If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

AP®︎/College Macroeconomics

Course: ap®︎/college macroeconomics > unit 1.

- Production possibilities curve

- Opportunity cost

- Increasing opportunity cost

- PPCs for increasing, decreasing and constant opportunity cost

- Production Possibilities Curve as a model of a country's economy

Lesson summary: Opportunity cost and the PPC

- Opportunity cost and the PPC

Key Equations and Calculations: Calculating opportunity costs:

Common misperceptions.

- Not all costs are monetary costs. Opportunity costs are expressed in terms of how much of another good, service, or activity must be given up in order to pursue or produce another activity or good. For example, when you head out to see a movie, the cost of that activity is not just the price of a movie ticket, but the value of the next best alternative, such as cleaning your room.

- Going from an inefficient amount of production to an efficient amount of production is not economic growth. For example, suppose an economy can make two goods: chocolate donuts and cattle prods. But half of their donut machines aren’t being used, so they aren’t fully using all of their resources. Graphically, that would be represented by a combination of goods in the interior of their PPC. If they then put all of those donut machines to work, they aren’t acquiring more resources (which is what we mean by economic growth). Instead, they are just using their resources more efficiently and moving to a new point on the PPC.

- On the other hand, if this economy is making as many donuts and cattle prods as it can, and it acquires more donut machines, it has experienced economic growth because it now has more resources (in this case, capital) available. This would be represented in a PPC graph as a shift outward of the entire PPC curve.

Discussion Questions

- How would you show with a PPC that a country has constant opportunity costs of production?

- Using a correctly labeled PPC model, show an economy that has increasing opportunity costs that can produce cattle prods and chocolate donuts that is underutilizing its labor.

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

2.2: The Production Possibilities Curve

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 21532

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Learning Objective

- Explain the concept of the production possibilities curve and understand the implications of its downward slope and bowed-out shape.

- Use the production possibilities model to distinguish between full employment and situations of idle factors of production and between efficient and inefficient production.

- Understand specialization and its relationship to the production possibilities model and comparative advantage.

An economy’s factors of production are scarce; they cannot produce an unlimited quantity of goods and services. A production possibilities curve is a graphical representation of the alternative combinations of goods and services an economy can produce. It illustrates the production possibilities model. In drawing the production possibilities curve, we shall assume that the economy can produce only two goods and that the quantities of factors of production and the technology available to the economy are fixed.

Constructing a Production Possibilities Curve

To construct a production possibilities curve, we will begin with the case of a hypothetical firm, Alpine Sports, Inc., a specialized sports equipment manufacturer. Christie Ryder began the business 15 years ago with a single ski production facility near Killington ski resort in central Vermont. Ski sales grew, and she also saw demand for snowboards rising—particularly after snowboard competition events were included in the 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City. She added a second plant in a nearby town. The second plant, while smaller than the first, was designed to produce snowboards as well as skis. She also modified the first plant so that it could produce both snowboards and skis. Two years later she added a third plant in another town. While even smaller than the second plant, the third was primarily designed for snowboard production but could also produce skis.

We can think of each of Ms. Ryder’s three plants as a miniature economy and analyze them using the production possibilities model. We assume that the factors of production and technology available to each of the plants operated by Alpine Sports are unchanged.

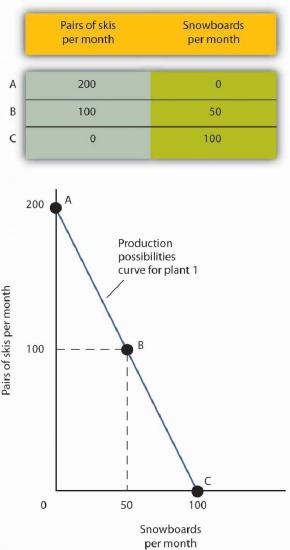

Suppose the first plant, Plant 1, can produce 200 pairs of skis per month when it produces only skis. When devoted solely to snowboards, it produces 100 snowboards per month. It can produce skis and snowboards simultaneously as well.

The table in Figure 2.2 gives three combinations of skis and snowboards that Plant 1 can produce each month. Combination A involves devoting the plant entirely to ski production; combination C means shifting all of the plant’s resources to snowboard production; combination B involves the production of both goods. These values are plotted in a production possibilities curve for Plant 1. The curve is a downward-sloping straight line, indicating that there is a linear, negative relationship between the production of the two goods.

Neither skis nor snowboards is an independent or a dependent variable in the production possibilities model; we can assign either one to the vertical or to the horizontal axis. Here, we have placed the number of pairs of skis produced per month on the vertical axis and the number of snowboards produced per month on the horizontal axis.

The negative slope of the production possibilities curve reflects the scarcity of the plant’s capital and labor. Producing more snowboards requires shifting resources out of ski production and thus producing fewer skis. Producing more skis requires shifting resources out of snowboard production and thus producing fewer snowboards.

The slope of Plant 1’s production possibilities curve measures the rate at which Alpine Sports must give up ski production to produce additional snowboards. Because the production possibilities curve for Plant 1 is linear, we can compute the slope between any two points on the curve and get the same result. Between points A and B, for example, the slope equals −2 pairs of skis/snowboard (equals −100 pairs of skis/50 snowboards). (Many students are helped when told to read this result as “−2 pairs of skis per snowboard.”) We get the same value between points B and C, and between points A and C.

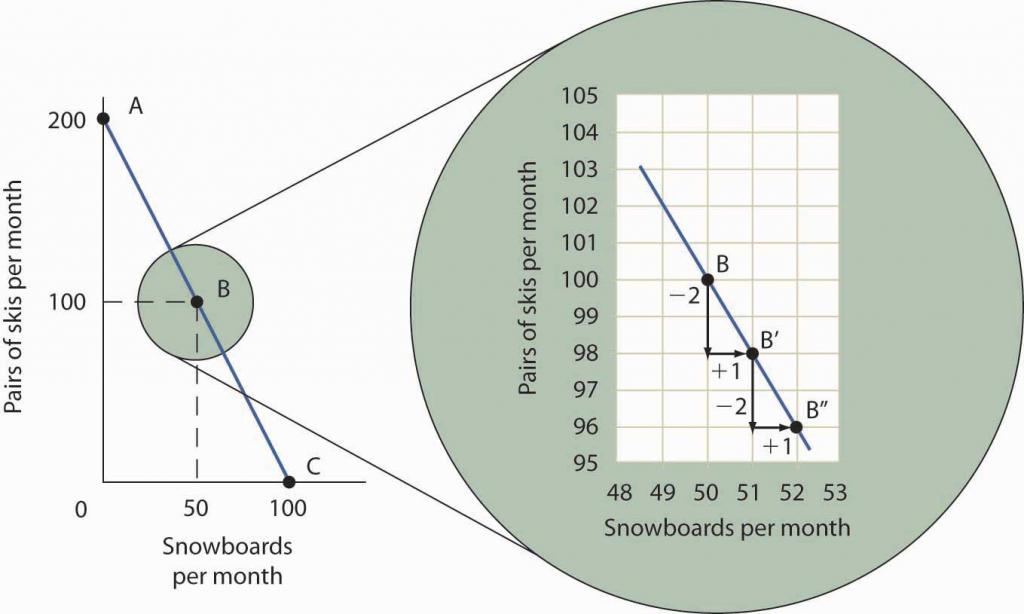

To see this relationship more clearly, examine Figure 2.3. Suppose Plant 1 is producing 100 pairs of skis and 50 snowboards per month at point B. Now consider what would happen if Ms. Ryder decided to produce 1 more snowboard per month. The segment of the curve around point B is magnified in Figure 2.3. The slope between points B and B′ is −2 pairs of skis/snowboard. Producing 1 additional snowboard at point B′ requires giving up 2 pairs of skis. We can think of this as the opportunity cost of producing an additional snowboard at Plant 1. This opportunity cost equals the absolute value of the slope of the production possibilities curve.

