Conceptual review papers: revisiting existing research to develop and refine theory

- Theory/Conceptual

- Published: 29 April 2020

- Volume 10 , pages 27–35, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- John Hulland 1

5658 Accesses

56 Citations

8 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Conceptual review papers can theoretically enrich the field of marketing by reviewing extant knowledge, noting tensions and inconsistencies, identifying important gaps as well as key insights, and proposing agendas for future research. The result of this process is a theoretical contribution that refines, reconceptualizes, or even replaces existing ways of viewing a phenomenon. This paper spells out the primary aims of conceptual reviews and clarifies how they differ from other theory development efforts. It also describes elements essential to a strong conceptual review paper and offers a specific set of best practices that can be used to distinguish a strong conceptual review from a weak one.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Meta-analysis: integrating accumulated knowledge.

Dhruv Grewal, Nancy Puccinelli & Kent B. Monroe

Designing conceptual articles: four approaches

Elina Jaakkola

Contours of the marketing literature: Text, context, point-of-view, research horizons, interpretation, and influence in marketing

Terry Clark, Thomas Martin Key & Carol Azab

Palmatier et al. ( 2018 ) reference a study of the frequency with which review papers were published in top marketing journals during the 2012–2016 period. Focusing on the top six journals included in the Financial Times (( FT-50 ) journal list, the study found that “ JAMS has become the most common outlet … publishing 31% of all review papers that appeared in the top six marketing journals.”

The bifurcation here between theory development “from scratch” versus through conceptual review is potentially somewhat misleading, since the latter can also result in novel theoretical insights. Furthermore, many conceptual papers make significant theoretical contributions by building on existing theory without themselves being review papers. Nonetheless, conceptual reviews necessarily involve working with extant, published work.

This focus is quite distinct from the approach proposed by Zeithaml et al. ( 2020 ). Their emphasis is on “an approach that is ideally suited to the development of theories in marketing: the ‘theories-in-use’ (TIU) approach” (p. 32). They propose it as an alternative inductive methodology (vs. case studies and ethnographies) to developing grounded theory.

These elements are drawn from Hulland & Houston ( 2020 ), MacInnis ( 2011 ), Palmatier et al. ( 2018 ), and Yadav ( 2010 ). Houston ( 2020 ), MacInnis ( 2011 ), Palmatier, Houston & Hulland et al. ( 2018 ), and Yadav ( 2010 ).

These underlying assumptions are a crucial component in developing strong arguments for theory development (Toulmin 1958 ).

MacInnis ( 2011 ) describes eight critical skills for conceptual thinking that are arrayed across four dimensions: envisioning (identifying vs. revising), explicating (delineating vs. summarizing), relating (differentiating vs. integrating, and debating (advocating vs. refuting). For conceptual review papers, summarizing and revising represent critical skills that need to be harnessed by the author (whereas identifying and delineating are skills more critical to uncovering new ideas). For the other two dimensions (relating and debating), a more balanced use of the associated skills is needed (i.e., both differentiating and integrating are important, and both advocating and refuting are important).

In her paper, Jaakkola ( 2020 ) describes four different types of research designs for conceptual reviews: (1) theory synthesis, (2) theory adaptation, (3) typology, and (4) model. In the current paper, elements from all four of these types are discussed.

In doing so, Khamitov et al. discover seven overarching insights that reveal gaps in the interfaces between the three streams. This highlighting of gaps represents stage four in the theory refinement process.

Not all of the gaps in a specific domain are necessarily valuable, however. Just because no one has studied a phenomenon in a particular industry or region, or with a particular method does not mean that a filling of that gap is required (or even valued).

Antonakis, J., Bartardox, N., Liu, Y., & Schriesheim, C. A. (2014). What makes articles highly cited? The Leadership Quarterly, 25 (1), 152–179.

Article Google Scholar

Barczak, G. (2017). From the editor: Writing a review article. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 34 (2), 120–121.

Bem, D.J. (1995). Writing a review article for Psychological Bulletin . Psychological Bulletin , 118(2), 172–177.

Bettencourt, L. A., & Houston, M. B. (2001). Assessing the impact of article method type and subject area on citation frequency and reference diversity. Marketing Letters, 12 (4), 327–340.

Dekimpe, M. G., & Deleersnyder, B. (2018). Business cycle research in marketing: A review and research agenda. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 46 (1), 31–58.

Dowling, K., Guhl, D., Klapper, D., Spann, M., Stich, L., & Yegoryan, N. (2020). Behavioral biases in marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science in press , 48 (3), 449–477.

Gilson, L. L., & Goldberg, C. B. (2015). Editors’ comment: So, what is a conceptual paper? Group & Organization Management, 40 (2), 127–130.

Grewal, D., Puccinelli, N. M., & Monroe, K. B. (2018). Meta-analysis: Integrating accumulated knowledge. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 46 (1), 9–30.

Houston, M. B. (2019). Four facets of rigor. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 47 (4), 570–573.

Hulland, J., & Houston, M. B. (2020). Why systematic review papers and meta-analyses matter: An introduction to the special issue on generalizations in marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 48 (3) in press, 351–359.

Hulland, J., Baumgartner, H., & Smith, K. M. (2018). Marketing survey research best practices: Evidence and recommendations from a review of JAMS articles. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 46 (1), 92–108.

Jaakkola, E. (2020). Designing conceptual articles: Four approaches. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science in press.

Khamitov, M., Gregoire, Y., & Suri, A. (2020). A systematic review of brand transgression, service failure recovery and product-harm crisis: Integration and guiding insights. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science in press , 48 (3), 519–542.

Kozlenkova, I. V., Samaha, S. A., & Palmatier, R. W. (2014). Resource-based theory in marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 42 (1), 1–21.

