The Ultimate Guide to Qualitative Research - Part 1: The Basics

- Introduction and overview

- What is qualitative research?

- What is qualitative data?

- Examples of qualitative data

- Qualitative vs. quantitative research

- Mixed methods

- Qualitative research preparation

- Theoretical perspective

- Theoretical framework

- Literature reviews

Research question

- Conceptual framework

- Conceptual vs. theoretical framework

Data collection

- Qualitative research methods

- Focus groups

- Observational research

What is a case study?

Applications for case study research, what is a good case study, process of case study design, benefits and limitations of case studies.

- Ethnographical research

- Ethical considerations

- Confidentiality and privacy

- Power dynamics

- Reflexivity

Case studies

Case studies are essential to qualitative research , offering a lens through which researchers can investigate complex phenomena within their real-life contexts. This chapter explores the concept, purpose, applications, examples, and types of case studies and provides guidance on how to conduct case study research effectively.

Whereas quantitative methods look at phenomena at scale, case study research looks at a concept or phenomenon in considerable detail. While analyzing a single case can help understand one perspective regarding the object of research inquiry, analyzing multiple cases can help obtain a more holistic sense of the topic or issue. Let's provide a basic definition of a case study, then explore its characteristics and role in the qualitative research process.

Definition of a case study

A case study in qualitative research is a strategy of inquiry that involves an in-depth investigation of a phenomenon within its real-world context. It provides researchers with the opportunity to acquire an in-depth understanding of intricate details that might not be as apparent or accessible through other methods of research. The specific case or cases being studied can be a single person, group, or organization – demarcating what constitutes a relevant case worth studying depends on the researcher and their research question .

Among qualitative research methods , a case study relies on multiple sources of evidence, such as documents, artifacts, interviews , or observations , to present a complete and nuanced understanding of the phenomenon under investigation. The objective is to illuminate the readers' understanding of the phenomenon beyond its abstract statistical or theoretical explanations.

Characteristics of case studies

Case studies typically possess a number of distinct characteristics that set them apart from other research methods. These characteristics include a focus on holistic description and explanation, flexibility in the design and data collection methods, reliance on multiple sources of evidence, and emphasis on the context in which the phenomenon occurs.

Furthermore, case studies can often involve a longitudinal examination of the case, meaning they study the case over a period of time. These characteristics allow case studies to yield comprehensive, in-depth, and richly contextualized insights about the phenomenon of interest.

The role of case studies in research

Case studies hold a unique position in the broader landscape of research methods aimed at theory development. They are instrumental when the primary research interest is to gain an intensive, detailed understanding of a phenomenon in its real-life context.

In addition, case studies can serve different purposes within research - they can be used for exploratory, descriptive, or explanatory purposes, depending on the research question and objectives. This flexibility and depth make case studies a valuable tool in the toolkit of qualitative researchers.

Remember, a well-conducted case study can offer a rich, insightful contribution to both academic and practical knowledge through theory development or theory verification, thus enhancing our understanding of complex phenomena in their real-world contexts.

What is the purpose of a case study?

Case study research aims for a more comprehensive understanding of phenomena, requiring various research methods to gather information for qualitative analysis . Ultimately, a case study can allow the researcher to gain insight into a particular object of inquiry and develop a theoretical framework relevant to the research inquiry.

Why use case studies in qualitative research?

Using case studies as a research strategy depends mainly on the nature of the research question and the researcher's access to the data.

Conducting case study research provides a level of detail and contextual richness that other research methods might not offer. They are beneficial when there's a need to understand complex social phenomena within their natural contexts.

The explanatory, exploratory, and descriptive roles of case studies

Case studies can take on various roles depending on the research objectives. They can be exploratory when the research aims to discover new phenomena or define new research questions; they are descriptive when the objective is to depict a phenomenon within its context in a detailed manner; and they can be explanatory if the goal is to understand specific relationships within the studied context. Thus, the versatility of case studies allows researchers to approach their topic from different angles, offering multiple ways to uncover and interpret the data .

The impact of case studies on knowledge development

Case studies play a significant role in knowledge development across various disciplines. Analysis of cases provides an avenue for researchers to explore phenomena within their context based on the collected data.

This can result in the production of rich, practical insights that can be instrumental in both theory-building and practice. Case studies allow researchers to delve into the intricacies and complexities of real-life situations, uncovering insights that might otherwise remain hidden.

Types of case studies

In qualitative research , a case study is not a one-size-fits-all approach. Depending on the nature of the research question and the specific objectives of the study, researchers might choose to use different types of case studies. These types differ in their focus, methodology, and the level of detail they provide about the phenomenon under investigation.

Understanding these types is crucial for selecting the most appropriate approach for your research project and effectively achieving your research goals. Let's briefly look at the main types of case studies.

Exploratory case studies

Exploratory case studies are typically conducted to develop a theory or framework around an understudied phenomenon. They can also serve as a precursor to a larger-scale research project. Exploratory case studies are useful when a researcher wants to identify the key issues or questions which can spur more extensive study or be used to develop propositions for further research. These case studies are characterized by flexibility, allowing researchers to explore various aspects of a phenomenon as they emerge, which can also form the foundation for subsequent studies.

Descriptive case studies

Descriptive case studies aim to provide a complete and accurate representation of a phenomenon or event within its context. These case studies are often based on an established theoretical framework, which guides how data is collected and analyzed. The researcher is concerned with describing the phenomenon in detail, as it occurs naturally, without trying to influence or manipulate it.

Explanatory case studies

Explanatory case studies are focused on explanation - they seek to clarify how or why certain phenomena occur. Often used in complex, real-life situations, they can be particularly valuable in clarifying causal relationships among concepts and understanding the interplay between different factors within a specific context.

Intrinsic, instrumental, and collective case studies

These three categories of case studies focus on the nature and purpose of the study. An intrinsic case study is conducted when a researcher has an inherent interest in the case itself. Instrumental case studies are employed when the case is used to provide insight into a particular issue or phenomenon. A collective case study, on the other hand, involves studying multiple cases simultaneously to investigate some general phenomena.

Each type of case study serves a different purpose and has its own strengths and challenges. The selection of the type should be guided by the research question and objectives, as well as the context and constraints of the research.

The flexibility, depth, and contextual richness offered by case studies make this approach an excellent research method for various fields of study. They enable researchers to investigate real-world phenomena within their specific contexts, capturing nuances that other research methods might miss. Across numerous fields, case studies provide valuable insights into complex issues.

Critical information systems research

Case studies provide a detailed understanding of the role and impact of information systems in different contexts. They offer a platform to explore how information systems are designed, implemented, and used and how they interact with various social, economic, and political factors. Case studies in this field often focus on examining the intricate relationship between technology, organizational processes, and user behavior, helping to uncover insights that can inform better system design and implementation.

Health research

Health research is another field where case studies are highly valuable. They offer a way to explore patient experiences, healthcare delivery processes, and the impact of various interventions in a real-world context.

Case studies can provide a deep understanding of a patient's journey, giving insights into the intricacies of disease progression, treatment effects, and the psychosocial aspects of health and illness.