Figure 2.3 The Slope of a Production Possibilities Curve

The slope of the linear production possibilities curve in Figure 2.2 is constant; it is −2 pairs of skis/snowboard. In the section of the curve shown here, the slope can be calculated between points B and B′. Expanding snowboard production to 51 snowboards per month from 50 snowboards per month requires a reduction in ski production to 98 pairs of skis per month from 100 pairs. The slope equals −2 pairs of skis/snowboard (that is, it must give up two pairs of skis to free up the resources necessary to produce one additional snowboard). To shift from B′ to B″, Alpine Sports must give up two more pairs of skis per snowboard. The absolute value of the slope of a production possibilities curve measures the opportunity cost of an additional unit of the good on the horizontal axis measured in terms of the quantity of the good on the vertical axis that must be forgone.

The absolute value of the slope of any production possibilities curve equals the opportunity cost of an additional unit of the good on the horizontal axis. It is the amount of the good on the vertical axis that must be given up in order to free up the resources required to produce one more unit of the good on the horizontal axis. We will make use of this important fact as we continue our investigation of the production possibilities curve.

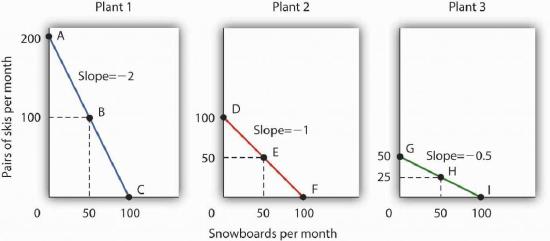

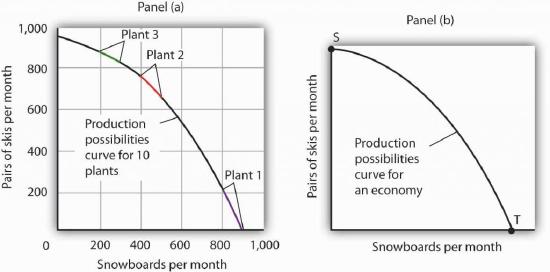

Figure 2.4 shows production possibilities curves for each of the firm’s three plants. Each of the plants, if devoted entirely to snowboards, could produce 100 snowboards. Plants 2 and 3, if devoted exclusively to ski production, can produce 100 and 50 pairs of skis per month, respectively. The exhibit gives the slopes of the production possibilities curves for each plant. The opportunity cost of an additional snowboard at each plant equals the absolute values of these slopes (that is, the number of pairs of skis that must be given up per snowboard).

The exhibit gives the slopes of the production possibilities curves for each of the firm’s three plants. The opportunity cost of an additional snowboard at each plant equals the absolute values of these slopes. More generally, the absolute value of the slope of any production possibilities curve at any point gives the opportunity cost of an additional unit of the good on the horizontal axis, measured in terms of the number of units of the good on the vertical axis that must be forgone.

The greater the absolute value of the slope of the production possibilities curve, the greater the opportunity cost will be. The plant for which the opportunity cost of an additional snowboard is greatest is the plant with the steepest production possibilities curve; the plant for which the opportunity cost is lowest is the plant with the flattest production possibilities curve. The plant with the lowest opportunity cost of producing snowboards is Plant 3; its slope of −0.5 means that Ms. Ryder must give up half a pair of skis in that plant to produce an additional snowboard. In Plant 2, she must give up one pair of skis to gain one more snowboard. We have already seen that an additional snowboard requires giving up two pairs of skis in Plant 1.

Comparative Advantage and the Production Possibilities Curve

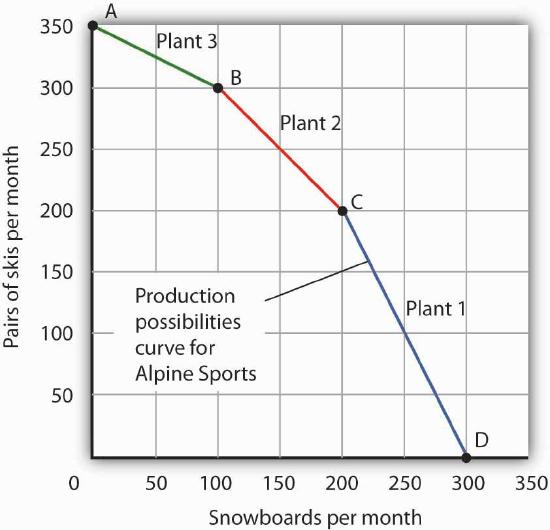

To construct a combined production possibilities curve for all three plants, we can begin by asking how many pairs of skis Alpine Sports could produce if it were producing only skis. To find this quantity, we add up the values at the vertical intercepts of each of the production possibilities curves in Figure 2.4. These intercepts tell us the maximum number of pairs of skis each plant can produce. Plant 1 can produce 200 pairs of skis per month, Plant 2 can produce 100 pairs of skis at per month, and Plant 3 can produce 50 pairs. Alpine Sports can thus produce 350 pairs of skis per month if it devotes its resources exclusively to ski production. In that case, it produces no snowboards.

Now suppose the firm decides to produce 100 snowboards. That will require shifting one of its plants out of ski production. Which one will it choose to shift? The sensible thing for it to do is to choose the plant in which snowboards have the lowest opportunity cost—Plant 3. It has an advantage not because it can produce more snowboards than the other plants (all the plants in this example are capable of producing up to 100 snowboards per month) but because it is the least productive plant for making skis. Producing a snowboard in Plant 3 requires giving up just half a pair of skis.

Economists say that an economy has a comparative advantage in producing a good or service if the opportunity cost of producing that good or service is lower for that economy than for any other. Plant 3 has a comparative advantage in snowboard production because it is the plant for which the opportunity cost of additional snowboards is lowest. To put this in terms of the production possibilities curve, Plant 3 has a comparative advantage in snowboard production (the good on the horizontal axis) because its production possibilities curve is the flattest of the three curves.

Plant 3’s comparative advantage in snowboard production makes a crucial point about the nature of comparative advantage. It need not imply that a particular plant is especially good at an activity. In our example, all three plants are equally good at snowboard production. Plant 3, though, is the least efficient of the three in ski production. Alpine thus gives up fewer skis when it produces snowboards in Plant 3. Comparative advantage thus can stem from a lack of efficiency in the production of an alternative good rather than a special proficiency in the production of the first good.

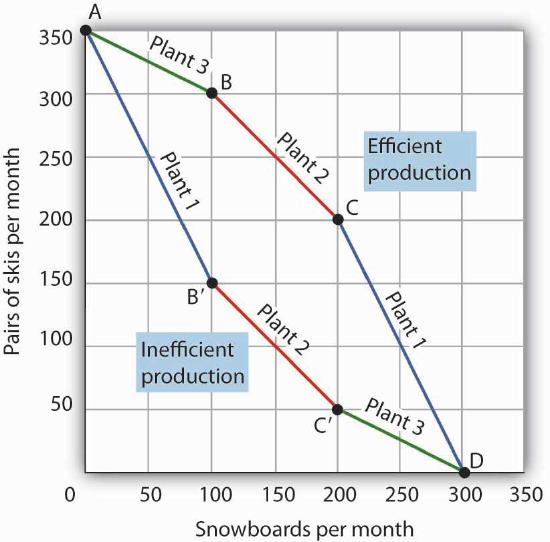

The combined production possibilities curve for the firm’s three plants is shown in Figure 2.5. We begin at point A, with all three plants producing only skis. Production totals 350 pairs of skis per month and zero snowboards. If the firm were to produce 100 snowboards at Plant 3, ski production would fall by 50 pairs per month (recall that the opportunity cost per snowboard at Plant 3 is half a pair of skis). That would bring ski production to 300 pairs, at point B. If Alpine Sports were to produce still more snowboards in a single month, it would shift production to Plant 2, the facility with the next-lowest opportunity cost. Producing 100 snowboards at Plant 2 would leave Alpine Sports producing 200 snowboards and 200 pairs of skis per month, at point C. If the firm were to switch entirely to snowboard production, Plant 1 would be the last to switch because the cost of each snowboard there is 2 pairs of skis. With all three plants producing only snowboards, the firm is at point D on the combined production possibilities curve, producing 300 snowboards per month and no skis.

Notice that this production possibilities curve, which is made up of linear segments from each assembly plant, has a bowed-out shape; the absolute value of its slope increases as Alpine Sports produces more and more snowboards. This is a result of transferring resources from the production of one good to another according to comparative advantage. We shall examine the significance of the bowed-out shape of the curve in the next section.