Lamberton, C., & Stephen, A. T. (2016). A thematic exploration of digital, social media, and mobile marketing: Research evolution from 2000 to 2015 and an agenda for future inquiry. Journal of Marketing, 80 (November), 146–172.

Littell, J. H., Corcoran, J., & Pillai, V. (2008). Systematic reviews and meta-analysis . New York: Oxford University Press.

MacInnis, D. J. (2011). A framework for conceptual contributions in marketing. Journal of Marketing, 75 (July), 136–154.

Palmatier, R. W. (2016). Improving publishing success at JAMS : Contribution and positioning. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44 (6), 655–659.

Palmatier, R. W., Houston, M. B., & Hulland, J. (2018). Review articles: Purpose, process, and structure. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 46 (1), 1–5.

Rindfleisch, A., & Heide, J. B. (1997). Transaction cost analysis: Past, present, and future applications. Journal of Marketing, 61 (4), 30–54.

Rosario, A. B., de Valck, K., & Sotgiu, F. (2020). Conceptualizing the electronic word-of-mouth process: What we know and need to know about eWOM creation, exposure, and evaluation. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science in press.

Samiee, S. (1994). Customer evaluation of products in a global market. Journal of International Business Studies, 25 (3), 579–604.

Sample, K. L., Hagtvedt, H., & Brasel, S. A. (2020). Components of visual perception in marketing contexts: A conceptual framework and review. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science in press , 48 (3), 405–421.

Short, J. (2009). The art of writing a review article. Journal of Management, 35 (6), 1312–1317.

Sorescu, A., Warren, N. L., & Ertekin, L. (2017). Event study methodology in the marketing literature: An overview. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45 (2), 186–207.

Steinhoff, L., Arli, D., Weaven, S., & Kozlenkova, I. V. (2019). Online relationship marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 47 (3), 369–393.

Stewart, D. W., & Zinkhan, G. M. (2006). Enhancing marketing theory in academic research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 34 (Fall), 477–480.

Sutton, R. I., & Staw, B. M. (1995). What theory is not . Administrative Science Quarterly, 40 (3), 371–384.

Toulmin, S. (1958). The uses of argument . Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

Google Scholar

Wade, M., & Hulland, J. (2004). The resource-based view and information systems research: Review, extension, and suggestions for future research. MIS Quarterly, 28 (1), 107–142.

Yadav, M. S. (2010). The decline of conceptual articles and implications for knowledge development. Journal of Marketing, 74 (January), 1–19.

Zeithaml, V. A., Jaworski, B. J., Kohli, A. K., Tuli, K. R., Ulaga, W., & Zaltman, G. (2020). A theories-in-use approach to building marketing theory. Journal of Marketing, 84 (1), 32–51.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Terry College of Business, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, 30602, USA

John Hulland

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to John Hulland .

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Hulland, J. Conceptual review papers: revisiting existing research to develop and refine theory. AMS Rev 10 , 27–35 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13162-020-00168-7

Download citation

Received : 11 March 2020

Accepted : 01 April 2020

Published : 29 April 2020

Issue Date : June 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13162-020-00168-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Conceptual review papers

- Marketing theory

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- What Is a Conceptual Framework? | Tips & Examples

What Is a Conceptual Framework? | Tips & Examples

Published on August 2, 2022 by Bas Swaen and Tegan George. Revised on March 18, 2024.

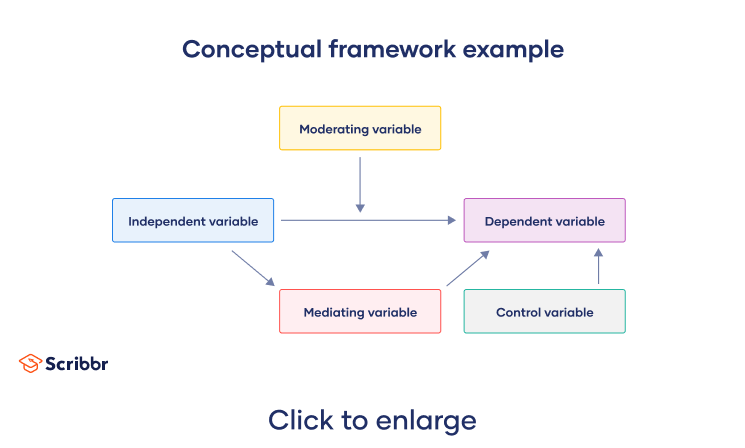

A conceptual framework illustrates the expected relationship between your variables. It defines the relevant objectives for your research process and maps out how they come together to draw coherent conclusions.

Keep reading for a step-by-step guide to help you construct your own conceptual framework.

Table of contents

Developing a conceptual framework in research, step 1: choose your research question, step 2: select your independent and dependent variables, step 3: visualize your cause-and-effect relationship, step 4: identify other influencing variables, frequently asked questions about conceptual models.

A conceptual framework is a representation of the relationship you expect to see between your variables, or the characteristics or properties that you want to study.

Conceptual frameworks can be written or visual and are generally developed based on a literature review of existing studies about your topic.

Your research question guides your work by determining exactly what you want to find out, giving your research process a clear focus.

However, before you start collecting your data, consider constructing a conceptual framework. This will help you map out which variables you will measure and how you expect them to relate to one another.

