Case Studies of Challenges in Emergency Care for Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder

Affiliations.

- 1 From the Division of Emergency Medicine, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH.

- 2 Department of Pediatrics, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, CO.

- PMID: 32205797

- DOI: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000002074

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) affects more than 1% of children in the United States, with the rate of new diagnoses climbing significantly in the last 15 years. Emergent conditions and subsequent visits to the emergency department (ED) can be particularly challenging for children with ASD, most of whom also have comorbidities in addition to their deficits in social communication and interaction. In the emergency setting, these conditions can cause a range of behaviors that result in challenges for health care providers and may result in suboptimal experiences for children with ASD and their families. We present the ED course of 3 children with ASD to illustrate these challenges, emphasize successful strategies, and highlight opportunities for improvement.

Copyright © 2020 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

- Autism Spectrum Disorder* / epidemiology

- Autism Spectrum Disorder* / therapy

- Comorbidity

- Emergency Medical Services*

- Emergency Service, Hospital

- Emergency Treatment

- United States

Case Reports in Autism

Loading... Editorial 23 January 2024 Editorial: Case reports in autism Marco Colizzi and Fengyu Zhang 516 views 0 citations

Case Report 05 January 2024 Successful perioperative preparation of a child with autism spectrum disorder in collaboration with his school for special needs education: a case report Yuto Arai , 2 more and Yoshihiro Maegaki 1,180 views 0 citations

Community Case Study 02 November 2023 An individual-supported program to enhance placement in a sheltered work environment of autistic individuals mostly with intellectual disability: a prospective observational case series in an Italian community service Roberta Maggio , 7 more and Francesca Cucinotta 1,119 views 0 citations

Case Report 29 September 2023 Case Report: A playful digital-analogical rehabilitative intervention to enhance working memory capacity and executive functions in a pre-school child with autism Sabrina Panesi , 1 more and Lucia Ferlino 1,443 views 0 citations

Case Report 24 August 2023 Autism spectrum disorder and Coffin–Siris syndrome—Case report Luka Milutinovic , 4 more and Milica Pejovic Milovancevic 1,705 views 1 citations

Case Report 21 August 2023 Case report: A novel frameshift mutation in BRSK2 causes autism in a 16-year old Chinese boy Yu Hu , 7 more and Lixin Yang 1,308 views 1 citations

Case Report 18 August 2023 Case report: Substantial improvement of autism spectrum disorder in a child with learning disabilities in conjunction with treatment for poly-microbial vector borne infections Amy Offutt and Edward B. Breitschwerdt 7,782 views 0 citations

Case Report 17 August 2023 Fecal microbiota transplantation in a child with severe ASD comorbidities of gastrointestinal dysfunctions—a case report Cong Hu , 8 more and Yan Hao 1,304 views 0 citations

Case Report 28 July 2023 Autism spectrum disorder, very-early onset schizophrenia, and child disintegrative disorder: the challenge of diagnosis. A case-report study Michelangelo Di Luzio , 5 more and Stefano Vicari 2,339 views 1 citations

Case Report 19 June 2023 Case report: An evaluation of early motor skills in an infant later diagnosed with autism Lauren G. Malachowski , 1 more and Amy Work Needham 1,646 views 0 citations

Case Report 03 May 2023 Case report: Preemptive intervention for an infant with early signs of autism spectrum disorder during the first year of life Costanza Colombi , 7 more and Annarita Contaldo 4,235 views 2 citations

Case Report 26 April 2023 Case report: Treatment-resistant depression, multiple trauma exposure and suicidality in an adolescent female with previously undiagnosed Autism Spectrum Disorder Ilaria Secci , 5 more and Marco Armando 4,080 views 2 citations

Loading... Community Case Study 30 November 2022 A case study on the effect of light and colors in the built environment on autistic children’s behavior Ashwini Sunil Nair , 7 more and Xiaowei Zuo 10,972 views 7 citations

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 29 May 2024

A case–control study on pre-, peri-, and neonatal risk factors associated with autism spectrum disorder among Armenian children

- Meri Mkhitaryan 1 ,

- Tamara Avetisyan 2 , 3 ,

- Anna Mkhoyan 4 ,

- Larisa Avetisyan 2 , 5 &

- Konstantin Yenkoyan 1

Scientific Reports volume 14 , Article number: 12308 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

- Autism spectrum disorders

- Public health

- Risk factors

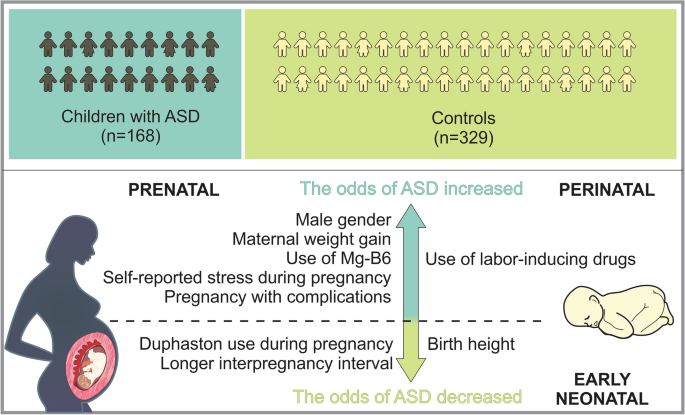

We aimed to investigate the role of pre-, peri- and neonatal risk factors in the development of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) among Armenian children with the goal of detecting and addressing modifiable risk factors to reduce ASD incidence. For this purpose a retrospective case–control study using a random proportional sample of Armenian children with ASD to assess associations between various factors and ASD was conducted. The study was approved by the local ethical committee, and parental written consent was obtained. A total of 168 children with ASD and 329 controls were included in the analysis. Multivariable logistic regression analysis revealed that male gender, maternal weight gain, use of MgB6, self-reported stress during the pregnancy, pregnancy with complications, as well as use of labor-inducing drugs were associated with a significant increase in the odds of ASD, whereas Duphaston use during pregnancy, the longer interpregnancy interval and birth height were associated with decreased odds of ASD. These findings are pertinent as many identified factors may be preventable or modifiable, underscoring the importance of timely and appropriate public health strategies aimed at disease prevention in pregnant women to reduce ASD incidence.

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder is a neurodevelopmental disorder by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the 5th Edition (DSM-5). It is identified by limited repeating patterns of behavior, activities, and interests, as well as impaired social interaction and communication 1 . A systematic review of research articles spanning from 2012 to 2021 indicates that the worldwide median prevalence of ASD in children stands at 1% 2 . Nevertheless, this reported percentage may not fully capture the actual prevalence of ASD in low- and middle-income nations, potentially leading to underestimations. In 2016, data compiled by the CDC's Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) Network revealed that approximately one out of 54 children in the United States (one out of 34 boys and one out of 144 girls) received a diagnosis of ASD. This marks a ten percent increase from the reported rate of one out of 59 in 2014, a 105 percent increase from one out of 110 in 2006, and a 176 percent increase from one out of 150 in 2000 3 . According to the most recent update from the CDC’s ADDM Network, one out of 36 (2.8%) 8-year-old children has been diagnosed with ASD. These latest statistics exceed the 2018 findings, which indicated a rate of 1 in 44 (2.3%) 4 . To our understanding, there is no existing registry for ASD in the Republic of Armenia (RA). Additionally, there is no available data concerning the incidence and prevalence of ASD in the country.

The etiology of ASD remains unclear despite substantial research on the disorder; yet, important advances have been made in identifying some of the disorder's genetic and neurobiological underpinnings. It has been discovered that ASD is heritable, with environmental variables also being involved 5 , 6 , 7 . According to certain research, ASD is associated with both hereditary and environmental factors 5 , 8 , 9 . It is especially important to identify environmental risk factors because, unlike genetic risk factors, they can be prevented.