The Law of Increasing Opportunity Cost

We see in Figure 2.5 that, beginning at point A and producing only skis, Alpine Sports experiences higher and higher opportunity costs as it produces more snowboards. The fact that the opportunity cost of additional snowboards increases as the firm produces more of them is a reflection of an important economic law. The law of increasing opportunity cost holds that as an economy moves along its production possibilities curve in the direction of producing more of a particular good, the opportunity cost of additional units of that good will increase.

We have seen the law of increasing opportunity cost at work traveling from point A toward point D on the production possibilities curve in Figure 2.5. The opportunity cost of each of the first 100 snowboards equals half a pair of skis; each of the next 100 snowboards has an opportunity cost of 1 pair of skis, and each of the last 100 snowboards has an opportunity cost of 2 pairs of skis. The law also applies as the firm shifts from snowboards to skis. Suppose it begins at point D, producing 300 snowboards per month and no skis. It can shift to ski production at a relatively low cost at first. The opportunity cost of the first 200 pairs of skis is just 100 snowboards at Plant 1, a movement from point D to point C, or 0.5 snowboards per pair of skis. We would say that Plant 1 has a comparative advantage in ski production. The next 100 pairs of skis would be produced at Plant 2, where snowboard production would fall by 100 snowboards per month. The opportunity cost of skis at Plant 2 is 1 snowboard per pair of skis. Plant 3 would be the last plant converted to ski production. There, 50 pairs of skis could be produced per month at a cost of 100 snowboards, or an opportunity cost of 2 snowboards per pair of skis.

The bowed-out production possibilities curve for Alpine Sports illustrates the law of increasing opportunity cost. Scarcity implies that a production possibilities curve is downward sloping; the law of increasing opportunity cost implies that it will be bowed out, or concave, in shape.

The bowed-out curve of Figure 2.5 becomes smoother as we include more production facilities. Suppose Alpine Sports expands to 10 plants, each with a linear production possibilities curve. Panel (a) of Figure 2.6 shows the combined curve for the expanded firm, constructed as we did in Figure 2.5. This production possibilities curve includes 10 linear segments and is almost a smooth curve. As we include more and more production units, the curve will become smoother and smoother. In an actual economy, with a tremendous number of firms and workers, it is easy to see that the production possibilities curve will be smooth. We will generally draw production possibilities curves for the economy as smooth, bowed-out curves, like the one in Panel (b). This production possibilities curve shows an economy that produces only skis and snowboards. Notice the curve still has a bowed-out shape; it still has a negative slope. Notice also that this curve has no numbers. Economists often use models such as the production possibilities model with graphs that show the general shapes of curves but that do not include specific numbers.

Movements Along the Production Possibilities Curve

We can use the production possibilities model to examine choices in the production of goods and services. In applying the model, we assume that the economy can produce two goods, and we assume that technology and the factors of production available to the economy remain unchanged. In this section, we shall assume that the economy operates on its production possibilities curve so that an increase in the production of one good in the model implies a reduction in the production of the other.

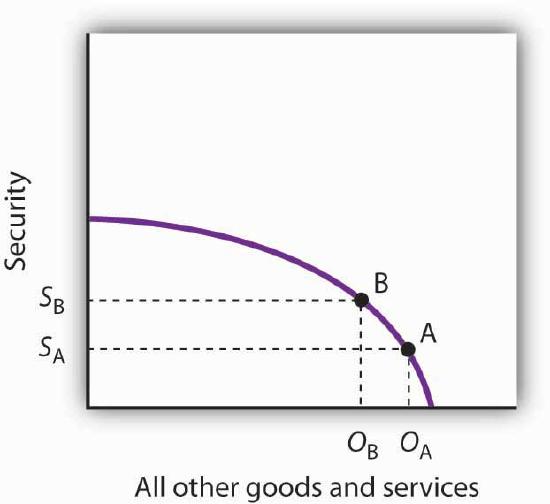

We shall consider two goods and services: national security and a category we shall call “all other goods and services.” This second category includes the entire range of goods and services the economy can produce, aside from national defense and security. Clearly, the transfer of resources to the effort to enhance national security reduces the quantity of other goods and services that can be produced. In the wake of the 9/11 attacks in 2001, nations throughout the world increased their spending for national security. This spending took a variety of forms. One, of course, was increased defense spending. Local and state governments also increased spending in an effort to prevent terrorist attacks. Airports around the world hired additional agents to inspect luggage and passengers.

The increase in resources devoted to security meant fewer “other goods and services” could be produced. In terms of the production possibilities curve in Figure 2.7, the choice to produce more security and less of other goods and services means a movement from A to B. Of course, an economy cannot really produce security; it can only attempt to provide it. The attempt to provide it requires resources; it is in that sense that we shall speak of the economy as “producing” security.

At point A, the economy was producing S A units of security on the vertical axis—defense services and various forms of police protection—and O A units of other goods and services on the horizontal axis. The decision to devote more resources to security and less to other goods and services represents the choice we discussed in the chapter introduction. In this case we have categories of goods rather than specific goods. Thus, the economy chose to increase spending on security in the effort to defeat terrorism. Since we have assumed that the economy has a fixed quantity of available resources, the increased use of resources for security and national defense necessarily reduces the number of resources available for the production of other goods and services.

The law of increasing opportunity cost tells us that, as the economy moves along the production possibilities curve in the direction of more of one good, its opportunity cost will increase. We may conclude that, as the economy moved along this curve in the direction of greater production of security, the opportunity cost of the additional security began to increase. That is because the resources transferred from the production of other goods and services to the production of security had a greater and greater comparative advantage in producing things other than security.

The production possibilities model does not tell us where on the curve a particular economy will operate. Instead, it lays out the possibilities facing the economy. Many countries, for example, chose to move along their respective production possibilities curves to produce more security and national defense and less of all other goods in the wake of 9/11. We will see in the chapter on demand and supply how choices about what to produce are made in the marketplace.

Producing on Versus Producing Inside the Production Possibilities Curve

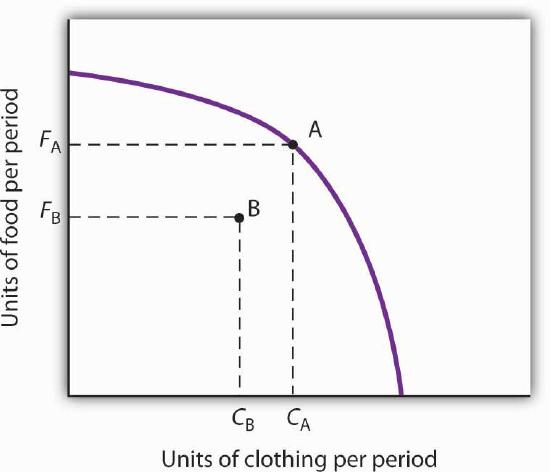

An economy that is operating inside its production possibilities curve could, by moving onto it, produce more of all the goods and services that people value, such as food, housing, education, medical care, and music. Increasing the availability of these goods would improve the standard of living. Economists conclude that it is better to be on the production possibilities curve than inside it.

Two things could leave an economy operating at a point inside its production possibilities curve. First, the economy might fail to use fully the resources available to it. Second, it might not allocate resources on the basis of comparative advantage. In either case, production within the production possibilities curve implies the economy could improve its performance.

Idle Factors of Production

Suppose an economy fails to put all its factors of production to work. Some workers are without jobs, some buildings are without occupants, some fields are without crops. Because an economy’s production possibilities curve assumes the full use of the factors of production available to it, the failure to use some factors results in a level of production that lies inside the production possibilities curve.

If all the factors of production that are available for use under current market conditions are being utilized, the economy has achieved full employment . An economy cannot operate on its production possibilities curve unless it has full employment.

Figure 2.8 shows an economy that can produce food and clothing. If it chooses to produce at point A, for example, it can produce F A units of food and C A units of clothing. Now suppose that a large fraction of the economy’s workers lose their jobs, so the economy no longer makes full use of one factor of production: labor. In this example, production moves to point B, where the economy produces less food ( F B ) and less clothing ( C B ) than at point A. We often think of the loss of jobs in terms of the workers; they have lost a chance to work and to earn income. But the production possibilities model points to another loss: goods and services the economy could have produced that are not being produced.

