes a process of regaining autonomy over one’s life and a return to meaningful life roles, even in the face of persisting symptoms or difficulties ( 2 , 3 ). This aspect of recovery is called many things, including recovery as process and subjective recovery. Included in this definition of recovery is that individuals see themselves as more than a mental health patient, feel empowered to make decisions about their lives and health care, and can participate in aspects of their community that are meaningful to them ( 2 ).

This broadened view of recovery has several implications for interventions offered to individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. In particular, with a recent emphasis on intervening early in the course of illness, or first-episode psychosis (FEP), a broadened view of recovery has implications for the types of interventions offered in FEP clinics. The literature to date has shown that early intervention in FEP is related to a range of improved outcomes ( 4 ), yet these outcomes are often more objectively defined, such as symptom remission, use of acute services, and level of functioning. While these outcomes are important, it remains unanswered how early intervention can assist individuals with FEP to attain subjective recovery.

One promising intervention that may assist in promoting recovery in FEP is metacognitive reflection and insight therapy (MERIT; 5 ). MERIT is an integrative psychotherapy that targets metacognition. Metacognition refers to a range of cognitive activities that allow one to form complex, flexible accounts of one’s own life, as well as of significant others, and to use this knowledge to respond to a range of psychosocial problems ( 6 ). Deficits in metacognition have been found to exist in schizophrenia spectrum disorders ( 7 , 8 ), to be stable ( 9 ), and to be present across all phases of illness, including FEP ( 10 ). Promoting metacognition may assist persons in moving toward subjective recovery because it may be necessary to think in a sophisticated way about oneself to obtain this type of recovery. For example, thinking flexibly and coherently about oneself may allow one to see oneself as more than a mental health patient, to identify a range of passions and life roles that would make one’s life fulfilling, and to be able to respond flexibly to psychosocial distress.

There is some evidence to suggest that higher metacognition is related to an improved sense of subjective recovery in those with schizophrenia spectrum disorders ( 11 ), and offering interventions such as MERIT that specifically target metacognition may assist in promoting recovery. In fact, in a sample of individuals with prolonged psychosis, metacognitively oriented psychotherapy was found to assist in forming a coherent sense of self and to ultimately promote recovery ( 12 ). Additionally, case studies have been reported examining the use of MERIT as an intervention to target and promote insight in FEP ( 13 , 14 ). The following case builds upon this work to illustrate the use of MERIT as an intervention promoting recovery in FEP.

Presenting Problem and Client Background

The client for this case will be referred to as Grohl. All identifying information has been altered to protect his confidentiality. Grohl is a single male in his early to mid-20s who was diagnosed as having schizophrenia two years prior to his engagement in therapy. He grew up as the eldest of three children in a middle-class family and reported no developmental concerns or delays. Grohl described himself as having many friends during his childhood and reported he was involved in extracurricular activities and performed well in school. Prior to his diagnosis of schizophrenia, he had no other mental health diagnoses or mental health treatment. He was a talented artist and was active in his high school’s art community. He and his parents noted a change after high school in which Grohl became less social and struggled academically in his college classes. Immediately after high school, Grohl relocated from living with his family of origin to living with his grandfather in a different city in the same state. He had limited contact with his family of origin during that time and began to experience a change in his level of psychosocial functioning: socially withdrawing, failing to keep jobs, and eventually dropping out of school. Grohl’s grandfather struggled with substance abuse during this time and was actively using substances while Grohl lived with him. Grohl and his parents reported that there were often verbal and physical fights as a result of Grohl’s grandfather’s substance use and overall this was a tumultuous time for Grohl. Grohl’s own substance use included occasional marijuana and alcohol in high school, and he reported drinking alcohol several times per week while living with his grandfather. He had legal charges related to an arrest for underage drinking.

During the onset of Grohl’s illness, he began to believe a range of persecutory delusions that often centered on his physical health, stating that others were poisoning him and noting strange physical sensations that he believed were a result of the poison he was administered. His grandfather took him to a behavioral health center where Grohl was diagnosed as having schizophrenia and an oral second-generation antipsychotic was prescribed, which he took intermittently. Grohl lived with his grandfather and occasionally sought medical assistance for physical sensations for one-and-a-half years before he visited emergency rooms in several states, attempting to convince hospital staff that he was being poisoned and requesting medical attention. Grohl would leave the emergency room before care could be administered. He was eventually detained by the police due to erratic behavior and was transferred to an inpatient hospital close to his parents’ residence. It was following this hospitalization that Grohl was linked to the early psychosis clinic. While on the inpatient unit, Grohl was involuntarily committed due to his refusal to take medications and his attempts to leave the unit against medical advice. He began receiving an injection of paliperidone palmitate. Grohl eventually moved to a supported living environment and attended an outpatient clinic, receiving case management and medication services for six months before agreeing to psychotherapy. He remained on a stable dose of his medications during the duration of the therapy presented below, and he received services from a multidisciplinary team, including case management and supported employment services. In addition, because of Grohl’s somatic complaints, he received care at several primary and specialty care clinics to evaluate his health. He received a diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease and was treated for this condition. He received no other medical diagnoses.

When Grohl began therapy, he was primarily experiencing negative symptoms. He experienced thought blocking, prolonged response latency, anhedonia, and flat affect. He described that his mind was “empty” and noted that he spent much of his day lying in his bed. Grohl was unemployed at the time and saw his family once per week when his parents picked him up for a family Sunday dinner. He had no other social contact. He endorsed avolition, noting that despite being bored much of the time he was not motivated to engage in any behaviors that he used to find enjoyable, such as creating art, spending time in Internet forums, or spending time with his friends. Grohl was quiet, rarely made eye contact, and often came to his psychotherapy session appearing disheveled.

Case Conceptualization

Grohl’s deficits in metacognition were assessed with the Metacognition Assessment Scale-Abbreviated (MAS-A; 15 ), which is an adaptation of the original MAS ( 16 ) and includes four domains of metacognition: self-reflectivity, awareness of others, decentration, and mastery. Each part of the scale is hierarchical, with higher scores representing increased capacity to perform the complex mental tasks of each domain. Self-reflectivity refers to the ability to acknowledge and identify internal states and to ultimately form flexible understandings of oneself and one’s unique life events over time. Grohl initially had low self-reflectivity. Although he was able to distinguish a range of cognitive operations, he was unable to name a nuanced range of emotions or recognize that his thoughts were fallible, giving him a score of 3 out of 9 on the self-reflectivity scale. For example, Grohl remained convinced that he was being poisoned by an unnamed entity and remained adamant that he had holes in his head that were causing discomfort in his body. Awareness of others refers to the ability to consider other people’s internal states and to make guesses about their intentions. Grohl also scored low in this capacity. He recognized that others had their own internal states but was unable to name a range of emotions significant others in his life might experience and struggled to guess their intentions. He was evaluated at a 3 out of a possible score of 7 on this subscale of the MAS-A. Decentration refers to the ability to recognize that one is not the center of all activities and that other people have differing, valid opinions separate from one’s own. Grohl tended to view events as being connected to him, often believing that others wished him harm, and failed to consider that others in his life had lives outside of his. He scored 0 out of 3 on this scale. Finally, mastery refers to the ability to use knowledge about oneself to respond in increasingly complex ways to psychological problems. Grohl initially came to therapy without a clear psychological problem, often stating that something had gone wrong in his life but attributing that distress to the malicious, unnamed individuals who he believed were causing his physical sensations. Thus, his score on mastery was a 1.5 out of 9.0 because he did not meet the criteria of articulating a plausible psychological problem.

