More From Forbes

Why homework doesn't seem to boost learning--and how it could.

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

Some schools are eliminating homework, citing research showing it doesn’t do much to boost achievement. But maybe teachers just need to assign a different kind of homework.

In 2016, a second-grade teacher in Texas delighted her students—and at least some of their parents—by announcing she would no longer assign homework. “Research has been unable to prove that homework improves student performance,” she explained.

The following year, the superintendent of a Florida school district serving 42,000 students eliminated homework for all elementary students and replaced it with twenty minutes of nightly reading, saying she was basing her decision on “solid research about what works best in improving academic achievement in students.”

Many other elementary schools seem to have quietly adopted similar policies. Critics have objected that even if homework doesn’t increase grades or test scores, it has other benefits, like fostering good study habits and providing parents with a window into what kids are doing in school.

Those arguments have merit, but why doesn’t homework boost academic achievement? The research cited by educators just doesn’t seem to make sense. If a child wants to learn to play the violin, it’s obvious she needs to practice at home between lessons (at least, it’s obvious to an adult). And psychologists have identified a range of strategies that help students learn, many of which seem ideally suited for homework assignments.

For example, there’s something called “ retrieval practice ,” which means trying to recall information you’ve already learned. The optimal time to engage in retrieval practice is not immediately after you’ve acquired information but after you’ve forgotten it a bit—like, perhaps, after school. A homework assignment could require students to answer questions about what was covered in class that day without consulting their notes. Research has found that retrieval practice and similar learning strategies are far more powerful than simply rereading or reviewing material.

One possible explanation for the general lack of a boost from homework is that few teachers know about this research. And most have gotten little training in how and why to assign homework. These are things that schools of education and teacher-prep programs typically don’t teach . So it’s quite possible that much of the homework teachers assign just isn’t particularly effective for many students.

Even if teachers do manage to assign effective homework, it may not show up on the measures of achievement used by researchers—for example, standardized reading test scores. Those tests are designed to measure general reading comprehension skills, not to assess how much students have learned in specific classes. Good homework assignments might have helped a student learn a lot about, say, Ancient Egypt. But if the reading passages on a test cover topics like life in the Arctic or the habits of the dormouse, that student’s test score may well not reflect what she’s learned.

The research relied on by those who oppose homework has actually found it has a modest positive effect at the middle and high school levels—just not in elementary school. But for the most part, the studies haven’t looked at whether it matters what kind of homework is assigned or whether there are different effects for different demographic student groups. Focusing on those distinctions could be illuminating.

A study that looked specifically at math homework , for example, found it boosted achievement more in elementary school than in middle school—just the opposite of the findings on homework in general. And while one study found that parental help with homework generally doesn’t boost students’ achievement—and can even have a negative effect— another concluded that economically disadvantaged students whose parents help with homework improve their performance significantly.

That seems to run counter to another frequent objection to homework, which is that it privileges kids who are already advantaged. Well-educated parents are better able to provide help, the argument goes, and it’s easier for affluent parents to provide a quiet space for kids to work in—along with a computer and internet access . While those things may be true, not assigning homework—or assigning ineffective homework—can end up privileging advantaged students even more.

Students from less educated families are most in need of the boost that effective homework can provide, because they’re less likely to acquire academic knowledge and vocabulary at home. And homework can provide a way for lower-income parents—who often don’t have time to volunteer in class or participate in parents’ organizations—to forge connections to their children’s schools. Rather than giving up on homework because of social inequities, schools could help parents support homework in ways that don’t depend on their own knowledge—for example, by recruiting others to help, as some low-income demographic groups have been able to do . Schools could also provide quiet study areas at the end of the day, and teachers could assign homework that doesn’t rely on technology.

Another argument against homework is that it causes students to feel overburdened and stressed. While that may be true at schools serving affluent populations, students at low-performing ones often don’t get much homework at all—even in high school. One study found that lower-income ninth-graders “consistently described receiving minimal homework—perhaps one or two worksheets or textbook pages, the occasional project, and 30 minutes of reading per night.” And if they didn’t complete assignments, there were few consequences. I discovered this myself when trying to tutor students in writing at a high-poverty high school. After I expressed surprise that none of the kids I was working with had completed a brief writing assignment, a teacher told me, “Oh yeah—I should have told you. Our students don’t really do homework.”

If and when disadvantaged students get to college, their relative lack of study skills and good homework habits can present a serious handicap. After noticing that black and Hispanic students were failing her course in disproportionate numbers, a professor at the University of North Carolina decided to make some changes , including giving homework assignments that required students to quiz themselves without consulting their notes. Performance improved across the board, but especially for students of color and the disadvantaged. The gap between black and white students was cut in half, and the gaps between Hispanic and white students—along with that between first-generation college students and others—closed completely.

There’s no reason this kind of support should wait until students get to college. To be most effective—both in terms of instilling good study habits and building students’ knowledge—homework assignments that boost learning should start in elementary school.

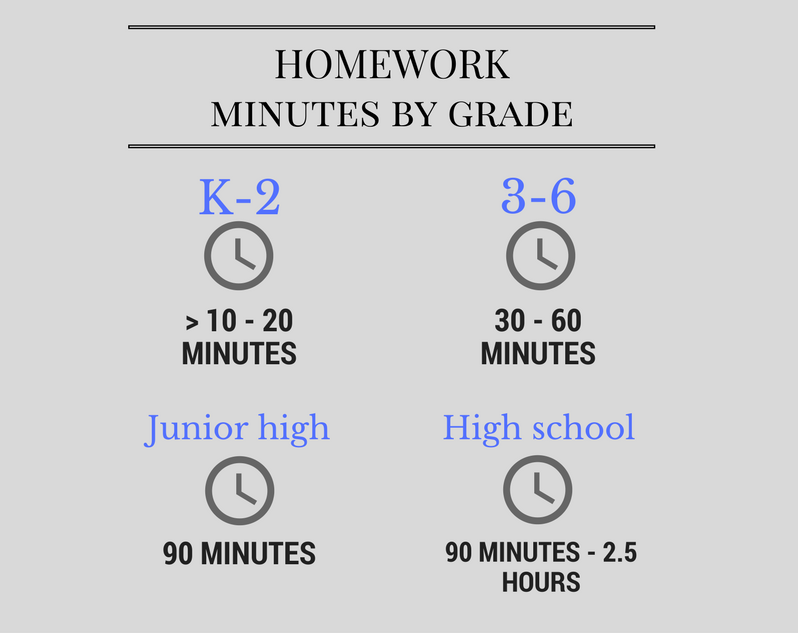

Some argue that young children just need time to chill after a long day at school. But the “ten-minute rule”—recommended by homework researchers—would have first graders doing ten minutes of homework, second graders twenty minutes, and so on. That leaves plenty of time for chilling, and even brief assignments could have a significant impact if they were well-designed.

But a fundamental problem with homework at the elementary level has to do with the curriculum, which—partly because of standardized testing— has narrowed to reading and math. Social studies and science have been marginalized or eliminated, especially in schools where test scores are low. Students spend hours every week practicing supposed reading comprehension skills like “making inferences” or identifying “author’s purpose”—the kinds of skills that the tests try to measure—with little or no attention paid to content.

But as research has established, the most important component in reading comprehension is knowledge of the topic you’re reading about. Classroom time—or homework time—spent on illusory comprehension “skills” would be far better spent building knowledge of the very subjects schools have eliminated. Even if teachers try to take advantage of retrieval practice—say, by asking students to recall what they’ve learned that day about “making comparisons” or “sequence of events”—it won’t have much impact.

If we want to harness the potential power of homework—particularly for disadvantaged students—we’ll need to educate teachers about what kind of assignments actually work. But first, we’ll need to start teaching kids something substantive about the world, beginning as early as possible.