Inefficient Production

Now suppose Alpine Sports is fully employing its factors of production. Could it still operate inside its production possibilities curve? Could an economy that is using all its factors of production still produce less than it could? The answer is “Yes,” and the key lies in comparative advantage. An economy achieves a point on its production possibilities curve only if it allocates its factors of production on the basis of comparative advantage. If it fails to do that, it will operate inside the curve.

Suppose that, as before, Alpine Sports has been producing only skis. With all three of its plants producing skis, it can produce 350 pairs of skis per month (and no snowboards). The firm then starts producing snowboards. This time, however, imagine that Alpine Sports switches plants from skis to snowboards in numerical order: Plant 1 first, Plant 2 second, and then Plant 3. Figure 2.9 illustrates the result. Instead of the bowed-out production possibilities curve ABCD, we get a bowed-in curve, AB′C′D. Suppose that Alpine Sports is producing 100 snowboards and 150 pairs of skis at point B′. Had the firm based its production choices on comparative advantage, it would have switched Plant 3 to snowboards and then Plant 2, so it could have operated at a point such as C. It would be producing more snowboards and more pairs of skis—and using the same quantities of factors of production it was using at B′. Had the firm based its production choices on comparative advantage, it would have switched Plant 3 to snowboards and then Plant 2, so it would have operated at point C. It would be producing more snowboards and more pairs of skis—and using the same quantities of factors of production it was using at B′. When an economy is operating on its production possibilities curve, we say that it is engaging in efficient production . If it is using the same quantities of factors of production but is operating inside its production possibilities curve, it is engaging in inefficient production . Inefficient production implies that the economy could be producing more goods without using any additional labor, capital, or natural resources.

Points on the production possibilities curve thus satisfy two conditions: the economy is making full use of its factors of production, and it is making efficient use of its factors of production. If there are idle or inefficiently allocated factors of production, the economy will operate inside the production possibilities curve. Thus, the production possibilities curve not only shows what can be produced; it provides insight into how goods and services should be produced. It suggests that to obtain efficiency in production, factors of production should be allocated on the basis of comparative advantage. Further, the economy must make full use of its factors of production if it is to produce the goods and services it is capable of producing.

Specialization

The production possibilities model suggests that specialization will occur. Specialization implies that an economy is producing the goods and services in which it has a comparative advantage. If Alpine Sports selects point C in Figure 2.9, for example, it will assign Plant 1 exclusively to ski production and Plants 2 and 3 exclusively to snowboard production.

Such specialization is typical in an economic system. Workers, for example, specialize in particular fields in which they have a comparative advantage. People work and use the income they earn to buy—perhaps import—goods and services from people who have a comparative advantage in doing other things. The result is a far greater quantity of goods and services than would be available without this specialization.

Think about what life would be like without specialization. Imagine that you are suddenly completely cut off from the rest of the economy. You must produce everything you consume; you obtain nothing from anyone else. Would you be able to consume what you consume now? Clearly not. It is hard to imagine that most of us could even survive in such a setting. The gains we achieve through specialization are enormous.

Nations specialize as well. Much of the land in the United States has a comparative advantage in agricultural production and is devoted to that activity. Hong Kong, with its huge population and tiny endowment of land, allocates virtually none of its land to agricultural use; that option would be too costly. Its land is devoted largely to nonagricultural use.

Key Takeaways

- A production possibilities curve shows the combinations of two goods an economy is capable of producing.

- The downward slope of the production possibilities curve is an implication of scarcity.

- The bowed-out shape of the production possibilities curve results from allocating resources based on comparative advantage. Such an allocation implies that the law of increasing opportunity cost will hold.

- An economy that fails to make full and efficient use of its factors of production will operate inside its production possibilities curve.

- Specialization means that an economy is producing the goods and services in which it has a comparative advantage.

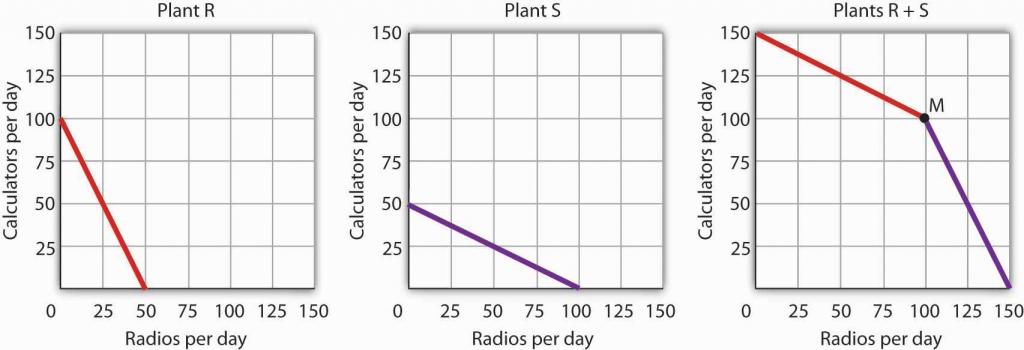

Suppose a manufacturing firm is equipped to produce radios or calculators. It has two plants, Plant R and Plant S, at which it can produce these goods. Given the labor and the capital available at both plants, it can produce the combinations of the two goods at the two plants shown.

Put calculators on the vertical axis and radios on the horizontal axis. Draw the production possibilities curve for Plant R. On a separate graph, draw the production possibilities curve for Plant S. Which plant has a comparative advantage in calculators? In radios? Now draw the combined curves for the two plants. Suppose the firm decides to produce 100 radios. Where will it produce them? How many calculators will it be able to produce? Where will it produce the calculators?

Case in Point: The Cost of the Great Depression

Figure 2.10

Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

The U.S. economy looked very healthy in the beginning of 1929. It had enjoyed seven years of dramatic growth and unprecedented prosperity. Its resources were fully employed; it was operating quite close to its production possibilities curve.

In the summer of 1929, however, things started going wrong. Production and employment fell. They continued to fall for several years. By 1933, more than 25% of the nation’s workers had lost their jobs. Production had plummeted by almost 30%. The economy had moved well within its production possibilities curve.

Output began to grow after 1933, but the economy continued to have vast numbers of idle workers, idle factories, and idle farms. These resources were not put back to work fully until 1942, after the U.S. entry into World War II demanded mobilization of the economy’s factors of production.

Between 1929 and 1942, the economy produced 25% fewer goods and services than it would have if its resources had been fully employed. That was a loss, measured in today’s dollars, of well over $3 trillion. In material terms, the forgone output represented a greater cost than the United States would ultimately spend in World War II. The Great Depression was a costly experience indeed.

Answer to Try It! Problem

The production possibilities curves for the two plants are shown, along with the combined curve for both plants. Plant R has a comparative advantage in producing calculators. Plant S has a comparative advantage in producing radios, so, if the firm goes from producing 150 calculators and no radios to producing 100 radios, it will produce them at Plant S. In the production possibilities curve for both plants, the firm would be at M, producing 100 calculators at Plant R.

Figure 2.11

2.2 The Production Possibilities Frontier and Social Choices

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Interpret production possibilities frontier graphs

- Contrast a budget constraint and a production possibilities frontier

- Explain the relationship between a production possibilities frontier and the law of diminishing returns

- Contrast productive efficiency and allocative efficiency

- Define comparative advantage

Just as individuals cannot have everything they want and must instead make choices, society as a whole cannot have everything it might want, either. This section of the chapter will explain the constraints society faces, using a model called the production possibilities frontier (PPF) . There are more similarities than differences between individual choice and social choice. As you read this section, focus on the similarities.

Because society has limited resources (e.g., labor, land, capital, raw materials) at any point in time, there is a limit to the quantities of goods and services it can produce. Suppose a society desires two products, healthcare and education. The production possibilities frontier in Figure 2.3 illustrates this situation.

Figure 2.3 shows healthcare on the vertical axis and education on the horizontal axis. If the society were to allocate all of its resources to healthcare, it could produce at point A. However, it would not have any resources to produce education. If it were to allocate all of its resources to education, it could produce at point F. Alternatively, the society could choose to produce any combination of healthcare and education on the production possibilities frontier. In effect, the production possibilities frontier plays the same role for society as the budget constraint plays for Alphonso. Society can choose any combination of the two goods on or inside the PPF. However, it does not have enough resources to produce outside the PPF.