There are more than 20 pre-, peri- and neonatal risk factors associated with ASD 10 , 11 , 12 . Prenatal risk factors that have been associated with ASD involve parental age 13 , interpregnancy interval 14 , 15 , immune factors (such as autoimmune diseases, both viral and bacterial infections during pregnancy) 16 , 17 , medication use (especially antidepressants, anti-asthmatics, and anti-epileptics) 18 , 19 , 20 , maternal metabolic conditions (such as diabetes, gestational weight gain, and hypertension) 21 , 22 , 23 , and maternal dietary factors (such as folic acid and other supplement use, maternal iron (Fe) intake, as well as maternal vitamin D levels) 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 .

Numerous studies indicate that an increased risk of ASD is linked to several perinatal and neonatal factors. These factors include small gestational age or preterm birth, gestational small or large size, the use of labor and delivery drugs 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 . The risk of ASD associated with cesarean delivery is also a subject of continuous discussion 34 , 35 , 36 . Overall, there is no apparent link between assisted conception and a notably higher risk of ASD, however some particular therapies might make ASD more likely.

This study aimed to determine main pre-, peri- and neonatal risk factors linked to ASD among Armenian children. The following research questions were derived to address the objectives of the study:

What are the primary prenatal risk factors associated with the development of ASD among Armenian children?

How do perinatal factors such as maternal complications during childbirth, labor mode, labor interventions, use of labor-inducing drugs, contribute to the risk of ASD in Armenian children?

What neonatal factors, such as birth weight and gestational age, are linked to the likelihood of ASD diagnosis among Armenian children?

How do socio-demographic factors, such as parental education, gender of the child, number of kids in the family, sequence of the kid, influence the relationship between pre-, peri-, and neonatal risk factors and risk of ASD among Armenian children?

To the best of our knowledge, this was the first study of its kind conducted in Armenia that focused on a variety of factors linked to ASD.

The analysis encompassed a total sample of 497 participants, consisting of 168 children diagnosed with ASD and 329 children without ASD. The descriptive analysis revealed significant differences between the cases and controls on several socio demographic variables as well as prenatal, peri- and neonatal risk factors (see Tables 1 , 2 , 3 and 4 ).

The summary of socio demographic characteristics (Table 1 ). Among the cases (the ASD group), the distribution of gender of the child was significantly different to that in the control group. More specifically, while the distribution of male and female were balanced in the control group (52.89% and 47.11% respectively), the proportion of male children was significantly higher in the ASD group (82.14% and 17.86% respectively, p < 0.01). Furthermore, the number of children in the families of cases and controls were slightly different. While the proportion of cases and controls who had two children were similar, families with one child were slightly higher in the ASD group compared to the control group (29.94% and 17.02% respectively, p < 0.01). This picture is reversed with respect to the number of families with more than two children (16.17% and 29.79% respectively). A higher percentage of ASD cases are the first child in the family compared to controls (67.86% vs. 49.54%, p < 0.01). The proportion of non-married families (those that reported to be single, widowed, divorced etc.) were higher in the ASD group compared to the control group (10.24% and 4.28% respectively, p < 0.05). The distribution of the level of educational attainment of the parents were also different between the groups. More specifically, the prevalence of university degree among the cases were somewhat lower compared to that in the control group.

The summary of prenatal risk factors (Table 2 ). With respect to prenatal risk factors, there were significant differences between the cases and controls in interpregnancy intervals, self-reported complications and diseases, medication use, vitamin D levels, maternal weight gain, and the self-reported stress during pregnancy. More specifically, the cases had on average lower interpregnancy intervals compared to the controls (M = 12.9 and M = 23.7 months respectively, p < 0.01). The cases more frequently reported to have had complications during the pregnancy compared to the controls (42.86% and 8.54% respectively, p < 0.01). The prevalence of reported infectious diseases, other diseases and anemia during the pregnancy were also somewhat higher among the cases compared to the control group. The use of medications was higher among the cases compared to the control group (41.67% and 17.74% respectively, p < 0.01). Various medications including vitamins, anticoagulants, Paracetamol, MgB6, Duphaston, iron preparation, No-spa, calcium preparation, antibiotics, and Utrogestan showed significant differences in usage between cases and controls (all p < 0.05) (Table 3 ). The maternal weight gain among the cases was on average higher among the cases compared to the control group (M = 15.4 and M = 13.9 kg respectively, p < 0.05). The self-reported stress was also more frequent among the cases compared to the controls (56.02 and 10.98% respectively, p < 0.01). Specifically, comparing data on self-reported stress during different pregnancy periods, it was obvious that 47.06% of mothers of cases and 91.25% of mothers in the control group reported no stress experienced during pregnancy. During the first trimester, 14.38% of mothers with cases of autism reported stress, whereas only 0.94% of mothers in the control group reported stress. In the second trimester, 11.11% of mothers with cases of autism reported stress, compared to 4.06% of mothers in the control group. During the third trimester, 8.50% of mothers with cases of autism reported stress, while 1.88% of mothers in the control group reported stress. Across the entire pregnancy, 18.95% of mothers with cases of autism reported stress, compared to 1.88% of mothers in the control group. The differences in stress levels between the two groups were statistically significant, indicating a potential link between maternal stress during pregnancy and the odds of autism spectrum disorder in offspring.

The summary of perinatal and neonatal risk factors (Table 4 ). The interpretation of the data comparing various peri- and neonatal risk factors between cases (individuals with ASD) and controls (individuals without ASD) are shown below. 83.33% of cases and 91.77% of controls were born within 37–42 weeks of gestation, with a statistically significant difference ( p < 0.05), whereas 16.67% of cases and 8.23% of controls were born either preterm (before 37 weeks) or post-term (after 42 weeks), also showing a significant difference. There was no statistically significant difference in birth weight between cases and controls (M = 3137.8 and M = 3176.9 g respectively, p > 0.05). The mean birth height was slightly lower for cases compared to controls (M = 50.4 and M = 50.9 cm), with a statistically significant difference ( p < 0.05). No statistically significant difference was reported regarding mode of labor. According to the data interventions during labor were reported more in ASD group compared to controls (39.76% and 17.23% respectively, p < 0.01). Also, labor-inducing drugs were administered more in cases compared to the controls (39.76% and 21.04%, p < 0.01).

The results of multivariable logistic regression

The multivariable logistic regression analysis indicated significant associations between sociodemographic, prenatal, perinatal and neonatal risk factors. More specifically, male children have 4 times higher odds of having ASD compared to female children (OR = 4.21, CI 2.33–7.63). Among prenatal factors, the maternal weight gain, use of MgB6, the self-reported stress during the pregnancy, as well as pregnancy with complications were associated with a significant increase in the odds of ASD, whereas use of Duphaston was associated with decreased odds of ASD (see Table 5 ). Additionally, the longer interpregnancy interval was associated with decreased odds of ASD diagnosis (OR = 0.708, CI 0.52–0.97). Among peri- and neonatal factors, use of labor-inducing drugs was associated with increase in the odds of ASD diagnosis (OR = 2.295, CI 1.3–4.1), while birth height showed association with decrease in odds (OR = 0.788, CI 0.6–1.0).

Our study provides comprehensive insights into the multifaceted nature of ASD, elucidating the intricate relationships between sociodemographic, prenatal, perinatal, and neonatal factors and ASD risk.

Our findings highlight significant gender disparities in ASD prevalence, with a notably higher proportion (4:1) of male children in the ASD group. This aligns with existing literature demonstrating a male predominance in ASD diagnosis 37 . Meanwhile, Loomes et al. reported 3:1 male-to-female ratio referring to a diagnostic gender bias, where girls meeting the criteria for ASD are at an elevated risk of not receiving a clinical diagnosis 38 . Furthermore, our study highlights the potential impact of family structure on the likelihood of ASD occurrence, indicating higher ASD rates among first-born children and in households where the parents are non-married (divorced, widowed, separated, etc.). A study conducted by Ugur et al. yielded comparable findings, suggesting that the prevalence of being the eldest child was higher in the ASD group compared to the control group 39 . Contrary to this, research conducted in the United States found no evidence to suggest that children diagnosed with ASD are more likely to live in households not composed of both their biological or adoptive parents compared to children without ASD 40 .

The association between prenatal risk factors and ASD risk underscores the importance of maternal health during pregnancy. Our findings suggest that factors such as lower IPIs, maternal complications and diseases during pregnancy, medication use, vitamin D levels, maternal weight gain and maternal self-reported stress during pregnancy may increase the odds of ASD in offspring. It is crucial to note that the higher number of firstborn children among cases compared to the control group could introduce bias when accurately estimating the association between IPI and ASD. Therefore, the coefficients of IPI should be interpreted cautiously. Despite this, we opted not to remove this variable from the model, as IPI is recognized as an important factor in existing literature. Several studies report different results regarding long and short IPIs and ASD risk 14 , 15 , 41 , 42 . The underlying reasons for the link between ASD and short and long IPIs may differ. Short IPIs could be associated with maternal nutrient depletion, stress, infertility, and inflammation, whereas long IPIs may be linked to infertility and related complications. According to our results the frequency of self-reported complications during pregnancy was notably higher among children with ASD compared to the controls. Additionally, there was a somewhat higher prevalence of reported infectious diseases, other illnesses, and anemia during pregnancy among the cases compared to the control group. Several previous investigations have associated maternal hospitalization resulting from infection during pregnancy with an elevated risk of ASD. This includes a substantial study involving over two million individuals, which indicated an increased risk associated with viral and bacterial infections during the prenatal period 12 , 17 . Furthermore, our study results indicate that medication usage during pregnancy was more common among the mothers of cases than the controls. Notably, various medications, including vitamins, anticoagulants, Paracetamol, MgB6, Duphaston, iron preparation, No-spa, calcium preparation, antibiotics, and Utrogestan (micronized progesterone), exhibited significant differences in usage between the cases and controls. According to the results of multiple logistic regression analysis use of MgB6 was associated with a significant increase in the odds of ASD, whereas use of Duphaston (Dydrogesterone), a progestin medication, was associated with decreased odds of ASD. Emphasizing the potential impact of additional variables in evaluating the link between Duphaston and ASD is essential. There is a possibility of factors overlooked in our study. However, after analyzing the included variables, no significant confounding effects were detected. This assessment involved scrutinizing the Cramer’s V value between Duphaston and other variables, and sequentially introducing new variables into the model to evaluate changes in the coefficients of Duphaston. In both cases, no significant confounding effects emerged. In contrast to our results certain researchers have shown that the use of supplements during pregnancy is linked to a decreased risk of ASD in offsprings compared to those whose mothers did not take supplements during pregnancy 43 , 44 . The results of an epidemiology study conducted by Li et al. have showed that prenatal progestin exposure was strongly associated with ASD prevalence, and the experiments in rats showed that prenatal consumption of progestin-contaminated seafood induced autism-like behavior 45 . On the other hand other authors suggest that insufficient maternal progesterone levels might contribute to both obstetrical complications and ASD development 46 . The observed association regarding MgB6 use could potentially be influenced by an unmeasured confounding variable in our study. This warrants further investigation and consideration in future research. Additionally, our study highlighted another modifiable risk factor for ASD that was significantly associated with higher odds of ASD: maternal gestational weight gain. This factor retained its significance even in the multivariable analysis. This finding is consistent with the results of several studies which have shown that maternal metabolic conditions like diabetes, gestational weight gain, and hypertension have been associated with mechanisms pertinent to ASD, such as oxidative stress, fetal hypoxia, and chronic inflammation 23 , 47 . These conditions can induce prolonged or acute hypoxia in the fetus, which might pose a substantial risk factor for neurodevelopmental disturbances.

Furthermore, our findings suggest that the self-reported stress during pregnancy was associated with a significant increase in the odds of ASD. When comparing self-reported stress levels during different pregnancy periods, a notable disparity emerged. The statistically significant differences in stress levels between the two groups were reported in all trimesters of pregnancy suggesting a potential correlation between maternal stress during pregnancy and the odds of autism spectrum disorder in offspring. Several authors report comparable findings suggesting that prenatal maternal stress show significant association with both autistic traits and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) behaviors 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 . Various mechanisms could be suggested to explain the link between prenatal stress and likelihood of ASD. For instance, stress during pregnancy can trigger physiological changes in the mother's body, such as increased cortisol levels and alterations in immune function, which may impact fetal development and contribute to the risk of ASD. Also, stress may affect placental function, leading to adverse changes in the transfer of nutrients and oxygen to the fetus. Furthermore, prenatal stress can influence gene expression in both the mother and the developing fetus. Certain genes involved in brain development and the stress response system may be affected, potentially increasing the risk of ASD. Additionally, maternal stress may influence parenting behaviors and interactions with the child after birth. High levels of maternal stress may affect the quality of caregiving, which in turn can impact the child's social and emotional development, potentially contributing to ASD risk. Lastly, stress during pregnancy could induce epigenetic modifications, which are alterations in gene expression that occur without changes in DNA sequence. These modifications might affect neurodevelopmental processes, making individuals more susceptible to ASD.

Our study reports notable statistical difference among cases and controls regarding gestational age. According to the results 16.67% of cases were born either preterm (before 37 weeks) or post-term (after 42 weeks), highlighting another significant distinction. Early gestational age is linked with unfavorable health consequences, such as developmental delays and subsequent intellectual impairments throughout childhood and adolescence. Similar results are reported by several authors as well 30 , 31 , 52 . According to our study results birth height was associated with decrease in odds of ASD, however there was no statistically significant difference in birth weight between cases and controls. Some authors demonstrated that infants with birth weights of < 2.5 kg were associated with ADHD and ASD 53 , 54 .

Other than the previously mentioned factors the results of our study have demonstrated that use of labor-inducing drugs was associated with increase in the odds of ASD. The study participants did not report or specify the type of used labor-inducing drugs. Recent investigations have indicated a potential correlation between the utilization of drugs during labor and delivery and the emergence of ASD 55 , 56 , especially given the increased usage of epidurals and labor-inducing medications in the past 30 years. However, conflicting findings exist, with some studies suggesting no link between the administration of labor-inducing drugs and the risk of ASD development 57 , 58 . Recent findings from Qiu et al. propose a potential link between maternal labor epidural analgesia and the risk of ASD in children, particularly when oxytocin was concurrently administered. However, oxytocin exposure in the absence of labor epidural analgesia did not show an association with ASD risk in children 59 . The potential link between the use of labor-inducing drugs and the risk of ASD is complex and not yet fully understood. However, several mechanisms have been proposed to explain this association: for example, labor-inducing drugs, such as oxytocin and prostaglandins, can affect hormonal levels in both the mother and the fetus. These hormonal changes may impact brain development and neural connectivity, potentially increasing the risk of ASD. In addition, labor induction may increase the risk of oxygen deprivation (hypoxia) during labor. Prolonged hypoxia during birth has been linked to adverse neurological outcomes, including an increased risk of neurodevelopmental disorders like ASD. Furthermore, labor induction can lead to an inflammatory response in both the mother and the fetus. This immune system activation may affect neurodevelopmental processes and contribute to the development of ASD. Overall, the relationship between labor-inducing drugs and ASD risk is multifactorial and likely involves interactions between genetic, environmental, and biological factors. Further research is needed to elucidate the specific mechanisms underlying this association.

