- English Grammar

- Gender In English Grammar

- Neuter Gender

Neuter Gender - Explore Meaning, Definition and 100+ Examples

When learning about gender in English grammar , you should also build your knowledge on neuter gender. While many other languages classify both animate and inanimate objects as belonging to the masculine or feminine gender, it is not the same with the English language . This article will help you with all that you need to know about neuter gender. Furthermore, you can also go through the 100+ examples given.

Table of Contents

What is neuter gender, list of 100+ neuter gender examples, frequently asked questions on neuter gender in english grammar.

Neuter gender refers to the grammatical category of words which are neither masculine nor feminine. Most inanimate objects seem to have no gender. According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, neuter gender is defined as those words “relating to, or constituting the gender that ordinarily includes most words or grammatical forms referring to things classed as neither masculine nor feminine”, and according to the Oxford Learner’s Dictionary, it is defined as “belonging to a class of nouns , pronouns , adjectives or verbs whose gender is not feminine or masculine”. The Cambridge Dictionary defined neuter gender as “being a noun or pronoun of a type that refers to things; not masculine or feminine”.

Check out the table for more than 100 examples of the neuter gender.

What is neuter gender?

Neuter gender refers to a grammatical category of words which are neither masculine nor feminine. Most inanimate objects seem to have no gender.

What is the definition of neuter gender?

According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, neuter gender is defined as those words “relating to, or constituting the gender that ordinarily includes most words or grammatical forms referring to things classed as neither masculine nor feminine”, and according to the Oxford Learner’s Dictionary, it is defined as “belonging to a class of nouns, pronouns, adjectives or verbs whose gender is not feminine or masculine”. The Cambridge Dictionary defined neuter gender as “being a noun or pronoun of a type that refers to things; not masculine or feminine”.

Give 10 examples for the neuter gender.

Given below are 10 examples for the neuter gender for your reference.

- Share Share

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

Neuter is a long-established word for a sex or gender outside of the gender binary . Various dictionaries generally give it these two relevant definitions, among others:

1. A gender neither masculine nor feminine. Genderless . Gender neutral . An androgynous person.

2. Without sexual organs, or with incomplete sexual organs. In biology and zoology, this can mean animals that were artificially spayed, castrated , or otherwise sterilized , as well as animals who were normally born in that condition, such as worker bees. In botany, neuter can mean plants without pistils and stamens. [1] [2] [3]

Although the word "neuter" has existed in English with these meanings for hundreds of years, surveys show that it hasn't been common for contemporary nonbinary people to call themselves neuter. [4] However, neuter was mentioned as one of many valid nonbinary identities in the 2013 text Sexuality and Gender for Mental Health Professionals: A Practical Guide . [5]

The word in English usage dates back to the 14th century neutre , used in the grammatical sense. The English language borrowed this word from Latin neuter meaning "neither one nor the other" ( ne- "not, no" + uter "either (of two)"). This Latin word is likely taken in turn from the old Greek word oudeteros . [6]

Related terms [ edit | edit source ]

- FTN . In some queer communities, this has meant female-to-neuter (or neutrois ) transsexual (or transgender), as a counterpart to more widely-used terms, FTM (female-to-male, meaning a trans man, or someone on the trans-masculine spectrum) and MTF (male-to-female, meaning a trans woman, or someone on the trans-feminine spectrum). [7]

- MTN . Male-to-neuter (or neutrois ) transsexual (or transgender). [7]

Notable neuter people [ edit | edit source ]

See main article: Notable nonbinary people

There are many more notable people who have a gender identity outside of the binary . The following are only some of those notable people who specifically use the word "neuter" for themselves.

- Claude Cahun (1894 - 1954) was a surrealist artist and a resistance worker against the Nazi occupation of France in WWII. In Cahun's autobiography, Disavowals , they explained, “Masculine? Feminine? It depends on the situation. Neuter is the only gender that always suits me.” [8]

- Autistic activist and intersex person Jim Sinclair (1940 - ) has said they are "proudly neuter, both physically and socially." [9] In 1993 Sinclair wrote the essay, "Don't Mourn for Us", articulating an anti-cure perspective on autism. [10] The essay has been thought of as a touchstone for the fledgling autism-rights movement, and has been mentioned in The New York Times [11] and New York Magazine . [12]

Neuter characters in fiction [ edit | edit source ]

See main article: Nonbinary gender in fiction

There are many more nonbinary characters in fiction who have a gender identity outside of the binary . The following are only some of those characters who are specifically called by the word "neuter," either in their canon, or by their creators.

- In the book Surface Detail , the character Yime Nsokyi is "neuter-gendered" and has an intersex body by choice.

- M.C.A. Hogarth's science-fiction series about the Jokka, an alien species that has three sexes, called male, female, and neuter. These stories focus on individuals who do not conform to their society's gender roles; some could be considered transgender, and at least one character could be considered to be trans neuter. However, the author often publicly voices her opposition to transgender rights in real life, saying she "Will never stop fighting this trans thing. Never."; [13] agreeing with anti-transgender author Abigail Shrier's opposition of the informed consent model of pediatric transgender health care; [14] saying she liked Debrah Soh's anti-transgender book; [15] siding with a student who expressed anti-transgender views, in reply to an anti-transgender Twitter account; [16] being a fan of an anti-trans podcaster; [17] asserting the anti-transgender claim that "cisgender is a slur"; [18] and saying that transgender people should never transition, and should instead content themselves with "the flesh God gave" them. [19] This is an example of how authors who write representation of gender-variant characters can't be assumed to support the human rights of gender-variant people in real life and may even actively oppose it.

- The Kyree, in Mercedes Lackey's World of Velgarth fantasy novel series, are an intelligent wolf-like people with three sexes: male, female, and neuter. Since neuter Kyree aren't obliged to take part in raising offspring, they're the ones who tend to go out into the world on adventures.

- The protagonist in Kurt Vonneguts' novel Deadeye Dick, Rudy Waltz, explicitly identifies as "neuter" and reflects upon the word, its connotation and sexuality on several occassions.

Please help expand this section.

See also [ edit | edit source ]

- List of nonbinary identities

References [ edit | edit source ]

- ↑ "Neuter." Merriam-Webster Dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/neuter Archived on 17 July 2023

- ↑ "Neuther." Dictionary.com. https://www.dictionary.com/browse/neuter Archived on 17 July 2023

- ↑ "Neuter." The Free Dictionary. https://www.thefreedictionary.com/neuter Archived on 17 July 2023

- ↑ Gender Census 2019 - the public spreadsheet . 30 March 2019 Archived on 17 July 2023

- ↑ "neuter (adj.)" . Online Etymology Dictionary . Archived from the original on 17 July 2023 . Retrieved 20 October 2020 .

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "LGBTQ terms." Neutrois.com. [1] Archived on 17 July 2023

- ↑ Cahun, C., Malherbe, S. (2008). Disavowals: Or, Cancelled Confessions. United States: MIT Press.

- ↑ Sinclair, Jim (1997). "Self-introduction to the Intersex Society of North America" . Archived from the original on 7 February 2009.