Asthma research studies

Specifically within medical research, studies on asthma often employ case studies to explore the individual and environmental factors that influence asthma development, management, and outcomes. A case study can provide rich, detailed data about individual patients' experiences, from the triggers and symptoms they experience to the effectiveness of various management strategies. This can be crucial for developing patient-centered asthma care approaches.

Other fields

Apart from the fields mentioned, case studies are also extensively used in business and management research, education research, and political sciences, among many others. They provide an opportunity to delve into the intricacies of real-world situations, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of various phenomena.

Case studies, with their depth and contextual focus, offer unique insights across these varied fields. They allow researchers to illuminate the complexities of real-life situations, contributing to both theory and practice.

Whatever field you're in, ATLAS.ti puts your data to work for you

Download a free trial of ATLAS.ti to turn your data into insights.

Understanding the key elements of case study design is crucial for conducting rigorous and impactful case study research. A well-structured design guides the researcher through the process, ensuring that the study is methodologically sound and its findings are reliable and valid. The main elements of case study design include the research question , propositions, units of analysis, and the logic linking the data to the propositions.

The research question is the foundation of any research study. A good research question guides the direction of the study and informs the selection of the case, the methods of collecting data, and the analysis techniques. A well-formulated research question in case study research is typically clear, focused, and complex enough to merit further detailed examination of the relevant case(s).

Propositions

Propositions, though not necessary in every case study, provide a direction by stating what we might expect to find in the data collected. They guide how data is collected and analyzed by helping researchers focus on specific aspects of the case. They are particularly important in explanatory case studies, which seek to understand the relationships among concepts within the studied phenomenon.

Units of analysis

The unit of analysis refers to the case, or the main entity or entities that are being analyzed in the study. In case study research, the unit of analysis can be an individual, a group, an organization, a decision, an event, or even a time period. It's crucial to clearly define the unit of analysis, as it shapes the qualitative data analysis process by allowing the researcher to analyze a particular case and synthesize analysis across multiple case studies to draw conclusions.

Argumentation

This refers to the inferential model that allows researchers to draw conclusions from the data. The researcher needs to ensure that there is a clear link between the data, the propositions (if any), and the conclusions drawn. This argumentation is what enables the researcher to make valid and credible inferences about the phenomenon under study.

Understanding and carefully considering these elements in the design phase of a case study can significantly enhance the quality of the research. It can help ensure that the study is methodologically sound and its findings contribute meaningful insights about the case.

Ready to jumpstart your research with ATLAS.ti?

Conceptualize your research project with our intuitive data analysis interface. Download a free trial today.

Conducting a case study involves several steps, from defining the research question and selecting the case to collecting and analyzing data . This section outlines these key stages, providing a practical guide on how to conduct case study research.

Defining the research question

The first step in case study research is defining a clear, focused research question. This question should guide the entire research process, from case selection to analysis. It's crucial to ensure that the research question is suitable for a case study approach. Typically, such questions are exploratory or descriptive in nature and focus on understanding a phenomenon within its real-life context.

Selecting and defining the case

The selection of the case should be based on the research question and the objectives of the study. It involves choosing a unique example or a set of examples that provide rich, in-depth data about the phenomenon under investigation. After selecting the case, it's crucial to define it clearly, setting the boundaries of the case, including the time period and the specific context.

Previous research can help guide the case study design. When considering a case study, an example of a case could be taken from previous case study research and used to define cases in a new research inquiry. Considering recently published examples can help understand how to select and define cases effectively.

Developing a detailed case study protocol

A case study protocol outlines the procedures and general rules to be followed during the case study. This includes the data collection methods to be used, the sources of data, and the procedures for analysis. Having a detailed case study protocol ensures consistency and reliability in the study.

The protocol should also consider how to work with the people involved in the research context to grant the research team access to collecting data. As mentioned in previous sections of this guide, establishing rapport is an essential component of qualitative research as it shapes the overall potential for collecting and analyzing data.

Collecting data

Gathering data in case study research often involves multiple sources of evidence, including documents, archival records, interviews, observations, and physical artifacts. This allows for a comprehensive understanding of the case. The process for gathering data should be systematic and carefully documented to ensure the reliability and validity of the study.

Analyzing and interpreting data

The next step is analyzing the data. This involves organizing the data , categorizing it into themes or patterns , and interpreting these patterns to answer the research question. The analysis might also involve comparing the findings with prior research or theoretical propositions.

Writing the case study report

The final step is writing the case study report . This should provide a detailed description of the case, the data, the analysis process, and the findings. The report should be clear, organized, and carefully written to ensure that the reader can understand the case and the conclusions drawn from it.

Each of these steps is crucial in ensuring that the case study research is rigorous, reliable, and provides valuable insights about the case.

The type, depth, and quality of data in your study can significantly influence the validity and utility of the study. In case study research, data is usually collected from multiple sources to provide a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case. This section will outline the various methods of collecting data used in case study research and discuss considerations for ensuring the quality of the data.

Interviews are a common method of gathering data in case study research. They can provide rich, in-depth data about the perspectives, experiences, and interpretations of the individuals involved in the case. Interviews can be structured , semi-structured , or unstructured , depending on the research question and the degree of flexibility needed.

Observations

Observations involve the researcher observing the case in its natural setting, providing first-hand information about the case and its context. Observations can provide data that might not be revealed in interviews or documents, such as non-verbal cues or contextual information.

Documents and artifacts

Documents and archival records provide a valuable source of data in case study research. They can include reports, letters, memos, meeting minutes, email correspondence, and various public and private documents related to the case.

These records can provide historical context, corroborate evidence from other sources, and offer insights into the case that might not be apparent from interviews or observations.

Physical artifacts refer to any physical evidence related to the case, such as tools, products, or physical environments. These artifacts can provide tangible insights into the case, complementing the data gathered from other sources.

Ensuring the quality of data collection

Determining the quality of data in case study research requires careful planning and execution. It's crucial to ensure that the data is reliable, accurate, and relevant to the research question. This involves selecting appropriate methods of collecting data, properly training interviewers or observers, and systematically recording and storing the data. It also includes considering ethical issues related to collecting and handling data, such as obtaining informed consent and ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of the participants.

Data analysis

Analyzing case study research involves making sense of the rich, detailed data to answer the research question. This process can be challenging due to the volume and complexity of case study data. However, a systematic and rigorous approach to analysis can ensure that the findings are credible and meaningful. This section outlines the main steps and considerations in analyzing data in case study research.

Organizing the data

The first step in the analysis is organizing the data. This involves sorting the data into manageable sections, often according to the data source or the theme. This step can also involve transcribing interviews, digitizing physical artifacts, or organizing observational data.

Categorizing and coding the data

Once the data is organized, the next step is to categorize or code the data. This involves identifying common themes, patterns, or concepts in the data and assigning codes to relevant data segments. Coding can be done manually or with the help of software tools, and in either case, qualitative analysis software can greatly facilitate the entire coding process. Coding helps to reduce the data to a set of themes or categories that can be more easily analyzed.