Most importantly, the production possibilities frontier clearly shows the tradeoff between healthcare and education. Suppose society has chosen to operate at point B, and it is considering producing more education. Because the PPF is downward sloping from left to right, the only way society can obtain more education is by giving up some healthcare. That is the tradeoff society faces. Suppose it considers moving from point B to point C. What would the opportunity cost be for the additional education? The opportunity cost would be the healthcare society has to forgo. Just as with Alphonso’s budget constraint, the slope of the production possibilities frontier shows the opportunity cost. By now you might be saying, “Hey, this PPF is sounding like the budget constraint.” If so, read the following Clear It Up feature.

Clear It Up

What’s the difference between a budget constraint and a ppf.

There are two major differences between a budget constraint and a production possibilities frontier. The first is the fact that the budget constraint is a straight line. This is because its slope is given by the relative prices of the two goods, which from the point of view of an individual consumer, are fixed, so the slope doesn't change. In contrast, the PPF has a curved shape because of the law of the diminishing returns. Thus, the slope is different at various points on the PPF. The second major difference is the absence of specific numbers on the axes of the PPF. There are no specific numbers because we do not know the exact amount of resources this imaginary economy has, nor do we know how many resources it takes to produce healthcare and how many resources it takes to produce education. If this were a real world example, that data would be available.

Whether or not we have specific numbers, conceptually we can measure the opportunity cost of additional education as society moves from point B to point C on the PPF. We measure the additional education by the horizontal distance between B and C. The foregone healthcare is given by the vertical distance between B and C. The slope of the PPF between B and C is (approximately) the vertical distance (the “rise”) over the horizontal distance (the “run”). This is the opportunity cost of the additional education.

The PPF and the Law of Increasing Opportunity Cost

The budget constraints that we presented earlier in this chapter, showing individual choices about what quantities of goods to consume, were all straight lines. The reason for these straight lines was that the relative prices of the two goods in the consumption budget constraint determined the slope of the budget constraint. However, we drew the production possibilities frontier for healthcare and education as a curved line. Why does the PPF have a different shape?

To understand why the PPF is curved, start by considering point A at the top left-hand side of the PPF. At point A, all available resources are devoted to healthcare and none are left for education. This situation would be extreme and even ridiculous. For example, children are seeing a doctor every day, whether they are sick or not, but not attending school. People are having cosmetic surgery on every part of their bodies, but no high school or college education exists. Now imagine that some of these resources are diverted from healthcare to education, so that the economy is at point B instead of point A. Diverting some resources away from A to B causes relatively little reduction in health because the last few marginal dollars going into healthcare services are not producing much additional gain in health. However, putting those marginal dollars into education, which is completely without resources at point A, can produce relatively large gains. For this reason, the shape of the PPF from A to B is relatively flat, representing a relatively small drop-off in health and a relatively large gain in education.

Now consider the other end, at the lower right, of the production possibilities frontier. Imagine that society starts at choice D, which is devoting nearly all resources to education and very few to healthcare, and moves to point F, which is devoting all spending to education and none to healthcare. For the sake of concreteness, you can imagine that in the movement from D to F, the last few doctors must become high school science teachers, the last few nurses must become school librarians rather than dispensers of vaccinations, and the last few emergency rooms are turned into kindergartens. The gains to education from adding these last few resources to education are very small. However, the opportunity cost lost to health will be fairly large, and thus the slope of the PPF between D and F is steep, showing a large drop in health for only a small gain in education.

The lesson is not that society is likely to make an extreme choice like devoting no resources to education at point A or no resources to health at point F. Instead, the lesson is that the gains from committing additional marginal resources to education depend on how much is already being spent. If on the one hand, very few resources are currently committed to education, then an increase in resources used for education can bring relatively large gains. On the other hand, if a large number of resources are already committed to education, then committing additional resources will bring relatively smaller gains.

This pattern is common enough that economists have given it a name: the law of increasing opportunity cost , which holds that as production of a good or service increases, the marginal opportunity cost of producing it increases as well. This happens because some resources are better suited for producing certain goods and services instead of others. When government spends a certain amount more on reducing crime, for example, the original increase in opportunity cost of reducing crime could be relatively small. However, additional increases typically cause relatively larger increases in the opportunity cost of reducing crime, and paying for enough police and security to reduce crime to nothing at all would be a tremendously high opportunity cost.

The curvature of the production possibilities frontier shows that as we add more resources to education, moving from left to right along the horizontal axis, the original increase in opportunity cost is fairly small, but gradually increases. Thus, the slope of the PPF is relatively flat near the vertical-axis intercept. Conversely, as we add more resources to healthcare, moving from bottom to top on the vertical axis, the original declines in opportunity cost are fairly large, but again gradually diminish. Thus, the slope of the PPF is relatively steep near the horizontal-axis intercept. In this way, the law of increasing opportunity cost produces the outward-bending shape of the production possibilities frontier.

Productive Efficiency and Allocative Efficiency

The study of economics does not presume to tell a society what choice it should make along its production possibilities frontier. In a market-oriented economy with a democratic government, the choice will involve a mixture of decisions by individuals, firms, and government. However, economics can point out that some choices are unambiguously better than others. This observation is based on the concept of efficiency. In everyday usage, efficiency refers to lack of waste. An inefficient machine operates at high cost , while an efficient machine operates at lower cost, because it is not wasting energy or materials. An inefficient organization operates with long delays and high costs, while an efficient organization meets schedules, is focused, and performs within budget.

The production possibilities frontier can illustrate two kinds of efficiency: productive efficiency and allocative efficiency. Figure 2.4 illustrates these ideas using a production possibilities frontier between healthcare and education.

Productive efficiency means that, given the available inputs and technology, it is impossible to produce more of one good without decreasing the quantity that is produced of another good. All choices on the PPF in Figure 2.4 , including A, B, C, D, and F, display productive efficiency. As a firm moves from any one of these choices to any other, either healthcare increases and education decreases or vice versa. However, any choice inside the production possibilities frontier is productively inefficient and wasteful because it is possible to produce more of one good, the other good, or some combination of both goods.

For example, point R is productively inefficient because it is possible at choice C to have more of both goods: education on the horizontal axis is higher at point C than point R (E 2 is greater than E 1 ), and healthcare on the vertical axis is also higher at point C than point R (H 2 is great than H 1 ).

We can show the particular mix of goods and services produced—that is, the specific combination of selected healthcare and education along the production possibilities frontier—as a ray (line) from the origin to a specific point on the PPF. Output mixes that had more healthcare (and less education) would have a steeper ray, while those with more education (and less healthcare) would have a flatter ray.

Allocative efficiency means that the particular combination of goods and services on the production possibility curve that a society produces represents the combination that society most desires. How to determine what a society desires can be a controversial question, and is usually a discussion in political science, sociology, and philosophy classes as well as in economics. At its most basic, allocative efficiency means producers supply the quantity of each product that consumers demand. Only one of the productively efficient choices will be the allocatively efficient choice for society as a whole.

Why Society Must Choose

In Welcome to Economics! we learned that every society faces the problem of scarcity, where limited resources conflict with unlimited needs and wants. The production possibilities curve illustrates the choices involved in this dilemma.

Every economy faces two situations in which it may be able to expand consumption of all goods. In the first case, a society may discover that it has been using its resources inefficiently, in which case by improving efficiency and producing on the production possibilities frontier, it can have more of all goods (or at least more of some and less of none). In the second case, as resources grow over a period of years (e.g., more labor and more capital), the economy grows. As it does, the production possibilities frontier for a society will tend to shift outward and society will be able to afford more of all goods. In addition, over time, improvements in technology can increase the level of production with given resources, and hence push out the PPF.

However, improvements in productive efficiency take time to discover and implement, and economic growth happens only gradually. Thus, a society must choose between tradeoffs in the present. For government, this process often involves trying to identify where additional spending could do the most good and where reductions in spending would do the least harm. At the individual and firm level, the market economy coordinates a process in which firms seek to produce goods and services in the quantity, quality, and price that people want. However, for both the government and the market economy in the short term, increases in production of one good typically mean offsetting decreases somewhere else in the economy.