- Editorial Standards

- Reprints & Permissions

Does homework really work?

by: Leslie Crawford | Updated: December 12, 2023

Print article

You know the drill. It’s 10:15 p.m., and the cardboard-and-toothpick Golden Gate Bridge is collapsing. The pages of polynomials have been abandoned. The paper on the Battle of Waterloo seems to have frozen in time with Napoleon lingering eternally over his breakfast at Le Caillou. Then come the tears and tantrums — while we parents wonder, Does the gain merit all this pain? Is this just too much homework?

However the drama unfolds night after night, year after year, most parents hold on to the hope that homework (after soccer games, dinner, flute practice, and, oh yes, that childhood pastime of yore known as playing) advances their children academically.

But what does homework really do for kids? Is the forest’s worth of book reports and math and spelling sheets the average American student completes in their 12 years of primary schooling making a difference? Or is it just busywork?

Homework haterz

Whether or not homework helps, or even hurts, depends on who you ask. If you ask my 12-year-old son, Sam, he’ll say, “Homework doesn’t help anything. It makes kids stressed-out and tired and makes them hate school more.”

Nothing more than common kid bellyaching?

Maybe, but in the fractious field of homework studies, it’s worth noting that Sam’s sentiments nicely synopsize one side of the ivory tower debate. Books like The End of Homework , The Homework Myth , and The Case Against Homework the film Race to Nowhere , and the anguished parent essay “ My Daughter’s Homework is Killing Me ” make the case that homework, by taking away precious family time and putting kids under unneeded pressure, is an ineffective way to help children become better learners and thinkers.

One Canadian couple took their homework apostasy all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada. After arguing that there was no evidence that it improved academic performance, they won a ruling that exempted their two children from all homework.

So what’s the real relationship between homework and academic achievement?

How much is too much?

To answer this question, researchers have been doing their homework on homework, conducting and examining hundreds of studies. Chris Drew Ph.D., founder and editor at The Helpful Professor recently compiled multiple statistics revealing the folly of today’s after-school busy work. Does any of the data he listed below ring true for you?

• 45 percent of parents think homework is too easy for their child, primarily because it is geared to the lowest standard under the Common Core State Standards .

• 74 percent of students say homework is a source of stress , defined as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss, and stomach problems.

• Students in high-performing high schools spend an average of 3.1 hours a night on homework , even though 1 to 2 hours is the optimal duration, according to a peer-reviewed study .

Not included in the list above is the fact many kids have to abandon activities they love — like sports and clubs — because homework deprives them of the needed time to enjoy themselves with other pursuits.

Conversely, The Helpful Professor does list a few pros of homework, noting it teaches discipline and time management, and helps parents know what’s being taught in the class.

The oft-bandied rule on homework quantity — 10 minutes a night per grade (starting from between 10 to 20 minutes in first grade) — is listed on the National Education Association’s website and the National Parent Teacher Association’s website , but few schools follow this rule.

Do you think your child is doing excessive homework? Harris Cooper Ph.D., author of a meta-study on homework , recommends talking with the teacher. “Often there is a miscommunication about the goals of homework assignments,” he says. “What appears to be problematic for kids, why they are doing an assignment, can be cleared up with a conversation.” Also, Cooper suggests taking a careful look at how your child is doing the assignments. It may seem like they’re taking two hours, but maybe your child is wandering off frequently to get a snack or getting distracted.

Less is often more

If your child is dutifully doing their work but still burning the midnight oil, it’s worth intervening to make sure your child gets enough sleep. A 2012 study of 535 high school students found that proper sleep may be far more essential to brain and body development.

For elementary school-age children, Cooper’s research at Duke University shows there is no measurable academic advantage to homework. For middle-schoolers, Cooper found there is a direct correlation between homework and achievement if assignments last between one to two hours per night. After two hours, however, achievement doesn’t improve. For high schoolers, Cooper’s research suggests that two hours per night is optimal. If teens have more than two hours of homework a night, their academic success flatlines. But less is not better. The average high school student doing homework outperformed 69 percent of the students in a class with no homework.

Many schools are starting to act on this research. A Florida superintendent abolished homework in her 42,000 student district, replacing it with 20 minutes of nightly reading. She attributed her decision to “ solid research about what works best in improving academic achievement in students .”

More family time

A 2020 survey by Crayola Experience reports 82 percent of children complain they don’t have enough quality time with their parents. Homework deserves much of the blame. “Kids should have a chance to just be kids and do things they enjoy, particularly after spending six hours a day in school,” says Alfie Kohn, author of The Homework Myth . “It’s absurd to insist that children must be engaged in constructive activities right up until their heads hit the pillow.”

By far, the best replacement for homework — for both parents and children — is bonding, relaxing time together.

Homes Nearby

Homes for rent and sale near schools

How families of color can fight for fair discipline in school

Dealing with teacher bias

The most important school data families of color need to consider

Yes! Sign me up for updates relevant to my child's grade.

Please enter a valid email address

Thank you for signing up!

Server Issue: Please try again later. Sorry for the inconvenience

- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty/Staff

News and Media

- News & Media Home

- Research Stories

- School's In

- In the Media

You are here

More than two hours of homework may be counterproductive, research suggests.

A Stanford education researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter. "Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good," wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education . The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students' views on homework. Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year. Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night. "The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students' advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being," Pope wrote. Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school. Their study found that too much homework is associated with: • Greater stress : 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor. • Reductions in health : In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems. • Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits : Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were "not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills," according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy. A balancing act The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills. Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as "pointless" or "mindless" in order to keep their grades up. "This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points," said Pope, who is also a co-founder of Challenge Success , a nonprofit organization affiliated with the GSE that conducts research and works with schools and parents to improve students' educational experiences.. Pope said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said. "Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development," wrote Pope. High-performing paradox In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. "Young people are spending more time alone," they wrote, "which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities." Student perspectives The researchers say that while their open-ended or "self-reporting" methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for "typical adolescent complaining" – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe. The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Clifton B. Parker is a writer at the Stanford News Service .

More Stories

⟵ Go to all Research Stories

Get the Educator

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Stanford Graduate School of Education

482 Galvez Mall Stanford, CA 94305-3096 Tel: (650) 723-2109

- Contact Admissions

- GSE Leadership

- Site Feedback

- Web Accessibility

- Career Resources

- Faculty Open Positions

- Explore Courses

- Academic Calendar

- Office of the Registrar

- Cubberley Library

- StanfordWho

- StanfordYou

Improving lives through learning

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

The Cult of Homework

America’s devotion to the practice stems in part from the fact that it’s what today’s parents and teachers grew up with themselves.

America has long had a fickle relationship with homework. A century or so ago, progressive reformers argued that it made kids unduly stressed , which later led in some cases to district-level bans on it for all grades under seventh. This anti-homework sentiment faded, though, amid mid-century fears that the U.S. was falling behind the Soviet Union (which led to more homework), only to resurface in the 1960s and ’70s, when a more open culture came to see homework as stifling play and creativity (which led to less). But this didn’t last either: In the ’80s, government researchers blamed America’s schools for its economic troubles and recommended ramping homework up once more.

The 21st century has so far been a homework-heavy era, with American teenagers now averaging about twice as much time spent on homework each day as their predecessors did in the 1990s . Even little kids are asked to bring school home with them. A 2015 study , for instance, found that kindergarteners, who researchers tend to agree shouldn’t have any take-home work, were spending about 25 minutes a night on it.

But not without pushback. As many children, not to mention their parents and teachers, are drained by their daily workload, some schools and districts are rethinking how homework should work—and some teachers are doing away with it entirely. They’re reviewing the research on homework (which, it should be noted, is contested) and concluding that it’s time to revisit the subject.