- ↑ Sinclair, Jim (1993). "Don't mourn for us" . Autreat. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023 . Retrieved 2014-08-11 . CS1 maint: discouraged parameter ( link )

- ↑ Harmon, Amy (2004-12-20). "How About Not 'Curing' Us, Some Autistics Are Pleading" . The New York Times . Archived from the original on 17 July 2023 . Retrieved 2007-11-07 . CS1 maint: discouraged parameter ( link )

- ↑ Solomon, Andrew (2008-05-25). "The Autism Rights Movement" . New York Magazine . Archived from the original on 17 July 2023 . Retrieved 2008-06-28 . CS1 maint: discouraged parameter ( link )

- ↑ M.C.A. Hogarth. Tweet. April 5, 2022. https://twitter.com/mcahogarth/status/1511294884514308097 Archive: https://web.archive.org/web/20220820220131/https://twitter.com/mcahogarth/status/1511294884514308097

- ↑ M.C.A. Hogarth. October 25, 2021. Tweet. https://twitter.com/mcahogarth/status/1452699729519947791 Archive: https://web.archive.org/web/20211026003911/https://twitter.com/mcahogarth/status/1452699729519947791

- ↑ M.C.A. Hogarth. Tweet. May 11, 2022. https://twitter.com/mcahogarth/status/1524463492266352643 Archive: https://web.archive.org/web/20220511185719/https://twitter.com/mcahogarth/status/1524463492266352643

- ↑ M.C.A. Hogarth. Tweet. May 17, 2022. https://twitter.com/mcahogarth/status/1526501664747933696 Archive: https://web.archive.org/web/20220517095601/https://twitter.com/mcahogarth/status/1526501664747933696

- ↑ M.C.A. Hogarth. Tweet. July 15, 2022. https://twitter.com/mcahogarth/status/1547926016521162752 Archive: https://web.archive.org/web/20220715124900/https://twitter.com/mcahogarth/status/1547926016521162752

- ↑ M.C.A. Hogarth. Tweet. April 29, 2022. https://twitter.com/mcahogarth/status/1520102220510937088 Archive: https://web.archive.org/web/20220821051705/https://twitter.com/mcahogarth/status/1520102220510937088

- ↑ M.C.A. Hogarth. Tweet. August 23, 2021. https://twitter.com/mcahogarth/status/1429783919889637376 Archive: https://web.archive.org/web/20220818215810/https://twitter.com/mcahogarth/status/1429783919889637376

- Nonbinary identities

- CS1 maint: discouraged parameter

Neuter Genders: What It Is and How To Use It

Do you know what neuter genders are? This article will provide you with all of the information you need on neuter genders, including the definition, usage, example sentences, and more!

Your writing, at its best

Compose bold, clear, mistake-free, writing with Grammarly's AI-powered writing assistant

What are examples of neuter genders?

A neuter gender can be used in many different contexts in the English language. Trying to use a word or literary technique in a sentence is one of the best ways to memorize what it is, but you can also try making flashcards or quizzes that test your knowledge. Try using this term of the day in a sentence today! The following sentences are examples of neuter genders from English Bix that can help get you started incorporating this tool into your everyday use. Try to use the term neuter genders today or notice when someone else is using a neuter gender.

- I can use this box to keep my secret stuff.

- I took a long drought of the drink he had brought me at so high a price, looking at him over the rim of the glass.

- He sat up and looked at her, absently tapping the edge of the piano keys without making a sound.

- Instead of being used for serving food, it seems far more likely that it formed a showpiece, displayed prominently at its owner’s banquets.

- He was silhouetted by the bright sky behind him and yet Pen felt as if she had just seen his face.

- We need to kit the parts for the assembly by Friday so that manufacturing can build the tool.

- As the police approached, the car pulled off and sped away into the distance.

- One can love one’s neighbors in the abstract, or even at a distance, but at close quarters it’s almost impossible.

- It is my wallet.

- Each student must ensure their guest signs the registry.

- At the bottom of the case are the two USB ports, a FireWire connection, and a mic and headphone jack.

- The uniform for the Wolf Cub Scout is the official blue Cub Scout shirt, Wolf neckerchief, and slide.

- What I want is some peace and quiet place.

- Pulling her silk robe more tightly around her, Olivia pads over to her night table to pick up a bottle of body lotion.

- You made a really, really bad move getting in bed with Microhook, and it will cost you in the end.

- I’ve been a long time fan of television, even going so far as to major in it in college.

- A day before the sows are ready to farrow, the farrowing boxes are set up in the rooms.

- Then, with a felt-tipped pen or sharp pencil, mark the lag screw holes that were drilled in the ledger on the wail.

- The end of the book includes a short glossary of terms to help readers with certain concepts such as bel canto, leitmotif, and verismo.

- This chair is really comfortable.

- This road bends as it crosses the bridge.

- The dog took its toy into the house and began tearing it apart on the couch.

- The shark stalked its prey from afar until it was ready to make the attack.

Overall, the term neuter genders refer to sexless objects that have neither a male or female gender in English grammar.

- neuter: meaning, origin, translation | Word Sense

- Neuter Gender Noun with Examples | English Bix

- Neuter Gender | What Is Neuter Gender in Grammar? | Grammar Monster

- Identifying a German Word’s Gender | dummies

Kevin Miller is a growth marketer with an extensive background in Search Engine Optimization, paid acquisition and email marketing. He is also an online editor and writer based out of Los Angeles, CA. He studied at Georgetown University, worked at Google and became infatuated with English Grammar and for years has been diving into the language, demystifying the do's and don'ts for all who share the same passion! He can be found online here.

Recent Posts

Independent Meaning: Here’s What It Means and How To Use It

Angel Number 222 Meaning: Here’s What It Means and How To Use It

Cornerstone Meaning: Here’s What It Means and How To Use It

Solitude Meaning: Here’s What It Means and How To Use It

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Overlooked No More: Claude Cahun, Whose Photographs Explored Gender and Sexuality

Society generally considered women to be women and men to be men in early-20th-century France. Cahun’s work protested gender and sexual norms, and has become increasingly relevant.

Overlooked is a series of obituaries about remarkable people whose deaths, beginning in 1851, went unreported in The Times. This month we’re adding the stories of important L.G.B.T.Q. figures.

By Joseph B. Treaster

In early-20th-century France, when society generally considered women to be women and men to be men, Lucy Schwob decided she would rather be called Claude Cahun.

It was her way of protesting gender and sexual norms. She thrived on ambiguity and she chose a name, Claude, that in French could refer to either a man or a woman. She took the last name from her grandmother Mathilda Cahun.

Cahun (ca-AH) made ambiguity a theme in a lifelong exploration of gender and sexual identity as a writer and photographer. Decades after her death, she has a growing following among art historians, feminists and people in the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer community.

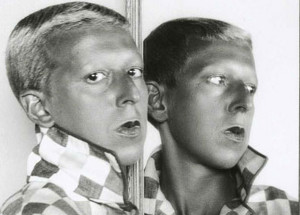

Working in Paris in the racy 1920s and ’30s alongside Surrealist artists and writers, long before the rise of the gender-neutral “they” as a pronoun and the advent of terms like transgender and queer theory, Cahun created stark, sometimes playful, but deliberately equivocal photos of herself.

Here she’s a man. There she’s a woman. Sometimes she’s a little of both. Sometimes her head is shaved. In one photograph, Cahun brings together two silhouette portraits of herself, bald and austere, sizing each other up. “What do you want from me?” her caption reads.

“Masculine? Feminine?” she wrote in her book “Aveux non Avenus,” published in English as “Disavowals.” “It depends on the situation. Neuter is the only gender that always suits me.”

As writer and photographer, Cahun worked at upending convention. “My role,” she wrote in an essay published after her death, “was to embody my own revolt and to accept, at the proper moment, my destiny, whatever it may be.”

Cahun’s writing is complex and often difficult to follow, scholars say. But it provides context for the photographs and the weave of her life.

The photographs are by far her most compelling work. At first, scholars thought of them as self-portraits. But the gathering consensus is that Cahun choreographed and posed for the photos, and that her romantic partner, Marcel Moore, who was born Suzanne Malherbe, often pressed the button. It was a collaboration.

Cahun died on Dec. 8, 1954, at age 60, on the tiny Channel Island of Jersey off the Normandy coast of France. Hardly anyone noticed. “Disavowals,” her most heartfelt book, had not been well received. And she had never exhibited the photographs.

In the 1990s, however, she received a rush of attention as gender issues were gathering steam around the world. “Suddenly,” said Vince Aletti, a New York photography critic and curator, “she seemed incredibly of the moment.”

A French writer, François Leperlier, published a book on Cahun and helped organize the first exhibition of her work, at a museum in Paris. An English edition was published as “Claude Cahun: Masks and Metamorphoses.”

Professors and graduate students in art history and in feminist and gender studies began writing about her. Art museums wanted her work.

Cahun’s photographs have been displayed in group shows in the last two years in nearly a dozen museums in London, Paris, Washington, Melbourne, Warsaw and elsewhere. She is featured in a group exhibition running through early July at the Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco. Another group show opened in Bonn, Germany, in late May, and one opened in Sweden in mid-June.

Tellingly, many middle and high school students have attended the San Francisco exhibition, said Lori Starr, the museum’s director.

“In Cahun you’ve got an artist who turns the camera on themselves to see who else they can become,” said David J. Getsy, a professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago who specializes in gender and sexuality in art. “Isn’t that what we’re all doing now with cellphone photos? This is one reason young people might see themselves in Cahun.”

Paris named a street for Cahun and Moore in 2018. That same year, Christian Dior brought out an androgynous collection inspired by Cahun.

Cahun’s art spoke to David Bowie , who was known for his shifting personas. He arranged a flashy, high-tech, outdoor presentation of her photographs in New York in 2007, telling reporters her work was “really quite mad, in the nicest possible way.”

Lucy Renee Mathilde Schwob was born on Oct. 25, 1894, in Nantes, a provincial capital 200 miles southwest of Paris, to Maurice Schwob, the owner and publisher of the regional newspaper Le Phare de La Loire, and Victorine Mary-Antoinette Courbebaisse.

When she was 4, her mother began to show signs of mental illness and her grandmother took her in.

At 12, Lucy was sent to boarding school in England after French classmates began harassing her with anti-Semitic taunts. Back in Nantes at about 14 or 15, she met Suzanne Malherbe, who was two years older. The encounter, Cahun would write, was like a lightning strike.

Eight years later, Cahun’s father remarried. His new wife was Marie Eugénie Malherbe, Suzanne Malherbe’s mother. That made Cahun and Moore stepsisters, which created the appearance of a conventional relationship.

In Paris, they lived comfortably off family money. Drawing on her studies at the Sorbonne, Cahun wrote for literary magazines and journals, published at least two books and performed in experimental theater.

Moore worked as an illustrator and theatrical designer. Their apartment became a gathering place for writers and artists. They talked about social justice and debated communism as a counterforce to fascism. André Breton, a leader of the Surrealist movement, wrote in a letter to Cahun in the early 1930s that she was “one of the most curious spirits of our time.”

Scholars are convinced that the choice of the name Claude Cahun was an important and symbolic expression of Cahun’s worldview. “It was not just a pen name,” said Jennifer L. Shaw, an art history professor at Sonoma State University in California and the author of a biography of Cahun. And yet Cahun and Moore usually called each other Lucy and Suzanne. Many friends and relatives also addressed them by those names.

In a similar separation between the intimate and the public, scholars say, the photographs were more part of a private conversation than something to present to the world.

“They were in the mode of investigation, who you could be, how you could be, projecting yourself into another skin, another universe,” said Tirza True Latimer, a professor at the California College of the Arts in San Francisco, who first wrote about Cahun in her Ph.D. thesis nearly 20 years ago. “These were two lesbians living within certain constraints. The photographs, the acting out, were a way of being free. It wasn’t really about producing an art object.”

In 1937, with tension rising in prewar Paris, Cahun and Moore decamped for Jersey, where they bought a large granite house overlooking St. Brelade’s Bay.

When the Nazis rolled over France in 1940, they took Jersey and the other Channel Islands. Cahun and Moore fought back — with their typewriter and pens, writing short messages to the Germans under the guise of an unhappy soldier they called “the soldier with no name,” said Louise Downie, the director of curation at the Jersey Heritage Trust, which has the main collection of Cahun’s and Moore’s work.

The messages — written on small bits of paper, sometimes even toilet paper — said that the war was lost, that German troops should look out for themselves. They called Hitler a vampire. Whatever the soldiers’ commanders might say, one note read, “Nobody dies for us.”

They slipped the notes into uniform pockets at the laundry, under windshield wipers and into cigarette packs left on cafe tables, Val Nelson, the senior registrar at the Jersey trust, said.

It was a small-scale effort, with serious consequences. Cahun and Moore had a suicide plan and carried barbiturates. After three years they were caught and sentenced to death. Twice, they tried to kill themselves but underdosed. The war ended and they went free.

Cahun died nine years later and was buried in the churchyard next to their house. Moore took her own life 18 years after that. They are now together under a single gravestone inscribed with two Stars of David and their birth names.

Why they did not put Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore on the tombstone — or use them in their handwritten wills — is a mystery. There are no clues at the Jersey trust.

But whatever their reasoning, Cahun and Moore remain symbols of how people can break free of society’s preconceptions.

“Their lives were a performance around the questioning of identity,” Jonathan Carter, the chief executive of the Jersey trust, said.

Overlooked No More

Since 1851, white men have made up a vast majority of new york times obituaries. now, we’re adding the stories of other remarkable people..

Lizzie Magie: Magie’s creation, The Landlord’s Game, inspired the spinoff we know today: Monopoly. But credit for the idea long went to someone else .

Henrietta Leavitt: The portrait that emerged from her discovery , called Leavitt’s Law, showed that the universe was hundreds of times bigger than astronomers had imagined.

Miriam Solovieff: She led a successful career as a violinist despite coping with a horrific event: witnessing the killing of her mother and sister at the hands of her father at 18.

Beatrix Potter: She created one of the world’s best-known characters for children and fought to have the book published, but she never sought celebrity status .

Cordell Jackson: A pioneering record-label owner and engineer, she played guitar in a raw and unapologetically abrasive way .

Ethel Lindgren: The anthropologist is best remembered for importing reindeer to the Scottish Highlands, centuries after they were hunted to extinction.

paper-free learning

- conjunctions

- determiners

- interjections

- prepositions

- affect vs effect

- its vs it's

- your vs you're

- which vs that

- who vs whom

- who's vs whose

- averse vs adverse

- 250+ more...

- apostrophes

- quotation marks

- lots more...

- common writing errors

- FAQs by writers

- awkward plurals

- ESL vocabulary lists

- all our grammar videos

- idioms and proverbs

- Latin terms

- collective nouns for animals

- tattoo fails

- vocabulary categories

- most common verbs

- top 10 irregular verbs

- top 10 regular verbs

- top 10 spelling rules

- improve spelling

- common misspellings

- role-play scenarios

- favo(u)rite word lists

- multiple-choice test

- Tetris game

- grammar-themed memory game

- 100s more...

Neuter Gender

What is the neuter gender.

Table of Contents

Neuter Pronouns

Why the neuter gender is important, video lesson.

- Large machines . Large machines such as ships and trains, which - by default - are neuter, are sometimes affectionately given a female gender (i.e., referred to as "she" or "her").

- Animals . An animal is referred to as "it." It is only referred to as "he" or "she" when the sex is known.

(Issue 1) There's no apostrophe in the neuter possessive determiner "its."

- A king and his son

- A queen and her dog

- A shark and its prey

(Issue 2) Finding an alternative to "his/her."

(Issue 3) Using gender-neutral pronouns for people who do not identify themselves as either male or female.

- There's no apostrophe in the possessive determiner "its." If you write "it's," try to expand it to "it is" or "it has." If you can't then it is wrong.

- When writing about someone whose gender is unknown, don't use "he/she," "his/her," etc. Use "they," "their," etc. For example:

- Any person who thinks he/she needs they need an interview should book one through his/her their line manager.

- Use "they" when talking about a non-binary person.

Are you a visual learner? Do you prefer video to text? Here is a list of all our grammar videos .

This page was written by Craig Shrives .

Learning Resources

more actions:

This test is printable and sendable

Help Us Improve Grammar Monster

- Do you disagree with something on this page?

- Did you spot a typo?

Find Us Quicker!