Course of Treatment

The therapy described below refers to an 18-month period of weekly individual psychotherapy utilizing MERIT. MERIT is an integrative psychotherapy with eight core elements incorporated into each session. These elements can be used along with a range of therapeutic approaches and offer therapists a method of building upon existing skills and conceptualizations and employing a flexible framework that centers on increasing the client’s metacognitive capacity ( 17 ). Each of these elements is briefly defined below, along with a description of how that element was addressed in Grohl’s psychotherapy.

Element 1: The Preeminent Role of the Client’s Agenda

This element refers to, first and foremost, establishing what the client wants from the session that day. Agendas are often not clearly articulated, and it is possible for clients to have multiple, and at times conflicting, agendas at once. For example, a client could wish that a therapist agree that he or she is a victim of a jealous neighbor or may want the therapist to view him or her as independent and capable. Attending to these agendas requires that therapists be curious about and attentive to the ways in which the client’s desires pull for a reaction in a session, whether it is to be viewed a certain way or for the therapist to take a certain action.

Initially, Grohl’s agenda appeared to be to convince the therapist that he did not have a mental illness and to get her to agree with his belief that others were causing his physical symptoms through attacks on him in his sleep. Grohl often was adversarial with his psychiatrist, asserting that he did not have schizophrenia and noting his anger at being forced to take medications he did not believe he needed. The therapist responded to these agendas with curiosity about Grohl’s physical symptoms and attempted to gather a timeline and narrative episodes surrounding the onset of these symptoms. When Grohl would directly ask the therapist to align with him against his psychiatrist by asking whether she agreed that he did not have schizophrenia but was the victim of a conspiracy, she responded by reflecting on the dynamics of Grohl’s agenda and with curiosity about what her agreement would mean to him. The therapist would then request more information about Grohl’s experience to better understand what he was experiencing. It seemed important to the therapist that she remain open to and curious about Grohl’s agenda rather than attempting to promote her own agenda (such as improving insight or adherence to treatment). The therapist’s openness seemed to allow Grohl to move at a pace with which he was comfortable, which ultimately seemed to promote trust and further exploration of Grohl’s life story. However, at times moving at Grohl’s pace was difficult, and often the treatment team would experience impatience or anxiety as Grohl continued to attempt to get body scans or other medical procedures to address his somatic experiences.

Element 2: Introduction of the Therapist’s Thoughts as Dialogue

This element refers to the therapist offering his or her own reflections and reactions throughout the session to promote dialogue. The therapist’s mental contents are fodder for reflection and not presented as fact or a more accurate view of reality but to encourage the client to react to the therapist’s reflections so the two can think together about them.

The therapist initially achieved this element with Grohl by stating her confusion about the claims he was asserting regarding his physical sensations. As Grohl provided more information and reflected upon the events surrounding the onset of these sensations, it occurred to the therapist that Grohl often experienced these strange sensations when he felt unsafe. He reported that the sensations began while living with his grandfather, who was unpredictable and often verbally and physically abusive to Grohl, including attacking him in his sleep. Since then, Grohl had moved into a supported living home with individuals with psychiatric needs in a neighborhood in the city that was known for being unsafe. Grohl often reported being most bothered by these physical symptoms when he was around others living in the home, and he reported that he did not experience these symptoms at his parents’ home. The therapist responded to Grohl by offering reflections such as “When you share these stories, it makes me wonder if you felt threatened,” and, “I have a thought that you felt unsafe staying with your grandfather.” The therapist would then invite Grohl to comment on her reflections.

Element 3: Eliciting Narrative Episodes

The third element of MERIT emphasizes the importance of eliciting narrative episodes to assist clients in developing a storied sense of their lives over time. This element was particularly important with Grohl and was challenging in the beginning due to his barren account of his life. Grohl described his life as being successful and positive until the physical sensations began, to which he attributed all his dissatisfaction with his current circumstances. The therapist elicited narratives by asking for more details about the onset of his physical symptoms and attempting to gather information about where he was living and with whom he was interacting. Eventually, she began to compile a timeline of Grohl’s life. He often responded to the therapist’s inquiries by stating that he could not remember his life. By revisiting the few narratives he could offer, Grohl eventually was able to provide more details to these narratives and slowly, narratives of other times arose. A richer picture of his life emerged, including his account of the abuse he endured while living with his grandfather, his sense of having failed at becoming an independent adult, his social discomfort in high school, and his remembering of his love and dedication to art. With this richer picture of his life, Grohl’s account of having experienced a perfect life prior to the onset of physical symptoms was challenged and evolved into a rich, storied sense of his unique life, including his challenges and triumphs. This richer version of Grohl’s life often caused him pain and discomfort, as he grappled with a sense of loss of dreams he previously had for himself and struggled with acceptance of painful interactions with significant others. Likewise, this process was difficult at times for the therapist as she watched Grohl struggle with painful aspects of his life and continued to encourage him to reflect and explore potentially distressing narratives. Despite the discomfort that often accompanied the increased reflectivity, Grohl appeared better able to make sense of his life. Exploring narratives seemed to allow Grohl to finally come to terms with experiencing psychiatric difficulties as well as to see himself as a full being and not only a psychiatric patient.

Element 4: The Psychological Problem

The fourth element refers to assisting clients in forming a plausible, mutually agreed upon psychological problem. The psychological problem often emerges from the understanding of the client’s agenda and narratives and may include a range of difficulties not restricted to a mental disorder. Examples of these difficulties could include struggling to connect with others in an adaptive manner or difficulty in understanding the intentions of others and thus navigating interactions.

Initially, Grohl struggled to form a plausible psychological problem and focused on implausible explanations for the distress he was experiencing. He often stated that others were poisoning him or performing operations on him while he was sleeping, leaving no trace of surgical scars when he woke. These expressions often left the therapist in a difficult position, because she could not join Grohl in these explanations of his difficulties. However, through exploration of the development of these physical sensations and the narratives he offered, Grohl began to articulate a psychological problem that something had gone wrong in his life and that he had gotten off track. He considered factors that could have influenced the course of his life, expanding these factors from his suspicions of others to include his decreased self-esteem caused by perceived failures, such as of losing jobs, dropping out of college, and new difficulties in connecting with others. Grohl’s understanding of his psychological problem continued to evolve as he discussed various narrative episodes in his life and considered what had changed. He began to acknowledge difficulties occurring earlier in his life and in particular reflected on the impact of his grandfather’s abuse. He described themes of feeling unsafe, struggling to perceive the intentions of others, and feeling left behind in life, as his peers and siblings established their autonomy in young adulthood in ways in which Grohl felt he should but was unable.

Element 5: Reflecting on Interpersonal Processes

This element requires attention to and reflection on the interpersonal dynamics occurring within the therapy sessions by both the therapist and client. This element was difficult with Grohl, who would struggle to describe his reactions to the therapist. He seemed initially unsure of the therapist and her intentions and would state that he was not sure what to talk about during the sessions. Grohl often noted surprise at having talked through the entire session.

