Change Password

Your password must have 6 characters or more:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

Create your account

Forget yout password.

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password

Forgot your Username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

- March 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 3 CURRENT ISSUE pp.171-254

- February 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 2 pp.83-170

- January 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 1 pp.1-82

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has updated its Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , including with new information specifically addressed to individuals in the European Economic Area. As described in the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences.

Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

The Critical Relationship Between Anxiety and Depression

- Ned H. Kalin , M.D.

Search for more papers by this author

Anxiety and depressive disorders are among the most common psychiatric illnesses; they are highly comorbid with each other, and together they are considered to belong to the broader category of internalizing disorders. Based on statistics from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the 12-month prevalence of major depressive disorder in 2017 was estimated to be 7.1% for adults and 13.3% for adolescents ( 1 ). Data for anxiety disorders are less current, but in 2001–2003, their 12-month prevalence was estimated to be 19.1% in adults, and 2001–2004 data estimated that the lifetime prevalence in adolescents was 31.9% ( 2 , 3 ). Both anxiety and depressive disorders are more prevalent in women, with an approximate 2:1 ratio in women compared with men during women’s reproductive years ( 1 , 2 ).

Across all psychiatric disorders, comorbidity is the rule ( 4 ), which is definitely the case for anxiety and depressive disorders, as well as their symptoms. With respect to major depression, a worldwide survey reported that 45.7% of individuals with lifetime major depressive disorder had a lifetime history of one or more anxiety disorder ( 5 ). These disorders also commonly coexist during the same time frame, as 41.6% of individuals with 12-month major depression also had one or more anxiety disorder over the same 12-month period. From the perspective of anxiety disorders, the lifetime comorbidity with depression is estimated to range from 20% to 70% for patients with social anxiety disorder ( 6 ), 50% for patients with panic disorder ( 6 ), 48% for patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) ( 7 ), and 43% for patients with generalized anxiety disorder ( 8 ). Data from the well-known Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study demonstrate comorbidity at the symptom level, as 53% of the patients with major depression had significant anxiety and were considered to have an anxious depression ( 9 ).

Anxiety and depressive disorders are moderately heritable (approximately 40%), and evidence suggests shared genetic risk across the internalizing disorders ( 10 ). Among internalizing disorders, the highest level of shared genetic risk appears to be between major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder. Neuroticism is a personality trait or temperamental characteristic that is associated with the development of both anxiety and depression, and the genetic risk for developing neuroticism also appears to be shared with that of the internalizing disorders ( 11 ). Common nongenetic risk factors associated with the development of anxiety and depression include earlier life adversity, such as trauma or neglect, as well as parenting style and current stress exposure. At the level of neural circuits, alterations in prefrontal-limbic pathways that mediate emotion regulatory processes are common to anxiety and depressive disorders ( 12 , 13 ). These findings are consistent with meta-analyses that reveal shared structural and functional brain alterations across various psychiatric illnesses, including anxiety and major depression, in circuits involving emotion regulation ( 13 ), executive function ( 14 ), and cognitive control ( 15 ).

Anxiety disorders and major depression occur during development, with anxiety disorders commonly beginning during preadolescence and early adolescence and major depression tending to emerge during adolescence and early to mid-adulthood ( 16 – 18 ). In relation to the evolution of their comorbidity, studies demonstrate that anxiety disorders generally precede the presentation of major depressive disorder ( 17 ). A European community-based study revealed, beginning at age 15, the developmental relation between comorbid anxiety and major depression by specifically focusing on social phobia (based on DSM-IV criteria) and then asking the question regarding concurrent major depressive disorder ( 18 ). The findings revealed a 19% concurrent comorbidity between these disorders, and in 65% of the cases, social phobia preceded major depressive disorder by at least 2 years. In addition, initial presentation with social phobia was associated with a 5.7-fold increased risk of developing major depressive disorder. These associations between anxiety and depression can be traced back even earlier in life. For example, childhood behavioral inhibition in response to novelty or strangers, or an extreme anxious temperament, is associated with a three- to fourfold increase in the likelihood of developing social anxiety disorder, which in turn is associated with an increased risk to develop major depressive disorder and substance abuse ( 19 ).

It is important to emphasize that the presence of comor‐bid anxiety symptoms and disorders matters in relation to treatment. Across psychiatric disorders, the presence of significant anxiety symptoms generally predicts worse outcomes, and this has been well demonstrated for depression. In the STAR*D study, patients with anxious major depressive disorder were more likely to be severely depressed and to have more suicidal ideation ( 9 ). This is consistent with the study by Kessler and colleagues ( 5 ), in which patients with anxious major depressive disorder, compared with patients with nonanxious major depressive disorder, were found to have more severe role impairment and more suicidal ideation. Data from level 1 of the STAR*D study (citalopram treatment) nicely illustrate the impact of comorbid anxiety symptoms on treatment. Compared with patients with nonanxious major depressive disorder, those 53% of patients with an anxious depression were less likely to remit and also had a greater side effect burden ( 20 ). Other data examining patients with major depressive disorder and comorbid anxiety disorders support the greater difficulty and challenge in treating patients with these comorbidities ( 21 ).

This issue of the Journal presents new findings relevant to the issues discussed above in relation to understanding and treating anxiety and depressive disorders. Drs. Conor Liston and Timothy Spellman, from Weill Cornell Medicine, provide an overview for this issue ( 22 ) that is focused on understanding mechanisms at the neural circuit level that underlie the pathophysiology of depression. Their piece nicely integrates human neuroimaging studies with complementary data from animal models that allow for the manipulation of selective circuits to test hypotheses generated from the human data. Also included in this issue is a review of the data addressing the reemergence of the use of psychedelic drugs in psychiatry, particularly for the treatment of depression, anxiety, and PTSD ( 23 ). This timely piece, authored by Dr. Collin Reiff along with a subgroup from the APA Council of Research, provides the current state of evidence supporting the further exploration of these interventions. Dr. Alan Schatzberg, from Stanford University, contributes an editorial in which he comments on where the field is in relation to clinical trials with psychedelics and to some of the difficulties, such as adequate blinding, in reliably studying the efficacy of these drugs ( 24 ).

In an article by McTeague et al. ( 25 ), the authors use meta-analytic strategies to understand the neural alterations that are related to aberrant emotion processing that are shared across psychiatric disorders. Findings support alterations in the salience, reward, and lateral orbital nonreward networks as common across disorders, including anxiety and depressive disorders. These findings add to the growing body of work that supports the concept that there are common underlying factors across all types of psychopathology that include internalizing, externalizing, and thought disorder dimensions ( 26 ). Dr. Deanna Barch, from Washington University in St. Louis, writes an editorial commenting on these findings and, importantly, discusses criteria that should be met when we consider whether the findings are actually transdiagnostic ( 27 ).

Another article, from Gray and colleagues ( 28 ), addresses whether there is a convergence of findings, specifically in major depression, when examining data from different structural and functional neuroimaging modalities. The authors report that, consistent with what we know about regions involved in emotion processing, the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala were among the regions that showed convergence across multimodal imaging modalities.

In relation to treatment and building on our understanding of neural circuit alterations, Siddiqi et al. ( 29 ) present data suggesting that transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) targeting can be linked to symptom-specific treatments. Their findings identify different TMS targets in the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex that modulate different downstream networks. The modulation of these different networks appears to be associated with a reduction in different types of symptoms. In an editorial, Drs. Sean Nestor and Daniel Blumberger, from the University of Toronto ( 30 ), comment on the novel approach used in this study to link the TMS-related engagement of circuits with symptom improvement. They also provide a perspective on how we can view these and other circuit-based findings in relation to conceptualizing personalized treatment approaches.