Read: My daughter’s homework is killing me

Hillsborough, California, an affluent suburb of San Francisco, is one district that has changed its ways. The district, which includes three elementary schools and a middle school, worked with teachers and convened panels of parents in order to come up with a homework policy that would allow students more unscheduled time to spend with their families or to play. In August 2017, it rolled out an updated policy, which emphasized that homework should be “meaningful” and banned due dates that fell on the day after a weekend or a break.

“The first year was a bit bumpy,” says Louann Carlomagno, the district’s superintendent. She says the adjustment was at times hard for the teachers, some of whom had been doing their job in a similar fashion for a quarter of a century. Parents’ expectations were also an issue. Carlomagno says they took some time to “realize that it was okay not to have an hour of homework for a second grader—that was new.”

Most of the way through year two, though, the policy appears to be working more smoothly. “The students do seem to be less stressed based on conversations I’ve had with parents,” Carlomagno says. It also helps that the students performed just as well on the state standardized test last year as they have in the past.

Earlier this year, the district of Somerville, Massachusetts, also rewrote its homework policy, reducing the amount of homework its elementary and middle schoolers may receive. In grades six through eight, for example, homework is capped at an hour a night and can only be assigned two to three nights a week.

Jack Schneider, an education professor at the University of Massachusetts at Lowell whose daughter attends school in Somerville, is generally pleased with the new policy. But, he says, it’s part of a bigger, worrisome pattern. “The origin for this was general parental dissatisfaction, which not surprisingly was coming from a particular demographic,” Schneider says. “Middle-class white parents tend to be more vocal about concerns about homework … They feel entitled enough to voice their opinions.”

Schneider is all for revisiting taken-for-granted practices like homework, but thinks districts need to take care to be inclusive in that process. “I hear approximately zero middle-class white parents talking about how homework done best in grades K through two actually strengthens the connection between home and school for young people and their families,” he says. Because many of these parents already feel connected to their school community, this benefit of homework can seem redundant. “They don’t need it,” Schneider says, “so they’re not advocating for it.”

That doesn’t mean, necessarily, that homework is more vital in low-income districts. In fact, there are different, but just as compelling, reasons it can be burdensome in these communities as well. Allison Wienhold, who teaches high-school Spanish in the small town of Dunkerton, Iowa, has phased out homework assignments over the past three years. Her thinking: Some of her students, she says, have little time for homework because they’re working 30 hours a week or responsible for looking after younger siblings.

As educators reduce or eliminate the homework they assign, it’s worth asking what amount and what kind of homework is best for students. It turns out that there’s some disagreement about this among researchers, who tend to fall in one of two camps.

In the first camp is Harris Cooper, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University. Cooper conducted a review of the existing research on homework in the mid-2000s , and found that, up to a point, the amount of homework students reported doing correlates with their performance on in-class tests. This correlation, the review found, was stronger for older students than for younger ones.

This conclusion is generally accepted among educators, in part because it’s compatible with “the 10-minute rule,” a rule of thumb popular among teachers suggesting that the proper amount of homework is approximately 10 minutes per night, per grade level—that is, 10 minutes a night for first graders, 20 minutes a night for second graders, and so on, up to two hours a night for high schoolers.

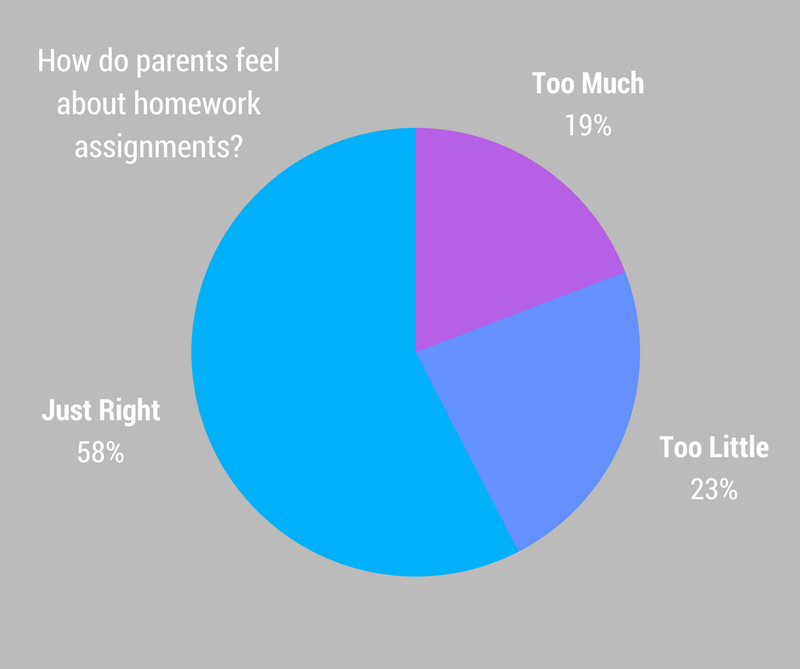

In Cooper’s eyes, homework isn’t overly burdensome for the typical American kid. He points to a 2014 Brookings Institution report that found “little evidence that the homework load has increased for the average student”; onerous amounts of homework, it determined, are indeed out there, but relatively rare. Moreover, the report noted that most parents think their children get the right amount of homework, and that parents who are worried about under-assigning outnumber those who are worried about over-assigning. Cooper says that those latter worries tend to come from a small number of communities with “concerns about being competitive for the most selective colleges and universities.”

According to Alfie Kohn, squarely in camp two, most of the conclusions listed in the previous three paragraphs are questionable. Kohn, the author of The Homework Myth: Why Our Kids Get Too Much of a Bad Thing , considers homework to be a “reliable extinguisher of curiosity,” and has several complaints with the evidence that Cooper and others cite in favor of it. Kohn notes, among other things, that Cooper’s 2006 meta-analysis doesn’t establish causation, and that its central correlation is based on children’s (potentially unreliable) self-reporting of how much time they spend doing homework. (Kohn’s prolific writing on the subject alleges numerous other methodological faults.)

In fact, other correlations make a compelling case that homework doesn’t help. Some countries whose students regularly outperform American kids on standardized tests, such as Japan and Denmark, send their kids home with less schoolwork , while students from some countries with higher homework loads than the U.S., such as Thailand and Greece, fare worse on tests. (Of course, international comparisons can be fraught because so many factors, in education systems and in societies at large, might shape students’ success.)

Kohn also takes issue with the way achievement is commonly assessed. “If all you want is to cram kids’ heads with facts for tomorrow’s tests that they’re going to forget by next week, yeah, if you give them more time and make them do the cramming at night, that could raise the scores,” he says. “But if you’re interested in kids who know how to think or enjoy learning, then homework isn’t merely ineffective, but counterproductive.”

His concern is, in a way, a philosophical one. “The practice of homework assumes that only academic growth matters, to the point that having kids work on that most of the school day isn’t enough,” Kohn says. What about homework’s effect on quality time spent with family? On long-term information retention? On critical-thinking skills? On social development? On success later in life? On happiness? The research is quiet on these questions.

Another problem is that research tends to focus on homework’s quantity rather than its quality, because the former is much easier to measure than the latter. While experts generally agree that the substance of an assignment matters greatly (and that a lot of homework is uninspiring busywork), there isn’t a catchall rule for what’s best—the answer is often specific to a certain curriculum or even an individual student.

Given that homework’s benefits are so narrowly defined (and even then, contested), it’s a bit surprising that assigning so much of it is often a classroom default, and that more isn’t done to make the homework that is assigned more enriching. A number of things are preserving this state of affairs—things that have little to do with whether homework helps students learn.

Jack Schneider, the Massachusetts parent and professor, thinks it’s important to consider the generational inertia of the practice. “The vast majority of parents of public-school students themselves are graduates of the public education system,” he says. “Therefore, their views of what is legitimate have been shaped already by the system that they would ostensibly be critiquing.” In other words, many parents’ own history with homework might lead them to expect the same for their children, and anything less is often taken as an indicator that a school or a teacher isn’t rigorous enough. (This dovetails with—and complicates—the finding that most parents think their children have the right amount of homework.)