The PPF and Comparative Advantage

While every society must choose how much of each good or service it should produce, it does not need to produce every single good it consumes. Often how much of a good a country decides to produce depends on how expensive it is to produce it versus buying it from a different country. As we saw earlier, the curvature of a country’s PPF gives us information about the tradeoff between devoting resources to producing one good versus another. In particular, its slope gives the opportunity cost of producing one more unit of the good in the x-axis in terms of the other good (in the y-axis). Countries tend to have different opportunity costs of producing a specific good, either because of different climates, geography, technology, or skills.

Suppose two countries, the US and Brazil, need to decide how much they will produce of two crops: sugar cane and wheat. Due to its climatic conditions, Brazil can produce quite a bit of sugar cane per acre but not much wheat. Conversely, the U.S. can produce large amounts of wheat per acre, but not much sugar cane. Clearly, Brazil has a lower opportunity cost of producing sugar cane (in terms of wheat) than the U.S. The reverse is also true: the U.S. has a lower opportunity cost of producing wheat than Brazil. We illustrate this by the PPFs of the two countries in Figure 2.5 .

When a country can produce a good at a lower opportunity cost than another country, we say that this country has a comparative advantage in that good. Comparative advantage is not the same as absolute advantage, which is when a country can produce more of a good. In our example, Brazil has an absolute advantage in sugar cane and the U.S. has an absolute advantage in wheat. One can easily see this with a simple observation of the extreme production points in the PPFs of the two countries. If Brazil devoted all of its resources to producing wheat, it would be producing at point A. If however it had devoted all of its resources to producing sugar cane instead, it would be producing a much larger amount than the U.S., at point B.

The slope of the PPF gives the opportunity cost of producing an additional unit of wheat. While the slope is not constant throughout the PPFs, it is quite apparent that the PPF in Brazil is much steeper than in the U.S., and therefore the opportunity cost of wheat is generally higher in Brazil. In the chapter on International Trade you will learn that countries’ differences in comparative advantage determine which goods they will choose to produce and trade. When countries engage in trade, they specialize in the production of the goods in which they have comparative advantage, and trade part of that production for goods in which they do not have comparative advantage. With trade, manufacturers produce goods where the opportunity cost is lowest, so total production increases, benefiting both trading parties.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Steven A. Greenlaw, David Shapiro, Daniel MacDonald

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Principles of Economics 3e

- Publication date: Dec 14, 2022

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-3e/pages/2-2-the-production-possibilities-frontier-and-social-choices

© Jan 23, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Learn something today

- Economic Development

- Trade Policies

- Nationalism

Practice Test 3 on Production Possibility Curve

Practice Test 3 on Production Possibility Curve, contains questions related to the introduction of microeconomics, opportunity cost, and production possibility curve. You can also download a PDF at the end of this post for self-practice.

Let’s understand this topic. But before that, please subscribe to our newsletter . It’s free of cost.

You can also subscribe to my YouTube Channel . You can also buy my book at Amazon: https://amzn.in/bEGJyKF

Disclosure: Some of the links on the website are ads, meaning at no additional cost to you, I will earn a commission if you click through or make a purchase. Please support me so that I can continue writing great content for you.

1. Vaani is a school teacher and gets Rs 30000 per month as salary, if she leaves the job and starts tution work, she is expected to earn Rs 300000 per year. What would be the opportunity cost of her school job?

Solution. In the given question, we have Vaani’s monthly salary. In order to make a comparison with the tuition work, we either need to get their annual salary from teaching job or we can convert the tuition work pay as monthly.

Let’s see how much Vaani gets annually from school jobs, 30000 x 12 = 3,60,000 (There are 12 months in a year).

Now, we can compare,

Her annual pay from school is more than what she is getting from annual tuition.

So, the opportunity cost of her school job is 3,00,000 / 12 = 25,000 (Why, in the options, they are comparing for school job, which was given monthly)

2. What is the slope of a straight line PPC?

Solution. The slope of PPC is Marginal Opportunity cost, the straight line PPC has constant slope equals 1.

3. Define opportunity cost with the help of an example.

Solution. Opportunity cost is the cost of the next best alternative. For example,

If Dilarmaan has 3 job opportunities:

TCS is offering him 4,00,000

HCL is offering him 5,00,000

City Bank is offering him 6,00,000

So, if he chooses a City Bank job, then his opportunity cost is 5,00,000 from HCL.

4. What is planned economy?

Solution. When the decisions regarding production, consumption, investment, and distribution of goods and services are taken by the government only. No private sector or market forces are involved, this is known as a planned economy.

5. What is microeconomics? Give an example.

- It is that part of the economic theory that deals with individual units of an economy.

- Microeconomics variables are demand, supply, the income of a consumer, etc.

- Microeconomics deals with the central problems of the allocation of resources.

- For example, a firm, a household, etc.

6. What will be the likely impact of large scale outflow of foreign capital on PPC of the economy and why?

Solution. With the large-scale outflow of foreign capital, the PPC of the economy will shift inwards because available resources are reduced.

7. Giving reason, comment on the shape of PPC based on the following schedule:

Marginal Opportunity Cost = Change in Y/ Change in X

MOC = 2 which is constant throughout the PPC, hence we have straight-line PPC.

8. Why is PPC concave? Explain.

Solution. PPC is concave to the origin because, in order to increase the production of 1 commodity, we have to sacrifice the production of another commodity. Assuming, resources and technology are fixed in any given economy.

9. Why does an economic problem arise? Explain.

Solution. An economic problem arises because:

- Human wants are unlimited.

- Resources to satisfy those wants are limited.

- Resources have alternative uses.

10. Mention central problems of an economy. Why do central problems arise in an economy?

Solution: Central problems are faced by every economy. It includes:

- What to produce?

- How to produce?

- For whom to produce?

Again, resources are limited, and wants are unlimited. Every economy faces a central problem.

11. What causes rotation of PPC?

Solution: PPC means production possibility curve and it is a combination of two commodities that an economy can produce given the resources and technique of production.

A PPC rotates either when the resources increase in the favour of 1 commodity or technology improvements in the favour of 1 commodity.

Download PDF:

Take a look at some other practice tests for class XI, Economics:

- https://learnwithanjali.com/practice-test-on-class-xi-economics/practice-test-1/

- https://learnwithanjali.com/practice-test-on-class-xi-economics/important-questions-introduction-to-consumer-behavior/

Comments are closed.

Learn with Anjali started because there wasn't an easy-to-consume resource to help students with their studies. Anjali is on single-minded mission to make you successful!

If you would like to suggest topics, leave feedback or share your story, please leave a message.

Copyright 2024 Learn With Anjali. All rights reserved. Terms & Privacy Policy

Commerce Aspirant » Economics Class 11 » Production Possibility Curve in Economics – Microeconomics Class 11 Notes

Production Possibility Curve in Economics – Microeconomics Class 11 Notes

Production possibility Curve class 11 notes are presented in an inclusive manner so that students can engage with them properly and make proper answers for every type of question. All the relevant concepts are given below you can click on the relevant point to get detailed explanation.

- What is Production possibility Curve

Operation of PPC

- Assumptions of Production possibility Curve

- Operation of the economy on PPC

- Marginal Rate of Transformation

- Characteristics of production possibility Curve

Production Possibility Curve

Due to scarcity of resources, society cannot satisfy all its wants. In an economy, even if all the resources are used in the best possible manner, the capabilities of the economy are restricted due to the scarcity of resources. Thus, society has to decide what to produce out of an almost infinite range of possibilities. This is where the concept of the Production Possibility Curve (PPC) comes into the picture.

What is Production Possibility Curve (PPC)?

Production Possibility Curve (PPC) is the graphical representation of the possible combinations of two goods that can be produced with given resources and level of technology.

Since the choice is to be made between infinite possibilities, economists assume that there are only two goods being produced. The PPC is the locus of various possible combinations of two goods that can be produced with given resources and technology.

The Production Possibility Curve is also known as the Production Possibility Frontier, Production Possibility Boundary, Transformation Curve, Transformation Frontier or Transformation Boundary.

- Change in PPC: When the useful limit (assets or innovation) for both goods changes, PPC will move.