Kendler et al. ( 31 ), in this issue, contribute an article that demonstrates the important role of the rearing environment in the risk to develop major depression. Using a unique design from a Swedish sample, the analytic strategy involves comparing outcomes from high-risk full sibships and high-risk half sibships where at least one of the siblings was home reared and one was adopted out of the home. The findings support the importance of the quality of the rearing environment as well as the presence of parental depression in mitigating or enhancing the likelihood of developing major depression. In an accompanying editorial ( 32 ), Dr. Myrna Weissman, from Columbia University, reviews the methods and findings of the Kendler et al. article and also emphasizes the critical significance of the early nurturing environment in relation to general health.

This issue concludes with an intriguing article on anxiety disorders, by Gold and colleagues ( 33 ), that demonstrates neural alterations during extinction recall that differ in children relative to adults. With increasing age, and in relation to fear and safety cues, nonanxious adults demonstrated greater connectivity between the amygdala and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex compared with anxious adults, as the cues were being perceived as safer. In contrast, neural differences between anxious and nonanxious youths were more robust when rating the memory of faces that were associated with threat. Specifically, these differences were observed in the activation of the inferior temporal cortex. In their editorial ( 34 ), Dr. Dylan Gee and Sahana Kribakaran, from Yale University, emphasize the importance of developmental work in relation to understanding anxiety disorders, place these findings into the context of other work, and suggest the possibility that these and other data point to neuroscientifically informed age-specific interventions.

Taken together, the papers in this issue of the Journal present new findings that shed light onto alterations in neural function that underlie major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders. It is important to remember that these disorders are highly comorbid and that their symptoms are frequently not separable. The papers in this issue also provide a developmental perspective emphasizing the importance of early rearing in the risk to develop depression and age-related findings important for understanding threat processing in patients with anxiety disorders. From a treatment perspective, the papers introduce data supporting more selective prefrontal cortical TMS targeting in relation to different symptoms, address the potential and drawbacks for considering the future use of psychedelics in our treatments, and present new ideas supporting age-specific interventions for youths and adults with anxiety disorders.

Disclosures of Editors’ financial relationships appear in the April 2020 issue of the Journal .

1 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA): Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. SMA 18-5068, NSDUH Series H-53). Rockville, Md, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, SAMHSA, 2018. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSDUHFFR2017/NSDUHFFR2017.htm Google Scholar

2 Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, et al. : Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication . Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005 ; 62:617–627, correction, 62:709 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

3 Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, et al. : Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) . J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2010 ; 49:980–989 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

4 Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al. : Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey . Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994 ; 51:8–19 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

5 Kessler RC, Sampson NA, Berglund P, et al. : Anxious and non-anxious major depressive disorder in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys . Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2015 ; 24:210–226 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

6 Dunner DL : Management of anxiety disorders: the added challenge of comorbidity . Depress Anxiety 2001 ; 13:57–71 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

7 Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, et al. : Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey . Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995 ; 52:1048–1060 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

8 Brawman-Mintzer O, Lydiard RB, Emmanuel N, et al. : Psychiatric comorbidity in patients with generalized anxiety disorder . Am J Psychiatry 1993 ; 150:1216–1218 Link , Google Scholar

9 Fava M, Alpert JE, Carmin CN, et al. : Clinical correlates and symptom patterns of anxious depression among patients with major depressive disorder in STAR*D . Psychol Med 2004 ; 34:1299–1308 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

10 Hettema JM : What is the genetic relationship between anxiety and depression? Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 2008 ; 148C:140–146 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

11 Hettema JM, Neale MC, Myers JM, et al. : A population-based twin study of the relationship between neuroticism and internalizing disorders . Am J Psychiatry 2006 ; 163:857–864 Link , Google Scholar

12 Kovner R, Oler JA, Kalin NH : Cortico-limbic interactions mediate adaptive and maladaptive responses relevant to psychopathology . Am J Psychiatry 2019 ; 176:987–999 Link , Google Scholar

13 Etkin A, Schatzberg AF : Common abnormalities and disorder-specific compensation during implicit regulation of emotional processing in generalized anxiety and major depressive disorders . Am J Psychiatry 2011 ; 168:968–978 Link , Google Scholar

14 Goodkind M, Eickhoff SB, Oathes DJ, et al. : Identification of a common neurobiological substrate for mental illness . JAMA Psychiatry 2015 ; 72:305–315 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

15 McTeague LM, Huemer J, Carreon DM, et al. : Identification of common neural circuit disruptions in cognitive control across psychiatric disorders . Am J Psychiatry 2017 ; 174:676–685 Link , Google Scholar

16 Beesdo K, Knappe S, Pine DS : Anxiety and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: developmental issues and implications for DSM-V . Psychiatr Clin North Am 2009 ; 32:483–524 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

17 Kessler RC, Wang PS : The descriptive epidemiology of commonly occurring mental disorders in the United States . Annu Rev Public Health 2008 ; 29:115–129 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

18 Ohayon MM, Schatzberg AF : Social phobia and depression: prevalence and comorbidity . J Psychosom Res 2010 ; 68:235–243 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

19 Clauss JA, Blackford JU : Behavioral inhibition and risk for developing social anxiety disorder: a meta-analytic study . J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2012 ; 51:1066–1075 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

20 Fava M, Rush AJ, Alpert JE, et al. : Difference in treatment outcome in outpatients with anxious versus nonanxious depression: a STAR*D report . Am J Psychiatry 2008 ; 165:342–351 Link , Google Scholar

21 Dold M, Bartova L, Souery D, et al. : Clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes of patients with major depressive disorder and comorbid anxiety disorders: results from a European multicenter study . J Psychiatr Res 2017 ; 91:1–13 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

22 Spellman T, Liston C : Toward circuit mechanisms of pathophysiology in depression . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:381–390 Link , Google Scholar

23 Reiff CM, Richman EE, Nemeroff CB, et al. : Psychedelics and psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:391–410 Link , Google Scholar

24 Schatzberg AF : Some comments on psychedelic research (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:368–369 Link , Google Scholar

25 McTeague LM, Rosenberg BM, Lopez JW, et al. : Identification of common neural circuit disruptions in emotional processing across psychiatric disorders . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:411–421 Link , Google Scholar

26 Caspi A, Moffitt TE : All for one and one for all: mental disorders in one dimension . Am J Psychiatry 2018 ; 175:831–844 Link , Google Scholar

27 Barch DM : What does it mean to be transdiagnostic and how would we know? (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:370–372 Abstract , Google Scholar

28 Gray JP, Müller VI, Eickhoff SB, et al. : Multimodal abnormalities of brain structure and function in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:422–434 Link , Google Scholar

29 Siddiqi SH, Taylor SF, Cooke D, et al. : Distinct symptom-specific treatment targets for circuit-based neuromodulation . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:435–446 Link , Google Scholar

30 Nestor SM, Blumberger DM : Mapping symptom clusters to circuits: toward personalizing TMS targets to improve treatment outcomes in depression (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:373–375 Abstract , Google Scholar

31 Kendler KS, Ohlsson H, Sundquist J, et al. : The rearing environment and risk for major depression: a Swedish national high-risk home-reared and adopted-away co-sibling control study . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:447–453 Abstract , Google Scholar

32 Weissman MM : Is depression nature or nurture? Yes (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:376–377 Abstract , Google Scholar

33 Gold AL, Abend R, Britton JC, et al. : Age differences in the neural correlates of anxiety disorders: an fMRI study of response to learned threat . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:454–463 Link , Google Scholar

34 Gee DG, Kribakaran S : Developmental differences in neural responding to threat and safety: implications for treating youths with anxiety (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:378–380 Abstract , Google Scholar

- Cited by None

- Neuroanatomy

- Neurochemistry

- Neuroendocrinology

- Other Research Areas

Change Password

Your password must have 8 characters or more and contain 3 of the following:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

- Sign in / Register

Request Username

Can't sign in? Forgot your username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

An Exploratory Study of Students with Depression in Undergraduate Research Experiences

- Katelyn M. Cooper

- Logan E. Gin

- M. Elizabeth Barnes

- Sara E. Brownell

*Address correspondence to: Katelyn M. Cooper ( E-mail Address: [email protected] ).