Barbara Stengel, an education professor at Vanderbilt University’s Peabody College, brought up two developments in the educational system that might be keeping homework rote and unexciting. The first is the importance placed in the past few decades on standardized testing, which looms over many public-school classroom decisions and frequently discourages teachers from trying out more creative homework assignments. “They could do it, but they’re afraid to do it, because they’re getting pressure every day about test scores,” Stengel says.

Second, she notes that the profession of teaching, with its relatively low wages and lack of autonomy, struggles to attract and support some of the people who might reimagine homework, as well as other aspects of education. “Part of why we get less interesting homework is because some of the people who would really have pushed the limits of that are no longer in teaching,” she says.

“In general, we have no imagination when it comes to homework,” Stengel says. She wishes teachers had the time and resources to remake homework into something that actually engages students. “If we had kids reading—anything, the sports page, anything that they’re able to read—that’s the best single thing. If we had kids going to the zoo, if we had kids going to parks after school, if we had them doing all of those things, their test scores would improve. But they’re not. They’re going home and doing homework that is not expanding what they think about.”

“Exploratory” is one word Mike Simpson used when describing the types of homework he’d like his students to undertake. Simpson is the head of the Stone Independent School, a tiny private high school in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, that opened in 2017. “We were lucky to start a school a year and a half ago,” Simpson says, “so it’s been easy to say we aren’t going to assign worksheets, we aren’t going assign regurgitative problem sets.” For instance, a half-dozen students recently built a 25-foot trebuchet on campus.

Simpson says he thinks it’s a shame that the things students have to do at home are often the least fulfilling parts of schooling: “When our students can’t make the connection between the work they’re doing at 11 o’clock at night on a Tuesday to the way they want their lives to be, I think we begin to lose the plot.”

When I talked with other teachers who did homework makeovers in their classrooms, I heard few regrets. Brandy Young, a second-grade teacher in Joshua, Texas, stopped assigning take-home packets of worksheets three years ago, and instead started asking her students to do 20 minutes of pleasure reading a night. She says she’s pleased with the results, but she’s noticed something funny. “Some kids,” she says, “really do like homework.” She’s started putting out a bucket of it for students to draw from voluntarily—whether because they want an additional challenge or something to pass the time at home.

Chris Bronke, a high-school English teacher in the Chicago suburb of Downers Grove, told me something similar. This school year, he eliminated homework for his class of freshmen, and now mostly lets students study on their own or in small groups during class time. It’s usually up to them what they work on each day, and Bronke has been impressed by how they’ve managed their time.

In fact, some of them willingly spend time on assignments at home, whether because they’re particularly engaged, because they prefer to do some deeper thinking outside school, or because they needed to spend time in class that day preparing for, say, a biology test the following period. “They’re making meaningful decisions about their time that I don’t think education really ever gives students the experience, nor the practice, of doing,” Bronke said.

The typical prescription offered by those overwhelmed with homework is to assign less of it—to subtract. But perhaps a more useful approach, for many classrooms, would be to create homework only when teachers and students believe it’s actually needed to further the learning that takes place in class—to start with nothing, and add as necessary.

- PEARSON INTERNATIONAL SCHOOLS

Should homework be banned? The big debate

Homework is a polarising topic. it can cause students to feel stressed or anxious. it adds extra pressure on teachers, who are often already struggling with their workloads. and, some parents resent the way homework can cut into family time at home. yet despite this,....

Homework is a polarising topic. It can cause students to feel stressed or anxious. It adds extra pressure on teachers, who are often already struggling with their workloads. And, some parents resent the way homework can cut into family time at home.

Yet despite this, homework is handed out in the vast majority of schools. And, many educators and parents believe it plays a vital role in reinforcing classroom learning. So what does the research say? Does homework really make a big difference in student learning?

Is homework effective in the first place?

This was the question posed by researchers at Rutgers University in a study published last year . Researchers measured student performance on homework and in exams over the course of eleven years – and the results showed an interesting trend.

The study found that as smartphones became more ubiquitous, homework became less effective.

While some students used smartphones to help them complete homework – and got good grades on their assignments as a result – there was a big dip in performance when it came to exams. On the contrary, students who didn’t use the internet to help them with their homework performed better on exams.

This has to do with the way we learn. When studying, it’s important for the brain to generate an answer – even if that answer is incorrect. The process of being corrected helps us to retain information. It contributes to a deep learning process that helps us store new content in our long term memory.

But if you look up the answer online and then simply write it down, chances are you won’t actually remember the answer – and won’t be able to reproduce it under exam conditions. This is called shallow processing.

So what does this mean for homework? Well, there’s the danger that homework could become useless if students use their smartphones to help them complete it. It’s not just about what students are learning, but rather, how they are learning.

How homework can help with lost learning

However if homework is carefully designed, it can be very effective in supporting what students are learning in class. Now, that’s more important than ever. Since education was heavily impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, teachers have found that there are large gaps in their students’ knowledge , as well as differing levels within classes. There is a lot of pressure for students to catch up. And, assigning additional work to be completed at home could be one way of filling in these gaps.

A meta-analysis of fifteen years of research on homework found that, overall, there was a positive correlation between homework and achievement. This was especially pronounced in secondary-age students. Other studies show that, compared to classes where homework isn’t given out, there’s a typical learning gain of 5-6 months for secondary students.

What’s more, the practice of doing homework helps to build effective study skills. It teaches students about time management, encourages responsibility, and instils the ability to learn independently.

The pushback on homework

Despite the positive effect that homework can have in some students, opponents argue that children and young people need time to relax and decompress after working hard all day at school.

And, there are some studies that show homework doesn’t have much benefit depending on the age and stage of learners. Homework researcher Professor John Hattie found that homework in primary schools makes no difference to learner achievement. Other activities at home can have just as much educational benefit, such as reading, or baking, or simply playing.

What’s more, too much homework can also have a negative effect on students’ mental health. A survey of over 4,000 students from 10 high-performing schools found that large amounts of homework contributed to academic stress, sleep deprivation and a lack of balance with socialising or practising hobbies.

As a result, many families have pushed back. A few years ago a homework strike in Spain made headlines around the world. Parents and children exercised their “constitutional right that families have to make what they consider to be the best decisions for family life.” The organisers of the boycott declared that children’s free time had disappeared. They considered that the pressures of homework were to blame.

Homework: ripe for reform?

Homework reform is certainly overdue. For homework to have real value, it needs to be clearly related to what students are learning in class. Students shouldn’t be able to look up the answers on their smartphones. And it’s important to get the balance right. The US rule of thumb is 10 minutes per grade . And for secondary age students, 90 minutes of homework a day is the ideal amount for improving academic performance.

Schools and parents must ensure that homework doesn’t interfere with a healthy balance of exercise, family time and downtime – especially after a difficult year of online learning and limited social interaction. Stressed out, anxious students just won’t learn as effectively, and overloading them with homework will do more harm than good.

So what is your approach to homework? How do you choose tasks to assign to your students? Is their rate of homework completion high – and do you think it makes a difference to their levels of educational achievement? Let us know what you think on our social channels!

Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash

Sign up to receive our blog updates

Like what you read and want to receive more articles like this direct to your inbox? Subscribe to our blog and we’ll send you a fortnightly digest of the blog posts you may have missed, plus links to free resources to support your teaching and learning.

I found this helpful

I did not find this helpful

In this article

- British curriculum

- IB curriculum

- School leaders

Maria has a PhD in writing from the University of Glasgow. She moved to Barcelona just after she finished her PhD and, like so many people, went into English teaching. She did that for a year and it was fun, but she quite quickly realised she didn’t want to pursue it long term. She now writes for a living, specialising in education and social media.

- Subscribe to BBC Science Focus Magazine

- Previous Issues

- Future tech

- Everyday science

- Planet Earth

- Newsletters

Should homework be banned?