- When using a search engine (e.g., Google, Bing), you will find Grammar Monster quicker if you add #gm to your search term.

You might also like...

Share This Page

If you like Grammar Monster (or this page in particular), please link to it or share it with others. If you do, please tell us . It helps us a lot!

Create a QR Code

Use our handy widget to create a QR code for this page...or any page.

< previous lesson

next lesson >

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

What’s in a word? How less-gendered language is faring across Europe

A contentious vote in the French senate is only the latest battleground in the culture war over inclusive language

T he latest skirmish in the culture war over inclusive language has been playing out this week in France , where the senate voted in favour of a proposal to ban the use of less-gendered terms in official documents.

Les Républicains, the centre-right party behind the move, had claimed that inclusive neologisms such as iel – a mix of the male and female pronouns il and elle – and more general efforts to end the entrenched masculine bias in French were part of an “ideology that endangers the clarity of our language” .

Similar arguments are taking place across Europe and beyond as people – from politicians to parents – debate the role language should play in protecting and promoting diversity, inclusion and representation. In countries whose languages have male and female nouns, the issue is proving particularly challenging.

Opposition sénateurs and s énatrices disagreed with the outcome of Monday’s vote, describing it as a “retrograde and reactionary” text, a view shared by France’s independent high commission for equality between women and men.

To become law, the bill would have to be passed in the Assemblée Nationale and there is no date set for a debate. There are, however, growing calls to make gendered French less sexist – a campaign that has been around since the 1980s but which has been rejected by the influential Académie Française, the guardian of the language.

What irks campaigners most is that French grammatical rules make the masculine form of a noun the default over the female. So, women on an all-female board of company directors are called directrices ; if one man joins the board, they are referred to collectively as directeurs .

This was defended by the president, Emmanuel Macron, this week when he said: “In this language, the masculine acts as the neutral.” (Macron, however addresses citizens as les Français et les Françaises – and not the strictly correct les Français.)

But, as the academy has pointed out, suggestions for inclusive writing can render the written language unreadable, and thus arguably less – not more – inclusive.

The most popular method is the use of the “median dot” to include both masculine and feminine, as in, Cher·e·s ami·e·s (Dear friends), which is sometimes replaced by a hyphen ( cher-e-s ami-e-s) , by parentheses ( cher(e)s ami(e)s), or by slashes ( cher/e/s ami/e/s) .

According to the academy, all the above not only “offend the democracy of language” but also create difficulties for those with dyslexia and dysphasia, and for non-French speakers who are learning the language.

“Far from attracting the support of a majority of contemporaries, it appears to be the preserve of an elite, unaware of the difficulties encountered on a daily basis by educators and users of the school system,” the academy said in a statement.

Small steps, however, have been made. In 2019, the academy decided it was acceptable to say madame la maire , la ministre , la juge , despite being masculine nouns.

How did gendered languages evolve?

Silvia Luraghi, a professor of linguistics at the University of Pavia, says that in Proto-Indo-European – the reconstructed language from which all Indo-European languages originated – there is a three-gender system, as there is in German or Latin or Russian: masculine, feminine and neuter.

“In the course of their development, some languages lost gender partly – the Romance languages lost the neuter – or completely,” she says. “Armenian has no gender distinction even in third person pronouns. Persian has also lost the gender system even in pronouns. English has lost it in nouns and now it only exists in pronouns.”

Luraghi says it’s possible that at a Pre-Proto-Indo-European stage, there was “a two-gender, animacy-based system, with a two-fold distinction between animate and inanimate”.

She adds that while Romance languages cast off the neuter gender when they emerged from Latin, things today are hardly cut and dried. Take the Italian regional dialects from south of Rome, where there are four genders: male; female; an alternating gender for things that come in pairs, and a neuter for mass nouns.

All of which goes to prove that “languages don’t necessarily become less complicated; they can become more complicated”.

Luraghi is keenly aware of the tendency to “politicise everything” in Italy but says those who speak of the right way and the wrong way are missing the point. “From a linguist’s point of view, you can’t even say that something is correct or not correct because language is how people speak it and how they use it.”

In German, unlike in English, all nouns are grammatically coded as either masculine ( der ), feminine ( die ) or neuter ( das ). A male citizen is a Bürger , a female citizen a Bürgerin , and no one is seriously trying to change that.

But, as in France, there is growing frustration with the fact that the masculine form is traditionally used to refer to groups of people, even if that group is made up of a mix of males and females.

Because Germany does not have a national body to prescribe or standardise language use, people have been free to experiment in order to fix this problem. Attempts to make generic nouns more inclusive have been around since the 1980s but used to be relatively marginal phenomena: the “gender gap” ( Bürger_innen ) has been used in queer communities, while feminist groups more commonly capitalise the i ( BürgerInnen ).

Over the last 10 years, however, the use of an asterisk or “gender star” in generic forms ( Bürger*innen ) has started to be used outside subcultural groups or academic circles. Many universities, schools and some government bodies, such as the federal environment agency, recommend the use of the asterisk in their internal communications.

“The gender star is still not used by the majority of people in German society, but it has seen an impressive rise in a relatively short time,” said Anatol Stefanowitsch, a linguist at Berlin’s Freie Universität.

It has also inspired a backlash from political parties on the right, with the populist Alternative für Deutschland putting its opposition to “gender gaga” at the heart of its 2021 election campaign. In the eastern state of Saxony, the Christian Democrat government has banned the use of gender stars or gender gaps at schools or educational authorities, meaning that Schüler*innen would be marked as a mistake in students’ homework.

after newsletter promotion

“Conservatives have discovered gender-inclusive language as a potent subject for their culture wars,” Stefanowitsch said. “We are currently witnessing attempts to steer language use through the state, even if for now only at a regional level, which is a new phenomenon.”

In April 2021, Spain’s equality minister, Irene Montero, gave a speech in Madrid in which she attacked the rightwing regional government for its attitude to LGBTQ+ rights . But it wasn’t the sentiment that made headlines – it was the language. Montero deliberately used male, female and gender-neutral terms, referring to “libertad para todos, para todas y para todes” (“freedom for all men, all women and all gender-neutral people’’). She also spoke of “su hijo, hija e hije” – “your son, daughter or gender-neutral child” – and of niño, niña y niñe (boy, girl and gender-neutral child).

Her use of the terms has been ridiculed by her opponents and become yet another weapon in the culture wars between left and right. In 2018, the socialist deputy prime minister, Carmen Calvo, was criticised when she called for an overhaul of the Spanish constitution, arguing it was all written “in the masculine” because it used the male form to refer to “ministers and MPs”.

The then head of the Real Academia Española (RAE) – the body that oversees the evolution of the Spanish language – replied by counselling against “confusing grammar with sexism” and saying that economy should always be the guiding principle of language. “False solutions, such as using -e instead of -o and -a, are absurd, ridiculous and totally inefficient,” said Darío Villanueva.

In a 156-page report published in January 2020 , the RAE said changes in language should be driven by common usage rather than edicts from on high. It did, however, stress that, as in France and Germany, the masculine plural, such as pasajeros (passengers), remained the unmarked or default form to cover both men and women, adding that it was both commonly used and inclusive. Saying pasajeros , it continued, “does not render female passengers invisible nor does it disrespect them”.

Giorgia Meloni has made her position on the gender-inclusive language debate clear. Soon after becoming Italy’s first female prime minister, the ultra-conservative Meloni issued a note to journalists saying her preferred title of Presidente del Consiglio (President of the Council of Ministers) ought to be preceded by the masculine article il rather than the feminine la .

The decision sparked controversy, with the leftwing politician Laura Boldrini saying: “There is something strange about her; she hides behind the masculine.” Meloni sarcastically hit back that she did not think a woman’s “greatness” should be defined by being called capatrena – a nonexistent feminine form of capotreno , or train conductor.

A few months later, the Accademia della Crusca , watchdog of the Italian language, said Italy’s courts ought to stick to tradition and avoid the “novelty” of gender-neutral symbols in legal documents.