Another significant interpersonal process in Grohl’s psychotherapy was seen in his attempts to convince his therapist that he did not have a mental illness and should not have to be in treatment. At times he would experience the therapist’s curiosity as challenging the legitimacy of what he was experiencing and would offer statements attempting to legitimize his experiences, such as “This isn’t all in my head” and “There is something seriously wrong with my body, and I’m afraid I’m going to die.” At times he perceived his therapist as being on his side and would attempt to recruit her help in procuring a body scan that would “prove” the damage he was sure was happening to his body. The therapist described her experience during these moments as feeling pulled in different directions by Grohl, and she would invite him to reflect on how he perceived her during these moments as well and to react to her reflections.

Element 6: Reflecting on the Process of Therapy Within and Across Sessions

In practicing element 6, the therapist invites feedback from the client on how the session has gone each time as well as to reflect on the therapy process as a whole. In MERIT, the process of therapy is viewed as an opportunity for reflection and dialogue about the connection between two individuals over time and how this connection can evolve. Initially, Grohl described that sessions went well but also noted his discomfort in knowing what to talk about. As he reflected on more of his life and developed a conceptualization of his psychological problem, Grohl would describe that he was thinking about his life differently as a result of therapy. He noted that these reflections were at times painful, particularly when describing memories of his earliest experiences of psychosis and traumatic interactions with his grandfather. The therapist would often observe a change in Grohl in the sessions following exploration of his relationship with his grandfather. Specifically, Grohl tended to describe his grandfather in an overwhelmingly positive manner in the sessions following his disclosure of painful moments with him. The therapist would note this change between sessions and explore with Grohl his ambivalence about his relationship with his grandfather and about discussing and reflecting on painful moments in his life.

Element 7: Stimulating Reflectivity of Self and Others

One of the hallmarks of MERIT is the stimulation of reflective activity at the appropriate level of metacognition. This stimulation requires the therapist to continuously assess clients’ current level of metacognitive capacity to reflect on the internal states of themselves and others. The therapist then offers interventions at that level or attempts to assist them to the next highest level through scaffolding. Offering interventions that are either too metacognitively complex or simple is viewed as ineffective as the client is being asked to reflect at a level that does not match his or her current capacity. Of note, metacognitive capacity is dynamic and changes between sessions and often even within sessions ( 18 ), so to effectively perform this element, therapists must frequently assess the client’s metacognitive capacity.

In this case, the therapist first needed to intervene to provide a scaffold for Grohl to express a range of nuanced emotions, as Grohl could describe a range of cognitive operations but could not identify how he was feeling in various narratives. The therapist performed this intervention by inviting Grohl to describe the circumstances around the beginning of his physical symptoms. This encouragement led him to describe narrative episodes that, while initially barren, gave some material for Grohl and the therapist to reflect upon. The therapist would stimulate self-reflectivity by asking Grohl to describe his reactions to events in these narratives and the various feelings within his body during those moments. The therapist would offer labels for emotions and at times would describe her own guesses about how she might feel if she were experiencing the narrative Grohl described, exploring how those guesses fit or did not fit for Grohl, fine-tuning his understanding of how he was feeling. During the exploration of these initial barren narratives, Grohl began offering narratives from earlier periods in his life, and more details emerged, particularly his complicated and traumatic interactions with his grandfather. As Grohl developed his ability to reflect on a range of emotions, the therapist also began to scaffold the fallibility of thoughts, assisting Grohl in exploring how his thoughts had changed over time. He was most able to do this when thinking about events in the past, and he struggled to recognize that his current thoughts were also fallible. To address this, the therapist would invite Grohl to reflect on his certainty within the moment and how that differed from times in the past when his thoughts had changed. Ultimately, as Grohl began reflecting on his life in more detail and began to integrate the circumstances of significant points of his life, he developed a more complex understanding of himself and the psychosocial events he had experienced.

When Grohl began to offer narrative episodes that included significant others in his life, the therapist targeted his ability to understand the internal states of other people. Grohl initially struggled to recognize a range of nuanced emotion in others. As he developed the capacity to describe his own nuanced emotional states, he began to consider the emotional states of others. When Grohl considered his family dynamics, the therapist would often stimulate reflectivity of others by asking Grohl how he thought his parents viewed or reacted to significant events. He began to articulate, and form guesses about how certain events, such as the onset of his illness, had affected others in his family. As Grohl considered the impact his relationship with his grandfather had upon him, he was receptive to interventions that invited him to reflect upon aspects of his grandfather’s life that may have influenced his grandfather’s behavior. Grohl began to think flexibly about an individual who had caused him much pain and developed some hypotheses about what may have influenced his grandfather’s behavior.

Element 8: Stimulating Psychological Mastery

The eighth and final element of MERIT requires the therapist to offer interventions to stimulate metacognitive mastery, or the use of knowledge of self and others to respond to psychological distress. Similar to stimulating reflectivity of self and others at the correct metacognitive level, mastery interventions also must be tailored to the metacognitive capacity of the client. Stimulation of mastery includes assisting clients to form a plausible psychological problem and then to develop increasingly complex ways to master the problem. Interventions become more complex as they include the knowledge gained in reflection about self and others to navigate difficulties in life.

For Grohl, the therapist first began to stimulate mastery by offering interventions to promote reflectivity about what his plausible psychological problem might be. As discussed in the fourth element, Grohl initially struggled to articulate a problem that was plausible, but through exploration of the onset of his physical problems, he was eventually able to describe that his life had gotten off track and to acknowledge his difficulty in assessing others’ intentions and interacting successfully. As Grohl became more reflective of significant moments in his past, he began to describe the fulfillment he found while creating art. He began to create again and engaged this part of himself, eventually even agreeing to do contracted pieces of art as he had in the past. Being paid to create caused Grohl great anxiety initially, as he wondered whether he would perform to his past abilities and feared he might disappoint those who were paying him. However, he was successful with his first few pieces, and this success improved his self-esteem and sense of agency over aspects of his life.

As Grohl began to gain self-confidence and continued to reflect on the change he noticed in his life’s trajectory, his explanation of his psychological problem again evolved. He began to describe narratives he had previously not mentioned and acknowledged experiencing psychotic symptoms, which he had formerly denied. What emerged was a more complex understanding of the unique life circumstances that had led him to experience a high level of stress and a sense of being lost. He reflected on his history of being anxious as a child and as a rebellious teenager, and he noted how he had often overcompensated for his insecurity by acting out while in high school. Grohl abandoned the narrative that he had previously stated, that all was perfect in his life prior to his physical sensations and described a childhood of uncertainty that included moments of strength and happiness. Describing the moments of happiness led him to conclude that it was important to connect more with his family of origin and with the passions he had, including art.

Case study definition

Case study, a term which some of you may know from the "Case Study of Vanitas" anime and manga, is a thorough examination of a particular subject, such as a person, group, location, occasion, establishment, phenomena, etc. They are most frequently utilized in research of business, medicine, education and social behaviour. There are a different types of case studies that researchers might use:

• Collective case studies

• Descriptive case studies

• Explanatory case studies

• Exploratory case studies

• Instrumental case studies

• Intrinsic case studies

Case studies are usually much more sophisticated and professional than regular essays and courseworks, as they require a lot of verified data, are research-oriented and not necessarily designed to be read by the general public.