Identifying patterns and themes

After coding the data, the researcher looks for patterns or themes in the coded data. This involves comparing and contrasting the codes and looking for relationships or patterns among them. The identified patterns and themes should help answer the research question.

Interpreting the data

Once patterns and themes have been identified, the next step is to interpret these findings. This involves explaining what the patterns or themes mean in the context of the research question and the case. This interpretation should be grounded in the data, but it can also involve drawing on theoretical concepts or prior research.

Verification of the data

The last step in the analysis is verification. This involves checking the accuracy and consistency of the analysis process and confirming that the findings are supported by the data. This can involve re-checking the original data, checking the consistency of codes, or seeking feedback from research participants or peers.

Like any research method , case study research has its strengths and limitations. Researchers must be aware of these, as they can influence the design, conduct, and interpretation of the study.

Understanding the strengths and limitations of case study research can also guide researchers in deciding whether this approach is suitable for their research question . This section outlines some of the key strengths and limitations of case study research.

Benefits include the following:

- Rich, detailed data: One of the main strengths of case study research is that it can generate rich, detailed data about the case. This can provide a deep understanding of the case and its context, which can be valuable in exploring complex phenomena.

- Flexibility: Case study research is flexible in terms of design , data collection , and analysis . A sufficient degree of flexibility allows the researcher to adapt the study according to the case and the emerging findings.

- Real-world context: Case study research involves studying the case in its real-world context, which can provide valuable insights into the interplay between the case and its context.

- Multiple sources of evidence: Case study research often involves collecting data from multiple sources , which can enhance the robustness and validity of the findings.

On the other hand, researchers should consider the following limitations:

- Generalizability: A common criticism of case study research is that its findings might not be generalizable to other cases due to the specificity and uniqueness of each case.

- Time and resource intensive: Case study research can be time and resource intensive due to the depth of the investigation and the amount of collected data.

- Complexity of analysis: The rich, detailed data generated in case study research can make analyzing the data challenging.

- Subjectivity: Given the nature of case study research, there may be a higher degree of subjectivity in interpreting the data , so researchers need to reflect on this and transparently convey to audiences how the research was conducted.

Being aware of these strengths and limitations can help researchers design and conduct case study research effectively and interpret and report the findings appropriately.

Ready to analyze your data with ATLAS.ti?

See how our intuitive software can draw key insights from your data with a free trial today.

How to Write a Case Study: Bookmarkable Guide & Template

Published: November 30, 2023

Earning the trust of prospective customers can be a struggle. Before you can even begin to expect to earn their business, you need to demonstrate your ability to deliver on what your product or service promises.

Sure, you could say that you're great at X or that you're way ahead of the competition when it comes to Y. But at the end of the day, what you really need to win new business is cold, hard proof.

One of the best ways to prove your worth is through a compelling case study. In fact, HubSpot’s 2020 State of Marketing report found that case studies are so compelling that they are the fifth most commonly used type of content used by marketers.

Below, I'll walk you through what a case study is, how to prepare for writing one, what you need to include in it, and how it can be an effective tactic. To jump to different areas of this post, click on the links below to automatically scroll.

Case Study Definition

Case study templates, how to write a case study.

- How to Format a Case Study

Business Case Study Examples

A case study is a specific challenge a business has faced, and the solution they've chosen to solve it. Case studies can vary greatly in length and focus on several details related to the initial challenge and applied solution, and can be presented in various forms like a video, white paper, blog post, etc.

In professional settings, it's common for a case study to tell the story of a successful business partnership between a vendor and a client. Perhaps the success you're highlighting is in the number of leads your client generated, customers closed, or revenue gained. Any one of these key performance indicators (KPIs) are examples of your company's services in action.

When done correctly, these examples of your work can chronicle the positive impact your business has on existing or previous customers and help you attract new clients.

Free Case Study Templates

Showcase your company's success using these three free case study templates.

- Data-Driven Case Study Template

- Product-Specific Case Study Template

- General Case Study Template

Download Free

All fields are required.

You're all set!

Click this link to access this resource at any time.

Why write a case study?

I know, you’re thinking “ Okay, but why do I need to write one of these? ” The truth is that while case studies are a huge undertaking, they are powerful marketing tools that allow you to demonstrate the value of your product to potential customers using real-world examples. Here are a few reasons why you should write case studies.

1. Explain Complex Topics or Concepts

Case studies give you the space to break down complex concepts, ideas, and strategies and show how they can be applied in a practical way. You can use real-world examples, like an existing client, and use their story to create a compelling narrative that shows how your product solved their issue and how those strategies can be repeated to help other customers get similar successful results.

2. Show Expertise

Case studies are a great way to demonstrate your knowledge and expertise on a given topic or industry. This is where you get the opportunity to show off your problem-solving skills and how you’ve generated successful outcomes for clients you’ve worked with.

3. Build Trust and Credibility

In addition to showing off the attributes above, case studies are an excellent way to build credibility. They’re often filled with data and thoroughly researched, which shows readers you’ve done your homework. They can have confidence in the solutions you’ve presented because they’ve read through as you’ve explained the problem and outlined step-by-step what it took to solve it. All of these elements working together enable you to build trust with potential customers.

4. Create Social Proof

Using existing clients that have seen success working with your brand builds social proof . People are more likely to choose your brand if they know that others have found success working with you. Case studies do just that — putting your success on display for potential customers to see.

All of these attributes work together to help you gain more clients. Plus you can even use quotes from customers featured in these studies and repurpose them in other marketing content. Now that you know more about the benefits of producing a case study, let’s check out how long these documents should be.

How long should a case study be?

The length of a case study will vary depending on the complexity of the project or topic discussed. However, as a general guideline, case studies typically range from 500 to 1,500 words.

Whatever length you choose, it should provide a clear understanding of the challenge, the solution you implemented, and the results achieved. This may be easier said than done, but it's important to strike a balance between providing enough detail to make the case study informative and concise enough to keep the reader's interest.

The primary goal here is to effectively communicate the key points and takeaways of the case study. It’s worth noting that this shouldn’t be a wall of text. Use headings, subheadings, bullet points, charts, and other graphics to break up the content and make it more scannable for readers. We’ve also seen brands incorporate video elements into case studies listed on their site for a more engaging experience.

Ultimately, the length of your case study should be determined by the amount of information necessary to convey the story and its impact without becoming too long. Next, let’s look at some templates to take the guesswork out of creating one.

To help you arm your prospects with information they can trust, we've put together a step-by-step guide on how to create effective case studies for your business with free case study templates for creating your own.

Tell us a little about yourself below to gain access today:

And to give you more options, we’ll highlight some useful templates that serve different needs. But remember, there are endless possibilities when it comes to demonstrating the work your business has done.

1. General Case Study Template

Do you have a specific product or service that you’re trying to sell, but not enough reviews or success stories? This Product Specific case study template will help.

This template relies less on metrics, and more on highlighting the customer’s experience and satisfaction. As you follow the template instructions, you’ll be prompted to speak more about the benefits of the specific product, rather than your team’s process for working with the customer.

4. Bold Social Media Business Case Study Template

You can find templates that represent different niches, industries, or strategies that your business has found success in — like a bold social media business case study template.