To our knowledge this is the first study identifying potential pre-, peri- and neonatal risk factors associated with ASD in Armenia.

Limitations and strength

While our study possesses a retrospective design, a notable limitation, it depended on parental recall for details dating back several years. Additionally, the sample was not balanced in terms of gender, with more male children included, potentially introducing selection bias. Despite the relatively small sample size multivariable analysis using the presence or absence of ASD as the dependent variable was implemented to address potential confounding factors.

Nevertheless, our study included a representative sample of the Armenian ASD population, evaluating various factors in comparison with a randomly selected control group matched for age. All ASD diagnoses were made according to DSM-5 by professionals (psychiatrists, pediatricians, neurologists, speech therapists and developmental psychologists), and face-to-face interviews with parents at the time of the interview minimized the risk of information bias.

Our findings indicated that male gender, maternal weight gain, MgB6 usage, self-reported stress during pregnancy, pregnancy complications, and labor-inducing drugs were linked to a significant rise in ASD odds (Fig. 1 ). Conversely, the use of Duphaston during pregnancy, longer interpregnancy intervals, and higher birth height were associated with reduced odds of ASD (Fig. 1 ). These observations underpin the significance of regional investigations to uncover the unique environmental factors contributing to ASD. The implications are profound, as several identified factors may be preventable or adjustable, highlighting the urgency of implementing evidence-based practices and public health interventions. Emphasizing a culture of health promotion, screenings, timely diagnosis, and disease prevention strategies, particularly among pregnant women, holds promise for reducing ASD and related disorders. Moreover, further prospective and focused research is imperative to discern the interplay between various factors and gene-environment interactions that may serve as potential ASD risk factors. Enhanced understanding in this area could lead to earlier detection and improved ASD management. Future studies incorporating analyses of biological samples for genetic, epigenetic, and inflammatory markers will be pivotal in elucidating underlying mechanisms and ushering in a new phase of research focusing on modifiable risk factors for developmental disorders.

Sum up scheme showing prenatal, perinatal and neonatal factors which increase, as well as decrease the odds of ASD.

The study population comprised of 497 participants, of which 168 were children with ASD and 329 were typical development controls. The subject recruitment was done during 2021 to 2022. The controls and children with ASD were age matched (3–18 years). The subjects were formally diagnosed with ASD according to DSM-5 by professionals (pediatricians, neurologists, speech therapists and developmental psychologists). The children with ASD were recruited at MY WAY Educational and Rehabilitation Center in Yerevan. Inclusion criteria for cases were age between 3 and 18 years with ASD with diagnosis confirmed using DSM-V. Exclusion criteria for cases were other neurodevelopment disorders other than ASD. The control participants were randomly selected in the same period at Muratsan Hospital Complex. They were not known to have any neurodevelopmental or behavioral disruptions that might be related to ASD. The control group consisted exclusively of individuals diagnosed with simple conditions like flu or a simple routine physical examination.

Questionnaire and data collection

The self-reported questionnaire was completed via a face-to-face interview with the child’s parent. The questionnaire comprised three sections: various aspects of sociodemographic characteristics, prenatal risk factors, and perinatal/neonatal risk factors. Each section addressed specific questions related to these factors for comprehensive data collection. On average, the questionnaire was completed in about 15 to 20 min. The parent had the choice of accepting or refusing to complete the questionnaire. At the end of the process, the completed questionnaires were collected and sent for data entry by using SPSS 21 statistical software. The questionnaire was designed to acquire the information regarding risk factors of ASD. It consisted of different sections: sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., age, sex, family history of ASD, etc.), data on prenatal risk factors (e.g., pregnancy process, complications during pregnancy, infections during pregnancy, other diseases, stress, medication and supplement use during pregnancy, vitamin D level, etc.), questions related to maternal lifestyle risk factors (e.g., smoking, alcohol consumption, gestational weight gain). Respondents were also asked about peri- and neonatal risk factors, including gestational age, gestational size, the use of labor and delivery drugs, mode of delivery, etc.

Ethics disclosure

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee (N 8–2/20; 27.11.2020) of Yerevan State Medical University in line with the principles set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all the parents of the participants prior to data collection.

Statistical analysis

The data was processed and modelled in Python (version 3.11.6), an open- source software often used for data processing and modelling. The statistical analysis was performed by using the Statsmodels package (version 0.14.1) 60 .

Descriptive statistics were employed to summarize the characteristics of the study variables. Continuous variables were described using means and standard deviations, while categorical variables were presented as proportions. Prior to statistical analysis, numeric variables underwent standardization through the computation of z scores. To evaluate potential multicollinearity among predictor variables, the Variable Inflation Index (VIF) was computed. A predetermined threshold of 5 was established, and variables exceeding this threshold were considered indicative of multicollinearity. Bivariate analyses were conducted to explore associations between predictor variables and the outcome variable (presence or absence of autism diagnosis). T-tests were employed for continuous variables, while chi-squared tests were utilized for nominal and categorical variables. A multivariable logistic regression model was constructed to estimate the relationship between predictor variables and the outcome variable (autism diagnosis). Initially, a comprehensive strategy was employed by first fitting a null model and then iteratively introducing blocks of variables (e.g., socio demographic factors prenatal, peri- and neonatal factors). After introducing the new block of factors, a likelihood ratio test was conducted to evaluate the contribution of the added variables. If the p -value associated with the likelihood ratio test was insignificant ( p > 0.05), the preference was given to a less complex model. In our analysis all added blocks had significant contribution to the overall fit of the model.

Subsequently, the significance of each variable was systematically assessed by applying a stepwise elimination technique whereby insignificant variables were progressively removed from the model. Similar to the above-mentioned process, at each step, a likelihood ratio test to evaluate the significance of the excluded variable was conducted. If the p -value associated with this test was found to be insignificant ( p > 0.05), the adoption of a simpler model was favored. This iterative process allowed us to identify the most parsimonious model that retained statistically significant predictors while minimizing unnecessary complexity. Odds ratios (ORs) were computed, accompanied by 95% confidence intervals (CIs), to quantify the strength and direction of these associations.

Data availability

Data can be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5 TM , 5th Ed . xliv, 947 (American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc., Arlington, VA, US, 2013). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 .

Zeidan, J. et al. Global prevalence of autism: A systematic review update. Autism Res. 15 , 778–790 (2022).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

CDC. Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) Network. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/addm.html (2023).

CDC. Data and Statistics on Autism Spectrum Disorder | CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data.html (2024).

Tick, B., Bolton, P., Happé, F., Rutter, M. & Rijsdijk, F. Heritability of autism spectrum disorders: A meta-analysis of twin studies. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 57 , 585–595 (2016).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Lord, C., Elsabbagh, M., Baird, G. & Veenstra-Vanderweele, J. Autism spectrum disorder. Lancet 392 , 508–520 (2018).

Muhle, R. A., Reed, H. E., Stratigos, K. A. & Veenstra-VanderWeele, J. The emerging clinical neuroscience of autism spectrum disorder: A review. JAMA Psychiatry 75 , 514–523 (2018).

Bai, D. et al. Association of genetic and environmental factors with autism in a 5-country cohort. JAMA Psychiatry 76 , 1035–1043 (2019).

Jutla, A., Reed, H. & Veenstra-VanderWeele, J. The architecture of autism spectrum disorder risk: What do we know, and where do we go from here?. JAMA Psychiatry 76 , 1005–1006 (2019).

Gardener, H., Spiegelman, D. & Buka, S. L. Perinatal and neonatal risk factors for autism: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Pediatrics 128 , 344–355 (2011).

Guinchat, V. et al. Pre-, peri- and neonatal risk factors for autism. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 91 , 287–300 (2012).

Yenkoyan, K., Mkhitaryan, M. & Bjørklund, G. Environmental risk factors in autism spectrum disorder: A narrative review. Curr. Med. Chem. https://doi.org/10.2174/0109298673252471231121045529 (2024).

Lyall, K. et al. The association between parental age and autism-related outcomes in children at high familial risk for autism. Autism. Res. 13 , 998–1010 (2020).

Cheslack-Postava, K. et al. Increased risk of autism spectrum disorders at short and long interpregnancy intervals in Finland. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 53 , 1074-1081.e4 (2014).

Zerbo, O., Yoshida, C., Gunderson, E. P., Dorward, K. & Croen, L. A. Interpregnancy interval and risk of autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics 136 , 651–657 (2015).

Lee, B. K. et al. Maternal hospitalization with infection during pregnancy and risk of autism spectrum disorders. Brain Behav. Immun. 44 , 100–105 (2015).

Zerbo, O. et al. Maternal infection during pregnancy and autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 45 , 4015–4025 (2015).

Christensen, J. et al. Prenatal valproate exposure and risk of autism spectrum disorders and childhood autism. JAMA 309 , 1696–1703 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bromley, R. L. et al. The prevalence of neurodevelopmental disorders in children prenatally exposed to antiepileptic drugs. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 84 , 637–643 (2013).

Gidaya, N. B. et al. In utero exposure to β-2-adrenergic receptor agonist drugs and risk for autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics 137 , e20151316 (2016).

Walker, C. K. et al. Preeclampsia, placental insufficiency, and autism spectrum disorder or developmental delay. JAMA Pediatr 169 , 154–162 (2015).

Krakowiak, P. et al. Maternal metabolic conditions and risk for autism and other neurodevelopmental disorders. Pediatrics 129 , e1121-1128 (2012).

Li, M. et al. The association of maternal obesity and diabetes with autism and other developmental disabilities. Pediatrics 137 , e20152206 (2016).

Black, M. M. Effects of vitamin B12 and folate deficiency on brain development in children. Food Nutr. Bull. 29 , S126-131 (2008).

Surén, P. et al. Association between maternal use of folic acid supplements and risk of autism spectrum disorders in children. JAMA 309 , 570–577 (2013).

Skalny, A. V. et al. Magnesium status in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and/or autism spectrum disorder. Soa Chongsonyon Chongsin Uihak 31 , 41–45 (2020).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Virk, J. et al. Preconceptional and prenatal supplementary folic acid and multivitamin intake and autism spectrum disorders. Autism 20 , 710–718 (2016).

Whitehouse, A. J. O. et al. Maternal vitamin D levels and the autism phenotype among offspring. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 43 , 1495–1504 (2013).

Zhong, C., Tessing, J., Lee, B. & Lyall, K. Maternal dietary factors and the risk of autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review of existing evidence. Autism Res. 13 , 1634–1658 (2020).

Moore, G. S., Kneitel, A. W., Walker, C. K., Gilbert, W. M. & Xing, G. Autism risk in small- and large-for-gestational-age infants. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 206 (314), e1-9 (2012).

Google Scholar

Leavey, A., Zwaigenbaum, L., Heavner, K. & Burstyn, I. Gestational age at birth and risk of autism spectrum disorders in Alberta, Canada. J. Pediatr. 162 , 361–368 (2013).

Smallwood, M. et al. Increased risk of autism development in children whose mothers experienced birth complications or received labor and delivery drugs. ASN Neuro. 8 , 1759091416659742 (2016).

Qiu, C. et al. Association between epidural analgesia during labor and risk of autism spectrum disorders in offspring. JAMA Pediatr. 174 , 1168–1175 (2020).

Curran, E. A. et al. Association between obstetric mode of delivery and autism spectrum disorder: A population-based sibling design study. JAMA Psychiatry 72 , 935–942 (2015).

Curran, E. A. et al. Research review: Birth by caesarean section and development of autism spectrum disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 56 , 500–508 (2015).

Nagano, M. et al. Cesarean section delivery is a risk factor of autism-related behaviors in mice. Sci. Rep. 11 , 8883 (2021).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Werling, D. M. & Geschwind, D. H. Sex differences in autism spectrum disorders. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 26 , 146–153 (2013).

Loomes, R., Hull, L. & Mandy, W. P. L. What is the male-to-female ratio in autism spectrum disorder? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 56 , 466–474 (2017).

Ugur, C., Tonyali, A., Goker, Z. & Uneri, O. S. Birth order and reproductive stoppage in families of children with autism spectrum disorder. Psychiatry Clin. Psychopharmacol. 29 , 509–514 (2019).

Article Google Scholar

Freedman, B. H., Kalb, L. G., Zablotsky, B. & Stuart, E. A. Relationship status among parents of children with autism spectrum disorders: A population-based study. J. Autism. Dev. Disord. 42 , 539–548 (2012).

Gunnes, N. et al. Interpregnancy interval and risk of autistic disorder. Epidemiology 24 , 906–912 (2013).

Durkin, M. S., Allerton, L. & Maenner, M. J. Inter-pregnancy intervals and the risk of autism spectrum disorder: Results of a population-based study. J. Autism. Dev. Disord. 45 , 2056–2066 (2015).

Levine, S. Z. et al. Association of maternal use of folic acid and multivitamin supplements in the periods before and during pregnancy with the risk of autism spectrum disorder in offspring. JAMA Psychiatry 75 , 176–184 (2018).

Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Schmidt, R. J., Iosif, A.-M., Guerrero Angel, E. & Ozonoff, S. Association of maternal prenatal vitamin use with risk for autism spectrum disorder recurrence in young siblings. JAMA Psychiatry 76 , 391–398 (2019).

Li, L. et al. Prenatal progestin exposure is associated with autism spectrum disorders. Front Psychiatry 9 , 611 (2018).

Whitaker-Azmitia, P. M., Lobel, M. & Moyer, A. Low maternal progesterone may contribute to both obstetrical complications and autism. Med Hypotheses 82 , 313–318 (2014).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Vecchione, R. et al. Maternal dietary patterns during pregnancy and child autism-related traits: Results from two US cohorts. Nutrients 14 , 2729 (2022).

Ronald, A., Pennell, C. & Whitehouse, A. Prenatal maternal stress associated with ADHD and autistic traits in early childhood. Front. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2010.00223 (2011).

Caparros-Gonzalez, R. A. et al. Stress during pregnancy and the development of diseases in the offspring: A systematic-review and meta-analysis. Midwifery 97 , 102939 (2021).

Manzari, N., Matvienko-Sikar, K., Baldoni, F., O’Keeffe, G. W. & Khashan, A. S. Prenatal maternal stress and risk of neurodevelopmental disorders in the offspring: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 54 , 1299–1309 (2019).

Say, G. N., Karabekiroğlu, K., Babadağı, Z. & Yüce, M. Maternal stress and perinatal features in autism and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatr. Int. 58 , 265–269 (2016).

Abel, K. M. et al. Deviance in fetal growth and risk of autism spectrum disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 170 , 391–398 (2013).

Song, I. G. et al. Association between birth weight and neurodevelopmental disorders assessed using the Korean National Health Insurance Service claims data. Sci. Rep. 12 , 2080 (2022).

Lampi, K. M. et al. Risk of autism spectrum disorders in low birth weight and small for gestational age infants. J. Pediatr. 161 , 830–836 (2012).

Bashirian, S., Seyedi, M., Razjouyan, K. & Jenabi, E. The association between labor induction and autism spectrum disorders among children: A meta-analysis. Curr. Pediatr. Rev. 17 , 238–243 (2021).

Oberg, A. S. et al. Association of labor induction with offspring risk of autism spectrum disorders. JAMA Pediatr. 170 , e160965 (2016).

Karim, J. L. et al. Exogenous oxytocin administration during labor and autism spectrum disorder. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 5 , 101010 (2023).

Qiu, C. et al. Association of labor epidural analgesia, oxytocin exposure, and risk of autism spectrum disorders in children. JAMA Netw. Open 6 , e2324630 (2023).

Seabold, S. & Perktold, J. Statsmodels: Econometric and Statistical Modeling with Python. Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference 92–96 (2010) https://doi.org/10.25080/Majora-92bf1922-011 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to all parents participated in the study.

This work was supported by Higher Education and Science Committee, Ministry of Education, Science, Culture and Sports of RA (24YSMU-CON-I-3AN and 23LCG-3A020), and YSMU.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Neuroscience Laboratory, Cobrain Center, Yerevan State Medical University Named After M. Heratsi, 0025, Yerevan, Armenia

Meri Mkhitaryan & Konstantin Yenkoyan

Cobrain Center, Yerevan State Medical University Named After M. Heratsi, 0025, Yerevan, Armenia

Tamara Avetisyan & Larisa Avetisyan

Muratsan University Hospital Complex, Yerevan State Medical University Named After M. Heratsi, 0075, Yerevan, Armenia

Tamara Avetisyan

Department of Infectious Diseases, Yerevan State Medical University Named After M. Heratsi, 0025, Yerevan, Armenia

Anna Mkhoyan

Department of Hygiene, Yerevan State Medical University Named After M. Heratsi, 0025, Yerevan, Armenia

Larisa Avetisyan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

M.M. and K.Y. conceived the project; M.M., T.A., A.M., L.A. and K.Y. designed experiments, collected and analyzed data; M.M., T.A., A.M., L.A., and K.Y. wrote the draft; M.M., A.M., and K.Y. edited the manuscript. K.Y. obtained funding and supervised the study. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Konstantin Yenkoyan .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Mkhitaryan, M., Avetisyan, T., Mkhoyan, A. et al. A case–control study on pre-, peri-, and neonatal risk factors associated with autism spectrum disorder among Armenian children. Sci Rep 14 , 12308 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63240-3

Download citation

Received : 02 March 2024

Accepted : 27 May 2024

Published : 29 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63240-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Autism spectrum disorder

- Case–control study

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

COVID-19 Pandemic Experiences of Families in Which a Child/Youth Has Autism and Their Service Providers: Perspectives and Lessons Learned

- Original Article

- Open access

- Published: 20 May 2024

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- David B. Nicholas ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4480-322X 1 ,

- Rosslynn T. Zulla ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9881-830X 1 ,

- Jill Cielsielski 1 ,

- Lonnie Zwaigenbaum ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9607-0799 2 &

- Olivia Conlon 1

191 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on autistic children/youth and their families and on service providers are not yet well-understood. This study explored the lived experiences of families with an autistic child and service providers who support them regarding the impacts of the pandemic on service delivery and well-being.

In this qualitative study, families and service providers (e.g., early intervention staff, service providers, school personnel) supporting autistic children/youth were interviewed. Participants were recruited from a diagnostic site and two service organizations that support autistic children/youth.

Thirteen parents and 18 service providers participated in either an individual or group interview. Findings indicate challenges associated with pandemic restrictions and resulting service shifts. These challenges generally imposed negative experiences on the daily lives of autistic children/youth and their families, as well as on service providers. While many were adversely affected by service delivery changes, families and service agencies/providers pivoted and managed challenges. Shifts have had varied impacts, with implications to consider in pandemic planning and post-pandemic recovery.

Results highlight the need for autism-focused supports, as well as technology and pandemic preparedness capacity building within health, therapeutic and educational sectors in order to better manage shifts in daily routines during emergencies such as a pandemic. Findings also offer instructive consideration in service delivery post-pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

COVID-19 Pandemic and Impact on Patients with Autism Spectrum Disorder

Brief report: impact of the covid-19 pandemic on asian american families with children with developmental disabilities.

The COVID-19 Pandemic Experience for Families of Young Children with Autism

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The COVID-19 pandemic was associated with service disruptions that substantially affected autistic individuals and their families, resulting in shifts in daily life. As efforts were made to limit COVID-19 risk, individual and family routines and resources shifted. Public health measures have now largely been lifted, yet some pandemic shifts and impacts remain. This study elicited the experiences of families of autistic children and youth as they navigated the pandemic, from the perspective of both families and service providers.

Children and youth with autism were deeply affected by the COVID-19 pandemic (Colizzi et al., 2020 ; Shorey et al., 2021 ). In terms of daily life, daily routines were interrupted, with early outcomes such as behavioural difficulties and social and communication challenges (Mutluer et al., 2020 ). School closures limited many supports that autistic children/youth typically access (Colizzi et al., 2020 ). In one study, over 70% of families of children with special needs experienced decreased educational/therapeutic services (e.g., reduced number of sessions, changes to therapy modality) during the pandemic (Jeste et al., 2020 ). Virtual delivery of educational and therapeutic services was attempted to sustain services while reducing in-person contact (Assenza et al., 2021 ; Shorey et al., 2021 ), with mixed responses to these shifts. Family caregivers expressed concern about the loss of direct involvement of professionals in service delivery, and worried about their child’s skill regression (Latzer et al., 2021 ; Stankovic et al., 2022 ).

The implementation of social distancing and infection control protocols in daily life was noted to create substantial confusion for some children/youth. Many autistic children did not fully comprehend the pandemic, as well as related requirements for physical isolation and hygiene/safety precautions. These children/youth variably struggled with adhering to safety protocols (e.g., wearing masks) due to autism-related challenges such as sensory sensitivities (Mutluer et al., 2020 ). It was perceived that autistic children/youth who understood the pandemic and its implications had better outcomes (Asbury et al., 2021 ).

Pandemic Impacts on Families

Changes in therapeutic services and education required many parents to independently support their child’s schooling and support needs (Shorey et al., 2021 ). The struggle to organize activities amidst a lack of supports (Assenza et al., 2021 ; Colizzi et al., 2020 ) reportedly resulted in feelings of inadequacy and anxiety among parents (Assenza et al., 2021 ; Colizzi et al., 2020 ; Mutluer et al., 2020 ). Among families in which the child experienced challenges such as complex behavioral issues, parents reported higher levels of stress related to caregiving, thus seeking respite services (Manning et al., 2020 ). In comparison to parents of typically developing peers, parents of autistic children reported lower resiliency and poorer coping as well as greater anxiety and depression (Wang et al., 2021 ).

Impacts on Service Providers

Similar to what was reported by families, substantial pandemic impacts also were described by service providers. Teachers working with special needs populations indicated that online school platforms impeded their ability to provide multi-sensory curricula (Kim et al., 2021 ), teach using multiple prompts (e.g., verbal, visual, tactile) (Kim et al., 2021 ), and support students to self-regulate as they learn (Lambert & Schuck, 2021 ). Teachers also reported that the delivery of lessons in online school platforms was difficult for children with focus/attention and self-regulation challenges (Lambert & Schuck, 2021 ). Autism service providers reported concerns related to certain interventions not being as effective over technology platforms, and online platforms not being effective or appropriate with some children, such as those who were minimally verbal (Fell et al., 2023 ). A lack of technology including devices and internet, and low technology literacy impeded online teaching and assessments (Kellom et al., 2023 ; Steed & Leech, 2021 ). Additional challenges included a lack of collaboration with parents in online education (Steed & Leech, 2021 ), and concerns over the accessibility of online platforms related to English proficiency (Kellom et al., 2023 ).