In Italian, gender-neutral noun endings to get around the masculine default include asterisks or the so-called schwa , a symbol that looks like an inverted e . The language watchdog argued that using gender-neutral nouns, for example when addressing the recipient of a letter with car* instead of the male caro or female cara (dear), would be artificial and only supported by minority groups.

Luisa Rizzitelli, a feminist and LGBTQ+ activist, said: “A lot of experimentation has come from the LGBTQ+ and feminist movement, and there is no shortage of heated debates about this: some people use the asterisk, x, u, y, slash, apostrophe, schwa, etc. Non-binary people in particular use these possibilities, which are innovative for the Italian language and increasingly widespread.”

Rizzitelli said the “common point” at the heart of the debate was the “legitimate need not to feel erased; the right to see a language capable of recognising and thus respecting one’s choices”, adding: “Non-binary people have every right to value this battle.”

Most viewed

Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty

Gender is not a spectrum

The idea that ‘gender is a spectrum’ is supposed to set us free. but it is both illogical and politically troubling.

by Rebecca Reilly-Cooper + BIO

What is gender? This is a question that cuts to the very heart of feminist theory and practice, and is pivotal to current debates in social justice activism about class, identity and privilege. In everyday conversation, the word ‘gender’ is a synonym for what would more accurately be referred to as ‘sex’. Perhaps due to a vague squeamishness about uttering a word that also describes sexual intercourse, the word ‘gender’ is now euphemistically used to refer to the biological fact of whether a person is female or male, saving us all the mild embarrassment of having to invoke, however indirectly, the bodily organs and processes that this bifurcation entails.

The word ‘gender’ originally had a purely grammatical meaning in languages that classify their nouns as masculine, feminine or neuter. But since at least the 1960s, the word has taken on another meaning, allowing us to make a distinction between sex and gender. For feminists, this distinction has been important, because it enables us to acknowledge that some of the differences between women and men are traceable to biology, while others have their roots in environment, culture, upbringing and education – what feminists call ‘gendered socialisation’.

At least, that is the role that the word gender traditionally performed in feminist theory. It used to be a basic, fundamental feminist idea that while sex referred to what is biological, and so perhaps in some sense ‘natural’, gender referred to what is socially constructed. On this view, which for simplicity we can call the radical feminist view, gender refers to the externally imposed set of norms that prescribe and proscribe desirable behaviour to individuals in accordance with morally arbitrary characteristics.

Not only are these norms external to the individual and coercively imposed, but they also represent a binary caste system or hierarchy, a value system with two positions: maleness above femaleness, manhood above womanhood, masculinity above femininity. Individuals are born with the potential to perform one of two reproductive roles, determined at birth, or even before, by the external genitals that the infant possesses. From then on, they will be inculcated into one of two classes in the hierarchy: the superior class if their genitals are convex, the inferior one if their genitals are concave.

From birth, and the identification of sex-class membership that happens at that moment, most female people are raised to be passive, submissive, weak and nurturing, while most male people are raised to be active, dominant, strong and aggressive. This value system, and the process of socialising and inculcating individuals into it, is what a radical feminist means by the word ‘gender’. Understood like this, it’s not difficult to see what is objectionable and oppressive about gender, since it constrains the potential of both male and female people alike, and asserts the superiority of males over females. So, for the radical feminist, the aim is to abolish gender altogether: to stop putting people into pink and blue boxes, and to allow the development of individuals’ personalities and preferences without the coercive influence of this socially enacted value system.

This view of the nature of gender sits uneasily with those who experience gender as in some sense internal and innate, rather than as entirely socially constructed and externally imposed. Such people not only dispute that gender is entirely constructed, but also reject the radical feminist analysis that it is inherently hierarchical with two positions. On this view, which for ease I will call the queer feminist view of gender, what makes the operation of gender oppressive is not that it is socially constructed and coercively imposed: rather, the problem is the prevalence of the belief that there are only two genders.

Humans of both sexes would be liberated if we recognised that while gender is indeed an internal, innate, essential facet of our identities, there are more genders than just ‘woman’ or ‘man’ to choose from. And the next step on the path to liberation is the recognition of a new range of gender identities: so we now have people referring to themselves as ‘genderqueer’ or ‘non-binary’ or ‘pangender’ or ‘polygender’ or ‘agender’ or ‘demiboy’ or ‘demigirl’ or ‘neutrois’ or ‘aporagender’ or ‘lunagender’ or ‘quantumgender’… I could go on. An oft-repeated mantra among proponents of this view is that ‘gender is not a binary; it’s a spectrum’. What follows from this view is not that we need to tear down the pink and the blue boxes; rather, we simply need to recognise that there are many more boxes than just these two.

At first blush this seems an appealing idea, but there are numerous problems with it, problems that render it internally incoherent and politically unattractive.

M any proponents of the queer view of gender describe their own gender identity as ‘non-binary’, and present this in opposition to the vast majority of people whose gender identity is presumed to be binary. On the face of it, there seems to be an immediate tension between the claim that gender is not a binary but a spectrum, and the claim that only a small proportion of individuals can be described as having a non-binary gender identity. If gender really is a spectrum, doesn’t this mean that every individual alive is non-binary, by definition? If so, then the label ‘non-binary’ to describe a specific gender identity would become redundant, because it would fail to pick out a special category of people.

To avoid this, the proponent of the spectrum model must in fact be assuming that gender is both a binary and a spectrum. It is entirely possible for a property to be described in both continuous and binary ways. One example is height: clearly height is a continuum, and individuals can fall anywhere along that continuum; but we also have the binary labels Tall and Short. Might gender operate in a similar way?

The thing to notice about the Tall/Short binary is that when these concepts are invoked to refer to people, they are relative or comparative descriptions. Since height is a spectrum or a continuum, no individual is absolutely tall or absolutely short; we are all of us taller than some people and shorter than some others. When we refer to people as tall, what we mean is that they are taller than the average person in some group whose height we are interested in examining. A boy could simultaneously be tall for a six-year-old, and yet short by comparison with all male people. So ascriptions of the binary labels Tall and Short must be comparative, and make reference to the average. Perhaps individuals who cluster around that average might have some claim to refer to themselves as of ‘non-binary height’.

However, it seems unlikely that this interpretation of the spectrum model will satisfy those who describe themselves as non-binary gendered. If gender, like height, is to be understood as comparative or relative, this would fly in the face of the insistence that individuals are the sole arbiters of their gender. Your gender would be defined by reference to the distribution of gender identities present in the group in which you find yourself, and not by your own individual self-determination. It would thus not be up to me to decide that I am non-binary. This could be determined only by comparing my gender identity to the spread of other people’s, and seeing where I fall. And although I might think of myself as a woman, someone else might be further down the spectrum towards womanhood than I am, and thus ‘more of a woman’ than me.

Further, when we observe the analogy with height we can see that, when observing the entire population, only a small minority of people would be accurately described as Tall or Short. Given that height really is a spectrum, and the binary labels are ascribed comparatively, only the handful of people at either end of the spectrum can be meaningfully labelled Tall or Short. The rest of us, falling along all the points in between, are the non-binary height people, and we are typical. In fact, it is the binary Tall and Short people who are rare and unusual. And if we extend the analogy to gender, we see that being non-binary gendered is actually the norm, not the exception.

to call oneself non-binary is in fact to create a new false binary

If gender is a spectrum, that means it’s a continuum between two extremes, and everyone is located somewhere along that continuum. I assume the two ends of the spectrum are masculinity and femininity. Is there anything else that they could possibly be? Once we realise this, it becomes clear that everybody is non-binary, because absolutely nobody is pure masculinity or pure femininity. Of course, some people will be closer to one end of the spectrum, while others will be more ambiguous and float around the centre. But even the most conventionally feminine person will demonstrate some characteristics that we associate with masculinity, and vice versa.