- PPC rotation: When there is a change in the useful limit (assets or innovation) in just one descent, PPF will rotate.

Class 11 microeconomics chapter 1 notes discuss the change in PPC as follows;

When both products undergo innovation or a change in assets, the PPC can shift either to the right or the left.

- PPC’s Rightward Shift: when I get there. If “Development of Resources” or “Headway or Upgradation of Technology” applies to both products, PPF will shift to the right side.

- PPC’s Leftward Shift: When there is a decline in assets for both products and an innovative debasement, PPF will shift to the left.

Rotation of PPC

Production possibility Curve class 11 traces the rotation of PPF as follows;

It occurs when a change in a single good’s useful limit (assets or innovation) occurs. The item on the X-axis or the Y-axis can undergo rotation.

The X-axis rotation: PPF will pivot to one side whenever an innovative improvement or asset increase is needed to make the product on the X-axis. In any case, the PPF will move to the side if innovative corruption occurs or assets used for creation decrease.

On the Y-axis, rotate: An imaginative improvement or addition in resources for the making of an item on the Y-axis will turn the PPF to the right.

In any case, the PPF will shift to the left side in the event of innovation corruption or a decrease in manufacturing assets.

Assumptions for Production Possibility Curve (PPC)

The concept of the Production Possibility Curve is based on the following assumptions –

- The amount of resources in an economy is fixed. Although, these resources can be transferred from one use to another.

- Using the given resources only 2 goods can be produced.

- These resources are fully and efficiently utilized.

- Resources are not equally efficient in the production of both goods. Therefore, when resources are transferred from one product to another, their productivity or efficiency in production decreases.

- The level of technology is constant.

Let us consider an economy where two goods, good X and good Y are produced is produced. The production Possibility Curve is given below for such a situation.

With the given resources, many combinations of the two goods can be produced in the economy. If X A amount of Good X, it will be possible to produce only Y A amount of Good Y. Similarly for X B amount of Good X, only Y B amount of Good Y can be produced.

This means that more of one good can be produced by sacrificing the other. To produce one more unit of Good X, less of Good Y can be produced. When all these points of different combinations of production of the two goods are joined, they form a Production Possibility Curve.

Operation of the Economy on the Production possibility Curve

The PPC shows the maximum available possibilities which an economy can produce. The point on the PPC where the economy operates depends on how well the resources are utilised. If the resources are fully utilised the economy may operate at any point on the PPC according to the amount of each good produced. This is shown by points A and B in the diagram given above. If the resources are not utilised fully and efficiently, the economy will operate inside the PPC. This is shown by point C in the diagram. Both of these situations are attainable combinations . On the other hand, the economy cannot operate at any point outside the PPC as, with the given amount of resources, it is impossible for the economy to produce any combination more than the given possible combinations. This is shown by point D in the diagram given above. Such situations are known as unattainable combinations .

Marginal Rate of Transformation (MRT)

Marginal Rate of Transformation (MRT) is the ratio of the number of units of a commodity sacrificed to gain an additional unit of another commodity.

MRT = ΔUnits Sacrificed/Δ Units Gained

Consider the given economy, where only guns and butter are produced,

In the given example, 20 units of guns and 1 unit of butter can be produced by utilizing the resources fully and efficiently. If the economy decides to produce 2 units of butter, then it would have to cut down on the production of guns by 2 units.

Characteristics of Production Possibility Curve (PPC)

- PPC slopes downward – PPC shows all the maximum possible combinations of two goods which can be produced with the available resources and technology. Therefore, more of one good can be produced only by taking resources from away from the production of another good. There exists an inverse relationship between the change in the quantity of one commodity and the change in the quantity of another commodity. Therefore, PPC slopes downward from left to right.

- PPC is concave shaped – PPC is concave shaped because more and more units of one commodity are sacrificed to gain an additional unit of another commodity i.e. Marginal Rate of Transformation (MRT). This is because no resource is equally efficient in the production of all goods.

What is Production possibility Curve class 11 notes can form a strong foundation for the upcoming subject matter. These notes define the working of the production possibility Curve in the best way possible. It helps the students to get comprehensive pointers on finger tips for revision and last-minute understanding.

Multiple choice questions

- Scarcity of resources

- Abundance of resources

- Non availability of resources

- All of the above

- Sloping downwards

- Sloping upwards

- Concave Shaped

- Both A and C

- PPC is concave shaped because more and more units of one commodity are ———- to gain an additional unit of another commodity.

- Marginal Rate of …….. is the ratio of the number of units of a commodity ——- to gain an additional unit of another commodity.

- Transformation, sacrificed

- Economics Class 11 Notes

- Accountancy Class 11 Notes

- Economics Class 11 MCQs

Business Studies Class 11 MCQ

Unit Number 319, Vipul Trade Centre, Sohna Road, Gurgaon, Sector 49, Gurugram, Haryana-122028, India

- +91-9667714335

- [email protected]

Class 11 Notes

Class 11 MCQs

- Business Studies Class 11 MCQs

Class 12 Notes

- Economics Class 12 Notes

- Business Studies Class 12 Notes

- Accountancy Class 12 Notes

Class 12 MCQs

- Economics Class 12 MCQs

- Business Studies Class 12 MCQs

- Accountancy Class 12 MCQs

Subscribe To Our Weekly Newsletter

Get notified about new Content

CBSE NCERT Solutions

NCERT and CBSE Solutions for free

Case Study Questions Class 11 Economics

Students should refer to the following Case Study Questions Class 11 Economics which have been provided below as per the latest syllabus and examination pattern issued by CBSE, NCERT, and KVS. As per the new examination guidelines issued for the current academic year, case study-based questions will be asked in the Grade 11 Economics exams. Students should understand the case studies provided below and then practice these questions and answers provided by our teachers.

Class 11 Economics Case Study Questions

Please click on the links below to access free solved Case Study Questions for Class 11 Economics. We have provided chapter-wise case studies with solved questions. Please carefully understand each case and related questions before attempting the questions. Our teachers have provided answers to all questions so that you can compare your answers.

We have also provided MCQ Question for Class 11 Economics which will be asked in the upcoming exams in Grade 11. As this year many questions will be MCQ-based and there will also be a few case studies in the question papers. Students should go through all chapter-wise Case Study Questions for Class 11 Economics. We have provided many other useful links and study material for Standard 11th Economics for the benefit of students. All content has been provided for free so that the students can take full benefit and get better marks in examinations. Incase any student faces any doubts, please provide your comments in the section below so that our faculty is able to respond to your questions.

Related Posts

Chapter 12 applications of computers in accounting important questions.

Chapter 7 Depreciation Provisions and Reserves Case Study Questions

Relational Databases Class 11 Informatics Practices Important Questions

Telegram Channel

Case-Based MCQs of Production Function Microeconomics class 11 CBSE

- December 8, 2021

- Production Function

Looking for important Case-Based MCQS questions with answers of Production Function chapter of Microeconomics class 11 CBSE, ISC, and other State Board.

Case Based Multiple Choice Questions of Production Function chapter with answers of Microeconomics class 11

Let’s Practice.

Question – 1 (Case – Study)

Farmers in our country are mostly small and marginal. They produce for self-consumption and hardly have any surplus crop to sell in the market.

These farmers produce with the help of their family members. Also due to limited landholding at times, there are more labours working compared with what is actually required, this leads to disguised unemployment.

The use of primitive tools and techniques further reduces the ability of these families to increase production.

1) In the case of disguised unemployment, the marginal product of labour is equal to

a) Zero b) Positive c) negative d) Either a) or c)

Ans – a)

Explanation:- In the case of disguised unemployment, the marginal productivity of labour becomes zero. Thus, he/she does not contribute anything to output.

2) In the case of land, the ‘law of returns to factor’ is applicable in _________ .

a) Short-run b) medium run c) long run d) None of these

3) In the above situation, productivity was low due to __________ .

a) fixity of land b) use of primitive tools and techniques c) excessive use of variable factor d) All of the above

Ans – d)

4) A rational producer should opt to produce in __ stage.

a) increasing returns to scale b) diminishing returns to scale c) constant returns to scale d) None of the above

Ans – b)

5) Which of the following is a variable factor of production in farming?

a) Farming Land b) Labour c) Equipment d) Both b) and c)

Explanation:- Labour and equipment are variable factors as they vary directly with the level of output.