In this template, you can tell the story of how your social media marketing strategy has helped you or your client through collaboration or sale of your service. Customize it to reflect the different marketing channels used in your business and show off how well your business has been able to boost traffic, engagement, follows, and more.

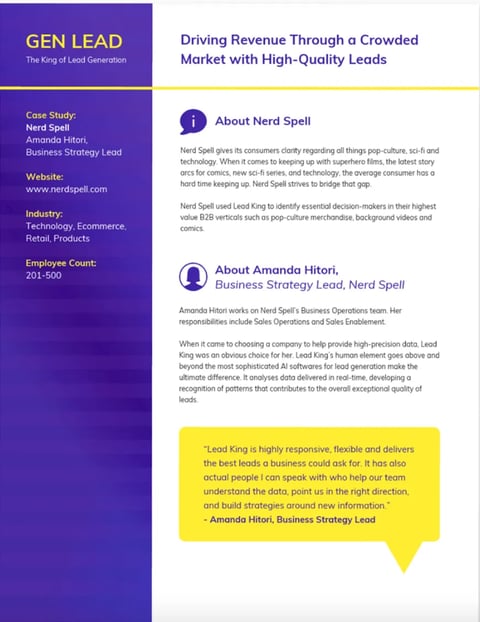

5. Lead Generation Business Case Study Template

It’s important to note that not every case study has to be the product of a sale or customer story, sometimes they can be informative lessons that your own business has experienced. A great example of this is the Lead Generation Business case study template.

If you’re looking to share operational successes regarding how your team has improved processes or content, you should include the stories of different team members involved, how the solution was found, and how it has made a difference in the work your business does.

Now that we’ve discussed different templates and ideas for how to use them, let’s break down how to create your own case study with one.

- Get started with case study templates.

- Determine the case study's objective.

- Establish a case study medium.

- Find the right case study candidate.

- Contact your candidate for permission to write about them.

- Ensure you have all the resources you need to proceed once you get a response.

- Download a case study email template.

- Define the process you want to follow with the client.

- Ensure you're asking the right questions.

- Layout your case study format.

- Publish and promote your case study.

1. Get started with case study templates.

Telling your customer's story is a delicate process — you need to highlight their success while naturally incorporating your business into their story.

If you're just getting started with case studies, we recommend you download HubSpot's Case Study Templates we mentioned before to kickstart the process.

2. Determine the case study's objective.

All business case studies are designed to demonstrate the value of your services, but they can focus on several different client objectives.

Your first step when writing a case study is to determine the objective or goal of the subject you're featuring. In other words, what will the client have succeeded in doing by the end of the piece?

The client objective you focus on will depend on what you want to prove to your future customers as a result of publishing this case study.

Your case study can focus on one of the following client objectives:

- Complying with government regulation

- Lowering business costs

- Becoming profitable

- Generating more leads

- Closing on more customers

- Generating more revenue

- Expanding into a new market

- Becoming more sustainable or energy-efficient

3. Establish a case study medium.

Next, you'll determine the medium in which you'll create the case study. In other words, how will you tell this story?

Case studies don't have to be simple, written one-pagers. Using different media in your case study can allow you to promote your final piece on different channels. For example, while a written case study might just live on your website and get featured in a Facebook post, you can post an infographic case study on Pinterest and a video case study on your YouTube channel.

Here are some different case study mediums to consider:

Written Case Study

Consider writing this case study in the form of an ebook and converting it to a downloadable PDF. Then, gate the PDF behind a landing page and form for readers to fill out before downloading the piece, allowing this case study to generate leads for your business.

Video Case Study

Plan on meeting with the client and shooting an interview. Seeing the subject, in person, talk about the service you provided them can go a long way in the eyes of your potential customers.

Infographic Case Study

Use the long, vertical format of an infographic to tell your success story from top to bottom. As you progress down the infographic, emphasize major KPIs using bigger text and charts that show the successes your client has had since working with you.

Podcast Case Study

Podcasts are a platform for you to have a candid conversation with your client. This type of case study can sound more real and human to your audience — they'll know the partnership between you and your client was a genuine success.

4. Find the right case study candidate.

Writing about your previous projects requires more than picking a client and telling a story. You need permission, quotes, and a plan. To start, here are a few things to look for in potential candidates.

Product Knowledge

It helps to select a customer who's well-versed in the logistics of your product or service. That way, he or she can better speak to the value of what you offer in a way that makes sense for future customers.

Remarkable Results

Clients that have seen the best results are going to make the strongest case studies. If their own businesses have seen an exemplary ROI from your product or service, they're more likely to convey the enthusiasm that you want prospects to feel, too.

One part of this step is to choose clients who have experienced unexpected success from your product or service. When you've provided non-traditional customers — in industries that you don't usually work with, for example — with positive results, it can help to remove doubts from prospects.

Recognizable Names

While small companies can have powerful stories, bigger or more notable brands tend to lend credibility to your own. In fact, 89% of consumers say they'll buy from a brand they already recognize over a competitor, especially if they already follow them on social media.

Customers that came to you after working with a competitor help highlight your competitive advantage and might even sway decisions in your favor.

5. Contact your candidate for permission to write about them.

To get the case study candidate involved, you have to set the stage for clear and open communication. That means outlining expectations and a timeline right away — not having those is one of the biggest culprits in delayed case study creation.

Most importantly at this point, however, is getting your subject's approval. When first reaching out to your case study candidate, provide them with the case study's objective and format — both of which you will have come up with in the first two steps above.

To get this initial permission from your subject, put yourself in their shoes — what would they want out of this case study? Although you're writing this for your own company's benefit, your subject is far more interested in the benefit it has for them.

Benefits to Offer Your Case Study Candidate

Here are four potential benefits you can promise your case study candidate to gain their approval.

Brand Exposure

Explain to your subject to whom this case study will be exposed, and how this exposure can help increase their brand awareness both in and beyond their own industry. In the B2B sector, brand awareness can be hard to collect outside one's own market, making case studies particularly useful to a client looking to expand their name's reach.

Employee Exposure

Allow your subject to provide quotes with credits back to specific employees. When this is an option for them, their brand isn't the only thing expanding its reach — their employees can get their name out there, too. This presents your subject with networking and career development opportunities they might not have otherwise.

Product Discount

This is a more tangible incentive you can offer your case study candidate, especially if they're a current customer of yours. If they agree to be your subject, offer them a product discount — or a free trial of another product — as a thank-you for their help creating your case study.

Backlinks and Website Traffic

Here's a benefit that is sure to resonate with your subject's marketing team: If you publish your case study on your website, and your study links back to your subject's website — known as a "backlink" — this small gesture can give them website traffic from visitors who click through to your subject's website.

Additionally, a backlink from you increases your subject's page authority in the eyes of Google. This helps them rank more highly in search engine results and collect traffic from readers who are already looking for information about their industry.

6. Ensure you have all the resources you need to proceed once you get a response.

So you know what you’re going to offer your candidate, it’s time that you prepare the resources needed for if and when they agree to participate, like a case study release form and success story letter.

Let's break those two down.

Case Study Release Form

This document can vary, depending on factors like the size of your business, the nature of your work, and what you intend to do with the case studies once they are completed. That said, you should typically aim to include the following in the Case Study Release Form:

- A clear explanation of why you are creating this case study and how it will be used.

- A statement defining the information and potentially trademarked information you expect to include about the company — things like names, logos, job titles, and pictures.

- An explanation of what you expect from the participant, beyond the completion of the case study. For example, is this customer willing to act as a reference or share feedback, and do you have permission to pass contact information along for these purposes?

- A note about compensation.

Success Story Letter

As noted in the sample email, this document serves as an outline for the entire case study process. Other than a brief explanation of how the customer will benefit from case study participation, you'll want to be sure to define the following steps in the Success Story Letter.

7. Download a case study email template.

While you gathered your resources, your candidate has gotten time to read over the proposal. When your candidate approves of your case study, it's time to send them a release form.

A case study release form tells you what you'll need from your chosen subject, like permission to use any brand names and share the project information publicly. Kick-off this process with an email that runs through exactly what they can expect from you, as well as what you need from them. To give you an idea of what that might look like, check out this sample email:

8. Define the process you want to follow with the client.

Before you can begin the case study, you have to have a clear outline of the case study process with your client. An example of an effective outline would include the following information.

The Acceptance

First, you'll need to receive internal approval from the company's marketing team. Once approved, the Release Form should be signed and returned to you. It's also a good time to determine a timeline that meets the needs and capabilities of both teams.

The Questionnaire

To ensure that you have a productive interview — which is one of the best ways to collect information for the case study — you'll want to ask the participant to complete a questionnaire before this conversation. That will provide your team with the necessary foundation to organize the interview, and get the most out of it.

The Interview

Once the questionnaire is completed, someone on your team should reach out to the participant to schedule a 30- to 60-minute interview, which should include a series of custom questions related to the customer's experience with your product or service.

The Draft Review

After the case study is composed, you'll want to send a draft to the customer, allowing an opportunity to give you feedback and edits.

The Final Approval

Once any necessary edits are completed, send a revised copy of the case study to the customer for final approval.

Once the case study goes live — on your website or elsewhere — it's best to contact the customer with a link to the page where the case study lives. Don't be afraid to ask your participants to share these links with their own networks, as it not only demonstrates your ability to deliver positive results and impressive growth, as well.

9. Ensure you're asking the right questions.

Before you execute the questionnaire and actual interview, make sure you're setting yourself up for success. A strong case study results from being prepared to ask the right questions. What do those look like? Here are a few examples to get you started:

- What are your goals?

- What challenges were you experiencing before purchasing our product or service?

- What made our product or service stand out against our competitors?

- What did your decision-making process look like?

- How have you benefited from using our product or service? (Where applicable, always ask for data.)

Keep in mind that the questionnaire is designed to help you gain insights into what sort of strong, success-focused questions to ask during the actual interview. And once you get to that stage, we recommend that you follow the "Golden Rule of Interviewing." Sounds fancy, right? It's actually quite simple — ask open-ended questions.

If you're looking to craft a compelling story, "yes" or "no" answers won't provide the details you need. Focus on questions that invite elaboration, such as, "Can you describe ...?" or, "Tell me about ..."

In terms of the interview structure, we recommend categorizing the questions and flowing them into six specific sections that will mirror a successful case study format. Combined, they'll allow you to gather enough information to put together a rich, comprehensive study.

Open with the customer's business.

The goal of this section is to generate a better understanding of the company's current challenges and goals, and how they fit into the landscape of their industry. Sample questions might include:

- How long have you been in business?

- How many employees do you have?

- What are some of the objectives of your department at this time?

Cite a problem or pain point.

To tell a compelling story, you need context. That helps match the customer's need with your solution. Sample questions might include:

- What challenges and objectives led you to look for a solution?

- What might have happened if you did not identify a solution?

- Did you explore other solutions before this that did not work out? If so, what happened?

Discuss the decision process.

Exploring how the customer decided to work with you helps to guide potential customers through their own decision-making processes. Sample questions might include:

- How did you hear about our product or service?

- Who was involved in the selection process?

- What was most important to you when evaluating your options?

Explain how a solution was implemented.

The focus here should be placed on the customer's experience during the onboarding process. Sample questions might include:

- How long did it take to get up and running?

- Did that meet your expectations?

- Who was involved in the process?

Explain how the solution works.

The goal of this section is to better understand how the customer is using your product or service. Sample questions might include:

- Is there a particular aspect of the product or service that you rely on most?

- Who is using the product or service?

End with the results.

In this section, you want to uncover impressive measurable outcomes — the more numbers, the better. Sample questions might include:

- How is the product or service helping you save time and increase productivity?

- In what ways does that enhance your competitive advantage?

- How much have you increased metrics X, Y, and Z?

10. Lay out your case study format.

When it comes time to take all of the information you've collected and actually turn it into something, it's easy to feel overwhelmed. Where should you start? What should you include? What's the best way to structure it?

To help you get a handle on this step, it's important to first understand that there is no one-size-fits-all when it comes to the ways you can present a case study. They can be very visual, which you'll see in some of the examples we've included below, and can sometimes be communicated mostly through video or photos, with a bit of accompanying text.

Here are the sections we suggest, which we'll cover in more detail down below:

- Title: Keep it short. Develop a succinct but interesting project name you can give the work you did with your subject.

- Subtitle: Use this copy to briefly elaborate on the accomplishment. What was done? The case study itself will explain how you got there.

- Executive Summary : A 2-4 sentence summary of the entire story. You'll want to follow it with 2-3 bullet points that display metrics showcasing success.

- About the Subject: An introduction to the person or company you served, which can be pulled from a LinkedIn Business profile or client website.

- Challenges and Objectives: A 2-3 paragraph description of the customer's challenges, before using your product or service. This section should also include the goals or objectives the customer set out to achieve.

- How Product/Service Helped: A 2-3 paragraph section that describes how your product or service provided a solution to their problem.

- Results: A 2-3 paragraph testimonial that proves how your product or service specifically benefited the person or company and helped achieve its goals. Include numbers to quantify your contributions.

- Supporting Visuals or Quotes: Pick one or two powerful quotes that you would feature at the bottom of the sections above, as well as a visual that supports the story you are telling.

- Future Plans: Everyone likes an epilogue. Comment on what's ahead for your case study subject, whether or not those plans involve you.

- Call to Action (CTA): Not every case study needs a CTA, but putting a passive one at the end of your case study can encourage your readers to take an action on your website after learning about the work you've done.

When laying out your case study, focus on conveying the information you've gathered in the most clear and concise way possible. Make it easy to scan and comprehend, and be sure to provide an attractive call-to-action at the bottom — that should provide readers an opportunity to learn more about your product or service.

11. Publish and promote your case study.

Once you've completed your case study, it's time to publish and promote it. Some case study formats have pretty obvious promotional outlets — a video case study can go on YouTube, just as an infographic case study can go on Pinterest.

But there are still other ways to publish and promote your case study. Here are a couple of ideas:

Lead Gen in a Blog Post

As stated earlier in this article, written case studies make terrific lead-generators if you convert them into a downloadable format, like a PDF. To generate leads from your case study, consider writing a blog post that tells an abbreviated story of your client's success and asking readers to fill out a form with their name and email address if they'd like to read the rest in your PDF.

Then, promote this blog post on social media, through a Facebook post or a tweet.

Published as a Page on Your Website

As a growing business, you might need to display your case study out in the open to gain the trust of your target audience.

Rather than gating it behind a landing page, publish your case study to its own page on your website, and direct people here from your homepage with a "Case Studies" or "Testimonials" button along your homepage's top navigation bar.

Format for a Case Study

The traditional case study format includes the following parts: a title and subtitle, a client profile, a summary of the customer’s challenges and objectives, an account of how your solution helped, and a description of the results. You might also want to include supporting visuals and quotes, future plans, and calls-to-action.

Image Source

The title is one of the most important parts of your case study. It should draw readers in while succinctly describing the potential benefits of working with your company. To that end, your title should:

- State the name of your custome r. Right away, the reader must learn which company used your products and services. This is especially important if your customer has a recognizable brand. If you work with individuals and not companies, you may omit the name and go with professional titles: “A Marketer…”, “A CFO…”, and so forth.

- State which product your customer used . Even if you only offer one product or service, or if your company name is the same as your product name, you should still include the name of your solution. That way, readers who are not familiar with your business can become aware of what you sell.

- Allude to the results achieved . You don’t necessarily need to provide hard numbers, but the title needs to represent the benefits, quickly. That way, if a reader doesn’t stay to read, they can walk away with the most essential information: Your product works.

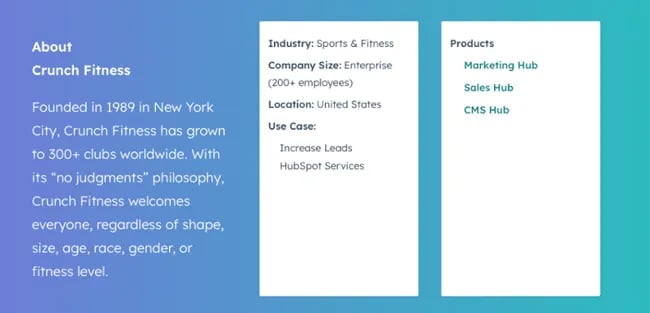

The example above, “Crunch Fitness Increases Leads and Signups With HubSpot,” achieves all three — without being wordy. Keeping your title short and sweet is also essential.

2. Subtitle

Your subtitle is another essential part of your case study — don’t skip it, even if you think you’ve done the work with the title. In this section, include a brief summary of the challenges your customer was facing before they began to use your products and services. Then, drive the point home by reiterating the benefits your customer experienced by working with you.

The above example reads:

“Crunch Fitness was franchising rapidly when COVID-19 forced fitness clubs around the world to close their doors. But the company stayed agile by using HubSpot to increase leads and free trial signups.”

We like that the case study team expressed the urgency of the problem — opening more locations in the midst of a pandemic — and placed the focus on the customer’s ability to stay agile.

3. Executive Summary

The executive summary should provide a snapshot of your customer, their challenges, and the benefits they enjoyed from working with you. Think it’s too much? Think again — the purpose of the case study is to emphasize, again and again, how well your product works.

The good news is that depending on your design, the executive summary can be mixed with the subtitle or with the “About the Company” section. Many times, this section doesn’t need an explicit “Executive Summary” subheading. You do need, however, to provide a convenient snapshot for readers to scan.

In the above example, ADP included information about its customer in a scannable bullet-point format, then provided two sections: “Business Challenge” and “How ADP Helped.” We love how simple and easy the format is to follow for those who are unfamiliar with ADP or its typical customer.

4. About the Company

Readers need to know and understand who your customer is. This is important for several reasons: It helps your reader potentially relate to your customer, it defines your ideal client profile (which is essential to deter poor-fit prospects who might have reached out without knowing they were a poor fit), and it gives your customer an indirect boon by subtly promoting their products and services.

Feel free to keep this section as simple as possible. You can simply copy and paste information from the company’s LinkedIn, use a quote directly from your customer, or take a more creative storytelling approach.

In the above example, HubSpot included one paragraph of description for Crunch Fitness and a few bullet points. Below, ADP tells the story of its customer using an engaging, personable technique that effectively draws readers in.

5. Challenges and Objectives

The challenges and objectives section of your case study is the place to lay out, in detail, the difficulties your customer faced prior to working with you — and what they hoped to achieve when they enlisted your help.

In this section, you can be as brief or as descriptive as you’d like, but remember: Stress the urgency of the situation. Don’t understate how much your customer needed your solution (but don’t exaggerate and lie, either). Provide contextual information as necessary. For instance, the pandemic and societal factors may have contributed to the urgency of the need.

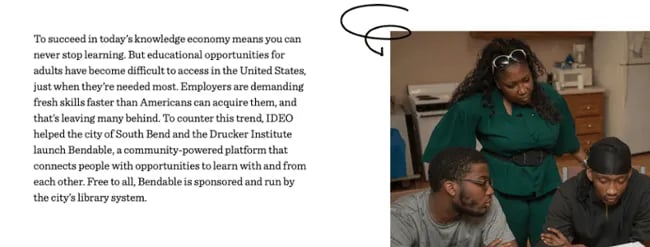

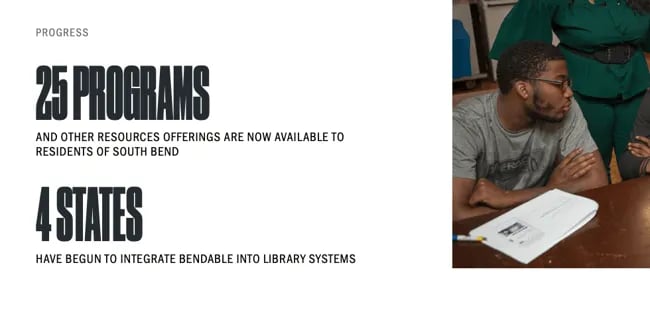

Take the above example from design consultancy IDEO:

“Educational opportunities for adults have become difficult to access in the United States, just when they’re needed most. To counter this trend, IDEO helped the city of South Bend and the Drucker Institute launch Bendable, a community-powered platform that connects people with opportunities to learn with and from each other.”

We love how IDEO mentions the difficulties the United States faces at large, the efforts its customer is taking to address these issues, and the steps IDEO took to help.

6. How Product/Service Helped

This is where you get your product or service to shine. Cover the specific benefits that your customer enjoyed and the features they gleaned the most use out of. You can also go into detail about how you worked with and for your customer. Maybe you met several times before choosing the right solution, or you consulted with external agencies to create the best package for them.

Whatever the case may be, try to illustrate how easy and pain-free it is to work with the representatives at your company. After all, potential customers aren’t looking to just purchase a product. They’re looking for a dependable provider that will strive to exceed their expectations.

In the above example, IDEO describes how it partnered with research institutes and spoke with learners to create Bendable, a free educational platform. We love how it shows its proactivity and thoroughness. It makes potential customers feel that IDEO might do something similar for them.