I would be happy with this implication, because despite possessing female biology and calling myself a woman, I do not consider myself a two-dimensional gender stereotype. I am not an ideal manifestation of the essence of womanhood, and so I am non-binary. Just like everybody else. However, those who describe themselves as non-binary are unlikely to be satisfied with this conclusion, as their identity as ‘non-binary person’ depends upon the existence of a much larger group of so-called binary ‘cisgender’ people, people who are incapable of being outside the arbitrary masculine/feminine genders dictated by society.

And here we have an irony about some people insisting that they and a handful of their fellow gender revolutionaries are non-binary: in doing so, they create a false binary between those who conform to the gender norms associated with their sex, and those who do not. In reality, everybody is non-binary. We all actively participate in some gender norms, passively acquiesce with others, and positively rail against others still. So to call oneself non-binary is in fact to create a new false binary. It also often seems to involve, at least implicitly, placing oneself on the more complex and interesting side of that binary, enabling the non-binary person to claim to be both misunderstood and politically oppressed by the binary cisgender people.

I f you identify as pangender, is the claim that you represent every possible point on the spectrum? All at the same time? How might that be possible, given that the extremes necessarily represent incompatible opposites of one another? Pure femininity is passivity, weakness and submission, while pure masculinity is aggression, strength and dominance. It is simply impossible to be all of these things at the same time. If you disagree with these definitions of masculinity and femininity, and do not accept that masculinity should be defined in terms of dominance while femininity should be described in terms of submission, you are welcome to propose other definitions. But whatever you come up with, they are going to represent opposites of one another.

A handful of individuals are apparently permitted to opt out of the spectrum altogether by declaring themselves ‘agender’, saying that they feel neither masculine nor feminine, and don’t have any internal experience of gender. We are not given any explanation as to why some people are able to refuse to define their personality in gendered terms while others are not, but one thing that is clear about the self-designation as ‘agender’: we cannot all do it, for the same reasons we cannot all call ourselves non-binary. If we were all to deny that we have an innate, essential gender identity, then the label ‘agender’ would become redundant, as lacking in gender would be a universal trait. Agender can be defined only against gender. Those who define themselves and their identity by their lack of gender must therefore be committed to the view that most people do have an innate, essential gender but that, for some reason, they do not.

Once we assert that the problem with gender is that we currently recognise only two of them, the obvious question to ask is: how many genders would we have to recognise in order not to be oppressive? Just how many possible gender identities are there?

The only consistent answer to this is: 7 billion, give or take. There are as many possible gender identities as there are humans on the planet. According to Nonbinary.org, one of the main internet reference sites for information about non-binary genders, your gender can be frost or the Sun or music or the sea or Jupiter or pure darkness. Your gender can be pizza.

But if this is so, it’s not clear how it makes sense or adds anything to our understanding to call any of this stuff ‘gender’, as opposed to just ‘human personality’ or ‘stuff I like’. The word gender is not just a fancy word for your personality or your tastes or preferences. It is not just a label to adopt so that you now have a unique way to describe just how large and multitudinous and interesting you are. Gender is the value system that ties desirable (and sometimes undesirable?) behaviours and characteristics to reproductive function. Once we’ve decoupled those behaviours and characteristics from reproductive function – which we should – and once we’ve rejected the idea that there are just two types of personality and that one is superior to the other – which we should – what can it possibly mean to continue to call this stuff ‘gender’? What meaning does the word ‘gender’ have here, that the word ‘personality’ cannot capture?

On Nonbinary.org, your gender can apparently be:

(Name)gender: ‘A gender that is best described by one’s name, good for those who aren’t sure what they identify as yet but definitely know that they aren’t cis … it can be used as a catch-all term or a specific identifier, eg, johngender, janegender, (your name here)gender, etc.’

The example of ‘(name)gender’ perfectly demonstrates how non-binary gender identities operate, and the function they perform. They are for people who aren’t sure what they identify as, but know that they aren’t cisgender. Presumably because they are far too interesting and revolutionary and transgressive for something as ordinary and conventional as cis.

The solution is not to try to slip through the bars of the cage while leaving the rest of the cage intact, and the rest of womankind trapped within it

This desire not to be cis is rational and makes perfect sense, especially if you are female. I too believe my thoughts, feelings, aptitudes and dispositions are far too interesting, well-rounded and complex to simply be a ‘cis woman’. I, too, would like to transcend socially constructed stereotypes about my female body and the assumptions others make about me as a result of it. I, too, would like to be seen as more than just a mother/domestic servant/object of sexual gratification. I, too, would like to be viewed as a human being, a person with a rich and deep inner life of my own, with the potential to be more than what our society currently views as possible for women.

The solution to that, however, is not to call myself agender, to try to slip through the bars of the cage while leaving the rest of the cage intact, and the rest of womankind trapped within it. This is especially so given that you can’t slip through the bars. No amount of calling myself ‘agender’ will stop the world seeing me as a woman, and treating me accordingly. I can introduce myself as agender and insist upon my own set of neo-pronouns when I apply for a job, but it won’t stop the interviewer seeing a potential baby-maker, and giving the position to the less qualified but less encumbered by reproduction male candidate.

H ere we arrive at the crucial tension at the heart of gender identity politics, and one that most of its proponents either haven’t noticed, or choose to ignore because it can only be resolved by rejecting some of the key tenets of the doctrine.

Many people justifiably assume that the word ‘transgender’ is synonymous with ‘transsexual’, and means something like: having dysphoria and distress about your sexed body, and having a desire to alter that body to make it more closely resemble the body of the opposite sex. But according to the current terminology of gender identity politics, being transgender has nothing to do with a desire to change your sexed body. What it means to be transgender is that your innate gender identity does not match the gender you were assigned at birth. This might be the case even if you are perfectly happy and content in the body you possess. You are transgender simply if you identify as one gender, but socially have been perceived as another.

It is a key tenet of the doctrine that the vast majority of people can be described as ‘cisgender’, which means that our innate gender identity matches the one we were assigned at birth. But as we have seen, if gender identity is a spectrum, then we are all non-binary, because none of us inhabits the points represented by the ends of that spectrum. Every single one of us will exist at some unique point along that spectrum, determined by the individual and idiosyncratic nature of our own particular identity, and our own subjective experience of gender. Given that, it’s not clear how anybody ever could be cisgender. None of us was assigned our correct gender identity at birth, for how could we possibly have been? At the moment of my birth, how could anyone have known that I would later go on to discover that my gender identity is ‘frostgender’, a gender which is apparently ‘very cold and snowy’?

Once we recognise that the number of gender identities is potentially infinite, we are forced to concede that nobody is deep down cisgender, because nobody is assigned the correct gender identity at birth. In fact, none of us was assigned a gender identity at birth at all. We were placed into one of two sex classes on the basis of our potential reproductive function, determined by our external genitals. We were then raised in accordance with the socially prescribed gender norms for people of that sex. We are all educated and inculcated into one of two roles, long before we are able to express our beliefs about our innate gender identity, or to determine for ourselves the precise point at which we fall on the gender continuum. So defining transgender people as those who at birth were not assigned the correct place on the gender spectrum has the implication that every single one of us is transgender; there are no cisgender people.

The logical conclusion of all this is: if gender is a spectrum, not a binary, then everyone is trans. Or alternatively, there are no trans people. Either way, this a profoundly unsatisfactory conclusion, and one that serves both to obscure the reality of female oppression, as well as to erase and invalidate the experiences of transsexual people.

The way to avoid this conclusion is to realise that gender is not a spectrum. It’s not a spectrum, because it’s not an innate, internal essence or property. Gender is not a fact about persons that we must take as fixed and essential, and then build our social institutions around that fact. Gender is socially constructed all the way through, an externally imposed hierarchy, with two classes, occupying two value positions: male over female, man over woman, masculinity over femininity.