Social media has sparked into life about whether children should be given homework - should students be freed from this daily chore? Dr Gerald Letendre, a professor of education at Pennsylvania State University, investigates.

We’ve all done it: pretended to leave an essay at home, or stayed up until 2am to finish a piece of coursework we’ve been ignoring for weeks. Homework, for some people, is seen as a chore that’s ‘wrecking kids’ or ‘killing parents’, while others think it is an essential part of a well-rounded education. The problem is far from new: public debates about homework have been raging since at least the early-1900s, and recently spilled over into a Twitter feud between Gary Lineker and Piers Morgan.

Ironically, the conversation surrounding homework often ignores the scientific ‘homework’ that researchers have carried out. Many detailed studies have been conducted, and can guide parents, teachers and administrators to make sensible decisions about how much work should be completed by students outside of the classroom.

So why does homework stir up such strong emotions? One reason is that, by its very nature, it is an intrusion of schoolwork into family life. I carried out a study in 2005, and found that the amount of time that children and adolescents spend in school, from nursery right up to the end of compulsory education, has greatly increased over the last century . This means that more of a child’s time is taken up with education, so family time is reduced. This increases pressure on the boundary between the family and the school.

Plus, the amount of homework that students receive appears to be increasing, especially in the early years when parents are keen for their children to play with friends and spend time with the family.

Finally, success in school has become increasingly important to success in life. Parents can use homework to promote, or exercise control over, their child’s academic trajectory, and hopefully ensure their future educational success. But this often leaves parents conflicted – they want their children to be successful in school, but they don’t want them to be stressed or upset because of an unmanageable workload.

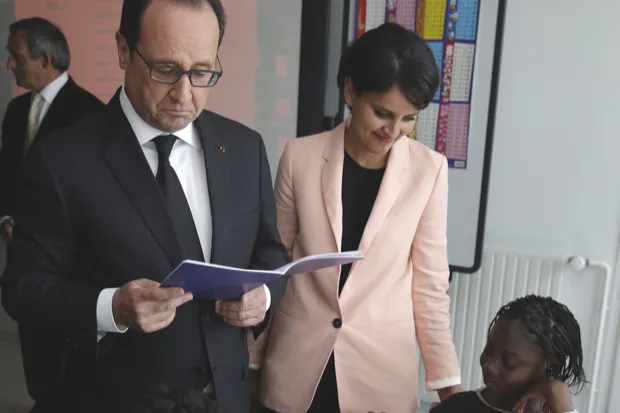

However, the issue isn’t simply down to the opinions of parents, children and their teachers – governments also like to get involved. In the autumn of 2012, French president François Hollande hit world headlines after making a comment about banning homework, ostensibly because it promoted inequality. The Chinese government has also toyed with a ban, because of concerns about excessive academic pressure being put on children.

The problem is, some politicians and national administrators regard regulatory policy in education as a solution for a wide array of social, economic and political issues, perhaps without considering the consequences for students and parents.

Does homework work?

Homework seems to generally have a positive effect for high school students, according to an extensive range of empirical literature. For example, Duke University’s Prof Harris Cooper carried out a meta-analysis using data from US schools, covering a period from 1987 to 2003. He found that homework offered a general beneficial impact on test scores and improvements in attitude, with a greater effect seen in older students. But dig deeper into the issue and a complex set of factors quickly emerges, related to how much homework students do, and exactly how they feel about it.

In 2009, Prof Ulrich Trautwein and his team at the University of Tübingen found that in order to establish whether homework is having any effect, researchers must take into account the differences both between and within classes . For example, a teacher may assign a good deal of homework to a lower-level class, producing an association between more homework and lower levels of achievement. Yet, within the same class, individual students may vary significantly in how much homework improves their baseline performance. Plus, there is the fact that some students are simply more efficient at completing their homework than others, and it becomes quite difficult to pinpoint just what type of homework, and how much of it, will affect overall academic performance.

Over the last century, the amount of time that children and adolescents spend in school has greatly increased

Gender is also a major factor. For example, a study of US high school students carried out by Prof Gary Natriello in the 1980s revealed that girls devote more time to homework than boys, while a follow-up study found that US girls tend to spend more time on mathematics homework than boys. Another study, this time of African-American students in the US, found that eighth grade (ages 13-14) girls were more likely to successfully manage both their tasks and emotions around schoolwork, and were more likely to finish homework.

So why do girls seem to respond more positively to homework? One possible answer proposed by Eunsook Hong of the University of Nevada in 2011 is that teachers tend to rate girls’ habits and attitudes towards work more favourably than boys’. This perception could potentially set up a positive feedback loop between teacher expectations and the children’s capacity for academic work based on gender, resulting in girls outperforming boys. All of this makes it particularly difficult to determine the extent to which homework is helping, though it is clear that simply increasing the time spent on assignments does not directly correspond to a universal increase in learning.

Can homework cause damage?

The lack of empirical data supporting homework in the early years of education, along with an emerging trend to assign more work to this age range, appears to be fuelling parental concerns about potential negative effects. But, aside from anecdotes of increased tension in the household, is there any evidence of this? Can doing too much homework actually damage children?

Evidence suggests extreme amounts of homework can indeed have serious effects on students’ health and well-being. A Chinese study carried out in 2010 found a link between excessive homework and sleep disruption: children who had less homework had better routines and more stable sleep schedules. A Canadian study carried out in 2015 by Isabelle Michaud found that high levels of homework were associated with a greater risk of obesity among boys, if they were already feeling stressed about school in general.

For useful revision guides and video clips to assist with learning, visit BBC Bitesize . This is a free online study resource for UK students from early years up to GCSEs and Scottish Highers.

It is also worth noting that too much homework can create negative effects that may undermine any positives. These negative consequences may not only affect the child, but also could also pile on the stress for the whole family, according to a recent study by Robert Pressman of the New England Centre for Pediatric Psychology. Parents were particularly affected when their perception of their own capacity to assist their children decreased.

What then, is the tipping point, and when does homework simply become too much for parents and children? Guidelines typically suggest that children in the first grade (six years old) should have no more that 10 minutes per night, and that this amount should increase by 10 minutes per school year. However, cultural norms may greatly affect what constitutes too much.

A study of children aged between 8 and 10 in Quebec defined high levels of homework as more than 30 minutes a night, but a study in China of children aged 5 to 11 deemed that two or more hours per night was excessive. It is therefore difficult to create a clear standard for what constitutes as too much homework, because cultural differences, school-related stress, and negative emotions within the family all appear to interact with how homework affects children.

Should we stop setting homework?

In my opinion, even though there are potential risks of negative effects, homework should not be banned. Small amounts, assigned with specific learning goals in mind and with proper parental support, can help to improve students’ performance. While some studies have generally found little evidence that homework has a positive effect on young children overall, a 2008 study by Norwegian researcher Marte Rønning found that even some very young children do receive some benefit. So simply banning homework would mean that any particularly gifted or motivated pupils would not be able to benefit from increased study. However, at the earliest ages, very little homework should be assigned. The decisions about how much and what type are best left to teachers and parents.

As a parent, it is important to clarify what goals your child’s teacher has for homework assignments. Teachers can assign work for different reasons – as an academic drill to foster better study habits, and unfortunately, as a punishment. The goals for each assignment should be made clear, and should encourage positive engagement with academic routines.

Parents should inform the teachers of how long the homework is taking, as teachers often incorrectly estimate the amount of time needed to complete an assignment, and how it is affecting household routines. For young children, positive teacher support and feedback is critical in establishing a student’s positive perception of homework and other academic routines. Teachers and parents need to be vigilant and ensure that homework routines do not start to generate patterns of negative interaction that erode students’ motivation.