Department of Biology, University of Central Florida, Orlando, FL, 32816

Search for more papers by this author

Biology Education Research Lab, Research for Inclusive STEM Education Center, School of Life Sciences, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85281

Depression is a top mental health concern among undergraduates and has been shown to disproportionately affect individuals who are underserved and underrepresented in science. As we aim to create a more inclusive scientific community, we argue that we need to examine the relationship between depression and scientific research. While studies have identified aspects of research that affect graduate student depression, we know of no studies that have explored the relationship between depression and undergraduate research. In this study, we sought to understand how undergraduates’ symptoms of depression affect their research experiences and how research affects undergraduates’ feelings of depression. We interviewed 35 undergraduate researchers majoring in the life sciences from 12 research-intensive public universities across the United States who identify with having depression. Using inductive and deductive coding, we identified that students’ depression affected their motivation and productivity, creativity and risk-taking, engagement and concentration, and self-perception and socializing in undergraduate research experiences. We found that students’ social connections, experiencing failure in research, getting help, receiving feedback, and the demands of research affected students’ depression. Based on this work, we articulate an initial set of evidence-based recommendations for research mentors to consider in promoting an inclusive research experience for students with depression.

INTRODUCTION

Depression is described as a common and serious mood disorder that results in persistent feelings of sadness and hopelessness, as well as a loss of interest in activities that one once enjoyed ( American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013 ). Additional symptoms of depression include weight changes, difficulty sleeping, loss of energy, difficulty thinking or concentrating, feelings of worthlessness or excessive guilt, and suicidality ( APA, 2013 ). While depression results from a complex interaction of psychological, social, and biological factors ( World Health Organization, 2018 ), studies have shown that increased stress caused by college can be a significant contributor to student depression ( Dyson and Renk, 2006 ).

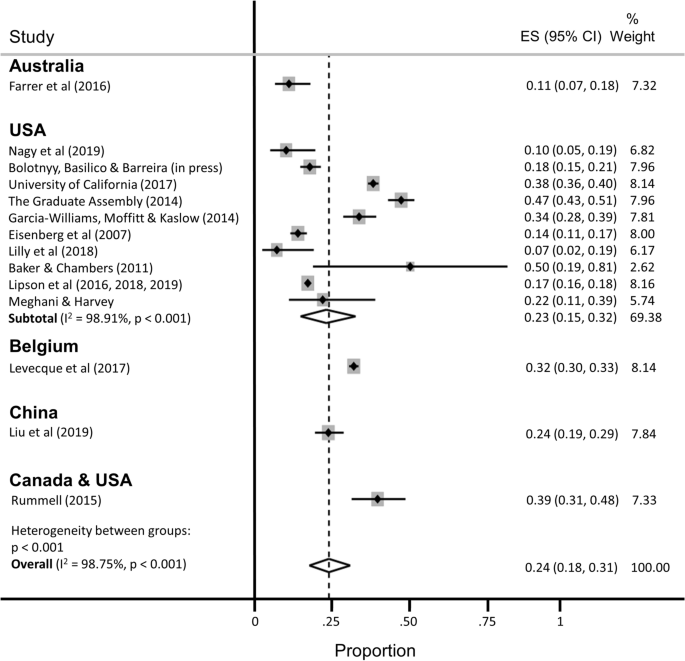

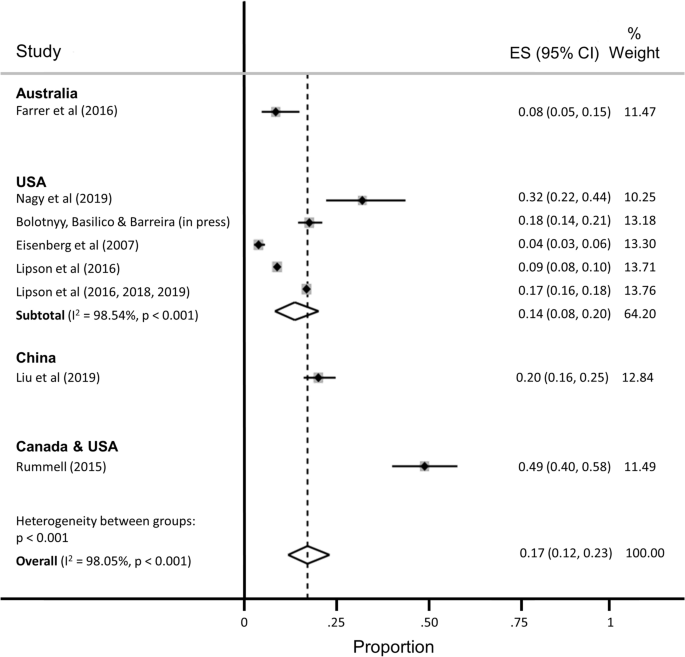

Depression is one of the top undergraduate mental health concerns, and the rate of depression among undergraduates continues to rise ( Center for Collegiate Mental Health, 2017 ). While we cannot discern whether these increasing rates of depression are due to increased awareness or increased incidence, it is clear that is a serious problem on college campuses. The percent of U.S. college students who self-reported a diagnosis with depression was recently estimated to be about 25% ( American College Health Association, 2019 ). However, higher rates have been reported, with one study estimating that up to 84% of undergraduates experience some level of depression ( Garlow et al. , 2008 ). Depression rates are typically higher among university students compared with the general population, despite being a more socially privileged group ( Ibrahim et al. , 2013 ). Prior studies have found that depression is negatively correlated with overall undergraduate academic performance ( Hysenbegasi et al. , 2005 ; Deroma et al. , 2009 ; American College Health Association, 2019 ). Specifically, diagnosed depression is associated with half a letter grade decrease in students’ grade point average ( Hysenbegasi et al. , 2005 ), and 21.6% of undergraduates reported that depression negatively affected their academic performance within the last year ( American College Health Association, 2019 ). Provided with a list of academic factors that may be affected by depression, students reported that depression contributed to lower exam grades, lower course grades, and not completing or dropping a course.