How to write a case study?

It very much depends on the topic of your case study, as a medical case study and a coffee business case study have completely different sources, outlines, target demographics, etc. But just for this example, let's outline a coffee roaster case study. Firstly, it's likely going to be a problem-solving case study, like most in the business and economics field are. Here are some tips for these types of case studies:

• Your case scenario should be precisely defined in terms of your unique assessment criteria.

• Determine the primary issues by analyzing the scenario. Think about how they connect to the main ideas and theories in your piece.

• Find and investigate any theories or methods that might be relevant to your case.

• Keep your audience in mind. Exactly who are your stakeholder(s)? If writing a case study on coffee roasters, it's probably gonna be suppliers, landlords, investors, customers, etc.

• Indicate the best solution(s) and how they should be implemented. Make sure your suggestions are grounded in pertinent theories and useful resources, as well as being realistic, practical, and attainable.

• Carefully proofread your case study. Keep in mind these four principles when editing: clarity, honesty, reality and relevance.

Are there any online services that could write a case study for me?

Luckily, there are!

We completely understand and have been ourselves in a position, where we couldn't wrap our head around how to write an effective and useful case study, but don't fear - our service is here.

We are a group that specializes in writing all kinds of case studies and other projects for academic customers and business clients who require assistance with its creation. We require our writers to have a degree in your topic and carefully interview them before they can join our team, as we try to ensure quality above all. We cover a great range of topics, offer perfect quality work, always deliver on time and aim to leave our customers completely satisfied with what they ordered.

The ordering process is fully online, and it goes as follows:

• Select the topic and the deadline of your case study.

• Provide us with any details, requirements, statements that should be emphasized or particular parts of the writing process you struggle with.

• Leave the email address, where your completed order will be sent to.

• Select your payment type, sit back and relax!

With lots of experience on the market, professionally degreed writers, online 24/7 customer support and incredibly low prices, you won't find a service offering a better deal than ours.

Psychology: Research and Review

- Open access

- Published: 19 March 2021

Appraising psychotherapy case studies in practice-based evidence: introducing Case Study Evaluation-tool (CaSE)

- Greta Kaluzeviciute ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1197-177X 1

Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica volume 34 , Article number: 9 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

7149 Accesses

3 Citations

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

Systematic case studies are often placed at the low end of evidence-based practice (EBP) due to lack of critical appraisal. This paper seeks to attend to this research gap by introducing a novel Case Study Evaluation-tool (CaSE). First, issues around knowledge generation and validity are assessed in both EBP and practice-based evidence (PBE) paradigms. Although systematic case studies are more aligned with PBE paradigm, the paper argues for a complimentary, third way approach between the two paradigms and their ‘exemplary’ methodologies: case studies and randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Second, the paper argues that all forms of research can produce ‘valid evidence’ but the validity itself needs to be assessed against each specific research method and purpose. Existing appraisal tools for qualitative research (JBI, CASP, ETQS) are shown to have limited relevance for the appraisal of systematic case studies through a comparative tool assessment. Third, the paper develops purpose-oriented evaluation criteria for systematic case studies through CaSE Checklist for Essential Components in Systematic Case Studies and CaSE Purpose-based Evaluative Framework for Systematic Case Studies. The checklist approach aids reviewers in assessing the presence or absence of essential case study components (internal validity). The framework approach aims to assess the effectiveness of each case against its set out research objectives and aims (external validity), based on different systematic case study purposes in psychotherapy. Finally, the paper demonstrates the application of the tool with a case example and notes further research trajectories for the development of CaSE tool.

Introduction

Due to growing demands of evidence-based practice, standardised research assessment and appraisal tools have become common in healthcare and clinical treatment (Hannes, Lockwood, & Pearson, 2010 ; Hartling, Chisholm, Thomson, & Dryden, 2012 ; Katrak, Bialocerkowski, Massy-Westropp, Kumar, & Grimmer, 2004 ). This allows researchers to critically appraise research findings on the basis of their validity, results, and usefulness (Hill & Spittlehouse, 2003 ). Despite the upsurge of critical appraisal in qualitative research (Williams, Boylan, & Nunan, 2019 ), there are no assessment or appraisal tools designed for psychotherapy case studies.

Although not without controversies (Michels, 2000 ), case studies remain central to the investigation of psychotherapy processes (Midgley, 2006 ; Willemsen, Della Rosa, & Kegerreis, 2017 ). This is particularly true of systematic case studies, the most common form of case study in contemporary psychotherapy research (Davison & Lazarus, 2007 ; McLeod & Elliott, 2011 ).

Unlike the classic clinical case study, systematic cases usually involve a team of researchers, who gather data from multiple different sources (e.g., questionnaires, observations by the therapist, interviews, statistical findings, clinical assessment, etc.), and involve a rigorous data triangulation process to assess whether the data from different sources converge (McLeod, 2010 ). Since systematic case studies are methodologically pluralistic, they have a greater interest in situating patients within the study of a broader population than clinical case studies (Iwakabe & Gazzola, 2009 ). Systematic case studies are considered to be an accessible method for developing research evidence-base in psychotherapy (Widdowson, 2011 ), especially since they correct some of the methodological limitations (e.g. lack of ‘third party’ perspectives and bias in data analysis) inherent to classic clinical case studies (Iwakabe & Gazzola, 2009 ). They have been used for the purposes of clinical training (Tuckett, 2008 ), outcome assessment (Hilliard, 1993 ), development of clinical techniques (Almond, 2004 ) and meta-analysis of qualitative findings (Timulak, 2009 ). All these developments signal a revived interest in the case study method, but also point to the obvious lack of a research assessment tool suitable for case studies in psychotherapy (Table 1 ).

To attend to this research gap, this paper first reviews issues around the conceptualisation of validity within the paradigms of evidence-based practice (EBP) and practice-based evidence (PBE). Although case studies are often positioned at the low end of EBP (Aveline, 2005 ), the paper suggests that systematic cases are a valuable form of evidence, capable of complimenting large-scale studies such as randomised controlled trials (RCTs). However, there remains a difficulty in assessing the quality and relevance of case study findings to broader psychotherapy research.

As a way forward, the paper introduces a novel Case Study Evaluation-tool (CaSE) in the form of CaSE Purpose - based Evaluative Framework for Systematic Case Studies and CaSE Checklist for Essential Components in Systematic Case Studies . The long-term development of CaSE would contribute to psychotherapy research and practice in three ways.

Given the significance of methodological pluralism and diverse research aims in systematic case studies, CaSE will not seek to prescribe explicit case study writing guidelines, which has already been done by numerous authors (McLeod, 2010 ; Meganck, Inslegers, Krivzov, & Notaerts, 2017 ; Willemsen et al., 2017 ). Instead, CaSE will enable the retrospective assessment of systematic case study findings and their relevance (or lack thereof) to broader psychotherapy research and practice. However, there is no reason to assume that CaSE cannot be used prospectively (i.e. producing systematic case studies in accordance to CaSE evaluative framework, as per point 3 in Table 2 ).