Likewise, any positive effects of homework are dependent on several complex interactive factors, including the child’s personal motivation, the type of assignment, parental support and teacher goals. Creating an overarching policy to address every single situation is not realistic, and so homework policies tend to be fixated on the time the homework takes to complete. But rather than focusing on this, everyone would be better off if schools worked on fostering stronger communication between parents, teachers and students, allowing them to respond more sensitively to the child’s emotional and academic needs.

- Five brilliant science books for kids

- Will e-learning replace teachers?

Follow Science Focus on Twitter , Facebook , Instagram and Flipboard

Share this article

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy policy

- Cookies policy

- Code of conduct

- Magazine subscriptions

- Manage preferences

Does Homework Improve Academic Achievement?

- Share this story on facebook

- Share this story on twitter

- Share this story on reddit

- Share this story on linkedin

- Get this story's permalink

- Print this story

Educators should be thrilled by these numbers. Pleasing a majority of parents regarding homework and having equal numbers of dissenters shouting "too much!" and "too little!" is about as good as they can hope for.

But opinions cannot tell us whether homework works; only research can, which is why my colleagues and I have conducted a combined analysis of dozens of homework studies to examine whether homework is beneficial and what amount of homework is appropriate for our children.

The homework question is best answered by comparing students who are assigned homework with students assigned no homework but who are similar in other ways. The results of such studies suggest that homework can improve students' scores on the class tests that come at the end of a topic. Students assigned homework in 2nd grade did better on math, 3rd and 4th graders did better on English skills and vocabulary, 5th graders on social studies, 9th through 12th graders on American history, and 12th graders on Shakespeare.

Less authoritative are 12 studies that link the amount of homework to achievement, but control for lots of other factors that might influence this connection. These types of studies, often based on national samples of students, also find a positive link between time on homework and achievement.

Yet other studies simply correlate homework and achievement with no attempt to control for student differences. In 35 such studies, about 77 percent find the link between homework and achievement is positive. Most interesting, though, is these results suggest little or no relationship between homework and achievement for elementary school students.

Why might that be? Younger children have less developed study habits and are less able to tune out distractions at home. Studies also suggest that young students who are struggling in school take more time to complete homework assignments simply because these assignments are more difficult for them.

These recommendations are consistent with the conclusions reached by our analysis. Practice assignments do improve scores on class tests at all grade levels. A little amount of homework may help elementary school students build study habits. Homework for junior high students appears to reach the point of diminishing returns after about 90 minutes a night. For high school students, the positive line continues to climb until between 90 minutes and 2½ hours of homework a night, after which returns diminish.

Beyond achievement, proponents of homework argue that it can have many other beneficial effects. They claim it can help students develop good study habits so they are ready to grow as their cognitive capacities mature. It can help students recognize that learning can occur at home as well as at school. Homework can foster independent learning and responsible character traits. And it can give parents an opportunity to see what's going on at school and let them express positive attitudes toward achievement.

Opponents of homework counter that it can also have negative effects. They argue it can lead to boredom with schoolwork, since all activities remain interesting only for so long. Homework can deny students access to leisure activities that also teach important life skills. Parents can get too involved in homework -- pressuring their child and confusing him by using different instructional techniques than the teacher.

My feeling is that homework policies should prescribe amounts of homework consistent with the research evidence, but which also give individual schools and teachers some flexibility to take into account the unique needs and circumstances of their students and families. In general, teachers should avoid either extreme.

Link to this page

Copy and paste the URL below to share this page.

- Our Mission

Homework: No Proven Benefits

Why homework is a pointless and outdated habit.

This is an excerpt from Alfie Kohn's recently published book The Homework Myth: Why Our Kids Get Too Much of a Bad Thing. For one teacher's response to this excerpt, read In Defense of Homework: Is there Such a Thing as Too Much? .

It may surprise you, as it did me, to learn that no study has ever demonstrated any academic benefit to assigning homework before children are in high school. In fact, even in high school, the association between homework and achievement is weak -- and the data don't show that homework is responsible for higher achievement. (Correlation doesn't imply causation.)

Finally, there isn't a shred of evidence to support the folk wisdom that homework provides nonacademic benefits at any age -- for example, that it builds character, promotes self-discipline, or teaches good work habits. We're all familiar with the downside of homework: the frustration and exhaustion, the family conflict, time lost for other activities, and possible diminution of children's interest in learning. But the stubborn belief that all of this must be worth it, that the gain must outweigh the pain, relies on faith rather than evidence.

So why does homework continue to be assigned and accepted? Possible reasons include a lack of respect for research, a lack of respect for children (implicit in a determination to keep them busy after school), a lack of understanding about the nature of learning (implicit in the emphasis on practicing skills and the assertion that homework "reinforces" school lessons), or the top-down pressures to teach more stuff faster in order to pump up test scores so we can chant "We're number one!"

All of these explanations are plausible, but I think there's also something else responsible for our continuing to feed children this latter-day cod-liver oil. We don't ask challenging questions about homework because we don't ask challenging questions about most things. Too many of us sound like Robert Frost's neighbor, the man who "will not go behind his father's saying." Too many of us, when pressed about some habit or belief we've adopted, are apt to reply, "Well, that's just the way I was raised" -- as if it were impossible to critically examine the values one was taught. Too many of us, including some who work in the field of education, seem to have lost our capacity to be outraged by the outrageous; when handed foolish and destructive mandates, we respond by asking for guidance on how best to carry them out.

Passivity is a habit acquired early. From our first days in school we are carefully instructed in what has been called the "hidden curriculum": how to do what one is told and stay out of trouble. There are rewards, both tangible and symbolic, for those who behave properly and penalties for those who don't. As students, we're trained to sit still, listen to what the teacher says, run our highlighters across whatever words in the book we'll be required to commit to memory. Pretty soon, we become less likely to ask (or even wonder) whether what we're being taught really makes sense. We just want to know whether it's going to be on the test.

When we find ourselves unhappy with some practice or policy, we're encouraged to focus on incidental aspects of what's going on, to ask questions about the details of implementation -- how something will get done, or by whom, or on what schedule -- but not whether it should be done at all. The more that we attend to secondary concerns, the more the primary issues -- the overarching structures and underlying premises -- are strengthened. We're led to avoid the radical questions -- and I use that adjective in its original sense: Radical comes from the Latin word for "root." It's partly because we spend our time worrying about the tendrils that the weed continues to grow. Noam Chomsky put it this way: "The smart way to keep people passive and obedient is to strictly limit the spectrum of acceptable opinion, but allow very lively debate within that spectrum -- even encourage the more critical and dissident views. That gives people the sense that there's free thinking going on, while all the time the presuppositions of the system are being reinforced by the limits put on the range of the debate."

Parents have already been conditioned to accept most of what is done to their children at school, for example, and so their critical energies are confined to the periphery. Sometimes I entertain myself by speculating about how ingrained this pattern really is. If a school administrator were to announce that, starting next week, students will be made to stand outside in the rain and memorize the phone book, I suspect we parents would promptly speak up . . . to ask whether the Yellow Pages will be included. Or perhaps we'd want to know how much of their grade this activity will count for. One of the more outspoken moms might even demand to know whether her child will be permitted to wear a raincoat.

Our education system, meanwhile, is busily avoiding important topics in its own right. For every question that's asked in this field, there are other, more vital questions that are never raised. Educators weigh different techniques of "behavior management" but rarely examine the imperative to focus on behavior -- that is, observable actions -- rather than on reasons and needs and the children who have them. Teachers think about what classroom rules they ought to introduce but are unlikely to ask why they're doing so unilaterally, why students aren't participating in such decisions. It's probably not a coincidence that most schools of education require prospective teachers to take a course called Methods, but there is no course called Goals.

And so we return to the question of homework. Parents anxiously grill teachers about their policies on this topic, but they mostly ask about the details of the assignments their children will be made to do. If homework is a given, it's certainly understandable that one would want to make sure it's being done "correctly." But this begs the question of whether, and why, it should be a given. The willingness not to ask provides another explanation for how a practice can persist even if it hurts more than helps.