The truth of the spectrum analogy lies in the fact that conformity to one’s place in the hierarchy, and to the roles it assigns to people, will vary from person to person. Some people will find it relatively easier and more painless to conform to the gender norms associated with their sex, while others find the gender roles associated with their sex so oppressive and limiting that they cannot tolerably live under them, and choose to transition to live in accordance with the opposite gender role.

Gender as a hierarchy perpetuates the subordination of female people to male people, and constrains the development of both sexes

Fortunately, what is a spectrum is human personality, in all its variety and complexity. (Actually that’s not a single spectrum either, because it is not simply one continuum between two extremes. It’s more like a big ball of wibbly-wobbly, humany-wumany stuff.) Gender is the value system that says there are two types of personality, determined by the reproductive organs you were born with. One of the first steps to liberating people from the cage that is gender is to challenge established gender norms, and to play with and explore your gender expression and presentation. Nobody, and certainly no radical feminist, wants to stop anyone from defining themselves in ways that make sense to them, or from expressing their personality in ways they find enjoyable and liberating.

So if you want to call yourself a genderqueer femme presenting demigirl, you go for it. Express that identity however you like. Have fun with it. A problem emerges only when you start making political claims on the basis of that label – when you start demanding that others call themselves cisgender, because you require there to be a bunch of conventional binary cis people for you to define yourself against; and when you insist that these cis people have structural advantage and political privilege over you, because they are socially read as the conformist binary people, while nobody really understands just how complex and luminous and multifaceted and unique your gender identity is. To call yourself non-binary or genderfluid while demanding that others call themselves cisgender is to insist that the vast majority of humans must stay in their boxes, because you identify as boxless.

The solution is not to reify gender by insisting on ever more gender categories that define the complexity of human personality in rigid and essentialist ways. The solution is to abolish gender altogether. We do not need gender. We would be better off without it. Gender as a hierarchy with two positions operates to naturalise and perpetuate the subordination of female people to male people, and constrains the development of individuals of both sexes. Reconceiving of gender as an identity spectrum represents no improvement.

You do not need to have a deep, internal, essential experience of gender to be free to dress how you like, behave how you like, work how you like, love who you like. You do not need to show that your personality is feminine for it to be acceptable for you to enjoy cosmetics, cookery and crafting. You do not need to be genderqueer to queer gender. The solution to an oppressive system that puts people into pink and blue boxes is not to create more and more boxes that are any colour but blue or pink. The solution is to tear down the boxes altogether.

Design and fashion

Sitting on the art

Given its intimacy with the body and deep play on form and function, furniture is a ripely ambiguous artform of its own

Emma Crichton Miller

Learning to be happier

In order to help improve my students’ mental health, I offered a course on the science of happiness. It worked – but why?

Consciousness and altered states

How perforated squares of trippy blotter paper allowed outlaw chemists and wizard-alchemists to dose the world with LSD

Last hours of an organ donor

In the liminal time when the brain is dead but organs are kept alive, there is an urgent tenderness to medical care

Ronald W Dworkin

The environment

We need to find a way for human societies to prosper while the planet heals. So far we can’t even think clearly about it

Ville Lähde

Archaeology

Why make art in the dark?

New research transports us back to the shadowy firelight of ancient caves, imagining the minds and feelings of the artists

Izzy Wisher

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

The Romanian Neuter Examined Through A Two-Gender N-Gram Classification System

Related Papers

Blanca Croitor

We discuss several possible analyses of Romanian “neuter” nouns (a productive class of nouns which trigger masculine agreement in the singular and feminine agreement in the plural): the three-gender analysis (Romanian has three genders and systematic syncretism), the ambigeneric analysis (Romanian neuters are masculine in the singular and feminine in the plural), the underspecification analysis (Romanian neuters are not specified for gender) and the nominal class analysis (nouns do not have genders, but rather nominal classes which are selected by Number heads on which the gender feature is generated). The arguments used to decide between these analyses are (i) gender in the pronominal system, (ii) gender agreement in coordination and (iii) general economy considerations. We retain the underspecification analysis and the nominal class analysis and propose solutions to the problems these analyses face.

Jurgita Kapočiūtė-Dzikienė

This paper describes the gender detection research done on Lithuanian texts using automatic machine learning methods. The main contribution of our work is investigations done namely on the very short (avg. ~ 39 tokens) non-normative texts. With this paper we analyze a fundamental problem: how to choose automatic methods (in particular, classifiers and feature types) that could achieve the highest accuracy in our solving author profiling task (when the short pure text itself is the only evidence used for determining the author’s meta-information). The related research analysis helped us to select the methods which demonstrated encouraging results on the other languages and to apply them on the Lithuanian dataset. Out of a number of experimentally investigated classifiers with lexical or symbolic features the Naïve Bayes Multinomial method with character ngrams (of n = [1, 5]) feature type yielded the best performance reaching 83.6% of the accuracy. Keywords—gender detection; author p...

Liviu P. Dinu

Boban Arsenijevic

Departing from an analysis of collective nouns under which they are nouns with a cumulative reference and a count semantic base, but without a uniform atomic level, and hence without a stabile unit of counting, the paper argues that gender, as a near counterpart of classifiers, has a role in specifying the unit of counting. Taking neuter gender in Serbo-Croatian as the absence of gender (Kramer 2009), it is analyzed as a class of nouns which do not morpho-syntactically express the restriction over the unit of counting. In the domain of count nouns, the combination with count semantics yields nouns with non-uniform atomicity. Neuter count nouns are thus argued to be nouns which fail to formally express uniform atomicity, which makes them quantized counterparts of collective nouns (i.e. quantized, non-uniformly atomic). While the non-uniform atomicity does not affect their singular forms, it is argued that neuter nouns in SC are unable to derive proper plural forms, and that productively derived collective forms are used instead. In other words, all neuter nouns in SC effectively have the status of singulatives – in the sense that they are expressions which refer to singularities and establish contrast in grammatical number with collective rather than with plural forms. A range of puzzling empirical phenomena related to neuter nouns is shown to be straightforwardly resolved by this view of the semantic effects of the absence of gender. The paper also includes a discussion of Serbo-Croatian collective nouns, showing that their behavior in respect of number agreement triggered on the finite verb and licensing of reciprocal interpretations are determined by whether they are derived from an existing singular base, and whether they remain within its paradigms. Traditional neuter plurals, argued in this paper to be collectives, are shown to pattern in this respect with the collectives braća ‘brother.Coll’ and deca ‘child.Coll’, as they all belong to the paradigm of their singular bases, and as expected they all require plural agreement on the verb and license reciprocal predicates.

Andreea C Nicolae

Names - A Journal of Onomastics

Irene Renau

This paper presents a series of methods for automatically determining the gender of proper names, based on their co-occurrence with words and grammatical features in a large corpus. Although the results obtained were for Spanish given names, the method presented here can be easily replicated and used for names in other languages as well. Most methods reported in the literature use pre-existing lists of first names that require costly manual processing and tend to become quickly outdated. Instead, we propose using corpora. Doing so offers the possibility of obtaining real and up-to-date name-gender links. To test the effectiveness of our method, we explored various machine learning methods as well as another method based on simple frequency of co-occurrence. The latter produced the best results: 93% precision and 88% recall on a database of ca. 10,000 mixed names. Our method can be applied to a variety of natural language processing tasks such as information extraction, machine trans...

Knowledge Horizons Economics

Alexandra Moraru

Marius Popescu

clg.wlv.ac.uk

Iustina Ilisei

Gender Studies

Ruxandra Visan

The present paper seeks to investigate the representation of a relevant number of gendered epithets in two prominent Romanian dictionaries, the most recent edition of DOOM (2021, Third Edition) and the current edition of DEX (2016, Revised Edition based on the first and second editions). Taking into account the prescriptive dimension which both these dictionaries share and the fact that they both retain their status as significant reference books in present-day Romania, the paper examines the way in which these current dictionaries choose to describe these words, arguing for the significance of the “metadata” (Nunberg, 2018; Pullum, 2018) component in the lexicographical representation of lexical items which can function as gendered insults.