The development of a research assessment or appraisal tool is a lengthy, ongoing process (Long & Godfrey, 2004 ). It is particularly challenging to develop a comprehensive purpose - oriented evaluative framework, suitable for the assessment of diverse methodologies, aims and outcomes. As such, this paper should be treated as an introduction to the broader development of CaSE tool. It will introduce the rationale behind CaSE and lay out its main approach to evidence and evaluation, with further development in mind. A case example from the Single Case Archive (SCA) ( https://singlecasearchive.com ) will be used to demonstrate the application of the tool ‘in action’. The paper notes further research trajectories and discusses some of the limitations around the use of the tool.

Separating the wheat from the chaff: what is and is not evidence in psychotherapy (and who gets to decide?)

The common approach: evidence-based practice.

In the last two decades, psychotherapy has become increasingly centred around the idea of an evidence-based practice (EBP). Initially introduced in medicine, EBP has been defined as ‘conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients’ (Sackett, Rosenberg, Gray, Haynes, & Richardson, 1996 ). EBP revolves around efficacy research: it seeks to examine whether a specific intervention has a causal (in this case, measurable) effect on clinical populations (Barkham & Mellor-Clark, 2003 ). From a conceptual standpoint, Sackett and colleagues defined EBP as a paradigm that is inclusive of many methodologies, so long as they contribute towards clinical decision-making process and accumulation of best currently available evidence in any given set of circumstances (Gabbay & le May, 2011 ). Similarly, the American Psychological Association (APA, 2010 ) has recently issued calls for evidence-based systematic case studies in order to produce standardised measures for evaluating process and outcome data across different therapeutic modalities.

However, given EBP’s focus on establishing cause-and-effect relationships (Rosqvist, Thomas, & Truax, 2011 ), it is unsurprising that qualitative research is generally not considered to be ‘gold standard’ or ‘efficacious’ within this paradigm (Aveline, 2005 ; Cartwright & Hardie, 2012 ; Edwards, 2013 ; Edwards, Dattilio, & Bromley, 2004 ; Longhofer, Floersch, & Hartmann, 2017 ). Qualitative methods like systematic case studies maintain an appreciation for context, complexity and meaning making. Therefore, instead of measuring regularly occurring causal relations (as in quantitative studies), the focus is on studying complex social phenomena (e.g. relationships, events, experiences, feelings, etc.) (Erickson, 2012 ; Maxwell, 2004 ). Edwards ( 2013 ) points out that, although context-based research in systematic case studies is the bedrock of psychotherapy theory and practice, it has also become shrouded by an unfortunate ideological description: ‘anecdotal’ case studies (i.e. unscientific narratives lacking evidence, as opposed to ‘gold standard’ evidence, a term often used to describe the RCT method and the therapeutic modalities supported by it), leading to a further need for advocacy in and defence of the unique epistemic process involved in case study research (Fishman, Messer, Edwards, & Dattilio, 2017 ).

The EBP paradigm prioritises the quantitative approach to causality, most notably through its focus on high generalisability and the ability to deal with bias through randomisation process. These conditions are associated with randomised controlled trials (RCTs) but are limited (or, as some argue, impossible) in qualitative research methods such as the case study (Margison et al., 2000 ) (Table 3 ).

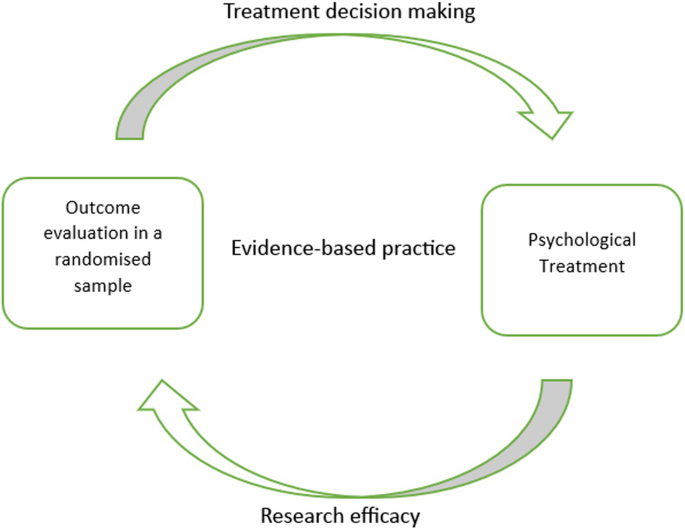

‘Evidence’ from an EBP standpoint hovers over the epistemological assumption of procedural objectivity : knowledge can be generated in a standardised, non-erroneous way, thus producing objective (i.e. with minimised bias) data. This can be achieved by anyone, as long as they are able to perform the methodological procedure (e.g. RCT) appropriately, in a ‘clearly defined and accepted process that assists with knowledge production’ (Douglas, 2004 , p. 131). If there is a well-outlined quantitative form for knowledge production, the same outcome should be achieved regardless of who processes or interprets the information. For example, researchers using Cochrane Review assess the strength of evidence using meticulously controlled and scrupulous techniques; in turn, this minimises individual judgment and creates unanimity of outcomes across different groups of people (Gabbay & le May, 2011 ). The typical process of knowledge generation (through employing RCTs and procedural objectivity) in EBP is demonstrated in Fig. 1 .

Typical knowledge generation process in evidence–based practice (EBP)

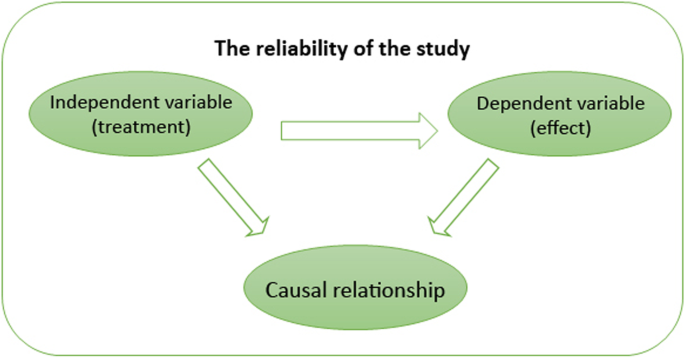

In EBP, the concept of validity remains somewhat controversial, with many critics stating that it limits rather than strengthens knowledge generation (Berg, 2019 ; Berg & Slaattelid, 2017 ; Lilienfeld, Ritschel, Lynn, Cautin, & Latzman, 2013 ). This is because efficacy research relies on internal validity . At a general level, this concept refers to the congruence between the research study and the research findings (i.e. the research findings were not influenced by anything external to the study, such as confounding variables, methodological errors and bias); at a more specific level, internal validity determines the extent to which a study establishes a reliable causal relationship between an independent variable (e.g. treatment) and independent variable (outcome or effect) (Margison et al., 2000 ). This approach to validity is demonstrated in Fig. 2 .

Internal validity

Social scientists have argued that there is a trade-off between research rigour and generalisability: the more specific the sample and the more rigorously defined the intervention, the outcome is likely to be less applicable to everyday, routine practice. As such, there remains a tension between employing procedural objectivity which increases the rigour of research outcomes and applying such outcomes to routine psychotherapy practice where scientific standards of evidence are not uniform.

According to McLeod ( 2002 ), inability to address questions that are most relevant for practitioners contributed to a deepening research–practice divide in psychotherapy. Studies investigating how practitioners make clinical decisions and the kinds of evidence they refer to show that there is a strong preference for knowledge that is not generated procedurally, i.e. knowledge that encompasses concrete clinical situations, experiences and techniques. A study by Stewart and Chambless ( 2007 ) sought to assess how a larger population of clinicians (under APA, from varying clinical schools of thought and independent practices, sample size 591) make treatment decisions in private practice. The study found that large-scale statistical data was not the primary source of information sought by clinicians. The most important influences were identified as past clinical experiences and clinical expertise ( M = 5.62). Treatment materials based on clinical case observations and theory ( M = 4.72) were used almost as frequently as psychotherapy outcome research findings ( M = 4.80) (i.e. evidence-based research). These numbers are likely to fluctuate across different forms of psychotherapy; however, they are indicative of the need for research about routine clinical settings that does not isolate or generalise the effect of an intervention but examines the variations in psychotherapy processes.

The alternative approach: practice-based evidence

In an attempt to dissolve or lessen the research–practice divide, an alternative paradigm of practice-based evidence (PBE) has been suggested (Barkham & Mellor-Clark, 2003 ; Fox, 2003 ; Green & Latchford, 2012 ; Iwakabe & Gazzola, 2009 ; Laska, Motulsky, Wertz, Morrow, & Ponterotto, 2014 ; Margison et al., 2000 ). PBE represents a shift in how we think about evidence and knowledge generation in psychotherapy. PBE treats research as a local and contingent process (at least initially), which means it focuses on variations (e.g. in patient symptoms) and complexities (e.g. of clinical setting) in the studied phenomena (Fox, 2003 ). Moreover, research and theory-building are seen as complementary rather than detached activities from clinical practice. That is to say, PBE seeks to examine how and which treatments can be improved in everyday clinical practice by flagging up clinically salient issues and developing clinical techniques (Barkham & Mellor-Clark, 2003 ). For this reason, PBE is concerned with the effectiveness of research findings: it evaluates how well interventions work in real-world settings (Rosqvist et al., 2011 ). Therefore, although it is not unlikely for RCTs to be used in order to generate practice-informed evidence (Horn & Gassaway, 2007 ), qualitative methods like the systematic case study are seen as ideal for demonstrating the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions with individual patients (van Hennik, 2020 ) (Table 4 ).

PBE’s epistemological approach to ‘evidence’ may be understood through the process of concordant objectivity (Douglas, 2004 ): ‘Instead of seeking to eliminate individual judgment, … [concordant objectivity] checks to see whether the individual judgments of people in fact do agree’ (p. 462). This does not mean that anyone can contribute to the evaluation process like in procedural objectivity, where the main criterion is following a set quantitative protocol or knowing how to operate a specific research design. Concordant objectivity requires that there is a set of competent observers who are closely familiar with the studied phenomenon (e.g. researchers and practitioners who are familiar with depression from a variety of therapeutic approaches).

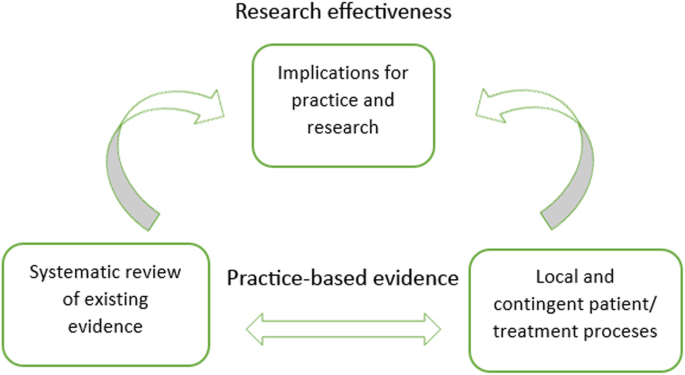

Systematic case studies are a good example of PBE ‘in action’: they allow for the examination of detailed unfolding of events in psychotherapy practice, making it the most pragmatic and practice-oriented form of psychotherapy research (Fishman, 1999 , 2005 ). Furthermore, systematic case studies approach evidence and results through concordant objectivity (Douglas, 2004 ) by involving a team of researchers and rigorous data triangulation processes (McLeod, 2010 ). This means that, although systematic case studies remain focused on particular clinical situations and detailed subjective experiences (similar to classic clinical case studies; see Iwakabe & Gazzola, 2009 ), they still involve a series of validity checks and considerations on how findings from a single systematic case pertain to broader psychotherapy research (Fishman, 2005 ). The typical process of knowledge generation (through employing systematic case studies and concordant objectivity) in PBE is demonstrated in Fig. 3 . The figure exemplifies a bidirectional approach to research and practice, which includes the development of research-supported psychological treatments (through systematic reviews of existing evidence) as well as the perspectives of clinical practitioners in the research process (through the study of local and contingent patient and/or treatment processes) (Teachman et al., 2012 ; Westen, Novotny, & Thompson-Brenner, 2004 ).

Typical knowledge generation process in practice-based evidence (PBE)

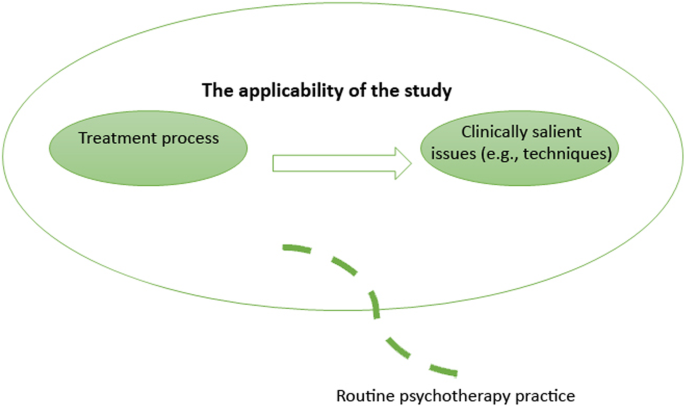

From a PBE standpoint, external validity is a desirable research condition: it measures extent to which the impact of interventions apply to real patients and therapists in everyday clinical settings. As such, external validity is not based on the strength of causal relationships between treatment interventions and outcomes (as in internal validity); instead, the use of specific therapeutic techniques and problem-solving decisions are considered to be important for generalising findings onto routine clinical practice (even if the findings are explicated from a single case study; see Aveline, 2005 ). This approach to validity is demonstrated in Fig. 4 .

External validity

Since effectiveness research is less focused on limiting the context of the studied phenomenon (indeed, explicating the context is often one of the research aims), there is more potential for confounding factors (e.g. bias and uncontrolled variables) which in turn can reduce the study’s internal validity (Barkham & Mellor-Clark, 2003 ). This is also an important challenge for research appraisal. Douglas ( 2004 ) argues that appraising research in terms of its effectiveness may produce significant disagreements or group illusions, since what might work for some practitioners may not work for others: ‘It cannot guarantee that values are not influencing or supplanting reasoning; the observers may have shared values that cause them to all disregard important aspects of an event’ (Douglas, 2004 , p. 462). Douglas further proposes that an interactive approach to objectivity may be employed as a more complex process in debating the evidential quality of a research study: it requires a discussion among observers and evaluators in the form of peer-review, scientific discourse, as well as research appraisal tools and instruments. While these processes of rigour are also applied in EBP, there appears to be much more space for debate, disagreement and interpretation in PBE’s approach to research evaluation, partly because the evaluation criteria themselves are subject of methodological debate and are often employed in different ways by researchers (Williams et al., 2019 ). This issue will be addressed more explicitly again in relation to CaSE development (‘Developing purpose-oriented evaluation criteria for systematic case studies’ section).

A third way approach to validity and evidence

The research–practice divide shows us that there may be something significant in establishing complementarity between EBP and PBE rather than treating them as mutually exclusive forms of research (Fishman et al., 2017 ). For one, EBP is not a sufficient condition for delivering research relevant to practice settings (Bower, 2003 ). While RCTs can demonstrate that an intervention works on average in a group, clinicians who are facing individual patients need to answer a different question: how can I make therapy work with this particular case ? (Cartwright & Hardie, 2012 ). Systematic case studies are ideal for filling this gap: they contain descriptions of microprocesses (e.g. patient symptoms, therapeutic relationships, therapist attitudes) in psychotherapy practice that are often overlooked in large-scale RCTs (Iwakabe & Gazzola, 2009 ). In particular, systematic case studies describing the use of specific interventions with less researched psychological conditions (e.g. childhood depression or complex post-traumatic stress disorder) can deepen practitioners’ understanding of effective clinical techniques before the results of large-scale outcome studies are disseminated.

Secondly, establishing a working relationship between systematic case studies and RCTs will contribute towards a more pragmatic understanding of validity in psychotherapy research. Indeed, the very tension and so-called trade-off between internal and external validity is based on the assumption that research methods are designed on an either/or basis; either they provide a sufficiently rigorous study design or they produce findings that can be applied to real-life practice. Jimenez-Buedo and Miller ( 2010 ) call this assumption into question: in their view, if a study is not internally valid, then ‘little, or rather nothing, can be said of the outside world’ (p. 302). In this sense, internal validity may be seen as a pre-requisite for any form of applied research and its external validity, but it need not be constrained to the quantitative approach of causality. For example, Levitt, Motulsky, Wertz, Morrow, and Ponterotto ( 2017 ) argue that, what is typically conceptualised as internal validity, is, in fact, a much broader construct, involving the assessment of how the research method (whether qualitative or quantitative) is best suited for the research goal, and whether it obtains the relevant conclusions. Similarly, Truijens, Cornelis, Desmet, and De Smet ( 2019 ) suggest that we should think about validity in a broader epistemic sense—not just in terms of psychometric measures, but also in terms of the research design, procedure, goals (research questions), approaches to inquiry (paradigms, epistemological assumptions), etc.

The overarching argument from research cited above is that all forms of research—qualitative and quantitative—can produce ‘valid evidence’ but the validity itself needs to be assessed against each specific research method and purpose. For example, RCTs are accompanied with a variety of clearly outlined appraisal tools and instruments such as CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme) that are well suited for the assessment of RCT validity and their implications for EBP. Systematic case studies (or case studies more generally) currently have no appraisal tools in any discipline. The next section evaluates whether existing qualitative research appraisal tools are relevant for systematic case studies in psychotherapy and specifies the missing evaluative criteria.

The relevance of existing appraisal tools for qualitative research to systematic case studies in psychotherapy

What is a research tool.

Currently, there are several research appraisal tools, checklists and frameworks for qualitative studies. It is important to note that tools, checklists and frameworks are not equivalent to one another but actually refer to different approaches to appraising the validity of a research study. As such, it is erroneous to assume that all forms of qualitative appraisal feature the same aims and methods (Hannes et al., 2010 ; Williams et al., 2019 ).

Generally, research assessment falls into two categories: checklists and frameworks . Checklist approaches are often contrasted with quantitative research, since the focus is on assessing the internal validity of research (i.e. researcher’s independence from the study). This involves the assessment of bias in sampling, participant recruitment, data collection and analysis. Framework approaches to research appraisal, on the other hand, revolve around traditional qualitative concepts such as transparency, reflexivity, dependability and transferability (Williams et al., 2019 ). Framework approaches to appraisal are often challenging to use because they depend on the reviewer’s familiarisation and interpretation of the qualitative concepts.

Because of these different approaches, there is some ambiguity in terminology, particularly between research appraisal instruments and research appraisal tools . These terms are often used interchangeably in appraisal literature (Williams et al., 2019 ). In this paper, research appraisal tool is defined as a method-specific (i.e. it identifies a specific research method or component) form of appraisal that draws from both checklist and framework approaches. Furthermore, a research appraisal tool seeks to inform decision making in EBP or PBE paradigms and provides explicit definitions of the tool’s evaluative framework (thus minimising—but by no means eliminating—the reviewers’ interpretation of the tool). This definition will be applied to CaSE (Table 5 ).

In contrast, research appraisal instruments are generally seen as a broader form of appraisal in the sense that they may evaluate a variety of methods (i.e. they are non-method specific or they do not target a particular research component), and are aimed at checking whether the research findings and/or the study design contain specific elements (e.g. the aims of research, the rationale behind design methodology, participant recruitment strategies, etc.).

There is often an implicit difference in audience between appraisal tools and instruments. Research appraisal instruments are often aimed at researchers who want to assess the strength of their study; however, the process of appraisal may not be made explicit in the study itself (besides mentioning that the tool was used to appraise the study). Research appraisal tools are aimed at researchers who wish to explicitly demonstrate the evidential quality of the study to the readers (which is particularly common in RCTs). All forms of appraisal used in the comparative exercise below are defined as ‘tools’, even though they have different appraisal approaches and aims.

Comparing different qualitative tools

Hannes et al. ( 2010 ) identified CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme-tool), JBI (Joanna Briggs Institute-tool) and ETQS (Evaluation Tool for Qualitative Studies) as the most frequently used critical appraisal tools by qualitative researchers. All three instruments are available online and are free of charge, which means that any researcher or reviewer can readily utilise CASP, JBI or ETQS evaluative frameworks to their research. Furthermore, all three instruments were developed within the context of organisational, institutional or consortium support (Tables 6 , 7 and 8 ).

It is important to note that neither of the three tools is specific to systematic case studies or psychotherapy case studies (which would include not only systematic but also experimental and clinical cases). This means that using CASP, JBI or ETQS for case study appraisal may come at a cost of overlooking elements and components specific to the systematic case study method.

Based on Hannes et al. ( 2010 ) comparative study of qualitative appraisal tools as well as the different evaluation criteria explicated in CASP, JBI and ETQS evaluative frameworks, I assessed how well each of the three tools is attuned to the methodological , clinical and theoretical aspects of systematic case studies in psychotherapy. The latter components were based on case study guidelines featured in the journal of Pragmatic Case Studies in Psychotherapy as well as components commonly used by published systematic case studies across a variety of other psychotherapy journals (e.g. Psychotherapy Research , Research In Psychotherapy : Psychopathology Process And Outcome , etc.) (see Table 9 for detailed descriptions of each component).

The evaluation criteria for each tool in Table 9 follows Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) ( 2017a , 2017b ); Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) ( 2018 ); and ETQS Questionnaire (first published in 2004 but revised continuously since). Table 10 demonstrates how each tool should be used (i.e. recommended reviewer responses to checklists and questionnaires).

Using CASP, JBI and ETQS for systematic case study appraisal

Although JBI, CASP and ETQS were all developed to appraise qualitative research, it is evident from the above comparison that there are significant differences between the three tools. For example, JBI and ETQS are well suited to assess researcher’s interpretations (Hannes et al. ( 2010 ) defined this as interpretive validity , a subcategory of internal validity ): the researcher’s ability to portray, understand and reflect on the research participants’ experiences, thoughts, viewpoints and intentions. JBI has an explicit requirement for participant voices to be clearly represented, whereas ETQS involves a set of questions about key characteristics of events, persons, times and settings that are relevant to the study. Furthermore, both JBI and ETQS seek to assess the researcher’s influence on the research, with ETQS particularly focusing on the evaluation of reflexivity (the researcher’s personal influence on the interpretation and collection of data). These elements are absent or addressed to a lesser extent in the CASP tool.

The appraisal of transferability of findings (what this paper previously referred to as external validity ) is addressed only by ETQS and CASP. Both tools have detailed questions about the value of research to practice and policy as well as its transferability to other populations and settings. Methodological research aspects are also extensively addressed by CASP and ETQS, but less so by JBI (which relies predominantly on congruity between research methodology and objectives without any particular assessment criteria for other data sources and/or data collection methods). Finally, the evaluation of theoretical aspects (referred to by Hannes et al. ( 2010 ) as theoretical validity ) is addressed only by JBI and ETQS; there are no assessment criteria for theoretical framework in CASP.

Given these differences, it is unsurprising that CASP, JBI and ETQS have limited relevance for systematic case studies in psychotherapy. First, it is evident that neither of the three tools has specific evaluative criteria for the clinical component of systematic case studies. Although JBI and ETQS feature some relevant questions about participants and their context, the conceptualisation of patients (and/or clients) in psychotherapy involves other kinds of data elements (e.g. diagnostic tools and questionnaires as well as therapist observations) that go beyond the usual participant data. Furthermore, much of the clinical data is intertwined with the therapist’s clinical decision-making and thinking style (Kaluzeviciute & Willemsen, 2020 ). As such, there is a need to appraise patient data and therapist interpretations not only on a separate basis, but also as two forms of knowledge that are deeply intertwined in the case narrative.

Secondly, since systematic case studies involve various forms of data, there is a need to appraise how these data converge (or how different methods complement one another in the case context) and how they can be transferred or applied in broader psychotherapy research and practice. These systematic case study components are attended to a degree by CASP (which is particularly attentive of methodological components) and ETQS (particularly specific criteria for research transferability onto policy and practice). These components are not addressed or less explicitly addressed by JBI. Overall, neither of the tools is attuned to all methodological, theoretical and clinical components of the systematic case study. Specifically, there are no clear evaluation criteria for the description of research teams (i.e. different data analysts and/or clinicians); the suitability of the systematic case study method; the description of patient’s clinical assessment; the use of other methods or data sources; the general data about therapeutic progress.

Finally, there is something to be said about the recommended reviewer responses (Table 10 ). Systematic case studies can vary significantly in their formulation and purpose. The methodological, theoretical and clinical components outlined in Table 9 follow guidelines made by case study journals; however, these are recommendations, not ‘set in stone’ case templates. For this reason, the straightforward checklist approaches adopted by JBI and CASP may be difficult to use for case study researchers and those reviewing case study research. The ETQS open-ended questionnaire approach suggested by Long and Godfrey ( 2004 ) enables a comprehensive, detailed and purpose-oriented assessment, suitable for the evaluation of systematic case studies. That said, there remains a challenge of ensuring that there is less space for the interpretation of evaluative criteria (Williams et al., 2019 ). The combination of checklist and framework approaches would, therefore, provide a more stable appraisal process across different reviewers.

Developing purpose-oriented evaluation criteria for systematic case studies

The starting point in developing evaluation criteria for Case Study Evaluation-tool (CaSE) is addressing the significance of pluralism in systematic case studies. Unlike RCTs, systematic case studies are pluralistic in the sense that they employ divergent practices in methodological procedures ( research process ), and they may include significantly different research aims and purpose ( the end - goal ) (Kaluzeviciute & Willemsen, 2020 ). While some systematic case studies will have an explicit intention to conceptualise and situate a single patient’s experiences and symptoms within a broader clinical population, others will focus on the exploration of phenomena as they emerge from the data. It is therefore important that CaSE is positioned within a purpose - oriented evaluative framework , suitable for the assessment of what each systematic case is good for (rather than determining an absolute measure of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ systematic case studies). This approach to evidence and appraisal is in line with the PBE paradigm. PBE emphasises the study of clinical complexities and variations through local and contingent settings (e.g. single case studies) and promotes methodological pluralism (Barkham & Mellor-Clark, 2003 ).

CaSE checklist for essential components in systematic case studies

In order to conceptualise purpose-oriented appraisal questions, we must first look at what unites and differentiates systematic case studies in psychotherapy. The commonly used theoretical, clinical and methodological systematic case study components were identified earlier in Table 9 . These components will be seen as essential and common to most systematic case studies in CaSE evaluative criteria. If these essential components are missing in a systematic case study, then it may be implied there is a lack of information, which in turn diminishes the evidential quality of the case. As such, the checklist serves as a tool for checking whether a case study is, indeed, systematic (as opposed to experimental or clinical; see Iwakabe & Gazzola, 2009 for further differentiation between methodologically distinct case study types) and should be used before CaSE Purpose - based Evaluative Framework for Systematic Case Studie s (which is designed for the appraisal of different purposes common to systematic case studies).

As noted earlier in the paper, checklist approaches to appraisal are useful when evaluating the presence or absence of specific information in a research study. This approach can be used to appraise essential components in systematic case studies, as shown below. From a pragmatic point view (Levitt et al., 2017 ; Truijens et al., 2019 ), CaSE Checklist for Essential Components in Systematic Case Studies can be seen as a way to ensure the internal validity of systematic case study: the reviewer is assessing whether sufficient information is provided about the case design, procedure, approaches to inquiry, etc., and whether they are relevant to the researcher’s objectives and conclusions (Table 11 ).

CaSE purpose-based evaluative framework for systematic case studies

Identifying differences between systematic case studies means identifying the different purposes systematic case studies have in psychotherapy. Based on the earlier work by social scientist Yin ( 1984 , 1993 ), we can differentiate between exploratory (hypothesis generating, indicating a beginning phase of research), descriptive (particularising case data as it emerges) and representative (a case that is typical of a broader clinical population, referred to as the ‘explanatory case’ by Yin) cases.

Another increasingly significant strand of systematic case studies is transferable (aggregating and transferring case study findings) cases. These cases are based on the process of meta-synthesis (Iwakabe & Gazzola, 2009 ): by examining processes and outcomes in many different case studies dealing with similar clinical issues, researchers can identify common themes and inferences. In this way, single case studies that have relatively little impact on clinical practice, research or health care policy (in the sense that they capture psychotherapy processes rather than produce generalisable claims as in Yin’s representative case studies) can contribute to the generation of a wider knowledge base in psychotherapy (Iwakabe, 2003 , 2005 ). However, there is an ongoing issue of assessing the evidential quality of such transferable cases. According to Duncan and Sparks ( 2020 ), although meta-synthesis and meta-analysis are considered to be ‘gold standard’ for assessing interventions across disparate studies in psychotherapy, they often contain case studies with significant research limitations, inappropriate interpretations and insufficient information. It is therefore important to have a research appraisal process in place for selecting transferable case studies.