The service landscape was drastically modified or decreased (Colizzi et al., 2020 ), resulting in long-standing impacts that are not yet fully realized. There further has been relatively little examination of how the pandemic was experienced by autism service providers and its impact on their practice. This is a critical gap given that service providers are often relied upon by parents to support and devise strategies to help autistic children. There is need to better understand family and service provider experiences and perspectives relative to gaps and opportunities that have unfolded as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. To address this gap, this study explored the lived experiences of families with an autistic child and service providers who support them. Research questions were: (1) How was the COVID-19 pandemic experienced by families in which a child/youth has autism, and their service providers?, (2) What were the barriers to, and facilitators of, service delivery in the pandemic?, and (3) What recommendations are offered to improve service delivery?

Parents of autistic children (to 18 years) and their service providers were recruited from a regional diagnostic/specialty care center and two service delivery centers offering educational, therapeutic and developmental supports within a large city in western Canada. These organizations delivered direct support to autistic children/youth and their families during the pandemic.

Data collection occurred from August 2020 to May 2021. During this period, the jurisdiction underwent several transitions, moving back and forth from restrictions to re-openings in public spaces. Recruitment was undertaken with the support of intermediaries in the above organizations who informed both families and service providers via word-of-mouth and email. Potential participants were provided with information about the study, and if study participation was desired, they were invited to engage in an interview.

Semi-structured interview guides for families and service providers were developed by team members who bring experience in qualitative autism-focused research as well as in service provision, and the team included a parent with first-person family experience of autism. For parents, questions focused on the perceived impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic relative to service access and experience, daily life and well-being. Questions to service providers elicited perceived impacts of the pandemic on service delivery and child, family and service provider well-being. Examples of questions are outlined in Table 1 .

Conducted via Zoom technology or telephone, interviews lasted 0.5 to 1 h. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim for subsequent analysis. Families and community service providers who support autistic children/youth and their families were involved in study design, as well as reflecting on findings and manuscript development (e.g., reviewing and providing feedback on the manuscript).

A qualitative content analysis approach guided data management and analysis (Elo & Kyngas, 2008 ; Graneheim & Lundman, 2004 ). This approach grounded codes in participants’ perspectives, and delineated experiences, impacts and recommendations. Transcripts were analyzed using a three-step process: (1) reviewing the transcripts to gain an understanding of the data, (2) conducting an inductive analysis, and (3) mapping the data to generate themes (Elo & Kyngas, 2008 ; Graneheim & Lundman, 2004 ). The inductive analysis approach comprised three steps: coding data to develop units of meaning (line-by-line coding) , grouping these units into a logical schema (creating categories) , and interpreting and organizing these units (determining themes) . Analysis was undertaken by one team member (JC), with other team members (RTZ, DBN) reviewing a portion of the coding, thus supporting the categorization of codes and generation of themes (Elo & Kyngas, 2008 ; Graneheim & Lundman, 2004 ). Reviews of codes, categories and emergent themes occurred on a regular basis amongst team members. NVivo 12 data management and analysis software was used to support the data analysis.

Trustworthiness (qualitative research rigor) was demonstrated via peer debriefing, member checking, referential adequacy and team memoing to document and justify analytic decision making (Lincoln & Guba, 2005 ). These measures demonstrate thematic resonance with the data and suggest rigor in the analytic process. Institutional research ethics board review and approval were obtained from host university sites prior to study commencement (University of Calgary Conjoint Faculties Research Ethics Board #REB20-0367). Psychosocial support was available and offered to participants if needed, but was not requested. All identifying information was removed from transcripts prior to data analysis.

In total, 33 individuals participated in this study, comprising 13 parents (12 mothers and 1 father) and 18 service providers. The autistic children of participating parents ranged in age from 8 to 18 years of age, and included 12 males and 1 female. Demographic information about represented families are outlined in Table 2 . Service providers comprised healthcare and community service professionals from multiple disciplines (e.g., physicians, psychologists, speech language pathologists, behavior analysts, occupational therapists, social workers, nurses), school-based providers (e.g., educational consultants, teachers) and program administrators/leaders (e.g., program coordinators, program/agency directors). All healthcare/service providers worked in autism-related services and practiced during the pandemic.

Overall, participants stated that autistic children and their families experienced significant challenges and adjustments on a daily basis during the COVID-19 pandemic. Parents navigated various services in seeking to help their child—some with perceived benefits and others not. Service providers described seeking to accommodate children’s needs while adhering to shifting safety management protocols. Themes emerged in each group (families and service providers), as follows: (a) pivoting quickly and on an ongoing basis, (b) accommodating changes and addressing needs, (c) impacts on health and well-being, and (d) holding onto hope yet concern for the future. The themes include sub-themes, as outlined below.

(a) Pivoting Quickly and on an Ongoing Basis

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic elicited rapid shifts in services, with deleterious impacts on families and service providers. Emerging sub-themes within this experience were ‘Service Shifts and Uncertainties’ and ‘Family Fears and Strains’; each sub-theme is outlined below.

Service Shifts and Uncertainties

Services that were deemed ‘non-essential’ (e.g., schools, accessible transportation services) were closed or substantially decreased or modified, resulting in limited resources and support for autistic children/youth and their families, notably with some services shifting to virtual modalities. Service providers needed to rapidly seek to understand and then navigate resources to address child/family needs. As one service provider recalled,

Non-essential services were closed and essential services were open, and we felt like we fit in a middle ground there. We really needed to figure out how to continue to provide services to our families. We knew the families were going to be really struggling with kids out of school and out of routine. But we weren’t necessarily designated as an essential service in an obvious way. So we had to establish a connection… so that we were able to continue to provide services, and that gave us that opportunity to do a critical support needs assessment so we could focus our attention on those [children/families] with the highest level of need.

Service providers felt that the lack of clarity about what constituted an ‘essential’ service in the pandemic, left families unclear about what they could access which further left them under-served. Service insufficiency and vagueness in guidelines heightened the demands of family caregiving, as observed by a service provider:

It was so unclear to families [whether] they were [or were not] allowed to have respite [care]. Of our families, at least 50% of them stopped having anyone come into their home so now they have twenty-four hours a day [caring for] their child with huge needs, and they’re in charge twenty-four hours which made them burn out.

Due to public health protocols, in-person supports were transitioned to an array of remote/electronic formats (e.g., telephone, text, email, online synchronous platform). For many service providers and families, this change required rapid learning about how to use various online platforms and navigate shifting services. A service provider recalled,

We shifted gears… overnight. We went from having no video conference capacity to here’s your Zoom login and ID, and then we all had to figure out how to do a Zoom meeting.

Service providers described trying to prioritize support needs such as addressing behavioral struggles and emotional strain due to the loss of school and diminished autism-related supports. They recalled seeking to implement service flexibility to better accommodate family needs and schedules. Yet, they also described uncertainty and worry as they adjusted quickly amidst unknown health risks associated with these shifts.

Making changes in service delivery was described to be especially difficult early in the pandemic. For service providers, modifying services to align with safety protocols was rendered more challenging due to a lack of knowledge about COVID-19, uncertainty about the effectiveness of safety protocols, and unknown impacts of these shifts and service gaps on autistic children and their families. A service provider recalled,

I never said, “It’s going to be okay” because I didn’t know. But I would say, “We’re going to figure this out.” And then I’d wait for direction, but the communication was not there…. No one knew what the heck was going on… so that fear of the unknown was very, very present with the team.

Shifting services became particularly difficult in cases in which children/youth required assistive and/or medical support. For instance, one service provider recalled significant challenges coordinating and sending communication devices to families in distant rural regions during service and school closures. Seeking to offer support in these circumstances, staff improvised and sought to remain in relatively close contact with families, as possible, as reflected on by a service provider:

When COVID-19 first started, we gathered information from the families and then prepared documents of a whole bunch of things to share with families. As a coordinator, I went to every single family’s home and whether I stood outside or at their kitchen table, whatever they were comfortable with and had conversations about COVID-19, about impact, [and] about what our services were to look like.