For their part, teachers regularly witness how many children are made miserable by homework and how many resist doing it. Some respond with sympathy and respect. Others reach for bribes and threats to compel students to turn in the assignments; indeed, they may insist these inducements are necessary: "If the kids weren't being graded, they'd never do it!" Even if true, this is less an argument for grades and other coercive tactics than an invitation to reconsider the value of those assignments. Or so one might think. However, teachers had to do homework when they were students, and they've likely been expected to give it at every school where they've worked. The idea that homework must be assigned is the premise, not the conclusion -- and it's a premise that's rarely examined by educators.

Unlike parents and teachers, scholars are a step removed from the classroom and therefore have the luxury of pursuing potentially uncomfortable areas of investigation. But few do. Instead, they are more likely to ask, "How much time should students spend on homework?" or "Which strategies will succeed in improving homework completion rates?," which is simply assumed to be desirable.

Policy groups, too, are more likely to act as cheerleaders than as thoughtful critics. The major document on the subject issued jointly by the National PTA and the National Education Association, for example, concedes that children often complain about homework, but never considers the possibility that their complaints may be justified. Parents are exhorted to "show your children that you think homework is important" -- regardless of whether it is, or even whether one really believes this is true -- and to praise them for compliance.

Health professionals, meanwhile, have begun raising concerns about the weight of children's backpacks and then recommending . . . exercises to strengthen their backs! This was also the tack taken by People magazine: An article about families struggling to cope with excessive homework was accompanied by a sidebar that offered some "ways to minimize the strain on young backs" -- for example, "pick a [back]pack with padded shoulder straps."

The People article reminds us that the popular press does occasionally -- cyclically -- take note of how much homework children have to do, and how varied and virulent are its effects. But such inquiries are rarely penetrating and their conclusions almost never rock the boat. Time magazine published a cover essay in 2003 entitled "The Homework Ate My Family." It opened with affecting and even alarming stories of homework's harms. Several pages later, however, it closed with a finger-wagging declaration that "both parents and students must be willing to embrace the 'work' component of homework -- to recognize the quiet satisfaction that comes from practice and drill." Likewise, an essay on the Family Education Network's Web site: "Yes, homework is sometimes dull, or too easy, or too difficult. That doesn't mean that it shouldn't be taken seriously." (One wonders what would have to be true before we'd be justified in not taking something seriously.)

Nor, apparently, are these questions seen as appropriate by most medical and mental health professionals. When a child resists doing homework -- or complying with other demands -- their job is to get the child back on track. Very rarely is there any inquiry into the value of the homework or the reasonableness of the demands.

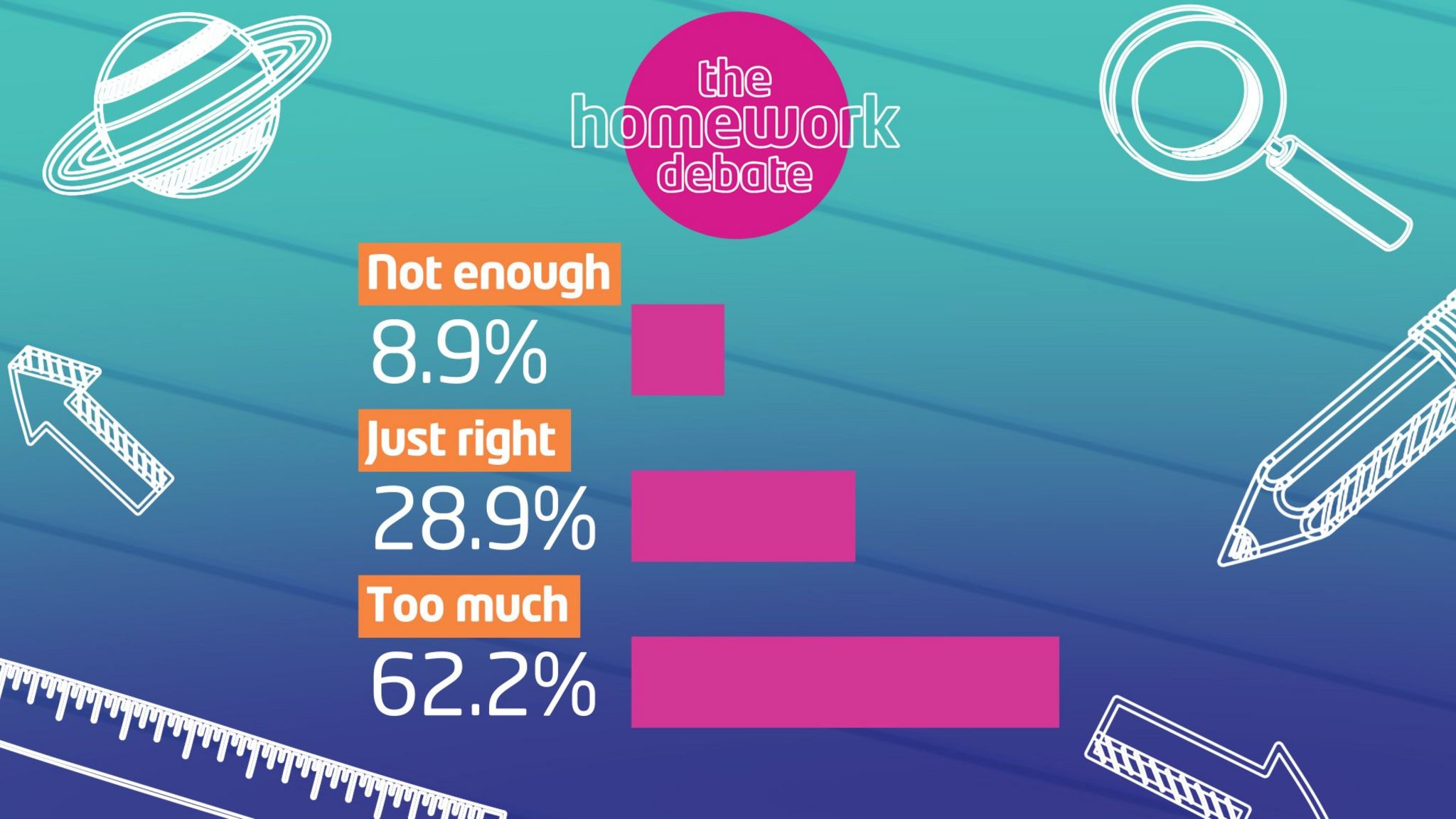

Sometimes parents are invited to talk to teachers about homework -- providing that their concerns are "appropriate." The same is true of formal opportunities for offering feedback. A list of sample survey questions offered to principals by the central office in one Colorado school district is typical. Parents were asked to indicate whether they agree or disagree with the following statements: "My child understands how to do his/her homework"; "Teachers at this school give me useful suggestions about how to help my child with schoolwork"; "Homework assignments allow me to see what my student is being taught and how he/she is learning"; and "The amount of homework my child receives is (choose one): too much/just right/too little."

The most striking feature of such a list is what isn't on it. Such a questionnaire seems to have been designed to illustrate Chomsky's point about encouraging lively discussion within a narrow spectrum of acceptable opinion, the better to reinforce the key presuppositions of the system. Parents' feedback is earnestly sought -- on these questions only. So, too, for the popular articles that criticize homework, or the parents who speak out: The focus is generally limited to how much is being assigned. I'm sympathetic to this concern, but I'm more struck by how it misses much of what matters. We sometimes forget that not everything that's destructive when done to excess is innocuous when done in moderation. Sometimes the problem is with what's being done, or at least the way it's being done, rather than just with how much of it is being done.

The more we are invited to think in Goldilocks terms (too much, too little, or just right?), the less likely we become to step back and ask the questions that count: What reason is there to think that any quantity of the kind of homework our kids are getting is really worth doing? What evidence exists to show that daily homework, regardless of its nature, is necessary for children to become better thinkers? Why did the students have no chance to participate in deciding which of their assignments ought to be taken home?

And: What if there was no homework at all?

ChatGPT for Teachers

Trauma-informed practices in schools, teacher well-being, cultivating diversity, equity, & inclusion, integrating technology in the classroom, social-emotional development, covid-19 resources, invest in resilience: summer toolkit, civics & resilience, all toolkits, degree programs, trauma-informed professional development, teacher licensure & certification, how to become - career information, classroom management, instructional design, lifestyle & self-care, online higher ed teaching, current events, the homework debate: how homework benefits students.

This post has been updated as of December 2017.

In another of our blog posts, The Case Against Homework , we articulated several points of view against homework as standard practice for teachers. However, a variety of lessons, content-related and beyond, can be taught or reinforced through homework and are worth exploring. Read on!

Four ways homework aids students’ academic achievement

Homework provides an opportunity for parents to interact with and understand the content their students are learning so they can provide another means of academic support for students. Memphis Parent writer Glenda Faye Pryor-Johnson says that, “When your child does homework, you do homework,” and notes that this is an opportunity for parents to model good behavior for their children.

Pryor-Johnson also identifies four qualities children develop when they complete homework that can help them become high-achieving students:

- Responsibility

- Time management

- Perseverance

- Self-esteem

While these cannot be measured on standardized tests, perseverance has garnered a lot of attention as an essential skill for successful students. Regular accomplishments like finishing homework build self-esteem, which aids students’ mental and physical health. Responsibility and time management are highly desirable qualities that benefit students long after they graduate.

NYU and Duke professors refute the idea that homework is unrelated to student success

In response to the National School Board Association’s Center for Public Education’s findings that homework was not conclusively related to student success, historian and NYU professor Diane Ravitch contends that the study’s true discovery was that students who did not complete homework or who lacked the resources to do so suffered poor outcomes.

Ravitch believes the study’s data only supports the idea that those who complete homework benefit from homework. She also cites additional benefits of homework: when else would students be allowed to engage thoughtfully with a text or write a complete essay? Constraints on class time require that such activities are given as outside assignments.

5 studies support a significant relationship between homework completion and academic success

Duke University professor Harris Cooper supports Ravitch’s assessment, saying that, “Across five studies, the average student who did homework had a higher unit test score than the students not doing homework.” Dr. Cooper and his colleagues analyzed dozens of studies on whether homework is beneficial in a 2006 publication, “Does Homework Improve Academic Achievement? A Synthesis of Research, 1987–2003. ”

This analysis found 12 less-authoritative studies that link achievement to time spent on homework, but control for many other factors that could influence the outcome. Finally, the research team identified 35 studies that found a positive correlation between homework and achievement, but only after elementary school. Dr. Cooper concluded that younger students might be less capable of benefiting from homework due to undeveloped study habits or other factors.

Recommended amount of homework varies by grade level

“Does Homework Improve Academic Achievement?” also identifies the amount homework that serves as a learning tool for students. While practice improves test scores at all grade levels, “Homework for junior high students appears to reach the point of diminishing returns after about 90 minutes a night. For high school students, the positive line continues to climb until between 90 minutes and 2.5 hours of homework a night, after which returns diminish.”

Dr. Cooper’s conclusion—homework is important, but discretion can and should be used when assigning it—addresses the valid concerns of homework critics. While the act of completing homework has benefits in terms of developing good habits in students, homework must prove useful for students so that they buy in to the process and complete their assignments. If students (or their parents) feel homework is a useless component of their learning, they will skip it—and miss out on the major benefits, content and otherwise, that homework has to offer.

Continue reading : Ending the Homework Debate: Expert Advice on What Works

Monica Fuglei is a graduate of the University of Nebraska in Omaha and a current adjunct faculty member of Arapahoe Community College in Colorado, where she teaches composition and creative writing.

You may also like to read

- The Homework Debate: The Case Against Homework

- Ending the Homework Debate: Expert Advice on What Works

- Elementary Students and Homework: How Much Is Too Much?

- Advice on Creating Homework Policies

- How Teachers Can Impart the Benefits of Students Working in Groups

- Homework Helps High School Students Most — But it Must Be Purposeful

Categorized as: Tips for Teachers and Classroom Resources

Tagged as: Leadership and Administration , Pros and Cons , Teacher-Parent Relationships

- Master's in Math and Science Education

- Online & Campus Bachelor's in Secondary Educa...

- Master's in PE, Sports & Athletics Administra...

Get Started Today!

- Centre Details

- Ask A Question

- Change Location

- Programs & More

The Pros and Cons of Homework

The dreaded word for students across the country—homework.

Homework has long been a source of debate, with parents, educators, and education specialists debating the advantages of at-home study. There are many pros and cons of homework. We’ve examined a few significant points to provide you with a summary of the benefits and disadvantages of homework.

Check Out The Pros and Cons of Homework

Pro 1: Homework Helps to Improve Student Achievement

Homework teaches students various beneficial skills that they will carry with them throughout their academic and professional life, from time management and organization to self-motivation and autonomous learning.

Homework helps students of all ages build critical study abilities that help them throughout their academic careers. Learning at home also encourages the development of good research habits while encouraging students to take ownership of their tasks.

If you’re finding that homework is becoming an issue at home, check out this article to learn how to tackle them before they get out of hand.

Con 1: Too Much Homework Can Negatively Affect Students

You’ll often hear from students that they’re stressed out by schoolwork. Stress becomes even more apparent as students get into higher grade levels.

A study conducted on high school student’s experiences found that high-achieving students found that too much homework leads to sleep deprivation and other health problems such as:

- Weight loss

- Stomach problems

More than half of students say that homework is their primary source of stress, and we know what stress can do on our bodies.

It’s been shown that excessive homework can lead to cheating. With too much homework, students end up copying off one another in an attempt to finish all their assignments.

Pro 2: Homework Helps to Reinforce Classroom Learning

Homework is most effective when it allows students to revise what they learn in class. Did you know that students typically retain only 50% of the information teachers provide in class?

Students need to apply that information to learn it.

Homework also helps students develop key skills that they’ll use throughout their lives:

- Accountability

- Time management

- Self-direction

- Critical thinking

- Independent problem-solving

The skills learned in homework can then be applied to other subjects and practical situations in students’ daily lives.

Con 2: Takes Away From Students Leisure Time

Children need free time. This free time allows children to relax and explore the world that they are living in. This free time also gives them valuable skills they wouldn’t learn in a classroom, such as riding a bike, reading a book, or socializing with friends and family.

Having leisure time teaches kids valuable skills that cannot be acquired when doing their homework at a computer.

Plus, students need to get enough exercise. Getting exercise can improve cognitive function, which might be hindered by sedentary activities such as homework.

Pro 3: Homework Gets Parents Involved with Children’s Learning

Homework helps parents track what their children are learning in school.

Also allows parents to see what their children’s academic strengths and weaknesses are. Homework can alert parents to any learning difficulties that their children might have, enabling them to provide assistance and modify their child’s learning approach as necessary.

Parents who help their children with homework will lead to higher academic performance, better social skills and behaviour, and greater self-confidence in their children.

Con 3: Homework Is Not Always Effective

Numerous researchers have attempted to evaluate the importance of homework and how it enhances academic performance. According to a study , homework in primary schools has a minimal effect since students pursue unrelated assignments instead of solidifying what they have already learned.

Mental health experts agree heavy homework loads have the capacity to do more harm than good for students. But they also say the answer may not be to eliminate homework altogether. So, unfortunately for students, homework is here to stay.

You can learn more about the pro and cons of homework here.

Need Help with Completing Homework Effectively?