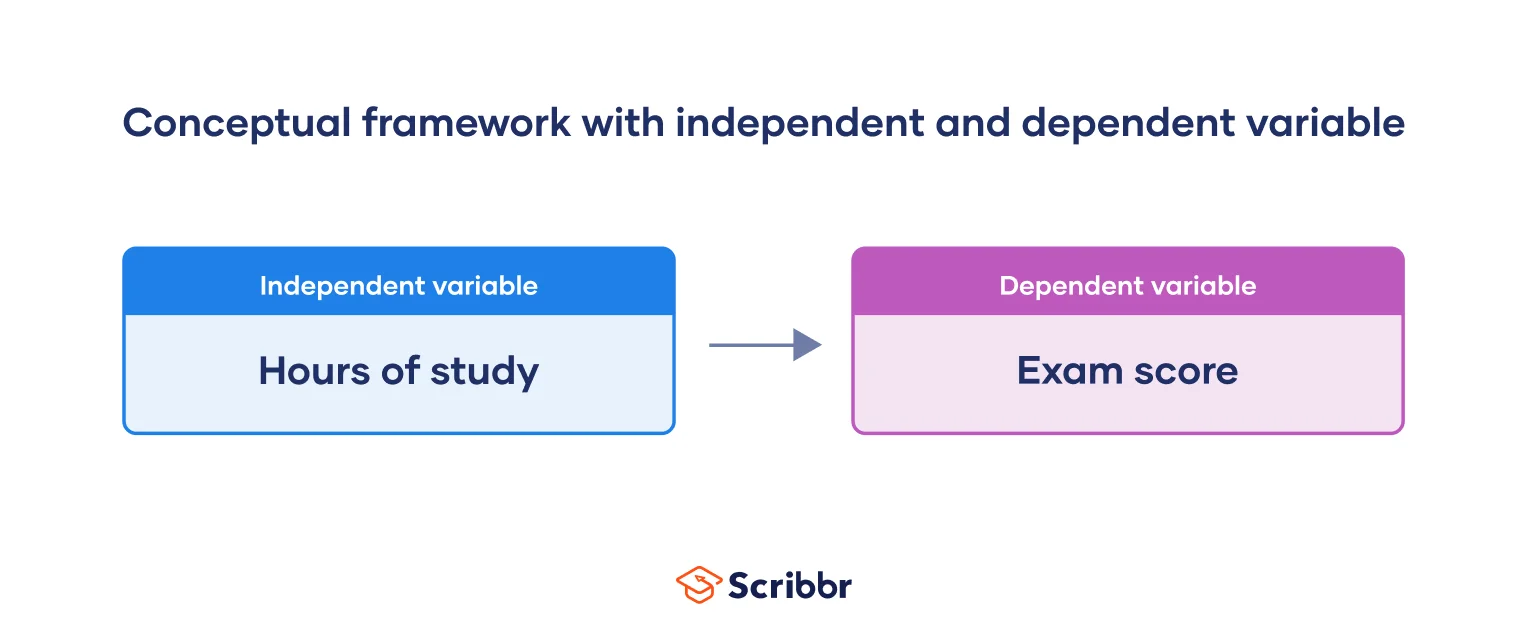

In order to move forward with your research question and test a cause-and-effect relationship, you must first identify at least two key variables: your independent and dependent variables .

- The expected cause, “hours of study,” is the independent variable (the predictor, or explanatory variable)

- The expected effect, “exam score,” is the dependent variable (the response, or outcome variable).

Note that causal relationships often involve several independent variables that affect the dependent variable. For the purpose of this example, we’ll work with just one independent variable (“hours of study”).

Now that you’ve figured out your research question and variables, the first step in designing your conceptual framework is visualizing your expected cause-and-effect relationship.

We demonstrate this using basic design components of boxes and arrows. Here, each variable appears in a box. To indicate a causal relationship, each arrow should start from the independent variable (the cause) and point to the dependent variable (the effect).

It’s crucial to identify other variables that can influence the relationship between your independent and dependent variables early in your research process.

Some common variables to include are moderating, mediating, and control variables.