Students in the natural sciences may be particularly at risk for depression, given that such majors are noted to be particularly stressful due to their competitive nature and course work that is often perceived to “weed students out”( Everson et al. , 1993 ; Strenta et al. , 1994 ; American College Health Association, 2019 ; Seymour and Hunter, 2019 ). Science course instruction has also been described to be boring, repetitive, difficult, and math-intensive; these factors can create an environment that can trigger depression ( Seymour and Hewitt, 1997 ; Osborne and Collins, 2001 ; Armbruster et al ., 2009 ; Ceci and Williams, 2010 ). What also distinguishes science degree programs from other degree programs is that, increasingly, undergraduate research experiences are being proposed as an essential element of a science degree ( American Association for the Advancement of Science, 2011 ; President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, 2012 ; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine [NASEM], 2017 ). However, there is some evidence that undergraduate research experiences can add to the stress of college for some students ( Cooper et al. , 2019c ). Students can garner multiple benefits from undergraduate research, including enhanced abilities to think critically ( Ishiyama, 2002 ; Bauer and Bennett, 2003 ; Brownell et al. , 2015 ), improved student learning ( Rauckhorst et al. , 2001 ; Brownell et al. , 2015 ), and increased student persistence in undergraduate science degree programs ( Jones et al. , 2010 ; Hernandez et al. , 2018 ). Notably, undergraduate research experiences are increasingly becoming a prerequisite for entry into medical and graduate programs in science, particularly elite programs ( Cooper et al. , 2019d ). Although some research experiences are embedded into formal lab courses as course-based undergraduate research experiences (CUREs; Auchincloss et al. , 2014 ; Brownell and Kloser, 2015 ), the majority likely entail working with faculty in their research labs. These undergraduate research experiences in faculty labs are often added on top of a student’s normal course work, so they essentially become an extracurricular activity that they have to juggle with course work, working, and/or personal obligations ( Cooper et al. , 2019c ). While the majority of the literature surrounding undergraduate research highlights undergraduate research as a positive experience ( NASEM, 2017 ), studies have demonstrated that undergraduate research experiences can be academically and emotionally challenging for students ( Mabrouk and Peters, 2000 ; Seymour et al. , 2004 ; Cooper et al. , 2019c ; Limeri et al. , 2019 ). In fact, 50% of students sampled nationally from public R1 institutions consider leaving their undergraduate research experience prematurely, and about half of those students, or 25% of all students, ultimately leave their undergraduate research experience ( Cooper et al. , 2019c ). Notably, 33.8% of these individuals cited a negative lab environment and 33.3% cited negative relationships with their mentors as factors that influenced their decision about whether to leave ( Cooper et al. , 2019c ). Therefore, students’ depression may be exacerbated in challenging undergraduate research experiences, because studies have shown that depression is positively correlated with student stress ( Hish et al. , 2019 ).

While depression has not been explored in the context of undergraduate research experiences, depression has become a prominent concern surrounding graduate students conducting scientific research. A recent study that examined the “graduate student mental health crisis” ( Flaherty, 2018 ) found that work–life balance and graduate students’ relationships with their research advisors may be contributing to their depression ( Evans et al. , 2018 ). Specifically, this survey of 2279 PhD and master’s students from diverse fields of study, including the biological/physical sciences, showed that 39% of graduate students have experienced moderate to severe depression. Fifty-five percent of the graduate students with depression who were surveyed disagreed with the statement “I have good work life balance,” compared to only 21% of students with depression who agreed. Additionally, the study highlighted that more students with depression disagreed than agreed with the following statements: their advisors provided “real” mentorship, their advisors provided ample support, their advisors positively impacted their emotional or mental well-being, their advisors were assets to their careers, and they felt valued by their mentors. Another recent study identified that depression severity in biomedical doctoral students was significantly associated with graduate program climate, a perceived lack of employment opportunities, and the quality of students’ research training environment ( Nagy et al. , 2019 ). Environmental stress, academic stress, and family and monetary stress have also been shown to be predictive of depression severity in biomedical doctoral students ( Hish et al. , 2019 ). Further, one study found that self-esteem is negatively correlated and stress is positively correlated with graduate student depression; presumably research environments that challenge students’ self-esteem and induce stress are likely contributing to depressive symptoms among graduate students ( Kreger, 1995 ). While these studies have focused on graduate students, and there are certainly notable distinctions between graduate and undergraduate research, the research-related factors that affect graduate student depression, including work–life balance, relationships with mentors, research environment, stress, and self-esteem, may also be relevant to depression among undergraduates conducting research. Importantly, undergraduates in the United States have reported identical levels of depression as graduate students but are often less likely to seek mental health care services ( Wyatt and Oswalt, 2013 ), which is concerning if undergraduate research experiences exacerbate depression.

Based on the literature on the stressors of undergraduate research experiences and the literature identifying some potential causes of graduate student depression, we identified three aspects of undergraduate research that may exacerbate undergraduates’ depression. Mentoring: Mentors can be an integral part of a students’ research experience, bolstering their connections with others in the science community, scholarly productivity, and science identity, as well as providing many other benefits ( Thiry and Laursen, 2011 ; Prunuske et al. , 2013 ; Byars-Winston et al. , 2015 ; Aikens et al. , 2016 , 2017 ; Thompson et al. , 2016 ; Estrada et al. , 2018 ). However, recent literature has highlighted that poor mentoring can negatively affect undergraduate researchers ( Cooper et al. , 2019c ; Limeri et al. , 2019 ). Specifically, one study of 33 undergraduate researchers who had conducted research at 10 institutions identified seven major ways that they experienced negative mentoring, which included absenteeism, abuse of power, interpersonal mismatch, lack of career support, lack of psychosocial support, misaligned expectations, and unequal treatment ( Limeri et al. , 2019 ). We hypothesize negative mentoring experiences may be particularly harmful for students with depression, because support, particularly social support, has been shown to be important for helping individuals with depression cope with difficult circumstances ( Aneshensel and Stone, 1982 ; Grav et al. , 2012 ). Failure: Experiencing failure has been hypothesized to be an important aspect of undergraduate research experiences that may help students develop some the most distinguishing abilities of outstanding scientists, such as coping with failure, navigating challenges, and persevering ( Laursen et al. , 2010 ; Gin et al. , 2018 ; Henry et al. , 2019 ). However, experiencing failure and the stress and fatigue that often accompany it may be particularly tough for students with depression ( Aldwin and Greenberger, 1987 ; Mongrain and Blackburn, 2005 ). Lab environment: Fairness, inclusion/exclusion, and social support within one’s organizational environment have been shown to be key factors that cause people to either want to remain in the work place and be productive or to want to leave ( Barak et al. , 2006 ; Cooper et al. , 2019c ). We hypothesize that dealing with exclusion or a lack of social support may exacerbate depression for some students; patients with clinical depression react to social exclusion with more pronounced negative emotions than do individuals without clinical depression ( Jobst et al. , 2015 ). While there are likely other aspects of undergraduate research that affect student depression, we hypothesize that these factors have the potential to exacerbate negative research experiences for students with depression.

Depression has been shown to disproportionately affect many populations that are underrepresented or underserved within the scientific community, including females ( American College Health Association, 2018 ; Evans et al. , 2018 ), first-generation college students ( Jenkins et al. , 2013 ), individuals from low socioeconomic backgrounds ( Eisenberg et al. , 2007 ), members of the LGBTQ+ community ( Eisenberg et al. , 2007 ; Evans et al. , 2018 ), and people with disabilities ( Turner and Noh, 1988 ). Therefore, as the science community strives to be more diverse and inclusive ( Intemann, 2009 ), it is important that we understand more about the relationship between depression and scientific research, because negative experiences with depression in scientific research may be contributing to the underrepresentation of these groups. Specifically, more information is needed about how the research process and environment of research experiences may affect depression.

Given the high rate of depression among undergraduates, the links between depression and graduate research, the potentially challenging environment of undergraduate research, and how depression could disproportionately impact students from underserved communities, it is imperative to begin to explore the relationship between scientific research and depression among undergraduates to create research experiences that could maximize student success. In this exploratory interview study, we aimed to 1) describe how undergraduates’ symptoms of depression affect their research experiences, 2) understand how undergraduate research affects students’ feelings of depression, and 3) identify recommendations based on the literature and undergraduates’ reported experiences to promote a positive research experience for students with depression.

This study was done with an approved Arizona State University Institutional Review Board protocol #7247.

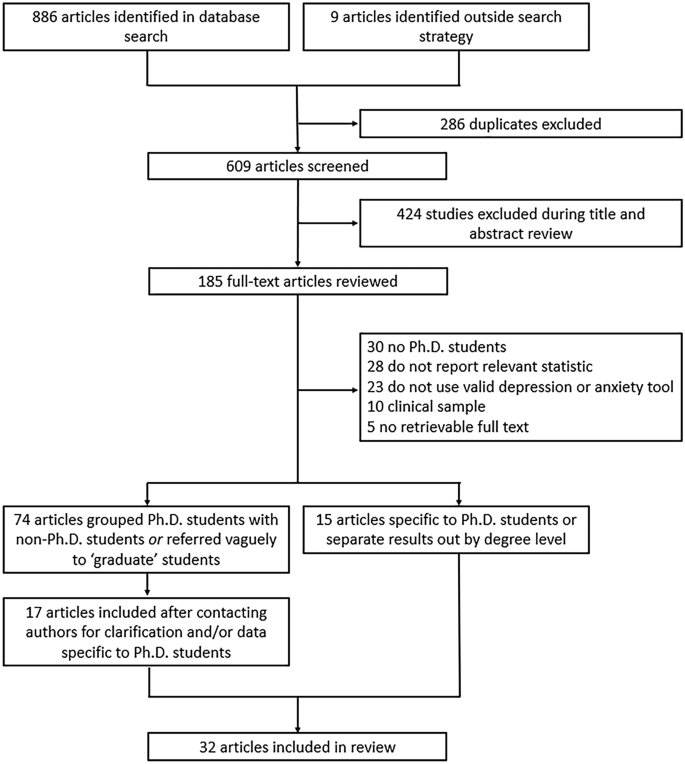

In Fall 2018, we surveyed undergraduate researchers majoring in the life sciences across 25 research-intensive (R1) public institutions across the United States (specific details about the recruitment of the students who completed the survey can be found in Cooper et al. (2019c) ). The survey asked students for their opinions about their undergraduate research experiences and their demographic information and whether they would be interested in participating in a follow-up interview related to their research experiences. For the purpose of this study, we exclusively interviewed students about their undergraduate research experiences in faculty member labs; we did not consider students’ experiences in CUREs. Of the 768 undergraduate researchers who completed the survey, 65% ( n = 496) indicated that they would be interested in participating in a follow-up interview. In Spring 2019, we emailed the 496 students, explaining that we were interested in interviewing students with depression about their experiences in undergraduate research. Our specific prompt was: “If you identify as having depression, we would be interested in hearing about your experience in undergraduate research in a 30–60 minute online interview.” We did not define depression in our email recruitment because we conducted think-aloud interviews with four undergraduates who all correctly interpreted what we meant by depression ( APA, 2013 ). We had 35 students agree to participate in the interview study. The interview participants represented 12 of the 25 R1 public institutions that were represented in the initial survey.

Student Interviews

We developed an interview script to explore our research questions. Specifically, we were interested in how students’ symptoms of depression affect their research experiences, how undergraduate research negatively affects student depression, and how undergraduate research positively affects student depression.

We recognized that mental health, and specifically depression, can be a sensitive topic to discuss with undergraduates, and therefore we tried to minimize any discomfort that the interviewees might experience during the interview. Specifically, we conducted think-aloud interviews with three graduate students who self-identified with having depression at the time of the interview. We asked them to note whether any interview questions made them uncomfortable. We also sought their feedback on questions given their experiences as persons with depression who had once engaged in undergraduate research. We revised the interview protocol after each think-aloud interview. Next, we conducted four additional think-aloud interviews with undergraduates conducting basic science or biology education research who identified with having depression to establish cognitive validity of the questions and to elicit additional feedback about any questions that might make someone uncomfortable. The questions were revised after each think-aloud interview until no question was unclear or misinterpreted by the students and we were confident that the questions minimized students’ potential discomfort ( Trenor et al. , 2011 ). A copy of the final interview script can be found in the Supplemental Material.

All interviews were individually conducted by one of two researchers (K.M.C. and L.E.G.) who conducted the think-aloud interviews together to ensure that their interviewing practices were as similar as possible. The interviews were approximately an hour long, and students received a $15 gift card for their participation.

Personal, Research, and Depression Demographics

All student demographics and information about students’ research experiences were collected using the survey distributed to students in Fall 2018. We collected personal demographics, including the participants’ gender, race/ethnicity, college generation status, transfer status, financial stability, year in college, major, and age. We also collected information about the students’ research experiences, including the length of their first research experiences, the average number of hours they spend in research per week, how they were compensated for research, who their primary mentors were, and the focus areas of their research.

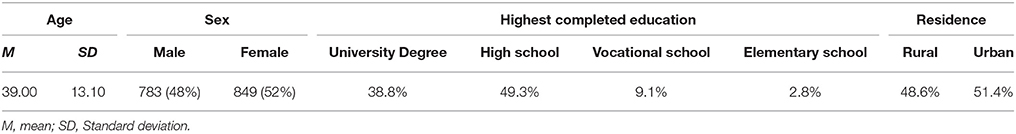

In the United States, mental healthcare is disproportionately unavailable to Black and Latinx individuals, as well as those who come from low socioeconomic backgrounds ( Kataoka et al. , 2002 ; Howell and McFeeters, 2008 ; Santiago et al. , 2013 ). Therefore, to minimize a biased sample, we invited anyone who identified with having depression to participate in our study; we did not require students to be diagnosed with depression or to be treated for depression in order to participate. However, we did collect information about whether students had been formally diagnosed with depression and whether they had been treated for depression. After the interview, all participants were sent a link to a short survey that asked them if they had ever been diagnosed with depression and how, if at all, they had ever been treated for depression. A copy of these survey questions can be found in the Supplemental Material. The combined demographic information of the participants is in Table 1 . The demographics for each individual student can be found in the Supplemental Material.

a Students reported the time they had spent in research 6 months before being interviewed and only reported on the length of time of their first research experiences.

b Students were invited to report multiple ways in which they were treated for their depression; other treatments included lifestyle changes and meditation.

c Students were invited to report multiple means of compensation for their research if they had been compensated for their time in different ways.

d Students were asked whether they felt financially stable, particularly during the undergraduate research experience.

e Students reported who they work/worked with most closely during their research experiences.

f Staff members included lab coordinators or lab managers.

g Other focus areas of research included sociology, linguistics, psychology, and public health.

Interview Analysis

The initial interview analysis aimed to explore each idea that a participant expressed ( Charmaz, 2006 ) and to identify reoccurring ideas throughout the interviews. First, three authors (K.M.C., L.E.G., and S.E.B.) individually reviewed a different set of 10 interviews and took detailed analytic notes ( Birks and Mills, 2015 ). Afterward, the authors compared their notes and identified reoccurring themes throughout the interviews using open coding methods ( Saldaña, 2015 ).

Once an initial set of themes was established, two researchers (K.M.C. and L.E.G.) individually reviewed the same set of 15 randomly selected interviews to validate the themes identified in the initial analysis and to screen for any additional themes that the initial analysis may have missed. Each researcher took detailed analytic notes throughout the review of an interview, which they discussed after reviewing each interview. The researchers compared what quotes from each interview they categorized into each theme. Using constant comparison methods, they assigned quotes to each theme and constantly compared the quotes to ensure that each quote fit within the description of the theme ( Glesne and Peshkin, 1992 ). In cases in which quotes were too different from other quotes, a new theme was created. This approach allowed for multiple revisions of the themes and allowed the authors to define a final set of codes; the researchers created a final codebook with refined definitions of emergent themes (the final coding rubric can be found in the Supplemental Material). Once the final codebook was established, the researchers (K.M.C. and L.E.G.) individually coded seven additional interviews (20% of all interviews) using the coding rubric. The researchers compared their codes, and their Cohen’s κ interrater score for these seven interviews was at an acceptable level (κ = 0.88; Landis and Koch, 1977 ). One researcher (L.E.G.) coded the remaining 28 out of 35 interviews. The researchers determined that data saturation had been reached with the current sample and no further recruitment was needed ( Guest et al. , 2006 ). We report on themes that were mentioned by at least 20% of students in the interview study. In the Supplemental Material, we provide the final coding rubric with the number of participants whose interview reflected each theme ( Hannah and Lautsch, 2011 ). Reporting the number of individuals who reported themes within qualitative data can lead to inaccurate conclusions about the generalizability of the results to a broader population. These qualitative data are meant to characterize a landscape of experiences that students with depression have in undergraduate research rather than to make claims about the prevalence of these experiences ( Glesne and Peshkin, 1992 ). Because inferences about the importance of these themes cannot be drawn from these counts, they are not included in the results of the paper ( Maxwell, 2010 ). Further, the limited number of interviewees made it not possible to examine whether there were trends based on students’ demographics or characteristics of their research experiences (e.g., their specific area of study). Quotes were lightly edited for clarity by inserting clarification brackets and using ellipses to indicate excluded text. Pseudonyms were given to all students to protect their privacy.

The Effect of Depressive Symptoms on Undergraduate Research

We asked students to describe the symptoms associated with their depression. Students described experiencing anxiety that is associated with their depression; this could be anxiety that precedes their depression or anxiety that results from a depressive episode or a period of time when an individual has depression symptoms. Further, students described difficulty getting out of bed or leaving the house, feeling tired, a lack of motivation, being overly self-critical, feeling apathetic, and having difficulty concentrating. We were particularly interested in how students’ symptoms of depression affected their experiences in undergraduate research. During the think-aloud interviews that were conducted before the interview study, graduate and undergraduate students consistently described that their depression affected their motivation in research, their creativity in research, and their productivity in research. Therefore, we explicitly asked undergraduate researchers how, if at all, their depression affected these three factors. We also asked students to describe any additional ways in which their depression affected their research experiences. Undergraduate researchers commonly described five additional ways in which their depression affected their research; for a detailed description of each way students’ research was affected and for example quotes, see Table 2 . Students described that their depression negatively affected their productivity in the lab. Commonly, students described that their productivity was directly affected by a lack of motivation or because they felt less creative, which hindered the research process. Additionally, students highlighted that they were sometimes less productive because their depression sometimes caused them to struggle to engage intellectually with their research or caused them to have difficulty remembering or concentrating; students described that they could do mundane or routine tasks when they felt depressed, but that they had difficulty with more complex and intellectually demanding tasks. However, students sometimes described that even mundane tasks could be difficult when they were required to remember specific steps; for example, some students struggled recalling a protocol from memory when their depression was particularly severe. Additionally, students noted that their depression made them more self-conscious, which sometimes held them back from sharing research ideas with their mentors or from taking risks such as applying to competitive programs. In addition to being self-conscious, students highlighted that their depression caused them to be overly self-critical, and some described experiencing imposter phenomenon ( Clance and Imes, 1978 ) or feeling like they were not talented enough to be in research and were accepted into a lab by a fluke or through luck. Finally, students described that depression often made them feel less social, and they struggled to socially engage with other members of the lab when they were feeling down.

The Effect of Undergraduate Research Experiences on Student Depression

We also wanted to explore how research impacted students’ feelings of depression. Undergraduates described how research both positively and negatively affected their depression. In the following sections, we present aspects of undergraduate research and examine how each positively and/or negatively affected students’ depression using embedded student quotes to highlight the relationships between related ideas.

Lab Environment: Relationships with Others in the Lab.

Some aspects of the lab environment, which we define as students’ physical, social, or psychological research space, could be particularly beneficial for students with depression.

Specifically, undergraduate researchers perceived that comfortable and positive social interactions with others in the lab helped their depression. Students acknowledged how beneficial their relationships with graduate students and postdocs could be.

Marta: “I think always checking in on undergrads is important. It’s really easy [for us] to go a whole day without talking to anybody in the lab. But our grad students are like ‘Hey, what’s up? How’s school? What’s going on?’ (…) What helps me the most is having that strong support system. Sometimes just talking makes you feel better, but also having people that believe in you can really help you get out of that negative spiral. I think that can really help with depression.”

Kelley: “I know that anytime I need to talk to [my postdoc mentors] about something they’re always there for me. Over time we’ve developed a relationship where I know that outside of work and outside of the lab if I did want to talk to them about something I could talk to them. Even just talking to someone about hobbies and having that relationship alone is really helpful [for depression].”

In addition to highlighting the importance of developing relationships with graduate students or postdocs in the lab, students described that forming relationships with other undergraduates in the lab also helped their depression. Particularly, students described that other undergraduate researchers often validated their feelings about research, which in turn helped them realize that what they are thinking or feeling is normal, which tended to alleviate their negative thoughts. Interestingly, other undergraduates experiencing the same issues could sometimes help buffer them from perceiving that a mentor did not like them or that they were uniquely bad at research. In this article, we use the term “mentor” to refer to anyone who students referred to in the interviews as being their mentors or managing their research experiences; this includes graduate students, postdoctoral scholars, lab managers, and primary investigators (PIs).

Abby: “One of my best friends is in the lab with me. A lot of that friendship just comes from complaining about our stress with the lab and our annoyance with people in the lab. Like when we both agree like, ‘Yeah, the grad students were really off today, it wasn’t us,’ that helps. ‘It wasn’t me, it wasn’t my fault that we were having a rough day in lab; it was the grad students.’ Just being able to realize, ‘Hey, this isn’t all caused by us,’ you know? (…) We understand the stresses in the lab. We understand the details of what each other are doing in the lab, so when something doesn’t work out, we understand that it took them like eight hours to do that and it didn’t work. We provide empathy on a different level.”

Meleana: “It’s great to have solidarity in being confused about something, and it’s just that is a form of validation for me too. When we leave a lab meeting and I look at [another undergrad] I’m like, ‘Did you understand anything that they were just saying?’ And they’re like, ‘Oh, no.’ (…) It’s just really validating to hear from the other undergrads that we all seem to be struggling with the same things.”

Developing positive relationships with faculty mentors or PIs also helped alleviate some students’ depressive feelings, particularly when PIs shared their own struggles with students. This also seemed to normalize students’ concerns about their own experiences.

Alexandra: “[Talking with my PI] is helpful because he would talk about his struggles, and what he faced. A lot of it was very similar to my struggles. For example, he would say, ‘Oh, yeah, I failed this exam that I studied so hard for. I failed the GRE and I paid so much money to prepare for it.’ It just makes [my depression] better, like okay, this is normal for students to go through this. It’s not an out of this world thing where if you fail, you’re a failure and you can’t move on from it.”

Students’ relationships with others in the lab did not always positively impact their depression. Students described instances when the negative moods of the graduate students and PIs would often set the tone of the lab, which in turn worsened the mood of the undergraduate researchers.

Abby: “Sometimes [the grad students] are not in a good mood. The entire vibe of the lab is just off, and if you make a joke and it hits somebody wrong, they get all mad. It really depends on the grad students and the leadership and the mood that they’re in.”

Interviewer: “How does it affect your depression when the grad students are in a bad mood?”

Abby: “It definitely makes me feel worse. It feels like, again, that I really shouldn’t go ask them for help because they’re just not in the mood to help out. It makes me have more pressure on myself, and I have deadlines I need to meet, but I have a question for them, but they’re in a bad mood so I can’t ask. That’s another day wasted for me and it just puts more stress, which just adds to the depression.”

Additionally, some students described even more concerning behavior from research mentors, which negatively affected their depression.

Julie: “I had a primary investigator who is notorious in the department for screaming at people, being emotionally abusive, unreasonable, et cetera. (…) [He was] kind of harassing people, demeaning them, lying to them, et cetera, et cetera. (…) Being yelled at and constantly demeaned and harassed at all hours of the day and night, that was probably pretty bad for me.”

While the relationships between undergraduates and graduate, postdoc, and faculty mentors seemed to either alleviate or worsen students’ depressive symptoms, depending on the quality of the relationship, students in this study exclusively described their relationships with other undergraduates as positive for their depression. However, students did note that undergraduate research puts some of the best and brightest undergraduates in the same environment, which can result in students comparing themselves with their peers. Students described that this comparison would often lead them to feel badly about themselves, even though they would describe their personal relationship with a person to be good.

Meleana: “In just the research field in general, just feeling like I don’t really measure up to the people around me [can affect my depression]. A lot of the times it’s the beginning of a little spiral, mental spiral. There are some past undergrads that are talked about as they’re on this pedestal of being the ideal undergrads and that they were just so smart and contributed so much to the lab. I can never stop myself from wondering like, ‘Oh, I wonder if I’m having a contribution to the lab that’s similar or if I’m just another one of the undergrads that does the bare minimum and passes through and is just there.’”

Natasha: “But, on the other hand, [having another undergrad in the lab] also reminded me constantly that some people are invested in this and meant to do this and it’s not me. And that some people know a lot more than I do and will go further in this than I will.”

While students primarily expressed that their relationships with others in the lab affected their depression, some students explained that they struggled most with depression when the lab was empty; they described that they did not like being alone in the lab, because a lack of stimulation allowed their minds to be filled with negative thoughts.

Mia: “Those late nights definitely didn’t help [my depression]. I am alone, in the entire building. I’m left alone to think about my thoughts more, so not distracted by talking to people or interacting with people. I think more about how I’m feeling and the lack of progress I’m making, and the hopelessness I’m feeling. That kind of dragged things on, and I guess deepened my depression.”

Freddy: “Often times when I go to my office in the evening, that is when I would [ sic ] be prone to be more depressed. It’s being alone. I think about myself or mistakes or trying to correct mistakes or whatever’s going on in my life at the time. I become very introspective. I think I’m way too self-evaluating, way too self-deprecating and it’s when I’m alone when those things are really, really triggered. When I’m talking with somebody else, I forget about those things.”

In sum, students with depression highlighted that a lab environment full of positive and encouraging individuals was helpful for their depression, whereas isolating or competitive environments and negative interactions with others often resulted in more depressive feelings.

Doing Science: Experiencing Failure in Research, Getting Help, Receiving Feedback, Time Demands, and Important Contributions.

In addition to the lab environment, students also described that the process of doing science could affect their depression. Specifically, students explained that a large contributor to their depression was experiencing failure in research.

Interviewer: “Considering your experience in undergraduate research, what tends to trigger your feelings of depression?”

Heather: “Probably just not getting things right. Having to do an experiment over and over again. You don’t get the results you want. (…) The work is pretty meticulous and it’s frustrating when I do all this work, I do a whole experiment, and then I don’t get any results that I can use. That can be really frustrating. It adds to the stress. (…) It’s hard because you did all this other stuff before so you can plan for the research, and then something happens and all the stuff you did was worthless basically.”

Julie: “I felt very negatively about myself [when a project failed] and pretty panicked whenever something didn’t work because I felt like it was a direct reflection on my effort and/or intelligence, and then it was a big glaring personal failure.”

Students explained that their depression related to failing in research was exacerbated if they felt as though they could not seek help from their research mentors. Perceived insufficient mentor guidance has been shown to be a factor influencing student intention to leave undergraduate research ( Cooper et al. , 2019c ). Sometimes students talked about their research mentors being unavailable or unapproachable.

Michelle: “It just feels like [the graduate students] are not approachable. I feel like I can’t approach them to ask for their understanding in a certain situation. It makes [my depression] worse because I feel like I’m stuck, and that I’m being limited, and like there’s nothing I can do. So then I kind of feel like it’s my fault that I can’t do anything.”

Other times, students described that they did not seek help in fear that they would be negatively evaluated in research, which is a fear of being judged by others ( Watson and Friend, 1969 ; Weeks et al. , 2005 ; Cooper et al. , 2018 ). That is, students fear that their mentor would think negatively about them or judge them if they were to ask questions that their mentor thought they should know the answer to.

Meleana: “I would say [my depression] tends to come out more in being more reserved in asking questions because I think that comes more like a fear-based thing where I’m like, ‘Oh, I don’t feel like I’m good enough and so I don’t want to ask these questions because then my mentors will, I don’t know, think that I’m dumb or something.’”

Conversely, students described that mentors who were willing to help them alleviated their depressive feelings.

Crystal: “Yeah [my grad student] is always like, ‘Hey, I can check in on things in the lab because you’re allowed to ask me for that, you’re not totally alone in this,’ because he knows that I tend to take on all this responsibility and I don’t always know how to ask for help. He’s like, ‘You know, this is my lab too and I am here to help you as well,’ and just reminds me that I’m not shouldering this burden by myself.”

Ashlyn: “The graduate student who I work with is very kind and has a lot of patience and he really understands a lot of things and provides simple explanations. He does remind me about things and he will keep on me about certain tasks that I need to do in an understanding way, and it’s just because he’s patient and he listens.”

In addition to experiencing failure in science, students described that making mistakes when doing science also negatively affected their depression.

Abby: “I guess not making mistakes on experiments [is important in avoiding my depression]. Not necessarily that your experiment didn’t turn out to produce the data that you wanted, but just adding the wrong enzyme or messing something up like that. It’s like, ‘Oh, man,’ you know? You can get really down on yourself about that because it can be embarrassing.”

Commonly, students described that the potential for making mistakes increased their stress and anxiety regarding research; however, they explained that how other people responded to a potential mistake was what ultimately affected their depression.

Briana: “Sometimes if I made a mistake in correctly identifying an eye color [of a fly], [my PI] would just ridicule me in front of the other students. He corrected me but his method of correcting was very discouraging because it was a ridicule. It made the others laugh and I didn’t like that.”

Julie: “[My PI] explicitly [asked] if I had the dedication for science. A lot of times he said I had terrible judgment. A lot of times he said I couldn’t be trusted. Once I went to a conference with him, and, unfortunately, in front of another professor, he called me a klutz several times and there was another comment about how I never learn from my mistakes.”

When students did do things correctly, they described how important it could be for them to receive praise from their mentors. They explained that hearing praise and validation can be particularly helpful for students with depression, because their thoughts are often very negative and/or because they have low self-esteem.

Crystal: “[Something that helps my depression is] I have text messages from [my graduate student mentor] thanking me [and another undergraduate researcher] for all of the work that we’ve put in, that he would not be able to be as on track to finish as he is if he didn’t have our help.”

Interviewer: “Why is hearing praise from your mentor helpful?”

Crystal: “Because a lot of my depression focuses on everybody secretly hates you, nobody likes you, you’re going to die alone. So having that validation [from my graduate mentor] is important, because it flies in the face of what my depression tells me.”

Brian: “It reminds you that you exist outside of this negative world that you’ve created for yourself, and people don’t see you how you see yourself sometimes.”

Students also highlighted how research could be overwhelming, which negatively affected their depression. Particularly, students described that research demanded a lot of their time and that their mentors did not always seem to be aware that they were juggling school and other commitments in addition to their research. This stress exacerbated their depression.

Rose: “I feel like sometimes [my grad mentors] are not very understanding because grad students don’t take as many classes as [undergrads] do. I think sometimes they don’t understand when I say I can’t come in at all this week because I have finals and they’re like, ‘Why though?’”

Abby: “I just think being more understanding of student life would be great. We have classes as well as the lab, and classes are the priority. They forget what it’s like to be a student. You feel like they don’t understand and they could never understand when you say like, ‘I have three exams this week,’ and they’re like, ‘I don’t care. You need to finish this.’”

Conversely, some students reported that their research labs were very understanding of students’ schedules. Interestingly, these students talked most about how helpful it was to be able to take a mental health day and not do research on days when they felt down or depressed.

Marta: “My lab tech is very open, so she’ll tell us, ‘I can’t come in today. I have to take a mental health day.’ So she’s a really big advocate for that. And I think I won’t personally tell her that I’m taking a mental health day, but I’ll say, ‘I can’t come in today, but I’ll come in Friday and do those extra hours.’ And she’s like, ‘OK great, I’ll see you then.’ And it makes me feel good, because it helps me take care of myself first and then I can take care of everything else I need to do, which is amazing.”

Meleana: “Knowing that [my mentors] would be flexible if I told them that I’m crazy busy and can’t come into work nearly as much this week [helps my depression]. There is flexibility in allowing me to then care for myself.”

Interviewer: “Why is the flexibility helpful given the depression?”

Meleana: “Because sometimes for me things just take a little bit longer when I’m feeling down. I’m just less efficient to be honest, and so it’s helpful if I feel like I can only go into work for 10 hours in a week. It declutters my brain a little bit to not have to worry about all the things I have to do in work in addition the things that I need to do for school or clubs, or family or whatever.”

Despite the demanding nature of research, a subset of students highlighted that their research and research lab provided a sense of stability or familiarity that distracted them from their depression.

Freddy: “I’ll [do research] to run away from those [depressive] feelings or whatever. (…) I find sadly, I hate to admit it, but I do kind of run to [my lab]. I throw myself into work to distract myself from the feelings of depression and sadness.”

Rose: “When you’re sad or when you’re stressed you want to go to things you’re familiar with. So because lab has always been in my life, it’s this thing where it’s going to be there for me I guess. It’s like a good book that you always go back to and it’s familiar and it makes you feel good. So that’s how lab is. It’s not like the greatest thing in the world but it’s something that I’m used to, which is what I feel like a lot of people need when they’re sad and life is not going well.”

Many students also explained that research positively affects their depression because they perceive their research contribution to be important.

Ashlyn: “I feel like I’m dedicating myself to something that’s worthy and something that I believe in. It’s really important because it contextualizes those times when I am feeling depressed. It’s like, no, I do have these better things that I’m working on. Even when I don’t like myself and I don’t like who I am, which is again, depression brain, I can at least say, ‘Well, I have all these other people relying on me in research and in this area and that’s super important.’”

Jessica: “I mean, it just felt like the work that I was doing had meaning and when I feel like what I’m doing is actually going to contribute to the world, that usually really helps with [depression] because it’s like not every day you can feel like you’re doing something impactful.”

In sum, students highlighted that experiencing failure in research and making mistakes negatively contributed to depression, especially when help was unavailable or research mentors had a negative reaction. Additionally, students acknowledged that the research could be time-consuming, but that research mentors who were flexible helped assuage depressive feelings that were associated with feeling overwhelmed. Finally, research helped some students’ depression, because it felt familiar, provided a distraction from depression, and reminded students that they were contributing to a greater cause.

We believe that creating more inclusive research environments for students with depression is an important step toward broadening participation in science, not only to ensure that we are not discouraging students with depression from persisting in science, but also because depression has been shown to disproportionately affect underserved and underrepresented groups in science ( Turner and Noh, 1988 ; Eisenberg et al. , 2007 ; Jenkins et al. , 2013 ; American College Health Association, 2018 ). We initially hypothesized that three features of undergraduate research—research mentors, the lab environment, and failure—may have the potential to exacerbate student depression. We found this to be true; students highlighted that their relationships with their mentors as well as the overall lab environment could negatively affect their depression, but could also positively affect their research experiences. Students also noted that they struggled with failure, which is likely true of most students, but is known to be particularly difficult for students with depression ( Elliott et al. , 1997 ). We expand upon our findings by integrating literature on depression with the information that students provided in the interviews about how research mentors can best support students. We provide a set of evidence-based recommendations focused on mentoring, the lab environment, and failure for research mentors wanting to create more inclusive research environments for students with depression. Notably, only the first recommendation is specific to students with depression; the others reflect recommendations that have previously been described as “best practices” for research mentors ( NASEM, 2017 , 2019 ; Sorkness et al. , 2017 ) and likely would benefit most students. However, we examine how these recommendations may be particularly important for students with depression. As we hypothesized, these recommendations directly address three aspects of research: mentors, lab environment, and failure. A caveat of these recommendations is that more research needs to be done to explore the experiences of students with depression and how these practices actually impact students with depression, but our national sample of undergraduate researchers with depression can provide an initial starting point for a discussion about how to improve research experiences for these students.

Recommendations to Make Undergraduate Research Experiences More Inclusive for Students with Depression

Recognize student depression as a valid illness..

Allow students with depression to take time off of research by simply saying that they are sick and provide appropriate time for students to recover from depressive episodes. Also, make an effort to destigmatize mental health issues.

Undergraduate researchers described both psychological and physical symptoms that manifested as a result of their depression and highlighted how such symptoms prevented them from performing to their full potential in undergraduate research. For example, students described how their depression would cause them to feel unmotivated, which would often negatively affect their research productivity. In cases in which students were motivated enough to come in and do their research, they described having difficulty concentrating or engaging in the work. Further, when doing research, students felt less creative and less willing to take risks, which may alter the quality of their work. Students also sometimes struggled to socialize in the lab. They described feeling less social and feeling overly self-critical. In sum, students described that, when they experienced a depressive episode, they were not able to perform to the best of their ability, and it sometimes took a toll on them to try to act like nothing was wrong, when they were internally struggling with depression. We recommend that research mentors treat depression like any other physical illness; allowing students the chance to recover when they are experiencing a depressive episode can be extremely important to students and can allow them to maximize their productivity upon returning to research ( Judd et al. , 2000 ). Students explained that if they are not able to take the time to focus on recovering during a depressive episode, then they typically continue to struggle with depression, which negatively affects their research. This sentiment is echoed by researchers in psychiatry who have found that patients who do not fully recover from a depressive episode are more likely to relapse and to experience chronic depression ( Judd et al. , 2000 ). Students described not doing tasks or not showing up to research because of their depression but struggling with how to share that information with their research mentors. Often, students would not say anything, which caused them anxiety because they were worried about what others in the lab would say to them when they returned. Admittedly, many students understood why this behavior would cause their research mentors to be angry or frustrated, but they weighed the consequences of their research mentors’ displeasure against the consequences of revealing their depression and decided it was not worth admitting to being depressed. This aligns with literature that suggests that when individuals have concealable stigmatized identities, or identities that can be hidden and that carry negative stereotypes, such as depression, they will often keep them concealed to avoid negative judgment or criticism ( Link and Phelan, 2001 ; Quinn and Earnshaw, 2011 ; Jones and King, 2014 ; Cooper and Brownell, 2016 ; Cooper et al. , 2019b ; Cooper et al ., unpublished data ). Therefore, it is important for research mentors to be explicit with students that 1) they recognize mental illness as a valid sickness and 2) that students with mental illness can simply explain that they are sick if they need to take time off. This may be useful to overtly state on a research website or in a research syllabus, contract, or agreement if mentors use such documents when mentoring undergraduates in their lab. Further, research mentors can purposefully work to destigmatize mental health issues by explicitly stating that struggling with mental health issues, such as depression and anxiety, is common. While we do not recommend that mentors ask students directly about depression, because this can force students to share when they are not comfortable sharing, we do recommend providing opportunities for students to reveal their depression ( Chaudoir and Fisher, 2010 ). Mentors can regularly check in with students about how they’re doing, and talk openly about the importance of mental health, which may increase the chance that students may feel comfortable revealing their depression ( Chaudoir and Quinn, 2010 ; Cooper et al ., unpublished data ).

Foster a Positive Lab Environment.

Encourage positivity in the research lab, promote working in shared spaces to enhance social support among lab members, and alleviate competition among undergraduates.