Family Fears and Strains

For families, the pandemic ushered in fears about COVID-19 transmissibility as well as decreased services to address anxiety and support well-being. An array of services (e.g., in-home support, recreation, social skills, healthcare, public transportation) were either shut down, modified, or delayed. For instance, alterations to public transportation meant that some families had to delay appointments. The sudden shutdown of schools and after-school resources was described as ‘ terrible ’, ‘ so stressful ’ and ‘ very confusing ’ by families. Parents sought to help their autistic child accommodate to sudden transitions in school and after-school activities, yet children/youth had significant difficulty, as illustrated by a parent who reflected on the difficulty with school transitions:

School was quite difficult. It was really difficult to get [autistic child] to do the school [work]…. He was supposed to have… two hours of work, but… it was taking him like four hours…. It was a big stress on our relationship too because… I was trying to get him to do the work and he didn’t want to.

Changes in daily routines such as requisites to stay home, were difficult for some children/youth to understand and accept. In response, parents trialed various strategies to help their child cope. For instance, some parents created a schedule for their child in an attempt to heighten predictability in the day and week.

(b) Accommodating Changes and Addressing Needs

As the pandemic continued over time, families experienced ongoing changes in service delivery and in daily routines. Sub-themes in this overall theme were, ‘Prioritizing Safety, but at a Cost’, ‘Reliance on Virtual Services’, and ‘Family Adjustment’, as described below.

Prioritizing Safety, but at a Cost

As the COVID-19 pandemic lingered, the need for adherence to safety and adjustment to ongoing changes remained a priority for agency leaders as they sought to support families relative to child development and well-being. Service providers described extensive measures such as the use of personal protective equipment and social distancing, while simultaneously monitoring and attending to child/youth and family needs. With a focus on safety, service providers felt hindered in their ability to effectively engage children/youth as they were accustomed to, and thus provide optimal support, as described by a service provider:

We can’t really do our jobs [when we’re] six feet from our kids [service recipients] because in order to actively engage them and get them interested in what we’re doing, I can’t be across the room right, because often times, they thrive upon like facial expression. We’re interacting with something and we are modelling what to do with it. Well, if I’m sitting on the other side of the room…, they’re not going to be engaged with me.

In terms of economic sufficiency and stability, both service providers and families variably faced vulnerability. Compensation for some service providers and parents were viewed as inadequate and difficult to access. Reflecting on required employment absence due to illness or quarantine, a service provider commented:

The funding to cover you when you are sick or you have to isolate which is a government mandate, only covers you one time a year…. In this global pandemic, they’re saying people are going to go on multiple bouts of isolation…, but we provide support [only] once. How are businesses supposed to keep up with that? They can’t. But how are people supposed to go on isolation multiple times without getting paid?

Negative pandemic impacts on financial stability both for families and services providers were deemed to be under-addressed. Further, inflationary pressures later in the pandemic resulted in lingering financial strain, with potentially heightened and continuing effects on families and service providers.

Reliance on Virtual Services

As the pandemic persisted, service providers modified supports through a combination of in-person and virtual formats (e.g., email, online, telephone, synchronous platforms). In choosing approaches, families’ needs and preferences, to a degree, guided services, as noted by a service provider:

The families became the driver… because they were in it twenty-four hours a day and they could see, ‘here’s what we need to work on’. It was less ‘cookie cutter’ service and more family-focused.

Virtual service delivery was seen to have benefited service providers through eliminating the need to travel to and from appointments, providing a venue for quick check-ins with families, and offering an efficient means for coworkers to meet and engage in peer support. For several families (but not for all), virtual support emerged as a vicarious silver lining of the pandemic in advancing an alternative platform for service delivery to children/youth and families. A service provider noted,

[Technology] opened up the way we communicate. Now our staff is asking our participants, “What is your preferred way of communicating? Should I text you? Should I FaceTime you? Are we emailing? Do you like phone calls?” So we’ve learned to actually expand the way we communicate with our participants, and it’s been extremely positive. Moving forward, we are trying to find ways to continue that because our participants are even wanting to communicate with each other which has never come up before, but now they are looking. It’s almost like they’ve found a new way that’s acceptable to communicate.

While identifying benefits of online communication, the adjustment to the use of virtual platforms was viewed both positively and negatively. Service providers contended that success in transitioning to and using online support platforms with families seemed to depend on both the age of the child and the quality of relationship between the child/youth and service provider. Service providers indicated that younger children tended to have more difficulty transitioning to online social support groups relative to older children/youth who, in many cases, were more comfortable engaging in online dialogue. Transitioning from in-person to virtual support was deemed to be easier for families with whom service providers had a pre-existing relationship and strong rapport, as opposed to families that accessed service provision after the introduction of restrictions to face-to-face contact.

Along with benefits, service providers noted challenges with using online support platforms. These included communication barriers, individual/family lack of access to or comfort with technology, overuse of technology by children/youth, lower levels of interest/participation among families, and online fatigue. Such challenges created uncertainty among service providers about the utility of virtual support for all families and circumstances. In such instances of suboptimal or negative impacts of technology for support provision, service providers doubted their capacity to do their job as well as they could have in person. As an example, a service provider described a sense of helplessness intervening via virtual engagement:

Sometimes you would be watching a kid literally slamming their head on a wall and you can’t do anything because you’re on this side of the computer. Sometimes it was just about sitting with the parents and saying, “I see everything, [and] you’re [doing] a very good job…. You’re being everything your child needs you to be right now. This is hard and I see you and I hear you”. It was really hard to not be that person that could be in the home with them. Our service model is to be in there, doing the ‘nitty gritty’ with the parents, and working through it together.

Another service provider lamented about the shift from face-to-face to virtual programming:

Every [identified evening each week] was this party that everybody went to. I have been doing this for fifteen years and I always look forward to [that] night, and I would just love going around the recreation center, and seeing all the social skills groups and the parents looking so happy. Here’s all this range of parents meeting in their very normal environment, and having coffee and tea and it’s all support. I think that was a big loss for me personally as a clinician.

Family Adjustment

Adjustment to the pandemic was experienced in varying ways by individuals and families. Most parents indicated that their child adjusted to required protocols such as masking, social distancing and washing hands, though some indicated the need for prompting and/or assistance. In a few cases, parents reported needing to continually provide guidance and/or reinforcement to ensure their child’s compliance with safety protocols. Several parents further stated that their child’s difficulty adhering to protocols resulted in decreased outings and in turn, greater social isolation:

We don’t take [the autistic child out of the home] anymore. He doesn’t do really well with masks. I don’t want to risk tak[ing] him out and then he will have a meltdown.

The prolonged duration of the pandemic was reported to require ingenuity and persistence by parents in seeking strategies to meet their child’s pressing, and in some cases, shifting needs. Some parents described organizing “safe” social gatherings (e.g., socially distanced activities), and strategically setting up occasions for social connection, as needed, to support child/youth wellness. One parent utilized increased time at home during the pandemic to teach her child household skills such as cooking, dishwashing, house cleaning and laundry.

To help manage and cope with additional family caregiver tasks and strains, parents variably relied on government resources (as available), and in some cases, used these resources to fund needed supports. While such resource availability differed among families, support sometimes was provided by relatives, neighbours, privately-funded services and/or other resources in the community. Learning to be independently resourceful and a sole (or predominantly sole) caregiver during the pandemic was consistently described as difficult, and was especially so for those who had previously relied heavily on formal supports (e.g., therapeutic services, respite care) to address the daily care needs of their child and, in particular, those whose child had complex care needs.