RELATED PAPERS

Journal of Essential Oil Research

Erika Soares Reis

Beatriz Valente

Estudios Eclesiásticos. Revista de investigación e información teológica y canónica

Ianire Angulo Ordorika

Anita Patyna

Jérôme Juilleret

jagat C borah

Brain Research

Jurnal Kependidikan: Jurnal Hasil Penelitian dan Kajian Kepustakaan di Bidang Pendidikan, Pengajaran dan Pembelajaran

Ridhatul Husna

Revista Iberoamericana de Educación

Carolina Armijo

Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology and Oral Radiology

Valdir Meirelles

George Bitros

Anton Pratama

Revista de Contabilidade e Organizações

Paula Gontijo Martins

Keidi Kaitsa

Molecular Imaging and Biology

Anna-liisa Brownell

International Journal of Environment

Radwan Radwan

Ophthalmology

Samantha Fraser-bell

Call/Wa : 0812 1776 0588 | Agen Tongkat Komando Aceh Timur

Pembuat Tongkat Komando

Current Biology

Margarete Heck

Scientific reports

Susana Nunez

luisa riveros

Pain Physician

Mariano Fernández Baena

zakiah nasution

Arch Argent …

Liliana Bogni

Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society

Osane Oruetxebarria

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, neuter gender is defined as those words "relating to, or constituting the gender that ordinarily includes most words or grammatical forms referring to things classed as neither masculine nor feminine", and according to the Oxford Learner's Dictionary, it is defined as "belonging to a class of nouns, pronouns, adjectives or verbs whose gender ...

Neuter is a long-established word for a sex or gender outside of the gender binary. Various dictionaries generally give it these two relevant definitions, among others: ... Neuter is the only gender that always suits me." ... In 1993 Sinclair wrote the essay, "Don't Mourn for Us", articulating an anti-cure perspective on autism. The essay has ...

According to Grammar Monster, neuter gender is one of three genders in English grammar, which also includes masculine and feminine gender. The masculinity and femininity of a noun often determine the pronouns and adjectives that are used. A noun in English is neuter by default. Many Indo-European languages have a natural gender to words, having ...

Common Neuter Gender Nouns List. Let us look out for common and neuter gender list given below: Here are some examples as sentences: The book is on the table. I left my car keys on the chair. The computer is running smoothly. The door creaked as it opened. The house has a beautiful garden. The table is made of oak.

Neuter is the only gender that always suits me." As writer and photographer, Cahun worked at upending convention. "My role," she wrote in an essay published after her death, "was to embody ...

1987 essay "Mama's Baby, Papa's Maybe: An American Grammar Book," Hortense Spillers reflects on black gender and slavery by suggesting slaveholding society perceived enslaved black people as "neuter-bound" (77), meaning that their "open vulnerability to a gigantic sexualized repertoire" (77) positioned their experience of

This essay argues that the work of a lesser-known mid-eighteenth-century satirist Charles Churchill (1731-1764) provides a rich literary source for queer historical considerations of the conflation of xenophobia with effeminophobia in colonial imaginings of Ireland. This article analyzes Churchill's verse-satire The Rosciad (1761) through a queer lens in order to reengage the complex history ...

If the word does not denote something obviously masculine or feminine, then it is a neuter word. Why the Neuter Gender Is Important There are three noteworthy issues related to neuter gender. (Issue 1) There's no apostrophe in the neuter possessive determiner "its." Look at the following list of nouns and their possessive determiners:

Semantic Scholar extracted view of "NEUTER GENDER - A WAY TO INVOLUTION" by M. Ureche et al. Semantic Scholar extracted view of "NEUTER GENDER - A WAY TO INVOLUTION" by M. Ureche et al. ... Search 217,797,563 papers from all fields of science. Search. Sign In Create Free Account. DOI: 10.29302/ar.2017.suplim.2.14; Corpus ID: 231244534; NEUTER ...

Abstract:This article highlights moments in William Craft's Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom and Harriet Jacobs's Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl that feature black women using masculine performance, and black men using their own (knowledge of) same-gender desires, for the purposes of black liberation. Focusing on these moments broadens our understandings of queer gender during ...

Persson, Gunnar 1996. Invectives and Gender in English. In G. Persson and M. Rydén (eds.), Male and Female Terms in English: Proceedings of the Symposium at Umeå University, May 18-19, 1994, 157-73. Umeå: Umeå University; Uppsala: Distributed by Swedish Science Press. Persson, Gunnar and Mats Rydén 1995.

FAQs. Summary. Genetic factors typically define a person's sex, but gender refers to how they identify on the inside. Some examples of gender identity types include nonbinary, cisgender ...

A third-person pronoun is a pronoun that refers to an entity other than the speaker or listener. Some languages with gender-specific pronouns have them as part of a grammatical gender system, a system of agreement where most or all nouns have a value for this grammatical category. A few languages with gender-specific pronouns, such as English, Afrikaans, Defaka, Khmu, Malayalam, Tamil, and ...

Take the Italian regional dialects from south of Rome, where there are four genders: male; female; an alternating gender for things that come in pairs, and a neuter for mass nouns.

The idea that 'gender is a spectrum' is supposed to set us free. But it is both illogical and politically troubling. is a political philosopher at the University of Warwick in the UK. She is interested in political liberalism, democratic theory, moral psychology, and the philosophy of emotion, and is currently working on a book about sex ...

In the insular region of Indonesia directly west of New Guinea, however, a semantic gender distinction of neuter versus nonneuter is commonplace. In this paper, I argue that this gender ... Duane A. 1997. Towards a reconstruction and reclassification of the Lakes Plains languages of Irian Jaya. In Papers in New Guinea Linguistics 2, ed. by ...

The third gender of Old Italian. Michele LOPORCARO. 2014, Diachronica. We demonstrate that Old Italian had a three-gender system within which the neuter still qualified as a fully fledged gender value. To substantiate this claim, we adduce evidence showing that (a) Old Italian had three distinct sets of controllers, each of which selected a ...

Previous research indicates that grammatical gender in Dutch, and in particular neuter gender, is typically acquired late, with children overgeneralising common gender forms of the determiner to neuter nouns until (at least) age 6 (e.g., Blom et al. 2008, Bol and Kuiken, 1988, Van der Velde, 2003). Almost all of these previous studies use production data only. It is possible that these data ...

Proceedings of COLING 2012: Demonstration Papers, pages 119-124, COLING 2012, Mumbai, December 2012. Dealing with the grey sheep of the Romanian gender system, the neuter. Liviu P. DINU, Vlad NICULAE, MariaSULEA¸. University of Bucharest, Faculty of Mathematics and Computer Science, Centre for Computational Linguistics, Bucharest.

We discuss several possible analyses of Romanian "neuter" nouns (a productive class of nouns which trigger masculine agreement in the singular and feminine agreement in the plural): the three-gender analysis (Romanian has three genders and systematic syncretism), the ambigeneric analysis (Romanian neuters are masculine in the singular and feminine in the plural), the underspecification ...

of a more extensive discussion over gender-neutral childcare, which many parents oppose [7]. Opponents of gender-neutral parenting say that gender-neutral toys are damaging their children by confusing them, which will affect how they engage with the public and their classmates as they grow. 3.2. Parents' Reactions to the Situation

Although the gender of God in Judaism is referred to in the Tanakh with masculine imagery and grammatical forms, traditional Jewish philosophy does not attribute the concept of sex to God. At times, Jewish aggadic literature and Jewish mysticism do treat God as gendered. The ways in which God is gendered have also changed across time, with some modern Jewish thinkers viewing God as outside of ...

Your examiners have read thousands of essays on every aspect of the play, from the standard to the fringe theories. Do some reading, get some quotes learned (and *understand* them, really think about what they mean and what they're doing in the play) and focus on writing clearly and persuasively.