The results are essential, and the best part is that you don’t need to write the entirety of the case study before sharing them. Like HubSpot, IDEO, and ADP, you can include the results right below the subtitle or executive summary. Use data and numbers to substantiate the success of your efforts, but if you don’t have numbers, you can provide quotes from your customers.

We can’t overstate the importance of the results. In fact, if you wanted to create a short case study, you could include your title, challenge, solution (how your product helped), and result.

8. Supporting Visuals or Quotes

Let your customer speak for themselves by including quotes from the representatives who directly interfaced with your company.

Visuals can also help, even if they’re stock images. On one side, they can help you convey your customer’s industry, and on the other, they can indirectly convey your successes. For instance, a picture of a happy professional — even if they’re not your customer — will communicate that your product can lead to a happy client.

In this example from IDEO, we see a man standing in a boat. IDEO’s customer is neither the man pictured nor the manufacturer of the boat, but rather Conservation International, an environmental organization. This imagery provides a visually pleasing pattern interrupt to the page, while still conveying what the case study is about.

9. Future Plans

This is optional, but including future plans can help you close on a more positive, personable note than if you were to simply include a quote or the results. In this space, you can show that your product will remain in your customer’s tech stack for years to come, or that your services will continue to be instrumental to your customer’s success.

Alternatively, if you work only on time-bound projects, you can allude to the positive impact your customer will continue to see, even after years of the end of the contract.

10. Call to Action (CTA)

Not every case study needs a CTA, but we’d still encourage it. Putting one at the end of your case study will encourage your readers to take an action on your website after learning about the work you've done.

It will also make it easier for them to reach out, if they’re ready to start immediately. You don’t want to lose business just because they have to scroll all the way back up to reach out to your team.

To help you visualize this case study outline, check out the case study template below, which can also be downloaded here .

You drove the results, made the connection, set the expectations, used the questionnaire to conduct a successful interview, and boiled down your findings into a compelling story. And after all of that, you're left with a little piece of sales enabling gold — a case study.

To show you what a well-executed final product looks like, have a look at some of these marketing case study examples.

1. "Shopify Uses HubSpot CRM to Transform High Volume Sales Organization," by HubSpot

What's interesting about this case study is the way it leads with the customer. This reflects a major HubSpot value, which is to always solve for the customer first. The copy leads with a brief description of why Shopify uses HubSpot and is accompanied by a short video and some basic statistics on the company.

Notice that this case study uses mixed media. Yes, there is a short video, but it's elaborated upon in the additional text on the page. So, while case studies can use one or the other, don't be afraid to combine written copy with visuals to emphasize the project's success.

2. "New England Journal of Medicine," by Corey McPherson Nash

When branding and design studio Corey McPherson Nash showcases its work, it makes sense for it to be visual — after all, that's what they do. So in building the case study for the studio's work on the New England Journal of Medicine's integrated advertising campaign — a project that included the goal of promoting the client's digital presence — Corey McPherson Nash showed its audience what it did, rather than purely telling it.

Notice that the case study does include some light written copy — which includes the major points we've suggested — but lets the visuals do the talking, allowing users to really absorb the studio's services.

3. "Designing the Future of Urban Farming," by IDEO

Here's a design company that knows how to lead with simplicity in its case studies. As soon as the visitor arrives at the page, he or she is greeted with a big, bold photo, and two very simple columns of text — "The Challenge" and "The Outcome."

Immediately, IDEO has communicated two of the case study's major pillars. And while that's great — the company created a solution for vertical farming startup INFARM's challenge — it doesn't stop there. As the user scrolls down, those pillars are elaborated upon with comprehensive (but not overwhelming) copy that outlines what that process looked like, replete with quotes and additional visuals.

4. "Secure Wi-Fi Wins Big for Tournament," by WatchGuard

Then, there are the cases when visuals can tell almost the entire story — when executed correctly. Network security provider WatchGuard can do that through this video, which tells the story of how its services enhanced the attendee and vendor experience at the Windmill Ultimate Frisbee tournament.

5. Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Boosts Social Media Engagement and Brand Awareness with HubSpot

In the case study above , HubSpot uses photos, videos, screenshots, and helpful stats to tell the story of how the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame used the bot, CRM, and social media tools to gain brand awareness.

6. Small Desk Plant Business Ups Sales by 30% With Trello

This case study from Trello is straightforward and easy to understand. It begins by explaining the background of the company that decided to use it, what its goals were, and how it planned to use Trello to help them.

It then goes on to discuss how the software was implemented and what tasks and teams benefited from it. Towards the end, it explains the sales results that came from implementing the software and includes quotes from decision-makers at the company that implemented it.

7. Facebook's Mercedes Benz Success Story

Facebook's Success Stories page hosts a number of well-designed and easy-to-understand case studies that visually and editorially get to the bottom line quickly.

Each study begins with key stats that draw the reader in. Then it's organized by highlighting a problem or goal in the introduction, the process the company took to reach its goals, and the results. Then, in the end, Facebook notes the tools used in the case study.

Showcasing Your Work

You work hard at what you do. Now, it's time to show it to the world — and, perhaps more important, to potential customers. Before you show off the projects that make you the proudest, we hope you follow these important steps that will help you effectively communicate that work and leave all parties feeling good about it.

Editor's Note: This blog post was originally published in February 2017 but was updated for comprehensiveness and freshness in July 2021.

Don't forget to share this post!

Related articles.

![case study 1 12 7 Pieces of Content Your Audience Really Wants to See [New Data]](https://blog.hubspot.com/hubfs/contenttypes.webp)

7 Pieces of Content Your Audience Really Wants to See [New Data]

How to Market an Ebook: 21 Ways to Promote Your Content Offers

![case study 1 12 How to Write a Listicle [+ Examples and Ideas]](https://blog.hubspot.com/hubfs/listicle-1.jpg)

How to Write a Listicle [+ Examples and Ideas]

28 Case Study Examples Every Marketer Should See

![case study 1 12 What Is a White Paper? [FAQs]](https://blog.hubspot.com/hubfs/business%20whitepaper.jpg)

What Is a White Paper? [FAQs]

What is an Advertorial? 8 Examples to Help You Write One

How to Create Marketing Offers That Don't Fall Flat

20 Creative Ways To Repurpose Content

16 Important Ways to Use Case Studies in Your Marketing

11 Ways to Make Your Blog Post Interactive

Showcase your company's success using these free case study templates.

Marketing software that helps you drive revenue, save time and resources, and measure and optimize your investments — all on one easy-to-use platform

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

A case study research paper examines a person, place, event, condition, phenomenon, or other type of subject of analysis in order to extrapolate key themes and results that help predict future trends, illuminate previously hidden issues that can be applied to practice, and/or provide a means for understanding an important research problem with greater clarity. A case study research paper usually examines a single subject of analysis, but case study papers can also be designed as a comparative investigation that shows relationships between two or more subjects. The methods used to study a case can rest within a quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-method investigative paradigm.

Case Studies. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010 ; “What is a Case Study?” In Swanborn, Peter G. Case Study Research: What, Why and How? London: SAGE, 2010.

How to Approach Writing a Case Study Research Paper

General information about how to choose a topic to investigate can be found under the " Choosing a Research Problem " tab in the Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper writing guide. Review this page because it may help you identify a subject of analysis that can be investigated using a case study design.

However, identifying a case to investigate involves more than choosing the research problem . A case study encompasses a problem contextualized around the application of in-depth analysis, interpretation, and discussion, often resulting in specific recommendations for action or for improving existing conditions. As Seawright and Gerring note, practical considerations such as time and access to information can influence case selection, but these issues should not be the sole factors used in describing the methodological justification for identifying a particular case to study. Given this, selecting a case includes considering the following:

- The case represents an unusual or atypical example of a research problem that requires more in-depth analysis? Cases often represent a topic that rests on the fringes of prior investigations because the case may provide new ways of understanding the research problem. For example, if the research problem is to identify strategies to improve policies that support girl's access to secondary education in predominantly Muslim nations, you could consider using Azerbaijan as a case study rather than selecting a more obvious nation in the Middle East. Doing so may reveal important new insights into recommending how governments in other predominantly Muslim nations can formulate policies that support improved access to education for girls.

- The case provides important insight or illuminate a previously hidden problem? In-depth analysis of a case can be based on the hypothesis that the case study will reveal trends or issues that have not been exposed in prior research or will reveal new and important implications for practice. For example, anecdotal evidence may suggest drug use among homeless veterans is related to their patterns of travel throughout the day. Assuming prior studies have not looked at individual travel choices as a way to study access to illicit drug use, a case study that observes a homeless veteran could reveal how issues of personal mobility choices facilitate regular access to illicit drugs. Note that it is important to conduct a thorough literature review to ensure that your assumption about the need to reveal new insights or previously hidden problems is valid and evidence-based.

- The case challenges and offers a counter-point to prevailing assumptions? Over time, research on any given topic can fall into a trap of developing assumptions based on outdated studies that are still applied to new or changing conditions or the idea that something should simply be accepted as "common sense," even though the issue has not been thoroughly tested in current practice. A case study analysis may offer an opportunity to gather evidence that challenges prevailing assumptions about a research problem and provide a new set of recommendations applied to practice that have not been tested previously. For example, perhaps there has been a long practice among scholars to apply a particular theory in explaining the relationship between two subjects of analysis. Your case could challenge this assumption by applying an innovative theoretical framework [perhaps borrowed from another discipline] to explore whether this approach offers new ways of understanding the research problem. Taking a contrarian stance is one of the most important ways that new knowledge and understanding develops from existing literature.

- The case provides an opportunity to pursue action leading to the resolution of a problem? Another way to think about choosing a case to study is to consider how the results from investigating a particular case may result in findings that reveal ways in which to resolve an existing or emerging problem. For example, studying the case of an unforeseen incident, such as a fatal accident at a railroad crossing, can reveal hidden issues that could be applied to preventative measures that contribute to reducing the chance of accidents in the future. In this example, a case study investigating the accident could lead to a better understanding of where to strategically locate additional signals at other railroad crossings so as to better warn drivers of an approaching train, particularly when visibility is hindered by heavy rain, fog, or at night.

- The case offers a new direction in future research? A case study can be used as a tool for an exploratory investigation that highlights the need for further research about the problem. A case can be used when there are few studies that help predict an outcome or that establish a clear understanding about how best to proceed in addressing a problem. For example, after conducting a thorough literature review [very important!], you discover that little research exists showing the ways in which women contribute to promoting water conservation in rural communities of east central Africa. A case study of how women contribute to saving water in a rural village of Uganda can lay the foundation for understanding the need for more thorough research that documents how women in their roles as cooks and family caregivers think about water as a valuable resource within their community. This example of a case study could also point to the need for scholars to build new theoretical frameworks around the topic [e.g., applying feminist theories of work and family to the issue of water conservation].

Eisenhardt, Kathleen M. “Building Theories from Case Study Research.” Academy of Management Review 14 (October 1989): 532-550; Emmel, Nick. Sampling and Choosing Cases in Qualitative Research: A Realist Approach . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2013; Gerring, John. “What Is a Case Study and What Is It Good for?” American Political Science Review 98 (May 2004): 341-354; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010; Seawright, Jason and John Gerring. "Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research." Political Research Quarterly 61 (June 2008): 294-308.

Structure and Writing Style

The purpose of a paper in the social sciences designed around a case study is to thoroughly investigate a subject of analysis in order to reveal a new understanding about the research problem and, in so doing, contributing new knowledge to what is already known from previous studies. In applied social sciences disciplines [e.g., education, social work, public administration, etc.], case studies may also be used to reveal best practices, highlight key programs, or investigate interesting aspects of professional work.

In general, the structure of a case study research paper is not all that different from a standard college-level research paper. However, there are subtle differences you should be aware of. Here are the key elements to organizing and writing a case study research paper.

I. Introduction

As with any research paper, your introduction should serve as a roadmap for your readers to ascertain the scope and purpose of your study . The introduction to a case study research paper, however, should not only describe the research problem and its significance, but you should also succinctly describe why the case is being used and how it relates to addressing the problem. The two elements should be linked. With this in mind, a good introduction answers these four questions:

- What is being studied? Describe the research problem and describe the subject of analysis [the case] you have chosen to address the problem. Explain how they are linked and what elements of the case will help to expand knowledge and understanding about the problem.

- Why is this topic important to investigate? Describe the significance of the research problem and state why a case study design and the subject of analysis that the paper is designed around is appropriate in addressing the problem.

- What did we know about this topic before I did this study? Provide background that helps lead the reader into the more in-depth literature review to follow. If applicable, summarize prior case study research applied to the research problem and why it fails to adequately address the problem. Describe why your case will be useful. If no prior case studies have been used to address the research problem, explain why you have selected this subject of analysis.

- How will this study advance new knowledge or new ways of understanding? Explain why your case study will be suitable in helping to expand knowledge and understanding about the research problem.

Each of these questions should be addressed in no more than a few paragraphs. Exceptions to this can be when you are addressing a complex research problem or subject of analysis that requires more in-depth background information.

II. Literature Review

The literature review for a case study research paper is generally structured the same as it is for any college-level research paper. The difference, however, is that the literature review is focused on providing background information and enabling historical interpretation of the subject of analysis in relation to the research problem the case is intended to address . This includes synthesizing studies that help to:

- Place relevant works in the context of their contribution to understanding the case study being investigated . This would involve summarizing studies that have used a similar subject of analysis to investigate the research problem. If there is literature using the same or a very similar case to study, you need to explain why duplicating past research is important [e.g., conditions have changed; prior studies were conducted long ago, etc.].

- Describe the relationship each work has to the others under consideration that informs the reader why this case is applicable . Your literature review should include a description of any works that support using the case to investigate the research problem and the underlying research questions.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research using the case study . If applicable, review any research that has examined the research problem using a different research design. Explain how your use of a case study design may reveal new knowledge or a new perspective or that can redirect research in an important new direction.