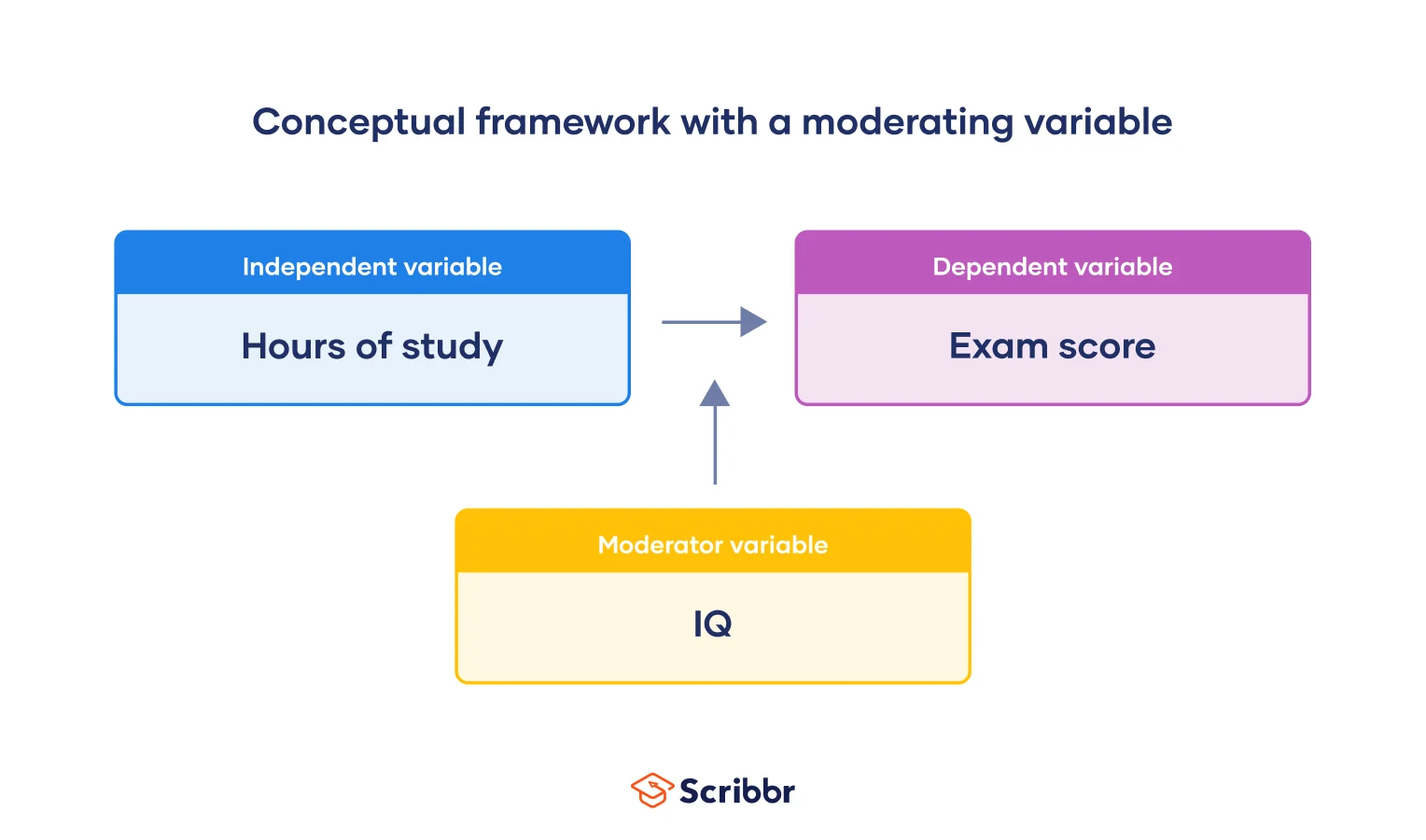

Moderating variables

Moderating variable (or moderators) alter the effect that an independent variable has on a dependent variable. In other words, moderators change the “effect” component of the cause-and-effect relationship.

Let’s add the moderator “IQ.” Here, a student’s IQ level can change the effect that the variable “hours of study” has on the exam score. The higher the IQ, the fewer hours of study are needed to do well on the exam.

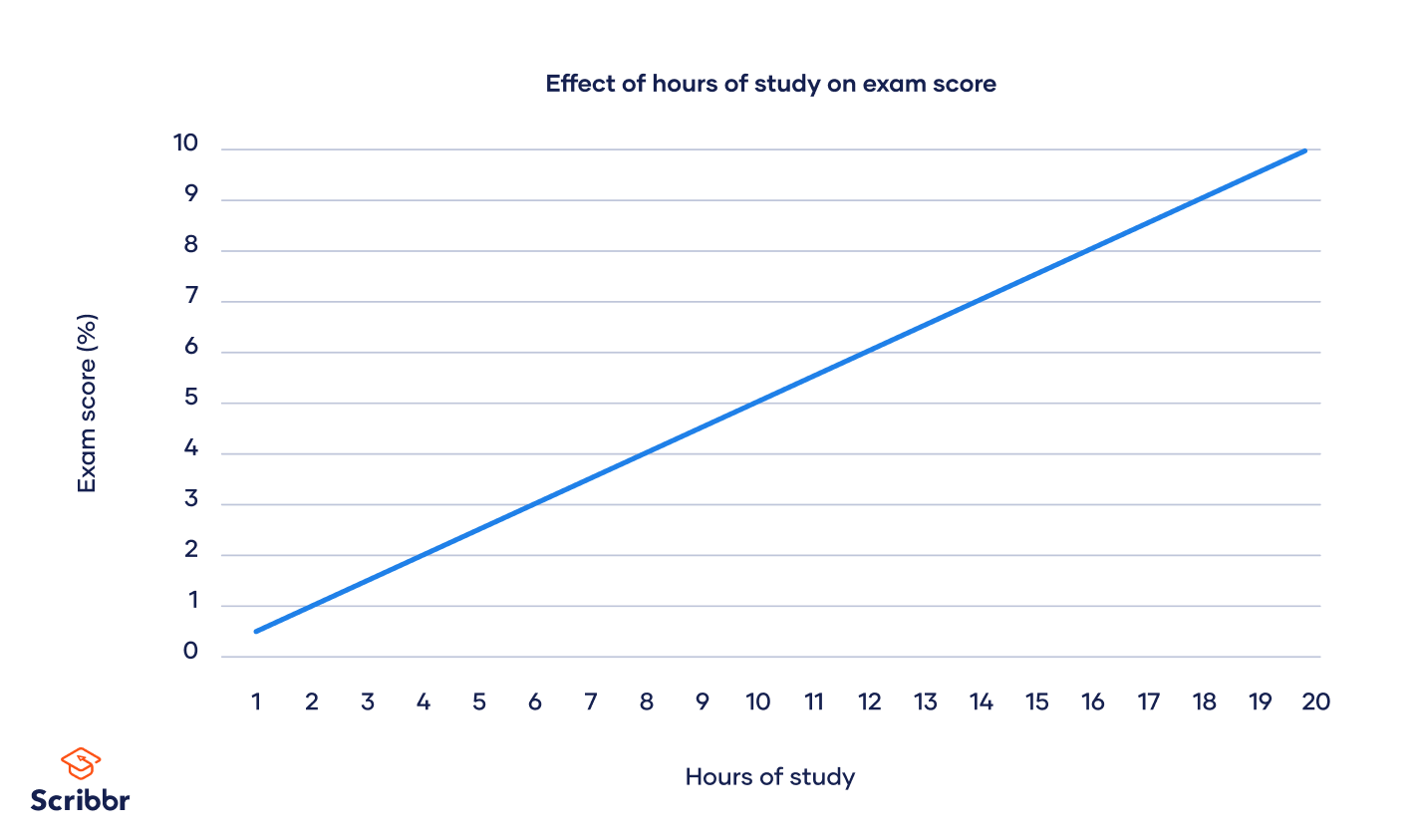

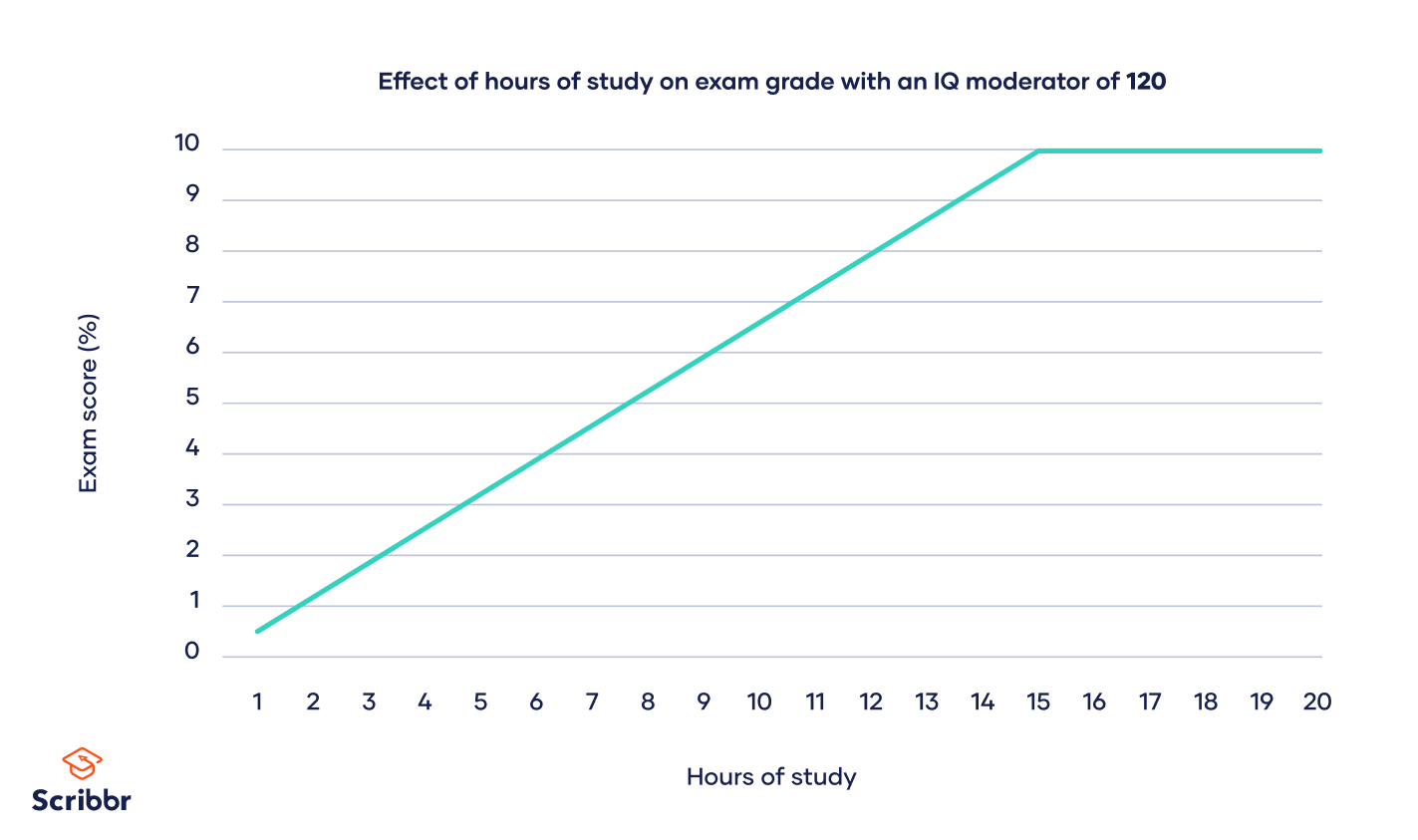

Let’s take a look at how this might work. The graph below shows how the number of hours spent studying affects exam score. As expected, the more hours you study, the better your results. Here, a student who studies for 20 hours will get a perfect score.

But the graph looks different when we add our “IQ” moderator of 120. A student with this IQ will achieve a perfect score after just 15 hours of study.

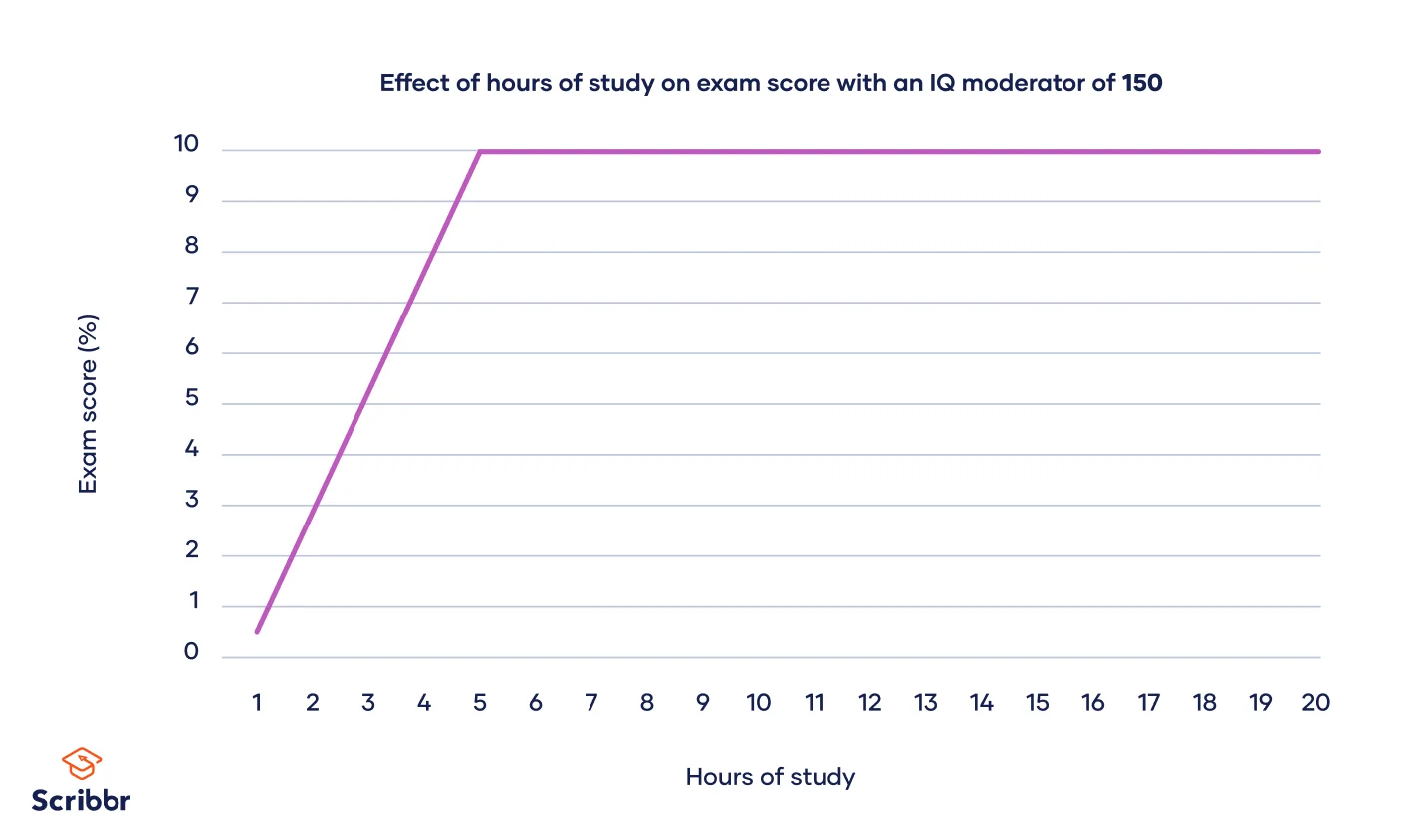

Below, the value of the “IQ” moderator has been increased to 150. A student with this IQ will only need to invest five hours of study in order to get a perfect score.

Here, we see that a moderating variable does indeed change the cause-and-effect relationship between two variables.

Mediating variables

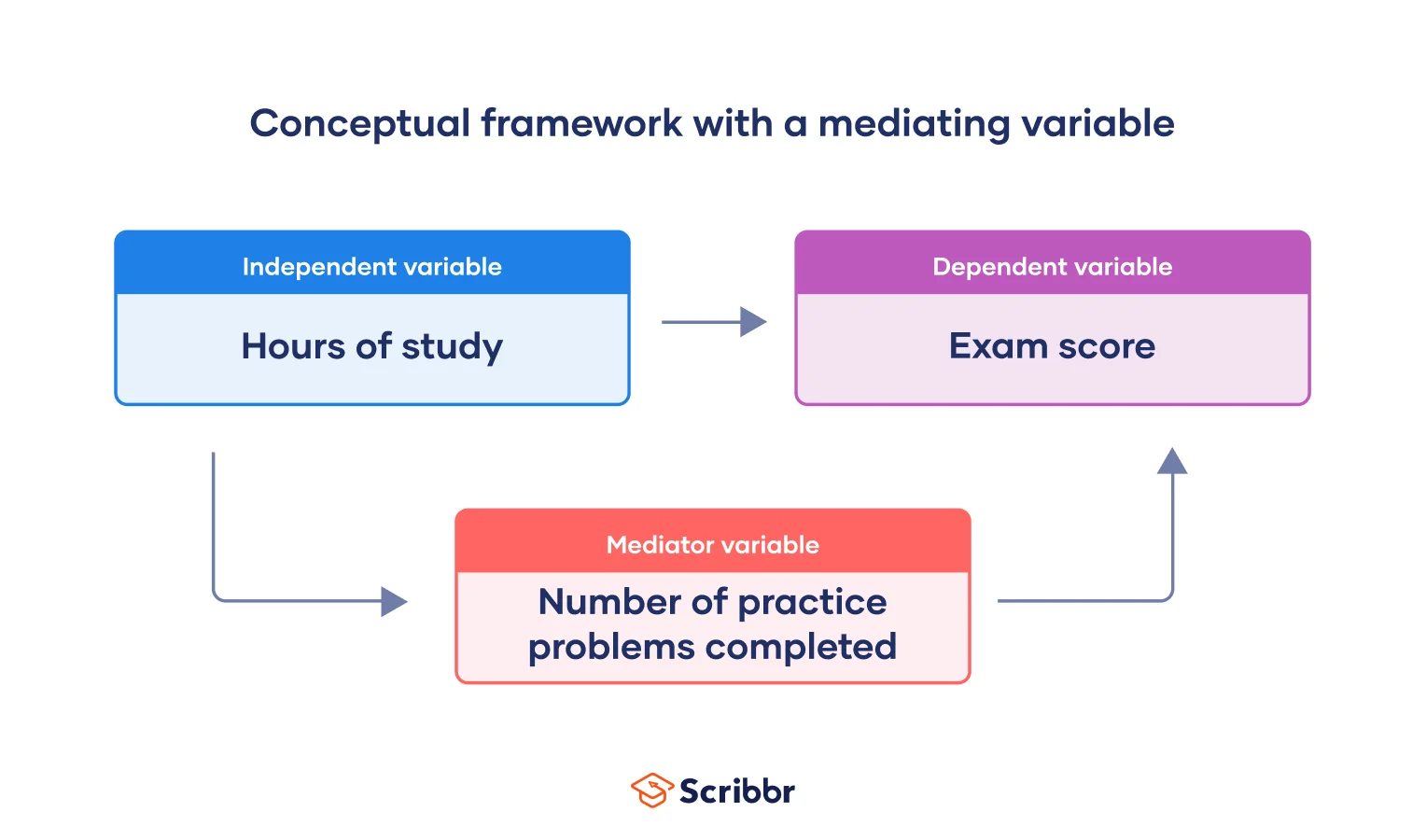

Now we’ll expand the framework by adding a mediating variable . Mediating variables link the independent and dependent variables, allowing the relationship between them to be better explained.

Here’s how the conceptual framework might look if a mediator variable were involved:

In this case, the mediator helps explain why studying more hours leads to a higher exam score. The more hours a student studies, the more practice problems they will complete; the more practice problems completed, the higher the student’s exam score will be.

Moderator vs. mediator

It’s important not to confuse moderating and mediating variables. To remember the difference, you can think of them in relation to the independent variable:

- A moderating variable is not affected by the independent variable, even though it affects the dependent variable. For example, no matter how many hours you study (the independent variable), your IQ will not get higher.

- A mediating variable is affected by the independent variable. In turn, it also affects the dependent variable. Therefore, it links the two variables and helps explain the relationship between them.

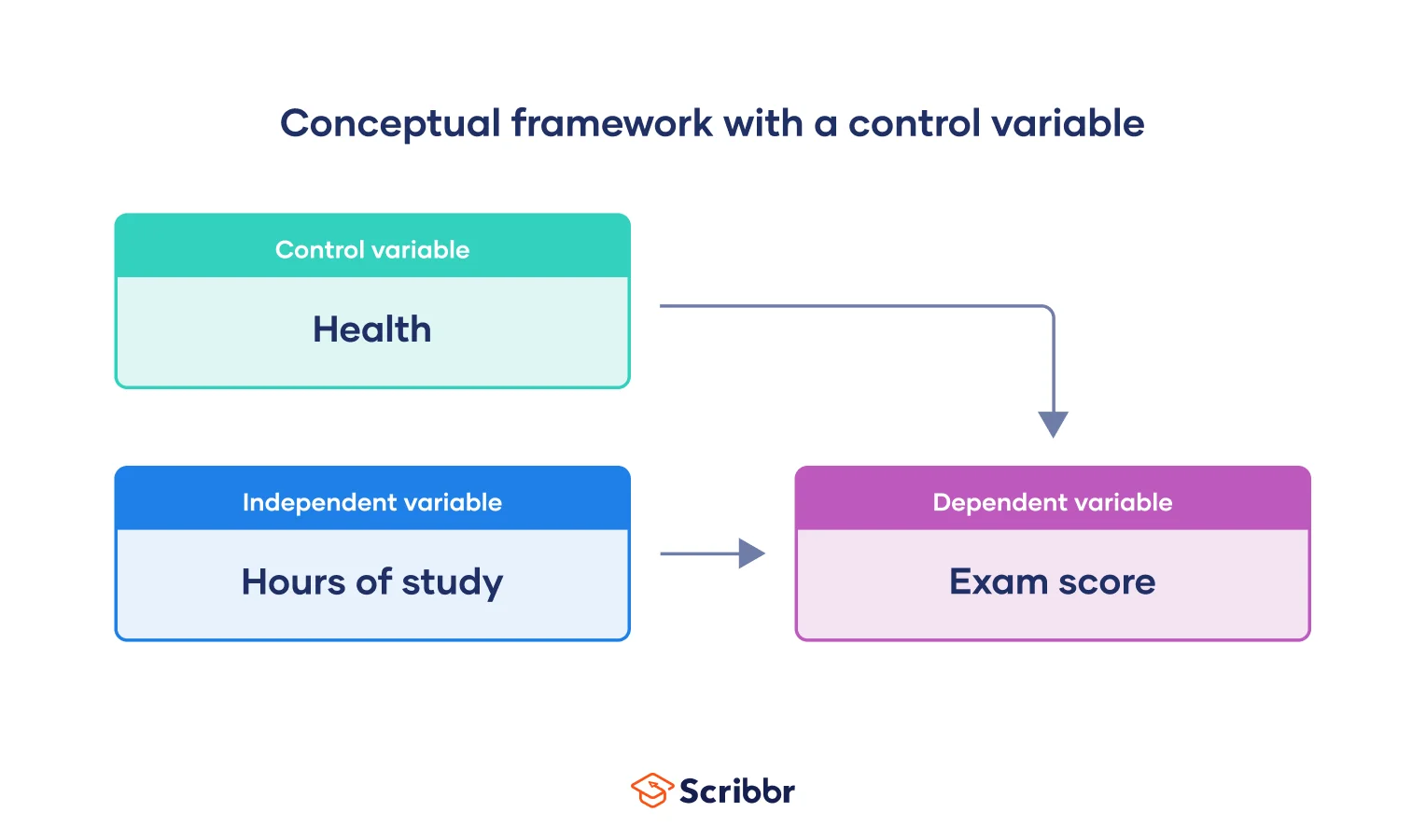

Control variables

Lastly, control variables must also be taken into account. These are variables that are held constant so that they don’t interfere with the results. Even though you aren’t interested in measuring them for your study, it’s crucial to be aware of as many of them as you can be.

A mediator variable explains the process through which two variables are related, while a moderator variable affects the strength and direction of that relationship.

A confounding variable is closely related to both the independent and dependent variables in a study. An independent variable represents the supposed cause , while the dependent variable is the supposed effect . A confounding variable is a third variable that influences both the independent and dependent variables.

Failing to account for confounding variables can cause you to wrongly estimate the relationship between your independent and dependent variables.

Yes, but including more than one of either type requires multiple research questions .

For example, if you are interested in the effect of a diet on health, you can use multiple measures of health: blood sugar, blood pressure, weight, pulse, and many more. Each of these is its own dependent variable with its own research question.

You could also choose to look at the effect of exercise levels as well as diet, or even the additional effect of the two combined. Each of these is a separate independent variable .

To ensure the internal validity of an experiment , you should only change one independent variable at a time.

A control variable is any variable that’s held constant in a research study. It’s not a variable of interest in the study, but it’s controlled because it could influence the outcomes.

A confounding variable , also called a confounder or confounding factor, is a third variable in a study examining a potential cause-and-effect relationship.

A confounding variable is related to both the supposed cause and the supposed effect of the study. It can be difficult to separate the true effect of the independent variable from the effect of the confounding variable.

In your research design , it’s important to identify potential confounding variables and plan how you will reduce their impact.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Swaen, B. & George, T. (2024, March 18). What Is a Conceptual Framework? | Tips & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 5, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/conceptual-framework/

Is this article helpful?

Other students also liked

Independent vs. dependent variables | definition & examples, mediator vs. moderator variables | differences & examples, control variables | what are they & why do they matter, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

COMMENTS

Abstract and Figures. This handout provides a detailed outline of how to write a conceptual academic paper for scholarly journal publication. It is based on my academic publishing experience and ...

CHAPTER 2 • ConCEPTuAl FRAmEwoRks in REsEARCH . 33. What Is a Conceptual Framework? Conceptual frameworks have historically been a somewhat confusing aspect of quali-tative research design. Relatively little has been written about them, and various terms, including . conceptual framework, theoretical framework, theory, idea context, logic ...

ples from high quality journals to identify and illustrate differ-ent options for conceptual research design. This paper dis-cusses four templates—Theory Synthesis, Theory Adaptation, Typology, and Model and explicates their aims, their approach to theory use, and their contribution potential.

For this reason, the conceptual framework of your study—the system of concepts, assumptions, expectations, beliefs, and theories that supports and informs your research—is a key part of your design (Miles & Huberman, 1994; Robson, 2011). Miles and Huberman (1994) defined a conceptual framework as a visual or written product,

View PDF View EPUB. The conceptual article can make a valuable contribution to the scholarly conversation but presents its own special challenges compared to the traditional article that reports empirical findings or interpretive analysis with a familiar organizational structure. This article provides a guide to this task, organized around the ...

The paper discusses four potential templates for conceptual papers - Theory Synthesis, Theory Adaptation, Typology, and Model - and their respective aims, approach for using theories, and contribution potential. Supported by illustrative examples, these templates codify some of the tacit knowledge that underpins the design of non-empirical ...

7 In her paper, Jaakkola (2020) describes four different types of research de-signs for conceptual reviews: (1) theory synthesis, (2) theory adaptation, (3) typology, and (4) model. In the current paper, elements from all four of these types are discussed.

The evolution of a research idea into a study design is useful for understanding the impact that developing a conceptual framework has on this work. Adding the academic structure required to go from idea to fully realized conceptual framework is integral to a sound study. Going into the

Current usage of the terms conceptual framework and theoretical framework are vague and imprecise. In this paper I define conceptual framework as a network, or "a plane," of interlinked concepts that together provide a comprehensive understanding of a phenomenon or phenomena. The concepts that constitute a conceptual framework support one another, articulate their respective phenomena, and ...

Research Methods 2. Conceptual Research design. • The modeling of the content of the research • Determines what, why and how much is going to be studied • 4 phases: • Objective of the research • Research framework • Research Question/Conceptual model • Definition & Operalisation. 2. Research Methods 3. Why do we need a context?

conceptual frameworks should be regarded as the mental map that connects the various dimensions of the research process such as the researcher's a priori knowledge and interests, the literature survey, theory, methods, data analysis and findings. In this regard, Maxwell (2005:33) defined a conceptual framework as 'the system of concepts,

to interest potential funders. to develop potential solutions or investigations into project ideas. to determine whether a project idea is fundable. to serve as the foundation of a full proposal. Funders that request concept papers often provide a template or format. If templates or formats are not provided, the following can serve as a useful ...

Conceptual review papers can theoretically enrich the field of marketing by reviewing extant knowledge, noting tensions and inconsistencies, identifying important gaps as well as key insights, and proposing agendas for future research. The result of this process is a theoretical contribution that refines, reconceptualizes, or even replaces existing ways of viewing a phenomenon. This paper ...

Developing a conceptual framework in research. Step 1: Choose your research question. Step 2: Select your independent and dependent variables. Step 3: Visualize your cause-and-effect relationship. Step 4: Identify other influencing variables. Frequently asked questions about conceptual models.

THEORETICAL AND CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORKS IN RESEARCH: CONCEPTUAL CLARIFICATION Section A-Research paper 2105 Eur. Chem. Bull. 2023,12(12), 2103-2117 the meanings of the data are self-rationalized (Neuman, 1997). It is the plan or research guideline (Grant & Osanloo, 2014).

Funders that request concept papers often provide a template or format. If templates or formats are not provided, the following can serve as a useful concept paper structure. THE FIVE ELEMENTS OF A CONCEPT PAPER 1. The first section, the Introduction, identifies how and where the applicant's mission and the funder's mission intersect or align.

This conceptual paper is delimited by insufficient readings of literatures from multi-discipline in order to get a broader scope of theoretical understanding. This conceptual paper too has its investigative limitations. For example, this paper is merely a review from other journals and the data is yet to be collected. Another limitation