Assertion (A) In the case of disguised employment total physical product becomes constant.

Reason (R) When more people work at a place than required, additional workers do not contribute much to the output.

Alternatives:-

a) Both Assertion (A) and Reason (R) are true and Reasons (R) is the the correct explanation of Assertion (A)

b) Both Assertion (A) and Reason (R) are true, but Reason (R) is not the the correct explanation of Assertion (A)

c) Assertion (A) is true, but Reason (R) is false

d) Assertion (A) is false, but Reason (R) is true.

Question – 2 (Case – Study)

Revenue is an important aspect of a producer’s behaviour. It indicates a firm’s receipts from sales. In other words, it also indicates the demand for a firm’s goods and services. More sales usually indicate more revenue but higher sale depends upon the form of market and elasticity of demand. Firms have better control over price when demand is inelastic.

i) In which form of market, average revenue is inelastic?

a) Perfect competition b) Monopoly c) Monopolistic d) None of these

Incremental revenue is always equal to price under _ market.

a) Perfect competition b) monopoly c) monopolistic d) None of these

2) Average revenue under monopolistic competition is elastic due to

a) lower price b) greater choice c) price control d) All of these

3) When average revenue is elastic, marginal revenue is

a) inelastic b) also elastic c) perfectly elastic d) perfectly inelastic

4) Assertion (A) Total Revenue and profits are equal under the market with a constant price.

Reason (R) When Price becomes constant, additional revenue becomes equal to average revenue.

Alternatives

a) Both Assertion (A) and Reason (R) are true and Reasons (R) is the correct explanation of Assertion (A)

b) Both Assertion (A) and Reason (R) are true, but Reason (R) is not the correct explanation of Assertion (A)

6) __ curve represent the demand curve of a firm as mentioned in the given paragraph.

a) Total revenue b) Average revenue c) Marginal revenue d) None of the above

Anurag Pathak

Anurag Pathak is an academic teacher. He has been teaching Accountancy and Economics for CBSE students for the last 18 years. In his guidance, thousands of students have secured good marks in their board exams and legacy is still going on. You can subscribe his youtube channel and can download the Android & ios app for free lectures.

Related Posts

Assertion reason mcqs of production function microeconomics class 11 cbse.

- December 7, 2021

Important MCQs of Production Function of Microeconomics class 11 CBSE

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Name *

Email *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Post Comment

Trending now

Ad blocker detected.

myCBSEguide

- Entrance Exam

- Competitive Exams

- ICSE & ISC

- Teacher Exams

- UP Board

- Uttarakhand Board

- Bihar Board

- Chhattisgarh Board

- Haryana Board

- Jharkhand Board

- MP Board

- Rajasthan Board

- Courses

- Test Generator

- Homework Help

- News & Updates

- Dashboard

- Mobile App (Android)

- Browse Courses

- New & Updates

- Join Us

- Login

- Register

No products in the cart.

- Homework Help

Case study on production possibility curve …

CBSE, JEE, NEET, CUET

Question Bank, Mock Tests, Exam Papers

NCERT Solutions, Sample Papers, Notes, Videos

Case study on production possibility curve and consumer equilibrium

Posted by Om Chauhan 4 years, 1 month ago

Rekha Walia 5 months, 3 weeks ago

17 Thank You

Divesh Dagar 4 years, 5 months ago

15 Thank You

Related Questions

Posted by Minakshi Jain 2 weeks, 3 days ago

Posted by Rohit Sisodiya 6 days ago

Posted by Palak Chaudhary 4 days ago

Posted by Muskan Choudhary 1 week, 4 days ago

Posted by Parneet Kaur 3 weeks, 4 days ago

Posted by Bishal Ghosh 1 week ago

Posted by Prince Pal 1 week, 3 days ago

Posted by Som Agrawal 1 week, 1 day ago

Posted by Pratima Limbu 1 day, 6 hours ago

Posted by Rupali Verma 1 week, 4 days ago

Trusted by 1 Crore+ Students

Test Generator

Create papers online. It's FREE .

CUET Mock Tests

75,000+ questions to practice only on myCBSEguide app

Download myCBSEguide App

All courses.

- Entrance Exams

- Competative Exams

- Teachers Exams

- Uttrakand Board

- Bihar Board

- Chhattisgarh Board

- Haryana Board

- Jharkhand Board

- Rajasthan Board

Other Websites

- Examin8.com

CBSE Courses

- CBSE Class 12

- CBSE Class 11

- CBSE Class 10

- CBSE Class 09

- CBSE Class 08

- CBSE Class 07

- CBSE Class 06

- CBSE Class 05

- CBSE Class 04

- CBSE Class 03

- CBSE Class 02

- CBSE Class 01

CBSE Sample Papers

- CBSE Test Papers

- CBSE MCQ Tests

- CBSE 10 Year Papers

- CBSE Syllabus

NCERT Solutions

- CBSE Revision Notes

- Submit Your Papers

- Terms of Service

- Privacy Policy

- NCERT Solutions for Class 12

- NCERT Solutions for Class 11

- NCERT Solutions for Class 10

- NCERT Solutions for Class 09

- NCERT Solutions for Class 08

- NCERT Solutions for Class 07

- NCERT Solutions for Class 06

- NCERT Solutions for Class 05

- NCERT Solutions for Class 04

- NCERT Solutions for Class 03

- CBSE Class 12 Sample Papers

- CBSE Class 11 Sample Papers

- CBSE Class 10 Sample Papers

- CBSE Class 09 Sample Papers

- CBSE Results | CBSE Datesheet

Please Wait..

COMMENTS

ECONOMICS CASE STUDIES Production Possibilities. Case Study # 11 - Read the scenario and complete the following given only the information below. You're only 16 years old, but you've always been an entrepreneur. Lately, you've been raking/mowing lawns and washing cars to make some extra cash.

Class 11 Economics Case Study 1. Read the following Case Study carefully and answer the questions on the basis of the same: If our income rises, we generally tend to buy more of the goods. More income would mean more pens, more shirts, more shoes, more cars and so on. But there are exceptions.

Case Study #11-Read the scenario and complete the following given only the information below.You're only 16 years old, but you've always been an entrepreneur. Lately, you've been raking/mowing lawns and washing cars to make some extra cash. Everyone in your neighborhood knows that you're a hard worker so you always have plenty of customers. . Between school and extracurricular ...

The Production Possibilities Frontier (PPF) is a graph that shows all the different combinations of output of two goods that can be produced using available resources and technology. The PPF captures the concepts of scarcity, choice, and tradeoffs. The shape of the PPF depends on whether there are increasing, decreasing, or constant costs.

A production possibility curve measures the maximum output of two goods using a fixed amount of input. The input is any combination of the four factors of production : natural resources (including land). labor. capital goods. and entrepreneurship. The manufacturing of most goods requires a mix of all four. The production possibilities curve ...

Learn for free about math, art, computer programming, economics, physics, chemistry, biology, medicine, finance, history, and more. Khan Academy is a nonprofit with the mission of providing a free, world-class education for anyone, anywhere.

The Production Possibilities Curve (PPC) is a model that captures scarcity and the opportunity costs of choices when faced with the possibility of producing two goods or services. Points on the interior of the PPC are inefficient, points on the PPC are efficient, and points beyond the PPC are unattainable. The opportunity cost of moving from ...

Figure 2.2 A Production Possibilities Curve The table shows the combinations of pairs of skis and snowboards that Plant 1 is capable of producing each month. These are also illustrated with a production possibilities curve. Notice that this curve is linear. To see this relationship more clearly, examine Figure 2.3.

In this way, the law of increasing opportunity cost produces the outward-bending shape of the production possibilities frontier. Productive Efficiency and Allocative Efficiency. The study of economics does not presume to tell a society what choice it should make along its production possibilities frontier.

The production possibilities curve (PPC) is a method used to describe how two commodities are related to each other in terms of the ability to produce both within an economy. It is also called the ...

Solution: PPC means production possibility curve and it is a combination of two commodities that an economy can produce given the resources and technique of production. A PPC rotates either when the resources increase in the favour of 1 commodity or technology improvements in the favour of 1 commodity. Download PDF: